Significance

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) are pentameric ligand-gated ion channels involved in fast neurotransmission. Here, we present the crystal structure of the homopentameric assembly of the extracellular domain (ECD) of α2 nAChR subunit in complex with an agonist. The structure provides a unique opportunity to probe the interactions involved in the formation of the ligand binding site of a WT nAChR and their role in stabilizing an agonist. Furthermore, functional studies revealed the role of additional residues in the activation and desensitization of the α2β2 nAChRs. High sequence identity of α2 ECD with other neuronal subunits signifies the importance of the structure as a template for modeling several neuronal nAChR ECDs and for designing nAChR subtype-specific drugs against related diseases.

Keywords: cys-loop receptors, α2β2 nAChR, X-ray crystallography, ligand-gated ion channel

Abstract

In this study we report the X-ray crystal structure of the extracellular domain (ECD) of the human neuronal α2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) subunit in complex with the agonist epibatidine at 3.2 Å. Interestingly, α2 was crystallized as a pentamer, revealing the intersubunit interactions in a wild type neuronal nAChR ECD and the full ligand binding pocket conferred by two adjacent α subunits. The pentameric assembly presents the conserved structural scaffold observed in homologous proteins, as well as distinctive features, providing unique structural information of the binding site between principal and complementary faces. Structure-guided mutagenesis and electrophysiological data confirmed the presence of the α2(+)/α2(−) binding site on the heteromeric low sensitivity α2β2 nAChR and validated the functional importance of specific residues in α2 and β2 nAChR subunits. Given the pathological importance of the α2 nAChR subunit and the high sequence identity with α4 (78%) and other neuronal nAChR subunits, our findings offer valuable information for modeling several nAChRs and ultimately for structure-based design of subtype specific drugs against the nAChR associated diseases.

Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) are located mainly in the CNS and mediate fast neurotransmission. They are implicated in various neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s (1) and Parkinson’s (2) diseases, substance addiction (3), epilepsy (4), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (5), and depression (6); thus, drug development for these receptors is a priority (7). They belong to the Cys-loop superfamily of pentameric ligand-gated ion channels (pLGIC), which includes γ-aminobutyric acid (GABAA and GABAC), glycine, and serotonin (5-HT3) receptors (8). The neuronal nAChR subfamily consists of numerous homomeric and heteromeric pentameric assemblies, formed by α (α2-α10) and β (β2-β4) subunits, distributed ubiquitously in the brain (9). Because of their considerable homology, especially in their binding sites, designing a novel drug specific for one type of nAChR can be a challenging procedure and requires the addition of more structural information. Following this need, structural studies of the nAChR have been the focus of numerous laboratories, leading to the achievement of many breakthroughs, such as the cryo-electron microscopy structure of the Torpedo nAChR (10) and the X-ray crystal structures of acetylcholine binding proteins (AChBPs; homologs of the ECD of nAChR) (11–13), mouse muscle-type α1 and human neuronal α9 nAChR ECDs (14, 15), GLIC and ELIC (two prokaryotic homologs of pLGICs) (16, 17), and two α7 nAChR ECD–AChBP chimeras (18, 19). In addition, the structures of other members of the superfamily have recently become available, including that of an invertebrate anionic glutamate receptor (20), the human GABAA β3 (21), the mouse 5-HT3 receptor (22), the human α3 glycine receptor (23), and the zebrafish α1 glycine receptor (24).

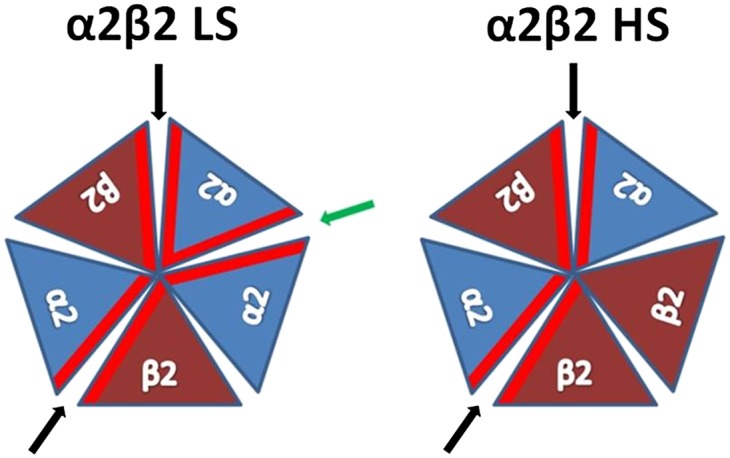

The α2 subunit is incorporated in heteropentameric neuronal nAChRs mainly with β subunits and along with the α4 and β2 is one of the main nAChR subunits expressed in primates’ brain (25). However, α2 containing nAChRs are not thoroughly studied compared with other nAChR subunits, partly because the α2 nAChR ortholog presents a restricted expression profile in rodents' brain in contrast to what is observed in primates' brain (26). In a similar fashion to α4β2 nAChR, it has been shown that in heterologous expression in Xenopus laevis oocytes, two subtypes of α2β2 nAChR are formed with either low or high agonist sensitivity (LS or HS, respectively) (27). In the case of α4β2 nAChRs, the LS and HS subtypes display differential ligand specificity, unitary conductance and desensitization kinetics (28). It has been shown that these differences originate from the altered stoichiometry, since the LS subtype has, in addition to the α4(+)/β2(-) ligand binding sites, another one at the α4(+)/α4(−) interface (29). To emphasize the possible clinical significance of the two subtypes, it has been shown that the stoichiometry of the α4β2 nAChR can be altered by chronic nicotine exposure (28, 30, 31) or by mutations (32). Similarly to the α4β2 nAChRs, it has been speculated that the two α2β2 subtypes differ in the stoichiometry of the α2 and β2 subunits, with the LS subtype having (α2)3(β2)2 and the HS subtype (α2)2(β2)3 stoichiometry (27). Both subtypes have two identical agonist binding sites (between α2 principal face and β2 complementary face). However, the LS subtype presents an additional interface between the two α2 subunits (Fig. S1).

Fig. S1.

Schematic presentation of the α2 and β2 subunits arrangement in α2β2 nAChR LS and HS subtypes. The α2(+)/β2(−) binding interface is pointed with black arrow and the α2(+)/α2(−) binding interface with green. The α2 and β2 subunits are presented in blue and brown triangles, respectively. The binding interfaces of each subunit are highlighted in red.

Recently, we revealed the crystal structures of the ECD of the human α9 nAChR subunit in its free and antagonist-bound states (15), whereas the structure of another ECD nAChR subunit, α1, was also solved earlier by others (14). However, crystal structures of pentameric assemblies of nAChR (ECD or intact) have not been determined so far, since both α1 and α9 ECD structures, although in high resolution, depicted the nAChR ECDs in monomeric forms.

Here we present the crystal structure of the ligand-induced pentameric assembly of α2 nAChR ECD in complex with the agonist epibatidine. This structure is the first structure of the assembly of a neuronal nAChR ECD where the complementary face of the binding site participates. The overall structure presents the conserved scaffold seen in the family but reveals additional molecular interactions on the inter- and intrasubunit level. Moreover, based on structure-guided mutagenesis, we present functional studies that evaluate the importance of the conserved Trp84 of loop D on α2β2 nAChR activation and desensitization, which in turn validates the α2(+)/α2(−) binding site of the LS subtype. Furthermore, we assess the role of α2 Tyr199 and the corresponding amino acid of the β2 subunit (Phe169), both located on loops F, on the activation of the LS and HS subtypes of α2β2 nAChRs. In addition to the importance of these data in understanding the role of α2 nAChR subunit, it is worth noting that, because the α2 ECD shares 78% sequence identity with the α4 ECD and 39–62% with the other neuronal nAChR α and β ECDs, its pentameric structure is an invaluable template for modeling several neuronal nAChR ECDs and for designing nAChR subtype-specific drugs against related diseases.

Results

Expression and Crystallization.

