Abstract

Fibroblasts play a significant role in the development of electrical and mechanical dysfunction of the heart; however, the underlying mechanisms are only partially understood. One widely studied mechanism suggests that fibroblasts produce excess extracellular matrix, resulting in collagenous septa that slow propagation, cause zig-zag conduction paths, and decouple cardiomyocytes, resulting in a substrate for cardiac arrhythmia. An emerging mechanism suggests that fibroblasts promote arrhythmogenesis through direct electrical interactions with cardiomyocytes via gap junction (GJ) channels. In the heart, three major connexin (Cx) isoforms, Cx40, Cx43, and Cx45, form GJ channels in cell-type-specific combinations. Because each Cx is characterized by a unique time- and transjunctional voltage-dependent profile, we investigated whether the electrophysiological contributions of fibroblasts would vary with the specific composition of the myocyte-fibroblast (M-F) GJ channel. Due to the challenges of systematically modifying Cxs in vitro, we coupled native cardiomyocytes with in silico fibroblast and GJ channel electrophysiology models using the dynamic-clamp technique. We found that there is a reduction in the early peak of the junctional current during the upstroke of the action potential (AP) due to GJ channel gating. However, effects on the cardiomyocyte AP morphology were similar regardless of the specific type of GJ channel (homotypic Cx43 and Cx45, and heterotypic Cx43/Cx45 and Cx45/Cx43). To illuminate effects at the tissue level, we performed multiscale simulations of M-F coupling. First, we developed a cell-specific model of our dynamic-clamp experiments and investigated changes in the underlying membrane currents during M-F coupling. Second, we performed two-dimensional tissue sheet simulations of cardiac fibrosis and incorporated GJ channels in a cell type-specific manner. We determined that although GJ channel gating reduces junctional current, it does not significantly alter conduction velocity during cardiac fibrosis relative to static GJ coupling. These findings shed more light on the complex electrophysiological interplay between cardiac fibroblasts and myocytes.

Introduction

The adult heart is composed of cardiomyocytes and a diverse population of nonmyocyte cells including: fibroblasts, endothelial cells, pericytes, immune cells, and vascular smooth muscle cells. The most abundant nonmyocyte cells, cardiac fibroblasts, form an intermingled network with cardiomyocytes and account for ∼27% of cells in the mouse heart to as much as 70% of cells in the rat heart (1, 2). Fibroblasts play a significant role in the development of electrical and mechanical dysfunction of the diseased heart. Cardiac diseases such as myocardial infarction, pressure/volume overload, and heart failure result in fibroblast accumulation and differentiation into the activated myofibroblast state. Myofibroblasts secrete and remodel extracellular matrix, causing the formation of collagenous septa that slow propagation, cause zig-zag conduction paths, and decouple cardiomyocytes, resulting in a substrate for cardiac arrhythmia (3).

Recent evidence suggests that fibroblasts may also promote arrhythmogenesis through direct electrical interactions with cardiomyocytes. Several studies have demonstrated that fibroblasts form gap junction (GJ) channels with cardiomyocytes in vitro (4, 5) and ex vivo in the SA node (6). However, contrary to previous studies, no myocyte-fibroblast (M-F) coupling was found in an ex vivo canine model of myocardial infarction (7). This controversy regarding the role of M-F coupling in vivo, has prompted the development of optogenetic strategies to investigate M-F interactions in vivo (8, 9). Because of the limitations of existing experimental models, combined computational modeling and in vitro experiments have proved valuable in illuminating the potential contributions of M-F interactions in the heart. These studies have suggested that fibroblasts may modify cardiac electrophysiology by reducing action potential duration (APD), modifying conduction velocity, and inducing spontaneous electrical activity when coupled to cardiomyocytes via GJ channels (10, 11, 12).

GJ channels allow for direct intercellular communication between neighboring cells. A GJ channel is composed of two hemichannels docked head-to-head spanning two bilayer membranes. Each hemichannel is composed of six protein subunits, termed connexins (Cx), arranged in a hexagonal pattern around a central pore (13). In general, GJ channels are described as homotypic if both hemichannels are composed of the same Cx isoform and heterotypic if the Cxs of the two hemichannels differ. In the heart, three major Cx isoforms, Cx40, Cx43, and Cx45, form GJ channels in cell-type-specific combinations.

Because each GJ channel exhibits unique static (single-channel conductance) and dynamic (voltage-sensitive gating) properties, it has been postulated that Cx type and distribution may play a functional role in cardiac conduction (14). For example, the Cxs in the heart have differing single-channel conductance and regional and cell-specific differences in Cx distribution. The single-channel conductance of Cx43 is ∼90 pS and much larger than that of Cx45, which is only ∼35 pS (15). Cx43 is highly expressed in ventricular cardiomyocytes and are coexpressed with small amounts of Cx45 in the normal heart, while atrial cardiomyocytes express Cx40 in addition to equal amounts of Cx43 and slightly higher amounts of Cx45 than ventricular cardiomyocytes (16). Moreover, changes in Cx expression are also observed during cardiac disease. For example, Cx43 is downregulated and Cx45 is upregulated during heart failure (17, 18). Cardiac fibroblasts also express Cx43 and Cx45, but with relatively higher levels of Cx45 (19, 20), suggesting that a M-F GJ channel in the ventricle may be predominantly heterotypic Cx43/Cx45 (21), and may also form homotypic Cx43 and Cx45 channels. Elucidating the functional effects of such homotypic and heterotypic GJ channels on M-F interactions is the focus of this study.

Recent work by McSpadden et al. (22) investigated the effect of Cx type on myocyte and nonmyocyte coupling and showed that nonmyocyte cells expressing Cx45 were more weakly coupled to cardiomyocytes and had more moderate effects on cardiomyocyte resting potential and conduction velocity compared to nonmyocytes cells expressing Cx43. However, due to the limitation of the experimental setup, they were not able to distinguish between effects mediated by heterotypic Cx43/Cx45 and homotypic Cx45 GJ channels. Furthermore, Desplantez et al. (23) found that increasing Cx45:Cx43 ratio in cell pairs resulted in a reduction of electrical coupling and cell-to-cell dye transfer. These studies highlight how Cx type and distribution can influence cell-to-cell interactions.

We expand upon these studies and our earlier modeling work (24) by utilizing the dynamic-clamp technique to explore the effects of homotypic and heterotypic GJ channels on M-F interactions in the context of a real cell. Dynamic clamp is a powerful tool used in electrophysiology, which allows for real-time feedback between computational models and in vitro patch-clamped cells (25). We used this approach to couple an in vitro patch-clamped guinea pig ventricular cardiomyocyte to a mathematical cardiac fibroblast electrophysiology model using GJ channel models representing distinct Cx types. Furthermore, we incorporated GJ channels in cell-type-specific combinations into a tissue sheet model of cardiac fibrosis and investigated the role of Cx type on fibroblast-mediated changes in conduction velocity.

Materials and Methods

Guinea pig ventricular myocyte isolation

Left ventricular myocytes were enzymatically isolated from the adult guinea pig heart via perfusion on a Langendorff apparatus, as described previously in Bryant et al. (26). All procedures were performed in accordance with the Weill Cornell IACUC protocol 0701–571A. In brief, adult Hartley guinea pigs (n = 4) were anesthetized using intraperitoneal injection of 120 mg/kg of sodium pentobarbital. The heart was excised, cannulated, and perfused first with Common Tyrode’s buffer: 130 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 3.5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES, 10 mM Dextrose, 2 mM CaCl2, pH 7.2 with NaOH (osmolality 288 mmol/kg) to facilitate the removal of blood, followed by calcium-free Common Tyrode’s buffer to stop contractions, and finally with Common Tyrode’s buffer containing Collagenase Type II (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ), Protease Type XIV (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 0.05 mM CaCl2. The left ventricle was dissected, minced, and further digested in Common Tyrode’s buffer containing Collagenase Type II. The final suspension of cells contained a population of single cardiomyocytes. Cells were stored in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium with 5% fetal bovine serum or in Common Tyrode’s buffer with 0.5% bovine serum albumin and 0.75 mM CaCl2. Only rod-shaped cells with striations were selected for electrophysiology studies.

Electrophysiological recordings

Whole-cell Amphotericin B (Sigma-Aldrich) perforated patch-clamp recordings were obtained at 35–37°C using a model 2400 patch-clamp amplifier (A-M Systems, Sequim, WA). Patch pipettes were pulled from 1.5-mm OD, 0.86-mm ID borosilicate glass capillary tubes (Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA) to a resistance of 1.6–2 MΩ and backfilled with pipette solution. Pipette solution contained: 113 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 5.5 mM Dextrose, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 11 mM KOH, 10 mM HEPES, 10 μM CaCl2, pH 7.1 with KOH (osmolality 289 ± 0.6 mmol/kg). Extracellular solution contained: 137 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM Dextrose, 2 mM CaCl2, pH 7.35 with NaOH (osmolality 304 ± 0.6 mmol/kg). Recordings were corrected for a liquid junction potential of −3 mV.

