Significance

Understanding how climate change affects ecosystem productivity is critical for managing fisheries and sustaining biodiversity. African lakes are warming rapidly, potentially jeopardizing both their high endemic biodiversity and important fisheries. Using paleoecological records from Lake Tanganyika, we show that declines in commercially important fishes and endemic molluscs have accompanied lake warming. Ongoing declines in fishery species began well before the advent of commercial fishing in the mid-20th century. Warming has intensified the stratification of the water column, thereby trapping nutrients in deep water where they cannot fuel primary production and food webs. Simultaneously, warming has enlarged the low-oxygen zone, considerably narrowing the coastal habitat where most of Tanganyika’s endemic species are found.

Keywords: climate change, Lake Tanganyika, freshwater biodiversity, fisheries, paleoecology

Abstract

Warming climates are rapidly transforming lake ecosystems worldwide, but the breadth of changes in tropical lakes is poorly documented. Sustainable management of freshwater fisheries and biodiversity requires accounting for historical and ongoing stressors such as climate change and harvest intensity. This is problematic in tropical Africa, where records of ecosystem change are limited and local populations rely heavily on lakes for nutrition. Here, using a ∼1,500-y paleoecological record, we show that declines in fishery species and endemic molluscs began well before commercial fishing in Lake Tanganyika, Africa’s deepest and oldest lake. Paleoclimate and instrumental records demonstrate sustained warming in this lake during the last ∼150 y, which affects biota by strengthening and shallowing stratification of the water column. Reductions in lake mixing have depressed algal production and shrunk the oxygenated benthic habitat by 38% in our study areas, yielding fish and mollusc declines. Late-20th century fish fossil abundances at two of three sites were lower than at any other time in the last millennium and fell in concert with reduced diatom abundance and warming water. A negative correlation between lake temperature and fish and mollusc fossils over the last ∼500 y indicates that climate warming and intensifying stratification have almost certainly reduced potential fishery production, helping to explain ongoing declines in fish catches. Long-term declines of both benthic and pelagic species underscore the urgency of strategic efforts to sustain Lake Tanganyika’s extraordinary biodiversity and ecosystem services.

Warming climates are rapidly transforming lake ecosystems worldwide (1), but the breadth of changes in tropical lakes is poorly documented. In the Great Lakes of tropical Africa, inconsistent monitoring of temperature and ecosystem dynamics has limited our understanding of how warming has affected their extraordinary biodiversity and critical fisheries (2, 3). Such changes in Lake Tanganyika, Africa’s oldest and deepest (1,470 m) lake, are particularly problematic. This deep, stratified lake harbors spectacular freshwater biodiversity and endemism (2, 4, 5). It also yields up to 200,000 t of fish annually, comprising ∼60% of regional animal protein consumed (3, 6). The productive surface waters are fertilized by upwelling of nutrient-rich deep water during the windy season (7), providing the biogeochemical basis for the fishery. However, this ecosystem has changed dramatically in recent decades; expanding deforestation (8), intensifying fishing efforts (9), rising water temperatures, and declining phytoplankton production (10–12) have all been concurrent with fishery declines. As a result, debate continues over the relative roles of fishing practices and climate change in Tanganyika’s fishery declines (9–11).

Developing sustainable management strategies for this enormous fishery requires determining the impact of climate change on catch potential. Documentation of fishery yields and environmental conditions is sparse before the mid-20th century, making it difficult to infer the key drivers of ecosystem change. An alternative source of historical data on ecosystem dynamics can be derived from sediment cores from the lake bottom. Merging paleoclimatic and paleoecological perspectives has enabled estimation of fish population sizes and community dynamics before and after the onset of major fisheries elsewhere (13, 14), filling the information void before active monitoring.

In Lake Tanganyika, close coupling of physics, chemistry, and biology gives rise to a predictable cascade of warming effects: intensified stratification of the water column suppresses vertical mixing, leading to reduced nutrient delivery to the surface, which reduces algal production (10–12). Thus, rising temperatures could reduce fish populations by undercutting energy flow to the pelagic food web, by reducing their habitat as the low-oxygen zone rises, or by directly affecting fish physiology (15). With paleoecological data, this warming hypothesis can be tested by comparing fluctuations in fish fossil abundance to shifts in water temperature and algal production before intensive fishing. If the timing of fish declines instead matches the emergence of modern fisheries, then fishing practices rather than climate warming could be inferred to be an important driver of declining catches.

To test these predictions, we analyzed sediment cores from two nearshore sites (NP05-TB40 and LT98-07M) and one deep-water site (MC1/KH1) (Figs. 1–3, Tables S1–S6, and Fig. S1). In each case, we quantified geochemical proxies for temperature and algal production as well as the abundance of fossils from pelagic fishes and benthic invertebrates (ostracodes and molluscs). Benthic animals are of special concern because stronger stratification reduces oxygenated habitat in Lake Tanganyika (16, 17). In modern sediments, benthic invertebrates are generally absent from sediments deposited under anoxic conditions, although some ostracodes tolerate low oxygen (as low as 1 mg⋅L−1) relative to molluscs (generally >4 mg⋅L−1) (17–20). We quantified trends, correlations, break points in temporal patterns, and cross-factor correlations for temperature, algal production, and fossils to understand the respective roles of lake warming and fishing pressure in the recent history of the remarkable biota of Lake Tanganyika.

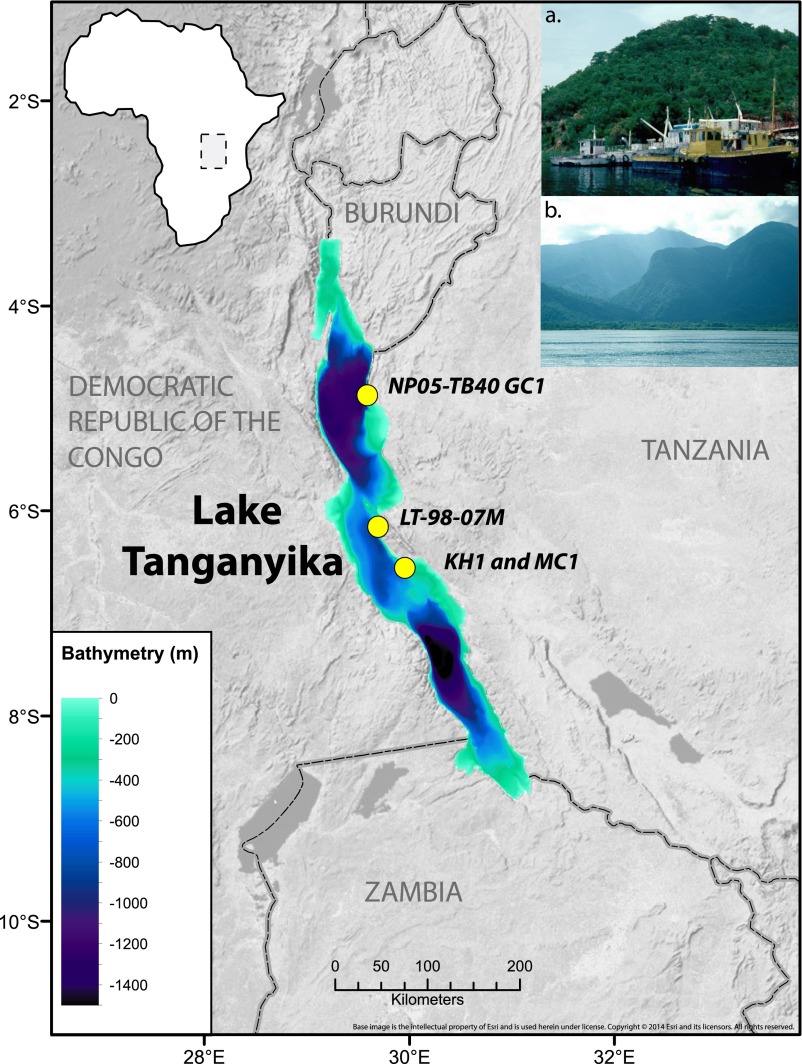

Fig. 1.

Lake Tanganyika and coring locations. (Inset A) Commercial (purse seine) fishing boats on Lake Tanganyika at Mpulungu, Zambia; (B) Rift mountains flanking L. Tanganyika at Mahale Mountains National Park near core site LT98-07. Steep mountain slopes are indicative of underwater slopes. Base map source: US National Park Service.

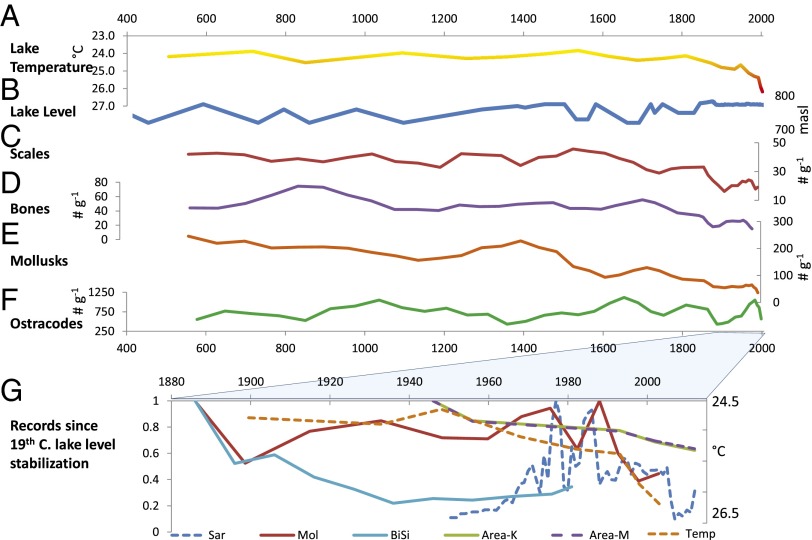

Fig. 3.

