Abstract

Objective:

To examine the value of a repeat measurement some days after the first cervical length measurement done at the time of preterm contractions.

Study Design:

Retrospective study involving women with singleton pregnancies who presented with preterm contractions at 24 to 33 + 6 weeks of gestation. The cervical length was measured at the time of presentation and some days afterwards.

Results:

The study population consisted of 17 cases with a preterm delivery within 14 days and 288 uneventful pregnancies. Univariate logistic regression analysis indicated a significant correlation between delivery within 14 days and both, the first and second cervical length measurements as well as the difference between the two measurements. Up to a false positive rate of 20 %, ROC curve analysis showed an improved detection rate for preterm delivery by inluding both measurements. At a false positive rate of 10 % – which corresponds to a first and second cervical length of 10 and 9 mm – the detection rate was 17.6 % with the first cervical length measurement, 47.0 % with the second and 52.9 % if the difference between both measurements was added.

Conclusion:

Our results indicate that in women with symptoms of preterm labor it is worth to repeat the measurement some days later and to take into account the difference between both measurements.

Key words: labor, cervical length, ultrasonography, preterm delivery

Abstract

Zusammenfassung

Ziel: Ziel der Studie war es, bei Patientinnen mit vorzeitiger Wehentätigkeit den Nutzen einer wiederholten Messung der Zervixlänge zu prüfen. Design der Studie: Retrospektive Studie bei Frauen mit Einlingsschwangerschaften, die sich zwischen der 24 + 0 und 33 + 6 SSW wegen vorzeitiger Wehentätigkeit vorstellten. Die Zervixlänge wurde bei der Erstvorstellung sowie einige Tage danach gemessen. Ergebnisse: Untersucht wurden 17 Patientinnen, die innerhalb von 14 Tagen nach Vorstellung vorzeitig entbanden, sowie 288 Frauen mit komplikationslosen Schwangerschaften. Bei der univariaten logistischen Regressionsanalyse zeigte sich eine signifikante Korrelation zwischen vorzeitiger Entbindung innerhalb von 14 Tagen und beiden Zervixlängenmessungen sowie deren Unterschied. Die ROC-Kurvenanalyse wies bis zu einer Falsch-Positiv-Rate von 20 % eine deutlich höhere Detektionsrate für vorzeitige Entbindungen durch die Kombination der Parameter auf. Bei einer Falsch-Positiv-Rate von 10 % – die einer Zervixlänge von jeweils 10 bzw. 9 mm bei der Erst- bzw. Zweitmessung entspricht – lag die Detektionsrate bei der ersten Messung der Zervixlänge bei 17,6 %, bei der Zweitmessung bei 47,0 % und, wenn der Unterschied zwischen den beiden Messwerten mitgerechnet wurde, bei 52,9 %. Schlussfolgerung: Unsere Ergebnisse zeigen, dass es bei Frauen mit vorzeitigen Wehen nützlich sein kann, die Messung der Zervixlänge einige Tage nach der Erstmessung zu wiederholen und auf den Unterschied beider Messwerte zu achten.

Schlüsselwörter: Wehen, Zervixlänge, Sonografie, Frühgeburt

Introduction

Prematurity remains one of the leading causes of perinatal morbidity and mortality as well as long term disability. Approximately 30 % of preterm births are the result of idiopathic preterm labor. However, only about 10–15 % of women presenting with symptoms of preterm labor deliver within the next two to seven days 1. Therefore, it is not only critical to continue to search for effective therapies for preterm labor but also to improve our ability to identify patients that require treatment.

It has been shown that clinical examination, including digital examination of the cervix and uterine monitoring, fails to reliably identify the population of women that is destined to delivery within days of presentation. Therefore, a number of attempts have been made to develop tools that would help to distinguish between true and false preterm labor. The Health Technology Assessment (HTA) study from Honest et al. highlighted several approaches that appear to be useful in distinguishing patients that will deliver shortly after presentation and those that will not. The factors that they found to increase risk of premature delivery included short cervical length measured by transvaginal ultrasound and identification of endocervical funneling, absence of fetal breathing movements, elevated amniotic fluid interleukin-6 level, and elevated maternal serum C-reactive protein 2. Other studies have identified cervical fetal fibronectin as a possibly useful predictor 3.

