Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRs), a class of small noncoding RNAs that act as post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression, have attracted increasing attention as critical regulators of organogenesis, cancer, and disease. Interest has been spurred by development of a novel class of synthetic RNA oligonucleotides with excellent drug-like properties that hybridize to a specific miR, preventing its action. In kidney disease, a small number of miRs are dysregulated. These overlap with regulated miRs in nephrogenesis and kidney cancers. Several dysregulated miRs have been identified in fibrotic diseases of other organs, representing a “fibrotic signature,” and some of these fibrotic miRs contribute remarkably to the pathogenesis of kidney disease. Chronic kidney disease, affecting ∼10% of the population, leads to kidney failure, with few treatment options. Here, we will explore the pathological mechanism of miR-21, whose pre-eminent role in amplifying kidney disease and fibrosis by suppressing mitochondrial biogenesis and function is established. Evolving roles for miR-214, -199, -200, -155, -29, -223, and -126 in kidney disease will be discussed, and we will demonstrate how studying functions of distinct miRs has led to new mechanistic insights for kidney disease progression. Finally, the utility of anti-miR oligonucleotides as potential novel therapeutics to treat chronic disease will be highlighted.

Keywords: microRNAs, Dicer, chronic kidney disease, fatty acid oxidation, mitochondria, angiogenesis, macrophage activation

micrornas (mirs) are small, 21- or 22-nucleotide, highly conserved RNAs first identified in 2001 in worms (52, 56, 103). They were found to be temporally expressed but not code for proteins and are therefore “non-coding.” However, their temporal expression and phylogenetic conservation suggested they play regulatory roles in cellular fate and function. In 2002, they were shown to be complementary to the untranslated sequence motifs that mediate posttranscriptional suppression of gene expression and therefore are a collection of RNA molecules that mediate posttranscriptional regulation of gene expression, which in many settings has equivalent or greater impact on phenotype than transcription factors (5, 53, 105). Since the identification of miRs only 14 years ago, there have been nearly 36,000 peer-reviewed publications about miRs, emphasizing the biological importance of these small molecules.

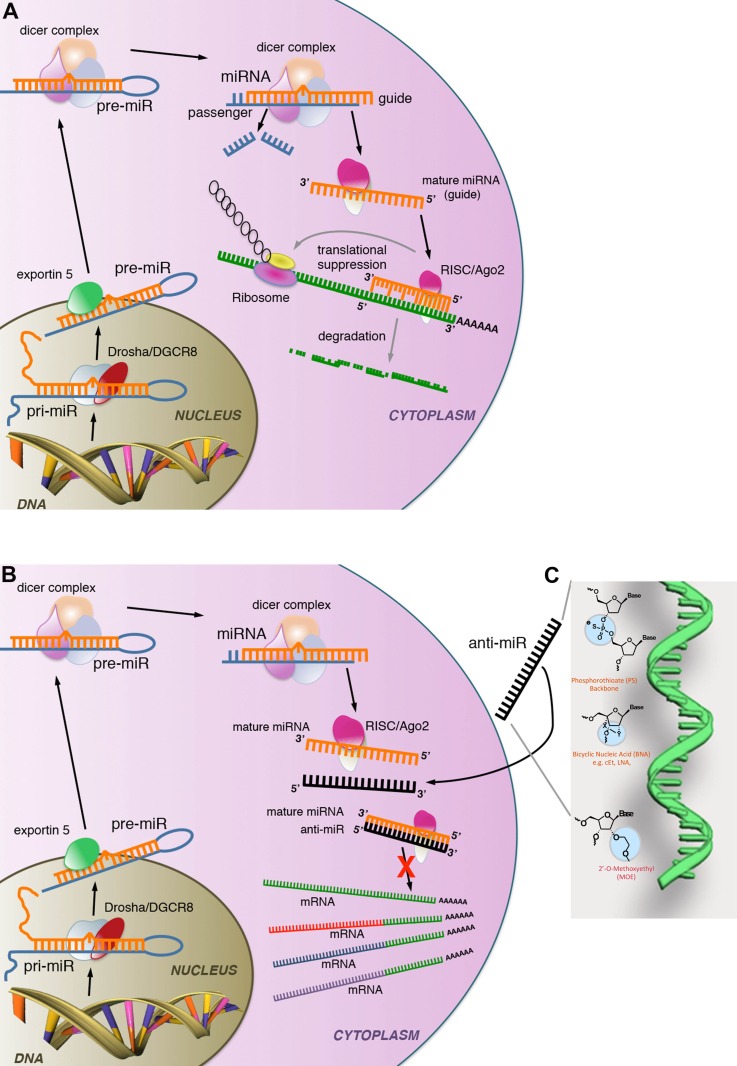

Over the following years, the complex function of miRs in controlling the expression of genes by preventing mRNA transcripts from being translated to proteins was unraveled (Fig. 1A). miRs are transcribed as precursor transcripts (pri-miR) or sometimes in long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) that are several hundred nucleotides in length, cleaved by the RNAse-III, Drosha, to form pre-miRs and exported as pre-miRs to the cytosol by a transporter known as exportin-5 (Fig. 1A). Pre-miRs form a complex hairpin structure with areas of complementarity interspersed by areas of non-complementarity. These pre-miRs are ∼70 nucleotides in length. They are subsequently loaded into a protein chaperone complex by the enzyme Dicer1, where they are cleaved into the mature 21- to 22-nt mature miR (Fig. 1A) (49, 57, 72, 107). The mature miR then complexes with protein chaperones, forming a ribonucleoprotein complex known as the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which includes the essential endonuclease activity of the enzyme argnoaute-2 (AGO2) (23, 66) (Fig. 1A). This protein complex directly interacts with mRNA transcripts and binds by sequence complementarity to the mRNA transcripts. This interaction triggers two separate processes. One is the blockade of ribosomal function and therefore prevention of translation. Separately, the argonaut complex triggers degradation of the mRNA (23, 88). By both of these mechanisms, miRs in the argonaute-containing RISC complex silence gene expression (Fig. 1A). Computational analysis of complementary sequences to specific miRs observed that most complementary sequences are in the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of mRNA and that a single miR may have as many as 500 predicted mRNA targets. Such predicted gene targets can be found at www.targetscan.org or http://www.ebi.ac.uk/enright-srv/sylarray/. Recent studies have identified real targets in cells and tissues using a number of techniques that include precipitation of RISCs that have incorporated a specific miR and confirmed that a single miR often has >100 gene targets. Frequently, many of these gene targets are modestly silenced by the miR, but many of the target genes are functionally related. In this way, a single miR may have a profound effect on a cellular process (10, 81). In addition, the gene targets vary from cell type to cell type and from tissue to tissue, imparting a degree of tissue specificity.

Fig. 1.

Schemas showing synthesis, enzymatic processing, and action of microRNA (miR) as well as the mechanism of miR suppression by anti-miR oligonucleotides. A: miRs are transcribed as 200-nt pri-miRs in the nucleus, cleaved, and processed by Drosha to 70-nt pre-miRs, which are exported to the cytosol where they are assembled into a protein complex with the enzyme Dicer1 which mediates pre-miR processing to the 22-nt mature miR. Mature miRs subsequently assemble with a protein complex (RNA-induced silencing complex; RISC) which includes AGO2, which further cleaves the mature miR to generate a guide from the 3′-arm which contains the seed-matched sequence at the 5′-end of the molecule. The miR associated with the RISC binds to specific sites (seed-matched target sites) at the 3′-end of mRNA, where it facilitates translational repression as well as RNA degradation, thereby inhibiting protein production. B: schema showing the mechanism of action of anti-miR oligonucleotides. Note anti-miRs bind to specific miRs by sequence complementarity in the RISC, thereby preventing anti-miR from interacting with 3′-untranslated regions (UTRs) of target mRNAs. C: image highlighting modifications to the ribose nucleic acid backbone that improve stability, enhance complimentary binding, and enable tissue localization of anti-miR oligonucleotides.

The field of RNA interference heralded these rapid advances in our understanding of miR biology. Several years before the identification of miRs, the process of RNA interference was reported by Fire and coworkers (30, 82) to describe the observation that double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) can block gene expression when it is introduced into worms, demonstrating that this process was mediated through mRNA degradation rather than mRNA synthesis. Shortly thereafter, scientists identified that small numbers of synthetic dsRNA molecules ∼21 nt in length could effect RNA interference and prevent mRNA translation (74, 102). Therefore, the endogenous mechanism of miR action was discovered and manipulated several years before the identification of the endogenous effector dsRNA molecules.

Since the original descriptions of 15–50 distinct miRs in worms, the presence of >1,000 different miRs in mammalian cells is now widely accepted. Many of these miRs have poorly resolved functions, but an increasing number have been shown to profoundly affect cellular fate and function and prove to be every bit as powerful as transcription factors in controlling cellular processes.

Critical roles for miRs in organ patterning during embryogenesis as well as cell fate during cancer and even homeostatic functions were rapidly determined. Initial studies in worms and flies showed that a single miR such as let-7 or miR-14 was capable of silencing critical genes that regulate organogenesis or lipid metabolism (13, 80, 98). A major insight into miR function in mammals was made possible by deletion of the enzyme Dicer, which cleaves pre-miRs to mature and therefore bioactive miRs. Dicer mutation results in severe vascular patterning defects in early development and lethality by embryonic day 12.5 in mice and severe defects in organogenesis in fish (27, 34, 43, 101). Conditional deletion of Dicer in mice has yielded considerable additional insight into miR function in different organs and has implicated miRs as major regulators of cellular function, not only in development but also in a number of diseases (27, 40, 60). In addition to development, miRs were first shown in 2002 to be dysregulated as a result of proximate mutations in many human cancers. In particular, lymphomas were shown to have mutations close to miR-155 and miR-15 that contributed to their survival, either by deletion of the miR (miR-15, -16) or by overexpression due to proviral insertions into the genomic DNA (miR-155) (8, 12, 28, 48, 55, 68). In 2005, miR-21 was reported to be an important survival factor in glioblastomas (16, 38) and subsequently in hepatocellular carcinoma, renal cell cancers (RCC), and certain lymphomas (15, 17, 24, 35, 66, 67, 104), where hypomethylation of the miR-21 chromatin locus has been repeatedly noted to explain why it is overexpressed.