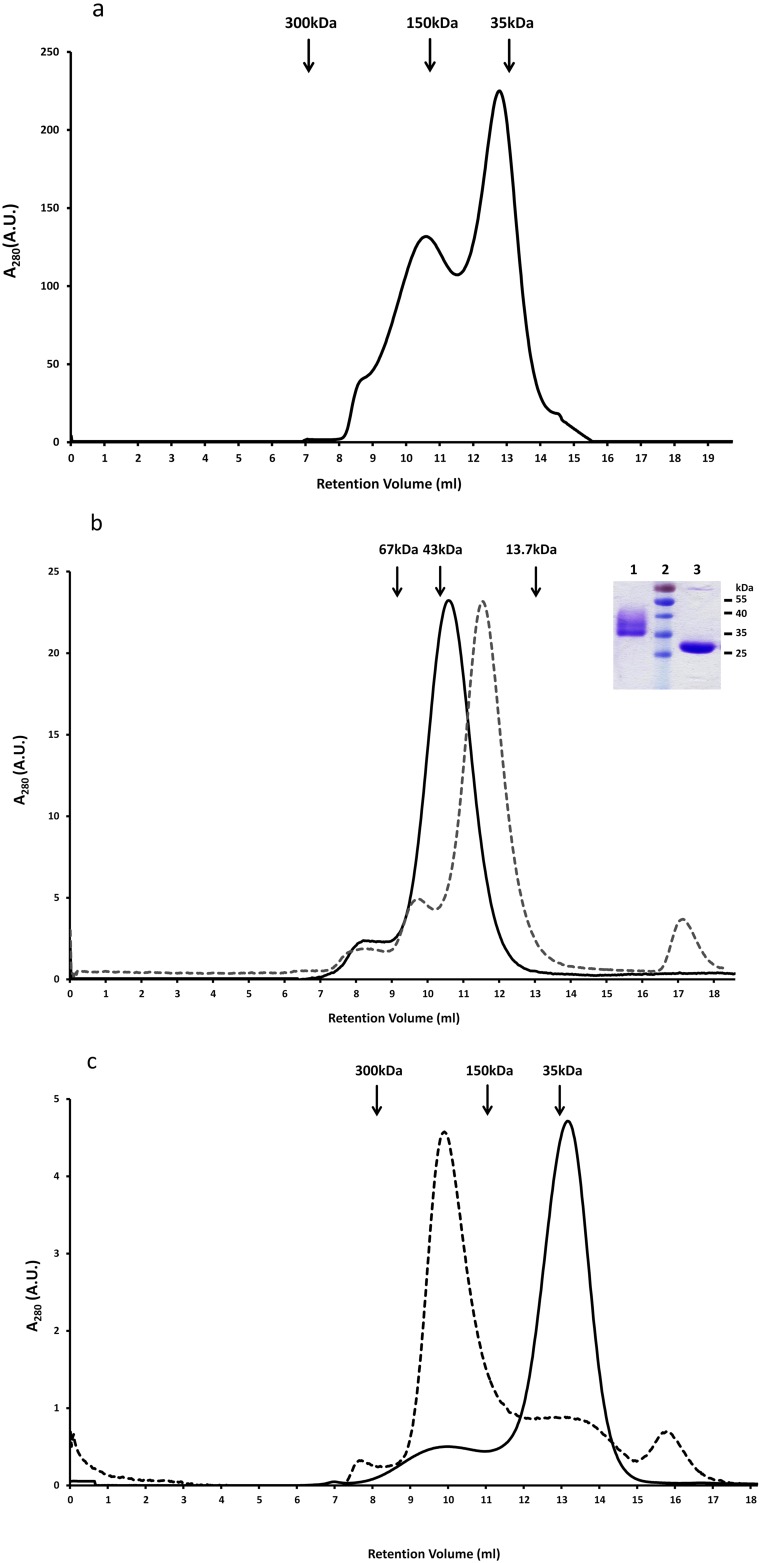

We expressed the human α2 ECD in yeast Pichia pastoris and gel filtration chromatographs revealed that the protein was eluted mainly in two peaks corresponding to high-molecular-weight oligomers and to monomers (Fig. S2A). Crystallization trials of the monomer produced small crystals that diffracted poorly. To improve diffraction quality, the monomer was deglycosylated and purified further by gel filtration (Fig. S2B). Crystallization trials of the deglycosylated monomer proved not successful as the protein precipitated easily even at low concentrations. Coincubation of the deglycosylated monomeric α2 ECD with various ligands for 14 d revealed that epibatidine could induce oligomerization of the α2 ECD with a molecular mass similar to a pentamer, as deduced by gel filtration analysis (Fig. S2C). Shorter incubation periods were not sufficient for oligomerization or epibatidine binding, thus prohibiting binding studies with radiolabeled ligands. Finally, crystallization trials of the complex of deglycosylated α2-ECD with epibatidine led to the successful production of diffraction quality crystals and to the elucidation of the X-ray crystal structure of a pentameric state of the agonist-bound α2-ECD at 3.2 Å (Table S1), thereafter called α2-Epi structure.

Fig. S2.

Gel filtration analysis of human α2 nAChR ECD. (A) Human α2 ECD was expressed as a monomer (solid line below the second peak) and as oligomer (first peak) on a Superdex-200 size exclusion column. (B) Superposition of the size exclusion chromatographs on Superdex-75 of α2 ECD monomer (solid line) and its deglycosylated form (dashed line) after EndoHf treatment. SDS/PAGE analysis (Inset) showed molecular masses of 32 (glycosylated) and 28 kDa (deglycosylated), approximately (lane 1: glycosylated α2 ECD; lane 2: prestained protein ladder; lane 3: deglycosylated α2 ECD). Arrows indicate the elution peaks of protein markers of known molecular mass. (C) Superposition of the oligomeric form of the deglycosylated α2 ECD monomer in the presence (dashed line) or the absence (solid line) of epibatidine as shown on size exclusion chromatograph on Superdex-200.

Table S1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Data and statistics | α2-Epi |

| Data collection | |

| Space group | P212121 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 101.52, 116.56, 129.55 |

| α,β,γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 47.26–3.20 (3.37–3.20) |

| Rmerge/CC1/2 (%) | 0.09 (0.88)/99.9 (60.1) |

| I/σI | 18.2 (2.6) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (99.7) |

| Redundancy | 6.6 (7.0) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 47.26–3.20 |

| No. reflections | 26,037 (3,729) |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.223/0.308 |

| No. atoms | |

| Protein | 8584 |

| Ligand/ion | 70 |

| Water | 0 |

| B factors | |

| Protein | 95.76 |

| Ligand/ion | 88.10 |

| Water | — |

| RMSDs | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.012 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.85 |

Values in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell.

Overview of the Structure.

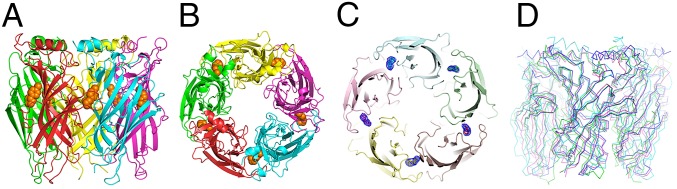

The overall structure presents the characteristic conserved pentameric quaternary structure of the Cys-loop superfamily with the epibatidine located at the interface between the subunits (Fig. 1 A–C). Each subunit presents a 10-stranded β-sandwich core capped by an N-terminal α-helix. As the α2 nAChR subunit has not been reported to form a functional homopentameric receptor, we first investigated whether the pentameric assembly of the α2 ECD upon ligand binding corresponds to the conserved counterpart seen in other homologous proteins. To address this issue, we compared the pentameric structure of α2 ECD with that of Ac-AChBP (13), the α7 ECD–AChBP chimera (18), both in complex with epibatidine, and of Torpedo nAChR (10) (Fig. 1D). Indeed, the β-sandwich core superimposes very well with the corresponding region of all of the above pentameric structures confirming that the ligand-induced pentameric assembly of the α2 ECD resembles the physiological ECD of the native nAChRs. Specifically, by superimposing the rigid secondary structure elements, the RMSD between α2-Epi and α7-AChBP chimera was found 0.902 Å, for the pair of α2-Epi and Ac-AChBP was 1.100 Å, and for the pair α2-Epi and Torpedo α1 subunit was 2.212 Å. Nevertheless, the binding and functional loops of the α2 ECD pentamer showed different trajectories, most likely due to sequence differences and their intrinsic flexibility. Particularly, the spatial arrangements of loop F, postloop A region, and α1-β1 linker showed high deviation among the compared structures (Fig. 2). Interestingly, postloop A region in α2-Epi structure differs from the other structures in that it is placed away from the pore attracted via hydrophobic interactions by residues on β4 strand (Fig. 2 B and C).

Fig. 1.

Structure of the pentameric assembly of α2 nAChR ECD in complex with epibatidine and comparison with related structures. (A) Side view and (B and C) top view of the α2-Epi structure; each subunit is colored differently; the epibatidine molecule is shown in orange spheres (B) or by the 2Fo-Fc electron density contoured at 1.4-σ level (C). (D) Superposition of the α2-Epi structure (green) with α7-AChBP chimera (cyan), Ac-AChBP (magenta), both in complex with epibatidine and Torpedo nAChR (blue).

Fig. 2.

Backbone superposition of the α2-Epi structure (green) with homologous structures (cyan, for Ls-AChBP; magenta, for α7-AChBP chimera; red for Ac-AChBP), revealing the structural variability of (A) loop F region, (B) postloop A domain, and (C) α1-β1 linker.

Typically, the homopentameric assembly of α2 ECD would be expected to shape five binding sites analogous to those of α7 nAChR or AChBPs. Indeed, in α2-Epi structure, the ligand has a well resolved density in all binding sites (Fig. 1C), whereas loop C of all monomers is placed in a closed-in conformation, as expected, for engulfing an agonist (Fig. 1 B and C). On the whole, the α2-Epi structure portrays accurately a model of the pentameric quaternary structure of nAChR ECD, and more importantly, it has a credible physiological importance, especially with regard to the presented characterization of the α2(+)/α2(−) interface.

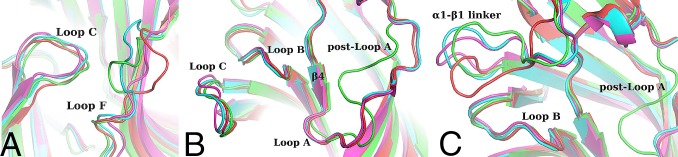

Architecture of the α2(+)/α2(−) Binding Site.

