Abstract

Background

Positive symptom association probability (SAP) with physiologic esophageal acid exposure time (AET) on pH-impedance monitoring defines reflux hypersensitivity (RH), a correlate of acid sensitivity on pH monitoring. We evaluated prevalence, clinical characteristics, and symptomatic outcomes of RH in a prospective observational cohort with reflux symptoms undergoing pH-impedance monitoring.

Methods

RH was diagnosed when SAP was positive with pH- and/or impedance-detected reflux events with physiologic AET. Symptom burden was assessed using dominant symptom intensity (DSI, product of symptom severity and frequency on 5-point Likert scales) and global symptom severity (GSS, global esophageal symptoms on 100-mm visual analog scales) by questionnaire, both at baseline and on prospective follow-up. Clinical characteristics and predictors of symptomatic improvement were assessed with univariate and multivariate analyses.

Results

77 patients (29%) met criteria for RH, of which 53 patients (53.7±1.8 yr, 66% F) were contacted after 3.3±0.2 yrs for follow-up. RH was detected on pH-impedance testing both on and off antisecretory therapy; pH alone missed 51% of RH. 57% reported ≥50% GSS improvement. 16 patients undergoing anti-reflux surgery (ARS) reported better symptom improvement compared to 37 treated medically (GSS change: p=0.005; DSI change: p=0.04). Hiatus hernia (p=0.03) and surgical management (p≤0.04) predicted symptom improvement on univariate analysis, while acid sensitivity was a negative predictor for outcome on both univariate (p=0.02) and multivariate analyses (p≤0.04).

Conclusions

RH is a mechanism for persistent reflux symptoms in almost one-third of patients undergoing pH-impedance testing. While acid sensitivity predicts suboptimal symptom improvement, anti-reflux therapy may improve RH in select settings.

Keywords: gastroesophageal reflux disease, pH-impedance monitoring, reflux hypersensitivity

INTRODUCTION

Ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring is often performed when reflux symptoms persist despite an empiric trial of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, in the absence of alternate explanations for symptoms.1 While abnormal esophageal acid exposure time (AET) identifies pathologic esophageal acid exposure, a proportion of patients will have physiologic AET but correlation of their symptoms with reflux events on symptom-reflux association testing. ‘Acid sensitivity’ and ‘hypersensitive esophagus’ are terms that have been used to describe this cohort of patients;2, 3 earlier definitions have included these patients with non-erosive gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)4 or even functional heartburn.5 A lowered threshold for sensory perception has been proposed as a mechanism for this phenomenon.2

As technology has evolved towards the detection of all reflux events irrespective of pH with combined pH-impedance monitoring, the sensitivity for detection of symptom-reflux association has increased over traditional pH monitoring.6-8 Diagnostic criteria have also evolved, with modern definitions of functional heartburn requiring physiologic reflux monitoring parameters and the absence of reflux triggering of heartburn symptoms.4 Using pH-impedance monitoring, some patients with functional heartburn may demonstrate weakly acidic reflux events triggering symptoms,9, 10 shifting proportions of functional heartburn to a reflux-triggered symptom category. This category has been designated as reflux hypersensitivity (RH), in contrast to acid sensitivity, which is triggered by acid reflux events alone; this is now considered part of the functional esophageal disorder spectrum. However, clinical characteristics and symptomatic outcomes of patients with RH have not yet been well-characterized.

In this study, we evaluated the prevalence, symptom burden, mode of therapy, and treatment outcome of RH in a prospectively followed cohort of patients with reflux symptoms undergoing pH-impedance testing. We further evaluated the value of pH-impedance monitoring off or on PPI therapy in identification of RH in this symptomatic cohort.

METHODS

All adults (≥18 years of age) with persisting GERD symptoms despite antisecretory therapy referred for pH-impedance testing to the motility center at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, from January 2005 through August 2010, were eligible for inclusion; findings predicting symptomatic benefit gleaned from this cohort have been previously published11, 12. For the present study, subjects were selected if they met criteria for RH by having positive acid and/or impedance symptom-reflux association in the setting of a physiologic AET on pH-impedance testing; therefore, patients with acidic, weakly-acidic as well as non-acidic reflux events were included. Exclusion criteria included inadequate studies (poor data quality precluding analysis), incomplete studies (less than 14 hours of recording time), major esophageal motor disorders, or a prior history of fundoplication or other esophageal surgery. This study protocol was approved by the Human Research Protection Office (institutional review board) at Washington University in St. Louis.