The most studied modality in this arena has been cervical assessment using transvaginal ultrasound 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9. This is due to the fact that transvaginal ultrasound is of no risk to the mother and the fetus, it is readily available and relatively easy to use, and the results are rapidly available at the bedside. In a meta-analysis of Sotiriadis et al. the authors tried to generate the most informative cervical length cut-off. They found that with a cut-off of 15 mm, the detection rates for delivery within 48 hours, seven days, and before 34 weeks were 71 %, 60 % and 46 %, respectively for false positive rates of 13 %, 10 % and 6 %, respectively 10. Hiersch et al. investigated whether cervical length cut-offs vary according to gestational age for delivery within 14 days after presentation 11. They held the negative predictive value at 90 % and found that the optimal cut-offs are 12, 14, 21 and 40 mm at 32–33, 30–31, 27–29 and 24 to 26 weeksʼ gestation, respectively. This study does suggest that adjusting cut-off according to gestational age may be appropriate. However, the cut-offs themselves are brought into question by the fact that the median cervical length at 24–26 weeksʼ gestation is only about 35 mm making their cut-off of 40 mm improbable 12.

There is ample evidence that transvaginal ultrasound assessment of the cervix and measurement of its length are helpful in predicting the risk of delivery in patients presenting with preterm contractions. However, much less is known about whether the predictive accuracy could be improved by obtaining serial measurements of the cervix after admission 13, 14, 15, 16. Intuitively, one would assume the cervix is more likely to progressively shorten in patients with true preterm labor as compared to patients with false preterm labor 13. This could provide an additional way to establish an individualized risk of preterm birth. It could influence decisions regarding admission at a hospital that has the ability to provide neonatal intensive care and the length of admission. It could also influence decisions regarding tocolysis and corticosteroid administration to improve fetal lung maturity 17.

In this study, we examine the value of a repeat measurement some days after the first cervical length measurement done at the time of the patientʼs presentation with preterm contractions.

Materials and Methods

Inclusion criteria

This is a retrospective study involving all women with singleton pregnancies who presented to the perinatal unit at the University Hospital of Tuebingen, Germany with painful and regular uterine contractions at 24 to 33 + 6 weeks of gestation between 2011 and 2014. Women with ruptured membranes, history of conization of the cervix, those who had a cerclage placed in the current pregnancy, and those in active labor (defined by the presence of cervical dilatation of ≥ 3 cm) were excluded.

Data search

The patients were searched for using our digital perinatology database. The following data were recorded: gestational age at presentation, gestational age at delivery, initial digital cervical assessment (cervical dilatation of ≥ 3 cm or not), cervical length measurements using transvaginal ultrasound at various points during the patientʼs hospitalization, maternal age and weight, gravidity and parity, white blood cell count, maternal serum C-reactive protein levels, and presence or absence of bacterial vaginosis.

Medical treatment and recording

The perinatal unit at the University Hospital of Tuebingen is a tertiary referral center with about 3000 deliveries a year. At our institution, standard management of women suspected to be in preterm labor includes a transvaginal measurement of the cervical length by an experienced obstetrician, administration of tocolytics (in general oral nifedipine) for no more than 48 hours, administration of steroids and vaginal progesterone if the cervical length is 25 mm or less, and antibiotics if an ascending infection is suspected 9, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22. The cervical length is reassessed after two to five days after the initial assessment. The time interval between the two measurements depends on the patientʼs symptomatology. All available ultrasound data were entered into a digital database (Viewpoint, GE Healthcare, Munich, Germany). The outcome of the pregnancies was added as soon as it was available.

According to the German legislation and internal SOP, the retrospective analysis of data of our patients does require an approval of the local IRB. However, the local ethical committee was informed about the study (Project No. 447/2105R).

Statistical analysis

Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to examine significant covariates for a delivery within 14 days and before 34 + 0 weeks of gestation. A ROC curve analysis was used to compare the first and second cervical length measurement and the additional assessment of the difference between both measurements (measurement 2 – measurement 1). A p-value of 0.05 was used as significance level.