The ligand binding site of the α2-Epi structure is analogous to the conserved scaffold seen in AChBPs and other homologous pentameric complexes (10–13). The binding pocket is assembled by binding loops A, B, and C of the principal face and loops D, E, and F of the complementary face (Fig. 3A), which present an extensive interaction scheme. In particular, a hydrogen bond between the backbone amide of Lys182 (loop B) and the backbone carbonyl of Ile225 (loop C) that has been proposed to shape the aromatic box (33) of the ACh binding site is apparent in the α2-Epi structure as well (Fig. 3B). The variable residue at position 182 has been shown to be a key factor for the differentiation in the affinity of nicotine among α4β2, α7 and muscle nAChR (33, 34). The highly conserved Asp118 (β3-β4 linker) forms hydrogen bonds with another two highly conserved residues of loop B, Ser177 and Thr179 (Fig. 3C). This interdomain connection is also present on the α7 – AChBP chimera (18) and α9 ECD (15) and has been evaluated on muscle nAChR (35, 36) regarding its role on the agonist binding kinetics. Alongside, we can see the side chain of Tyr180 (principal side) to be in close proximity with the side chains of Lys136 (complementary side) and of Trp115 (principal side) (Fig. 3C). It is interesting to note here, that the corresponding to α2 Tyr180 residue in the structures of α1 and α9 ECDs, interacts with the equivalent residue to Trp115 of the same subunits (14, 15). The advent of the complementary subunit in the α2 ECD structure attracts the side chain of Lys136 toward Tyr180, thus adjusting the relative positions of loops B and E (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Loops and residues involved in the formation of the α2(+)/α2(−) binding site. (A) Close-up view of the binding site in the α2 Epi structure. Different colors are used to highlight loops A–F residing in two adjacent subunits. (B) Intrasubunit interaction (black dashed line) of Lys182 (loop B) and Ile225 (loop C) involved in ligand potency in nAChRs. Principal side backbone is colored in red, residues are shown in green sticks and epibatidine in white sticks. (C) Intrasubunit interaction of β3–β4 linker with loop B. Complementary side backbone is colored in cyan. (D) Intersubunit interactions involving the side chain of Arg108 (complementary side) and residues on loops B and C (primary side).

Additionally, another conserved amino acid, found in all neuronal nAChR subunits (except β3), involved in the shaping of the α2(+)/α2(−) binding site is Arg108 (Fig. 3D). The quanidinium group of Arg108 extends into the binding pocket just above loop B, participating in a complex interaction network, stabilizing the position of loop B close to the ligand (Fig. 3D). Particularly, the Nε interacts with the backbone carbonyl of Thr179, whereas one Nη interacts with the side chains of Tyr226 and Asp181. The side chain of the latter interacts with Glu224, thus closing the interaction network above loop B. Finally, the indole nitrogen of Trp178 acts as a hydrogen bond donor on the backbone carbonyl group of Val148, thus stabilizing the position of Trp178 (Fig. 4A).

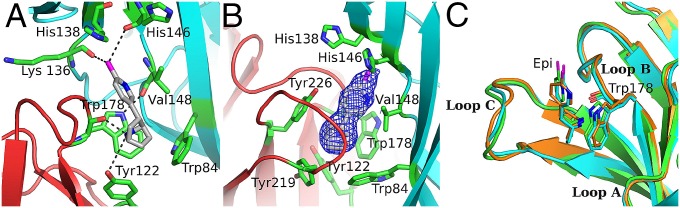

Fig. 4.

Epibatidine stabilization to the α2 ECD and comparison with homologous structures. (A and B) Close-up view of the aromatic cage. Residues are shown in green sticks, principal side backbone is colored in red and the complementary side is in cyan. Hydrogen bonds between residues and epibatidine are shown in black dashed lines (A), the 2Fo-Fc electron density contoured at 1.4-σ level attributed to epibatidine is shown in blue mesh (B). (C) Backbone superposition of a single subunit of α2 ECD (in green) with the other epibatidine-bound structures: α7-AChBP chimera (in cyan) and Ac-AChBP (in orange). Despite the similar conformation of loops A–C among the three structures, the epibatidine molecule (Epi) in α2-Epi structure is slightly rotated toward loop C. However, the overall binding motif is not altered.

Epibatidine Binding Recognition.

Epibatidine is enclosed in a position that favors the molecular interactions with both faces of the binding site. Its 7′-azabicyclo moiety occupies the space between the aromatic residues of the binding site, whereas the 2′-chloropyridine ring protrudes toward the apex of the binding pocket (Fig. 4 A and B). The central amine group is stabilized via a cation-π interaction with the aromatic ring of Trp178 of loop B and via a hydrogen bond with the main chain carbonyl group of the same tryptophan or the hydroxyl of Tyr122 of loop A (Fig. 4A). The chlorine atom stabilizes epibatidine further through its possible interactions with main chain carbonyl groups (Lys136 and His146 of the adjacent subunit), whereas the pyridine nitrogen remains in non–H-bond distance from the protein matrix.

A considerable number of van der Waals contacts complete the interacting scheme of the ligand. More specifically, the aliphatic side of the alicyclic domain interacts with Tyr219, Cys221, Cys222, and Tyr226 of loop C and Trp84, which is located on loop D of the complementary side, and was shown previously to be critical on the binding affinity of epibatidine to AChBPs (13, 18). The chloropyridine ring presents van der Waals interactions with Val148 on loop E and Thr179 on loop B (Fig. 4B). More importantly, the α2-Epi structure showed us the interactions of the ligand with amino acids that are key elements on the varied selectivity found in the nAChR family. Particularly, the side chains of His138 and His146 (loop D) are in close proximity with the epibatidine (Fig. 4 A and B). These positions have been shown to be important for the diverse ligand specificity seen in HS and LS subtypes of α4β2 nAChR (37, 38). Superposition of loops B and C of the α2-Epi structure with the corresponding loops of the epibatidine-bound structures of α7-AChBP chimera (18) and Ac-AChBP (13) reveals a lateral rotation of epibatidine toward Tyr226 by ∼8° (Fig. 4C). However, despite the local differences among the compared epibatidine-bound structures, the overall binding motif of epibatidine in the α2 ECD resembles those found in the homologous structures (Fig. 4C).

Functional Characterization of the α2(+)/α2(−) Binding Site.

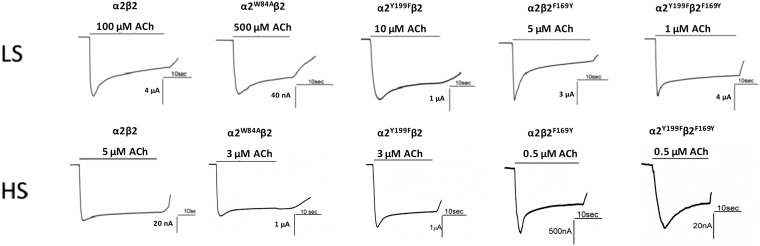

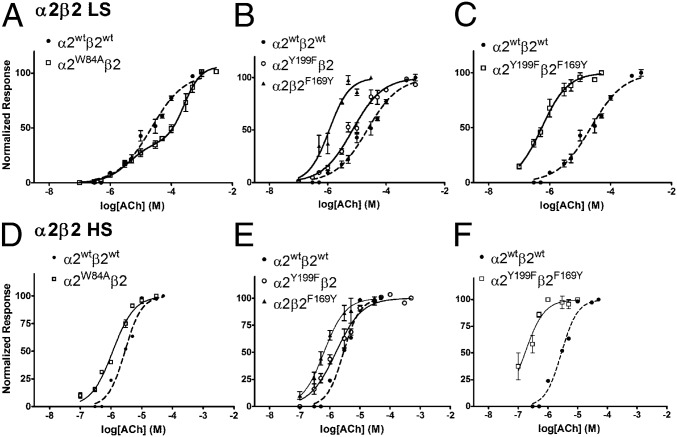

As the α2-Epi structure could serve as a structural surrogate of the α2(+)/α2(−) interface of the intact α2β2 nAChR, we determined critical residues and evaluated their functional role in nAChRs. For that reason, we constructed the α2 mutant W84A and coexpressed it in Xenopus oocytes with the β2 WT nAChR subunit in 10:1 or in 1:10 RNA ratios, thus expressing solely the LS or the HS subtype, respectively (27). Trp84 is a highly conserved residue on the complementary side of the ligand binding site that in the α2-Epi structure was found to interact with the ligand directly and its role in the binding site of other nAChRs has been evaluated in numerous studies (29, 39, 40) (Fig. 4 A and B). Mutating Trp to Ala on the α2 subunit would affect only the α2(+)/α2(−) interface as it is located on the complementary side of α2 and therefore not involved in the α2(+)/β2(−) interface. Indeed, ACh-evoked current recordings from RNA injected oocytes, by the use of the two electrode voltage-clamp technique (Fig. S3), produced a biphasic concentration response curve (Fig. 5A and Table S2), accompanied by a significant decrease (P < 0.05) in receptor desensitization compared with the WT (Table S3). The biphasic effect arises from the high and low sensitivity component. The high sensitivity component is appointed to the unaltered α2(+)/β2(−) interfaces, whereas the low sensitivity component is due to the impaired α2(+)/α2(−) interface (29). To the contrary, this mutation had no effect on either the EC50 or the desensitization kinetics of the α2W84Aβ2 HS subtype compared with the WT HS receptor (Tables S2 and S3 and Fig. 5D). Thus, the above findings demonstrate that the α2(+)/α2(−) interface forms functional binding site with Trp84 to be of major importance in ligand affinity and desensitization kinetics of the receptor subtype that bear the α2(+)/α2(−) interface, such as the LS one. This finding is consistent with the results of similar mutations on other homologous proteins (39, 41, 42) and particularly in the case of the α2β2 nAChR LS verifies the presence of the α2(+)/α2(−) binding site. Overall, our functional studies on the complementary side of the α2 subunit confirm the functional importance of the Trp84 and prove that it is the existence of an α2(+)/α2(−) binding site in the α2β2 LS subtype, that confers distinct binding and electrophysiological characteristics to this receptor subtype. Notably, a similar approach on the α4β2 nAChR had drawn analogous conclusions (29, 43).

Fig. S3.

Representative ACh-evoked current traces of voltage-clamped Xenopus oocytes expressing WT or mutants of α2β2 nAChRs. The traces shown correspond to ACh concentrations that evoked 75% (EC75) of the maximum current, whereas the duration of exposure is indicated with black bars above the traces.

Fig. 5.

Concentration-response curves of α2β2 nAChRs, WT and mutants, to ACh. (A–C) HS subtype and (D–F) LS subtype. The measurements were carried out in Xenopus laevis oocytes using two-electrode voltage–clamp electrophysiology. Peak current amplitudes were background subtracted and normalized to the amplitude evoked by 1 mM ACh on the same oocyte. Data points are presented as mean ± SEM.

