Abstract

Thrombogenic and inflammatory mediators, such as thrombin, induce NF-κB–mediated endothelial cell (EC) activation and dysfunction, which contribute to pathogenesis of arterial thrombosis. The role of anti-inflammatory microRNA-181b (miR-181b) on thrombosis remains unknown. Our previous study demonstrated that miR-181b inhibits downstream NF-κB signaling in response to TNF-α. Here, we demonstrate that miR-181b uniquely inhibits upstream NF-κB signaling in response to thrombin. Overexpression of miR-181b inhibited thrombin-induced activation of NF-κB signaling, demonstrated by reduction of phospho-IKK-β, -IκB-α, and p65 nuclear translocation in ECs. MiR-181b also reduced expression of NF-κB target genes VCAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1, E-selectin, and tissue factor. Mechanistically, miR-181b targets caspase recruitment domain family member 10 (Card10), an adaptor protein that participates in activation of the IKK complex in response to signals transduced from protease-activated receptor-1. miR-181b reduced expression of Card10 mRNA and protein, but not protease-activated receptor-1. 3′-Untranslated region reporter assays, argonaute-2 microribonucleoprotein immunoprecipitation studies, and Card10 rescue studies revealed that Card10 is a bona fide direct miR-181b target. Small interfering RNA–mediated knockdown of Card10 expression phenocopied effects of miR-181b on NF-κB signaling and targets. Card10 deficiency did not affect TNF-α–induced activation of NF-κB signaling, which suggested stimulus-specific regulation of NF-κB signaling and endothelial responses by miR-181b in ECs. Finally, in response to photochemical injury-induced arterial thrombosis, systemic delivery of miR-181b reduced thrombus formation by 73% in carotid arteries and prolonged time to occlusion by 1.6-fold, effects recapitulated by Card10 small interfering RNA. These data demonstrate that miR-181b and Card10 are important regulators of thrombin-induced EC activation and arterial thrombosis. These studies highlight the relevance of microRNA-dependent targets in response to ligand-specific signaling in ECs.—Lin, J., He, S., Sun, X., Franck, G., Deng, Y., Yang, D., Haemmig, S., Wara, A. K. M., Icli, B., Li, D., Feinberg, M. W. MicroRNA-181b inhibits thrombin-mediated endothelial activation and arterial thrombosis by targeting caspase recruitment domain family member 10.

Keywords: endothelial cells, NF-κB, Card10

Arterial thrombosis is a central pathologic mechanism that leads to extensive morbidity and mortality in patients with coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, or stroke (1). A number of cardiovascular risk factors, such as smoking, hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes mellitus, often cause endothelial dysfunction to generate a proinflammatory and procoagulant milieu, which is crucial for development of thrombosis (2–4). Conversely, thrombosis in arteries exacerbates endothelial dysfunction, for example, via inducing generation of thrombin (5). Thus, coagulation and inflammatory signaling pathways are 2 interdependent pathways that form a vicious cycle that propagates thrombosis (6).

Vascular endothelium is a key regulator of arterial thrombosis (7). Under physiologic conditions, endothelium displays anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic properties, such as attenuating leukocyte adhesion (8) and inhibiting coagulation (9); however, alteration of normal endothelial function results in increased leukocyte adhesion/migration, increased permeability, and activation of coagulation under pathologic states (10). Thrombin is a multifunctional serine protease that can generate procoagulant responses to amplify inflammation (11). After binding to its cell-surface receptors—protease-activated receptors (PARs)—thrombin activates NF-κB signaling in endothelial cells (ECs) (12–14) and induces expression of many genes with proadhesive and procoagulant properties, including VCAM-1 (15), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) (15), and tissue factor (TF) (16). Adaptor proteins, such as caspase recruitment domain family member 10 (Card10), serve as a molecular bridge that links signaling from PARs with NF-κB activation, specifically, activation of the IKK complex (8, 17–19). Thus, targeting adaptor proteins, such as Card10, holds promise for an alternative approach to attenuate thrombin-induced NF-κB activation and arterial thrombosis.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are single-stranded, noncoding small RNAs of ∼22 nucleotides that regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level by promoting mRNA degradation or inhibiting translation. We have previously uncovered an important role of microRNA-181b (miR-181b) in regulation of both acute and chronic vascular inflammation (20, 21) by reducing downstream NF-κB signaling. miR-181b has no effect on upstream NF-κB signaling, such as IKK-β and IκBα phosphorylation in response to TNF-α in ECs. The role of miR-181b in thrombin-induced NF-κB activation and regulation of arterial thrombosis remain unknown. In the present study, we investigated the role of miR-181b in blocking thrombin-induced activation of upstream NF-κB signaling and development of arterial thrombosis. Our findings demonstrate that miR-181b is an important regulator of thrombin-induced EC activation and arterial thrombosis by directly targeting Card10, thus providing the rationale for potential use of miR-181b mimetics to attenuate arterial thrombosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

PremiR miRNA Precursor Molecules Negative Control#1 (AM17110), PremiR miRNA Precursor Molecules miR-181b (PM12442), anti-miR miRNA Inhibitors Negative Control#1 (AM17010), and miR-181b inhibitor (AM12442) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific Life Sciences (Waltham, MA, USA). Human α-thrombin (HT 1002a) was from Enzyme Research Laboratories (South Bend, IN, USA). Recombinant human TNF-α was purchased from R&D Systems (210-TA/CF; Minneapolis, MN, USA). Lipofectamine 2000 and Trizol reagents were from Thermo Fisher Scientific Life Sciences. Protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (#11836153001) were from Roche (Basel, Switzerland). Phosphatase inhibitor (#102146) was from Active Motif (Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Antibodies against p65 (sc-372), VCAM-1 (sc-13160), Ku-70 (sc-17789), usf-2 (sc-862), and p50 (sc-7178) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA). Antibodies against phospho-IKKβ (#2694), IKKβ (#2370), phospho-IKKγ (#2689), IκBα (#4812), β-actin (#4970), and phospho-IκBα (#2859) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Antibodies against ICAM-1 (BBA3), E-selectin (BBA16), and IKKγ (AF2684) were purchased from R&D Systems. Antibodies against Card10 (ab36839 and ab137383) were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA).

Cell culture and transfection

HUVECs (cc-2159) were obtained from Lonza (Basel, Switzerland) and cultured in EC growth medium EGM-2(cc-3162). Cells used for all experiments were subcultured <5 times. HUVECs (70,000/well) were plated on 12-well plates, transfected with 10 nM microRNA mimics, 50 nM microRNA inhibitors, or 30 nM small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) when cells reached 70–80% confluency. Lipofectamine 2000 was used following manufacturer instructions. Cells were allowed to grow for 36 h before treatment with 5 U/ml thrombin or 10 ng/ml TNF-α for various time points. For rescue experiments, cells were transfected in triplicates with 400 ng empty vector or pCMV-CARD10 plasmid (22) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Life Sciences) for 3 h followed by transfection with 10 nM miRNA nonspecific negative control mimic (NS-m) or miR-181b (181b-m) for 20 h. Cells were stimulated with thrombin (5 U/ml) and harvested for quantitative PCR and Western blot analysis at indicated time points on the next day.