Results

Description of the study population

The study population involved 310 pregnancies. Mean maternal age and weight was 31.0 (± 5.8) years and 70.2 (± 13.2) kg, respectively. 306 (98.7 %) were Caucasians. 193 (62.3 %) were nulliparous and 27 (8.7 %) had a history of a preterm delivery before 37 weeksʼ gestation. Mean gestational age at the time of delivery was 37.5 (± 3.1) weeksʼ gestation. In 6 (1.9 %), 32 (10.3 %) and 99 (31.9 %) of the cases, delivery occurred before 28, 34 and 37 weeksʼ gestation, respectively. Delivery within 7 and 14 days of presentation occurred in 14 (4.5 %) and 22 (7.1 %) of the cases, respectively.

First and second measurement of the cervical length

Mean gestational age at the time of the first examination was 29.0 (± 3.0) weeksʼ gestation and mean cervical length was 19.4 (± 8.6) mm. In 5 (1.6 %) cases, delivery occurred in less than 48 h, so that a second cervical assessment could not be performed. In this group, mean cervical length was 3.2 mm (cervical length measurements 0.0, 0.0, 2.0, 6.0 and 8.0 mm). These five cases were excluded from further analysis.

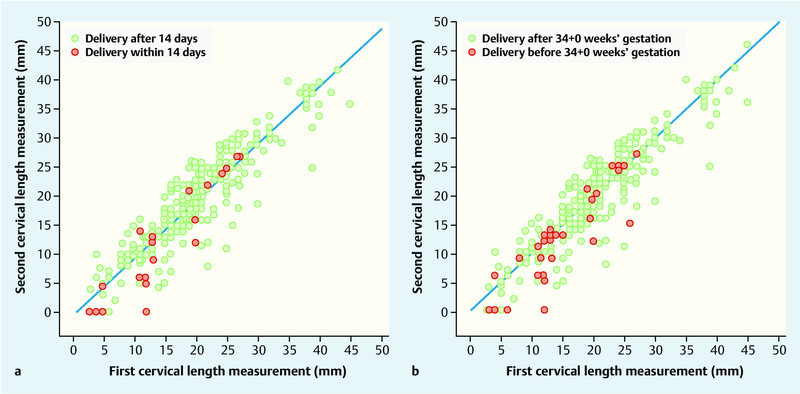

In the remaining 305 pregnancies – including 17 and 27 cases with preterm delivery within 14 days and before 34 weeks respectively – the cervical length was reassessed 3.6 days (± 1.5) days later. The average cervical length at the time of the second measurement was 19.1 (± 8.6) mm (Fig. 1). Mean time interval between both measurements did not correlate with the difference between the two measurements (r = 0,015; p = 0.799). Within the group of pregnancies that were delivered within the subsequent 14 days, the relationship between both measurements was cervix2 = 0.842 × cervix1 (p ≤ 0.001, r = 0.950) while it was cervix2 = 0.971 × cervix1 in the group of women who remained undelivered (p ≤ 0.001, r = 0.987).

Fig. 1.

First and second cervical length measurement in women with threatened preterm labor. In the left image, the red dots indicate delivery within 14 days, in the right image delivery before 34 + 0 weeksʼ gestation. The green dots represent the measurements in pregnancies where delivery occured after the respective time end points.

Comparison of different regression models

Univariate logistic regression analysis indicates a significant correlation between delivery within 14 days of presentation as well as delivery before 34 weeks and both the first and second cervical length measurements as well as the difference between the two measurements (Table 1).

Table 1 Univariate logistic regression to predict preterm delivery within 14 days after the first examination and before 34 weeksʼ gestation.

