Abstract

Objective

Gallstone disease has been related to cardiovascular risk factors; however, whether presence of gallstones predicts coronary heart disease (CHD) is not well established.

Approach and Results

We followed 269,142 participants who were free of cancer and cardiovascular disease at baseline from 3 U.S. cohorts: the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS; 112,520 women; 1980–2010), NHS II (112,919 women; 1989–2011) and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS; 43,703 men; 1986–2010), and documented 21,265 incident CHD cases. After adjustment for potential confounders, the hazard ratio for the participants with a history of gallstone disease compared with those without was 1.15 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.10–1.21) in NHS, 1.33 (1.17–1.51) in NHS II, and 1.11 (1.04–1.20) in HPFS. The associations appeared to be stronger in individuals who were not obese, not diabetic, or were normotensive, compared to their counterparts. We identified 4 published prospective studies by searching PUBMED and EMBASE up to October 2015, coupled with our 3 cohorts, involving 842,553 participants and 51,123 incident CHD cases. The results from meta-analysis revealed a history of gallstone disease was associated with a 23% (15–33%) increased CHD risk.

Conclusions

Our findings support that a history of gallstone disease is associated with increased CHD risk, independently of traditional risk factors.

Keywords: coronary disease, gallstones, cohort study

INTRODUCTION

Gallstones are crystalline deposits in the gallbladder, principally formed by abnormal bile constituents (e.g., cholesterol, phospholipids, and bile salts). Gallstone disease is one of the most common and costly gastrointestinal disorders requiring hospitalization in the U.S.,1 affecting 5–25% adults in the Western world.2 Gallstone disease has been linked to diverse cardiovascular risk factors, such as obesity,3 diabetes4, 5 and metabolic syndrome.6, 7 In addition, patients with gallstones are characterized by distorted secretion of bile acids,8 which play a key role in regulating gut microbiota composition and activity.9, 10 Gut microbiota may influence a range of host functions related to cardiovascular risk,11–13 and metabolites produced by gut microbiota such as trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) and L-carnitine, have been directly linked with cardiovascular risk.11, 13–15

Several previous studies have related a history of gallstone disease to cardiovascular risk.16–18 However, some studies had short-term follow-up, did not confirm gallstone cases, or did not account for important covariates such as lifestyle and dietary habits. Notably, most of the previous studies were not conducted in the U.S population; and data from the US cohorts are lacking.

In the present study, we analyzed the relationship between a history of gallstone disease and risk of incident coronary heart disease (CHD) in 3 large prospective U.S. cohorts, followed for up to 30 years, and accounting for a wide spectrum of traditional risk factors. We performed several sensitive analyses to minimize the influence from potential reverse causation and confounding. We also conducted a systematic review of previously published studies, and meta-analyzed our results with the published data from other prospective cohorts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and Methods are available in the online-only Data Supplement.

RESULTS

At cohort-specific baselines, 14,023 participants out of 225,439 (6.2%) women (NHS and NHS II) and 1,449 out of 43,703 (3.3%) men (HPFS) reported a history of gallstone disease. Table 1 shows the characteristics of participants by cohort and gallstone status at cohort-specific baselines. Consistently across the 3 cohorts, participants who reported a history of gallstone disease were more likely to be older, current smokers, regular aspirin users, to be less physically active, to consume less alcohol, to have a higher BMI, and to have a history of hypertension, diabetes, or hypercholesterolemia (Table 1).

Table 1.

Age-Adjusted Baseline Characteristics of Participants from the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS; 112,520 women; 1980–2010), NHS II (112,919 women; 1989–2011) and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS; 43,703 men; 1986–2010)

| History of gallstone disease

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHS (1980) | NHS II (1989) | HPFS (1986) | ||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| N | 103,724 | 8796 | 107,692 | 5227 | 42,254 | 1449 |

| Age (years)* | 46.4 (7.2) | 48.6 (6.9) | 34.7 (4.7) | 36.4 (4.4) | 53.5 (9.6) | 60.1 (9.3) |

| White (%) | 96.7 | 98.2 | 95.4 | 96.8 | 90.7 | 90.9 |

| Married (%) | 74.0 | 78.2 | 77.3 | 77.9 | 90.1 | 90.7 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.2 (5.6) | 25.0 (6.9) | 23.9 (4.8) | 28.4 (7.0) | 25.5 (3.3) | 26.8 (3.9) |

| Physical activity (METs/week) | 14.2 (21.0) | 12.4 (19.0) | 25.0 (36.9) | 21.5 (33.2) | 21.4 (30.2) | 16.9 (24.1) |

