Abstract

Introduction:

This study aimed to determine the effects of induction of labour in late-term pregnancies on the mode of delivery, maternal and neonatal outcome.

Methods:

We retrospectively analyzed deliveries between 2000 and 2014 at the University Hospital of Cologne. Women with a pregnancy aged between 41 + 0 to 42 + 6 weeks were included. Those who underwent induction of labour were compared with women who were expectantly managed. Maternal and neonatal outcomes were evaluated.

Results:

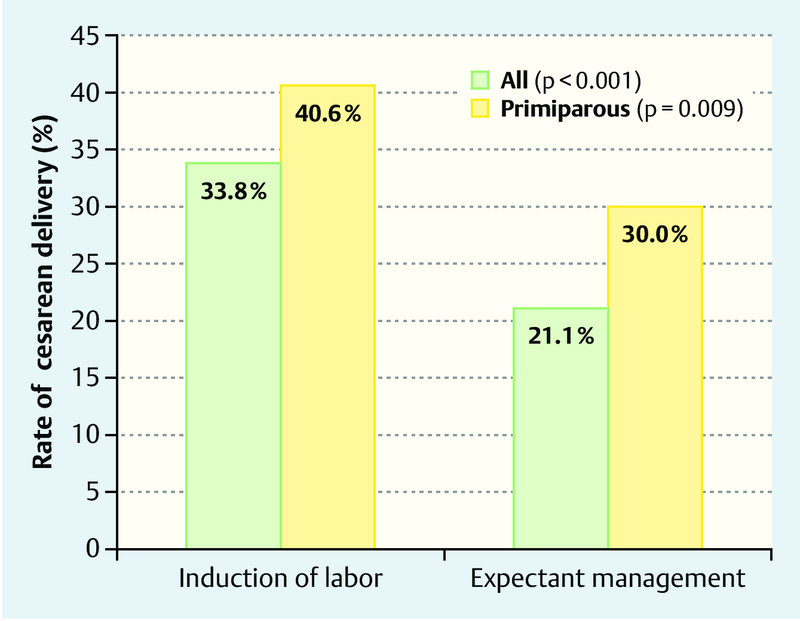

856 patients were included into the study. The rate of cesarean deliveries was significantly higher for the induction of labour group (33.8 vs. 21.1 %, p < 0.001). Aside from the more frequent occurrence of perineal lacerations (induction of labour group vs. expectantly managed group = 38.1 % compared with 26.4 %, p = 0.002) and all types of lacerations (induction of labour group vs. expectantly managed group = 61.5% vs. 52.2 %, p = 0.021) in women with vaginal delivery, there were no significant differences in maternal outcome. Besides, no differences regarding neonatal outcome were observed.

Conclusions:

Our study suggests that induction of labour in late and postterm pregnancies is associated with a significantly higher cesarean section rate. Other maternal and fetal parameters were not influenced by induction of labour.

Key words: induction of labour, delivery, cesarean section, materno-fetal medicine

Abstract

Zusammenfassung

Einleitung: Diese Studie untersuchte die Auswirkungen der Geburtseinleitung in der Spätschwangerschaft bzw. bei Übertragung auf die Art der Entbindung sowie auf das mütterliche und kindliche Outcome. Methoden: Alle in der Universitätsklinik Köln zwischen 2000 und 2014 erfolgten Entbindungen wurden retrospektiv untersucht. Alle Frauen, die in der 41 + 0 bis 42 + 6 Schwangerschaftswoche entbanden, wurden in die Studie eingeschlossen. Schwangere Frauen, bei denen eine Geburtseinleitung durchgeführt wurde, wurden mit Frauen verglichen, die exspektativ behandelt wurden. Die mütterlichen und kindlichen Outcomes wurden ausgewertet. Ergebnisse: Es wurden insgesamt 856 Patientinnen in die Studie aufgenommen. Die Kaiserschnittrate war in der Geburtseinleitungs-Gruppe signifikant höher (33.8 vs. 21.1 %, p < 0.001). Abgesehen von einem häufigeren Auftreten von Dammrissen (Geburtseinleitungs-Gruppe vs. Gruppe mit exspektativem Vorgehen = 38,1 vs. 26,4 %; p = 0,002) sowie aller Arten von Risswunden (Geburtseinleitungs-Gruppe vs. Gruppe mit exspektativem Vorgehen = 61,5 vs. 52,2 %; p = 0,021) bei Frauen, die vaginal entbanden, gab es keine wesentlichen Unterschiede im mütterlichen Outcome. Es gab auch keine signifikanten Unterschiede im Neugeborenen-Outcome zwischen den beiden Gruppen. Schlussfolgerung: Unsere Studie zeigte, dass die Geburtseinleitung bei Terminüberschreitung und Übertragung mit einer signifikant höheren Sectio-Rate verbunden ist. Die Geburtseinleitung führte zu keiner Änderung hinsichtlich anderer mütterlichen und fetalen Faktoren.

