Abstract

Background

The standard of care for elderly women with breast cancer remains controversial. The aim of this study was to clarify the management of elderly breast cancer patients who undergo surgery.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective single-center cohort study included 2276 breast cancer patients who underwent surgery between 1993 and 2014. The patients were divided into three groups according to age: ≤64 (young), 65–74 (older), and ≥75 (elderly).

Results

The elderly had more advanced stage disease at diagnosis (stage III and IV, 16.2%, 17.5%, and 22.1% for the young, older, and elderly groups, respectively). The elderly were more likely to undergo mastectomy (43.3%, 41.4%, and 50.7%, respectively), omit axillary operation (0.6%, 1.1%, and 9.3%, respectively), and skip radiotherapy after breast conserving surgery (93.1%, 86.8%, and 29.1%, respectively). Endocrine therapy was widely used in all groups (94.4%, 93.8%, and 90.1%, respectively), but frequency of chemotherapy was lower in the elderly regardless of HR status (40.8%, 25.5%, and 9.3% in HR(+), 87.2%, 75.3%, and 39.5% in HR(−), respectively). Although the loco-regional recurrence rate was higher in the elderly (4.2%, 3.4%, and 7.0% at 5 years, respectively; P = 0.028), there were no differences among groups in distant metastasis free survival or breast cancer specific survival.

Conclusion

Although elderly patients had more advanced stages of cancer and received less treatment, there were no differences in survival. Omission of axillary dissection, radiation and chemotherapy after operation may be an option for breast cancer patients ≥75 years.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Elderly, Surgery, Radiotherapy, Systemic therapy, Prognosis

1. Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common malignant disease among women in the world. The incidence has been increasing substantially in Japan and other Asian countries over the past three decades, and it has a high incidence in the United States and Europe [1–3]. In Asia including Japan, breast cancer incidence peaks among women in their forties whereas it peaks among women in their sixties in the United States and Europe [1, 4]. Despite the difference in median age at diagnosis, the number of breast cancer patients is increasing in Japan due to a rapid increase in the number of elderly individuals. The population that is over 65 years old accounted for 9.1% of the total in 1980, 19.9% in 2005, and it is estimated to reach 31.8% by the year 2030 [5, 6].

Although the number of elderly patients with breast cancer is increasing, knowledge about the possible differences in the biology and clinical outcomes of elderly cases of breast cancer that should reflect management according to age remains limited. Currently, treatment for elderly women with breast cancer is largely extrapolated from data derived from trials that enrolled younger patients; thus, the standard of care for elderly breast cancer patients is far from being established [7]. Several reports demonstrated that elderly breast cancer patients are less likely to undergo surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy [8–11]. Although studies consistently show that older women are undertreated for breast cancer, the impact of under-treatment on breast cancer survival among older women remains controversial [10]. Furthermore, little has been reported on the management of elderly breast cancer patients in Asian countries.

The aim of this study was to clarify the management of elderly breast cancer patients who underwent surgery and to investigate any effect of management choice on their outcomes.

2. Patients and Methods

The study included 2276 patients with breast cancer referred for surgery at Yokohama City University Medical Center between May 1993 and June 2014. Data on patient medical history, histopathological factors of the breast cancers, and management including surgery, radiation, and systemic treatment (hormonal therapy or chemotherapy) were recorded. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yokohama City University, Kanagawa, Japan.

Estrogen receptor (ER) level, progesterone receptor level, human epidermal growth factor 2 (HER2) status, and Ki-67 labeling index were evaluated pathologically using the invasive component of the tumor. Hormonal receptor status was evaluated via immunohistochemistry as described previously [12–14]. HER2 testing was performed via immunohistochemistry and/or in situ hybridization as previously reported [15]. The Ki-67 labeling index was evaluated in the highest immunoreactivity fields and was recorded as 0–100% as recommended [16].

We defined the nomenclature of the operations as the following: mastectomy (including radical, modified radical, or simple mastectomy), breast-conserving surgery (BCS, including lumpectomy, segmental resection, wide resection, quadrantectomy, or partial mastectomy), or immediate reconstructive surgery with skin (and nipple) sparing mastectomy. For axillary lymph nodes, sentinel lymph node biopsy using dye and/or radioisotope methods, and/or complete axillary lymph node dissection was performed [17].

The patients who underwent BCS were recommended to receive adjuvant radiation therapy to the remaining breast tissue [18]. The patients with pT3-T4 tumors and/or ≥4 positive axillary nodes were recommended to receive radiation therapy according to clinical practice guidelines [17, 19–22].

