Abstract

Background

The profound impact of empathy training on quality nursing care has been recognized. Studies have shown that there has been little improvement in nurses’ communication skills, and that they should work to enhance this area. Relevant training will lead to an improvement in nurses’ empathic skills, which in turn, will enable them to understand their patients better, establish positive interpersonal relationships with them, and boost their professional satisfaction.

Objectives

To reveal the effect of empathy training on the empathic skills of nurses.

Patients and Methods

This study was conducted as an experimental design. The research sample consisted of 48 nurses working at the pediatric clinics of Farabi hospital of Karadeniz Technical University in Turkey (N = 83). Two groups, an experimental group (group 1) and a control group (group 2) were determined after questionnaires were supplied to all nurses in the study sample. At first, it was intended to select these groups using a random method. However, since this may have meant that the experimental and control groups were formed from nurses working in the same service, the two groups were selected from different services to avoid possible interaction between them. The nurses in the Group 1 were provided with empathy training through group and creative drama techniques. Pre-tests and post-tests were conducted on both groups. Data was collected via a questionnaire designed around the topic “empathic skill scale-ESS”, developed by Dokmen. The Kolmogorov Smirnov test was employed to assess whether the measurable data was suitable for normal distribution. Data was presented as numbers and percentage distributions, as mean ± standard deviation and Chi-square, and as student t tests and paired t tests. The level of significance was accepted as P < 0.05.

Results

The nurses in the experimental group had a mean score of 146.7 ± 38.8 and 169.5 ± 22.1 in the ESS pre-test and post-test, respectively. Although the nurses in the control group had a pre-test mean score of 133.7 ± 37.1, which increased to 135.1 ± 51.7 after the training, no statistically significant difference was found (P = 0.886). A comparison of the groups indicated that they scored similarly in the pre-test. However, the experimental group scored significantly higher than the control group in the post-test (P = 0.270 and P = 0.015, respectively).

Conclusions

In the light of these findings, it is recommended that communication skills should be widely included in in-service training programs; similar studies should be conducted on broader control groups formed through randomization; and a comparison should be made between the findings.

Keywords: Empathy, Nursing Care, Communication, Interpersonal Skills

1. Background

Empathy is defined as the ability to understand how others feel and what they mean, and to convey these emotions to others (1). It is currently believed that empathy is multi-dimensional and involves emotional, cognitive, communicative, behavioral, moral, and relational dimensions (1-4). The objective of nurse-patient communication is to ensure that patient needs are identified and necessary care is provided. In order to identify these needs, nurses should be able to fully understand patients’ feelings, opinions, and conditions; this requires empathic knowledge and skills (5). Therefore, empathy is more than simply understanding and handling patients’ verbal expressions (6). Gaining, or training somebody to gain, empathic skills is not an easy process, but it may be facilitated by rich life experiences. Empathic skills are essential for the provision of effective nursing care (7); they are teachable, and important for cooperation-based relationships. It has been reported that the nature of the nursing profession requires nurses to have these skills (8-10). In their study, Reynolds & Scott (9) emphasized that nurses who are able to approach their patients empathetically can better understand their reactions to health problems, as well as the purpose and source of these reactions.

It is well documented in the literature that because some nurses consider themselves as lacking in communication skills, they most worry about being unable to cope with patients; for the same reason, they exhibit behaviors that hinder their communication with patients (11, 12) . In addition, nurses fear that they cannot deal with certain feelings and opinions of patients, due to their insufficient knowledge and educational background (13); they therefore employ communication-blocking behaviors in order to avoid talking about patients’ psychological problems. This also acts as protection against further psychological issues that may arise, not only in themselves, but also in patients (11). Despite the fact that empathy is hugely important in nursing, there have been a number of studies suggesting that nurses have low or intermediate empathic skills (2, 9, 14-18). Wilkinson (16) reported that there had been little improvement in nurses’ communication skills in the twenty years leading up to 1999. Studies have indicated that more efforts should be made for nurses to provide effective care and enhance their empathic and communication skills (9, 14-16, 18).