Real-time quantitative PCR

HUVECs were lysed with Trizol reagent and total RNA was isolated according to manufacturer instructions. QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (#205310) from Qiagen (Valencia, CA, USA) was used to generate cDNAs. GoTaq qPCR Master Mix (A6001) from Promega (Madison, WI, USA) was used for real-time quantitative PCR with Mx3000BP Real-time PCR system (Stratagene, San Diego, CA, USA) following manufacturer instructions. Primers for human VCAM-1, ICAM-1, E-selectin, and others are described previously (21).

Western blot analysis

HUVECs were scraped and lysed in RIPA buffer that was supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail tablets and phosphatase inhibitor. Cell lysates were collected after spin at 12,000 rpm for 10 min. For nuclear translocation analysis, NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagent (#78833) from Thermo Fisher Scientific Life Sciences was used to separate nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions. Protein concentrations were measured by using Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (#23225). SDS-PAGE 8 or 10% gels were used to separate lysates; proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and then incubated with corresponding antibodies (VCAM-1, 1:1000; ICAM-1, 1:3000; E-selectin, 1:1000; Card10, 1:800). ECL Plus Western blotting detection reagents (RPN2132; GE Healthcare, Pittsburg, PA, USA) were used to visualize proteins. ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used to analyze abundance of proteins.

Tail-vein injection of lipofectamine-encapsulated miRNA or siRNA into mice

Mice were injected with microRNA mimics or siRNAs 3 times by tail vein injection on 3 consecutive days as previously described (20).

Microribonucleoprotein immunoprecipitation

Microribonucleoprotein immunoprecipitation was performed as described in our previous study (21).

Immunostaining and image analysis

Frozen sections of mouse carotid arteries were incubated with 80% acetone for 2 min followed by 1 mg/ml sodium borohdyride (ICN Chemicals, Irvine, CA, USA) for 5 min at room temperature after 3 washes in Tris-buffered saline (TBS). Sections were washed 3 times in TBS before being incubated in 5% normal donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. Slides were incubated with rat anti-CD31 (1:100; BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, USA) and rabbit anti-Card10 (1:100; Abcam) overnight at 4°C. Slides were washed 3 times with TBS before incubating with Alexa Flour 594–conjugated donkey anti-rat and Alexa Flour 647–conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch). Slides were washed 3 times with TBS and mounted with Prolong Gold anti-fade mounting medium that contained DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific Life Sciences). Images were acquired on an upright Carl Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Fluorescence intensity of Card10 was measured by using ImageJ. Data were calculated from at least 36 cells for each group. For each mouse, 7–14 cells randomly selected from sections were used for quantification.

Constructs and luciferase reporter assays

Constructs pcDNA3.1 vector, pcDNA3.1–miR-181b, and pcDNA3.1–miR-181b-mut are the same as previously described (21). The 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of gene of Card10 was amplified and cloned into the pMIR-Report Luciferase vector between SacI and MluI restriction sites. HUVECs were transfected with 0.3 μg Card10–3′-UTR construct and 0.5 μg pcDNA3.1, pcDNA3.1–miR-181b, or pcDNA3.1–miR-181b-mut. Transfected cells were collected in 200 μl reporter lysis buffer (#E397A) from Promega. After a freeze-thaw cycle, cells were then vortexed and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min to discard cell debris. Luciferase activities were measured with microplate luminometer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Reading of luciferase activity was normalized to protein concentration for each sample accordingly.

Lentivirus production and transduction

Card10 gene was amplified from pCMV-CARD10 plasmid [kind gift from B. Medoff (22)] by using the primers below and cloned into LV-Cre-pLKO.1 (Addgene plasmid #25997) to replace Cre gene between XhaI and KpnI sites. Forward primer: 5′-AATTCTAGAATGTTGGGTGGCCCGGGAGGC-3′; reverse primer: 5′-TTAGGTACCTCAGGCCTCACTACTGCTGCC-3′.

Lentivirus for control pLKO.1 puro (Addgene plasmid #8453) or pLKO.1-CARD10 was generated by cotransfection of 293T cells (ATCC CRL-3216) using pMD2.G (Addgene plasmid #12259) and psPAX2 (Addgene plasmid #12260) in a 3:2:1 ratio, respectively. Plasmids were added to 0.1× TE (T9285; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), followed by 2.5M CaCl2 (C1016; Sigma-Aldrich) and 2× HEPES buffered saline (23). Transfection mix was added dropwise to dish and medium was changed ∼16 h later. Supernatant was collected 2 d later by filtering through 0.45 µm filter and stored at −80°C. Transduction of HUVECs was carried out in 6-well plate adding 1 ml lentiviral supernatant to 1 ml medium in combination with 8 µg/ml polybrene (AB01643; American Bio, Natick, MA, USA). Medium was changed 16 h later.

Carotid artery thrombosis model

Mice were injected with miRNA mimics (NS-m, 181b-m) or siRNAs (control siRNAs, Card10 siRNAs) 3 times by tail vein injection on 3 consecutive days. Thrombosis was induced in carotid arteries by photochemical injury as previously described (24, 25). In brief, mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg) from Patterson Veterinary (Devens, MA, USA). Rose-Bengal (#330000; Sigma-Aldrich) was diluted in saline and then injected into tail vein at a final concentration of 75 mg/kg. The right common carotid artery was exposed, and Doppler flow probe (MA0.5PSB; Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY, USA) was placed under the vessel. Probe was connected to a flowmeter (Model TS420; Transonic Systems) and data were collected and analyzed with a computerized data acquisition program (Windaq; DataQ Instruments, Akron, OH, USA). Photochemical injury was induced by a green light source (FC-3 LED light equipped with POF Fiber Core: 1500 μm, NA 0.5, 535 nm; Prizmatix, Givat-Shmuel, Israel) immediately after Rose-Bengal injection. Blood flow was monitored from time of injection of Rose-Bengal. Occlusion time was determined after vessel remained closed with cessation of blood flow for >10 min. For histologic analyses of carotid artery thrombosis, mice were harvested at 20 min after photochemical injury and examined by hematoxylin and eosin staining.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as means ± sem or as otherwise indicated. We used paired or unpaired Student’s t tests as appropriate for statistical comparison between 2 groups and ANOVA for comparison of ≥3 groups. Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

