Purpose and intended audience

Each year, the Canadian Cancer Statistics publication provides an estimate of expected case counts and rates for common cancer sites for the current year in Canada as a whole and in the provinces and territories. This monograph expands on the Canadian Cancer Statistics publication by providing historical and projected cancer incidence frequencies and rates at national and regional levels from 1983 to 2032. The aim is that this monograph will be an important resource for health researchers and planners. Most importantly, it is hoped the monograph will:

provide evidence-based input for the development of public health policy priorities at the regional and national levels; and

guide public health officials in planning strategy including designing and evaluating preventive interventions and planning resources (treatment requirements) and infrastructure for future cancer control and care intended to reduce the burden of cancer in Canada.

Executive Summary

In this monograph, we present historical and projected cancer incidence frequencies and rates for Canada, excluding non-melanoma skin cancers (i.e. basal and squamous carcinomas), in 1983 to 2032. The information is intended to help in planning strategy and allocating resources and infrastructure for future cancer control and health care.

Projected changes in cancer incidence rates

From 2003–2007 to 2028–2032, the age-standardized incidence rates (ASIRs) for all cancers combined are predicted to decrease in Canadian males by 5%, from 464.8 to 443.2 per 100 000 population, and increase in Canadian females by 4%, from 358.3 to 371.0 per 100 000. The overall decrease in cancer rates in males will be driven by the decrease in lung cancer rates in men aged 65* or older and in prostate cancer rates in men aged 75 or older. The overall increase in cancer rates in females reflects the predicted rise in lung cancer rates in women aged 65 or older. The increase also represents the expected increase in cancers of the uterus, thyroid, breast (in females under 45), leukemia, pancreas, kidney and melanoma.

The largest changes in ASIRs projected over the 25-year forecasting horizon are increases in thyroid cancer (55% in males and 65% in females) and liver cancer in males (43%) and decreases in larynx cancer (47% in males and 59% in females), lung cancer in males (34%) and stomach cancer (30% in males and 24% in females). The incidence rate of lung cancer in females is projected to continue to rise by 2% from 2003–2007 to 2008–2012 and then start to decrease in the last 20 projection years, by 18%. Breast cancer incidence is expected to change the least (an increase of less than 1%) of all cancers in females. The predicted changes in the rates for colorectal cancer are below the medians in all cancers, with a decrease of 6% for both males and females during the entire projection period. The rates for prostate cancer are projected to be stable, based on an assumption of future stabilization in the prevalence of screening.

New cancer cases to rise

The annual number of new cancer cases is predicted to increase by 84% in Canadian males, from 80 800 in 2003–2007 to 148 400 in 2028–2032, and by 74% in Canadian females, from 74 200 to 128 800.

Drivers of the changes in cancer cases

The primary reason for the increase in the number of all newly diagnosed cancer cases will be the aging of the Canadian population and, to a lesser extent, the increase in population size. Changes in the risk of cancer will constitute a relatively small component of the projected increase in new cases. Preventive interventions can have a strong influence on future incidence rates for individual cancer types.

Most common cancers

The most common new cancers in males—prostate, colorectal, lung and bladder cancers, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma—are projected to remain the same from 2003–2007 to 2028–2032, but colorectal cancer is predicted to outrank lung cancer as the second most frequently diagnosed cancer by 2028–2032. For females, breast, lung, colorectal and uterine cancers figure as the top 4 most common incident cancers in both periods. However, thyroid cancer will overtake non-Hodgkin lymphoma as the fifth most common cancer by 2028–2032.

Incidence by geographical region

There is an east–west gradient in incidence across Canada. The highest incidence rates for most cancers are projected to be in eastern Canada (Atlantic region [New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador], Quebec or Ontario) for both males and females. While British Columbia is projected to continue to have the lowest incidence rates for the majority of cancers in both sexes, this province will also continue to experience the highest rates for esophageal cancer in females, liver cancer in both sexes and testis cancer. The Atlantic region is projected to have the lowest incidence rates for cancers of the breast, uterus and ovary in females, and for liver cancer and leukemia in both sexes. In contrast, this region is projected to experience elevated incidence rates in males for about half the cancers studied.

The incidence rates for all cancers combined are projected to continue to be highest for males in the Atlantic region and for females in Quebec in 15 years but in Ontario thereafter, and lowest in British Columbia. The inter-regional differences are larger in males than in females, possibly due to variations in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing (for prostate cancer) and risk factors. In both males and females, colorectal cancer incidence rates will remain highest in the Atlantic region and lowest in British Columbia. Lung cancer incidence rates are projected to be highest in Quebec and lowest in Ontario and British Columbia for both sexes. The similar regional rates of breast cancer in females are expected to persist. The significantly lowest rates of prostate cancer in Quebec are projected to continue, as are the elevated rates in the Atlantic region.

Incidence by sex and age

Cancer is more common in males than in females except in those aged under 55. The overall cancer incidence rate in men aged 65 or older has been falling and will continue to do so. The decrease in lung cancer rates in men aged 65 or older from decreased tobacco use and the decrease in prostate cancer rates in men aged 75 or older have contributed to the overall decrease in this age range. In women aged 65 or older, the relatively stable rate is primarily the result of an increase in lung cancer incidence offset by decreases in incidence for the other cancer sites. This stable trend is projected to continue. Targeted cancer prevention efforts and specific needs for health care services can be expected to vary at different points in the age continuum for males and females.

Smoking-related cancers

Between 2003–2007 and 2028–2032, substantial risk reductions are projected for major common tobacco-related cancers in Canada, even with relatively lower reductions or delayed downturn trends in females. The differences between males and females in the predicted incidence trends of these cancers mirror the historical pattern of reductions in smoking prevalence that took place in males 20 years earlier than in females. Given the lag of 20 years or more between the reduction in smoking and subsequent decrease in cancer incidence, the incidence rates in females will likely begin to drop more noticeably over the longer term. By comparison, the risk of cancer incidence is forecast to increase for non-tobacco-related cancers.

Cancers associated with excess weight and physical inactivity

Over the 25-year projection period, the incidence rates for cancers associated with excess weight and physical inactivity are estimated to increase by 0.6% to 16% for cancers of the uterus, kidney, pancreas, female breast and male esophagus, in descending order. Incidence rates are expected to decrease by 2% to 6% for colorectal and female esophageal cancer. Increased obesity prevalence in Canada may contribute to the increased incidence trends.

Most common infection-associated cancers

From 2003–2007 to 2028–2032, the incidence rates of liver cancer are expected to escalate almost 3 times faster in males than in females (43% vs. 15%), while the rate of stomach and cervical cancer will continue to decrease by 20% to 30%. The ongoing increasing trend of liver cancer incidence is possibly linked to the historical increase and continued high incidence in hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, the aging of the previously infected population, and increasing immigration from areas where risk factors such as hepatitis B virus (HBV) are prevalent. The persisting decrease in incidence of stomach cancer may be explained by improved healthy behaviours, such as decreased smoking and changes in diet, and increased recognition and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. The continuing downward trend in the rates of cervical cancer is mainly attributable to general population screening with the Papanicolaou (Pap) test and successful treatment of screening-detected premalignant lesions. The immunization of school-aged children with the vaccine for human papilloma virus (HPV) is anticipated to further reduce the incidence of cervical cancer.

Implications for cancer control strategies

The projected aging and growth of the population are expected to lead to a progressive and significant increase in the total number of new cancer cases in Canada over the next 25 years. Consequently, this report indicates the need to continue to strengthen cancer control strategies and leverage resources to meet future health care requirements and reduce the burden of cancer in Canada. Although incidence rates are projected to decrease for many cancers, the rates for some cancers, for example, thyroid, liver, uterus, pancreas, kidney and leukemia, are estimated to increase. Additional etiological research is needed to better understand risk factors and guide prevention efforts.

This monograph underscores the importance of cancer prevention by curbing smoking; promoting healthy eating, physical activity and weight management; enhancing uptake of cancer screening; and increasing coverage of HPV vaccination. The implication of future changes in our demographic profiles and cancer trends should be addressed from the full spectrum of cancer control, including research and surveillance, prevention and early detection, treatment, and psychosocial, palliative and medical care.

Chapter 1: Introduction

A prominent characteristic of current sociodemographic changes in Canada is the accelerated growth in the number and proportion of seniors. Figure 1.1 shows that the percentage of men aged 65* or older is projected to increase from 12% in 2003–2007 to 21% in 2028–2032 and of women the same age from 15% to 24% in the same period. The increase in the number of older adults is a consequence of reduced mortality rates in all age groups and the aging of the baby boomer generation. This demographic trend is expected to result in a significantly higher number of cancer diagnoses and therefore demand for health care services. Defining the expected societal burden of cancer can provide evidence-based input into planning cancer control programs, leveraging resources to meet future health care needs and reducing the expected burden of cancer in Canada.

FIGURE 1.1. Historic and projected growth in average annual population in Canada by age, 1983–2032.

We quantify the future burden of cancer from two perspectives: age-standardized rate and the number of new cancer cases. Changes in incidence rates communicate changes in risk of developing cancer over time. The future number of new cases is a consequence of changes both in the cancer rates and in the population size and composition.

The main source of estimates of expected case counts and rates for common cancer sites in the current year for Canada and the provinces and territories is the annual Canadian Cancer Statistics report.1 These estimates provide important information for cancer control planners, public policy analysts, and provincial and territorial health care professionals who need to know the relative burden of different types of cancer and for different geographical regions.

Currently, there are no widely available long-term national projections for Canada, whereas several other developed countries have documented their profiles.2–5 To map out such a possible future cancer scenario, this monograph presents estimates of cancer incidence frequencies and rates in Canada for 25 cancer sites by geographical area, sex and age group through 2028–2032.

Chapter 2: Data and Methods

2.1 Data

The observed cancer incidence data used for the projections cover 1983 to 2007, which represents the most recent period for which data are available for all parts of Canada. We extracted data from the Canadian Cancer Registry (CCR) for 1992 to 2007 and from the National Cancer Incidence Reporting System (NCIRS) for the earlier years. While the CCR is a person-oriented database, the NCIRS is an event-oriented database with cases diagnosed from 1969 to 1991. The cases in the NCIRS were coded in or converted to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9).6 Projections were prepared for the most frequent invasive primary cancers (including in situ bladder cancers but excluding non-melanoma skin cancer (i.e. basal and squamous carcinoma). We generally defined cancer cases based on the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition (ICD-O-3) and classified them using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program Incidence Site Recode shown in Table 2.1.7,8 Cases retrieved from the NCIRS used equivalent ICD-9 codes. Changes in cancer definition over time were derived following the methods outlined in the Canadian Cancer Statistics.1

TABLE 2.1.