Paleoecological records from core NP05-TB40 from A.D. 400 to 2000. (A) Lake temperature for NP05-TB40 (cool calibration; note inverted scale) (29). (B) Lake level history (8, 22). Preinstrumental (1870) measurements are ±5m SD. (C) Fish scale abundance (3-point running average) number of scales per gram dry weight of sediment. (D) Fish bone abundance (3-point running average) number of bones per gram dry weight of sediment. (E) Mollusc fossil abundance (3-point running average, number of shell fragments per gram dry weight of sediment). (F) Ostracode fossil abundance (3-point running average, number of valves per gram dry weight of sediment). (G) Instrumental and fossil data since late-19th century lake level stabilization. All values normalized to 1 = maximum. Area K, proportion of lake floor oxygenated >4 mg O⋅L−1 in the Kigoma area lake margin relative to 1946; Area M, same for north Mahale coast; BiSi, MC1 BiSi; Mol, NP05-TB40 fossil molluscs; Sar, annual Tanzanian sardine catch (www.fao.org/fishery/statistics/en); Temp-NP05-TB40 TEX temperature.

Table S1.

Sediment core characteristics

| Core name | Date collected | Latitude | Longitude | Water depth, m | Core length/core type | Adjacent human impacts near core site at time of collection |

| LT98-07 | 7 January 1998 | 6°9.058′ | 29°42.479′ | 151 | 53 cm/Hedrick Marrs Multicore | Minimal (south of and adjacent to Mahale National Park) |

| NP04-KH1/MC1 | 18 July 2004 | 6°33.147′ | 29°58.480′ | 303 | KH1-534 cm/ Kullenberg Piston Core | Minimal at time of collection (North end of Mahale National Park near Lubulungu R. delta). Significantly increased since (ref. 32) |

| MC1-49 cm/Hedrick Marrs Multicore | ||||||

| NP05-TB40-GC1 | 29 July 2005 | 4°52.563′ | 29°36.183′ | 76 | 43 cm/MUCK-Gravity Core | Significant (in Kigoma Bay, high human population density and fishing nearby) |

Table S6.

Fossil count data: MC1/KH1

| Core depth | Fish fossil flux, no.⋅cm−2⋅y−1 | Year A.D. |

| 0.25 | 0.07 | 1996 |

| 0.75 | 0.04 | 1986 |

| 1.25 | 0.04 | 1976 |

| 1.75 | 0.04 | 1966 |

| 2.25 | 0.00 | 1956 |

| 2.75 | 0.00 | 1946 |

| 3.25 | 0.05 | 1936 |

| 3.75 | 0.09 | 1926 |

| 4.25 | 0.05 | 1916 |

| 4.75 | 0.00 | 1906 |

| 5.25 | 0.38 | 1896 |

| 5.75 | 0.27 | 1886 |

| 6.25 | 0.21 | 1876 |

| 6.75 | 0.36 | 1866 |

| 7.25 | 0.17 | 1856 |

| 7.50 | 0.37 | 1851 |

| 8.00 | 0.25 | 1841 |

| 8.50 | 0.09 | 1831 |

| 9.00 | 0.00 | 1821 |

| 9.50 | 0.05 | 1811 |

| 10.00 | 0.17 | 1801 |

| 10.50 | 0.43 | 1791 |

| 11.00 | 0.04 | 1781 |

| 11.50 | 0.27 | 1771 |

| 12.00 | 0.22 | 1761 |

| 12.50 | 0.09 | 1751 |

| 13.00 | 0.71 | 1741 |

| 13.50 | 1.00 | 1731 |

| 14.00 | 0.11 | 1721 |

| 14.50 | 0.00 | 1711 |

| 15.00 | 0.07 | 1701 |

| 15.50 | 0.11 | 1691 |

| 16.00 | 0.00 | 1681 |

| 16.50 | 0.00 | 1671 |

| 17.00 | 0.17 | 1661 |

| 17.50 | 1.33 | 1651 |

| 18.00 | 0.49 | 1641 |

| 18.50 | 1.58 | 1631 |

| 19.00 | 0.18 | 1621 |

| 19.50 | 0.08 | 1611 |

| 20.00 | 0.15 | 1601 |

| 20.50 | 0.03 | 1591 |

For details, please refer to the legend of Table S4.

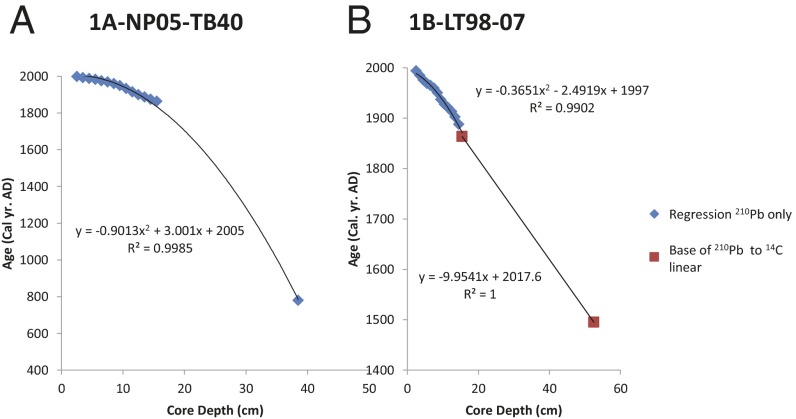

Fig. S1.

Age models and sample age assignments. For cores KH1/MC1, we used the age model previously published in ref. 12 for assignment of sample ages. (A) For core NP05-40, we combined the 210Pb and basal 14C age picks to generate a single polynomial regression for sample age assignments. (B) For LT98-07, a single polynomial combining both 210Pb and 14C data yielded a strong deviation from the nominal 210Pb age model alone (Table S2). Therefore, we used a polynomial regression for age assignments of the samples that fell in the 210Pb age range and linearly interpolated ages from the base of the 210Pb interval through the 14C date near the base of the core.

Table S4.

Fossil count data: Core LT98-07

| CD | B | S | B+S | BG | SG | TG | O | OG | M | MG | Year A.D. |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6.05 | 0 | 0 | 1994 |

| 2 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 1.08 | 0 | 1.08 | 11 | 1.32 | 0 | 0 | 1991 |

| 3 | 8 | 4 | 12 | 1.43 | 0.72 | 2.15 | 39 | 6.99 | 2 | 0.36 | 1986 |

| 4 | 35 | 3 | 38 | 5.67 | 0.49 | 6.16 | 71 | 11.50 | 0 | 0 | 1981 |

| 5 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0.26 | 0.13 | 0.38 | 97 | 12.37 | 0 | 0 | 1975 |

| 6 | 6 | 5 | 11 | 1.07 | 0.89 | 1.97 | 89 | 15.93 | 0 | 0 | 1969 |

| 7 | 13 | 6 | 19 | 2.17 | 1.00 | 3.16 | 161 | 26.79 | 24 | 3.99 | 1962 |

| 8 | 62 | 3 | 65 | 8.73 | 0.42 | 9.15 | 57 | 8.03 | 0 | 0 | 1954 |

| 9 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0.84 | 0 | 0.84 | 75 | 10.53 | 0 | 0 | 1945 |

| 10 | 10 | 5 | 15 | 1.46 | 0.73 | 2.18 | 69 | 10.04 | 0 | 0 | 1936 |

| 11 | 9 | 3 | 12 | 1.60 | 0.53 | 2.13 | 70 | 12.45 | 0 | 0 | 1925 |

| 12 | 3 | 10 | 13 | 0.58 | 1.92 | 2.50 | 60 | 11.52 | 0 | 0 | 1915 |

| 13 | 19 | 5 | 24 | 2.58 | 0.68 | 3.26 | 119 | 16.16 | 0 | 0 | 1903 |

| 14 | 16 | 3 | 19 | 2.30 | 0.43 | 2.73 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1891 |

| 15 | 20 | 7 | 27 | 3.63 | 1.27 | 4.91 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1877 |

| 16 | 11 | 12 | 23 | 1.91 | 2.08 | 3.99 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1858 |

| 17 | 10 | 2 | 12 | 1.78 | 0.36 | 2.14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1848 |

| 18 | 61 | 15 | 76 | 9.37 | 2.30 | 11.67 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1838 |

| 19 | 56 | 9 | 65 | 8.84 | 1.42 | 10.26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1828 |

| 20 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 0.64 | 0.13 | 0.77 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1819 |

| 21 | 3 | 9 | 12 | 0.36 | 1.08 | 1.44 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1809 |

| 22 | 13 | 28 | 41 | 1.51 | 3.25 | 4.76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1799 |

| 23 | 35 | 8 | 43 | 5.63 | 1.29 | 6.91 | 1 | 11.40 | 0 | 0 | 1789 |

| 24 | 30 | 3 | 33 | 5.63 | 0.56 | 6.20 | 3 | 26.29 | 0 | 0 | 1779 |

| 25 | 58 | 34 | 92 | 9.53 | 5.59 | 15.11 | 9 | 86.2 | 0 | 0 | 1769 |

| 26 | 27 | 10 | 37 | 3.99 | 1.48 | 5.47 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1759 |

| 27 | 29 | 16 | 45 | 4.49 | 2.48 | 6.97 | 7 | 79.19 | 0 | 0 | 1749 |

| 28 | 32 | 31 | 63 | 4.71 | 4.56 | 9.27 | 3 | 35.93 | 0 | 0 | 1739 |

| 29 | 82 | 14 | 96 | 12.19 | 2.08 | 14.28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1729 |

