Abstract

Patient: Female, 42

Final Diagnosis: Spontaneous pelvic-abdominal peritonitis due to actinomyces

Symptoms: Abdominal distension • abdominal pain • acute abdomen • fever • intermenstrual bleeding • nausea • sepsis • septic shock

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Surgery

Objective:

Unusual clinical course

Background:

Pelvic-abdominal actinomycosis is a rare chronic condition caused by an anaerobic, gram-negative rod-shaped commensal bacterium of the Actinomyces species. When Actinomyces becomes pathogenic, it frequently causes a chronic infection with granulomatous abscess formation with pus. Due to diversity in clinical and radiological presentation, actinomycosis can easily be mistaken for several other conditions. Peritonitis without preceding abscess formation caused by Actinomyces species has been described in only few cases before in literature.

Case report:

We report a case of spontaneous pelvic-abdominal peritonitis with presence of pneumoperitoneum and absence of preceding abscesses due to acute actinomycosis mimicking a perforation of the proximal jejunum in a 42-year-old female with an intra-uterine contraceptive device in place. Explorative laparotomy revealed 2 liters of odorless pus but no etiological explanation for the peritonitis. The intra-uterine contraceptive device was removed. Cultivation showed growth of Actinomyces turicensis. The patient was successfully treated with penicillin.

Conclusions:

In the case of primary bacterial peritonitis or lower abdominal pain without focus in a patient with an intrauterine device in situ, Actinomyces should be considered as a pathogen.

MeSH Keywords: Actinomycosis; Contraceptive Devices, Female; Genital Diseases, Female; Peritonitis; Sepsis

Background

Actinomyces species are facultative anaerobic, non-acid fast, Gram-positive and rod-shaped bacteria. These bacteria are difficult to identify and cultivate, because they tend to grow slowly and require optimal conditions. Cultivated growth of Actinomyces can be expected after a period of 5 to 21 days [1–3] and in more than 50% of assumed actinomycosis cases there is no growth of the species found at all [2]. Actinomyces bacteria are part of the commensal flora in the oropharynx, gastrointestinal tract, and female urogenital tract [1–5]. An endogenous infection can arise after erosion of the mucosa followed by invasion and pathogenicity of these bacteria [1–3]. This infection, known as actinomycosis, should be interpreted as a chronic condition that frequently causes granulomatous abscess formation with pus. Subsequently it can lead to necrosis, fibrosis and adhesions with surrounding structures or draining sinuses [1,2,4–8]. Because of diversity in both clinical and radiological presentation, actinomycosis can easily be misinterpreted for several other conditions. Predominantly malignant lesions, but misinterpretations for infectious diseases such as appendicitis, diverticulitis, inflammatory bowel disease, pelvic inflammatory disease, and mass-forming infectious diseases as tuberculosis are described as well [1–4,7–10].

A spontaneous peritonitis caused by Actinomyces without signs of preceding abscess or mass formation is described only twice in the literature [5,11]. We describe a third case of spontaneous peritonitis caused by Actinomyces without preceding abscesses.

Case Report

A 42-year-old female patient (gravidity 1, parity 1) was presented at our Emergency Department with progressive diffuse abdominal pain. Several weeks prior to presentation she noticed vague abdominal pain and altered vaginal discharge, which both resolved spontaneously. The patient had a copper intra-uterine device (IUD) in situ during the last 5 years and had a regular menstrual cycle.

A week before presentation at the Emergency Department, the patient had noticed an increase in lower abdominal pain, inter-menstrual bleeding, and pollakisuria the preceding day. A urine dipstick analysis was suspicious for a urinary tract infection. The general practitioner started the patient on nitrofurantoin for 5 days. During the following days, the patients’ symptoms worsened and she had fever of 39°C despite the use of NSAIDs and acetaminophen.

Eight days after the inter-menstrual bleeding, the patient presented at our hospital with clinical signs of an acute abdomen and septic shock. Physical examination revealed a body temperature of 36.2°C, a blood pressure of 70/40 mmHg, a pulse rate of 119 beats per min, and a respiratory frequency of 20 per min. She complained of diffuse abdominal pain, nausea, abdominal distension with signs of peritoneal irritation, and right-sided shoulder pain. Blood tests (Table 1) revealed increased infection parameters (C-reactive protein 436.8mg/L, leucocytes 13.5×109/L, with a differentiation of rods 45%, segments 37%), the first signs of metabolic acidosis (arterial values: pH 7.41, pCO2 3.7 kPa, pO2 10 kPa, O2 saturation 93.5%, bicarbonate 17.1 mmol/L, base Excess −6.2 mmol/L, venous values: lactate 2.7 mmol/L), liver value abnormalities (total bilirubin 42 μmol/L, ASAT 78 μ/L, ALAT 136 μ/L, alkalic phosphatase 250 μ/L, γ-GT 256 μ/L) and acute kidney injury (creati-nine 149 μmol/L). The symptoms, vital parameters, and blood results worsened in the following hours.

