Significance

Regulatory signals between protein subunits depend on communication between sequential binding events. How such long-range communication, or allostery, operates at the subdomain level has been elusive, especially for homooligomeric proteins. To address this problem, homodimers of thymidylate synthase were generated for optimized study of individual protomers of the singly bound dimer. Mixed 15N-labeled dimers were created with a single functional active site, allowing site-specific, protomer-specific chemical shifts to report on step-wise binding effects. Long-range intersubunit communication was observed although this communication was apparent only in the second ligand-binding step, in which changes were in the first ligand-bound region. Visualization of up to four peaks for each residue amide provides a unique way to assess the allosteric mechanism.

Keywords: homodimer, subunit communication, allostery, NMR, thymidylate synthase

Abstract

Allosteric communication is critical for protein function and cellular homeostasis, and it can be exploited as a strategy for drug design. However, unlike many protein–ligand interactions, the structural basis for the long-range communication that underlies allostery is not well understood. This lack of understanding is most evident in the case of classical allostery, in which a binding event in one protomer is sensed by a second symmetric protomer. A primary reason why study of interdomain signaling is challenging in oligomeric proteins is the difficulty in characterizing intermediate, singly bound species. Here, we use an NMR approach to isolate and characterize a singly ligated state (“lig1”) of a homodimeric enzyme that is otherwise obscured by rapid exchange with apo and saturated forms. Mixed labeled dimers were prepared that simultaneously permit full population of the lig1 state and isotopic labeling of either protomer. Direct visualization of peaks from lig1 yielded site-specific ligand-state multiplets that provide a convenient format for assessing mechanisms of intersubunit communication from a variety of NMR measurements. We demonstrate this approach on thymidylate synthase from Escherichia coli, a homodimeric enzyme known to be half-the-sites reactive. Resolving the dUMP1 state shows that active site communication occurs not upon the first dUMP binding, but upon the second. Surprisingly, for many sites, dUMP1 peaks are found beyond the limits set by apo and dUMP2 peaks, indicating that binding the first dUMP pushes the enzyme ensemble to further conformational extremes than the apo or saturated forms. The approach used here should be generally applicable to homodimers.

Allosteric regulation in proteins is a ubiquitous mechanism for controlling cellular behavior and an attractive strategy for therapeutic development. Even though broadly recognized, long-range communication is not well understood mechanistically (1–4). Although there have been numerous strategies to reveal the structural and dynamic underpinnings of allostery, oddly these strategies have largely focused on complex oligomeric or, alternatively, on small monomeric allosteric proteins. A likely more straightforward approach is to study allosteric mechanisms using simple symmetric homodimeric proteins, which would allow for answering the basic and general question of how the occurrence of an event in one subunit is communicated to another subunit, as occurs in classical multisubunit allosteric proteins. Given the large number of homodimeric proteins involved in cellular regulation (such as growth factors, cytokines, kinases, G protein-coupled receptors, transcription factors, and metabolic proteins), insights into intersubunit communication should be widely beneficial (5).

As a key step toward a broad understanding of allosteric mechanisms, it will be important to observe how binding a ligand in one subunit is communicated to a second subunit, even in the absence of conformational change. Although this communication is straightforward in specific cases of two differing neighboring domains or heterodimers in which domains have distinct ligands (6–8), it is more elusive for the common case of symmetric homodimers. Homodimers present a challenge because it is difficult to either observe individual protomers or study states with a single ligand bound (referred to here as “lig1”) because of dynamic binding equilibria. Having a method to isolate lig1 homodimers would facilitate detailed study of intersubunit communication and allostery by high resolution structural methods. A well-established approach for mapping communication networks in proteins is NMR spectroscopy, most commonly using so-called chemical shift perturbation (CSP) (9, 10). In the case of homodimers, however, tracking CSPs or making additional measurements on lig1 peaks (or resonances) becomes problematic because (i) resonances from symmetric protomers can overlap, (ii) resonances are frequently in fast or intermediate exchange on the NMR timescale, especially in dimeric enzymes where substrate affinities are low to moderate, and, most importantly, (iii) unless ligand binding is highly negatively cooperative, there will be additional resonances from apo (lig0) and doubly bound (lig2) states. In principle, monitoring lig1 states is most easily carried out in highly negatively cooperative systems although, even in the few reported cases, most lig1 resonances were not well resolved (11, 12). A general, experimental format for monitoring specific peaks (or sites) in both bound and empty protomers for lig1 states will therefore help advance our understanding of intersubunit communication and allostery in homodimers (and potentially higher order oligomers).

Escherichia coli thymidylate synthase (TS), a 62-kDa symmetric homodimer, presents a favorable example for lig1 studies by NMR. TS catalyzes the synthesis of the sole source of 2′-deoxythymidine-5′-monophosphate (dTMP) via a multistep mechanism involving reductive methylation of dUMP using N5,N10-methylene-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrofolate (mTHF) as both a methylene and hydride donor. In addition, TS is half-the-sites reactive (13–15), with substrate binding sites separated by 35 Å, leading to an expectation for negative substrate binding cooperativity between protomers. Although dUMP was recently shown to bind with minimal cooperativity for the E. coli enzyme at 25 °C, there are signs of unequal thermodynamics between the two protomers at lower temperatures (16), and indeed data herein show clear intersubunit communication. Moreover, other TS enzymes, and in particular human, seem to show more dramatic cooperativity, suggesting that intersubunit communication is an intrinsic feature of TS (13, 17–21). To overcome the difficulties of studying symmetric proteins by NMR, we generated a pair of mixed labeled dimers of TS that each have a single functional active site and a single protomer labeled for NMR studies. These complementary mixed dimers allow for determining protomer-specific responses to a single dUMP binding event by isolating the dUMP1 state. In the presence of dUMP, the mixed dimers revealed dUMP1 peak positions normally hidden in WT (wild-type) dimer titrations and highlighted the important differences between the two dUMP binding events. These data also allow construction of complete “ligand state peak multiplets” that reflect the responses of residues on both sides of the interface. Most notably, we show that there is communication between the two active sites primarily upon binding the second dUMP because this binding event causes perturbations in the already-bound first site.

Materials and Methods

Protein Expression and Purification.

WT and double mutant R126E, R127E (RREE) thymidylate synthase from E. coli was expressed and purified as described in SI Materials and Methods.

Generation of TS Mixed Dimers.

Preparation of specific labeled mixed dimers was accomplished in vitro by mixing purified WT and RREE homodimers, in 2 M urea at pH 9, to reapportion the monomers yielding three species: WT and RREE homodimers and a mixed dimer with one WT and one RREE monomer. The mixed dimer was then separated from the parent homodimers by anion exchange chromatography. For NMR studies, two different preparations of mixing were made to isolate both species of mixed dimers: one where the binding subunit is U-[2H, 15N]–labeled (mix RREE-labeled with WT-unlabeled) and one where the nonbinding subunit is U-[2H, 15N]–labeled (mix WT-labeled with RREE-unlabeled). For full details, see SI Materials and Methods.

NMR Spectroscopy.

Standard transverse relaxation-optimized spectroscopy (TROSY) triple resonance and 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) experiments were used for backbone resonance assignment experiments and ligand titrations, respectively, as described in SI Materials and Methods.

SI Materials and Methods

Protein Expression and Purification.

Escherichia coli thymidylate synthase was cloned into the pET21a and transformed into BL21 star (DE3) cells. The WT and double mutant R126E, R127E (RREE) were expressed in 1 L of LB for unlabeled preparations, or in 1 L of M9 (99.8% D2O; CIL) media, for labeled preparations, supplemented with 1 g of 15NH4Cl (CIL) and 2 g of either U-[2H]-glucose or U-[13C, 2H]-glucose (CIL) (for dUMP titrations and backbone resonance assignments, respectively) as the sole nitrogen and carbon sources, respectively. Cells were grown at 37 °C to OD600 of 0.8, at which point 0.75 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside was added and protein was expressed for 24 h at 18 °C. Cells were harvested, and TS was purified as described (30) with some modifications. The cell pellet from 1 L of cell culture was suspended in 50 mL of 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM DTT and sonicated on ice four times for 4 min, followed by 4 min rest each time. Then, 5 mL of 5% (wt/vol) streptomycin sulfate was added and stirred for 10 min, followed by centrifugation at 27,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C to remove cell debris and nucleic acids. Solid ammonium sulfate was added to 50% saturation, and the solution was stirred for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 27,000 × g for 30 min, after which the pellet was discarded. Solid ammonium sulfate was added to the supernatant to 80% saturation with stirring for 1 h and subsequent centrifugation. The ammonium sulfate pellet was dissolved in 50 mL of DEAE buffer [25 mM sodium phosphate, 10% (wt/wt) glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT, and 0.02% NaN3 at pH 7.4] and dialyzed overnight at 4 °C against the same buffer. Then, 1 L of DEAE buffer was used to equilibrate a DEAE column, and 0.5 L of DEAE buffer with 0.25 M NaCl was used as the elution buffer, with a gradient of 0–100% elution buffer to elute TS. Fractions containing protein were run over a Superdex G75 size exclusion column equilibrated with NMR buffer (25 mM sodium phosphate, 0.165 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT, and 0.02% NaN3 at pH 7.5). G75 fractions containing pure TS as determined by SDS/PAGE were pooled. TS activity was assayed as described to determine functionality (31). The concentration of the TS dimer was determined using ε280 = 103,820 L·mol−1 ·cm−1.

Generation of TS Mixed Dimers.

