Abstract

Background

Current commercialized small-diameter arterial grafts have not shown clinical effectiveness due to their poor patency rates. The purpose of the present study is to evaluate the feasibility of arterial bioresorbable vascular graft, which has a porous sponge type scaffold, as a small-diameter arterial conduit.

Methods

The grafts were constructed by a 50:50 poly (l-lactic-co-ε-caprolactone) copolymer (PLCL) scaffold reinforced by a poly (l-lactic acid) (PLA) nano-fiber. The pore size of the PLCL scaffold was adjusted to a small size (12.8 ± 1.85 μm) or a large size (28.5 ± 5.25 μm). We compared the difference in cellular infiltration followed by tissue remodeling between the groups. The grafts were implanted in 8–10 week old female mice (n = 15 in each group) as infra-renal aortic interposition conduits. Animals were followed for 8 weeks and sacrificed to evaluate neotissue formation.

Results

No aneurysmal change or graft rupture was observed in both groups. Histologic assessment demonstrated favorable cell infiltration into scaffolds, neointimal formation with endothelialization, smooth muscle cell proliferation, and elastin deposition in both groups. No significant difference was observed between the groups. Immunohistochemical characterization with anti-F4/80 antibody demonstrated that macrophage infiltration into the grafts occurred in both groups. Staining for M1 and M2, which are the two major macrophage phenotypes, showed no significant difference between groups.

Conclusions

Our novel bioresorbable vascular grafts showed well-organized neointimal formation in the high pressure arterial circulation environment. Whereas the large pore size scaffold did not improve cellular infiltration and neotissue formation when compared to the small pore scaffold.

Keywords: Tissue engineering, Bioresorbable vascular grafts, Small-diameter arterial grafts, Pore size, Electrospinning technique

The most pressing limitation in using autografts for cardiovascular surgeries is insufficient availability of viable tissue in patients, especially patients with widespread atherosclerotic vascular disease. For patients with viable tissue, there is often a lack of harvestable vessels due to previous cardiovascular surgical procedures [1]. If the patient has viable tissue, they must be subjected to additional surgical procedures for harvesting and preparing the tissue grafts. To alleviate these issues, prosthetic arterial grafts have arisen as a viable alternative to autologous arterial or venous substitutes required for patients with cardiovascular diseases.

Current commercialized prosthetic grafts composed of expanded-polytetrafluoroethylene or polyethylene terephthalate have arisen as a substitute and have shown promise in large blood vessels (>6mm). However, they have not yet shown clinical effectiveness for small-diameter arteries (< 6 mm) due to their poor patency rates [2]. To address this challenge, small diameter bioresorbable vascular grafts have arisen as an alternative to non-bioresorbable prosthetic grafts [3]. These bioresorbable vascular grafts are created to restore function and, over time, transform into biologically active blood vessels [4].

Bioresorbable vascular grafts are biologically active grafts which are entirely reconstituted by host-derived cells over the course of an inflammation-mediated degradation process [5]. The application of bioresorbable vascular grafts has several advantages such as growth potential, favorable biocompatibility, and low risk of infection or rejection. Clinical evidence has now shown that bioresorbable vascular grafts have had some success in limited clinical trials to use for pediatric patients undergoing extracardiac total cavopulmonary connection procedures [6, 7]. In those studies, a porous, bioresorbable sponge type scaffold composed of poly(l-lactide-co-ε-caprolactone) (PLCL) and reinforced by a mesh of poly(glycolic acid) (PGA) was successfully applied to venous circulation in a low pressure environment (<30mmHg) [8]. To apply bioresorbable vascular grafts to the high pressure environment of the arterial circulation system, a resistance to thrombosis, aneurysmal dilatation, and neotissue hyperplasia is required [1]. These things may be accomplished through attention to scaffold architecture and especially pore size.

Scaffold architecture plays a crucial role in achieving success in the high pressure arterial circulation system. In the present study, we utilized a porous sponge type scaffold with continuous pores. This scaffold was fabricated with the identical materials and methods as the grafts used in our prior clinical studies [4]. However, this graft is applied in pulsatile arterial circulation and is therefore reinforced by poly (l-lactic acid) (PLA) to endure the high pressure arterial environment.

