Abstract

Importance

BRCA testing is recommended for young women diagnosed with breast cancer, but little is known about decisions surrounding testing and how results may influence treatment decisions in young patients.

Objective

To characterize genetic testing patterns of utilization and the impact on treatment decision-making among young women with breast cancer.

Design

Cross-sectional analysis of data collected between November 2006 and December 2014 as part of the Young Women's Breast Cancer Study, an ongoing prospective cohort study.

Setting

Eleven academic and community medical centers.

Participants

897 women, age 40 and younger at breast cancer diagnosis.

Main outcome measures

1) Frequency and trends in the utilization of BRCA testing; 2) how genetic information is used to make treatment decisions among women who test positive vs. test negative for a BRCA mutation.

Results

87% of women reported BRCA testing by one year post-diagnosis, with the frequency of testing increasing among women diagnosed between 2006 and 2013 from 77% to 95%. Among untested women, 27% (32/117) did not report discussion of the possibility that they might have a mutation with a provider, and 37% (43 /117) were thinking of testing in the future. Approximately 30% (248/831) of women said that knowledge or concern about genetic risk influenced treatment decisions; among these women, 86% of mutation carriers, and 51% of non-carriers chose bilateral mastectomy. Fewer women reported that adjuvant treatment decisions were influenced by genetic risk concern.

Conclusions and relevance

Rates of BRCA1 and 2 mutation testing are increasing in young women with breast cancer. Given that knowledge/concern about genetic risk influences surgical decisions and may affect systemic therapy trial eligibility, all young breast cancer patients should be counseled and offered genetic testing, consistent with NCCN guidelines.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed in women younger than age 40 in the United States.1 Because BRCA1 and BRCA2 (BRCA) mutation carriers are at increased risk for developing early onset breast cancer, National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend that women diagnosed with breast cancer at age 50 or younger undergo genetic testing.2

Assessment of genetic risk in young women following a breast cancer diagnosis can have implications for subsequent clinical treatment decisions. In one study, the 10-year cumulative risk of developing a new cancer in women first diagnosed between the ages of 30 and 34 was 30.7% and in women aged 35-39, 23.7%.3 In addition to consideration of prophylactic mastectomy, breast cancer survivors with a BRCA mutation can be presented with information about other risk-reducing strategies, including bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, which reduces the risk of new primary breast cancer as well as ovarian cancer, and chemoprevention. They are also candidates for increased surveillance options for both breast and ovarian cancer, including annual breast MRIs and trans-vaginal ultrasounds.2 In addition to informing their own individual treatment and surveillance decisions, genetic findings can have implications for family members at risk for harboring the same deleterious mutations, who would need to consider many of these same options if they tested positive for the mutation.

Prior studies have documented underutilization of BRCA testing among younger women with breast cancer, although the figures have improved with time. In one study that surveyed women diagnosed at age 45 and younger between 1993 and 2002, fewer than 20% had BRCA testing.4 In an analysis of 701 women who had been diagnosed with breast cancer at age 40 and younger published in 2010, 24% reported testing.5 However a recent 2014 study of over 300 women with breast cancer at age 50 and younger who were treated at NCCN institutions, 34.1% were sent for genetic counseling.6

In an effort to characterize experiences surrounding genetic testing among young women with breast cancer, we sought to describe utilization of BRCA testing in a cohort of women diagnosed with breast cancer at age 40 and younger and to evaluate how concerns about genetic risk and use of genetic information impacted subsequent treatment decisions. Additionally, we aimed to understand why some young women do not get tested despite the clinical recommendations for this population. .