Table S2.

EC50 values of ACh-evoked currents of the α2β2 nAChRs, WT and mutants, expressed in Xenopus oocytes

| Type | EC50_1 (µM) [95% CI] | EC50_ 2 (µM) [95% CI] | nH_1 | nH_2 | F (DFn,DFd) |

| LS | |||||

| α2β2 | 22.3 [17.3–28.7] | 0.81 ± 0.07 | |||

| α2W84Aβ2 | 4.06 [1.52–10.8] | 268 [187–385] | 1.10 ± 0.08 | 1.61 ± 0.44 | 31.5 (5,7) |

| α2Y199Fβ2 | 7.03 [5.60–8.82] | 0.85 ± 0.07 | |||

| α2β2F169Y | 1.12 [0.76–1.64] | 1.26 ± 0.25 | |||

| α2Y199Fβ2F169Y | 0.54 [0.47–0.61] | 1.02 ± 0.54 | |||

| HS | |||||

| α2β2 | 2.13 [1.51–2.53] | 1.60 ± 0.26 | |||

| α2W84Aβ2 | 1.23 [0.99–1.41] | 1.23 ± 0.12 | |||

| α2Y199Fβ2 | 1.74 [1.42–2.14] | 1.00 ± 0.09 | |||

| α2β2F169Y | 0.63 [0.57–0.70] | 1.21 ± 0.07 | |||

| α2Y199Fβ2F169Y | 0.17 [0.12–0.24] | 1.34 ± 0.26 | |||

EC50 values were determined by fitting the data to one or two-component sigmoidal dose–response equations. Only the α2W84Aβ2 LS mutant displayed biphasic behavior, and its Frac was 0.35. The F test (P < 0.0001) was used to compare the best fit of the equations. For more details, see SI Materials and Methods.

Table S3.

Time constants of the current decay were calculated at Ach concentrations that elicit 75% of Imax after fitting of the traces to one or two exponential decay function

| Type | LS [(α2)3(β2)2], τmean ± SEM (s) | HS [(α2)2(β2)3], τmean ± SEM (s) |

| α2β2 | τf = 2.63 ± 0.35*; τs = 40.17 ± 0.06 | τf = 8.48 ± 1.10*,†,‡ |

| α2W84Aβ2 | τf = 8.58 ± 2.35† | τf = 8.10 ± 1.16‡ |

P = 0.0023 this difference is statistical significant.

P > 0.5, this difference was not statistically significant.

Loops F of α2 and β2 Subunits Affect Differently α2β2 nAChR Activation.

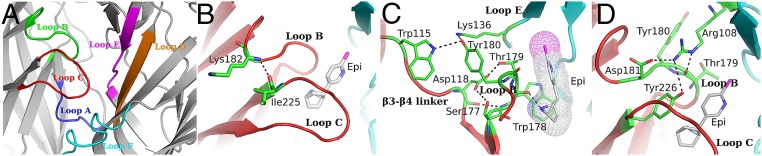

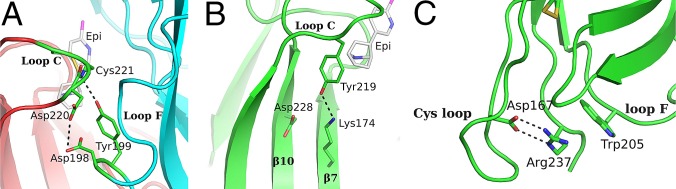

Comparing the α2-Epi structure to α7-AChBP chimera (18), Ac-AChBP (13), and Ls-AChBP (11), a notable observation emerges. On the α2-Epi and Ls-AChBP structures, loop F is placed much closer to loop C, whereas in α7-AChBP chimera and Ac-AChBP, loop F is comparatively further away (Fig. 2A). A closer look reveals that the tip of loop C interacts with Tyr199 of loop F of the complementary side (Fig. 6A and Fig. S4). This interaction is observed in three of five binding sites, whereas in the other two sites, loops F and C do interact, albeit rather less favorably and through other residues. It is also clear that this variation is not dependent on crystal packing contacts. Lacking the apo structure, it is difficult to predict the loop F position prior ligand binding. Nevertheless, on the apo structures of Torpedo (10) and AChBPs (12, 13), loop F seems to have a retracted position, closer to β9 strand, compared with the α2-Epi structure. Interestingly, at the corresponding position of 199 in α2, tyrosine is found only in α2, α3, and α7 nAChR subunits and Ls-AChBP, whereas in the other α and β subunits, is phenylalanine (Fig. S5). It is worth noting that in the α7-AChBP chimera structure in complex with epibatidine, loop F acquires a position similar to the position observed in apo structures and as a result, the analogous tyrosine residue, Tyr164, does not interact with loop C (18). Regardless, this interaction observed in the α2-Epi structure could have a variable role on ligand binding and thus on receptor activation. A similar role was attributed to Asp167 on the loop F of the γ and δ subunits of muscle nAChR (44–46).

Fig. 6.

Inter- and intrasubunit interactions implicated in gating and sensitivity of nAChRs. (A) Intersubunit interactions in α2-Epi structure involving residues of loops C and F, probably occurring due to the embrace of epibatidine by loop C. (B) An important interaction for the initial signal transduction in nAChRs was found in α2-Epi structure as well. Tyr219 on loop C interacts with Lys174 on β7 strand, whereas Asp228 on β10 strand probably escapes any interaction. (C) Close-up view of the membrane-facing loops. Crucial interactions for the gating of nAChRs between Arg237 and cys-loop and loop F residues are shown.

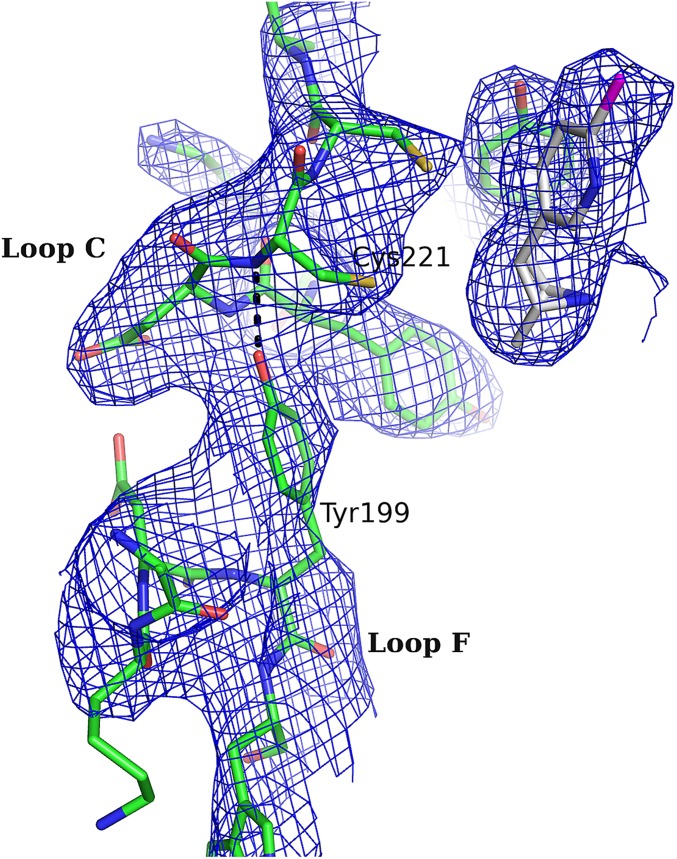

Fig. S4.

Close-up view of the interaction between loop F and the tip of loop C. The interaction is observed in three of five binding sites. The 2Fo-Fc electron density (contoured at 1.4-σ) shows the interaction of the side chain of Tyr199 with the tip of the loop C.

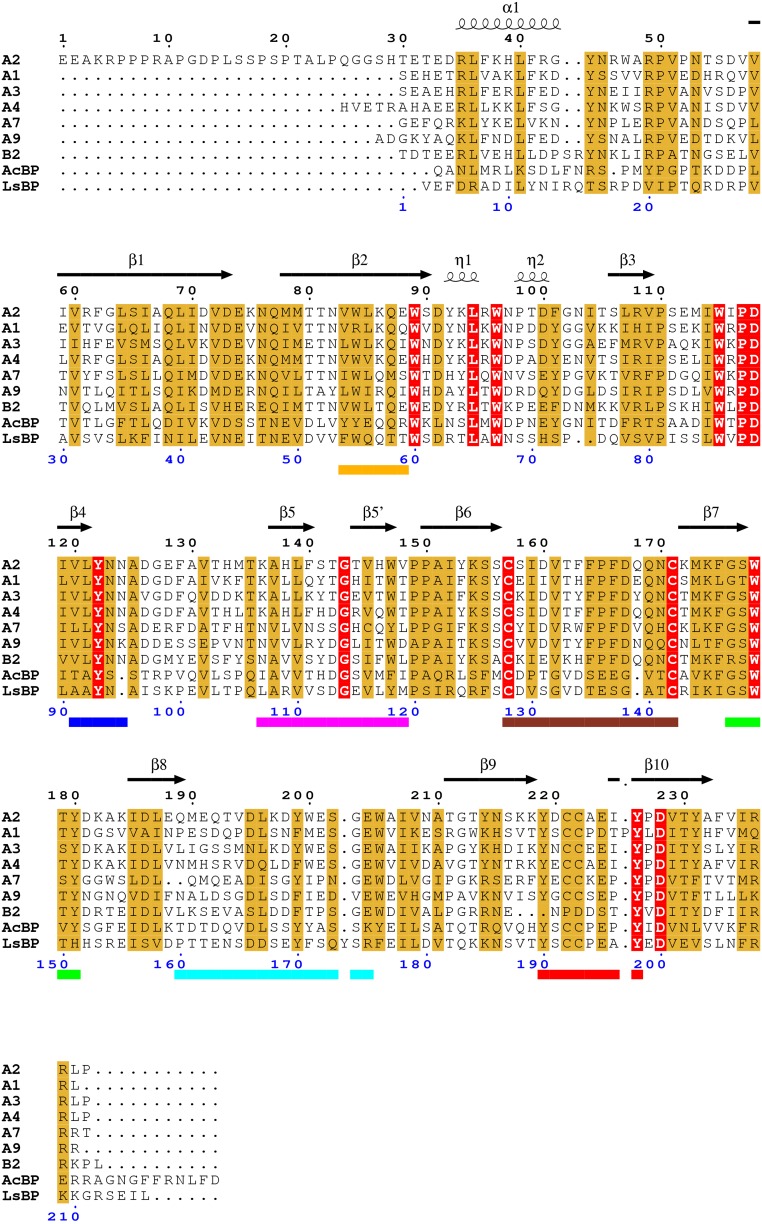

Fig. S5.