It has been observed that nursing practices in Turkey are focused on medical care and carried out in the form of routine duties or practices, instead of individualized care that is based on a problem-solving approach in accordance with patient needs (19). Nurses keep their patients at a distance, communication between the two is mechanical, there is a lack of meaningful interaction, and nurses serve the institution rather than their patients. In addition, this approach restricts nursing initiatives and leads nurses to carry out their practices automatically, without thinking or basing their actions on knowledge. Therefore, nurses should be provided with opportunities to gain or improve empathic skills so that they can understand the non-superficial feelings of patients and provide helpful care.

2. Objectives

The purpose of this research, which is based on the experimental design, was to assess the empathic skills of nurses working at the pediatric clinics of the Farabi hospital of Karadeniz Technical University in their interaction with patients, and to test the efficiency of the training provided.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. The Method and Place of the Research

This research was carried out experimentally, between March and June 2011, at a university hospital with a capacity of 749 patients in the province of Trabzon, located in the north-east of Turkey. The clinics providing services to children at the Farabi hospital are: adolescent, nursing, infection, pediatric emergency, pediatric surgery, pediatric oncology, newborn, pediatric polyclinics, and pediatric intensive care services. A total of 83 nurses were working in these clinics at the time of the study.

3.2. The Research Universe

83 nurses working at children’s polyclinics at Farabi hospital of Karadeniz Technical University constituted the universe of the research.

3.3. The Research Sample

48 nurses constituted the sample. It was thought that all 83 nurses would benefit from applying empathy in their practice, but such application was not possible for those working in intensive care units, while those working at clinics may have had specialized interactions with patients. Therefore, they were excluded from the sample. As explained above, the experimental and control groups were selected from different services to avoid possible interaction between services. When determining the experimental group, we chose children’s services which could allow time for training and which were equal in their number of nurses, with the help of the head nurse. All the nurses working in these services were included in the study, without using a sampling method. Therefore, there were more nurses in the control group than in the experimental group: 31 and 17, respectively.

Before the study, we obtained a decision, dated and numbered B.30.2.K.T.Ü. 0.1H.00.00/1013 and 08.09 2009, and the necessary official permission from the hospital management, for the implementation phase of the research. Additionally, we obtained the oral consent of nurses who had volunteered to participate and those who worked at the pediatric clinics.

3.4. Research Design

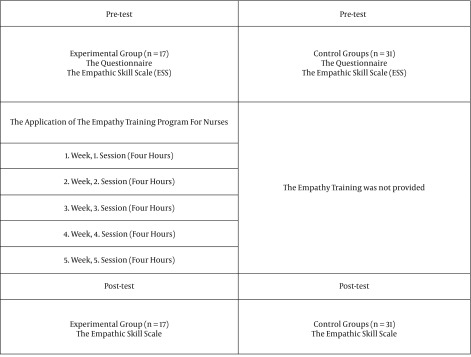

The nurses were divided into two groups to evaluate the efficiency of the training. The nurses in the group 1 (experimental) were provided with empathy training through group and creative drama techniques, whereas group 2 (control) was not group 1 consisted of nurses from the Adolescent, Nursing, and Infection services while group 2 was drawn from the Pediatric Emergency, Pediatric Surgery, and Pediatric Oncology services. Pre-tests and post-tests were conducted on the nurses in both groups.

Figure 1. Flow Chart of Study.

3.5. Research Instruments

Data was collected via a questionnaire designed around the focus topic and the “empathic skill scale” developed by Dokmen (20). The questionnaire consisted of questions about the demographics of the nurses, their professional characteristics, their experiences in empathy, and their empathic skills.