Methods

Study design and population

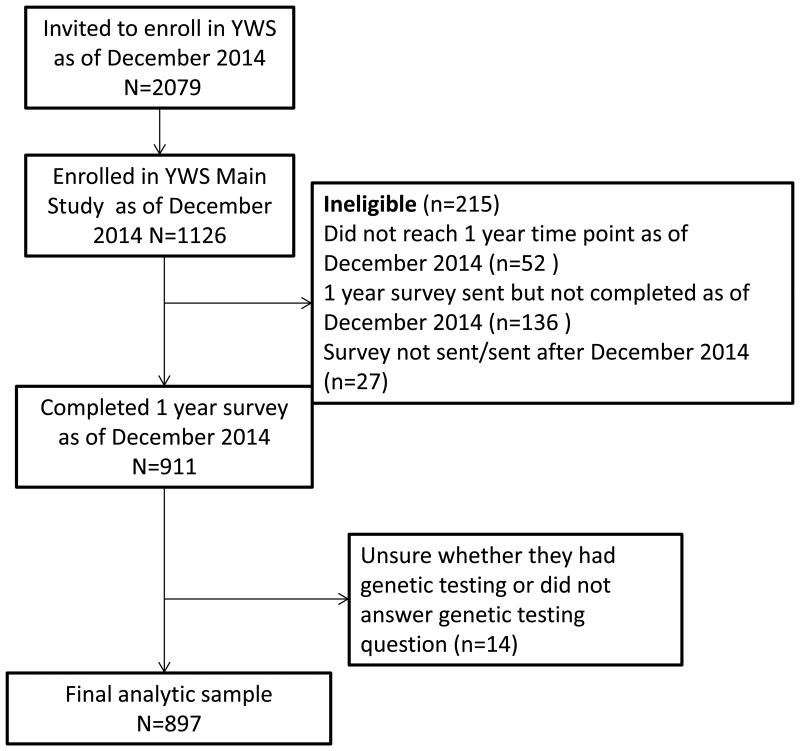

Helping Ourselves, Helping Others: The Young Women's Breast Cancer Study (YWS) is an ongoing, multi-center, prospective cohort established to examine biological, medical, and quality of life (QOL) issues in young women diagnosed with breast cancer at age 40 and younger. Depending on study site, women are identified either through pathology review or staff review of clinic lists. Eligible patients are mailed a recruitment package including a letter introducing the study, two copies of the consent form and a decline form. Patients who have not returned their consent or decline form are contacted by phone within three weeks to inquire about their interest in study participation and are re-sent recruitment materials as needed. Patients who send in their signed informed consents are officially enrolled in the study. After informed consent and enrollment, women are mailed a baseline survey (median: 4.8 months post-diagnosis), additional surveys twice a year for the first 3 years post-diagnosis and annually thereafter. YWS study sites include 9 academic and community hospitals in Massachusetts, as well as academic sites in Denver, CO, Rochester, MN, and Toronto, Canada, although Toronto participants receive a modified version of all surveys and were not included in this analysis. Women who enrolled in the YWS and completed the survey mailed to study participants at one year following diagnosis (n=911), which includes a series of questions about BRCA testing, between November 2006 and December 2014, were eligible to be included in this analysis (Figure 1). The YWS is approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center and other participating sites.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart of study participants included in analytic sample YWS – Young Women's Breast Cancer Study

Measures

Study population characteristics included age at diagnosis, race/ethnicity (assessed with two survey items that ask respondents: 1) whether they consider themselves Hispanic or Latina; 2) what race they consider themselves, with the option to choose one or more pre-specified racial groups, including American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian, Black, Haitian or African American, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander or White), marital status, education, and insurance status. Pathology reports and medical records were reviewed for stage, hormone receptor status, and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (Her2) status. A single item on the baseline survey asks women whether any grandparent was of Ashkenazi descent. Family history of breast and ovarian cancer is collected on the survey administered one year following diagnosis.

A series of items assessing practices surrounding BRCA testing were developed and included in the one-year survey. Women were asked whether they had their blood sent to be tested for a genetic change (a mutation in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene) that increases risk for breast cancer. Women who said they that they had undergone testing were asked for the results; response options included: no abnormality detected in BRCA1 or BRCA2/no mutation detected; deleterious gene alteration/mutation was detected in BRCA1; deleterious gene alteration/mutation was detected in BRCA2 ; deleterious gene alteration/mutation was detected, but I am not sure whether it was in BRCA1 or BRCA2; an indeterminate or unknown variant was detected (an abnormality that is not known to contribute to breast cancer risk); results not yet available; I am not sure what genetic testing showed. Women were also asked to approximate how long after diagnosis they received their results (<1 month; 1-3 months; 3-6 months; 6-12 months; >12 months). There was no option for pre-diagnosis testing, however this comprised a minority of patients.