Schlüsselwörter: Geburtseinleitung, Entbindung, Kaiserschnittentbindung, Perinatalmedizin

Abbreviations

- ACOG

American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

- ARD

Atad Ripener Device

- BMI

Body mass index

- IOL

Induction of labour

- NICU

Neonatal intensive care unit

- PROM

Premature rupture of membranes

Introduction

The optimal management of postterm pregnancies is a current issue and experts opinions vary. Postterm pregnancies are defined as ≥ 42 + 0 weeks of gestation or ≥ 294 days from the first day of the last menstrual period according to ACOG 1; late-term pregnancies refer to a pregnancy that is ≥ 41 + 0 weeks through 41 + 6 weeks of gestation. Approximately 10 % of all pregnancies are postterm pregnancies 2. The etiology of late or postterm pregnancies is unknown. Genetic factors 3 and an elevated BMI 4 before pregnancy have been assumed. The ACOG recommends offering routine induction or an expectant management after 41 + 0 completed weeks 5. According to the British Guidelines women with uncomplicated pregnancies should usually be offered induction of labour (IOL) between 41 + 0 and 42 + 0 weeks to avoid the risks of prolonged pregnancy 6. German guidelines envisage to offer IOL after 41 + 0 completed weeks and to recommend it ≥ 41 + 3 weeks of gestation in order to avoid fetal complications 7.

Although a few studies showed no differences in maternal and fetal outcomes when IOL has been performed 8, 9, expert opinions vary concerning this issue. In a recently published review 10 including a meta-analysis of trials analyzing the outcome of IOL in postterm pregnancies the authors concluded that IOL reduces the risk of cesarean sections in case of intact membranes. Others who have published studies concerning this issue, reported about increasing cesarean section rates when IOL is performed 11, 12. Additionally, maternal and neonatal outcomes concerning IOL were discussed controversially as well. Most studies showed no differences in maternal outcomes such as laceration or hemorrhage when IOL has been performed 8, 13, 14, 15. In another study the authors concluded that the maternal outcome could be impacted by IOL, such as a trend towards decreased postpartum hemorrhage 9.

Prolonged pregnancy is known to be associated with higher neonatal and maternal morbidity and mortality 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24. For example, the fetal mortality 20, the Apgar score, the rate of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admissions 22 and maternal complications such as lacerations and postpartum hemorrhage 18 increases with gestational age. To decrease the risk of adverse outcome of prolonged pregnancy antenatal surveillance and IOL seems to be necessary.

The aim of our study was to evaluate a large cohort of patients that gave birth in our hospital and to report the outcome of patients with IOL in late and postterm pregnancies compared to those with expectant delivery. Therefore, we focussed on both maternal and neonatal outcome, in particular on the mode of delivery.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of late-term and postterm pregnancies (41 + 0 to 42 + 6 weeks) in which we compared IOL to a policy of expectant management. The data was acquired retrospectively from our birth database Viewpoint between 2000 and 2014. The digital database contained obstetrical and neonatal information from all deliveries in our hospital.

Selection of study groups

Inclusion criteria were live singleton gestation with a cephalic presentation, a gestational age from 41 + 0 to 42 + 6 and no primary cesarean section. For the IOL group, we included women undergoing an IOL just for late-term or postterm pregnancies. Women undergoing an IOL for a medical indication, such as diabetes mellitus, premature rupture of membranes (PROM) and preeclampsia were excluded from the study, as well as women who had an IOL without prostaglandin as first induction medication. Besides, patients having sonographic abnormalities (oligohydramnion, placental insufficiency and suggested macrosomia) or fetuses with malformation were also excluded.