Dynamic-clamp experiments

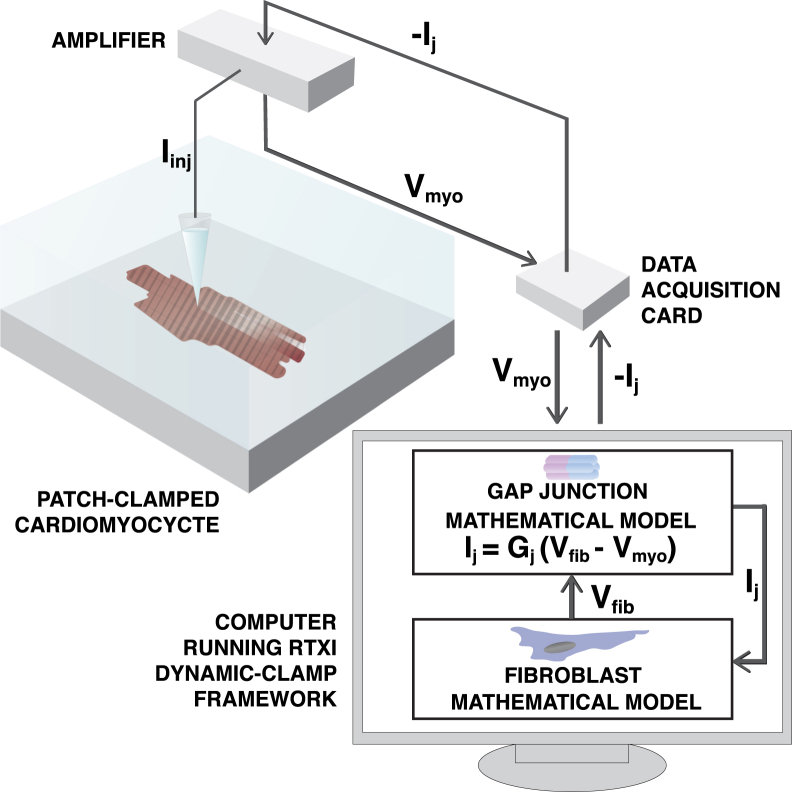

Fig. 1 shows a schematic of the dynamic-clamp feedback circuit. We patch-clamped guinea pig ventricular cardiomyocytes and used the dynamic-clamp technique to couple them to the MacCannell fibroblast electrophysiology model (27) via GJ channel models developed to represent the gating and kinetic properties of Cx43, Cx45, and Cx43/Cx45. Dynamic-clamp protocols were implemented using the Real-Time Experiment Interface (RTXI; www.rtxi.org) framework developed in our laboratory (28, 29). Before the start of dynamic-clamp recordings, the patch-clamped cardiomyocyte was paced at 2 Hz in current-clamp mode using 1.5 times the threshold stimulus pulse for 1 ms duration until it reached a stable recording. The bridge balance was used to compensate for 70–100% of the voltage drop across the access resistance, which ranged from 5.8 to 16.6 MΩ.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the dynamic-clamp technique. The dynamic-clamp technique allows for real-time feedback between computational models and in vitro patch-clamped cardiomyocytes. In this approach, an in vitro cardiomyocyte cell is patch-clamped and its membrane potential is measured and fed into the computer’s data acquisition system, simultaneously a cardiac fibroblast model is simulated in real-time. Next, a junctional current, Ij, is calculated as a function of the gap junctional conductance, Gj, and the difference between the fibroblast model voltage, Vfib, and cardiomyocyte voltage, Vmyo. Finally, the junctional current is injected back into the fibroblast model and the in vitro cardiomyocyte via the patch-clamp amplifier, resulting in a circuit as if the cardiomyocyte were directly coupled to the fibroblast model. To see this figure in color, go online.

The capacitance of the fibroblast model was fixed at 6.3 pF, as reported in the model from MacCannell et al. (27), while the capacitance of the in vitro guinea pig cardiomyocyte varied from cell-to-cell. To ensure that the relative size of the in vitro cell and the fibroblast electrophysiology model were similar across cells, we determined the capacitance of the cardiomyocyte in voltage-clamp mode. We then used a scaling factor to scale the junctional current injected into the cardiomyocyte such that the effective size of the cell is equivalent to our dynamic-clamp simulations described below. The dynamic-clamp protocol consists of 40 uncoupled beats with dynamic clamp off, followed by 40 coupled beats with dynamic clamp on (i.e., coupling to the fibroblast electrophysiology model via a GJ channel model). This protocol was then repeated for each of the GJ channel models described below.

Dynamic-clamp simulations

To provide mechanistic insight into which parameters play a key role in modifying action potential (AP) morphology during M-F coupling, we performed simulations of our dynamic-clamp experiments. The published guinea pig ventricular myocyte model (LRd2009) of Livshitz and Rudy (30, 31) differs significantly in AP morphology and APD compared to our control experimental data and therefore has a limited ability to predict results from our dynamic-clamp experiments. To overcome this limitation, we generated a cell-specific model using a genetic algorithm optimization procedure similar to that of Groenendaal et al. (32) to scale maximal conductance parameters (within a range of 0.01–2.9 times the published values) of the LRd2009 model to fit our experimental data. We focused on optimization of the maximal conductances based on the assumption that most cell-to-cell variability is due to different expression levels of ion channels, represented by maximal conductance parameters in the model, while model kinetics are more conserved across healthy cells. We used current-clamp recordings that consisted of a train of 40 APs during pacing at a cycle length of 500 ms as our target cell behavior. The optimization procedure minimizes the error between the experimental data and the model voltage. This error is defined as the sum-of-squared-errors (SSE):

| (1) |

where Vdata is the experimentally recorded myocyte voltage, Vmodel is the model output voltage, and L is the total number of data points sampled. The result of the optimization is a set of parameters for the calibrated cell-specific model.

To simulate the dynamic-clamp experiments, we replaced the in vitro cardiomyocytes in Fig. 1 with a calibrated cell-specific model and coupled it to the fibroblast mathematical model via a GJ channel model (see Fig. 2 C) as described in Brown et al. (24). Briefly, the membrane voltages of the myocyte (Vmyo) and the fibroblast (Vfib) are derived from Eqs. 2 and 3, respectively. Cmyo and Cfib are the membrane capacitance and Imyo and Ifib are the total ionic current flowing through the ion channels, pumps, and exchangers. N is the number of fibroblast models coupled to a single cardiomyocyte model:

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

The junctional current, Ij, is calculated using Eq. 4, where the junctional conductance, Gj, is dependent on the GJ model used (either static or dynamic). In the static model, Gj is a constant conductance. In the dynamic model, Gj is based on the model of Vogel and Weingart (33), where the conductance is dependent on the fraction of GJ channels in a given state and their corresponding conductance and the number of GJ channels, Nchans, as shown in Eq. 5 and detailed in Fig. 2 and Development of Homotypic and Heterotypic GJ Channel Models (see below).

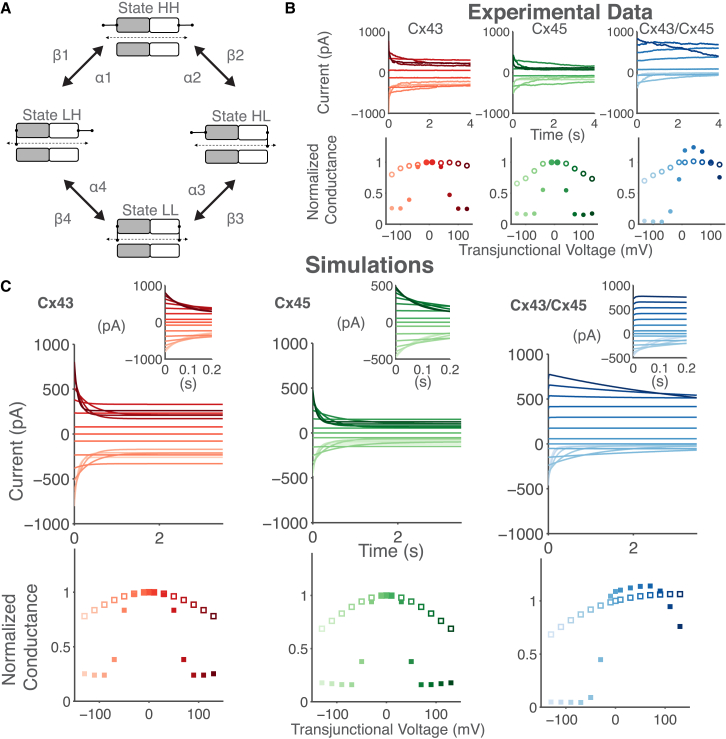

Figure 2.

