Abstract

The PI3K-Akt-mTORC1 pathway is a highly dynamic network that is balanced and stabilized by a number of feedback inhibition loops1, 2. Specifically, activation of mTORC1 has been shown to lead to the inhibition of its upstream growth factor signaling. Activation of the growth factor receptors is triggered by the binding of their cognate ligands in the extracellular space. However, whether secreted proteins contribute to the mTORC1-dependent feedback loops remains unclear. We found that cells with hyperactive mTORC1 secrete a protein that potently inhibits the function of IGF-1. Using a large-scale, unbiased quantitative proteomic platform, we comprehensively characterized the rapamycin-sensitive secretome in TSC2−/− MEFs, and identified IGFBP5 as a secreted, mTORC1 downstream effector protein. IGFBP5 is a direct transcriptional target of HIF1, which itself is a known mTORC1 target3. IGFBP5 is a potent inhibitor of both the signaling and functional outputs of IGF-1. Once secreted, IGFBP5 cooperates with intracellular branches of the feedback mechanisms to block the activation of IGF-1 signaling. Finally, IGFBP5 is a potential tumor suppressor, and the proliferation of IGFBP5-mutated cancer cells are selectively blocked by IGF-1R inhibitors.

The evolutionarily conserved Ser/Thr kinase mTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin) is a central regulator of cell growth and proliferation. mTOR is distributed into two complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2. The upstream inputs regulating mTORC1 have been extensively characterized. Multiple signals (e.g. from growth factors and tumor-promoting phorbol esters) converge upon the heterodimeric TSC1/2 (Tuberous Sclerosis Complex) protein complex to regulate the activation of mTORC1, in a Rheb-dependent manner1, 2. In addition, mTORC1 activity is also under the tight control of cellular amino acids levels4.

The best-known mTORC1 substrates are the eIF4E-binding proteins (4EBPs) and the ribosomal protein S6-kinases (S6K), both of which are known to regulate protein synthesis5. Recently, we and others have used large-scale quantitative mass spectrometry experiments to comprehensively characterize the mTORC1-regulated phosphoproteome6–8. These studies measured, on a global level, the changes in protein phosphorylation upon rapamycin treatment, and in so doing, identified additional mTORC1 substrates (e.g. the growth factor receptor binding protein 10, Grb10)6, 8.

Downstream effector proteins of mTORC1 are known to communicate with its upstream regulators (e.g. receptor tyrosine kinases, RTKs), through various feedback loops9. These feedback mechanisms play a critical role in maintaining the stability of the entire network. They also have great significance in a variety of diseases. In particular, mTORC1 is hyperactivated in many human cancers, as a result of mutations of upstream oncogenes and tumor suppressors (e.g. PI3K, PTEN, Akt, TSC1/2, etc)2, or mTOR itself10. In most of the cases, rapamycin or mTOR kinase inhibitors, however, fail to kill tumor cells11.

Recent studies have suggested multiple mechanisms of rapamycin resistance. For example, tumors could develop mTOR mutations that prevent the binding of rapamycin to the protein by means of steric hindrance12. In addition, rapamycin resistance could also stem from the relief of mTORC1-mediated feedback inhibition loops2. Specifically, mTORC1 inhibition could activate growth factor signaling, providing an alternative means of promoting cell survival and proliferation, under these mTORC1-repressed conditions13. A number of studies have demonstrated that the feedback mechanisms involve mTORC1/S6K targeting growth factor receptors14, 15, proteins that bind to RTKs (e.g. IRS116, 17 and Grb106, 8) and more downstream mTORC2 (through phosphorylation of mSin1)18, 19. These feedback mechanisms, however, only partially account for the mTORC1-dependent inhibitory activity towards growth factor signaling. We realize that the abovementioned molecules (i.e. Grb10, IRS1 and mSin1) are intracellular proteins. However, activation of RTKs is triggered by the binding of their cognate ligands in the extracellular space. Whether secreted proteins contribute to mTORC1-dependent feedback mechanisms is unknown.

To address this question, we serum-starved a pair of isogenic TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs in DMEM for 24 hrs, and collected their conditioned media (CM). Loss of TSC2 disengages mTORC1 from the upstream inputs, resulting in its constitutive activation, even in serum-free media8, 20. As a result, these cells are resistant to serum deprivation-induced apoptosis (Supplementary Figure 1A). They also possess potent mTORC1-dependent feedback loops (Supplementary Figure 1B).

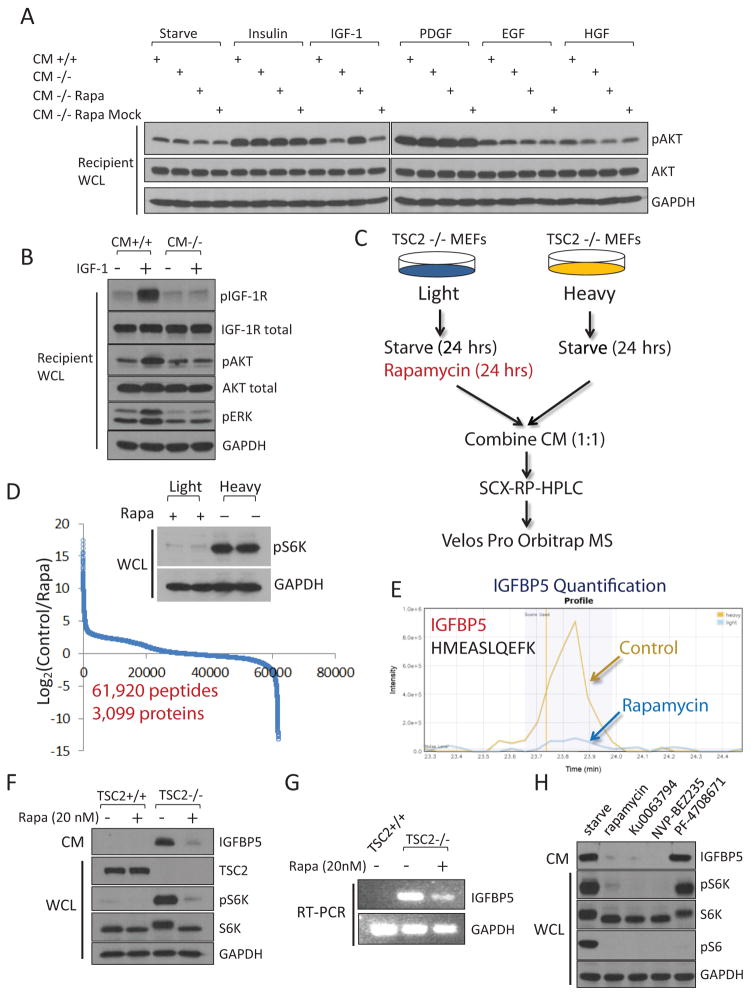

We mixed the corresponding CM with various growth factors, including insulin, IGF-1, PDGF, EGF and HGF. These CM samples were then incubated with separate plates of regular wt MEFs (Figure 1A). We found that IGF-1 was only able to activate IGF1R and Akt in recipient cells when it was mixed with CM from TSC2+/+ cells, but not with that from TSC2−/− cells (Figure 1A and 1B). Activity of the other growth factors was not affected by TSC2−/− CM. Remarkably, this IGF-1-inhibitory activity was abrogated in CM from TSC2−/− cells that had been treated with rapamycin for 24 hrs (Figure 1A). Here because this CM contained rapamycin, there was also a possibility that the observed restoration of IGF-1 signaling was a direct effect of rapamycin on the recipient cells. We performed control experiments where we collected CM from TSC2−/− cells, and then mixed it with rapamycin. We found that this mock-treatment media retained the ability to inhibit IGF-1 (Figure 1A). The simplest hypothesis that is consistent with these observations would be that cells with hyperactive mTORC1 secrete a factor(s) that is able to block the function of IGF-1.