Pore size is another important aspect of scaffold architecture. Large pores showed enhanced vascular regeneration and remodeling by mediating macrophage polarization into the tissue-remodeling M2 phenotype compared to grafts with small pores (about 5 μm) [9]. Our previous findings also demonstrated that, when compared to small-pores (<1 μm), large pores (about 30 μm) induced a well-organized neointima [10]. Based on these studies, we created the large pore scaffold to compare cellular infiltration and neotissue formation with the small pore scaffold.

We hypothesized that a large pore scaffold would improve cellular infiltration and neotissue formation when compared to a small pore scaffold due to macrophage polarization toward a M2 phenotype. The purposes of the present study are 1) to evaluate the feasibility of arterial bioresorbable vascular graft, and 2) to confirm whether a large pore scaffold improves neotissue formation when compared to a small pore scaffold by using a murine aortic implantation model.

Material and Methods

Preparation for bioresorbable vascular grafts

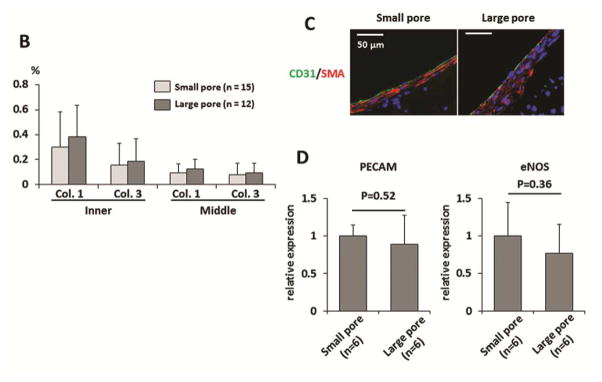

The grafts were constructed by pouring a solution of 50:50 poly (l-lactic-co-ε-caprolactone) copolymer (PLCL) into a glass tube, then freeze-drying under a vacuum as previously described [11]. The pore size was adjusted to obtain two different scaffold groups: small (12.8 ± 1.85 μm) and large (28.5 ± 5.25 μm) (Figure 1). Next, these scaffolds were reinforced by electrospinning poly (l-lactic acid) (PLA) nano-fiber (40μm thickness) to the outer side of the PLCL scaffold. Inner luminal diameters of each graft were around 600 μm.

Fig. 1.

Representative scanning electron microscopy images of the grafts. The scaffolds were constructed by pouring a solution of PLCL into a hollow glass tube followed by freeze-drying under a vacuum, and pore sizes were adjusted to small pores (12.8 ± 1.85 μm) and large pores (28.5 ± 5.25 μm). These scaffolds were reinforced by PLA nano-fiber, which were made using electrospinning technology, with 40μm thickness at the outer side of PLCL scaffold. Inner luminal diameters of each graft were around 600 μm.

Animal model and surgical implantation

All animals received humane care in compliance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) guideline for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Mean arterial pressure of C57BL/6 mice is 110 ± 2 mmHg [12]. Grafts of 3mm in length were implanted by two microsurgeons in 8–10 week old female mice (n = 15 for each group) as infra-renal aortic interposition conduits using standard microsurgical techniques [13]. Low pressure vascular clamps (Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA) were used for cross clamping and 400 U/kg of heparin was injected intramuscularly 5 minutes before unclamping. Animals were followed for 8 weeks to evaluate the graft remodeling. An aspirin-mixed diet (0.1% of diet) was fed to mice in both groups 3 days before and 3 days after surgery to prevent acute thrombosis.

Histology, immunohistochemistry, and immunofluorescence

Explanted grafts at 8 weeks after implantation were fixed in 4% para-formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, sliced (5 μm thick sections), and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (HE), Masson’s Trichrome, and Hart’s. To obtain luminal diameter and wall thickness measurements the outer and luminal perimeters of the grafts were manually measured from HE staining with Image J software (NIH, Bethesda, MD). Collagen deposition was assessed with Picrosirius red staining and images were obtained with polarized light microscopy. Based on previous reports, we correlated thick fibers (orange to yellow) with collagen I and thin fibers (green) with collagen III [14]. The proportion of collagen I and collagen III in the neotissue of the grafts was measured with Image J software.

Identification of macrophages, M1 macrophages, and M2 macrophages were done by immunohistochemical staining of paraffin-embedded explant sections with anti-F4/80 antibody (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA), anti-iNOS antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and anti-Mannose Receptor (CD206) antibody (Abcam), respectively. Primary antibody binding was detected using biotinylated IgG (Vector, Burlingame, CA), and this was followed by the binding of streptavidin-horse radish peroxidase and color development with 3, 3-diaminobenzidine.