Sequence alignment of human α2 nAChR ECD with related nAChR sequences. (A and B for human α and β subunits, respectively; LsBP and AcBP is for Lymnaea stagnalis and Aplysia californica AChBPs, respectively). Secondary structure assignment is also shown for α2 ECD above the sequences. Loops A–F and Cys-loop are indicated by colored bars below sequences (blue for A; green for B; red for C; orange for D; magenta for E; cyan for F; brown for Cys-loop). Identical and similar residues are highlighted in red and light brown, respectively. Numbering starts from the first amino acid residue of α2 subunit (top, black) and of α1 subunit (bottom, blue).

To further establish this cooperation and in view of the fact that the β subunits have phenylalanine in that position, we substituted phenylalanine for Tyr199 on α2 subunit (α2Y199F) and the reverse on β2 subunit, namely, we substituted tyrosine for Phe169, (β2F169Y). We coexpressed each mutant with the WT counterpart on Xenopus oocytes to express mutated forms of the α2β2 nAChRs and performed electrophysiological experiments (Fig. S3). Indeed, both HS and LS subtypes of the α2β2F169Y nAChR have a dramatic shift of the EC50 on the left, signifying in this way the enhanced role of loop F–loop C interaction on the receptor activation (Table S2 and Fig. 5 B and E). Therefore, one would expect that mutating Tyr199 to phenylalanine on α2 subunit would decrease sensitivity of the receptor. Quite the opposite, our functional studies showed that the α2Y199Fβ2 LS subtype decreased EC50, whereas the EC50 of the corresponding HS subtype remained expectedly unaffected (Table S2 and Fig. 5 B and E). To further confirm these results, we coexpressed both mutants on Xenopus oocytes, and indeed the α2Y199Fβ2F169Y nAChR showed even higher decrease on the EC50 for both subtypes HS and LS (Table S2 and Fig. 5 C and F). Taken as a whole, it becomes obvious that, not only both α2 Tyr199 and the corresponding residue in β2 subunit participate in α2β2 nAChR activation, but loops F of α2 and β2 subunits engage differently in ligand potency on α2β2 nAChRs.

Intrasubunit Interactions in α2 ECD with Functional Importance in nAChRs.

Other features found in the α2-Epi structure deal with the presence of interactions that in the native nAChRs participate to the allosteric communication between the neurotransmitter binding site and the remote ion channel. As was initially indicated through the structural studies of AChBP (47) and Torpedo nAChR (10), and was subsequently clearly shown via functional studies in the muscle-type nAChR (48, 49), local conformational changes due to ACh binding trigger a cascade that concludes in a global conformational change that leads to channel opening. Comparison of the free and agonist-bound states of AChBP reveals a profound alteration on the binding of carbamylcholine, probably as a result of the closure of loop C around the ligand. The salt bridge between the invariant Asp194 on the β10 strand and the conserved in most α-subunits Lys139 on the β7 strand (AChBP numbering) observed in the free state is replaced by an interaction between Tyr185 of loop C and Lys139 when carbamylcholine binds at the orthosteric binding site. Similarly, in the presented structure of α2 ECD, where the agonist epibatidine is bound and loop C adopts a closed-in conformation, Lys174 on β7 strand is placed away from Asp228 and approaches the hydroxyl group of Tyr219, forming an H-bond (Fig. 6B). It is therefore reasonable to assume that the α2-Epi structure mimics the conformation of the intact receptor's ECD when it is either in an open or a desensitized state (47). Furthermore, at the lower part of the α2 ECD (where in the native nAChR the interface between binding and pore domains would be) interactions between the loops that couple the agonist binding to channel gating were observed. The pre-M1 Arg237 (invariant in all α subunits) forms a salt bridge with the also highly conserved Asp167 on Cys loop, whereas it is sandwiched between Trp205 of loop F and the aromatic residues of Cys loop (Fig. 6C). Interestingly, the above residues at the interface of the ECD and membrane have been shown to play significant role to the signal transduction that leads to the channel gating (10, 50, 51). However, the extend of the interacting network in the α2-Epi structure is smaller compared with homologous structures (15, 21, 22), probably signifying the intrinsic flexibility of the membrane-facing loops.

Discussion

Structural elucidation of neuronal nAChRs has been the aim of several researchers over the last decades. In this study, we present the crystal structure of the pentameric assembly of the WT α2 nAChR ECD in complex with the agonist epibatidine. To date, only the crystal structures of muscle α1 nAChR ECD in complex with α-bungarotoxin and the neuronal α9 nAChR ECD in its free and antagonist-bound states have been determined (14, 15). Both provided invaluable information about the structure of a nAChR ECD, but because of their monomeric state, only the principal face of the ligand binding site was associated with a ligand. Nevertheless, there have been successful efforts to design and crystallize α7-AChBP chimeras where the binding site was composed mainly of α7 residues and the overall sequence identity to α7 approached 70% (18, 19). The latter is an ingenious strategy to reveal the structures of the binding sites of a plethora of nAChR subunits because the AChBP scaffold provides considerably useful information about the structural features involved in the agonist binding. More importantly, the exploitation of the chimeric structure obtained by Chen group (18) in in silico screening of drug-like molecules resulted in the identification of novel α7 nAChR ligands (52). However, the resolved α7-AChBP chimeras, due to the moderate identity with the α7 ECD in domains related to signal transduction, gating and desensitization, could also lead to fallacies concerning the functional importance of these regions.

On the contrary, the structure of α2 ECD offers an opportunity to investigate the pentameric assembly of a WT human neuronal nAChR ECD (Fig. 1 and Fig. S6). Indeed, the orientation and binding motif of epibatidine is very similar to those revealed in other homologous structures, and all of the conserved residues involved in ligand binding are in close contact with the epibatidine (Fig. 4 A–C and Fig. S7). Furthermore, loops A–F around the binding site are placed at the expected arrangement. However, the fact that the α2 nAChR subunit does not form a known functional homopentameric receptor raises the question of whether the ligand-induced homomerization affects the structure or aspects of it. However, comparison of the pentameric α2-ECD assembly with other homologous structures shows that their quaternary structures superimpose appreciably well (Fig. 1D).

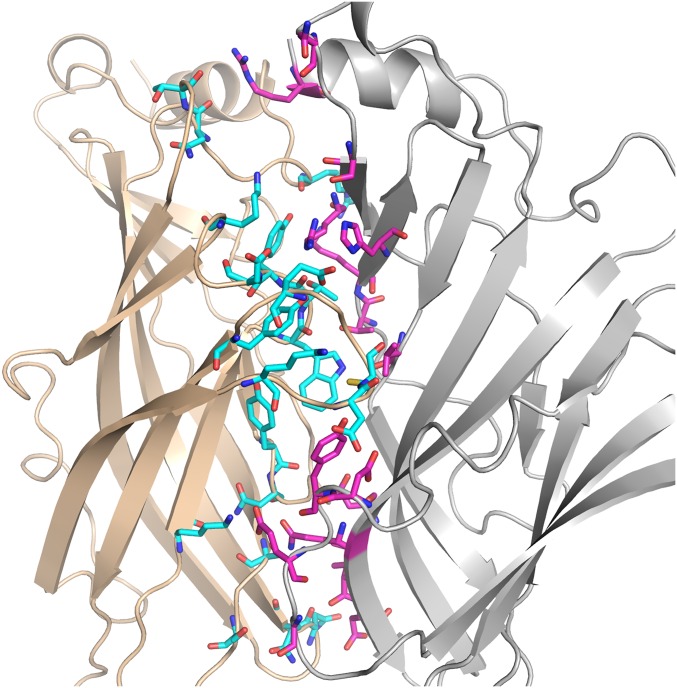

Fig. S6.

Close-up view of the interface between two adjacent subunits. The principal face of subunit E (wheat backbone, cyan interface residues) and the complementary face of the subunit A (light gray backbone, magenta interface residues) is presented.

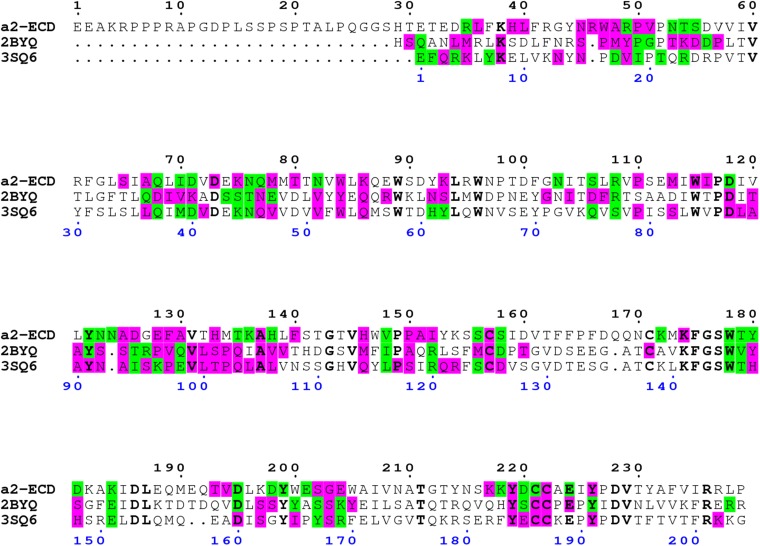

Fig. S7.