Demographics and Symptom Assessment

Basic demographic data (age, gender) and dominant symptoms (typical, atypical) were extracted from the clinical record. Endoscopic, manometric, and radiologic studies were reviewed; the morphology of the esophagogastric junction (EGJ) was determined.13 All patients completed a symptom survey prior to pH-impedance testing to rate their dominant and secondary symptom frequency and severity on 5-point Likert scales generated a priori for esophageal testing at our center and used in previous publications.12, 14, 15 On these scales, patients rate symptom frequency from 0 (no symptoms) to 4 (multiple daily episodes) and symptom severity from 0 (no symptoms) to 4 (very severe symptoms). Symptom intensity is then calculated as the product of the frequency and severity of the dominant symptom being evaluated (dominant symptom intensity, DSI), for a final score ranging from 0 to 16. Typical symptoms included heartburn and regurgitation, and atypical symptoms included chest pain, cough, and laryngeal symptoms. Finally, patients rate their global symptom severity (GSS) over the previous two weeks on a 100-mm visual analog scale12, 14, 15.

Referring physicians guided subsequent management; treatment decisions were not influenced by this study. Potential subjects for this study were prospectively contacted per study protocol to evaluate management approaches (medical versus surgical therapy) and symptom burden outcomes. The pre-procedure symptom survey was re-administered, and changes in DSI and GSS scores were calculated.

pH-Impedance Testing

pH-impedance monitoring at our center is ‘open-access;’ referring physicians dictate whether testing is performed on or off antisecretory therapy. When testing is performed off therapy, patients are instructed to stop their PPI medications 7 days prior to the study, and histamine-2 receptor antagonists, prokinetic medications, and antacids 3 days prior to the study. After an overnight fast, an experienced nurse positions the pH-impedance catheter (Sandhill Scientific, Highlands Ranch, CO) such that the distal esophageal pH sensor is 5 cm proximal to the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), measured using high resolution esophageal manometry (HRM). Throughout the 24 hours of data acquisition, patients record their meals and activities, and log their symptom events. The uploaded data is then analyzed with dedicated software (Bioview Analysis; Sandhill Scientific, Highlands Ranch, CO), which calculates the exposure times and symptom-reflux association parameters. Each pH-impedance study was further scrutinized manually by two reviewers (AP, CPG) to ensure the automated capture of reflux events was accurate; any discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved by discussion.

AET was calculated as the percentage of time the pH was below 4 at the distal esophageal pH sensor. An AET≥4.0% was designated as abnormal per our institutional threshold.12, 16 Symptoms were considered associated with reflux events if they occurred within 2 minutes following the reflux event. Symptom-reflux association was assessed using symptom association probability (SAP), calculated with the Ghillebert probability estimate (GPE) using previously described methods.17, 18 The SAP was designated as positive if the likelihood of a chance association between the symptom and reflux events was <5%, corresponding to p<0.05. Our group has previously shown that GPE has strong concordance with SAP calculated using the Weusten method.19, 20 The SAP was first calculated for pH-detected reflux events, then re-calculated for all impedance-detected reflux events. Patients had to have either positive acid or impedance SAP, or both, to be included in this study.

Definitions

For the purpose of this study, the following definitions were used:

Reflux hypersensitivity (RH): Physiologic AET, and positive SAP with either pH- or impedance-detected reflux events, or both

Acid sensitivity: Physiologic AET, and positive SAP with pH-detected reflux events

Functional symptoms: Physiologic AET, and negative SAP

Reflux evidence: Abnormal AET, positive or negative SAP

Data Analysis

Data are reported as the mean ± standard error of the mean. Categorical data were compared using the χ-squared test, and continuous data were compared using the 2-tailed Student's t-test or ANOVA, as appropriate. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to identify findings that predicted an improved symptomatic outcome, measured as both linear DSI and GSS change and dichotomous ≥50% DSI and GSS improvement. Linear regression models were created to determine predictors of a successful symptomatic outcome, and included demographic, clinical, and impedance parameters. In all cases, p<0.05 was required for statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics V.22.0 (Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