Figure 1.

Cells with hyperactivated mTORC1 secrete a protein factor(s) that blocks IGF-1 signaling. (A) Conditioned media was collected from TSC2+/+ MEFs (CM+/+) or TSC2−/− MEFs (CM−/−), mixed with the indicated growth factor, and were then incubated with regular wt MEFs (designated as “recipient cells”) for 10 min. CM that was not mixed with any growth factors was indicated as “starve”. CM was also collected from TSC2−/− MEFs that had been treated with 20 nM rapamycin for 24 hrs (CM−/− Rapa). As a control experiment, CM from TSC2−/− cells were collected first, and then mixed with rapamycin (CM−/− Rapa Mock). For site-specific phosphorylation, pAkt(S473) levels were analyzed. Growth factor concentrations are Insulin, 100 nM; IGF-1, 40 ng/ml; PDGF, 50 ng/ml; EGF, 50 ng/ml and HGF, 50 ng/ml. (B) CM from TSC2−/− MEFs is able to block the activation of the IGF-1 signaling pathway. Experiments were performed as in (A). pIGF-1R(Y1135/1136), pAkt(S473), and pERK(T202/Y204) levels were analyzed. (C) A gerneral schematic of the quantitative secretomic platform. (D) Ratio distribution of the identified peptides (a total of 63,157 from 3,430 proteins). Ratio (control/rapamycin-treated) distribution of these peptides is shown on a Log2 scale. Light and heavy lysates were also subject to immunoblotting analysis for pS6K(T389) levels. (E) Extracted ion chromatogram of the light (rapamycin-treated, blue) and heavy (control, yellow) ions of an IGFBP5 peptide (HMEASLQEFK). (F) CM from TSC2−/− MEFs, but not TSC2+/+ MEFs, contains high levels of IGFBP5. Cells were starved for 24 hrs, after which CM was collected. When indicated, cells were also treated with rapamycin (20 nM for 24 hrs). CM and WCL of these cells were analyzed by using immunoblotting experiments for pS6K(T389) levels. (G) IGFBP5 expression is regulated by mTORC1 at the transcription level. Total RNA was extracted from TSC2+/+, TSC2−/− MEFs, or TSC2−/− MEFs that had been treated with 20 nM rapamycin for 24 hrs, and was analyzed. (H) Treatment of TSC2−/− MEFs by rapamycin (20 nM), Ku0063794 (1 μM) and NVP-BEZ235 (500 nM), but not an S6K inhibitor (PF-4708671, 10 μM), led to downregulation of IGFBP5 in CM. For site-specific phosphorylation, pS6K(T389) and pS6(S235/236) levels were analyzed.

TSC2−/− CM that had been heated to 95 ºC completely lost its ability to inhibit IGF-1, suggesting that this factor might be a protein (Supplementary Figure 1C). This experiment also ruled out the possibility that the observed effect was because mTORC1 activation inhibits the accumulation of an IGF-1-pontentiating protein (in which case, heating the CM from TSC2−/− cells would not affect its ability to modulate IGF-1 signaling).

We sought to identify this mTORC1-regulated, secreted protein factor(s) that has IGF-1-inhibitory activity. Mass spectrometric analysis of secreted proteins, however, is technically challenging, due to their often exceedingly low abundances21. By coupling multi-dimensional HPLC separation with a Velos Pro Orbitrap mass spectrometer, we established a high sensitivity mass spectrometry platform for comprehensive secretomic analysis (Figure 1C).

Although uncontrolled activation of mTORC1 is the best studied and the predominant consequent of TSC2 loss, there could be mTORC1-independent functions from TSC2 loss. These functions might also regulate the expression of secreted proteins. We therefore focused on identifying secreted proteins whose expression was altered as a result of rapamycin treatment. We used the SILAC (stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture) approach8, 22 as the quantification method (Figure 1C). Both light and heavy TSC2−/− MEFs were serum-deprived for 24 hours, during which light cells were rapamycin-treated (Figure 1D). CM from the light and heavy cells were collected, combined (at a 1:1 ratio at the protein level) and analyzed by the abovementioned quantitative secretomic platform.

From this SILAC CM sample, we identified and quantified a total of 61,920 peptides from 3,099 proteins (peptide false discovery rate = 0.27 %) (Figure 1D, Supplementary Figure 1D and Supplementary Table 4–7). mTORC1 inhibition leads to a drastic change in the secretome. Specifically, 355 and 145 proteins showed a decrease and increase in their abundances, by at least 32-fold, respectively, after rapamycin treatment (Figure 1D). For example, the abundance of fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) dramatically decreased after rapamycin treatment (Supplementary Figure 1E). FGF21 is a secreted hormone whose expression is known to be regulated by mTORC123. The identification of this known mTORC1 downstream target in the extracellular space validates the robustness of our quantitative secretomic approach.

Because rapamycin treatment abrogated the expression of the IGF-1-inhibitory protein (Figure 1A), we focused our follow up analysis on proteins whose abundances decreased as a result of mTORC1 inhibition. Gene ontology (cellular compartment) analysis of these proteins showed that they were enriched for extracellular matrix proteins (P =6.5×10−10) (Supplementary Figure 2A). Intriguingly, one of the enriched molecular function categories was growth factor binding proteins (P = 1.7 × 10−4) (Supplementary Figure 2B). In particular, the level of IGFBP5 (IGF binding protein 5) decreased dramatically (by approximately 68-fold, similar change was found in the replicate SILAC experiment) after rapamycin treatment (Figure 1E and Supplementary Figure 1F).

IGFBPs are secreted proteins that are known to bind to circulating IGF-124. Interestingly, another member of the IGFBP family, IGFBP3, has recently been shown to be regulated by mTORC225. We confirmed that TSC2−/− contained high levels of IGFBP5 at both the protein (in CM) and mRNA levels (Figure 1F and 1G). Conversely, this protein was virtually absent in CM from TSC2+/+ MEFs. To rule out the possibility that these observation is due to artifacts resulting from in vitro culturing of these isogenic cells, we generated TSC2-reconstituted cells by introducing TSC2 back into TSC2−/− MEFs. Indeed, these “wild-type” cells also contained undetectable levels of secreted IGFBP5 (Supplementary Figure 1G).

Inhibition of mTORC1 in TSC2−/− MEFs by either rapamycin or mTOR kinase inhibitors (Ku0063794 and NVP-BEZ2358) resulted in a dramatic decrease of IGFBP5 (Figure 1F, 1G and 1H). In contrast, treatment of these cells with an S6K inhibitor, PF-470867126, had no effect on IGFBP5 levels (Figure 1H). These results indicate that mTORC1 itself, rather than S6K, regulates the expression of IGFBP5. mTORC1 also regulates the expression of IGFBP5 in other cell lines (RT-4 and MCF7, Supplementary Figure 1H and Supplementary Figure 1I).

Because the mRNA level of IGFBP5 positively correlated with mTORC1 activity (Figure 1G), we reasoned that transcription regulation might contribute to mTORC1-dependent IGFBP5 expression. Several transcription factors are known to function downstream of mTORC1, including sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP), c-Myc and HIF1 (Hypoxia-inducible factor 1)27–29. HIF1 is of particular interest because it modulates the expression of a number of secreted proteins (e.g. VEGF)30. Activation of mTORC1 promotes the synthesis of HIF1α, specifically through enhancing the translation of its mRNA that contains long and structured 5′ UTRs3.

