Significance

The circadian clock controls daily rhythms in genes involved in a wide range of biological processes, including signal transduction, cell division, metabolism, and behavior. The primary focus on understanding clock control of gene expression has been at the level of transcription. However, in many systems, there are examples of proteins that accumulate rhythmically from transcripts that are constitutively expressed. These data suggested that the clock regulates translation, but the underlying mechanisms were largely unknown. We show that the clock in Neurospora crassa controls the activity of translation elongation factor-2 (eEF-2) and that regulation of translation elongation leads to rhythmic translation in vitro and in vivo. These studies uncover a mechanism for controlling rhythmic protein accumulation.

Keywords: circadian clock, eEF-2, translation, translation elongation, Neurospora crassa

Abstract

The circadian clock has a profound effect on gene regulation, controlling rhythmic transcript accumulation for up to half of expressed genes in eukaryotes. Evidence also exists for clock control of mRNA translation, but the extent and mechanisms for this regulation are not known. In Neurospora crassa, the circadian clock generates daily rhythms in the activation of conserved mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways when cells are grown in constant conditions, including rhythmic activation of the well-characterized p38 osmosensing (OS) MAPK pathway. Rhythmic phosphorylation of the MAPK OS-2 (P-OS-2) leads to temporal control of downstream targets of OS-2. We show that osmotic stress in N. crassa induced the phosphorylation of a eukaryotic elongation factor-2 (eEF-2) kinase, radiation sensitivity complementing kinase-2 (RCK-2), and that RCK-2 is necessary for high-level phosphorylation of eEF-2, a key regulator of translation elongation. The levels of phosphorylated RCK-2 and phosphorylated eEF-2 cycle in abundance in wild-type cells but not in cells deleted for OS-2 or the core clock component FREQUENCY (FRQ). Translation extracts from cells grown in constant conditions show decreased translational activity in the late subjective morning, coincident with the peak in eEF-2 phosphorylation, and rhythmic translation of glutathione S-transferase (GST-3) from constitutive mRNA levels in vivo is dependent on circadian regulation of eEF-2 activity. In contrast, rhythms in phosphorylated eEF-2 levels are not necessary for rhythms in accumulation of the clock protein FRQ, indicating that clock control of eEF-2 activity promotes rhythmic translation of specific mRNAs.

Circadian rhythms are the outward manifestation of an endogenous clock mechanism common to nearly all eukaryotes. Depending on the organism and tissue, nearly half of an organism’s expressed genes are under control of the circadian clock at the level of transcription (1–4). However, mounting evidence indicates a role for the clock in controlling posttranscriptional mechanisms (5), including translation initiation (6, 7), whereas clock control of translation elongation has not been investigated.

The driver of circadian rhythms in Neurospora crassa is an autoregulatory molecular feedback loop composed of the negative elements FREQUENCY (FRQ) and FRQ RNA-interacting helicase (FRH), which inhibit the activity of the positive elements WHITE COLLAR-1 (WC-1) and WC-2 (8–11). WC-1 and WC-2 heterodimerize to form the white collar complex (WCC), which activates transcription of frequency (frq) (8, 12, 13) and activates transcription of a large set of downstream target genes important for overt rhythmicity (2, 14). One gene directly controlled by the WCC is os-4, which encodes the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase (MAPKKK) in the osmotically sensitive (OS) MAPK pathway (15). Rhythmic transcription of os-4 leads to rhythmic accumulation of the phosphorylated active form of the downstream p38-like mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) OS-2 (16). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the homolog of OS-2, Hog1, directly phosphorylates and activates the MAPK-activated protein kinase (MAPKAPK) Rck2 after acute osmotic stress (17, 18). Activated Rck2 phosphorylates EF-2 and, as a result, represses translation elongation for most mRNAs (19–21). Therefore, we hypothesized that circadian clock control of OS-2 activity in N. crassa leads to temporal control of translation elongation through rhythmic activation of RCK-2.

In support of this hypothesis, we show that clock control of OS-2 leads to rhythmic phosphorylation of RCK-2 and eEF-2 in cells grown in constant conditions. Consistent with the peak in phosphorylated eEF-2 during the subjective morning, translation elongation rates are reduced in extracts prepared from cells harvested at this time of the day. Furthermore, clock-controlled translation of GST-3 protein from constitutive mRNA levels in vivo is dependent on rhythmic eEF-2 activity, whereas rhythms in accumulation of FRQ are not dependent on rhythms in phosphorylated eEF-2. Together, these data support clock regulation of translation elongation of specific mRNAs as a mechanism to control rhythmic protein accumulation.

Results

Phosphorylation of RCK-2 Protein Requires OS-2.

Total Rck2 kinase levels, and Rck-2 phosphorylation by Hog1, increase following osmotic stress in S. cerevisiae cells (19). Rck2 then phosphorylates and inactivates EF-2, leading to general repression of translation (19, 22). To investigate if a similar mechanism exists for regulation of translation in N. crassa, we identified N. crassa RCK-2 and eEF-2 through sequence homology (Fig. S1 A and B). To determine if N. crassa RCK-2 functions in the osmotic stress response pathway, RCK-2 protein levels and phosphorylation state were measured in WT or Δos-2 cells containing a C-terminal hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged RCK-2 protein (RCK-2::HA) grown in the dark for 24 h (DD24) and then subjected to acute osmotic stress. As in yeast, N. crassa RCK-2::HA protein levels increased following osmotic stress, and this induction required OS-2 (Fig. 1A). Two forms of RCK-2::HA protein were observed by SDS/PAGE in WT cells, but not in Δos-2 cells (Fig. 1A). Consistent with the idea that the slower migrating form of RCK-2::HA was phosphorylated, the band disappeared when protein extracts were treated with λ-phosphatase but persisted in extracts treated with both λ-phosphatase and phosphatase inhibitors (Fig. 1B). In yeast, phosphorylated Rck2 is observed in osmotically stressed but not in unstressed cells (19). In contrast, phosphorylated RCK-2::HA (P-RCK-2) was already present in unstressed N. crassa cells, suggesting that OS-2–dependent phosphorylation of RCK-2 was directed by different input signals to the OS MAPK pathway, possibly signals from the circadian clock.

Fig. S1.

Sequence alignment of N. crassa RCK-2 and eEF-2. Multisequence alignment of the N. crassa RCK-2 kinase domain (A) and eEF-2 N terminus (B) to homologs in the indicated organisms. The arrow indicates the conserved threonine residue at amino acid 56 in eEF-2 that is phosphorylated.

Fig. 1.

RCK-2 protein is induced by osmotic shock. (A) Representative Western blot of protein isolated from RCK-2::HA and RCK-2::HA, Δos-2 cells grown in the dark (DD) for 24 h (DD24) and incubated with 4% (vol/vol) NaCl for the indicated times and probed with HA antibody (αHA). Amido-stained proteins served as loading controls. The data are plotted on the Right (mean ± SEM, n = 3). (B) Western blot of protein from RCK-2::HA cells grown in the dark for 24 h and incubated with 4% (vol/vol) NaCl for the indicated times and given no further treatment (Input), treated with λ-phosphatase (λ-phos), or treated with λ-phosphatase plus phosphatase inhibitors (λ-phos+inh) and probed with HA antibody. The upper arrow points to the phosphorylated form of RCK-2 and the lower arrow to the unphosphorylated protein.

eEF-2 Phosphorylation Is Regulated by RCK-2.

