Abstract

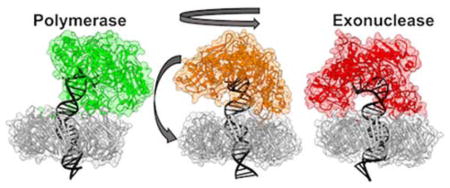

Replicative DNA polymerases (Pols) frequently possess two distinct DNA processing activities – DNA synthesis (polymerization) and proofreading (3′–5′ exonuclease activity). The polymerase and exonuclease reactions are performed alternately and are spatially separated in different protein domains. Thus, the growing DNA primer terminus has to undergo dynamic conformational switching between two distinct functional sites on the polymerase. Furthermore, the transition from polymerization (pol) to exonuclease (exo) mode must occur in the context of a DNA Pol holoenzyme, wherein the polymerase is physically associated with the processivity factor Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA) and primer-template DNA. The mechanism of this conformational switching and the role that PCNA plays in it had remained obscure, largely due to the dynamic nature of the ternary Pol/PCNA/DNA assemblies. Here, we present computational models of the ternary assemblies for the archaeal polymerase PolB. We have combined all available structural information for the binary complexes with electron microscopy (EM) data and have refined atomistic models for the ternary PolB/PCNA/DNA assemblies in the pol and exo modes using molecular dynamics simulations. In addition to the canonical PIP-box/inter-domain connector loop (IDCL) interface of PolB with PCNA, contact analysis of the simulation trajectories revealed new secondary binding interfaces, distinct between the pol and exo states. Using targeted molecular dynamics (TMD), we explored the conformational transition from pol to exo mode. We identified a hinge region between the thumb and palm domain of PolB that is critical for conformational switching. With the thumb domain anchored onto the PCNA surface, the neighboring palm domain executed rotational motion around the hinge, bringing the core of PolB down toward PCNA to form a new interface with the clamp. A helix from PolB containing a patch of arginine residues was involved in the binding, locking the complex in the exo-mode conformation. Together, these results provide a structural view of how the transition between the pol and exo states of PolB is coordinated through PCNA to achieve efficient proofreading.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Genome duplication and maintenance are critically dependent on the function of DNA polymerases1–2 that catalyze the template-dependent incorporation of deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) to extend the 3′ end of a DNA primer strand. In addition to this rapid and accurate polymerization activity many polymerases also possess 3′–5′ exonuclease activity (proofreading or editing), which allows the removal of misincorporated nucleotides from the nascent DNA.1, 3 The fact that the polymerization and proofreading active sites are spatially separated within the polymerase (by at least 20 Å in different Pol structures4–7) suggests a switching mechanism must exist to transfer the primer terminus from one site to the other.8

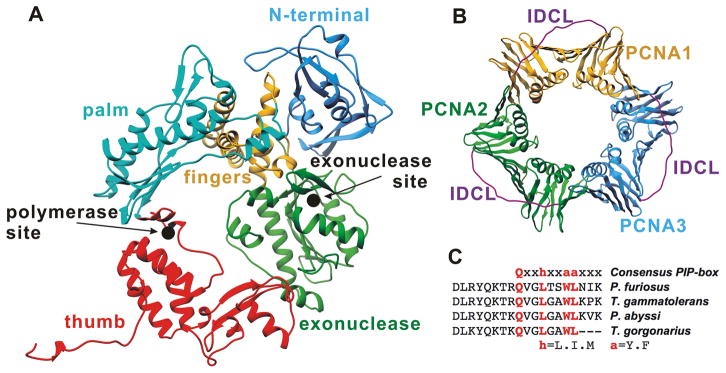

Pyrococcus furiosus PolB belongs to the archaeal family-B DNA polymerases, which share a common architecture comprised of five protein domains – the fingers, palm, thumb, N-terminal, and exonuclease domains (Figure 1A).4–5, 9–12 In PolB the switch from pol to exo activity is accompanied by large conformational changes of both the polymerase and DNA, as evident from crystal structures of PolB in the replication and editing modes. While structures of archaeal PolB/DNA complexes in pol and exo mode exist, details of the switching mechanism have remained elusive. Moreover, during replication PolB functions as part of a holoenzyme complex and, therefore, conformational switching occurs in the context of a ternary PolB/PCNA/DNA assembly. The trimeric processivity clamp PCNA encircles duplex DNA as a closed ring (Figure 1B) and serves as a mobile platform for DNA polymerase to act on DNA, thereby ensuring processive replication.13–17 PolB’s association with PCNA is essential for full PolB activities.15, 18

Figure 1. Structures of the individual components of the DNA polymerase holoenzyme assembly.

(A) Structure of the archaeal DNA polymerase PolB from Pyrococcus furiosus; and (B) structure of the cognate processivity clamp protein PCNA. Approximate positions of the exonuclease and polymerase active sites are shown by black filled circles. (C) A sequence alignment of the C-terminal regions of four archaeal polymerases highlights the conserved PIP-box motif.

The ring-shaped PCNA clamp is asymmetric, with a front and back face. Most PCNA binding partners associate to the front face of the clamp.13, 15, 18 PCNA-interacting proteins commonly include a conserved sequence termed PCNA-interacting protein motif (PIP-box) within their flexible tail regions, which binds a hydrophobic patch on the PCNA front face beneath an inter-domain connector loop (IDCL) (Figure 1B). The PIP-box/IDCL interaction confers the primary affinity for binding to the clamp.15–16, 19–20 Consistent with this notion, disruption of the PolB PIP-box interaction results in substantial loss of enzymatic activity in both the pol and exo modes.21 Different PCNA partner proteins feature similar PIP motifs, which localize to the same sites on the clamp surface.15, 18 Therefore, the PIP-box interaction alone achieves only simple tethering to the clamp and is insufficient to ensure active orientation for core replication proteins (e.g. PolB). Emerging evidence suggests a critical role for secondary interfaces with PCNA in attaining functional complexes.22–26 By locking the Pol enzyme in an optimal orientation, these contacts regulate access to the substrate.

Residue contacts from such secondary interfaces (E171(PCNA)–K706(PolB) in pol mode and E171(PCNA)–R380(PolB) in exo mode) were previously identified from low-resolution EM structural models and functional assays involving mutants of Pyrococcus furiosus (Pfu) PolB.20, 27 Since these contacts are mutually exclusive between the pol and exo states, they have been proposed to modulate the conformational transition from polymerization to proofreading. In this contribution we provide structural models of the PolB/PCNA/DNA ternary complexes in the pol and exo functional states. We then analyze the complete PolB/PCNA secondary interfaces beyond the two previously tested residue pairs. We employ TMD to compute a low free energy path connecting the pol and exo functional states. Finally, we delineate the large-scale conformational dynamics of the Pol ternary complexes underlying the switch from polymerase to exonuclease function.

METHODS

Initial model construction

To create an initial model of PolB/PCNA/DNA in pol-mode we combined two high-resolution binary structures: PCNA/PolB and PolB/DNA (PDB accession codes 3A2F and 4AIL).5, 20 The 4AIL structure captured PolB in polymerization mode. The binary structures were superimposed on the thumb domain of PolB (residues D636 to G750). The DNA duplex exiting the polymerization active site of PolB was extended through the central cavity of PCNA.