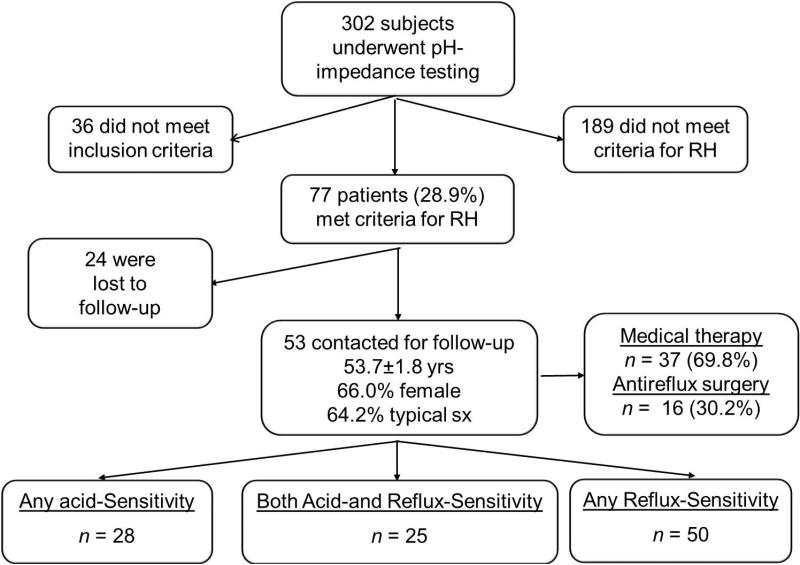

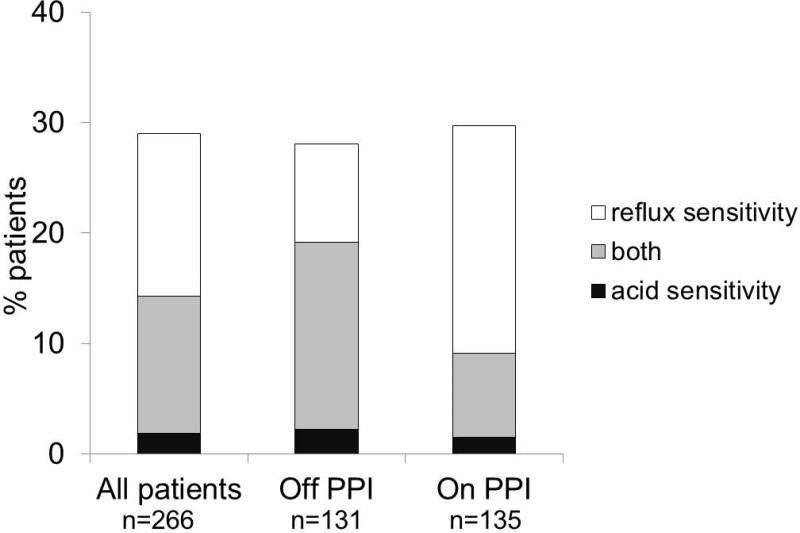

Over the 5-year study period, 302 subjects underwent ambulatory pH-impedance testing for GERD symptoms. 36 patients did not meet inclusion criteria (7 had inadequate or incomplete studies, 26 had undergone fundoplication or other esophageal surgery, and 3 had evidence of major esophageal motility disorders). Of the remaining 266 patients (52.7±0.8 yr), 77 patients (28.9%) met criteria for RH (Figure 1). Similar proportions meeting criteria for RH were found when tested on PPI (39/131, 29.8%) and off PPI (38/135, 28.1%, Figure 2). Of these 77 patients, 5 were purely acid-sensitive (positive acid SAP but negative impedance SAP), 39 were only sensitive to impedance-detected reflux events (negative acid SAP but positive impedance SAP), and 33 were sensitive to both acid- and impedance-detected reflux events (positive acid and impedance SAP). Pure acid sensitivity was infrequent (2.2% off PPI, 1.5% on PPI); most patients with acid sensitivity also had positive SAP with impedance-detected reflux events (91.7% overall, 88.5% off PPI, 83.3% on PPI). However, 50.6% of RH would have been missed with pH monitoring alone, with a 102.6% gain in diagnosis of RH when pH-impedance analysis was used to identify RH, over traditional pH analysis alone (Figure 2). As expected, this gain was most profound when pH-impedance monitoring was performed on PPI (225.0% gain) compared to testing off PPI (46.2% gain, p=0.002; Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Schematic flow diagram of study design. Almost a third of the cohort with reflux hypersensitivity (RH) underwent antireflux surgery during follow-up, while the remainder were managed medically. There was overlap between acid sensitivity and RH.

Figure 2.

Proportions of patients with acid-sensitivity and reflux hypersensitivity (RH) in the study cohorts. 91.7% of patients with RH also had acid sensitivity. There was 102.6% gain in RH diagnosis over acid sensitivity alone. Proportions with pure RH were higher when pH impedance testing was performed on PPI (p=0.002 compared to off PPI), indicating overlap between GERD and RH in these patients.