| Premenopausal (%) | 57.5 | 49.7 | 97.3 | 93.0 | - | - |

| Current use of postmenopausal hormones (%) | 9.2 | 12.1 | 1.8 | 5.1 | - | - |

| Current smoking (%) | 26.7 | 30.9 | 13.2 | 17.8 | 9.5 | 11.7 |

| Hypertension (%) | 14.9 | 24.5 | 5.0 | 13.8 | 20.3 | 26.6 |

| Diabetes (%) | 2.0 | 4.7 | 0.8 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 4.6 |

| Hypercholesterolemia (%) | 4.8 | 7.4 | 10.1 | 17.0 | 10.7 | 14.0 |

| Family history of MI ≤60 years (%) | 18.3 | 21.3 | 14.5 | 19.8 | 12.1 | 11.8 |

| Regular aspirin use (%) | 32.1 | 37.3 | 11.0 | 13.5 | 27.0 | 30.0 |

| Daily energy intake (kcal/day) | 1566 (500) | 1563 (516) | 1789 (547) | 1797 (564) | 1995 (622) | 1989 (641) |

| Daily cholesterol intake (mg/day) | 336 (122) | 336 (127) | 242 (68) | 253 (73) | 305 (111) | 307 (102) |

| Alternative Health Eating Index Score | 47.8 (10.8) | 46.8 (10.6) | 58.7 (7.3) | 57.7 (7.3) | 44.3 (11.1) | 42.8 (10.8) |

| Alcohol intake (g/day) | 4.9 (9.7) | 4.0 (8.6) | 2.6 (5.7) | 1.7 (4.6) | 11.4 (15.5) | 8.4 (12.4) |

Values are means (SD) or percentages and are standardized to the age distribution of the study population. Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; HPFS, Health Professionals Follow-up Study; METs, metabolic equivalent task hours; MI, myocardial infarction; NHS, Nurses’ Health Study.

Value is not age adjusted.

Across up to 30 years of follow-up, we confirmed 21,265 incident CHD cases. In general, the crude incidence rates of total CHD were nearly double among participants who had reported gallstone disease compared with those who had never reported gallstone disease (Table 2). There was a significant age-adjusted association between a history of gallstone disease and CHD risk in each cohort. After multivariable adjustment, the associations between history of gallstones and CHD were largely attenuated but remained significant in each cohort: NHS (HR [95%CI]: 1.15 [1.10–1.21]), NHS II (1.33 [1.17–1.51]), and HPFS (1.11 [1.04–1.20]). An interim meta-analysis of these 3 cohorts revealed that the results in women (NHS and NHS II pooled HR [95%CI] 1.22 [1.06–1.41]) were not different from those in men (HPFS alone) (P for heterogeneity=0.23).

Table 2.

Cohort-Specific Hazard Ratios for Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in Relation to History of Gallstone Disease from the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS; 112,520 women; 1980–2010), NHS II (112,919 women; 1989–2011) and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS; 43,703 men; 1986–2010)

| NHS (1980–2010) | NHS II (1989–2011) | HPFS (1986–2010) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Gallstone Disease | Gallstone Disease | Gallstone Disease | ||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Total CHD | ||||||

| Cases/person years | 8425/2635977 | 2498/406551 | 1030/2155321 | 367/255359 | 8043/800863 | 902/51644 |

| rate/100k PY | 320/100k PY | 614/100k PY | 48/100k PY | 144/100k PY | 1004/100k PY | 1747/100k PY |

| Model 1 HR (95% CI), Age-adjusted | 1.00 | 1.51 (1.44–1.58) | 1.00 | 2.13 (1.88–2.40) | 1.00 | 1.26 (1.17–1.35) |

| Model 2 HR (95% CI), Multivariate-adjusted | 1.00 | 1.15 (1.10–1.21) | 1.00 | 1.33 (1.17–1.51) | 1.00 | 1.11 (1.04–1.20) |

| Fatal and nonfatal MI | ||||||

| Cases/person years | 3958/2495311 | 1119/373491 | 512/2164332 | 152/258078 | 3804/849167 | 511/58840 |

| rate/100k PY | 159/100k PY | 300/100k PY | 24/100k PY | 59/100k PY | 448/100k PY | 868/100k PY |

| Model 1 HR (95% CI), Age-adjusted | 1.00 | 1.53 (1.43–1.63) | 1.00 | 1.87 (1.56–2.25) | 1.00 | 1.25 (1.13–1.37) |