Immunofluorescent staining for CD31 as a marker of endothelial cells and for α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) as markers of SMCs was performed using rabbit anti-CD31 primary antibody (1:50, Abcam) and mouse anti-α-SMA primary antibody (1:500, DAKO), followed by Alexa Fluor 647 anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (1:300, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and Alexa Fluor 488 anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:300, Invitrogen), respectively. Fluorescence images were obtained with an Olympus IX51 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

RNA extraction and reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Explanted grafts at 8 weeks after implantation were frozen in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA), and sectioned into twenty 30 μm sections. Total RNA was extracted and purified using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription was performed using a High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). All reagents and instrumentation for gene expression analysis were obtained from Applied Biosystems. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed with a Step One Plus Real-Time PCR System using the TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix Kit. Reference numbers for primers are: PECAM (Mm01242584_m1), eNOS (Mm00435217_m1), and HPRT (Mm00446968_m1). The results were analyzed using the comparative threshold cycle method and normalized with HPRT as an endogenous reference, and reported as relative values (ΔΔ CT) to those of the small pore group.

Statistical analysis

Numeric values are listed as mean ± standard deviation. The number of experiments is shown in each case. Data of continuous variables with normal distribution were evaluated by student t test. P values less than 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Animal Survival

Fifteen grafts for each group were implanted as infra-renal interposition aortic conduits. All mice in the small pore group survived the 8 week implantation period with patent grafts. There were no complications, such as bleeding, acute thrombosis, aneurysmal change or graft rupture (8 weeks), in the small pore group. However, in the large pore group, 2 mice were sacrificed due to lower limb paralysis from acute thrombosis, and 1 mouse died of undetermined causes (the graft which was explanted from the mouse was patent). The grafts in the survived mice were all patent. These findings were confirmed by autopsy within 24 hours after death or severe paralysis of lower limbs.

Cell infiltration and quantitative morphometric analysis

HE staining showed cell infiltration within the scaffold in both groups (Figure 2 A), and nuclei were counted to obtain the number of cells in the inner-, middle-, and outer- layers of the scaffold. The large pore group indicated higher cell infiltration in all layers, although there was no statistical difference (2.45 ± 0.77 ×103/mm2 vs. 3.22 ± 1.04 ×103/mm2 in inner layer, 2.36 ± 1.50 ×103/mm2 vs. 2.61 ± 1.37 ×103/mm2 in middle layer, 1.11 ± 0.57 ×103/mm2 vs. 1.35 ± 0.95 ×103/mm2 in outer layer, and 5.93 ± 2.19 ×103/mm2 vs. 7.17 ± 2.23 ×103/mm2 in total layer, small pore group and large pore group, respectively) (Figure 2 B). There was no statistical difference in the luminal diameter (small pore group: 663 ± 42 μm vs. large pore group: 720 ± 113 μm, P=0.12) (Figure 2 C) or wall thickness (small pore group: 300 ± 22 μm vs. large pore group: 272 ± 46 μm, P=0.07) (Figure 2 D) between groups. There was no aneurysmal formation in either group.

Fig. 2.

(A) Scaffold cellular infiltration at 8 weeks after implantation. Hematoxylin and Eosin (HE) staining demonstrated dense cellular infiltration into the PLCL scaffold layer. (B) Nuclei were counted to obtain the number of infiltrated cells in the inner-, middle-, and outer- layers of the scaffold. The large pore group indicated higher cell numbers in all layers, although there was no statistical difference. (C and D) Neither luminal diameter nor wall thickness differed between groups.

Extracellular matrix deposition, Endothelialization, and smooth muscle cell proliferation in the graft

Extracellular matrix (ECM) is the primary determinant of the biomechanical properties of a tissue-engineered neovessel. Consequently, we evaluated ECM components including collagen and elastin by histology. Masson’s Trichrome and Hart’s staining showed collagen and elastin deposition in neointima respectively (Figure 3 A).

