Significance

Debilitating heart conditions, dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), are often due to inherited or acquired mutations in genes that encode specific components of adhesion complexes. In muscle tissue, some of these adhesion complexes have specialized structures, called intercalated discs, which are important for contraction and coordinated movement. Here we provide molecular insights into the cytoskeletal protein metavinculin, which is necessary for the proper development and maintenance of heart tissue and is mutated in human DCM and HCM. We show that the binding of lipid causes metavinculin to dimerize and involves a specific metavinculin amino acid associated with severe DCM/HCM. Collectively, our studies provide insight into how such metavinculin mutations in components of adhesion complexes lead to cardiomyopathies.

Keywords: cardiomyopathy, cell adhesion, cytoskeleton, metavinculin, vinculin

Abstract

The main cause of death globally remains debilitating heart conditions, such as dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), which are often due to mutations of specific components of adhesion complexes. Vinculin regulates these complexes and plays essential roles in intercalated discs that are necessary for muscle cell function and coordinated movement and in the development and function of the heart. Humans bearing familial or sporadic mutations in vinculin suffer from chronic, progressively debilitating DCM that ultimately leads to cardiac failure and death, whereas autosomal dominant mutations in vinculin can also provoke HCM, causing acute cardiac failure. The DCM/HCM-associated mutants of vinculin occur in the 68-residue insert unique to the muscle-specific, alternatively spliced isoform of vinculin, termed metavinculin (MV). Contrary to studies that suggested that phosphoinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) only induces vinculin homodimers, which are asymmetric, we show that phospholipid binding results in a domain-swapped symmetric MV dimer via a quasi-equivalent interface compared with vinculin involving R975. Although one of the two PIP2 binding sites is preserved, the symmetric MV dimer that bridges two PIP2 molecules differs from the asymmetric vinculin dimer that bridges only one PIP2. Unlike vinculin, wild-type MV and the DCM/HCM-associated R975W mutant bind PIP2 in their inactive conformations, and R975W MV fails to dimerize. Mutating selective vinculin residues to their corresponding MV residues, or vice versa, switches the isoform’s dimeric constellation and lipid binding site. Collectively, our data suggest that MV homodimerization modulates microfilament attachment at muscular adhesion sites and furthers our understanding of MV-mediated cardiac remodeling.

Cardiomyopathies are a major worldwide health problem, with patients often suffering cardiac arrest and premature death. Over the past decade, several inherited and sporadic mutations in genes encoding components of adhesion complexes and of intercalated discs, which are required for the coordinated movement of heart tissue, have been pinpointed as the cause of many cardiomyopathies. Vinculin and its muscle-specific splice variant, metavinculin (MV), are essential and highly conserved cytoskeletal proteins that play critical regulatory roles in cell–cell adherens-type junctions and cell–matrix focal adhesions (1–3). Both isoforms localize to the cell membrane, the I band in the sarcomere, and to intercalated discs (4). MV is coexpressed with vinculin (5) and colocalizes with vinculin in cardiac myocytes (6). MV only differs from vinculin by an insertion of 68 residues between α-helices H1 and H2 of the 5-helix bundle vinculin tail domain Vt (5, 7), whereby H1′ of the insert of MV structurally replaces H1 of vinculin. Several MV mutations have been shown to be associated with dilated cardiomyopathies (DCMs) and hypertrophic cardiomyopathies (HCMs) in human (8–10), where they disrupt intercalated discs in the hearts of afflicted patients (8, 9), resulting in improper force generation and stress-induced phenotype in the heart. Reduced meta/vinculin expression leads to abnormal myocytes, which predispose to stress-induced cardiomyopathy (11). The missense mutation R975W present in the MV-specific insert is associated with both DCM and HCM phenotypes and alters the organization of intercalated discs in vivo. This mutation has been suggested to compromise the interactions of MV with its partners, including vinculin (10).

Both vinculin isoforms are held in a closed, inactive conformation through extensive hydrophobic interactions of the meta/vinculin head (VH) and C-terminal Vt (or MVt in MV) domains, which are connected via a flexible proline-rich linker (12–17). The intramolecular head–tail association regulates the binding of a large number of proteins, including talin (18), α-actinin (19), or α- (20) and β-catenin (21) to VH, and F-actin (22, 23), phosphoinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) (24), and raver1 (25) to Vt or MVt. Further, the proline-rich hinge binds to the vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein VASP, vinexin-β, and the Arp2/3 complex to control actin dynamics at adhesion sites and thus cell migration (26–28). Our structures of activated vinculin in complex with the vinculin binding sites (VBSs) of talin (14, 15, 29, 30), α-actinin (16), or IpaA (31–33) showed that binding of these VBSs severs the vinculin head–tail interaction and displaces Vt allosterically. Originally, PIP2 was thought to sever the VH–Vt interaction (34–36), but the VBSs of talin and α-actinin, or those of the IpaA invasin of Shigella, are sufficient to activate vinculin, whereas mechanical stretching of a single talin molecule activates vinculin (37). More recently, our vinculin/PIP2 dimer structure showed that the VH and PIP2 binding sites on Vt are distinct (38).

Vinculin oligomerization amplifies its interactions with other adhesion proteins, yet the observed PIP2-induced oligomerization (26, 39–41) might have been the result of an artifact of cross-linking and the physiological lipid-induced vinculin oligomer seems to be the dimer (42). In the Vt/PIP2 crystal structure, one PIP2 molecule is sandwiched between three Vt molecules, whereby two Vt subunits engage in a domain swap-like arrangement of their C-terminal coiled-coil regions (38). We showed that PIP2 binding is necessary for organizing stress fibers, for maintaining optimal focal adhesions and for cell migration and spreading, and that PIP2 binding is necessary for the control of vinculin dynamics and turnover in focal adhesions (38).