For patients with invasive ductal carcinoma, adjuvant systemic therapy was administered according to the estimated risk of recurrence. The adjuvant chemotherapy regimens included anthracycline-based regimens such as AC (doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide), CAF (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and 5-fluorouracil [5FU]), CEF (cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, and 5FU), taxane-containing regimens such as TC (docetaxel and cyclophosphamide), docetaxel/3w or paclitaxel/w; CMF (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5FU); and oral 5FU alone. Endocrine treatments were mainly selective estrogen receptor modulators, such as tamoxifen and toremifene, or aromatase inhibitors such as anastrozole, exemestane, and letrozole.

The statistical analysis was conducted using the SPSS 22.0 for Windows software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Correlations among the clinicopathologic parameters and age groups were evaluated via Tukey-type multiple comparison analyses with the χ2 and Mantel test. Patient outcomes were assessed in terms of disease-free survival. Survival distributions were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Differences were compared using the log-rank test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1 Pathological characteristics by age group

Of the 2,276 women in our study population, 1,632 (71.7%) were below 64 years old (young), 400 (17.6%) were between 65 and 74 (older), and 244 (10.7%) were over 75 years old (elderly). The patients’ characteristics are shown in Table 1. The elderly patients had larger and more advanced tumors, but no significant difference was observed among groups in terms of lymph node involvement. Because of the increased frequency of larger tumors, the elderly patients had significantly advanced stage disease at diagnosis (stage III and IV, 16.2%, 17.5%, and 22.1%, for the young, old, and elderly groups, respectively; P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Pathological characteristics by age group

| Age group | ≤64 | (%) | 65–74 | (%) | ≥75 | (%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n= | 1632 | (71,7) | 400 | (17.6) | 244 | (10.7) | ||