Mathematical modeling of homotypic Cx43, Cx45, and heterotypic Cx43/Cx45 GJ channels using the Vogel and Weingart model. (A) The schematic of the GJ channel model consists of two hemichannels connected in series, with each hemichannel containing a voltage-sensitive gate. Each hemichannel transitions between a high (H) and low (L) nonzero conductance state gated by the transjunctional voltage (Vj). The gates are functionally independent, leading to four conformational states: HH, HL, LH, and LL. (B) Dual whole-cell patch clamp experimental recordings of transfected human HeLa cells pairs expressing rat Cx43 (left-column), mouse Cx45 (center-column), and their heterotypic Cx43/Cx45 combination (right-column) reproduced from Desplantez et al. (41) with permission of Springer. (Top) Junctional current recorded at Vj = ±10, ±40, ±70, ±100, and ±130 mV. (Bottom) Mean normalized instantaneous (○) and steady-state (●) conductance as a function of Vj. Shading of currents corresponds to shading of conductance, with darker shades representing increasingly positive Vj values. (C) Parameters of the Vogel and Weingart model (42) were modified to reproduce key features of the experimental data in (B). (Top) Simulations of the junctional current of 100 Cx43 channels (left), 250 Cx45 channels (center), and 100 Cx43/Cx45 channels (right) at Vj steps from −130 to 130 mV in 20-mV increments. (Insets) Current responses to Vj for shorter timescales. (Bottom) Normalized instantaneous (□) and steady-state (▪) conductance as a function of Vj. To see this figure in color, go online.

Tissue model implementation

A 10 × 2 mm two-dimensional (2D) tissue sheet model was constructed using a staggered bricklike structure. We simulate cardiac fibrosis using random fibroblast insertion into the 2D sheet with increased F:M ratio representing increased degrees of cardiac fibrosis. The myocyte electrophysiology was simulated using the human ventricular myocyte model of Grandi et al. (34, 35) modified by the addition of INaL and the fibroblast electrophysiology was simulated using the fibroblast model of MacCannell et al. (27). GJ channel models were assigned in a cell-type-specific manner: Cx43 for myocyte-myocyte (M-M) coupling, Cx45 for fibroblast-fibroblast (F-F) coupling, and Cx43, Cx45 or Cx43/Cx45 for myocyte-fibroblast (M-F) coupling, as indicated. The tissue structure was discretized into a 800 × 40 grid of spatial nodes measuring 25 × 25 μm. A myocyte was represented by five grid points and a capacitance of 125 pF; a fibroblast was represented by a single grid point and a capacitance of 25 pF; and the degree of tissue fibrosis was generated by assigning a target F:M ratio as described in Xie et al. (36). The tissue simulation was implemented using a discrete isopotential cell model representation (37) using the following equation:

| (6) |

where i and k represent the index of cell i and its neighboring cell k. G(i, k) represents the junctional conductance between cell i and cell k, which is dependent on the GJ model used (either static or dynamic). Thus, each myocyte cell is connected to neighboring myocytes or fibroblasts cells via discrete GJ models positioned at the shared borders between neighboring cells, having nn nearest neighbors. For M-M coupling, the junctional conductance of longitudinal GJ channels was set to 200 nS and transverse GJ channels were set to 100 nS, as used in similar modeling studies (38, 39). For F-F and M-F coupling, the junctional conductance was 3 nS, which is within the range of 0.3–8 nS reported by Rook et al. (40). Differential equations were solved using the forward Euler method, no flux boundary conditions, and a time step of 0.005 ms. The code was parallelized using OpenMP (www.openmp.org) and run on multicore machines (PowerEdge R410s/R900, 16–24 cores, 12–128 GB memory; Dell, Round Rock, TX).

Results

Development of homotypic and heterotypic GJ channel models

We developed mathematical models of homotypic Cx43, homotypic Cx45, and heterotypic Cx43/Cx45 GJ channels as these are the most relevant mediators of M-F coupling in the ventricles. Fig. 2 illustrates the basic gating properties of these GJ channel models. In general, the GJ channel conductance (Gj) is both time- and transjunctional voltage (Vj)-dependent. The top graphs in Fig. 2 B show the junctional current recorded from cell pairs in response to Vj steps of ±10, ±40, ±70, ±100, and ±130 mV, and demonstrates that the junctional current inactivates to a steady-state value in response to an applied Vj. The rate of inactivation is faster for large positive or negative Vj steps. The bottom graphs in Fig. 2 B show the normalized (i.e., to Vj = 0 mV) instantaneous (open circles) and steady-state (solid circles) Gj versus Vj relationship. The instantaneous Gj versus Vj relationship is approximately linear for small Vj values but becomes nonlinear with larger Vj values. Moreover, the Vj-dependence is symmetric for homotypic channels but asymmetric for heterotypic channels (41).

We used the four-state mathematical model of vertebrate GJ channels by Vogel and Weingart (33) as our basis model because it accounts for the voltage-sensitive gating and inactivation kinetics of GJ channels. This model was also computationally efficient, which is important for the dynamic-clamp experiments, whose accuracy is dependent on low latency between voltage measures from the patch-clamped cardiomyocytes and calculations of current injections from the computational models. A schematic of the Vogel and Weingart model (33) is shown in Fig. 2 A. It consists of two hemichannel models connected in series with each hemichannel containing a voltage-sensitive gate that transitions between a high (H) and a low (L) conductance state. The gates function independently, leading to four states of the GJ channel model: HH, HL, LH, and LL. State HH represents the main open state, γopen, states HL and LH represent the subconductance or residual state, γres, of the channel, and state LL represents the lowest conductance state with both hemichannels partially closed (42). We used least-squares curve fitting and parameter tuning to fit the model to the experimental data from Desplantez et al. (41) (Fig. 2 B), with initial parameter constraints based on previous electrophysiology and computational modeling studies (43, 44, 45, 46).

Fig. 2 C shows simulations of the developed Cx43, Cx45, and Cx43/Cx45 GJ channel models. Their corresponding parameters are listed in Table 1. The top graphs in Fig. 2 C shows junctional current responses to Vj steps from −130 to 130 mV in 20-mV increments and the bottom graphs demonstrate the Gj versus Vj of the GJ channel models. The Cx-specific models in Fig. 2 C reproduce key features of the experimental data. For example, Cx45 is more voltage-sensitive than Cx43. This behavior is demonstrated by the steeper decline in the junctional current (compare Fig. 2 C, top-left and top-center) and the smaller half-maximal inactivation of Cx45 of 46 mV compared to that of Cx43, which is 65 mV according to the Gj-Vj plot (compare Fig. 2 C, bottom-left and bottom-center). The main open state γopen can be calculated as the sum of conductors in series using the equation: , which results in a value of 79.3 pS for the Cx43 model, 35.8 pS for the Cx45 model, and 56.7 pS for the Cx43/Cx45 model, all of which are within the range of experimentally measured values of 60–118 pS, 26–32 pS (47), and 55–65 pS (44), respectively. The Cx43/Cx45 model also reproduces the asymmetric voltage sensitivity, with enhanced voltage sensitivity at negative Vj. It is important to note that the Cx43/Cx45 model behavior is not simply a summation of the Cx43 and Cx45 hemichannel models. This is in line with evidence that the docking of heterotypic GJ channels results in conformational changes in the component Cx43 hemichannel and Cx45 hemichannel (44).

Table 1.

Connexin Model Parameters

| Parameters | Units | Cx43 | Cx45 | Cx43/Cx45 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mV | 156.2 | 125.38 | 99.95 | |

| mV | 218.7 | 299.23 | 351.3 | |

| pS | 158.5 | 71.518 | 140 | |

| pS | 14 | 4.7646 | 11.42 | |

| α1 | s−1 | 167.4 | 144.1 | 264.3 |

| β1 | s−1 | 0.02338 | 0.02064 | 0.000951 |

| mV | 9.926 | 6.989 | 11.57 | |

| mV | 6.152 | 5.235 | 7.314 | |

| mV | 156.2 | 125.38 | 844.9 | |

| mV | 218.7 | 299.23 | 603.5 | |

| pS | 158.5 | 71.518 | 95.38 | |

| pS | 14 | 4.7646 | 2.09 | |

| s−1 | 167.4 | 144.1 | 77.3 | |

| β2 | s−1 | 0.02338 | 0.02064 | 0.02637 |

| mV | 9.926 | 6.989 | 2.235 | |

| mV | 6.152 | 5.235 | 7.674 | |

| Nchans | — | 13 | 28 | 19 |

| — | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.91 | |

| — | 6.56E-07 | 0.00043905 | 0.0606 | |

| — | 4.44E-14 | 0.00040637 | 7.063E-06 | |

| — | 4.44E-14 | 7.63E-05 | 0.02437 |

Myocyte-fibroblast coupling using dynamic clamp

Using the dynamic-clamp technique, we investigated whether the unique time- and Vj-dependent profiles of Cx43, Cx45, and Cx43/Cx45 GJ channels modify M-F coupling. A schematic of the dynamic-clamp experimental setup is presented in Fig. 1. To facilitate direct comparisons between the effects of the different Cx types on AP morphology and APD, multiple coupling protocols were performed on a single in vitro cardiomyocyte (see Materials and Methods). Because the GJ channel models vary in both single-channel conductance and Vj-dependent gating, we distinguish the effects of Vj-dependent gating by normalizing the resting channel conductance (i.e., at Vj = 0 mV) of the Cx specific models to the magnitude of the static model conductance.