Subunit mixing was initiated by diluting WT and RREE to a final total protein concentration of 6 µM, with fivefold molar excess of unlabeled protein to maximize yield, into 25 mM Tris, 0.15 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM DTT, 2 M urea, pH 9.0, at 4 °C for 72 h. Mixing was stopped by dialysis against urea removal buffer (20 mM Tris, 0.15 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 5 mM DTT, pH 9.0, at 4 °C) for 24 h with one buffer change. TS was neutralized by dialysis against DEAE buffer with added 0.15 M NaCl for 12 h, followed by a second dialysis step against DEAE buffer with added 0.3 M NaCl for 12 h. Mixed TS species were then separated by ion exchange chromatography. The double arginine mutation sufficiently alters the subunit charge to facilitate chromatographic separation of the mixed dimer (WT/RREE) from the two parent homodimers (WT/WT and RREE/RREE), similar to that shown previously (32), although this mixing procedure was on a significantly larger scale, requiring more efficient separation. Chromatography conditions were influenced by chromatofocusing techniques to allow for high resolution separation of the three species, which have small differences in pI, over a narrow elution gradient (33, 34). Buffer conditions were chosen to use a monovalent buffering species with a buffering range that encompasses the pI of each protein species, which allows for a more consistent pH gradient over the entire elution range. TS was dialyzed overnight against Q buffer (25 mM Bis-Tris, 0.1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT, pH 7.0, at 4 °C). One liter of Q buffer was used as the equilibration buffer, and 1 L of Q buffer with added 0.2 M NaCl was used as the elution buffer. Alternating linear gradients and isocratic steps of NaCl were used to separate the three species from a Source 15Q (GE) ion exchange column. This alternating elution scheme was chosen so that the three species could be baseline-separated using a shallow salt gradient, regardless of which homodimer was in excess. An initial steep gradient was chosen to quickly elute the WT homodimer during the subsequent isocratic step. After the WT homodimer was eluted, the gradient was shallowed to improve resolution. This shallower gradient resulted in increased retention time of the other two species, resulting in minor peak broadening.

When stored in the absence of urea, the mixed dimers do not disproportionate, as evidenced by chromatography, which is consistent with the tight association of the dimer.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry.

TS was buffer-exchanged into ITC buffer (25 mM sodium phosphate, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM Tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride, pH 7.5, at 25 °C) over a Sephadex G25 (GE) size exclusion column. The protein samples were concentrated to 100, 150, or 200 µM as determined by UV spectrophotometry. Samples were centrifuged at 11,500 × g for 1 min to remove any aggregates, and the concentrations were again measured before loading into the ITC. Dry dUMP was dissolved in ITC buffer to a concentration of 20 or 30 molar excess of protein concentration. The concentration of dUMP was then measured spectrophotometrically to confirm the correct concentration. ITC experiments were conducted on a MicroCal AutoITC 200. Experiments had an initial 0.2-µL injection of dUMP followed by 19 2-µL injections. dUMP binding to the mixed dimer was measured for multiple protein:dUMP ratios, and the mixed dimer isotherms were fit to a single site binding model in Origin. Given that the mixed dimer has a single functional binding site, a fitted stoichiometry close to one was expected. WT TS recovered from mixing was run as a control to correct for protein concentration to account for the active fraction of TS postmixing.

NMR Spectroscopy.

Back exchange.

For NMR studies, deuterons were fully back-exchanged to protons as described (35).

TS was added to cold exchange buffer (20 mM Tris, 0.15 M NaCl, 2 M Urea, 1 mM EDTA, and 10 mM DTT, pH 9.0, at 4 °C) to a final enzyme concentration of 2 µM and stirred in the cold for 6 d. The enzyme solution was dialyzed against 4 L of urea removal buffer for 8 h in the cold. The enzyme solution was then dialyzed for 8 h against urea removal buffer with an additional 0.15 M NaCl at 4 °C. TS was neutralized by dialysis against DEAE buffer with added 0.45 M NaCl for 8 h. Finally, the protein was buffer-exchanged into NMR buffer over a Sephadex G25 (GE) size exclusion column.

Data collection.

For backbone resonance assignments of apo and dUMP saturated, a 0.5 mM (dimer) sample of U-[2H, 13C, 15N] TS was prepared in NMR buffer supplemented with 5% (vol/vol) D2O. Six TROSY triple resonance experiments were acquired on the samples: HNCO, HN(CA)CO, HN(CO)CA, HN(COCA)CB, HNCA, and HN(CA)CB. Data were acquired at 25 °C on a Bruker Avance III 600-MHz spectrometer equipped with a TCI cryoprobe. For dUMP titrations on WT and mixed dimers, 1H-15N TROSY HSQC spectra were acquired at 25 °C on an 850-MHz Bruker Avance III spectrometer equipped with a TCI cryoprobe. For titrations, the TS concentration was 100–200 µM, and dUMP was added up to 40-fold molar excess to ensure complete saturation.

Lig1 State Peak Assignments.

Resonances for the dUMP1 states were assigned by peak proximity from dUMP titrations of the two mixed dimer species using the apo RREE homodimer along with apo and dUMP2 assignments. For most residues in each of the mixed dimers, one (or both) of the two resonances, apo (Fig. 1D) or dUMP1, could be unambiguously determined by proximity to a WT apo or dUMP2 peak. The other resonance could then be determined from a dUMP titration. To assign diligand1 resonances, a complex with one molar equivalent of 5F-dUMP and CH2H4Fol per WT TS dimer was prepared. This sample contained fractions of apo, diligand1, and diligand2 TS. The ligand-to-enzyme ratio was chosen to give the highest population of diligand1 TS based on our previous determination of the relative affinities of the two binding sites (16). Because this complex is a covalent complex, bound resonances are in slow exchange on the NMR timescale, and peaks from diligand1 forms are observed directly. Different amides of this half-saturated diligand complex give rise to the following resonance classes in TROSY HSQC spectra: (i) resonances whose positions are not affected by binding, (ii) doublets, in which resonances from the empty and bound subunits of the diligand1 state overlap with resonances of the symmetrical apo enzyme and diligand2, respectively, and (iii) quartets with separate resonances from each of the following: apo, diligand2, diligand1empty, and diligand1bound. Quartet resonances from the diligand1 complex were assigned with the help of a TROSY-HSQC spectrum of a WT-labeled mixed dimer bound to diligand in addition to TROSY HNCA, HN(CO)CA, HN(CA)CB, and HN(COCA)CB of a WT sample with one equivalent of diligand.

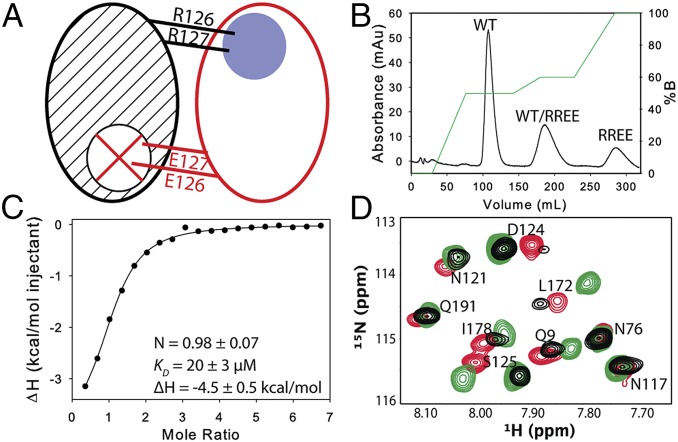

Fig. 1.

Characterization of the mixed dimers. (A) Schematic of a mixed labeled dimer showing the sites of mutation. The WT subunit (black) is 15N-labeled (hashed), and the RREE mutant subunit (red) is unlabeled. The blue circle and red X indicate the functional and nonfunctional binding site, respectively. (B) Chromatogram showing separation of the three species using anion exchange. (C) dUMP binding to the mixed dimer was measured by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC); mean and SD are from three replicates. For the selected isotherm, mixed dimer concentration was 150 μM with 3 mM dUMP in the syringe. (D) Overlay of HSQC spectra of apo WT (black), WT-labeled (green), and RREE-labeled (red) mixed dimers. Residues proximal to the mutation are D124 and S125 in the RREE-labeled and L172 in the WT-labeled mixed dimers.

Chemical Shift Correction to Account for Effects of Mutation.

The mixed dimers allow for chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) for the first dUMP binding event to be measured independently for each subunit. CSPs were calculated as follows:

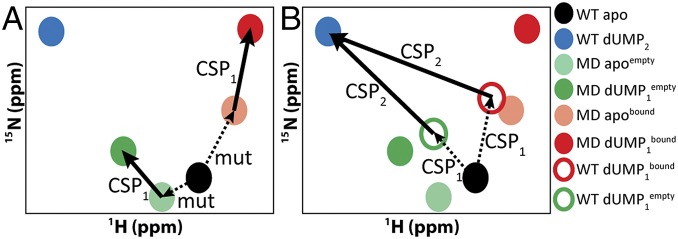

For the dUMP1 state, the CSPs were directly calculated from the chemical shift change of each of the dUMP-bound mixed dimers. The CSPs of the bound subunit, dUMP1bound, were calculated from the chemical shift change upon binding dUMP to the apo RREE-labeled, WT-unlabeled mixed dimer (light red-apo and dark red-dUMP bound in Fig. 3A). The CSPs of the empty subunit, dUMP1empty, were calculated from the chemical shift change upon binding dUMP to the apo WT-labeled, RREE-unlabeled mixed dimer (light green-apo and dark green-dUMP bound in Fig. 3A). For the second dUMP-binding event, the CSPs could not be directly calculated from the dUMP1 mixed dimers and WT dUMP2 because of the effect of the RREE mutation. To account for the mutational effects, we used a vector correction to reconstruct the dUMP1 peak positions for WT. Here, we assumed that the dUMP1empty and dUMP1bound chemical shift changes, denoted CSP1 in Fig. 3, measured from the mixed dimers, are equal to the dUMP1empty and dUMP1bound chemical shift changes for WT. We also assumed that the effect of the mutation on the chemical shift, mut in Fig. 3A, is the same for both apo and dUMP1. Based on these assumptions, we could use the CSP1 vectors as the basis for reconstructing WT dUMP1 peak positions using WT apo as the vector origin (open circles in Fig. 3B). From these corrected peak positions, the CSPs upon binding the second dUMP, CSP2, could be directly calculated as before (Fig. 3B). This vectorial treatment of dUMP1 chemical shifts to account for the effects of the mutation was cross-validated using the known chemical shifts of the WT diligand1 complex (Fig. S2).

Fig. 3.

