Abstract

Rice is a short-day plant. Short-day length promotes heading, and long-day length suppresses heading. Many studies have evaluated rice heading in field conditions in which some individuals in the population were exposed to various day lengths, including short and long days, prior to a growth phase transition. In this study, we investigated heading date under natural short-day conditions (SD) and long-day conditions (LD) for 100s of accessions and separately conducted genome-wide association studies within indica and japonica subpopulations. Under LD, three and four quantitative trait loci (QTLs) were identified in indica and japonica subpopulations, respectively, two of which were less than 80 kb from the known genes Hd17 and Ghd7. But no common QTLs were detected in both subpopulations. Under SD, six QTLs were detected in indica, three of which were less than 80 kb from the known heading date genes Ghd7, Ehd1, and RCN1. But no QTLs were detected in japonica subpopulation. qHd3 under SD and qHd4 under LD were two novel major QTLs, which deserve isolation in the future. Eleven known heading date genes were used to test the power of association mapping at the haplotype level. Hd17, Ghd7, Ehd1, and RCN1 were again detected at more significant level and three additional genes, Hd3a, OsMADS56, and Ghd7.1, were detected. However, of the detected seven genes, only one gene, Hd17, was commonly detected in both subpopulations and two genes, Ghd7 and Ghd7.1, were commonly detected in indica subpopulation under both conditions. Moreover, haplotype analysis identified favorable haplotypes of Ghd7 and OsMADS56 for breeding design. In conclusion, diverse heading date genes/QTLs between indica and japonica subpopulations responded to SD and LD, and haplotype-level association mapping was more powerful than SNP-level association in rice.

Keywords: heading date, long and short-day conditions, genome-wide association studies, haplotype-level association

Introduction

Rice as a short-day plant is cultivated from latitudes of 55°N in China to 36°S in Chile (Khush, 1997). Rice heading date is an important trait to adapt to various regional environments and is usually related to grain yield. Many isolated QTLs showed varying photoperiod sensitivities between SD and LD. Under SD, heading date is promoted by two independent pathways mediated by Heading date 1 (Hd1) and Early heading date 1 (Ehd1). Hd1 is a homolog of CONSTANS in Arabidopsis. Ehd1 encoding a B-type response regulator has no ortholog in Arabidopsis. Hd1 and Ehd1 up-regulated the expression of the FT-like (florigen) Hd3a genes (Yano et al., 2000; Doi et al., 2004). Ehd2, Ehd3, and Ehd4 promote heading by up-regulating Ehd1 under SD conditions (Matsubara et al., 2008, 2011; Gao et al., 2013). Most day-length-sensitive heading date QTLs, such as Hd6, Ghd7, OsMADS56, OsMADS50, Hd17, DTH2, Hd16, and Ghd7.1, function specifically under LD (Takahashi et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2004; Xue et al., 2008; Ryu et al., 2009; Matsubara et al., 2012; Hori et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013). Among these QTLs, OsMADS50, Hd17, and DTH2 promote heading but the others delay heading under LD. Interestingly, both Hd1 and DTH8/Ghd8 delay heading under LD and promote heading under SD (Yano et al., 2000; Wei et al., 2010).

A genome-wide association study (GWAS) combining high-density markers with a diverse germplasm collection provides higher mapping resolution than conventional QTL mapping based on bi-parent derived segregating populations and enables the prediction or identification of causal genes. GWAS has been widely used to identify loci related to various important agronomical traits in rice (Huang et al., 2010, 2012; Zhao et al., 2011). For heading date, Huang et al. (2012) associated three known heading date genes of OsGI, Hd3a, and RCN1 with worldwide rice varieties in natural conditions. They were all detected in indica subpopulation but OsGI was also detected in japonica subpopulation. However, the major gene Ghd7 was not detected. Zhao et al. (2011) conducted experiments in three environments: LD (12–14 h), 12–13 h day-length condition in the field and one very long to very short day-length condition (~18–6 h) in a greenhouse. They identified 10 candidate heading date genes. Hd1 was the only one repeatedly detected in multiple environments. In both studies, the power of genome-wide association mapping for heading date QTLs is low because few known genes have been identified. The low power of association mapping at the single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) level is primarily caused by low resolution in grouping samples into two genotypes. Notably, for adaptive genes in rice such as Ghd7 and Ghd7.1, several alleles/haplotypes exist in nature. Each allele has a different genetic effect and results in a specific geographic distribution (Xue et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2013). Therefore, association mapping at the haplotype level is expected to be more powerful because the germplasm collection can be classified into several genotypes (as opposed to two genotypes via SNP). Additionally, the heading date data collected from the population grown under mixed LD and SD conditions for GWAS likely leads to deviation because some heading date genes such as Hd1 have opposing effects on heading between SD and LD, which eliminate their genetic effects and result in failed detection.