| 30 | 54 | 8 | 62 | 7.17 | 1.06 | 8.23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1719 |

| 31 | 15 | 5 | 20 | 1.94 | 0.65 | 2.58 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1709 |

| 32 | 15 | 15 | 30 | 2.68 | 2.68 | 5.36 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1699 |

| 33 | 27 | 5 | 32 | 3.46 | 0.64 | 4.10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1689 |

| 34 | 13 | 15 | 28 | 1.84 | 2.12 | 3.95 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1679 |

| 35 | 24 | 10 | 34 | 3.64 | 1.52 | 5.17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1669 |

| 36 | 43 | 16 | 59 | 5.53 | 2.06 | 7.58 | 2 | 0.26 | 0 | 0 | 1659 |

| 37 | 25 | 10 | 35 | 3.46 | 1.38 | 4.84 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1649 |

| 39 | 108 | 6 | 114 | 17.68 | 0.98 | 18.66 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1629 |

| 40 | 25 | 21 | 46 | 4.20 | 3.53 | 7.74 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1619 |

| 41 | 15 | 7 | 22 | 2.22 | 1.04 | 3.26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1609 |

| 42 | 24 | 30 | 54 | 5.13 | 6.41 | 11.53 | 2 | 0.42 | 0 | 0 | 1600 |

| 43 | 11 | 2 | 13 | 2.07 | 0.38 | 2.44 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.19 | 1590 |

| 44 | 23 | 1 | 24 | 3.34 | 0.15 | 3.48 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.15 | 1580 |

| 45 | 20 | 8 | 28 | 2.56 | 1.02 | 3.58 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1570 |

| 46 | 11 | 5 | 16 | 1.56 | 0.71 | 2.27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1560 |

| 47 | 14 | 16 | 30 | 1.87 | 2.13 | 4.00 | 2 | 0.27 | 2 | 0.27 | 1550 |

| 48 | 64 | 6 | 70 | 8.15 | 0.76 | 8.92 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 1.40 | 1540 |

| 49 | 65 | 14 | 79 | 10.90 | 2.35 | 13.24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1530 |

| 50 | 17 | 14 | 31 | 2.05 | 1.69 | 3.73 | 1 | 0.12 | 2 | 0.24 | 1520 |

| 51 | 27 | 4 | 31 | 4.36 | 0.65 | 5.01 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 2.91 | 1510 |

| 52 | 22 | 18 | 40 | 2.73 | 2.24 | 4.97 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1500 |

| 53 | 56 | 8 | 64 | 7.37 | 1.05 | 8.42 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1490 |

Table header key: Age, assigned model ages based on Tables S2 and S3 (cal year A.D.); B, total fish bone count; B+S, total fish bones plus scales; BG, fish bones per gram dry weight of sediment; CD, core depth midpoint (in centimeters); M, total mollusc fossil count (all fragments counted); MG, mollusc fossils per gram dry weight; O, total ostracode count (valves); OG, ostracode valves per gram dry weight (note rare ostracodes in LT98-07 are fragmented and appear to have been transported downslope); OM, other identifiable molluscs present [A, Anceya; C, Chytra kirki; B, Bathanalia; M, Martelia; B, Burnupia caffra(?); Ca, Caelatura]; S, total fish scale count; SG, fish scales per gram dry weight of sediment; TG, total fish fossils per gram dry weight of sediment; TI%, percentage of identifiable molluscs that are Tiphobia horei (NP05TB40 only); TO%, percentage of identifiable molluscs that are Tomichia gulleimei. Sample at 38 cm lost during preparation. Fossil fish flux calculations (as numbers of fossils accumulating per square centimeter of lake floor per year) follows methods presented in ref. 18. Table S4 shows core LT98-07; Table S5 shows NP05-TB40; and Table S6 shows MC1/KH1. Note: There are no downcore trends in fish or mollusc fossil preservation in any of the cores that might suggest a taphonomic (i.e., recent preferential dissolution) explanation for quantitative trends observed in the data.

Results

Our TEX86-inferred lake temperature data from core NP05-TB40 (Fig. 3A and Tables S7 and S8) together with published records from 200 km to the south (MC1/KH1; Fig. 2A) (12) show significant warming after the late 19th century [break points in ∼1903 (±31 y; MC-1) and ∼1854 (±50 y; NP05-TB40) (Table S9)]. Warming rates in the 20th century were unprecedented in the past ∼1,500 y (Fig. 4, Tables S7 and S8, and Fig. S2). Similar temperature trends at both sites indicate lake-wide warming rather than localized changes in upwelling (21), although the impact of differences in oxycline depth on temperature between sites is also evident. Lake-level fluctuations over the past two millennia (22) (Fig. 3B) are uncorrelated with water temperature at the deeper core sites (MC1 and LT98-07M) but show a negative (P = 0.05) correlation at site NP05-TB40 before the onset of 20th century warming (Tables S10 and S11).

Table S7.

TEX86 data: Data for core NP05-TB40, with temperatures calculated from the global lakes calibration of ref. 33

| Depth, cm | TEX86 | Temperature, °C | Model age, cal year A.D. |

| 1.5 | 0.7193191 | 26.2 | 2003 |

| 2.5 | 0.7131414 | 25.9 | 1998 |

| 3.5 | 0.7035016 | 25.4 | 1993 |

| 5.5 | 0.7020184 | 25.3 | 1982 |

| 7.5 | 0.6981632 | 25.1 | 1968 |

| 9.5 | 0.6894518 | 24.7 | 1948 |

| 10.5 | 0.6941301 | 24.9 | 1933 |

| 12.5 | 0.6920604 | 24.8 | 1899 |

| 14.5 | 0.6873199 | 24.6 | 1874 |

| 16.5 | 0.6790971 | 24.1 | 1809 |

| 18.5 | 0.6819401 | 24.3 | 1752 |

| 20.5 | 0.6840913 | 24.4 | 1688 |

| 22.5 | 0.6796431 | 24.2 | 1616 |

| 24.5 | 0.6730918 | 23.8 | 1538 |

| 26.5 | 0.6769116 | 24.0 | 1452 |

| 28.5 | 0.6801971 | 24.2 | 1358 |

| 30.5 | 0.6819589 | 24.3 | 1258 |

| 33.5 | 0.675911 | 24.0 | 1094 |

| 37.5 | 0.6866739 | 24.5 | 850 |

| 39.5 | 0.6740983 | 23.9 | 717 |

| 41.5 | 0.6798109 | 24.2 | 505 |

This calibration yields excellent agreement between reconstructed and instrumentally determined modern temperatures, and a rate of warming in the last century (0.135 °C/decade) that is within error of instrumental and modeled temperatures 0.129 ± 0.023 (21).

Table S8.

TEX86 data: Data for core MC1-KH1, with temperatures calculated from the global lakes calibration of Powers et al. (33)

| Model age, cal year A.D. | TEX86 | Temperature, °C |

| 1996 | 0.752 | 27.844 |

| 1986 | 0.749 | 27.708 |

| 1976 | 0.733 | 26.873 |

| 1966 | 0.722 | 26.314 |

| 1956 | 0.720 | 26.206 |

| 1946 | 0.710 | 25.729 |

| 1936 | 0.707 | 25.537 |

| 1926 | 0.705 | 25.474 |

| 1918 | 0.709 | 25.676 |

| 1898 | 0.698 | 25.100 |

| 1879 | 0.678 | 24.104 |

| 1865 | 0.679 | 24.144 |

| 1852 | 0.687 | 24.550 |

| 1838 | 0.698 | 25.107 |

| 1824 | 0.711 | 25.772 |

| 1809 | 0.700 | 25.226 |

| 1794 | 0.704 | 25.434 |

| 1779 | 0.696 | 25.028 |

| 1764 | 0.686 | 24.510 |

| 1748 | 0.694 | 24.881 |

| 1733 | 0.700 | 25.222 |

| 1700 | 0.691 | 24.771 |

| 1683 | 0.672 | 23.767 |

| 1666 | 0.701 | 25.279 |

| 1649 | 0.672 | 23.779 |

| 1631 | 0.688 | 24.587 |

| 1614 | 0.688 | 24.581 |

| 1596 | 0.668 | 23.578 |

| 1577 | 0.702 | 25.325 |

| 1559 | 0.683 | 24.328 |

| 1540 | 0.685 | 24.460 |

| 1521 | 0.697 | 25.047 |

| 1501 | 0.678 | 24.078 |

| 1481 | 0.680 | 24.214 |

| 1461 | 0.674 | 23.880 |

| 1441 | 0.676 | 23.967 |

| 1420 | 0.670 | 23.670 |

| 1400 | 0.700 | 25.183 |

| 1378 | 0.694 | 24.902 |

| 1357 | 0.700 | 25.219 |

| 1335 | 0.715 | 25.993 |

| 1319 | 0.707 | 25.553 |

| 1297 | 0.695 | 24.961 |

| 1274 | 0.691 | 24.736 |

| 1252 | 0.716 | 25.998 |

| 1229 | 0.687 | 24.538 |

| 1205 | 0.698 | 25.109 |

| 1182 | 0.700 | 25.201 |

| 1158 | 0.694 | 24.918 |

| 1134 | 0.699 | 25.150 |

| 1110 | 0.704 | 25.387 |

| 1085 | 0.686 | 24.519 |

| 1060 | 0.679 | 24.122 |

| 1035 | 0.672 | 23.803 |

| 1009 | 0.680 | 24.177 |

| 984 | 0.695 | 24.942 |

| 958 | 0.673 | 23.837 |

| 931 | 0.676 | 23.970 |

| 905 | 0.675 | 23.945 |

| 878 | 0.680 | 24.206 |

| 851 | 0.681 | 24.220 |

| 824 | 0.673 | 23.837 |

| 796 | 0.688 | 24.615 |

| 768 | 0.691 | 24.762 |

| 740 | 0.671 | 23.709 |

| 711 | 0.697 | 25.030 |

| 682 | 0.695 | 24.928 |

| 653 | 0.688 | 24.576 |

| 624 | 0.701 | 25.269 |

| 594 | 0.701 | 25.264 |

| 565 | 0.710 | 25.712 |

| 534 | 0.707 | 25.580 |

| 504 | 0.704 | 25.384 |

Reconstructed warming at this site exceeds the rate of instrumentally measured warming over the last century, likely due to the effects of a shallowing oxycline on the TEX86 producers. This effect is less apparent at the shallower NP05-TB40 site. To explore potential changes in GDGT sources and their possible impact on the TEX86 signal, we quantified the relative abundance of branched to isoprenoidal tetraethers (BIT) (34). BIT values were less than 0.3 in all samples and are uncorrelated to TEX86 values.

