Abstract

Background

Right ventricular (RV) function is a major determinant of outcome in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). However, uncertainty persists about the optimal method of evaluation.

Methods

We measured RV end-systolic and end-diastolic volumes (ESV and EDV) using cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and RV pressures during right heart catheterization in 140 incident PAH patients and 22 controls. A maximum RV pressure (Pmax) was calculated from the nonlinear extrapolations of early and late systolic portions of the RV pressure curve. The gold standard measure of RV function adaptation to afterload, or RV-arterial coupling (Ees/Ea) was estimated by the stroke volume (SV)/ESV ratio (volume method) or as Pmax/mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) minus 1 (pressure method) (n=84). RV function was also assessed by ejection fraction (EF), right atrial pressure (RAP) and SV.

Results

Higher Ea and RAP, and lower compliance, SV and EF predicted outcome at univariate analysis. Ees/Ea estimated by the pressure method did not predict outcome but Ees/Ea estimated by the volume method (SV/ESV) did. At multivariate analysis, only SV/ESV and EF were independent predictors of outcome. Survival was poorer in patients with a fall in EF or SV/ESV during follow up (n=44, p=0.008).

Conclusion

RV function to predict outcome in PAH is best evaluated by imaging derived SV/ESV or EF. In this study, there was no added value of invasive measurements or simplified pressure-derived estimates of RV-arterial coupling.

Keywords: pulmonary hypertension, pressure-volume relationship, prognosis, right ventricular dysfunction

INTRODUCTION

It has been realized in recent years that right ventricular (RV) function is a major determinant of functional state, exercise capacity and survival in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) [1]. However, how to measure RV function and what variables might be most clinically relevant at the bedside remains uncertain [1, 2]

The gold standard measure of RV systolic functional adaptation to increased loading conditions is end-systolic elastance (Ees), (or end-systolic pressure (ESP) divided by end-systolic volume (ESV)), corrected for arterial elastance (Ea), (or stroke volume (SV) divided by ESP). The Ees/Ea ratio defines RV-arterial coupling, or the matching of contractility to afterload. Ees is a measure of RV contractility and unlike other measures of RV function is load independent. Ea is a measure of the afterload faced by the RV and incorporates resistance, compliance and impedance of the pulmonary circulation. The optimal balance between RV work and oxygen consumption occurs at an Ees/Ea ratio of 1.5–2 [1, 2].

The reference method for the determination of Ees requires instantaneous and simultaneous measurements of RV pressure and volume and generation of a family of pressure-volume loops at decreasing venous return [3]. This is not practical at the bedside. However Ees can also be estimated from a single P-V loop [4]. This method relies on the calculation of a maximum RV pressure (Pmax) from the extrapolation of early and late systolic portions of a RV pressure curve and the continuous recording of RV pressure and relative change in volume to define ESP and ESV. From these, Ees and Ea are easily calculated. The estimation of RV-arterial coupling by an Ees/Ea ratio can further be simplified for pressure and expressed as a SV/ESV ratio [5], ie the volume method. Alternatively the ratio can be simplified for volumes and expressed as Pmax divided by mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP), taken as a surrogate for ESP, minus 1 [6], ie the pressure method. A RV pressure curve is easily obtained during a right heart catheterization. RV volumes are ideally determined by magnetic resonance imaging (CMR).

From RV volumes it is naturally also easy to calculate a SV and an ejection fraction (EF) as SV/EDV. Cardiac CMR studies have shown that decreased SV and RV EF are predictive of poor outcome [7], and that a deterioration in RV EF during PAH therapy predicts a poor survival irrespective of improvements in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) [8]. However, EF is preload-dependent while Ees/Ea is theoretically not. Therefore, estimates of Ees should be superior in determining clinical state and outcome. Accordingly, a recent study on a limited number of patients referred for investigation of PH showed Ees/Ea estimated by SV/ESV to be an independent predictor of outcome while EF was not [9].

We therefore investigated the prognostic utility of RV-arterial coupling determined by both the volume and the pressure methods, compared to more usual determinations of EF and right heart catheterization-derived RAP and SV in a large cohort of patients with PAH, and in addition examined changes over time of these measurements with targeted therapies and their impact on survival.

METHODS

We identified 140 treatment naïve incident cases of PAH diagnosed between January 2004 and April 2014 at the Scottish Pulmonary Vascular Unit, Glasgow. Patients were included after multidisciplinary evaluation based on right heart catheterization, echocardiography, pulmonary function testing and CT scan of thorax. All patients underwent invasive measurements and cardiac CMR within 72 hours and received pulmonary vasodilator therapy in accordance with guidelines [10]. In 84/140 patients, RV pressures traces were available and were manually re-digitised using GetData Graph Digitizer 2.26. A subgroup of 44 patients underwent serial CMR after a minimum of 3 months of PAH therapy. 22 control patients without pulmonary hypertension (defined as a mPAP <25mmHg) who had right heart catheterization and CMR to investigate breathlessness were included to provide reference values for RV-arterial coupling by the two methods.

Cardiac CMR

CMR imaging was performed in the supine position on a 1.5-T magnetic resonance imaging scanner (Sonata Magnetom, Siemens, Erlangen Germany) and images were analysed using the Argus analysis software (Houston, Texas). RV and LV volumes were determined by manual tracing endocardial borders of short axis stack obtained during breath-hold as previously described [11]. CMR variables were indexed for body surface area and adjusted for age.