Cancer definitions for incidence

| Cancer | ICD-O-3 site/histology typea |

|---|---|

| (Incidence) | |

| Oral | C00–C14 |

| Esophagus | C15 |

| Stomach | C16 |

| Colorectal | C18–C20, C26.0 |

| Liver | C22.0 |

| Pancreas | C25 |

| Larynx | C32 |

| Lung | C34 |

| Melanoma | C44 (Type 8720–8790) |

| Breast | C50 |

| Cervix | C53 |

| Body of uterus | C54–C55 |

| Ovary | C56.9 |

| Prostate | C61.9 |

| Testis | C62 |

| Kidney | C64.9, C65.9 |

| Bladder (including in situ) | C67 |

| Central nervous system | C70–C72 |

| Thyroid | C73.9 |

| Hodgkin lymphomab | Type 9650–9667 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphomab | Type 9590–9596, 9670–9719, 9727–9729 |

| Type 9823, all sites except C42.0,.1,.4 | |

| Type 9827, all sites except C42.0,.1,.4 | |

| Multiple myelomab | Type 9731, 9732, 9734 |

| Leukemiab | Type 9733, 9742, 9800–9801, 9805, 9820, 9826, |

| 9831–9837, 9840, 9860–9861, 9863, 9866–9867, | |

| 9870–9876, 9891, 9895–9897, 9910, 9920, 9930– | |

| 9931, 9940, 9945–9946, 9948, 9963–9964 | |

| Type 9823 and 9827, sites C42.0,.1,.4 | |

| All other cancers | All sites C00–C80, C97 not listed above |

| Mesotheliomab | 9050-9055 |

| Kaposi's sarcomab,c | 9140 |

| Small intestine | C17 |

| Anus | C21 |

| Gallbladder | C23 |

| Other digestive system | C22.1, C24, C26.8–9, C48 |

| Other respiratory system | C30–31, C33, C38.1–9, C39 |

| Bone and joints | C40–41 |

| Soft tissue (including heart) | C38.0, C47, C49 |

| Other skin | C44 excl. 8050:8084, 8090:8110, 8720:8790 |

| Other female genital system | C51–52, C57–58 |

| Penis | C60 |

| Other male genital system | C63 |

| Ureter | C66 |

| Other urinary system | C68 |

| Eye | C69 |

| Cancer | ICD-O-3 site/histology typea |

| (Incidence) | |

| Other endocrine | C37.9, C74, C75 |

| Other, ill-defined, and unknown | Type 9740, 9741, 9750–9758, 9760–9769, 9950– |

| 9962, 9970–9989; C76.0–76.8 (type 8000–9589); | |

| C80.9 (type 8000–9589); C42.0–42.4 (type 8000– | |

| 9589); C77.0–C77.9 (type 8000–9589) | |

| All cancers | All invasive sites |

ICD-O-3 refers to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology,Third Edition.7Cancers are classified by SEER Incidence Site Record.8

Histology types 9590–9989 (leukemia, lymphoma and multiple myeloma), 9050–9055 (mesothelioma) and 9140 (Kaposi's sarcoma) are excluded from other specific organ sites.

Data are not available for Ontario and Canada.

Population estimates for Canada and the provinces/territories are based on quinquennial censuses conducted from 1981 to 2006. We used intercensal estimates prepared by Statistics Canada for the years between these censuses and postcensal estimates for 2007 to 2010.9 Projected population estimates were used for 2011 to 2032, as prepared by Statistics Canada under assumptions of medium growth (scenario M1).10 The scenario M1 incorporates medium growth and historical trends (1981–2008) of interprovincial migration. For the total population, the low and high growth scenarios are about 6% below and above the M1 scenario, but this range is reduced to 3% for ages 65 or older.

Data on cancer incidence counts and population estimates were summarized into 5-year age groups (0–4, 5–9, …, 80–84, 85+) and 5-year periods of diagnosis (1983–1987, 1988–1992, 1993–1997, 1998–2002, 2003–2007) by sex and geographical region (British Columbia, the Prairie provinces [Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba] individually and together, Ontario, Quebec, the Atlantic provinces [New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador] individually and together, and the North [Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut]). The projected population figures were similarly aggregated for 5 projection quinquennia (2008–2012, 2013–2017, 2018–2022, 2023–2027, 2028–2032). The single-year data from 1994 to 2007 were used for projecting prostate cancer incidence. Rates for each category were calculated by dividing the number of cases in each category (a combination of cancer site, sex, region, period, and age group) by the corresponding population figure. These age-specific rates were standardized to the 1991 Canadian population (Table 2.2), using the direct method,11 to obtain the age-standardized incidence rates (ASIRs).

TABLE 2.2.

1991 Canadian standard population

| Age Group | Population (per 100 000) |

|---|---|

| 0–4 | 6946.40 |

| 5–9 | 6945.40 |

| 10–14 | 6803.40 |

| 15–19 | 6849.50 |

| 20–24 | 7501.60 |

| 25–29 | 8994.40 |

| 30–34 | 9240.00 |

| 35–39 | 8338.80 |

| 40–44 | 7606.30 |

| 45–49 | 5953.60 |

| 50–54 | 4764.90 |

| 55–59 | 4404.10 |

| 60–64 | 4232.60 |

| 65–69 | 3857.00 |

| 70–74 | 2965.90 |

| 75–79 | 2212.70 |

| 80–84 | 1359.50 |

| 85+ | 1023.70 |

| Total | 100 000.00 |

Data source: Census and Demographics Branch, Statistics Canada

Note: The Canadian population distribution is based on the final postcensal estimates of the July 1, 1991, Canadian population, adjusted for census undercoverage. The age distribution of the population has been weighted and normalized.

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 Projection methods

Future trends in cancer incidence rates are generally estimated by extending past trends using statistical models. A statistical model formulates the relationship between the risk factors and the cancer rates, and projections can be obtained by applying the future times in the equation.

There are several methods for projecting cancer burden, differing in terms of the type of model, selection of the data used for model fitting, and the method of extrapolating the model components into future periods. The model type diverges from simple linear or log-linear regression of age-specific rates or counts against time2,12,13 to age–period–cohort (APC) modelling. 11,14,15 Within the framework of APC models, effects of age, period and cohort are addressed in heterogeneous ways such as generalized linear models16,17 including their derivative, Nordpred method, based on a step function on 5-year intervals,3,15 generalized additive models18,19 with polynomial15,20 or spline smoothing methods,21 and Bayesian models22 with Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulation.23 The link function is either common exponential11,14,22 or non-canonical power.3,15 A model is fitted to all available data or their subset for an adequate fit through a goodness-of-fit test.3,15 The assumptions used for extrapolating the observed trends include keeping current rates unchanged in future,24 continuing overall historical trend,2,22 extending only the most recent trend,3,15 and adjusting the extent to which the observed trend are likely to influence the future.3,15 To develop the most accurate profile of future cancer burden, we used the major projection models to produce projections of current rates as would have been forecast 15 or 20 years ago based on the long-term data series in Canada, compared the projected rates with those observed, and concluded with a cancer-dependent modelling approach. This multiple modelling approach consists of the following models and integrates the strengths of these models.

The common projection models relate incidence to the 3 intrinsically interdependent time dimensions: age at diagnosis (age), year of diagnosis (period), and year of birth (cohort). The Nordpred APC model3,15 uses the power-5 link function instead of the traditional logarithmic link to reduce the exponential changes; summarizes the linear trends in period and cohort over the observed data into a drift component and then arithmetically attenuates the drift into the future to damp the impact of past trends in the future; chooses data for model fitting; and chooses the drift for extrapolations. Nordpred with its standard and various modified parameter settings was the primary method used in the projections in this monograph. When cohort effects were not present, we considered a Nordpred model without cohort component as an alternative. When there were too few observed cases to properly estimate model parameters via the Nordpred method or projections from

Nordpred seemed unlikely based on biological and clinical grounds, we pursued Bayesian APC models22 or submodels with various prior settings, 5-year average method or applying a relative percentage adjustment to national estimates to obtain the estimates for a jurisdiction. Bayesian models estimate the age-specific rates from their posterior distribution through repeated iterative sampling. The 5-year average model assumes the current age-specific rates will remain in future. In addition, we used an age-specific trend power-5 model fitted to most recent data for the projections of prostate cancer to reduce the impact of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening on the long-term historical trend.

All the long-term projection models depend on an assumption of the continuity of past trends in age-specific rates, but with different extent. The details of these models, model section methods, and ‘‘best’’ models are described below.

2.2.1.1 Projection models

2.2.1.1.1 Nordpred power-5 models—modified generalized linear models (NP_ADPC and NP_ADP)

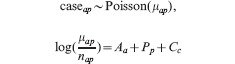

The Nordpred approach was developed as part of a comprehensive analysis of cancer trends in the Nordic countries.3,25 The approach is based on a standard APC Poisson regression model14,16,26 but has been shown to give more realistic predictions, especially for long-term projections.15,27 It is now one of the most frequently used methods for cancer projections worldwide.28–31 The log-linear relationship between the rate and the covariates in the standard model produces predictions in which the rates grow exponentially with time. Nordpred uses a power-link function instead of the log-link function to lower this growth. The power-link function is an approximation of the log-link function based on Box-Cox power transformation theory, in which  . The Nordpred model is defined as

. The Nordpred model is defined as

where Rap is the incidence rate for age group a in calendar period p, which is the mean count μap of caseap divided by the corresponding population size nap; Aa, Pp and Cc are the non-linear components of age group a, period p and cohort c, respectively; and D is the common linear drift parameter of period and cohort.26 A cohort is calculated by subtracting age from period: c = A + p – a, with A = number of age groups (i.e. 18).