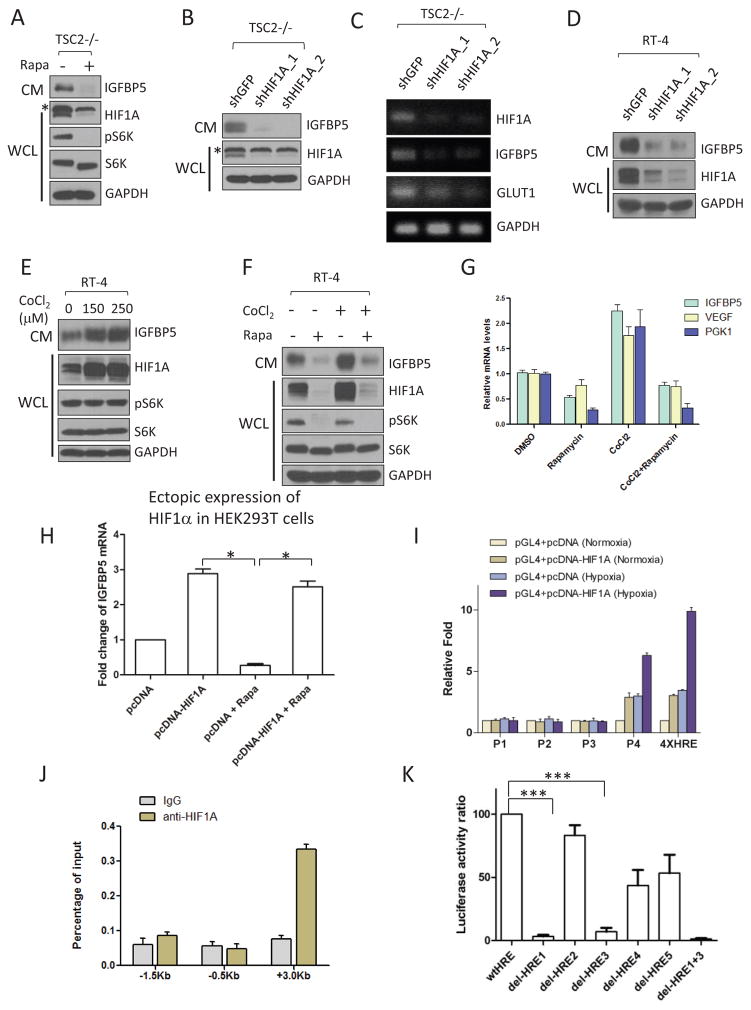

Consistent with previous studies27, we found that rapamycin treatment dramatically lowered the expression of HIF1α and, concomitantly, IGFBP5 in TSC2−/− MEFs (Figure 2A). A similar decrease in IGFBP5 was observed when HIF1α was knocked down using RNAi (RNA interference) in TSC2−/− MEFs (Figure 2B and 2C) and RT-4 cells (Figure 2D). We found that HIF1 was also sufficient for IGFBP5 expression. Specifically, treatment of RT-4 cells with a hypoxia-mimetic agent, CoCl230, led to robust accumulation of HIF1α and IGFBP5 (in CM) (Figure 2E). Importantly, co-treatment of CoCl2 and rapamycin suppressed HIF1α and IGFBP5 expression to levels even lower than CoCl2-untreated samples (Figure 2F and 2G), suggesting a dominant effect from mTORC1 inhibition. IGFBP5 expression is no longer sensitive to rapamycin treatment in an ectopic expression system (the construct does not contain the highly structured 5′-UTR of HIF1α), suggesting that the effect of rapamycin on IGFBP5 expression is dependent on mTORC1-mediated translation of HIF1α (Figure 2H).

Figure 2.

Expression of IGFBP5 is transcriptionally regulated by HIF1α. (A) Rapamycin treatment (20 nM, 24hrs) of TSC2−/− MEFs led to a concurrent downregulation of HIFα (in WCL) and IGFBP5 (in CM). The asterisk indicates a non-specific band. For site-specific phosphorylation, pS6K(T389) levels were analyzed. (B) and (C) RNAi-mediated knockdown of HIFα in TSC2−/− MEFs led to downregulation of IGFBP5 at both protein (B) and mRNA (C) levels. Glut1 is a known transcriptional target of HIFα, and was used as a positive control. The asterisk indicates a non-specific band. (D) Knockdown of HIF1α in RT-4 cells led to a similar downregulation of IGFBP5 levels in CM. (E) Treating RT-4 cells with a hypoxic-mimetic, CoCl2 (24 hrs with the indicated concentrations), led to stabilization of HIF1α in WCL, and accumulation of IGFBP5 in CM. Concurrent treatment of RT-4 cells with CoCl2 (250 μM) and rapamycin (20 nM) abolished IGFBP5 expression at the protein (F) and mRNA (G) levels. P < 0.05 (two way ANOVA test). n=3 independent biological replicate experiments. Error bars represent s. d. (H) IGFBP5 expression is insensitive to mTORC1 inhibition (rapamycin at 20 nM, 24 hrs) in a HIF1α-ectopic expression system. HEK293T cells were transfected with either a pcDNA-HIF1α or a control vector. IGFBP5 mRNA levels were determined by quantitative RT-PCR. *P < 0.05 (two-tailed Student t-test). n = 3 independent biological replicate experiments; Error bars represent s.d. (I) Luciferase reporter assays indicate that the first intron (designed as P4, see Supplementary Figure 3) of the IGFBP5 gene contains functional HREs. Luciferase activities were normalized to Renella luciferase. Hypoxia was induced by growing the cells in a hypoxia chamber (1% O2). A luciferase reporter construct containing 4X HRE (from Promega) was used as the positive control. P <0.001 (two way ANOVA test). n=3 independent biological replicate experiments. Error bars represent s.d. (J) ChIP qRT-PCR confirmation of the binding between HIF1α and the potential HREs in the P4 region. P <0.001 (two way ANOVA test). n=3 independent biological replicate experiments. Error bars represent s.d. (K) Deletion of HRE1 and HRE3 (Supplementary Figure 3) in the P4 region of the IGFBP5 gene abolishes the binding of HIF1α in the luciferase assay. ***P < 0.001 (two-tailed Student t-test). n = 3 independent biological replicate experiments; Error bars represent s.d.

To explore whether HIF1 directly regulates the transcription of IGFBP5, we screened a series of pGL4 luciferase reporter constructs harboring inserts representing different regions of the IGFBP5 gene (Supplementary Figure 3). We found that the expression of one construct (pGL4-P4-luc) that carries a 300 bp (from +2.9 Kb to +3.2 Kb) fragment downstream of the IGFBP5 transcription start site (TSS) in HEK293T cells led to a dramatic increase in luciferase activity, when these cells were co-transfected with a pcDNA3-HIF1α plasmid (Figure 2I). These data suggest that there could be potential HIF-responsive elements (HREs) in this region of the IGFBP5 gene. Chromatin immunoprecipitation-quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR) experiments then confirmed the existence of such HREs (Figure 2J).

Based on the consensus binding motifs of HIF1 (5′-CGTG-3′)31, we identified a total of 5 potential HREs in this region (HRE1-HRE5, Supplementary Figure 3). We found that the deletion of either HRE1 or HRE3 drastically lowered the binding of HIF1 in the luciferase assay. HIF1 completely lost its ability to recognize the IGFBP5 mutant that has been deleted for both HRE1 and HRE3, indicating these two HREs are the most important sites for HIF1-dependent transcription regulation of IGFBP5 (Figure 2K). Taken together, these data demonstrate that HIF1α regulates the transcription of IGFBP5 through directly binding to its HREs.