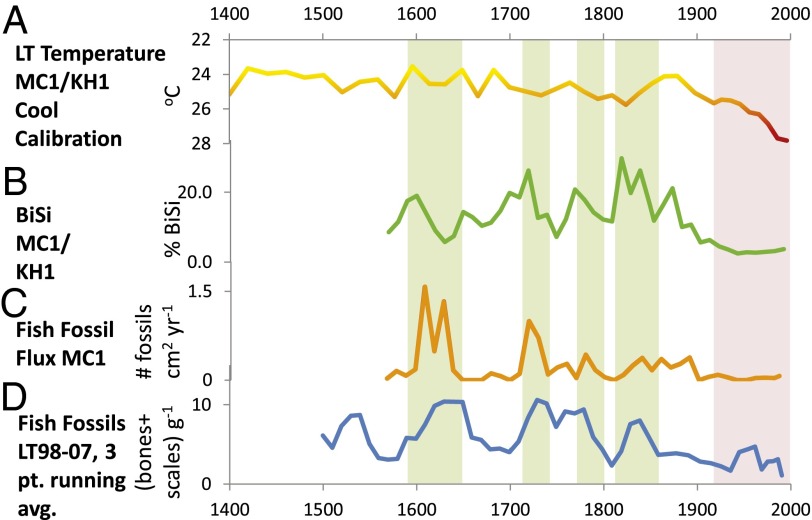

Fig. 2.

Paleoecological records from cores MC1/KH1 and LT98-07 from A.D. 1400 to 2000. (A) TEX86 reconstructed lake temperatures (note inverted scale) (12), using a “cool-lake” calibration (29). (B) Percentage of sediment as BiSi, dominantly derived from diatom fossils (12). (C) Fish fossil flux (number of fossils per square centimeter of lake floor per year; 3-point running average). (D) LT98-07 fish fossil abundance (bones plus scales per gram dry weight of sediment), 3-point average, showing similar trends to the MC1/KH1 record. Green rectangles denote periods of high diatom and fish production. Pink rectangle denotes 20th century high temperatures, low diatom production, and low fish production.

Table S9.

Break point analysis results for analyzed variables

| Variable | Break point, cal year A.D. | 95% CI (±) |

| NP05 (Kigoma)-TEX temperature, °C | 1854 | 50.44 |

| NP05-molluscs, g−1 | 1451 | 224.6 |

| NP05-fish scales, g−1 | 1614 | 168.68 |

| NP05-fish bones, g−1 | 1743 | 134.68 |

| LT98-07-fish (bones + scales), g−1 | 1768 | 143.52 |

| MC1 (Kalya)-TEX temperature, °C | 1903 | 31.06 |

| MC1-BiSi | 1872 | 27.08 |

| MC1-fish fossil flux, no.⋅cm−2⋅y−1 | 1866 | 70.58 |

Break point calculations performed in R, using the “segmented” package.

Fig. 4.

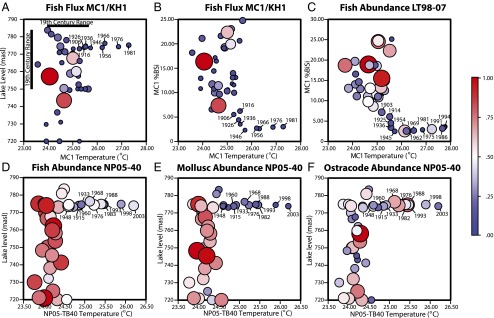

Fossil abundances of fish, molluscs, and ostracodes relative to key paleoenvironmental variables, showing distinct 20th century trends and declining abundances in all fossils except ostracodes. Color and size of bubbles are proportional to the maximum value for each dataset, with warmer colors indicative of greater abundances. (A) Fish fossil flux for core MC1/KH1 for given lake levels and MC1 TEX temperatures (19th century ranges also shown). (B) Fish fossil flux for core MC1/KH1 for given MC1 %BiSi and MC1 TEX temperatures. (C) Fish fossil abundance for core LT98-07 for given MC1 %BiSi and MC1 TEX temperatures. (D) Fish fossil abundance for core NP05-40 for given lake levels and NP05-TB40 TEX temperatures. (E) Mollusc fossil abundance for core NP05-40 for given lake levels and NP05-40 TEX temperatures. (F) Ostracode fossil abundance for core NP05-40 for given lake levels and NP05-40 TEX temperatures.

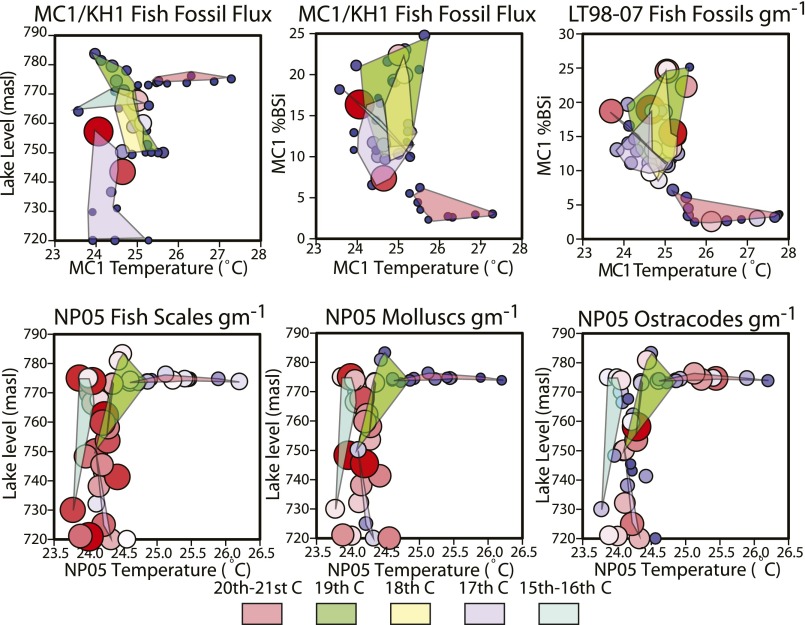

Fig. S2.

Fossil abundances of fish, molluscs, and ostracodes in relation to key paleoenvironmental variables. Color and size of bubbles is proportional to the maximum value for each dataset. Colored polygons show range of variation for each century for the past 500 or 600 y. Note distinct cluster space and low values associated for all fish and mollusc abundances (but not ostracodes) for the 20th century clusters.

Table S10.

Correlation matrices (P values) for core NP05-40

| Variable | Lake level | NP05 fish scales, g−1 | NP05 fish bones, g−1 | NP05-mollusc fossils, g−1 | NP05-ostracode valves, g−1 |

| All data | |||||

| NP05-40 TEX86 | 0.425647536 (0.089) | −0.739406622 (0.0001) | −0.69723676 (0.0004) | −0.717773379 (0.0002) | −0.227091146 (0.322) |

| Lake level | −0.34537518 (0.066) | −0.463044933 (0.011) | −0.43455422 (0.018) | −0.140837543 (0.466) | |

| NP05 scales, g−1 | 0.63387024 (<0.00001) | 0.603753726 (0.00002) | 0.17391001 (0.271) | ||

| NP05 bones, g−1 | 0.699723 (<0.00001) | 0.109598205 (0.492) | |||

| NP05-molluscs | −0.092710154 (0.559) | ||||

| Before TEX86 break point | |||||

| NP05-40 TEX86 | −0.256527936 (0.050) | −0.590435261 (0.094) | 0.463804954 (0.209) | −0.131170937 (0.737) | −0.162866008 (0.676) |

| Lake level | −0.021700724 (0.939) | −0.18461004 (0.51) | −0.045158922 (0.873) | −0.381533844 (0.161) | |

| NP05 scales, g−1 | 0.02621041 (0.927) | −0.002870965 (0.992) | 0.180593293 (0.519) | ||

| NP05 bones, g−1 | 0.423737856 (0.116) | −0.090637948 (0.748) | |||

| NP05-molluscs | −0.218431839 (0.434) | ||||

| Since TEX86 break point | |||||

| TEX86 | −0.419317445 (0.301) | −0.241843088 (0.449) | −0.703594418 (0.011) | −0.712301466 (0.009) | −0.104186517 (0.748) |

| Lake level | 0.453087222 (0.104) | 0.586726698 (0.027) | 0.325791432 (0.256) | 0.051469274 (0.863) | |

| NP05 scales, g−1 | 0.620397724 (0.0006) | 0.398679881 (0.039) | 0.203741188 (0.308) | ||

| NP05 bones, g−1 | 0.757266734 (<0.00001) | 0.445658177 (0.02) | |||

| NP05-molluscs | 0.587929328 (0.001) | ||||

Bold P values < 0.05. Shown are whole dataset, before TEX break point, and since TEX break point (1854).