Vector correction to determine WT dUMP1 peak positions. The two schematic diagrams show how CSPs were calculated for each dUMP binding event (SI Materials and Methods). (A) The CSPs for binding the first dUMP, CSP1, were calculated directly from the apo and dUMP1 peak positions of the two mixed labeled dimer (MD) samples (thick arrows). Dashed arrows show the CSP due to the mutation (mut). (B) CSPs for binding the second dUMP, CSP2, were calculated as the vectors connecting the WT dUMP2 peak (in blue) and the dUMP1 peaks for WT (empty red and green circles), which were reconstructed by applying the CSP1 vectors to the apo WT peak (dashed arrows).

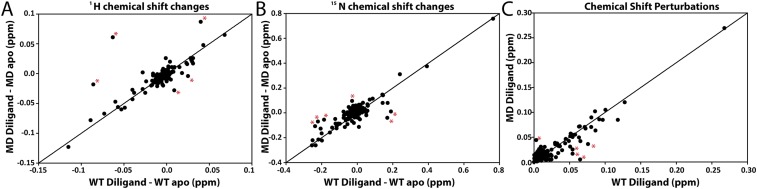

Fig. S2.

Cross-validation of the mixed dimer strategy using a singly bound diligand. Chemical shift changes measured for the empty subunit of a mixed dimer bound with diligand were compared with those for the empty subunit of WT TS bound with diligand (1 molar equivalent of diligand per TS dimer). Correlations for (A) 1H chemical shifts, (B) 15N chemical shifts, and (C) 1H-15N CSPs are shown with outliers marked with an asterisk. The line represents a correlation coefficient of 1.

Use of the Diligand1 Complex to Validate Mixed Dimer Strategy.

To justify use of the mixed dimer bound to dUMP as a proxy for the true WT dUMP1, we validated the CSP vector correction (Fig. 3) to show that the observed chemical shifts upon binding dUMP are dominated by ligand binding, with minimal contribution from mutational effects. We used a WT diligand complex as our reference because the resonances are in slow exchange on the NMR timescale, which allows for accurate determination of the chemical shifts of apo, diligand1 and diligand2 species. We used a complex with one molar equivalent of diligand per TS dimer to maximize the population of diligand1. This complex gave rise to peak quartets where the chemical shifts of all four states, apo, diligand1empty, diligand1bound, and diligand2, could be directly measured (16). The same mole ratio was used in a mixed labeled dimer (WT-labeled, RREE-unlabeled) diligand complex, which allowed for direct comparison of WT and mixed dimer diligand1 chemical shifts and provided an accurate assessment of the validity of the vector correction method. We chose to compare diligand1empty chemical shifts because the empty subunit of the mixed dimer is most affected by the mutation (Fig. 1A). In total, a shared set of 139 residues was measured for both complexes, and the correlations in 1H, 15N, and CSP were determined (Fig. S2). All three correlation plots, in Fig. S2, show a tight grouping of chemical shifts along the diagonal, with rmsds of 0.01, 0.05, and 0.01 ppm, respectively, with only a few outliers. The CSP correlation shows that the mixed dimer ternary complex tends to be less effected by the diligand than does the WT. Overall, these data show that the presence of the mutations and the creation of the mixed dimer do not overly perturb its behavior and support the validity of the mixed dimer strategy to monitor ligation states that are otherwise intractable by NMR in this system.

Results

Generation and Characterization of Mixed Dimers.

To study intersubunit communication in a homodimeric protein, we sought to use NMR to investigate the effect that binding of the first ligand has on both subunits of thymidylate synthase. Study of lig1 states, however, requires overcoming two primary degeneracies. The first is that addition of ligand to populate the lig1 state is typically accompanied by population of lig0 and lig2 states, and accordingly, more complex spectra. The second is that, for symmetric protein dimers, it can be difficult to spectroscopically distinguish between the bound and empty protomers (or subunits). Our strategy was to break these degeneracies by creation of mixed 15N-labeled dimers that (i) can bind substrate only in one protomer, and (ii) have only a single protomer labeled for NMR detection, allowing for two complementary lig1 dimer samples, one with the bound subunit 15N-labeled and a second lig1 sample with the empty subunit 15N-labeled.

Mixed labeled dimers with a single functional active site were prepared by first abolishing substrate binding with an active site mutation (R126E, R127E). Mixing this inactive, purified homodimer with purified 15N-labeled WT homodimer yielded three species, one of which is the mixed dimer with the nonfunctional subunit (the WT) 15N-labeled (Fig. 1A) (note that the mutation at positions 126–127 abolishes binding to the opposite subunit because the loop bearing the arginine mutations forms critical interactions with dUMP in the opposite subunit). Labeling of the functional subunit is achieved by 15N-labeling the mutant enzyme and subsequent mixing with unlabeled WT (and purification from the two homodimers) (Fig. 1B). Binding of dUMP to the mixed dimer, measured by isothermal titration calorimetry (Fig. 1C), was similar to the WT (ΔH1 of −4.5 kcal/mol, ΔH2 of −4.4 kcal/mol and KD1= KD2 of 16 µM) (16). HSQCs of the apo mixed dimers showed that the mutation primarily affects nearby residues, with minimal effects on distal sites (Fig. 1D). With this pair of mixed labeled dimers, addition of dUMP yielded lig1 samples with 15N chemical shift probes distributed throughout the bound or empty subunit, enabling subunit-specific tracking of ligand-binding effects without interference from dUMP0 or dUMP2.

Imbalanced Chemical Shift Response to dUMP Binding.

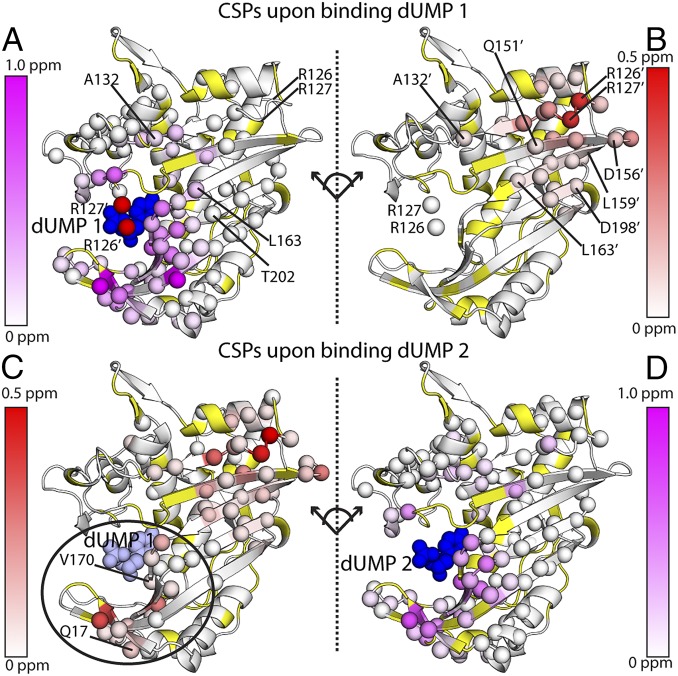

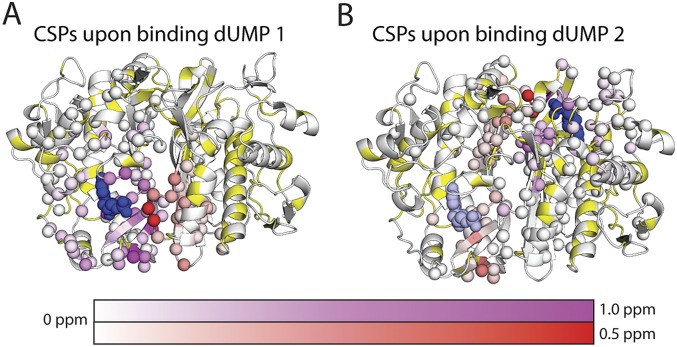

With the two mixed dimers, we characterized the subunit-specific effects of the first and second dUMP binding events using standard chemical shift perturbations (CSPs). 1H-15N CSPs due to the first dUMP binding event were calculated directly from the mixed labeled dimers to monitor perturbations in each subunit. The bound subunit of dUMP1 showed large CSPs in the binding site, dropping off ∼20 Å from dUMP, with smaller perturbations extending along the interface, out to ∼28 Å from dUMP (Fig. 2A). The empty subunit was largely unaffected, dropping off ∼15 Å from dUMP, with all of the CSPs in the dUMP binding loop (residues 123′–128′, where prime indicates the empty subunit) and the backside of the binding site (residues 150′–163′) (Fig. 2B). Overall, the effects of binding the first dUMP were highly localized, primarily to the binding region, with small perturbations to the dimer interface (Fig. S1A).

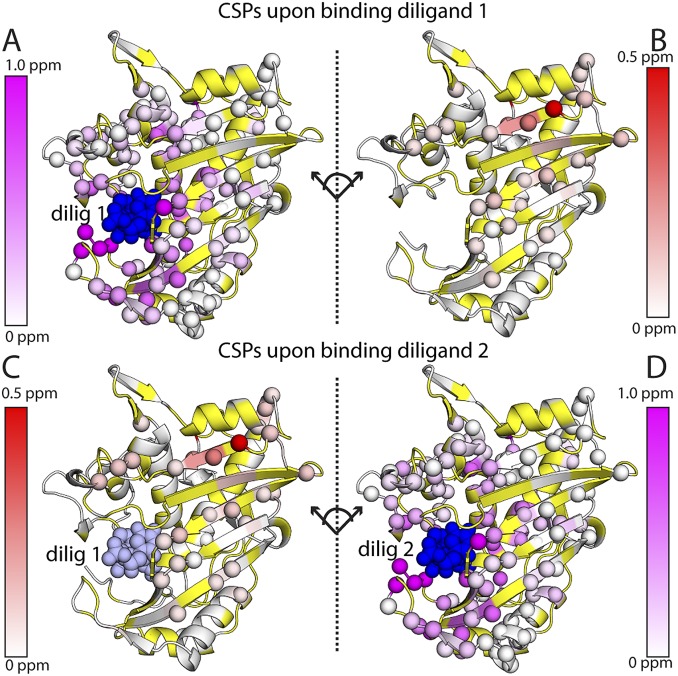

Fig. 2.