Indica and japonica rice varieties have distinct growing zones and cropping seasons. It is naturally questioned whether different genes control heading date between indica and japonica subpopulations under LD and SD. To answer the questions, heading date was recorded for a global rice collection under SD and LD in this study, and GWAS for heading date was independently performed in indica and japonica subpopulations under SD and LD. To check the power of haplotype-level GWAS, 11 known heading date genes were tested. Our results revealed a diverse genetic basis for heading date between indica and japonica subpopulations under two conditions and a greatly improved power of haplotype-level GWAS as compared to SNP-level GWAS.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material, Field Experiments, and Heading Date Record

A diverse worldwide collection of 529 Oryza sativa accessions were planted on April 17 in a bird net-equipped field in the experimental farm of Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, China (114° 21′ E, 30° 28′ N) during the summer seasons of 2013 and 2014 and in the winter season, 2012–2013 (on December 5) in Hainan Island, China (110° 01′ E, 18° 30′ N). Field trials were carried out following a randomized complete block design with two replications within each year. The seedlings of each accession were transplanted after 25 days into one row in the field, with a distance of 16.5 cm × 26.4 cm within and between the rows. The heading dates of five plants in the middle of each row were individually recorded. Every 2 days, the heading date was recorded as the days from sowing to the first panicle appearance. The average trait value for each accession across two replicates within each year was used for separate GWAS.

SNP Database

In total, 529 O. sativa landrace and elite accessions were genotyped via sequencing (Chen et al., 2014). The SNP information is available on RiceVarMap1, a comprehensive database of rice genomic variations, while the SNP physical locations were cited using the genome of TIGR Rice Loci 6.

Genome-Wide Association Study

A total of 2,767,159 and 1,857,845 SNPs (minor allele frequency ≥0.05; the number of accessions with minor alleles ≥6) were used for GWAS in indica and japonica subpopulations, respectively (Chen et al., 2014). Linear mixed models (LMM) were used to make associations by running the Fast-LMM program (Lippert et al., 2011). Population structure was controlled using a kinship matrix constructed with all SNPs. Using a method described by (Li et al., 2012), the effective numbers of independent SNPs were calculated as 571,843 and 245,348 for both indica and japonica subpopulations, respectively. The suggested P-values were specified as 1.8 × 10-6 in indica and 1.3 × 10-6 in japonica (Chen et al., 2014). The thresholds were then set at P = 8.0 × 10-7 in Wuhan and P = 3.8 × 10-7 in Hainan to identify significant association signals via LMM. To obtain independent association signals, multiple SNPs exceeding the threshold in a 5-Mb sliding window were clustered by r2 of linkage disequilibrium ≥0.25, and SNPs with the minimum P-value in a cluster were considered lead SNPs. The detailed method was previously described (Chen et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015).

Haplotype and Statistical Analyses

SNPs within genes used to define haplotypes for 11 known heading date genes including Hd17, Ghd7, Ehd1, RCN1, Hd1, Ghd8, Ghd7.1, DTH2, Hd3a, OsMADS50, and OsMADS56 were downloaded2; the haplotypes were then reconstructed using PHASE software (Stephens et al., 2001) to do imputation for the missing and heterozygous SNPs. The haplotypes with an allele frequency ≥0.01 (5 accessions) were included for association analysis via ANOVA; then, a Duncan test (Post-hoc analysis) was conducted to show the difference in heading date between all possible haplotype pairs.

For each condition, the lead SNPs of the associations detected via GWAS were fit into a linear model using an lm function in R software3, and the phenotype variations explained by each lead SNP and by all lead SNPs together were estimated.

Results

Day Length of the Rice-Growing Season in Hainan and Wuhan

The day length of 13.5 h was set as the boundary between SD and LD (Itoh et al., 2010). Throughout the winter growing season (December–April) in Hainan, the day length ranged from 11.0 to 12.5 h, which is a typical SD. Therefore, all 529 accessions completed their life cycles under SD in Hainan. However, in Wuhan, the summer season day length increased from 13.0 to 14.2 h (April 17–June 22) and then decreased from 14.2 to 12.2 h (June 22–September 21). Therefore, some accessions completed heading under LD; however, some accessions first encountered LD and then experienced SD prior to heading.

Approximately 25 days were required for rice to complete panicle development from the growth phase transition to heading (Vergara et al., 1966; Chang et al., 1969; Liu et al., 2013). In Wuhan, the day length decreased from 13.5 h after August 6, thus the accessions that completed heading prior to August 30 initiated the transition from a vegetative to a reproductive phase under LD. To precisely evaluate the effects of LD conditions on heading date, we removed 26 accessions that experienced mixed LD and SD prior to the phase transition and kept 503 accessions that completed the phase transition under LD (headed prior to August 30) in Wuhan.