To create an initial model of PolB/PCNA/DNA in exo-mode we first constructed a Pfu PolB/DNA homology model with the program Modeller.28–29 The closely related structure of Pyrococcus abyssi DNA polymerase was used as template (PDB accession code 4FLV; 83% sequence identity and 97% sequence similarity).4 The PolB orientation with respect to the sliding clamp was modeled starting with the binary structure PolB/PCNA (3A2F). Next, we used a 19-Å negative stain EM reconstruction of the Pfu PolB/PCNA/DNA complex (EMDB accession code emd-5220) to re-position the polymerase to the experimentally observed exo mode conformation.27 Preliminary rigid body fitting was performed with UCSF Chimera.30

Molecular Dynamics Simulation

Hydrogen atoms were added to the models with the tleap module of AMBER 9.31–32 Sidechain ionization states at pH 7.0 were assigned using the WHATIF webserver.33 Each system was solvated with TIP3P water molecules34 with a minimum distance of 10.0 Å from the surface atoms of the complex to the edge of the periodic simulation box. Counter-ions were added to neutralize the net charge of the complex and reach 100 mM NaCl concentration to mimic physiological conditions.

Energy minimization was conducted for 5000 steps with fixed backbone atoms followed by another 5000 steps with harmonic restraints on the backbone atoms (k = 25 kcal/mol Å2). The temperature of the simulated systems was then gradually raised to 300 K over 200 ps in the NVT ensemble. To relax the orientation of the DNA duplex in the ternary complexes, the systems were equilibrated with secondary structure restraints imposed for 4 ns. Additionally, during the pol mode system equilibration, positional restraints were placed on select residues at the PolB/PCNA interface (R706, K724 and K725 from PolB, E171, D96, L99 from PCNA) to ensure these contacts were maintained. For the exo mode ternary complex, initial equilibration was followed by a 20-ns molecular dynamics flexible fitting (MDFF) run to fit PolB into the emd-5220 EM density map.35–36 In MDFF, an external biasing potential UEM is introduced and forces derived from the gradient of the EM density are applied to drive the atoms into the high-density regions:

| (1) |

| (2) |

Here wj is a weighting factor for atom j of coordinate rj; ϕ(r) is the potential converted from the EM density; and ξ is a scaling factor. To prevent secondary structure distortions, bond, angle and dihedral angle restraints were imposed on the well-defined secondary structure regions as determined by DSSP.37 The MDFF bias was applied in stages with progressively higher values of the scaling factor ξ in the range 0.01 to 0.1. Convergence was assessed by monitoring root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) and the cross-correlation coefficient of the original EM density with a computed density map based on the atomic model. The DNA substrate was excluded from the application of MDFF-derived external forces because the DNA was incompletely resolved in the original EM density.

Subsequently, 200-ns production runs for each system were carried out in the isothermal isobaric ensemble (p = 1 atm and T = 300 K). We used the smooth particle mesh Ewald (SPME) algorithm38 to calculate long-range electrostatic forces. A cutoff distance of 10 Å and a switching function at 8.5 Å were employed to evaluate the short-range non-bonded interactions. The MD integration time step was 2 fs. The SHAKE algorithm was used to constrain the bonds involving hydrogen atoms and, thus, to eliminate the highest frequency oscillatory motions. The r-RESPA multiple time step method39 was employed with a 2-fs time step for bonded and short-range non-bonded interactions and 4-fs time step for the electrostatic interactions. The simulations were carried out with the NAMD 2.9 code40–41 and the AMBER Parm99SB force field 42 and corrected parameters for nucleic acids dihedrals (BSC0).43 Data were analyzed using the PTRAJ code in AMBER44 and TCL scripts in VMD.45

Targeted Molecular Dynamics

To accelerate the conformational transition of PolB/PCNA/DNA from pol to exo-mode we carried out targeted molecular dynamics (TMD) runs applying a time-dependent, harmonic energy bias to the backbone atoms of the system.46 In TMD, as a reference RMSD value to a final structure at time t is monotonically decreased over the course of the simulation, the system is gradually driven toward the target structure. The starting configuration was the ternary complex in pol mode and the target configuration was our MDFF-fitted exo mode model. The harmonic force constant k was varied in the range from 200 to 800 kcal mol−1 Å−2 and short TMD trial runs were completed to establish the minimal perturbation necessary to efficiently carry out the conformational transition. In the end, a value of 600 kcal mol−1 Å−2 was chosen for the 21-ns TMD production run.

Binding Energy Decomposition

MM/GBSA energy decomposition47–48 was carried out to pinpoint residues (1-D decomposition) and residue pairs (2-D decomposition) contributing significantly toward the PolB-PCNA interface binding energy. In MM/GBSA we selected and sampled 1000 conformations from the last 100 ns of the MD trajectories. Binding free energies (ΔGb) were determined from the equation:

where ΔEMM is the gas-phase MM binding energy; ΔGsol and ΔS are the changes upon binding of the solvation free energy and gas-phase entropy, respectively. The electrostatic contribution to ΔGsol can be computed through a Generalized Born (GB) model, which approximates the solution of the Poisson-Boltzmann equation.49–50 For the GB calculation we used an internal dielectric constant of 2 and an external dielectric constant of 80 (for aqueous solvent). The non-polar contribution to ΔGsol was computed from the equation:

where γ and b were set to 0.0072 kcal mol−1 Å−2 and 0 kcal mol−1. MolSurf in AMBER 932 was employed to compute the solvent-accessible surface area using a 1.4 Å probe radius, the optimized set of atomic radii in AMBER and the ff99SB42 atomic charges.

Elastic Network Model Path

In the Path-elastic network model (Path-ENM) method,51 elastic networks are constructed for two end state structures (denoted initial and final). Each structure is coarse-grained into nodes, typically centered on the Cα atoms for proteins or P atoms for nucleic acids. The potential energy of the elastic network is given by interaction terms of the form:

where is the instantaneous position vector of the node coordinates, is the corresponding vector for the equilibrium positions of the nodes (determined from the initial or final structure), C is a force constant, Rc is the pre-defined distance cutoff and dij and are the current and equilibrium distances between nodes i and j, respectively. These elastic interactions are added between pairs of nodes that fall within Rc to complete the network.52–53 A potential energy landscape between the elastic networks of the two end state structures is then constructed by combining their respective energy functions (E1 and E2).51

where β=1/kBT. The resulting path is comprised of structures interpolated along the steepest-descent path through the shared free energy landscape connecting the end points. Contributions to the path from individual ENM normal modes can be computed, yielding quantification of the specific motions contributing to the conformational transition. To determine the end states for Path-ENM, we clustered the pol and exo mode MD trajectories and selected the centroid of the most populated cluster from each trajectory to represent the pol and exo state, respectively. Path-ENM calculations were performed on the ENM web server, supported by the NIH.51

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Structural models for the PolB/PCNA/DNA assemblies in polymerization and editing mode

To delineate the conformational switching mechanism of Pfu PolB that allows it to transition from polymerization to editing activity on PCNA, we constructed models for the PolB/PCNA/DNA complexes in pol and exo mode. The ternary complex in pol mode was modeled by combining two existing binary structures: PCNA/PolB and PolB/DNA (PDB accession codes 3A2F and 4AIL, respectively).5, 20 In the 4AIL structure the primer terminus occupied the polymerization active site. Therefore, model construction required only extension of the DNA duplex through the central cavity of PCNA.