Chemical shift perturbations of the two dUMP binding events. The effects of binding the first dUMP to the binding (A) and nonbinding (B) subunits of the dimer are shown at the Top, using the CSP scheme shown in Fig. 3A. The effects of binding the second dUMP to the nonbinding (C) and binding (D) subunits are shown at the Bottom, using the reconstructed WT CSPs shown in Fig. 3B. Viewing the dimer interface region is enhanced by separating the two subunits, where the subunits on the right underwent a hinge-type rotation (dotted line) to yield the same viewing angle as those on the left. As a reference point for the rotation, the red (A) and white (B) spheres show the locations of R126 and R127 from the other subunit. Residues with significant CSPs are shown as spheres. Residues that are missing or unassigned are in yellow. Annotated residues are discussed in Figs. 4 and 5, where residues denoted prime (e.g., R126′) correspond to the empty subunit of the dUMP1 state. The first bound (dUMP 1) and second bound (dUMP 2) dUMPs are shown in dark blue; for binding of dUMP 2 (Bottom), the previously bound dUMP 1 is shown in light blue. In C, the circle highlights the major difference in the distant subunit response for binding of dUMP 1 and dUMP 2. The CSPs in context of the full dimer are shown in Fig. S1.

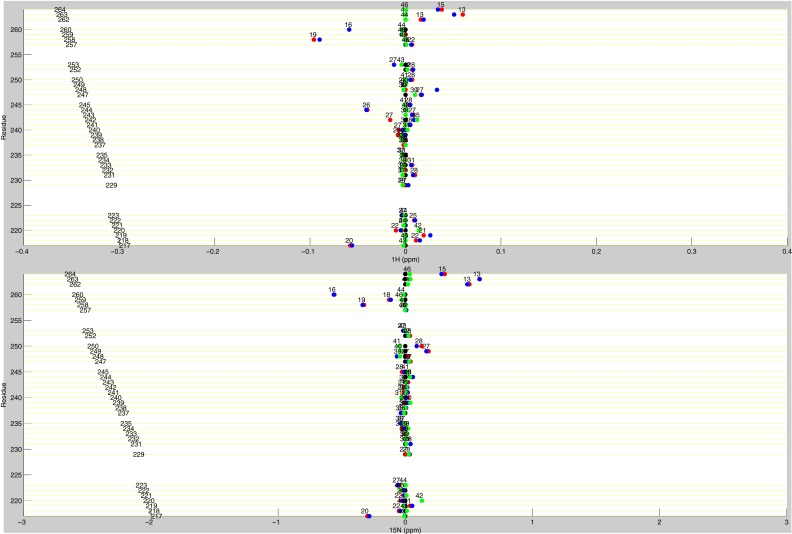

Fig. S1.

Overall CSPs upon binding the first and second dUMP. The complete effects of binding the first (A) and second (B) dUMP to dimeric TS are shown. Residues with significant CSPs are shown as spheres. Residues that are unassigned or missing are in yellow. In both A and B, the binding subunit CSPs are in purple, and the nonbinding subunit CSPs are in red. The binding dUMP is shown in dark blue. In B, the first bound dUMP is shown in light blue.

Although CSPs for the second dUMP binding event (dUMP1 to dUMP2) cannot be directly calculated, they can be obtained indirectly from the mixed dimers by reconstructing the WT dUMP1 chemical shifts, which was accomplished using a vector-based correction to account for the effects of the RREE mutation (Fig. 3 and SI Materials and Methods). This correction allows generation of WT dUMP1 chemical shifts from the mixed dimer dUMP1 chemical shifts (open circles in Figs. 3 and 4). The correction was cross-validated separately on a reference complex (Fig. S2 and SI Materials and Methods). In contrast to the first dUMP, the second dUMP had more pronounced effects throughout the entire protein. The effects of the second dUMP on the binding subunit resembled the effects of the first dUMP, with the largest and majority of the perturbations localized around the binding site (Fig. 2D). Most notably, however, unlike the first dUMP, the second dUMP caused significant perturbations to the other binding site: in this case, the site bound by the first dUMP (e.g., Q17 and V170) (Fig. 2C). The widespread perturbations in both subunits upon the second binding dUMP indicated subunit communication between the two binding sites. Overall, the CSP analysis showed an imbalance in the subunits' responses to the two dUMP binding events: CSPs were limited to the binding site for the first dUMP but covered the interface and both binding sites for the second dUMP.

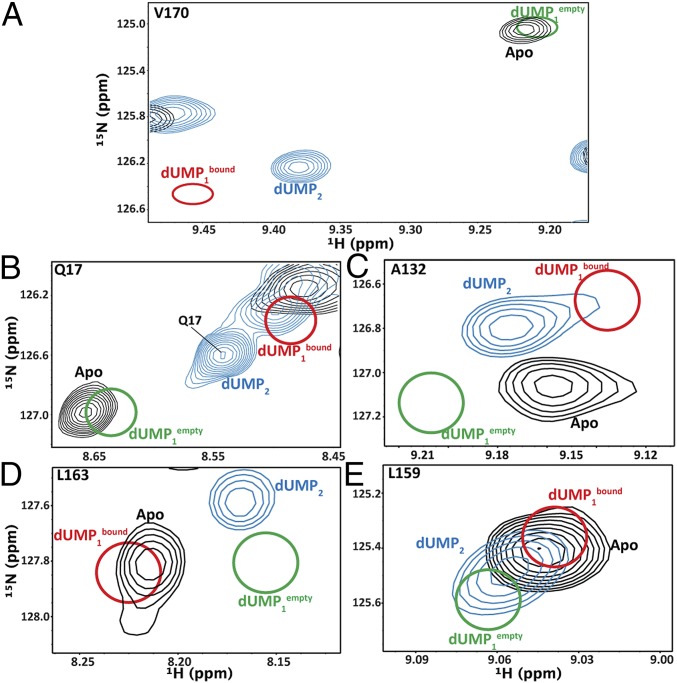

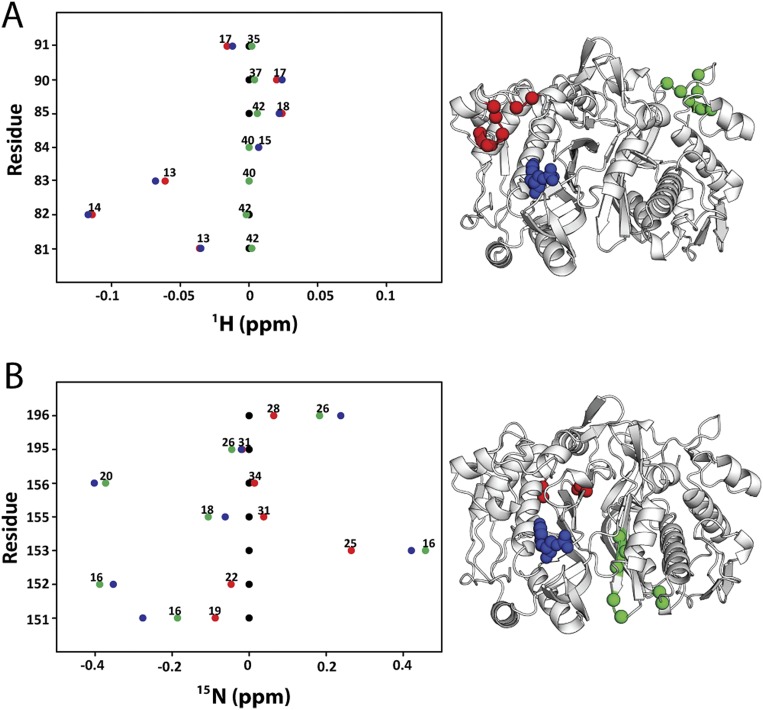

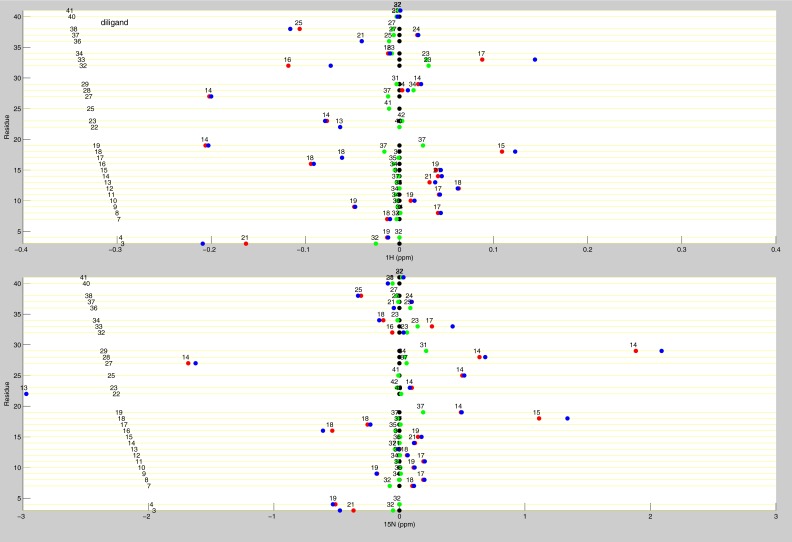

Fig. 4.

dUMP ligand state multiplets. Spectral overlays of apo, dUMP1, and dUMP2 allow visualization of chemical shift behaviors. WT apo and dUMP2 peaks are shown in black and blue, respectively. The WT dUMP1 peaks reconstructed from the mixed dimer chemical shifts are shown as red (bound subunit) and green (empty subunit) circles. These panels show the three classes of extreme chemical shift behaviors of the dUMP1 state. A and B highlight supershifting of dUMP1bound, C highlights orthogonal shifting, D highlights reverse shifting of dUMP1bound, and E highlights supershifting (dUMP1empty) coupled with reverse shifting (dUMP1bound).

Ligand State Multiplets Reveal That dUMP1 Is an Extreme State.