| Model 2 HR (95% CI), Multivariate-adjusted | 1.00 | 1.14 (1.05–1.22) | 1.00 | 1.15 (0.95–1.40) | 1.00 | 1.08 (0.98–1.19) |

| Revascularization | ||||||

| Cases/person years | 6463/2555486 | 2047/388159 | 789/2162836 | 309/256952 | 6416/806390 | 684/51863 |

| rate/100k PY | 253/100k PY | 527/100k PY | 36/100k PY | 120/100k PY | 796/100k PY | 1319/100k PY |

| Model 1 HR (95% CI), Age-adjusted | 1.00 | 1.60 (1.52–1.68) | 1.00 | 2.23 (1.95–2.55) | 1.00 | 1.28 (1.18–1.39) |

| Model 2 HR (95% CI), Multivariate-adjusted | 1.00 | 1.20 (1.13–1.26) | 1.00 | 1.35 (1.18–1.56) | 1.00 | 1.14 (1.05–1.24) |

Abbreviations: CHD, coronary heart disease; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratios; MI, myocardial infarction; PY, person-year.

Model 1, adjusted for age;

Model 2 adjusted for age (months); race (white/nonwhite); family history of MI (yes/no); marital status (married/not married); smoking status (never smoked, past smoker, current smoker); body mass index (kg/m2); physical activity (metabolic equivalent task hours/d in quintiles); diabetes (yes/no); hypertension (yes/no); hypercholesterolemia (yes/no); regular use of aspirin (yes/no); daily intake of alcohol (0, 0.1–5.0, 5.0–9.9, 10.0–14.9, ≥15.0 g/d), daily intake of the energy-adjusted dietary cholesterol (g/d in quintiles), 2010 Alternate Healthy Eating Index (score in quintiles), and daily energy intake (kcal/d in quintiles). In NHS and NHS II, menopausal status (yes/no), postmenopausal hormone uses (yes/no), and uses of oral contraceptive pills (yes/no) were also considered as covariates.

The number of cases and incidence rates for the secondary outcomes (fatal and nonfatal MI, and revascularization) does not equal the number of cases for the primary outcome (total CHD), because some participants experienced both MI and revascularization in the same period. For total CHD, the first of these events is considered the incident event at which follow-up ends.

When we limited the exposure to a history of cholecystectomy only, its association with total CHD risk was similar to when our definition of gallstone disease included both history of gallstones and cholecystectomy (data not shown). In secondary analyses of the total CHD subgroup definitions (fatal or nonfatal MI, and revascularization), multivariable-adjusted analyses of the individual outcomes revealed significant associations between a history of gallstone disease and MI in older women from NHS, but not in younger women from NHSII or men from HPFS (HR [95%CI] in NHS, 1.14 [1.05–1.22]; in NHS II, 1.15 [0.95–1.40]; and in HPFS, 1.08 [0.98–1.19]) (Table 2). Further exploratory analysis showed an attenuated and insignificant association (maybe due to a smaller sample size of the cases) between gallstone disease and fatal MI only (pooled HR [95%CI], 1.03 [0.93–1.15]). There were significant associations between a history of gallstone disease and revascularization in both women and men (HR [95%CI] in NHS, 1.20 [1.13–1.26]; in NHS II, 1.35 [1.18–1.56]; and in HPFS, 1.14 [1.05–1.24]) (Table 2).

The direct associations between gallstone disease and risk of CHD remained (HR [95% CI] for lagged analyses and baseline gallstone disease only, respectively, in NHS, 1.17 [1.12–1.23] and 1.17 [1.10–1.24]; in NHS II, 1.28 [1.11–1.47] and 1.24 [1.05–1.47]; and in HPFS, 1.15 [1.06–1.24] and 1.16[1.07–1.25]).