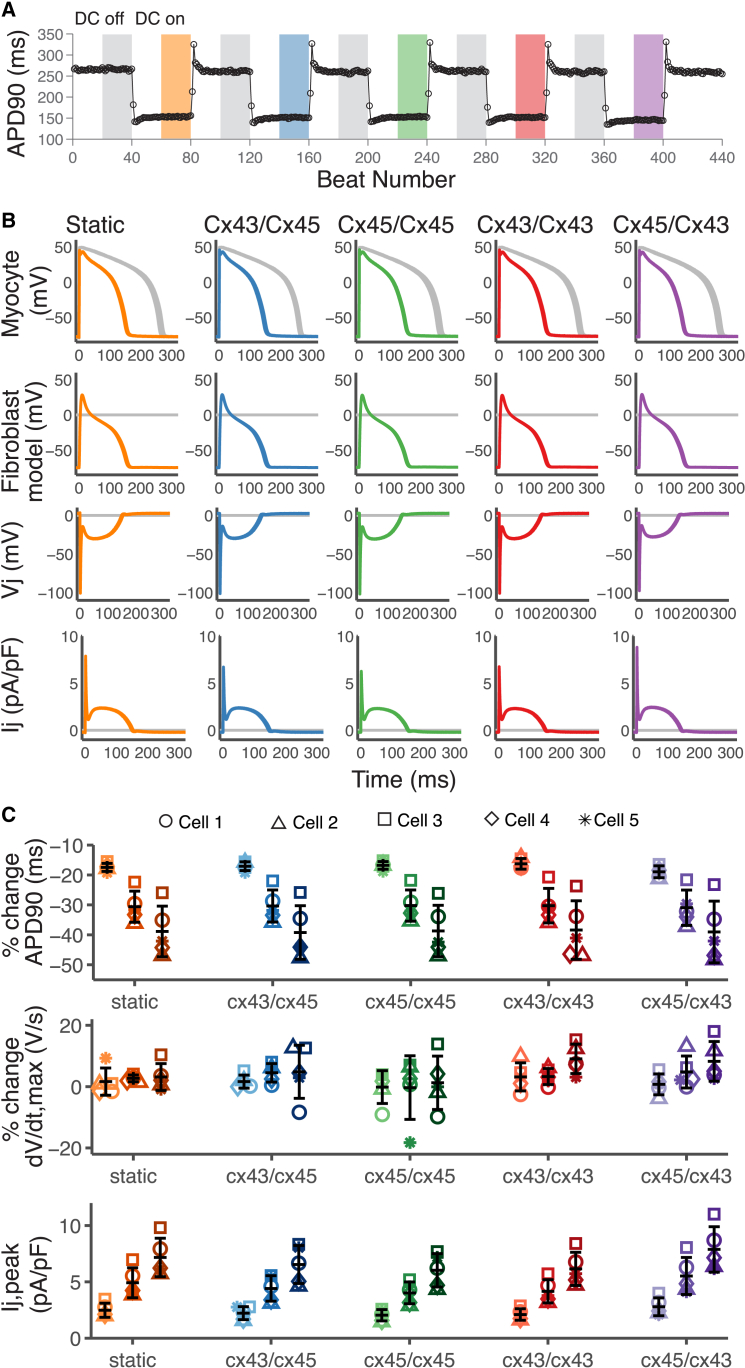

Fig. 3 shows representative results of coupling an in vitro guinea pig ventricular myocyte to the MacCannell fibroblast model via four different Cx specific GJ channel models: Cx43, Cx45, Cx43/Cx45, Cx45/Cx43, and a static GJ model, using the dynamic-clamp technique. The Cx45/Cx43 model is the reverse orientation of the Cx43/Cx45 GJ channel model presented in Fig. 2 C (see Table 2 for Cx orientation). Fig. 3, A and B, represents M-F coupling during a high degree of fibrosis (F:M ratio 6:1). Fig. 3 A shows the APD versus beat number during the course of the experiment. When the dynamic clamp was turned on, the fibroblast model was coupled to the in vitro cardiomyocyte via a GJ channel model. This resulted in a reduction in the cardiomyocyte APD. This is due to the fibroblast acting as a current sink during the AP resulting in an early repolarization. The magnitude of the APD reduction is not significantly dependent on the time- and Vj-dependent properties of the GJ channel model. The degree of reduction was similar for Cx43, Cx45, and Cx43/Cx45. Reversing the orientation of the heterotypic Cx43/Cx45 model also had similar effects on the cardiomyocyte APD during the M-F coupling schemes tested.

Figure 3.

Dynamic-clamp recordings using in vitro guinea pig ventricular cardiomyocytes. (A and B) Example of dynamic-clamp (DC) recordings from a single cell coupled to six fibroblast models (high fibrosis) with 2 nS conductance, Gj. The protocol consists of 40 uncoupled beats with DC off, 40 coupled beats with DC on (i.e., coupling to the fibroblast model via 4 Cx models: Cx43, Cx45, Cx43/Cx45, and Cx45/Cx43, and a constant conductance static model). The Gj of the Cx model at Vj = 0 mV was scaled to the static model conductance. (A) APD90 versus beat number; it shows a reduction in APD when the cell is coupled to the fibroblast model (color bars). (B) Overlay of voltage traces of the last 20 beats in each 40-beat segment (bars in A), showing the effects of DC coupling on AP morphology. (Row 1) Myocyte voltage, (row 2) fibroblast model voltage, (row 3) transjunctional voltage , and (row 4) junctional current. Coupling via the scaled Cx models results in similar changes in AP morphology compared to the static model. (C) Percent change in APD90, dV/dtmax, and the maximum junctional current (Ij,peak) compared to the previous uncoupled segment (DC off) for cell 1 (○), cell 2 (△), cell 3 (□), cell 4 (⋄), and cell 5 (∗). Darker shades represent increasing F:M ratio 2:1 (light), 4:1 (medium), and 6:1 (dark). All five GJ models showed similar trends: increased Ij,peak, no change dV/dtmax, and reduction in APD90 with increasing F:M ratio. Error bars represent SD. To see this figure in color, go online.

Table 2.

Orientation of GJ Channel Models

| Model | Myocyte connexin | Fibroblast connexin |

|---|---|---|

| Cx43 | Cx43 | Cx43 |

| Cx45 | Cx45 | Cx45 |

| Cx43/Cx45 | Cx43 | Cx45 |

| Cx45/Cx43 | Cx45 | Cx43 |

Fig. 3 B is an overlay of the recorded in vitro cardiomyocyte voltage trace and the fibroblast model voltage trace in the regions of the protocol highlighted in Fig. 3 A. The difference between the myocyte and fibroblast voltage trace (Vj) and the junctional current (Ij) is also presented. During the upstroke of the AP, the transjunctional voltage decreases rapidly (to ∼−100 mV) as the myocyte quickly depolarizes. This large Vj is well within the range of Gj inactivation for the Cx43, the Cx45, and the Cx43/45 combinations (Fig. 2). Therefore, GJs begin to inactivate during the myocyte AP upstroke, causing reductions in the early peak of the M-F junctional current compared to the static model. However, due to the coupling-induced depolarization of the fibroblasts, the large Vj value is only attained for a duration that is much shorter than the timescale of Gj inactivation (insets in Fig. 2 C), thus limiting the effect of inactivation. Reversing the orientation of the Cx43/Cx45 model results in an increase in the early peak of the M-F junctional current, demonstrating the rectifying behavior of this heterotypic channel. The asymmetry of the Gj versus Vj relationship (Fig. 2 C) facilitates current flow from the Cx45-expressing cell to the Cx43-expressing cell but impedes flow in the opposite direction. During the plateau of the AP, Vj is −15 to −30 mV. In this Vj range there is little inactivation of the Cx43 and Cx45 even at steady state (Fig. 2 C). For Cx43/Cx45, the steady-state is reduced for this voltage range, but inactivation is very slow, indeed much slower than the duration of the AP plateau (Fig. 2 C inset), leading to only little reduction in Gj.