53 patients (53.7±1.8 yrs, 66.0% F, 64.2% with typical symptoms) could be successfully contacted for administration of a follow-up questionnaire. Of these 53 patients with RH, 50 demonstrated sensitivity to impedance-detected reflux events and 28 were acid-sensitive, while 25 demonstrated sensitivity to both acid- and impedance-detected reflux events. Over 3.3±0.2 yr follow-up, 37 (69.8%) were managed medically, while 16 (30.2%) underwent ARS (Figure 1). The medical and surgical groups did not differ with respect to age, gender, race, typical symptom presentation, baseline DSI or GSS, PPI status on testing, presence of a hiatal hernia, duration of follow-up, or linear change in DSI or GSS (p≥0.07 for all comparisons; Table 1), although the surgical group had lower LES basal pressures (p=0.04). 29 patients were studied off PPI therapy, and 24 on PPI therapy. Although the “off PPI” group was younger (p=0.012), these cohorts were similar in gender, ethnicity, baseline symptom burden, typical symptom presentation, LES basal pressure, proportions managed surgically, duration of follow-up, and linear and dichotomous symptom improvement (p≥0.1 for all comparisons).

Table 1.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics of Reflux Hypersensitivity (RH) Patients

| All RH patients n=53 | Medical Therapy n=37 | Antireflux Surgery n=16 | P values*** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (yr) | 53.7±1.8 | 52.8±2.3 | 55.7±2.6 | 0.46 |

| Sex (F) | 35 (66%) | 23 (62%) | 12 (75%) | 0.37 |

| Race (Caucasian) | 47 (89%) | 34 (92%) | 13 (81%) | 0.26 |

| Typical symptoms* | 34 (64%) | 24 (65%) | 10 (63%) | 0.87 |

| Duration of follow-up (mo) | 39.1±2.8 | 38.1±3.3 | 41.6±5.4 | 0.57 |

| Study on PPI | 24 (45%) | 17 (46%) | 7 (44%) | 0.88 |

| Hiatal hernia | 19 (36%) | 12 (32%) | 7 (44%) | 0.43 |

| LES Pressure | 11.5±1.2 | 13.1±1.4 | 8.1±1.8 | 0.04 |

| Symptom Intensity | ||||

| Baseline | 8.7±0.8 | 8.4±0.9 | 9.4±1.5 | 0.54 |

| Change** | 4.9±0.9 | 3.8±1.1 | 7.4±1.4 | 0.07 |

| ≥50% Improvement | 32 (65%) | 19 (56%) | 13 (87%) | 0.04 |

| GSS | ||||

| Baseline | 62.3±3.9 | 62.9±4.2 | 60.5±9.1 | 0.79 |

| Change** | 34.9±4.9 | 30.2±5.3 | 47.4±10.4 | 0.12 |

| ≥50% Improvement | 27 (57%) | 16 (46%) | 11 (92%) | 0.005 |

heartburn, acid regurgitation

between baseline and follow-up assessments

chi-square test for categorical variables and independent-samples t test for continuous variables

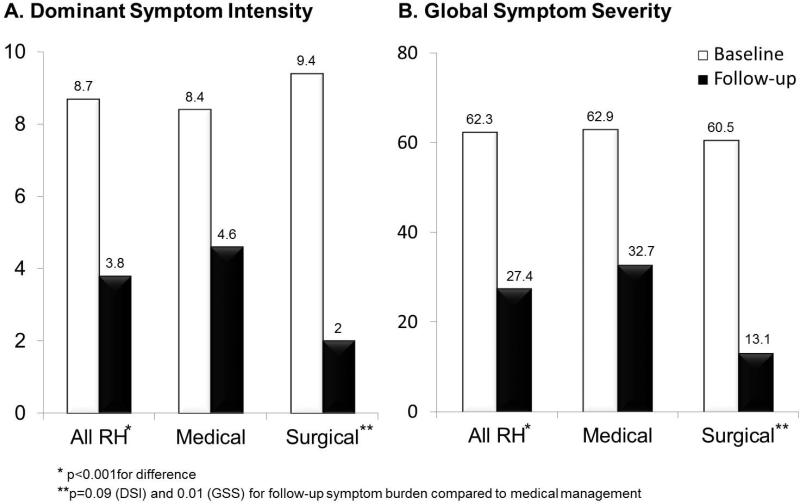

Overall, 57.0% of the total cohort reported ≥50% GSS improvement, with significant mean reduction in both DSI and GSS with therapy (p<0.001; Figure 3). Medically managed patients demonstrated a dichotomous response; those with ≥50% GSS improvement reported a mean GSS improvement of 86.3±3.9% over basal GSS scores, while those with <50% improvement reported global symptom worsening (mean GSS change of −7.4±18.0%, p<0.001). Higher proportions of surgically managed patients had ≥50% improvement in symptom burden metrics (DSI: 86.7% vs 55.8% with medical management, p=0.04; GSS 91.7% vs 45.7%, p=0.005). Surgically managed patients reported lower follow-up linear DSI and GSS scores compared to medically treated patients (p=0.01 and p=0.09, respectively; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Baseline and follow-up symptom burden (Panel A: DSI, dominant symptom intensity; Panel B: GSS, global symptom severity) in the study cohort with reflux hypersensitivity (RH), segregated by medical vs. surgical management. Symptom burden significantly improved on follow up (p<0.001). Although baseline symptom burden metrics were similar among medical and surgical groups, there was lesser residual symptom burden among surgical patients compared to medical patients (p=0.09 and p=0.01 for DSI and GSS, respectively).