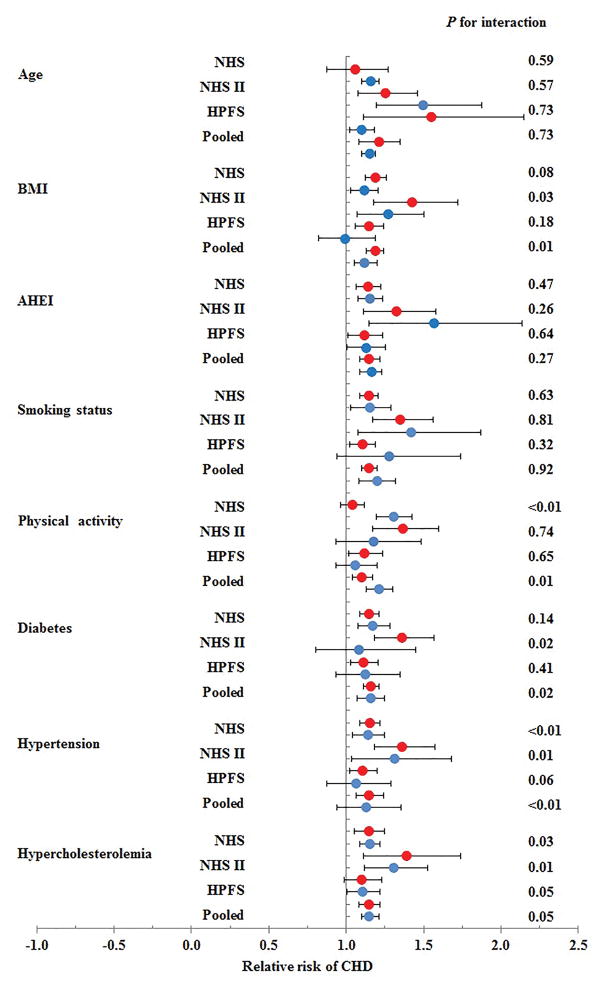

The results did not change materially when we evaluated the associations separately among participants not taking lipid-lowering medication (interim 3-cohort meta-analyzed HR [95%CI], 1.18 [1.10–1.27]), in those who were not obese (1.19 [1.13–1.24]), in those who were non-smokers (1.15 [1.10–1.20]), in those without diabetes (1.16 [1.11–1.21]), or in those with normal blood cholesterol levels (1.15 [1.08–1.22]). However, obesity status and disease status of diabetes and hypertension significantly modified the association between gallstone disease and CHD risk (all P for interaction <0.05, in the interim meta-analyses of our 3 cohorts; Figure 1). Participants with a history of gallstone disease who were not obese, or did not have diabetes or hypertension, seemed to have a greater increased risk of CHD compared to those participants who were obese, did have diabetes, or hypertension. Age, smoking, dietary quality, physical activity, or hyperlipidemia did not modify the association between history of gallstone disease and CHD. Although the pooled modification effect from physical activity is statistically significant, the direction differed across three cohorts. Therefore, we did not conclude physical activity modified the association between gallstone disease and CHD risk.

Figure 1.

Associations between history of gallstone disease and coronary heart disease risk stratified by age, obesity status, smoking status, diet, and physical activity. Red circles indicate the respective stratum with the lower risk values (age <55 years, BMI <30kg/m2, non-smoker, and Alternative Healthy Eating Index and physical activity less than the cohort-specific median value, with normal blood cholesterol levels, without diabetes, without hypertension). Blue circles indicate the respective stratum with the higher (presumably riskier) values (i.e., age ≥55 years, BMI ≥30kg/m2, smoker, AHEI and physical activity greater than or equal to the cohort-specific median value, with high blood cholesterol levels, with diabetes, with hypertension). Cox proportional hazards models were adjusted for include age (months); race (white/nonwhite); family history of MI (yes/no); marital status (married/not married); smoking status (never smoked, past smoker, current smoker); body mass index (kg/m2); physical activity (metabolic equivalent task hours/d in quintiles); diabetes (yes/no); hypertension (yes/no); hypercholesterolemia (yes/no); regular use of aspirin (yes/no); daily intake of alcohol (0, 0.1–5.0, 5.0–9.9, 10.0–14.9, ≥15.0 g/d), daily intake of the energy-adjusted dietary cholesterol (g/d in quintiles), 2010 Alternate Healthy Eating Index (AHEI score in quintiles), and daily energy intake (kcal/d in quintiles). In NHS and NHS II, menopausal status (yes/no), postmenopausal hormone uses (yes/no), and uses of oral contraceptive pills (yes/no) were also considered as covariates.