3.6. The Empathic Skill Scale (ESS)

This scale consists of two forms, “A” and “B”. The ESS-B form is based on six different problems encountered in daily life. Each problem is followed by 12 empathic responses that can be addressed to a person suffering from it. Therefore, the respondent is provided with a total of 72 empathic responses (12 for each problem) in written form. One of the 12 responses is irrelevant to the problem, and intentionally included to identify those who are not paying attention. Should a respondent choose even one of these irrelevant responses, which are valued at zero in the scoring, his/her form is excluded from the evaluation. Respondents are asked to choose four of the responses that follow each problem. After they have chosen a total of 24 responses, their performance is graded in accordance with the criteria included in the ESS-A form. The lowest score one can get from the ESS is 62, while the highest is 219. The scale was tested by Dokmen (20) for validity and reliability purposes. It was conducted on a group of 80 individuals twice, the second test being three weeks after the first. The re-test’s reliability was found to be 0.91, based on the evaluation of the scores obtained by 64 respondents.

3.7. The Application of the Empathy Training Program for Nurses

The program started in March 2011 and ended in June 2011. During the process, participants were informed of what was happening and creative drama techniques were employed. Games were used as a kind of warm-up, and sample situations were enacted through roleplay and improvisations, two key drama techniques. Nurses were encouraged to share their feelings and opinions in evaluations at the end of each session and during intervals. The creative drama method was implemented by a researcher who specialized in this field. The program lasted a total of 20 hours (four hours a day) over five sessions. Prior to the program, nurses were informed about the time and place of the sessions, as well as the application of the program and the general rules. It was ensured that all nurses participated voluntarily. Nurses in group 1 were divided into two groups, and provided with successive sessions that took place in the hospital’s training room. The room had been prepared by the researcher so that it would be suitable for group work. The program drew on the models and principles of adult education, and was based on the assumption that the participants would take on their own learning responsibilities. The nurses played an active part in all phases of the training, from planning to evaluation.

The first session included warm-up games based on communication and interaction, as well as name games. The purpose was to ensure that each participant got to know the other members of the group. In addition, observations were carried out on their ability to follow instructions, use their body, develop empathy, and describe themselves. The evaluation that followed the session emphasized basic communication concepts, verbal and non-verbal communication, empathy, and its importance.

The second session started with warm-up games based on communication. Afterwards, the nurses were provided with a worksheet entitled “Who am I?”, which had been designed to identify the extent to which they knew and could express their positive and negative sides. They were asked to draw their own faces inside an oval figure on the worksheet, and were obliged to write about their positive and negative sides inside and outside a rectangle, respectively. The worksheets were then hung on the wall, and the participants reflected on the activity. It was very important to enable them to gain awareness about how much they knew themselves, and how effectively they could express their different sides.

The third session also began with warm-up games. The participants performed a mirroring activity in pairs. They were then provided with instructions on pair improvisations, and asked to play certain roles; they were obliged to determine the roles and conflicts independently. The individuals in each pairs were referred to as either A or B. They were reminded that the instructions they would be provided with would form the introductory part of the improvisations. Pair improvisations began in accordance with the instructions. After a while, they were asked to stop. Finally, each pair presented their parts as instructed by the leader, for example:

A: I want to go out.

B: No, I won’t let you.

Through the evaluations made at the end of the activity, the feelings and opinions of the nurses regarding empathic thinking and improvisations were assessed. The participants were asked the following questions: “Was it difficult to say no?” “Who got permission?” “Did you have any difficulty in persuading?” “Did you experience any problems? If yes, how did you overcome them?” “Speaking of your roles, was any kind of empathy involved? Did you get any ideas about empathic thinking from the improvisations?”

Next, the nurses were asked to divide into groups of four or five to reflect on the question “How should a good nurse behave?”, Write down their ideas on the sheets provided, and present them. A discussion then took place regarding the similarities and differences.