Although miRs are RNA molecules, their secondary structure renders them very stable and highly resistant to enzymatic degradation. Hence, although ssRNA is rapidly degraded extracellularly, miRs are readily detected in exosomes as well as unprotected in body fluids, where they have been shown to play active roles in cell-to-cell transmission, cell-to-cell signaling, as well as a secondary role as biomarkers (5, 16, 100, 103). miR expression is also regulated by a number of factors, including activity of the activating enzyme Dicer, epigenetic regulation of the pre-miR gene locus by factors such as histone modifications, and promoter methylation (7).

A Role for miRs in Kidney Development and Cancer

In the kidney, miRs have been shown to play critical roles in nephrogenesis and also shown to be dysregulated in renal cell carcinomas. Conditional mutation of the pre-miR processing enzyme Dicer1 only in the kidney epithelium or kidney stroma results in profound defects in nephrogenesis. When Dicer was mutated in the developing epithelium, premature termination of nephrogenesis due to loss of epithelial progenitors was noted, as well as disruption of branching morphogenesis, along with dysregulation of the epithelial cell cycle, associated with enhanced apoptotic cell death. Cyst formation was a frequent feature in the developing kidney, particularly when Dicer1 was mutated in the ureteric bud epithelium (69, 72). These defects were associated with loss of miR-200, -30, and let-7a from the kidney epithelium. Recent reports of Dicer1 mutation in the kidney stroma show profound patterning and differentiation defects of not only the stroma and its derivatives but also in the nephron and microvasculature (71). Such broad effects of a stromal-restricted mutation on nephrogenesis emphasize critical roles for the stroma in epithelial patterning, as well as microvascular patterning (which receives significantly less attention) in nephrogenesis. The defects in epithelial development included impaired polarized cell division and therefore nephron lengthening and impaired segmental differentiation. The defects in the endothelium included delayed vasculogenesis, abnormal branching, and abnormal dilatation of capillaries. The kidney defects were sufficient to bring about perinatal mortality at least in part due to failure of the kidney to function. Therefore, miRs critically coordinate many aspects of organ patterning in the kidney. Strikingly, the stromal cells that lack Dicer1 are hypoactivated rather than overactivated, and many signaling pathways are suppressed rather than derepressed (73). This may suggest Dicer1 has broader roles in cellular function than only activation of miRs, but it also points to miRs having major roles in suppressing endogenous inhibitors of cell function. Analysis of miRs enriched in stroma alongside those suppressed by Dicer1 mutation in stroma identified a limited number of miRs that appear to regulate stromal function. These include miR-199, -214, -32, -127, -136, -143, -541, -466, and -467. By contrast, other miRs active in development but enriched in the epithelium or endothelium include miR-451, -144, -192, -200, -223, and -126 (73).

Increasing recognition for important roles for miRs in RCC has been reported. These cancers are widely believed to be of epithelial origin. An important role for miR-21 in regulating glycolysis has been implicated in RCC, although not mechanistically tested (17, 66). Glycolytic tumors have a marked survival advantage, and the miR-21 gene locus was identified as a hypomethylated site (activated) in those carcinomas with poor outcome, suggesting miR-21 is functioning as an RCC oncomir. In addition to miR-21, a characteristic pattern of dysregulated oncogenic miRs has been reported in RCC, which includes miR-21, -126, -451, -146, and -200 (4, 17, 81, 82, 88).

Chronic Kidney Diseases Characterized by Injury and Fibrosis

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) comprises a heterogeneous group of diseases characterized by progressive loss of kidney function. Although many differing triggers initiate the disease, including diabetes, hypertension, ischemic injury, xenobiotics, immune complex deposition, infections, as well as inherited/genetic causes, there are common histological and transcriptional features shared by these disparate diseases once they enter the chronic phase (13, 17, 74). It is increasingly believed that common processes drive progression, regardless of the initiating insults. The chronically diseased kidney is characterized by parenchymal injury, inflammation, fibrosis, and capillary loss and may be considered a chronic wound-healing response that has not resolved (17, 27). Flattening and thinning of epithelial cells, thickening of basement membranes, and associated loss of function characterize the parenchymal injury. Glomerular injury is characterized by endothelial swelling and subsequent loss of capillaries, which are replaced by a form of fibrosis known as sclerosis. Similarly, capillary injury adjacent to tubules is characterized by progressive loss of capillaries. Current thinking is that injury to capillaries or the epithelium directly drives the fibrogenic process, and recruited leukocytes may serve to perpetuate the inflammatory process and maintain fibroblasts in a pathological state (17, 27, 60). In certain diseases, such as autoimmune diseases, leukocytes may initiate injury, particularly to the glomerular and peritubular capillary endothelium when immune complexes form (8, 17, 37, 55).

Dysregulated miRs in Human CKD

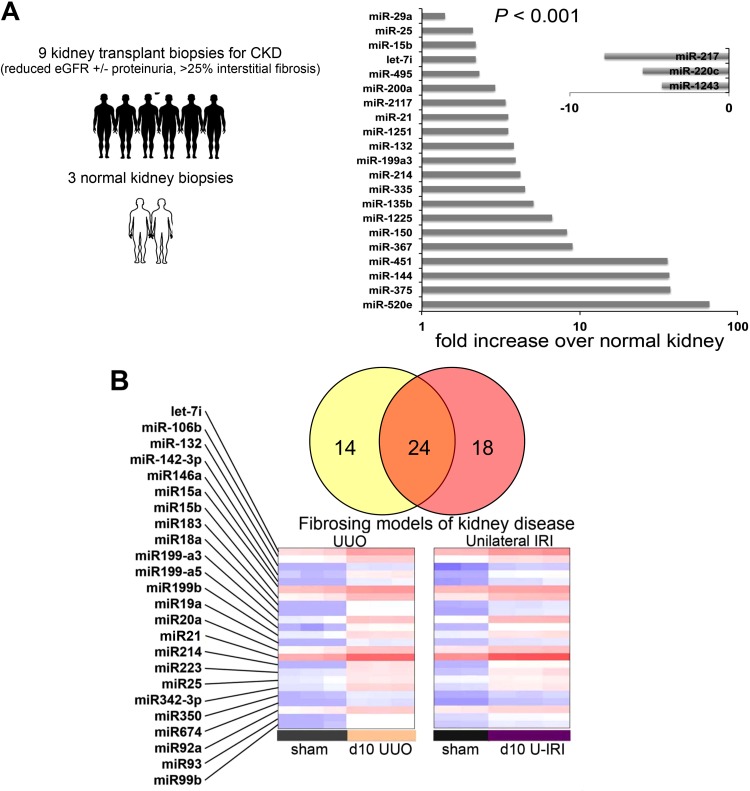

Because pathways regulated in development and in cancer are frequently activated in disease states, we reasoned that miRs may play a role in kidney disease, where reactivation of developmental pathways is widely reported. To identify abnormally expressed miRs and study the possible role of miRs in kidney disease, we collected kidney biopsies from patients with kidney transplants who had developed a fibrotic CKD of their transplant and collected biopsies from normal healthy kidneys that were being donated for transplantation. Isolated total RNA was subjected to hybridization to Agilent miR arrays, and relative miR levels were determined. By performing a simple analysis comparing fibrotic kidney miR levels with normal kidney miR levels, we identified 21 different miRs that were upregulated with a high degree of significance and 3 miRs that were downregulated (Fig. 2A). Although no kidney-specific miRs were identified, the signature of upregulated miRs included several miRs that had been associated with survival in cancers including miR-15, -21, -200, and -451 (1, 38, 48, 77). In a comparison of results from human CKD with kidney biopsies from short-term animal models of kidney injury with fibrosis triggered by obstruction (UUO) or ischemic injury (unilateral ischemia-reperfusion injury), 24 regulated miRs were identified that were shared by both fibrosing models (Fig. 2B). These miRs were all upregulated and included the following miRs that were also upregulated in human biopsies (Fig. 2A): let-7i, miR-15b, -21, -25, -132, -199, and -214. The finding that animal models shared many of the same miR changes with human biopsies characterized by fibrosis (Fig. 2A) suggested there may be a fibrotic miR signature in the kidney, that these dysregulated miRs may be playing roles in regulating the disease process either positively or negatively, and that the animal models could be used to interrogate their function.

Fig. 2.

Identification of regulated miRs in chronic kidney disease. A: graph showing the relative expression of miRs in the human kidney significantly (P < 0.0001) regulated by the presence of chronic kidney disease, defined by albuminuria loss of kidney function and histological fibrosis affecting >25% of the area of the tissue, compared with healthy control kidney biopsies. Clinically indicated biopsies from patients with a kidney transplant and a new kidney disease were collected. Pretransplant biopsies from healthy donors were used as controls. RNA extracted and miR levels were quantified using Agilent arrays and analyzed using Array Studio and DAVID bioinformatics. B: heatmap and Venn diagram showing significantly upregulated miRs comparing a model of obstructive kidney injury [unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO)] with fibrosis with a model of ischemic injury [ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI)] with fibrosis. A common signature of 14 overlapping miRs that are upregulated is shown. The heatmap shows relative expression of those upregulated miRs common to both disease models (red is high and blue is low). (Adapted from Ref. 17).