Management of study groups

We compared women who had an IOL to women who were expectantly managed in late and postterm pregnancies. IOL was always induced by prostaglandin gel or tablet solely or in combination with oxytocin infusion, Atad Ripener Device (ARD) or amniotomy. Patients who had a cesarean section before had an IOL with vaginal gel. The first application includes 1 mg of Minprostin gel, after 6 hours 2 mg of Minprostin gel were applicated. Maximum daily dosage was 3 mg. Application was continued until uterine contractions were noticed. IOL was attempted until contraindications for spontaneous delivery could be noticed such as pathologic CTG, suspected uterine rupture and maternal exhaustion. Patients having an IOL with prostaglandin tablets received two dosages of 50 µg every 6 hours, afterwards they received 100 µg every 4 hours. Patients who had no IOL and had a spontaneous onset of labour were considered to be part of the control group called expectantly managed group. Those patients were seen in the hospital until then every two days for CTG and amniotic fluid controls from 40 + 0 weeks of gestation. The management was determined by the individual doctor on duty. Induction would have been recommended in case of reduced amniotic fluid, suspicious CTG, decreasing fetal movements, but those patients were excluded from the study.

Data collection

In each group data about the mode of delivery, the number of cesarean deliveries, operative vaginal and spontaneous delivery were assessed as the primary outcome. The secondary outcomes included maternal complications and fetal outcome. Maternal complications were assessed by the occurrence of lacerations, episiotomies, atonic hemorrhage and appearance of other complications during labour (laceration-associated hemorrhage, retention of placenta, uterine rupture and maternal death) were collected. Relevant hemorrhage has been defined as a blood loss of more than 1000 ml.

The neonatal outcome was assessed by the umbilical cord blood pH to evaluate fetal asphyxia, the Apgar score at five minutes, respiratory status, birth weight, birth weight ≥ 4000 g, the rate of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admissions and neonatal death. According to the literature 25, 26, 27, an umbilical cord blood pH below 7,1 has been defined as critical to evaluate fetal asphyxia. As a final point, we analysed all above-named variables concerning primiparous women.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 22.0. The normal distribution of data was proven with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Student t-tests and Mann-Whitney U test were performed in order to explore significant differences between the two groups. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 4200 patients were identified from our birth database at the University Hospital of Cologne, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, between 2000 and 2014. From this group we had to exclude 3344 patients due to the criteria mentioned above. The remaining 856 patients were included in the study, of which 400 (46.7 %) underwent IOL and 456 (53.3 %) were expectantly managed beyond 41 + 0 weeks.

Demographic data

400 women who underwent IOL were compared with 456 women who underwent expectant management. The demographic characteristics of both groups are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Maternal demographic characteristics. In italics: primiparous.

| Induction of labour group (n = 400) (n = 251) | Expectantly managed group (n = 456) (n = 227) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| a Statistically significant difference (p < 0.05), Mann-Whitney U test | |||

| Age mean ± SD (years) | 32.24 ± 5 32.22 ± 6 | 31.83 ± 5 31.33 ± 5 | 0.197 0.046a |

| BMI before pregnancy ± SD (kg/m2) | 24.12 ± 5 23.80 ± 5 | 24.21 ± 4 24.23 ± 4 | 0.405 0.142 |

| Parity, n (%) | < 0.001a | ||

|

251 (62.9 %) | 227 (50.4 %) | |

|

148 (37.1 %) | 223 (49.6 %) | |

| Gestational age at admission (weeks) | 41.21 ± 0.3 41.23 ± 0.3 | 41.26 ± 0.3 41.26 ± 0.3 | 0.001a 0.036a |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 41.29 ± 0.3 41.32 ± 0.3 | 41.26 ± 0.3 41.28 ± 0.3 | 0.017a 0.011a |

| Weight gain during pregnancy ± SD (kg) | 15.25 ± 5 15.5 ± 5 | 13.96 ± 6 14.8 ± 6 | 0.001a 0.180 |

The IOL and expectantly managed groups were similar in maternal characteristics concerning age and BMI before pregnancy. Parity, gestational age and weight gain during pregnancy were statistically significant different between the two groups. In the IOL group 62.9 % were primiparous women compared to 50.4 % in the expectantly managed group. The median weight gain during pregnancy was 15 ± 5 kg in the IOL group and 14 ± 6 kg in the expectantly managed group.