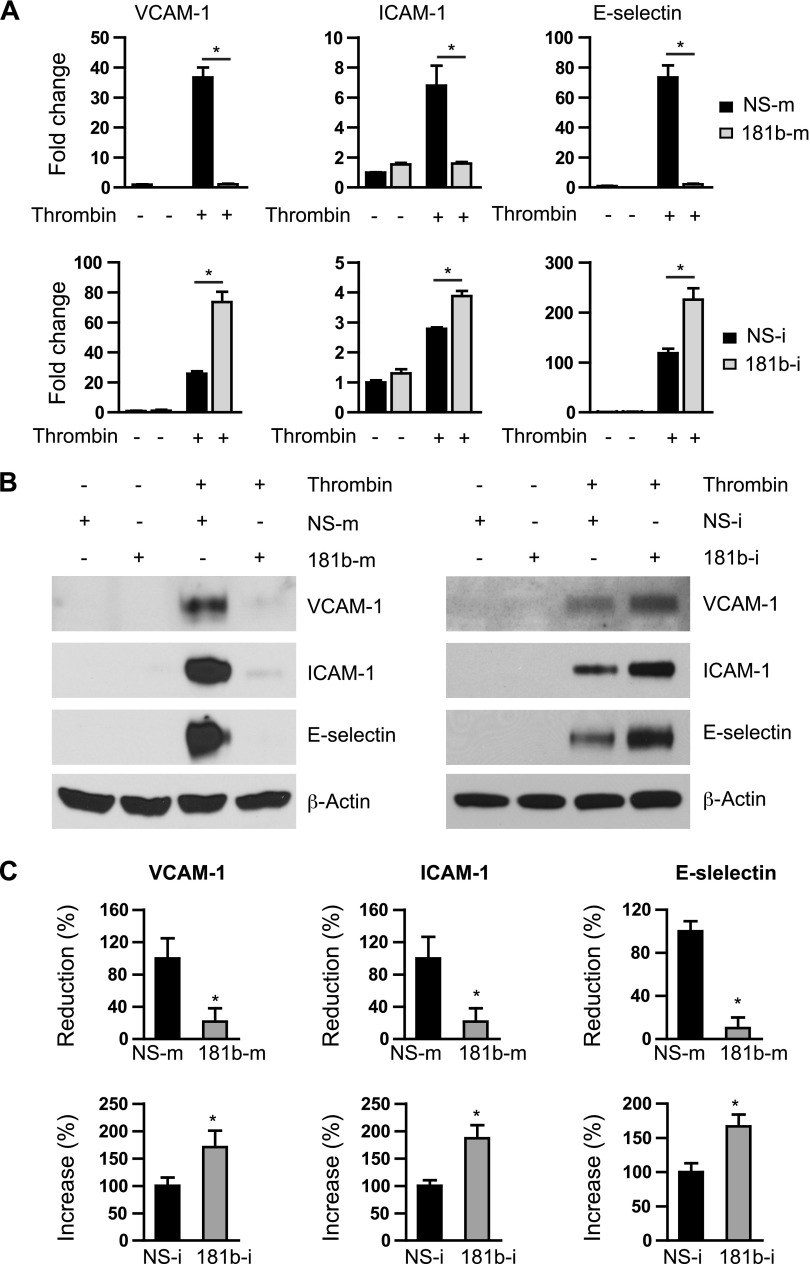

miR-181b reduces thrombin-induced adhesion molecule expression in ECs

Our previous findings demonstrated that miR-181b can inhibit vascular inflammation both in acute inflammatory diseases, such as sepsis, and in chronic inflammatory diseases, such as atherosclerosis (20, 21). EC activation and vascular inflammation play a pivotal role in pathogenesis of thrombosis (6, 9, 10, 14). Hence, we examined effects of miR-181b on thrombin-induced expression of key adhesion molecules in ECs by using gain- and loss-of-function experiments. Overexpression of miR-181b potently inhibited thrombin-induced VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin mRNA expression by 97 ± 9, 71 ± 2, and 92 ± 3%, respectively (Fig. 1A, top), whereas miR-181b inhibitors (complementary antagonist) increased expression by 223 ± 8, 44 ± 4, and 89 ± 7%, respectively (Fig. 1A, bottom). In agreement with results at the mRNA level, protein levels of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin were dramatically reduced by 79 ± 19, 92 ± 5, and 98 ± 15%, respectively, in cells that overexpressed miR-181b compared with cells that overexpressed miRNA negative control (NS-m; Fig. 1B, C). In contrast, miR-181b inhibition potentiated the mRNA and protein expression of these adhesion molecules by 73 ± 14, 65 ± 10, and 83 ± 12%, respectively (Fig. 1B, C). To examine functional effects of miR-181b on expression of these adhesion molecules, cell adhesion assays were performed. As shown in Supplemental Fig. 1, the number of leukocytes adhering to thrombin-activated EC monolayer was significantly reduced by miR-181b. Collectively, these data demonstrate that miR-181b is able to inhibit thrombin-induced expression of NF-κB target genes, such as adhesion molecules, in ECs.

Figure 1.

miR-181b reduces thrombin-induced expression of adhesion molecules in ECs. A) HUVECs were transfected with 10 nM miRNA negative control (NS-m), or miR-181b mimics (181b-m); 50 nM miRNA inhibitor negative control (NS-i), or miR-181b inhibitor (181b-i) for 24 h. Cells were treated with thrombin (5 U/ml) or PBS for 4 h and harvested for quantitative PCR analysis; n = 3 per group. B) HUVECs were transfected with NS-m (10 nM), 181b-m (10 nM), NS-i (50 nM), or 181b-i (50 nM) for 24 h, treated with thrombin (5 U/ml) or PBS for 8 h, and harvested for Western blot analysis. C) Quantification of results from panel B; n = 3 independent experiments. Data are given as means ± sem. *P < 0.05.