miR-21—A Central Regulator of Metabolic Activity in the Kidney

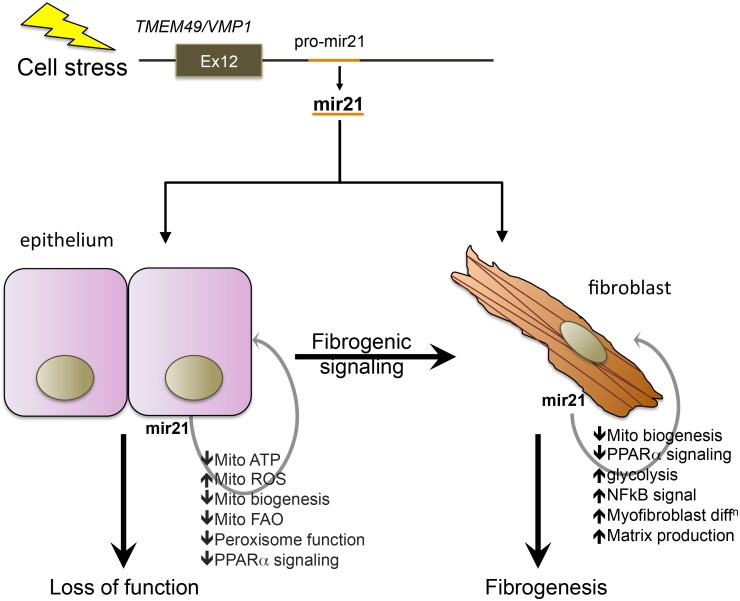

miR-21 was identified as an upregulated miR in several distinct animal models of kidney disease and in both human acute kidney injury (AKI) and CKD tissue samples (17, 35, 37, 50, 104) (Fig. 2). In addition, it was also shown to be one of the more highly expressed miRs in the healthy kidney (17, 37) (Fig. 2). In hypertrophic cardiac tissue, miR-21 was reported to contribute to disease pathogenesis by stimulating MAPK signaling, whereas in the setting of malignancy miR-21 had been reported to enhance survival and prevent apoptotic cell death when overexpressed in malignant cells, suggesting it could serve as an oncomir (16, 21, 36, 100). The miR-21 gene locus is embedded in the VMP1 gene coding for a vesicle-associated protein, which is upregulated in settings of cell stress and has recently been described to regulate the formation of autophagosomes during cell stress (Fig. 3) (22, 69). miR-21 expression is induced by factors including hypoxia and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β stimulation of cells in vitro, in keeping with its role as a stress response miR (17, 37). In addition to upregulation in epithelial cells in the kidney and liver (hepatocytes), however, it is expressed at moderately high levels in quiescent conditions or in healthy tissue but appears to be inactive (4, 21). One study separated different cytosolic compartments from hepatocytes and found that miR-21 was within a vesicular fraction in quiescent conditions but translocated to a more soluble fraction in response to cell stress (4, 36). The implication from these observations is that miR-21 can respond very rapidly to cell stress because it is already present within epithelial cells. Although miR-21 has all the hallmarks of playing important roles in disease, global deletion of the miR-21 gene has no effect on development or health of adult mice housed in sterile facilities over the course of more than a year, suggesting miR-21 may be functionally important only in stress settings.

Fig. 3.

Schema showing major mechanism of action of miR-21 in accelerating injury responses to promote organ failure and fibrosis. The pre-miR-21 gene is embedded 3′ to the terminal exon of the VMP1 gene, a cell stress response gene involved in autophagy. Upon upregulation, miR-21 directly suppresses genes involved in mitochondrial and peroxisomal functions including biogenesis, fatty acid oxidation, and suppressing reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. The transcription factor PPARα is an important target for miR-21. In fibroblasts, miR-21, acting partly through PPARα suppression and mitochondrial function suppression, also enhances matrix deposition and NF-κB signaling.

By contrast, in the setting of kidney injury lasting 1–2 wk, the kidneys from miR21−/− mice showed marked protection against the development of fibrosis (2, 17). This was associated with marked preservation of epithelial integrity and protection from epithelial cell death, suggesting miR-21 was contributing to both epithelial disease in response to injury, as well as promoting fibrosis (Fig. 3).

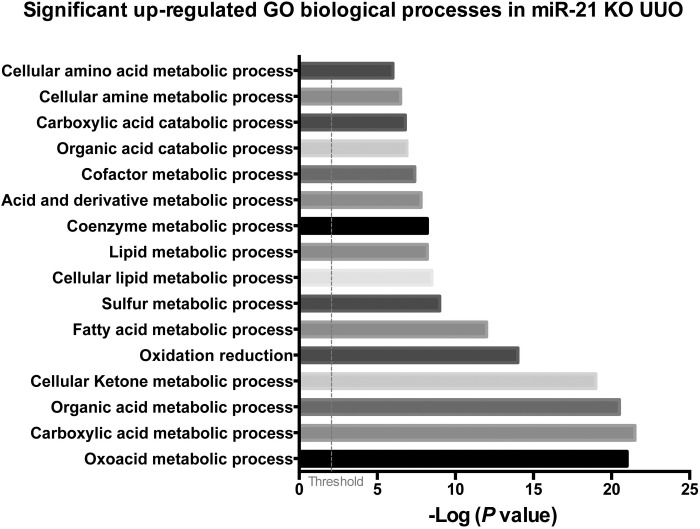

miR-21 has several hundred predicted gene targets based on the identification of complementary sequences in the UTR of mRNAs (see Fig. 1). When healthy kidneys were analyzed for the engagement and degradation of those potential target mRNAs by comparing miR21−/− kidney mRNA levels with those from miR21+/+ kidneys, investigators found very few of the potential target mRNAs were being silenced. However, when the same study was performed in kidneys that had become diseased, >100 predicted target genes were now shown to be actively silenced in the kidney (17, 92) (Table 1). The degree of silencing of a single type of mRNA by miR-21 was in the range of two- to fourfold only. Strikingly, however, the genes targeted for silencing by miR-21 were not involved in inflammation and fibrosis; rather they were predominantly involved in metabolic and mitochondrial functions of cells (Fig. 4). Many of the gene targets were functionally interrelated. One striking pathway regulated by miR-21 is oxidoreduction activity, which occurs principally in mitochondria, whereas another involved the fatty acid oxidation (FAO) pathway in peroxisomes and mitochondria (17, 110) (Fig. 4). FAO is highly regulated by the transcription factor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) α and its coregulated factor PPARγ coactivator-1α (PGC1α). PPARα was one of the matched gene targets for miR-21 in kidney disease as well as multiple factors and enzymes that are also regulated by PPARα activity in the nucleus (Fig. 3). Therefore, miR-21 plays a major regulatory role in FAO by regulating multiple FAO effector genes, including, as well as in concert with, PPARα. In addition to inhibiting FAO, the target genes for miR-21 indicated that miR-21 silences a range of mitochondrial functions and favors cells toward glycolytic metabolism (17, 87). The functional consequence of miR-21 activity is to decrease the capacity of mitochondria to generate ATP and increase their capacity to produce high levels of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Fig. 3). Although there are a number of other well-recognized potential target genes, including TIMP3, SMAD7, SPROUTY1, and PTEN, there was no convincing evidence that, in these kidney disease models, these genes were suppressed by miR-21 activity (6, 17, 37). Nevertheless, miR-21 was identified because of its ability to promote injury and fibrosis in the kidney. Therefore, the studies suggest that by suppressing FAO, suppressing mitochondrial function, and enhancing mitochondrial ROS generation (Fig. 3) miR-21 drives fibrosis indirectly, through augmenting deleterious epithelial responses to stress or injury. Although the kidney epithelium, which is rich in mitochondrial content, is the obvious cell target for miR-21 activity, studies indicate miR-21 is widely expressed in disease settings and that miR-21 controls FAO and mitochondrial function not only in epithelial cells but also in fibroblasts and podocytes (37, 64) (Fig. 3). There is evolving literature pointing to a metabolic switch to glycolysis as a critical step in activation of fibroblasts in a number of settings (65, 77). Therefore, it is likely that miR-21 regulates a metabolic switch that is also directly important in fibrogenesis.

Table 1.

List of 24 seed-matched target genes that are highly overrepresented in the diseased mouse kidney when miR-21 is absent

| Metabolism/Mitochondrial Biogenesis | |

|---|---|

| Acetyl-CoA C-acetyltransferase | Acat1 |

| Mpv17 like | Mpv17l |

| Pyruvate glycerol kinase 5 | Gk5 |

| Acyl-CoA synthetase medium chain | Acsm5 |

| PPARα | Ppara |

| Sperm mitochondrial protein | Smcp |

| Flavin containing mono-oxygenase 2 | Fmo2 |

| Choline phosphotransferase | Chpt1 |

| Coenzyme A synthase | Coasy |

| Peroxisome biogenesis gene | Pex10 |

| Alkylglycerone phosphate | Agps |

| Aldehyde dehydrogenase | Aldh2 |

| Glucosamine 6 phosphate dehydrogenase | Gnpda1 |

| Mitochondrial acyl transferase | Glyat |

| Fat storage-inducing membrane 2 | Fitm2 |

| Acyl cobinding domain protein | Acbd5 |

| Phosphoglucomutase 3 | Pgm3 |

| Cytochrome B5 | Cyb5 |

| Fatty acid desaturase | Fads6 |

| Acyl-glycerol phosphate acyltransferase 3 | Agpat3 |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase 1 | Pdha1 |

| Acyl-glycerol phosphate acyltransferase 5 | Agpat5 |

| Shuttling protein | Grpe1 |

| Alcohol dehydrogenase | Zadh2 |

miR, microRNA; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor.

Fig. 4.

Graph showing the most significantly enriched gene ontology (GO) pathways in the diseased mouse kidney when miR-21 is absent. KO, knockout.

It should be noted that although many studies show a pathological role for miR-21 in kidney disease progression, there are two examples where miR-21 has been reported to be protective (54, 99). In one of these, miR-21 was reported to play a role in ischemic preconditioning, where miR-21 expression protects against subsequent injury. It makes sense that activated miR-21 plays a physiological role in protecting cells from acute injury by shutting down metabolic functions, which could therefore contribute to ischemic preconditioning. In chronic disease settings, however, persistent activation of miR-21 is detrimental, due to chronic loss of cell function and persistent activation of fibrogenesis.