To achieve an adequate fit of each data to the model, the number of 5-year periods on which the projections should be based is chosen in the Nordpred software by using a goodness-of-fit test to successively remove the earlier periods. To extrapolate the model for future periods, two approaches are considered instead of simple continuation of the overall historical trend. Firstly, the software determines whether the average trend across all observed values, or the slope for the last 10 years of observed values, is used as the drift component D to be projected. The software does this by testing for departure from a linear trend. If the trend across the entire observation period departs significantly from linearity, only the trend in the most recent 10 years is used for projection. The ‘‘recent’’ option in the software allows choosing between using the average trend (recent = F) or the trend for the last 10 years (recent = T). Secondly, to attenuate the impact of current trends in future periods, a ‘‘cut trend’’ (or ‘‘drift’’) option is used, which is a vector of proportions indicating how much to cut the trend estimate for each 5-year projection period. A gradual reduction in the drift parameter of 25%, 50%, 75% and 75% in the second, third, fourth and fifth 5-year period, respectively, is used as a default ‘‘cut’’ in Nordpred.3,25

To explore accurate projection methods for this study, we compared the power-5 models and Poisson models (using log link instead of the power link in equation NP_ADPC), with the Nordpred option recommendations and their modifications. The default ‘‘cut trend’’ vector was modified to reduce or increase the impact of current trend in future periods.

For each age group, a minimum of 5 cases in each 5-year period was required; for age groups below this limit, the average number of cases in the last 2 periods was used to calculate future rates. If a limit of 10 had been used, as in the report for Nordic countries in most of the situations,3 a larger number of age groups would have been based on the average rates. This would reduce the effect of current trends, so a low limit of 5 was chosen as a trade-off between unbiased estimation of the underlying trend and a large estimation error.

In addition to the full ADPC model, we also considered using an age-drift-period model (ADP) with power-5 link functions for cancers with average annual counts of fewer than 50 over the last observed 5 years when cohort effects were not present based on a significance test:

This ADP model was used for rare cancers in Iceland in an analysis of cancer trends in the Nordic countries.3

2.2.1.1.2 Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo method

Instead of a maximum likelihood approach, we applied a Bayesian framework to the APC model or submodel. The Bayesian method incorporates prior knowledge into the model to derive a posterior distribution and uses MCMC approximations22,23 for inference (parameter estimates). We considered this approach for situations in which average annual count over the last observed 5 years was less than or equal to 10 (when there were too few observed cases to properly estimate model parameters via the Nordpred method) or if projections from Nordpred seemed unlikely. We considered 2 Bayesian approaches.

2.2.1.1.2.1 Bayesian APC model with autoregressive prior – Bray approach (B_APC)

For the classical APC Poisson model,26 Bray specified a second-order autoregressive prior model to smooth age, period and cohort effects and to extrapolate period and cohort effects.22,23 The model can be written as,

|

Supposing that we compute N-period projections based on P-period observed data, there are total C = A+P −1 cohorts. With the Nordpred model, an individual cohort c can be calculated as c = A + p − a. The prior distributions are defined as follows. For the A age effects:

|

For the P + N period effects:

|

For the C + N cohort effects:

|

The variance parameters τA, τP and τC (determining the smoothness of age, period and cohort effects, respectively) are given the same gamma prior,

Fitted and projected rates are derived by combining the simulated age, period and cohort effects based on

Three MCMC chains were run for a ‘‘burn-in’’ of 50 000 iterations. Parameter estimates (posterior medians) were based on an additional 50 000 iterations for each chain, thinned to every thirtieth sample (N=150 000 samples). Chain convergence was assessed via the Gelman-Rubin statistic, examination of sample autocorrelation, and visual inspection. All Bayesian modelling was implemented in WinBUGS (Windows Version of Bayesian inference Using Gibbs Sampling);32 additional details can be found elsewhere.33

2.2.1.1.2.2 Bayesian age–period model using national coefficients as priors’ means for regional projections (B_AP)

To stabilize regional estimates, initial or ‘‘prior’’ distributions based on national data were assumed for regional parameters and then updated using the actual regional data. The model can be written as

|

We first used the model to estimate national-level age and period coefficients, denoted as Âa P̂p respectively. Regional age Aa and period Pp effects were then given normally distributed priors with means equal to the corresponding national estimates,

|

where variance parameters τA, τP were given the same gamma prior,

Following Spiegelhalter et al.,34 corner constraints were imposed on the first age effect (A1 = 0) to facilitate computations.

2.2.1.1.3 Five-year average model (AVG)

The 5-year average model assumes that the age-specific average rates of cancer incidence in the most recent 5 years of observed data will remain constant in future years, so that future numbers of cancer would be affected only because of demographic changes in the population. The projected rates are calculated as

where Ra represents the rate for age group a, Cat the number of cases for age group a in year t, and Pat the population size for age group a in year t.

2.2.1.1.4 Relative percent adjustment method – regional projections derived from scaling down national-level projections (SD)

For a cancer site in a region with average annual counts over the last observed 5 years of fewer than 10, the age-specific counts were also calculated by adjusting the national estimates (based on a modified method used in the Cancer Registry of Norway).35 Let w denote the relative difference of the averages of the ASIRs in the last 5 observation years between the region and the whole country, that is,

then the cancer incidence rate in a region R, age group a and period p,

where RNap, CNap and PNap are the national cancer incidence rate, count and population size at age group a and period p, respectively. For example, if the region had 5% lower rates than the national average in the last 5 observation years, the age-specific rates in each future period were adjusted down by 5% for that region. We therefore have the corresponding number of new cancer cases,

2.2.1.1.5 Age-specific trend power-5 model fitting single-year data for short-term projections of prostate cancer (ADa)

Trends in prostate cancer incidence since the early 1990s have been subject to over-diagnosis (the detection of latent cancer that would never have been diagnosed in the absence of screening) because of the rapid dissemination of the PSA test.36 The projections of period analysis from Nordpred seem unlikely. Therefore, an age-specific trend power-5 model based on yearly data was fitted to a minimum of 8 years of observations from 1994 to 2007 for projections of prostate cancer incidence in the first 5 (2008–2012) or 10 (2008–2017) future years: Rap = (Aa + Da·p)5, where Da is the slope parameter in age group a, which takes the differentiation in trend from different age groups into consideration. This model also allowed for the ‘‘spike’’ value in the year 2001. Another peak year was in 1993, which was excluded from the modelling.

2.2.1.2 Comparison of models

We fitted the projection models described above to observed incidence counts in 1972–1991 and used them to estimate average annual number of cancer cases for the 5-year periods in 1992–2011. Projections were made for males and females, by age group, for the Canadian provinces and at the national level, for the cancer types shown in Table 2.1. Quebec was excluded from this analysis because of data quality issues prior to 1983.37,38

Given that prostate cancer accounts for nearly one-third of all new cancer cases in males in Canada, the effect of PSA screening is also clearly seen in the incidence of ‘‘all cancers combined’’ in males. The model comparisons were therefore considered with and without prostate cancer and ‘‘all cancers combined’’ for males when appropriate.

We compared projected average annual numbers of cancer cases with observed values. Median absolute relative difference between projected and observed values, |projected–observed|/observed, was calculated to examine each model's overall tendency to over- or underestimate the actual number of cancer cases. The absolute difference was used when comparing for rare cancers. We compared median prediction errors for each model for combinations of cancer type, geographical area and sex by length of projection. The comparisons considered only combinations for which the models produced projections. We used Friedman's test39 to test for statistical difference in medians between different projection models. In addition to considering prediction error across all cancers, we separately compared model performance for each cancer type, across the geographical areas and sexes.

2.2.1.3 Projection validation and adjustment

The model selection was performed by assessing the models and integrating these model comparison results with those from other published studies. However, a model created on cohorts in early periods may give inaccurate predictions when applied to contemporary cohorts. Owing to limitations in the availability of different long-term datasets used for validating the selected models, we examined the projections from the selected models using our knowledge of data quality, trends in cancer rates in different regions, risk factors or interventions to ensure the estimates are appropriate. When the estimated trends seemed unlikely, we used such knowledge to adjust the extrapolation methods of the fitted models, or used Bayesian simulations instead of the generalized linear models. Such modifications were applied in the following situations: all cancers combined in males in Prince Edward Island, Saskatchewan and Alberta, and in females in Ontario, Manitoba and Alberta; female non-Hodgkin lymphoma in New Brunswick; multiple myeloma in males in the Atlantic region and New Brunswick, and in females in Ontario and British Columbia; and thyroid cancer in the provinces except Manitoba, Saskatchewan and British Columbia.

2.2.1.4 Selected models by cancer category

We used the following projection methods in this monograph.

Common cancers (average annual count over the latest 5 observation years for a national or regional series, N > 50): NP_ADPC model with varied ‘‘recent’’ and ‘‘drift’’ values. One exception is that B_APC was applied to multiple myeloma in males in the Atlantic region as the projections from NP_ADPC seem questionable.

Less common cancers (10 <N ≤ 50): NP_ADPC or NP_ADP model (based on the significance of the cohort effect and comparison with AVG results) with varied ‘‘recent’’ and ‘‘drift’’ values. The simple age-effect only AVG model has been proven to be the best approach for rare cancers in our model evaluation and other studies27 and has been used in recent reports.35 With this, we adopted either NP_ADPC or NP_ADP, from which the projections were closer to the AVG results, instead of basing them solely on linear extrapolation of the 5-year average rate into the future. One exception is that B_APC was applied to multiple myeloma in males in New Brunswick.

Rare cancers (N ≤ 10): NP_ADPC, NP_ADP, B_APC, B_AP or SD model, whichever projections were closer to the AVG results.

-

Prostate cancer: ADa + AVG, defined as

using ADa to project for the first 5 future years, and then

using the age-specific average rates of the predicted 5-year data to estimate counts for the second to fifth 5-year periods.

‘‘All cancers’’ for males: The estimates of incidence counts were computed as the sum of the estimates for prostate cancer and for all cancers excluding prostate, as estimated by NP_ADPC modelling.

Tables 2.3 shows the selected projection models for rare cancers or in small areas by cancer type, sex and geographical area.

TABLE 2.3.