Women who said they had not undergone testing or were unsure whether they were tested were asked a series of different questions, including whether they discussed the possibility of having a genetic mutation with their doctor(s), whether they were counseled about the likelihood of having a genetic predisposition to develop breast cancer and the implications of potentially having one of these gene mutations on future health and treatment, and reasons why they have not been tested.

All women (tested and untested) were asked whether knowledge or concern about genetic risk of breast cancer (including if testing revealed a deleterious BRCA mutation) influenced treatment decisions. Multiple responses were allowed, and response options included: no; yes, I chose to have the breast where I have developed cancer removed (mastectomy) rather than have a lumpectomy; yes, I chose to have both breasts removed (bilateral mastectomy); yes, I chose to have my ovaries removed; yes, I chose to have one or more of the following treatments that I might not have otherwise taken: tamoxifen; aromatase inhibitor (e.g. anastrozole, letrozole, exemestane); ovarian suppression with medication (e.g. lupron, triptorelin, goserelin); chemotherapy; other. The “other” option was open-ended and women could write in other ways knowledge or concern about genetic risk had influenced treatment decisions.

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize the study population, BRCA testing utilization, and timing of receipt of testing results, and among untested women, to describe whether genetic risk was discussed with a clinician (doctor and/or genetic counselor) and the reasons for not undergoing testing. To test for changes in BRCA testing over time, we used the Cochran-Armitage test for trend. T-tests and Fisher's exact tests were utilized to assess differences in study population characteristics among women who were and were not tested as well as to evaluate how genetic information was used to make treatment decisions among women who tested positive for a BRCA mutation and women who tested negative.. The responses of women who answered “other” to how genetic information was used in treatment decisions were examined qualitatively, and most frequently cited reasons (chose lumpectomy; chose mastectomy; chose not to have bilateral mastectomy) were collapsed and summarized. Women who responded that they were unsure about testing or did not respond to this question, however answered the question asking for their test results were re-coded as “tested”; those who did not subsequently answer the question about their results (n=14) were excluded, leaving 897 women in the analytic sample. Sample sizes vary somewhat across analyses owing to non-response or discordant responses on specific items. A two-sided p-value ≤.05 was used as the threshold for statistical significance. Analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.).

Results

Study population characteristics are detailed in eTable 1. Mean age at diagnosis among women who were tested was younger than that of untested women (35.3 years vs. 36.9 years, p<.001). Among women for whom stage of disease was available, most had either Stage I (35%) or a Stage II (40%) disease. Most women had at least a college education (85%) and were insured (99.8%). Among women who were tested, a higher proportion of women reported at least one second or third degree relative with breast or ovarian cancer (52%) compared to women who were not tested (38%); other study population characteristics were similar between tested and untested women.