Anti-miR Oligonucleotides—A Novel Class of Therapeutics with High Penetrance of the Kidney

In parallel with the discovery of gene silencing by RNA has been the development of anti-RNA oligonucleotides that are able to enter cells in whole animal and suppress translation of mRNA (Fig. 1B). Several advances been made in RNA stability in vivo by molecular modification of the RNA backbone to convert highly unstable RNA molecules into highly stable RNA molecules that are resistant to the activity of RNase H (Fig. 1C). These modifications include the use of 2′-O-methyl RNA molecules, the replacement of the phosphodiester backbone with a phosphorothioate backbone, and the use of locked bicyclic nucleic acids in certain places in the oligonucleotide (1, 6) (Fig. 1C). Additionally, the 2′-O-methoxyethyl (MOE) and 2-oxy-methyl (OMe) modifications to the backbone enhance affinity for complementary nucleotides, thereby enhancing drug-like properties (50). Attaching these modified RNA molecules to lipids or other moieties has helped direct them to a variety of different tissues or specific cell types (37). Moreover, modification of the native RNA backbone has markedly reduced the type I interferon response that cells have in response to exposure to extracellular RNA or DNA. The oligonucleotides are designed to bind by Watson-Crick sequence complementarity to the active site of the specific RNA that is being targeted (Fig. 1B), usually in the 3′-UTR.

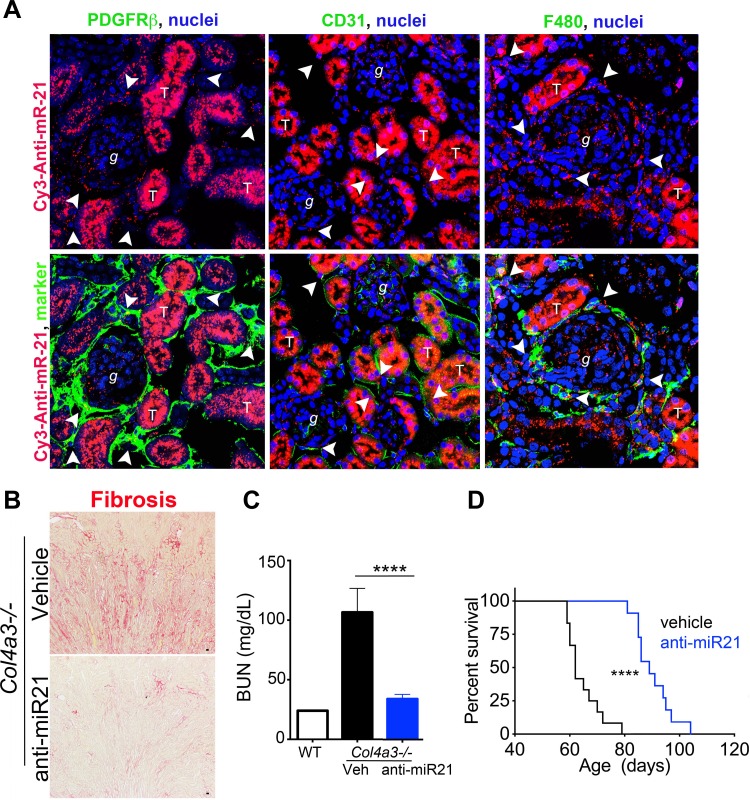

In tracking studies of radiolabeled or fluorescently tagged oligonucleotides, the RNA oligonucleotides have a predilection to distribute widely throughout the body to intracellular compartments. However, the greatest concentration of anti-miR oligonucleotides is found in the kidney and liver following systemic delivery (Fig. 5A). One possible reason for this is that these organs are both critical in removal of waste products from the body. In the kidney, the proximal tubule concentrates the oligonucleotides most strongly, but endothelial cells, macrophages, podocytes, and fibroblasts all concentrate readily detectable levels of the oligonucleotide drug (Fig. 5A). One interesting aspect of the behavior of the drug is that the healthy glomerulus appears devoid of intracellular uptake, but the diseased glomerulus readily concentrates the drug in all cell types, including the podocyte, indicating that anti-oligonucleotide therapy may benefit glomerular as well as tubulointerstitial diseases of the kidney. The latest generation of anti-miR oligonucleotides can be delivered by weekly subcutaneous injection without loss of activity. Recent studies using anti-miR-21 oligonucleotides have demonstrated their utility and specificity in animal models of AKI as well as a chronic disease known as Alport syndrome (17, 37) (Fig. 5). Alport syndrome is an inherited single-gene disorder of the collagen-IV gene, affecting the kidney and ear, leading to deafness and kidney failure. The disease shows strong similarity to other chronic progressive diseases, including focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, hypertensive nephropathy, and IgA nephropathy. Although Alport nephropathy is caused by mutations in the capillary basement membrane, the abnormal basement membrane is thought to trigger cell stress in the endothelium, podocytes, and tubular cells, which secondarily triggers fibrosis and recruitment of leukocytes. Mice with an engineered mutation in one of the collagen-IV genes develop a progressive kidney disease, which is highly similar to the human disease, and succumb to kidney failure by 11 wk of age. As in other kidney diseases in mice, miR-21 was elevated in the kidneys of these mutant mice, but the elevated levels preceded any histological abnormalities in the kidneys, consistent with miR-21 being regulated by cell stress. Weekly delivery of anti-miR21 oligonucleotides to diseased mice after disease onset, profoundly retarded the progression of disease, normalized tubular functions, and led to an increase in life expectancy of nearly 50% (37) (Fig. 5, B–D). The transcriptional changes in kidneys as a result of anti-miR-21 were significant protection of mitochondrial function and marked activation of PPARα and PGC1α signaling pathways, which include FAO. In primary cell cultures from Alport kidneys, the anti-miR-21 oligos directly protected cells from mitochondrial dysfunction in the setting of induced cell stress, directly inhibited fibroblasts from activation under typical activating stimuli (Fig. 3), and showed highly similar effects on the kidney as genetic deletion of miR-21 (16, 36).

Fig. 5.

Anti-miRNA modified oligonucleotides block specific miRNA function and have excellent drug like properties with high penetrance to kidney cells in vivo. (A) Fluorescence images (X400) of the kidney showing the distribution of a single injection of anti-miR21-Cy3 (red) subcutaneously (25 mg/kg in 50 μl, 48 h previously). Note that the compound is concentrated in tubule epithelium but is also detected in glomerular cells, macrophages (F4/80), endothelium (CD31) and fibroblasts (PDGFRβ). Arrowheads show areas of co-localization. Effect of Anti-miR21 on (B) Fibrosis, (C) Blood urea nitrogen concentration (D) and survival (I) in Col4a3−/− mice with Alport nephropathy. (Adapted from Ref. 37). ****P < 0.0001.

In other studies, delivery of anti-miR-21 oligonucleotides to mice with a model of diabetic kidney disease also had beneficial effects on glomerular function and retarded the progression of diabetic kidney disease (109). Moreover, these compounds have been given to small and large animals for many weeks without obvious deleterious effects. Therefore, anti-miR-21 oligonucleotides represent a novel class of therapeutics to treat fibrosing kidney diseases, now entering phase II clinical trials. Although the safety of delivering a modified oligonucleotide to the body has been raised, phase III clinical trials are underway using antisense oligonucleotides to treat a number of diseases, and have so far proven safe. These oligonucleotides have a similar backbone structure to anti-miR oligonucleotides. In addition, anti-miR-21 oligonucleotides have proven to be safe in long-term studies in primates and more recently in humans.

Other Dysregulated miRs That Play Pathological Roles in the Kidney

An increasing number of publications have identified pathological or beneficial roles for miRs in regulating kidney diseases (Table 2), and many of these overlap with the miRs identified in fibrogenesis. In the following, we will highlight those miRs that have been shown to play additional roles in fibrogenic disease.

Table 2.

Summary of publications highlighting miRs that play a role in kidney disease

| miRs | Level During Disease | Target | Outcome/Function | Models | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Let-7b | Down | TGFBR1 | SMAD3, ECM decrease | Diabetic mice (STZ), NRK52E cells | 89 |

| miR-21 | Up | PPARa, MPV17L, and FAO | Increased fibrosis | Alport mouse, human biopsy | 37 |

| PTEN, PRAS40 | p-Akt, mTORC1, hypertrophy, COL1α2, FN increase | HMCs | 25 | ||

| SMAD7 | Microalbuminuria, TGF-β, NF-κB increase | db/db mice | 111 | ||

| TIMP1, MMP9 | COL4, FN, ACR increase | kk-ay mice | 93 | ||

| miR-25 | Down/Up | NOX4 | NOX4 decrease | RMCs/human biopsy | 32 |

| miR-29a/b/c | Down | COL1 and COL4 | COL1, COL4, decrease | NRK52E cells, MMCs, and human podocytes | 91 |

| miR-29a | Down | COL4α1/2 | COL1, COL4, decrease | HK-2 cells | 26 |

| HDAC4 | Podocyte dysfunction | Podocytes | 59 | ||

| miR-29b | Down | TGFBR | TGF-β/SMAD3, Sp1/NF-κB decrease | db/db mice | 19 |

| miR-29c | Up | SPRY1/HIF1a | Albuminuria, ECM increase | db/db mice | 63 |

| miR-93 | Down | VEGF-A | COL4α3, VEGF, and FN decrease | db/db mice, podocytes and endothelial cells | 62 |

| miR-124 | Up | Integrin-α3β1 | Urinary podocyte nephrin, podocin, albumin increase | Diabetic rats (STZ) | 58, 87 |

| miR-126 | Up | Endothelium | Vascular integrity | Renal cell carcinoma | 79, 88 |

| miR-135a | Up | TRPC1 | Microalbuminuria and renal fibrosis increase | db/db mice | 41 |

| miR-136 | Unknown | Unknown | Stromal function | Dicer KO | 73 |

| miR-143 | Unknown | Unknown | Stromal function | Dicer KO | 73 |

| miR-144 | Unknown | Unknown | Epithelium/endothelium enrichment | Dicer KO | 73 |

| miR-146 | Up | AD-2 | Inflammation | Renal cell carcinoma | 83, 33 |

| miR-155 | Up | B cells | Increased inflammation | Lupus | 85, 96 |

| miR-192 | Up | SIP1 | COL1a1 and COL1a2 increase | STZ mice, db/db mice | 47, 78 |

| miR-195 | Up | BCL2 | Caspase-3, caspase-8 increase | Diabetic mice (STZ), podocytes, MMCs | 20, 31 |

| miR-199 | Up | TGFb | Increased fibrosis | Fibroblast activation and human biopsy | 18, 61 |