Here we provide mechanistic insight into PIP2-induced MV dimerization. We show that in contrast to previous reports, PIP2 binding induces MV homodimerization via a domain swap-like arrangement of the C termini. Although one of the two PIP2 binding sites is preserved in both isoforms, the symmetric MVt dimer, which binds two PIP2 molecules, differs from the asymmetric Vt dimer, which binds one PIP2, mainly due to the presence of the MVt-specific, DCM/HCM-associated R975 residue. In contrast to vinculin, which only binds PIP2 in its activated, open form, MV binds PIP2 also in its inactive, closed conformation. However, dimerization is only possible for activated MV, and the DCM/HCM-associated mutant MV does not dimerize even when activated. Collectively, we provide important insights into how dimerization of MV contributes to the stabilization of adhesion complexes.

Results

Architecture of the PIP2-Bound MV Structure.

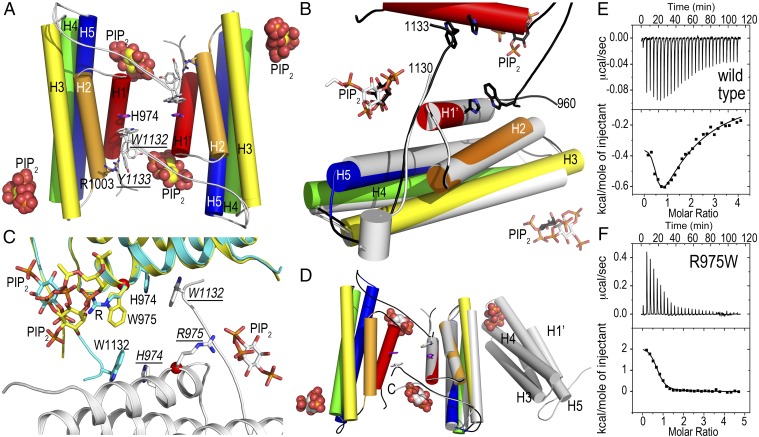

Although MV was thought to be impaired in dimerizing, our MVt/PIP2 crystal structure (SI Appendix, Tables S1 and S2) shows that each MVt molecule forms a domain-swapped dimer, whereby the C terminus of one subunit reaches into a pocket of the twofold-related MVt (Fig. 1A). Specifically, W1132 stacks with H974, and Y1133 interacts with R1003 (where the underline throughout the text denotes that the residue is from a symmetry-related subunit). Residues 1131–1134 are necessary for lipid-induced dimer formation, as the MVt Δ1131–1134 binds PIP2 without dimerization in the crystal (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Tables S1 and S2) or in solution (42). This region is disordered in the unbound MVt and full-length MV structures (13). In the MVt/PIP2 structure, residues 1116–1123 following the last α-helix H5 interact with the C terminus of α-helix H3 (residue 1039), whereas this region is disordered in the unbound MVt structure, interacting instead with the proline-rich region in the full-length structures (12, 13).

Fig. 1.

Structural and thermodynamic analyses of PIP2-induced MV dimerization. (A) Cartoon drawing of the 3.1-Å crystal structure of MVt (residues 959–1134) in complex with PIP2. There are four five-helix bundle MVt molecules in the asymmetric unit (for clarity, only the dimer is shown) and the four polypeptide chains can be superimposed with rmsd ranging from 0.2 Å to 0.29 Å for over 851 atoms. There are five PIP2 molecules in the asymmetric unit and the four PIP2 binding sites near the C terminus (proximal to R1128) are occupied, indicating that this site is important for dimerization, and the second site (K1012 and R1013) is occupied in one molecule in the asymmetric unit. W1132 from one MVt molecule stacks against H974 from a twofold-related MVt molecule in a domain swap-like arrangement. MVt α-helices are labeled H1′ and H2–H5 and are colored spectrally (red, residues 964–979, H1′; orange, 986–1006, H2; yellow, 1009–1039, H3; green, 1042–1074, H4; and blue, 1081–1116, H5). PIP2 molecules are shown as spheres. (B) Close-up view of the superposition (rmsd of 0.399 Å for 910 atoms) of the MVt/PIP2 structure onto the 2.3-Å truncated (Δ1131–1134) PIP2-bound MVt crystal structure that does not dimerize (gray). Although the two PIP2 binding sites are conserved (black sticks for PIP2 in the MVt Δ1131–1134 /PIP2 structure), the truncated C terminus does not allow for the lipid-induced dimerization. MVt α-helices are labeled H1′ and H2–H5 and are colored spectrally; MVt Δ1131–1134 is shown in gray. (C) Close-up view of the superposition (rmsd of 0.393 Å for 885 atoms) of the MVt/PIP2 structure onto the 2.9-Å PIP2-bound DCM/HCM-associated MVt R975W crystal structure that does not dimerize. The two polypeptide chains of the dimeric wild-type MVt are colored in cyan and gray, respectively, and the DCM/HCM-associated MVt R975W in yellow. (D) Superposition (rmsd of 0.496 Å for 949 atoms) of wild-type MVt/PIP2 (α-helices are colored spectrally; PIP2 is shown as spheres) onto the R975Q–K979Q–R1107Q–R1128Q mutant MVt/PIP2 structure (shown in gray). The quadruple mutant binds PIP2 and does not dimerize, and a symmetry-related molecule occupies the second PIP2 binding site. In the mutant MVt structure, the loop after the last α-helix H5 (residues 1116–1123) adopts a conformation in between the one found for the wild-type MVt/PIP2 and the full-length MV structures (not shown for clarity). Otherwise, the mutant and wild-type MVt/PIP2 structures are very similar for residues 959–1129. (E) Isothermal titration calorimetry binding traces for calorimetric titrations of PIP2 to MVt. (Upper) Sequence of peaks corresponding to each injection where the monitored signal is the additional thermal power needed to be supplied or removed to keep a constant temperature relative to the reference cell. (Lower) Integrated heat plot of the area of each peak per mole versus the molar ratio. The solid line corresponds to theoretical curves with Kd = 0.7 μM, ΔH = −0.335 ± 0.008 kcal/mol and n = 0.483 ± 0.054 for the high-affinity binding site and Kd = 0.59 μM, ΔH = −2.3 ± 0.222 kcal/mol and n = 0.98 ± 0.81 for the lower affinity binding site. MVt protein samples were in the cell at a concentration of 25–30 μM and PIP2 was in the syringe at a concentration of 600–700 μM at 1:20 or 1:30 molar ratio at 25 °C. (F) ITC binding traces for calorimetric titrations of PIP2 to MVt R975W. Kd = 2.3 μM, ΔH = 2.1 ± 0.064 kcal/mol, and n = 0.71 ± 0.015.