To create the exo-mode model we first constructed a Pfu PolB/DNA homology model based on the structure of Pyrococcus abyssi DNA polymerase (PDB accession code 4FLV).4 In this structure the DNA primer terminus was observed to extend into the exonuclease active site of the enzyme. P. abyssi and P. furiosus are closely related and share 83% sequence identity. The highly conserved sequences make homology modeling very reliable in this case. The PolB orientation with respect to the sliding clamp was modeled starting with the binary structure PolB/PCNA (3A2F). In this structure PolB binds the clamp through its C-terminal PIP-box, assuming an upright orientation in the periphery of the PCNA ring. We used MDFF to re-position the PolB catalytic core to the orientation experimentally observed in exo mode. The quality of the EM map enabled unambiguous fitting of the five PolB domains and positioning of the enzyme core on the front face of the PCNA clamp. The DNA coming out of the PolB exonuclease domain was extended to pass through the PCNA ring.

The models were refined in two separate 200-ns molecular dynamics runs. Structural convergence was monitored though the time evolution of root-mean-square deviation values (RMSD) for the backbone atoms. Since RMSD was found to plateau in the second half of the trajectories (Figure S1), we performed clustering analysis on the last 100 ns from each simulation. We selected the centroid structures of the most dominant clusters as final models for the ternary complexes. Models for the ternary assemblies PolB/PCNA/DNA in the two functional states are presented in Figure 2. Both models show identical positioning of the primer end as in the original structures (3A2F and 4FLV) and exhibit no steric hindrance between the sliding clamp and DNA (Figure 2A, 2B). The models highlight the large-scale structural reorganization that the PolB assembly must undergo to transition from polymerization to proofreading.

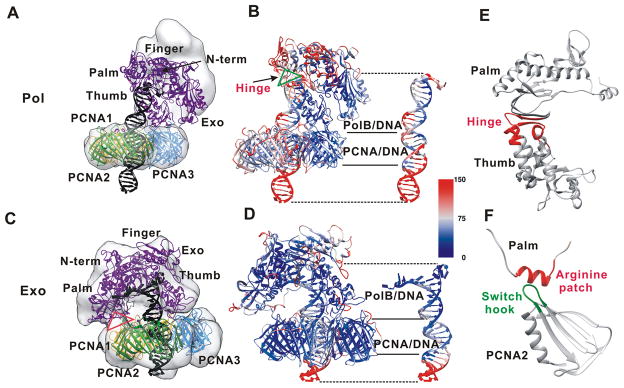

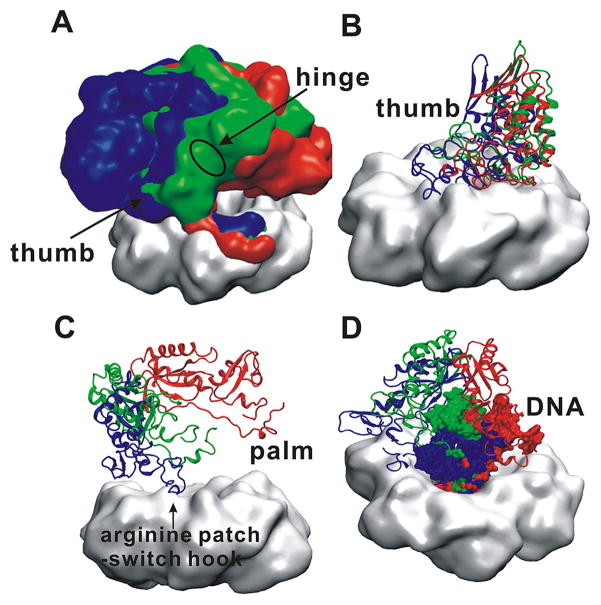

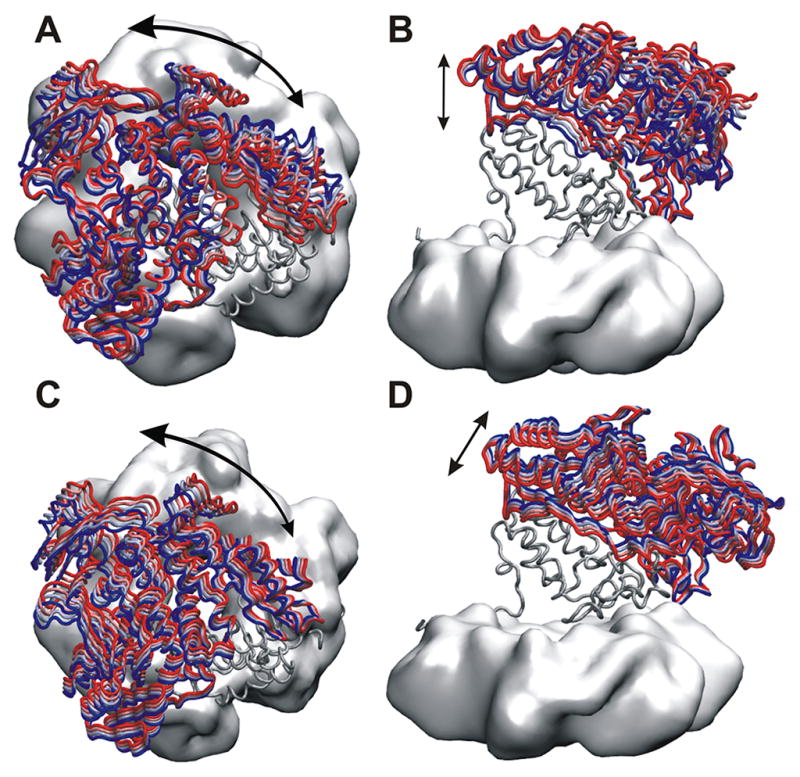

Figure 2. Pseudoatomic models of the PolB holoenzyme in polymerization and editing mode.

Comparison of the ternary PolB/PCNA/DNA complexes (shown in cartoon representation) in (A) pol mode and (B) exo mode. The gray surface indicates the initial MD conformation for the pol mode model or the EM density for the exo mode model. Computed B-factors mapped onto the structures of the holoenzyme complexes in (C) pol mode and (D) exo mode. B-factor values are color-coded from high (red) to low (blue). (E) The hinge region between the thumb and palm domains of PolB is shown in red and its approximate location within the complex is marked with a green triangle and black arrow. (F) The contact between the arginine patch helix from PolB and the negative “switch-hook” loop from PCNA is shown and its approximate location within the complex is marked with a red triangle.

In polymerization mode, PolB is anchored to PCNA by the thumb domain, resulting in an upright orientation with respect to the plane of the ring-shaped clamp (Figure 2A). Notably, this orientation is different from the initial PolB/PCNA structure depicted as gray surface in Figure 2A. Previous structural work had indicated that DNA polymerases could adopt varying positions with respect to their cognate processivity clamps. Three models have been proposed: (i) an inactive “locked-down” conformation observed in the complex of E.coli translesion polymerase pol IV with the β clamp;54 (ii) an intermediate “standby” state, wherein the polymerase is held upright on the front face of PCNA without covering the central cavity of the clamp; and (iii) a catalytically competent “tethered” state wherein the polymerase fully covers the central cavity of the clamp.6–7 Only the tethered state allows substrate DNA to pass through the PCNA ring without steric clashes. The starting point for our pol mode simulation was in the inactive “standby” state.20 By contrast, in our MD simulations the “tethered” state was predominant. In the tethered state PolB is productively oriented toward the DNA duplex, adopting a tilted conformation that partially obscures the central cavity of PCNA (Figure 2A). Two of the three PCNA subunits were found to contact PolB in this conformation.