The fourth session started with warm-up games in which the nurses were asked to walk while reflecting certain emotions, including anger, sadness, happiness, fright, embarrassment, surprise, and boredom, through their body language, gestures, and facial expressions, in response to particular situations. The prompts included: “You are very excited,” “you have just got a present,” “you are angry,” “your friend is late for an appointment,” “you are very angry,” “you have received bad news,” “you witnessed an accident while walking on the street,” “you have received news of your mother’s illness on the phone,” “you think you are being followed on the street,” “you have split tea over your guest,” “you have just seen the person you like chatting with someone else at a cafe, they have organized a surprise birthday party for you,” and so on. Afterwards, the nurses were provided with written instructions for pair improvisations and asked to perform them in turns. The following is an example.

3.8. Pair 1

Patient (receiving chemotherapy treatment): I’ve got a sprinkle of hair on the side of my head. No matter what I do, I can’t straighten it. I feel off color whenever I look at myself in the mirror.

Nurse: This is not a big deal. Don’t worry!

Patient: Nobody will like me when I go to school.

3.9. Pair 2

Nurse: This happens when one receives this kind of treatment. You’ll have hair in time (nurse).

Patient: The young girl with renal failure is secretly eating prohibited food.

Nurse: Having realized this, the nurse.

3.10. Pair 3

A: A diabetic child who does not know the severity of their condition

B: Nurse

Following this scenario, the instructor asked the nurses the following questions:

- How did you feel?

- What would you like to say about the communication methods in the roleplays?

- What were the positive and negative factors that prompted you to display empathy?

The indifferent, ineffective, offensive, or superficial responses or reflections that resulted from a lack of empathic listening were analyzed. The importance of listening was emphasized.

In the fifth session, the nurses were asked to form groups of three or four individuals and to present improvisations that would represent the patients and problems in their units. This was followed by an evaluation which sought answers to the questions: “How empathetically can we behave?” and “what kind of conflicts do you experience while working?”

At the end of the program, a discussion was held over the conventional definitions of empathy and communication techniques, the importance of empathy in nursing was stressed, and the participants were asked to evaluate the program.

3.11. Scope and Limitations of the Study

The study’s results were generalizable only to the nurses who provided care to the pediatric patients at Farabi medical faculty hospital of Karadeniz Technical University.

3.12. Data Analyses

The Kolmogorov Smirnov test was used to assess whether the measurable data was suitable for normal distribution. Student t tests were used to make comparisons between the two groups, while paired t tests were used to make comparisons between the scores of each group before and after the training. The qualitative data was analyzed using the Chi-square test. Measurable data was presented in ± standard deviations, while qualitative data was presented in numerals (%). The level of significance was accepted as P < 0.05.

4. Results

Table 1 shows that most of the nurses in Groups 1 and 2 were ≤ 30 years old, did not have a child, had a graduate or postgraduate degree, had three or more siblings, and belonged to a nuclear family. There was no statistical difference between the two groups in the variables.

Table 1. The Distribution of Nurses According to Socio-Demographic Characteristics.

| Variables | Group I (n = 17)a | Group II (n = 31)a | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| ≤ 30 | 11 (64.7) | 22 (71.9) | 0.654 |

| > 30 | 6 (35.3) | 9 (29.0) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 7 (41.2) | 10 (32.3) | 0.537 |

| Single | 10 (58.8) | 21 (67.7) | |

| Have a child | |||

| Yes | 6 (35.3) | 6 (19.4) | 0.300 |

| No | 11 (64.7) | 25 (80.6) | |

| Educational status | - | ||

| Graduate or lower | 3 (17.6) | 7 (22.6) | |

| Graduate or higher | 14 (82.4) | 24 (77.4) | |

| Number of siblings | |||

| < 3 | 5 (29.4) | 13 (42.0) | 0.391 |

| ≥ 3 | 12 (70.6) | 18 (58.0) | |

| Family type | |||

| Nuclear | 14 (82.4) | 29 (93.5) | 0.331 |

| Extended | 3 (17.6) | 2 (6.5) |

aValues are presented as No. (%).