Calculation of RV-arterial coupling

In those patients for whom RV pressure trace was available for analysis, Ees was calculated using the single beat method [4]. An average RV pressure trace was generated for each patient across a respiratory cycle, typically 4–6 beats. Pmax, the maximum theoretical pressure the ventricle could generate if isovolumetric contraction occurred, was calculated using a manual sine-wave extrapolation of the early systolic and diastolic portions of the RV pressure curve. ESP was approximated by mPAP [6]. Ees was calculated as the slope of end-systolic pressure volume line, Ees = (Pmax − mPAP) / (RVEDV − RVESV). Arterial elastance (Ea) was estimated by mPAP/(RVEDV − RVESV). RV-arterial coupling (Ees/Ea) was simplified for volumes as Pmax/mPAP − 1 (hereafter referred to as the pressure method, Ees/Ea-P), or simplified for pressures as SV/ESV (hereafter referred to as the volume method, SV/ESV) [9]. Stroke volume was calculated as cardiac output measured by thermodilution during the right heart catheterization divided by heart rate or as EDV minus ESV, and indexed for body surface area (SVI).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 22 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) and Graphpad Prism Version 5.00 (Graphpad Software, California, USA). Continuous variables were tested for normality using D’Agostino and Pearson omnibus normality test. Normally distributed variables are shown as mean ± standard deviation and non-normally distributed variables as median (IQR). Categorical variables are described by percentage (number) unless otherwise stated. Correlation coefficients were calculated by the Spearman method.

Survival was from date of diagnostic right heart catheter and endpoint was date of either death, lung transplantation or censoring. In those who underwent serial CMR to assess change in RV function, survival was from the date of the second study. Patients were censored if they were lost to follow up or alive at last day of study (4th August 2014). All cause mortality was used for survival analysis. Survival predictors were determined using a bivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis with age. Variables with a p value ≤ 0.2 were considered for multivariate analysis. Survival of patients with decreased SV/ESV in comparison to those with stable or increased SV/ESV were compared by logrank test. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant throughout.

RESULTS

Population characteristics

Of the 140 PAH patients included in the study, 61 deaths occurred in the follow up period (median survival 2086 days). Table 1 describes the characteristics of the whole population and the 84 PAH patients with RV pressure trace analysis in comparison to 22 control patients with mPAP <25mmHg. PAH patients had a mPAP range of 28–101 mmHg and demonstrated impaired RVEF, low SVI and increased RV volumes and mass.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and haemodynamics of all PAH patients (n=140), subgroup who had RV pressure analysis (n= 84) and control subjects with mPAP <25mmHg (n=22)

| all PAH patients |

Patients with RV pressure trace analysis |

p value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=140 | PAH n=84 | Controls n=22 | ||

| Age years | 55 ± 16 | 55 ± 16 | 58 ± 14 | 0.518 |

| Sex % female | 66 | 64 | 64 | 1.00 |

| Aetiology % (n) | ||||

| IPAH/FPAP | 53.6 (75) | 63 (53) | ||

| CTDPH | 37.9 (53) | 31 (26) | ||

| POPH | 6.4 (9) | 5 (4) | ||

| HIV | 1.4 (2) | 0 | ||

| CHD | 0.7 (1) | 1 (1) | ||

| Therapy % (n) | ||||

| PDE5i | 51.4 (72) | 59.5 (50) | ||

| ERA | 35 (49) | 28.6 (24) | ||

| Prostanoid | 5.0 (7) | 1.2 (1) | ||

| CCB | 2.1 (3) | 1.2 (1) | ||

| Dual | 6.4 (9) | 9.5 (8) | ||

| mPAP mmHg | 48 ± 13 | 50 ± 13 | 18 ± 4 | <0.001 |

| RAP mmHg | 7 ± 6 | 8 ± 6 | 3 ± 2 | <0.001 |

| PVR Wood units | 11.8 ± 5.8 | 12.2 ± 5.9 | 2.1 ± 0.9 | <0.001 |

| CI L/min/m2 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 2.2 ± 0.7 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | <0.001 |

| SV/PP mL/mmHg | 1.03 ± 0.5(138) | 0.99 ± 0.4(82) | 3.7 ± 1.5 | <0.001 |

| RVEF % | 36 ± 15 | 33 ± 13 | 58 ± 14 | <0.001 |

| SVI mL/m2 | 31 ± 10 | 30 ± 10 | 43 ± 20 | <0.001 |

| RVEDVI mL/m2 | 92 ± 26 | 94 ± 28 | 74 ± 25 | 0.004 |

| RVESVI mL/m2 | 61 ± 27 | 64 ± 28 | 31 ± 16 | <0.001 |

| RVMI g/m2 | 52 ± 19 | 53 ± 18 | 36 ± 16 | <0.001 |

| 6MWD m | 305 ± 117(77) | 404 ± 116(21) | 0.001 | |

| NTproBNP pg/mL | 1140 (96 – 3577)(75) |

182 (45 – 243) (12) |

<0.001 | |

Data presented as % (n), mean±sd or median (IQR) unless otherwise stated.

p value comparison between controls and subgroup 84 PAH patients.

PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension; RV: right ventricle; IPAH: idiopathic PAH; FPAP: familial PAH; CTDPH: connective tissue disease associated PH; POPH: portopulmonary hypertension; CHD: congenital heart disease associated PH; PDE5i: phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor; ERA: endothelial receptor antagonist; CCB: calcium channel blocker; mPAP: mean pulmonary artery pressure; RAP: right atrial pressure; PVR: pulmonary vascular resistance; CI: cardiac index; SV/PP: compliance, ratio stroke volume/pulse pressure; RVEF: RV ejection fraction; SVI: stroke volume index; RVEDVI: RV end diastolic volume index; RVESVI: RV end systolic volume index; RVMI: RV mass index; 6MWD: six minute walk distance; NTproBNP: N terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide.

There were no significant differences between SVI calculated as cardiac index/ heart rate or as EDV − ESV (30 ± 10 vs 28 ± 10 mL/m2 in PAH patients and 43 ± 20 vs 45 ± 15 mL/m2 in controls, p = 0.428).

Table 2 shows calculated values of Ees, Ea, Ees/Ea-P and SV/ESV for PAH patients and controls. Ees and Ea were increased in PAH patients, and Ees correlated with levels of mPAP, and inversely with pulmonary vascular compliance (r = 0.574 and r = −0.619, both p<0.001). Both Ees/Ea-P and SV/ESV were lower in PAH patients, and inversely correlated with mPAP, r = −0.345 and −0.607 respectively, both p<0.001.

Table 2.

End systolic elastance (Ees), arterial elastance (Ea) and RV-arterial coupling for PAH patients in comparison to control subjects with mPAP <25mmHg.

| Variable | PAH | Controls | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 84 | 22 | |

| Ees (mmHg/mL) | 1.26 ± 0.69 | 0.42 ± 0.26 | <0.001 |

| Ea (mmHg/mL) | 1.10 ± 0.57 | 0.26 ± 0.11 | <0.001 |

| Ees/Ea-P | 1.27 ± 0.60 | 1.69 ± 0.54 | 0.004 |

| SV/ESV | 0.58 ± 0.37 | 1.51 ± 0.67 | <0.001 |

Mean ±sd shown. RV – arterial coupling calculated by the pressure method (Ees/Ea − P) and the volume method (SV/ESV).

Between IPAH and CTDPH patients, there was no difference in Ees/Ea-P, (1.25 ± 0.7 vs 1.30 ± 0.5 p=0.759) or SV/ESV (0.48 (0.29 − 0.80) vs 0.50 (0.29 − 0.87) p=0.637). 14 of the 26 CTDPH patients had systemic sclerosis associated PAH (Ssc-PAH). Ees/Ea-P and SV/ESV in comparison to IPAH patients was similar, 1.39 ± 0.5 (p=0.52) and 0.60 (0.30 − 0.89) (p = 0.44) respectively.

Both Ees/Ea-P and SV/ESV were moderate predictors of 6MWD in the whole cohort, r = 0.261 p = 0.004 and r = 0.271 p = 0.003 respectively, after adjustment for age. RVEF and SV were both superior predictors of 6MWD r = 0.325 and r = 0.509 respectively, both p<0.001. NTproBNP moderately correlated with Ees/Ea-P but strongly with SV/ESV, r = −0.325 p = 0.002 and r = −0.777 p<0.001 respectively.

Baseline survival analysis

In the cohort of 84 PAH patients whom had both Ees/Ea-P and SV/ESV measures of RV-arterial coupling, 40 deaths occurred in the follow up period. Median survivalwas 1167 days with a maximum of 2369 days. Higher Ea and RAP and lower compliance, SVI, RVEF and SV/ESV were predictive of poorer outcome on bivariate cox proportional hazards regression with age (shown in table 3). In a multivariate model with age, SVI, RAP and PVR, SV/ESV but not Ees/Ea - P independently predicted survival (HR 0.306 95% CI 0.160–0.810, p=0.014 and HR 0.681 95% CI 0.349–1.330 P = 0.261 respectively). RVEF independently predicted survival in the same multivariate model (HR 0.310 95% CI 0.097 – 0.996 p=0.049). Table 4 displays the multivariate model for SV/ESV, and table 5 for RVEF.

Table 3.

Bivariate Cox proportional hazard regression analysis for survival in 84 PAH patients.

| p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ees mmHg/mL | 1.254 | (0.855 – 1.839) | 0.247 |

| Ea mmHg/mL | 1.971 | (1.129 – 3.441) | 0.017 |

| Ees/Ea-P | 0.647 | (0.354 – 1.181) | 0.156 |

| SV/ESV | 0.388 | (0.218 – 0.690) | 0.001 |

| mPAP mmHg | 1.014 | (0.986 – 1.042) | 0.344 |

| RAP mmHg | 1.083 | (1.017 – 1.154) | 0.013 |

| CI L/min/m2 | 0.713 | (0.376 – 1.350) | 0.299 |

| SV/PP mL/mmHg | 0.290 | (0.108 – 0.776) | 0.014 |

| PVR Wood units | 1.057 | (0.993 – 1.126) | 0.081 |

| RVEF % | 0.256 | (0.107 – 0.614) | 0.002 |

| SVI mL/m2 | 0.949 | (0.910 – 0.989) | 0.013 |

Data shown hazard ratio (95% CI) unless otherwise stated.

All variables analysed with age.

Ees: end systolic elastance; Ea: arterial elastance; Ees/Ea-P: RV coupling pressure method; SV/ESV: RV coupling volumetric method; mPAP: mean pulmonary artery; RAP: right atrial pressure; CI: cardiac index; SV/PP: compliance; PVR: pulmonary vascular resistance; RVEF: right ventricular ejection fraction; SVI: stroke volume index.