Table 1.

Outcomes of the first laboratory analyses obtained at the emergency department.

| First blood results |

| C-reactive protein: 436.8 mg/L, Leucocytes 13.5×109/L, with a differentiation of: metamyelocyte 11%, rods 45%, segments 37%, lymphocytes 4%, monocytes 3%. |

| Serum ureum 7.0 mmol/L, creatinine 149 μmol/L, estimated glomerular filtrating rate 33 mL/min/m, total bilirubin 42 μmol/L, glucose 9.3 mmol/L, ASAT 78 μ/L, ALAT 136 μ/L, alkalic phosphatase 250 μ/L, g-GT 256 μ/L, lactate 2.7 mmol/L |

| Arterial blood values |

| pH 7.41, pCO2 3.7 kPa, pO2 10 kPa, O2 saturation 93.5%, bicarbonate: 17.1 mmol/L, base Excess −6.2 mmol/L |

| Urine testing |

| Urine: leuko ++, albumine ++, glucose: -, hemoglobine ++, beta-hCG: – |

| Urine sediment |

| Leucocytes 827/μL, erythrocytes 109/μL, lots of bacteria, mucus and epithelium |

Ultrasound imaging of the abdomen showed diffuse “cloudy” fluid collections intra-abdominal, perihepatic, and in the pelvic area, as well as dilated bowels with signs of a paralytic ileus. Differential diagnosis at this point was a perforated appendicitis.

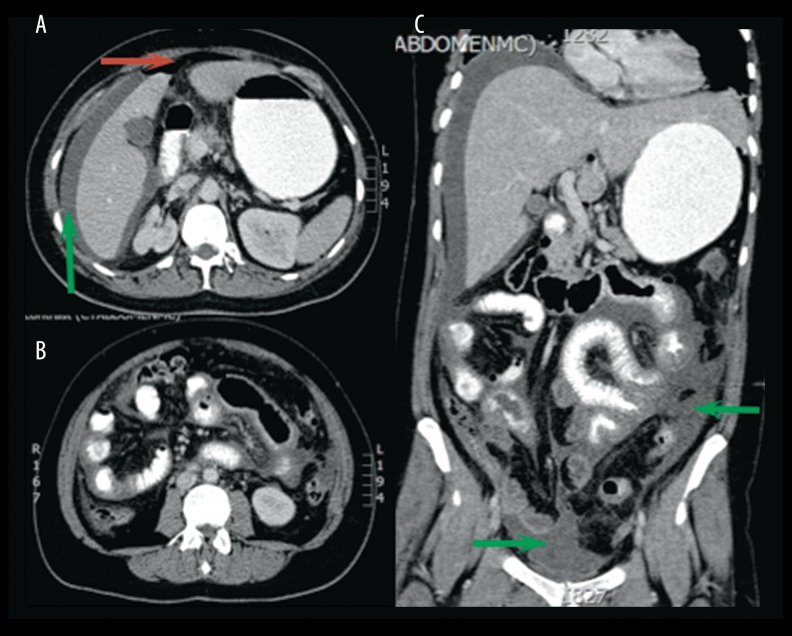

A CT scan with oral and intravenous contrast showed free fluid intra-abdominally, around the liver, and in the pelvic area (Figure 1). There was intra-abdominal free air visible in the portocaval area and around the proximal jejunum, which had a thickened wall. The appendix was not visible and the kidneys and genital organs showed no abnormalities; the IUD was in place. There was no lymphadenopathy. Presumptive diagnosis based on the CT scan was a perforation of the proximal jejunum.

Figure 1.

Transverse (A, B) and coronal (C) CT scan with oral and intravenous contrast of the abdomen showing intra-abdominal free fluid, especially perihepatic, proximal jejunum, and in the pelvic area. There is air visible in the portocaval area and extraluminal around the thickened proximal jejunum. Indicating marks: red arrow shows pneumoperitoneum and green arrow shows free pelvic-abdominal fluids.