Projection models for rare cancers or in small areas by cancer type, sex and geographical area

| Cause | Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B_APa | B_APCa | SDa | NP_ADPa | |

| Oral | PE/F, TC/M+F | MB/F | ||

| Esophagus | TC/M, NL/F | PE+TC/F | NS/F | |

| Stomach | PE/M | TC/F | PE/F, TC/M | NB/F |

| Colorectal | PE/F | TC/M+F | ||

| Liver | NS/F, TC/M | PE+NL/M+F, NB+SK+TC/F | MB+SK/M, AT/M+F | |

| Pancreas | TC/M+F | PE/M+F | NL/F | |

| Larynx | PE/F, TC/M | PE/M, NS+NB+MB+SK/F | NL+TC/F | AT/F |

| Melanoma | TC/M+F | |||

| Breast | TC/F | |||

| Cervix | PE/F, TC/F | MB/F | ||

| Body of uterus | TC/F | |||

| Ovary | TC/F | PE/F | ||

| Testis | PE+NL+TC/M | NS+NB+MB/M | ||

| Kidney | PE/F | TC/F | TC/M | PE/M, NL/M+F |

| Bladder | PE+TC/F, TC/M | NL/F | ||

| Central nervous system | PE+TC/M+F | NS/M, NB+NL+SK/F, MB/M+F | ||

| Thyroid | PE/M | PE/F | TC/M+F | NS/M, SK/F |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | NB/F | PE+NL+TC/M+F | NB+AB+AT/M, BC/F, NS+MB+SK/M+F | |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | PE/F, TC/M+F | PE/M | NL/M+F, AT+NS+NB/F | |

| Multiple myeloma | AT+NB/M, PE/F | PE/M, NL/F, TC/M+F | NS+MB+SK/M+F, NL/M | |

| Leukemia | PE/M, TC/F | PE/F | TC/M | NL/M+F |

| All other cancers | PE/F | TC/F | ||

Abbreviations: AB, Alberta; AT, All Atlantic provinces together (PE, NS, NB and NL); BC, British Columbia; MB, Manitoba; NB, New Brunswick; NL, Newfoundland and Labrador; NS, Nova Scotia; PE, Prince Edward Island; SK, Saskatchewan; TC, All Territories (Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut).

Note: The abbreviation before ‘/’ refers to the province or region; ‘M’ or ‘F’ after ‘/’ refers to males or females. For example, PE+TC/M+F in the ‘SD’ model was used for both males and females in PE and TC for central nervous system cancers.

See Methods for the definitions.

2.2.2 Other analysis methods

2.2.2.1 Joinpoint regression analysis

We assessed observed trends (1986–2007) using joinpoint regression,40,41 which involves fitting a series of joined straight lines on a logarithmic scale to the trends in ASIRs. The trends in incidence are reflected by the annual percent change. The models incorporated estimated standard errors of the ASIRs. The tests of significance used a Monte Carlo Permutation method. The estimated slope from this model was then transformed back to represent an annual percentage increase or decrease in the rate.

A minimum of 5 years of data before and after a changepoint in years in which the annual percent change changed significantly was required for a new trend to be identified. Thus, the most recent possible changepoint is 2003. In Figures 3.1 and 3.2, if no changepoint was detected from 1998 to 2007, then the annual percent change was estimated by fitting a model within this time period. If a changepoint was detected within this decade, then the annual percent change was estimated from the trend in the last segment. Both the changepoint year and the annual percent change for the years beyond the changepoint are indicated in these two figures.

FIGURE 3.1. Annual percent changes in age-standardized incidence rates (1998–2007) for selected cancers, males, Canada.

Note: The error bars refer to 95% confidence intervals.

FIGURE 3.2. Annual percent changes in age-standardized incidence rates (1998–2007) for selected cancers, females, Canada.

Note: The error bars refer to 95% confidence intervals.

2.2.2.2 Contribution of change in cancer risk, population growth and population age structure to incidence trend

Figure 3.4 shows the relative contributions of changes in the total numbers of new cases that can be attributed to changes in cancer risk, population growth, and aging of the population. The series were defined as follows (the annual ASIR was calculated by using the average annual population distribution in 1983–1987 for males or females as the standard weights):1

FIGURE 3.4. Trends in average annual new cases for all cancers and ages, attributed to changes in cancer risk, population growth, and aging population, Canada, 1983–2032.

The baseline (red reference line) represents the observed average annual number of new cancer cases during 1983–1987 for males or females.

The lowest black line represents the average annual number of new cancer cases that would have occurred in each period if the average annual population size and composition had remained the same as they were in 1983–1987. Thus, it measures the impact of changes in cancer risk. This series was computed by multiplying the average annual population in 1983–1987 by the ASIR.

The middle black line represents the average annual number of new cases that would have occurred if the age distribution of the average annual population had remained the same as it was in 1983–1987, measuring the impact of changes in risk and population growth. This series was computed by multiplying the average annual population by the ASIR.

The top line represents the total average annual number of new cases that actually occurred (projected estimates as of 2008) in each period for males or females, reflecting the combined impact of changes in cancer risk, and population growing and aging.

2.3 Presentation of results

In this monograph, while the figures display longer-termtimetrendsinASIRsofeachcancer for broader areas, the tables show cancer incidencefrequenciesandratesinallprovinces andterritoriesfromthelastobservationperiod (2003–2007) onward. The numbers of cases shown in the tables and figures are average annualnumbers.AlltheASIRswerecalculated per100 000person-years.

For each type of cancer, the historical and projected ASIRs are shown in figures to illustrate their time trends and differences between (1) sexes and age groups (<45, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, 75–84, 85+), and (2) regions (British Columbia, the Prairies, Ontario, Quebec, the Atlantic region and Canada as a whole). The trends for the North are not shown in the figures because of small numbers. Number of cases in Figure 3.8–3.10 was rounded to the nearest 100.

FIGURE 3.8. Most common newly diagnosed cancers in Canada, 1983–1987.

a Total of rounded numbers may not equal rounded total number;

b CNS refers to central nervous system cancer;

c NHL refers to non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

FIGURE 3.10. Projected most common newly diagnosed cancers in Canada, 2028–2032.

a Total of rounded numbers may not equal rounded total number;

b CNS refers to central nervous system cancer;

c NHL refers to non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Tables for males and females give the observed (2003–2007) and projected average annual number of cases and ASIRs by the 10-year age group and province/territories combined. Number of cases was rounded to the nearest 5. The numbers were rounded separately, so it is possible that the totals in the tables do not add up.

Chapter 3 presents the overview of historical and projected trends for all cancers combined, whereas Chapter 4 breaks down such information by cancer sites.

The cancers are ordered by the ICD-O-3 codes.

Chapter 3: Overview of Observed and Projected Status of All Cancers

Recent changes in observed cancer incidence rates

The annual percent change in cancer-specific ASIRs in males and females in the last observed decade (1998–2007) shows varying trends by cancer site (Figures 3.1 and 3.2). Between 1998 and 2007, the overall incidence rate increased significantly in females by 0.3% per year. Statistically significant increases of 2% or more per year occurred for liver cancer in both males (3.6%) and females (2.4%), kidney cancer in males (2.6% since 2003) and thyroid in both males (6.8%) and females (6.9% since 2002). Significant annual decreases of 2% or more occurred in larynx cancer for both males (3.8%) and females (3.4%) and in stomach cancer in males (2.0%). The possible explanations for the observed trends can be found in the corresponding section of Chapter 4.

Overall (historic and projected) trends

Figure 3.3 illustrates the average annual number of new cases and ASIRs for all cancers combined for 1983–2032, with projections as of the year 2008. Even though the observed ASIRs for all cancers combined stabilized, the number of new cancer cases continues to increase as the Canadian population grows and ages. The ASIRs in males decreased after increasing until 1993–1997. This pattern mirrors a similar trend in the incidence of prostate cancer, the leading cancer in males. The decrease also represents the decrease in lung cancer rates in men aged 65 or older. In females, the cancer incidence rate increased slightly over the observation horizon. The increase reflects the rise in rates in cancers of lung (in women aged 65 or older), uterus, thyroid, breast (in females aged under 45), leukemia, kidney, and melanoma.

FIGURE 3.3. Average annual new cases and age-standardized incidence rates (ASIRs) for all cancers, Canada, 1983–2032.

Note: The error bars refer to 95% confidence intervals.

All cancers combined excludes non-mela-noma skin cancer. In Canada, non-mela-noma skin cancer accounts for about 30% of all new cancer cases.

Tables 3.1 to 3.4 show historic and projected numbers of new cancer cases and ASIRs by sex, period, age group and geographical region. From 2003–2007 to 2028–2032, the ASIRs for all cancers in Canada are projected to decrease in males by 5%, from 464.8 to 443.2 per 100 000, and to increase in females by 4%, from 358.3 to 371.0 per 100 000. The annual number of cases is projected to increase by 84% (from 80 810 to 148 370) in males and by 74% (from 74 165 to 128 830) in females.

TABLE 3.1.

Observed (2003–2007) and projected average annual new cases by age and province/territories combined (TC), all cancers, males, Canada, 2003–2032

| Period | Age | New cases | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA | BC | AB | SK | MB | ON | QC | NB | NS | PE | NL | TC | ||

| 2003–07 | <45 | 4720 | 560 | 495 | 125 | 155 | 1950 | 1080 | 100 | 155 | 20 | 65 | 15 |

| 45–54 | 8265 | 970 | 850 | 230 | 280 | 3230 | 2000 | 225 | 285 | 40 | 140 | 20 | |

| 55–64 | 18 860 | 2280 | 1655 | 540 | 600 | 7145 | 4870 | 545 | 715 | 110 | 360 | 40 | |

| 65–74 | 24 570 | 3090 | 2090 | 840 | 825 | 9375 | 6135 | 710 | 905 | 140 | 420 | 40 | |

| 75–84 | 19 040 | 2600 | 1555 | 705 | 725 | 6985 | 4925 | 500 | 670 | 95 | 260 | 20 | |

| 85+ | 5350 | 785 | 440 | 235 | 240 | 1750 | 1470 | 155 | 195 | 30 | 55 | 5 | |

| Total | 80 810 | 10 280 | 7090 | 2675 | 2825 | 30 430 | 20 480 | 2235 | 2925 | 440 | 1295 | 140 | |

| 2008–12 | <45 | 4810 | 555 | 555 | 125 | 135 | 1940 | 1060 | 100 | 140 | 20 | 65 | 10 |

| 45–54 | 9490 | 1015 | 1015 | 255 | 280 | 3865 | 2180 | 235 | 320 | 50 | 140 | 25 | |

| 55–64 | 23 235 | 2665 | 2120 | 695 | 680 | 9090 | 5640 | 710 | 875 | 135 | 455 | 55 | |