Table 4.

Multivariate cox proportional hazards regression model for survival in PAH patients.

| p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age years | 1.057 | 1.024 – 1.091 | 0.001 |

| PVR Wood Units | 0.953 | 0.856 – 1.059 | 0.363 |

| RAP mmHg | 1.078 | 0.999 – 1.062 | 0.052 |

| SV/ESV | 0.306 | 0.160 – 0.810 | 0.014 |

| SVI, mL/m2 | 0.996 | 0.923 – 1.075 | 0.917 |

Data shown HR (95% CI) unless otherwise stated.

PVR: pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP: right atrial pressure; SV/ESV: RV coupling volumetric method; SVI: stroke volume index.

Table 5.

Multivariate cox proportional hazards regression model including RVEF as prognostic variable in PAH.

| p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age years | 1.055 | 1.022 – 1.089 | 0.001 |

| PVR Wood Units | 0.979 | 0.887 – 1.081 | 0.673 |

| RAP mmHg | 1.065 | 0.987 – 1.148 | 0.103 |

| RVEF % | 0.310 | 0.097 – 0.996 | 0.049 |

| SVI, mL/m2 | 0.990 | 0.996 – 1.070 | 0.802 |

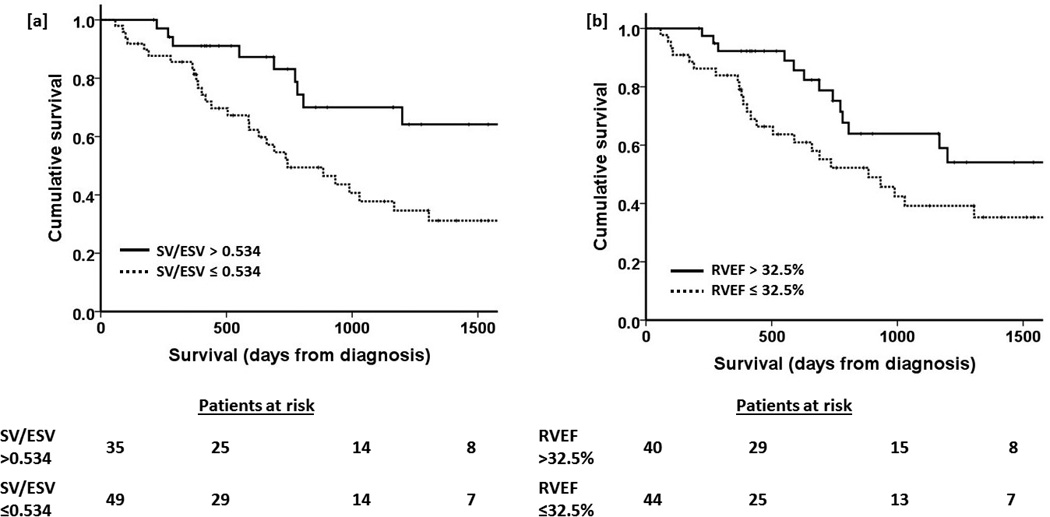

The Kaplan-Meyer survival curves according to cut off SV/ESV 0.534 and RVEF 32.5% as determined by Youden index from ROC curves are shown in Figure 1. SV/ESV <0.534 demonstrated 81% sensitivity, 50% specificity and RVEF <32.5% 73% sensitivity and 55% specificity for risk of death at 2 years. Survival was worse in PAH patients with SV/ESV < 0.534 (Logrank p=0.017) or RVEF <32.5% (p=0.04).

Figure 1.

Kaplan Meier survival curves describing survival rates of PAH patients stratified by [a] SV/ESV ≤ 0.534 and [b] RVEF > 32.5%. p values 0.017 and 0.040 respectively.