We performed the dynamic-clamp experiments on four additional ventricular cardiomyocytes from the guinea pig heart and determined the effects on APD90, dV/dtmax, and Ij,peak (i.e., the early peak of the junctional current). In Fig. 3 C, we varied the F:M ratio to explore the effects of Cx type during three different degrees of cardiac fibrosis: low fibrosis (F:M ratio 2:1), medium fibrosis (F:M ratio 4:1), and high fibrosis (F:M ratio 6:1). The percent change is calculated relative to the immediately preceding protocol step with dynamic clamp off. The percent change in APD shows a trend of increasing APD reduction with increasing levels of fibrosis, but little change in dV/dtmax. Similar trends were observed across all five GJ channel models. Ij,peak increases with higher degrees of fibrosis due to the larger current sink provided by the increased number of fibroblast models coupled to a single cardiomyocyte. While the differences in Ij,peak between Cx types did not reach statistical significance, there is a trend of Cx45/Cx43 resulting in increased Ij,peak compared to the static model, while the other Cx types resulted in a reduction in Ij,peak. These results indicate that during M-F coupling, the time- and Vj-dependent gating of GJ channels only plays a role during the upstroke of the AP, when Vj is large.

Simulations of dynamic-clamp experiments using a cell-specific electrophysiology model

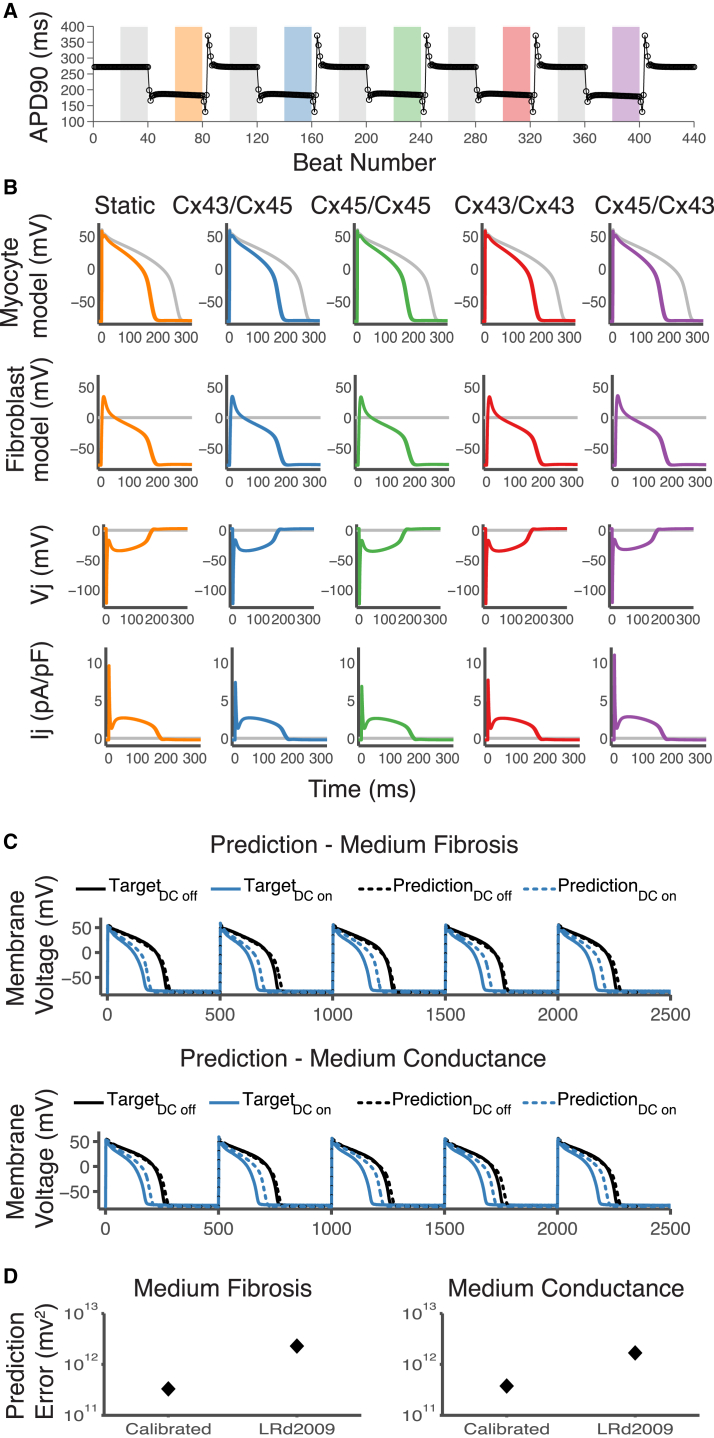

To provide mechanistic insight into the underlying parameters that play a key role in M-F coupling, we performed simulations of our dynamic-clamp experiments using a cell-specific electrophysiology model. To develop the cell-specific model, we selected a train of 40 APs from our experimental data as the target cell behavior and used a genetic algorithm optimization technique to fit maximal conductance parameters to the experimental data using a strategy similar to Groenendaal et al. (32) (see Materials and Methods for details). Fig. 4, A and B, shows the results of using this strategy to develop an electrophysiology model for the cell in Fig. 3 B. The simulation was generated by using the same protocol performed on the in vitro cardiomyocyte. The APD of the calibrated model is a better match to the APD of the experimental data compared to the published LRd2009 model whose APD at a cycle length of 500 ms is ∼130 ms (30) (Fig. 4). In Fig. 4 B, an overlay of the uncoupled and the coupled voltage responses of the cell-specific model and fibroblast model mediated by GJ channels of each Cx type is shown. The results are qualitatively similar to the results of the in vitro cell. To test for model improvement in predicting behavior during M-F coupling, we compared the predictions of the cell-specific model and the default LRd2009 model to two new sets of experimental data (Fig. 4 C). Fig. 4 D shows that the calibrated model results in a reduced prediction error for both sets of data.

Figure 4.

Simulations of dynamic-clamp recordings using a cell-specific model. (A and B) Results of cell-specific model simulation using the same protocol as in Fig. 3, A and B. (A) APD90 versus beat number; it shows a reduction in APD when the cell-specific model is coupled to the fibroblast model (color bars). (B) Overlay of voltage traces of the last 20 beats in each 40-beat segment (bars in A), showing the effects of coupling on AP morphology. (Row 1) Myocyte model voltage, (row 2) fibroblast model voltage, (row 3) transjunctional voltage , and (row 4) junctional current. (C) Prediction of the cell-specific model during coupling to four fibroblast models with 2 nS conductance (Medium Fibrosis) (top) and 2 fibroblasts at 4 nS conductance (Medium Conductance) (bottom). TargetDC off is the target experimental results during pacing of the in vitro guinea pig cardiomyocyte at a cycle length of 500 ms with dynamic clamp off. TargetDC on is the target experimental results during dynamic-clamp coupling of the in vitro cell to the fibroblast models with the Cx43/Cx45 GJ model. (D) The error was calculated as the sum of squared errors of the difference between the average of 20 beats during pacing minus the average of 20 beats during coupling during medium fibrosis and medium conductance coupling. To see this figure in color, go online.

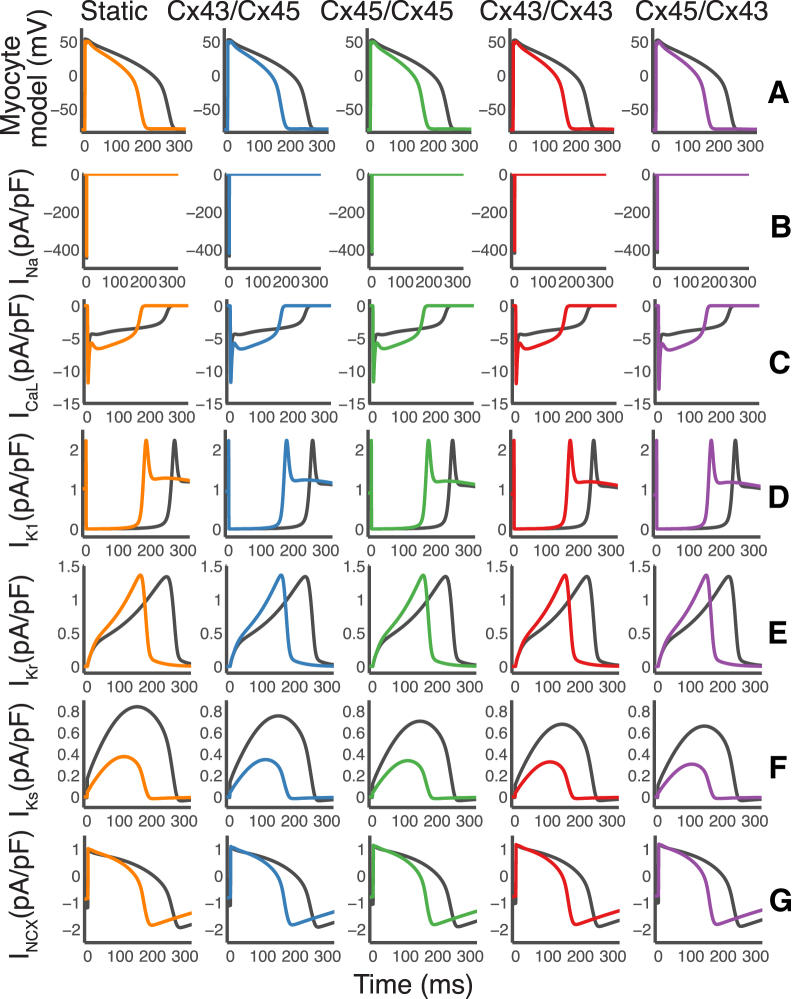

Previous computational studies have demonstrated that several ionic currents are modified during M-F coupling (48). In Fig. 5, we plotted the changes in underlying currents in response to M-F coupling. The peak of the sodium current, INa, is only slightly reduced. The late phase of the L-type calcium current, ICaL, is increased. The peak of the slow delayed rectifier current, IKs, was greatly reduced. Changes in IK1, INCX, and IKr were also observed due to the change in the AP waveform.