Although standard CSP analysis is effective at revealing overall perturbations of large magnitude, it can also obscure, especially in the case of a homodimer, interesting chemical shift behavior. To view the complete WT chemical shift responses, we sought to visualize relative peak positions of the dUMP0, dUMP1 (reconstructed), and dUMP2 states for each residue amide. In general, these overlays yielded four-peak ligand state multiplets (Fig. 4) because the dUMP0 and dUMP2 states yielded single peaks due to dimer symmetry, and the dUMP1 state can yield two distinct peaks, one from each of the mixed dimer samples. For clarity, we used superscripts “apo,” “empty,” “bound,” and “doub” to refer to peak positions of the dUMP0 state, the empty subunit of the dUMP1 state, the bound subunit of the dUMP1 state, and the dUMP2 state, respectively.

One interesting feature of the multiplets is that, in some cases, the peak positions of the dUMP1 state actually extended further than the dUMP2 peaks, which we refer to as “supershifting.” Supershifting can be seen for V170 and Q17 (Fig. 4 A and B), where V170bound (Q17bound) shifts in the same direction as V170doub (Q17doub), but actually shifts beyond V170doub (Q17doub). The simple case where supershifting is along the apo–doub chemical shift change vector suggests a fast equilibrium of free and bound states, and, oddly, binding the first dUMP pushes the equilibrium further than the second dUMP. Alternatively, it could suggest that protomers may not simply snap into a free or bound conformation, but rather that there are additional states that protomers can adopt and that binding the first dUMP induces a more extreme state. Much of the dUMP1 supershifting occurs around the binding site (Fig. S3 A and B), which, remarkably, explains the long-range intersubunit communication observed upon binding the second dUMP (Fig. 2C). Because the first dUMP seems to induce an extreme state beyond what is observed in the dUMP2 state, and one that cannot be supported with both subunits bound, a response is set up in which binding the second dUMP partially reverses the initial shift (e.g., V170 in Fig. 4A). This result leads to intersubunit communication upon binding the second dUMP by making corrections to supershifting caused by the first dUMP.

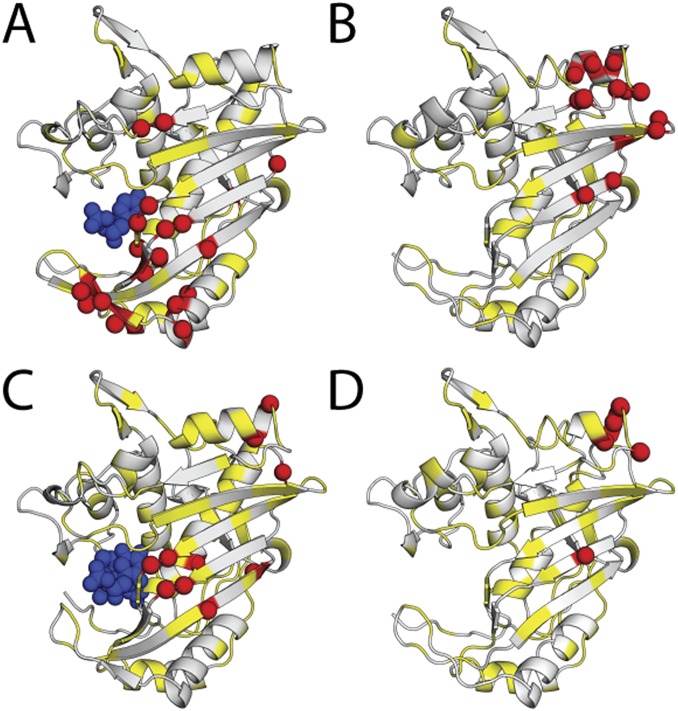

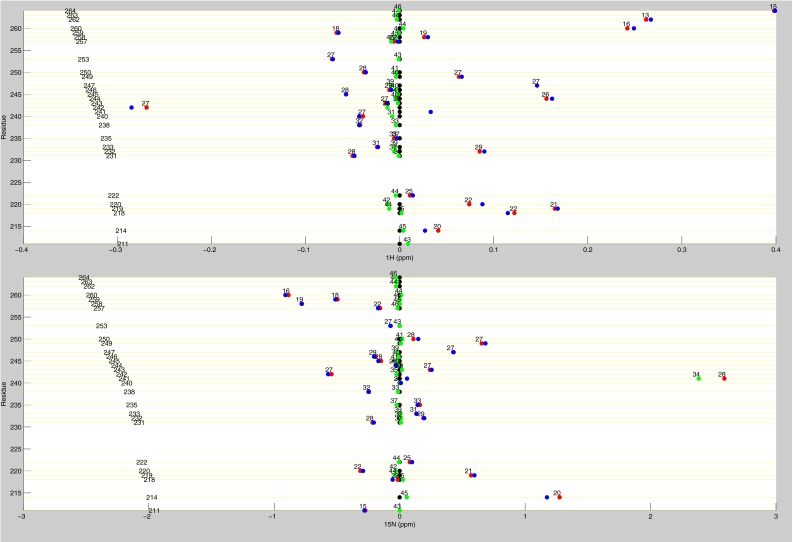

Fig. S3.

Supershifted residues in the dUMP1 and diligand1 states. Residues that exhibit supershifting upon binding the first dUMP (Top) or diligand (Bottom) are shown, using the same hinge rotation as in Fig. 2. Supershifted residues, shown as red spheres, have a CSP greater than 0.025 ppm with a supershift greater than 0.01 ppm. dUMP (A) and diligand (C) are shown in blue, and unassigned residues are shown in yellow. (A) Supershifted residues in the dUMP1bound subunit. (B) Supershifted residues in the dUMP1empty subunit. (C) Supershifted residues in the diligand1bound subunit. (D) Supershifted residues in the diligand1empty subunit.

More complex shifting behavior was seen in additional residues. For example, A132 exhibited not only supershifting, but also an A132empty and A132bound shift in a direction orthogonal to the A132apo–A132doub vector, termed “orthogonal shifting,” indicating that such sites are not simply in a fast, two-state equilibrium (Fig. 4C). This result, again, points to the existence of an additional state that becomes significantly populated upon binding the first dUMP. Another multiplet pattern we observed was “reverse shifting,” where dUMP1 peaks shift in the opposite direction of the apo–doub chemical shift vector (Fig. 4 D and E). It is not immediately clear why reverse shifting was observed although, along with supershifting, it suggests that there are compensatory behaviors occurring in the protomers upon binding the first dUMP. Overall, the observations of supershifting, orthogonal shifting, and reverse shifting suggest that a single dUMP binding induces sampling of extreme conformations relative to apo and dUMP2 states.