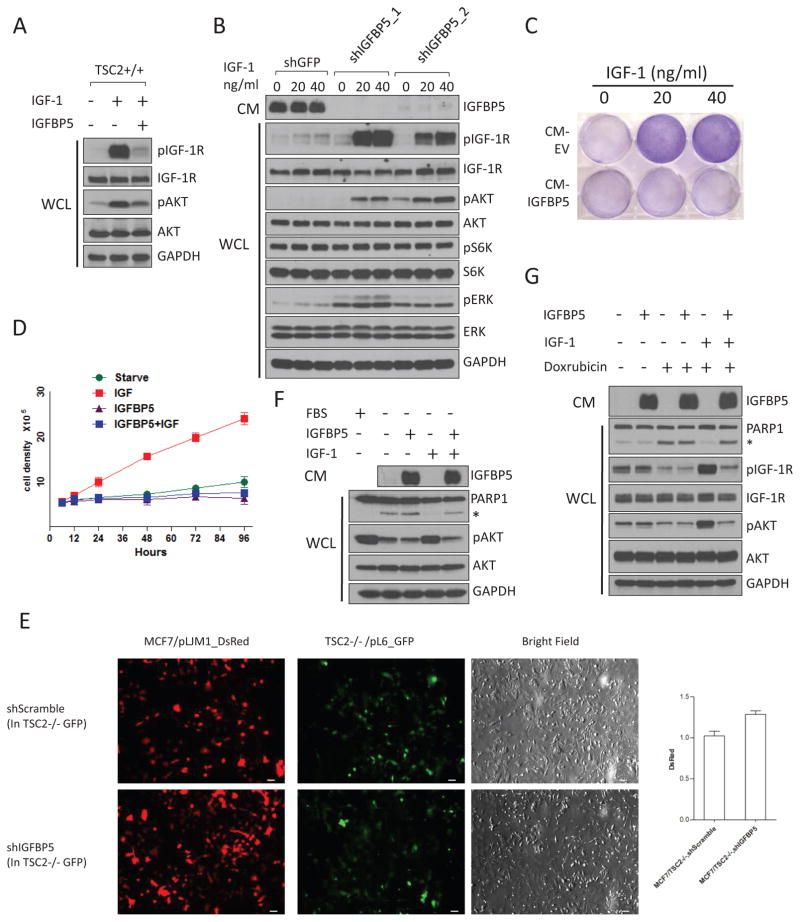

IGFBP5 is known to bind, with high affinity, to circulating IGFs24. However, it remains controversial whether IGFBP5 impacts IGF-1 signaling in a positive or negative manner. IGFBP5 could block IGF-1 signaling by binding to, and sequestering it from interacting with IGF-1R32. On the other side, IGFBP5 might also potentiate the function of IGF-1, presumably by better presenting IGF-1 to IGF-1R33. We found that the addition of IGFBP5 to the media resulted in strong inhibition of IGF-1 signaling in wt MEFs (Figure 3A). We found that IGFBP5 is also necessary for the IGF-1-inhibitory activity in TSC2−/− CM. TSC2−/− MEFs are characterized by a profound “IGF-1-resistant” state, as indicated by their lack of response to IGF-1 (Figure 3B). Intriguingly, depletion of IGFBP5 in TSC2−/− MEFs greatly sensitizes them to IGF-1 stimulation (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

IGFBP5 is a potent inhibitor of IGF-1 signaling. (A) Addition of recombinant IGFBP5 (R&D systems) to culture media blocks IGF-1-induced activation (20 ng/ml, 5 mins) of IGF-1R (pIGF-1R(Y1135/1136)) and Akt (pAkt(S473)) in wt MEFs. (B) Knockdown of IGFBP5 in TSC2−/− MEFs led to strong activation of IGF-1R and its downstream kinases (Akt and ERK), in response to IGF stimulation. Cells were starved overnight, and were stimulated with IGF (20 ng/ml, 5 mins). For site-specific phosphorylation, pIGF-1R(Y1135/1136), pAkt(S473), pS6K(T389) and pERK(T202/Y204) levels were analyzed. (C) and (D) Addition of IGFBP5 to culture media blocked IGF-1-induced cell proliferation. MCF7 cells were starved, and were then treated with IGF-1 mixed with CM from HEK293T cells transfected with an empty vector, or an IGFBP5-expressing construct, respectively. Cells were stained by crystal violet (C) (after 48 hrs), or counted (D). P <0.001 (two-way ANOVA test). n=9 independent biological replicate experiments. Error bars represent s.d. (E) IGFBP5 secreted from TSC2−/− MEFs inhibits the growth of MCF7 cells in a co-culture system. MCF7 cells were labeled with red florescent protein (DsRed), and were growth with GFP-labeled TSC2−/− MEFs with either control-knock down, or IGFBP5-knock down. Cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with IGF-1 (40 ng/ml), with fluorescence signal intensities quantified for the green and red channels. P <0.05 (two-tailed student t-test). n =3 independent biological replicate experiments. Error bars represent s.d. Scale bars, 40 μm. (F) The presence of IGF (40 ng/ml) in culture media protected cells from starvation-induced apoptosis. This effect, however, is blocked by the addition of IGFBP5. The asterisk indicates cleaved PARP1. CM from HEK293T cells transfected with an IGFBP5-expressing construct was used as the source of IGFBP5. For site-specific phosphorylation, pAkt(S473) levels were analyzed. (G) The presence of IGF-1 in culture media protected cells from Doxorubicin-induced (1 μM, 6 hrs) apoptosis. This effect was blocked by the addition of IGFBP5. MCF7 cells were starved overnight, and were treated with doxorubicin in the presence of IGF (40 ng/ml) or IGF+IGFBP5. CM from HEK293T cells transfected with an IGFBP5-expressing construct was used as the source of IGFBP5. For site-specific phosphorylation, pIGF-1R(Y1135/1136) and pAkt(S473) levels were analyzed.

We next examined whether IGFBP5 also inhibits the functional outputs of IGF-1. We found that the addition of IGFBP5 to culture media completely blocked IGF-1-induced proliferation of MCF7 cells (Figure 3C and 3D). Because IGFBP5 is a secreted protein that functions in the extracellular space, it may also provide a “non-cell autonomous” mechanism for mTORC1 to regulate the growth and proliferation of adjacent cells. We tested this hypothesis using a co-culture system. Specifically, MCF7 cells were labeled with red florescent protein (DsRed, RFP), and were grown with GFP-labeled TSC2+/+ or TSC2−/− MEFs. Interestingly, the proliferation of MCF7 cells was dramatically suppressed when they were co-cultured with TSC2−/− MEFs (Supplementary Figure 4A), an effect that can be ascribed to IGFBP5 (Figure 3E).

We investigated whether IGFBP5 can modulate the anti-apoptosis function of IGF-1. We found that IGF-1 could block starvation-induced apoptosis of MCF7 cells, which was reversed when IGFBP5 is present in the media (Figure 4F). Furthermore, IGFBP5 also blocks the pro-survival effect of IGF-1 when cells were treated with cytotoxic agents, including staurosporine, etoposide and doxorubicin (Figure 3G, Supplementary Figure 4B and Supplementary Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