Variation of Heading Date in 503 Diverse Accessions

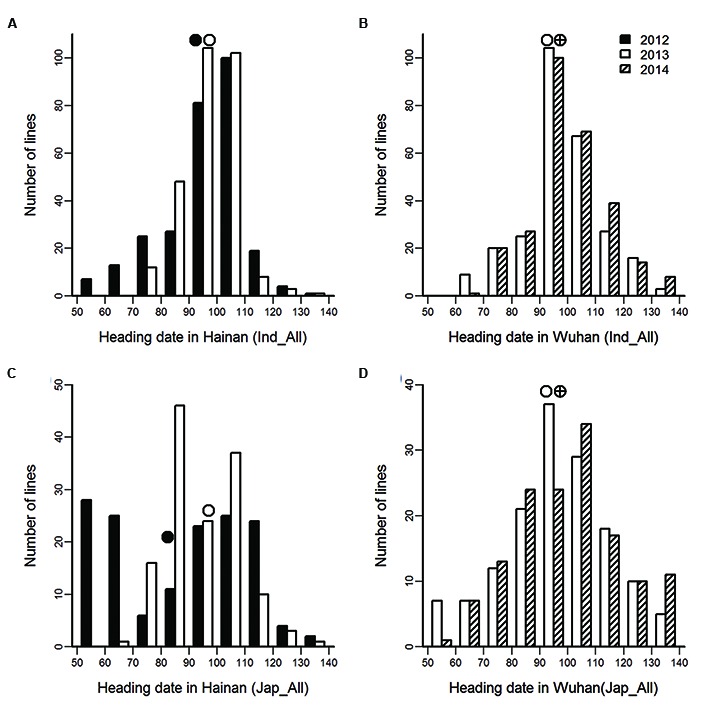

A structural analysis indicated that the entire collection was divided into several distinct subpopulations such as indica, japonica, aus and mixture (Chen et al., 2014). Heading date exhibited large variation in the 503 accessions, the mean values of heading date in the indica subpopulation were equivalent to those in japonica rice either in Wuhan or Hainan, with the exception of heading date in 2012 in Hainan (Figure 1). The correlation coefficient of heading date between the 2 years was 0.94 in Wuhan and 0.86 in Hainan. The correlation coefficients between different locations were significant but substantially lower than that between years in the same locations (Table 1). Two-way ANOVA showed significant genotype and environment effects on heading date (Table 2). The genetic factor accounted for the most phenotypic variance (59.5%) and the environmental effect contributed 4.6% of the phenotypic variance, indicating that many accessions showed differing heading dates between the four environments.

FIGURE 1.

Performance of heading date in the indica (A,B) and japonica (C,D) subpopulations. The circles indicated mean values of heading date.

Table 1.

Correlations of heading dates of 503 accessions in different environments.

| Environments | HN2013 | WH2013 | WH2014 |

|---|---|---|---|

| HN2012 | 0.86 | 0.37 | 0.31 |

| HN2013 | 0.44 | 0.42 | |

| WH2013 | 0.94 |

Table 2.

Genotypes and environments analysis of variance for heading date using 503 accessions.

| SV | Heading date |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| SSG/SST (%) | F | P | |

| G | 59.5 | 4.8 | <0.0001 |

| E | 4.6 | 63.5 | <0.0001 |

SV, source of variance; G, genotype; E, environment.

QTL Detection Using GWAS in Wuhan (LD)

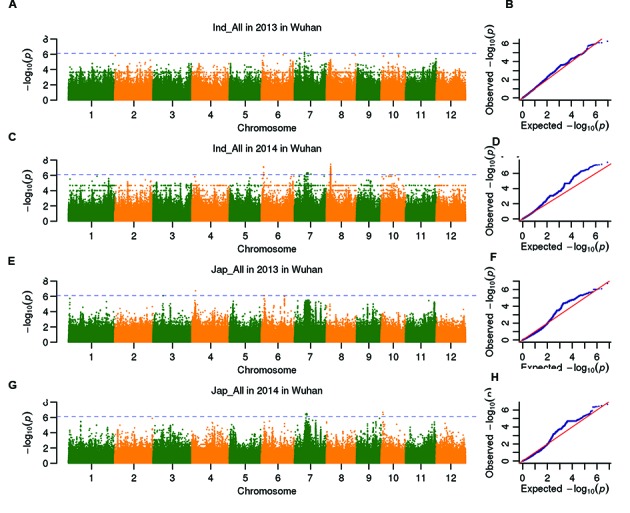

The 278 indica and 147 japonica accessions (after removed 78 of the aus or admixed subpopulations) were utilized for GWAS to avoid structure noise. GWAS was separately performed in indica and japonica subpopulations. A total of seven associations with heading date were detected in Wuhan, three and four QTLs were detected in indica and japonica subpopulations, respectively (Figure 2; Table 3). Two QTLs (qHd6.1 and qHd7.1) on chromosomes 6 and 7 were repeatedly detected in indica subpopulation and individually explained 18.7–19.7% and 7.1–7.3% of the phenotypic variance, respectively. The lead SNP Sf602312322 for qHd6.1 was 78.2 kb to Hd17, and the lead SNP Sf709177919 for qHd7.1 located in 25.5 kb from Ghd7. In japonica subpopulation, qHd6.2 was repeatedly associated with the heading date in 2 years, however, there are no reported heading date genes nearby qHd6.2. qHd4 was detected only in 2013 but exhibited the largest contribution (26.1%) to the variation in heading date. No common association was detected in either subpopulation. The QTLs detected in indica subpopulation cumulatively explained 27.1 and 35.3% of the phenotypic variations in 2013 and 2014, respectively. The QTLs in japonica subpopulations explained more variation in the heading date (39.4 and 40.8% in the 2 years, respectively).

FIGURE 2.

Genome-wide P-values (A,C,E,G) and QQ plots (B,D,F,H) from the LMM model for heading date in indica and japonica in Wuhan are demonstrated in the four panels. The horizontal dashed line (A,C,E,G) indicates the genome-wide significance threshold (P = 8.0 × 107).

Table 3.