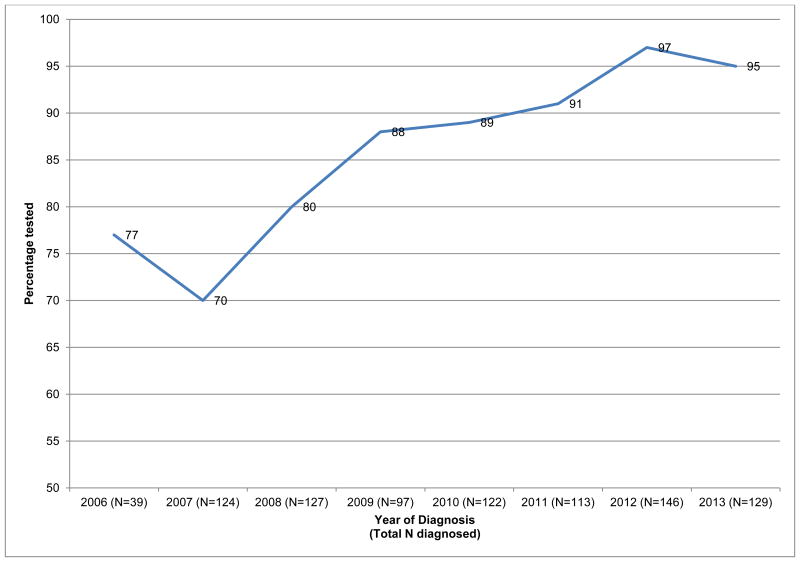

The majority of women reported being tested for a BRCA mutation, and only thirteen percent (117/897) had not undergone testing for a BRCA mutation when surveyed one year after diagnosis. Figure 2 details BRCA test utilization by year of diagnosis. Of 39 women who were diagnosed in 2006, 30 reported testing (77%). In 2007, a slightly lower percentage of women (70%) reported testing, however, the proportion tested increased each subsequent year (Cochran-Armitage test for trend, p <.001), with 97% (141/146) and 95% (123/129) of women diagnosed in 2012 and 2013, respectively, reporting BRCA testing.

Figure 2.

Trends in BRCA testing in the YWS cohort (N=897) YWS – Young Women's Breast Cancer Study

Among women who had undergone BRCA testing (n=780), approximately 8% reported a BRCA1 mutation, 4% reported a BRCA2 mutation, 5% reported an indeterminate result or variant of unknown clinical significance, and 81% reported a negative test result (Table 1). The majority of women said they had received their results within 6 months of their diagnosis. Among women who responded (754/780) regarding timing of return of BRCA results after diagnosis, 37% said they had received their results less than one month following diagnosis, 45% 1-3 months following diagnosis, and 10% 3-6 months after diagnosis.

Table 1. BRCA testing results (N=780).

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| BRCA1+ | 59 (8)a |

| BRCA2+ | 35 (4) |

| Unsure whether BRCA1+ or BRCA2+ | 2 (<1) |

| Indeterminate or unknown variant detected | 36 (5)a |

| Tested negative | 634 (81) |

| Tested with results missing, discordant, not available, unknown, or unsure what testing showed | 15 (2) |

One woman reported a BRCA1 mutation and an indeterminate variant

Among the women who were not tested (n=117), 68% said they had discussed, or were counseled about the possibility of having a BRCA mutation or genetic pre-disposition to breast cancer with their doctor or with a genetic counselor. Of the women who did not report discussion of these issues with a clinician (n=37), 19% said they were planning to discuss this in the future, 22% were considering a future discussion, 30% were not sure whether they wanted to discuss this in the future, one person responded that they were considering but also not sure they wanted to discuss in future, 14% were not interested in discussing these issues and 14% did not respond to this question.

The reasons women cited for not undergoing testing are included in eTable2. Approximately one-quarter of women said they did not think they were at risk for having a mutation, with a similar proportion reporting that they were not tested because their doctor thought it was unlikely they had a mutation. Other common reasons for not undergoing testing included, “not a priority” (18%), concerns about potential insurance or work issues related to a positive test (13%), and inability to afford to undergo testing (11%). Thirty-seven percent of untested women said they were thinking about getting tested in the future.

Approximately 30% (248/831) of patients who were tested and reported a positive or negative result responded that knowledge or concern about genetic risk of breast cancer influenced their treatment in some way. Among these women (Table 2), 86% of mutation carriers and 51% of non-carriers women chose a bilateral mastectomy (p<.001). Mutation carriers were also more likely (p<.001) to have had a salpingo-oophorectomy (53%) compared non-carriers (3%). Fewer women reported that systemic treatment decisions were influenced by genetic risk concern, and there were no significant differences between carriers and non-carriers, regarding the impact of genetic concerns on choosing chemotherapy, ovarian suppression, or endocrine treatment. Of 65 women who cited the reason for how knowledge or concern about genetic risk influenced their treatment as “other”, 62% (40/65) responded that they either chose lumpectomy or mastectomy or chose not to have a bilateral mastectomy.