There was no statistical difference in outcome between typical and atypical symptom cohorts, with either medical or surgical management (Table 1), although numbers were too small to make meaningful comparisons. On analysis of outcome by dominant symptom presentation, there was no difference in proportions with ≥50% DSI improvement between heartburn (71.4%), regurgitation (64.7%), chest pain (50.0%) or cough (66.7%, p=0.9 across groups). Only 13 of 53 patients with RH had numbers of reflux events higher than conventional thresholds off (>73) and on (>48) PPI therapy, and their outcome was similar to those who had low numbers of reflux events (57.0% vs. 58.0% with ≥50% GSS improvement respectively, p=0.9).

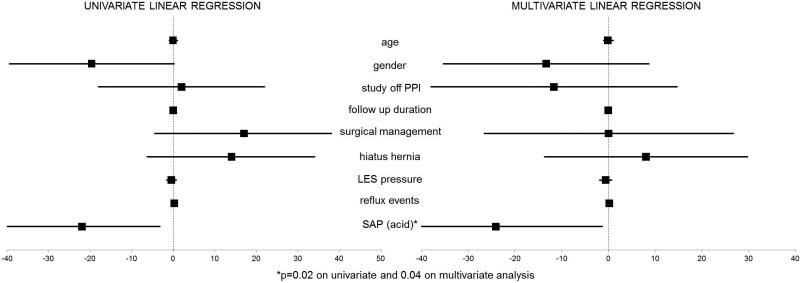

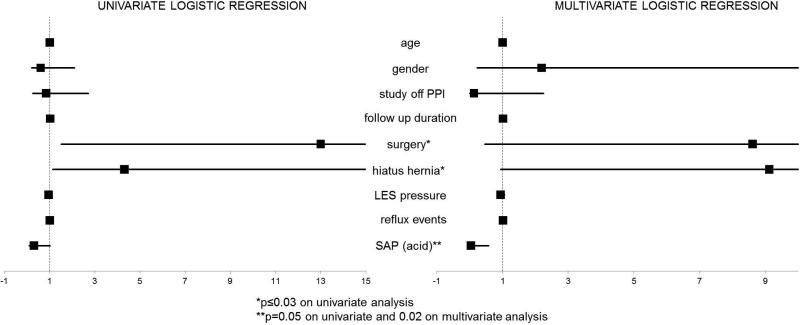

On univariate analysis assessing predictors of symptom improvement, positive acid SAP predicted suboptimal linear GSS improvement (p=0.022), but did not predict linear DSI change. Other clinical and physiologic parameters tested (demographics, typical symptom presentation, duration of follow-up, PPI status on testing, presence of hiatus hernia, LES basal pressures, ARS, total reflux events, and positive impedance SAP) did not predict linear GSS or DSI change in this cohort (p≥0.05 for all parameters; Figure 4). On univariate analysis, hiatus hernia and surgical management predicted dichotomous GSS improvement (p=0.03 and p=0.02, respectively, Figure 3); surgical management strongly trended towards predicting dichotomous DSI improvement (p=0.050). However, demographics, dominant presenting symptom, PPI treatment status, and LES basal pressures did not predict dichotomous improvement in either symptom burden metric (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4.

Univariate and multivariate linear regression analysis evaluating predictors of linear change in global symptom severity (GSS) over follow up. Symptom correlation with acid reflux events was a negative predictor of linear symptom improvement in both analyses. None of the other variables assessed predicted linear GSS improvement.

Figure 5.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis evaluating predictors of ≥50% improvement in global symptom severity (GSS). Presence of a hiatus hernia and surgical management were univariate predictors of ≥50% GSS improvement, but did not retain significance in multivariate analysis. Symptom correlation with acid reflux events was a negative predictor of ≥50% GSS improvement, achieving near statistical significance on univariate analysis (p=0.05), and retaining significance on multivariate analysis (p=0.02).