In the exo state simulation PolB adopted a horizontal orientation with respect to the PCNA ring, completely covering the front face of the clamp. All three PCNA subunits were found to engage with PolB. The observed tighter association of PolB to PCNA occurred through the formation of new interactions between the PolB palm domain and the PCNA2 subunit (Figure 2B, 2F). These interactions involved a helix from PolB containing a patch of arginine residues (R379, R380, and R382) previously shown to be important for exonuclease activity on PCNA.27 The arginine patch binds to a conserved negatively charged loop on the PCNA surface denoted as the “switch-hook” (proximal to PCNA residue E171).

The computed B-factors presented in Figure 2C and 2D allow us to assess the flexibility of the constituents of the ternary complexes. The B-factors were calculated on a per residue basis over the last 100 ns of the two simulation trajectories. Comparison of panels 2C and 2D clearly shows that the exo-mode complex is much less mobile than the pol-mode complex, which is also reflected in the RMSD profiles for each of the simulated systems (Figure S1). For the pol-mode complex the overall RMSD converges more slowly and exhibits more pronounced fluctuations. In both pol and exo modes PCNA is rigid (average internal RMSD of 3.23±0.14 Å, 2.50±0.16 Å, respectively) serving as a scaffold for the entire assembly. PolB and substrate DNA show greater flexibility (PolB RMSD of 3.38±0.17 Å in pol mode and 4.05 ± 0.18 Å in exo mode; DNA RMSD of 4.12±0.28Å in pol mode and 5.29±0.21 Å in exo mode). The thumb domain, excluding the extreme C-terminal end (residues F749 to S775), is also rigid as it anchors PolB to the surface of the processivity clamp (1.87±0.23 Å average internal RMSD). The other domains of PolB are mobile in the pol state and participate in large-scale swinging motions of the enzyme core above the PCNA ring. Specifically, a flexible hinge region between the thumb and palm domain, encompassing residues 595-612, 630-640 and 746-752, is largely responsible for the lateral swing motion of the PolB fingers, N-terminal and exonuclease domains. The position of the hinge region is highlighted in Figure 2C and 2E.

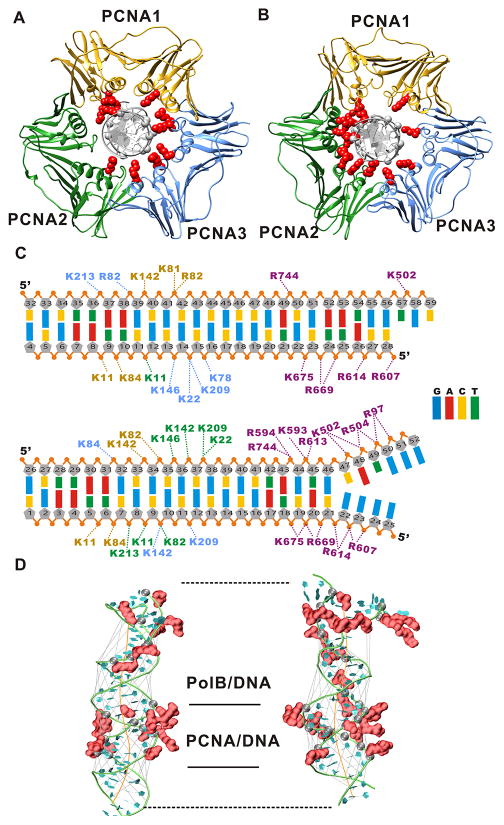

In the editing mode PolB is clamped down onto the PCNA surface forming interfaces with all three PCNA subunits. In this arrangement, PolB displays only minimal surface loop motions. The average RMSD of PolB after RMS fitting to PCNA is 2.57 ± 0.61 Å (versus 3.66 ± 1.08 Å in pol mode). From the computed B-factors the DNA substrate is also less mobile in the exo mode, making greater number of contacts with the positively charged inner cavities of PolB and PCNA. The clamp protein and the polymerase are tethered to DNA through multiple direct or water-mediated salt bridge contacts between positive (R, K) residues and DNA backbone phosphates (denoted N-P contacts). Comparative analysis of persistent N-P contacts in pol versus exo mode revealed considerable differences in DNA/PCNA and DNA/PolB binding (Figure 3). DNA binds PCNA asymmetrically in both functional states. In pol mode, the DNA duplex is positioned at the interface of the subunits PCNA1 and PCNA3. Except for residue K11, the PCNA2 subunit does not form salt bridge contacts with the DNA backbone (Figure 3A, 3C). In contrast, in exo mode PCNA2 interacts strongly with DNA through 7 salt bridge interactions (Figure 3B, 3C). The repositioning of the PolB core during the conformational switch from polymerization to proofreading naturally forces the duplex DNA to tilt from one side of the PCNA central cavity to the other side. Notably, PolB-DNA association in exo mode is stronger overall compared to pol mode as judged by the number of persistent salt bridge contacts (7 versus 18) (Figure 3C and 3D). The greater number of N-P contacts in the exo state reflects the continuous tracking of the DNA minor groove by arginine and lysine residues upon exit from the central cavity of PCNA (Figure 3D). In contrast, the pol mode exhibits two primary sets of contacts separated by a gap (Figure 3C and 3D). This difference is functionally significant: in polymerization mode, PolB must be mobile to processively incorporate new nucleotides in a growing primer strand, while in the proofreading mode the ternary complex needs to pause to let the ssDNA end to transition into the exonuclease active site. Less structural flexibility for the ternary complex in exo mode would facilitate such functional pausing.

Figure 3. PolB and PCNA engage the primer-template DNA in two distinct orientations corresponding to the pol and exo modes.

(A) Binding mode of PCNA to the DNA substrate in pol mode; and (B) binding mode of PCNA to the DNA substrate in exo mode. The PCNA1 subunit is colored in gold, PCNA2 in green, PCNA3 in blue. Phosphodiester groups from the DNA and basic residues from PCNA involved in persistent contacts (present in more than 50% of trajectory frames) are shown as gray spheres and red surfaces, respectively. (C) All persistent salt-bridge contacts to the DNA are listed explicitly for pol mode (upper panel) and exo mode (lower panel). Residue labels are colored by the corresponding subunit color. (D) Structures of the DNA duplex from the pol mode (left), and the exo mode (right) simulations. The DNA is shown in ribbons representation. The DNA axis and the widths of major or minor grooves were computed with the program Curves+ and are shown in orange and gray lines respectively.

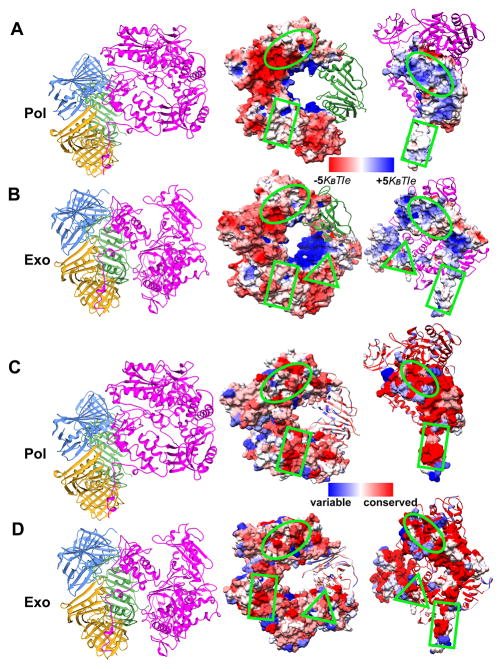

Secondary interfaces with PCNA determine the functional orientation in pol and exo modes