Change in SV/ESV with PH therapy

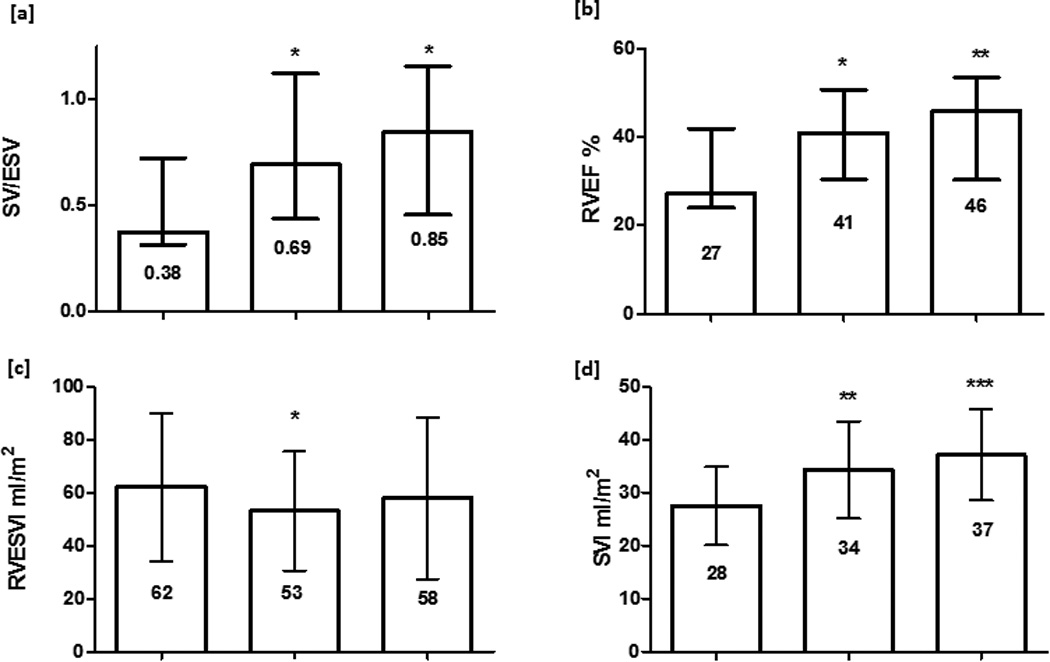

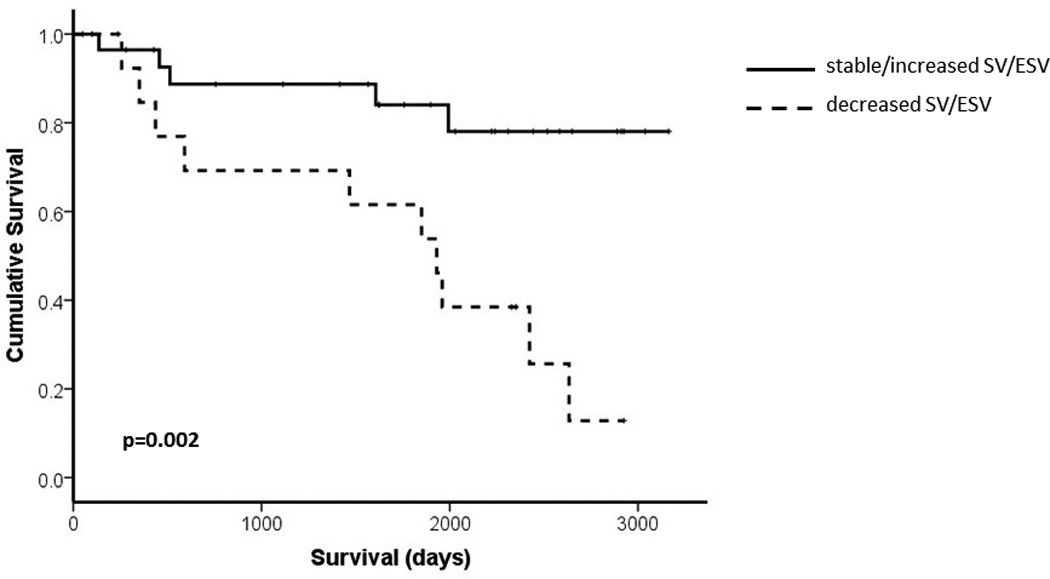

15 deaths occurred in the cohort of 44 patients who underwent interval CMR. 42 PAH patients (27 IPAH, 13 CTDPH, 2 POPH) had follow up CMR performed between 3 and 8 months after initiating PH therapy. SV/ESV, RVEF and SVI increased and RVESVI but not RVEDVI decreased with treatment. Table 6 shows baseline and follow up CMR variables at 3–8 months. 21 patients went on to have a further CMR performed at 12–18 months. Figure 2 shows serial CMR variables across the 3 studies. SV/ESV increased at 3–8 months and was maintained at 12–18 months, 0.38 (0.32 − 0.72) to 0.69 (0.44 − 1.12) to 0.85 (0.46 − 1.16), one way ANOVA p = 0.006. Patients with stable or increased SV/ESV (n=31) had better survival than those with decreased SV/ESV (n=13), p = 0.008. Figure 3 displays the KM survival curves for the two groups. All patients with decreased SV/ESV demonstrated significant decrease in RVEF (defined as change of ≥ 3%) [12].

Table 6.

Cardiac MRI variables of right ventricular function at diagnosis and following 3–8 months of therapy in 42 PAH patients.

| CMR Variable | Baseline | 3–8 months therapy | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| RVEF (%) | 35 ± 16 | 39 ± 15 | 0.002 |

| SV/ESV | 0.43 (0.29 – 0.85) | 0.62 (0.36 – 1.099) | 0.008 |

| RVESVI (mL/m2) | 61 ± 30 | 56 ± 26 | 0.036 |

| RVEDVI (mL/m2) | 93 (66 – 109) | 92 (53 – 118) | 0.726 |

| SVI (mL/m2) | 27 ± 8 | 32 ± 9 | 0.004 |

Data shown mean ± sd or median (IQR) depending on data distribution.

CMR: cardiac MRI; RVEF: right ventricular ejection fraction; SV/ESV: RV coupling volumetric method; RVESVI: right ventricular end systolic volume index; RVEDVI: right ventricular end diastolic volume index; SVI: stroke volume index.

Figure 2.

Serial CMR variables for 21 PAH patients performed at diagnosis, 3–8 months and 12–18 months after initiating PAH therapy. median (IQR) or mean (SD) shown. p value in comparison to baseline * p<0.05 ** p<0.01 *** p<0.001 [a]. SV/ESV [b] RVEF [d] SVI increased at 3–8months and were maintained at 12–18 months, one way ANOVA p = 0.006, p = 0.002 and p <0.001 respectively; [c] RVESVI fell at 3–8 months but was unchanged at 12–18 months, ANOVA p = 0.07; no change in RVEDVI occurred (data not shown). RVEF: right ventricular ejection fraction; SV/ESV: RV coupling volumetric method; RVESVI: right ventricular end systolic volume index; RVEDVI: right ventricular end diastolic volume index; SVI: stroke volume index.