MVt has two nanomolar binding sites for Vt/PIP2 mediated by PIP2 (42) and indeed two PIP2 molecules were bound to MVt and MVt Δ1131–1134 (Fig. 1 A and B). One PIP2 binding site (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A) is formed by the C terminus of α-helix H5, involving R1107 and E1110 and the C-terminal coiled coil, in particular R1128, as well as the C terminus of α-helix H1′, whereby R975, which is mutated to a tryptophan in DCM/HCM, engages in electrostatic interactions with the PIP2 5′-phosphate group. K979 and R1128 additionally bind the PIP2 4′- and 5′-phosphate groups. A second PIP2 binding site is provided by N-terminal residues of α-helix H3, where K1012 and R1013 bind PIP2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). Collectively, PIP2 induces dimerization of MVt and residues 1131–1134 are necessary for lipid-induced MVt dimerization but not for lipid binding.

The DCM/HCM-Associated R975W Mutation Prevents Lipid-Induced MV Dimerization.

The missense mutation R975W is associated with both DCM and HCM phenotypes, alters the organization of intercalated discs in vivo, and has been suggested to compromise the interactions of MV with its partners, including vinculin (10). We found that R975W prevents homodimerization (Fig. 1C) due to its bulkier tryptophan side chain. Whereas the R975W five-helix bundle remains essentially the same, the H4–H5 loop (residues 1037–1080) and significantly the C terminus (residues 1132–1134), which is domain swapped in wild-type MVt, are disordered in the MVt R975W/PIP2 structure. This causes the lipid to bind the mutant ∼5 Å away from its corresponding wild-type binding site (Fig. 1C). Further, one PIP2 is bound in the monomeric R975W structure (versus two in the wild-type dimer interface), which might explain the molecular basis of the most severe DCM/HCM-associated MV mutant. Interestingly, in our apo MVt R975W crystal structure (SI Appendix, Tables S3 and S4), Q1134 and W1132 stack with H974 intramolecularly (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), whereas W1132 instead stacks with H974 intermolecularly in the PIP2-induced dimer structure. Collectively, this finding suggests that PIP2 first induces the release of the C terminus, which then induces dimerization.

Based on our PIP2-bound MVt and MVt Δ1131–1134 crystal structures, we generated an exhaustively large number of mutants that should be deficient in binding to PIP2. Unfortunately, whereas point mutations were easy to generate, mutating key residues of both PIP2 binding sites (R975, K979, K1012, R1013, R1107, and R1128) resulted in precipitation that precluded obtaining interpretable binding results. Further, a quadruple MVt mutant targeting the domain-swapped dimerization region (R975Q, K979Q, R1107Q, and R1128Q) still bound PIP2 (as did all mutants that were soluble), given the availability of the second PIP2 binding site (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C). All mutant proteins are functional and bind to F-actin (SI Appendix, Fig. S1D). We solved the crystal structure of this quadruple mutant in the presence of PIP2 (SI Appendix, Tables S1 and S2) and found no electron density for PIP2, and the mutant MVt did not engage in dimer interactions (Fig. 1D). Significantly, in the mutant structure the C terminus folds back to almost occupy the space filled by PIP2 in the wild-type structure. The fact that the second lipid-binding site involving K1012 and R1013 is occupied by crystal contacts instead suggests that the second binding site is weaker. Indeed, PIP2 bound to MVt with binding affinities of 0.7 and 59 μM, respectively, for the two sequential binding sites (Fig. 1E). On the other hand, in agreement with the crystal structure, the DCM/HCM-associated MVt R975W mutant showed a single binding site in solution (Fig. 1F). Consistently, the mechanisms of wild type and MVt R975W binding to PIP2 differ thermodynamically; whereas both are characterized by a negative Gibbs free energy (ΔG), the binding of PIP2 to MVt R975W is entropically driven, whereas for wild type, it is both entropically and enthalpically driven (SI Appendix, Table S5). Because R975 is mutated in both the quadruple mutant (to a Gln) and in the DCM/HCM-associated mutant (to a Trp) resulting in PIP2-bound but monomeric structures, we conclude that R975 is necessary for lipid-induced MVt dimerization but not for lipid binding.

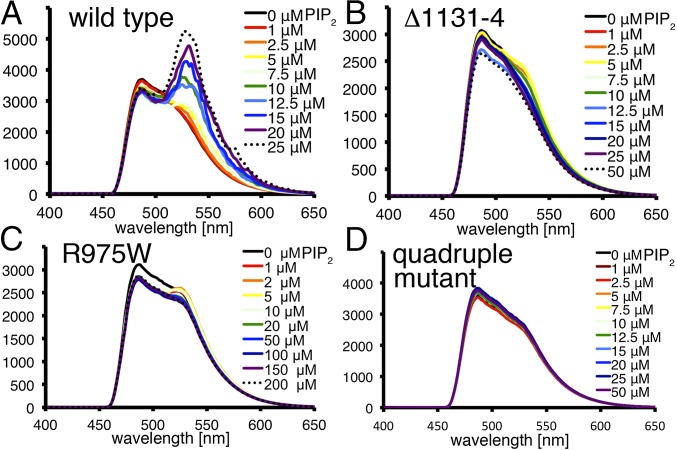

We confirmed the lipid-induced MVt dimerization in solution (Fig. 2) by using CFP- and YFP-tagged FRET probes as donor–acceptor pairs. For wild-type MVt, we observed a significant increase in emission peaks in the presence of lipid at 526 nm, indicating the energy transfer between the donor CFP-MVt and the acceptor YFP-MVt (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the three mutants that are monomeric in the crystal show similar emission spectra in the absence or with increasing amounts of PIP2, indicating that PIP2 does not induce dimerization (Fig. 2 B–D). Whereas the DCM/HCM-associated mutant R975W shows some FRET (<5% compared with wild type), the emission spectra of the FRET signal in the absence of PIP2 shows a spectral bleed through at 526 nm, which overlays with the emission spectra at the same wavelength for the CFP and YFP FRET pairs in the presence of PIP2. As FRET pairs are sensitive to both orientation and localization, the minimal FRET contributed by this DCM/HCM-associated mutant suggests the proximity of molecules due to nonspecific interactions.