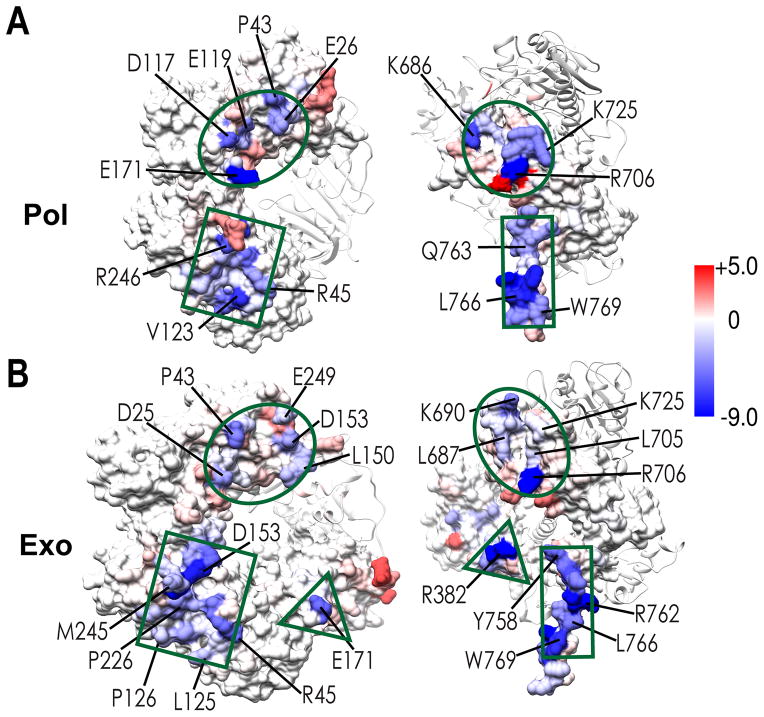

The MD models for the PolB/PCNA/DNA pol and exo complexes are pseudo-atomic. Unlike high-resolution crystal structures, these models cannot identify all interfacial contacts with perfect accuracy. However, it is still worthwhile to examine the MD results in terms of residue contacts. Notably, the MD-derived secondary PolB-PCNA interfaces (Figure 4) are: 1) energetically stable (GBSA binding energies of −69.47 and −83.65 kcal/mol for pol and exo mode, respectively); 2) electrostatically compatible (Figure 4A and 4B); 3) involve areas of PCNA and PolB with high sequence conservation (Figure 4C and 4D); and 4) match known experimental evidences. Therefore, the computationally identified binding interfaces/residue contacts constitute the best available structural framework to guide future mutational experiments designed to map out interactions that mediate pol-to-exo conformational switching in PolB.

Figure 4. Secondary PolB/PCNA interfaces are critical for the conformational switch from polymerization to editing.

Surface electrostatics of the PolB/PCNA interfaces in (A) pol mode and (B) exo mode. The electrostatic potential was mapped onto the molecular surface and colored from red (negative) to blue (positive potential). PCNA and PolB conservation maps are shown in two orientations, corresponding to (C) pol mode and (D) exo mode. The PCNA and PolB molecular surfaces are rendered according to conservation, with highly conserved regions in red, semi-conserved regions in white, and non-conserved regions in blue. PCNA sequences from A. fulgidus, S. solfataricus, T. kodakarensis, T. onnurineus, T. gammatolerans, T. fumicolans, T. paralvinellae, P. yayanosii, P. abyssi, P. horikoshii, P. furiosus and PolB sequences from T. kodakarensis, T. gorgonarius, T. gammatolerans, T. guaymasensis, P. glycovorans, P. abyssi, P. furiosus were aligned using ClustalW. The approximate locations of the three distinct PolB/PCNA interfaces are shown in green as a circle, rectangle and triangle.

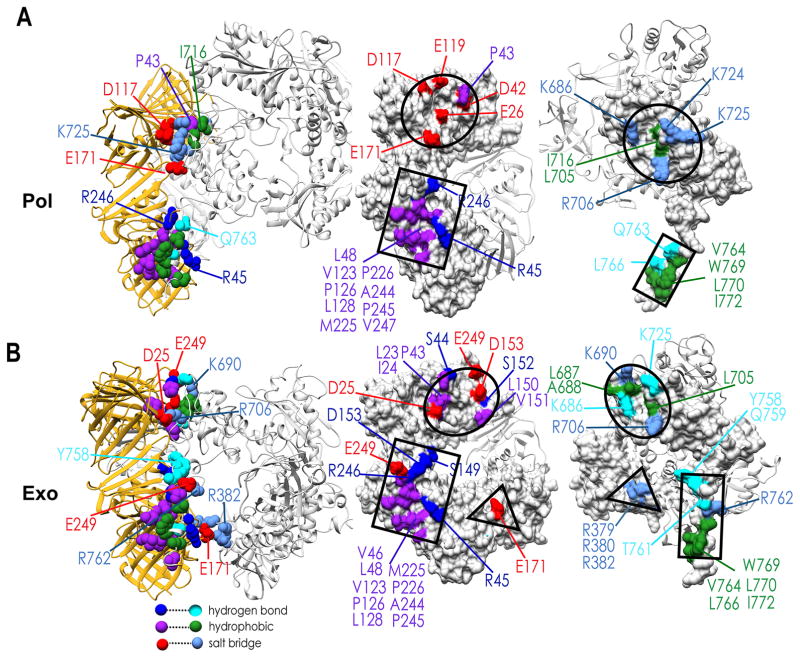

We used geometric criteria to analyze the PolB-PCNA contacts (H-bond, salt-bridge and hydrophobic interactions) throughout the production phase of the MD trajectories. Interactions that occurred in less than 50% of the trajectory frames were considered transient. In Figure 5 we present the persistent interfacial residue contacts in pol and exo mode, respectively. The long C-terminal tail of PolB makes stable contacts with a hydrophobic patch on PCNA1 close to the IDCL. This cluster of hydrophobic contacts (centered on residues L766, W769, L770) remains invariant in both pol and exo mode (Figure 5). While the PolB PIP-box serves as the primary hydrophobic anchor to the PCNA surface, it is tethered to the polymerase core by a flexible linker starting at residue Q759(PolB). By stretching, the linker can tolerate variable orientations of PolB with respect to the sliding clamp, allowing the pol-to-exo mode switch to occur without any disruption of the PIP-box/IDCL interface. In pol mode, productive positioning of the PolB core is primarily determined by an interface between the thumb domain and PCNA3 (Figure 5A and Movie S1). Five persistent salt-bridges and a hydrogen bond interaction are formed at this interface – K686(PolB)-D42(PCNA3), K724(PolB)-E119(PCNA3), K725(PolB)-D117(PCNA3), R706(PolB)-E171(PCNA1), and R706(PolB)-E26(PCNA3) (Figure 5). Notably, the R706-E171 salt bridge (previously identified to be critical to the polymerization activity20) was observed with 90.8% occupancy over the pol mode trajectory. Additionally, a small hydrophobic core centered on residue P43 from PCNA and I716, L705 from PolB strengthens the stability of this interface. In exo mode (Figure 5B and Movie S2), this interface slightly rearranges to include two hydrophobic clusters (residues L23, I24, P43 from PCNA contacting L705 from PolB; residues L150, V151 from PCNA contacting L687, A688 from PolB), three salt-bridges (K690(PolB)-E249 (PCNA3), R706(PolB)-D25(PCNA3), R762(PolB)-E249(PCNA1)) and four persistent hydrogen bonds (R706(PolB)-S21(PCNA3), Y758(PolB)-S149(PCNA1), Q759(PolB)-D153(PCNA1), L766(PolB)-R45(PCNA1)). The primary difference between the pol and exo modes is the formation of a new interface in exo mode between the palm domain of PolB and the PCNA2 subunit. Notably, the energetically favorable interactions of R379, R380 and R382 in the palm domain and E171 from PCNA2 are consistent with the previously reported importance of the arginine patch in maintaining full exonuclease activity of PolB in the ternary complex.27 To delineate the specific residue contacts that may affect the PolB-PCNA interface stabilities, the GBSA binding free energies for the two holoenzyme complexes were decomposed into individual (Table S1) and pairwise residue contributions (Table S2). Residue contributions from the 1D decomposition were color mapped onto the structures of the ternary complexes in pol and exo mode, respectively (Figure 6). The figure highlights the same regions on the molecular surfaces of PCNA and PolB that were identified by computing the persistent contacts. However, it also adds a quantitative estimate of the per residue binding energy allowing to differentiate and rank the residues/contacts by relative importance. The results underscore the importance of salt bridges in addition to hydrophobic interactions in determining both the interface stabilities and the functional orientation of PolB in pol and exo modes.