Figure 3.

Kaplan Meier curve describing survival of PAH patients with decrease in SV/ESV (n= 13) or stable/increased SV/ESV (n=31) at follow up.

DISCUSSION

The present results show that CMR imaging of RV volumes allows for the prediction of outcome in PAH by RV function defined either as EF or SV/ESV. In this study, right heart catheterization-derived estimates of RV function such as RAP, SV or PVR or SV/PP did not independently predict outcome. Furthermore, there was no added value of combining invasive measurements of pressure with non-invasive measurements of volumes to assess RV-arterial coupling.

The present study confirms previous reports that RV contractility is increased with either preserved or decreased RV-arterial coupling in severe PH [9, 13–16]. Gold standard metrics of contractility and afterload in vivo are determined from a family of pressure-volume loops as maximum end-systolic and arterial elastances to determine an Ees/Ea relationship by a simple dimensionless number [1–3]. This is however difficult to implement at the bedside so simpler surrogates have been developed. The most straightforward are based of Ees/Ea either simplified for volume, the pressure method resulting in Pmax/mPAP-1 or simplified for pressure, the volume method resulting in SV/ESV. The pressure method relies on a Pmax calculation based on the analysis of a RV pressure curve to estimate maximum pressure of an isovolumic beat at EDV [4], and mPAP assumed equal to ESP [6]. While the pressure method generates Ees/Ea values that are quantitatively in the range of reported by more robust methods [9, 14–16], the number of assumptions in the method may result in insufficient precision and explain failure to predict outcome. The volume method rests on the indirect assumptions that Ees is a volume-independent straight line crossing the origin, which is not correct [2, 6, 9]. However, measurements of ESV and EDV by CMR have a high level of accuracy and precision, so that the information content of SV/ESV to estimate Ees/Ea is preserved and predicts outcome, confirming the previous report [9].

CMR imaging of RV EF has been previously reported to be a potent predictor of outcome in idiopathic PAH [7, 8]. The only study which compared EF to less preload-dependent SV/ESV showed the latter only to be an independent predictor of outcome, suggesting the less load-dependent measures of RV-arterial coupling might be clinically more relevant than EF [9]. In the present study, both SV/ESV and EF independently predicted outcome. These apparent discrepancies are to be explained by differences in background populations (in the previous report PH of mixed aetiology including group II disease was examined, and not all subjects subsequently received PH therapy) and high degree of colinearity between these measurements.

A right heart catheterization is mandatory for the diagnosis of PH [17]. However, the procedure allows for only an indirect decription of RV function, with RAP to estimate EDV, or preload, mPAP or PVR to estimate afterload, and SV to reflect contractility [2]. In spite of these limitations, RAP, cardiac output and PVR have been reported to predict outcome in PAH [18–23]. However, this was in studies considering exclusively these invasive measurements [2]. In the present study which combined right heart catheterization and CMR measurements, only imaging of RV function predicted outcome, in keeping with previous report [9]. This result agrees with the notion that imaging provides a more accurate and relevant definition of RV function than a standard right heart catheterization. In the multivariate model with SV/ESV p value for RAP neared significance (although less so when more commonly employed RVEF considered, p=0.103). It is therefore possible that RAP would emerge as statistically significant in a larger population, but it is an invasive measure. This study suggests that montoring of RV function with non-invasive imaging modalities in addition to being more acceptable to the patient yields stronger prognostic variables.

While other CMR studies of RV function have also reported on EF to independently predict outcome in IPAH [24], some rather focused on EDV [25] or ESV [26]. On the other hand, a large number of echocardiographic measures of RV systolic function and/or dimensions, or pericardial effusion [1, 2] and even biomarkers such as circulating brain natriuretic peptide [27, 28] have been shown to predict outcome as well. However, these studies were generally small with a limited number of variables, which limits extrapolation of their results to larger populations evaluated with invasive measurements and different imaging modalities and biomarkers. The resulting confusion is probably clarified by prioritizing the variables which are closest to gold standard measurements of RV function [2].

Treatment with PH therapies resulted in significant improvement in SV/ESV. In accordance with previous published work, improvements in SV and RVEF were also seen [8, 29, 30]. Deterioration in RV function during therapy is increasingly recognised as a poor prognostic sign. Van Wolferen et al showed that increasing RVEDVI or a further decrease in SV or left ventricular filling (left ventricular end diastolic volume – LVEDV) at 1 year of follow-up were the strongest predictors of mortality and treatment failure in patients with IPAH [7]. Veerdonk et al studied the relationship between the effect of PH therapy on changes in arterial load and RV function, and demonstrated that changes in PVR moderately correlated with change in RVEF [8]. However, in 25% of patients where improvement in PVR occurred, progressive RV dysfunction (defined by drop in RVEF) was seen and this deterioration was associated with poorer survival. PVR however represents only part of the afterload faced by the RV. Ea describes total RV afterload incorporating both resistive and pulsatile components. This is the first study to analyse the effect of therapy on volumetric measure of RV-arterial coupling in PAH.