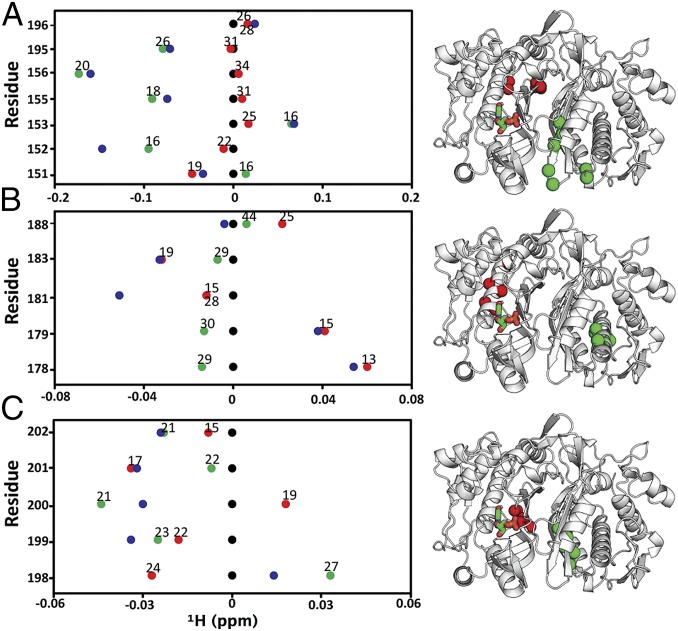

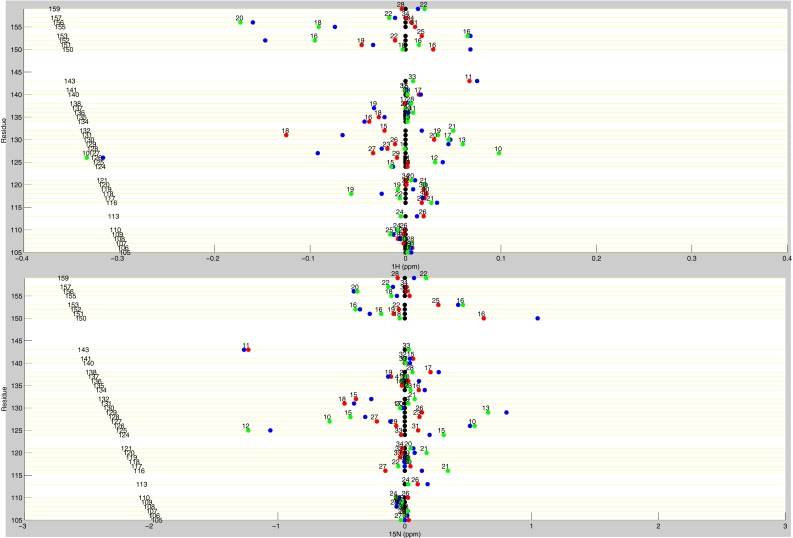

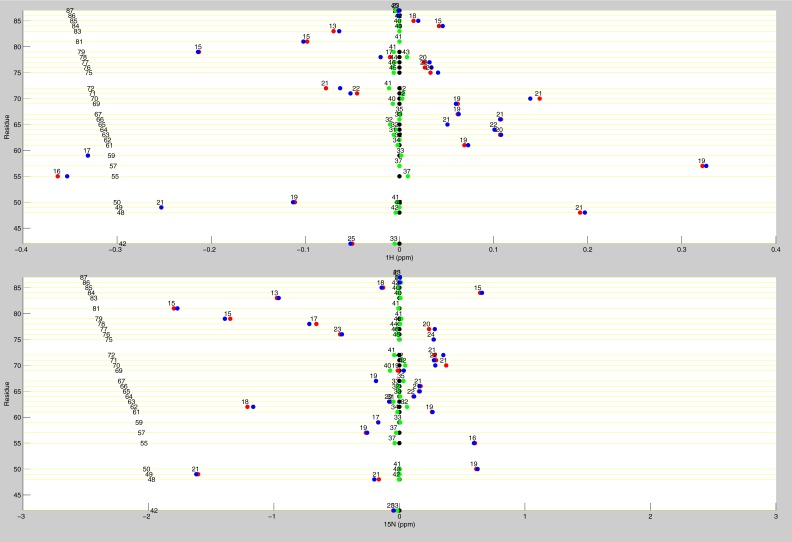

Using ligand state multiplets from spectral overlays to assess specific residue chemical shift behaviors is generally not practical because the four peaks from each residue render the spectra too crowded. Thus, to enhance the analysis of multiplet behavior, we condensed the information into “line plots” of 1H and 15N chemical shifts, which allowed for simpler viewing of chemical shifts to more conveniently inspect individual residues in terms of the spatial response to dUMP binding (Fig. 5 and Figs. S4 and S5). For simplicity, 1H line plots are shown although corresponding 15N line plots are also easily viewed (Fig. S4B). From the line plots, we identified clusters of residues with similar behaviors, indicating regions of ligand sensitivity throughout the protein. Residues 155, 156, and 195 (Fig. 5A) are spatially clustered and exhibit similar supershifting behavior, indicating an extreme state (or skewed population) in this region. In the case of E195, the two sites are nearly equidistant from dUMP, ∼28 Å, yet E195empty supershifts and E195bound hardly shifts, showing how communication can be more effective across the interface. Residues in the central helix, in particular I178 and A179 (Fig. 5B), show that ligand binding can be sensed at distal sites even with no direct contact to, or across, the interface. Additionally, these regions show a symmetric pattern in which supershifting in one subunit is linked with reverse shifting in the other. This pattern was observed frequently throughout TS, indicating extensive compensatory behavior between subunits. Residues along the interface (Fig. 5C) showed the largest variety, as well as the most symmetric, of behaviors. These residues in particular reflect the quasi-symmetrical, compensatory shifts that occur where a partial shift or supershift in one subunit is coupled with a partial or reverse shift in the other subunit: e.g., V199, and D198. In summary, using mixed labeled dimers coupled with viewing ligand state multiplets via line plots facilitates thorough inspection of shifting from binding of both dUMP molecules, and extensive supershifting and reverse shifting indicate significant population of extreme states (or a further shifting of the equilibrium) beyond the known apo and dUMP2 conformations.

Fig. 5.

Line plots of 1H chemical shifts. These line plots show how the chemical shift behaviors observed from ligand state multiplets are distributed throughout the protein. 1H chemical shift changes (relative to apo) are plotted for apo (black), dUMP2 (blue), dUMP1bound (red), and dUMP1empty (green). Each of the dUMP1 points is labeled with the distance (in Å) of that residue (red and green spheres) from the bound dUMP (sticks). Distances are measured from the amide N to the centroid of the bound dUMP. (A) Behaviors of residues at opposite ends of the dimer interface. (B) Behaviors of interior residues. (C) Behaviors of residues at the center of the dimer interface.

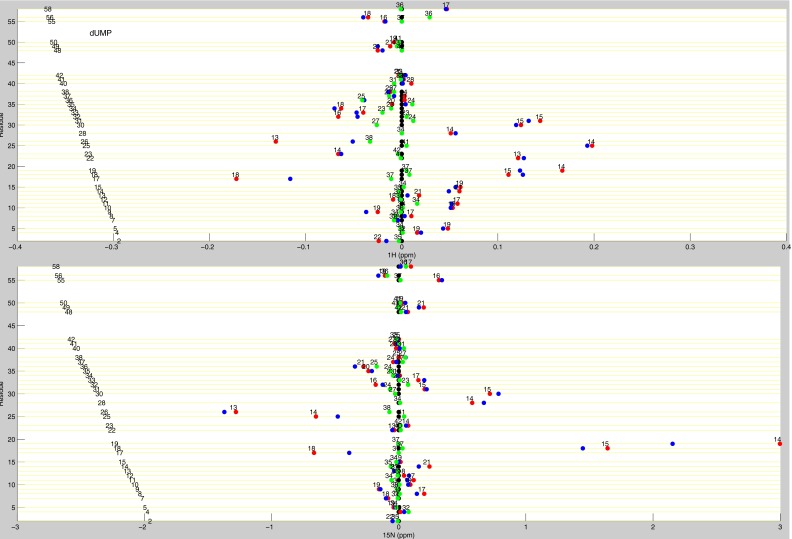

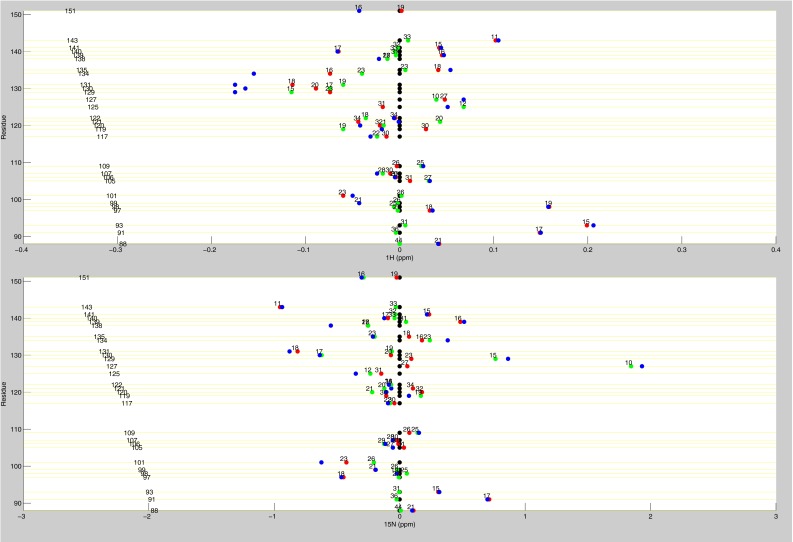

Fig. S4.

Line plots of 1H and 15N chemical shifts. 1H and 15N chemical shift differences are plotted for apo (black), dUMP2 (blue), dUMP1bound (red), and dUMP1empty (green). Each of the dUMP1 points is labeled with the distance of that residue (red and green spheres on the structure) from the bound dUMP (blue spheres on the structure). Distances are measured from the amide N to the centroid of the bound dUMP. (A) Residues that are distal from the interface (81–91) show expected behavior where proximal residues are perturbed by dUMP with no effect on the distal residues. The agreement of the dUMP1 peaks with the apo or dUMP2 peaks also shows that the observed extreme behaviors (Fig. 5) are intrinsic behaviors of the protein. (B) 15N chemical shifts for residues in Fig. 5A show that the observed behaviors are not nucleus-specific.

Fig. S5.

Line plots of dUMP 1H and 15N chemical shifts. These line plots show the chemical shift behavior for dUMP binding for all available residues of TS. 1H and 15N chemical shift differences are plotted for apo (black), dUMP2 (blue), dUMP1bound (red), and dUMP1empty (green). Each of the dUMP1 points are labeled with the distance (in Å) of that residue from the bound dUMP. Distances are measured from the amide N to the centroid of the bound dUMP.

Subunits' Response to Diligand Binding Is Equally Balanced.

Although the mixed dimers are required to visualize the dUMP1 states, they are not required for the cofactor binding step of the reaction. Binding of a substrate analog, 5-FdUMP, along with cofactor, together referred to as the “diligand,” forms a covalent bond to the enzyme, leading to a stable ternary complex (22, 23). Because of the covalent nature of this complex, the resonances from the diligand-bound TS are in slow exchange, and, thus, the chemical shifts of the diligand1 states can be more easily measured (SI Materials and Methods) (16). Together, dUMP and diligand will allow us to compare the proteins’ response, not only to an additional binding event but also to a conformational change, because, unlike dUMP binding, diligand binding causes significant conformational changes in the vicinity of the binding site to form the closed ternary complex (22, 24).

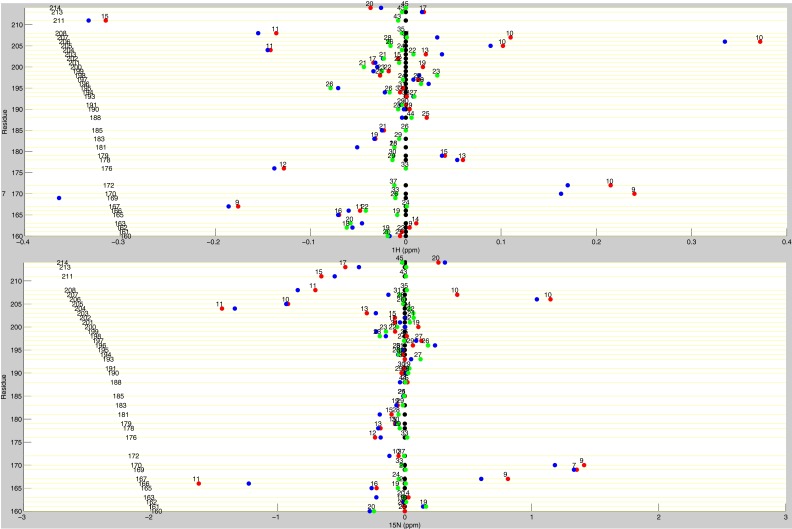

CSP analysis highlighted a number of interesting differences between dUMP and diligand binding (Fig. 2 and Fig. S6). Binding of the first diligand had overall larger magnitude and more extensive CSPs in both the binding and empty subunits than did dUMP, likely due to the combined effects of the conformational change and increased size of the diligand relative to dUMP (Fig. S6 A and B). Most notably, the effects of the first diligand propagated further in both subunits, ∼30 Å from diligand, extending almost all the way to the second binding site. Thus, unlike with dUMP binding, there was clearly communication between the two sites upon binding the first diligand. Additionally, similar to dUMP binding, the effects of the second diligand on the binding subunit resembled those of the first (Fig. S6D). Most strikingly, there were no significant perturbations to the other binding site, as with dUMP (Fig. S6C). Overall, the similarities in the CSPs for the two diligand binding events indicate a balanced response to diligand binding, in contrast to dUMP binding. This balanced response to diligand is also evident in the diligand line plots (Fig. S7). Not surprisingly, the diligand line plots show more symmetrical and fewer extreme features, with the vast majority of the diligand1 peaks either coinciding with, or being equally displaced from, the diligand0 and diligand2 peaks. Accordingly, there were very few diligand residues that showed supershifting (Fig. S3). However, as with dUMP, when supershifiting did occur, it was often coupled with reverse shifting, yielding symmetrical patterns.