| pT | ||||||||

| pTX | 1 | (0.1) | 1 | (0.2) | 0 | (0.0) | ||

| pTis | 225 | (13.8) | 29 | (7.3) | 18 | (7.4) | <0.001 | |

| pT1 | 670 | (41.0) | 172 | (43.0) | 85 | (34.8) | ||

| pT2 | 555 | (34.0) | 156 | (39.0) | 107 | (43.8) | ||

| pT3 | 105 | (6.4) | 13 | (3.2) | 8 | (3.3) | ||

| pT4 | 76 | (4.7) | 29 | (7.3) | 26 | (10.7) | ||

| pN | ||||||||

| pNX | 9 | (0.5) | 4 | (1.0) | 21 | (8.6) | ||

| pN0 | 1158 | (71.0) | 280 | (70.0) | 150 | (61.5) | 0.529 | |

| pN1 | 325 | (19.9) | 78 | (19.5) | 41 | (16.8) | ||

| pN2 | 89 | (5.5) | 24 | (6.0) | 20 | (8.2) | ||

| pN3 | 51 | (3.1) | 14 | (3.5) | 12 | (4.9) | ||

| UICC TNM Stage | ||||||||

| 0 | 225 | (13.8) | 29 | (7.3) | 18 | (7.4) | <0.001 | |

| I | 541 | (33.2) | 141 | (35.2) | 72 | (29.5) | ||

| II | 601 | (36.8) | 160 | (40.0) | 100 | (41.0) | ||

| III | 234 | (14.3) | 58 | (14.5) | 46 | (18.8) | ||

| IV | 31 | (1.9) | 12 | (3.0) | 8 | (3.3) | ||

| Estrogen receptor | ||||||||

| Positive | 1083 | (77.0) | 275 | (74.1) | 174 | (77.0) | 0.569 | |

| Negative | 310 | (22.0) | 84 | (22.6) | 48 | (21.2) | ||

| Unavailable | 16 | (1.0) | 12 | (3.3) | 4 | (1.8) | ||

| Progesterone receptor | ||||||||

| Positive | 954 | (67.8) | 222 | (59.8) | 153 | (67.7) | 0.060 | |

| Negative | 416 | (29.6) | 136 | (36.7) | 69 | (30.5) | ||

| Unavailable | 37 | (2.6) | 13 | (3.5) | 4 | (1.8) | ||

| HER2 | ||||||||

| Positive | 197 | (14.0) | 34 | (9.1) | 18 | (8.0) | 0.003 | |

| Negative | 992 | (70.5) | 274 | (73.9) | 155 | (68.6) | ||

| Unavailable | 220 | (15.5) | 64 | (17.0) | 53 | (23.4) | ||

| Subtype | ||||||||

| Luminal | 1005 | (71.4) | 263 | (70.9) | 169 | (74.8) | 0.067 | |

| Luminal-HER2 | 103 | (7.3) | 18 | (4.9) | 9 | (4.0) | ||

| HER2 | 94 | (6.7) | 16 | (4.3) | 9 | (4.0) | ||

| Triple negative | 192 | (13.7) | 62 | (16.7) | 34 | (15.0) | ||

| Unavailable | 13 | (0.9) | 12 | (3.2) | 5 | (2.2) | ||

| Grade | ||||||||

| 1 | 534 | (38.0) | 145 | (39.1) | 81 | (35.8) | 0.417 | |

| 2 | 164 | (11.7) | 54 | (14.6) | 32 | (14.2) | ||

| 3 | 240 | (17.0) | 54 | (14.6) | 47 | (20.8) | ||

| Unavailable | 469 | (33.3) | 118 | (31.7) | 66 | (29.2) | ||

| Histological type | ||||||||

| Ductal | 1253 | (89.0) | 320 | (86.2) | 181 | (80.0) | <0.001 | |

| Lobular | 67 | (4.8) | 15 | (4.0) | 16 | (7.1) | ||

| Mucinous | 37 | (2.6) | 16 | (4.3) | 17 | (7.5) | ||

| Medullary | 17 | (1.2) | 1 | (0.3) | 0 | (0.0) | ||

| Apocrine | 12 | (0.9) | 12 | (3.2) | 10 | (4.4) | ||

| Others | 21 | (1.5) | 7 | (2.0) | 2 | (1.0) | ||

There were no differences in estrogen-receptor positivity by age (77.0%, 74.1%, and 77.0%, respectively), but there were fewer patients aged 65–74 with progesterone receptor-positive tumors (67.8%, 59.8%, and 67.7%, respectively; P = 0.060) and fewer HER2 positive-tumors in patients aged ≥65 years (14.0%, 9.1%, and 8.0%, respectively; P = 0.003). Thus, there were more luminal and fewer HER2 subtypes among the older and elderly patients than among the young patients. Although there were no differences among groups in terms of histological grade, the elderly patients demonstrated fewer cases of invasive ductal carcinoma and more cases of invasive lobular carcinoma, mucinous carcinoma, and apocrine carcinoma.

3.2 Local treatments by age group

The elderly patients had more mastectomies (including skin-sparing mastectomy) (43.3%, 41.4%, and 50.7%, respectively; P < 0.001) and were more likely to omit axillary operation (0.6%, 1.1% and 9.3%; P < 0.001). Approximately 25% of young patients who received mastectomy underwent immediate reconstructive surgery, but only one older patient, aged 65 years received immediate reconstructive surgery. Physicians decide to perform breast surgery with local anesthesia if the patient has severe comorbidities. As a result, 8% of patients underwent breast surgery with local anesthesia and they did not receive axillary surgery. Elderly patients were less likely to receive radiotherapy (RT) after not only BCS (93.1%, 86.8%, and 29.1%, respectively; P < 0.001), but also after mastectomy (20.6%, 12.5%, and 10.1%, respectively; P < 0.001) compared with their younger counterparts.

3.3 Systemic treatments by age group

Systemic treatments for invasive breast cancer by age group are shown in Table 3. Elderly patients were less likely to receive adjuvant systemic therapy (93.6%, 90.5%, and 78.0%, respectively; P < 0.001). This was particularly the case for adjuvant cytotoxic chemotherapy (50.0%, 36.0%, and 15.3%, respectively; P < 0001). However, more than 90% of patients with hormone receptor-positive (luminal) cancer, including elderly patients received adjuvant hormone therapy (94.4%, 93.8%, and 90.1%, respectively; P = 0.133).

Table 3.