Figure 5.

Plots of underlying current response during M-F coupling using a cell-specific electrophysiology model. The cell-specific model from Fig. 4 was coupled to six fibroblast models (high fibrosis) with 2 nS conductance and the underlying current responses were recorded. (A) Corresponding AP traces from Fig. 4. (B) The peak of the sodium current, INa, is slightly reduced. (C) The late phase of the L-type calcium current, ICaL, is increased. (D) The inward rectifying potassium current IK1 was shortened along with the AP waveform. (E) The rapid delayed rectifier potassium current, IKr, showed shortening along with the AP waveform. (F) The peak of the slow delayed rectifier potassium current, IKs, is greatly reduced. (G) The sodium calcium exchanger current, INCX, is also shortened due to changes in the AP waveform. To see this figure in color, go online.

Effects of myocyte-fibroblast Cx type on impulse propagation during cardiac fibrosis

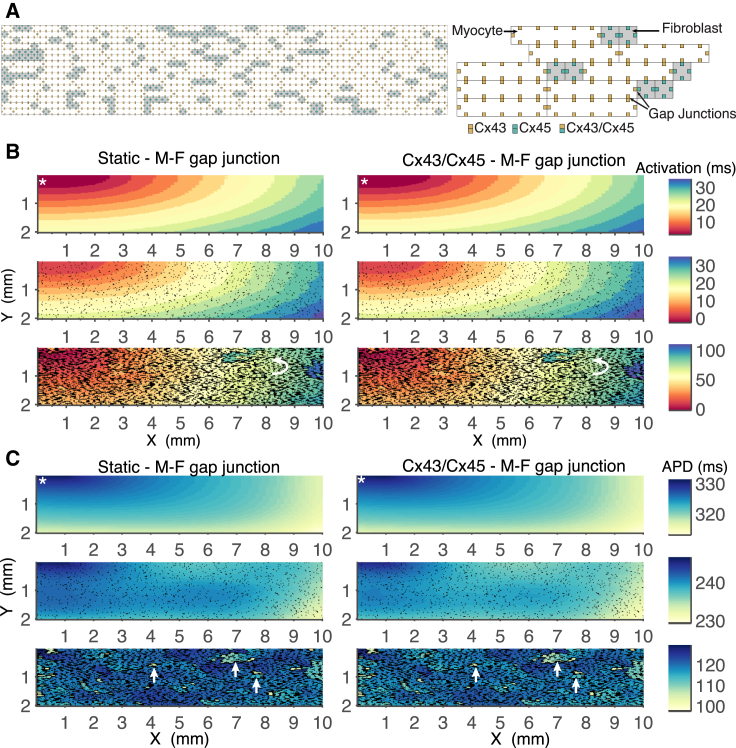

It has been proposed that the time- and voltage-sensitive gating of homotypic and heterotypic GJ channels may play an increased role in certain regions of the heart during cardiac disease (16, 43). We investigated whether M-F coupling mediated by Cx43, Cx45, or Cx43/Cx45 GJ channels would have an effect on impulse propagation and conduction velocity during cardiac fibrosis. Due to the high computational cost of implementing a large tissue sheet model with discrete GJ channels, we simulated a 10 × 2 mm tissue sheet and incorporated GJ channel models in a cell-specific manner (see Materials and Methods for details). The structure of the tissue sheet model is illustrated in Fig. 6. Fig. 6 A, left, shows a segment of the tissue sheet structure with the staggered bricklike arrangement of the cardiomyocytes depicted by white rectangles interspersed with cardiac fibroblasts depicted by gray squares.

Figure 6.

(A) Schematic representation of the tissue model structure. Myocytes are represented by the white brick-like structures and fibroblasts are represented by grey squares and are 1/5 the size of cardiomyocytes. GJ channels are represented by the smaller squares located at the border between neighboring cells. Myocyte cells are coupled via Cx43 GJ channels, fibroblast cells are coupled via Cx45 GJ channels, and M-F coupling is via Cx43/Cx45 GJ channels, as indicated. (B) Comparison of activation map between static M-F coupling and Cx43/Cx45 M-F coupling. The top panel shows the control simulation during no fibrosis. The middle panel shows simulations during a 0.2:1 F:M ratio. The bottom panel shows simulations during a 2.8:1 F:M ratio. Arrows indicate regions of local conduction block and retrograde conduction. (C) Comparison of APD map between static M-F coupling and Cx43/Cx45 M-F coupling. The top panel shows the control simulation during no fibrosis where APD prolongation is seen around the pacing site. The middle panel shows a 0.2:1 F:M ratio and illustrates the overall reduction in APD due to fibroblast insertion. The bottom panel shows a 2.8:1 F:M ratio and markedly increased heterogeneity in APD. Arrows indicate clusters of cardiomyocytes with reduced APD. The stimulus site is indicated by the white asterisk. To see this figure in color, go online.

The arrangements of the GJ channels are illustrated in Fig. 6 A, right, by the smaller squares at the shared borders between neighboring cells. In Fig. 6 B, we compare activation time during M-F coupling mediated by static GJ models versus Cx43/Cx45 GJ models. The top panel demonstrates the control simulation during no fibrosis. The stimulus site was at the top-left corner of the tissue sheet. The activation map is smooth despite the staggered structure of the tissue sheet. The middle panel shows a 0.2:1 F:M ratio, where the fibroblasts are relatively dispersed in the tissue sheet. There is relatively little disruption in the smoothness of the activation map. The bottom panel shows a 2.8:1 F:M ratio, which is equivalent to a patchy fibrosis morphology, where the cardiac fibroblast clusters result in decoupling of cardiomyocytes in the longitudinal and transverse directions (3). The activation map is very heterogeneous, with areas of local conduction block and retrograde conduction shown by the curved arrow. The results show that the Cx43/Cx45 and other Cx phenotypes (not shown) have similar conduction properties to that of the static M-F GJ model, suggesting that the time- and Vj-dependent gating properties do not play a significant role in modifying activation time.

In Fig. 6 C, we compare the cardiomyocyte APD during M-F coupling mediated by static GJ models versus Cx43/Cx45 GJ models. In the top panel, the APD is prolonged around the pacing site as expected (49), and ranges from 315 to 330 ms when no fibrosis is present. The middle panel illustrates the overall reduction in APD to a range of 235–245 ms due to the insertion of fibroblasts into the tissue sheet. The bottom panel shows the markedly increased heterogeneity in APD due to enhanced fibrosis; the increased occurrence of clusters of cardiomyocytes with reduced APD as indicated by the arrows.