Genome-wide significant association signals for heading date in indica and japonica subpopulations using the LMM method in Wuhan (long day conditions).

| QTL | Lead SNP | Chr. | Linkage disequilibrium interval (bp) | Distance to gene |

Indica 2013 |

Indica 2014 |

Japonica 2013 |

Japonica 2014 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | P.V (%) | P | P.V (%) | P | P.V (%) | P | P.V (%) | |||||

| qHd4 | Sf0403512804 | 4 | 3145576–3733894 | 1.8E-7 | 26.1 | |||||||

| qHd6.1 | Sf0602312322 | 6 | 2311322–2931955 | 78.2 kb to Hd17 | 1.6E-6 | 19.7 | 4.4E-7 | 18.7 | ||||

| qHd6.2 | Sf0602663020 | 6 | 2396433–2733565 | 8.0E-7 | 13.2 | 4.4E-6 | 16.8 | |||||

| qHd7.1 | Sf0709177919 | 7 | 9137593–9196135 | -25.5 kb to Ghd7 | 5.7E-7 | 7.3 | 1.1E-6 | 7.1 | ||||

| qHd7.2 | Sf0711412802 | 7 | 11316108–11898697 | 3.1E-7 | 16.6 | |||||||

| qHd8 | Sf0804089477 | 8 | 3942483–4245642 | 3.5E-8 | 9.5 | |||||||

| qHd10.1 | Sf1001634949 | 10 | 1596335–1634949 | 2.2E-7 | 7.4 | |||||||

| Total estimation | 7.2E-19 | 27.1 | 4.0E-25 | 35.3 | 3.8E-16 | 39.4 | 3.2E-15 | 40.8 | ||||

Linkage disequilibrium interval means the linkage disequilibrium (r2 > 0.2) extended genome region surrounding the lead SNP. P is P-value estimated in LMM, P.V (%) is phenotype variance explained by the QTL in percent.

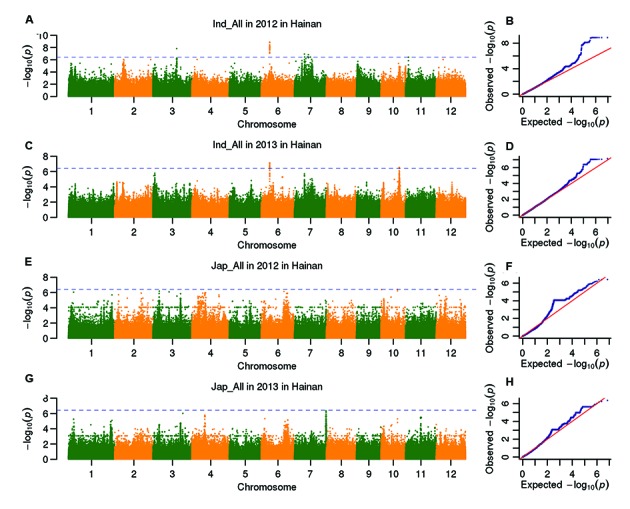

QTL Detection via GWAS in Hainan (SD)

Six heading date QTLs in indica subpopulation and no QTLs in japonica subpopulation were detected under SD (Figure 3; Table 4). Two QTLs (qHd6.3 and qHd7.1) on chromosomes 6 and 7 were repeatedly detected in 2 years indica subpopulation. qHd6.3 and qHd7.1 primarily explained 26.5% and 10.0% of the phenotypic variations, respectively. In total, the QTLs explained 57.7% and 41.3% of the phenotypic variation, respectively, in 2 years in indica subpopulation. Three QTLs were located near known heading date genes: the lead SNP Sf709158944 for qHd7.1 was 6.5 kb to Ghd7, the lead SNP Sf1017100637 for qHd10.1 was 24.5 kb to Ehd1 and the lead SNP Sf1102480009 for qHd11 was 27.5 kb to RCN1.

FIGURE 3.

Genome-wide P-values (A,C,E,G) and QQ plots (B,D,F,H) from the LMM model for heading date in indica and japonica in Hainan are demonstrated in the four panels. The horizontal dashed line (A,C,E,G) indicates the genome-wide significance threshold (P = 3.8 × 107).

Table 4.

Genome-wide significant association signals for heading date in the indica subpopulations using the LMM method in Hainan (short day conditions).

| QTL | Lead SNP | Chr. | Linkage disequilibrium interval (bp) | Distance to gene |

Indica 2012 |

Indica 2013 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | P.V (%) | P | P.V (%) | |||||

| qHd3 | Sf0322143338 | 3 | 22079360–22143338 | 1.4E-8 | 23.3 | |||

| qHd6.3 | Sf0607922178 | 6 | 7917158–8424734 | 1.3E-9 | 22.0 | 1.1E-8 | 26.5 | |

| qHd7.1 | Sf0709158944 | 7 | 9137593–9196135 | -6.5 kb to Ghd7 | 1.2E-7 | 7.7 | 2.0E-6 | 10.0 |

| qHd7.3 | Sf0712842846 | 7 | 12774834–12894276 | 1.4E-7 | 1.1 | |||

| qHd10.2 | Sf1017100637 | 10 | 16691541–17385511 | -24.5 kb to Ehd1 | 2.9E-7 | 4.7 | ||

| qHd11 | Sf1102480009 | 11 | 2357177–2488304 | -27.5 kb to RCN1 | 3.8E-07 | 3.5 | ||

| Total estimation | 2.1E-46 | 57.7 | 1.0E-30 | 41.3 | ||||

Linkage disequilibrium interval means the linkage disequilibrium (r2> 0.2) extended genome region surrounding the lead SNP. P is P-value estimated in LMM, P.V (%) is phenotype variance explained by the QTL in percent.