There are several limitations to our study. This was a single centre retrospective observational study. The invasive RV trace analysis required manual digitisation from analogue traces for analysis. The RHC and CMR (and therefore pressure and volumes) were not performed simultaneously. There were however no changes in therapy between measurements. The single beat method employed requires several inherent assumptions, such as the use of a sine wave to approximate the waveform of isovolumetric contraction [31], but despite this Pmax generated from single beat method has shown excellent correlation with Pmax derived from multi-beat PV-loop analysis at varying levels of venous return [4]., which is the gold standard for measuring RV-arterial coupling and ideally should have been included for comparison.. These studies were not performed in this study as this would have required alteration of venous return through techniques such as inferior vena cava balloon occlusion with potential for complications and were felt unacceptable risk to the patient. Finally, therapy effect on RV-arterial coupling was solely assessed using CMR as it is not common practice in our centre for patients to routinely undergo haemodynamic monitoring with repeat right heart catheterization. How change in more established invasive measurements of RV-arterial coupling with treatment relates to outcome needs to be confirmed in further study.

CONCLUSION

RV function to predict survival in PAH is best determined by CMR measurements of SV/ESV or EF, without added value of invasively measured RV pressure measurements.

Acknowledgments

Dr Brewis has received assistance with travel and conference registration from Actelion, Pfizer and GSK. Dr Johnson has received honoraria, assistance with travel and research projects from Actelion, Bayer, and GSK. Professor Peacock has received Honoraria, assistance with travel and unrestricted research grants from Actelion, Bayer, GSK, Pfizer and United Therapeutics.

Funding Sources

Dr Vanderpool’s work is supported by a NIH T32 grant (T32 HL110849).

Dr. Chesler’s and Dr. Bellofiore’s work is supported by NIH 1R01HL105598.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr Bellofiore, Dr Vanderpool, Dr Chesler and Professor Naeije report no relationships that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

Part of this work has previously been published in abstract form:

Brewis MJ, Naeije R, Bellofiore A, Chesler N & Peacock AJ. Cardiac MRI derived right ventriculo-arterial coupling in pulmonary hypertension as a predictor of survival. Eur Resp J 2014; 44: Suppl 58, P2300