To determine if N. crassa eEF-2 activity is altered following an acute osmotic stress, the levels of phosphorylated eEF-2 (P-eEF-2) were examined using an antibody that recognizes P-eEF-2 phosphorylated at the conserved threonine 56 (Fig. 2A). P-eEF-2 levels increased within 5 min of addition of 4% (vol/vol) NaCl to cultures at DD24, whereas total eEF-2 levels, detected using an antibody generated to recognize all forms of eEF-2, were similar in untreated and salt-treated samples. To verify the specificity of the P-eEF-2 antibody, salt-treated samples were incubated with λ-phosphatase (Fig. 2B). As expected, eEF-2 was not detected with P-eEF-2 antibody in the λ-phosphatase–treated samples but was detected in samples treated with λ-phosphatase plus phosphatase inhibitors.

Fig. 2.

Osmotic stress-induced phosphorylation of eEF-2 is reduced in Δrck-2 cells. (A) Western blots of protein extracted from WT cells grown in DD24 and treated with 4% (vol/vol) NaCl for the indicated times and probed with phospho-specific eEF-2 antibody (αP-eEF-2) or total eEF-2 antibody (αeEF-2). The film was exposed for 15 s. (B) Western blot of protein from WT cultures grown in DD24 and incubated with 4% (vol/vol) NaCl for the indicated times and given no further treatment (Input), treated with λ-phosphatase (λ-phos), or treated with λ-phosphatase plus phosphatase inhibitors (λ-phos+inh) and probed with αP-eEF-2. The film was exposed for 1.5 s. (C) Plot of eEF-2 levels from WT, Δrck-2, Δos-2, and double mutant Δrck-2, Δos-2 cells grown in DD24 and incubated with 4% (vol/vol) NaCl for the indicated times (mean ± SEM, n = 3). The asterisks indicate a statistical difference (P < 0.05, Student’s t test). The Western blots are shown in Fig. S3.

In S. cerevisiae, Rck-2 directly phosphorylates eEF-2 (19). Immunoprecipitation of N. crassa RCK-2::HA with HA antibody resulted in coimmunoprecipitation of eEF-2 (Fig. S2), suggesting that similar to S. cerevisiae, RCK-2 may directly phosphorylate eEF-2 in response to osmotic stress. Consistent with this idea, P-eEF-2 levels were significantly lower in Δrck-2 cells compared with WT cells following osmotic stress, such that P-eEF-2 levels were reduced up to 80% in Δrck-2 cells subjected to 5 min of salt stress (Figs. 2C and S3A). However, low-level phosphorylation of eEF-2 persisted in the absence of RCK-2, indicating that in addition to RCK-2, other kinase(s) can phosphorylate eEF-2. One possible candidate kinase was the MAPK OS-2. We examined the levels of P-eEF-2 in Δrck-2, Δos-2, and double Δrck-2, Δos-2 mutant cells and found that the levels of P-eEF-2 in Δos-2 and the double Δrck-2, Δos-2 mutant strain were similar to that observed in Δrck-2 cells treated with NaCl for 5 or 15 min (Figs. 2C and S3 B and C). Furthermore, levels of total eEF-2 in Δrck-2, Δos-2, and double Δrck-2, Δos-2 mutant cells were similar to levels in WT cells (Fig. S3 A–C), indicating that unidentified kinases phosphorylate eEF-2 following osmotic stress in the absence of RCK-2 and OS-2.

Fig. S2.

RCK-2 interacts with eEF-2 in vivo. Coimmunoprecipitation of RCK-2::HA (lanes 1 and 2) and control WT cells (lane 3) treated (+) or not (–) with 4% (vol/vol) NaCl for 5 min was performed with HA antibody (αHA) and the blot was probed with αeEF-2. Amido-stained proteins served as loading controls.

Fig. S3.

Osmotic stress-induced phosphorylation of eEF-2 is reduced in Δrck-2, Δos-2, and Δrck-2, Δos-2 cells. Western blots of protein extracted from WT, Δrck-2 (A), Δos-2 (B), and Δrck-2, Δos-2 (C) cells grown at DD24 and incubated with 4% (vol/vol) NaCl for the indicated times and probed with αP-eEF-2 and αeEF-2. Amido-stained proteins served as loading controls.

RCK-2 Phosphorylation Is Regulated by the Circadian Clock.

Based on clock control of the OS MAPK pathway (15, 23) and OS-2–dependent phosphorylation of RCK-2 (Fig. 1), we predicted that the circadian clock regulates the accumulation of P-RCK-2 in constant environmental conditions. An antibody to detect P-RCK-2 was not available; however, P-RCK-2 could be separated from RCK-2 using PhosTag (Fig. S4 A and B). P-RCK-2 levels cycled, and accumulation peaked during the late subjective night (DD28–32) (Fig. 3A), slightly earlier than the peak accumulation of P-OS-2 (DD32–36) (15, 23). The earlier peak time in P-RCK-2 levels may be due to experimental error from using 4-h time points or may reflect increased P-OS-2 activity during its accumulation. RCK-2 and P-RCK-2 levels were significantly reduced in Δos-2 cells harvested at DD24 (Fig. S4C). The reduced levels of RCK-2 in Δos-2 cells in the dark suggested that in addition to control of RCK-2 phosphorylation, the OS pathway is necessary for normal expression of RCK-2. This regulation was not further investigated in this study. Consistent with clock regulation of P-RCK-2 levels through the OS pathway, P-RCK-2 accumulation was low and arrhythmic in Δos-2 cells and arrhythmic in Δfrq cells (Fig. 3 B and C and Fig. S4A).

Fig. S4.

Visualization of phosphorylated RCK-2 using PhosTag gels. (A) PhosTag Western blots of the indicated strains containing RCK-2::HA grown in constant dark (DD), harvested every 4 h over 2 d (Hrs DD), and probed with HA antibody (αHA). Phos-Tag Western blots separate P-RCK-2 from unphosphorylated RCK-2 (RCK-2) as shown by the arrows. The film exposure times were 1 s for RCK-2::HA in WT, 20 s for Δos-2, and 4 s for Δfrq. (B) Western blot of RCK-2::HA DD12 samples that were untreated (Input), treated with λ-phosphatase (λ-phos), or treated with λ-phosphatase plus phosphatase inhibitors (λ-phos+Inh); separated on a PhosTag gel; and probed with HA antibody. (C) The 2-s (S) and 1-min (L) exposure of a representative Phos-Tag Western blot using RCK-2::HA (WT) and RCK-2::HA, Δos-2 (Δos-2) DD24 samples probed with αHA. P-RCK-2 and unphosphorylated RCK-2 are indicated by the arrows. The data are plotted below (D) (mean ± SD, n = 2). Amido-stained proteins served as loading controls.

Fig. 3.

Rhythmic RCK-2 phosphorylation is regulated by clock signaling through the OS-2 pathway. Shown are plots of levels of phosphorylated RCK-2 protein (P-RCK-2). Protein was extracted from the indicated cultures grown in DD and harvested every 4 h over 2 d (Hrs DD). (A) RCK-2::HA (WT); (B) RCK-2::HA, Δos-2 (Δos-2); (C) RCK-2::HA, Δfrq (Δfrq). P-RCK-2 levels were determined using PhosTag gels (Fig. S4 A and B). The plots represent the average P-RCK-2 signal normalized to total protein for each genotype and thus do not reflect differences in P-RCK-2 levels in the strains. Rhythmicity of P-RCK-2 in WT cells was determined using F tests of fit of the data to a sine wave (dotted black line; P < 0.0001, n = 4). The levels of P-RCK-2 were arrhythmic in Δos-2 (n = 3) and Δfrq (n = 2) cells as indicated by a better fit of the data to a line (dotted black lines).

eEF-2 Phosphorylation Is Regulated by RCK-2 and the Circadian Clock.