Haplotype-Level Association Analysis of 11 Known Heading Date Genes

To date, dozens of heading date genes have been cloned in rice. However, only four QTLs in our study were located near heading date genes, which were less than 80 kb from the corresponding lead SNPs. The average linkage disequilibrium decay in these indica and japonica groups extended 93 and 171 kb, respectively4, which was similar to the estimates of 75–123 kb in indica and 150–167 kb in japonica in other studies (Zhao et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2012). In our study, lead SNPs pointed to the four QTLs (qHd6.1, qHd7.1, qHd10.1, and qHd11) were in linkage disequilibrium with known heading date genes of Hd17, Ghd7, Ehd1, and RCN1, respectively (Tables 3 and 4). Thus, these heading date genes most likely underlined these four QTLs. We questioned whether known heading gene had a greater chance to be associated by haplotype, a combination of a set of SNPs within gene. We then extracted SNPs from the initiation codon to the termination codon of 11 genes: Hd17, Ghd7, Ehd1, RCN1, Hd1, Ghd8, Ghd7.1, DTH2, Hd3a, OsMADS50, and OsMADS56; haplotypes were then constructed. Most of these genes had more haplotypes in indica subpopulation than japonica subpopulation, with the exception for Ghd7.1 and OsMADS56 (Table 5). The associations were re-estimated at the haplotype level. The four heading date genes detected using GWAS at the SNP level were identified via haplotype association. Accordingly, Ghd7 was identified in the indica subpopulation under both SD and LD. However, RCN1 was detected in indica under SD, and Hd17 was detected in both subpopulations under LD. Ehd1 was detected in japonica under SD. Additionally, Ghd7.1, Hd3a, and OsMADS56 were detected via haplotype association (Supplementary Figure S1; Table 5). Ghd7.1 was identified in japonica subpopulation under both SD and LD. OsMADS56 was specifically identified under SD in japonica subpopulation. However, Hd3a was specifically identified in indica under LD.

Table 5.

Association analyses for known heading date genes in the indica and japonica subpopulations based on haplotypes using 425 accessions.

| Gene | N (Ind, Jap)∗ | Subpop | Wuhan |

Hainan |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P (2013) | P (2014) | P (2012) | P (2013) | |||

| Hd17 | 6 (6, 2) | Ind | 9.4E-06 | 2.6E-08 | ||

| Jap | 1.3E-08 | 1.5E-08 | ||||

| Hd3a | 6 (6, 2) | Ind | 1.8E-07 | 3.8E-09 | ||

| RCN1 | 3 (3, 1) | Ind | 2.6E-11 | 2.3E-08 | ||

| Ehd1 | 5 (3, 3) | Jap | 5.3E-16 | 2.0E-12 | ||

| OsMADS56 | 7 (3, 4) | Jap | 1.8E-09 | 6.3E-09 | ||

| Ghd7 | 6 (4, 2) | Ind | 1.5E-19 | 8.2E-17 | 3.1E-18 | 9.4E-10 |

| Ghd7.1 | 14 (5, 10) | Jap | 1.5E-11 | 5.9E-11 | 3.5E-21 | 1.9E-23 |

∗N was the number of haplotypes in 425 accessions. The numbers inside the parentheses are the numbers of haplotypes in the indica and japonica subpopulations, respectively. P is P-value in ANOVA.

Haplotype Analysis for Ghd7 and OsMADS56

Ghd7 is a key regulator of heading date and has five haplotypes with strong, weak or null-functions in cultivars (Xue et al., 2008; Lu et al., 2012). To obtain insight into why Ghd7 was not detected in japonica, we compared the haplotypes of Ghd7 in indica and japonica subpopulations (Table 6). In addition to the previously reported five haplotypes, one additional haplotype (Ghd7-4) was identified. In indica subpopulation, strong alleles of Ghd7-1 and Ghd7-3, weak allele of Ghd7-4 and non-functional allele of Ghd7-0 were observed, which caused a large variation in heading date and resulted in a successful detection. However, in japonica subpopulation, we only detected weak functional alleles of Ghd7-2 and non-functional alleles of Ghd7-0a, resulted a small variation and failed detection. The similar result was observed for OsMADS56 (Table 7). That is, indica rice carried haplotypes with similar genetic effects on heading date and japonica rice carried haplotypes with distinct genetic effects, these data explain why OsMADS56 was detected in only japonica subpopulation.

Table 6.

Comparison of heading date (days) among haplotypes of Ghd7 in indica and japonica subpopulations.

| Pop | Haplotypes | Number | Hainan 2012 | Hainan 2013 | Wuhan 2013 | Wuhan 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indica | Ghd7-1 | 161 | 98.7 ± 11.4C | 98.4 ± 7.7C | 101.4 ± 11.5C | 103.7 ± 11.7C |

| Ghd7-3 | 70 | 96.0 ± 10.1C | 96.6 ± 7.0C | 96.6 ± 6.8B | 97.4 ± 6.0B | |

| Ghd7-4 | 18 | 72.4 ± 12.4B | 86.4 ± 7.9B | 76.8 ± 10.9A | 82.5 ± 12.4A | |

| Ghd7-0 | 6 | 79.8 ± 16.6B | 88.1 ± 10.1B | 78.7 ± 11.2A | 82.6 ± 9.1A | |

| Japonica | Ghd7-2 | 136 | 87.2 ± 22.3b | 94.4 ± 12.2b | 97.3 ± 17.2b | 100.0 ± 17.4b |

| Ghd7-0a | 5 | 59.0 ± 5.1a | 79.9 ± 4.2a | 61.0 ± 5.7a | 68.2 ± 4.5a |

The phenotype values are represented as the means ± SD, letters are ranked via Duncan test at P < 0.01.

Table 7.