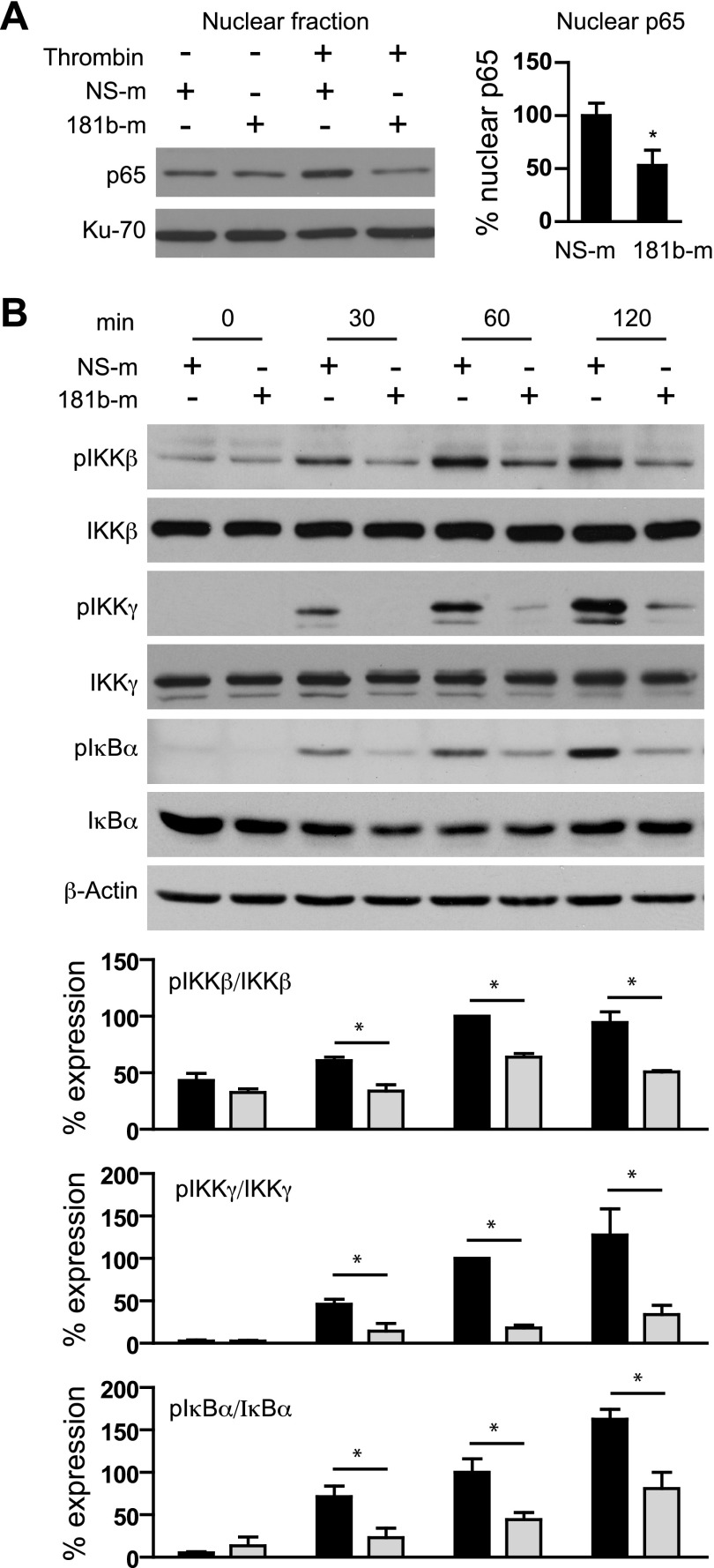

miR-181b inhibits thrombin-induced upstream NF-κB signaling in ECs

We previously demonstrated that in TNF-α–treated ECs, miR-181b inhibits NF-κB downstream signaling by directly repressing importin-α3 expression and, consequently, NF-κB nuclear translocation. We therefore explored the effect of miR-181b on NF-κB nuclear accumulation in ECs treated with thrombin. Consistent with our previous results, miR-181b overexpression decreased nuclear p65 expression by 74 ± 5% in the presence of thrombin (Fig. 2A). Because thrombin stimulation of ECs has been shown to activate NF-κB signaling by converging on the upstream IKK complex, we next investigated whether miR-181b could inhibit thrombin-induced activation of upstream NF-κB signaling. Of interest, overexpression of miR-181b inhibited phospho-IκBα and phospho-IKKβ after 1 h of thrombin stimulation in ECs by 47 and 36%, respectively (Fig. 2B). Moreover, we found that overexpression of miR-181b inhibited thrombin-induced phospho-IKKγ in ECs by 82%. Furthermore, miR-181b had no effects on expression of total IκBα, IKKβ, and IKKγ (Fig. 2B). PARs (PAR1–4) are a small family of GPCRs, which can be activated by coagulation proteases (12, 26). Among them, PAR1 and PAR3 are the primary PARs in ECs activated by thrombin (12). miR-181b did not regulate expression of these PARs as demonstrated in Supplemental Fig. 2. These data suggest that miR-181b inhibits thrombin-induced upstream NF-κB signaling in ECs, likely by targeting a protein that mediates signal transduction from cell surface to IKK complex.

Figure 2.

miR-181b inhibits thrombin-induced upstream NF-κB signaling in ECs. HUVECs were transfected with 10 nM NS-m or 181b-m. A) Cells were treated with thrombin (5 U/ml) for 1.5 h, and p65 expression was examined in the nuclear fraction by Western blot analysis; n = 3 independent experiments. B) Cells were treated with thrombin (5 U/ml) for 0, 30, 60, and 120 min and harvested for Western blot analysis of phospho-IKK-β, -IKK-γ, and -IκB-α expression. Ratios of phosphorylated protein to total protein were quantified; n = 3 independent experiments. Values are given as means ± sem. *P < 0.05.

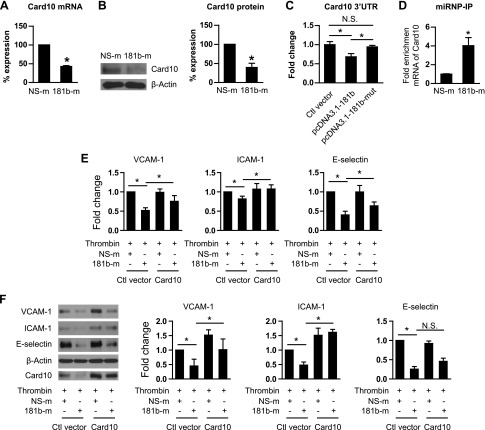

miR-181b directly targets Card10 and reduces its expression

We hypothesized that miR-181b can directly target a molecule that activates the IKK complex in response to thrombin stimulation in ECs. Previous studies show that Card10 is an adaptor protein that participates in the activation of the IKK complex downstream of signals transduced from GPCRs by forming a Card10–BCL10–MALT1 complex (8, 17). miR-181b reduced expression of Card10 by 57% at the mRNA level (Fig. 3A) and by 29% at the protein level (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, by using luciferase reporter assays, miR-181b reduced Card10 3′−UTR activity by 32%, whereas mutation of miR-181b seed sequence abrogated the reduction (Fig. 3C). Indeed, microribonucleoprotein immunoprecipitation studies revealed a 4-fold enrichment of Card10 mRNA in the RNA-induced silencing complex in presence of miR-181b compared with NS-m controls (Fig. 3D). In contrast, miR-181b did not affect expression of other adaptor proteins, including TRAF6, BCL10, and MALT1 (Supplemental Fig. 2). To examine whether reduction of Card10 in presence of miR-181b overexpression mediates effects of miR-181b on NF-κB signaling and targets in response to thrombin, we performed Card10 rescue studies. Indeed, overexpression of Card10 blocked miR-181b–mediated reduction of NF-κB target genes, including VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin, on mRNA and protein expression levels (Fig. 3E, F, Supplemental Fig. 3). In summary, our data indicate that Card10 is a bona fide miR-181b direct target, and its reduction by miR-181b, at least in part, contributes to inhibitory effects of miR-181b on thrombin-induced NF-κB signaling and EC activation.