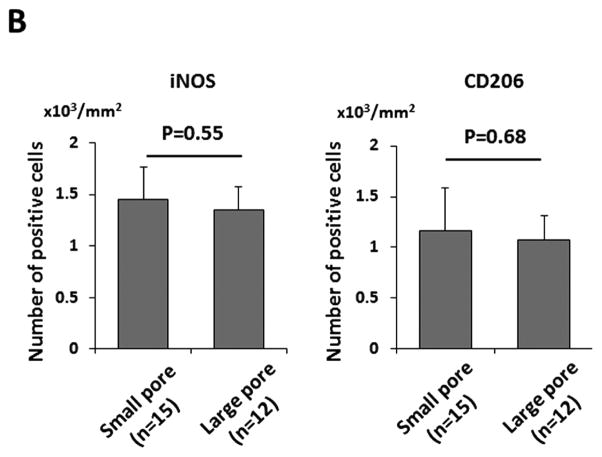

Fig. 3.

Histological analysis of the grafts at 8 weeks after implantation. (A) Masson’s Trichrome and Hart’s staining showed collagen and elastin deposition in the neointima, respectively. Visualization of Picrosirius red staining with polarized light microscopy was used to evaluate the deposition of thin (type III; green) to thick (type I; yellow) collagen fibers in each group. (B) Higher deposition of both collagen I and III were observed both in inner and middle scaffold layers of the large pore group, although there was no statistical difference between the groups in the distribution of collagen type I or type III. (C) Endothelialization of the grafts at 8 weeks after implantation. Representative immunofluorescent images of endothelial cell staining (CD31) and smooth muscle cell staining (αSMA). Endothelial cell coverage on the luminal surface of the graft with SMCs surrounding them was observed in both groups equally. (D) Gene expression was analyzed by RT-qPCR using the ΔΔ CT method. There was no statistical difference of relative expression of PECAM or eNOS in explanted grafts between the groups.

Visualization of Picrosirius red staining with polarized light microscopy was used to evaluate the proportion of thin (type III) to thick (type I) collagen fibers in each group for quantitative measurement of collagen deposition. We divided the scaffold into inner and middle layers to better quantify the robust collagen deposition we observed in the inner layer of the scaffold. Higher deposition of both collagen I and III were observed in both the inner and middle scaffold layers of the large pore group, although there was no statistical difference between the groups in the distribution of collagen type I or type III (Collagen 3, small pore group: 0.30 ± 0.28 % vs. large pore group: 0.38 ± 0.25 %, P=0.49; Collagen III, small pore group: 0.16 ± 0.18 % vs. large pore group: 0.18 ± 0.18 %, P=0.73 in inner layer; Collagen I, small pore group: 0.09 ± 0.07 % vs. large pore group: 0.13 ± 0.08 %, P=0.33; Collagen III, small pore group: 0.08 ± 0.09 % vs. large pore group: 0.10 ± 0.07 %, P=0.63 in middle layer.) (Figure 3 B).

Endothelialization on the luminal surface of a graft is thought to be a crucial step in the development of well-organized neotissue [15]; likewise, SMCs are the predominant cells in the arterial wall and are essential for the structural and functional integrity of the neovessel. To evaluate endothelialization and SMCs proliferation in implanted grafts, CD31 staining and αSMA staining was employed respectively. A layer of endothelial cell coverage on the luminal side of the grafts followed by a SMC layer was observed in both groups equally (Figure 3 C). For the quantitative comparison of endothelialization between groups, gene expression of PECAM and eNOS in explanted grafts was measured and demonstrated no statistical difference between the groups (PECAM, small pore group: 1.00 ± 0.14 vs. large pore group: 0.89 ± 0.38, P=0.52; eNOS, small pore group: 1.00 ± 0.45 vs. large pore group: 0.77 ± 0.38, P=0.36) (Figure 3 D).