Systemic treatments by age group.

| Age group | ≤64 | (%) | 65–74 | (%) | ≥75 | (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic therapy | |||||||

| 1268 | (93.6) | 324 | (90.5) | 170 | (78.0) | <0.001 | |

| Endocrine therapy for Luminal type | |||||||

| 1007 | (94.4) | 258 | (93.8) | 155 | (90.1) | 0.133 | |

| Chemotherapy | |||||||

| 667 | (50.0) | 125 | (36.0) | 33 | (15.3) | <0.001 | |

| Reason for omitting chemotherapy | |||||||

| Histopathological reason | 576 | (86.7) | 179 | (80.6) | 131 | (72.0) | <0.001 |

| Physicians’ decision | 88 | (13.3) | 43 | (19.4) | 51 | (28.0) | |

Percentage are calculated among available data

Chemotherapy regimens by subtype are shown in Table 4. The percentage of patients who received chemotherapy decreased as age increased regardless of hormonal receptor status. Among the patients ≤74 years old, less than half of the patients with the luminal subtype received chemotherapy (≤64: 40.8%, 65–74: 25.5%), while most of non-luminal subtype received it (≤64: 87.2%, 65–74: 75.3%). Among the elderly patients, 9.3% with luminal and 39.5% with non-luminal subtypes received chemotherapy. Furthermore, most of the patients ≤ 74 years old received anthracycline and/or taxane-containing regimens, whereas the elderly patients tended to receive oral 5FU or CMF regimens, which are less toxic.

Table 4.

Regimen of chemotherapy by subtype

| Age group | ≤64 | (%) | 65–74 | (%) | ≥75 | (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For luminal | 435 | (40.8) | 70 | (25.5) | 16 | (9.3) | <0.001 |

| A and/or T | 402 | (92.4) | 60 | (85.7) | 8 | (50.0) | |

| others | 33 | (7.6) | 10 | (14.3) | 8 | (50.0) | |

| For non-luminal | 232 | (87.2) | 55 | (75.3) | 17 | (39.5) | <0.001 |

| A and/or T | 186 | (80.2) | 46 | (83.6) | 5 | (29.9) | |

| others | 56 | (24.1) | 9 | (16.4) | 12 | (70.1) | |

| For HER2 | |||||||

| TRA | 112 | (87.5) | 21 | (80.7) | 5 | (31.3) | <0.001 |

Percentage are calculated among patients who received chemotherapy.

A: anthracycline, T: taxane, TRA: trastuzumab, others contain oral 5FUs and CMF

After 2008, trastuzumab along with chemotherapeutic agents was administered to patients with HER2 positive breast cancer as adjuvant therapy. More than 80% of the patients aged ≤74 years received it, but approximately 30% of elderly patients received it.

The primary reason for omitting cytotoxic chemotherapy was that it was unnecessary according to the histopathological findings. Omitting chemotherapy was more often a patients’ preference among younger patients but was more often as physicians’ decision for elderly patients (13.3%, 19.4% and 28.0%, respectively).