Comparison of heading date among haplotypes of OsMADS56 in indica and japonica subpopulations in Hainan.

| Pop | Haplotypes | Number | Hainan 2012 | Hainan 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indica | OsMADS56-1 | 59 | 97.5 ± 10.9A | 98.0 ± 7.8A |

| OsMADS56-2 | 145 | 93.3 ± 15.2A | 95.7 ± 9.0A | |

| OsMADS56-3 | 28 | 99.8 ± 11.1A | 99 ± 7.9A | |

| Japonica | OsMADS56-4 | 64 | 73.7 ± 18.5a | 87.9 ± 7.6a |

| OsMADS56-5 | 13 | 101.5 ± 20c | 101.5 ± 10.5c | |

| OsMADS56-6 | 32 | 92.7 ± 22.8b | 95.9 ± 13.5b | |

| OsMADS56-7 | 9 | 111.6 ± 8.1d | 108.4 ± 7.0d |

The phenotype values are represented as the means ± SD, letters are ranked via Duncan test at P < 0.01.

Discussion

Diverse Genetic Basis of Heading Date between Indica and Japonica Subpopulations

The large range in heading dates in the indica subpopulation was similar to that in the japonica subpopulation in each environment (Figure 1), which indicated a complicated genetic basis heading date in rice. However, no common QTLs were detected at the SNP level in two subpopulations (Tables 3 and 4). Under LD, Hd17 and Ghd7 were the primary heading genes in indica subpopulation; whereas qHd4, qHd6.2, and qHd7.2 were the primary players in japonica subpopulation. Under SD conditions, there were no genomic regions associated with heading date in japonica subpopulation, which indicated that the heading date genes in japonica had a photoperiod sensitivity that was too weak to efficiently function under SD conditions and led to a failed detection (Table 4). On contrary, a few QTLs were identified in indica subpopulation, which indicated that indica rice carried strong photoperiod-sensitive genes, which affected heading date even under SD. These results show that indica and japonica subpopulations have different gene/allele responses to day length.

The power of association mapping was greatly improved at the haplotype level; however, only one heading gene (Hd17) was commonly identified in both japonica and indica subpopulations under LD (Table 5). Moreover, the 7 associated known heading genes (with the exception of OsMADS56 and Ghd7.1) had more haplotypes in indica than japonica, which indicated that indica rice in regulating heading date was more genetically diverse than japonica. This result is in agreement with the previous finding that the genetic diversity in indica (0.0016) was much higher than that (0.0006) in japonica (Huang et al., 2010). There were 10 alleles of Ghd7.1 in japonica and five alleles in indica; however, only one allele was common across the two subpopulations. This finding was consistent with the reported assumption that indica and japonica alleles of Ghd7.1 evolved independently (Zhang et al., 2013). In most cases, japonica rice carries weak or non-functional alleles of photoperiod-sensitive genes, which enable it to be grown at high latitudes with LD during the rice-growing season. Indica rice carries diverse alleles, including strong, weak and non-functional alleles, which enable its growth across various climatic regions.

Different Heading Date Gene Responses to Long and Short Day Lengths

In this study, we detected QTLs for heading date using GWAS under SD (Hainan) and LD (Wuhan). At the SNP level, no common QTL was identified between SD and LD in japonica (Tables 3 and 4). In indica, only the known major gene Ghd7 was commonly detected under both conditions. For the 11 known heading date genes, seven were identified at the haplotype level. However, only Ghd7 in indica and Ghd7.1 in japonica were commonly detected under both conditions (Table 5). This indicated that Ghd7 and Ghd7.1 simultaneously contributed to the variation in heading date under both conditions, which is in agreement with the findings that Ghd7 and Ghd7.1 primarily function under LD, and they have weak effects under natural short day conditions (Xue et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2013). As we expected, Ehd1, a major heading date gene that primarily functions under SD conditions (Doi et al., 2004), was detected under SD conditions. Accordingly, the gene Hd17, which primarily functions under LD conditions (Matsubara et al., 2012), was detected under LD conditions. Hd3a, a rice florigen gene with expression that is repressed under LD and promoted under SD (Tamaki et al., 2007; Tsuji et al., 2011), was detected under LD in this study. This finding indicated that probably the upstream regulators act with Hd3a more actively under LD than SD. However, OsMADS56 and RCN1, two major heading date genes primarily working under LD (Nakagawa et al., 2002; Ryu et al., 2009), were detected under SD conditions. This inconsistency indicated that these genes likely have a new function, or association mapping is not sufficiently powerful so that some key genes are not detected. These unknown QTL detected under SD or LD may primarily regulate heading date dependent on short or long day length, respectively. Different QTL detected under SD and LD suggested that heading date genes have various photoperiod sensitivities. A parallel experimental design similar to this study is suggested for identifying and characterizing the genes with responses to environmental factors such as temperature or fertilizers. No heading date genes have been reported around the major QTL qHd3 in indica under SD and qHd4 in japonica under LD. They are likely new heading date genes. Populations designed for mapping both QTL are encouraged to confirm their identities.

Haplotype-Level Association Analysis Improved the Power of Mapping

In rice, several papers reported GWAS for important agronomic or biological traits at the SNP level. However, at least some or even a large portion of known functional genes was not identified (Zhao et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2012). The most likely reason for this is that in the most cases, SNP classification divided the collection into only two classes, whereas a gene has multiple alleles exhibiting different genetic effects in a natural population. Therefore, an SNP-derived low-resolution classification confused functional and non-functional alleles that were distinguished in multiple SNP combinations and compromised the real differences between alleles, thereby producing a failed detection. A haplotype is the genetic constitution of one locus/gene, which is specified by a minimum number of SNPs. At the single gene level, a haplotype is equal to an allele. In consequence, a haplotype-level GWAS is expected to mine more genes hidden in the whole genome because a haplotype-level GWAS shows the difference between haplotypes rather than conflating these differences.