Sequence alignment of three epibatidine-bound pentameric structures, the human α2 nAChR ECD (PDB ID code 5FJV), Ac-AChBP (PDB ID code 2BYQ), and α7-AChBP chimera (PDB ID code 3SQ6). PISA analysis revealed the residues involved in polar interactions (H-bonds, salt bridges; highlighted in green) and in van-der-Waals’ interactions (highlighted in purple). Identical residues are in bold black.

Furthermore, by structure-guided mutagenesis, we provided functional data about structural elements involved in ligand binding and receptor activation not only in α2 subunit but in β2 as well. Particularly, we evaluated the functional role, both in activation and desensitization of α2β2 nAChRs, of a highly conserved residue, Trp84. We showed that this residue is involved in the binding, potency and desensitization rate of ACh but more importantly, through its mutation on α2 subunit, we provided solid evidence for the presence of the α2(+)/α2(−) binding site on the α2β2 LS subtype (Table S2). Besides, Gay et al. showed that aromatic residues at the same position on α7 nAChR are key for efficacy and desensitization (39). Additionally, by impairing the α2(+)/α2(−) binding interface, the two distinct interfaces found on the LS subtype can be distinguished in an agonist concentration response curve, hence producing a biphasic response. Similar conclusions have been drawn by studies on α4β2 nAChR (29, 43).

Looking closer the α2-Epi structure, loop F was found placed very close to loop C, as the side chain of Tyr199 forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone carbonyl Cys221 (Fig. 6A). To our knowledge, this interaction is apparent only in structures involving complexes of Ls-AChBP with ligands (11), and it has not been probed in α2β2 nAChRs before. Investigating the role of Tyr199 on α2 and the corresponding residue Phe169 on β2 subunit, we showed that loop F has a distinct role on these two subunits. Remarkably, the interaction between loops C and F via Tyr199 on the α2(+)/α2(−) binding site influences negatively the activation of the receptor, as was assessed by the EC50 decrease for the mutant α2Y199Fβ2, whereas the introduction of the particular interaction on the α2(+)/β2(−) binding site via the reverse mutation of the β2 subunit (α2β2F169Y mutant) had a positive impact on the potency of ACh (Table S2). It is worth noting that the same mutation (Phe for Tyr) on α7 and α3 subunits had an analogous effect on the EC50 values of ACh on the α7 and α3β2 nAChRs (53, 54), respectively. This outcome is not the first time, however, where the same residue on a particular position affects variably the channel activation, depending on the subunit it resides. Dougherty group showed emphatically that even the conserved cation-π interaction of nAChRs with agonists, can use different aromatic residues (and not necessarily Trp of loop B), depending on the nAChR subtype (55, 56). Finally, a similar to the observed erratic involvement of loop F in the activation of α2β2 nAChRs was previously evinced by the modulatory action of zinc ions on α4β2 nAChR, where depending on the involved interface zinc could either inhibit or potentiate the receptor (57).

The crystal structure of the α2 ECD showed an interaction between Tyr219 of loop C and Lys174 of β7 strand, probably caused upon epibatidine binding at the ligand binding site (Fig. 6B). This observation is in line with structural observations in homologous proteins, where an agonist was bound, and denotes that the α2-Epi structure resembles the activated or desensitized state of the nAChRs (47). Important ECD elements that couple ligand binding to channel gating in the context of a nAChR are the membrane-facing loops and their in-between interactions (50, 51). In the α2-Epi structure, we found an interconnecting network coordinated by the invariant pre-M1 Arg237 with the participation of Cys loop and loop F (Fig. 6C). However, their relative positions and interaction scheme could not be correlated to a particular nAChR state, due to the limitations that arise from the absence of the transmembrane domain.

Neuronal nAChRs are involved in diverse neurophysiological processes by the mediation of fast neurotransmission in the brain and they have been the target of many pharmaceutical approaches. However, the considerable high similarity among the subunits presents an obstacle on finding a subtype-specific drug for a single nAChR. Furthermore, their stoichiometry diversity overburdens the progress on functional elucidation and drug development. In that respect, the goal is to identify the structural elements that distinguish the subunits and their binding interfaces. The α2-Epi structure provides a major step forward for this route as many structural elements and their synergy become apparent on the pentameric conformation. Additionally, the human α2 ECD shares high sequence identity with other neuronal α and β nAChR ECDs, of most striking the 78% with, one of the most important nAChR subunits, the α4 (Fig. S5). Therefore, we propose its structure as a promising template for identifying the functionality and synergy of structural elements of other subunits and for structure-based drug design to treat nAChR-related diseases.

Materials and Methods

Human α2 nAChR ECD was expressed and purified using methods described in ref. 15. Crystallization of α2 ECD was carried out with the vapor diffusion method in sitting drops and the protein crystals were optimized by performing microseeding. Electrophysiology recordings were performed by expressing α2 and β2 nAChR subunits and its variants in Xenopus laevis oocytes as in ref. 15. Full methods are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

SI Materials and Methods

Construct Design.

The protein sequence of the human α2 nAChR ECD (UniProtQ15822, residues 27–265), including a C-terminal 6xHis tag, was reverse-translated and codon-optimized for yeast expression and the synthetic cDNA construct was prepared by Integrated DNA Technologies (Belgium). The cDNA sequence was then subcloned to pPICZαA vector (Invitrogen) for methanol-induced expression in yeast P. pastoris X33 strain (Invitrogen).

Protein Expression and Purification.

The protein expression and purification was prepared as described previously (15). In brief, the soluble protein was purified by affinity chromatography using Ni2+-NTA resin (Qiagen). The eluted protein was further purified by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) on Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in 20 mM Tris⋅HCl, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.05% NaN3, pH 7.5. The eluted fractions corresponding to the monomeric protein were collected and spin concentrated to 1 mg/mL using Amicon Ultra-15 with molecular weight cut-off 10,000 (Merck Millipore). The eluted protein was enzymatically deglycosylated by using 50 U EndoHf (NEB) per microgram of α2 ECD for 72 h at 8 °C. Deglycosylated α2 ECD was purified further by SEC on Superdex 75 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in 20 mM Tris⋅HCl, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.05% NaN3, pH 7.7.

Crystallization and Structure Refinement.

Human α2 ECD was set up using an Oryx4 crystallization robot (Douglas Instruments) with the vapor diffusion method in sitting drops. Prior setting up the crystallization drops epibatidine (Sigma-Aldrich E1145) dissolved in H2O was added to the protein solution at final protein/ligand molar ratio of 1:10 and the mixture was incubated at 4 °C for 1 h. Protein crystals appeared only in 1 of ∼700 conditions that were tested, and they were subsequently optimized with the microseeding method to produce crystals suitable for diffraction experiments. The best crystals were grown after mixing 0.36 μL protein-epibatidine solution (α2 ECD concentrated at 2 mg/mL), 0.18 μL mother liquor consisting of 100 mM Bicine, pH 9.5, 20% (wt/vol) PEG 8000, and 0.03 μL seed stock solution, prepared with previously crashed crystals. The crystals appeared within 4–7 d reaching their final size in 2 wk at 16 °C. Crystals were soaked in a cryoprotectant solution containing the mother liquor and 20% (vol/vol) ethylene glycol for 5–10 s prior their exposure to the beam. Diffraction experiments were carried out on beamline X06 DA at the Swiss Light Source at 100 K, and a single wavelength dataset was collected to 3.20-Å resolution. Images were indexed, integrated, and scaled using the program XDS (58) in the space group that was determined with Pointless (59) using unmerged data (Table S1). The structure was solved with molecular replacement in Phaser (60) using as a model the structure of Ls-AChBP in complex with carbamylcholine (PDB ID code 1UV6) (47) and was subsequently refined in Phenix (61). Despite the clear and unique solution from Phaser (TF Z-score: 11.4, LLG: 168) when a limited number of packing clashes were allowed, the conventional refinement procedure could not improve the model further and the Rfree value remained attached to ∼50%. Regardless, the electron density of the protein core (including the binding site) was well defined and the difference map revealed the presence of the ligand. To overcome the problematic refinement, a combination of reciprocal-space crystallographic refinement with a structure modeling methodology, as implemented in Rosetta-Phenix refinement (62), was performed. Subsequently, conventional refinement in Phenix, using noncrystallographic symmetry restraints and additional model restraints for the torsion angles and the secondary structure elements derived from the high resolution structure of the α9 ECD (15), led to a converged final model. The asymmetric unit contained one pentamer of α2 ECDs whose subunits superimpose very well with an RMSD of 0.234 Å for the main chain atoms. Regular inspection of the electron density maps 2Fo-Fc and Fo-Fc (σ-Α weighted) and refitting of the model, where necessary, was performed with COOT (63). The ligand was initially placed unbiased in the residual density and kept its position without any restraints throughout the whole reciprocal–space refinement. Additionally, its position remained virtually unaltered during the numerous real-space refinement iterations. The refinement statistics for the converged final model are given on Table S1. Figures were generated using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (Schroedinger).

Mutagenesis on Human α2 and β2 cDNAs and cRNA Preparation.