Fig. 2.

PIP2-induced MV dimerization in solution. (A–D) PIP2 micelles induce dimerization of wild-type but not mutant MV. Emission spectra of CFP-MVt and YPF-MVt FRET pairs. (A) Wild type, (B) Δ1131–1134, (C) R975W, and (D) R975Q, K979Q, R1107Q, R1128Q mutant in the absence (black trace) and presence of increasing concentrations of PIP2 (colored spectrally; black dotted trace, highest concentration) upon excitation at 414 nm. The ordinate shows the relative fluorescence.

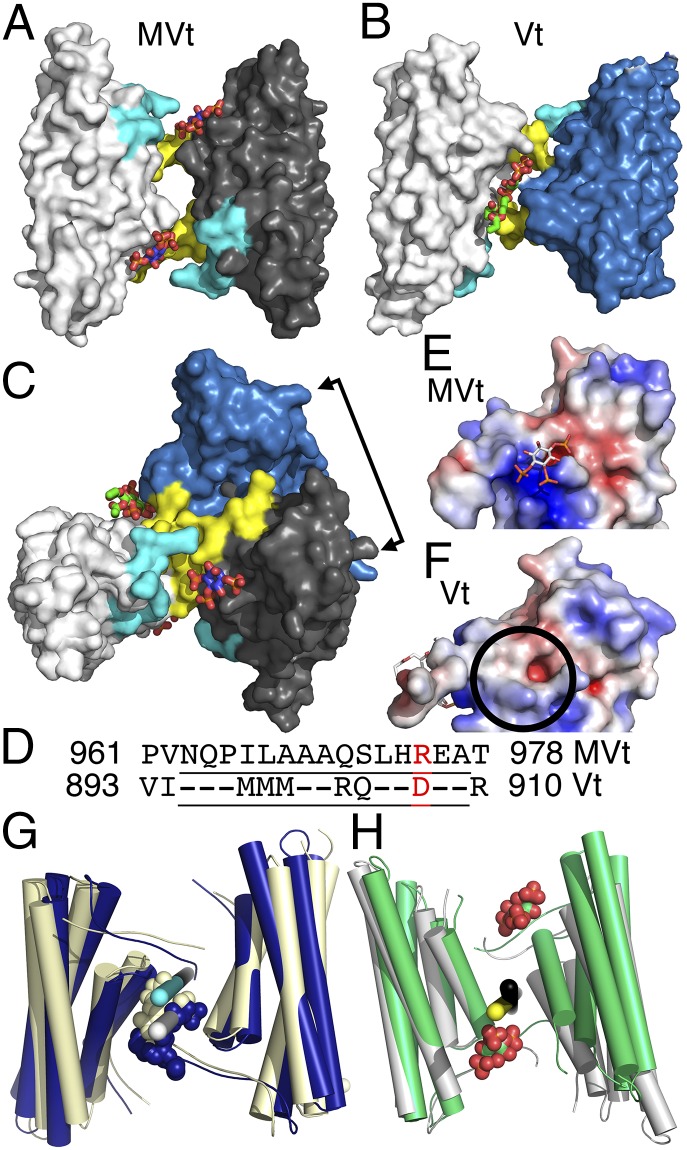

The Lipid-Induced Asymmetric Vinculin and Symmetric MV Dimer Interactions Are Quasi-Equivalent.

Comparison of both dimeric vinculin isoforms reveals that the MVt dimer is symmetric (180° subunit rotation), whereas the Vt dimer is asymmetric (∼160°/200° rotation). Whereas the lipid-induced domain swap is similar in the two vinculin isoforms (involving in particular the stacking of W1064 and H906 in Vt or equivalent W1132 and H974 in MVt), there are two PIP2 molecules bound to one face of the MVt dimer interface (Fig. 3A), while there is only one PIP2 (Fig. 3B) bound to the opposite face of the Vt dimer interface (Fig. 3C), suggesting that the Vt and MVt dimers bind the membrane in opposite orientations. Superposition of one Vt onto one MVt subunit results in a relative movement of about 75° for the second tail domains (Fig. 3C), reflected in distinct buried surface areas for MVt (∼488 Å2) and Vt (∼515 Å2) dimers. Strikingly, with the exception of MVt residue R975, which is mutated in DCM/HCM, all Vt and MVt residues involved in binding PIP2 are conserved (Fig. 3D and SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). Further, in the MVt/PIP2 dimer interface, PIP2 binds to residues R975, K979, R1107, and R1128 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 B and C) and of these four residues, only R975 is not conserved. In Vt, this position is occupied by an aspartate, which changes the electrostatic surface potential and thus the lipid-binding site (Fig. 3 E and F). Similarly to the principles of quasi-equivalence formulated by Caspar and Klug (43) to explain the architecture of virus capsids, distinct Vt and MVt dimers seem to be obtained by equivalent and quasi-equivalent interactions (SI Appendix, Table S6). Whereas Caspar and Klug (43) explained the architecture of virus particles with quasi-equivalent pentamers and hexamers from identical subunits, this idea has already been expanded to subunits with similar but not identical sequence with cubic or dodecahedral symmetry (44). In the case of meta/vinculin, there are only 11 residues that are different in the two 175-residue polypeptide chains (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). Aside from MVt residue R975 mentioned above, only Vt residues R903 and R910 engage in intermolecular interactions, whereas the corresponding residues in MVt (Q971 and T978) are solvent exposed. Indeed, mutating these MV residues to the corresponding vinculin residues (Q971R, R975D, and T978R) converts the symmetric MVt into an asymmetric Vt-like dimer with only one sandwiched PIP2 (Fig. 3G). Likewise, mutating vinculin residues to the corresponding MV residues (R903Q, D907R, and R910T) converts the asymmetric Vt, where the two subunits are related by an ∼160°/200° rotation, into a symmetric MVt-like dimer with two sandwiched PIP2 molecules (Fig. 3H), where the two subunits are related by a crystallographic 180° dyad. In another example of quasi-equivalent interactions, the mutated Vt dyad is slightly rotated compared with the MVt dyad (Fig. 3H), whereby the C termini (residues 1064–1066) are disordered, perhaps due to weaker secondary PIP2 binding (Fig. 1E). Thus, Vt residues R903, D907, and R910 and the corresponding MVt residues Q971, R975, and T978 are unique and dictate the symmetry of the dimer.