Focusing on primiparous women, there were 251 women who underwent IOL, compared to 227 women who underwent expectant management. The demographic characteristics of both groups are also presented in Table 1.

The IOL and expectantly managed groups were similar in maternal characteristics including BMI before pregnancy and weight gain during pregnancy. The maternal age and the gestational age were statistically significant different between the two groups (p < 0.05).

Maternal outcome

Table 2 demonstrates the maternal outcome in both groups. The mode of delivery was statistically significantly different between the two groups (p < 0.001). First, the rate of cesarean deliveries was significantly higher in the IOL group vs. the expectantly managed group (33.8 vs. 21.1 %, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1); second, 53.5 % of the induced patients vs. 66.4 % of those expectantly managed delivered spontaneously (p < 0.001). The operative vaginal delivery rate was 12.8 and 12.5 %, respectively, and showed no statistically significant difference (p = 0.903). The indications for secondary cesarean section are listed in Table 2. The most frequent indication for secondary cesarean section in both groups was an abnormal CTG (IOL group: 46,9 % vs. 34,0 % in the expectant management group).

Table 2 Maternal outcome. In italics: primiparous.

| Induction of labour group (n = 400) (n = 251) | Expectantly managed group (n = 456) (n = 227) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| a Statistically significant difference (p < 0.05), Mann-Whitney U test | |||

| Mode of delivery, n (%) | < 0.001a 0.009a | ||

|

135 (33.8 %) 102 (40.6 %) | 96 (21.1 %) 68 (30.0 %) | |

|

51 (12.8 %) 46 (18.3 %) | 57 (12.5 %) 41 (18.1 %) | |

|

214 (53.5 %) 103 (41.0 %) | 303 (66.4 %) 118 (52.0 %) | |

| Indication for cesarean delivery | < 0.001a 0.009a | ||

|

61 (46.9 %) | 32 (34.0 %) | |

|

48 (36.9 %) | 26 (27.7 %) | |

|

19 (14.6 %) | 19 (20.6 %) | |

|

7 (5.4 %) | 9 (9.6 %) | |

|

12 (9.2 %) | 12 (12.8 %) | |

|

8 (6.2 %) | 11 (11.7 %) | |

| Maternal complications at vaginal delivery, n (%) | |||

|

16 (6.0 %) 14 (9.4 %) | 10 (2.8 %) 8 (5.0 %) | 0.044a 0.138 |

|

163 (61.5 %) 92 (61.7 %) | 188 (52.2 %) 83 (52.2 %) | 0.021a 0.092 |

|

113 (42.6 %) 86 (57.7 %) | 175 (48.6 %) 102 (64.2 %) | 0.139 0.248 |

| Maternal complications, n (%) | |||

|

7 (1.8 %) 7 (2.8 %) | 3 (0.7 %) 2 (0.9 %) | 0.134 0.124 |

|

11 (2.8 %) 8 (3.2 %) | 15 (3.3 %) 7 (3.1 %) | 0.665 0.942 |

|

0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | 1 |

Fig. 1.

Rate of cesarean delivery after induction of labour (left) and expectant management (right).

There were 265 vaginal deliveries in the IOL group and 360 vaginal deliveries in the expectantly managed group. Concerning these women, the rate of all types of lacerations, such as perineal, cervical, labial or other lacerations (61.5 % in the IOL group vs. 52.2 % in the expectant group, p = 0.021) and the rate of perineal lacerations (1st/2nd/3rd degree) was significantly higher in the IOL group compared to expectantly managed group (38.1 % vs. 26.4 %, p = 0.002).

Analyzing 3rd degree lacerations seperatly from other lacerations, deliveries in the induced group were associated with a significantly higher rate compared to deliveries in the expectantly managed group (6 % vs. 2,8 %, p = 0,044). However, within the subgroup of primiparous women, the differences between the IOL group and expectantly managed group was not significant (9,4 % vs. 5,0 %, p = 0,138).

Other maternal outcomes, including the rate of epsiotomy and maternal death (no event) were not statistically significant different between the two groups.