| Delivery within 14 days | Delivery before 34 wks | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95 % CI | p | OR | 95 % CI | p | |

| Maternal age (yrs) | 0.990 | 0.910–1.077 | 0.526 | 1.022 | 0.954–1.095 | 0.535 |

| Nullipara (n) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Previous preterm delivery < 37 wks (n) | 3.459 | 0.986–12.137 | 0.053 | 1.257 | 0.343–4.612 | 0.730 |

| Previous term but no preterm delivery (n) | 0.925 | 0.277–3.088 | 0.899 | 0.848 | 0.339–2.125 | 0.726 |

| Weight (kg) | 0.999 | 0.963–1.037 | 0.959 | 1.001 | 0.972–1.031 | 0.930 |

| No cigarette smoking | 1 | |||||

| Cigarette smoking | 1.004 | 0.126–8.025 | 0.997 | 1.693 | 0.217–13.243 | 0.616 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dl) | 1.133 | 0.775–1.655 | 0.520 | 1.048 | 0.732–1.501 | 0.796 |

| White blood cell count (n/µl) | 1.000 | 1.000–1.000 | 0.567 | 1.000 | 1.000–1.000 | 0.804 |

| No bacterial vaginosis | 1 | |||||

| Bacterial vaginosis | 0.604 | 0.165–2.213 | 0.447 | 0.748 | 0.243–2.301 | 0.613 |

| Gestational age at first Cx length measurement (wks) | 1.205 | 0.933–1.462 | 0.060 | 0.887 | 0.779–1.010 | 0.070 |

| First Cx measurement (mm) | 0.900 | 0.837–0.968 | <0.005 | 0.884 | 0.831–0.940 | <0.0 001 |

| Gestational age at second Cx length meaurement (wks) | 1.040 | 0.966–1.120 | 0.295 | 1.036 | 0.968–1.109 | 0.313 |

| Second Cx measurement (mm) | 0.868 | 0.808–0.933 | <0.0 001 | 0.865 | 0.815–0.919 | <0.0 001 |

| Difference between first and second Cx measurement (mm) | 0.843 | 0.753–0.944 | 0.003 | 0.887 | 0.805–0.978 | 0.016 |

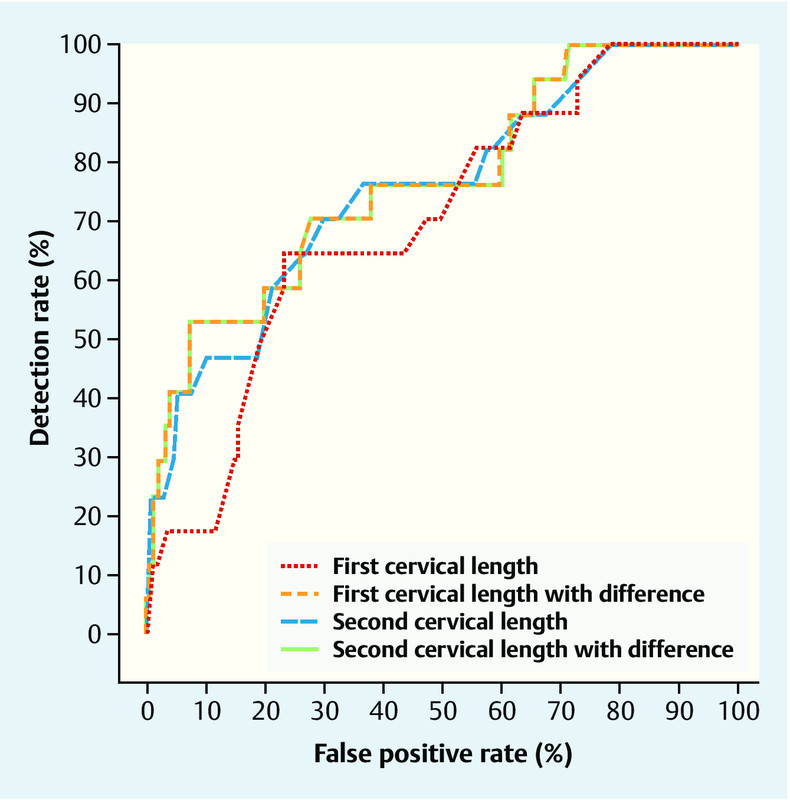

Fig. 2 contains ROC curves for the prediction of preterm birth within 14 days based on the first and second cervical length measurement with and without the difference between both measurements. The ROC curves are based on the multiple regression analysis as shown in Table 2. It can be clearly seen that the addition of the difference between both measurements improves the model up to a false positive rate of 20 %. At a false positive rate of 10 % – which corresponds to a first and second cervical length of 10 and 9 mm – the detection rate was 17.6 % with the first cervical length measurement, 47.0 % with the second and 52.9 % if the difference between both measurements is added to the first or the second cervical length.