Results of Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

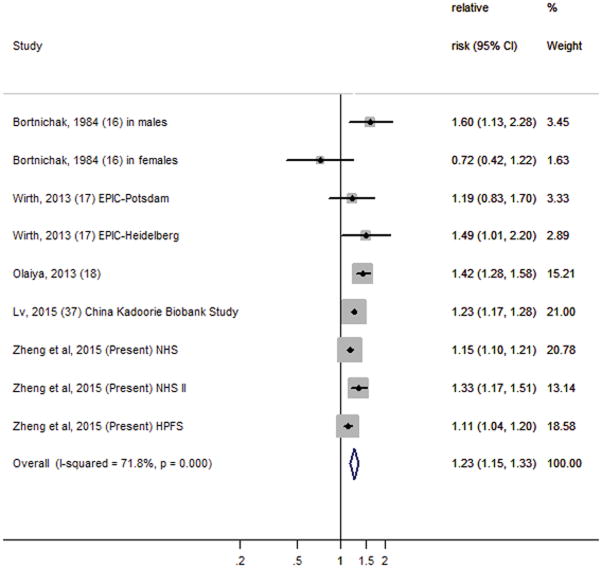

We also conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to incorporate the results of our 3 cohorts with previously published reports from prospective cohort studies. Our search of English-language articles resulted in 1,243 citations from PUBMED and 73 from EMBASE, with 16 duplicates. We screened the titles and abstracts using general inclusion criteria as described in the Detailed Methods (see Supplemental Material). We identified 52 abstracts for further full-text review, and eventually included four prospective cohorts for final meta-analysis. Together with the current study, a total of seven cohort studies were included in our meta-analysis. Characteristics of the seven prospective cohorts included in the meta-analysis are shown in Supplemental Table 1 (see Supplemental Material). We detected significant heterogeneity among these study results (I2=72%, P for homogeneity <0.01), which could be from a wide variation in study characteristics, such as study population, follow-up period, and measurements of gallstone disease and CHD. However, we were unable to detect the sources of heterogeneity because of a relatively small number of studies. Nevertheless, most studies showed directionally consistent associations between gallstone disease and CHD risk. Based on data from all cohort studies combined, including 842,553 participants and 51,123 incident cases of CHD, the pooled risk ratio from the random-effects model was 1.23 (95% CI, 1.15–1.33) for those with gallstone disease compared with those without gallstone disease (Figure 2). In meta-analysis, participants from our three internal cohorts with a history of gallstone disease had a 17% increased risk of CHD (HR, 1.17 [95%CI, 1.09–1.26]), while participants from external cohorts with a history of gallstone disease had a 30% increased risk of CHD (HR, 1.30 [95%CI, 1.15–1.47]). We also conducted sensitivity analyses excluding the only study that presented an odds ratio estimate,16 and the pooled risk ratio was 1.23 (95% CI, 1.15–1.33), indicating that the overall results were not influenced by this study. Neither visual inspection of the funnel plot (Supplemental Figure 1, see Supplemental Material) nor the Egger’s test (P=0.52) suggested publication bias.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the multivariate-adjusted risk ratio of coronary heart disease for history of gallstone disease in individual cohort studies and all studies combined in inverse weighted random-effects meta-analysis. Diamonds indicate point estimates; bars indicate 95% CIs; the size of the grey squares corresponds to the weight of the study in the meta-analysis. Abbreviations: EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition; HPFS, Health Professionals Follow-up Study; NHS, Nurses’ Health Study.

DISCUSSION

In our three prospective studies of 269,142 women and men, we found that a history of gallstone disease was associated with a 17% increased risk of CHD, independent of traditional risk factors. The associations were consistent in both men and women, and modified by obesity, and hypertension and diabetes status. Results from the meta-analysis incorporating previously published data from four additional prospective cohort studies further confirmed our findings.

One of the first reports on the relationship between gallstone disease and incident cardiovascular disease was by Bortnichak and colleagues in 1984,16 who found male gallstone patients were at an increased risk of incident CHD, while there was no such association in women. Significant associations between gallstone disease and CHD risk were also observed in cross-sectional studies,19, 20 and other prospective cohort studies in Asian21, 22 and German17 populations. The most recent and largest prospective study so far emerged from the China Kadoorie Biobank study,22 which involved 199,292 men and 288,081 women, followed for a median 7.2 years. Authors reported 23% higher risk of ischemic heart disease for participants with gallstone disease at baseline, as compared with those without the disease, which is an estimated risk consistent with our present results in the U.S. cohorts. As to other cardiovascular outcomes, both ultrasound-diagnosed gallstones and cholecystectomy were related to a 30% higher risk in overall mortality as well as 49% higher risk in cardiovascular mortality in a large U.S. population,23 and participants who had gallstone disease had a 28% higher risk in developing ischemic stroke and 33% higher risk in hemorrhagic stroke in a nation-wide study in Taiwan.24