In a subanalysis, we evaluated the maternal outcome for primiparous women only. The results were largely in line with the results regarding all included women and can be found in Table 2. It should be noticed that the rate of lacerations and the rate of epsiotomies were not significantly different within the two groups.

Binary logistic regression

In order to analyze the variables that have an impact on the delivery mode we did a binary logistic regression. The binary logistic regression analysis showed that parity (p = 0,001), gestational age at admission (p = 0,009) and IOL (p = 0,001) had an impact on the cesarean sectio rate. Patients with IOL have a higher risk for cesarean section, whereas multiparity is associated with higher rate of vaginal deliveries. Low gestional age seems to be associated with higher rate of vaginal deliveries. Weight gain has no influence on the mode of delivery (p = 0,562). The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3 Binary logistic regression. Influence of parity, gestional age at admission, induction of labour and weight gain on delivery mode.

| OR (95 % CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|

| a Statistically significant (p < 0.05) | ||

| Parity | 0,340 (0,184–0,627) | 0,001 |

| Gestational age at admission (weeks) | 0,300 (0,121–0,741) | 0,009 |

| Induction of labour | 1,973 (1,332–2,923) | 0,001 |

| Weight gain during pregnancy | 1,017 (0,961–1,075) | 0,562 |

Neonatal outcome

Neonates in the IOL group needed mask ventilation more often than neonates in the expectantly managed group (12.3 vs. 7.7 %, p = 0.025). To analyse this further, we evaluated the rate of mask ventilation in the subgroup of vaginally born neonates and neonates who were born via cesarean section. There was no statistically significant difference within the two subgroups. Concerning other neonatal outcomes on the aforementioned variables, no significant differences could be noticed (Table 4).

Table 4 Neonatal outcome.

| Induction of labour group (n = 400) | Expectantly managed group (n = 456) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| a Statistically significant difference (p < 0.05), Mann-Whitney U test | |||

| Umbilical cord blood pH < 7.1, n (%) | 8 (2,0 %) | 6 (1,4 %) | 0.451 |

| Apgar < 7 after five minutes, n (%) | 9 (2.3 %) | 3 (0.7 %) | 0.049a |

| Respiratory status, n (%) | |||

|

49 (12.3 %) | 35 (7.7 %) | 0.025a |

|

24 (9.1 %) | 19 (5,3 %) | 0.065 |

|

25 (18.7 %) | 16 (16.8 %) | 0.725 |

|

45 (11.3 %) | 35 (7.7 %) | 0.071 |

|

6 (1.5 %) | 3 (0.7 %) | 0.225 |

| Birth weight (g) | 3 647 ± 373 | 3 650 ± 401 | 0.688 |

| Birth weight ≥ 4 000 g, n (%) | 68 (17.0 %) | 88 (19.3 %) | 0.385 |

| NICU admission, n (%) | 27 (6.8 %) | 25 (5.5 %) | 0.439 |

| Neonatal death | – | – | 1 |

Discussion

International trials led to a controversial discussion whether to end a late or postterm pregnancy with IOL or not. The aim of our study was to contribute to the discussion with our experiences and results. We retrospectively analyzed IOL in late and postterm pregnancies at the University Hospital of Cologne. In this context we have focused on maternal and fetal outcomes and compared the data with those patients who were expectantly managed.

Our most important finding, a higher risk of cesarean delivery in the IOL group, is in accordance with other studies. Several trials indicated a higher likelihood of cesarean section following labour induction 11, 12, 28, 29, 30, 31. Within the subgroup of primiparous women, we found similar results concerning mode of delivery and risk of cesarean delivery as compared to the whole study group.

Nevertheless, the finding of our study contrasts with those of some previous studies.

A few authors concluded that IOL leads to a reduction of cesarean section rate 25, 32, 33. The different results are possibly based on different study designs. Roach et al. 32 induced women who were beyond 42 + 0 weeks of gestation, whereas we decided to include women who had a gestional age of 41 + 0 weeks to 42 + 6 weeks at admission. Hannah et al. 25 did not exclude fetal malformation which might have influenced the results of their study.