Figure 3.

miR-181b directly targets Card10 and reduces its expression. A) Quantitative PCR analysis of Card10 expression in NS-m and 181b-m transfected HUVECs; n = 3 independent experiments. B) Western blot analysis of Card10 expression in NS-m and 181b-m transfected HUVECs and quantification of Card10 expression normalized by β-actin; n = 3 independent experiments. C) Luciferase reporter assays of Card10 3′-UTR in HUVECs; n = 3 independent experiments. D) Microribonucleoprotein immunoprecipitation analysis showed enrichment of Card10 mRNA in HUVECs transfected with NS-m or 181b-m; n = 3 per group. E, F) Quantitative PCR (E) and Western blot (F) analysis of NF-κB target genes in HUVECs transfected with pCMV-Card10 or control vector. Card10 overexpresssion blocked reduction of NF-κB target genes by miR-181b; n = 3 independent experiments. Ctl, control; N.S., not significant. Data are given as means ± sd. *P < 0.05.

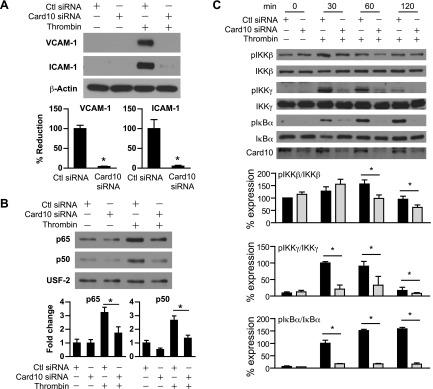

Card10 knockdown reduces thrombin-induced gene expression and NF-κB signaling in ECs

We hypothesized Card10 knockdown may phenocopy the effect of miR-181b on thrombin-induced signaling events. To test this, we examined thrombin-induced NF-κB signaling and target gene expression in ECs with Card10 knockdown. As shown in Fig. 4A, Card10 knockdown inhibited thrombin-induced expression of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 by 96 and 95%, respectively, and reduced thrombin-induced p65 and p50 nuclear translocation by 47 and 50%, respectively (Fig. 4B). In addition, Card10 knockdown reduced IKK complex activation as demonstrated by 37, 78, and 89% reduction of phospho-IKKβ, -IKKγ, and -IκBα, respectively, without affecting expression of total IκBα, IKKβ, and IKKγ (Fig. 4C). Collectively, these data indicate that knockdown of Card10 reduced thrombin-induced NF-κB upstream signaling and NF-κB target gene expression.

Figure 4.

Card10 knockdown reduces thrombin-induced gene expression and NF-κB signaling in ECs. HUVECs were transfected with 30 nM control siRNA or Card10 siRNA. A) Cells were treated with thrombin (5 U/ml) for 8 h and harvested for Western blot analysis of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1. B) Expression of p65 and p50 in the nuclear fraction of HUVECs treated with thrombin (5 U/ml, 1.5 h) was examined by Western blot analysis; quantifications were normalized by USF-2; n = 3 independent experiments. C) Cells were treated with thrombin (5 U/ml) for 0, 30, 60, and 120 min and harvested for Western blot analysis of phospho-IKK-β, -IKK-γ, and -IκB-α expression. Ratios of phosphorylated protein to total protein were calculated. Ctl, control; USF-2, upstream transcription factor 2. Values are given as means ± sem; n = 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05.

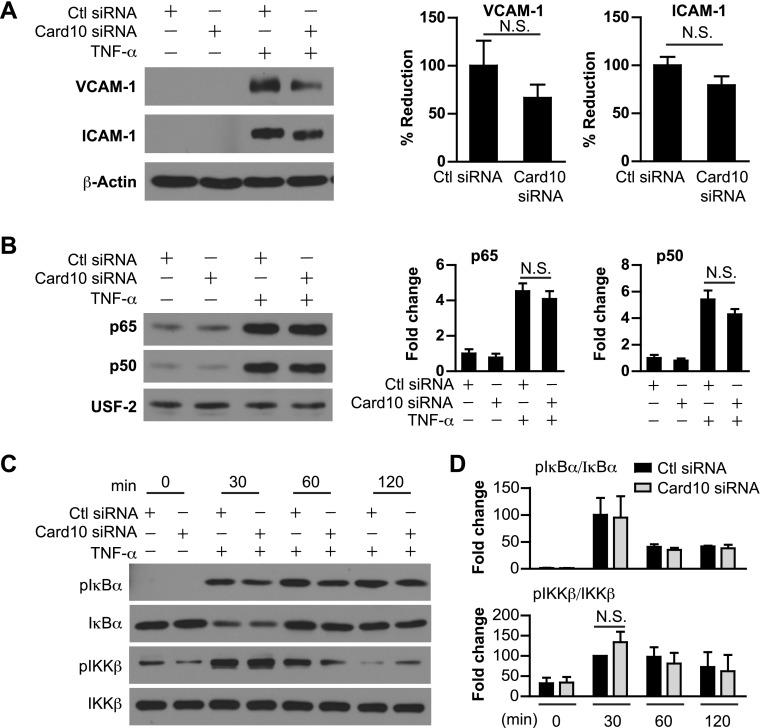

Card10 knockdown has no effect on TNF-α–induced gene expression and NF-κB signaling in ECs

We have previously demonstrated that miR-181b does not regulate NF-κB upstream signaling, such as activation of the IKK complex in TNF-α–treated ECs, which suggests that Card10 may not be involved in IKK complex activation in response to TNF-α. Indeed, knockdown of Card10 did not significantly affect TNF-α–induced target gene expression, including ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, there was no effect of Card10 knockdown on TNF-α–induced p65 or p50 nuclear translocation (Fig. 5B). Finally, knockdown of Card10 does not affect TNF-α–induced phospho-IκBα and -IKKβ in ECs (Fig. 5C). In summary, these data indicate that in TNF-α–treated ECs, Card10 does not regulate activation of NF-κB signaling and target gene expression, which suggests stimulus-specific regulation of NF-κB signaling and endothelial responses by miR-181b in ECs.

Figure 5.