Table S11.

Correlation matrices (P values)

| Variable | MC1-TEX86 | MC1-BiSi | MC1-fish fossil flux | LT-98-07 fish bones + scales |

| Whole dataset | ||||

| Lake level | 0.102992553 (0.468) | −0.296201787 (0.033) | −0.034158582 (0.81) | −0.234932522 (0.0935) |

| MC1-TEX86 | −0.362657167 (0.0004) | −0.164736782 (0.136) | −0.170319982 (0.113) | |

| MC1-BiSi | 0.071623235 (0.507) | 0.0885958 (0.412) | ||

| D.A. 0.17306 (0.276) | D.A. 0.32 (0.036) | |||

| R.A. 0.174 (0.118) | R.A. 0.287 (0.008) | |||

| MC1-fish fossil flux | 0.374053872 (0.0005) | |||

| After TEX break point | ||||

| Lake level | −0.070717394 (0.836) | −0.458591134 (0.156) | −0.191002533 (0.623) | −0.103476221 (0.762242) |

| MC1-TEX86 | −0.388335405 (0.238) | 0.264811575 (0.491) | −0.032544192 (0.924) | |

| MC1-BiSi | 0.630303332 (0.0688) | −0.435058112 (0.181) | ||

| D.A. 0.972 (<0.001) | D.A. -0.161 (0.51) | |||

| R.A. 0.702 (0.003) | R.A. -0.0003 (0.999) | |||

| MC1-fish fossil flux | 0.030200134 (0.93) | |||

| Before TEX break point | ||||

| Lake level | −0.230045375 (0.139) | −0.116673264 (0.467) | 0.089780085 (0.567) | −0.187370856 (0.241) |

| MC1-TEX86 | 0.166275287 (0.14) | −0.03442182 (0.763) | −0.080563863 (0.486) | |

| MC1-BiSi | −0.052420197 (0.646) | −0.020266773 (0.861) | ||

| D.A. −0.065 (0.738) | D.A. -0.019(0.922) | |||

| R.A. −0.041 (0.731) | R.A. 0.044(0.711) | |||

| MC1-fish fossil flux | 0.361346325 (0.001) | |||

Mahale area core records (MC1 and LT98-07). Shown are whole dataset, since TEX break point (1903, ∼50 y before the start of commercial pelagic fishing), and before TEX break point. MC1 BiSi data are compared with the nearby LT-98-07 fish bone record because there was insufficient mud available remaining in LT-98-07 samples after fossil preparations to perform BiSi analyses. D.A., decadal average smoothing calculations. All data gaps filled with nearest neighbor (as long as it is within 10 y of neighbor). All data used where at least one of the variables had raw data. R.A., Three-point running average smoothing calculations. Correlations with P < 0.05 are highlighted in bold.

As an index of diatom primary production, biogenic silica (BiSi) (measured only at site MC1) shows a strong negative relationship with temperature; high diatom production is associated (P < 0.001) with low water temperatures (Fig. 2B) (10). Some deviations from this correlation occur, presumably because of other factors like changes in wind intensity that affect vertical mixing. The correlation is somewhat stronger after the onset of the recent precipitous decline in BiSi (∼1872 ± 27 y), as TEX86 temperatures rose rapidly. The association was weaker when surface temperatures were cooler, which would have enabled seasonal mixing to boost primary production (21).

Fish fossil abundances decreased at all three sites during the 20th century (Figs. 2 C and D, and 3 C and D). At NP05-TB40, fish fossils (total bones plus scales) are significantly negatively correlated with TEX86 temperature and lake level for the entire period, whereas fish bones alone are reduced only after the shift toward recent rapid warming (Table S10). The lowest fish fossil abundances in this core are observed in the late 20th century. Changes in fish fossil flux in MC1 (primarily sardines Limnothrissa miodon and Stolothrissa tanganicae) show a marginally significant (P = 0.069) negative relationship with BiSi after the onset of warming but not before (Figs. 2C and 4A). Overall, the timing of changes in fish fossil flux (MC1) closely mirrors that of the BiSi record (MC1), being episodically high during cool periods of the early 17th and early 18th century, at intermediate levels through much of the 19th century, and low throughout the 20th century (break point, ∼1866 ± 71 y). The lowest temperatures at site MC1 (early 17th century) correspond with the highest fish fossil abundances in the entire record. Major swings in fish fossil flux, typical of boom/bust population cycles observed among pelagic sardines on 101–2-y timescales elsewhere (13), occurred well before to the start of commercial fishing in the mid-20th century. In the nearby LT98-07M core, fish fossils (mainly sardines plus their predators, Lates spp.) show a weak negative correlation with temperature, an earlier onset of declines (∼1768 ± 144 y), and especially sharp decreases since the late 19th century (Figs. 2D and 4C). Late-20th century fish fossil abundances are the lowest observed over the entire ∼500-y record at LT98-07, and both decadal and running averages for the MC1 fossil fish flux and BiSi data are highly significantly correlated after the onset of recent warming (Table S11). Conversely, the highest fish fossil abundances occur about the mid-17th and early 18th century, when Lake Tanganyika temperatures were low and diatom production was high. Fish fossil abundances in NP05-TB40 were high but variable from the ∼6th to 18th centuries, followed by long-term declines since ∼1800 (Figs. 3 C and D and 4D and Fig. S2).

Two of our three cores were collected below the oxic zone, but the shallower (76-m) NP05-TB40 core allows us to assess changes in the endemic benthic invertebrates in parallel with pelagic fish. Fossil concentrations of the dominant deep-water gastropods (Tiphobia horei and Tomichia gulleimei; Table S5) were consistently high between the ∼6th and ∼15th centuries, followed by a long-term decline (break point, ∼1451 ± 225 y), with extremely low numbers of shells encountered in the late 20th century (Figs. 3E and 4E). Mollusc abundances are strongly negatively correlated with lake temperature for both the entire period (P < 0.001) and under recent warming (P = 0.009), and are also positively related to lake level (entire dataset only, P = 0.018). Ostracode fossil abundances (Figs. 3F and 4F) are not correlated with temperature or lake level; 20th century concentrations are within the range observed before the ∼18th century.

Table S5.

Fossil count data: NP05-TB40

| CD | B | S | BG | SG | O | OG | M | MG | TI% | TO% | OM | Year A.D. |

| 1.5 | 12 | 22 | 12.61 | 23.1 | 379 | 398.38 | 32 | 33.64 | 16 | 83.3 | ___ | 2003 |

| 2.5 | 16 | 21 | 12.41 | 16.3 | 753 | 584.02 | 38 | 29.47 | 33.3 | 66.7 | ___ | 1998 |

| 3.5 | 39 | 35 | 19.86 | 17.8 | 1,420 | 723.12 | 90 | 45.32 | 20.0 | 40.0 | A,C | 1993 |

| 4.5 | 32 | 30 | 20.87 | 19.6 | 1,960 | 1,278.57 | 116 | 75.67 | 20.0 | 40.0 | A | 1988 |

| 5.5 | 42 | 44 | 22.62 | 23.7 | 1,394 | 750.66 | 90 | 47.93 | 7.1 | 78.6 | B | 1982 |

| 6.5 | 60 | 54 | 30.09 | 27.1 | 2,241 | 1,123.91 | 143 | 71.47 | 0.0 | 100.0 | ___ | 1976 |

| 7.5 | 67 | 53 | 27.89 | 22.1 | 2,663 | 1,108.40 | 160 | 66.60 | 60.0 | 33.3 | B | 1968 |

| 8.5 | 43 | 45 | 18.32 | 19.2 | 1,386 | 590.64 | 126 | 53.69 | 4.3 | 95.7 | ___ | 1960 |

| 9.5 | 49 | 46 | 30.60 | 28.7 | 1,168 | 729.43 | 87 | 54.33 | 14.3 | 85.7 | ___ | 1948 |

| 10.5 | 34 | 15 | 28.37 | 12.5 | 718 | 599.17 | 77 | 64.26 | 10.0 | 90.0 | ___ | 1933 |

| 11.5 | 23 | 27 | 16.53 | 19.4 | 720 | 517.33 | 81 | 58.20 | 33.3 | 66.7 | ___ | 1915 |

| 12.5 | 31 | 44 | 11.82 | 16.8 | 919 | 350.55 | 104 | 39.67 | 12.5 | 87.5 | ___ | 1899 |

| 13.5 | 61 | 62 | 25.60 | 26.0 | 1,122 | 470.91 | 177 | 74.29 | 92.9 | 7.1 | ___ | 1886 |

| 14.5 | 70 | 61 | 32.12 | 28.0 | 1,035 | 474.95 | 133 | 61.03 | 0.0 | 100.0 | ___ | 1874 |

| 15.5 | 75 | 58 | 36.63 | 28.3 | 1,913 | 934.21 | 161 | 78.62 | 25.0 | 75.0 | ___ | 1863 |

| 16.5 | 68 | 91 | 31.95 | 42.8 | 2,200 | 1,033.69 | 219 | 102.90 | 10.0 | 90.0 | ___ | 1809 |

| 17.5 | 72 | 46 | 42.84 | 27.4 | 1,326 | 788.94 | 132 | 78.54 | 0.0 | 100.0 | ___ | 1781 |