Fig. 3.

The PIP2-induced Vt dimer differs from PIP2-induced MVt dimer despite almost identical polypeptide chains via quasi-equivalent intermolecular contacts. (A) Surface representation of the MVt/PIP2 dimer. Individual subunits colored in white and gray, respectively. Each MV molecule binds one PIP2, resulting in a symmetric homodimer with PIP2 (shown as spheres; oxygen, red; carbon, blue) binding near the N terminus (residues 959–965, cyan) and C terminus (residues 1122–1134, yellow). (B) Surface representation of the Vt/PIP2 dimer. Individual subunits are colored in white and blue, respectively. One PIP2 molecule (carbon atoms, green) is sandwiched between two vinculin molecules, resulting in an asymmetric dimer. PIP2 interacts with the termini of both protomers. (C) Superposition of the MVt/PIP2 and Vt/PIP2 dimers rotated 90° down (or 90° up) with respect to the view shown in A (or B, respectively). The double arrow shows the relative (Vt versus MVt) movement of about 75° of the second protomer. (D) Structure-based sequence alignment of the region that differs in the two isoform tail domains. Residues residing on α-helix H1′ or H1 in MV and vinculin, respectively, are underlined. R975, which is mutated to a tryptophan in HCM/DCM and binds to PIP2 in MV, is highlighted in red and corresponds to D907 in vinculin, which is not in contact with PIP2. (E) Electrostatic surface potential representation of the PIP2-bound MVt protomer. The electrostatic potential gradient is from −5 to +5 kBT (red, negative; blue, positive), where kB is Boltzmann constant and T is the temperature. The positive electrostatic surface potential is mainly contributed by R1128, R975, R1107, and K979. (F) Electrostatic surface potential representation of the PIP2-bound Vt protomer. Aspartate 907 replaces arginine 975 of MVt, thereby generating a negative electrostatic potential at this site (circle). The PIP2 binding site in Vt is mainly contributed by K1061, K915, and K924. (G) Mutating Q971, R975, and T978 in MVt (light yellow) to the corresponding Vt residues (RDR) converts the lipid-induced symmetric MVt dimer into an asymmetric Vt-like dimer. The Vt/PIP2 dimer is superimposed and shown in blue, whereby one mutant MVt subunit (Left, light yellow) is superimposed onto one Vt subunit (Left, blue) highlighting the ∼160°/200° rotation axes for the mutated second MVt (white) or Vt (cyan), resulting in a relative movement of the second Vt (Right, blue) of 3° with respect to the second mutated MVt (Right, light yellow) via quasi-equivalent intermolecular interactions. (H) Mutating R903, D907, and R910 in Vt (gray) to the corresponding MVt residues (QRT) converts the lipid-induced asymmetric Vt dimer into a symmetric MVt-like dimer. One mutant Vt subunit (Left, gray) is superimposed onto one MVt subunit (Left, green) highlighting the 180° axes of the mutated Vt or MVt dyads (black and yellow, respectively), resulting in a relative movement of the second mutated Vt (Right, gray) of ∼20° with respect to the second MVt subunit (Right, green) via quasi-equivalent intermolecular interactions.

Equivalent and quasi-equivalent interactions are also seen for the second PIP2 binding site on α-helix H3. In the Vt/PIP2 structure, a third Vt molecule binds the PIP2 molecule via conserved K944 and R945. Significantly, mutating these residues to glutamines decreased the lipid binding capacity of Vt by 90% (38). This interaction is similar to that seen in the MVt/PIP2 structure (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). However, whereas PIP2 in Vt interacts with three Vt subunits and in particular with two K915 provided by two Vt subunits, in the MVt/PIP2 structure, the lipid only interacts with the conserved K983 (corresponding to vinculin residue K915) via crystal contacts.

The Lipid-Induced MV Dimerization Affects the Actin Cytoskeleton and Cell Migration.

To investigate the physiological role of lipid-induced MV dimerization, we exogenously expressed wild-type and monomeric Δ1131–1134 and DCM/HCM-associated R975W mutant GFP-tagged MV in vinculin-null cells. Confocal immunofluorescence studies demonstrated that wild-type MV reestablished a well-organized actin network (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). In contrast, whereas the expression of the monomeric GFP-MV Δ1131–1134 and R975W mutants resulted in localization to focal adhesions, their spreading was diminished and chaotic and they were impaired in restoring the actin cytoskeleton network.

Furthermore, to determine the effects of the lipid-induced dimerization on focal adhesions in these cells, we performed scratch-wound healing assays (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). Expression of wild-type MV suppressed the enhanced but chaotic wound closure typical of vinculin-null cells and led to a tighter closure of the wound. Cells expressing wild-type vinculin close a wound in 12–14 h (38), whereas the wild-type MV expressing mouse embryonic fibroblast cells showed 80–90% closure in 16 h, indicating that MV regulates focal adhesion turnover more tightly. In contrast, forced expression of dimerization-deficient Δ1131–1134 and R975W MV mutants led to rapid wound closure like vinculin-null cells, suggesting that focal adhesion turnover is not properly regulated.