Because of deterioration of clinical condition and a strong suspicion of a perforation of the proximal jejunum, an explorative laparotomy was performed to find the source of the peritonitis. Per-operatively, 2.5 L of odorless purulent pus was drained. The bowel was run through the entire length and the appendix was visualized, but no perforation or any other etiological explanation for this peritonitis could be found; therefore, it was considered a primary peritonitis. The combination of free fluids in the pelvic area and the IUD in situ warranted inspection by a gynecologist during surgery. The gynecologist noted no possible causes for the peritonitis and removed the IUD.

Pus samples, peripheral blood, and the IUD were sent for culture. A cervical smear was obtained. Postoperatively the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit, where she was stabilized and started on antibiotic treatment for spontaneous abdominal peritonitis (ceftriaxone, gentamicin, and metronidazole). Additional cervical smear PCR for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoea were negative.

For 2 weeks there was little clinical improvement. Inflammation parameters were fluctuating. Due to recurrent fluid collections, we performed 2 therapeutic paracenteses. After 2 weeks the cultures showed Actinomyces spp (cervical culture), while the other cultures showed anaerobic flora, but no Enterobacteriaceae. The diagnosis of pelvic-abdominal actinomycosis was thus made. Antibiotic treatment was switched to intravenous penicillin 6 times a day, 2 million units for 4 weeks and metronidazole 3 times a day 500 mg for 14 days. After switching antibiotics, clinical improvement occurred and infection parameters decreased. Oral antibiotics were continued for another 6 months thereafter.

Discussion

The pelvic-abdominal region is the second most frequent localization of actinomycosis [2–4,9]. Acute peritonitis caused by actinomycosis is rare and in some cases are described as the result of perforation of an Actinomyces abscess [12]. However, primary pelvic-abdominal peritonitis caused by Actinomyces without abscess formation is extremely rare and is reported only twice in the literature [5,11]. Our case differs from these 2 other cases because of the presence of pneumoperitoneum and an IUD as a possible source for this infection.

When Actinomyces becomes pathogenic, it probably infiltrates tissues by releasing proteolytic enzymes and causes an acute infection. During this acute phase, a cellulitic reaction without fibrosis occurs [8,9,13]. The bacteria spread continuously, not following anatomical tissue borders [3,4,6,9]. The infection slowly develops into an indurated granulomatous suppu-rating abscess with sulphur granules, branching “woody” aspect fibrosis, or draining sinuses and fistulas into surrounding structures [1,3,4,6,8,9].

Co-pathogenic bacteria are often involved [1,4]. Actinomycosis is generally discovered after a prolonged time when the characteristic abscesses have formed. Symptoms are non-specific and vary from no complaints at all to pain and widespread infection [14]. Most common are lower abdominal pain, fever, weight loss, or complications caused by the abscess. Abscess formation caused by Actinomyces is frequently described in the female genital tract and may lead to secondary peritonitis [6,7]. Pelvic actinomycosis is easily confused with ovarian cancer due to the presentation [1].

In our patient, despite a high suspicion of perforation based on CT imaging with intra-abdominal free air present, no perforation was found during laparotomy. The absence of Enterobacteriaceae in all cultures made a perforation even less likely. Although intralesional gas formation in actinomycosis has previously been reported in the literature, the cause of the pneumoperitoneum in our patient remains unclear [13,15–17]. Actinomyces species or concomitant bacteria may both produce gas in these rare forms of actinomycosis, but Sasaki et al. reported that “intralesional” gas is specific to osteomyelitis caused by Actinomyces [15]. Signs of bowel wall thickening on CT scan images are common in actinomycosis of the abdomen and there is generally a mass with an infiltrative aspect nearby [10].

Associations between actinomycosis and altered vaginal discharge, abnormal vaginal bleeding in combination with lower abdominal pain, and an IUD are common [1,2,6,18]. The association between primary peritonitis and IUD usage has been reported before, indicating that in females with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, the genital bacterial flora may be considered as a potential source of infection [19]. The use and implantation of an IUD could cause an asymptomatic chronic anaerobic endometritis in which Actinomyces species and other anaerobic bacteria grow well. It may eventually lead to an ascending infection from the cervix and uterus through the fallopian tubes into the peritoneal cavity [12,14,19]. This transfallopian route is also reported in healthy, sexually active females with Group A Streptococci, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Neisseria gonorrhoea [19,20]. Biofilm formation on foreign bodies could be a possible facilitating factor in development of actinomycosis [1].