Card10 knockdown has no effect on TNF-α–induced gene expression and NF-κB signaling in ECs. HUVECs were transfected with 30 nM control siRNA or Card10 siRNA. A) Cells were treated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 8 h and harvested for Western blot analysis. Expression of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 was normalized with β-actin. B) Expression of p65 and p50 in the nuclear fraction of HUVECs treated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 4 h was examined by Western blot analysis. C, D) HUVECs were treated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 0, 30, 60, and 120 min followed by Western blot analysis of phospho-IKK-β and -IκB-α expression. Ratios of phosphorylated protein to total protein were calculated. Ctl, control; N.S., not significant; USF-2, upstream transcription factor 2. Values are given as means ± sem; n = 3 independent experiments.

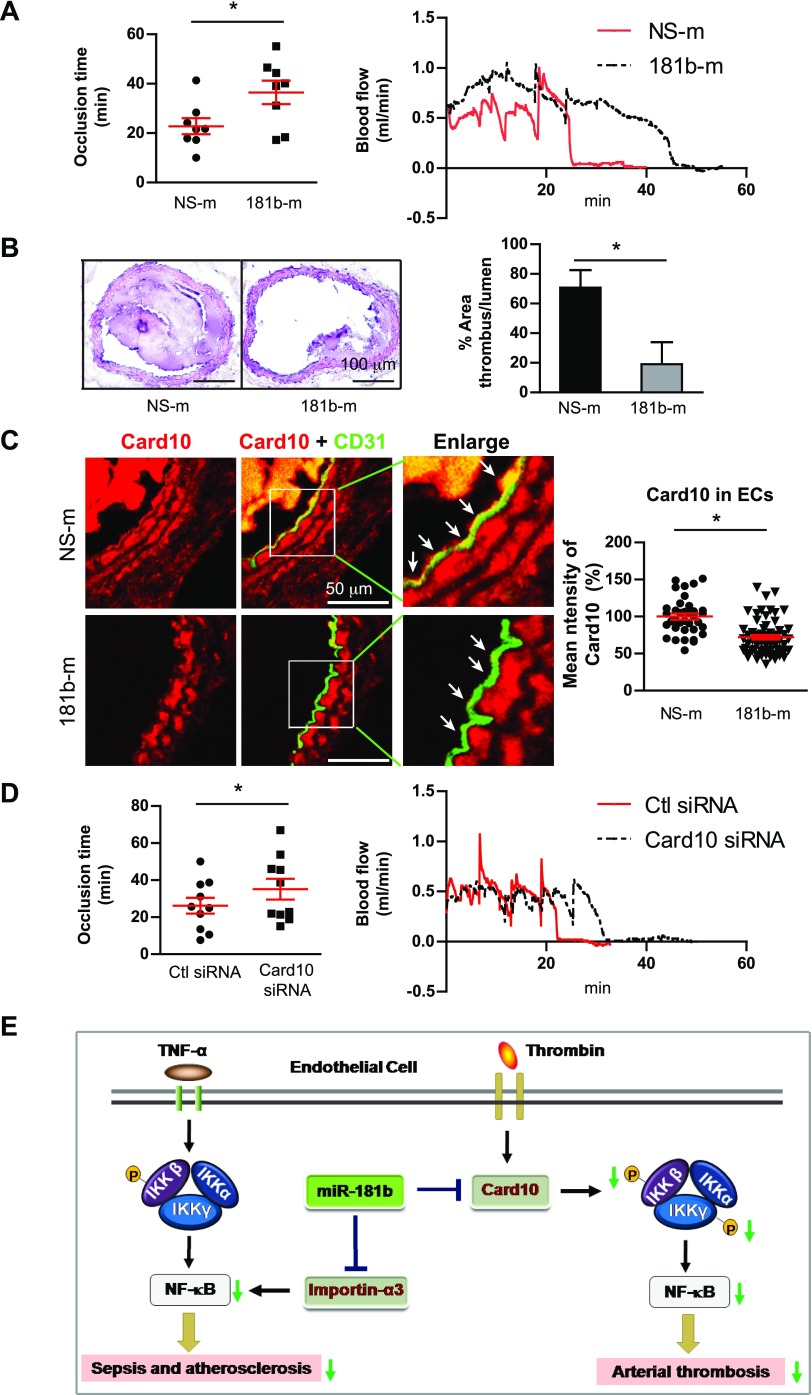

Systemic delivery of miR-181b or Card10 siRNA delays development of thrombosis in vivo

TF is a critical regulator of arterial thrombosis (27) and an NF-κB–responsive target gene (28, 29). Unsurprisingly, miR-181b also inhibited expression of TF (Supplemental Fig. 4A), which was phenocopied by Card10 knockdown (Supplemental Fig. 4B). To explore the role of miR-181b in thrombosis formation in vivo, C57BL/6 mice were therapeutically treated with liposomally encapsulated miR-181b mimics or nonspecific control mimics by tail-vein injection as described (20, 21). Thrombus formation in the carotid artery was induced by photochemical injury as previously described (24, 25). As shown in Fig. 6A, systemic delivery of miR-181b prolonged the mean time to occlusion by 1.5-fold. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of carotid arteries showed that miR-181b reduced thrombotic occlusion by 73% compared with nonspecific control–injected mice (Fig. 6B). Card10 expression was evaluated in endothelium of carotid arteries by immunostaining with antibodies against Card10 and CD31. Systemic delivery of miR-181b significantly reduced Card10 in vascular ECs of carotid arteries (Fig. 6C). Moreover, tail-vein injected mice that received siRNA to Card10 exhibited a 1.6-fold increase of mean time to occlusion, thereby phenocopying effects of miR-181b delivery (Fig. 6D). Taken together, these data demonstrate that systemic delivery of miR-181b mimics or Card10 siRNA can delay development of thrombosis in carotid arteries in vivo.

Figure 6.

Systemic delivery of miR-181b or Card10 siRNA delays development of thrombosis in vivo. C57BL/6 mice were administered with NS-m, 181b-m, control siRNA, or Card10 siRNA by tail-vein injection on 3 consecutive days. Photochemical injury was performed to induce development of thrombosis in carotid arteries. A) Occlusion times of the carotid arteries in NS-m– or miR-181b–treated mice (left). Two representative curves show blood flow of carotid arteries after injury in NS-m– and miR-181b–treated mice, respectively (right). Values are given as means ± sem; n = 8 per group. B) Thrombus formation revealed by hematoxylin and eosin staining of cross-sections of injured carotid arteries. Quantifications show ratios of thrombus to lumen areas. Data represent means ± sem; n = 4–5 per group. C) Frozen sections of carotid arteries were stained for anti-Card10 (red) and CD31 (green). Arrows indicate differential Card10 expression in ECs. Card10 expression was quantified in vascular ECs reflecting NS-m (n = 28 ECs) and 181b-m (n = 52 ECs), respectively. D) Occlusion times of carotid arteries in control siRNA– or Card10 siRNA–treated mice (left). Two representative curves show blood flow of carotid arteries after injury in control siRNA– and Card10 siRNA–treated mice, respectively (right). Data are given as means ± sem; n = 9–10 for each group. E) Schema of ligand-specific regulation of NF-κB signaling by miR-181b. In response to TNF-α, miR-181b inhibits importin-α3, an effect that inhibits downstream cytoplasmic-to-nuclear NF-κB accumulation in vascular endothelium during sepsis and atherosclerosis. In contrast, in response to thrombin, miR-181b inhibits Card10, an effect that inhibits upstream NF-κB signaling, activation of the IKK complex, and arterial thrombosis. Ctl, control. *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