| 18.5 | 108 | 47 | 58.38 | 25.4 | 1,033 | 558.40 | 212 | 114.60 | 9.5 | 85.7 | A | 1752 |

| 19.5 | 70 | 45 | 53.26 | 34.2 | 842 | 640.63 | 209 | 159.02 | 17.4 | 78.3 | B | 1721 |

| 20.6 | 62 | 39 | 54.66 | 34.4 | 1,206 | 1,063.19 | 122 | 114.17 | 0.0 | 92.3 | Ca | 1688 |

| 21.6 | 38 | 33 | 46.58 | 40.5 | 1,018 | 1,247.88 | 68 | 83.36 | 0.0 | 100.0 | ___ | 1653 |

| 22.5 | 61 | 62 | 41.74 | 42.4 | 1,512 | 1,034.54 | 162 | 109.13 | 20.0 | 80.0 | ___ | 1616 |

| 23.5 | 73 | 86 | 38.35 | 45.2 | 1,185 | 622.52 | 168 | 88.26 | 26.3 | 68.4 | Ca | 1578 |

| 24.5 | 70 | 62 | 50.12 | 44.4 | 879 | 629.30 | 218 | 153.92 | 30.8 | 69.2 | ___ | 1538 |

| 25.5 | 61 | 69 | 41.69 | 47.2 | 1,132 | 773.74 | 223 | 157.21 | 27.3 | 72.7 | ___ | 1495 |

| 26.5 | 75 | 37 | 62.31 | 30.7 | 917 | 761.89 | 307 | 255.07 | 31.3 | 68.8 | ___ | 1452 |

| 27.5 | 59 | 51 | 48.08 | 41.6 | 546 | 444.90 | 244 | 198.82 | 30.0 | 70.0 | ___ | 1406 |

| 28.5 | 81 | 65 | 37.50 | 30.1 | 683 | 316.17 | 496 | 229.60 | 57.6 | 36.4 | M | 1358 |

| 29.5 | 71 | 69 | 53.39 | 51.9 | 717 | 539.19 | 272 | 198.15 | 15.0 | 85.0 | ___ | 1309 |

| 30.5 | 67 | 61 | 47.36 | 43.1 | 1,711 | 1,209.52 | 270 | 182.38 | 35.3 | 64.7 | ___ | 1258 |

| 31.5 | 95 | 70 | 43.73 | 32.2 | 542 | 249.50 | 305 | 140.40 | 38.9 | 55.6 | M | 1205 |

| 32.5 | 21 | 16 | 30.45 | 23.2 | 732 | 1,061.38 | 117 | 169.65 | 15.8 | 84.2 | ___ | 1151 |

| 33.5 | 63 | 64 | 51.38 | 52.2 | 1,198 | 977.03 | 203 | 159.03 | 14.3 | 85.7 | ___ | 1094 |

| 34.5 | 80 | 65 | 43.68 | 35.5 | 953 | 520.35 | 350 | 191.11 | 18.5 | 81.5 | ___ | 1036 |

| 35.5 | 88 | 51 | 66.65 | 38.6 | 2,169 | 1,642.66 | 285 | 206.37 | 30.0 | 70.0 | ___ | 976 |

| 36.5 | 91 | 54 | 76.41 | 45.3 | 612 | 513.89 | 245 | 205.73 | 39.1 | 47.8 | M | 914 |

| 37.5 | 123 | 42 | 76.35 | 26.1 | 536 | 332.70 | 323 | 204.52 | 64.7 | 35.3 | ___ | 850 |

| 38.5 | 82 | 52 | 71.30 | 45.2 | 908 | 723.84 | 238 | 203.17 | 52.4 | 47.6 | ___ | 785 |

| 39.5 | 55 | 58 | 38.13 | 40.2 | 1,290 | 894.26 | 286 | 198.26 | 61.9 | 38.1 | ___ | 717 |

| 40.5 | 60 | 56 | 42.23 | 39.4 | 688 | 484.23 | 399 | 280.83 | 57.1 | 39.3 | A | 648 |

| 41.5 | 55 | 52 | 51.57 | 48.8 | 984 | 922.71 | 191 | 179.10 | 52.9 | 35.3 | M,B | 577 |

| 42.5 | 47 | 46 | 38.64 | 37.8 | 303 | 249.13 | 338 | 277.91 | 85.2 | 14.8 | ___ | 505 |

For details, please refer to the legend of Table S4.

The large decline since about the 16th century in fossil mollusc abundances, which are negatively correlated with temperature (P = 0.0002), is consistent with shallowing depth distributions of deep-water snails as warming led to the shallowing of the oxycline (decreasing wind speeds could have also contributed to this, but we have no direct indicators of past wind speeds). The NP05-TB40 core site currently lies within the low oxygen zone of the lake floor (dissolved O2 concentrations vary seasonally between 0.7 and 5.0 mg⋅L−1), but historic water temperature measurements and TEX86 data suggest that it transitioned from permanent oxygenation in the 19th century to the current state of intermittent low-oxygen conditions. During the same period, there was no trend in fossil ostracode abundance, presumably reflecting the adaptation of numerous species of ostracodes to low-oxygen waters. Although ostracodes cannot tolerate fully anoxic bottom waters, the core site appears to have been above the threshold concentrations of O2 these animals require throughout the Late Holocene. There was no indication that major lake level fluctuations over the last ∼400 y affected benthic invertebrates. The most extreme mollusc declines occurred under stable lake levels during the 20th century. These declines followed a ∼10-m fall in lake level in the late 19th century (8); however, declining water levels would almost certainly have deepened profundal oxygenation, which would be expected to yield enhanced habitat for mollusc populations at the core site, contrary to what we observed.

The decline of deep-water snails for more than a century is concerning not only with regard to Tanganyika’s remarkable endemic gastropods but also because numerous other animal groups would likely be affected by the same underlying environmental changes (17). The narrow, steep strip of littoral habitat at the lake margins (Fig. 1B) is home to most of Tanganyika’s biodiversity (5). Combining historic dissolved oxygen (DO) trends with coastal bathymetry from both regions represented by our cores reveals enormous loss of oxic habitat. In 1946 [the earliest DO record (23)], the maximum depth (110 m) of the 4 mg⋅L−1 oxygen threshold corresponded to habitable lake floor areas of 92.8 and 65.87 km2 for the Mahale and Kigoma areas, respectively. As the threshold DO isobaths rose (90 m in 1956, 80 m in 1993, 70 m in 2002, and 62 m in 2012), habitable area shrank rapidly (Fig. 1B), culminating in a ∼38% reduction in habitable lake floor since 1946 (Fig. 3G).

Discussion

Recognition of sharp declines in pelagic fish fossils as Lake Tanganyika warmed over the last ∼150 y brings clarity to the causes of falling fishery yields. Declines in fish abundances began well before the explosive growth of commercial fisheries on the lake in the mid-20th century (ref. 3; United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization FishStat Database, www.fao.org/fishery/statistics/en) (Fig. 3G) and are apparent across all study sites. The unprecedented lows in fish abundances during the 20th century, when temperature rose and primary production fell (Fig. 4), leave little doubt that climate warming has undercut fishery potential independent of fishing effort and practices. This is not to say that declines in sardine catches since the mid-20th century can be attributed solely to climate warming. The early phase of commercial fishing certainly overharvested some species, especially larger predators (www.fao.org/fishery/statistics/en). Nevertheless, the decline in fish fossil abundance before commercial fishing, and the striking correlations between fish, BiSi, and temperature since the early 20th century, suggest that pelagic fish production responds strongly to climate change on 101–2-y timescales. It is possible that rising fishing pressure has further decimated sardine stocks in recent decades, but this direct human pressure is operating against a backdrop of warming-induced shifts in ecosystem production that appears to limit pelagic fish biomass.

Paleoecological data also clearly show that the reduction in water column mixing in Lake Tanganyika has caused the oxygenated habitat to shrink, yielding mollusc declines. The broad negative correlation between lake temperature and mollusc and fish fossils suggests that climate warming and intensifying stratification have been important in rapidly altering both benthic and pelagic components of the Lake Tanganyika ecosystem. Furthermore, continued warming can be expected to exacerbate benthic habitat loss, potentially affecting dozens of profundal fishes and invertebrates as well as hundreds of littoral species (5).

The collapse of diatom production, pelagic fishes, and profundal molluscs over the last century coincides with the highest temperatures inferred for the past ∼500 y (Fig. 4 and Fig. S2). There can be no doubt that climate change is playing a pivotal role in these trends, and that further warming and strengthening stratification lie ahead, barring a major increase in windiness. Moreover, our findings are consistent with a linkage between rising temperatures, increasing stratification, and declining primary production in low-latitude lakes (24) and oceans (25), emphasizing the need for ecosystem and fisheries managers to monitor these relationships carefully. To sustain Lake Tanganyika’s extraordinary endemic biodiversity, the conservation community, cognizant governments, and international agencies must recognize these long-term trends in designing management plans. If fishery managers ignore ongoing reductions in the energy base of the pelagic food web, the susceptibility of this critical resource to overfishing will become even more acute.

Methods

Geochronology.

The geochronology of the three core sites was established from downcore excess 210Pb and 137Cs profiles analyzed at the US Geological Survey (USGS) Santa Cruz radiochemistry laboratory, and corroborated by accelerator mass spectrometry 14C dates. 14C analyses were conducted at the University of Arizona Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Laboratory on terrestrial plant material found in the cores (Table S3). For further details, see Table S2.

Table S3.

14C age data

Table S2.