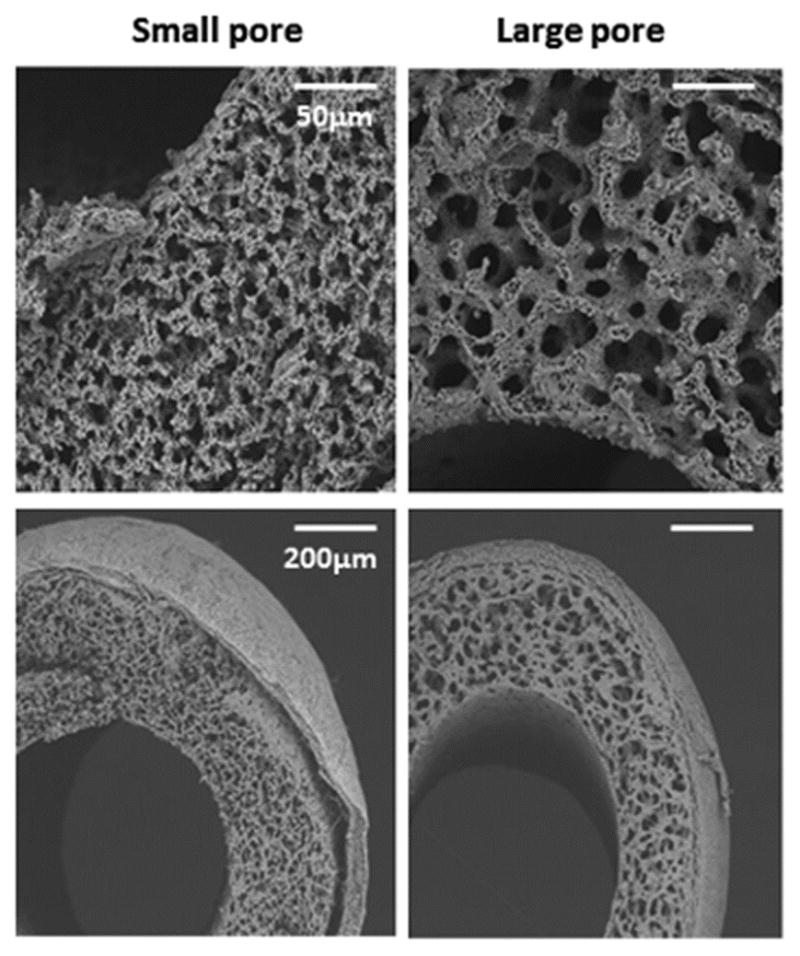

Infiltration of macrophages into grafts

Immunohistochemical characterization with anti-F4/80 antibody demonstrated that macrophage infiltration into the grafts occurred in both groups (Figure 4 A). Staining for M1 and M2, which are the two major macrophage phenotypes, in the grafts showed no significant difference between groups (iNOS, small pore group: 1.45 ± 0.32 ×103/mm2 vs. large pore group: 1.35 ± 0.22 ×103/mm2, P=0.55; CD206, small pore group: 1.17 ± 0.42 ×103/mm2 vs. large pore group: 1.08 ± 0.23 ×103/mm2, P=0.68) (Figure 4 A, B).

Fig. 4.

Macrophage infiltration of the grafts 8 weeks after implantation was evaluated by histological assessment. (A) Representative images of immunohistochemical staining of F4/80 (entire macrophage), iNOS (M1 macrophage), and CD206 (M2 macrophage). (B) The number of M1 and M2 macrophage, defined by iNOS and CD206 respectively, showed no significant difference between the groups.

Comment

Based on current advances of our clinical trial using a bioresorbable vascular graft in a high flow, low pressure venous circulation, we demonstrated that a porous sponge type scaffold has potential to be applied as a small diameter vascular graft used in a high flow and high pressure arterial system. In this study, we applied an electrospinning technique to the outer layer of the graft to endure arterial pressures and prevent blood leakage from the scaffold [15]. This Bi-layered approach was shown to have artery-like mechanical properties [16], and applying it to the arterial grafts showed successful results in a rat aortic implantation model [17].

The scaffold material and structure are the most critical components in bioresorbable vascular grafts because they provide a temporary three-dimensional structure for cellular attachment and proliferation in vivo. These scaffolds are typically porous and possess biomimetic properties, which thereby facilitate cellular infiltration, stimulation of neotissue formation, and integration with native tissue [18]. For bioresorbable vascular grafts in particular, scaffold materials should demonstrate mechanical properties akin to the native vessel, namely strength, durability, and compliance. Furthermore, these materials must ensure biocompatibility so as not to induce an immunological response [19]. Extensive research involving the safety and efficacy using biodegradable polymers, such as PLCL and PGA, has been explored for this purpose [6, 7]. For example, the bioresorbable vascular graft used for our clinical trial was composed of a scaffold with a porous PLCL sponge and a PGA fiber mesh to reinforce the scaffold [8].

