Abstract

Nocardiosis is a serious complication of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha blockers. With the increasing use of biologics for inflammatory bowel disease, it is to be anticipated that opportunistic infections such as nocardia will be more frequently encountered in children. We present the case of a 16 year old male with Crohn’s disease who developed pulmonary nocardiosis during the course of his treatment with infliximab. This case illustrates the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges faced in patients with inflammatory bowel disease infected with opportunistic organisms. Pediatric health care providers need to be aware so that early diagnosis and treatment can be provided thereby preventing disseminated disease and having favorable outcomes. Although TNF blocker therapy must be discontinued in the presence of such infections, biologic therapy may be reintroduced after successful treatment with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole to control underlying symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease.

Introduction

A 16 year old male patient with Crohn’s disease was admitted with a two week history of fever, productive cough, dyspnea and chest pain. He was treated empirically with azithromycin, started a week prior, for a presumptive diagnosis of pneumonia.

The patient had been diagnosed with Crohn’s disease three years ago. He was treated with 500 mg tablets of mesalamine twice a day. He remained symptomatic, and oral 6-mercaptopurine, 50 mg once a day, was prescribed. The patient’s symptoms did not improve with the use of immunomodulators so biologic therapy with infliximab 5 mg once every eight weeks was advised. There was no other significant past medical or family history.

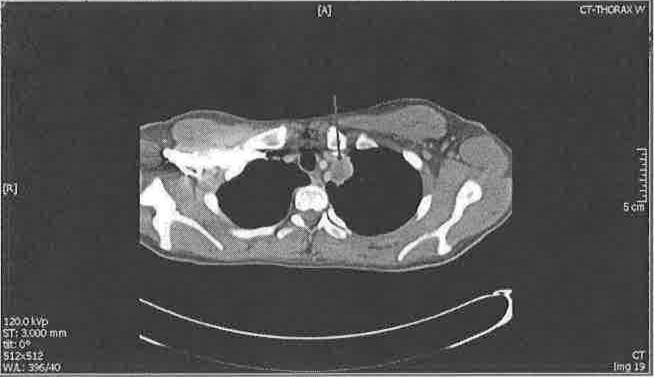

On admission, laboratory examination was significant for an elevated ESR and CRP. Routine culture for blood and sputum were negative. The stain for acid fast bacilli was also unremarkable. A chest radiograph performed revealed a 2 × 2 cm pulmonary nodule in the left anterior upper lobe (figure 1). A computerized tomography (CT) scan of the chest confirmed the presence of the nodule on the left anterior upper lobe, abutting the left carotid and subclavian artery with a central area of necrosis (figure 2). A biopsy of the nodule performed demonstrated necrotic material with questionable hyphae. Gram stain of the specimen was negative for any bacteria. Due to an Insufficient amount of specimen collection, fungal cultures for PCR and mycobacteria were not sent. The patient was empirically treated with broad-spectrum antifungal therapy; caspofungin and amphotericin B. The patient remained febrile despite treatment. Repeat CT scan demonstrated an increase in the size of the nodule to 2.7 × 2.2 cm with a central area of necrosis. Wedge resection of the lesion was performed and the specimen was sent for fungal and mycobacterial cultures, A PCR assay performed for aspergillus, histoplasmosis and blastomyces was also sent and was negative.

Figure 1.

Pulmonary nodule as seen on chest x-ray.

Figure 2.

CT scan of the chest demonstrating a pulmonary nodule.

N. pseudobrasilliensis was identified on fungal cultures. The patient was treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), 160 milligrams by mouth, twice daily for six months. His respiratory symptoms improved on the third day of therapy, with complete resolution of the nodule on a follow up CT scan performed four months after initiation of therapy. During this hospitalization, the 6-mercaptopurine and infliximab were discontinued, but the patient remained on low dose corticosteroids. His gastrointestinal symptoms were managed by bowel rest and total parenteral nutrition during that time. However, his symptoms of Crohn’s disease recurred with colonoscopic demonstration of moderate to severe disease (Figure 3). Therefore, adallmumab 40mg subcutaneous injections were started six months later for the treatment of the underlying inflammatory bowel disease. To our knowledge, the patient has not had any more pulmonary symptoms upon reinitiation of biologic therapy.

Figure 3.

Colonoscopic images depicting the patient’s active Crohn’s disease.

Discussion

Nocardiosis is a serious complication that may result after treatment with TNF-alpha blockers.1 Hepatic, pulmonary, cutaneous and disseminated infections may result in patients treated with biologics for chronic conditions such as Crohn’s disease and psoriasis.1–4 Nocardiosis, specifically, has been reported in the literature in patients receiving infliximab for conditions such as Crohn’s disease, psoriasis, Sweet syndrome, and rheumatoid arthritis.1–8 (see Table 1). The individual in the case report with psoriasis eventually succumbed to the infection.1 Most of the other case reports describe full recovery with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole treatment, though sometimes after months to years of therapy. Most of these individuals were receiving therapy with another immunosuppressant, such as prednisone, as well. Pulmonary nocardiosis is usually caused by Nocardia asteroids whereas N. brasilliensis is often associated with cutaneous infections.9 There was one case report of liver abscess caused by Nocardia farcinica in an individual with Crohn’s disease on infliximab and steroids.7 Clinically, patients may present with symptoms of pneumonia or remain asymptomatic. Radiologically, non-specific pulmonary infiltrates, nodules, cavitations or a mass lesion may be seen.9

Table 1.