Table 2 presents the nurses’ professional characteristics. Most of the participants in group 1 stated that they had been a nurse and serving their units for six years or less, they were serving at least 11 patients, they were quite satisfied with their relationships with their managers, they had chosen the nursing profession voluntarily, they were happy to work as a nurse, and that they had not chosen their units voluntarily. Most of the participants in group 2 stated that they had been a nurse and serving their units for ≤ six years, they were serving > 11 patients, they were partially satisfied with their working environment, they were satisfied with their relationships with their managers, they had not chosen the nursing profession voluntarily, and that they were quite happy to work as a nurse. A significant difference was determined between the two groups in terms of the number of nurses who reported that they had not chosen their units voluntarily (P = 0.031).

Table 2. The Distribution of Nurses by Their Professional Characteristics.

| Characteristics | Group I (n = 17)a | Group II (n = 31)a | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of years worked at their current unit | |||

| ≤ 6 years | 13 (76.5) | 27 (87.1) | |

| ≥ 7 years | 4 (23.5) | 4 (12.9) | 0.428 |

| Number of years worked in the profession | |||

| ≤ 6 years | 10 (58.8) | 20 (64.5) | |

| ≥ 7 years | 7 (41.2) | 11 (35.5) | 0.697 |

| Working hours | |||

| Constantly 08 - 16 | - | - | |

| Constantly 16 - 08 | - | - | - |

| Mixed | 17 (100.0) | 31 (100.0) | |

| Number of patients served | |||

| 1 – 10 | - | 14 (45.2) | |

| > 11 | 17 (100) | 17 (54.8) | |

| Level of satisfaction with the working environment | |||

| Satisfied | 8 (47.1) | 9 (29.0) | |

| Dissatisfied | 9 (52.9) | 22 (71.0) | 0.212 |

| Level of satisfaction with managers | |||

| Satisfied | 11 (64.7) | 15 (48.4) | |

| Dissatisfied | 6 (35.3) | 16 (51.6) | 0.278 |

| Choosing the nursing profession voluntarily | |||

| Yes | 11 (64.7) | 14 (45.2) | |

| No | 6 (35.3) | 17 (54.8) | 0.195 |

| Level of satisfaction with working as a nurse | |||

| Satisfied | 15 (88.2) | 23 (74.2) | |

| Dissatisfied | 2 (11.8) | 8 (25.8) | 0.459 |

| Choosing the unit | |||

| Voluntarily | 2 (11.8) | 13 (41.9) | |

| Involuntarily | 15 (88.2) | 18 (58.1) | 0.031 |

aValues are presented as No. (%).

Most of the nurses in both groups stated that they did not have difficulty in communicating with pediatric patients, they could not allocate sufficient time to the patients they were supposed to serve, they often regarded themselves as competent in understanding patients, and that they approached patients empathetically; this is shown in Table 3. No significant difference between the groups’ variables was found (P > 0.005).

Table 3. The Experience and Evaluations of Nurses in Terms of Empathy.

| Variables | Group I (n = 17)a | Group II (n = 31)a | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Having difficulty in communicating with pediatric patients | |||

| Yes | 4 (23.5) | 3 (9.7) | 0.226 |

| No | 13 (76.5) | 28 (90.3) | |

| Being able to allocate enough time to patients needing attention | |||

| Able | 6 (35.3) | 9 (29.0) | 0.654 |

| Unable | 11 (64.7) | 22 (71.0) | |

| Considering oneself competent in understanding patients | |||

| Feeling competent | 11 (64.7) | 27 (87.1) | 0.134 |

| Feeling incompetent | 6 (35.3) | 4 (12.9) | |

| Approaching patients empathetically | |||

| Yes | 12 (70.6) | 25 (80.6) | 0.460 |

| No | 5 (29.4) | 6 (19.3) |

aValues are presented as No. (%).