Fig. 2.

ROC curve analysis for a delivery witihin 14 days. The models are based on the results shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Logistic regression models in the prediction of preterm delivery within 14 days and before 34 weeksʼ gestation. In the first two models, either the first or the second cervical length measurement is used. In the third and fourth model the difference between both measurements is added to the first or second measurement.

| Delivery within 14 days | Delivery before 34 wks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | p | Estimate | p | |

| First cervical length | ||||

| Constant | − 0.252 | 0.660 | − 0.152 | 0.580 |

| Cervical length | − 0.218 | < 0.0001 | 0.247 | < 0.0001 |

| Second cervical length | ||||

| Constant | − 0.708 | 0.156 | − 0.115 | 0.790 |

| Cervical length | − 0.141 | < 0.0001 | − 0.145 | < 0.0001 |

| First cervical length and difference between both measurements | ||||

| Constant | − 1.169 | 0.002 | − 0.325 | 0.517 |

| Cervical length | − 0.120 | 0.001 | − 0.132 | < 0.0001 |

| Difference | − 0.219 | 0.048 | − 0.163 | 0.004 |

| Second cervical length with difference between both measurements | ||||

| Constant | − 1.157 | 0.053 | − 0.220 | 0.680 |

| Cervical length | − 0.121 | 0.002 | − 0.025 | < 0.0001 |

| Difference | − 0.097 | 1.146 | − 0.220 | 0.662 |

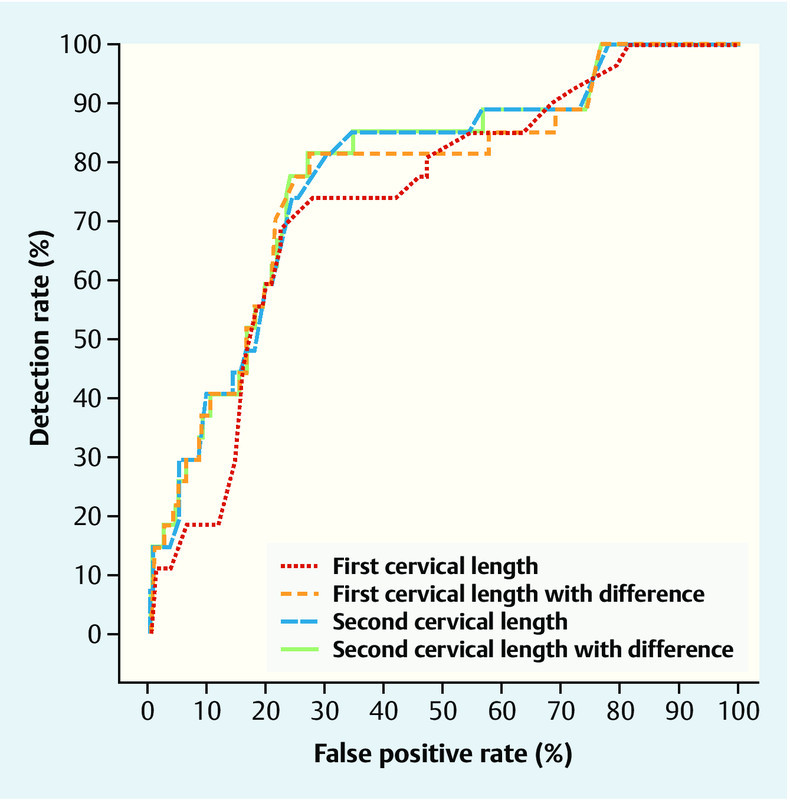

Similarly, the ROC curve analysis for the prediction of preterm birth before 34 weeks indicates that, up to a false positive rate of 20 %, the model based on the first cervical length measurement can be improved by taking into account the difference between the measurements (Fig. 3, Table 2). However, the model based on the second cervical length measurement does not improve with the addition of the difference between measurements. At a false positive rate of 10 %, the detection rate was 18.5 % with the first cervical length measurement and 29.6 % if the difference is added. The detection rate for the second measurement was also 29.6 % and remained unchanged if the difference was added.

Fig. 3.