References

- 1.Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Haddad F, Chin KM, Forfia PR, Kawut SM, Lumens J, Naeije R, Newman J, Oudiz RJ, Provencher S, Torbicki A, Voelkel NF, Hassoun PM. Right heart adaptation to pulmonary arterial hypertension: physiology and pathobiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 Suppl):D22–D33. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naeije R. Assessment of right ventricular function in pulmonary hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2015;17(5):35. doi: 10.1007/s11906-015-0546-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maughan WL, Shoukas AA, Sagawa K, Weisfeldt ML. Instantaneous pressure-volume relationship of the canine right ventricle. Circ Res. 1979;44(3):309–315. doi: 10.1161/01.res.44.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brimioulle S, Wauthy P, Ewalenko P, Rondelet Bt, Vermeulen F, Kerbaul F, Naeije R. Single-beat estimation of right ventricular end-systolic pressure-volume relationship. American Journal of Physiology - Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2003;284(5):H1625–H1630. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01023.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanz J, Garcia-Alvarez A, Fernandez-Friera L, Nair A, Mirelis JG, Sawit ST, Pinney S, Fuster V. Right ventriculo-arterial coupling in pulmonary hypertension: a magnetic resonance study. Heart. 2012;98:238–243. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trip P, Kind T, van de Veerdonk MC, Marcus JT, de Man FS, Westerhof N, Vonk-Noordegraaf A. Accurate assessment of load-independent right ventricular systolic function in patients with pulmonary hypertension. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32(1):50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Wolferen SA, Marcus JT, Boonstra A, Marques KMJ, Bronzwaer JGF, Spreeuwenberg MD, Postmus PE, Vonk-Noordegraaf A. Prognostic value of right ventricular mass, volume, and function in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. European Heart Journal. 2007;28(10):1250–1257. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van de Veerdonk MC, Kind T, Marcus JT, Mauritz GJ, Heymans MW, Bogaard HJ, Boonstra A, Marques KM, Westerhof N, Vonk-Noordegraaf A. Progressive right ventricular dysfunction in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension responding to therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(24):2511–2519. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vanderpool RR, Pinsky MR, Naeije R, Deible C, Kosaraju V, Bunner C, Mathier MA, Lacomis J, Champion HC, Simon MA. RV-pulmonary arterial coupling predicts outcome in patients referred for pulmonary hypertension. Heart. 2015;101(1):7. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galie N, Hoeper MM, Humbert M, Torbicki A, Vachiery JL, Barbera JA, Beghetti M, Corris P, Gaine S, Gibbs JS, Gomez-Sanchez MA, Jondeau G, Klepetko W, Opitz C, Peacock A, Rubin L, Zellweger M, Simonneau G. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. European Respiratory Journal. 2009;34(6):1219–1263. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00139009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lorenz CH, Walker ES, Morgan VL, Klein SS, Graham TP., Jr Normal human right and left ventricular mass, systolic function, and gender differences by cine magnetic resonance imaging. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 1999;1(1):7–21. doi: 10.3109/10976649909080829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bradlow WM, Hughes ML, Keenan NG, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Assomull R, Gibbs JSR, Mohiaddin RH. Measuring the Heart in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH): Implications for Trial Study Size. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2010;31(1):117–124. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuehne T, Yilmaz S, Steendijk P, Moore P, Groenink M, Saaed M, Weber O, Higgins CB, Ewert P, Fleck E, Nagel E, Schulze-Neick I, Lange P. Magnetic resonance imaging analysis of right ventricular pressure-volume loops: in vivo validation and clinical application in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2004;110(14):2010–2016. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143138.02493.DD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tedford RJ, Mudd JO, Girgis RE, Mathai SC, Zaiman AL, Housten-Harris T, Boyce D, Kelemen BW, Bacher AC, Shah AA, Hummers LK, Wigley FM, Russell SD, Saggar R, Maughan WL, Hassoun PM, Kass DA. Right ventricular dysfunction in systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(5):953–963. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.000008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCabe C, White PA, Hoole SP, Axell RG, Priest AN, Gopalan D, Taboada D, MacKenzie Ross R, Morrell NW, Shapiro LM, Pepke-Zaba J. Right ventricular dysfunction in chronic thromboembolic obstruction of the pulmonary artery: a pressure-volume study using the conductance catheter. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2014;116(4):355–363. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01123.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spruijt OA, de Man FS, Groepenhoff H, Oosterveer F, Westerhof N, Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Bogaard HJ. The effects of exercise on right ventricular contractility and right ventricular-arterial coupling in pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(9):1050–1057. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201412-2271OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoeper MM, Bogaard HJ, Condliffe R, Frantz R, Khanna D, Kurzyna M, Langleben D, Manes A, Satoh T, Torres F, Wilkins MR, Badesch DB. Definitions and diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 Suppl):D42–D50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dalonzo GE, Barst RJ, Ayres SM, Bergofsky EH, Brundage BH, Detre KM, Fishman AP, Goldring RM, Groves BM, Kernis JT, Levy PS, Pietra GG, Reid LM, Reeves JT, Rich S, Vreim CE, Williams GW, Wu M. Survival in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension - results from a national prospective registry. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1991;115(5):343–349. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-5-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sandoval J, Bauerle O, Palomar A, Gomez A, Martinez-Guerra ML, Beltran M, Guerrero ML. Survival in primary pulmonary hypertension. Validation of a prognostic equation. Circulation. 1994;89(4):1733–1744. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.4.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McLaughlin VV, Shillington A, Rich S. Survival in primary pulmonary hypertension: the impact of epoprostenol therapy. Circulation. 2002;106(12):1477–1482. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000029100.82385.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sitbon O, Humbert M, Nunes H, Parent F, Garcia G, Herve P, Rainisio M, Simonneau G. Long-term intravenous epoprostenol infusion in primary pulmonary hypertension: prognostic factors and survival. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(4):780–788. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Humbert M, Sitbon O, Chaouat A, Bertocchi M, Habib G, Gressin V, Yaici A, Weitzenblum E, Cordier JF, Chabot F, Dromer C, Pison C, Reynaud-Gaubert M, Haloun A, Laurent M, Hachulla E, Cottin V, Degano B, Jais X, Montani D, Souza R, Simonneau G. Survival in Patients With Idiopathic, Familial, and Anorexigen-Associated Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension in the Modern Management Era. Circulation. 2010;122(2):156–163. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.911818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benza RL, Miller DP, Gomberg-Maitland M, Frantz RP, Foreman AJ, Coffey CS, Frost A, Barst RJ, Badesch DB, Elliott CG, Liou TG, McGoon MD. Predicting survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension: insights from the Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Disease Management (REVEAL) Circulation. 2010;122(2):164–172. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.898122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moledina S, Pandya B, Bartsota M, Mortensen KH, McMillan M, Quyam S, Taylor AM, Haworth SG, Schulze-Neick I, Muthurangu V. Prognostic significance of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in children with pulmonary hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6(3):407–414. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.000082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamada Y, Okuda S, Kataoka M, Tanimoto A, Tamura Y, Abe T, Okamura T, Fukuda K, Satoh T, Kuribayashi S. Prognostic value of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging for idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension before initiating intravenous prostacyclin therapy. Circ J. 2012;76(7):1737–1743. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-11-1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swift AJ, Rajaram S, Campbell MJ, Hurdman J, Thomas S, Capener D, Elliot C, Condliffe R, Wild JM, Kiely DG. Prognostic value of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging measurements corrected for age and sex in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7(1):100–106. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.000338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagaya N, Nishikimi T, Uematsu M, Satoh T, Kyotani S, Sakamaki F, Kakishita M, Fukushima K, Okano Y, Nakanishi N, Miyatake K, Kangawa K. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide as a prognostic indicator in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2000;102(8):865–870. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.8.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mauritz GJ, Rizopoulos D, Groepenhoff H, Tiede H, Felix J, Eilers P, Bosboom J, Postmus PE, Westerhof N, Vonk-Noordegraaf A. Usefulness of serial N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide measurements for determining prognosis in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108(11):1645–1650. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Wolferen SA, Boonstra A, Marcus JT, Marques KMJ, Bronzwaer JGF, Postmus PE, Vonk-Noordegraaf A. Right ventricular reverse remodelling after sildenafil in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Heart. 2006;92(12):1860–1861. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.085118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peacock AJ, Crawley S, McLure L, Blyth K, Vizza CD, Poscia R, Francone M, Iacucci I, Olschewski H, Kovacs G, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Marcus JT, van de Veerdonk MC, Oosterveer FP. Changes in right ventricular function measured by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in patients receiving pulmonary arterial hypertension-targeted therapy: the EURO-MR study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7(1):107–114. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.000629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bellofiore A, Chesler NC. Methods for measuring right ventricular function and hemodynamic coupling with the pulmonary vasculature. Ann Biomed Eng. 2013;41(7):1384–1398. doi: 10.1007/s10439-013-0752-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]