We previously demonstrated that miR-181b reduced NF-κB nuclear translocation and vascular inflammation by targeting 3′-UTR of importin-α3 and inhibiting its expression (20, 21). In response to TNF-α–treated ECs, miR-181b did not inhibit NF-κB upstream signaling, such as IKK-β or IκBα phosphorylation. In this study, we have shown miR-181b uniquely inhibited thrombin-induced NF-κB upstream signaling by directly targeting Card10 in ECs and delayed thrombus formation in mouse carotid arteries after photochemical injury.

Arterial thrombosis is a complex and dynamic pathologic process. At sites of vascular injury, thrombin is produced by local activation of prothrombinase complex (30–32). TF, a membrane-bound glycoprotein, is a central initiator of the coagulation cascade; however, aberrant or prolonged expression may lead to potentially deleterious effects, such as vessel thrombosis. Role of miRNAs in regulation of TF and arterial thrombosis has only recently begun to emerge. For example, miR-223 and miR-19 inhibit TF expression in ECs (33–35). In the current study, we found that miR-181b inhibits TF expression in thrombin-treated ECs. TF is not likely an miR-181b target gene, as there are no predicted miR-181b binding sites at the 3′-UTR of TF by TargetScan, miRanda, and other algorithms. TF activation may be induced by a range of stimuli, including thrombin via NF-κB signaling (29, 36, 37). Reduction of TF by miR-181b, therefore, is likely indirect as a result of the inhibitory effect of miR-181b on thrombin-activated NF-κB signaling. An miRNA can have many different targets. Importin-α3 was identified as a direct target of miR-181b in our previous study (20, 21), which mediated effects of miR-181b that resulted in reduced NF-κB downstream signaling in the presence of TNF-α. Our current study identified Card10 as a direct target of miR-181b in the presence of thrombin. Knockdown of Card10 attenuates NF-κB signaling in response to thrombin, but not in response to TNF-α treatment. Furthermore, in response to thrombin, but not TNF-α, Card10 knockdown phenocopies effects of miR-181b on activation of upstream IKK complex, IκBα, and NF-κB–responsive gene expression. Finally, Card10 overexpression studies effectively rescued miR-181b–mediated inhibition of thrombin-activated, NF-κB–responsive genes, such as VCAM-1 and ICAM-1. These findings indicate that divergent targets of an miRNA determine its functional effects on cell signaling in a stimulus-specific manner (Fig. 6E). We found that miR-181b inhibits thrombin-induced NF-κB signaling and EC activation and, importantly delays development of arterial thrombosis in vivo. Our studies demonstrate that EC activation and dysfunction are important components of arterial thrombosis, which can be attenuated by intravenous delivery of either miR-181b mimics or Card10 siRNA.

Development of arterial thrombosis involves a number of different cell types and several signaling pathways. Inflammatory signaling is one of the major pathways that contribute to thrombosis. Conversely, thrombin activation may amplify EC inflammation, thereby propagating arterial injury. Initiation of coagulation often occurs after vascular endothelial injury and exposure of extracellular matrix. Leukocyte–EC and –platelet interactions are critical steps in promotion of arterial thrombosis. These cellular events reflect changes at the molecular level, such as expression of a number of genes, including TF and adhesion molecules, that are controlled by both inflammatory and hemostatic pathways. Inflammatory signaling induces expression of adhesion molecules and TF, thereby promoting leukocyte–EC and leukocyte–platelet interactions, hypercoagulability, and impaired fibrinolysis. miR-181b delays thrombotic occlusion in carotid arteries after photochemical injury, which suggests that inhibition of inflammatory signaling may be an attractive approach to target prothrombotic conditions.

In summary, miRNAs are emerging as potential regulators of arterial thrombosis. Our study demonstrates that miR-181b is an important suppressor of thrombin-induced EC activation and arterial thrombosis by directly targeting Card10. siRNA-mediated knockdown of Card10 uniquely regulates upstream NF-κB signaling in response to thrombin, but not TNF-α, which suggests stimulus-specific regulation of NF-κB signaling and endothelial responses by miR-181b in ECs. These studies highlight the broader relevance of miRNA-dependent targets in response to ligand-specific signaling in ECs. Delivery of miR-181b or Card10 inhibition may constitute a new therapeutic approach to reduce arterial thrombosis by improving vascular EC inflammatory and procoagulant function.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants HL115141 and HL117994 (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute), and GM115605 (National Institute of General Medical Sciences) (all to M.W.F.); the Arthur K. Watson Charitable Trust (to M.W.F.); the Dr. Ralph and Marian Falk Medical Research Trust, Bank of America, N.A. Trustee (to M.W.F.); a State Scholarship Fund of the China Scholarship Council (to J.L.); a Jonathan Levy Research Fund (to M.W.F.), the American Heart Association (SDG#15SDG25400012) (to X.S.); and a Boston Nutrition Obesity Research Center Pilot and Feasibility award under NIH National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant P30KD046200 (to X.S.). Author contributions: X. Sun and M. W. Feinberg designed research; J. Lin, S. He, X. Sun, Y. Deng, D. Yang, S. Haemmig, and M. W. Feinberg analyzed data; J. Lin, S. He, X. Sun, G. Franck, Y. Deng, S. D. Yang, and Haemmig performed research; J. Lin, X. Sun, and M. W. Feinberg wrote the paper; and X. Sun, A. K. M. Wara, B. Icli, D. Li, and M. W. Feinberg contributed to experimental design.