ROC curve analysis for a delivery before 34 weeksʼ gestation. The models are based on the results shown in Table 2.

Discussion

In this study we have shown that in women with threatened preterm labor a repeat measurement some days after the first cervical length measurement is helpful to predict the further course of the pregnancy. This is particularly the case in women with a cervical length of 10 mm or less.

Our data is consistent with results of several previously published studies that focused on the cervical length measurement in threatened preterm labor 2, 6, 10, 22, 23. Most studies have used a cut-off of 15 mm 15. Combined data from three studies that included 510 women with singleton pregnancies presenting in spontaneous preterm labour revealed that 49 % of women with a cervical length < 15 mm delivered within seven days of presentation whereas only 1 % did so if the cervical length was ≥ 15 mm 17. In an HTA report by Honest et al., the authors demonstrated that the risk for delivery within seven days of presentation was increased 8.6 fold if the cervical length was 15 mm or less. Alfirevic et al. took this concept a step further 22. They conducted a prospective multicenter study where women with preterm contractions were divided into two arms. In one arm, a transvaginal ultrasound cervical measurement was performed and if the cervical length was more than 15 mm, they were managed expectantly without corticosteroids administration. Patients in the control arm were managed based on clinical assessment without sonographic cervical assessment 16. The study was designed to evaluate the ability of the two approaches to identify women who will or will not deliver within seven days of presentation. The authorsʼ focus was on the resultant appropriate versus unnecessary corticosteroid administration. They found that only 14 % received an unnecessary course of corticosteroids in the study arm, which compared favourably with the control group where 90 % received corticosteroids unnecessarily.

In women who do not deliver within the first 2–3 days of admission, a second cervical measurement or the change between the two measurements may improve our ability to predict the risk of subsequent delivery. In our study, the ROC curve analysis showed that up to a false positive rate of about 20 % the second cervical length measurement performed better than the first one. Combination of the first or second cervical length measurement with the difference between both measurements was better than a single measurement alone. Sotiriadis et al. examined 122 women with preterm contractions and measured the cervix twice, at presentation and after 24 hours. They also found that the positive predictive value of the first cervical length measurement was increased by adding the difference between both measurements 15. Rozenberg et al. examined 109 patients with threatened preterm labor at presentation and 48 hours later. They excluded women with a cervical length with more than 26 mm and women who delivered before a second measurement was performed 24. In their study, the authors did not observe a benefit of adding the difference between the two measurements to the risk calculation based on the first measurement alone. Fox et al. measured cervical length in asymptomatic women between 16 and 28 weeksʼ gestation. If the cervical length was less than 25 mm, they repeated the measurement three weeks later. They reported that decrease in cervical length correlated with earlier gestational age at delivery and with an increased proportion of women delivering before 37 weeksʼ gestation 23. Moroz et al. reported on 2695 asymptomatic women with consecutive cervical length measurements after a median time interval of four weeks 16. In the 250 women with a cervical length of less than 25 mm, for every one millimeter shortening, the risk for preterm delivery increased by 3 %.

The main limitation of our study is the retrospective character. Furthermore, although our study population is reasonably large, there are still only 17 and 27 women with preterm delivery within 14 days and before 34 weeks. The fact that most published studies include a smaller number of symptomatic women points to the need to perform a multi-center study in order to show significant differences.

Generally, most studies focus on a time interval of seven days rather than 14 days. However, as the second measurement was 3.6 days later, we felt that the second measurement would be too close to the point of interest. In addition, in view of the further management, it is not only important to know how the management within the next few days should look like but also to plan a step further.

Our data confirms that in patients with preterm contractions, the management depends on the cervical length measurement. The first cervical length measurement at the time of presentation is essential in terms of the short term management. However, if the pregnancy carries on for the next few days, a second cervical assessment is useful. Especially in those cases with a short cervix of 10 mm or less, the detection rate of a preterm delivery within the following days can be substantially improved by the second measurement and by taking into account the difference between both measurements.

Assessment of the cervical length is crucial in women presenting with preterm contractions. Our results indicate that it is worth to repeat the measurement some days later and to take into account the difference between both measurements.

Acknowledgements

The study was accredited by the Arbeitsgemeinschaft MaternoFetale Medizin.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None.