Wood et al. 10 reviewed 19 trials concerning IOL in postterm pregnancies and the risk of cesarean section. In this analysis, IOL was also associated with a risk reduction of cesarean section (OR 0.85; 95 % CI [0.75, 0.95]). The authors themselves admitted that this effect may arise from non-treatment effects and that additional trials are needed. Several other studies found a similar cesarean rate in both groups 8, 9, 15, 26, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38. Direct comparisons among studies are not always practicable. Several studies included only women with certain Bishop scores 15, 35, women with certain BMI 11 or exclusively primiparous women 12, 28. Our study included all women irrespectively of their cervical ripeness, BMI or parity.

Although it is known that cervical ripeness has a big influence on the success of IOL 39 these data could not be assessed due to the retrospective study design.

It is possible that this might have influenced the maternal outcome in these two study groups. Besides, it should be noted that different studies showed a correlation between maternal characteristics and the cesarean delivery rate. A higher maternal age 25, 40, 41 and primiparity is associated with a higher rate of cesarean delivery. These conclusions are in line with our results.

Secondly, we noted in our study a similar rate of operative vaginal delivery in both groups. This finding is in accordance with that of other studies 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 29, 31, 33, 35, 42, 43. Hermus et al. 26 reported a rate of 14.8 % in both IOL and expectantly managed group. Furthermore, we found a slightly higher rate of perineal lacerations and of all types of lacerations in patients who had a vaginal delivery within the IOL group.

The higher risk of perineal and other lacerations in the IOL might be related to the higher rate of primiparous women in this group. In primiparous women, the rate of lacerations did not differ between the two groups. These results suggest that IOL has no impact on the rate of lacerations if this factor is adjusted for the effect of parity. Considering this point, our finding of a higher rate of lacerations in the IOL group does not contrast with other studies 9, 11, 41 which did not find any differences in that respect. Our finding of a similar risk of episiotomy after IOL is in accordance with that of other studies 41. Concerning atonic hemorrhage we found no significant differences between both groups, but we found a trend that showed a higher rate of atonic hemorrhage in the IOL group. IOL is known to be associated with a higher rate of postpartum hemorrhage 44.

Regardless of the analysed differences between the two groups, it must be kept in mind that a higher gestational age is associated with increasing rates of complications. Alexander et al. 17 observed increasing labour complications such as length of labour. Furthermore the risk of maternal infection 16, post-partum hemorrhage and obstetric trauma increases with gestational age 21, 45. There is also an increasing rate of cesarean section with higher gestational age 21, 22 that should be considered.

Our study found that the neonatal outcome did not differ between the IOL and the expectantly managed group. Wennerholm et al. 42 noted the same in their meta-analysis. They reported an equal rate of low APGAR score after five minutes, intensive care unit admissions and perinatal mortality rate in both groups. Hermus et al. 26 observed a similar finding in their retrospective matched cohort study. They did not find any difference in umbilical cord blood pH < 7, Apgar score at five minutes under 7, birth weight or NICU admittance in the IOL group as compared to the expectantly managed women. Furthermore, these findings are underlined by several other studies 10, 25, 34, 37, 43.

In our study we were able to show a higher rate of mask ventilation needed in the IOL group. The higher rate of mask ventilation in the IOL group is probably due to the fact that in this group a higher rate of cesarean delivery can be found. This is confirmed by evaluating the rate of mask ventilation concerning neonates that were born vaginally or via cesarean section seperately. When considering patients who had cesarean sections, the need for mask ventilation was not statistically significant different in the two groups (18.7 % [IOL group] vs. 16.8 % [expectantly managed group]).

The present study clearly shows that the neonatal outcome does not differ between induced patients and expectantly managed pregnancies beyond 41 + 0 weeks. It can therefore be concluded that the decision between IOL and expectant management in late and postterm pregnancies does not have decisive influence on the neonatal mortality and morbidity. Nonetheless it must be kept in mind that a higher gestational age is associated with a rise in stillbirth and perinatal/neonatal deaths 20, 21. Furthermore the risk of other neonatal complications such as aspiration, pneumonia or asphyxia rises strongly with gestational age 21.

The large number of variables available in the Viewpoint Database register, including information on delivery mode, method of induction, a range of different information about maternal demographic data, maternal outcome and neonatal outcome, has to be considered as a strength of our study. This allowed us to conduct a detailed examination of current management practices and outcomes beyond 41 + 0 weeks. Our study groups are quite homogenous due to strict inclusion criteria.