Glossary

- 181b-m

microRNA-181 mimic

- Card10

caspase recruitment domain family member 10

- EC

endothelial cell

- ICAM

intercellular adhesion molecule

- miRNA

microRNA

- miR-181b

microRNA-181b

- NS-m

miRNA nonspecific negative control mimic

- PAR

protease-activated receptor

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

- TF

tissue factor

- UTR

untranslated region

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jackson S. P. (2011) Arterial thrombosis--insidious, unpredictable and deadly. Nat. Med. 17, 1423–1436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barua R. S., Ambrose J. A. (2013) Mechanisms of coronary thrombosis in cigarette smoke exposure. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 33, 1460–1467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henry P. D., Cabello O. A., Chen C. H. (1995) Hypercholesterolemia and endothelial dysfunction. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 6, 190–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samad F., Ruf W. (2013) Inflammation, obesity, and thrombosis. Blood 122, 3415–3422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furie B., Furie B. C. (1988) The molecular basis of blood coagulation. Cell 53, 505–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croce K., Libby P. (2007) Intertwining of thrombosis and inflammation in atherosclerosis. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 14, 55–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Popović M., Smiljanić K., Dobutović B., Syrovets T., Simmet T., Isenović E. R. (2012) Thrombin and vascular inflammation. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 359, 301–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delekta P. C., Apel I. J., Gu S., Siu K., Hattori Y., McAllister-Lucas L. M., Lucas P. C. (2010) Thrombin-dependent NF-kappaB activation and monocyte/endothelial adhesion are mediated by the CARMA3·Bcl10·MALT1 signalosome. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 41432–41442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Hinsbergh V. W. (2012) Endothelium--role in regulation of coagulation and inflammation. Semin. Immunopathol. 34, 93–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hadi H. A., Carr C. S., Al Suwaidi J. (2005) Endothelial dysfunction: cardiovascular risk factors, therapy, and outcome. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 1, 183–198 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esmon C. T. (2003) Inflammation and thrombosis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 1, 1343–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coughlin S. R. (2005) Protease-activated receptors in hemostasis, thrombosis and vascular biology. J. Thromb. Haemost. 3, 1800–1814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirano K. (2007) The roles of proteinase-activated receptors in the vascular physiology and pathophysiology. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27, 27–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rezaie A. R. (2014) Protease-activated receptor signalling by coagulation proteases in endothelial cells. Thromb. Haemost. 112, 876–882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplanski G., Marin V., Fabrigoule M., Boulay V., Benoliel A. M., Bongrand P., Kaplanski S., Farnarier C. (1998) Thrombin-activated human endothelial cells support monocyte adhesion in vitro following expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1; CD54) and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1; CD106). Blood 92, 1259–1267 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartha K., Brisson C., Archipoff G., de la Salle C., Lanza F., Cazenave J. P., Beretz A. (1993) Thrombin regulates tissue factor and thrombomodulin mRNA levels and activities in human saphenous vein endothelial cells by distinct mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 421–429 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grabiner B. C., Blonska M., Lin P. C., You Y., Wang D., Sun J., Darnay B. G., Dong C., Lin X. (2007) CARMA3 deficiency abrogates G protein-coupled receptor-induced NF-kappaB activation. Genes Dev. 21, 984–996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Israël A. (2010) The IKK complex, a central regulator of NF-kappaB activation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a000158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang C., Lin X. (2012) Regulation of NF-κB by the CARD proteins. Immunol. Rev. 246, 141–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun X., He S., Wara A. K., Icli B., Shvartz E., Tesmenitsky Y., Belkin N., Li D., Blackwell T. S., Sukhova G. K., Croce K., Feinberg M. W. (2014) Systemic delivery of microRNA-181b inhibits nuclear factor-κB activation, vascular inflammation, and atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circ. Res. 114, 32–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun X., Icli B., Wara A. K., Belkin N., He S., Kobzik L., Hunninghake G. M., Vera M. P., Blackwell T. S., Baron R. M., Feinberg M. W.; MICU Registry (2012) MicroRNA-181b regulates NF-κB-mediated vascular inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 1973–1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medoff B. D., Landry A. L., Wittbold K. A., Sandall B. P., Derby M. C., Cao Z., Adams J. C., Xavier R. J. (2009) CARMA3 mediates lysophosphatidic acid-stimulated cytokine secretion by bronchial epithelial cells. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 40, 286–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stewart S. A., Dykxhoorn D. M., Palliser D., Mizuno H., Yu E. Y., An D. S., Sabatini D. M., Chen I. S., Hahn W. C., Sharp P. A., Weinberg R. A., Novina C. D. (2003) Lentivirus-delivered stable gene silencing by RNAi in primary cells. RNA 9, 493–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y., Fang C., Gao H., Bilodeau M. L., Zhang Z., Croce K., Liu S., Morooka T., Sakuma M., Nakajima K., Yoneda S., Shi C., Zidar D., Andre P., Stephens G., Silverstein R. L., Hogg N., Schmaier A. H., Simon D. I. (2014) Platelet-derived S100 family member myeloid-related protein-14 regulates thrombosis. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 2160–2171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Westrick R. J., Winn M. E., Eitzman D. T. (2007) Murine models of vascular thrombosis (Eitzman series). Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27, 2079–2093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leger A. J., Covic L., Kuliopulos A. (2006) Protease-activated receptors in cardiovascular diseases. Circulation 114, 1070–1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Furie B., Furie B. C. (2008) Mechanisms of thrombus formation. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 938–949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moll T., Czyz M., Holzmüller H., Hofer-Warbinek R., Wagner E., Winkler H., Bach F. H., Hofer E. (1995) Regulation of the tissue factor promoter in endothelial cells. Binding of NF kappa B-, AP-1-, and Sp1-like transcription factors. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 3849–3857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y. D., Ye B. Q., Zheng S. X., Wang J. T., Wang J. G., Chen M., Liu J. G., Pei X. H., Wang L. J., Lin Z. X., Gupta K., Mackman N., Slungaard A., Key N. S., Geng J. G. (2009) NF-kappaB transcription factor p50 critically regulates tissue factor in deep vein thrombosis. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 4473–4483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coughlin S. R. (2000) Thrombin signalling and protease-activated receptors. Nature 407, 258–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mackman N. (1997) Regulation of the tissue factor gene. Thromb. Haemost. 78, 747–754 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Minami T., Sugiyama A., Wu S. Q., Abid R., Kodama T., Aird W. C. (2004) Thrombin and phenotypic modulation of the endothelium. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24, 41–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li S., Chen H., Ren J., Geng Q., Song J., Lee C., Cao C., Zhang J., Xu N. (2014) MicroRNA-223 inhibits tissue factor expression in vascular endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis 237, 514–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li S., Ren J., Xu N., Zhang J., Geng Q., Cao C., Lee C., Song J., Li J., Chen H. (2014) MicroRNA-19b functions as potential anti-thrombotic protector in patients with unstable angina by targeting tissue factor. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 75, 49–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eisenreich A., Leppert U. (2014) The impact of microRNAs on the regulation of tissue factor biology. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 24, 128–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rahman A., Anwar K. N., True A. L., Malik A. B. (1999) Thrombin-induced p65 homodimer binding to downstream NF-kappa B site of the promoter mediates endothelial ICAM-1 expression and neutrophil adhesion. J. Immunol. 162, 5466–5476 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parry G. C., Mackman N. (1995) Transcriptional regulation of tissue factor expression in human endothelial cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 15, 612–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]