| 65–74 | 27 390 | 3435 | 2160 | 870 | 830 | 10 455 | 6875 | 850 | 1060 | 160 | 495 | 50 | |

| 75–84 | 20 520 | 2775 | 1680 | 675 | 660 | 7435 | 5520 | 545 | 705 | 110 | 275 | 25 | |

| 85+ | 7065 | 1050 | 560 | 245 | 265 | 2385 | 2055 | 180 | 220 | 30 | 55 | 5 | |

| Total | 92 515 | 11 495 | 8085 | 2860 | 2850 | 35 170 | 23 330 | 2620 | 3320 | 510 | 1490 | 170 | |

| 2013–17 | <45 | 5085 | 590 | 590 | 120 | 130 | 2030 | 1110 | 100 | 140 | 20 | 65 | 10 |

| 45–54 | 9505 | 1000 | 1035 | 245 | 260 | 3965 | 2085 | 230 | 315 | 50 | 145 | 25 | |

| 55–64 | 26 330 | 2985 | 2610 | 795 | 750 | 10 455 | 6140 | 760 | 910 | 150 | 470 | 60 | |

| 65–74 | 33 695 | 4245 | 2810 | 1005 | 990 | 12 860 | 8175 | 1070 | 1320 | 200 | 630 | 75 | |

| 75–84 | 22 080 | 2955 | 1855 | 680 | 660 | 7910 | 5935 | 620 | 780 | 125 | 310 | 35 | |

| 85+ | 8940 | 1265 | 750 | 265 | 295 | 3080 | 2670 | 205 | 250 | 35 | 65 | 5 | |

| Total | 105 630 | 13 040 | 9645 | 3115 | 3085 | 40 300 | 26 115 | 2985 | 3715 | 580 | 1685 | 210 | |

| 2018–22 | <45 | 5420 | 650 | 605 | 125 | 130 | 2170 | 1155 | 105 | 145 | 20 | 70 | 10 |

| 45–54 | 8895 | 925 | 1015 | 220 | 235 | 3735 | 1890 | 215 | 280 | 45 | 130 | 20 | |

| 55–64 | 28 975 | 3235 | 2945 | 845 | 800 | 11 885 | 6500 | 780 | 970 | 170 | 465 | 65 | |

| 65–74 | 40 245 | 5110 | 3665 | 1220 | 1165 | 15 510 | 9295 | 1250 | 1505 | 235 | 735 | 95 | |

| 75–84 | 25 830 | 3445 | 2220 | 740 | 750 | 9150 | 6925 | 760 | 950 | 145 | 385 | 50 | |

| 85+ | 10 370 | 1450 | 915 | 285 | 305 | 3530 | 3155 | 240 | 280 | 45 | 80 | 10 | |

| Total | 119 730 | 14 810 | 11 360 | 3440 | 3385 | 45 985 | 28 915 | 3355 | 4130 | 655 | 1870 | 250 | |

| 2023–27 | <45 | 5765 | 710 | 620 | 130 | 130 | 2340 | 1190 | 110 | 150 | 20 | 70 | 10 |

| 45–54 | 9065 | 950 | 1065 | 215 | 240 | 3785 | 1940 | 215 | 275 | 40 | 125 | 20 | |

| 55–64 | 28 925 | 3245 | 2970 | 815 | 775 | 12 195 | 6210 | 750 | 950 | 170 | 460 | 60 | |

| 65–74 | 46 165 | 5815 | 4515 | 1415 | 1325 | 18 160 | 10 280 | 1350 | 1615 | 260 | 770 | 110 | |

| 75–84 | 32 640 | 4395 | 2960 | 895 | 945 | 11 625 | 8475 | 975 | 1220 | 180 | 505 | 70 | |

| 85+ | 11 725 | 1615 | 1055 | 305 | 335 | 3995 | 3570 | 280 | 330 | 50 | 95 | 10 | |

| Total | 134 285 | 16 725 | 13 185 | 3780 | 3750 | 52 105 | 31 670 | 3685 | 4545 | 725 | 2025 | 280 | |

| 2028–32 | <45 | 5990 | 745 | 620 | 135 | 125 | 2475 | 1220 | 115 | 150 | 15 | 70 | 10 |

| 45–54 | 9780 | 1070 | 1135 | 235 | 260 | 4065 | 2060 | 215 | 295 | 45 | 135 | 15 | |

| 55–64 | 27 300 | 3075 | 2930 | 750 | 715 | 11 615 | 5685 | 700 | 860 | 150 | 420 | 55 | |

| 65–74 | 51 070 | 6370 | 5090 | 1510 | 1440 | 20 765 | 10 950 | 1405 | 1745 | 295 | 780 | 115 | |

| 75–84 | 39 720 | 5365 | 3930 | 1115 | 1140 | 14 280 | 9880 | 1155 | 1415 | 215 | 600 | 90 | |

| 85+ | 14 510 | 2010 | 1335 | 350 | 400 | 4855 | 4475 | 365 | 425 | 65 | 130 | 15 | |

| Total | 148 370 | 18 635 | 15 040 | 4090 | 4085 | 58 055 | 34 275 | 3955 | 4890 | 785 | 2140 | 305 | |

Abbreviations: AB, Alberta; BC, British Columbia; CA, Canada; MB, Manitoba; NB, New Brunswick; NL, Newfoundland and Labrador; NS, Nova Scotia; ON, Ontario; PE, Prince Edward Island; QC, Quebec; SK, Saskatchewan; TC, All Territories (Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut).

Note: Totals may not add up due to rounding.

TABLE 3.4.

Observed (2003–2007) and projected age-standardized incidence rates (ASIRs) by age and province/territories combined (TC), all cancers, females, Canada, 2003–2032

| Period | Age | ASIRs | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA | BC | AB | SK | MB | ON | QC | NB | NS | PE | NL | TC | ||

| 2003–07 | <45 | 77.6 | 67.3 | 76.0 | 65.9 | 68.9 | 86.2 | 73.4 | 74.7 | 77.5 | 68.5 | 67.6 | 60.3 |

| 45–54 | 459.8 | 405.1 | 442.7 | 424.9 | 456.7 | 477.2 | 479.8 | 454.7 | 454.1 | 423.5 | 416.5 | 435.8 | |

| 55–64 | 875.8 | 779.9 | 865.6 | 901.5 | 908.0 | 876.9 | 914.4 | 886.4 | 923.9 | 902.5 | 848.4 | 1003.9 | |

| 65–74 | 1372.1 | 1283.4 | 1396.0 | 1386.5 | 1363.1 | 1362.6 | 1405.8 | 1391.2 | 1515.1 | 1583.5 | 1277.7 | 1680.4 | |

| 75–84 | 1828.8 | 1737.8 | 1805.9 | 1757.9 | 1867.6 | 1758.8 | 1971.2 | 1907.9 | 2085.6 | 1956.8 | 1569.3 | 2078.9 | |

| 85+ | 2023.8 | 1869.5 | 1978.6 | 1772.8 | 1919.8 | 1894.5 | 2453.6 | 1982.7 | 2097.8 | 1973.2 | 1081.8 | 1834.0 | |

| Total | 358.3 | 326.1 | 354.8 | 344.6 | 354.4 | 361.7 | 372.7 | 360.4 | 381.4 | 368.9 | 319.0 | 382.9 | |

| 2008–12 | <45 | 79.4 | 64.2 | 77.6 | 67.1 | 69.6 | 90.6 | 74.0 | 79.3 | 72.9 | 71.3 | 71.2 | 57.1 |

| 45–54 | 465.1 | 389.1 | 445.4 | 415.8 | 432.8 | 493.0 | 484.2 | 454.3 | 459.2 | 407.4 | 459.5 | 414.1 | |

| 55–64 | 880.0 | 747.8 | 864.4 | 869.6 | 888.1 | 889.5 | 947.0 | 877.0 | 878.7 | 830.8 | 848.1 | 886.4 | |

| 65–74 | 1397.4 | 1250.5 | 1437.2 | 1447.9 | 1444.3 | 1384.0 | 1458.9 | 1445.6 | 1470.6 | 1530.6 | 1408.4 | 1718.1 | |

| 75–84 | 1838.1 | 1668.4 | 1892.9 | 1812.9 | 1899.0 | 1781.7 | 2000.7 | 1920.2 | 2079.2 | 1980.7 | 1605.8 | 2509.1 | |

| 85+ | 2042.4 | 1937.0 | 2094.1 | 1856.0 | 1992.9 | 1924.8 | 2419.9 | 1990.6 | 2126.3 | 1846.7 | 1145.8 | 1890.5 | |

| Total | 362.7 | 315.5 | 363.2 | 348.7 | 358.0 | 370.2 | 380.7 | 367.0 | 372.0 | 358.9 | 337.0 | 386.7 | |

| 2013–17 | <45 | 81.1 | 62.3 | 78.4 | 69.9 | 71.6 | 94.5 | 74.9 | 83.0 | 72.4 | 75.3 | 74.9 | 54.4 |

| 45–54 | 476.5 | 387.4 | 464.0 | 397.7 | 428.8 | 521.5 | 482.0 | 461.4 | 447.9 | 392.3 | 458.6 | 404.5 | |

| 55–64 | 875.1 | 711.8 | 860.9 | 857.5 | 879.2 | 896.0 | 947.3 | 863.2 | 848.7 | 819.6 | 880.9 | 892.3 | |

| 65–74 | 1402.8 | 1217.3 | 1431.1 | 1435.6 | 1423.2 | 1395.4 | 1500.4 | 1446.6 | 1431.8 | 1396.2 | 1450.0 | 1556.5 | |

| 75–84 | 1862.5 | 1650.6 | 1965.0 | 1903.5 | 1963.8 | 1800.5 | 2045.9 | 1963.9 | 2042.2 | 2056.7 | 1712.4 | 2623.6 | |

| 85+ | 2059.0 | 1845.4 | 2165.1 | 1944.2 | 2011.0 | 1933.9 | 2480.6 | 2062.5 | 2253.8 | 1990.6 | 1264.3 | 2115.6 | |

| Total | 366.1 | 307.0 | 368.4 | 351.0 | 359.3 | 378.0 | 386.2 | 371.4 | 365.2 | 354.0 | 350.2 | 379.7 | |