Gallstone disease and CHD share many common risk factors, and it has been challenging to disentangle these shared risk factors from potentially causally-linked pathogenesis. Both diseases share multiple common traditional risk factors, including obesity,3 diabetes,4, 5 metabolic syndrome,6, 7 hypercholesterolemia,25 hypertension,25 and an unhealthy diet.26 In our analyses, the increased risk of incident CHD among gallstone patients was attenuated to a large degree but remained significant after we adjusted for these risk factors, and when we repeated main analyses among populations free of obesity, diabetes and hypertension, and among those with healthier lifestyle and dietary habits after stratifying by these factors. Our results were similar when we limited the disease to cholecystectomy, and it might suggest that cholecystectomy might not ameliorate the deleterious influence of gallstone diseases on CHD risk. Our observed associations were modified by obesity, diabetes, and hypertension status, with perhaps counter-intuitively stronger associations observed among the presumably healthier subsets of the population, i.e., those without obesity, diabetes, and hypertension. In addition, since cholesterol is the main component of most gallstones and atherosclerotic plaques, and the use of statins appears to prevent gallstone formation,27 we included hypercholesterolemia as a covariate in our statistical models and also conducted sensitivity analyses among the participants who had normal blood cholesterol levels, as well as among those not taking lipid-lowering medications, and yet the association of gallstone disease and CHD risk remained significant. Taken together, these observations may point to pathways independent of these important risk factors that link gallstone disease to CHD. Further research is warranted to explore potential mechanisms.

The potential mechanisms for the association of gallstone diseases with CHD may, at least, include the primary metabolic pathway and the bacterial pathway. Take an example in the metabolic pathway, among patients with gallstones, especially those with cholesterol gallstones, their bile acid and lecithin secretion rates tend to be depressed and cholesterol secretion rates elevated,28 which could indicate enhanced cholesterol synthesis and therefore increase CVD risk. In the bacterial pathway, gut microbiota dysbiosis may directly link gallstone disease to CHD risk. The presence of gallstones is related to microbiota dysbiosis in gut and biliary tract (maybe via biotransformation of secondary bile acids),10, 29 e.g., an overgrowth of the bacterial phylum Proteobacteria.10 At the same time, gut microbiota dysbiosis is found to be linked to a wide range of metabolic disturbances, including an increased risk of obesity and CVD.11–13, 28–30 Of note, the bacterial link may be a targeted pathway through which diets influence both diseases. For example, circulating TMAO, which is a gut flora-generated metabolite of red meat intakes, inhibits bile acid transporters in mouse liver and at the same time promotes atherosclerosis.31

Our results indicate the gallstone patients who were not affected by obesity, diabetes, or hypertension had a greater increased CHD risk compared to those who were affected by these diseases. The underlying mechanisms remained to be further explored. Patients with obesity, diabetes, or hypertension had a higher absolute risk of CHD; therefore, the increased risk attributable to gallstone disease might be relative less than those without these diseases. In addition, patients with obesity, diabetes and hypertension might modify their lifestyle to be healthier after disease diagnosis, and such modifications might also attenuate the relation between gallstone and CHD.

Although the present study may not be able to prove a causal relationship between gallstone disease and CHD, the long-term implications of gallstone disease on heart health are important in clinical practice.30 Patients with gallstone disease should be recommended a multidisciplinary program based on a careful assessment of coexisting cardiometabolic risk factors. Statins have been shown to dissolve cholesterol gallstones, suggesting their potential for a pharmacological therapy for gallstones beyond their well-known benefits on CHD prevention.27 However, randomized clinical trials are warrant to test the effect of statins on gallstone disease to more clearly address this issue.30

Strengths and limitations

The major strengths of the present study included the large sample size and well-characterized study populations. Results of the four-year lag sensitivity analysis and analysis minimize the possibility of reverse causality. We also incorporated previously published prospective cohort studies in a meta-analysis to explore the repeatability and generalizability of our results. Nevertheless, our results need to be interpreted in the context of several potential limitations. First, the assessment of gallstone disease in our cohorts was self-reported. However, validation studies in our populations have confirmed that gallstones and history of cholecystectomy were reported with high accuracy (99%) according to validation of medical records. 32,33 Second, we did not measure in our cohorts insulin resistance or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, which could be important mediators of the reported associations. This limited our ability to explore underlying molecular mechanisms or pathways. However, our results were similar among participants reporting normal blood lipid levels.

Conclusions

In summary, we observed that gallstone disease is significantly and consistently associated with an increased risk of incident CHD independent of traditional risk factors in both women and men in the U.S. The combined, meta-analyzed observations from our cohorts and previous prospective cohorts support our results. Our findings highlight the potentially implication of gastrointestinal disorders on prevention of cardiovascular disease.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Gallstone disease and cardiovascular disease share a few risk factors; however, prospective data in the U.S. regarding the association of gallstone disease and cardiovascular risk are limited.