Table 2. Among women for whom genetic concerns influenced treatment decisions (248/831)a, patients reported choosing the followingb.

| BRCA+<br>(N=88)<br>N (%) | Tested/BRCA-<br>(N=160)<br>N (%) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I chose to have the breast where I have developed cancer removed rather than have a lumpectomy | 6 (7) | 17 (11) | .37 |

| I chose to have both breasts removed | 76 (86) | 82 (51) | <.001 |

| I chose to have my ovaries removed | 47 (53) | 4 (3) | <.001 |

| I chose to have one or more of the following treatments that I might not have otherwise taken | |||

| Tamoxifen | 13 (15) | 29 (18) | .60 |

| Aromatase inhibitor | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | >.99 |

| Ovarian suppression with medication | 1 (1) | 8 (5) | .16 |

| Chemotherapy | 14 (16) | 17 (11) | .24 |

Of 897 respondents, we excluded 15 women whose genetic testing results were unknown, 12 women with indeterminate results, 23 women who were not tested, and16 women with discordant or missing responses to this question.

Responses are non-mutually exclusive, with participants asked to select all reasons that apply.

Discussion

With 87% of women having been tested for a BRCA mutation, the utilization of testing in our cohort of young women far exceeds the prevalence of testing reported in several other studies of women with early-onset breast cancer.4,5,7 Since the YWS began enrolling women in 2006, the proportion of women who underwent testing increased, with almost all women diagnosed in the 2012 and 2013 reporting BRCA testing when surveyed at one year post-diagnosis. The high frequency of BRCA testing likely reflects the fact that the majority of women enrolled in our cohort were insured, educated, and treated at cancer centers where comprehensive genetic counseling and testing services are widely available. Secular trends in genetic testing are one explanation of the increase in BRCA testing we detected. Of the women who did not undergo testing, approximately one-third said that they had not discussed the possibility that they might have a mutation with their doctor. Recent media attention to hereditary breast cancer risk (e.g., “The Angelina Jolie effect”)8 might have made women more likely to bring up the issue of genetic risk with their providers, possibly leading to more testing of women who were diagnosed in 2012 and 2013 relative to earlier years (2006-2011). In an analysis of referral patterns to a group of high-risk hereditary cancer clinics in England, Evans et al. reported that both referrals for genetic counseling and BRCA testing increased substantially between 2012 and 2013.9 A recent Canadian study described a similar, dramatic increase in both counseling and testing when comparing referral patterns in the 6 months before the Jolie op-ed was published to the 6 month period following publication.10

Among the women in our study who were not tested, some might not have initially chosen testing because of more immediate concerns or prioritization of other decisions related to treatment. It is important to consider that the decision to undergo testing and process information about genetic risk in women with a recent breast cancer diagnosis occurs when women are already under stress about the decisions they need to make pertaining to treatment. In a prior study by Weitzel et al., three women who were candidates chose not to be tested because of distress related to their recent diagnosis.11 In a small study inclusive of 26 breast cancer patients from the Netherlands who had rapid genetic counseling and (optional) testing (RGC(T)), more than half of women responded that RGC(T) was associated with added distress, separate from the distress they experienced as a result of their diagnosis.12 In a qualitative study conducted by Zilliacus et al., interviews with women who were diagnosed with breast cancer at age 50 and younger revealed that while some women acknowledge that anxiety associated with not yet knowing what testing showed during a challenging time was a downside, many women also viewed handling “all bad news” at once and negotiating the emotions of these multiple challenges at a single time point was a positive. Further, women also valued the potential for genetic testing to inform surgical choice.13 Conveying the importance of testing in the context of the decisions they are making regarding their primary treatment, while at the same time ensuring that women are supported and concerns about genetic risk and testing are adequately addressed, is essential.