Discussion

Vinculin is a key cytoskeletal adaptor protein that regulates cell adhesion and migration by linking the actin cytoskeleton to adhesion receptor complexes in cell adhesion sites. Dimerization is crucial for vinculin function because vinculin dimerization is required for and results in actin filament bundling (25, 36, 45). Thus, control of Vt conformation and dimerization are crucial for protein function in cell adhesion sites. Binding of PIP2 to the meta/vinculin tail domains results in a conformational change in MVt and Vt and dimer formation, whereby the disordered C termini bind to the first α-helix (H1′ and H1, respectively) of another five-helix bundle tail domain. This domain-swapped intermolecular interaction is strengthened by a tryptophan from one meta/vinculin molecule stacking onto a histidine from another meta/vinculin subunit. Significantly, R975 residing on α-helix H1′ in MV that binds to PIP2 is replaced by an aspartate in vinculin that is not involved in PIP2 binding to Vt and is the only amino acid that is not conserved in all combined, MVt or Vt, lipid binding residues in the crystal structures (46). Importantly, the DCM/HCM-associated mutant R975W binds PIP2 but does not dimerize. Thus, it seems that R975 in MV (or D907 in vinculin) dictates the type of dimer interaction induced by PIP2 binding and the difference in lipid-bound vinculin versus MV dimers resulting from equivalent and quasi-equivalent intermolecular interactions.

Next, deletion of the five C-terminal residues in Vt did not abrogate its ability to bind to PIP2 (47). Similarly, in our MVt Δ1131–1134 structure bound to PIP2, the lipid binding remains as seen in our wild-type MVt/PIP2 structure, yet in the absence of W1132, which stacks intermolecularly with H974 in the wild-type structure, the truncated MVt/PIP2 remains monomeric in the crystal and in solution (42). Thus, the C terminus seems necessary for lipid-induced dimerization but dispensable for lipid binding. Likewise, mutating the four PIP2 binding residues near the dimer interface results in a monomeric unbound mutant MVt structure, supporting the notion that lipid binding induces dimerization.

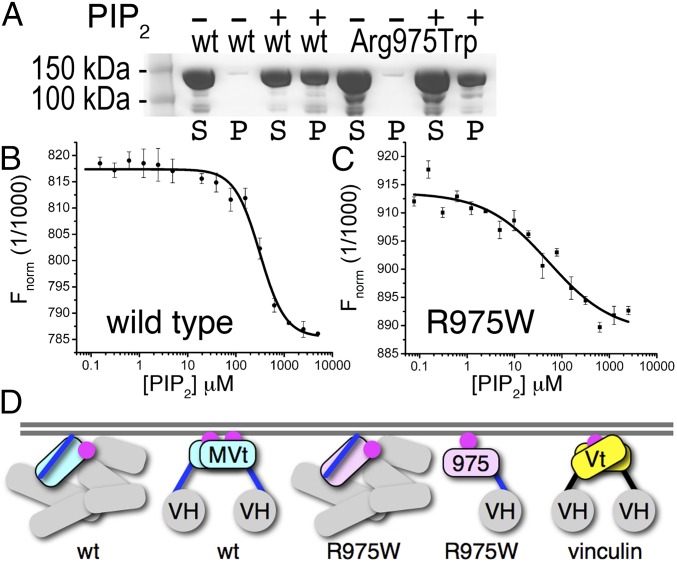

At focal adhesions, integrin binding to the extracellular matrix triggers mechanical force on associated talin molecules that exposes VBSs that activate vinculin, allowing binding to F-actin and thereby stabilizing nascent cell–matrix adhesions (48–50). Several mechanisms, binding partners, and modifications have been reported to sever the vinculin head–tail interaction and activate vinculin (46, 51). Lipids were originally thought to be involved in activating vinculin (34, 36) but inactive vinculin does not bind to PIP2 (38). Additionally, unlike for vinculin, the PIP2 binding site is accessible in the closed MV structure. Indeed, we obtained binding of PIP2 to full-length MV and the DCM/HCM R975W MV mutant (Fig. 4 A–C). Interestingly, the DCM/HCM-associated R975W mutant binds PIP2 with sixfold increased affinity (53 μM versus 313 μM).

Fig. 4.

Membrane attachment differs in the vinculin isoforms. (A) Lipid cosedimentation assays of human full-length wild type (first four lanes) and DCH/HCM-associated mutant R975W MV (last four lanes). P, pellet; S, supernatant; wt, wild type. (B and C) Microscale thermophoresis analyses show that PIP2 binds (B) wild-type MV and (C) the DCM/HCM-associated mutant MV with affinities of 313.8 ± 8.8 μM (SD n = 3) and 53.7 ± 3.4 μM (SD n = 3), respectively. (D) Full-length wild-type (wt) MV (individual VH domains, gray; MVt extended coil, blue; and five-helix MVt bundle, cyan) binds PIP2 (magenta) in its closed conformation. Upon activation, PIP2 induces MV dimerization by releasing the extended coil (VH, gray sphere). The DCM/HCM-associated MV R975W mutant (five-helix MVt bundle, pink) also binds PIP2 in its closed conformation but does not dimerize at the cell membrane. Finally, only activated vinculin (five-helix Vt bundle, yellow) binds PIP2, which induces dimerization.

Collectively, our data provide significant advances in our understanding of meta/vinculin dimerization, activation, and membrane attachment and important insights into the most severe DCM/HCM-associated MV mutant. We propose a mechanism where activated MV dimerizes at the cell membrane (Fig. 4D), whereas in DCM/HCM, inactive and active MV R975W bind the membrane without dimerizing, resulting perhaps in a decreased ability to stabilize cell adhesions. This model is supported by our observations that, in contrast to wild-type MV, expression of the R975W mutant in vinculin-null cells does not restore a well-organized actin cytoskeleton network and does not rescue the wound closure phenotype. Vinculin has recently been shown to reinforce the myocardial cytoskeleton, thereby improving contractility and prolonging life (52, 53). Our mechanistic insights will aid the development of drug therapies that strengthen the hearts of patients suffering from age-related heart failure.