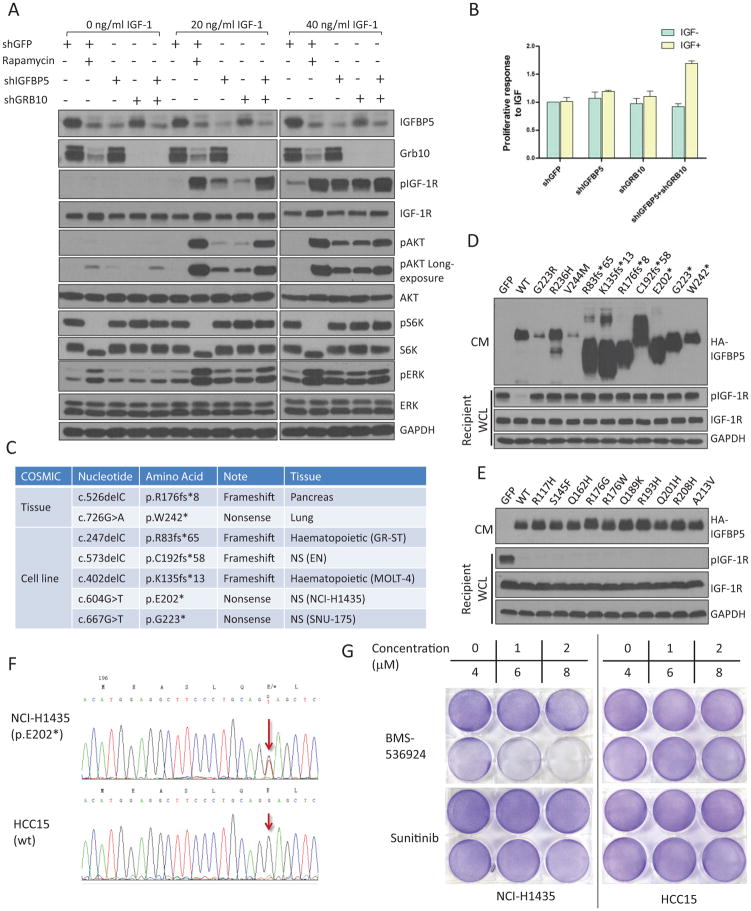

IGFBP5 is a major mediator of mTORC1-dependent feedback inhibition of IGF-1 signaling. (A) IGFBP5 and Grb10 together account for a major faction of the IGF-1-inhibitory activity of mTORC1. We generated TSC2−/− MEFs with single IGFBP5 or Grb10 knockdown, as well as IGFBP5+Grb10 double knockdown. Where indicated, cells were also treated with rapamycin (20 nM for 24 hrs). Cells were stimulated with IGF-1 (at indicated concentrations). For site-specific phosphorylation, pIGF-1R(Y1135/1136), pAkt(S473), pS6K(T389) and pERK(T202/Y204) levels were analyzed. (B) Grb10 and IGFBP5 double knock down cells show increased proliferative responses in IGF-1-supplemented media. P <0.001 (two-way ANOVA test). n=9 independent biological replicate experiments. Error bars represent s.d. (C) Cancer-associated frameshift and nonsense mutations that have been reported for IGFBP5 (data from COSMIC). A complete list of the somatic mutations is shown in Supplementary Table 8. (D) and (E) IGFBP5 expression constructs harboring cancer-associated mutations were transfected into HEK293T cells. Cells were starved, and the corresponding CM was collected, mixed with IGF-1 and was incubated with wild-type MEFs (recipient cells). WCL was analyzed by immunoblotting experiments using the indicated antibodies. Cancer-associated mutations of IGFBP5 are shown that either disrupt (D) or maintain (E) its IGF-1-inhibitory activity. For site-specific phosphorylation, pIGF-1R(Y1135/1136) levels were analyzed. (F) NCI-H1435 cells harbor heterozygous IGFBP5 mutation (E202*). Genomic fragment in the 3rd exon of IGFBP5 from NCI-H1435 and HCC15 cell lines were amplified with PCR and were sequenced. The red arrows indicate the mutation (G to T) in the NCI-H1435 cell line. HCC15 cells contain wt IGFBP5. (G) NCI-H1435 cell line is sensitive to IGF-1R inhibitor, BMS-536924. NCI-H1435 and HCC15 NSCLC cell lines were seeded overnight in 6 well plates at the same density. After 48 hours treatment with BMS-536924 or Sunitinib, 6 well plates were fixed with methanol and then were stained with crystal violet.

Activation of mTORC1 triggers a number of feedback loops that converge on, and antagonize IGF-1 signaling9. We sought to determine the relative contribution of IGFBP5, compared to the known players in these feedback loops. First, we asked the question of how much of the IGF-1-inhibitory activity in TSC2−/− CM could be attributed to IGFBP5. We collected CM from TSC2−/− MEFs with either control or IGFBP5 knock down, mixed them with IGF-1, and treated wild-type MEFs. We found that the degree of IGF-1R activation in the recipient cells using the shIGFBP5 TSC2−/− CM is approximately 85% of that using the TSC2+/+ CM, indicating that IGFBP5 accounts for a large fraction of the IGF-1-inhibitory activity in TSC2−/− CM (Supplementary Figure 4D).

We next examined, on the whole cell level, IGF-1 signaling in TSC2−/− MEFs that were treated with either rapamycin or shIGFBP5. Both treatments greatly sensitized these cells to IGF-1 stimulation (Supplementary Figure 4E). We, at the same time, did observe that a lower pIGF-1R and pAkt level in shIGFBP5 TSC2−/− MEFs, compared to that in rapamycin-treated shGFP TSC2−/− MEFs (Supplementary Figure 4E). We then generated TSC2−/− cells with single knock down of either Grb10 or IGFBP5, as well as cells with Grb10 and IGFBP5 double knock down (Figure 4A). Compared with rapamycin treatment, knockdown of either Grb10 or IGFBP5 partially recovered IGF-1-dependent Akt activation. However, TSC2−/− MEFs co-depleted for both Grb10 and IGFBP5 almost completely regained IGF-1 sensitivity (Figure 4A). Finally, double knockdown of Grb10 and IGFBP5 also dramatically accelerates the proliferation of TSC2−/− cells, in response to IGF-1 stimulation (Figure 4B).

We previously showed that Grb10 is a potential tumor suppressor8. Because IGFBP5 also inhibits the function of IGF-1 (Figure 4A), it might be another tumor suppressor downstream of mTORC1. Indeed, at least 20 nonsynonymous somatic mutations have been identified for IGFBP5 in cancer (COSMIC database) (Supplementary Table 8), including four frameshift (R83fs*65, K135fs*13, R176fs*8 and C192fs*58) and three nonsense mutations (E202*, G223* and W242*) (Figure 4C). We generated mammalian expression constructs (with a C-terminal HA tag) harboring the individual mutations that have been reported for IGFBP5. We ectopically expressed them in HEK293T cells, collected the corresponding CM, and mixed them with IGF-1. These CM samples were added to wt MEFs (Figure 4D and 4E). Intriguingly, half of these cancer-associated IGFBP5 mutants completely lost their IGF-1-inhibitory activity, including the abovementioned truncation mutations, as well as three additional point mutations (G223R, R236H and V244M) (Figure 4D).

Hyperactivation of IGF-1 signaling plays a critical role in establishing a transformed phenotype in a number of malignancies34. The development of IGF-1R inhibitors, however, have been largely unsuccessful, in part due to the lack of a viable approach for patient stratification35. We reasoned that the loss of IGFBP5 might drive the survival and proliferation of a cancer cell dependent on IGF-1 signaling. This, in turn, might confer their sensitivity to IGF-1R inhibitors. From the COSMIC database, we identified that NCI-H1435, a non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell line, harbors heterozygous IGFBP5 mutation (E202*) (Figure 4F). Moreover, the CM from this cell line lacks a detectable signal from IGFBP5 (Supplementary Figure 5A), indicating the presence of additional misregulation of this protein. Indeed, the proliferation of NCI-H1435 cells was inhibited by various clinically relevant IGF-1R inhibitors, including BMS-536924 and BMS-75480734. Conversely, the growth of IGFBP5-wt NSCLC cell lines, including HCC15, A549, NCI-H1693 and HCC4017, was not affected by IGF-1R inhibitors (Figure 4G and Supplementary Figure 5D). Finally, all of these NSCLC cell lines were resistant to a multi-RTK inhibitor, Sunitinib, which, however, is inactive against IGF-1R36 (Figure 4G). The proliferation of an IGFBP5-mutated leukemia cell line, Molt-4 (K135fs*13), was also selectively inhibited by IGF-1R inhibitors (Supplementary Figure 5B). Importantly, the re-expression of IGFBP5 in Molt-4 cells leads to their decreased proliferation (Supplementary Figure 5C).