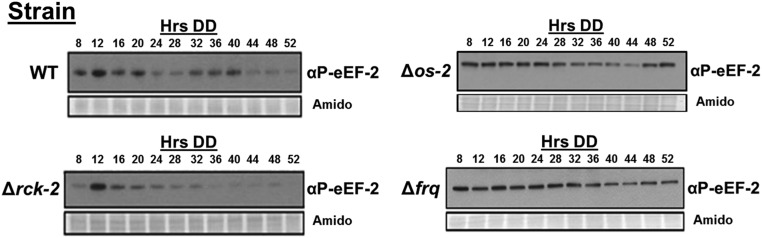

RCK-2 is required for normal induction of P-eEF-2 following acute osmotic stress (Fig. 2C), and the clock controls rhythms in the levels of P-RCK-2 (Fig. 3A). Therefore, we predicted that eEF-2 phosphorylation would be clock-controlled. Consistent with this idea, the levels of P-eEF-2, but not eEF-2, cycled over the course of the day, with peak P-eEF-2 accumulation in the subjective morning (DD36) (Fig. 4A and Figs. S5 and S6), slightly lagging the peak in P-RCK-2 levels (Fig. 3A). This delay may be due to experimental error introduced by using 4-h time points or due to the activity of phosphatases. P-eEF-2 levels fluctuated over time, but circadian rhythmicity was abolished in Δrck-2, Δos-2, and Δfrq cells (Fig. 4 B–D and Fig. S5). P-eEF-2 could be detected in both Δrck-2 (Fig. 4E) and Δos-2 cells (Fig. S5) in DD, consistent with additional kinases phosphorylating eEF-2. However, P-eEF-2 levels in Δrck-2 cells at DD36 (the time of peak P-eEF-2 levels in WT cells) were low and at levels similar to the trough levels of P-eEF-2 in WT cells at DD24 (Fig. 4E). Together, these data confirmed that clock signaling through the OS MAPK pathway and RCK-2 are necessary for rhythmic accumulation of P-eEF-2.

Fig. 4.

Clock control of eEF-2 phosphorylation requires signaling through the OS MAPK pathway and RCK-2. Shown are plots of the abundance of P-eEF-2. Protein was extracted from the indicated strains grown in DD and harvested every 4 h over 2 d (Hrs DD): (A) wild type (WT), (B) Δrck-2, (C) Δos-2, and (D) Δfrq. Protein was probed with αP-eEF-2 (Fig. S5). Plots of the data are shown (mean ± SEM, n = 3) and represent the average P-eEF-2 signal normalized to total protein for each genotype as in Fig. 3. Rhythmicity of P-eEF-2 in WT cells was determined using F tests of fit of the data to a sine wave (dotted black line; P < 0.0001), whereas P-eEF-2 levels were arrhythmic in Δrck-2 (n = 3), Δos-2 (n = 3), and Δfrq (n = 2) cells as indicated by a better fit of the data to a line (dotted black lines). (E) Representative Western blot of protein extracted from the indicated strains grown in DD for 24 and 36 h and probed with αP-eEF-2 and αeEF-2. The film was exposed for 10 s. Amido-stained proteins served as loading controls. The data are plotted below (mean ± SEM, n = 3). The asterisks indicate a statistical difference (P < 0.05, Student’s t test).

Fig. S5.

P-eEF-2 accumulates rhythmically. Shown are representative Western blots of protein extracted from the indicated strains grown in constant dark (DD), harvested every 4 h over 2 d (Hrs DD), and probed with αP-eEF-2. Amido-stained proteins served as loading controls. The exposure times for the blots varied, and therefore, the levels of αP-eEF-2 cannot be directly compared in the different strains. For Δos-2, the exposure time was 1 min, and for WT, Δrck-2, and Δfrq, the exposure time was 30 s.

Fig. S6.

Constitutive accumulation of total eEF-2 levels over the day. Shown are representative Western blots of total protein from WT cells grown in DD, harvested every 4 h over 2 d (Hrs DD), and probed with αeEF-2. Amido-stained proteins served as loading controls. The data are plotted below (mean ± SD, n = 2), where the levels of eEF-2 in WT cells were found to accumulate constitutively, as indicated by a better fit of the data to a line (dotted black line).

The extent of clock control of P-eEF-2 levels was measured by comparing the amount of P-eEF-2 from WT and Δrck-2 cells harvested at the trough (DD24) and peak (DD36) of P-eEF-2 accumulation (Fig. 4E). A twofold increase in P-eEF-2 was observed at DD36 compared with DD24 in WT cells but not Δrck-2 cells. At DD36, P-eEF-2 levels were reduced by 60% in Δrck-2 cells compared with WT cells, indicating that clock signaling through RCK-2 is responsible for over half of the total amount of P-eEF-2.

The Circadian Clock Controls Translation Elongation Rates in Vitro, and Rhythmic Protein Levels in Vivo, Through Phosphorylation of eEF-2.

We predicted that mRNA translation would be highest when P-eEF-2 levels are lowest during the subjective evening (DD24) and lowest when P-eEF-2 accumulation peaks in the subjective morning (DD36) (Fig. 4A). To test this idea, we examined translation of luciferase (luc) mRNA in cell-free translation extracts isolated from WT and mutant cells harvested at DD24 and DD36. Consistent with this hypothesis, translation of luc mRNA in WT extracts was significantly higher at DD24 than at DD36 (Fig. 5A). P-eEF-2 levels in Δrck-2 cells at DD24 and DD36 were similar to the trough levels at DD24 in WT cells (Figs. 2C and 4E), and luc mRNA translation was high in Δrck-2 translation extracts at both times of the day (Fig. 5A). These data are consistent with (i) reduced P-eEF-2 levels increasing translation extract activity and (ii) the necessity for clock signaling through RCK-2 to observe time-of-day–specific differences in the extracts’ capacity to translate luc mRNA. The levels of luc mRNA translation were higher in Δrck-2 cell extracts at both times of the day compared with the peak in WT extracts at DD24, despite finding that the steady-state levels of P-eEF-2 were similar to the WT level at DD24 (Fig. 4E). This result suggested that RCK-2 regulates additional factors in cells that reduce mRNA translation, possibly by altering levels or activities of ribosomes, tRNAs, or translation factors. The nature of this regulation will be investigated in future studies.

Fig. 5.