Figure 5. Computationally identified contact maps in pol and exo mode constitute the best available structural framework to guide future mutational experiments.

Residue contact maps in (A) pol mode; and (B) exo mode, respectively. Salt-bridge interactions are shown in light blue and red; hydrogen bonding interactions (other than salt-bridge) are shown in cyan and dark blue; hydrophobic interactions are shown in green and purple. The approximate locations of the three distinct PolB/PCNA interfaces are shown in black as a circle, rectangle and triangle.

Figure 6. Binding energy contributions from individual residues at the PolB/PCNA interfaces.

Per residue binding energies computed from the one-dimensional MM/GBSA decomposition are shown in pol mode (A) and exo mode (B). Residues are colored according to the value of the binding energy in kcal/mol from red (positive) to blue (negative). The approximate locations of the three distinct PolB/PCNA interfaces are shown in green as a circle, rectangle and triangle.

Transition from Polymerization to Editing Mode

Given that DNA polymerization occurs on the millisecond timescale, conformational switching of PolB from polymerization to editing mode occurs on a timescale that cannot be sampled by direct MD simulations. To overcome this timescale limitation, we used targeted molecular dynamics (TMD) to drive the transition between the two functional states of the holoenzyme complex. TMD offers a straightforward and computationally efficient way to explore the large-scale conformational changes on the path connecting the pol and exo states. While TMD is likely to explore a low-energy pathway,55–57 it is not a path optimization method and does not guarantee a minimum free-energy path connecting the two states. Indeed, judicious choice of the force constant k is required to avoid high free energy intermediates or unphysical states along the path. With these caveats in mind, we chose the minimal possible force constant that was effective in promoting the pol-to-exo transition. Figure 7 and Movies S3, S4 and S5 present a structural view of the path explored in the TMD simulation. Qualitatively, the path can be recapitulated as a simple rotational motion of the PolB core (palm, N-terminal, fingers and exonuclease domains) around the thumb domain, which is stably bound to the clamp surface. With the thumb domain anchored onto PCNA, the adjacent palm domain executed a 56° rotational motion around a hinge region comprised of residues 595-612, 630-640, 746-752 (Movie S4). This motion eventually brings the arginine patch helix of PolB into contact with the negatively charged “switch hook” loop of PCNA2. The “arginine patch” – “switch hook” interaction serves to latch the complex in exo mode. The primer-template DNA does not separate (opening of the last three base pairs) until the latter stages of the TMD simulation (at approximately 16 ns from the 21-ns TMD simulation), and the template DNA strand continuously tracks the long loop region (residues 383-396) of the palm domain (Figure 7D and Figure S2). Upon separation from the template, the primer end transitions to the opposite side of the PolB central cavity to interact with the exonuclease domain.

Figure 7. Targeted molecular dynamics identifies a low free energy pathway connecting the pol and exo states of the holoenzyme complex.

The pathway is represented by overlaid structures selected from the initial (red), middle (green) and final (blue) segment of the TMD trajectory. (A) Side view of the complex in surface representation; (B) Side view of the PCNA (gray surface) with the PolB thumb domain (cartoon representation); (C) View of the rotation of the PolB palm domain (cartoon representation) with respect to PCNA (gray surface); and (D) the DNA substrate (surface representation) tracking the rotational motion of the palm domain (cartoon representation).

To identify the large-scale collective motions of the polymerase core within the ternary complexes, we employed principal component analysis (PCA). The PCA method involves: 1) computing the covariance matrix over all backbone protein and nucleic acid atoms from the MD trajectories; 2) diagonalizing the matrix to yield eigenvectors and eigenvalues (i.e. principal modes and mean square fluctuations); 3) projecting the trajectory onto the principal modes to yield principal components. By reducing the dimensionality of the trajectory data, PCA analysis recapitulates the most important dynamical features from MD. The first few principal components are of special significance as they capture slow, large-amplitude motions, which often constitute the most important dynamical features of the system. In our PCA results, the first two PCA modes account for 48% of the motion observed in the pol-mode trajectory and 39% of the motion observed in the exo-mode trajectory. The first two principal modes for the pol-mode PolB/PCNA/DNA model are shown in Figure 8 (denoted as PCA1 and PCA2). The PCA1 mode represents a horizontal twisting motion of PolB above the ring of PCNA (Figure 8A). PCA2 represents vertical swing motion of the PolB toward the front face of PCNA (Figure 8B). The coarse grain ENM path (Movie S6) closely resembles the TMD pathway and can be reconstituted as a combination of normal modes. The two lowest normal modes of the pol-mode complex provided the largest contribution to the computed path (Figure S3). Specifically, a slanted, vertical swinging motion occupies the lowest frequency mode (Figure 8D), with an in-plane twisting motion corresponding to the second-lowest frequency normal mode (Figure 8C). These motions are consistent with the two lowest PCA modes. The Path-ENM analysis data indicates that the pol to exo mode transition passes through a saddle point wherein PolB is tilted over PCNA, partially occluding the central pore, but has not yet formed the exo mode contacts necessary to maintain the exo conformation. This evidence further supports the necessity for the formation of secondary contacts to switch the ternary complex from pol to exo mode.

Figure 8. Results from PCA and Path-ENM analysis recapitulate the PolB core rotation as a combination of two low-frequency global motions.

(A) Motion along the first principal component PCA1 in pol mode; (B) Motion along the second principal component PCA2 in pol mode; (C) Motion along the second normal mode from an elastic network model of the holoenzyme in pol mode; (D) Motion along the first normal mode from an elastic network model of the holoenzyme in pol mode. Structures displaced along the direction of each mode were generated and visualized sequentially from red to blue.