| miR-200a | Down | TGF-β2 | COL1, COL4, FN decrease | NRK52E cells | 38, 90 |

| miR-200b/c | Up | ZEB1 | TGFb, COL1a2, and COL4a1 increase | STZ mice, db/db mice | 44 |

| FOG | p-AKT and ERK increase and hypertrophy | MMC | 73, 75 | ||

| miR-214 | Up | Unknown | Increased fibrosis | Human biopsy | 21, 110 |

| miR-215 | Up | CTNNBIP1 | β-Catenin, FN, α-SMA increase | 71 | |

| miR-216a | Up | PTEN, YBX1 | COL1a2 increase, MMC survival and hypertrophy | MMC | 46 |

| miR-217 | Up | PTEN | MMC survival and hypertrophy | MMC | 45 |

| miR-221 | Up | Unknown | RCC | 88 | |

| miR-223 | Up | NLRP3/IL1b | Inflammasome | 9, 39 | |

| miR-377 | Up | PAK1, SOD | FN increase | Diabetic mice (STZ), MMCs, HMCs | 94 |

| miR-451 | Down | YWHAZ | p38MAPK, ECM decrease | MMCs and RCC | 82, 108 |

| miR-466 | Unknown | Unknown | Stromal function | Dicer KO | 73 |

| miR-467 | Unknown | Unknown | Stromal function | Dicer KO | 73 |

| miR-541 | Unknown | Unknown | Stromal function | Dicer KO | 73 |

| miR-1207-5p | Up | TGFBR | TGF-β1, PAI-1, FN increase | HK-2 cells, podocytes, and mesangial cells | 3 |

See the text for additional abbreviations.

miR-214 has also been shown to be expressed at high levels in human kidney disease and animal models of kidney disease (21, 36) (Fig. 2). miR-214 is cotranscribed with the miR-199a family on a single lncRNA strand which is on the complementary strand of an intron of the dynamin-3 gene. Dynamin-3 plays roles in cell trafficking of vesicles along microtubules and in cell motility. Genetic mutation of the coregulated 199a/214 pre-miR strand (known as Dnm3os) indicated that the RNA is expressed predominantly in mesenchymal, skeletal, and vascular smooth muscle cells, and osteoblasts during embryogenesis rather than in the epithelium. Although Dnm3os mutant mice were born in Mendelian ratios, they were small, gained weight poorly, and had a median survival of 2–3 wk with substantial musculoskeletal defects, including impaired ossification, muscle weakness, and reduced adipogenesis. Defects in other organs were not reported. On the other hand, selective global deletion of the miR-214 gene only, or miR-199a only in mice, leads to a Mendelian ratio at birth and normal fertility without overt organ disease or musculoskeletal disease (22, 37). Nevertheless, when kidney disease was induced in the form of obstruction of the ureter, miR-214-deficient mice were highly protected from the development of fibrosis (21). miR-214 and miR-199a genes appear to be regulated by activation of the mesenchymal transcription factor TWIST and also hypoxia through the actions of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (36). The effect of miR-214 on cell function in the kidney has been less well studied, but in other tissues has been reported to be expressed widely in disease settings including in injured or activated epithelial cells, stromal cells, and the endothelium (2, 87). Inhibition of miR-214 function in primary human kidney stromal cell cultures resulted in cells that were hypoactivated, hypomigratory, and hypoproliferative in response to activating stimuli (73). Similarly, blockade of miR-214 in cancer cells has rendered them hypomigratory and more resistant to cytotoxic stress (92), potentially by enhancing BCL family proteins or the AP2 family of transcription factors (110), and inhibition of miR-214 stimulates beneficial angiogenesis (87) potential by enhancing expression of Quaking (QKI), an RNA binding protein that enhances RNA translation. Recent studies in biomechanical stress-induced cardiac fibrosis showed that miR-214 along with miR-199a potently regulated pathological myocardial responses to disease and that antagomiRs against miR-214, and to a lesser extent miR-199a3p, blocked cardiac fibrosis (6, 64). Studies of human hepatic stellate cells indicate that miR-214 directly stimulates TGF-β-mediated pathological responses and inhibits matrix gene expression (65). Although the mechanism of action of miR-214 in fibrosis is less well elucidated than that for miR-21, several recent studies have identified critical target genes in injury and fibrosis. In cardiac disease, PPARδ has been recognized as an important cellular target (6). This transcriptional regulator, like PPARα, plays important roles in regulating FAO and mitochondrial function, and, like PPARα, has been reported to play a protective role in the kidney following acute injury (37). Moreover, polymorphisms at the PPARD locus have been associated with CKD in several independent studies (42). Thus one of the ways in which miR-214 may act in kidney fibrosis is by regulating metabolic responses, similarly to miR-21. The phosphatase and AKT signaling pathway inhibitor, known as PTEN, is also a recognized target for miR-214 in the setting of cancer cell function. The AKT signaling pathway has been shown to be an important mechanism in chronic disease of the kidney. Further studies are required to understand the mechanism of action of miR-214.

An important but unresolved question is the pathological importance of miR-199a. This gene forms a pre-miR, which after RNA processing gives rise to two distinct miRs, miR-199a5p and miR-199a3p. miR-199b5p and miR-199b3p are identical but transcribed from a distinct chromosome. Several studies in non-renal tissue have pointed to discrete roles for these mature miRs in migration and matrix deposition, but they share significant overlapping gene targets with miR-214, and their importance has not been validated well in kidney. One study on human kidney fibroblast cells indicated that both miR-199a3p and miR-199a5p nhanced proliferation and cell activation but that, miR-199a-3p was more potent than miR-199a-5p in overall activity. (73). Other studies have indicated miR-199a5p plays a role in fibrogenesis in the lung, particularly by inhibiting expression of caveolin-1 (61). The significance of the miR-199a genes in kidney disease merits further investigation.

miR-155 has been reported to be elevated in a number of human chronic kidney diseases, including diabetic nephropathy, lupus nephritis, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis, and hypertensive kidney disease (85). It is expressed in the endothelium, stromal cells, as well as tubular epithelium. Although its role in kidney disease remains to be fully elucidated, several studies have shown miR-155 contributes to B cell activation and antibody production, in part by inhibiting the phosphatase SHIP. SHIP plays important roles in myeloid cell activation in addition to B cells, and therefore miR-155 is likely to play a role in monocyte and neutrophil activation in the kidney. In fact, miR-155 amplifies LPS responses in macrophages as well as activation by oxidized lipids, suggesting broader roles in regulating inflammatory signaling. Given the broad activating effects of miR-155 in models of lupus nephritis and the efficacy of anti-miRs in these models, miR-155 may evolve as a potential target for autoimmunity or immune complex-activated kidney diseases.

miR-223 is upregulated in a range of human kidney diseases, as well as animal models (see above and Fig. 2). The function of miR-223 is less well understood than other miRNAs. It has been shown to directly target the inflammasome effector molecule NLRP3 and suppress expression of NLRP3 in myeloid cells (9, 39) in settings of infection or pathogen pattern recognition receptor activation. In preliminary studies from our laboratory, anti-miRs against miR-223 had no overt effect on the fibrogenic process during the ureteral obstruction model of kidney disease. However, this particular model of fibrogenic disease progresses without a substantial role in innate immune signaling whereas the role of innate immunity in kidney diseases, particularly ischemic kidney disease, is well accepted (14). Therefore miR-223 may serve in beneficial ways in kidney disease to limit activation of the inflammasome.

The miR-200 family includes miR-200a, -200b, -200c, -141 and -429, all of which have the same seed sequence; that is, the critical sequences that recognizes the 3′-UTR sequence is identical. In short-term models of kidney injury and fibrosis, the family is broadly downregulated (97). In kidney cancers, miR-200 family members are also downregulated, but our studies of CKD biopsies indicate miR-200c is downregulated whereas miR-200a is upregulated. Therefore, the significance of this target in chronic fibrosing human disease requires further studies. The miR-200 family has been implicated in maintaining epithelial health by inhibiting the process of the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and may play inhibitory roles in metastasis. They have been shown to silence the ZEB family of transcription factors that regulate EMT and epithelial migration. Furthermore, in vitro studies using kidney epithelial cell lines indicate RNA mimics of these miRs delivered intracellularly inhibit both the EMT process and ZEB1/ZEB2 transcription factor activity (97). The absolute importance of the EMT process in human epithelial disease has recently been questioned, and therefore further studies into the importance of the miR-200 family in human injury repair remain to be determined.

The miR-29 genes include miR-29a, -29b, and -29c, which are coded by distinct genomic loci but have identical seed sequences. They have been reported to be downregulated or abnormally regulated in many diseases of the kidney (29). In fibrotic kidney transplant biopsies, miR-29a was modestly upregulated, however (Fig. 2), and in other series miR-29 was not reported to be downregulated. miR-29 is one of the signature miRs of fibrotic diseases. In the setting of skin fibrosis, myocardial disease, and lung disease, miR-29 has been shown to be downregulated. Downregulation of the miR-29 loci is under the regulation of c-MYC, GLI, NF-κB, TCF/LEF, and SMAD3 (70). Analyses of target genes for miR-29 reveal that many target genes are matrix genes, including collagens, laminins, fibrillin, elastin, and integrin-β1 (51). In fact, miR-29 has the potential to reduce expression of as many as 20 collagen genes. Therefore, a miR-29 function in healthy tissues is to provide tonic suppression of production of matrix and matrix turnover. However, miR-29 also slows cell growth and may trigger apoptosis in certain cancer cells, such as acute myeloid leukemia, potentially by suppressing genes that normally silence the transcription factor P53 (76, 86). This proapoptotic effect of miR-29 may be triggered by DNA damage. Therefore, miR-29 has the potential to both suppress matrix deposition and drive cell death. Potentially, this could be beneficial if the cells that undergo apoptosis are fibrogenic cells, but a potential downside is deletion of cells that are critical to organ function. Although miR-29 has not been studied in great detail in the kidney, it is likely that miR-29 will be an important target to tackle fibrogenesis. Studies that separate antifibrotic effects from proapoptotic effects in will help elucidate whether miR-29 is a useful target in kidney diseases.