A synthetic cDNA of human α2 nAChR subunit was sequence optimized and prepared by Integrated DNA Technologies. The human β2 nAChR subunit cDNA was subcloned previously (64). Both α2 and β2 cDNAs were subcloned between EcoRI and XhoI of a modified pSGEM vector (15, 65), which was generously provided by J. M. McIntosh (University of Utah, Salt Lake City). All mutants were made by PCR with the QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies). The mutations were confirmed by sequencing. The NheI and PacI (NEB) enzymes were used to linearize the vectors encoding the human α2 and β2 nAChR subunits, respectively. Capped cRNA was prepared by in vitro transcription using T7 RiboMAX kit (Promega). The cRNA concentration was determined by absorbance at 260 nm.

cRNA Injections in Oocytes.

Defoliated oocytes at stage VI were purchased from EcoCyte Bioscience. The oocytes were kept at 17 °C in ND96 (96 mM NaCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 2.0 mM KCl, 1.0 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM Hepes, pH 7.1–7.5) supplemented with antibiotics (50 U/mL penicillin, 50 mg/mL streptomycin, and 50 mg/mL gentamicin). The oocytes were injected with up to 45 nL cRNA and incubated for 3 d before recordings. The amount of total cRNA injected into each oocyte was 16.5 ng, with a ratio of α2 to β2 equal to 10:1 or 1:10.

Electrophysiological Recordings and Analysis.

The two-electrode voltage-clamp technique was used to record whole-cell ACh-evoked membrane current responses from oocytes, 3–6 d after injection with cRNA, by the use of a Geneclamp 500B (Axon Instruments) amplifier interfaced to a personal computer with a Digidata 1550 digitizer (Axon Instruments) analog to digital converter. Recording electrodes, fabricated from borosilicated glass pipettes and filled with 3 M KCl solution (intracellular solution), had a resistance of 0.4–2.0 MΩ. All current recordings were performed at room temperature. Oocytes, seated in a homemade chamber with their membranes clamped at −70 mV, were continuously superfused with extracellular solution (ND96 buffer pH 7.4 plus or minus ACh; 0.1–1 mM) using the Superfast 8 perfusion system (List Medical) and driven away with the use of a peristaltic pump (List Medical). The oocytes’ resting membrane potential (Er) was measured by the voltage electrode and oocytes with an Er > −40 mV were excluded. Current data were initially analyzed with the ClampFit program of the pClamp 10 software (Axon Instruments) and further analyzed and illustrated with the Origin technical graphics and data analysis program (OriginLab). Current traces of varying concentrations of ACh were normalized to the maximal response observed in each oocyte. Normalized data were fitted using the one or two-component sigmoidal dose–response equation. For monophasic response the equation Y = Bottom + (Top − Bottom)/{1 + 10^[(LogEC50 − X) × nH]} was used, where Y is the current response; Bottom and Top are the minimum and maximum of the fit, respectively; EC50 is the ACh concentration that caused 50% of the maximum response; X is the logarithm of ACh concentration; and nH is the Hill slope. For biphasic activation response the equation Y = Bottom + (Top − Bottom) × Frac/{1 + 10^[(LogEC50_1 − X) × nH_1]} + (Top − Bottom) × (1 – Frac)/{1 + 10^[(LogEC50_2 – X) × nH_2]} was used, where the EC50_1 and EC50_2 are the concentrations that give half-maximal high sensitivity and low sensitivity stimulatory effects, respectively, nH_1 and nH_2 are the Hill coefficients, and Frac is the proportion of the maximal response due to the high sensitivity phase. For the biphasic response analysis, the Bottom was fixed to 0 and the nH_1 and nH_2 were chosen to be greater than 0. Extra sum-of-squares F test was used to evaluate whether a given dataset was best represented by a biphasic or the simpler monophasic model and the results are written as F value (DFn, DFd). The simpler model was selected unless the P value was less than 0.05. The EC50, 95% CI, and Hill coefficient (nH) were determined by nonlinear regression using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software).

For analysis of the onset rate of desensitization, whole cell current data were fit over the period from the point just after the peak inward current to the end of the drug application. Oocytes were exposed to a single application of ACh, which was performed at a holding potential of −70 mV. Data were obtained using concentrations that evoked 75% (EC75) of the maximum current that is reasonable to assume that desensitization occurs at these concentrations (66). Current traces were normalized to estimate the onset of desensitization time constants. All traces were fitted to one or two exponential decay function and statistical analysis of the data were performed using Origin (OriginLab). The function plotted to describe the decay currents was I(t) = Afexp(−t/τf) + Asexp(−t/τs) + C, where I(t) the current amplitude at any given time, Af is the magnitude of the more quickly decaying desensitization process characterized by time constant τf, As is the magnitude of the more slowly decaying desensitization process characterized by time constant τs, and C is the steady-state current that does not fully desensitize. Four to six oocytes were used to determine the average τ and ±SEM. Statistically significant differences were calculated using GraphPad. All experiments were performed at room temperature (23 ± 1 °C).

SI Discussion

The addition of the α2 homopentamer in the subset of the nAChR known structures provided the opportunity to compare the subunit–subunit interactions between the available homopentamers (Fig. S6). To attenuate the effect of the ligand's chemical composition we limited the comparison with the three epibatidine bound structures, α2 ECD (PDB ID code 5FJV), α7-AChBP chimera (PDB ID code 3SQ6), and Ac-AChBP (PDB ID code 2BYQ). Exploration of the macromolecular interfaces with PISA (67) produced similar values for the average interface area: 1,389 ± 49, 1,307 ± 40, and 1,418 ± 40, respectively. Furthermore, the sequence alignment showed clearly that the interface interacting residues extend mainly to the same topological regions (Fig. S7). However, unlike the ligand binding residues, which are highly conserved, the interface residues present extensive variability among the different nAChR subtypes, depending each time on the participating subunits (Fig. S7). Particularly, for the compared structures, as the residues differ considerably between the subunits (this extends also to the other subunits), and the nature of interactions depends highly on the physicochemical properties of the implicated residues, the actual interactions were not conserved in the three pentameric structures. Therefore, the deduction of structural determinants critical to the formation of pentameric assemblies remains elusive.