Notably, most genes excluding housekeeping genes include several haplotypes/alleles, such as Ghd7 and OsMADS56, in the germplasm collection (Tables 6 and 7). Only four known heading genes (Ehd1, Hd17, RCN1, and Ghd7) were identified at the SNP level. However, for the 11 known genes, seven (including the four detected via SNP-level GWAS (SGWAS)) were identified via haplotype-level association analysis (Supplementary Figure S1; Table 5). Moreover, the order of magnitudes of the P-values for these four genes was greatly decreased comparing with SGWAS (Tables 3–5). Obviously, haplotype-level association analysis immensely increased the mapping power. In this study, we choose only 11 known genes as candidates to test the haplotype-level association analysis. Moreover, haplotype analysis ranked the genetic effects of haplotypes, which provided favorable haplotypes for breeding design. However, a haplotype-level genome-wide association study (HGWAS) faces substantial challenges because several points should be considered when constructing genome-wide haplotypes. (i) The haplotype specification should be made per gene unit or coding sequence of one gene that potentially matches a phenotypic variation, (ii) The species has a high-quality reference genome sequence for SNP screening and high-quality full-length cDNA sequences to delimit the gene region, (iii) The minimum deep sequencing and high-quality sequencing data are required for the identification of haplotypes by decreasing imputations of the missing and heterozygous sites and alleviating the calculation burden. The association mapping methods should also be further developed for HGWAS.

Conclusion

GWAS revealed that diverse genes/QTLs between indica and japonica subpopulations regulated heading date under SD and LD. Test of haplotype-level association mapping for 11 known heading date genes confirmed that the power of association mapping was greatly improved as compared to SNP-level association mapping and HGWAS approach is encouraged to develop in rice.

Author Contributions

ZH performed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the paper. BZ performed the experiments, HZ analyzed data, and MA wrote the paper. YX conceived the project, designed the research, and wrote the paper.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the field technician Mr. Jianbo Wang for his excellent work in the experimental field.

Funding. This work was supported by grants from the National Special Program for Research of Transgenic Plant of China (2011ZX08009-001-002), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (91335201).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2016.01270

Physic map of associated QTLs and candidate genes via SNP-level GWAS (SGWAS) and haplotype-level GWAS (HGWAS). The black QTLs are detected by SGWAS. The red heading date genes are detected by HGWAS. The blue heading date genes are detected by both SGWAS and HGWAS. The purples on the left side of each chromosome are heading date genes are failed in detection by GWAS.