Summary of case reports of Nocardia infections in individuals receiving infliximab.

| Author, year | Concurrent therapy | Treatment | Patient demographics and course |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singh, et. al 2004 | prednisone | TMP-SMX | 45 year old male; complete healing of lesions in 4 years |

| Stratakos et. al, 2005 | Methylprednisolone | TMP-SMX | 77 year old female; resolution in 6 months |

| Parra et al; 2008 | Azathioprine and prednisone | TMP-SMX, amikacin, imipemem and fluconazole | 53 year old female; resolution in 6 months |

| Nakahara et al, 2011 | prednisone | TMP-SMX | 23 year old man; improved dramatically after antibiotic initiation |

| Ali, et al. 2013 | None reported | TMP-SMX | 61 year old male; resolution in 6 months |

Infliximab related immunomodulation increases the susceptibility in patients treated with biologics to opportunistic infections. This risk is further increased by concomitant therapy with corticosteroids or other immunosuppresants.4 The true incidence of infliximab related infections remains unknown. This in part may be related to the underreporting by healthcare providers since less than five percent of infliximab related infections are reported.4 High mortality makes early diagnosis and treatment crucial.1,3

N. brasiliensis is susceptible to treatment with TMP-SMX and aminoglycosides such as gentamicin, amikacin, and tobramycin. Improvement may be seen within 2–3 weeks after appropriate antibiotic therapy. If the patient remains febrile after a full course of appropriate antibiotic therapy, “treatment failure” should be considered. Poor antibiotic penetration into the abscesses is one of the main reasons impeding spontaneous recovery and may make surgical drainage necessary.2,4 Additionally, other reasons for treatment failure include resistant strains or concomitant infections with other organisms such as Aspergillus.

Our patient showed a favorable response to therapy with TMP-SMX. In addition, he has remained asymptomatic despite treatment with adalimumab 40mg subcutaneous injections once every two weeks. It is likely that exposure to corticosteroids, 6-mercaptopurine, and subsequently infliximab increased the patient’s immunosuppression and susceptibility to infection.

This case was further complicated by a sampling error and thus highlights the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges faced in patients with inflammatory bowel disease infected with opportunistic organisms. In many of the cases described, biologics were restarted without incident status post treatment for Nocardiosis. Thus, once treated patients can likely be safely treated again with biologic therapy once the pulmonary infection is treated appropriately with antibiotics.

Conclusion

Early recognition and treatment are necessary for prevention of disseminated disease and favorable outcomes in children with inflammatory bowel disease diagnosed with pulmonary nocardiosis. Heath care providers should be aware when presented with a child on TNF blocker therapy. Once treated, biologic therapy can be reintroduced to control underlying symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease.

Contributor Information

Rishi Verma, Resident, Department of Pediatrics, Charleston Area Medical Center.

Ritu Walia, Assistant Professor, Pediatrics, Pediatric Gastroenterology, West Virginia University, Charleston Division.

Stephen B. Sondike, Medical Director, Disordered Eating Center of Charleston (DECC), Section Head, Adolescent Medicine, Professor of Pediatrics, West Virginia University, Charleston Division.

Raheel Khan, Associate Professor, Pediatrics, Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Charleston Area Medical Center.

References

- 1.Al-Tawfiq JA, Al-Khatti AA. Disseminated systemic Nocardia farcinica infection complicating alefacept and infliximab therapy in a patient with severe psoriasis. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:e153–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parra MI, Martinez MC, Remacha MA, Saez-Nieto JA, Garcia E, Yague G, et al. Pneumonia due to Nocardia cyriacigeorgica in a patient with Crohn’s disease treated with infliximab. J Crohns Colitis. 2008;2:331–2. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh SM, Rau NV, Cohen LB, Harris H. Cutaneous nocardiosis complicating management of Crohn’s disease with infliximab and prednisone. Cmaj. 2004;171:1063–4. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1040563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stratakos G, Kalomenidis I, Papas V, Malagari K, Kollintza A, Roussos C, et al. Cough and fever in a female with Crohn’s disease receiving infliximab. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:354–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00005205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali T, Chakraburtty A, Mahmood S, Bronze MS. Risk of nocardial infections with anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Am J Med Sci. 2013 Aug;346(2):166–8. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3182883708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drone ER, McCrory AL, Lane N, Fiala K. Disseminated nocardiosis in a patient on infliximab and methylprednisolone for treatment-resistant Sweet’s syndrome. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014 Jul;5(3):300–2. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.137782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakahara TI, Kan H, Nakahara H, et al. A case of liver nocardiosis associated with Crohn’s disease while treating infliximab. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2011 Apr;108(4):619–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fabre S, Gibert C, Lechiche C, et al. Primary cutaneous Nocardia otitidiscaviarum infection in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab. J Rheumatol. 2005 Dec;32(12):2432–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ambrosioni J, Lew D, Garbino Jorge. Nocardiosis: updated clinical review and experience at a tertiary center. Infection. 2010;38(2):89–97. doi: 10.1007/s15010-009-9193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]