210Pb data

| Core name | D, cm | MD, cm | CM, g⋅cm−2 | 226Ra, dpm⋅g−1 | xs210Pb, dpm⋅g−1 | 137Cs, dpm⋅g−1 | LSR, cm⋅y−1 | MAR, mg⋅cm−2⋅y−1 | AYI, year A.D., ± |

| NP05-TB40 | 1–2 | 1.5 | 1.41 | 4.1 ± 0.2 | 24.0 ± 1.2 | 0 ± 0.00 | 0.38 | 266.96 | 2002.9 ± 0.4 |

| 2–3 | 2.5 | 2.76 | 4.2 ± 0.2 | 20.3 ± 1.2 | 0 ± 0.00 | 0.29 | 268.55 | 1997.8 ± 0.4 | |

| 3–4 | 3.5 | 3.99 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 19.3 ± 1.2 | 0 ± 0.00 | 0.26 | 240.98 | 1992.7 ± 0.5 | |

| 4–5 | 4.5 | 4.99 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 17.3 ± 0.9 | 0 ± 0.00 | 0.25 | 231.46 | 1988 ± 0.6 | |

| 5–6 | 5.5 | 6.13 | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 19.8 ± 1.1 | 0.1 ± 0.01 | 0.23 | 170.84 | 1982.4 ± 0.6 | |

| 6–7 | 6.5 | 7.18 | 3.6 ± 0.1 | 18.4 ± 1.0 | 0 ± 0.00 | 0.21 | 148.94 | 1975.6 ± 0.8 | |

| 7–8 | 7.5 | 8.13 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 17.1 ± 1.0 | 0.1 ± 0.00 | 0.2 | 127.47 | 1968.3 ± 1 | |

| 8–9 | 8.5 | 9.22 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 14.6 ± 0.8 | 0.1 ± 0.00 | 0.18 | 115.61 | 1959.8 ± 1.3 | |

| 9–10 | 9.5 | 10.16 | 4.0 ± 0.2 | 16.8 ± 0.9 | 0.2 ± 0.01 | 0.16 | 71.03 | 1948.3 ± 1.9 | |

| 10–11 | 10.5 | 11.28 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 11.4 ± 0.8 | 0.2 ± 0.01 | 0.14 | 65.39 | 1932.9 ± 3.2 | |

| 11–12 | 11.5 | 12.31 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 7.4 ± 0.7 | 0.1 ± 0.01 | 0.12 | 57.6 | 1914.9 ± 5.7 | |

| 12–13 | 12.5 | 13.34 | 4.2 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 0.1 ± 0.01 | 0.11 | 74.32 | 1898.6 ± 9.3 | |

| 13–14 | 13.5 | 14.27 | 3.7 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 0.1 ± 0.01 | 0.11 | 90.51 | 1886.4 ± 13.3 | |

| 14–15 | 14.5 | 15.28 | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.7 | 0 ± 0.00 | 0.11 | 74.42 | 1874.4 ± 19.9 | |

| 15–16 | 15.5 | 16.18 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.9 | 0 ± 0.00 | 0.11 | 109.65 | 1863.3 ± 27.5 | |

| 16–17 | 16.5 | 17.05 | 3.6 ± 0.1 | −0.1 ± 0.7 | 0 ± 0.00 | — | — | — | |

| 17–18 | 17.5 | 18.06 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 1.0 | 0 ± 0.00 | — | — | — | |

| 18–19 | 18.5 | 18.95 | 3.1 ± 0.1 | −0.1 ± 0.7 | 0 ± 0.00 | — | — | — | |

| 19–20 | 19.5 | 19.97 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 1.0 | 0 ± 0.00 | — | — | — | |

| 20–21.25 | 20.625 | 20.8 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.7 | 0 ± 0.00 | — | — | — | |

| 21.25–22 | 21.625 | 21.47 | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 1.1 | 0 ± 0.00 | — | — | — | |

| 22–23 | 22.5 | 22.42 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | −0.2 ± 1.0 | 0 ± 0.00 | — | — | — | |

| 23–24 | 23.5 | 23.24 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | −0.3 ± 0.7 | 0 ± 0.00 | — | — | — | |

| 24–25 | 24.5 | 24.05 | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.8 | 0 ± 0.00 | — | — | — | |

| LT-98–07M | 2–3 | 2.5 | 0.19 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 124.8 ± 2.5 | 0.9 ± 0.01 | 0.32 | 24.84 | 1993.8 ± 0.3 |

| 3–4 | 3.5 | 0.57 | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 58.0 ± 1.5 | 0.6 ± 0.03 | 0.22 | 40.18 | 1984.7 ± 0.3 | |

| 4–5 | 4.5 | 1.09 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 42.5 ± 1.2 | 0.6 ± 0.02 | 0.18 | 41.26 | 1975.5 ± 0.4 | |

| 5–6 | 5.5 | 1.98 | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 12.4 ± 1.2 | 0.1 ± 0.01 | 0.19 | 114.82 | 1969.1 ± 0.5 | |

| 6–7 | 6.5 | 2.41 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 18.1 ± 0.9 | 0 ± 0.02 | 0.19 | 69.12 | 1964.9 ± 0.5 | |

| 7–8 | 7.5 | 3.26 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 15.9 ± 1.5 | 0 ± 0.01 | 0.19 | 66.34 | 1959.4 ± 0.7 | |

| 8–9 | 8.5 | 4.01 | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 26.1 ± 1.3 | 0.1 ± 0.00 | 0.16 | 30.75 | 1950.1 ± 1 | |

| 9–10 | 9.5 | 4.72 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 16.4 ± 1.1 | 0 ± 0.00 | 0.15 | 32.44 | 1936.8 ± 1.5 | |

| 10–11 | 10.5 | 5.31 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 5.2 ± 1.0 | 0.1 ± 0.00 | 0.15 | 73.82 | 1927 ± 1.9 | |

| 11–12 | 11.5 | 5.99 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 4.5 ± 1.2 | 0.1 ± 0.00 | 0.15 | 70.57 | 1920.8 ± 2.4 | |

| 12–13 | 12.5 | 6.89 | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 5.2 ± 1.0 | 0 ± 0.00 | 0.14 | 48.04 | 1912.9 ± 3.2 | |

| 13–14 | 13.5 | 7.33 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 0.8 | 0 ± 0.00 | 0.14 | 42.14 | 1902.4 ± 4.6 | |

| 14–15 | 14.5 | 7.78 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 4.4 ± 1.1 | 0 ± 0.00 | 0.12 | 26.75 | 1887.5 ± 8.2 | |

| 15–16 | 15.5 | 8.74 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 3.5 ± 1.3 | 0 ± 0.00 | 0.11 | 16.68 | 1863.3 ± 20.6 | |

| 16–17 | 16.5 | 9.42 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 1.2 | 0 ± 0.00 | — | — | — |

The modern geochronology and mass sedimentation rate for select sediment cores (including NP04-KH1/MC1) collected in Lake Tanganyika are presented and discussed in refs. 12, 35–37. Cores NP05-TB40 and LT98-07 were processed and interpreted using identical analytical methods and modeling techniques. For all three cores, an age model was derived using multiple methods including a constant rate of supply (CRS) model that were corroborated by both 137Cs and accelerator mass spectrometry 14C data. All sediment cores showed an exponential downcore decrease in unsupported (excess, xs) 210Pb activity, readily interpretable as a mean linear sediment rate (0.05 cm⋅y−1 in NP04-KH1/MC1, 0.13 cm⋅y−1 in LT-98-07, and 0.1–0.38 cm⋅y−1 in NP05-TB40. In cores LT98-07 and NP04-KH1/MC1, the excess 210Pb activity exceeded 100 dpm⋅g−1 in surface sediment and decreased to parent-supported values of ∼3 dpm⋅g−1 at depth. Excess 210Pb activities in surface sediment from core NP05-TB40 did not exceed 24 dpm⋅g−1. 2A NP-05-TB40; 2B LT-98-07. AYI, average year of interval; CM, cumulative mass; D, depth; LSR, linear sedimentation rate; MAR, mass accumulation rate; MD, midpoint depth.

Paleoecology.

Wet sediment samples (∼2 g) were collected every 1 cm from each core, disaggregated in deionized water, and sieved using a 125-µm stainless-steel sieve. Wet weights were determined for an aliquot from each sample, which was oven-dried and reweighed to determine water content and to calculate original dry weights for sieved samples. For MC1 where original water content data were available fossil flux rates (as numbers of fossils per square centimeter per year) were calculated based on sedimentation rates (Fig. S1). After sieving, residues were counted at 90× magnification for ostracodes (including taphonomic variables), fish bones and scales, and molluscs on an Olympus SZX stereomicroscope. Identifications of molluscs followed refs. 26 and 27; ostracode and fish identifications relied on reference collections in the University of Arizona Laboratory of Paleolimnology.

BiSi.

BiSi methods and data were previously published in ref. 12.

Organic Geochemistry.

Sediment samples were freeze-dried and homogenized with a mortar and pestle, and lipids were extracted using a Dionex 350 Accelerated Solvent Extractor using 9:1 dichloromethane (DCM)/methanol (MeOH). Lipid extracts were separated into nonpolar and polar fractions with an Al2O3 column using 9:1 hexane/DCM and 1:1 DCM/MeOH as eluents. The polar fraction was dried under N2 gas, then redissolved in hexane/isopropanol (99:1), and filtered before analysis. The GDGTs were analyzed via HPLC/positive-ion atmospheric-pressure chemical ionization–MS at Brown University following the methods of ref. 28. Temperatures were estimated from the TEX86 values using the calibration described in ref. 29.

Bathymetry and Oxygenation.