Fig. S6.

Chemical shift perturbations upon binding the first and second diligand. The effects of binding the first diligand to the binding (A) and nonbinding (B) subunits of the dimer are shown at the Top. The effects of binding the second diligand to the nonbinding (C) and binding (D) subunits are shown at the Bottom. Viewing the dimer interface region is enhanced by separating the two subunits, where the subunits on the right underwent a hinge-type rotation (dotted line) to yield the same viewing angle as those on the left. Residues with significant CSPs are shown as spheres. Residues that are missing or unassigned are in yellow. The first bound (dilig 1) and second bound (dilig 2) diligands are shown in dark blue; for binding of dilig 2 (Bottom), the previously bound dilig 1 is shown in light blue.

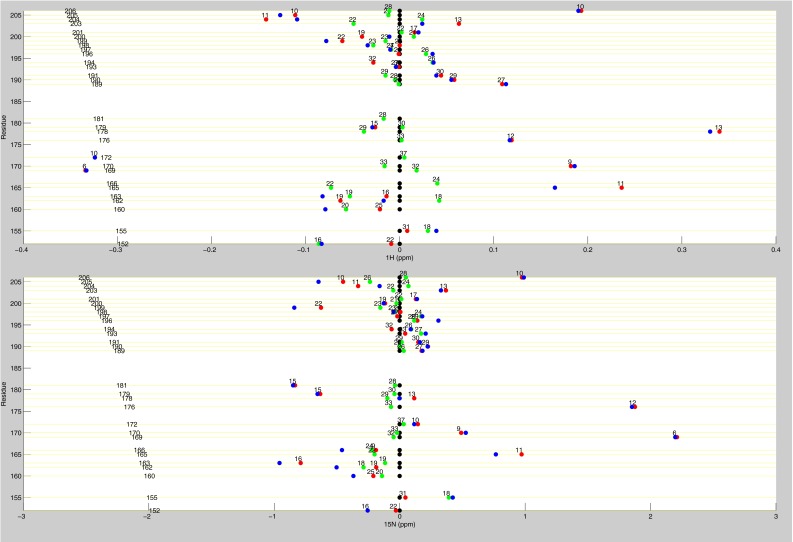

Fig. S7.

Line plots of diligand 1H and 15N chemical shifts. These line plots show the chemical shift behavior for diligand binding for all available residues of TS. 1H and 15N chemical shift differences are plotted for apo (black), diligand2 (blue), diligand1bound (red), and diligand1empty (green). Each of the diligand1 points are labeled with the distance (in Å) of that residue from the bound dUMP. Distances are measured from the amide N to the centroid of the bound dUMP.

Discussion

In this study, we used mixed labeled dimers to investigate, by NMR, intersubunit signaling in response to single ligand (dUMP or diligand) binding events in the homodimeric enzyme thymidylate synthase (TS). The mixed dimer approach allows for isolation of singly ligated (lig1) states and breaks the symmetry degeneracy in the NMR signals. This approach yields a rare example of step-wise progression of chemical shifts upon binding identical ligands in a homodimer and prompted the use of visualization strategies beyond simple CSPs. Standard CSP analysis revealed that only the binding of the second dUMP “signals” to the other binding site. This modulation of second ligand binding due to changes at the first site represents a nonintuitive yet valid potential allosteric mechanism. More generally, a distribution of ligand state peak multiplets were observed that point to regional behaviors, including the surprising observation of shifting of lig1 peaks beyond lig2 peaks, termed “supershifting” here. There was also a surprising degree of quasi-symmetrical responses in the two protomers, especially in the diligand complex, indicating substantial compensatory behavior coupled across the dimer interface. One caveat of the RREE mixed dimers used here is that, without binding of the second ligand, there can technically be no functional allostery. The primary goal, however, was to observe the mechanistic preparations that the homodimer makes before the second ligand binding event that enable the allosteric effect. Although the RREE mutation may have altered some of these preparations, the reconstructed binding steps yielded much useful information about allosteric communication. Although the focus of this study was on chemical shifts, clearly this strategy lends itself to protomer-specific NMR measurements, such as spin relaxation for the characterization of dynamics, on specific ligation states. Lastly, although the strategy used here applies primarily to tight dimers that do not readily dissociate, it can potentially be applied to other systems by covalently linking the monomers.

Insights into Allostery from Ligand State Peak Multiplets.

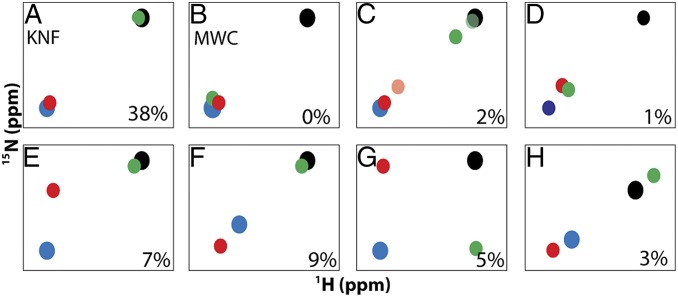

The mixed labeled dimers allow for simple viewing of complete ligand state NMR peak multiplets, which, to our knowledge, have not been previously reported. The patterns observed in the multiplets can provide a format for evaluating allosteric models. For example, the most easily observed patterns are the doublets that would arise from a Koshland–Némethy–Filmer (KNF) or Monod–Wyman–Changeux (MWC) type system, and their expected intensities (12, 25), with only two possible states (Fig. 6 A and B). In the KNF system, where only the binding subunit responds to ligand, the lig1bound and lig1empty peaks would coincide with the lig2 and lig0 peaks, respectively. In the MWC system, ligand binding causes a concerted shift in both subunits, where both lig1 peaks would coincide with the lig2 peak. Alternatively, one might expect to observe two possible linear triplet patterns, one where one of the lig1 peaks coincides with either the lig2 or lig0 peaks and the other is partially shifted toward lig2, or one where both lig1 peaks are partially shifted toward lig2 (Fig. 6 C and D) (12). We observed such triplet patterns in our dUMP data as did others previously in studies of half-titrated, negatively cooperative dimers that are in the slow exchange regime (12, 26). Interestingly, we also observed many nonlinear triplets, and quartets (Fig. 6 E and G), that indicate behaviors beyond simple population or exchange between lig0 and lig2 states. It is currently not clear precisely what structural changes produce these nonlinear multiplets although it must involve at least a third conformation distinct from the lig0 and lig2 conformations. Given this diverse set of multiplet patterns, it seems that there is not a consistent response throughout the protein, but, rather, TS has a mixture of intersubunit responses to binding of dUMP. Evaluation of the ligand state multiplets makes this response clear, and it is possible to do so outside of the slow exchange condition. In general, the evaluation of NMR ligand state multiplets in oligomeric proteins is a powerful approach to characterize allosteric mechanisms in proteins (12, 25).

Fig. 6.

Observable patterns for ligand state multiplets. Schematic HSQC peak patterns according to allosteric model (A and B) or observed for dUMP binding in TS as resolved triplets (C–F) or quartets (G and H). Peaks are shown for apo/lig0 (black), lig1bound (red), lig1empty (green), and lig2 (blue). In C, two partial shifting behaviors are shown in which lig1 partial peak shifting is observed in the binding subunit (light red) or in the empty subunit (dark green). Behaviors are observed for supershifting (F), orthogonal shifting (G), and reverse shifting (H). In each panel, the percentages indicate the abundance of the peak pattern for dUMP binding to TS.

Perhaps the most surprising multiplet pattern evident was the observation of supershifting (and reverse shifting) in the lig1 state, which was unexpected under the assumption that lig0 and lig2 peak positions represent end states. However, as is apparent here and from previous studies (27, 28), this assumption is not always a good one because peak positions of specific mutants point to a shift in the equilibrium beyond the assumed end points of apo and ligand bound, which suggests that, for those sites, the apo and ligand saturated states (29) both represent dynamic equilibria between two extreme states that are not readily detected. It is interesting that, although supershifting and reverse shifting have been observed from comparisons of mutant and WT peak positions, here they are observed from lig1 peak positions. It is also interesting that these behaviors are highly dependent on the residue (Fig. S3). Although changes in two-state equilibria can explain NMR peaks moving in a linear fashion, they cannot explain orthogonal peak movement. Therefore, a general explanation for the various behaviors observed here is that the lig1 state peak positions may reflect a range of different local conformations that TS samples upon binding the first ligand. These conformations may represent different sets of interactions (hydrogen bond geometries, for example) that lead to particular lig1 chemical shifts. Thus, TS may reside in a relatively shallow conformational basin on the energy landscape that allows it to modulate various interactions by conformational adjustment, yielding different chemical shifts, upon binding one or two ligands. This scenario provides a more flexible model for interpreting chemical shifts and is fundamentally distinct from two-state switching.

Lig1 Asymmetry from X-Ray and NMR Chemical Shifts.