| 2018–22 | <45 | 80.9 | 61.2 | 79.4 | 70.7 | 74.3 | 95.9 | 73.0 | 81.5 | 69.4 | 73.9 | 76.7 | 50.4 |

| 45–54 | 494.7 | 386.2 | 473.2 | 401.4 | 431.9 | 557.2 | 489.0 | 496.7 | 451.8 | 411.0 | 462.2 | 412.6 | |

| 55–64 | 883.4 | 701.1 | 866.3 | 850.7 | 865.4 | 919.4 | 947.2 | 888.2 | 850.5 | 791.0 | 899.4 | 875.5 | |

| 65–74 | 1387.1 | 1168.3 | 1409.8 | 1396.5 | 1386.3 | 1390.1 | 1512.8 | 1401.1 | 1388.5 | 1340.6 | 1447.6 | 1564.1 | |

| 75–84 | 1881.5 | 1640.5 | 2005.3 | 1960.3 | 1982.8 | 1810.6 | 2087.7 | 1984.7 | 2025.1 | 2089.3 | 1827.0 | 2560.5 | |

| 85+ | 2061.9 | 1821.2 | 2209.9 | 1961.0 | 2090.4 | 1938.0 | 2500.3 | 2084.3 | 2196.0 | 1982.0 | 1337.4 | 2302.1 | |

| Total | 368.3 | 301.3 | 370.9 | 350.8 | 359.3 | 384.9 | 388.2 | 374.2 | 359.4 | 349.9 | 358.0 | 376.5 | |

| 2023–27 | <45 | 80.5 | 61.5 | 78.7 | 71.2 | 74.5 | 96.9 | 71.1 | 82.8 | 64.9 | 73.3 | 80.4 | 49.2 |

| 45–54 | 503.5 | 379.6 | 478.4 | 419.1 | 442.0 | 573.2 | 491.3 | 514.4 | 478.8 | 448.5 | 459.7 | 411.6 | |

| 55–64 | 897.5 | 708.1 | 889.7 | 817.0 | 854.4 | 957.5 | 934.6 | 896.3 | 846.0 | 780.0 | 880.7 | 890.9 | |

| 65–74 | 1376.2 | 1134.0 | 1394.3 | 1381.2 | 1371.9 | 1392.5 | 1501.1 | 1383.3 | 1365.3 | 1332.4 | 1472.4 | 1618.6 | |

| 75–84 | 1878.9 | 1616.7 | 1979.2 | 1938.3 | 1946.1 | 1812.1 | 2126.5 | 1977.2 | 1997.4 | 1923.5 | 1831.2 | 2407.2 | |

| 85+ | 2092.4 | 1833.8 | 2294.3 | 2104.9 | 2144.1 | 1950.6 | 2550.1 | 2135.5 | 2204.3 | 2148.6 | 1405.5 | 2445.5 | |

| Total | 369.7 | 298.3 | 371.9 | 349.8 | 357.8 | 391.0 | 387.1 | 376.8 | 356.4 | 347.8 | 361.2 | 376.6 | |

| 2028–32 | <45 | 79.3 | 60.6 | 78.3 | 69.7 | 71.4 | 96.4 | 69.3 | 86.6 | 64.9 | 72.6 | 84.4 | 48.0 |

| 45–54 | 504.3 | 382.7 | 485.0 | 429.0 | 478.0 | 582.6 | 477.6 | 485.1 | 451.0 | 444.3 | 452.0 | 390.9 | |

| 55–64 | 924.9 | 712.0 | 903.0 | 820.6 | 859.0 | 1011.6 | 940.4 | 950.5 | 855.6 | 814.0 | 876.3 | 921.1 | |

| 65–74 | 1385.3 | 1127.1 | 1399.5 | 1365.6 | 1345.9 | 1421.1 | 1493.7 | 1415.0 | 1380.4 | 1308.4 | 1483.6 | 1620.8 | |

| 75–84 | 1852.7 | 1562.0 | 1946.5 | 1884.9 | 1896.6 | 1797.0 | 2129.0 | 1906.7 | 1951.7 | 1895.8 | 1819.4 | 2483.2 | |

| 85+ | 2099.2 | 1825.4 | 2300.0 | 2107.2 | 2136.8 | 1948.8 | 2582.1 | 2131.0 | 2190.7 | 2121.5 | 1498.1 | 2307.0 | |

| Total | 371.0 | 295.8 | 372.7 | 347.2 | 356.3 | 397.6 | 384.8 | 380.5 | 353.5 | 346.9 | 364.1 | 377.6 | |

Abbreviations: AB, Alberta; BC, British Columbia; CA, Canada; MB, Manitoba; NB, New Brunswick; NL, Newfoundland and Labrador; NS, Nova Scotia; ON, Ontario; PE, Prince Edward Island; QC, Quebec; SK, Saskatchewan; TC, All Territories (Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut).

TABLE 3.2.

Observed (2003–2007) and projected average annual new cases by age and province/territories combined (TC), all cancers, females, Canada, 2003–2032

| Period | Age | New cases | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA | BC | AB | SK | MB | ON | QC | NB | NS | PE | NL | TC | ||

| 2003–07 | <45 | 7940 | 895 | 820 | 190 | 240 | 3505 | 1725 | 175 | 230 | 30 | 110 | 20 |

| 45–54 | 11 490 | 1370 | 1095 | 310 | 395 | 4490 | 2950 | 280 | 345 | 45 | 185 | 30 | |

| 55–64 | 15 485 | 1870 | 1305 | 440 | 550 | 5810 | 4195 | 400 | 530 | 75 | 275 | 35 | |

| 65–74 | 16 325 | 2025 | 1350 | 515 | 570 | 6245 | 4280 | 405 | 570 | 85 | 250 | 25 | |

| 75–84 | 15 975 | 2035 | 1225 | 550 | 655 | 5960 | 4280 | 420 | 565 | 75 | 200 | 15 | |

| 85+ | 6945 | 900 | 540 | 280 | 310 | 2380 | 1990 | 190 | 265 | 35 | 55 | 5 | |

| Total | 74 165 | 9100 | 6335 | 2280 | 2715 | 28 385 | 19 425 | 1870 | 2505 | 345 | 1075 | 130 | |

| 2008–12 | <45 | 7900 | 850 | 875 | 185 | 235 | 3605 | 1630 | 165 | 195 | 25 | 105 | 20 |

| 45–54 | 12 670 | 1430 | 1245 | 325 | 400 | 5195 | 3125 | 290 | 370 | 50 | 205 | 30 | |

| 55–64 | 18 805 | 2235 | 1690 | 520 | 645 | 7140 | 5030 | 480 | 595 | 85 | 335 | 45 | |

| 65–74 | 18 915 | 2315 | 1600 | 565 | 655 | 7135 | 5075 | 485 | 640 | 95 | 330 | 35 | |

| 75–84 | 16 755 | 2025 | 1390 | 545 | 630 | 6310 | 4635 | 420 | 575 | 80 | 215 | 20 | |

| 85+ | 8885 | 1185 | 730 | 315 | 375 | 3170 | 2530 | 225 | 305 | 40 | 65 | 5 | |

| Total | 83 930 | 10 040 | 7525 | 2460 | 2945 | 32 560 | 22 020 | 2070 | 2675 | 375 | 1255 | 160 | |

| 2013–17 | <45 | 8280 | 860 | 935 | 200 | 255 | 3865 | 1670 | 170 | 190 | 30 | 100 | 20 |

| 45–54 | 12 770 | 1425 | 1290 | 290 | 385 | 5595 | 2910 | 275 | 340 | 45 | 195 | 30 | |

| 55–64 | 21 300 | 2425 | 2045 | 600 | 720 | 8270 | 5560 | 515 | 635 | 90 | 370 | 55 | |

| 65–74 | 23 685 | 2870 | 2075 | 660 | 795 | 8915 | 6405 | 625 | 785 | 115 | 445 | 50 | |

| 75–84 | 17 955 | 2150 | 1575 | 560 | 650 | 6745 | 4965 | 460 | 610 | 90 | 255 | 30 | |

| 85+ | 10 500 | 1310 | 915 | 355 | 420 | 3770 | 3125 | 260 | 345 | 50 | 85 | 5 | |

| Total | 94 495 | 11 035 | 8830 | 2660 | 3220 | 37 160 | 24 635 | 2305 | 2900 | 420 | 1450 | 195 | |

| 2018–22 | <45 | 8685 | 905 | 995 | 210 | 280 | 4130 | 1715 | 165 | 180 | 30 | 100 | 15 |

| 45–54 | 12 365 | 1370 | 1275 | 260 | 360 | 5685 | 2610 | 260 | 300 | 40 | 175 | 30 | |

| 55–64 | 23 405 | 2590 | 2300 | 635 | 760 | 9510 | 5820 | 550 | 675 | 95 | 380 | 60 | |

| 65–74 | 28 330 | 3400 | 2640 | 790 | 940 | 10 780 | 7505 | 735 | 900 | 130 | 535 | 70 | |

| 75–84 | 21 170 | 2545 | 1915 | 620 | 735 | 7820 | 5945 | 550 | 720 | 110 | 340 | 45 | |

| 85+ | 11 635 | 1415 | 1075 | 365 | 450 | 4190 | 3530 | 280 | 360 | 55 | 100 | 10 | |

| Total | 105 590 | 12 230 | 10 200 | 2875 | 3525 | 42 110 | 27 125 | 2545 | 3140 | 465 | 1630 | 235 | |

| 2023–27 | <45 | 9035 | 975 | 1025 | 220 | 295 | 4425 | 1695 | 165 | 175 | 30 | 100 | 15 |

| 45–54 | 12 750 | 1380 | 1340 | 280 | 375 | 5890 | 2665 | 265 | 305 | 45 | 160 | 30 | |

| 55–64 | 23 410 | 2625 | 2350 | 570 | 735 | 10 080 | 5360 | 525 | 635 | 90 | 360 | 60 | |

| 65–74 | 32 100 | 3775 | 3165 | 915 | 1050 | 12 430 | 8270 | 800 | 985 | 145 | 585 | 90 | |

| 75–84 | 26 800 | 3245 | 2495 | 740 | 905 | 9860 | 7535 | 715 | 910 | 135 | 455 | 65 | |

| 85+ | 13 085 | 1600 | 1270 | 400 | 480 | 4675 | 3975 | 320 | 405 | 70 | 120 | 15 | |

| Total | 117 185 | 13 600 | 11 645 | 3125 | 3845 | 47 365 | 29 500 | 2790 | 3415 | 515 | 1780 | 280 | |

| 2028–32 | <45 | 9110 | 995 | 1020 | 215 | 295 | 4580 | 1655 | 175 | 175 | 30 | 105 | 15 |

| 45–54 | 13 610 | 1505 | 1475 | 310 | 435 | 6340 | 2785 | 250 | 295 | 45 | 150 | 25 | |

| 55–64 | 22 685 | 2560 | 2310 | 520 | 695 | 10 190 | 4825 | 500 | 570 | 80 | 325 | 60 | |

| 65–74 | 35 275 | 4085 | 3550 | 970 | 1115 | 14 235 | 8655 | 855 | 1065 | 155 | 605 | 100 | |

| 75–84 | 32 250 | 3900 | 3180 | 900 | 1080 | 11 955 | 8875 | 845 | 1065 | 160 | 550 | 95 | |

| 85+ | 15 895 | 1950 | 1570 | 445 | 555 | 5590 | 4925 | 390 | 500 | 85 | 170 | 25 | |

| Total | 128 830 | 14 995 | 13 105 | 3360 | 4170 | 52 890 | 31 720 | 3015 | 3670 | 555 | 1900 | 320 | |