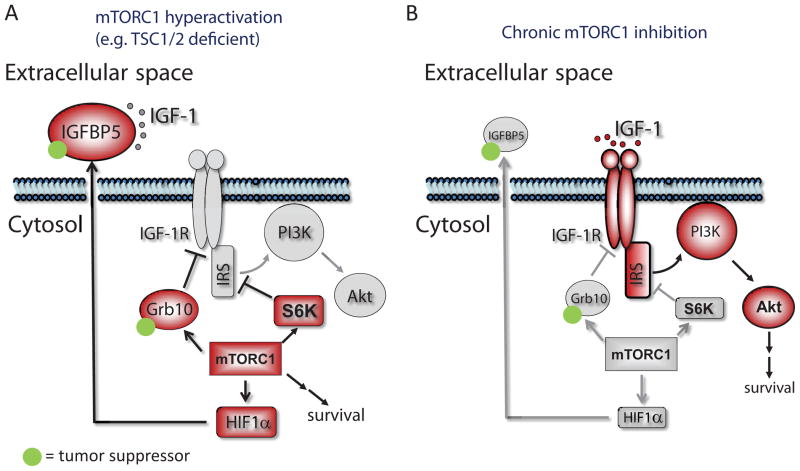

In summary, our results indicate that mTORC1 positively regulates the expression of IGFBP5 in a HIF1-dependent manner. Once secreted, IGFBP5 functions, in parallel to other intracellular branches of the feedback mechanisms, to block the function of IGF-1 (Figure 5). IGFBP5 is a potential tumor suppressor, and the proliferation of IGFBP5-mutated cells is sensitive to IGF-1R inhibitors. Finally, our results raise an intriguing hypothesis that IGFBP5 might serve as a “non-cell autonomous” feedback mechanism for tumors to restrain IGF-1R signaling in adjacent normal cells. In so doing, tumor cells might gain a competitive advantage in growth and proliferation. Whether this mechanism contributes to tumor progression warrants further investigation.

Figure 5.

mTORC1 orchestrates feedback inhibition of IGF-1 signaling by promoting HIF1α-dependent expression of IGFBP5. IGFBP5 accumulates in the extracellular space, and sequesters IGF-1 from binding to its cognate receptor (IGF-1R). mTORC1 also inhibits IGF-1 signaling by upregulating the expression of Grb10, and downregulating the expression of IRS and IGF-1R. Both Grb10 and IGFBP5 are potential tumor suppressors. Conversely, IGF-1R and PI3K is activated in mTORC1-suppressed conditions (e.g. rapamycin-treated), due to the relief of mTORC1-mediated feedback inhibition loops. Red and gray indiate proteins that are in the activated and repressed states, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. (A) LDH activity in the whole cell lysates and conditioned media from TSC2−/− MEFs was quantified using a coupled enzymatic colorimetric assay. LDH is a cytosolic enzyme that is found in nearly all living cells. (B) Chronic rapamcyin treatment (20 nM) of TSC2−/− MEFs led to Akt activation. For site-specific phosphorylation, pAkt(S473), pS6K(T389) and pS6(S235/236) levels were analyzed. (C) Heat-inactivated CM from TSC2−/− MEFs lost its ability to inhibit IGF-1 signaling. CM was collected from TSC2−/− MEFs and was heated at 95 ºC for 5 mins. CM was then mixed with IGF-1 (40 ng/ml) and added to wt MEFs, the WCL of which were analyzed. For site-specific phosphorylation, pIGF-1R(Y1135/1136) and pAkt(S473) levels were analyzed. (D) Proteins identified from the two SILAC experiments. (E) Identification of FGF21 as a downstream target of mTORC1 in the extracellular space. Extracted ion chromatogram is shown for the corresponding light (rapamycin-treated, blue) and heavy (control, yellow) ions of a peptide (ALKPGVIQILGVK) from FGF21. This peptide showed a dramatic decrease after rapamycin treatment. (F) Identification of an IGFBP5 peptide (HMEASLQEFK). The MS2 spectrum from which the peptide was identified (matched b- and y- ions are highlighted in blue and red, respectively) is shown. (G) Re-introducing TSC2 into TSC2−/− MEFs led to dramatic downregulation of IGFBP5 in CM. For site-specific phosphorylation, pAkt(S473) levels were analyzed. (H) Rapamycin treatment also downregulated the expression of IGFBP5 in RT-4 cells. RT-4 cells were starved for 24 hrs, during which cells were treated with 20 nM rapamycin. For site-specific phosphorylation, pS6K(T389) and pS6(S235/236) levels were analyzed. (I) Insulin stimulation of MCF7 cells resulted in the accumulation of IGFBP5 in CM, which was blocked by concurrent rapamycin treatment. Cells were starved for 12 hrs, and were then treated with insulin (100 nM) for 12 hrs, in the absence or presence of rapamycin (20 nM). For site-specific phosphorylation, pAkt(S473) and pS6(S235/236) levels were analyzed.

Supplementary Figure 2. Gene ontology analysis of the rapamycin-sensitive proteins (abundances decreased by at least 32-fold after rapamycin treatment). (A) Cellular compartment analysis. (B) Molecular function analysis. For clear presentation, only results from SILAC experiment #1 were considered.

Supplementary Figure 5. (A) CM from NCI-H1435 cells does not contain detectable IGFBP5 signals. CM from HEK293T cells that ectopically express IGFBP5 is used as the control. (B) Molt-4 cells (an acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell line that harbors a K135fs*13 mutation of the IGFBP5 gene) is more sensitive to IGF-1R inhibitors (BMS-536924 and BMS-754807), compared to Gefitinib and Sunitinib (48 hours treatment). P <0.001 (two-way ANOVA test). n=9 independent biological replicate experiments. Error bars represent s.d. (C) The expression of wt-IGFBP5 in Molt-4 cells (to a level similar to that in IGFBP5-wt cells, e.g. T47D and RT-4) leads to reduced proliferation of these cells (grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS). BMS-536924 treatment (500 nM) was used as the control. (D) The proliferation of IGFBP5-mutated (NCI-H1435), but not IGFBP5-wt (A549, NCI-H1693, HCC4017 and HCC15) NSCLC cells is sensitive to IGF-1R inhibitors (BMS-536924 and BMS-754807). None of these cells were sensitive to Sunitinib, a multi-RTK inhibitor, which, however, does not block IGF-1R.

Supplementary Figure 3. A schematic indicating the possible model of HIF1-regulated expression of IGFBP5. The design of various primers (P1–P4) capturing potential HIF1α binding sites on IGFBP5 is shown.

Supplementary Figure 4. (A) Proteins secreted from TSC2−/− MEFs inhibits the growth of MCF7 cells in a co-culture system. MCF7 cells were labeled with red florescent protein (DsRed), and were grown with GFP-labeled either TSC2+/+ or TSC2−/− MEFs. Cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with IGF-1. Scale bars, 40 μm. IGF-1 protects cells from staurosporine, (B), or etoposide (C)-induced apoptosis. This effect was abolished when IGFBP5 was co-added to the culture media. The asterisk indicates cleaved PARP1. For site-specific phosphorylation, pIGF-1R(Y1135/1136) and pAkt(S473) levels were analyzed. (D) IGFBP5 accounts for a major fraction of the IGF-1-inhibitory activity in CM from TSC2−/− MEFs. CM from TSC2+/+, shGFP TSC2−/− or shIGFBP5 TSC2−/− cells were mixed with IGF-1, and were added to recipient cells (wild type MEFs). WCL were analyzed by immunoblotting experiments using the indicated antibodies. The results were quantified using ImageJ. For site-specific phosphorylation, pIGF-1R(Y1135/1136) and pAkt(S473) levels were analyzed. *P < 0.05 (two-tailed Student t-test), NS=Not significant, n = 3 independent biological replicate experiments. Error bars represent s.d. (E) IGFBP5 mediates the mTORC1-dependent IGF-1-inhibitory activity in TSC2−/− MEFs. RNAi was used to knock down IGFBP5 in TSC2−/− MEFs. Where indicated, control knock down cells (shGFP TSC2−/− MEFs) were treated with rapamycin (20 nM for 24 hrs). The results were quantified using ImageJ. For site-specific phosphorylation, pIGF-1R(Y1135/1136), pAkt(S473) and pS6K(T389) levels were analyzed. pIGF-1R levels were normalized using total IGF-1R levels (note the rapamycin treatment increases total IGF1-R levels). **P < 0.01 (two-tailed Student t-test), NS=Not significant. n = 4 independent biological replicate experiments. Error bars represent s.d.