3.4. Disease-free survival by age group

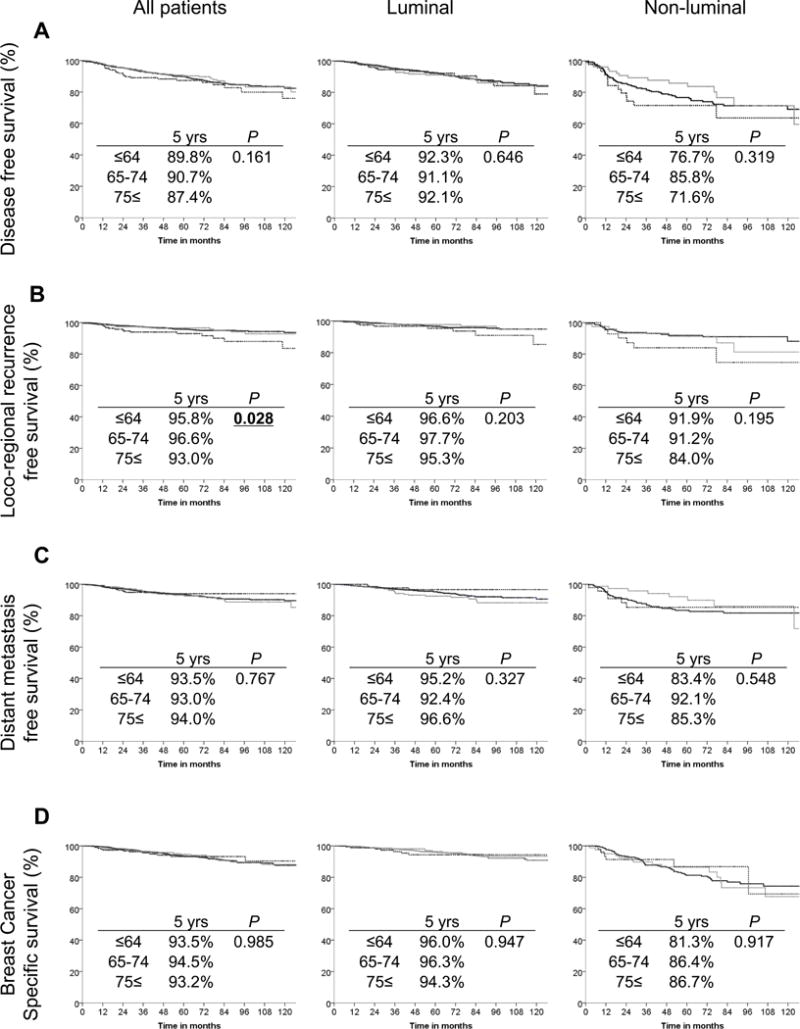

Overall, median follow-up time was 4.8 years. Fig. 1A shows disease free survival (DFS) curves by age. Almost 90% of the patients in each group were disease free at 5 years and there was no significant difference by age (89.8%. 90.7%, and 87.4%, respectively). Age did not affect DFS among patients with luminal types (92.3%, 91.1%. and 92.1%, respectively), while non-luminal elderly patients tended to have worse DFS compared to their younger counterparts, and patients 65 to 74 years old tended to have better outcomes compared with young non-luminal patients (76.7%, 85.8%, and 71.6%, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Prognostic analysis by age group. A: Disease-free survival curve. B: Loco-regional recurrence free survival curve. C: Distant metastasis free survival curve. D: Breast cancer specific survival curve. Black lines represent the patients below 64 years old, gray lines represent the patients between 65 and 74 years old, and the black dotted line represent the patients over 75 years old.

The elderly patients had significantly higher rates of local recurrence (4.2%, 3.4%, and 7.0%, respectively), and this trend was the same for both luminal and non-luminal patients (Fig. 1B). On the other hand, age did not affect distant metastasis (6.5%, 7.0%, and 6.0%, respectively, Fig. 1C). Patients aged 65 to 74 years with non-luminal tumors tended to have fewer distant metastases (16.6%, 7.9%, and 14.7%, respectively). However, breast cancer specific 5-year survival showed no significant difference by age (93.5%, 94.5%, and 93.2%, respectively), regardless of hormone receptor status (Fig. 1D).

Discussion

The elderly patients (over 75 year old) in our cohort had more advanced disease (stage III and IV), which is consistent with other studies [8, 23]. This is partially explained by the delay in diagnosis because fewer elderly patients undergo screening mammograms [24]. Wan et al. reported that the distribution of breast cancer subtypes varies by race/ethnicity, and subtype plays an important role in the biology of breast cancer [25]. Breast cancers arising in elderly women have less ER expression among Caucasian and European populations, while no difference by age has been observed in the Japanese population, including our cohort [5, 8]. The expression of HER2 is low among elderly patients regardless of race. Although histological grade was not associated with age, elderly patients had more cases of various histological types that have a better prognosis, such as mucinous carcinoma or apocrine carcinoma. These characteristics imply a more favorable biology for elderly breast cancer than that of younger patients, which is in agreement with other reports [26–29].

Mastectomy was performed more frequently, and axillary dissection and radiation were performed less frequently, among older patients, consistent with other reports [10]. One fourth of young patients who underwent mastectomy received immediate reconstruction while only one older patient received it. The high rate of mastectomy can be explained by the fact that elderly patients have more advanced stage breast cancer. On the other hand, mastectomy does spare elderly patients from adjuvant radiation.

Although axillary operation, particularly sentinel lymph node biopsy for staging purposes, was performed less frequently in elderly patients in our cohort, it was still more frequent compared to other reports, which may or may not be affected by the longer life expectancy of Japanese women than in other countries [9, 10]. Most of the patients over 65 years old who omitted axillary surgery did so because they received local anesthesia due to their comorbidities, while most of the younger patients who did not receive axillary surgery did so because they refused to undergo it.

Most of the patients under 74 years old who underwent BCS received adjuvant radiation. Although approximately 50% of the elderly patients underwent BCS, more than 70% of those who did omitted radiation. Hancke et al. reported that the frequency of non-adherence to guidelines for adjuvant radiation increased exponentially with advancing age and the omission of radiotherapy had the greatest impact on overall survival and DFS in the elderly population [30]. Others reported that radiation after BCS reduces breast cancer recurrence among older women with early-stage disease but does not affect survival [31–33]. Interestingly, fewer elderly patients in our cohort received radiation, which may be responsible for the significantly higher local recurrence rate compared to younger patients. However, given the fact that there was no difference in breast cancer specific survival, we agree with the notion that omission of adjuvant radiation for elderly patients is an acceptable option.