After graft implantation we followed the grafts for 8 weeks. This time period was based on our previous report, which showed organized vascular neotissue in the internal lumen of the scaffold after 6 weeks in the mouse aortic implantation model [11]. Therefore an 8-week time point was deemed the optimal end-point for evaluating feasibility of the graft. However, the lumen size of the grafts increased at 8 weeks, roughly 10% for the small pore group and 20% for the large pore group, which may indicate the possibility of aneurysmal formation at a later time point. Be that as it may, the large pore group had several advantages over the small pore group. First, the large pore group promotes cell infiltration, which will result in favorable neotissue formation; second, the large pore design reduces inflammation, which causes neointimal hyperplasia and calcification of grafts; and third, it has been shown that large pores (around 40 μm) with thick electrospun fibers of PCL enhanced the vascular regeneration and remodeling process by mediating macrophage polarization into the M2 phenotype [9].

Cardiac implantation of acellular scaffolds composed of a poly (2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate-co-methacrylic acid) hydrogel with pore diameters of 30–40 μm increased angiogenesis and reduced fibrotic response due to a shift in the macrophage phenotype to the M2 state [20]. A uniform 30–40 μm pore size appears to bias macrophage polarization to the M2 phenotype and induce subsequent healing [21]. In this study, we designed the large pore size as approximately 29 μm and the small pore size as approximately 13 μm. We expected a beneficial effect using the large pore scaffold in cell infiltration compared to using the small pore scaffold. However, the results of the present study were not as we expected. These two pore sizes were maximum and minimum for fabrication of the PLCL sponge with our current technique. However, the pore size of the ‘large pore’ scaffold is smaller than those previously reported [9, 10, 20, 21], which might not be large enough to decrease polarization into M1 macrophages. In addition, very small pores, with less than a 5 μm diameter, were still observed in the scaffold in the large pore group as well as in the small pore group, as shown in Figure 1. The heterogeneous pore size of the graft is another possible reason why the large pore scaffold did not show its advantage in both improved cell infiltration and reduced inflammatory response.

Luminal roughness should be one of the most important factors of thrombogenicity of the graft. We observed two acute thrombosis in the large pore group. Large pores created a rough lumenal surface on the scaffold, which may have induced thrombosis. Generally, in the case of small-diameter vascular grafts, early thrombus formation often causes graft failure [22]. In this study, the electrospun grafts with smaller fiber diameters (<1 μm) showed reduced early thrombogenecity and performed better overall, than the grafts produced with bigger fiber diameter (5 μm). This may be due to lower platelet adhesion and lower activation of platelets in the coagulation cascade [22].

Blood compatibility of the graft is another important factor of thrombogenicity. Chen et al. reported encapsulating heparin into the core of PLCL core-shell nanofibers via emulsion electrospinning to fabricate a nanofiber scaffold for anticoagulation [23]. Jiang et al. demonstrated that modification of decellularized vascular grafts with elastomer and heparin resulted in significant improvement in antithrombotic properties [24]. Although no acute thrombosis was observed in the small pore group, improvement of blood compatibility must be essential for our aortic graft.

One limitation of this study is from a clinical standing point. Small caliber human grafts would be 2–5 mm in diameter and it is not clear if our grafts will tolerate the wall tension as the diameter increases.

In conclusion, a novel bioresorbable vascular graft with a porous PLCL sponge type scaffold reinforced by PLA nano-fibers has potential to be applied to small-diameter arterial grafts. Whereas the large pore size scaffold did not improve cellular infiltration and neotissue formation when compared to the small pore scaffold. Further study is warranted to evaluate long term tissue remodeling and graft feasibility in detail.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01-HL098228 to Dr. Breuer). Dr. Sugiura was the recipient of a funding award from Kanae Foundation for the Promotion of Medical Science (Tokyo, Japan) and from Astellas Foundation for Research on Metabolic Disorders (Tokyo, Japan) in 2013. Drs. Tara and Kurobe were recipients of the Banyu Fellowship from Banyu Life Science Foundation International (Tokyo, Japan) (HK in 2011 and ST in 2012). Dr. Kurobe was the recipient of a fellowship from Shinsenkai Imabari Daiichi Hospital (Ehime, Japan) in 2013.

Footnotes

Drs Breuer and Shinoka discloses a financial relationship with Gunze Ltd. (Kyoto, Japan).

Disclosure Statement:

C.K.B and T.S receive grant support from Gunze Ltd. (Kyoto, Japan).