Most nurses in both groups stated that empathy was satisfactorily covered in their pre-graduation education, they did not receive any training in empathy after graduation, they believed in the necessity of intermittent but continuing training, and that they were not a member of any association. However, most of those in group 1 reported that their post-graduation empathy training was insufficient in terms of communication skills, they did not consider that they needed knowledge about empathy, they did not receive in-service training on empathy, they did not follow any publications on this topic, and they did not participate in any activities to do with empathy (P > 0.005). These results are given in Table 4.

Table 4. The Distribution of Nurses by Their Background in Empathic Skills.

| Variables | Group I (n = 17)a | Group II (n = 31)a | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusion of empathy in pre-graduation education | |||

| Included | 9 (52.9) | 21 (67.7) | 0.311 |

| Not included | 8 (47.1) | 10 (32.3) | |

| Receiving empathy training after graduation | |||

| Received | 3 (17.6) | 9 (29.0) | 0.497 |

| Not received | 14 (82.4) | 22 (71.0) | |

| The sufficiency of the empathy training received after graduation in terms of communication skills | |||

| Sufficient | 5 (29.4) | 16 (51.6) | 0.138 |

| Insufficient | 12 (70.6) | 15 (48.4) | |

| Thinking that knowledge about empathy is needed | |||

| Yes | 7 (41.2) | 19 (61.3) | 0.181 |

| No | 10 (58.8) | 12 (38.7) | |

| Believing in the necessity of intermittent but continuous training | - | ||

| Yes | 13 (76.5) | 23 (74.2) | |

| No | 4 (23.5) | 8 (25.8) | |

| Receiving in-service training | |||

| Yes | 6 (35.3) | 19 (61.3) | 0.085 |

| No | 11 (64.7) | 12 (38.7) | |

| Following publications | |||

| Yes | 8 (47.1) | 16 (51.6) | 0.763 |

| No | 9 (52.9) | 15 (48.4) | |

| Being a member of an association | |||

| Yes | 1 (5.9) | 0 | 0.354 |

| No | 16 (94.1) | 31 (100.0) | |

| Participating in activities | |||

| Yes | 6 (35.3) | 18 (58.1) | 0.131 |

| No | 11 (64.7) | 13 (41.9) | |

| Participating in training related to empathy | |||

| Yes | - | ||

| No | 17 (100.5) | 31(100.0) |

aValues are presented as No. (%).

The nurses in group 1 had a mean score of 146.7 ± 38.8 and 169.5 ± 22.1 in the ESS pre-test and post-test, respectively. Although the nurses in group 2 had an ESS pre-test mean score of 133.7 ± 37.1 and a post-test mean score of 135.1 ± 51.7, no statistically significant difference was found (P = 0.886). A comparison of the two groups indicated that they had similar scores in the pre-test. However, group 1 scored significantly higher than group 2 in the post-test (P = 0.270 and P = 0.015, respectively) (Table 5).

Table 5. The Empathic Skill Scale Scores of the Two Groups Before and After Training.

| Before | After | Paired t (t Value) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | 146.7 ± 38.8 | 169.5 ± 22.1 | 2.242 | 0.041 |

| Group 2 | 133.7 ± 37.1 | 135.1 ± 51.7 | 0.135 | 0.886 |

| Student t (t value) | 1.117 | 2.535 | ||

| P value | 0.270 | 0.015 |

5. Discussion

Empathy is a teachable communicative skill; however, there are many problems related to communication training, not only at school but after (21-25). These problems are linked to educational programs, the gap between theory and practice, and the amount of importance attached to communication in the healthcare system. In addition, there is a lack of consensus on the concept of empathy, how to measure empathy in training, and how to highlight its importance in a well-structured training program.