In our three prospective studies of 270,067 women and men, we found that a history of gallstone disease was associated with an 18% increased risk of CHD, independent of traditional risk factors.

Results from the meta-analysis incorporating previously published data from four additional prospective cohort studies further confirmed our findings.

Our findings highlight the potentially implication of gastrointestinal disorders on prevention of cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants for generously helping us in this research.

Sources of funding

The cohorts were supported by grants of UM1 CA186107, R01 HL034594, UM1 CA176726, UM1 CA167552, R01 HL35464 from the National Institutes of Health. The current study was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL071981, HL034594, HL126024), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK091718, DK100383, DK078616), the Boston Obesity Nutrition Research Center (DK46200), and United States – Israel Binational Science Foundation Grant 2011036. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute had no role in the design, conduct, analysis, or reporting of this study.

Abbreviations

- CHD

coronary heart disease

- NHS

the Nurses’ Health Study

- NHS II

Nurses’ Health Study II

- HPFS

the Health Professionals Follow-up Study

- AHEI

Alternate Healthy Eating Index

- BMI

body mass index

- HR

hazard ratio

- CI

confidence interval

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Xu is a receiver of National Natural Science Foundation of China (81471062) and the Gaofeng Clinical Medicine Grant Support from the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (20152508). Dr. Qi was a recipient of the American Heart Association Scientist Development Award (0730094N), and Shanghai Thousand Talents Program for Distinguished Scholars. The authors have nothing else to disclose.