Presented at the Fifty-second Annual Meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, Phoenix, AZ, Jan 23–27, 2016.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Tara S, Rocco KA, Hibino N, et al. Vessel bioengineering. Circ J. 2014;78:12–9. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-13-1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kannan RY, Salacinski HJ, Butler PE, et al. Current status of prosthetic bypass grafts: a review. Journal of biomedical materials research Part B, Applied biomaterials. 2005;74:570–81. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmedlen RH, Elbjeirami WM, Gobin AS, et al. Tissue engineered small-diameter vascular grafts. Clin Plast Surg. 2003;30:507–17. doi: 10.1016/s0094-1298(03)00069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsumura G, Hibino N, Ikada Y, et al. Successful application of tissue engineered vascular autografts: clinical experience. Biomaterials. 2003;24:2303–8. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roh JD, Sawh-Martinez R, Brennan MP, et al. Tissue-engineered vascular grafts transform into mature blood vessels via an inflammation-mediated process of vascular remodeling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:4669–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911465107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shin’oka T, Matsumura G, Hibino N, et al. Midterm clinical result of tissue-engineered vascular autografts seeded with autologous bone marrow cells. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:1330–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hibino N, McGillicuddy E, Matsumura G, et al. Late-term results of tissue-engineered vascular grafts in humans. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:431–6. 6 e1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shin’oka T, Imai Y, Ikada Y. Transplantation of a tissue-engineered pulmonary artery. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:532–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102153440717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Z, Cui Y, Wang J, et al. The effect of thick fibers and large pores of electrospun poly(epsilon-caprolactone) vascular grafts on macrophage polarization and arterial regeneration. Biomaterials. 2014;35:5700–10. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.03.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tara S, Kurobe H, Rocco KA, et al. Well-organized neointima of large-pore poly(l-lactic acid) vascular graft coated with poly(l-lactic-co-epsilon-caprolactone) prevents calcific deposition compared to small-pore electrospun poly(l-lactic acid) graft in a mouse aortic implantation model. Atherosclerosis. 2014;237:684–91. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roh JD, Nelson GN, Brennan MP, et al. Small-diameter biodegradable scaffolds for functional vascular tissue engineering in the mouse model. Biomaterials. 2008;29:1454–63. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mattson DL. Comparison of arterial blood pressure in different strains of mice. Am J Hypertens. 2001;14:405–8. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(00)01285-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mirensky TL, Nelson GN, Brennan MP, et al. Tissue-engineered arterial grafts: long-term results after implantation in a small animal model. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:1127–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.02.035. discussion 32–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Junqueira LC, Bignolas G, Brentani RR. Picrosirius staining plus polarization microscopy, a specific method for collagen detection in tissue sections. Histochem J. 1979;11:447–55. doi: 10.1007/BF01002772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rocco KA, Maxfield MW, Best CA, et al. In vivo applications of electrospun tissue-engineered vascular grafts: a review. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2014;20:628–40. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEB.2014.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soletti L, Hong Y, Guan J, et al. A bilayered elastomeric scaffold for tissue engineering of small diameter vascular grafts. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:110–22. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu W, Allen RA, Wang Y. Fast-degrading elastomer enables rapid remodeling of a cell-free synthetic graft into a neoartery. Nat Med. 2012;18:1148–53. doi: 10.1038/nm.2821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rustad KC, Sorkin M, Levi B, et al. Strategies for organ level tissue engineering. Organogenesis. 2010;6:151–7. doi: 10.4161/org.6.3.12139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riha GM, Lin PH, Lumsden AB, et al. Review: application of stem cells for vascular tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:1535–52. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madden LR, Mortisen DJ, Sussman EM, et al. Proangiogenic scaffolds as functional templates for cardiac tissue engineering. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:15211–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006442107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bryers JD, Giachelli CM, Ratner BD. Engineering biomaterials to integrate and heal: the biocompatibility paradigm shifts. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2012;109:1898–911. doi: 10.1002/bit.24559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milleret V, Hefti T, Hall H, et al. Influence of the fiber diameter and surface roughness of electrospun vascular grafts on blood activation. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:4349–56. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen X, Wang J, An Q, et al. Electrospun poly(l-lactic acid-co-varepsilon-caprolactone) fibers loaded with heparin and vascular endothelial growth factor to improve blood compatibility and endothelial progenitor cell proliferation. Colloids and surfaces B, Biointerfaces. 2015;128:106–14. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2015.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang B, Akgun B, Lam RC, et al. A polymer-extracellular matrix composite with improved thromboresistance and recellularization properties. Acta biomaterialia. 2015;18:50–8. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]