The circadian clock regulates translation elongation through RCK-2 and P-eEF-2. (A) In vitro translation assay of luciferase (luc) mRNA using N. crassa cell-free extracts from wild-type (WT) and Δrck-2 strains grown in DD and harvested at 24 or 36 h (Hrs DD). The average (mean ± SEM) bioluminescence signal from WT (n = 4) and Δrck-2 (n = 4) are plotted. An asterisk represents a statistical difference (P < 0.05, Student’s t test). (B) In vitro translation assay of luc mRNA using N. crassa cell-free extracts from WT and Δrck-2 strains grown in DD for 36 h. The average amount (mean ± SEM, n = 3) of bioluminescence counts per second (CPS) from WT and Δrck-2 extracts are plotted. The average amount (mean ± SEM, n = 3) of bioluminescence from Δrck-2 cell-free extract programmed with a twofold decrease (<2×) of luc mRNA (C), and WT cell-free extract programmed with twofold more (>2×) luc mRNA (D). The TFA of LUC is indicated with an arrow in B–D. (E) Luciferase assay using GST-3::LUC translational (n = 15) and gst-3::luc transcriptional (n = 24) fusion strains kept in DD for 4.5 d. The average amount (mean ± SEM) of bioluminescence is plotted. (F) Luciferase assay using GST-3::LUC translational (n = 20) and GST-3::LUC, Δrck-2 (n = 11) fusion strains kept in DD for 4.5 d. The average (mean ± SEM) bioluminescence signal is plotted.

To determine if rhythmic P-eEF-2 levels affect translation elongation rates, we used an N. crassa cell-free translation protocol (24, 25) that accurately reflects protein synthesis in vivo (24, 26). Firefly luc mRNA was used as the template in the cell-free system to determine the time of first appearance (TFA) of the luminescence signal. TFA is a measure of the time needed for the ribosome to complete protein synthesis and is indicative of translation elongation rate (25, 26). Changes in translation elongation rates as a function of eEF-2 phosphorylation were examined in cell-free extracts isolated from WT and Δrck-2 cells harvested at the time of peak P-eEF-2 levels in WT cells (DD36). As predicted, TFA was detected earlier in Δrck-2 than in WT extracts (Fig. 5B), in line with reduced P-eEF-2 levels and increased elongation rates in Δrck-2 cells compared with WT cells. In accordance with increased translation elongation rates in Δrck-2 extracts, the slope of LUC accumulation over time was twofold higher in Δrck-2 extracts compared with WT extracts (Fig. 5B). To determine TFA under conditions where LUC synthesis rates were overall similar, we examined the consequences of varying the concentration of mRNA used to program extracts. The rate of accumulation of LUC in Δrck-2 was comparable to that of WT when Δrck-2 was programmed with twofold less mRNA than WT (Fig. 5C). Importantly, the TFA was still earlier than in WT extracts, consistent with an increased elongation rate in Δrck-2 extracts. Similarly, when WT extracts were programmed with twofold more mRNA than Δrck-2 (Fig. 5D), the accumulation of LUC after TFA correspondingly increased to levels similar to Δrck-2, but TFA was still delayed relative to Δrck-2.

To examine if rhythmic accumulation of P-eEF-2 provides a mechanism to rhythmically control mRNA translation elongation in vivo, we assayed rhythmicity of a GST-3 (encoding GST)::LUC translational fusion in WT and Δrck-2 cells. This gene was chosen based on constitutive gst-3 mRNA accumulation (2) and evidence for rhythms of GST activity in mammalian cells (27). Consistent with the transcriptome data (2), a gst-3 promoter::luc fusion was constitutively expressed in WT cells (Fig. 5E). In contrast, GST-3::LUC protein levels cycled in WT but not in Δrck-2 or Δfrq cells (Fig. 5 E and F and Fig. S7), demonstrating that clock signaling through RCK-2 and eEF-2 provides a mechanism to control translation elongation and protein accumulation. However, not all mRNAs are affected by rhythmic accumulation of P-eEF-2. We found that the levels and cycling of the core clock protein FRQ were not altered in Δrck-2 cells (Fig. S8 A and B).

Fig. S7.

Rhythmic accumulation of GST-3 is abolished in a clock mutant strain. The average amount (mean ± SEM, n = 24) of bioluminescence from GST-3::LUC, Δfrq cells grown in the dark for the indicated times (Hrs DD) is plotted.

Fig. S8.

FRQ levels and rhythmicity in Δrck-2 cells are similar to WT cells. Western blots of protein extracted from WT (A) and Δrck-2 (B) cells grown in DD, harvested every 4 h over 2 d (Hrs DD), and probed with FRQ antibody (αFRQ). Amido-stained proteins served as loading controls. The data are plotted below (mean ± SEM, n = 3). Rhythmicity of FRQ in WT and Δrck-2 cells was determined using F tests of fit of the data to a sine wave (dotted black line; P < 0.0001). (Bottom) The period of the rhythms are given below the plots.

Discussion

Increasing evidence points to the importance of the circadian clock in controlling mRNA translation, including rhythmic activation of cap-dependent translation factors (6, 7, 28–30), and specific RNA binding proteins that control the translation of core clock genes (31–35). Although the initiation of translation has long been considered to be the primary control step in translation (36), a growing body of evidence points to translation elongation being regulated (37, 38), with phosphorylation and reduction in activity of eEF-2 being a central point in this control. Here, we showed that the N. crassa circadian clock, through rhythmic control of the OS MAPK pathway and downstream effector protein RCK-2, generates a rhythm in P-eEF-2 levels, peaking in the subjective day. This regulation leads to decreased translation activity and decreased translation elongation rates during the day in vitro.

N. crassa RCK-2 most closely resembles mammalian eEF-2 kinase MAPKAPK2. Similar to RCK-2 in fungi, mammalian MAPKAPK2 activity is controlled by the stress-induced p38 MAPK pathway (39, 40). MAPKAPK2 phosphorylates and activates eEF-2 kinase (eEF-2K), which in turn phosphorylates and inactivates eEF-2 (41). In mammals, several different signaling pathways converge on eEF-2K to activate or repress its activity and ultimately control the levels of P-eEF-2. In response to environmental stress, hypoxia, and nutrient status, p38 MAPK and mTOR signaling pathways inhibit eEF-2K (42–44), whereas AMP-kinase and cAMP-dependent protein kinase A signaling activate eEF-2K (45–48). N. crassa cells lack an obvious homolog of eEF-2K. Although our data showing that eEF-2 and RCK-2 coimmunoprecipitate in total protein extractions is consistent with a direct interaction between the two proteins, we cannot exclude the possibility that phosphorylation of eEF-2 by RCK-2 may be indirect and mediated through an unidentified kinase that functions similarly to eEF-2K. However, because low levels of P-eEF-2 were observed in Δrck-2, Δos-2, and Δrck-2, Δos-2 double mutants following osmotic stress (Fig. 2C and Fig. S3), it appears that RCK-2 is the major pathway leading to phosphorylation of eEF-2, although other kinases, such as AMPK, PKA, and/or TOR pathway-directed kinases, may also have minor roles. Importantly, p38, as well as TOR, AMPK activity, and cAMP levels, are clock-controlled in higher eukaryotes (49–54), suggesting that clock control of translation elongation through rhythmic eEF-2 phosphorylation may be conserved. Furthermore, recent studies have shown that eEF-2 levels cycle in abundance in mouse liver (55, 56); however, it remains to be determined if rhythms in mammalian eEF-2 levels affect its activity.