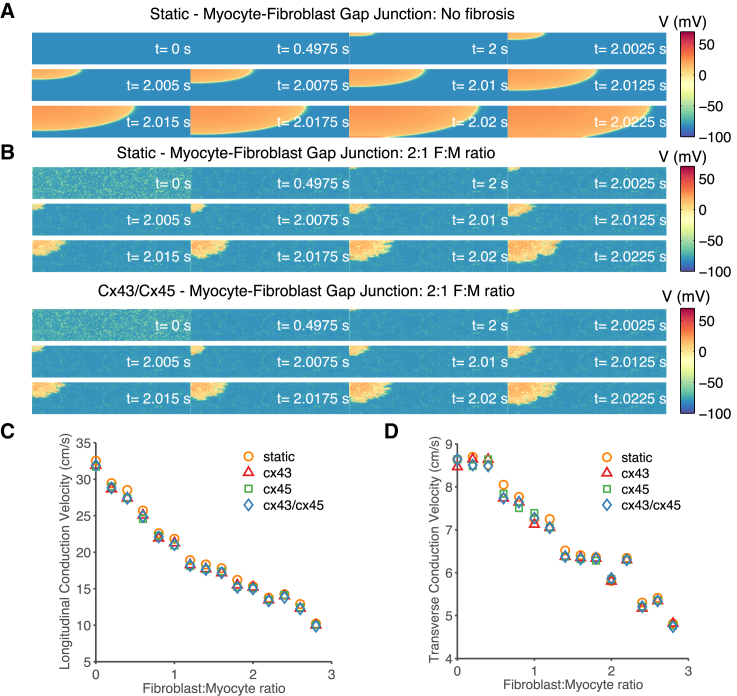

Fig. 7 illustrates the effects of increased cardiac fibrosis on conduction velocity. In the absence of fibroblasts (Fig. 7 A), the wavefront is relatively smooth. Increasing the degree of fibrosis to 2:1 F:M ratio (Fig. 7 B) resulted in a heterogeneous wavefront of propagation as well as slowed conduction across the tissue sheet. The propagation of the Cx43/Cx45 M-F coupling and other Cx types (not shown) were similar to the static GJ model representation, suggesting that time- and Vj-dependent gating of the GJ channels does not play a significant role in conduction velocity. Fig. 7, C and D, shows the conduction velocity measured between 25 and 75% of the tissue sheet length in both the transverse and longitudinal directions. It showed a 50% reduction in the longitudinal conduction velocity and a 30% reduction in transverse conduction velocity when comparing no fibrosis to 2:1 F:M ratio. In Fig. 7 D at low F:M ratio (0.5–1) there are small differences in the transverse conduction for the Cx45 phenotypes. However, the conduction velocity is essentially independent of the type of M-F GJ channel model.

Figure 7.

Effects of M-F Cx phenotype on conduction velocity. The stimulus was applied to the top-left corner of the tissue sheet. Each panel shows snapshots of the membrane voltage at the indicated time points. (A) Homogenous membrane potential of the cardiomyocytes and smooth impulse propagation. (B) Comparison of membrane voltage between static M-F coupling (top) and Cx43/Cx45 M-F coupling (bottom) with a 2:1 F:M ratio of medium fibrosis. At t = 0 s, before the start of the simulation the fibroblasts are relatively depolarized compared to the cardiomyocytes. At t = ∼0.5 s, the coupled myocytes and fibroblasts reach a new equilibrium potential where the myocytes are depolarized and the fibroblasts are hyperpolarized compared to t = 0 s. The wavefront is very heterogeneous and longitudinal conduction velocity is reduced by 50%. (C and D) Comparison of longitudinal and transverse conduction velocity as a function of F:M ratio, for differing M-F GJ channel models. There is a small reduction in the conduction velocity across all degrees of fibrosis, but there is very little difference between M-F coupling mediated by the three different Cx types. To see this figure in color, go online.

Discussion

Using a combined computational modeling and dynamic-clamp experimental approach, we investigated the role of homotypic and heterotypic GJ channels in M-F coupling. We developed mathematical models for homotypic Cx43, homotypic Cx45, and heterotypic Cx43/Cx45 GJ channels, the most likely mediators of M-F coupling. Using the dynamic-clamp technique, we coupled in vitro guinea pig ventricular cardiomyocytes to fibroblast electrophysiology models via the developed Cx type-specific models and compared their effects on the cardiomyocyte AP morphology. We then developed a cell-specific model of the dynamic clamped cell using a genetic-algorithm-based optimization technique and analyzed the underlying currents that were perturbed during M-F coupling. Finally, we investigated whether the time- and voltage-dependent gating of GJ channels played a significant role in modifying fibroblast mediated changes in conduction velocity.

The developed Cx type-specific GJ channel models reproduced the single-channel conductance properties and the time- and voltage-dependent gating of the Cx43, Cx45, and Cx43/Cx45 GJ channels. Because previous studies have demonstrated that single channel conductance alone modifies M-F coupling (27, 36), we focused on investigating the contribution of the time- and voltage-dependent gating of GJ channels on M-F coupling. When the in vitro guinea pig ventricular myocyte was coupled to a fibroblast electrophysiology model using the static GJ model, it resulted in a reduction in APD, as shown previously in a recent dynamic-clamp study (10). Replacing the static GJ model with one of our developed Cx-specific GJ models featuring time- and voltage-dependent gating resulted in similar changes in the AP morphology. This suggests that GJ channel gating does not play a significant role in M-F coupling. This is likely due to the slow time constants of the inactivation kinetics of the GJ channel and to the small transjunctional voltage between the myocyte and fibroblast during most of the AP. These factors results in the GJ channel operating predominantly on the instantaneous portion of the Gj versus Vj curve (see Fig. 2, B and C). The main differences between the static model and the Cx-specific GJ models was during the upstroke of the AP, when the early peak of the junctional current was reduced in response to the large transjunctional voltage between the myocyte and fibroblast (see Fig. 3, B and C). Reduction in the early peak suggests a small reduction in the ability of the fibroblast to act as a current sink during the upstroke of the AP. Xie et al. (39) showed that this early component of the gap junction current may play an important role in promoting cardiac alternans; however, based on the slow time constants of inactivation we do not expect different connexin types to alter the cycle length of onset of alternans. Using a cell-specific model of a dynamic-clamp experiment revealed that M-F coupling results in significant changes in the underlying currents especially for IKs (see Fig. 5 E). These results are similar to those found previously by MacCannell et al. (27) and Nayak et al. (48).

Because GJ channels are a major contributor to axial resistance along with cytoplasmic resistance and play a key role in cardiac conduction (50), we explored whether the Cx type of M-F GJ channels would play a role in impulse propagation during cardiac fibrosis. Earlier work by Henriquez et al. (43) demonstrated in a cardiomyocyte fiber model that during poor coupling the time- and transjunctional voltage-dependent gating of GJ channels resulted in increases in junctional resistance that resulted in increased conduction delays compared to a static GJ model. However, in our tissue-level simulations GJ channel gating does not significantly alter activation time (see Fig. 6 B), repolarization time (see Fig. 6 C), and conduction velocity (see Fig. 7) in a tissue sheet model of cardiac fibrosis. This difference is likely due to the existence of alternative conduction pathways in the 2D tissue structure that help maintain the conduction velocity, which is not present in the one-dimensional fiber model.

To date, it is unresolved whether functional M-F coupling occurs in vivo. However, gap-junction coupling between myocytes and fibroblasts has been well documented in cell culture studies (4, 11, 12, 22). Thus, our results may also provide insight into the complex interactions between myocytes and fibroblasts that occur in such co-culture studies.

Conclusions

The time- and Vj-dependent gating of GJ channels results in inactivation of junctional conductance in response to large Vj steps. Despite each Cx type having unique features in their time- and Vj-dependent profiles, the kinetics of inactivation are very slow. During M-F coupling, the transjunctional voltage reaches a minimum at ∼−100 mV during the upstroke of the AP. However, this large transjunctional voltage is short-lived; throughout the remainder of the AP the transjunctional voltage is <±30 mV. In this transjunctional voltage range the time constant of GJ inactivation is much longer than the APD and therefore the GJ channel conductance remains close to its static value. The large transjunctional voltage during the early upstroke of the AP results in a reduction in the early peak of the junctional current compared to a static GJ model. This reduction suggests that fibroblasts are acting as less of a current sink when M-F coupling is mediated by a dynamic GJ channel model. However, this does not result in significant modifications in the conduction velocity. Thus, we determined that GJ channel gating does not significantly alter underlying M-F coupling nor does it significantly alter impulse propagation and conduction velocity during cardiac fibrosis.

Limitations

The Cx models developed are largely based on a single set of experimental data expressed in transfected HeLa cells. Cx expressed in cardiomyocytes and fibroblasts may have different properties even though relative differences in the gating properties of the GJ channels may be similar. Moreover, GJ channels exhibit both electrical and chemical gating properties and allow for metabolic communication between neighboring cells (13). Our dynamic clamp and computational modeling studies focus on the effects of electrical gating properties of GJ channels on M-F coupling without taking into account the effects of chemical gating and metabolic communication of the GJ channels. However, this strategy is also beneficial in that we were able to isolate the contribution of the effects due to electrical interactions from other forms of M-F interactions. Finally, because the effects of M-F coupling on cardiomyocyte properties depends on the fibroblast electrophysiological properties (48) (which was not significantly explored in this study due to the lack of available experimental data), further understanding of the electrophysiological properties of fibroblasts could alter the contributions of GJ gating during M-F coupling.

Author Contributions

D.J.C. conceived the project; T.R.B. designed, performed, and analyzed experiments and simulations; T.K.-M. contributed analysis tools; and T.R.B., T.K.-M., and D.J.C. wrote the article.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant No. T32GM07739 to the Weill Cornell/Rockefeller/Sloan-Kettering Tri-Institutional MD/PhD Program; grant No. R01EB016407 to D.J.C.; and grant No. F31HL124939 to T.R.B.), and by the UNCF/Merck Graduate Science Research Dissertation Fellowship (to T.R.B.).

Editor: Dennis Bray.