Many women who were tested knew the results of their BRCA test within one month of diagnosis and therefore likely had this information prior to making their decision about surgery. Of the women in our study who said concern about genetic risk influenced their treatment decisions, those with a BRCA mutation were more likely to choose bilateral mastectomy compared to women who were not tested. Other studies of the impact of BRCA testing on treatment decisions have similarly found that women who receive a positive test result are more likely to have bilateral surgery compared to women who test negative.11,14-17 Notably, bilateral mastectomy was still relatively common in our study even among non-carriers, suggesting that many women might choose to remove both breasts because of worries about developing another breast cancer and for peace of mind, despite knowing they do not carry a known BRCA mutation.18 It might also suggest a need for better communication of the relatively low risk of contralateral breast cancer among women who are non-carriers3, that this risk has been decreasing in recent years,19 and that bilateral mastectomy is not associated with improved survival.20 The majority of women in our cohort received chemotherapy; therefore, most women were unlikely to perceive receipt of adjuvant treatment as affected by their genetic testing results. However, several recent clinical trials have used BRCA status as a potentially prognostic factor in both the neo-adjuvant and adjuvant setting.21 In addition, BRCA status can influence systemic therapy trial eligibility. For example, PARP inhibitors are a new category of targeted therapy that has demonstrated preliminary efficacy almost exclusively in BRCA mutated cancers.21 Regarding endocrine treatment, similar proportions of women said that concern about genetic risk influenced this treatment decision. While there are some data that suggest some potential benefit of endocrine treatment in preventing contralateral breast cancer in BRCA mutation carriers,22 there have not been prospective or randomized studies of tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors in a chemopreventive setting among BRCA carriers with a history of unilateral breast cancer. Further, in our cohort, where most BRCA carriers did have a bilateral mastectomy, any additional benefit for endocrine therapy as a chemo-preventive strategy for contralateral breast cancer would likely be minimal.

It is important to consider our findings in the context of some limitations. Most women included in this analysis would have undergone testing when Myriad was the only commercial laboratory offering clinical testing, and testing for BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 was the only testing available. Given the recent expansion of testing options (e.g., genome-wide sequencing, multi-gene panels), it is clear that testing patterns are changing. Future studies are warranted to evaluate the utilization and impact of other tests.

Given that the purpose of this analysis was to evaluate patient perception of the experience surrounding BRCA testing, we chose to use self-report of genetic test results. In a prior analysis of a subset of the YWS cohort,18 we did review medical records to confirm self-reports of mutation status and found the two ascertainment methods to be highly concordant. While it is reassuring that most women in our cohort are tested as recommended, because a large proportion of these women are treated in academic cancer center settings and almost everyone is insured, the generalizability of our findings, including reasons for not undergoing testing as well as the degree to which concerns about genetic risk impact treatment decisions, might be limited.

Our findings highlight recent trends, experiences, and perspectives surrounding BRCA testing in women diagnosed with breast cancer at age 40 and younger. Because women in our cohort are asked about BRCA testing in future surveys, we will be able to assess whether those women who said they were thinking about getting tested subsequently did get tested at a later time. Further, it is possible that mutation carriers who initially did not choose risk-reducing surgeries might decide to have these procedures later in the survivorship period; longer-term follow-up may provide additional information about the impact of testing on treatment decisions and, ultimately, outcomes, over time.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Partridge and Dr. Rosenberg had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding sources: Susan G. Komen for the Cure (A. Partridge); NIH R25 CA057711 (S. Rosenberg); The Pink Agenda (S. Rosenberg).

Footnotes

Role of funders: The funders had no specific role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of Interest/Disclosures: Dr. Garber receives research funding from Myriad Genetics and Ambry Genetics and is a consultant for Pfizer and Sequenom. No other conflicts are reported.