A multivariate analysis model was generated that included demographics, typical symptom presentation, total numbers of reflux events, EGJ metrics, PPI status on testing, acid SAP, surgical management, and duration of follow-up. Only ARS (positive predictor of dichotomous DSI improvement; p=0.03) and positive acid SAP (negative predictor of linear and ≥50% GSS improvement; p=0.04 and p=0.02, respectively) proved significant (Figures 4 and 5).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we report that RH represents a mechanism for reflux symptoms in almost one-third of patients with persisting reflux symptoms despite PPI therapy undergoing pH-impedance testing at a single tertiary medical center, with similar proportions detected when tested on or off PPI therapy. We demonstrate that using pH-impedance testing augments detection of RH, and that RH can overlap with true reflux disease, persisting despite PPI therapy and contributing to the symptom burden. Over one-half of patients report ≥50% symptomatic improvement with antireflux therapy, including surgical management, especially for those with low LES basal pressures and/or hiatus hernia. However, acid sensitivity represents a negative predictor for symptom improvement with antireflux therapy in RH, suggesting that testing off PPI may help better define symptom outcomes.

Recognition of RH as a distinct entity is important for several reasons. In the past, some patients fulfilling RH criteria (i.e. acid sensitivity) were lumped together with non-erosive reflux disease (NERD),4 while others would have been designated functional.5 It has been established that NERD with abnormal AET has symptomatic outcome similar to erosive GERD with PPI therapy, both in terms of partial response and complete symptom response.21 Studies evaluating esophageal mucosal integrity, using baseline mucosal impedance,22 transepithelial electrical resistance,23 and histopathologic assessment including dilated intracellular spaces parameters,24, 25 also establish differences between cohorts with and without abnormal reflux. Therefore, extracting subsets without pathologic AET from NERD cohorts could facilitate optimal management of NERD. Acid sensitivity, in particular, is reported to have worse outcomes compared to NERD or GERD.26 We report a dichotomous response in RH, as those with sensitivity to acid reflux events had worse symptomatic outcomes compared to those with sensitivity to impedance-detected reflux events, further supporting this concept. In recognition of all these facts, RH is now considered a functional esophageal disorder, distinct from functional heartburn.

Our data further establishes the value of pH-impedance monitoring over that of traditional pH monitoring alone in evaluating persisting esophageal symptoms. We have previously reported gains in detection of symptom association with reflux events with pH-impedance monitoring.12, 27 In the present study, the gain in diagnosis of RH doubled when impedance-detected reflux events were utilized in calculating SAP. Without impedance, these additional cases would have been designated as functional symptoms rather than RH, potentially denying these patients the option for antireflux therapy. Savarino et al have reported a similar shift in diagnosis from functional heartburn to hypersensitive esophagus (identical to the prevailing definition of RH) with the use of pH-impedance monitoring.9 Applying combined pH-impedance testing results to Rome III criteria in differentiating FH from NERD, they report a 10% increase in identification of RH with combined pH-impedance testing; overall, 38% (83/219) of their cohort had hypersensitive esophagus or RH on pH-impedance testing compared to 28% (61/219) with traditional pH monitoring. A prior multicenter study also demonstrated that 37% of patients who underwent combined pH-impedance monitoring on at least twice-daily PPI therapy had positive symptom index with impedance-detected reflux episodes. However, although proportions are similar, this study used symptom index rather than SAP, and used a 5-minute window for symptom reflux association rather than the 2-minute standard for SAP10. Nevertheless, gains in diagnosis of RH with impedance from both these studies are similar to our results, and establish the value of pH-impedance monitoring in avoiding overdiagnosis of functional esophageal symptoms. The overlap between true GERD (or NERD) and RH is further demonstrated in the population studied on PPI therapy. Overall proportions of RH were similar to that seen on studies off PPI, but sensitivity to impedance-detected reflux events dominated when testing was performed on PPI, suggesting that RH and GERD can coexist, and that pH-impedance testing on PPI in patients with proven GERD may help identify this subset of patients.

Symptom-reflux association forms the basis for the diagnosis of RH. While the value of symptom-reflux association is limited by the accuracy of symptom reporting despite use of pH-impedance testing,28 we have previously shown that positive impedance SAP predicts global symptom improvement,12 and we suggest that SAP can be a useful parameter when positive. Perhaps because impedance-detected reflux events are shorter in duration than acid-detected reflux events due to faster refluxate clearance compared to resolution of mucosal acidification following reflux events, impedance SAP could be more specific than acid SAP.10, 29 Further, if reflux symptom generation involves mechanical stretch and not just chemical stimulation, pH testing alone could miss reflux events that do not stimulate distal esophageal mechanoreceptors; indeed, there is evidence to suggest the significance of increased sensitivity to mechanical (balloon) distension of the distal esophagus in hypersensitive esophagus, despite the fact that perceptive esophageal symptoms are more frequent with higher proximal extent of the refluxate.30