References

- 1.Kenyon S L, Taylor D J, Tarnow-Mordi W. Broad-spectrum antibiotics for spontaneous preterm labour: the ORACLE II randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;357:989–994. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04234-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Honest H, Forbes C A, Durée K H. et al. Screening to prevent spontaneous preterm birth: systematic reviews of accuracy and effectiveness literature with economic modelling. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13:1–627. doi: 10.3310/hta13430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deshpande S N, van Asselt A DI, Tomini F. et al. Rapid fetal fibronectin testing to predict preterm birth in women with symptoms of premature labour: a systematic review and cost analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2013;17:1–138. doi: 10.3310/hta17400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsoi E, Akmal S, Rane S. et al. Ultrasound assessment of cervical length in threatened preterm labor. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;21:552–555. doi: 10.1002/uog.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsoi E, Akmal S, Geerts L. et al. Sonographic measurement of cervical length and fetal fibronectin testing in threatened preterm labor. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;27:368–372. doi: 10.1002/uog.2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wulff C B, Ekelund C K, Hedegaard M. et al. Can a 15-mm cervical length cutoff discriminate between low and high risk of preterm delivery in women with threatened preterm labor? Fetal Diagn Ther. 2011;29:216–223. doi: 10.1159/000322131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palacio M, Sanin-Blair J, Sánchez M. et al. The use of a variable cut-off value of cervical length in women admitted for preterm labor before and after 32 weeks. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;29:421–426. doi: 10.1002/uog.3950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuchs I B, Henrich W, Osthues K. et al. Sonographic cervical length in singleton pregnancies with intact membranes presenting with threatened preterm labor. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;24:554–557. doi: 10.1002/uog.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kagan K O, Sonek J. How to measure cervical length. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;45:358–362. doi: 10.1002/uog.14742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sotiriadis A, Papatheodorou S, Kavvadias A. et al. Transvaginal cervical length measurement for prediction of preterm birth in women with threatened preterm labor: a meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;35:54–64. doi: 10.1002/uog.7457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hiersch L, Yogev Y, Domniz N. et al. The role of cervical length in women with threatened preterm labor: is it a valid predictor at any gestational age? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:5320–5.32E11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.To M S, Skentou C A, Royston P. et al. Prediction of patient-specific risk of early preterm delivery using maternal history and sonographic measurement of cervical length: a population-based prospective study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;27:362–367. doi: 10.1002/uog.2773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iams J D. Cervical length–time to report the rate of change? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:443. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naim A, Haberman S, Burgess T. et al. Changes in cervical length and the risk of preterm labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:887–889. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.123058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sotiriadis A, Kavvadias A, Papatheodorou S. et al. The value of serial cervical length measurements for the prediction of threatened preterm labour. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;148:17–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moroz L A, Simhan H N. Rate of sonographic cervical shortening and the risk of spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:2340–2.34E7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kagan K O, To M, Tsoi E. et al. Preterm birth: the value of sonographic measurement of cervical length. BJOG. 2006;113 03:52–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flenady V Wojcieszek A M Papatsonis D NM et al. Calcium channel blockers for inhibiting preterm labour and birth Cochrane Database Syst Rev 20146CD002255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts D Dalziel S Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth Cochrane Database Syst Rev 20063CD004454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bomba-Opon D A, Kosinska-Kaczynska K, Kosinski P. et al. Vaginal progesterone after tocolytic therapy in threatened preterm labor. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25:1156–1159. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2011.629014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Areia A, Fonseca E, Moura P. Progesterone use after successful treatment of threatened pre-term delivery. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;33:678–681. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2013.820266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alfirevic Z, Allen-Coward H, Molina F. et al. Targeted therapy for threatened preterm labor based on sonographic measurement of the cervical length: a randomized controlled trial. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;29:47–50. doi: 10.1002/uog.3908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fox N S, Jean-Pierre C, Predanic M. et al. Short cervix: is a follow-up measurement useful? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;29:44–46. doi: 10.1002/uog.3902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rozenberg P, Rudant J, Chevret S. et al. Repeat measurement of cervical length after successful tocolysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:995–999. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000143254.27255.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]