Supplementary Figure 6. Raw, uncropped images of the immunoblotting results.

Supplementary Table 1. Primer Sequences for qPCR

Supplementary Table 2. Primers for Luciferase Constructs

Supplementary Table 3. Primers for ChIP

Supplementary Table 4. The raw quantitative secretomic results for the experiment as described in Fig 1D. The data is uploaded in a separate excel file, with the heading annotation shown in the first tab of the excel file.

Supplementary Table 5. Representitive rapamycin-sensitive secreted proteins.

Supplementary Table 6. Rapamycin-sensitive secreted proteins sorted by relative abundances.

Supplementary Table 7. Rapamycin-sensitive secreted proteins sorted by gene symbols.

Supplementary Table 8. A list of the cancer-associated, somatic mutations of IGFBP5.

Supplementary Table 9. shRNA sequences.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Joseph Goldstein, Michael White, Melanie Cobb and Benjamin Tu for critically reviewing the manuscript. We thank Drs. John Minna and David Kwiatkowski for providing critical reagents, and Drs. Noelle Williams, Hangzhi Wang, Hong Chen and Leeju Wu for inputs and technical guidance. This work was supported in part by grants from the UT Southwestern Endowed Scholar Program (to Y. Y. and R.K.B.), the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT R1103 to Y.Y. and CPRIT RP130513 to R.K.B), the Welch Foundation (I-1800 to Y.Y and I-1568 to R.K.B.), National Institutes of Health (NIH) (GM114160 to Y.Y.), American Cancer Society (Research Scholar Grant, RSG-15-062-01-TBE and Institutional Research Grant, IRG-02-196-07, to Y. Y.), and a Career Award in the Biomedical Sciences from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (to R.K.B). Y. Y. is a Virginia Murchison Linthicum Scholar in Medical Research and a CPRIT Scholar in Cancer Research. R.K.B. is the Michael L. Rosenberg Scholar in Medical Research.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Y.Y. conceived the project. M. D., R. K. B. and Y.Y. designed the experiments. M. D. and Y.Y. performed the experiments. R. K. B. provided inputs on HIF1-related experiments. Y. Y. wrote the manuscript with inputs from all co-authors.

The proteomic data can be downloaded from the Chorus database using the following link: https://chorusproject.org/anonymous/download/experiment/4a5364d20d784bad95d69862e4ba23fa and https://chorusproject.org/anonymous/download/experiment/52afeb2040a5472ea543531f751d9fa4

References

- 1.Dibble CC, Manning BD. Signal integration by mTORC1 coordinates nutrient input with biosynthetic output. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:555–564. doi: 10.1038/ncb2763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wouters BG, Koritzinsky M. Hypoxia signalling through mTOR and the unfolded protein response in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:851–864. doi: 10.1038/nrc2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sancak Y, et al. The Rag GTPases bind raptor and mediate amino acid signaling to mTORC1. Science. 2008;320:1496–1501. doi: 10.1126/science.1157535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma XM, Blenis J. Molecular mechanisms of mTOR-mediated translational control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:307–318. doi: 10.1038/nrm2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsu PP, et al. The mTOR-Regulated Phosphoproteome Reveals a Mechanism of mTORC1-Mediated Inhibition of Growth Factor Signaling. Science. 2011;332:1317–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.1199498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robitaille AM, et al. Quantitative phosphoproteomics reveal mTORC1 activates de novo pyrimidine synthesis. Science. 2013;339:1320–1323. doi: 10.1126/science.1228771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu Y, et al. Phosphoproteomic analysis identifies Grb10 as an mTORC1 substrate that negatively regulates insulin signaling. Science. 2011;332:1322–1326. doi: 10.1126/science.1199484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimobayashi M, Hall MN. Making new contacts: the mTOR network in metabolism and signalling crosstalk. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:155–162. doi: 10.1038/nrm3757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagle N, et al. Activating mTOR mutations in a patient with an extraordinary response on a phase I trial of everolimus and pazopanib. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:546–553. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bissler JJ, et al. Sirolimus for angiomyolipoma in tuberous sclerosis complex or lymphangioleiomyomatosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:140–151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagle N, et al. Response and acquired resistance to everolimus in anaplastic thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1426–1433. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cloughesy TF, et al. Antitumor activity of rapamycin in a Phase I trial for patients with recurrent PTEN-deficient glioblastoma. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandarlapaty S, et al. AKT inhibition relieves feedback suppression of receptor tyrosine kinase expression and activity. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:58–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang H, et al. PDGFRs are critical for PI3K/Akt activation and negatively regulated by mTOR. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:730–738. doi: 10.1172/JCI28984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrington LS, et al. The TSC1-2 tumor suppressor controls insulin-PI3K signaling via regulation of IRS proteins. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:213–223. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah OJ, Hunter T. Turnover of the active fraction of IRS1 involves raptor-mTOR- and S6K1-dependent serine phosphorylation in cell culture models of tuberous sclerosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6425–6434. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01254-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu P, et al. Sin1 phosphorylation impairs mTORC2 complex integrity and inhibits downstream Akt signalling to suppress tumorigenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:1340–1350. doi: 10.1038/ncb2860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang G, Murashige DS, Humphrey SJ, James DE. A Positive Feedback Loop between Akt and mTORC2 via SIN1 Phosphorylation. Cell Rep. 2015;12:937–943. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhaskar PT, et al. mTORC1 hyperactivity inhibits serum deprivation-induced apoptosis via increased hexokinase II and GLUT1 expression, sustained Mcl-1 expression, and glycogen synthase kinase 3beta inhibition. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:5136–5147. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01946-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makridakis M, Vlahou A. Secretome proteomics for discovery of cancer biomarkers. J Proteomics. 2010;73:2291–2305. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Wang J, Ding M, Yu Y. Site-specific characterization of the Asp- and Glu-ADP-ribosylated proteome. Nat Methods. 2013;10:981–984. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cornu M, et al. Hepatic mTORC1 controls locomotor activity, body temperature, and lipid metabolism through FGF21. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:11592–11599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412047111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hwa V, Oh Y, Rosenfeld RG. The insulin-like growth factor-binding protein (IGFBP) superfamily. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:761–787. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.6.0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cybulski N, Polak P, Auwerx J, Ruegg MA, Hall MN. mTOR complex 2 in adipose tissue negatively controls whole-body growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9902–9907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811321106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pearce LR, et al. Characterization of PF-4708671, a novel and highly specific inhibitor of p70 ribosomal S6 kinase (S6K1) Biochem J. 2010;431:245–255. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duvel K, et al. Activation of a metabolic gene regulatory network downstream of mTOR complex 1. Mol Cell. 2010;39:171–183. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li S, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Bifurcation of insulin signaling pathway in rat liver: mTORC1 required for stimulation of lipogenesis, but not inhibition of gluconeogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3441–3446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914798107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Owen JL, et al. Insulin stimulation of SREBP-1c processing in transgenic rat hepatocytes requires p70 S6-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:16184–16189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213343109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Semenza GL. Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:721–732. doi: 10.1038/nrc1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Semenza GL, et al. Hypoxia response elements in the aldolase A, enolase 1, and lactate dehydrogenase A gene promoters contain essential binding sites for hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32529–32537. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salih DA, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 5 (Igfbp5) compromises survival, growth, muscle development, and fertility in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4314–4319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400230101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miyake H, Pollak M, Gleave ME. Castration-induced up-regulation of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-5 potentiates insulin-like growth factor-I activity and accelerates progression to androgen independence in prostate cancer models. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3058–3064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carboni JM, et al. BMS-754807, a small molecule inhibitor of insulin-like growth factor-1R/IR. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:3341–3349. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen HX, Sharon E. IGF-1R as an anti-cancer target-trials and tribulations. Chinese Journal of Cancer. 2013;32:242–252. doi: 10.5732/cjc.012.10263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mendel DB, et al. In vivo antitumor activity of SU11248, a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor receptors: determination of a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationship. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:327–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. (A) LDH activity in the whole cell lysates and conditioned media from TSC2−/− MEFs was quantified using a coupled enzymatic colorimetric assay. LDH is a cytosolic enzyme that is found in nearly all living cells. (B) Chronic rapamcyin treatment (20 nM) of TSC2−/− MEFs led to Akt activation. For site-specific phosphorylation, pAkt(S473), pS6K(T389) and pS6(S235/236) levels were analyzed. (C) Heat-inactivated CM from TSC2−/− MEFs lost its ability to inhibit IGF-1 signaling. CM was collected from TSC2−/− MEFs and was heated at 95 ºC for 5 mins. CM was then mixed with IGF-1 (40 ng/ml) and added to wt MEFs, the WCL of which were analyzed. For site-specific phosphorylation, pIGF-1R(Y1135/1136) and pAkt(S473) levels were analyzed. (D) Proteins identified from the two SILAC experiments. (E) Identification of FGF21 as a downstream target of mTORC1 in the extracellular space. Extracted ion chromatogram is shown for the corresponding light (rapamycin-treated, blue) and heavy (control, yellow) ions of a peptide (ALKPGVIQILGVK) from FGF21. This peptide showed a dramatic decrease after rapamycin treatment. (F) Identification of an IGFBP5 peptide (HMEASLQEFK). The MS2 spectrum from which the peptide was identified (matched b- and y- ions are highlighted in blue and red, respectively) is shown. (G) Re-introducing TSC2 into TSC2−/− MEFs led to dramatic downregulation of IGFBP5 in CM. For site-specific phosphorylation, pAkt(S473) levels were analyzed. (H) Rapamycin treatment also downregulated the expression of IGFBP5 in RT-4 cells. RT-4 cells were starved for 24 hrs, during which cells were treated with 20 nM rapamycin. For site-specific phosphorylation, pS6K(T389) and pS6(S235/236) levels were analyzed. (I) Insulin stimulation of MCF7 cells resulted in the accumulation of IGFBP5 in CM, which was blocked by concurrent rapamycin treatment. Cells were starved for 12 hrs, and were then treated with insulin (100 nM) for 12 hrs, in the absence or presence of rapamycin (20 nM). For site-specific phosphorylation, pAkt(S473) and pS6(S235/236) levels were analyzed.