According to the St. Gallen consensus, hormonal therapy is recommended for luminal subtype breast cancer [17]. Our study showed that hormonal therapy is widely used for all ages. On the other hand, the indications for use of adjuvant chemotherapy for luminal disease remains unclear [17]. Approximately 40% of patients with luminal disease under 65 years old in our cohort received chemotherapy and the percentage decreased with increases in age. However, distant metastasis free survival (DMFS) and breast cancer specific survival (BCSS) were no different among groups.

As has been described in the St. Gallen consensus report, effective systemic therapy decreases not only the rate of distant metastases but also loco-regional recurrence [17]. Our study indicates that hormonal therapy has more impact on survival than chemotherapy for elderly patients with luminal type breast cancer. For non-luminal disease, almost 90% of patients aged ≤64 years received chemotherapy, compared to 77% of patients who were 65–74 years old, and 39.5% of elderly patients. Furthermore, most of the patients under age 74 received anthracycline and/or a taxane regimen while most of the elderly patients received an oral 5FU or CMF regimen, which is thought to be less efficacious but was chosen due to lesser toxicity. However, in our cohort, DMFS and BCSS in non-luminal types were no different by age despite the fact that elderly patients received less efficacious chemotherapy. This is in agreement with most other studies that suggest omission of chemotherapy for the elderly patients [34, 35].

These findings led us to two speculations. First, the biology of breast cancer in elderly patients may be more favorable compared with cases in younger women. Second, even oral 5FU or CMF may be effective for elderly patients. Lowman et al. reported that breast cancer progresses less aggressively in elderly patients and thus the common intensive treatment approaches are not required. On the other hand, chemotherapy demonstrated a survival benefit for women aged 67 to 79 years with ER-negative, lymph node-positive disease [9, 36, 37]. The authors of these studies suggested that age alone should not be a contraindication for chemotherapy since older women had similar reductions in survival and recurrence as younger patients. Furthermore, triple negative breast cancer of elderly patients is an aggressive breast cancer subtype claiming as much attention as in younger patients, thus warranting chemotherapeutic intervention irrespective of age [38]. For non-luminal breast cancer patients, oral 5FU or CMF may be considered as one of the choices for elderly patients [39, 40]. The optional adjuvant chemotherapy regimen for elderly patients remains unclear and further research is warranted.

Finally, several limitations of this study should be taken in account. Since this is a retrospective observational study with a small number of patients, there is undoubtedly selection bias and residual confounding by factors for which we do not have data, such as performance status and comorbidities. Most physicians take comorbid conditions into account when choosing treatment strategies, particularly in elderly patients where they occur more frequently. Whether these comorbidities influence the biology of breast cancer leading to recurrence or survival remains unknown [30]. Since elderly patients have much more variety in their comorbid conditions, organ functions, cognitive function, performance status, and social background than young patients, it is difficult to conduct clinical trials, and many times decisions about management need to be made on a case-by-case basis.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study showed that local and systemic therapy were administered less frequency to elderly patients, aged ≥75 years old, than younger patients. Loco-regional recurrence-free survival was worse in elderly patients, but survival was not affected. The findings of this observational study could represent the outcomes of different management choices in the elderly population. We need to consider the variety of elderly patients’ characteristics when developing guidelines for personalized management that is necessary for elderly breast cancer patients.

Table 2.

Local treatments by age group

| Age group | ≤64 | (%) | 65–74 | (%) | ≥75 | (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast surgery | |||||||

| none | 1 | (0.1) | 1 | (0.3) | 0 | (0.0) | <0.001 |

| BCS | 805 | (56.6) | 217 | (58.3) | 112 | (49.3) | |

| Mastectomy | 617 | (43.3) | 154 | (41.4) | 115 | (50.7) | |

| with reconstruction | 160/617 | 1/154 | 0/115 | ||||

| Under local anesthesia | 2 | (0.1) | 3 | (0.8) | 20 | (8.2) | <0.001 |

| Axillary surgery | |||||||

| none | 9 | (0.6) | 4 | (1.1) | 21 | (9.3) | <0.001 |

| SNB | 686 | (48.2) | 188 | (50.5) | 106 | (46.7) | |

| SNB-Ax | 121 | (8.5) | 31 | (8.3) | 15 | (6.6) | |

| Ax | 607 | (42.7) | 149 | (40.1) | 85 | (37.4) | |

| Radiotherapy | |||||||

| for BCS | 722 | (93.1) | 184 | (86.8) | 32 | (29.1) | <0.001 |

| for Mastectomy | 117 | (20.6) | 18 | (12.5) | 11 | (10.1) | <0.001 |

BCS: breast conserving surgery, SNB: sentinel lymph node biopsy, Ax: axillary dissection