Our studies have uncovered a mechanism for circadian clock control of protein abundance through the effects of rhythmic accumulation of P-eEF-2 on protein synthesis. These data lead to additional questions: (i) To what extent does clock control of translation elongation affect rhythmic protein levels, and (ii) what is the advantage of clock control of translation elongation to the organism? Recent ribosome profiling in mammalian cells revealed that ∼10% of mRNAs with rhythmic ribosome occupancy lacked corresponding rhythmic mRNA levels (56, 57). In the mouse liver, rhythmic ribosome occupancy on ∼500 constitutively accumulating mRNAs was enriched for mRNAs containing 5′-Terminal Oligo Pyrimidine (TOP) tracts, or Translation Initiator of Short 5′-UTR (TISU) elements (58). The clock controlled the amplitude and phase of ribosome occupancy of TISU-containing mRNAs, whereas rhythmic ribosome occupancy of mRNAs containing TOP elements was primarily controlled by rhythmic feeding. Thus, in mammalian cells, both the circadian clock and feeding cycles can contribute to rhythmic translation of specific mRNAs. Consistent with clock control of eEF-2 activity promoting rhythmic translation of specific mRNAs, rather than providing a mechanism to globally control translation, we show that RCK-2, which is needed for rhythms in P-eEF-2 levels, is not necessary for rhythms in accumulation of the clock protein FRQ (Fig. S7), whereas rhythms in GST-3 protein levels require RCK-2 (Fig. 5). Although there may be several ways to achieve specificity, we speculate that a slowdown in translation elongation rate during the day could reduce the expression of mRNAs for which elongation is rate-limiting, whereas the expression of mRNAs for which initiation is rate-limiting would either not be affected or would show relatively increased translation rates as a result of increased availability of initiation factors.

The clock plays a major role in controlling metabolism (59), including energy metabolism (60) and its major currency, ATP (61–63). As translation is one of the most energy-demanding processes in the cell, it makes sense to coordinate protein translation to times of day when energy levels are highest. In N. crassa, clock-controlled mRNAs generally peak at two phases, dawn and dusk, with dusk phase enriched for genes involved in ATP-requiring anabolic processes and dawn phase enriched for genes involved in ATP-generating catabolism (1, 2). Based on our data showing that the levels of P-eEF-2 peak during the day, we predict increased rates of mRNA translation at night, directly following the peak production of ATP during the day, and in coordination with other anabolic processes, including lipid and nucleotide metabolism. In addition, environmental stress to the organism peaks during the day (27). Linking translation elongation control to stress-induced and clock-controlled MAPK signaling, as well as to nutrient sensing pathways, likely provides an adaptive mechanism to partition the energy-demanding processes of translation to times of the day that are less stressful to the organism.

Materials and Methods

Vegetative growth conditions and crossing protocols were as previously described (15, 64). Strains used in the study are listed in Table S1. Protein extraction for Western blotting of FRQ, RCK-2 (65), and eEF-2 (66) were essentially as described. Western blotting using anti-HA primary antibody (#11867423001, Roche Diagnostics), anti–eEF-2 primary antibody (#2332S, Cell Signaling Technology), and rabbit anti–phospho-eEF-2 (Thr56) primary antibody (#2331S, Cell Signaling Technology) was carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Separation of RCK-2 forms was accomplished using Phos-tag acrylamide (#300–93523, Wako Chemicals USA, Inc.). Phosphatase treatment (#P0753S, New England Biolabs) and coimmunoprecipitation using GammaBind G Sepharose beads (#17–0885-01, GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences) were as recommended by the manufacturer. In vitro translation of luc mRNA (67, 68), in vivo luciferase assays (69), and statistical analysis of rhythmic data (15) were accomplished as previously described. Detailed methods can be found in SI Materials and Methods.

Table S1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Cross | FGSC no. | DBP no. | Reference |

| Wild type | mat A, 74-OR23-IV | 2489 | |||

| Wild type | mat a, 74-OR23-IV | 4200 | |||

| ras-1bd | mat A, ras-1bd | 1858 | |||

| Δmus-51 | mat a, Δmus-51::bar+ | 9718 | |||

| Δos-2 | mat A, Δos-2::hph | 17933 | |||

| Δfrq | mat A, Δfrq::bar+ | 1228 | Bennett et al., 2013 (74) | ||

| Δfrq | mat A, ras-1bd Δfrq::hph | 7490 | |||

| Δrck-2 | mat A, Δrck-2::hph | 11545 | |||

| Δrck-2 | mat A, ras-1bd Δrck-2::hph | FGSC11545 × FGSC1858 | 1116 | This study | |

| Δrck-2, Δos-2 | mat A, Δrck-2::hph, Δos-2::hph | DBP1116 × FGSC17933 | 1394 | This study | |

| RCK-2::HA | mat A, rck-2::3xHA::hph | FGSC2489 × FGSC9718 | 1254 | This study | |

| RCK-2::HA | mat a, rck-2::3xHA::hph | FGSC2489 × FGSC9718 | 1255 | This study | |

| RCK-2::HA, ras-1bd | mat a, ras-1bd, rck2::3xHA::hph | FGSC1858 × FGSC9718 | 1251 | This study | |

| RCK-2::HA, Δos-2 | mat a, rck2::3xHA::hph, Δos-2::hph | DBP1251 × FGSC17933 | 1264 | This study | |

| RCK-2::HA, Δfrq | mat a, rck2::3xHA::hph, Δfrq::bar+ | DBP1255 × DBP1228 | 1301 | This study |

SI Materials and Methods

Strains and Growth Conditions.

Vegetative growth conditions and crossing protocols were as previously described (15, 64). Unless otherwise indicated, the strains used in this study contained the ras-1bd mutation (Table S1). RCK-2::HA homokaryotic strains (DBP 1254 mat A, rck-2::3X HA::hph, and DBP 1255; mat a, rck-2::3X HA::hph) were generated by transforming FGSC 9718 (mat a, Δmus-51::bar+) with pRCK-2::3X HA and crossing transformants (mat a, Δmus-51::bar+, rck-2::3X HA) with FGSC 2489 (mat A). pRCK-2::3X HA was generated by three-way PCR (70) combining a 2.4-kb fragment of rck-2 (without the translational stop codon), a 10× glycine linker–3× HA–hygromycin-B resistance gene (hph), and 1.5 kb of the 3′-UTR of rck-2. The resulting PCR product was cloned into pCR–Blunt vector (#K2700-20, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). Incorporation of 3× HA into the native locus was verified by PCR, and integration of the HA-tagged RCK-2 construct was confirmed by detection of a ˜75 kDa HA-tagged protein (RCK-2::HA predicted size, 72.6 kDa) in the transformants by Western blot. The GST-3::LUC translational fusion was generated by three-way PCR using a fully codon-optimized luciferase gene (71) and cotransformed with either pBP15 (DBP301) into WT (FGSC 2489) and Δfrq (DBP 1320) or with pBARGEM7-2 (DBP 425) into Δrck2 (DBP 828). The gst-3 gene was targeted for replacement by the GST-3::LUC construct via homologous recombination. Hygromycin or basta-resistant transformants were picked and screened for luciferase activity. To generate the Pgst-3::luc transcriptional fusion, a 1.3-kb promoter region of gst-3 was amplified with primers gst3SpeI F: (5′ GGACGCTACTAGTTGACAAGATT 3′) and gst3AscI R (5′ CGATGGCGCGCCGTCTGACATGGTAACG 3′). The PCR product was digested with SpeI and AscI and cloned into plasmid pRMP57 containing the codon-optimized luciferase gene. The resulting plasmid (DBP 594), targeted to the his-3 locus, was digested with PciI and cotransformed with either pBP15 (DBP 301) into wild-type 74-OR23-IV (FGSC 2489) and Δfrq (DBP 1320) cells or with pBARGEM7-2 (DBP 425) into Δrck2 (DBP 828). Hygromycin or basta-resistant transformants were picked and screened for luciferase activity. Verification of gene deletions for the strains generated in this study was accomplished by PCR, and integration of HA-tagged constructs was confirmed by Western blot. All strains containing the hph construct were maintained on Vogel’s minimal media, supplemented with 200 μg/mL of hygromycin B (#80055–286, VWR). Strains containing the bar cassette were maintained on Vogel’s minimal media lacking NH4NO3 and supplemented with 0.5% proline and 200 μg/mL of BASTA (Liberty 280 SL Herbicide). Osmotic stress was carried out on cells grown in Vogel’s minimal media, 2% (wt/vol) glucose, 0.5% arginine, pH 6.0, and shaking in constant light (LL) for 24 h at 25 °C. The cultures were transferred to constant dark (DD) for 24 h at 25 °C, and 4% (vol/vol)NaCl was added 5, 10, 15, and 30 min before harvest. Tissue for RNA and protein extraction was harvested by flash freezing in liquid N2. Circadian time course experiments were conducted as previously described (15) with cells synchronized by a light-to-dark transfer (25 °C in LL to 25 °C in DD).