Although, the existence of an α2 homopentamer has not been proven functionally, the inherent affinity of an α2 subunit for itself to form an α2(+)/α2(−) interface cannot be excluded. The AChBPs, water soluble homologs to the ECD of the nAChR, present pentameric quaternary structure in the absence of a ligand (11). Moreover, the α7 nAChR ECD also forms pentameric complexes in the absence of a ligand (68). Therefore, there is an inherent ability of some subunits in the Cys loop superfamily to form multimers. Besides, the presence of a binding site with functional importance between two identical α subunits such as α7(+)/α7(−) or α4(+)/α4(−) has been manifested in numerous studies (29, 40, 41), and particularly for the latter case, it has been clarified its contribution to the low-sensitivity phenotype of the α4β2 nAChR (29). Given the high sequence similarity between α2 and α4 ECDs (Fig. S5), it is not surprising that a α4β2 high affinity ligand, such as epibatidine, acted virtually as a nodal agent that brought together two α2 ECD protomers in a close-to-native orientation, allowing the formation of the α2(+)/α2(−) interface.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at Swiss Light Source for help during X-ray data collection and M. Zouridakis and E. Zarkadas for excellent help and fruitful discussions on the project. We also thank M. Zouridakis and P. Bregestovski for critical reading of the manuscript and invaluable suggestions. This work was supported by the European Commission Seventh Framework Programme Grants NeuroCypres (202088), REGPOT-NeuroSign (264083), and BioStruct-X (283570) and Greek General Secretariat for Research and Technology Aristeia Grant 1154 (to S.J.T.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 5FJV).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1602619113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Jürgensen S, Ferreira ST. Nicotinic receptors, amyloid-beta, and synaptic failure in Alzheimer’s disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2010;40(1-2):221–229. doi: 10.1007/s12031-009-9237-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perez XA, Bordia T, McIntosh JM, Quik M. α6ß2* and α4ß2* nicotinic receptors both regulate dopamine signaling with increased nigrostriatal damage: Relevance to Parkinson’s disease. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;78(5):971–980. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.067561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahman S, López-Hernández GY, Corrigall WA, Papke RL. Neuronal nicotinic receptors as brain targets for pharmacotherapy of drug addiction. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2008;7(5):422–441. doi: 10.2174/187152708786927831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aridon P, et al. Increased sensitivity of the neuronal nicotinic receptor α 2 subunit causes familial epilepsy with nocturnal wandering and ictal fear. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79(2):342–350. doi: 10.1086/506459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilens TE, Decker MW. Neuronal nicotinic receptor agonists for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Focus on cognition. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74(8):1212–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu J, et al. Discovery of isoxazole analogues of sazetidine-A as selective α4β2-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonists for the treatment of depression. J Med Chem. 2011;54(20):7280–7288. doi: 10.1021/jm200855b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Posadas I, López-Hernández B, Ceña V. Nicotinic receptors in neurodegeneration. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2013;11(3):298–314. doi: 10.2174/1570159X11311030005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Changeux JP, Edelstein SJ. Allosteric receptors after 30 years. Neuron. 1998;21(5):959–980. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80616-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zoli M, Pistillo F, Gotti C. Diversity of native nicotinic receptor subtypes in mammalian brain. Neuropharmacology. 2015;96(Pt B):302–311. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unwin N. Refined structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at 4A resolution. J Mol Biol. 2005;346(4):967–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brejc K, et al. Crystal structure of an ACh-binding protein reveals the ligand-binding domain of nicotinic receptors. Nature. 2001;411(6835):269–276. doi: 10.1038/35077011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Celie PH, et al. Crystal structure of acetylcholine-binding protein from Bulinus truncatus reveals the conserved structural scaffold and sites of variation in nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(28):26457–26466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414476200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansen SB, et al. Structures of Aplysia AChBP complexes with nicotinic agonists and antagonists reveal distinctive binding interfaces and conformations. EMBO J. 2005;24(20):3635–3646. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dellisanti CD, Yao Y, Stroud JC, Wang ZZ, Chen L. Crystal structure of the extracellular domain of nAChR alpha1 bound to alpha-bungarotoxin at 1.94 A resolution. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(8):953–962. doi: 10.1038/nn1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zouridakis M, et al. Crystal structures of free and antagonist-bound states of human α9 nicotinic receptor extracellular domain. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21(11):976–980. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bocquet N, et al. X-ray structure of a pentameric ligand-gated ion channel in an apparently open conformation. Nature. 2009;457(7225):111–114. doi: 10.1038/nature07462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hilf RJ, Dutzler R. X-ray structure of a prokaryotic pentameric ligand-gated ion channel. Nature. 2008;452(7185):375–379. doi: 10.1038/nature06717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li SX, et al. Ligand-binding domain of an α7-nicotinic receptor chimera and its complex with agonist. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(10):1253–1259. doi: 10.1038/nn.2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nemecz A, Taylor P. Creating an α7 nicotinic acetylcholine recognition domain from the acetylcholine-binding protein: Crystallographic and ligand selectivity analyses. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(49):42555–42565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.286583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Althoff T, Hibbs RE, Banerjee S, Gouaux E. X-ray structures of GluCl in apo states reveal a gating mechanism of Cys-loop receptors. Nature. 2014;512(7514):333–337. doi: 10.1038/nature13669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller PS, Aricescu AR. Crystal structure of a human GABAA receptor. Nature. 2014;512(7514):270–275. doi: 10.1038/nature13293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hassaine G, et al. X-ray structure of the mouse serotonin 5-HT3 receptor. Nature. 2014;512(7514):276–281. doi: 10.1038/nature13552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang X, Chen H, Michelsen K, Schneider S, Shaffer PL. Crystal structure of human glycine receptor-α3 bound to antagonist strychnine. Nature. 2015;526(7572):277–280. doi: 10.1038/nature14972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Du J, Lü W, Wu S, Cheng Y, Gouaux E. Glycine receptor mechanism elucidated by electron cryo-microscopy. Nature. 2015;526(7572):224–229. doi: 10.1038/nature14853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han ZY, et al. Localization of nAChR subunit mRNAs in the brain of Macaca mulatta. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12(10):3664–3674. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishii K, Wong JK, Sumikawa K. Comparison of alpha2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit mRNA expression in the central nervous system of rats and mice. J Comp Neurol. 2005;493(2):241–260. doi: 10.1002/cne.20762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dash B, Lukas RJ, Li MD. A signal peptide missense mutation associated with nicotine dependence alters α2*-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor function. Neuropharmacology. 2014;79:715–725. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nelson ME, Kuryatov A, Choi CH, Zhou Y, Lindstrom J. Alternate stoichiometries of alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63(2):332–341. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mazzaferro S, et al. Additional acetylcholine (ACh) binding site at α4/α4 interface of (α4β2)2α4 nicotinic receptor influences agonist sensitivity. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(35):31043–31054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.262014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moroni M, Zwart R, Sher E, Cassels BK, Bermudez I. α4β2 nicotinic receptors with high and low acetylcholine sensitivity: Pharmacology, stoichiometry, and sensitivity to long-term exposure to nicotine. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70(2):755–768. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.023044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vallejo YF, Buisson B, Bertrand D, Green WN. Chronic nicotine exposure upregulates nicotinic receptors by a novel mechanism. J Neurosci. 2005;25(23):5563–5572. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5240-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Srinivasan R, et al. Nicotine up-regulates α4β2 nicotinic receptors and ER exit sites via stoichiometry-dependent chaperoning. J Gen Physiol. 2011;137(1):59–79. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201010532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grutter T, et al. An H-bond between two residues from different loops of the acetylcholine binding site contributes to the activation mechanism of nicotinic receptors. EMBO J. 2003;22(9):1990–2003. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiu X, Puskar NL, Shanata JA, Lester HA, Dougherty DA. Nicotine binding to brain receptors requires a strong cation-pi interaction. Nature. 2009;458(7237):534–537. doi: 10.1038/nature07768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cashin AL, Torrice MM, McMenimen KA, Lester HA, Dougherty DA. Chemical-scale studies on the role of a conserved aspartate in preorganizing the agonist binding site of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Biochemistry. 2007;46(3):630–639. doi: 10.1021/bi061638b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee WY, Sine SM. Invariant aspartic Acid in muscle nicotinic receptor contributes selectively to the kinetics of agonist binding. J Gen Physiol. 2004;124(5):555–567. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harpsøe K, et al. Unraveling the high- and low-sensitivity agonist responses of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Neurosci. 2011;31(30):10759–10766. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1509-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahring PK, et al. Engineered α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as models for measuring agonist binding and effect at the orthosteric low-affinity α4-α4 interface. Neuropharmacology. 2015;92:135–145. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gay EA, Giniatullin R, Skorinkin A, Yakel JL. Aromatic residues at position 55 of rat alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are critical for maintaining rapid desensitization. J Physiol. 2008;586(4):1105–1115. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.149492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eaton JB, et al. The unique α4+/-α4 agonist binding site in (α4)3(β2)2 subtype nicotinic acetylcholine receptors permits differential agonist desensitization pharmacology versus the (α4)2(β2)3 subtype. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014;348(1):46–58. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.208389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Corringer PJ, et al. Identification of a new component of the agonist binding site of the nicotinic α 7 homooligomeric receptor. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(20):11749–11752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.11749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Leary ME, Filatov GN, White MM. Characterization of d-tubocurarine binding site of Torpedo acetylcholine receptor. Am J Physiol. 1994;266(3 Pt 1):C648–C653. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.3.C648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benallegue N, Mazzaferro S, Alcaino C, Bermudez I. The additional ACh binding site at the α4(+)/α4(-) interface of the (α4β2)2α4 nicotinic ACh receptor contributes to desensitization. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170(2):304–316. doi: 10.1111/bph.12268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Akk G, Zhou M, Auerbach A. A mutational analysis of the acetylcholine receptor channel transmitter binding site. Biophys J. 1999;76(1 Pt 1):207–218. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77190-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gleitsman KR, Kedrowski SM, Lester HA, Dougherty DA. An intersubunit hydrogen bond in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor that contributes to channel gating. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(51):35638–35643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807226200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martin MD, Karlin A. Functional effects on the acetylcholine receptor of multiple mutations of γ Asp174 and δ Asp180. Biochemistry. 1997;36(35):10742–10750. doi: 10.1021/bi970896t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Celie PH, et al. Nicotine and carbamylcholine binding to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as studied in AChBP crystal structures. Neuron. 2004;41(6):907–914. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mukhtasimova N, Free C, Sine SM. Initial coupling of binding to gating mediated by conserved residues in the muscle nicotinic receptor. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126(1):23–39. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sine SM, Engel AG. Recent advances in Cys-loop receptor structure and function. Nature. 2006;440(7083):448–455. doi: 10.1038/nature04708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee WY, Sine SM. Principal pathway coupling agonist binding to channel gating in nicotinic receptors. Nature. 2005;438(7065):243–247. doi: 10.1038/nature04156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mukhtasimova N, Sine SM. Nicotinic receptor transduction zone: Invariant arginine couples to multiple electron-rich residues. Biophys J. 2013;104(2):355–367. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Akdemir A, et al. Identification of novel α7 nicotinic receptor ligands by in silico screening against the crystal structure of a chimeric α7 receptor ligand binding domain. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20(19):5992–6002. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.06.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Galzi JL, Bertrand S, Corringer PJ, Changeux JP, Bertrand D. Identification of calcium binding sites that regulate potentiation of a neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. EMBO J. 1996;15(21):5824–5832. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Short CA, et al. Subunit interfaces contribute differently to activation and allosteric modulation of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2015;91:157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beene DL, et al. Cation-pi interactions in ligand recognition by serotonergic (5-HT3A) and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: The anomalous binding properties of nicotine. Biochemistry. 2002;41(32):10262–10269. doi: 10.1021/bi020266d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Puskar NL, Xiu X, Lester HA, Dougherty DA. Two neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, alpha4beta4 and alpha7, show differential agonist binding modes. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:14618–14627. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.206565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moroni M, et al. Non-agonist-binding subunit interfaces confer distinct functional signatures to the alternate stoichiometries of the α4β2 nicotinic receptor: An α4-α4 interface is required for Zn2+ potentiation. J Neurosci. 2008;28(27):6884–6894. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1228-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kabsch W. Xds. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 2):125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Evans P. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62(Pt 1):72–82. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905036693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Cryst. 2007;40(Pt 4):658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Afonine PV, et al. Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2012;68(Pt 4):352–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912001308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.DiMaio F, et al. Improved low-resolution crystallographic refinement with Phenix and Rosetta. Nat Methods. 2013;10(11):1102–1104. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 4):486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kouvatsos N, et al. Purification and functional characterization of a truncated human α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Int J Biol Macromol. 2014;70(0):320–326. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Filchakova O, McIntosh JM. Functional expression of human α9* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in X. laevis oocytes is dependent on the α9 subunit 5′ UTR. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64655. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vibat CR, Lasalde JA, McNamee MG, Ochoa EL. Differential desensitization properties of rat neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit combinations expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1995;15(4):411–425. doi: 10.1007/BF02071877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol. 2007;372(3):774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zouridakis M, et al. Design and expression of human alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor extracellular domain mutants with enhanced solubility and ligand-binding properties. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1794(2):355–366. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]