Didactic, role-play, and drama techniques were used in the study. The effect of the empathy training was measured via the “empathic skill scale” developed by Dokmen (20). In parallel with the literature (6, 18, 26-29), the present study suggests that the empathy training program is effective in enhancing the empathy levels of nurses. Our research has found no significant difference between the empathy skill levels of nurses in group 1 and group 2, which were evaluated in terms of socio-demographic characteristics, experience and evaluation of empathy, and accumulation of empathic skills. According to the professional features of nurses, on the other hand, a significant difference was found between “empathy skill levels” of the nurses in group 1 and group 2 and “voluntarily choosing the unit worked at” (Table 2). When the groups were compared in terms of their empathic skill scores, they were found to be close to each other in the last test, whereas Group 1’s score was found to be statistically significantly higher than group 2’s in the second test. This result indicates that the quality of empathy training affects nurses’ development of empathic skills (Table 5). Several studies have found that such training programs prove to be effective when carried out in small groups and accompanied by various methods with student-centered and didactic elements (24, 25, 30). Similarly, this study suggests that it is more effective to collectively use a number of methods such as exercises, experience stories, discussions, roleplays, homework, question-answer sessions, and explanations, when improving nurses’ empathy skills. The training was based on the models and principles of adult education, and lasted for 16 hours over five sessions. The participants were provided with homework, and actively participated in small groups. It is without doubt that longer training would be more useful. In the literature, communication training varies between two and 10 weeks and lasts for six to 100 hours, while samples range between 8 and 218 (8, 16, 22, 24, 25).

In some of the studies conducted in Turkey, most of the data obtained especially through verbal, written, or other qualitative instruments indicates that empathic behaviors are heavily experienced. This can also be seen in the reflections of postgraduate students of creative drama (during or after the sessions) and of individuals participating in creative drama leadership/instructor programs in various institutions. These findings suggest that creative drama processes enable one to gain and improve empathic behaviors. Nevertheless, it seems that it is necessary to design and put into practice long-term creative drama sessions that are based on empathic skills. It should be noted that empathic skills cannot be developed overnight. They can only be improved in line with increased life experiences and first-hand interactions (31).

In conclusion, it was found that the ESS mean scores of the nurses increased after the training, which suggests that empathic training is effective in enabling nurses to gain empathic skills. More studies are required to reveal whether these acquired skills are used in communication with patients and whether they are permanently incorporated into behaviors.

In the light of these findings, it is recommended that in-service training programs should be implemented at hospitals to develop empathic communication skills, they should be maintained regularly, their efficiency and usability should be monitored, and that comparative studies should be conducted to reveal how pediatric patients and nurses are influenced by the improved communicative skills.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our very great appreciation to the scientific research unit of Karadeniz Technical University for its invaluable contributions to the present study no. 2009.101.15.1, entitled “the effect of empathy training on the empathic communication skills of nurses.”

Footnotes

Authors’ Contribution:Study concept and design: İlknur Kahriman, Acquisition of data: Süheyla Kasım, Analysis and interpretation of data: Murat Topbaş and Gamze Çan, Drafting of the manuscript: Nesrin Nural, Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: İlknur Kahriman, Murat Topbaş, and Gamze Çan, Statistical analysis: Ümit Arslan, Administrative, technical, and material support and implementation of empathy training study supervision: İlknur Kahriman.

Funding/Support:This study was supported in part by the Scientific Research Unit of Karadeniz Technical University.