Bathymetric mapping to a depth of >110 m was conducted at two sites: 34.1 km of shoreline flanking Kigoma Bay in northern Tanzania (adjacent to the NP05-40 core site), and 29.4 km of shoreline in central Tanzania just north of Mahale Mountains National Park (near the MC1 and LT98-07 core sites). In both areas, mapping was conducted using georeferenced echo sounding along sampling grids with 100–200 m between transects. Hypsographic curves were derived from areal integration using ArcGIS. Habitable (i.e., oxygenated) lake floor was estimated from DO profiles between 1946 and 2007, plus numerous new profiles from 2012 to 2013 (ref. 21 and this study); loss of oxygenated profundal habitat was calculated based on the depth at which DO dropped below 4 mg O⋅L−1, which we consider to be a threshold for molluscs and fish. For the 2012–2013 data, we used a linear regression through 110,611 observations (YSI optical probe) to identify the typical DO threshold depth, whereas earlier data are derived from refs. 17, 23, 30, and 31, and archival CTD Nyanza Project data (www.geo.arizona.edu/nyanza/pdf/Kinyanjui.pdf).

Statistical Methods.

Pearson correlations and associated P values were calculated in R for all datasets, considering the entire time series for each core as well as separate time intervals before and after the TEX86 temperature break points. Statistical break point analysis was performed in R (R Development Team) using the “segmented” package.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ishmael Kimerei, Donatius Chitamwebwa, the Tanzania Fisheries Research Institute staff, Rashid Tamatamah, Kiram Lezzar, Simone Alin, and the students of the Nyanza Project for coring assistance; The Nature Conservancy and its Tuungane Project staff for logistical support; and Colin Apse and two anonymous reviewers for comments on an earlier draft of this paper. Research permits were kindly provided by the Tanzania Council for Science and Technology and the University of Dar es Salaam. Digital bathymetric model data in Fig. 1 are courtesy of tcarta.com. This project was funded by the National Science Foundation [Grants ATM 0223920 (to A.S.C.) and BIO 0353765 (to A.S.C.), The Nyanza Project and Grant DEB 1030242 (to P.B.M.)], the Lake Tanganyika Biodiversity Project (A.S.C.), the USGS Coastal and Marine Geology Program (P.W.S.), Society of Exploration Geophysicists Foundation Geoscientists Without Borders Program [Grant 201401005 (to M.M.M.)], a Packard Foundation Fellowship (P.B.M.), and the Nature Conservancy [Tuungane Project (P.B.M. and M.M.M.)].

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. H.K.L. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1603237113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Shimoda Y, et al. Our current understanding of lake ecosystem response to climate change: What have we really learned from the north temperate deep lakes? J Great Lakes Res. 2011;37(1):173–193. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salzburger W, Van Bocxlaer B, Cohen AS. The ecology and evolution of the African Great Lakes and their faunas. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2014;45:519–545. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mölsä H, et al. Ecosystem monitoring in the development of sustainable fisheries in Lake Tanganyika. Aquat Ecosyst Health Manage. 2002;5(3):267–281. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen AS, Soreghan M, Scholz C. Estimating the age of ancient lake basins: An example from L. Tanganyika. Geology. 1993;21(6):511–514. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vadeboncoeur Y, McIntyre PB, Vander Zanden MJ. Borders of biodiversity: Life at the edge of the world’s large lakes. Bioscience. 2011;61(7):526–537. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mölsä H. 2008. Management of fisheries on Lake Tanganyika. PhD dissertation (Kuopio University, Kuopio, Finland)

- 7.Plisnier P-D, et al. Limnological annual cycle inferred from physical-chemical fluctuations at three stations of Lake Tanganyika. Hydrobiologia. 1999;407:45–58. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen AS, et al. Paleolimnological investigations of anthropogenic environmental change in Lake Tanganyika: IX. Summary of paleorecords of environmental change and catchment deforestation at Lake Tanganyika and impacts on the Lake Tanganyika ecosystem. J Paleolimnol. 2005;34(1):125–145. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarvala J, et al. Fish catches from Lake Tanganyika mainly reflects changes in fishery practices, not climate. Verh Int Ver Theor Angew Limnol. 2006;29:1182–1188. [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Reilly CM, Alin SR, Plisnier P-D, Cohen AS, McKee BA. Climate change decreases aquatic ecosystem productivity of Lake Tanganyika, Africa. Nature. 2003;424(6950):766–768. doi: 10.1038/nature01833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verburg P, Hecky RE, Kling H. Ecological consequences of a century of warming in Lake Tanganyika. Science. 2003;301(5632):505–507. doi: 10.1126/science.1084846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tierney J, et al. Late-twentieth-century warming in Lake Tanganyika unprecedented since AD 500. Nat Geosci. 2009;3:422–425. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baumgartner TR, Soutar A, Ferreira-Bartrina V. Reconstructions of the history of the Pacific sardine and northern anchovy populations over the past two millennia from sediments of the Santa Barbara Basin, California. CCOFI Rep. 1992;33:24–40. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finney B, et al. Paleoecological studies on variability in marine fish populations: A long-term perspective on the impacts of climatic change on marine ecosystems. J Mar Syst. 2010;79(3-4):316–326. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rummer JL, et al. Life on the edge: Thermal optima for aerobic scope of equatorial reef fishes are close to current day temperatures. Glob Change Biol. 2014;20(4):1055–1066. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verburg P, Hecky RE. The physics of warming of Lake Tanganyika by climate change. Limnol Oceanogr. 2009;54(6 part 2):2418–2430. [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Bocxlaer B, Schultheiß R, Plisnier P-D, Albrecht C. Does the decline of gastropods in deep water herald ecosystem change in Lakes Malawi and Tanganyika? Freshw Biol. 2012;57(8):1733–1744. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palacios-Fest MR, Alin SR, Cohen AS, Tanner B, Heuser H. Paleolimnological investigations of anthropogenic environmental change in Lake Tanganyika: IV. Lacustrine paleoecology. J Paleolimnol. 2005;34(1):51–71. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen AS, et al. Ecological consequences of early Late Pleistocene megadroughts in tropical Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(42):16422–16427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703873104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blome MW, Cohen AS, Lopez M. Modern distribution of ostracodes and other limnological indicators in southern Lake Malawi: Implications for paleoecological studies. Hydrobiologia. 2014;728(1):179–200. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kraemer BM, et al. Century-long warming trends in the upper water column of Lake Tanganyika. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0132490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alin SR, Cohen AS. Lake-level history of Lake Tanganyika, East Africa, for the past 2500 years based on ostracode-inferred water-depth reconstruction. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 2003;199(1-2):31–49. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Meel LIJ. 1987. Contribution à la limnologie de quatre grands lacs du Zaïre oriental: Tanganyika, Kivu, Mobutu Sese Seko (ex Albert), Idi Amin Dada (ex Edouard). Les paramètres chimiques. Fascicule A: Le Lac Tanganyika (Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique, Brussels), Document de Travail 41.

- 24.Michelutti N, Labaj A, Grooms C, Smol JP. Equatorial mountain lakes show extended periods of thermal stratification with recent climate change. J Limnol. 2016;75(2):403–408. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Behrenfeld MJ, et al. Climate-driven trends in contemporary ocean productivity. Nature. 2006;444(7120):752–755. doi: 10.1038/nature05317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown DS. Freshwater Snails of Africa and Their Medical Importance. 2nd Ed Taylor and Francis; London: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 27.West KA, Michel E, Todd JA, Brown DS, Clabaugh J. 2003. The Gastropods of Lake Tanganyika: Diagnostic Key and Taxonomic Classification with Notes on the Fauna (The International Association for Theoretical and Applied Limnology, Chapel Hill, NC), Vol 2, pp 1–132.

- 28.Schouten S, Huguet C, Hopmans EC, Kienhuis MVM, Damsté JS. Analytical methodology for TEX86 paleothermometry by high-performance liquid chromatography/atmospheric pressure chemical ionization-mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2007;79(7):2940–2944. doi: 10.1021/ac062339v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Powers LA, et al. Crenarchaeotal membrane lipids in lake sediments: A new paleotemperature proxy for continental paleoclimate reconstruction? Geology. 2004;32(7):613–616. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dubois JTh. Evolution de la température de l’oxygène dissous et de la transparence dans la baie nord du Lac Tanganika. Hydrobiologia. 1958;10(1):215–240. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plisnier P-D. 1997. Climate, Limnology and Fisheries Changes of Lake Tanganyika, FAO Technical Report (Food and Agriculture Organization, Rome), GCP/RAF/271/FIN-TD/72.

- 32.Van der Knaap M, Katonda KI, De Graaf GJ. Lake Tanganyika fisheries frame survey analysis: Assessment of the options for management of the fisheries of Lake Tanganyika. Aquat Ecosyst Health Manage. 2014;17(1):4–13. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Powers L, et al. Applicability and calibration of the TEX86 paleothermometer in lakes. Org Geochem. 2010;41(4):404–413. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hopmans EC, et al. A novel proxy for terrestrial organic matter in sediments based on branched and isoprenoid tetraether lipids. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2004;224(1-2):107–116. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Conaway CH, Swarzenski PW, Cohen AS. Recent paleorecords document rising mercury contamination in Lake Tanganyika. Appl Geochem. 2012;27(1):352–359. [Google Scholar]

- 36.McKee BA, et al. Paleolimnological investigations of anthropogenic environmental change in Lake Tanganyika: II. Geochronologies and mass sedimentation rates based on 14C and 210Pb data. J Paleolimnol. 2005;34(1):19–29. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Odigie KO, Flegal AR, Cohen AS, Swarzenski PW, Flegal AR. Using lead isotopes and trace element records from two contrasting Lake Tanganyika sediment cores to assess watershed - Lake exchange. Appl Geochem. 2014;51:184–190. [Google Scholar]