The retrospective study design has to be considered as a limitation, therefore it has potential for confounding and selection bias such as cervical ripening, which was not documented for all patients. To keep the influence to a minimum we applied strict inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Our study suggests that IOL in late and postterm pregnancies is associated with significantly higher cesarean delivery rate. There was no evidence that other maternal and neonatal complications differ. Nevertheless it has to be kept in mind that with increasing gestational age, rate of maternal and neonatal complications rise, which indicates that prolonged pregnancies should be delivered promptly. Overall, the choice of whether or not late and postterm pregnancies should be induced cannot be conclusively clarified. The decision should be taken individually together with the patients after an active exchange about advantages and disadvantages.

Authorsʼ contribution

F. Thangarajah: Protocol/project development, Manuscript writing/editing, Data analysis

P. Scheufen: Protocol/project development, Manuscript writing/editing, Data analysis

V. Kirn: Manuscript writing/editing

P. Mallmann: Protocol/project development, Data collection and management

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest The authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

Equally contributing authors

References

- 1.ACOG . ACOG practice patterns. Management of postterm pregnancy. Number 6, October 1997. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1998;60:86–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norwitz E R, Snegovskikh V V, Caughey A B. Prolonged pregnancy: when should we intervene? Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;50:547–557. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31804c9b11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laursen M, Bille C, Olesen A W. et al. Genetic influence on prolonged gestation: a population-based Danish twin study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:489–494. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stotland N E, Washington A E, Caughey A B. Prepregnancy body mass index and the length of gestation at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:3780–3.78E7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ACOG . ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 107: Induction of labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(2 Pt 1):386–397. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b48ef5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Induction of Labour, NICE Clinical guideline 70Online:http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg70/resources/guidance-induction-of-labour-pdflast access: 01.10.2014

- 7.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe Leitlinie Vorgehen bei Terminüberschreitung und Übertragung [updated 2014 Oct 22]Online:http://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/015-065l_S1_Termin%25C3%25BCberschreitung_%25C3%259Cbertragung_02-2014.pdflast access: 22.10.2014