Materials and Methods

Sample Preparation and Assays.

DNA constructs, sample preparation, and biochemical and cell biological analyses are described in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

X-Ray Crystallography.

All six distinct MVt/PIP2 crystals were obtained by using polyethylene glycol 3350 as the precipitating agent, whereas the mutant Vt/PIP2 crystals grew from 1.5 M lithium sulfate. Except for the MVt/PIP2 crystals that were cryoprotected in perfluoropolyether, all crystals were soaked in mother liquor that was supplemented with 25% glycerol. All X-ray diffraction data were collected at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory beam lines 22ID and 22BM or Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource 12–2 and integrated and scaled using XDS and SCALA as implemented in autoPROC (54). Phases for all six distinct MVt/PIP2 structures were calculated from a molecular replacement solution of the apo MVt structure (13), whereas the Vt structure in its tail-bound state (14) was used for the mutant Vt/PIP2 structure determination. Crystallographic refinement of all structures was performed using autoBUSTER (55).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to staff at Southeast Regional Collaborative Access Team and at Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource beamlines 12-2 and 11-1 for synchrotron support, Dipak N. Patil (The Scripps Research Institute) for help with crystallizing the quadruple mutant, and Douglas Kojetin (The Scripps Research Institute) for providing the microscale thermophoresis facility. This is publication no. 29250 from The Scripps Research Institute. K.C. is a fellow of the Children’s Tumor Foundation. T.I. is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Defense, and the American Heart Association, and by start-up funds provided to The Scripps Research Institute from the State of Florida.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. M.P.S. is a Guest Editor invited by the Editorial Board.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB entries 5L0C, MVt/PIP2; 5L0D, MVt D1131-4/PIP2; 5L0F, mutant MVt R975Q, K979Q, R1107Q, R1128Q; 5L0J, mutant Vt R903Q, D907R, R910T; 5L0G, mutant MVt Q971R, R975D, T978R; 5L0H, mutant MVt R975W/PIP2; and 5L0I, mutant MVt R975W).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1600702113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Xu W, Baribault H, Adamson ED. Vinculin knockout results in heart and brain defects during embryonic development. Development. 1998;125(2):327–337. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.2.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodríguez Fernández JL, Geiger B, Salomon D, Ben-Ze’ev A. Overexpression of vinculin suppresses cell motility in BALB/c 3T3 cells. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1992;22(2):127–134. doi: 10.1002/cm.970220206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coll JL, et al. Targeted disruption of vinculin genes in F9 and embryonic stem cells changes cell morphology, adhesion, and locomotion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(20):9161–9165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belkin AM, Ornatsky OI, Glukhova MA, Koteliansky VE. Immunolocalization of meta-vinculin in human smooth and cardiac muscles. J Cell Biol. 1988;107(2):545–553. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.2.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belkin AM, Ornatsky OI, Kabakov AE, Glukhova MA, Koteliansky VE. Diversity of vinculin/meta-vinculin in human tissues and cultivated cells. Expression of muscle specific variants of vinculin in human aorta smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 1988;263(14):6631–6635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rüdiger M, Korneeva N, Schwienbacher C, Weiss EE, Jockusch BM. Differential actin organization by vinculin isoforms: Implications for cell type-specific microfilament anchorage. FEBS Lett. 1998;431(1):49–54. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00723-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koteliansky VE, et al. An additional exon in the human vinculin gene specifically encodes meta-vinculin-specific difference peptide. Cross-species comparison reveals variable and conserved motifs in the meta-vinculin insert. Eur J Biochem. 1992;204(2):767–772. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maeda M, Holder E, Lowes B, Valent S, Bies RD. Dilated cardiomyopathy associated with deficiency of the cytoskeletal protein metavinculin. Circulation. 1997;95(1):17–20. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olson TM, et al. Metavinculin mutations alter actin interaction in dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2002;105(4):431–437. doi: 10.1161/hc0402.102930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vasile VC, et al. Identification of a metavinculin missense mutation, R975W, associated with both hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy. Mol Genet Metab. 2006;87(2):169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zemljic-Harpf AE, et al. Heterozygous inactivation of the vinculin gene predisposes to stress-induced cardiomyopathy. Am J Pathol. 2004;165(3):1033–1044. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63364-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borgon RA, Vonrhein C, Bricogne G, Bois PR, Izard T. Crystal structure of human vinculin. Structure. 2004;12(7):1189–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rangarajan ES, Lee JH, Yogesha SD, Izard T. A helix replacement mechanism directs metavinculin functions. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10679. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Izard T, et al. Vinculin activation by talin through helical bundle conversion. Nature. 2004;427(6970):171–175. doi: 10.1038/nature02281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Izard T, Vonrhein C. Structural basis for amplifying vinculin activation by talin. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(26):27667–27678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403076200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bois PR, Borgon RA, Vonrhein C, Izard T. Structural dynamics of α-actinin-vinculin interactions. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(14):6112–6122. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.6112-6122.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 17.Bois PR, O’Hara BP, Nietlispach D, Kirkpatrick J, Izard T. The vinculin binding sites of talin and α-actinin are sufficient to activate vinculin. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(11):7228–7236. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510397200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burridge K, Mangeat P. An interaction between vinculin and talin. Nature. 1984;308(5961):744–746. doi: 10.1038/308744a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wachsstock DH, Wilkins JA, Lin S. Specific interaction of vinculin with α-actinin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987;146(2):554–560. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)90564-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watabe-Uchida M, et al. α-Catenin-vinculin interaction functions to organize the apical junctional complex in epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1998;142(3):847–857. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.3.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng X, Cuff LE, Lawton CD, DeMali KA. Vinculin regulates cell-surface E-cadherin expression by binding to β-catenin. J Cell Sci. 2010;123(Pt 4):567–577. doi: 10.1242/jcs.056432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilkins JA, Lin S. High-affinity interaction of vinculin with actin filaments in vitro. Cell. 1982;28(1):83–90. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90377-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson RP, Craig SW. F-actin binding site masked by the intramolecular association of vinculin head and tail domains. Nature. 