References

- Chang T. T., Li C. C., Vergara B. S. (1969). Component analysis of duration from seeding to heading in rice by the basic vegetative phase and the photoperiod-sensitive phase. Euphytica 18 79–91. 10.1007/BF00021985 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Gao Y., Xie W., Gong L., Lu K., Wang W., et al. (2014). Genome-wide association analyses provide genetic and biochemical insights into natural variation in rice metabolism. Nat. Genet. 46 714–721. 10.1038/ng.3007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi K., Izawa T., Fuse T., Yamanouchi U., Kubo T., Shimatani Z., et al. (2004). Ehd1, a B-type response regulator in rice, confers short-day promotion of flowering and controls FT-like gene expression independently of Hd1. Genes Dev. 18 926–936. 10.1101/gad.1189604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H., Zheng X. M., Fei G. L., Chen J., Jin M. N., Ren Y. L., et al. (2013). Ehd4 encodes a novel and Oryza-genus-specific regulator of photoperiodic flowering in rice. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003281 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori K., Ogiso-Tanaka E., Matsubara K., Yamanouchi U., Ebana K., Yano M. (2013). Hd16, a gene for casein kinase i, is involved in the control of rice flowering time by modulating the day-length response. Plant J. 76 36–46. 10.1111/tpj.12268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Wei X., Sang T., Zhao Q., Feng Q., Zhao Y., et al. (2010). Genome-wide association studies of 14 agronomic traits in rice landraces. Nat. Genet. 42 961–967. 10.1038/ng.695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Zhao Y., Wei X., Li C., Wang A., Zhao Q., et al. (2012). Genome-wide association study of flowering time and grain yield traits in a worldwide collection of rice germplasm. Nat. Genet. 44 32–39. 10.1038/ng.1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh H., Nonoue Y., Yano M., Izawa T. (2010). A pair of floral regulators sets critical day length for Hd3a florigen expression in rice. Nat. Genet. 42 635–638. 10.1038/ng.606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khush G. S. (1997). “Origin, dispersal, cultivation and variation of rice,” in Oryza: From Molecule to Plant, eds Sasaki T., Moore G. (Berlin: Springer; ), 25–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Kim J., Han J. J., Han M. J., An G. (2004). Functional analyses of the flowering time gene OsMADS50, the putative suppressor of overexpression of co 1/AGAMOUS-like 20 (SOC1/AGL20) ortholog in rice. Plant J. 38 754–764. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02082.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M. X., Yeung J. M., Cherny S. S., Sham P. C. (2012). Evaluating the effective numbers of independent tests and significant p-value thresholds in commercial genotyping arrays and public imputation reference datasets. Hum. Genet. 131 747–756. 10.1007/s00439-011-1118-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippert C., Listgarten J., Liu Y., Kadie C. M., Davidson R. I., Heckerman D. (2011). FaST linear mixed models for genome-wide association studies. Nat. Methods 8 833–835. 10.1038/nmeth.1681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T., Liu H., Zhang H., Xing Y. (2013). Validation and characterization of Ghd7. 1, a major quantitative trait locus with pleiotropic effects on spikelets per panicle, plant height, and heading date in rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Integr. Plant Biol. 55 917–927. 10.1111/jipb.12070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L., Yan W., Xue W., Shao D., Xing Y. (2012). Evolution and association analysis of Ghd7 in rice. PLoS ONE 7:e34021 10.1371/journal.pone.0034021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara K., Ogiso-Tanaka E., Hori K., Ebana K., Ando T., Yano M. (2012). Natural variation in Hd17 a homolog of Arabidopsis ELF3 that is involved in rice photoperiodic flowering. Plant Cell Physiol. 53 709–716. 10.1093/pcp/pcs028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara K., Yamanouchi U., Nonoue Y., Sugimoto K., Wang Z. X., Minobe Y., et al. (2011). Ehd3, encoding a plant homeodomain finger-containing protein, is a critical promoter of rice flowering. Plant J. 66 603–612. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04517.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara K., Yamanouchi U., Wang Z. X., Minobe Y., Izawa T., Yano M. (2008). Ehd2, a rice ortholog of the maize INDETERMINATE1 gene, promotes flowering by up-regulating Ehd1. Plant Physiol. 148 1425–1435. 10.1104/pp.108.125542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa M., Shimamoto K., Kyozuka J. (2002). Overexpression of RCN1 and RCN2, rice TERMINAL FLOWER 1/CENTRORADIALIS homologs, confers delay of phase transition and altered panicle morphology in rice. Plant J. 29 743–750. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01255.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu C. H., Lee S., CHO L. H., Kim S. L., LEE Y. S., Choi S. C., et al. (2009). OsMADS50 and OsMADS56 function antagonistically in regulating long day (LD)-dependent flowering in rice. Plant Cell Environ. 32 1412–1427. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02008.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens M., Smith N. J., Donnelly P. (2001). A new statistical method for haplotype reconstruction from population data. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 68 978–989. 10.1086/319501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y., Shomura A., Sasaki T., Yano M. (2001). Hd6, a rice quantitative trait locus involved in photoperiod sensitivity, encodes the α subunit of protein kinase CK2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 7922–7927. 10.1073/pnas.111136798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaki S., Matsuo S., Wong H. L., Yokoi S., Shimamoto K. (2007). Hd3a protein is a mobile flowering signal in rice. Science 316 1033–1036. 10.1126/science.1141753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji H., Taoka K.-I., Shimamoto K. (2011). Regulation of flowering in rice: two florigen genes, a complex gene network, and natural variation. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 14 45–52. 10.1016/j.pbi.2010.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergara B., Tanaka A., Lilis R., Puranabhavung S. (1966). Relationship between growth duration and grain yield of rice plants. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 12 31–39. 10.1080/00380768.1966.10431180 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Xie W., Xing H., Yan J., Meng X., Li X., et al. (2015). Genetic architecture of natural variation in rice chlorophyll content revealed by a genome-wide association study. Mol. Plant 8 946–957. 10.1016/j.molp.2015.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X., Xu J., Guo H., Jiang L., Chen S., Yu C., et al. (2010). DTH8 suppresses flowering in rice, influencing plant height and yield potential simultaneously. Plant Physiol. 153 1747–1758. 10.1104/pp.110.156943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W., Zheng X. M., Lu G., Zhong Z., Gao H., Chen L., et al. (2013). Association of functional nucleotide polymorphisms at DTH2 with the northward expansion of rice cultivation in Asia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 2775–2780. 10.1073/pnas.1213962110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue W., Xing Y., Weng X., Zhao Y., Tang W., Wang L., et al. (2008). Natural variation in Ghd7 is an important regulator of heading date and yield potential in rice. Nat. Genet. 40 761–767. 10.1038/ng.143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano M., Katayose Y., Ashikari M., Yamanouchi U., Monna L., Fuse T., et al. (2000). Hd1, a major photoperiod sensitivity quantitative trait locus in rice, is closely related to the Arabidopsis flowering time gene CONSTANS. Plant Cell 12 2473–2483. 10.2307/3871242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. -C., Yu Y., Wang C. -Y., Li Z. -Y., Liu Q., Xu J., et al. (2013). Overexpression of microRNA OsmiR397 improves rice yield by increasing grain size and promoting panicle branching. Nat. Biotechnol. 31 848–852. 10.1038/nbt.2646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao K., Tung C. -W., Eizenga G. C., Wright M. H., Ali M. L., Price A. H., et al. (2011). Genome-wide association mapping reveals a rich genetic architecture of complex traits in Oryza sativa. Nat. commun. 2 467 10.1038/ncomms1467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Physic map of associated QTLs and candidate genes via SNP-level GWAS (SGWAS) and haplotype-level GWAS (HGWAS). The black QTLs are detected by SGWAS. The red heading date genes are detected by HGWAS. The blue heading date genes are detected by both SGWAS and HGWAS. The purples on the left side of each chromosome are heading date genes are failed in detection by GWAS.