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Shoko Adachi, Dr. Fumi Harada, Dr. Hidetaka Shima, Dr. Kumiko Kida, Dr. Shinya Yamamoto, and Dr. Kazuhiro Shimada for collecting clinicopathological data. We thank Dr. Mikiko Tanabe for pathological opinions. KT is supported by NIH/NCI grant R01CA160688 and Susan G. Komen Investigator Initiated Research Grant IIR12222224.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure

The authors report no proprietary or commercial interest in any product or concept discussed in this article.

Author contributions

A.Y., K.N., S.S., and D.S. conceptualized and collected data described in the article. A.Y., K.T., and T.I. prepared and revised the article. Y.I. and I.E. provided supervision of study and preparation of the article. Each of the authors gave final approval for this article.

References

- 1.Leong SP, Shen ZZ, Liu TJ, Agarwal G, Tajima T, et al. Is breast cancer the same disease in Asian and Western countries? World J Surg. 2010;34:2308. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0683-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeSantis C, Ma J, Bryan L, Jemal A. Breast cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:52. doi: 10.3322/caac.21203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohuchi N, Suzuki A, Sobue T, Kawai M, Yamamoto S, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of mammography and adjunctive ultrasonography to screen for breast cancer in the Japan Strategic Anti-cancer Randomized Trial (J-START): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:341. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00774-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsuchida J, Nagahashi M, Rashid OM, Takabe K, Wakai T. At what age should screening mammography be recommended for Asian women? Cancer Med. 2015;4:1136. doi: 10.1002/cam4.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Japanese National Cancer Center. Center for Cancer Control and Information Services. 2015 http://gdb.ganjoho.jp/graph_db/gdb1?smTypes=14.

- 6.Japanese Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. 2015 http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/dl/81-1a2.pdf.