CONCLUSIONS

Our structural models provide critical insights into the regulation of PoB by its cognate processivity clamp. Importantly, our results reveal the nature of the molecular motions, which balance DNA polymerization and proofreading activities in the context of the holoenzyme complex formed by PolB, PCNA and DNA. Previous mechanistic proposals for how the conformational switching occurs in this system had emphasized the role of the PIP-box/PCNA interaction13–14 and the fact that substrate DNA exits the polymerase at different angles7, 20 in exo versus pol mode. This difference in the orientation of the DNA duplex led to the proposal that pol-to-exo mode switching must involve rotation of PolB pivoted on the PCNA subunit harboring the PIP-motif interface. Two secondary interfaces were suggested to orient the polymerase core. The first interaction site (in pol mode) involved residue R706 from PolB and residue E171 from the PCNA1 subunit. The second interaction site (in exo mode) involved the arginine patch and the “switch-hook” loop from the adjacent PCNA2 subunit. Contacts at these two sites are mutually exclusive. The model proposed that PolB could undergo rotation about the axis connecting the PIP-box and the first interaction site to convert from the “standby” to the “tethered” state. The pol-to-exo transition would also use the PIP contact as a pivot but rotation would occur around a different (perpendicular) axis to allow the DNA primer to access the exonuclease active site.20 Here we show that the PIP-box interface and the core of PolB are connected by a fully flexible linker and, therefore, the pol-to-exo switching motion cannot be pivoted at the PIP-box. While the canonical PIP-box/IDCL interaction serves as the primary hydrophobic anchor of PolB to PCNA, it provides only simple tethering. To achieve functional orientation in the ternary complex PolB relies on secondary interfaces with the PCNA subunits, more substantial than the two experimentally proposed contact pairs. We identified specific contacts within these secondary interfaces, which showed both electrostatic complementarity and sequence conservation. Therefore, our work defines a structural framework for future mutational studies to map out the functionally important PolB – PCNA interactions. Our work also leads to an alternative model wherein the thumb domain stably anchors PolB onto the front face of the sliding clamp in both functional states. To smoothly transition from polymerization to editing, the core of the polymerase (palm, fingers, N-terminal and exonuclease domains) executes a 56° rotation pivoted at a hinge region located between the PolB thumb and palm domains. This brings the core of PolB down toward the surface of PCNA until the PolB helix containing the arginine patch encounters the negatively charged “switch hook” loop on PCNA, locking the complex in the exo-mode conformation. Both PCA and Path-ENM results recapitulate the rotational motion from TMD primarily as a combination of two low frequency global motions – the in-plane twisting of the PolB core above the PCNA ring and the downward swing of the PolB palm domain to form a set of stabilizing contacts secondary to the canonical PIP-box interface. Collectively, these results imply that the pol-to-exo mode transition is a fundamental dynamic feature intrinsic to the global collective motions of the PolB/PCNA/DNA holoenzyme complex.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Science Foundation CAREER award MCB-1149521 and National Institute of Health grant R01GM110387 to I.I.. X.X. and B.K. were supported by a Molecular Basis of Disease fellowship. Computational resources were provided in part by a National Science Foundation XSEDE allocation CHE110042 and through an allocation at NERSC supported by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science contract DE-AC02-05CH11231.

Footnotes

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website. Supplementary figures showing: (i) RMSD profiles from the MD simulations; (ii) the structural transition of DNA in the PolB holoenzyme during TMD; and (iii) normal mode contributions to the path-ENM pathway. Supplementary movies showing (i) PolB-PCNA contact interfaces in pol and exo modes; and (ii) the structural transition from pol to exo mode from TMD and path-ENM calculations. Supplementary tables showing results from per-residue (1D) and pairwise (2D) binding energy decomposition. Atomic models of the PolB holoenzyme complexes in polymerization and exonuclease mode in PDB format.