Our findings establish the value of antireflux therapy in the management of RH, and demonstrate that medical management is successful when patients respond to therapy. In contrast, many patients with a poor response reported symptom worsening over follow-up. While we cannot ascertain if patients managed medically were given sensory neuromodulators to complement antireflux therapy, we established that all patients were treated with acid suppression. The value of antireflux therapy is further demonstrated by the high proportions with symptom improvement with ARS, especially in the presence of low LES pressures and a hiatus hernia. Acid sensitivity, in contrast, is associated with poor symptom improvement with antireflux therapy, adding support to the notion that triggering of esophageal symptoms with physiologic acid reflux may represent a functional process.31 Finally, we report a limited role for antireflux surgery in well documented RH, especially in the setting of structural disruption at the EGJ (e.g. hiatus hernia); a trial of neuromodulation may be appropriate prior to taking this step, but our study was not designed to evaluate the role of neuromodulators. Others have reported value for antireflux surgery in esophageal acid sensitivity, but many undergoing antireflux surgery in this study had evidence of esophagitis on endoscopy32.

Our study design includes several limitations that temper the strength of our conclusions. Although data was gathered prospectively, patients were identified retrospectively; a minority could not be successfully reached for follow-up assessment. Further, only a proportion of patients underwent pH-impedance testing during the time period of the study, while other patients continued to be evaluated by pH-testing, both catheter based and wireless; this limited the sample size of our study. Heterogeneity related to antisecretory treatment status (off PPI therapy, submaximal PPI therapy, maximal PPI therapy) prior to pH-impedance testing could have influence our baseline symptom burden measures. We could not accurately evaluate adjunctive medical therapy, such as neuromodulators, which potentially could have impacted symptomatic outcomes; moreover, non-reflux symptom modulators such as affective disorders and functional syndromes may have influenced symptoms. Inclusion of a comparator group with only traditional pH testing to assess for acid sensitivity could have shown differences between traditional pH and combined pH-impedance testing. Finally, management was not protocolized in this study and instead left to referring physicians. Despite these limitations, we feel that our findings describe RH as a unique entity that needs to be distinguished from functional esophageal symptoms.

In summary, RH is diagnosed in nearly one-third of patients undergoing pH-impedance testing at a tertiary care center, with a shift from functional diagnoses to RH when combined pH-impedance monitoring is used rather than traditional pH monitoring. While over half of patients improve with antireflux therapy, surgical management may provide even more profound benefit in the setting of a disrupted EGJ barrier. Interestingly, a positive association between symptoms and acid-detected reflux events is associated with poorer symptomatic outcomes. Further prospective characterization of RH in comparison to GERD with abnormal AET will benefit understanding of this entity.

Key Points.

Reflux hypersensitivity (RH) refers to normal esophageal acid exposure but positive symptom association with all reflux events. Combined pH-impedance testing can detect symptom-reflux correlation beyond acid sensitivity seen on ambulatory pH monitoring.

We evaluated the prevalence, symptom burden and outcome from antireflux therapy of RH in a cohort of prospectively followed patients undergoing pH-impedance testing. Almost a third of patients undergoing pH impedance testing for persistent reflux symptoms have RH. Using pH impedance, there is a shift in diagnosis from no reflux evidence towards RH, when compared to pH monitoring alone, indicating perception of reflux events irrespective of pH in some patients.

RH defined with impedance-detected reflux events improves more profoundly than acid sensitivity with antireflux therapy; antireflux surgery can be an option for select RH patients with structural disruption at the esophagogastric junction

Acknowledgments

This study was partially funded through NIH/NIDDK (T32 DK007130 –AP; NIH K23DK84413-4 - GSS), and through the Washington University Department of Medicine Mentors in Medicine (MIM) and Clinical Science Training and Research (CSTAR) programs.

Author roles: AP: study design, data collection and analysis, manuscript preparation and review; GSS: study design, data analysis, critical review of manuscript; CPG: study concept and design, data analysis, manuscript preparation, critical review and final approval of manuscript.

Footnotes

Presentation in Preliminary Form at the Annual Meeting of the American Gastroenterological Association Washington DC, May 2015

No conflicts of interest exist. No writing assistance was obtained.