- 7.Talarico L, Chen G, Pazdur R. Enrollment of elderly patients in clinical trials for cancer drug registration: a 7-year experience by the US Food and Drug Administration. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4626. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gennari R, Curigliano G, Rotmensz N, Robertson C, Colleoni M, et al. Breast carcinoma in elderly women: features of disease presentation, choice of local and systemic treatments compared with younger postmenopausal patients. Cancer. 2004;101:1302. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elkin EB, Hurria A, Mitra N, Schrag D, Panageas KS. Adjuvant chemotherapy and survival in older women with hormone receptor-negative breast cancer: assessing outcome in a population-based, observational cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2757. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schonberg MA, Marcantonio ER, Li D, Silliman RA, Ngo L, et al. Breast cancer among the oldest old: tumor characteristics, treatment choices, and survival. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2038. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Syed BM, Green AR, Paish EC, Soria D, Garibaldi J, et al. Biology of primary breast cancer in older women treated by surgery: with correlation with long-term clinical outcome and comparison with their younger counterparts. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:1042. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allred DC, Harvey JM, Berardo M, Clark GM. Prognostic and predictive factors in breast cancer by immunohistochemical analysis. Mod Pathol. 1998;11:155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leake R, Barnes D, Pinder S, Ellis I, Anderson L, et al. Immunohistochemical detection of steroid receptors in breast cancer: a working protocol. UK Receptor Group, UK NEQAS, The Scottish Breast Cancer Pathology Group, and The Receptor and Biomarker Study Group of the EORTC. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:634. doi: 10.1136/jcp.53.8.634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammond ME, Hayes DF, Dowsett M, Allred DC, Hagerty KL, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer (unabridged version) Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:e48. doi: 10.5858/134.7.e48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Hicks DG, Dowsett M, McShane LM, et al. Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3997. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.9984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dowsett M, Nielsen TO, A’Hern R, Bartlett J, Coombes RC, et al. Assessment of Ki67 in breast cancer: recommendations from the International Ki67 in Breast Cancer working group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1656. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldhirsch A, Winer EP, Coates AS, Gelber RD, Piccart-Gebhart M, et al. Personalizing the treatment of women with early breast cancer: highlights of the St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2013. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2206. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fisher B, Redmond C, Poisson R, Margolese R, Wolmark N, et al. Eight-year results of a randomized clinical trial comparing total mastectomy and lumpectomy with or without irradiation in the treatment of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:822. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198903303201302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Recht A, Edge SB, Solin LJ, Robinson DS, Estabrook A, et al. Postmastectomy radiotherapy: clinical practice guidelines of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1539. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.5.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor ME, Haffty BG, Rabinovitch R, Arthur DW, Halberg FE, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria on postmastectomy radiotherapy expert panel on radiation oncology-breast. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:997. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.10.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Truong PT, Olivotto IA, Whelan TJ, Levine M. Clinical practice guidelines for the care and treatment of breast cancer: 16. Locoregional post-mastectomy radiotherapy. CMAJ. 2004;170:1263. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sautter-Bihl ML, Souchon R, Budach W, Sedlmayer F, Feyer P, et al. DEGRO practical guidelines for radiotherapy of breast cancer II. Postmastectomy radiotherapy, irradiation of regional lymphatics, and treatment of locally advanced disease. Strahlenther Onkol. 2008;184:347. doi: 10.1007/s00066-008-1901-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Louwman WJ, Vulto JC, Verhoeven RH, Nieuwenhuijzen GA, Coebergh JW, et al. Clinical epidemiology of breast cancer in the elderly. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:2242. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zapka JG, Stoddard AM, Costanza ME, Greene HL. Breast cancer screening by mammography: utilization and associated factors. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:1499. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.11.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wan D, Villa D, Woods R, Yerushalmi R, Gelmon K. Breast Cancer Subtype Variation by Race and Ethnicity in a Diverse Population in British Columbia. Clin Breast Cancer. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaefer G, Rosen PP, Lesser ML, Kinne DW, Beattie EJ., Jr Breast carcinoma in elderly women: pathology, prognosis, and survival. Pathol Annu. 1984;19(Pt 1):195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clark GM. The biology of breast cancer in older women. J Gerontol. 1992;47(Spec No):19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonnier P, Romain S, Charpin C, Lejeune C, Tubiana N, et al. Age as a prognostic factor in breast cancer: relationship to pathologic and biologic features. Int J Cancer. 1995;62:138. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910620205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diab SG, Elledge RM, Clark GM. Tumor characteristics and clinical outcome of elderly women with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:550. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.7.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hancke K, Denkinger MD, Konig J, Kurzeder C, Wockel A, et al. Standard treatment of female patients with breast cancer decreases substantially for women aged 70 years and older: a German clinical cohort study. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:748. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fyles AW, McCready DR, Manchul LA, Trudeau ME, Merante P, et al. Tamoxifen with or without breast irradiation in women 50 years of age or older with early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:963. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith BD, Gross CP, Smith GL, Galusha DH, Bekelman JE, et al. Effectiveness of radiation therapy for older women with early breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:681. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hughes KS, Schnaper LA, Bellon JR, Cirrincione CT, Berry DA, et al. Lumpectomy plus tamoxifen with or without irradiation in women age 70 years or older with early breast cancer: long-term follow-up of CALGB 9343. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2382. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bouchardy C, Rapiti E, Fioretta G, Laissue P, Neyroud-Caspar I, et al. Undertreatment strongly decreases prognosis of breast cancer in elderly women. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3580. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crivellari D, Aapro M, Leonard R, von Minckwitz G, Brain E, et al. Breast cancer in the elderly. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1882. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giordano SH, Duan Z, Kuo YF, Hortobagyi GN, Goodwin JS. Use and outcomes of adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2750. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berry DA, Cirrincione C, Henderson IC, Citron ML, Budman DR, et al. Estrogen-receptor status and outcomes of modern chemotherapy for patients with node-positive breast cancer. Jama. 2006;295:1658. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.14.1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Konigsberg R, Pfeiler G, Klement T, Hammerschmid N, Brunner A, et al. Tumor characteristics and recurrence patterns in triple negative breast cancer: a comparison between younger (<65) and elderly (≥65) patients. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:2962. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watanabe T, Sano M, Takashima S, Kitaya T, Tokuda Y, et al. Oral uracil and tegafur compared with classic cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, fluorouracil as postoperative chemotherapy in patients with node-negative, high-risk breast cancer: National Surgical Adjuvant Study for Breast Cancer 01 Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1368. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.3939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peto R, Davies C, Godwin J, Gray R, Pan HC, et al. Comparisons between different polychemotherapy regimens for early breast cancer: meta-analyses of long-term outcome among 100,000 women in 123 randomised trials. Lancet. 2012;379:432. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61625-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]