Abbreviations: AB, Alberta; BC, British Columbia; CA, Canada; MB, Manitoba; NB, New Brunswick; NL, Newfoundland and Labrador; NS, Nova Scotia; ON, Ontario; PE, Prince Edward Island; QC, Quebec; SK, Saskatchewan; TC, All Territories (Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut).

Note: Totals may not add up due to rounding.

TABLE 3.3.

Observed (2003–2007) and projected age-standardized incidence rates (ASIRs) by age and povince/territories combined (TC), all cancers, males, Canada, 2003–2032

| Period | Age | ASIRs | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA | BC | AB | SK | MB | ON | QC | NB | NS | PE | NL | TC | ||

| 2003–07 | <45 | 46.0 | 43.1 | 43.4 | 42.8 | 42.4 | 48.3 | 45.6 | 44.4 | 54.1 | 53.3 | 40.8 | 35.0 |

| 45–54 | 331.4 | 291.0 | 330.1 | 307.3 | 316.8 | 346.2 | 327.3 | 368.3 | 381.3 | 393.1 | 319.7 | 259.3 | |

| 55–64 | 1109.9 | 975.6 | 1099.4 | 1132.0 | 1019.7 | 1133.7 | 1120.4 | 1239.1 | 1295.8 | 1369.8 | 1124.0 | 932.9 | |

| 65–74 | 2287.3 | 2035.9 | 2305.9 | 2453.0 | 2218.9 | 2302.8 | 2297.5 | 2672.0 | 2642.8 | 2782.8 | 2238.1 | 2446.9 | |

| 75–84 | 3068.1 | 2876.7 | 3046.6 | 3012.9 | 2999.1 | 2907.7 | 3404.9 | 3358.1 | 3583.7 | 3517.4 | 2724.6 | 3229.8 | |

| 85+ | 3506.6 | 3246.0 | 3394.8 | 3122.3 | 3355.0 | 3093.5 | 4643.9 | 3735.2 | 3631.1 | 3692.9 | 2367.1 | 2467.3 | |

| Total | 464.8 | 420.2 | 461.3 | 467.3 | 444.3 | 461.1 | 489.3 | 517.7 | 535.7 | 550.6 | 433.8 | 440.2 | |

| 2008–12 | <45 | 47.7 | 42.4 | 45.1 | 42.4 | 37.9 | 49.3 | 46.6 | 47.6 | 54.9 | 49.3 | 47.5 | 31.2 |

| 45–54 | 342.9 | 279.5 | 340.0 | 321.4 | 295.3 | 362.0 | 331.4 | 380.8 | 405.2 | 434.7 | 330.5 | 281.2 | |

| 55–64 | 1129.3 | 929.0 | 1062.6 | 1165.2 | 959.9 | 1190.9 | 1113.7 | 1341.0 | 1347.4 | 1419.7 | 1191.9 | 928.6 | |

| 65–74 | 2208.8 | 1946.8 | 2055.6 | 2394.1 | 2001.2 | 2254.4 | 2185.5 | 2666.1 | 2652.8 | 2729.1 | 2216.4 | 2327.6 | |

| 75–84 | 2942.7 | 2714.5 | 2860.4 | 2867.5 | 2672.3 | 2767.8 | 3280.2 | 3371.6 | 3424.2 | 3519.0 | 2613.7 | 3340.0 | |

| 85+ | 3368.6 | 3176.5 | 3220.2 | 2878.2 | 2999.6 | 2950.5 | 4469.9 | 3416.4 | 3477.7 | 3603.6 | 2139.2 | 3120.6 | |

| Total | 457.6 | 401.9 | 434.8 | 459.7 | 403.5 | 458.7 | 476.0 | 526.9 | 536.7 | 552.1 | 437.7 | 442.0 | |

| 2013–17 | <45 | 49.3 | 43.1 | 45.7 | 41.0 | 35.0 | 50.4 | 48.0 | 50.8 | 56.9 | 48.0 | 51.4 | 30.3 |

| 45–54 | 341.9 | 268.5 | 344.9 | 330.3 | 282.8 | 357.2 | 328.3 | 386.7 | 413.8 | 441.6 | 348.7 | 292.8 | |

| 55–64 | 1120.4 | 919.8 | 1076.3 | 1150.2 | 915.9 | 1183.3 | 1085.6 | 1340.3 | 1296.4 | 1458.8 | 1186.2 | 893.9 | |

| 65–74 | 2157.2 | 1898.1 | 2018.9 | 2309.2 | 1895.1 | 2203.5 | 2104.0 | 2607.6 | 2617.2 | 2651.4 | 2200.5 | 2186.3 | |

| 75–84 | 2867.6 | 2608.8 | 2824.4 | 2879.8 | 2587.1 | 2684.2 | 3159.4 | 3320.8 | 3332.2 | 3382.3 | 2515.8 | 3452.5 | |

| 85+ | 3345.1 | 3061.9 | 3272.9 | 2824.4 | 2935.6 | 2902.9 | 4447.3 | 3397.1 | 3467.1 | 3615.1 | 2135.7 | 3071.7 | |

| Total | 451.4 | 392.1 | 433.7 | 452.5 | 385.4 | 451.3 | 464.1 | 523.7 | 528.8 | 545.3 | 437.3 | 433.5 | |

| 2018–22 | <45 | 50.5 | 44.6 | 45.4 | 40.6 | 33.3 | 51.5 | 48.5 | 52.0 | 59.0 | 46.4 | 56.1 | 27.4 |

| 45–54 | 346.3 | 260.4 | 350.8 | 330.7 | 273.4 | 361.9 | 334.4 | 409.4 | 422.5 | 421.0 | 361.5 | 301.1 | |

| 55–64 | 1114.2 | 907.9 | 1083.8 | 1145.1 | 900.8 | 1176.9 | 1068.0 | 1332.7 | 1297.5 | 1502.9 | 1168.9 | 884.7 | |

| 65–74 | 2130.2 | 1870.0 | 2026.7 | 2258.2 | 1822.8 | 2190.7 | 2046.5 | 2573.5 | 2538.7 | 2609.4 | 2173.6 | 2126.1 | |

| 75–84 | 2782.1 | 2532.5 | 2759.1 | 2829.2 | 2486.9 | 2600.1 | 3020.4 | 3228.1 | 3286.9 | 3286.9 | 2500.3 | 3213.3 | |

| 85+ | 3277.6 | 2968.9 | 3268.1 | 2849.4 | 2826.1 | 2810.4 | 4351.1 | 3422.5 | 3345.9 | 3625.9 | 2135.2 | 3445.8 | |

| Total | 446.6 | 385.6 | 432.9 | 446.8 | 372.3 | 447.2 | 453.7 | 520.9 | 523.1 | 539.6 | 438.0 | 422.8 | |

| 2023–27 | <45 | 51.8 | 46.0 | 45.7 | 41.4 | 31.7 | 52.7 | 49.7 | 54.2 | 59.3 | 43.5 | 58.9 | 27.8 |

| 45–54 | 354.3 | 264.7 | 354.7 | 315.8 | 273.9 | 373.8 | 340.6 | 423.8 | 445.9 | 424.3 | 380.5 | 275.7 | |

| 55–64 | 1112.2 | 889.6 | 1094.3 | 1169.0 | 893.6 | 1173.6 | 1061.8 | 1338.3 | 1322.3 | 1510.5 | 1204.6 | 902.2 | |

| 65–74 | 2115.6 | 1862.3 | 2045.3 | 2238.9 | 1788.2 | 2190.6 | 2000.2 | 2559.6 | 2468.9 | 2653.8 | 2143.9 | 2033.8 | |

| 75–84 | 2715.7 | 2477.3 | 2707.2 | 2724.7 | 2401.9 | 2556.1 | 2910.6 | 3132.1 | 3252.1 | 3133.1 | 2448.2 | 3025.3 | |

| 85+ | 3183.1 | 2848.0 | 3199.1 | 2872.0 | 2823.0 | 2745.5 | 4177.2 | 3286.2 | 3284.9 | 3337.1 | 1982.1 | 3329.5 | |

| Total | 443.8 | 381.8 | 433.2 | 443.0 | 365.2 | 446.8 | 445.9 | 518.7 | 521.3 | 533.2 | 439.6 | 407.6 | |

| 2028–32 | <45 | 52.8 | 46.8 | 45.8 | 42.0 | 29.9 | 53.8 | 51.0 | 55.6 | 57.2 | 36.2 | 59.7 | 28.1 |

| 45–54 | 361.1 | 276.1 | 352.9 | 313.4 | 278.1 | 381.6 | 339.2 | 427.6 | 476.5 | 443.8 | 427.6 | 242.0 | |

| 55–64 | 1121.5 | 873.7 | 1106.0 | 1173.9 | 882.6 | 1186.9 | 1074.8 | 1383.0 | 1343.2 | 1459.9 | 1230.4 | 909.2 | |

| 65–74 | 2106.3 | 1845.6 | 2060.8 | 2239.0 | 1779.0 | 2184.7 | 1973.7 | 2541.9 | 2485.4 | 2730.1 | 2122.2 | 2018.7 | |

| 75–84 | 2682.2 | 2449.9 | 2725.4 | 2670.3 | 2326.4 | 2548.3 | 2832.4 | 3087.4 | 3143.8 | 3089.7 | 2426.8 | 2927.3 | |

| 85+ | 3086.7 | 2794.6 | 3120.2 | 2776.5 | 2689.4 | 2651.1 | 4018.4 | 3189.2 | 3258.1 | 3340.9 | 2043.7 | 2983.8 | |

| Total | 443.2 | 379.5 | 434.9 | 440.6 | 358.8 | 447.9 | 441.4 | 520.1 | 521.9 | 529.5 | 445.8 | 396.8 | |

Abbreviations: AB, Alberta; BC, British Columbia; CA, Canada; MB, Manitoba; NB, New Brunswick; NL, Newfoundland and Labrador; NS, Nova Scotia; ON, Ontario; PE, Prince Edward Island; QC, Quebec; SK, Saskatchewan; TC, All Territories (Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut).