REFERENCES

- 1.Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:308–28. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.444. quiz 329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trimble KC, Pryde A, Heading RC. Lowered oesophageal sensory thresholds in patients with symptomatic but not excess gastro-oesophageal reflux: evidence for a spectrum of visceral sensitivity in GORD. Gut. 1995;37:7–12. doi: 10.1136/gut.37.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodriguez-Stanley S, Robinson M, Earnest DL, et al. Esophageal hypersensitivity may be a major cause of heartburn. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:628–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galmiche JP, Clouse RE, Balint A, et al. Functional esophageal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1459–65. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clouse RE, Richter JE, Heading RC, et al. Functional esophageal disorders. Gut. 1999;45(Suppl 2):II31–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pandolfino JE, Vela MF. Esophageal-reflux monitoring. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:917–30. 930, e1. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bredenoord AJ, Weusten BL, Timmer R, et al. Addition of esophageal impedance monitoring to pH monitoring increases the yield of symptom association analysis in patients off PPI therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:453–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sifrim D, Castell D, Dent J, et al. Gastro-oesophageal reflux monitoring: review and consensus report on detection and definitions of acid, non-acid, and gas reflux. Gut. 2004;53:1024–31. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.033290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Savarino E, Marabotto E, Zentilin P, et al. The added value of impedance-pH monitoring to Rome III criteria in distinguishing functional heartburn from non-erosive reflux disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:542–7. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mainie I, Tutuian R, Shay S, et al. Acid and non-acid reflux in patients with persistent symptoms despite acid suppressive therapy: a multicentre study using combined ambulatory impedance-pH monitoring. Gut. 2006;55:1398–402. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.087668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel A, Sayuk GS, Gyawali CP. Acid-based parameters on pH-impedance testing predict symptom improvement with medical management better than impedance parameters. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:836–44. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel A, Sayuk GS, Gyawali CP. Parameters on Esophageal pH-Impedance Monitoring That Predict Outcomes of Patients With Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:884–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pandolfino JE, Kim H, Ghosh SK, et al. High-resolution manometry of the EGJ: an analysis of crural diaphragm function in GERD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1056–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaker A, Stoikes N, Drapekin J, et al. Multiple rapid swallow responses during esophageal high-resolution manometry reflect esophageal body peristaltic reserve. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1706–12. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kushnir VM, Prakash Gyawali C. High resolution manometry patterns distinguish acid sensitivity in non-cardiac chest pain. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:1066–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01787.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahrilas PJ, Quigley EM. Clinical esophageal pH recording: a technical review for practice guideline development. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1982–96. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.1101982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghillebert G, Janssens J, Vantrappen G, et al. Ambulatory 24 hour intraoesophageal pH and pressure recordings v provocation tests in the diagnosis of chest pain of oesophageal origin. Gut. 1990;31:738–44. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.7.738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prakash C, Clouse RE. Value of extended recording time with wireless pH monitoring in evaluating gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:329–34. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weusten BL, Roelofs JM, Akkermans LM, et al. The symptom-association probability: an improved method for symptom analysis of 24-hour esophageal pH data. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1741–5. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90815-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kushnir VM, Sathyamurthy A, Drapekin J, et al. Assessment of concordance of symptom reflux association tests in ambulatory pH monitoring. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05066.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weijenborg PW, Cremonini F, Smout AJ, et al. PPI therapy is equally effective in well- defined non-erosive reflux disease and in reflux esophagitis: a meta-analysis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:747–57, e350. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kandulski A, Weigt J, Caro C, et al. Esophageal intraluminal baseline impedance differentiates gastroesophageal reflux disease from functional heartburn. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1075–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weijenborg PW, Smout AJ, Verseijden C, et al. Hypersensitivity to acid is associated with impaired esophageal mucosal integrity in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease with and without esophagitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;307:G323–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00345.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vela MF, Craft BM, Sharma N, et al. Refractory heartburn: comparison of intercellular space diameter in documented GERD vs. functional heartburn. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:844–50. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Savarino E, Zentilin P, Mastracci L, et al. Microscopic esophagitis distinguishes patients with non-erosive reflux disease from those with functional heartburn. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:473–82. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0672-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kushnir VM, Sayuk GS, Gyawali CP. Abnormal GERD parameters on ambulatory pH monitoring predict therapeutic success in noncardiac chest pain. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1032–8. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel A, Sayuk GS, Kushnir VM, et al. GERD phenotypes from pH-impedance monitoring predict symptomatic outcomes on prospective evaluation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015 doi: 10.1111/nmo.12745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slaughter JC, Goutte M, Rymer JA, et al. Caution about overinterpretation of symptom indexes in reflux monitoring for refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:868–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Helm JF, Dodds WJ, Pelc LR, et al. Effect of esophageal emptying and saliva on clearance of acid from the esophagus. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:284–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198402023100503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rohof WO, Bennink RJ, de Jonge H, et al. Increased proximal reflux in a hypersensitive esophagus might explain symptoms resistant to proton pump inhibitors in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1647–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dekel R, Martinez-Hawthorne SD, Guillen RJ, et al. Evaluation of symptom index in identifying gastroesophageal reflux disease-related noncardiac chest pain. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:24–9. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200401000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Broeders JA, Draaisma WA, Bredenoord AJ, et al. Oesophageal acid hypersensitivity is not a contraindication to Nissen fundoplication. Br J Surg. 2009;96:1023–30. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]