Protein Extraction, Western Blotting, λ-Protein Phosphatase Treatment, and Coimmunoprecipitation.

To determine levels of RCK-2 phosphorylation, protein was extracted as previously described (65) with the following modification: The extraction buffer was 50 mM Hepes pH 7.4, 137 mM NaCl, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM sodium ortho-vanadate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1× aprotinin (#A1153, Sigma-Aldrich), 1× leupeptin hemisulfate salt (#L2884, Sigma-Aldrich), and 1× pepstatin A (#P5318, Sigma-Aldrich). To assay levels of total eEF-2 and phosphorylation of eEF-2, protein was extracted as previously described (66) with the following modification: The extraction buffer contained 100 mM Tris pH 7.0, 1% SDS. For samples that were separated on PhosTag acrylamide gels, the extraction buffer consisted of 50 mM Hepes pH 7.4, 137 mM NaCl, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, plus protease and phosphatase inhibitors. To assay FRQ protein levels, protein was extracted as previously described (65) with the following modification: The extraction buffer consisted of 50 mM Hepes pH 7.4, 137 mM NaCl, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM sodium ortho-vanadate, and 1 mM β-glycerophosphate.

Protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay (#500–0112, Bio-Rad Laboratories). Protein samples (50 μg) were separated on 10% SDS/PAGE gels and blotted to an Immobilon-P nitrocellulose membrane (#IPVH00010, Millipore) according to standard methods. Phos-tag acrylamide gels consisted of 8% SDS/PAGE gels with the addition of 35 μM Phos-tag Acrylamide AAL-107 (#300–93523, Wako Chemicals USA, Inc.) and 70 μM MnCl2 according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

RCK-2::HA was detected using rat monoclonal anti-HA primary antibody (#11867423001, Roche Diagnostics) in 5% (wt/vol) milk, 1× TBS, 0.1% Tween-20 at a concentration of 1:1,000, and anti-Rat IgG-Peroxidase secondary antibody (#A5795, Sigma-Aldrich) at a concentration of 1:5,000. Total eEF-2 protein was detected using rabbit anti–eEF-2 primary antibody (#2332S, Cell Signaling Technology) in 5% (wt/vol) BSA, 1× TBS, 0.1% Tween-20 at a concentration of 1:5,000, and anti-rabbit IgG HRP secondary antibody (#170–6515, Bio-Rad Laboratories) at a concentration of 1:10,000. Phosphorylated eEF-2 protein was detected using rabbit anti–phospho-eEF-2 (Thr56) primary antibody (#2331S, Cell Signaling Technology) in 5% (wt/vol) BSA, 1× TBS, 0.1% Tween-20 at a concentration of 1:5,000, and anti-rabbit IgG HRP secondary antibody (#170–6515, Bio-Rad Laboratories) at a concentration of 1:10,000. FRQ protein was detected using mouse monoclonal anti-FRQ primary antibody (Supernatant from clone 3G11-1B10-E2, a gift from M. Brunner’s laboratory, Heidelberg) in 7.5% (wt/vol) milk, 1× TBS, 0.1% Tween-20 at a concentration of 1:200, and anti-mouse IgG-Peroxidase secondary antibody (#170–6516, BioRad Laboratories) at a concentration of 1:10,000. Detection of all proteins was by chemi-luminescence using SuperSignal West Pico Substrate (#34077, Thermo Scientific). Western blot signals were quantitated using ImageJ (NIH) and normalized to total protein levels from amido-stained protein gels. The ratio of signal to total protein for each sample/gel (value X) was averaged (Av), and each value of X was divided by the Av signal for plotting.

To verify phosphate-specific signals, 50 μg of protein were treated with 20 U of λ-protein phosphatase (#P0753S, New England Biolabs) for 30 min at 30 °C, followed by boiling for 5 min in 1× Laemmli sample buffer. Inhibition of λ-protein phosphatase was accomplished by adding 10 mM NaF, 1 mM sodium ortho-vanadate, and 1 mM β-glycerophosphate to samples just before the addition of λ-protein phosphatase.

Coimmunoprecipitation was carried out using 25 μL of GammaBind G Sepharose beads (#17–0885-01, GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences) as recommended by the manufacturer. Rat monoclonal anti-HA antibody (1:100; #11867423001, Roche Diagnostics) was bound to prewashed beads overnight at 4 °C. Total protein (2 mg) was added to the beads and incubated overnight at 4 °C.

Cell-Free Extracts and in Vitro Translation for Assaying Luciferase.

Cell-free extracts were prepared from germinated conidia as previously described (68, 72). In vitro translation of luc mRNA was accomplished as previously described using capped pQ101-luc mRNA (67, 68). Incubations were carried out for 45 min at 26 °C, and the reactions were stopped by adding 1× passive lysis buffer (#E1941, Promega). We loaded 50 μL of luciferase assay reagent (73) and 15 μL of sample reaction per well on an OptiPlate-96 F plate (#6005279, Perkin-Elmer), and bioluminescence was then immediately measured using a Victor3-V multilabel counter (#1420–252, Perkin-Elmer). Relative bioluminescence was determined by normalizing the bioluminescence (CPS) values to the average of each plate. To examine the rate of translation elongation, the reaction buffer was modified to include 5 μM amino acids, 25 mM firefly luciferin (#306, Prolume Ltd.), and 5 mM CoA (#309, Prolume Ltd.). We loaded 25 μL of cell-free extract, 5 μL (12 ng/µL) of luc mRNA, and 20 μL of reaction buffer per well on an OptiPlate-96 F plate, and bioluminescence was continuously measured for up to 15 min.

In Vivo Luciferase Assay.

Each well of a 96-well plate was filled with 150 µL of solid assay media [1× Vogel’s salt, 0.03% glucose, 0.05% arginine, 0.5 mg/mL biotin, 0.1 M quinic acid,1.5% (wt/vol) agar, and 25 µM d-luciferin] (Gold Biotechnology) (pH 6.0). Quinic acid was added to the media to increase the amplitude of the luciferase rhythms (69). The plates were air dried for 12 h in a sterile laminar flow hood. A conidial suspension (2 × 105 cells per mL) was prepared from slant cultures, and 5 µL was used per well. The plate was covered with a breathable membrane (Diversified Biotech). The cultures were grown at 30 °C for 24 h and moved to an Envision Xcite plate reader at 25 °C (Perkin-Elmer) for measuring bioluminescence. Luminescence was counted every 90 min for at least 5 continuous days.