miR-126 is believed to be restricted in expression to endothelial cells and found to be highly expressed in capillaries and large blood vessels. miR-126 functions by regulating factors that control angiogenesis (95). It promotes endothelial proliferation and endothelialization of large vessels. The miR-126 gene is regulated by and encoded by an intronic region of the epidermal growth factor like-7 (EGFL7) gene. EGFL7 is restricted to endothelial cells. One of the main targets of miR-126 is EGFL7 itself. EGF7L is known to be involved in cell migration and blood vessel formation and believed to function by interacting with Notch receptors and the Notch receptor ligand Delta-like 4 (84). miR-126 is also reported to silence VEGFA, DLK1, transcription factors including IRS1, HOXA11, as well as the chemokine CXCL12. During tissue repair, endothelial cells release miR-126 within apoptotic bodies, inducing CXCL12-dependent vascular protection (106) by recruiting bone marrow progenitor cells to the site of tissue injury, where they promote vascular repair. Furthermore, miR-126 overexpression in bone marrow cells has recently been shown to promote vascular integrity following kidney injury by promoting bone marrow progenitor cell trafficking to the injured kidney, allowing for vascular mobility and supporting recovery of the kidney microvasculature (11).

miR Mimetics: Future Therapeutics with Far-Reaching Possibilities

The miR-29 and miR-200 families are broadly downregulated in human fibrotic disease of the kidney and other epithelial organs including the skin, lung, and liver. In addition, although miR-126 and miR-223 are upregulated in disease, their roles are mainly beneficial to the injured tissue. By contrast, miR-21, -214, -199, and -155 have all been demonstrated to drive pathological states, and organs have shown benefit from inhibiting their action by use of anti-miRs. The technological advances in anti-miR technology have resulted in anti-miRs that can function as candidate therapeutics. Similar efforts have been made to generate miR mimics. These are dsRNA molecules which separate intracellularly to ssRNA, and one strand loads into the RISC and functions as a miR. Several modifications can be made to the RNA to favor the loading of the mature miR strand over the other, with the RISC. Several innovative methods have been used to improve delivery and stability, including the use of three strands of RNA in which two have the LNA technology to enhance stability. Although such mimics have been widely used in cultured cells, their development as drug candidates has been hampered by delivery, triggering of TLR responses in vivo, and efficacy at the target organ. Although mimic technology lags behind anti-miR approaches, there is an increasing desire to target certain dysregulated miRs by augmenting their endogenous functions.

Discussion

A growing body of evidence indicates that miRs play critical roles in the function of epithelial, stromal, endothelial cells, and leukocytes in diseases of the kidney. Many of the dysfunctional miRs identified in fibrosing diseases of the kidney have also been shown to play roles in nephrogenesis and in kidney cancers. In addition, several miRs appear to play similar roles in fibrosing diseases of the skin, liver, kidney, and lung. miR-21 has probably been the most studied of the pathogenic miRs in kidney disease and detrimentally impacts the kidney by disrupting mitochondrial functions. Because miRs regulate multiple functionally related gene targets simultaneously, modifying a single miR with a drug has the possibility of affecting numerous cellular processes rather than simply regulating a single signaling pathway. In addition, many miRs are stress activated and appear to be inactive in situations of cell health. The genes coding such miRs are frequently embedded in, or are on the opposite strand of, important regulatory or stress-induced protein-coding genes such as those in involved in migration or trafficking. This lack of activity in healthy tissues provides an important advantage in the development of safe therapies which target miRs. Since many of the candidate therapeutic targets identified to date in kidney disease also play important roles in regeneration or homeostasis, design of successful therapies for CKD has been held back by safety problems that have been encountered. Anti-miRs therefore offer the promise of enhanced safety as well as efficacy.

miRs are central coordinators of gene expression and are readily targetable, particularly to the kidney and liver; therefore, there is great potential for rapid transition from identification of pathological miR targets to drugs in clinical trials. There is currently a large unmet need for AKI and CKD. The latter affects as many as 10% of the adult population, leads to kidney failure or death, and currently there are very few therapies to halt the progression of disease. Safe new treatments that target the mechanisms of disease progression are urgently required. AKI leading to rapid organ failure is one of the most rapidly growing diseases in the United States in the hospital setting. There is currently no approved treatment for AKI other than supportive care, and it frequently is a cause of substantial morbidity, and even mortality, or the development of CKD. Anti-miR delivery to the kidney in the acute setting is also a promising new therapeutic strategy.

Over the next few years it is likely that we will see evidence in humans that anti-miR oligonucleotides slow progression of kidney disease since anti-miR-21 therapy is entering clinical trials for the treatment of Alport syndrome. Additional miR targets will become established as drug targets for kidney disease, and miRs in the urine will likely prove to be robust biomarkers of kidney disease severity, progression, and potentially disease stratification.

GRANTS

The Duffield laboratory is funded by Biogen and has received grant funding from National Institutes of Health Grants DK087389, DK093493, DK094768, and TR000504, an American Heart Association grant (12040023), the University of Washington, and a sponsored research agreement with Regulus Therapeutics.