Supplementary Figure 2. Gene ontology analysis of the rapamycin-sensitive proteins (abundances decreased by at least 32-fold after rapamycin treatment). (A) Cellular compartment analysis. (B) Molecular function analysis. For clear presentation, only results from SILAC experiment #1 were considered.

Supplementary Figure 5. (A) CM from NCI-H1435 cells does not contain detectable IGFBP5 signals. CM from HEK293T cells that ectopically express IGFBP5 is used as the control. (B) Molt-4 cells (an acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell line that harbors a K135fs*13 mutation of the IGFBP5 gene) is more sensitive to IGF-1R inhibitors (BMS-536924 and BMS-754807), compared to Gefitinib and Sunitinib (48 hours treatment). P <0.001 (two-way ANOVA test). n=9 independent biological replicate experiments. Error bars represent s.d. (C) The expression of wt-IGFBP5 in Molt-4 cells (to a level similar to that in IGFBP5-wt cells, e.g. T47D and RT-4) leads to reduced proliferation of these cells (grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS). BMS-536924 treatment (500 nM) was used as the control. (D) The proliferation of IGFBP5-mutated (NCI-H1435), but not IGFBP5-wt (A549, NCI-H1693, HCC4017 and HCC15) NSCLC cells is sensitive to IGF-1R inhibitors (BMS-536924 and BMS-754807). None of these cells were sensitive to Sunitinib, a multi-RTK inhibitor, which, however, does not block IGF-1R.

Supplementary Figure 3. A schematic indicating the possible model of HIF1-regulated expression of IGFBP5. The design of various primers (P1–P4) capturing potential HIF1α binding sites on IGFBP5 is shown.

Supplementary Figure 4. (A) Proteins secreted from TSC2−/− MEFs inhibits the growth of MCF7 cells in a co-culture system. MCF7 cells were labeled with red florescent protein (DsRed), and were grown with GFP-labeled either TSC2+/+ or TSC2−/− MEFs. Cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with IGF-1. Scale bars, 40 μm. IGF-1 protects cells from staurosporine, (B), or etoposide (C)-induced apoptosis. This effect was abolished when IGFBP5 was co-added to the culture media. The asterisk indicates cleaved PARP1. For site-specific phosphorylation, pIGF-1R(Y1135/1136) and pAkt(S473) levels were analyzed. (D) IGFBP5 accounts for a major fraction of the IGF-1-inhibitory activity in CM from TSC2−/− MEFs. CM from TSC2+/+, shGFP TSC2−/− or shIGFBP5 TSC2−/− cells were mixed with IGF-1, and were added to recipient cells (wild type MEFs). WCL were analyzed by immunoblotting experiments using the indicated antibodies. The results were quantified using ImageJ. For site-specific phosphorylation, pIGF-1R(Y1135/1136) and pAkt(S473) levels were analyzed. *P < 0.05 (two-tailed Student t-test), NS=Not significant, n = 3 independent biological replicate experiments. Error bars represent s.d. (E) IGFBP5 mediates the mTORC1-dependent IGF-1-inhibitory activity in TSC2−/− MEFs. RNAi was used to knock down IGFBP5 in TSC2−/− MEFs. Where indicated, control knock down cells (shGFP TSC2−/− MEFs) were treated with rapamycin (20 nM for 24 hrs). The results were quantified using ImageJ. For site-specific phosphorylation, pIGF-1R(Y1135/1136), pAkt(S473) and pS6K(T389) levels were analyzed. pIGF-1R levels were normalized using total IGF-1R levels (note the rapamycin treatment increases total IGF1-R levels). **P < 0.01 (two-tailed Student t-test), NS=Not significant. n = 4 independent biological replicate experiments. Error bars represent s.d.

Supplementary Figure 6. Raw, uncropped images of the immunoblotting results.

Supplementary Table 1. Primer Sequences for qPCR

Supplementary Table 2. Primers for Luciferase Constructs

Supplementary Table 3. Primers for ChIP

Supplementary Table 4. The raw quantitative secretomic results for the experiment as described in Fig 1D. The data is uploaded in a separate excel file, with the heading annotation shown in the first tab of the excel file.

Supplementary Table 5. Representitive rapamycin-sensitive secreted proteins.

Supplementary Table 6. Rapamycin-sensitive secreted proteins sorted by relative abundances.

Supplementary Table 7. Rapamycin-sensitive secreted proteins sorted by gene symbols.

Supplementary Table 8. A list of the cancer-associated, somatic mutations of IGFBP5.

Supplementary Table 9. shRNA sequences.