1995;373(6511):261–264. doi: 10.1038/373261a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burn P, Burger MM. The cytoskeletal protein vinculin contains transformation-sensitive, covalently bound lipid. Science. 1987;235(4787):476–479. doi: 10.1126/science.3099391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hüttelmaier S, Bubeck P, Rüdiger M, Jockusch BM. Characterization of two F-actin-binding and oligomerization sites in the cell-contact protein vinculin. Eur J Biochem. 1997;247(3):1136–1142. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.01136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hüttelmaier S, et al. The interaction of the cell-contact proteins VASP and vinculin is regulated by phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate. Curr Biol. 1998;8(9):479–488. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brindle NP, Holt MR, Davies JE, Price CJ, Critchley DR. The focal-adhesion vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) binds to the proline-rich domain in vinculin. Biochem J. 1996;318(Pt 3):753–757. doi: 10.1042/bj3180753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Demali KA. Vinculin: A dynamic regulator of cell adhesion. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29(11):565–567. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yogesha SD, Rangarajan ES, Vonrhein C, Bricogne G, Izard T. Crystal structure of vinculin in complex with vinculin binding site 50 (VBS50), the integrin binding site 2 (IBS2) of talin. Protein Sci. 2012;21(4):583–588. doi: 10.1002/pro.2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yogesha SD, Sharff A, Bricogne G, Izard T. Intermolecular versus intramolecular interactions of the vinculin binding site 33 of talin. Protein Sci. 2011;20(8):1471–1476. doi: 10.1002/pro.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Izard T, Tran Van Nhieu G, Bois PR. Shigella applies molecular mimicry to subvert vinculin and invade host cells. J Cell Biol. 2006;175(3):465–475. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200605091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park H, Valencia-Gallardo C, Sharff A, Tran Van Nhieu G, Izard T. Novel vinculin binding site of the IpaA invasin of Shigella. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(26):23214–23221. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.184283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nhieu GT, Izard T. Vinculin binding in its closed conformation by a helix addition mechanism. EMBO J. 2007;26(21):4588–4596. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilmore AP, Burridge K. Regulation of vinculin binding to talin and actin by phosphatidyl-inositol-4-5-bisphosphate. Nature. 1996;381(6582):531–535. doi: 10.1038/381531a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weekes J, Barry ST, Critchley DR. Acidic phospholipids inhibit the intramolecular association between the N- and C-terminal regions of vinculin, exposing actin-binding and protein kinase C phosphorylation sites. Biochem J. 1996;314(Pt 3):827–832. doi: 10.1042/bj3140827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bakolitsa C, de Pereda JM, Bagshaw CR, Critchley DR, Liddington RC. Crystal structure of the vinculin tail suggests a pathway for activation. Cell. 1999;99(6):603–613. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81549-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.del Rio A, et al. Stretching single talin rod molecules activates vinculin binding. Science. 2009;323(5914):638–641. doi: 10.1126/science.1162912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chinthalapudi K, et al. Lipid binding promotes oligomerization and focal adhesion activity of vinculin. J Cell Biol. 2014;207(5):643–656. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201404128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shen K, et al. The vinculin C-terminal hairpin mediates F-actin bundle formation, focal adhesion, and cell mechanical properties. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(52):45103–45115. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.244293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson RP, Craig SW. Actin activates a cryptic dimerization potential of the vinculin tail domain. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(1):95–105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Witt S, Zieseniss A, Fock U, Jockusch BM, Illenberger S. Comparative biochemical analysis suggests that vinculin and metavinculin cooperate in muscular adhesion sites. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(30):31533–31543. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314245200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chinthalapudi K, Patil DN, Rangarajan ES, Rader C, Izard T. Lipid-directed vinculin dimerization. Biochemistry. 2015;54(17):2758–2768. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caspar DL, Klug A. Physical principles in the construction of regular viruses. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1962;27:1–24. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1962.027.001.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Izard T, et al. Principles of quasi-equivalence and Euclidean geometry govern the assembly of cubic and dodecahedral cores of pyruvate dehydrogenase complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(4):1240–1245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Janssen ME, et al. Three-dimensional structure of vinculin bound to actin filaments. Mol Cell. 2006;21(2):271–281. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Izard T, Brown DT. Mechanisms and functions of vinculin interactions with phospholipids at cell adhesion sites. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(6):2548–2555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.686493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Palmer SM, Playford MP, Craig SW, Schaller MD, Campbell SL. Lipid binding to the tail domain of vinculin: Specificity and the role of the N and C termini. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(11):7223–7231. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807842200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Galbraith CG, Yamada KM, Sheetz MP. The relationship between force and focal complex development. J Cell Biol. 2002;159(4):695–705. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200204153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Giannone G, Jiang G, Sutton DH, Critchley DR, Sheetz MP. Talin1 is critical for force-dependent reinforcement of initial integrin-cytoskeleton bonds but not tyrosine kinase activation. J Cell Biol. 2003;163(2):409–419. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zaidel-Bar R, Ballestrem C, Kam Z, Geiger B. Early molecular events in the assembly of matrix adhesions at the leading edge of migrating cells. J Cell Sci. 2003;116(Pt 22):4605–4613. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brown DT, Izard T. Vinculin-cell membrane interactions. Oncotarget. 2015;6(33):34043–34044. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.DeLeon-Pennell KY, Lindsey ML. Cardiac aging: Send in the vinculin reinforcements. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(292):292fs26. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab3391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaushik G, et al. Vinculin network-mediated cytoskeletal remodeling regulates contractile function in the aging heart. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(292):292ra99. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa5843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vonrhein C, et al. Data processing and analysis with the autoPROC toolbox. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67(Pt 4):293–302. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911007773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bricogne G, et al. BUSTER version 2.9. Global Phasing; Cambridge, UK: 2011. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.