DISCLOSURES

J. S. Duffield holds a patent for use of miR21 in kidney disease.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: I.G.G., N.N., and J.S.D. performed experiments; I.G.G., N.N., and J.S.D. analyzed data; I.G.G., N.N., and J.S.D. interpreted results of experiments; I.G.G., N.N., and J.S.D. prepared figures; I.G.G. and J.S.D. drafted manuscript; I.G.G., N.N., and J.S.D. edited and revised manuscript; J.S.D. provided conception and design of research; J.S.D. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed MI, Alam M, Emelianov VU, Poterlowicz K, Patel A, Sharov AA, Mardaryev AN, Botchkareva NV. MicroRNA-214 controls skin and hair follicle development by modulating the activity of the Wnt pathway. J Cell Biol 207: 549–567, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alvarez ML, Khosroheidari M, Eddy E, Kiefer J. Role of microRNA 1207-5P and its host gene, the long non-coding RNA Pvt1, as mediators of extracellular matrix accumulation in the kidney: implications for diabetic nephropathy. PLoS One 8: e77468, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Androsavich JR, Chau BN, Bhat B, Linsley PS, Walter NG. Disease-linked microRNA-21 exhibits drastically reduced mRNA binding and silencing activity in healthy mouse liver. RNA 18: 1510–1526, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anglicheau D, Sharma VK, Ding R, Hummel A, Snopkowski C, Dadhania D, Seshan SV, Suthanthiran M. MicroRNA expression profiles predictive of human renal allograft status. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 5330–5335, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Azzouzi el H, Leptidis S, Dirkx E, Hoeks J, van Bree B, Brand K, McClellan EA, Poels E, Sluimer JC, van den Hoogenhof MMG, Armand AS, Yin X, Langley S, Bourajjaj M, Olieslagers S, Krishnan J, Vooijs M, Kurihara H, Stubbs A, Pinto YM, Krek W, Mayr M, da Costa Martins PA, Schrauwen P, De Windt LJ. The hypoxia-inducible microRNA cluster miR-199a∼214 targets myocardial PPARδ and impairs mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation. Cell Metab 18: 341–354, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baer C, Claus R, Plass C. Genome-wide epigenetic regulation of miRNAs in cancer. Cancer Res 73: 473–477, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barabas AZ, Cole CD, Lafreniere R, Weir DM. Immunopathological events initiated and maintained by pathogenic IgG autoantibodies in an experimental autoimmune kidney disease. Autoimmunity 45: 495–509, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bauernfeind F, Rieger A, Schildberg FA, Knolle PA, Schmid-Burgk JL, Hornung V. NLRP3 inflammasome activity is negatively controlled by miR-223. J Immunol 189: 4175–4181, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ben-Hamo R, Efroni S. MicroRNA regulation of molecular pathways as a generic mechanism and as a core disease phenotype. Oncotarget. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bijkerk R, van Solingen C, de Boer HC, van der Pol P, Khairoun M, de Bruin RG, van Oeveren-Rietdijk AM, Lievers E, Schlagwein N, van Gijlswijk DJ, Roeten MK, Neshati Z, de Vries AAF, Rodijk M, Pike-Overzet K, van den Berg YW, van der Veer EP, Versteeg HH, Reinders MEJ, Staal FJT, van Kooten C, Rabelink TJ, van Zonneveld AJ. Hematopoietic microRNA-126 protects against renal ischemia/reperfusion injury by promoting vascular integrity. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 1710–1722, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calin GA, Dumitru CD, Shimizu M, Bichi R, Zupo S, Noch E, Aldler H, Rattan S, Keating M, Rai K, Rassenti L, Kipps T, Negrini M, Bullrich F, Croce CM. Frequent deletions and down-regulation of micro- RNA genes miR15 and miR16 at 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 15524–15529, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campanholle G, Ligresti G, Gharib SA, Duffield JS. Cellular mechanisms of tissue fibrosis. 3. Novel mechanisms of kidney fibrosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 304: C591–C603, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campanholle G, Mittelsteadt K, Nakagawa S, Kobayashi A, Lin SL, Gharib SA, Heinecke JW, Hamerman JA, Altemeier WA, Duffield JS. TLR-2/TLR-4 TREM-1 signaling pathway is dispensable in inflammatory myeloid cells during sterile kidney injury. PLoS One 8: e68640, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature 499: 43–49, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan JA, Krichevsky AM, Kosik KS. MicroRNA-21 is an antiapoptotic factor in human glioblastoma cells. Cancer Res 65: 6029–6033, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chau BN, Xin C, Hartner J, Ren S, Castano AP, Linn G, Li J, Tran PT, Kaimal V, Huang X, Chang AN, Li S, Kalra A, Grafals M, Portilla D, MacKenna DA, Orkin SH, Duffield JS. MicroRNA-21 promotes fibrosis of the kidney by silencing metabolic pathways. Sci Transl Med 4: 121ra18, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen BF, Suen YK, Gu S, Li L, Chan WY. A miR-199a/miR-214 self-regulatory network via PSMD10, TP53 and DNMT1 in testicular germ cell tumor. Sci Rep 4: 6413, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen HY, Zhong X, Huang XR, Meng XM, You Y, Chung AC, Lan HY. MicroRNA-29b inhibits diabetic nephropathy in db/db mice. Mol Ther 22: 842–853, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen YQ, Wang XX, Yao XM, Zhang DL, Yang XF, Tian SF, Wang NS. Abated microRNA-195 expression protected mesangial cells from apoptosis in early diabetic renal injury in mice. J Nephrol 25: 566–576, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Denby L, Ramdas V, Lu R, Conway BR, Grant JS, Dickinson B, Aurora AB, McClure JD, Kipgen D, Delles C, van Rooij E, Baker AH. MicroRNA-214 antagonism protects against renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 65–80, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denby L, Ramdas V, McBride MW, Wang J, Robinson H, McClure J, Crawford W, Lu R, Hillyard DZ, Khanin R, Agami R, Dominiczak AF, Sharpe CC, Baker AH. miR-21 and miR-214 are consistently modulated during renal injury in rodent models. Am J Pathol 179: 661–672, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Denli AM, Tops BBJ, Plasterk RHA, Ketting RF, Hannon GJ. Processing of primary microRNAs by the microprocessor complex. Nature 432: 231–235, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dey N, Das F, Ghosh-Choudhury N, Mandal CC, Parekh DJ, Block K, Kasinath BS, Abboud HE, Choudhury GG. microRNA-21 governs TORC1 activation in renal cancer cell proliferation and invasion. PLoS One 7: e37366, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dey NN, Ghosh-Choudhury NN, Kasinath BSB, Choudhury GGG. TGFβ-stimulated microRNA-21 Utilizes PTEN to orchestrate AKT/mTORC1 signaling for mesangial cell hypertrophy and matrix expansion. PLoS One 7: e42316, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Du B, Ma LM, Huang MB, Zhou H, Huang HL, Shao P, Chen YQ, Qu LH. High glucose down-regulates miR-29a to increase collagen IV production in HK-2 cells. FEBS Lett 584: 811–816, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duffield JS. Cellular and molecular mechanisms in kidney fibrosis. J Clin Invest 124: 2299–2306, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eis PS, Tam W, Sun L, Chadburn A, Li Z, Gomez MF, Lund E, Dahlberg JE. Accumulation of miR-155 and BIC RNA in human B cell lymphomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 3627–3632, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fang Y, Yu X, Liu Y, Kriegel AJ, Heng Y, Xu X, Liang M, Ding X. miR-29c is downregulated in renal interstitial fibrosis in humans and rats and restored by HIF-α activation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 304: F1274–F1282, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 391: 806–811, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fu HL, Wu DP, Wang XF, Wang JG, Jiao F, Song LL, Xie H, Wen XY, Shan HS, Du YX, Zhao YP. Altered miRNA expression is associated with differentiation, invasion, and metastasis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) in patients from Huaian, China. Cell Biochem Biophys 67: 657–668, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fu Y, Zhang Y, Wang Z, Wang L, Wei X, Zhang B, Wen Z, Fang H, Pang Q, Yi F. Regulation of NADPH oxidase activity is associated with miRNA-25-mediated NOX4 expression in experimental diabetic nephropathy. Am J Nephrol 32: 581–589, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fulzele S, El-Sherbini A, Ahmad S, Sangani R, Matragoon S, El-Remessy A, Radhakrishnan R, Liou GI. MicroRNA-146b-3p regulates retinal inflammation by suppressing adenosine deaminase-2 in diabetes. Biomed Res Int 2015: 846501, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giraldez AJ, Cinalli RM, Glasner ME, Enright AJ, Thomson JM, Baskerville S, Hammond SM, Bartel DP, Schier AF. MicroRNAs regulate brain morphogenesis in zebrafish. Science 308: 833–838, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glowacki F, Savary G, Gnemmi V, Buob D, Van der Hauwaert C, Lo-Guidice JM, Bouyé S, Hazzan M, Pottier N, Perrais M, Aubert S, Cauffiez C. Increased circulating miR-21 levels are associated with kidney fibrosis. PLoS One 8: e58014, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Godwin JG, Ge X, Stephan K, Jurisch A, Tullius SG, Iacomini J. Identification of a microRNA signature of renal ischemia reperfusion injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 14339–14344, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gomez IG, MacKenna DA, Johnson BG, Kaimal V, Roach AM, Ren S, Nakagawa N, Xin C, Newitt R, Pandya S, Xia TH, Liu X, Borza DB, Grafals M, Shankland SJ, Himmelfarb J, Portilla D, Liu S, Chau BN, Duffield JS. Anti-microRNA-21 oligonucleotides prevent Alport nephropathy progression by stimulating metabolic pathways. J. Clin Invest 125: 141–146, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gregory PA, Bert AG, Paterson EL, Barry SC, Tsykin A, Farshid G, Vadas MA, Khew-Goodall Y, Goodall GJ. The miR-200 family and miR-205 regulate epithelial to mesenchymal transition by targeting ZEB1 and SIP1. Nat Cell Biol 10: 593–601, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haneklaus M, Gerlic M, Kurowska-Stolarska M, Rainey AA, Pich D, McInnes IB, Hammerschmidt W, O'Neill LAJ, Masters SL. Cutting edge: miR-223 and EBV miR-BART15 regulate the NLRP3 inflammasome and IL-1β production. J Immunol 189: 3795–3799, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harris KS, Zhang Z, McManus MT, Harfe BD, Sun X. Dicer function is essential for lung epithelium morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 2208–2213, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He F, Peng F, Xia X, Zhao C, Luo Q, Guan W, Li Z, Yu X, Huang F. MiR-135a promotes renal fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy by regulating TRPC1. Diabetologia 57: 1726–1736, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hishida A, Wakai K, Naito M, Tamura T, Kawai S, Hamajima N, Oze I, Imaizumi T, Turin TC, Suzuki S, Kheradmand M, Mikami H, Ohnaka K, Watanabe Y, Arisawa K, Kubo M, Tanaka H. Polymorphisms in PPAR genes (PPARD, PPARG, and PPARGC1A) and the risk of chronic kidney disease in Japanese: cross-sectional data from the J-MICC study. PPAR Res 2013: 980471, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kanellopoulou C, Muljo SA, Kung AL, Ganesan S, Drapkin R, Jenuwein T, Livingston DM, Rajewsky K. Dicer-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells are defective in differentiation and centromeric silencing. Genes Dev 19: 489–501, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kato M, Arce L, Wang M, Putta S, Lanting L, Natarajan R. A microRNA circuit mediates transforming growth factor-β1 autoregulation in renal glomerular mesangial cells. Kidney Int 80: 358–368, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kato M, Putta S, Wang M, Yuan H, Lanting L, Nair I, Gunn A, Nakagawa Y, Shimano H, Todorov I, Rossi JJ, Natarajan R. TGF-beta activates Akt kinase through a microRNA-dependent amplifying circuit targeting PTEN. Nat Cell Biol 11: 881–889, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kato M, Wang L, Putta S, Wang M, Yuan H, Sun G, Lanting L, Todorov I, Rossi JJ, Natarajan R. Post-transcriptional up-regulation of Tsc-22 by Ybx1, a target of miR-216a, mediates TGF-beta-induced collagen expression in kidney cells. J Biol Chem 285: 34004–34015, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kato M, Zhang J, Wang M, Lanting L, Yuan H, Rossi JJ, Natarajan R. MicroRNA-192 in diabetic kidney glomeruli and its function in TGF-beta-induced collagen expression via inhibition of E-box repressors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 3432–3437, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim Y, Roh S, Lawler S, Friedman A. miR451 and AMPK mutual antagonism in glioma cell migration and proliferation: a mathematical model. PLoS One 6: e28293, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knight SW, Bass BL. A role for the RNase III enzyme DCR-1 in RNA interference and germ line