Although the functional significance of these multiplet behaviors remains to be determined, there is a precedent for the asymmetric effects of dUMP binding to TS. A crystal structure of Pneumocystis carinii TS bound to dUMP and a cofactor analog, CB3717, has an asymmetric ternary complex wherein one active site has both dUMP and cofactor bound whereas the other has only dUMP bound (17). A key observation from this structure is that, in addition to the global changes that occur upon cofactor binding, there are subtle, yet significant conformational differences between the two monomers for a number of residues along the otherwise rigid dimer interface. It was proposed that these residues are the primary candidates for signaling between the active sites and could provide the basis for cooperativity. Of these residues, 75% exhibited nonlinear or supershifted triplets and quartets here for dUMP binding. The fact that we see such extensive overlap could suggest that these subtle structural rearrangements are also occurring in the dUMP1 state. The nonlinear shifts observed for these residues point to an additional state outside the apo-bound equilibrium, rather than simply an equilibrium shift. This extreme state could be due to strain induced by binding the first dUMP, leading to an asymmetric lig1 state. This strained conformational state may be the result of differential perturbations to the hydrogen-bonding network across the interface or to differences in dynamics between the two subunits in the lig1 state. The fact that we see nonlinear behavior for these residues suggests that, if in fact these residues form a communication pathway, this extreme state may be one that is involved in TS cooperativity.

Given the long-range, intersubunit impact of binding the second dUMP, it is surprising that dUMP binding is thermodynamically noncooperative at 25 °C, at which the NMR chemical shifts were investigated. However, at lower temperatures, the ΔH°bind values for the first and second dUMP molecules are nonequivalent, reflecting intrinsically different ΔCp° values for the two binding events. Thus, the underlying thermodynamics can be considered nonidentical for the two binding events, which could be reflected in the observed chemical shift behaviors. Furthermore, although dUMP binding does not trigger functional intersubunit allostery, it may still reveal the intrinsic communication mechanisms that could potentially lead to functional allostery during subsequent reaction steps. Overall, the presence of communication upon dUMP binding could indicate that TS is poised for intersubunit allostery.

Potential Origin of Symmetrical Chemical Shift Response.

Based on the observations made here, we propose that binding of the first dUMP or diligand to the structurally symmetric dimer imparts compensatory effects between the two protomers. In the case of dUMP binding, presuming there is no significant conformational change, the symmetrical chemical shift changes arise from either propagation of changes in hydrogen bonding strengths in a symmetrical fashion, or from compensatory dynamical responses between the two protomers, or a combination of both. In the case of diligand binding, given that there is likely a conformational change in the bound subunit (22, 24), the symmetrical chemical shift changes are even more surprising because the shift in the bound subunit from the structural change cannot be replicated in the empty subunit. In either case, the propagation of chemical shift changes likely represents a form of structural or dynamic strain that, remarkably, has opposite manifestations in the two protomers for many residues. These considerations of quasi-symmetrical multiplets provide a unique view into how intersubunit allostery can be achieved for the simple example of symmetric homodimers. It seems that, at least for TS, symmetric cross-dimer interactions are “built in,” such that quasi-symmetrical strain is introduced by the binding of the first ligand. The magnitude of symmetric chemical shift multiplet patterns and their extent throughout the protein indicate that TS is incredibly sensitive to substrate binding at sites throughout its structure, but particularly at the dimer interface. A fundamental question for understanding allostery is whether the intrinsic compensatory effects observed here will be observed in other homodimeric proteins, especially those that are allosteric with regard to binding two ligands.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM083059 (to A.L.L.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See Commentary on page 9407.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1604748113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Cui Q, Karplus M. Allostery and cooperativity revisited. Protein Sci. 2008;17(8):1295–1307. doi: 10.1110/ps.03259908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lisi GP, Loria JP. Solution NMR spectroscopy for the study of enzyme allostery. Chem Rev. 2016;116(11):6323–6369. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nussinov R, Tsai CJ. Allostery without a conformational change? Revisiting the paradigm. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2015;30:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsai CJ, Del Sol A, Nussinov R. Protein allostery, signal transmission and dynamics: A classification scheme of allosteric mechanisms. Mol Biosyst. 2009;5(3):207–216. doi: 10.1039/b819720b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klemm JD, Schreiber SL, Crabtree GR. Dimerization as a regulatory mechanism in signal transduction. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:569–592. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lipchock JM, Loria JP. Nanometer propagation of millisecond motions in V-type allostery. Structure. 2010;18(12):1596–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhuravleva A, Clerico EM, Gierasch LM. An interdomain energetic tug-of-war creates the allosterically active state in Hsp70 molecular chaperones. Cell. 2012;151(6):1296–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akimoto M, et al. Mapping the free energy landscape of PKA inhibition and activation: A double-conformational selection model for the tandem cAMP-binding domains of PKA RIα. PLoS Biol. 2015;13(11):e1002305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williamson MP. Using chemical shift perturbation to characterise ligand binding. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2013;73:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selvaratnam R, Chowdhury S, VanSchouwen B, Melacini G. Mapping allostery through the covariance analysis of NMR chemical shifts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(15):6133–6138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017311108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Popovych N, Sun S, Ebright RH, Kalodimos CG. Dynamically driven protein allostery. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13(9):831–838. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stevens SY, Sanker S, Kent C, Zuiderweg ER. Delineation of the allosteric mechanism of a cytidylyltransferase exhibiting negative cooperativity. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8(11):947–952. doi: 10.1038/nsb1101-947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson EF, Hinz W, Atreya CE, Maley F, Anderson KS. Mechanistic characterization of Toxoplasma gondii thymidylate synthase (TS-DHFR)-dihydrofolate reductase: Evidence for a TS intermediate and TS half-sites reactivity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(45):43126–43136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206523200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maley F, Pedersen-Lane J, Changchien L. Complete restoration of activity to inactive mutants of Escherichia coli thymidylate synthase: Evidence that E. coli thymidylate synthase is a half-the-sites activity enzyme. Biochemistry. 1995;34(5):1469–1474. doi: 10.1021/bi00005a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saxl RL, Changchien LM, Hardy LW, Maley F. Parameters affecting the restoration of activity to inactive mutants of thymidylate synthase via subunit exchange: Further evidence that thymidylate synthase is a half-of-the-sites activity enzyme. Biochemistry. 2001;40(17):5275–5282. doi: 10.1021/bi002925x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sapienza PJ, Falk BT, Lee AL. Bacterial thymidylate synthase binds two molecules of substrate and cofactor without cooperativity. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137(45):14260–14263. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b10128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson AC, O’Neil RH, DeLano WL, Stroud RM. The structural mechanism for half-the-sites reactivity in an enzyme, thymidylate synthase, involves a relay of changes between subunits. Biochemistry. 1999;38(42):13829–13836. doi: 10.1021/bi991610i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dev IK, et al. Mode of binding of folate analogs to thymidylate synthase: Evidence for two asymmetric but interactive substrate binding sites. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(3):1873–1882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lovelace LL, Gibson LM, Lebioda L. Cooperative inhibition of human thymidylate synthase by mixtures of active site binding and allosteric inhibitors. Biochemistry. 2007;46(10):2823–2830. doi: 10.1021/bi061309j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reilly RT, Barbour KW, Dunlap RB, Berger FG. Biphasic binding of 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridylate to human thymidylate synthase. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;48(1):72–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swiniarska M, et al. Segmental motions of rat thymidylate synthase leading to half-the-sites behavior. Biopolymers. 2010;93(6):549–559. doi: 10.1002/bip.21393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hyatt DC, Maley F, Montfort WR. Use of strain in a stereospecific catalytic mechanism: Crystal structures of Escherichia coli thymidylate synthase bound to FdUMP and methylenetetrahydrofolate. Biochemistry. 1997;36(15):4585–4594. doi: 10.1021/bi962936j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santi DV, McHenry CS, Perriard ER. A filter assay for thymidylate synthetase using 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridylate as an active site titrant. Biochemistry. 1974;13(3):467–470. doi: 10.1021/bi00700a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stroud RM, Finer-Moore JS. Conformational dynamics along an enzymatic reaction pathway: Thymidylate synthase, “the movie”. Biochemistry. 2003;42(2):239–247. doi: 10.1021/bi020598i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freiburger LA, et al. Competing allosteric mechanisms modulate substrate binding in a dimeric enzyme. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18(3):288–294. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tzeng SR, Kalodimos CG. Dynamic activation of an allosteric regulatory protein. Nature. 2009;462(7271):368–372. doi: 10.1038/nature08560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gardino AK, et al. Transient non-native hydrogen bonds promote activation of a signaling protein. Cell. 2009;139(6):1109–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonald LR, Boyer JA, Lee AL. Segmental motions, not a two-state concerted switch, underlie allostery in CheY. Structure. 2012;20(8):1363–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beach H, Cole R, Gill ML, Loria JP. Conservation of mus-ms enzyme motions in the apo- and substrate-mimicked state. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(25):9167–9176. doi: 10.1021/ja0514949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Changchien LM, et al. High-level expression of Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis thymidylate synthases. Protein Expr Purif. 2000;19(2):265–270. doi: 10.1006/prep.2000.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agrawal N, Hong B, Mihai C, Kohen A. Vibrationally enhanced hydrogen tunneling in the Escherichia coli thymidylate synthase catalyzed reaction. Biochemistry. 2004;43(7):1998–2006. doi: 10.1021/bi036124g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hardy LW, Pacitti DF, Nalivaika E. Use of a purified heterodimer to test negative cooperativity as the basis of substrate inactivation of Escherichia coli thymidylate synthase (Asn177-->Asp) Structure. 1994;2(9):833–838. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(94)00084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang X, Frey DD. High-performance cation-exchange chromatofocusing of proteins. J Chromatogr A. 2003;991(1):117–128. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(03)00210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidt M, Hafner M, Frech C. Modeling of salt and pH gradient elution in ion-exchange chromatography. J Sep Sci. 2014;37(1-2):5–13. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201301007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sapienza PJ, Lee AL. Backbone and ILV methyl resonance assignments of E. coli thymidylate synthase bound to cofactor and a nucleotide analogue. Biomol NMR Assign. 2014;8(1):195–199. doi: 10.1007/s12104-013-9482-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]