References

- 1.Nag A.C. Study of non-muscle cells of the adult mammalian heart: a fine structural analysis and distribution. Cytobios. 1980;28:41–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banerjee I., Fuseler J.W., Baudino T.A. Determination of cell types and numbers during cardiac development in the neonatal and adult rat and mouse. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007;293:H1883–H1891. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00514.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Jong S., van Veen T.A.B., de Bakker J.M.T. Fibrosis and cardiac arrhythmias. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2011;57:630–638. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e318207a35f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baudino T.A., McFadden A., Borg T.K. Cell patterning: interaction of cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts in three-dimensional culture. Microsc. Microanal. 2008;14:117–125. doi: 10.1017/S1431927608080021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vasquez C., Mohandas P., Morley G.E. Enhanced fibroblast-myocyte interactions in response to cardiac injury. Circ. Res. 2010;107:1011–1020. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.227421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Camelliti P., Green C.R., Kohl P. Fibroblast network in rabbit sinoatrial node: structural and functional identification of homogeneous and heterogeneous cell coupling. Circ. Res. 2004;94:828–835. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000122382.19400.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baum J.R., Long B., Duffy H.S. Myofibroblasts cause heterogeneous Cx43 reduction and are unlikely to be coupled to myocytes in the healing canine infarct. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2012;302:H790–H800. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00498.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kohl P., Gourdie R.G. Fibroblast-myocyte electrotonic coupling: does it occur in native cardiac tissue? J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2014;70:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quinn T.A., Camelliti P., Poggioli T. Cell-specific expression of voltage-sensitive protein confirms cardiac myocyte to non-myocyte electrotonic coupling in healed murine infarct border tissue. Circulation. 2014;130:A11749. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguyen T.P., Xie Y., Weiss J.N. Arrhythmogenic consequences of myofibroblast-myocyte coupling. Cardiovasc. Res. 2012;93:242–251. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miragoli M., Gaudesius G., Rohr S. Electrotonic modulation of cardiac impulse conduction by myofibroblasts. Circ. Res. 2006;98:801–810. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000214537.44195.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miragoli M., Salvarani N., Rohr S. Myofibroblasts induce ectopic activity in cardiac tissue. Circ. Res. 2007;101:755–758. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.160549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris A., Locke D. Humana Press; New York: 2009. Connexins. A Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giovannone S., Remo B.F., Fishman G.I. Channeling diversity: gap junction expression in the heart. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:1159–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.11.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zipes D.P., Jalife J. Elsevier Health Sciences; Philadelphia, PA: 2013. Cardiac Electrophysiology: from Cell to Bedside. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desplantez T., Dupont E., Weingart R. Gap junction channels and cardiac impulse propagation. J. Membr. Biol. 2007;218:13–28. doi: 10.1007/s00232-007-9046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dupont E., Matsushita T., Severs N.J. Altered connexin expression in human congestive heart failure. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2001;33:359–371. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamada K.A., Rogers J.G., Saffitz J. Up-regulation of connexin45 in heart failure. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2003;14:1205–1212. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.03276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y., Kanter E.M., Yamada K.A. Connexin43 expression levels influence intercellular coupling and cell proliferation of native murine cardiac fibroblasts. Cell Commun. Adhes. 2008;15:289–303. doi: 10.1080/15419060802198736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Camelliti P., Devlin G.P., Green C.R. Spatially and temporally distinct expression of fibroblast connexins after sheep ventricular infarction. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004;62:415–425. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rook M.B., Jongsma H.J., de Jonge B. Single channel currents of homo- and heterologous gap junctions between cardiac fibroblasts and myocytes. Pflugers Arch. 1989;414:95–98. doi: 10.1007/BF00585633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McSpadden L.C., Kirkton R.D., Bursac N. Electrotonic loading of anisotropic cardiac monolayers by unexcitable cells depends on connexin type and expression level. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C339–C351. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00024.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Desplantez T., Grikscheit K., Dupont E. Relating specific connexin co-expression ratio to connexon composition and gap junction function. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2015;89(Pt B):195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown T.R., Krogh-Madsen T., Christini D.J. Computational approaches to understanding the role of fibroblast-myocyte interactions in cardiac arrhythmogenesis. BioMed Res. Int. 2015;2015:465714. doi: 10.1155/2015/465714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilders R. Dynamic clamp: a powerful tool in cardiac electrophysiology. J. Physiol. 2006;576:349–359. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.115840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bryant S.M., Shipsey S.J., Hart G. Regional differences in electrical and mechanical properties of myocytes from guinea-pig hearts with mild left ventricular hypertrophy. Cardiovasc. Res. 1997;35:315–323. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacCannell K.A., Bazzazi H., Giles W.R. A mathematical model of electrotonic interactions between ventricular myocytes and fibroblasts. Biophys. J. 2007;92:4121–4132. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.101410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahrens-Nicklas R.C., Christini D.J. Anthropomorphizing the mouse cardiac action potential via a novel dynamic clamp method. Biophys. J. 2009;97:2684–2692. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bot C.T., Kherlopian A.R., Krogh-Madsen T. Rapid genetic algorithm optimization of a mouse computational model: benefits for anthropomorphization of neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes. Front. Physiol. 2012;3:421. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Livshitz L.M., Rudy Y. Regulation of Ca2+ and electrical alternans in cardiac myocytes: role of CAMKII and repolarizing currents. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007;292:H2854–H2866. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01347.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Livshitz L., Rudy Y. Uniqueness and stability of action potential models during rest, pacing, and conduction using problem-solving environment. Biophys. J. 2009;97:1265–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.05.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Groenendaal W., Ortega F.A., Christini D.J. Cell-specific cardiac electrophysiology models. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2015;11:e1004242. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vogel R., Weingart R. Mathematical model of vertebrate gap junctions derived from electrical measurements on homotypic and heterotypic channels. J. Physiol. 1998;510:177–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.177bz.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trenor B., Cardona K., Saiz J. Simulation and mechanistic investigation of the arrhythmogenic role of the late sodium current in human heart failure. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grandi E., Pasqualini F.S., Bers D.M. A novel computational model of the human ventricular action potential and Ca transient. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2010;48:112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xie Y., Garfinkel A., Qu Z. Effects of fibroblast-myocyte coupling on cardiac conduction and vulnerability to reentry: a computational study. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:1641–1649. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keener J.P. The effects of gap junctions on propagation in myocardium: a modified cable theory. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1990;591:257–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb15094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hubbard M.L., Ying W., Henriquez C.S. Effect of gap junction distribution on impulse propagation in a monolayer of myocytes: a model study. Europace. 2007;9(Suppl 6):vi20–vi28. doi: 10.1093/europace/eum203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie Y., Garfinkel A., Qu Z. Cardiac alternans induced by fibroblast-myocyte coupling: mechanistic insights from computational models. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2009;297:H775–H784. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00341.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rook M.B., van Ginneken A.C.G., Jongsma H.J. Differences in gap junction channels between cardiac myocytes, fibroblasts, and heterologous pairs. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;263:C959–C977. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.263.5.C959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Desplantez T., Halliday D., Weingart R. Cardiac connexins Cx43 and Cx45: formation of diverse gap junction channels with diverse electrical properties. Pflugers Arch. 2004;448:363–375. doi: 10.1007/s00424-004-1250-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vogel R., Weingart R. The electrophysiology of gap junctions and gap junction channels and their mathematical modelling. Biol. Cell. 2002;94:501–510. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(02)00022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Henriquez A.P., Vogel R., Cascio W.E. Influence of dynamic gap junction resistance on impulse propagation in ventricular myocardium: a computer simulation study. Biophys. J. 2001;81:2112–2121. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75859-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elenes S., Martinez A.D., Moreno A.P. Heterotypic docking of Cx43 and Cx45 connexins blocks fast voltage gating of Cx43. Biophys. J. 2001;81:1406–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75796-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bukauskas F.F., Angele A.B., Bennett M.V.L. Coupling asymmetry of heterotypic connexin 45/ connexin 43-EGFP gap junctions: properties of fast and slow gating mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:7113–7118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032062099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Valiunas V. Biophysical properties of connexin-45 gap junction hemichannels studied in vertebrate cells. J. Gen. Physiol. 2002;119:147–164. doi: 10.1085/jgp.119.2.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.González D., Gómez-Hernández J.M., Barrio L.C. Molecular basis of voltage dependence of connexin channels: an integrative appraisal. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2007;94:66–106. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nayak A.R., Shajahan T.K., Pandit R. Spiral-wave dynamics in a mathematical model of human ventricular tissue with myocytes and fibroblasts. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72950. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krogh-Madsen T., Christini D.J. Action potential duration dispersion and alternans in simulated heterogeneous cardiac tissue with a structural barrier. Biophys. J. 2007;92:1138–1149. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.090845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.King J.H., Huang C.L.H., Fraser J.A. Determinants of myocardial conduction velocity: implications for arrhythmogenesis. Front. Physiol. 2013;4:154. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]