References

- 1.Richendoller NR, Weaver JB. Exploring the links between personality and empathic response style. Pers Individ Differ. 1994;17(3):303–11. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reid-Ponte P. Distress in cancer patients and primary nurses' empathy skills. Cancer Nurs. 1992;15(4):283–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olsen DP. Empathetic maturity: theory of moral point of view in clinical relations. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2001;24(1):36–46. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200109000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cliffordson C. The hierarchical structure of empathy: dimensional organization and relations to social functioning. Scand J Psychol. 2002;43(1):49–59. doi: 10.1111/1467-9450.00268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hemsley B, Sigafoos J, Balandin S, Forbes R, Taylor C, Green VA, et al. Nursing the patient with severe communication impairment. J Adv Nurs. 2001;35(6):827–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LaMonica EL, Karshmer JF. Empathy: educating nurses in professional practice. J Nurs Educ. 1978;17(2):3–11. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198601000-0000139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu J, Kirk M. Measurement of empathy in nursing research: systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2008;64(5):440–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reynolds WJ, Scott B. Empathy: a crucial component of the helping relationship. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 1999;6(5):363–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2850.1999.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reynolds WJ, Scott B. Do nurses and other professional helpers normally display much empathy? J Adv Nurs. 2000;31(1):226–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ozcan CT, Oflaz F, Sutcu Cicek H. Empathy: the effects of undergraduate nursing education in Turkey. Int Nurs Rev. 2010;57(4):493–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2010.00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkinson S. Factors which influence how nurses communicate with cancer patients. J Adv Nurs. 1991;16(6):677–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1991.tb01726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Booth K, Maguire P, Hillier VF. Measurement of communication skills in cancer care: myth or reality? J Adv Nurs. 1999;30(5):1073–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maguire P, Booth K, Elliott C, Jones B. Helping health professionals involved in cancer care acquire key interviewing skills--the impact of workshops. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A(9):1486–9. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(96)00059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams A. Where has all the empathy gone? Prof Nurse. 1992;8(2):134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baillie L. A phenomenological study of the nature of empathy. J Adv Nurs. 1996;24(6):1300–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1996.tb01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilkinson S. Schering Plough clinical lecture communication: it makes a difference. Cancer Nurs. 1999;22(1):17–20. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199902000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams J, Stickley T. Empathy and nurse education. Nurse Educ Today. 2010;30(8):752–5. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ancel G. Developing empathy in nurses: an inservice training program. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2006;20(6):249–57. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goksel EY. The examination of nurse behaviours observed in clinical studies in terms of dependent, independent, and inter-dependent decisions [Dissertation]. Ankara: Hacettepe University; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dokmen U. Communication conflicts and empathy. Istanbul: Sistem Publishing; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashmore R, Banks D. Student nurses perceptions of their interpersonal skills: a re-examination of Burnard and Morrison's findings. Int J Nurs Stud. 1997;34(5):335–45. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(97)00025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kruijver IP, Kerkstra A, Francke AL, Bensing JM, van de Wiel HB. Evaluation of communication training programs in nursing care: a review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;39(1):129–45. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suikkala A, Leino-Kilpi H. Nursing student-patient relationship: a review of the literature from 1984 to 1998. J Adv Nurs. 2001;33(1):42–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chant S, Randle J, Russell G, Webb C, Tim. Communication skills training in healthcare: a review of the literature. Nurse Educ Today. 2002;22(3):189–202. doi: 10.1054/nedt.2001.0690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gysels M, Richardson A, Higginson IJ. Communication training for health professionals who care for patients with cancer: a systematic review of training methods. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13(6):356–66. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0732-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herbek TA, Yammarino FJ. Empathy training for hospital staff nurses. Group Organ Manage. 1990;15(3):279–95. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oz F. Impact of training on empathic communication skills and tendency of nurses. Clin Excell Nurse Pract. 2001;5(1):44–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lauder W, Reynolds W, Smith A, Sharkey S. A comparison of therapeutic commitment, role support, role competency and empathy in three cohorts of nursing students. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2002;9(4):483–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2850.2002.00510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Unal S, Oz F. Communication skills training program for oncology nurses in order to develop their relations with patients: an observational study. J NurS. 2008;15(2):52–67. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Razavi D, Delvaux N. Communication skills and psychological training in oncology. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33 Suppl 6:S15–21. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)00195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adıguzel, O. Creative drama in education. Ankara: Naturel Publishing; 2010. [Google Scholar]