- 8.Daskalakis G, Zacharakis D, Simou M. et al. Induction of labor versus expectant management for pregnancies beyond 41 weeks. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27:173–176. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.806892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hutcheon J, Harper S, Strumpf E. et al. Using inter-institutional practice variation to understand the risks and benefits of routine labour induction at 41(+0) weeks. BJOG. 2015;122:973–981. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wood S Cooper S Ross S Does induction of labour increase the risk of caesarean section? A systematic review and meta-analysis of trials in women with intact membranes BJOG 2014121674–685.discussion 685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolfe H, Timofeev J, Tefera E. et al. Risk of cesarean in obese nulliparous women with unfavorable cervix: elective induction vs. expectant management at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:530–5.3E6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vrouenraets F P, Roumen F J, Dehing C J. et al. Bishop score and risk of cesarean delivery after induction of labor in nulliparous women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:690–697. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000152338.76759.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caughey A B Sundaram V Kaimal A J et al. Systematic review: elective induction of labor versus expectant management of pregnancy Ann Intern Med 2009151252–263.W53–W63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chanrachakul B, Herabutya Y. Postterm with favorable cervix: is induction necessary? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2003;106:154–157. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(02)00243-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osmundson S, Ou-Yang R J, Grobman W A. Elective induction compared with expectant management in nulliparous women with an unfavorable cervix. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:583–587. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820caf12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang M, Fontaine P. Common questions about late-term and postterm pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:160–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexander J M, McIntire D D, Leveno K J. Forty weeks and beyond: pregnancy outcomes by week of gestation. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:291–294. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00862-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caughey A B, Stotland N E, Washington A E. et al. Maternal and obstetric complications of pregnancy are associated with increasing gestational age at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:1550–1.55E8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng Y W, Nicholson J M, Nakagawa S. et al. Perinatal outcomes in low-risk term pregnancies: do they differ by week of gestation? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:3700–3.7E9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruckner T A, Cheng Y W, Caughey A B. Increased neonatal mortality among normal-weight births beyond 41 weeks of gestation in California. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:4210–4.21E9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olesen A W, Westergaard J G, Olsen J. Perinatal and maternal complications related to postterm delivery: a national register-based study, 1978–1993. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:222–227. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakling J, Backe B. Pregnancy risk increases from 41 weeks of gestation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85:663–668. doi: 10.1080/00016340500543733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hilder L, Sairam S, Thilaganathan B. Influence of parity on fetal mortality in prolonged pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;132:167–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ingemarsson I, Källén K. Stillbirths and rate of neonatal deaths in 76,761 postterm pregnancies in Sweden, 1982–1991: a register study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1997;76:658–662. doi: 10.3109/00016349709024606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hannah M E, Hannah W J, Hellmann J. et al. Induction of labor as compared with serial antenatal monitoring in post-term pregnancy. A randomized controlled trial. The Canadian Multicenter Post-term Pregnancy Trial Group. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1587–1592. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199206113262402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hermus M A, Verhoeven C J, Mol B W. et al. Comparison of induction of labour and expectant management in postterm pregnancy: a matched cohort study. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2009;54:351–356. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hernández-Martínez A, Pascual-Pedreño A I, Baño-Garnés A B. et al. Relation between induced labour indications and neonatal morbidity. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;290:1093–1099. doi: 10.1007/s00404-014-3349-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prysak M. Elective induction versus spontaneous labor: a case-control analysis of safety and efficacy. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00115-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Gemund N, Hardeman A, Scherjon S A. et al. Intervention rates after elective induction of labor compared to labor with a spontaneous onset. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2003;56:133–138. doi: 10.1159/000073771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katz Z, Yemini M, Lancet M. et al. Non-aggressive management of post-date pregnancies. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1983;15:71–79. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(83)90175-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boulvain M, Marcoux S, Bureau M. et al. Risks of induction of labour in uncomplicated term pregnancies. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001;15:131–138. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roach V J, Rogers M S. Pregnancy outcome beyond 41 weeks gestation. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1997;59:19–24. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(97)00179-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stock S J, Ferguson E, Duffy A. et al. Outcomes of elective induction of labour compared with expectant management: population based study. BMJ. 2012;344:e2838. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Witter F R, Weitz C M. A randomized trial of induction at 42 weeks gestation versus expectant management for postdates pregnancies. Am J Perinatol. 1987;4:206–211. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-999774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nielsen P E, Howard B C, Hill C C. et al. Comparison of elective induction of labor with favorable Bishop scores versus expectant management: a randomized clinical trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005;18:59–64. doi: 10.1080/14767050500139604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heimstad R, Skogvoll E, Mattsson L. et al. Induction of labor or serial antenatal fetal monitoring in postterm pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:609–617. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000255665.77009.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parry E, Parry D, Pattison N. Induction of labour for post term pregnancy: an observational study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;38:275–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1998.tb03065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.James C, George S S, Gaunekar N. et al. Management of prolonged pregnancy: a randomized trial of induction of labour and antepartum foetal monitoring. Natl Med J India. 2001;14:270–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crane J M. Factors predicting labor induction success: a critical analysis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49:573–584. doi: 10.1097/00003081-200609000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heffner L. Impact of labor induction, gestational age, and maternal age on cesarean delivery rates. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:287–293. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bodner-Adler B, Bodner K, Pateisky N. et al. Influence of labor induction on obstetric outcomes in patients with prolonged pregnancy. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2005;117:287–292. doi: 10.1007/s00508-005-0330-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wennerholm U, Hagberg H, Brorsson B. et al. Induction of labor versus expectant management for post-date pregnancy: is there sufficient evidence for a change in clinical practice? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88:6–17. doi: 10.1080/00016340802555948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gülmezoglu A M Crowther C A Middleton P et al. Induction of labour for improving birth outcomes for women at or beyond term Cochrane Database Syst Rev 20126CD004945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khireddine I, Le Ray C, Dupont C. et al. Induction of labor and risk of postpartum hemorrhage in low risk parturients. PloS one. 2013;8:e54858. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mandruzzato G, Alfirevic Z, Chervenak F. et al. Guidelines for the management of postterm pregnancy. J Perinat Med. 2010;38:111–119. doi: 10.1515/jpm.2010.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]