Figure 3.4, presenting the determinants of increases in the total average annual numbers of cancer incidence cases (see Chapter 2 for definitions of the series), shows that the observed and projected increase in the number of cancer cases mainly results from the aging of the population and, to a lesser extent, population growth. Changes in the risk of cancer have been contributing marginally to the increase in new cases, especially in males. In 2028–2032, the percentages of the total changes due to aging, population increase and cancer risk are predicted to be 70.9%, 29.1% and 0.1% respectively in males, and 58.4%, 35.5% and 6.1% in females. In addition, the percentages of the total changes due to change of age distribution increase with time, from 41.5% in 1988–1992 to 70.9% in 2028–2032 in males and from 42.0% to 58.4% in females. The percentages due to change of population size generally decrease over the same period, from 39.8% to 29.1% in males and from 46.8% to 35.5% in females. The percentages due to change of cancer risk decrease in males from 18.7% to 0.1% over the study period, whereas the percentages in females increased from 11.2% in 1988–1992 to 14.1% in 1998–2002 (in part because of increased mammography screening) and decrease thereafter to 6.1% in 2028–2032.

Trends by age

Figure 3.5 shows similar patterns of cancer occurrence and population distribution in males and females. The figure shows the increase in percentage of the population at older ages along with the corresponding increase in the number of expected cancer cases. Cancer cases increase with age until the peak in the 70–74 age group in both sexes, and illustrate approximately bell-shaped symmetric distributions about the peak in the 50-or-older age groups.

FIGURE 3.5. Historic and projecteda growth in average annual population (pop) and in average annual incidence cases of all cancers in Canada by age, 1983–2032.

a Cases and populations in the 2028–2032 period are projected. over one-third of all new cancer cases, will be examined in Chapter 4.

Trends by sex

Figure 3.6 compares the ASIRs for all cancers between sexes by 10-year age group from 1983 to 2032. Cancer is more common in males than in females except in those aged under 55. Breast cancer is the most common cancer in females under 55, accounting for 30% to 40% of cases in this age range in 2003–2007 (see Figure 3.9). Thyroid and cervical cancer also account for the higher cancer incidence in younger females. The overall cancer incidence rate in men aged 65 or older has been falling. The decrease in lung cancer incidence rates in males aged 65 or older as a result of decrease in tobacco use36,42,43 and the decrease in prostate cancer rates in people aged 75 or older have together contributed to the overall decrease in this age range, as these two cancers account for 42% of all new cancer cases in Canadian men in 2003–2007. In women aged 65 or older, the relatively stable rate is the result of an increase primarily of lung cancer incidence offset by decreases in incidence for the other cancer sites.

FIGURE 3.6. Age-standardized incidence rates (ASIRs) for all cancers by age group (–males, –females), Canada, 1983–2032.

FIGURE 3.9. Most common newly diagnosed cancers in Canada, 2003–2007.

a Total of rounded numbers may not equal rounded total number;

b CNS refers to central nervous system cancer;

c NHL refers to non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Trends by geographical region

Figure 3.7 shows historic and estimated ASIRs for all cancers combined by sex and region from 1983 to 2032. In males, the ASIRs for all cancers combined are projected to continue to be highest in the Atlantic region and lowest in British Columbia. Male incidence rates in Quebec, Ontario, the Prairies and British Columbia are projected to decrease and then stabilize, while rates in the Atlantic region will be relatively stable. In females, Ontario is predicted to surpass Quebec and experience the highest rates in 15 years (i.e. after 2018–2022), while British Columbia will continue to have the lowest incidence. Female incidence rates are predicted to increase 10%, 3% and 1% in Ontario, Quebec and the Atlantic region, respectively, and decrease 9% and 7% in British Columbia and the Prairies by 2028–2032. This follows an increasing trend in the former regions prior to 2008 and a decreasing trend in the latter regions starting in 1998–2002. The overall differences in cancer incidence across the country are smaller in females, ranging from 7.1 to 101.8 per 100 000 versus 45.9 to 134.6 per 100 000 in males over the observation and projection periods.

FIGURE 3.7. Age-Standardized Incidence Rates (ASIRs) by region, all cancers, 1983–2032.

Observed most common cancers by sex and age

Figures 3.8 and 3.9 show the most common newly diagnosed cancers by sex and age group for 1983–1987 and 2003–2007. Overall, 52% of new cases in the last observation period (2003–2007) were in males and 48% in females. For males in each period, prostate, lung and colorectum were among the most frequently diagnosed cancer sites, together accounting for just over half the cases. In the last period the incidence of prostate cancer had replaced lung cancer in first place, followed by cancers of the colorectum and bladder. These cancers were similarly distributed for males within the various age groups, with some variation in proportions and ranking. The only exception was the youngest age group (<45 years), in which testis cancer was the most common newly diagnosed cancer. The incidence of testis cancer increased over the 2 periods of study. Other common cancers in the youngest males included non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), leukemia and cancer of the central nervous system (CNS). Prostate cancer cases in men aged 45 to 74 increased markedly and occurred with the highest frequency in the most recent period, as a prevalent pool of undiagnosed cancers were detected by prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening.36

Breast cancer dominated cancer incidence in females, representing the same proportion of 27% of all diagnoses in the 2 periods studied, followed by lung and colorectal cancers (which had switched places between 1983–1987 and 2003–2007). The top 3 cancer diagnoses for females within each age group of 45 or older were these same 3, but with slight variations in rank. For the youngest females (<45 years), the most common newly diagnosed cancer was breast cancer, with 30% of new cases. The other common cancers in this age group included thyroid, cervical cancers and melanoma.

The most noticeable difference between males and females under 45 was the much higher proportion of thyroid cancer incidence in females. The most dramatic changes in the incidence proportions of different types of cancer as a function of age (<45 and 45+) occurred with melanoma, leukemia, CNS tumours, NHL, thyroid and genital tract malignancies.

The incidence proportions (by 10-year age group) of lung cancer in males aged 45 to 74 decreased by 7% to 12% between 1983–1987 and 2003–2007, whereas the incidence proportions of prostate cancer increased more pronouncedly (10%–20%) over the 2 periods for the same age groups. The incidence share attributed to NHL also registered some increase in the 2 youngest age groups, while the proportion of stomach cancer incidence decreased in each age group.

The increase of 6% to 8% between the study periods in the incidence proportion of lung cancer in women 65 or older is notable. A similar trend was observed in European countries.4 The proportional increase in lung cancer incidence in females of all ages was 4% from 1983–1987 to 2003–2007. The incidence percentage also increased notably for NHL in women aged 65 to 84 and for thyroid cancer in those under 55. The proportion of breast cancer incidence increased by 2% to 3% in women aged between 45 and 64. This increased share for breast cancer may be partly attributable to the impact of early detection with the increased uptake of mammography screening. There was a marked reduction in the incidence proportion for cervical cancer in females aged under 45 as well as noteworthy reductions in the incidence proportions for stomach cancer and colorectal cancer in all female age groups. Many more cervical cancers are prevented by screening each year.

Projected most common cancers by sex and age

As the projected change in cancer incidence is attributable primarily to demographic factors, the relative frequencies of major cancers are not expected to change significantly. Figure 3.10 shows the cancer types that are projected to be newly diagnosed with the greatest frequency in 2028–2032 by sex and age group. By 2028–2032, colorectal cancer is projected to have overtaken lung cancer as the second most frequently diagnosed cancer in males, even though colorectal cancer will maintain a similar percentage of the total cancer cases in males as during 2003–2007. This change in ranking is the result of a decrease of 27% in the incidence of lung cancer as a proportion of all cancers, reflecting the historical reduction in smoking prevalence after accounting for a lag period.42–44 In males, the most common cancers in 2028–2032 are projected to be prostate cancer (28%), color-ectal (13%), lung (11%), bladder (6%) and NHL (4%). The age-specific analysis indicates that, between 2003–2007 and 2028–2032, the incidence of lung cancer in males (as a proportion of total cancer cases) will decrease by 19%, 34%, 32%, 30% and 21% for each of the 10-year age groups from 45 to 85 and over, respectively. Another notable change in the incidence frequency will be the 32% decrease in the melanoma incidence proportion in the youngest males (<45 years). Cancers of the prostate, colorectum and lung are projected to be the top 3 most common types, in that order, within each age group from 45 years and older.

For females, the top 4 most common incident cancers are expected to remain the same as in the last observation period (2003–2007). However, thyroid cancer will outrank NHL as the fifth most common cancer. Specifically, the most commonly diagnosed cancers in females in 2028–2032 are projected to be breast cancer (24%), lung cancer (12%), colorectal cancer (12%), uterine cancer (6%), thyroid cancer (5%) and NHL (4%). The overall increase in thyroid cancer will be mainly from the proportional increases of 67% in women aged 45 to 54, 140% in those aged 55 to 64, and 105% in those aged 65 to 74. The 26% predicted reduction in the incidence proportion for cervical cancer in females under 45 will underscore the further success of prevention and screening programs.45,46 Compared with the 2003–2007 age-specific results, the projected most common incident cancers in females will be the same within each 10-year age group, but with changes in ranking order for the under-65 and 75–84 age groups. The cancers in the ‘Other’ category, together representing just over one-third of all new cancer cases, will be examined in Chapter 4.

Chapter 4: Projections by Cancer Site

1. Oral cancer