development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 293: 2269–2271, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kole R, Krainer AR, Altman S. RNA therapeutics: beyond RNA interference and antisense oligonucleotides. Nat Rev Drug Discov 11: 125–140, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kriegel AJ, Liu Y, Fang Y, Ding X, Liang M. The miR-29 family: genomics, cell biology, and relevance to renal and cardiovascular injury. Physiol Genomics 44: 237–244, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science 294: 853–858, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lai EC. Micro RNAs are complementary to 3′ UTR sequence motifs that mediate negative post-transcriptional regulation. Nat Genet 30: 363–364, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lai JY, Luo J, O'Connor C, Jing X, Nair V, Ju W, Randolph A, Ben-Dov IZ, Matar RN, Briskin D, Zavadil J, Nelson RG, Tuschl T, Brosius FC, Kretzler M, Bitzer M. MicroRNA-21 in glomerular injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 805–816, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lai WL, Yeh TH, Chen PM, Chan CK, Chiang WC, Chen YM, Wu KD, Tsai TJ. Membranous nephropathy: a review on the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. J Formos Med Assoc 114: 102–111, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lau NC, Lim LP, Weinstein EG, Bartel DP. An abundant class of tiny RNAs with probable regulatory roles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 294: 858–862, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee Y, Jeon K, Lee JT, Kim S, Kim VN. MicroRNA maturation: stepwise processing and subcellular localization. EMBO J 21: 4663–4670, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57a.Levin AA, Yu RZ, Geary RS. Antisense Drug Technology (2nd ed). Boca Raton, FL: CRC, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li D, Lu Z, Jia J, Zheng Z, Lin S. Changes in microRNAs associated with podocytic adhesion damage under mechanical stress. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst 14: 97–102, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lin CL, Lee PH, Hsu YC, Lei CC, Ko JY, Chuang PC, Huang YT, Wang SY, Wu SL, Chen YS, Chiang WC, Reiser J, Wang FS. MicroRNA-29a promotion of nephrin acetylation ameliorates hyperglycemia-induced podocyte dysfunction. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 1698–1709, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lin SL, Chang FC, Schrimpf C, Chen YT, Wu CF, Wu VC, Chiang WC, Kuhnert F, Kuo CJ, Chen YM, Wu KD, Tsai TJ, Duffield JS. Targeting endothelium-pericyte cross talk by inhibiting VEGF receptor signaling attenuates kidney microvascular rarefaction and fibrosis. Am J Pathol 178: 911–923, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lino Cardenas CL, Henaoui IS, Courcot E, Roderburg C, Cauffiez C, Aubert S, Copin MC, Wallaert B, Glowacki F, Dewaeles E, Milosevic J, Maurizio J, Tedrow J, Marcet B, Lo-Guidice JM, Kaminski N, Barbry P, Luedde T, Perrais M, Mari B, Pottier N. miR-199a-5p Is upregulated during fibrogenic response to tissue injury and mediates TGFbeta-induced lung fibroblast activation by targeting caveolin-1. PLoS Genet 9: e1003291, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Long J, Wang Y, Wang W, Chang BHJ, Danesh FR. Identification of microRNA-93 as a novel regulator of vascular endothelial growth factor in hyperglycemic conditions. J Biol Chem 285: 23457–23465, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Long J, Wang Y, Wang W, Chang BHJ, Danesh FR. MicroRNA-29c is a signature microRNA under high glucose conditions that targets Sprouty homolog 1, and its in vivo knockdown prevents progression of diabetic nephropathy. J Biol Chem 286: 11837–11848, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lv G, Shao S, Dong H, Bian X, Yang X, Dong S. MicroRNA-214 protects cardiac myocytes against H2O2-induced injury. J Cell Biochem 115: 93–101, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maubach G, Lim MCC, Chen J, Yang H, Zhuo L. miRNA studies in in vitro and in vivo activated hepatic stellate cells. World J Gastroenterol 17: 2748–2773, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Medina PP, Nolde M, Slack FJ. OncomiR addiction in an in vivo model of microRNA-21-induced pre-B-cell lymphoma. Nature 467: 86–90, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Meng F, Henson R, Wehbe-Janek H, Ghoshal K, Jacob ST, Patel T. MicroRNA-21 regulates expression of the PTEN tumor suppressor gene in human hepatocellular cancer. Gastroenterology 133: 647–658, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Metzler M, Wilda M, Busch K, Viehmann S, Borkhardt A. High expression of precursor microRNA-155/BIC RNA in children with Burkitt lymphoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 39: 167–169, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Molejon MI, Ropolo A, Re AL, Boggio V, Vaccaro MI. The VMP1-Beclin 1 interaction regulates autophagy induction. Sci Rep 3: 1055, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mott JL, Kurita S, Cazanave SC, Bronk SF, Werneburg NW, Fernandez-Zapico ME. Transcriptional suppression of mir-29b-1/mir-29a promoter by c-Myc, hedgehog, and NF-kappaB. J Cell Biochem 110: 1155–1164, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mu J, Pang Q, Guo YH, Chen JG, Zeng W, Huang YJ, Zhang J, Feng B. Functional implications of microRNA-215 in TGF-β1-induced phenotypic transition of mesangial cells by targeting CTNNBIP1. PLoS One 8: e58622, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nagalakshmi VK, Ren Q, Pugh MM, Valerius MT, McMahon AP, Yu J. Dicer regulates the development of nephrogenic and ureteric compartments in the mammalian kidney. Kidney Int 79: 317–330, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nakagawa N, Xin C, Roach AM, Naiman N, Shankland SJ, Ligresti G, Ren S, Szak S, Gomez IG, Duffield JS. Dicer1 activity in the stromal compartment regulates nephron differentiation and vascular patterning during mammalian kidney organogenesis. Kidney Int 87: 1125–1140, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nitta K, Okada K, Yanai M, Takahashi S. Aging and chronic kidney disease. Kidney Blood Press Res 38: 109–120, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Park JT, Kato M, Yuan H, Castro N, Lanting L, Wang M, Natarajan R. FOG2 protein down-regulation by transforming growth factor-β1-induced microRNA-200b/c leads to Akt kinase activation and glomerular mesangial hypertrophy related to diabetic nephropathy. J Biol Chem 288: 22469–22480, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Park SY, Lee JH, Ha M, Nam JW, Kim VN. miR-29 miRNAs activate p53 by targeting p85 alpha and CDC42. Nat Struct Mol Biol 16: 23–29, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pavlides S, Whitaker-Menezes D, Castello-Cros R, Flomenberg N, Witkiewicz AK, Frank PG, Casimiro MC, Wang C, Fortina P, Addya S, Pestell RG, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. The reverse Warburg effect: aerobic glycolysis in cancer associated fibroblasts and the tumor stroma. Cell Cycle 8: 3984–4001, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Putta S, Lanting L, Sun G, Lawson G, Kato M, Natarajan R. Inhibiting microRNA-192 ameliorates renal fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 458–469, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schober A, Nazari-Jahantigh M, Wei Y, Bidzhekov K, Gremse F, Grommes J, Megens RTA, Heyll K, Noels H, Hristov M, Wang S, Kiessling F, Olson EN, Weber C. MicroRNA-126-5p promotes endothelial proliferation and limits atherosclerosis by suppressing Dlk1. Nat Med 20: 368–376, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Seggerson K, Tang L, Moss EG. Two genetic circuits repress the Caenorhabditis elegans heterochronic gene lin-28 after translation initiation. Dev Biol 243: 215–225, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Song C, Xu Z, Jin Y, Zhu M, Wang K, Wang N. The network of microRNAs, transcription factors, target genes and host genes in human renal cell carcinoma. Oncol Lett 9: 498–506, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Su Z, Ni L, Yu W, Yu Z, Chen D, Zhang E, Li Y, Wang Y, Li X, Yang S, Gui Y, Lai Y, Ye J. MicroRNA-451a is associated with cell proliferation, migration and apoptosis in renal cell carcinoma. Mol Med Rep 11: 2248–2254, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sun M, Fang S, Li W, Li C, Wang L, Wang F, Wang Y. Associations of miR-146a and miR-146b expression and clinical characteristics in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cancer Biomark 15: 33–40, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sun YQ, Zhang F, Bai YF, Guo LL. [miR-126 modulates the expression of epidermal growth factor-like domain 7 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells in vitro]. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 30: 767–770, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Thai TH, Patterson HC, Pham DH, Kis-Toth K, Kaminski DA, Tsokos GC. Deletion of microRNA-155 reduces autoantibody responses and alleviates lupus-like disease in the Fas(lpr) mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 20194–20199, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ugalde AP, Ramsay AJ, la Rosa de J, Varela I, Mariño G, Cadiñanos J, Lu J, Freije JM, López-Otín C. Aging and chronic DNA damage response activate a regulatory pathway involving miR-29 and p53. EMBO J 30: 2219–2232, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.van Mil A, Grundmann S, Goumans MJ, Lei Z, Oerlemans MI, Jaksani S, Doevendans PA, Sluijter JPG. MicroRNA-214 inhibits angiogenesis by targeting Quaking and reducing angiogenic growth factor release. Cardiovasc Res 93: 655–665, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vergho DC, Kneitz S, Kalogirou C, Burger M, Krebs M, Rosenwald A, Spahn M, Löser A, Kocot A, Riedmiller H, Kneitz B. Impact of miR-21, miR-126 and miR-221 as prognostic factors of clear cell renal cell carcinoma with tumor thrombus of the inferior vena cava. PLoS One 9: e109877, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang B, Jha JC, Hagiwara S, McClelland AD, Jandeleit-Dahm K, Thomas MC, Cooper ME, Kantharidis P. Transforming growth factor-β1-mediated renal fibrosis is dependent on the regulation of transforming growth factor receptor 1 expression by let-7b. Kidney Int 85: 352–361, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang B, Koh P, Winbanks C, Coughlan MT, McClelland A, Watson A, Jandeleit-Dahm K, Burns WC, Thomas MC, Cooper ME, Kantharidis P. miR-200a prevents renal fibrogenesis through repression of TGF-β2 expression. Diabetes 60: 280–287, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang B, Komers R, Carew R, Winbanks CE, Xu B, Herman-Edelstein M, Koh P, Thomas M, Jandeleit-Dahm K, Gregorevic P, Cooper ME, Kantharidis P. Suppression of microRNA-29 expression by TGF-β1 promotes collagen expression and renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 252–265, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wang F, Liu M, Li X, Tang H. MiR-214 reduces cell survival and enhances cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity via down-regulation of Bcl2l2 in cervical cancer cells. FEBS Lett 587: 488–495, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang J, Gao Y, Ma M, Li M, Zou D, Yang J, Zhu Z, Zhao X. Effect of miR-21 on renal fibrosis by regulating MMP-9 and TIMP1 in kk-ay diabetic nephropathy mice. Cell Biochem Biophys 67: 537–546, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wang Q, Wang Y, Minto AW, Wang J, Shi Q, Li X, Quigg RJ. MicroRNA-377 is up-regulated and can lead to increased fibronectin production in diabetic nephropathy. FASEB J 22: 4126–4135, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wang S, Aurora AB, Johnson BA, Qi X, McAnally J, Hill JA, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. The endothelial-specific microRNA miR-126 governs vascular integrity and angiogenesis. Dev Cell 15: 261–271, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Xin Q, Li J, Dang J, Bian X, Shan S, Yuan J, Qian Y, Liu Z, Liu G, Yuan Q, Liu N, Ma X, Gao F, Gong Y, Liu Q. miR-155 deficiency ameliorates autoimmune inflammation of systemic lupus erythematosus by targeting S1pr1 in Faslpr/lpr mice. J Immunol 194: 5437–5445, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Xiong M, Jiang L, Zhou Y, Qiu W, Fang L, Tan R, Wen P, Yang J. The miR-200 family regulates TGF-β1-induced renal tubular epithelial to mesenchymal transition through Smad pathway by targeting ZEB1 and ZEB2 expression. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 302: F369–F379, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Xu P, Vernooy SY, Guo M, Hay BA. The Drosophila microRNA Mir-14 suppresses cell death and is required for normal fat metabolism. Curr Biol 13: 790–795, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Xu X, Kriegel AJ, Liu Y, Usa K, Mladinov D, Liu H, Fang Y, Ding X, Liang M. Delayed ischemic preconditioning contributes to renal protection by upregulation of miR-21. Kidney Int 82: 1167–1175, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]