The management of actinomycosis is generally conservative with antibiotic treatment. Actinomycosis is treated with intravenous high-dose penicillin for 2–4 weeks followed by oral antibiotics for at least 2–6 months [1,2,4,6,7,9] to avoid recurrence [1]. Frequently, other bacteria are cultured as well. Their treatment depends on culture results, sensitivity, and drainage. Surgical removal of infected tissue is not indicated as a first-choice therapy but could aid in curation, and is necessary in complicated forms of actinomycosis [1–3,8] such as in our case. In reality, most cases of pelvic-abdominal actinomycosis are diagnosed after surgery based on culture results of removed tissue [2,7,14,18].

Conclusions

Our case differs from most by the combination of 2 rarely described occurrences in actinomycosis – the presence of pneumoperitoneum and the absence of the characteristic abscesses. In the case of primary bacterial peritonitis or lower abdominal pain without focus in a patient with an IUD in situ, Actinomyces should be considered as a pathogen. Prompt initiation of antibiotics may reduce the need for surgical therapy; however, in reality, most cases of pelvic-abdominal actinomycosis are diagnosed after surgery has been performed.

Footnotes

Statement

No grants to report. The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Russo TA. Agents of actinomycosis. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, editors. Mandell, Douglas and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2015. pp. 3864–73. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valour F, Sénéchal A, Dupieux C, et al. Actinomycosis: Etiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and management. Infect Drug Resist. 2014;7:183–97. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S39601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong VK, Turmezei TD, Weston VC, et al. Actinomycosis. BMJ. 2011;343:d6099. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d6099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brook I. Actinomycosis: Diagnosis and management. South Med J. 2008;101:1019–23. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181864c1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flores-Franco RA, Lachica-Rodriguez GN, Banuelos-Moreno L, et al. Spontaneous peritonitis attributed to actinomyces species. Ann Hepatol. 2007;6:276–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiorino AS. Intrauterine contraceptive device-associated actinomycotic abscess and Actinomyces detection on cervical smear. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:142–49. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00350-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagenlehner FME, Mohren B, Naber KG, et al. Abdominal Actinomycosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9:881–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2003.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown JR. Human Actinomycosis. A study of 181 subjects. Hum Pathol. 1973;4:319–30. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(73)80097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bennhoff DF. Actinomycosis: Diagnostic and therapeutic considerations and a review of 32 cases. Laryngoscope. 1984;94:1198–217. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198409000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee IJ, Ha HK, Park CM, et al. Abdominopelvic actinomycosis involving the gastrointestinal tract: CT features. Radiology. 2001;220:76–80. doi: 10.1148/radiology.220.1.r01jl1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hiremath S, Biyani M. Actinomyces peritonitis in a patient won continuous cycler peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2006;26:513–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lomax CW, Harbert GM, Jr, Thornton WN., Jr Actinomycosis of the female genital tract. Obstet Gynecol. 1976;48:341–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kemp FH, Vollum RL. Anaerobic cellulitis due to Actinomyces, associated with gas production. Br J Radiol. 1946;19:248. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-19-222-248. [Abstract] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi MM, Beak JH, Lee JN, et al. Clinical features of abdominopelvic Actinomycosis: Report of twenty cases and literature review. Yonsei Med J. 2009;50:555–59. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2009.50.4.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sasaki Y, Kaneda T, Uyeda JW, et al. Actinomycosis in the mandible: CT and MR findings. Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;35:390–94. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moriwaki K, Sakata Y, Kato T, et al. [Report of two cases of actinomycosis of the neck, one acute and one chronic] Nihon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho. 2000;103:1238–41. doi: 10.3950/jibiinkoka.103.1238. [Abstract] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Navas E, Martinez-San Millán J, Garcia-Villanueva M, et al. Brain abscess with intracranial gas formation: case report. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:219–20. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.1.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuda K, Nakajima H, Khan KN, et al. Preoperative diagnosis of pelvic actinomycosis by clinical cytology. Int J Womens Health. 2012;4:527–33. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S35573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brinson RR, Kolts BE, Monif GR. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis associated with an intra uterine device. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;8:82–84. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198602000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moskovitz M, Ehrenberg E, Grieco R, et al. Primary peritonitis due to group a streptococcus. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:332–35. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200004000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]