Statistical Analysis.

Rhythmic data were fit either to a sine wave or a line as previously described (15, 74). P values represent the probability that the sine wave best fits the data. The Student’s t test was used to determine significance in changes in the levels of P-eEF-2 and bioluminescence. Error bars in all graphs represent the SEM from at least three independent experiments, unless otherwise indicated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cheng Wu for technical assistance and for providing the luc mRNA template. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants R01-NIGMS-GM58529 and GM467721.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1525268113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Sancar C, Sancar G, Ha N, Cesbron F, Brunner M. Dawn- and dusk-phased circadian transcription rhythms coordinate anabolic and catabolic functions in Neurospora. BMC Biol. 2015;13:17. doi: 10.1186/s12915-015-0126-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurley JM, et al. Analysis of clock-regulated genes in Neurospora reveals widespread posttranscriptional control of metabolic potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(48):16995–17002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418963111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang R, Lahens NF, Ballance HI, Hughes ME, Hogenesch JB. A circadian gene expression atlas in mammals: Implications for biology and medicine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(45):16219–16224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408886111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagel DH, Kay SA. Complexity in the wiring and regulation of plant circadian networks. Curr Biol. 2012;22(16):R648–R657. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beckwith EJ, Yanovsky MJ. Circadian regulation of gene expression: At the crossroads of transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulatory networks. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2014;27:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jouffe C, et al. The circadian clock coordinates ribosome biogenesis. PLoS Biol. 2013;11(1):e1001455. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lipton JO, et al. The circadian protein BMAL1 regulates translation in response to S6K1-mediated phosphorylation. Cell. 2015;161(5):1138–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng P, He Q, He Q, Wang L, Liu Y. Regulation of the Neurospora circadian clock by an RNA helicase. Genes Dev. 2005;19(2):234–241. doi: 10.1101/gad.1266805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He Q, et al. CKI and CKII mediate the FREQUENCY-dependent phosphorylation of the WHITE COLLAR complex to close the Neurospora circadian negative feedback loop. Genes Dev. 2006;20(18):2552–2565. doi: 10.1101/gad.1463506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schafmeier T, Káldi K, Diernfellner A, Mohr C, Brunner M. Phosphorylation-dependent maturation of Neurospora circadian clock protein from a nuclear repressor toward a cytoplasmic activator. Genes Dev. 2006;20(3):297–306. doi: 10.1101/gad.360906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heintzen C, Liu Y. The Neurospora crassa circadian clock. Adv Genet. 2007;58:25–66. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2660(06)58002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Froehlich AC, Liu Y, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC. White Collar-1, a circadian blue light photoreceptor, binding to the frequency promoter. Science. 2002;297(5582):815–819. doi: 10.1126/science.1073681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Froehlich AC, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC. Rhythmic binding of a WHITE COLLAR-containing complex to the frequency promoter is inhibited by FREQUENCY. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(10):5914–5919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1030057100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith KM, et al. Transcription factors in light and circadian clock signaling networks revealed by genomewide mapping of direct targets for neurospora white collar complex. Eukaryot Cell. 2010;9(10):1549–1556. doi: 10.1128/EC.00154-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lamb TM, Goldsmith CS, Bennett L, Finch KE, Bell-Pedersen D. Direct transcriptional control of a p38 MAPK pathway by the circadian clock in Neurospora crassa. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27149. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vitalini MW, et al. Circadian rhythmicity mediated by temporal regulation of the activity of p38 MAPK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(46):18223–18228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704900104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y, Lamm R, Pillonel C, Lam S, Xu JR. Osmoregulation and fungicide resistance: The Neurospora crassa os-2 gene encodes a HOG1 mitogen-activated protein kinase homologue. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68(2):532–538. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.2.532-538.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bilsland-Marchesan E, Ariño J, Saito H, Sunnerhagen P, Posas F. Rck2 kinase is a substrate for the osmotic stress-activated mitogen-activated protein kinase Hog1. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(11):3887–3895. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.11.3887-3895.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teige M, Scheikl E, Reiser V, Ruis H, Ammerer G. Rck2, a member of the calmodulin-protein kinase family, links protein synthesis to high osmolarity MAP kinase signaling in budding yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(10):5625–5630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091610798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swaminathan S, Masek T, Molin C, Pospisek M, Sunnerhagen P. Rck2 is required for reprogramming of ribosomes during oxidative stress. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17(3):1472–1482. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-07-0632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warringer J, Hult M, Regot S, Posas F, Sunnerhagen P. The HOG pathway dictates the short-term translational response after hyperosmotic shock. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21(17):3080–3092. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-01-0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bilsland E, Molin C, Swaminathan S, Ramne A, Sunnerhagen P. Rck1 and Rck2 MAPKAP kinases and the HOG pathway are required for oxidative stress resistance. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53(6):1743–1756. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Paula RM, Lamb TM, Bennett L, Bell-Pedersen D. A connection between MAPK pathways and circadian clocks. Cell Cycle. 2008;7(17):2630–2634. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.17.6516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wei J, Zhang Y, Ivanov IP, Sachs MS. The stringency of start codon selection in the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(13):9549–9562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.447177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Z, Fang P, Sachs MS. The evolutionarily conserved eukaryotic arginine attenuator peptide regulates the movement of ribosomes that have translated it. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(12):7528–7536. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu CH, et al. Codon usage influences the local rate of translation elongation to regulate co-translational protein folding. Mol Cell. 2015;59(5):744–754. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tuñón MJ, González P, López P, Salido GM, Madrid JA. Circadian rhythms in glutathione and glutathione-S transferase activity of rat liver. Arch Int Physiol Biochim Biophys. 1992;100(1):83–87. doi: 10.3109/13813459209035264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cao R, et al. Light-regulated translational control of circadian behavior by eIF4E phosphorylation. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(6):855–862. doi: 10.1038/nn.4010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cao R, et al. Translational control of entrainment and synchrony of the suprachiasmatic circadian clock by mTOR/4E-BP1 signaling. Neuron. 2013;79(4):712–724. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cornu M, et al. Hepatic mTORC1 controls locomotor activity, body temperature, and lipid metabolism through FGF21. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(32):11592–11599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412047111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim C, Allada R. ATAXIN-2 activates PERIOD translation to sustain circadian rhythms in Drosophila. Science. 2013;340(6134):875–879. doi: 10.1126/science.1234785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y, Ling J, Yuan C, Dubruille R, Emery P. A role for Drosophila ATX2 in activation of PER translation and circadian behavior. Science. 2013;340(6134):879–882. doi: 10.1126/science.1234746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bradley S, Narayanan S, Rosbash M. NAT1/DAP5/p97 and atypical translational control in the Drosophila Circadian Oscillator. Genetics. 2012;192(3):943–957. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.143248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morf J, et al. Cold-inducible RNA-binding protein modulates circadian gene expression posttranscriptionally. Science. 2012;338(6105):379–383. doi: 10.1126/science.1217726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kojima S, et al. LARK activates posttranscriptional expression of an essential mammalian clock protein, PERIOD1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(6):1859–1864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607567104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aitken CE, Lorsch JR. A mechanistic overview of translation initiation in eukaryotes. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19(6):568–576. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richter JD, Coller J. Pausing on polyribosomes: Make way for elongation in translational control. Cell. 2015;163(2):292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu B, Qian SB. Translational reprogramming in cellular stress response. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2014;5(3):301–315. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zarubin T, Han J. Activation and signaling of the p38 MAP kinase pathway. Cell Res. 2005;15(1):11–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sudo T, Kawai K, Matsuzaki H, Osada H. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase plays a key role in regulating MAPKAPK2 expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;337(2):415–421. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaul G, Pattan G, Rafeequi T. Eukaryotic elongation factor-2 (eEF2): Its regulation and peptide chain elongation. Cell Biochem Funct. 2011;29(3):227–234. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knebel A, Morrice N, Cohen P. A novel method to identify protein kinase substrates: eEF2 kinase is phosphorylated and inhibited by SAPK4/p38delta. EMBO J. 2001;20(16):4360–4369. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Redpath NT, Foulstone EJ, Proud CG. Regulation of translation elongation factor-2 by insulin via a rapamycin-sensitive signalling pathway. EMBO J. 1996;15(9):2291–2297. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang X, et al. Regulation of elongation factor 2 kinase by p90(RSK1) and p70 S6 kinase. EMBO J. 2001;20(16):4370–4379. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Althausen S, et al. Changes in the phosphorylation of initiation factor eIF-2alpha, elongation factor eEF-2 and p70 S6 kinase after transient focal cerebral ischaemia in mice. J Neurochem. 2001;78(4):779–787. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Browne GJ, Finn SG, Proud CG. Stimulation of the AMP-activated protein kinase leads to activation of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase and to its phosphorylation at a novel site, serine 398. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(13):12220–12231. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309773200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Horman S, et al. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase leads to the phosphorylation of elongation factor 2 and an inhibition of protein synthesis. Curr Biol. 2002;12(16):1419–1423. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Redpath NT, Proud CG. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylates rabbit reticulocyte elongation factor-2 kinase and induces calcium-independent activity. Biochem J. 1993;293(Pt 1):31–34. doi: 10.1042/bj2930031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams JA, Su HS, Bernards A, Field J, Sehgal A. A circadian output in Drosophila mediated by neurofibromatosis-1 and Ras/MAPK. Science. 2001;293(5538):2251–2256. doi: 10.1126/science.1063097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hayashi Y, Sanada K, Hirota T, Shimizu F, Fukada Y. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase regulates oscillation of chick pineal circadian clock. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(27):25166–25171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212726200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pizzio GA, Hainich EC, Ferreyra GA, Coso OA, Golombek DA. Circadian and photic regulation of ERK, JNK and p38 in the hamster SCN. Neuroreport. 2003;14(11):1417–1419. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200308060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cao R, Anderson FE, Jung YJ, Dziema H, Obrietan K. Circadian regulation of mammalian target of rapamycin signaling in the mouse suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neuroscience. 2011;181:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nikaido SS, Takahashi JS. Day/night differences in the stimulation of adenylate cyclase activity by calcium/calmodulin in chick pineal cell cultures: Evidence for circadian regulation of cyclic AMP. J Biol Rhythms. 1998;13(6):479–493. doi: 10.1177/074873098129000318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lamia KA, et al. AMPK regulates the circadian clock by cryptochrome phosphorylation and degradation. Science. 2009;326(5951):437–440. doi: 10.1126/science.1172156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Robles MS, Cox J, Mann M. In-vivo quantitative proteomics reveals a key contribution of post-transcriptional mechanisms to the circadian regulation of liver metabolism. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(1):e1004047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Janich P, Arpat AB, Castelo-Szekely V, Lopes M, Gatfield D. Ribosome profiling reveals the rhythmic liver translatome and circadian clock regulation by upstream open reading frames. Genome Res. 2015;25(12):1848–1859. doi: 10.1101/gr.195404.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jang C, Lahens NF, Hogenesch JB, Sehgal A. Ribosome profiling reveals an important role for translational control in circadian gene expression. Genome Res. 2015;25(12):1836–1847. doi: 10.1101/gr.191296.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Atger F, et al. Circadian and feeding rhythms differentially affect rhythmic mRNA transcription and translation in mouse liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(47):E6579–E6588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515308112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bass J. Circadian topology of metabolism. Nature. 2012;491(7424):348–356. doi: 10.1038/nature11704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Froy O. Circadian aspects of energy metabolism and aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(4):931–940. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Burkeen JF, Womac AD, Earnest DJ, Zoran MJ. Mitochondrial calcium signaling mediates rhythmic extracellular ATP accumulation in suprachiasmatic nucleus astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2011;31(23):8432–8440. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6576-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yamazaki S, Ishida Y, Inouye S. Circadian rhythms of adenosine triphosphate contents in the suprachiasmatic nucleus, anterior hypothalamic area and caudate putamen of the rat--negative correlation with electrical activity. Brain Res. 1994;664(1-2):237–240. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91978-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marpegan L, et al. Circadian regulation of ATP release in astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2011;31(23):8342–8350. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6537-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Loros JJ, Denome SA, Dunlap JC. Molecular cloning of genes under control of the circadian clock in Neurospora. Science. 1989;243(4889):385–388. doi: 10.1126/science.2563175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Garceau NY, Liu Y, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC. Alternative initiation of translation and time-specific phosphorylation yield multiple forms of the essential clock protein FREQUENCY. Cell. 1997;89(3):469–476. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jones CA, Greer-Phillips SE, Borkovich KA. The response regulator RRG-1 functions upstream of a mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway impacting asexual development, female fertility, osmotic stress, and fungicide resistance in Neurospora crassa. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(6):2123–2136. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-03-0226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zeenko VV, et al. An efficient in vitro translation system from mammalian cells lacking the translational inhibition caused by eIF2 phosphorylation. RNA. 2008;14(3):593–602. doi: 10.1261/rna.825008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang Z, Sachs MS. Arginine-specific regulation mediated by the Neurospora crassa arg-2 upstream open reading frame in a homologous, cell-free in vitro translation system. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(1):255–261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Larrondo LF, Olivares-Yañez C, Baker CL, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC. Circadian rhythms. Decoupling circadian clock protein turnover from circadian period determination. Science. 2015;347(6221):1257277. doi: 10.1126/science.1257277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Honda S, Selker EU. Tools for fungal proteomics: Multifunctional neurospora vectors for gene replacement, protein expression and protein purification. Genetics. 2009;182(1):11–23. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.098707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gooch VD, et al. Fully codon-optimized luciferase uncovers novel temperature characteristics of the Neurospora clock. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7(1):28–37. doi: 10.1128/EC.00257-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Davis RH, de Serres FJ. Genetic and microbiological research techniques for Neurospora crassa. Methods Enzymol. 1970;17(Pt A):79–143. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dyer BW, Ferrer FA, Klinedinst DK, Rodriguez R. A noncommercial dual luciferase enzyme assay system for reporter gene analysis. Anal Biochem. 2000;282(1):158–161. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bennett LD, Beremand P, Thomas TL, Bell-Pedersen D. Circadian activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase MAK-1 facilitates rhythms in clock-controlled genes in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot Cell. 2013;12(1):59–69. doi: 10.1128/EC.00207-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]