References

- 1.Bleyer A, Barr R. Cancer in young adults 20 to 39 years of age: overview. Semin Oncol. 2009;36(3):194–206. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical practices guidelines in oncology: Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: Breast and ovarian v.1.2014. [Accessed August 4, 2014]; [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malone KE, Begg CB, Haile RW, et al. Population-based study of the risk of second primary contralateral breast cancer associated with carrying a mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(14):2404–2410. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown KL, Hutchison R, Zinberg RE, McGovern MM. Referral and experience with genetic testing among women with early onset breast cancer. Genet Test. 2005;9(4):301–305. doi: 10.1089/gte.2005.9.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruddy KJ, Gelber S, Shin J, et al. Genetic testing in young women with breast cancer: results from a Web-based survey. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(4):741–747. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stuckey A, Febbraro T, Laprise J, Wilbur JS, Lopes V, Robison K. Adherence Patterns to National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines for Referral of Women With Breast Cancer to Genetics Professionals. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014 doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peters N, Domchek SM, Rose A, Polis R, Stopfer J, Armstrong K. Knowledge, attitudes, and utilization of BRCA1/2 testing among women with early-onset breast cancer. Genet Test. 2005;9(1):48–53. doi: 10.1089/gte.2005.9.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jolie A. My Medical Choice. The New York Times. 2013 May 14; [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans DGR, Barwell J, Eccles DM, et al. The Angelina Jolie effect: how high celebrity profile can have a major impact on provision of cancer related services. Breast Cancer Research. 2014;16(5) doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0442-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raphael J, Verma S, Hewitt P, Eisen A. The impact of Angelina Jolie's (AJ) story on genetic referral and testing at an academic cancer centre. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(suppl 26) doi: 10.1007/s10897-016-9973-6. abstr 44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weitzel JN, McCaffrey SM, Nedelcu R, MacDonald DJ, Blazer KR, Cullinane CA. Effect of genetic cancer risk assessment on surgical decisions at breast cancer diagnosis. Arch Surg. 2003;138(12):1323–1328. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.12.1323. discussion 1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wevers MR, Hahn DE, Verhoef S, et al. Breast cancer genetic counseling after diagnosis but before treatment: a pilot study on treatment consequences and psychological impact. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89(1):89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zilliacus E, Meiser B, Gleeson M, et al. Are we being overly cautious? A qualitative inquiry into the experiences and perceptions of treatment-focused germline BRCA genetic testing amongst women recently diagnosed with breast cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(11):2949–2958. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1427-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwartz MD, Lerman C, Brogan B, et al. Impact of BRCA1/BRCA2 counseling and testing on newly diagnosed breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(10):1823–1829. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lokich E, Stuckey A, Raker C, Wilbur JS, Laprise J, Gass J. Preoperative genetic testing affects surgical decision making in breast cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;134(2):326–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elsayegh N, Kuerer HM, Lin H, et al. Predictors that influence contralateral prophylactic mastectomy election among women with ductal carcinoma in situ who were evaluated for BRCA genetic testing. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(11):3466–3472. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3747-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howard-McNatt M, Schroll RW, Hurt GJ, Levine EA. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in breast cancer patients who test negative for BRCA mutations. Am J Surg. 2011;202(3):298–302. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenberg SM, Tracy MS, Meyer ME, et al. Perceptions, Knowledge, and Satisfaction With Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy Among Young Women With Breast Cancer: A Cross-sectional Survey. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(6):373–381. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-6-201309170-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nichols HB, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Lacey JV, Jr, Rosenberg PS, Anderson WF. Declining incidence of contralateral breast cancer in the United States from 1975 to 2006. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(12):1564–1569. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.7395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurian AW, Lichtensztajn DY, Keegan TH, Nelson DO, Clarke CA, Gomez SL. Use of and mortality after bilateral mastectomy compared with other surgical treatments for breast cancer in California, 1998-2011. JAMA. 2014;312(9):902–914. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.10707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trainer AH, Lewis CR, Tucker K, Meiser B, Friedlander M, Ward RL. The role of BRCA mutation testing in determining breast cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7(12):708–717. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gronwald J, Tung N, Foulkes WD, et al. Tamoxifen and contralateral breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers: an update. Int J Cancer. 2006;118(9):2281–2284. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.