References

- 1.Benkovic SJ, Valentine AM, Salinas F. Replisome-Mediated DNA Replication. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:181–208. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burgers PMJ. Eukaryotic DNA Polymerases in DNA Replication and DNA Repair. Chromosoma. 1998;107:218–227. doi: 10.1007/s004120050300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joyce CM, Benkovic SJ. DNA Polymerase Fidelity: Kinetics, Structure, and Checkpoints. Biochemistry. 2004;43:14317–14324. doi: 10.1021/bi048422z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gouge J, Ralec C, Henneke G, Delarue M. Molecular Recognition of Canonical and Deaminated Bases by P. Abyssi Family B DNA Polymerase. J Mol Biol. 2012;423:315–336. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wynne SA, Pinheiro VB, Holliger P, Leslie AG. Structures of an Apo and a Binary Complex of an Evolved Archeal B Family DNA Polymerase Capable of Synthesising Highly Cy-Dye Labelled DNA. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70892. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shamoo Y, Steitz TA. Building a Replisome from Interacting Pieces: Sliding Clamp Complexed to a Peptide from DNA Polymerase and a Polymerase Editing Complex. Cell. 1999;99:155–166. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81647-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franklin MC, Wang J, Steitz TA. Structure of the Replicating Complex of a Pol Alpha Family DNA Polymerase. Cell. 2001;105:657–667. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00367-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kunkel TA. DNA Replication Fidelity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16895–16898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hopfner KP, Eichinger A, Engh RA, Laue F, Ankenbauer W, Huber R, Angerer B. Crystal Structure of a Thermostable Type B DNA Polymerase from Thermococcus Gorgonarius. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:3600–3605. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao Y, Jeruzalmi D, Moarefi I, Leighton L, Lasken R, Kuriyan J. Crystal Structure of an Archaebacterial DNA Polymerase. Structure. 1999;7:1189–1199. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)80053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hashimoto H, Nishioka M, Fujiwara S, Takagi M, Imanaka T, Inoue T, Kai Y. Crystal Structure of DNA Polymerase from Hyperthermophilic Archaeon Pyrococcus Kodakaraensis Kod1. J Mol Biol. 2001;306:469–477. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim SW, Kim DU, Kim JK, Kang LW, Cho HS. Crystal Structure of Pfu, the High Fidelity DNA Polymerase from Pyrococcus Furiosus. Int J Biol Macromol. 2008;42:356–361. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krishna TS, Kong XP, Gary S, Burgers PM, Kuriyan J. Crystal Structure of the Eukaryotic DNA Polymerase Processivity Factor PCNA. Cell. 1994;79:1233–1243. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelman Z. PCNA: Structure, Functions and Interactions. Oncogene. 1997;14:629–640. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maga G, Hubscher U. Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA): A Dancer with Many Partners. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3051–3060. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moldovan GL, Pfander B, Jentsch S. PCNA, the Maestro of the Replication Fork. Cell. 2007;129:665–679. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ivanov I, Chapados BR, McCammon JA, Tainer JA. Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen Loaded onto Double-Stranded DNA: Dynamics, Minor Groove Interactions and Functional Implications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:6023–6033. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jonsson ZO, Hubscher U. Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen: More Than a Clamp for DNA Polymerases. Bioessays. 1997;19:967–975. doi: 10.1002/bies.950191106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warbrick E. The Puzzle of PCNA’s Many Partners. Bioessays. 2000;22:997–1006. doi: 10.1002/1521-1878(200011)22:11<997::AID-BIES6>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishida H, Mayanagi K, Kiyonari S, Sato Y, Oyama T, Ishino Y, Morikawa K. Structural Determinant for Switching between the Polymerase and Exonuclease Modes in the PCNA-Replicative DNA Polymerase Complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2009;106:20693–20698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907780106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tori K, Kimizu M, Ishino S, Ishino Y. DNA Polymerases Bi and D from the Hyperthermophilic Archaeon Pyrococcus Furiosus Both Bind to Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen with Their C-Terminal PIP-Box Motifs. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:5652–5657. doi: 10.1128/JB.00073-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayanagi K, Kiyonari S, Saito M, Shirai T, Ishino Y, Morikawa K. Mechanism of Replication Machinery Assembly as Revealed by the DNA Ligase-PCNA-DNA Complex Architecture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4647–4652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811196106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Querol-Audi J, Yan C, Xu X, Tsutakawa SE, Tsai MS, Tainer JA, Cooper PK, Nogales E, Ivanov I. Repair Complexes of Fen1 Endonuclease, DNA, and Rad9-Hus1-Rad1 Are Distinguished from their PCNA Counterparts by Functionally Important Stability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:8528–8533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121116109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tainer JA, McCammon JA, Ivanov I. Recognition of the Ring-Opened State of Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen by Replication Factor C Promotes Eukaryotic Clamp-Loading. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:7372–7378. doi: 10.1021/ja100365x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsutakawa SE, Van Wynsberghe AW, Freudenthal BD, Weinacht CP, Gakhar L, Washington MT, Zhuang Z, Tainer JA, Ivanov I. Solution X-Ray Scattering Combined with Computational Modeling Reveals Multiple Conformations of Covalently Bound Ubiquitin on PCNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:17672–17677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110480108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsutakawa SE, Yan C, Xu X, Weinacht CP, Freudenthal BD, Yang K, Zhuang Z, Washington MT, Tainer JA, Ivanov I. Structurally Distinct Ubiquitin- and Sumo-Modified PCNA: Implications for Their Distinct Roles in the DNA Damage Response. Structure. 2015;23:724–733. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayanagi K, Kiyonari S, Nishida H, Saito M, Kohda D, Ishino Y, Shirai T, Morikawa K. Architecture of the DNA Polymerase B-Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA)-DNA Ternary Complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:1845–1849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010933108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marti-Renom MA, Stuart AC, Fiser A, Sanchez R, Melo F, Sali A. Comparative Protein Structure Modeling of Genes and Genomes. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2000;29:291–325. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sali A. Comparative Protein Modeling by Satisfaction of Spatial Restraints. Mol Med Today. 1995;1:270–277. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(95)91170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera - a Visualization System for Exploratory Research and Analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Case DA, Darden T, Cheatham TE, III, Simmerling C, Wang J, Duke RE, Luo R, Merz KM, Pearlman DA, Crowley M, et al. Amber 9. University of California; San Francisco: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Case DA, Cheatham TE, Darden T, Gohlke H, Luo R, Merz KM, Onufriev A, Simmerling C, Wang B, Woods RJ. The Amber Biomolecular Simulation Programs. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:1668–1688. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vriend G. What If: A Molecular Modeling and Drug Design Program. J Mol Graph. 1990;8:52–56. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(90)80070-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura1 JD, Impey WL, Klein ML. Comparison of Simple Potential Functions for Simulating Liquid Water. J Chem Phys. 1983;79:10. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trabuco LG, Villa E, Mitra K, Frank J, Schulten K. Flexible Fitting of Atomic Structures into Electron Microscopy Maps Using Molecular Dynamics. Structure. 2008;16:673–683. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trabuco LG, Villa E, Schreiner E, Harrison CB, Schulten K. Molecular Dynamics Flexible Fitting: A Practical Guide to Combine Cryo-Electron Microscopy and X-Ray Crystallography. Methods. 2009;49:174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kabsch W, Sander C. Dictionary of Protein Secondary Structure: Pattern Recognition of Hydrogen-Bonded and Geometrical Features. Biopolymers. 1983;22:2577–2637. doi: 10.1002/bip.360221211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Essmann U, Perera L, Berkowitz ML, Darden T, Lee H, Pedersen LG. A Smooth Particle Mesh Ewald Method. J Chem Phys. 1995;103:8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tuckerman M, Berne BJ, Martyna GJ. Reversible Multiple Time Scale Molecular Dynamics. J Chem Phys. 1992;97:1990–2001. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kale L, Skeel R, Bhandarkar M, Brunner R, Gursoy A, Krawetz N, Phillips J, Shinozaki A, Varadarajan K, Schulten K. NAMD2: Greater Scalability for Parallel Molecular Dynamics. J Comput Phys. 1999;151:283–312. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, Chipot C, Skeel RD, Kale L, Schulten K. Scalable Molecular Dynamics with NAMD. J Comput Chem. 2005;26 doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hornak V, Abel R, Okur A, Strockbine B, Roitberg A, Simmerling C. Comparison of Multiple Amber Force Fields and Development of Improved Protein Backbone Parameters. Proteins. 2006;65:712–725. doi: 10.1002/prot.21123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perez A, Marchan I, Svozil D, Sponer J, Cheatham TE, Laughton CA, Orozco M. Refinenement of the Amber Force Field for Nucleic Acids: Improving the Description of Alpha/Gamma Conformers. Biophys J. 2007;92:3817–3829. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.097782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roe DR, Cheatham TE. Ptraj and Cpptraj: Software for Processing and Analysis of Molecular Dynamics Trajectory Data. J Chem Theory Comput. 2013;9:3084–3095. doi: 10.1021/ct400341p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: Visual Molecular Dynamics. J Mol Graph Model. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schlitter J, Engels M, Kruger P. Targeted Molecular Dynamics - a New Approach for Searching Pathways of Conformational Transitions. J Mol Graph. 1994;12:84–89. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(94)80072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gohlke H, Kiel C, Case DA. Insights into Protein-Protein Binding by Binding Free Energy Calculation and Free Energy Decomposition for the Ras-Raf and Ras-Ralgds Complexes. J Mol Biol. 2003;330:891–913. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00610-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller BR, McGee TD, Swails JM, Homeyer N, Gohlke H, Roitberg AE. MMPBSA.Py: An Efficient Program for End-State Free Energy Calculations. J Chem Theory Comput. 2012;8:3314–3321. doi: 10.1021/ct300418h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Still WC, Tempczyk A, Hawley RC, Hendrickson T. Semianalytical Treatment of Solvation for Molecular Mechanics and Dynamics. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:6127–6129. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Constanciel R, Contreras R. Self Consistent Field Theory of Solvent Effects Representation by Continuum Models: Introduction of Desolvation Contribution. Theoretica Chimica Acta. 1984;65:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zheng W, Brooks BR, Hummer G. Protein Conformational Transitions Explored by Mixed Elastic Network Models. Proteins. 2007;69:43–57. doi: 10.1002/prot.21465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zheng WJ. A Unification of the Elastic Network Model and the Gaussian Network Model for Optimal Description of Protein Conformational Motions and Fluctuations. Biophys J. 2008;94:3853–3857. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.125831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gorfe AA, Chang CE, Ivanov I, McCammon JA. Dynamics of the Acetylcholinesterase Tetramer. Biophys J. 2008;94:1144–1154. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.117879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tori K, Kimizu M, Ishino S, Ishino Y. DNA Polymerases B and D from the Hyperthermophilic Archaeon Pyrococcus Furiosus Both Bind to Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen with Their C-Terminal PIP-Box Motifs. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:5652–5657. doi: 10.1128/JB.00073-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marco E, Foucaud M, Langer I, Escrieut C, Tikhonova IG, Fourmy D. Mechanism of Activation of a G Protein-Coupled Receptor, the Human Cholecystokinin-2 Receptor. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:28779–28790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700349200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee HS, Robinson RC, Joo CH, Lee H, Kim YK, Choe H. Targeted Molecular Dynamics Simulation Studies of Calcium Binding and Conformational Change in the C-Terminal Half of Gelsolin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;342:702–709. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cheng XL, Wang HL, Grant B, Sine SM, McCammon JA. Targeted Molecular Dynamics Study of C-Loop Closure and Channel Gating in Nicotinic Receptors. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2:1173–1184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.