References

- 1.Portincasa P, Moschetta A, Palasciano G. Cholesterol gallstone disease. Lancet. 2006;368:230–239. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kratzer W, Mason RA, Kachele V. Prevalence of gallstones in sonographic surveys worldwide. J Clin Ultrasound. 1999;27:1–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0096(199901)27:1<1::aid-jcu1>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stender S, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Elevated body mass index as a causal risk factor for symptomatic gallstone disease: A mendelian randomization study. Hepatology. 2013;58:2133–2141. doi: 10.1002/hep.26563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weikert C, Weikert S, Schulze MB, Pischon T, Fritsche A, Bergmann MM, Willich SN, Boeing H. Presence of gallstones or kidney stones and risk of type 2 diabetes. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:447–454. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu M, Li Y, Zheng Y, Qi L. Gallstones and risk of type 2 diabetes. In process. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen LY, Qiao QH, Zhang SC, Chen YH, Chao GQ, Fang LZ. Metabolic syndrome and gallstone disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4215–4220. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i31.4215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ata N, Kucukazman M, Yavuz B, Bulus H, Dal K, Ertugrul DT, Yalcin AA, Polat M, Varol N, Akin KO, Karabag A, Nazligul Y. The metabolic syndrome is associated with complicated gallstone disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25:274–276. doi: 10.1155/2011/356761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berr F, Pratschke E, Fischer S, Paumgartner G. Disorders of bile acid metabolism in cholesterol gallstone disease. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:859–868. doi: 10.1172/JCI115961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yokota A, Fukiya S, Islam KB, Ooka T, Ogura Y, Hayashi T, Hagio M, Ishizuka S. Is bile acid a determinant of the gut microbiota on a high-fat diet? Gut Microbes. 2012;3:455–459. doi: 10.4161/gmic.21216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu T, Zhang Z, Liu B, Hou D, Liang Y, Zhang J, Shi P. Gut microbiota dysbiosis and bacterial community assembly associated with cholesterol gallstones in large-scale study. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:669. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Z, Klipfell E, Bennett BJ, Koeth R, Levison BS, Dugar B, Feldstein AE, Britt EB, Fu X, Chung YM, Wu Y, Schauer P, Smith JD, Allayee H, Tang WH, DiDonato JA, Lusis AJ, Hazen SL. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2011;472:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nature09922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vinje S, Stroes E, Nieuwdorp M, Hazen SL. The gut microbiome as novel cardio-metabolic target: The time has come! Eur Heart J. 2014;35:883–887. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang WH, Wang Z, Levison BS, Koeth RA, Britt EB, Fu X, Wu Y, Hazen SL. Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1575–1584. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charach G, Grosskopf I, Rabinovich A, Shochat M, Weintraub M, Rabinovich P. The association of bile acid excretion and atherosclerotic coronary artery disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2011;4:95–101. doi: 10.1177/1756283X10388682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koeth RA, Wang Z, Levison BS, Buffa JA, Org E, Sheehy BT, Britt EB, Fu X, Wu Y, Li L, Smith JD, DiDonato JA, Chen J, Li H, Wu GD, Lewis JD, Warrier M, Brown JM, Krauss RM, Tang WH, Bushman FD, Lusis AJ, Hazen SL. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of l-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2013;19:576–585. doi: 10.1038/nm.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bortnichak EA, Freeman DH, Jr, Ostfeld AM, Castelli WP, Kannel WB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM. The association between cholesterol cholelithiasis and coronary heart disease in framingham, massachusetts. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121:19–30. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wirth J, Giuseppe RD, Wientzek A, Katzke VA, Kloss M, Kaaks R, Boeing H, Weikert C. Presence of gallstones and the risk of cardiovascular diseases: The epic-germany cohort study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22:326–334. doi: 10.1177/2047487313512218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olaiya MT, Chiou HY, Jeng JS, Lien LM, Hsieh FI. Significantly increased risk of cardiovascular disease among patients with gallstone disease: A population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mendez-Sanchez N, Bahena-Aponte J, Chavez-Tapia NC, Motola-Kuba D, Sanchez-Lara K, Ponciano-Radriguez G, Ramos MH, Uribe M. Strong association between gallstones and cardiovascular disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:827–830. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mendez-Sanchez N, Zamora-Valdes D, Flores-Rangel JA, Perez-Sosa JA, Vasquez-Fernandez F, Lezama-Mora JI, Vazquez-Elizondo G, Ponciano-Rodriguez G, Ramos MH, Uribe M. Gallstones are associated with carotid atherosclerosis. Liver Int. 2008;28:402–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olaiya MT, Chiou HY, Jeng JS, Lien LM, Hsieh FI. Significantly increased risk of cardiovascular disease among patients with gallstone disease: A population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2013:8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lv J, Qi L, Yu C, Guo Y, Bian Z, Chen Y, Yang L, Shen J, Wang S, Li M, Liu Y, Zhang L, Chen J, Chen Z, Li L. Gallstone disease and the risk of ischemic heart disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:2232–2237. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruhl CE, Everhart JE. Gallstone disease is associated with increased mortality in the united states. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:508–516. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wei CY, Chung TC, Chen CH, Lin CC, Sung FC, Chung WT, Kung WM, Hsu CY, Yeh YH. Gallstone disease and the risk of stroke: A nationwide population-based study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23:1813–1820. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chavez-Tapia NC, Kinney-Novelo IM, Sifuentes-Renteria SE, Torres-Zavala M, Castro-Gastelum G, Sanchez-Lara K, Paulin-Saucedo C, Uribe M, Mendez-Sanchez N. Association between cholecystectomy for gallstone disease and risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Annals of Hepatology. 2012;11:85–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sabate J, Ang Y. Nuts and health outcomes: New epidemiologic evidence. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2009;89:1643S–1648S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmed MH, Hamad MA, Routh C, Connolly V. Statins as potential treatment for cholesterol gallstones: An attempt to understand the underlying mechanism of actions. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 2011;12:2673–2681. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2011.629995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carey MC, Mazer NA. Biliary lipid secretion in health and in cholesterol gallstone disease. Hepatology. 1984;4:31S–37S. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840040806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Low-Beer TS, Nutter S. Colonic bacterial activity, biliary cholesterol saturation, and pathogenesis of gallstones. Lancet. 1978;2:1063–1065. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)91800-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Targher G, Byrne CD. Gallstone disease and increased risk of ischemic heart disease: Causal association or epiphenomenon? Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2015;35:2073–2075. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koeth RA, Wang Z, Levison BS, Buffa JA, Org E, Sheehy BT, Britt EB, Fu X, Wu Y, Li L, Smith JD, DiDonato JA, Chen J, Li H, Wu GD, Lewis JD, Warrier M, Brown JM, Krauss RM, Tang WH, Bushman FD, Lusis AJ, Hazen SL. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of l-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2013;19:576–585. doi: 10.1038/nm.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leitzmann MF, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Spiegelman D, Grodstein F, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Giovannucci E. Recreational physical activity and the risk of cholecystectomy in women. The New England journal of medicine. 1999;341:777–784. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909093411101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leitzmann MFWW, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Spiegelman D, Colditz GA, Giovannucci E. A prospective study of coffee consumption and the risk of symptomatic gallstone disease in men. JAMA. 1999;281:2106–2112. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.22.2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.