Abstract

Background

Single pellet reaching is an established task for studying fine motor control in which rats reach for, grasp, and eat food pellets in a stereotyped sequence. Most incarnations of this task require constant attention, limiting the number of animals that can be tested and the number of trials per session. Automated versions allow more interventions in more animals, but must be robust and reproducible.

New Method

Our system automatically delivers single reward pellets for rats to grasp with their forepaw. Reaches are detected using real-time computer vision, which triggers video acquisition from multiple angles using mirrors. This allows us to record high-speed (>300 frames per second) video, and trigger interventions (e.g., optogenetics) with high temporal precision. Individual video frames are triggered by digital pulses that can be synchronized with behavior, experimental interventions, or recording devices (e.g., electrophysiology). The system is housed within a soundproof chamber with integrated lighting and ventilation, allowing multiple skilled reaching systems in one room.

Results

We show that rats acquire the automated task similarly to manual versions, that the task is robust, and can be synchronized with optogenetic interventions.

Comparison with existing methods

Existing skilled reaching protocols require high levels of investigator involvement, or, if ad libitum, do not allow for integration of high-speed, synchronized data collection.

Conclusion

This task will facilitate the study of motor learning and control by efficiently recording large numbers of skilled movements. It can be adapted for use with modern neurophysiology, which demands high temporal precision.

Keywords: Skilled reaching, Single pellet grasping, Forelimb, Motor learning, Automated task, Rat

1. Introduction

Skilled limb movements are critically important to human behavior, but impaired by a range of neurologic and orthopedic pathologies. Due to ethical limitations in humans, understanding the neural underpinnings of normal and pathologic fine motor control requires robust animal models. Rodents can learn to reach for, grasp, and eat food pellets in a sequence of stereotyped movements homologous to human reaching (Klein et al., 2012). A manual “skilled reaching task” has been used extensively to study neuronal control of skilled movement (Whishaw et al., 1986;Klein and Dunnett, 2012;Hyland, 1998;Kargo and Nitz, 2003;Kargo and Nitz, 2004), as well as model multiple neurological conditions. These include stroke (Gharbawie and Whishaw, 2006;Allred et al., 2010;Alaverdashvili and Whishaw, 2010), spinal cord injury (Girgis et al., 2007;García-Alías et al., 2009), traumatic brain injury (Whishaw et al., 1991) and movement disorders (Vergara-Aragon et al., 2003;Whishaw et al., 2007). Because rats are not naturally adept at this task, rodent skilled reaching is a useful paradigm to study motor learning as well as performance.

All but a handful of skilled reaching studies rely on a high degree of experimenter involvement (Fenrich et al., 2015). The skilled reaching task is time consuming, requiring the investigator to remain vigilant throughout training. Manpower requirements, as well as difficulty isolating reaching apparatuses, limit the number of animals that can be trained and the number of trials per session. This degree of investigator involvement also introduces variability between training sessions, and likely contributes to variability in results between (and even within) labs (Fouad et al., 2013). Further variability in training can occur due to variations between laboratory conditions, training protocols, behavioral testing apparatuses, rodent strains, and ages.

An automated skilled reaching system would overcome many of these limitations, but presents its own problems. A major issue is determining how to trigger the high-speed video required for detailed kinematic analysis. Continuous recording at high frame rates (150–300 fps) is untenable due to computational limitations. A mechanism to trigger high-speed video and other interventions that minimizes false acquisitions but captures each individual reach is therefore needed. In addition, synchronizing reaching behavior with high-speed measurements (e.g., in vivo electrophysiology) or interventions (e.g., optogenetics) would greatly enhance the utility of the skilled reaching paradigm.

We describe an automated rodent skilled reaching system that overcomes many of these problems. The apparatus exploits strategically placed sensors and real-time machine vision algorithms to automate the task without restricting subject movement. We provide the specifications for our system, describe its construction, and detail our training protocols. We verify the utility of our system by demonstrating learning rates similar to manual skilled reaching protocols, and the ability to trigger optogenetic interventions reliably with high temporal precision.

2. Materials and Methods

All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the University of Michigan animal care committee’s regulations. 18 male Long-Evans rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA), ages 10–17 weeks old (average = 16.3 +/− 2.1 weeks) were trained on the automated skilled reaching task. Animals were housed singly or in groups of 2–3 and kept on a reverse light/dark cycle.

2.1. Skilled Reaching Chamber

The skilled reaching chamber is constructed of clear polycarbonate (Figure 1, TAP Plastics, Stockton, CA). The front, side, and rear panels are bonded using acrylic cement (Tap Plastics, Stockton, CA). The removable floor panel has three rows of ten holes to allow waste to fall out and provide ventilation. Infrared sensors with direct TTL output (HoneyWell, Morristown, NJ) are placed with the beam directed through the back of the chamber. The chamber is 15.08 cm (5 15/16 inches) wide by 39.05 cm (15 3/8 inches) long by 40.64 cm (16 inches) tall. Each panel is 0.64 cm (1/4 inch) thick except the front panel, which is 0.32 cm (1/8 inch) thick.

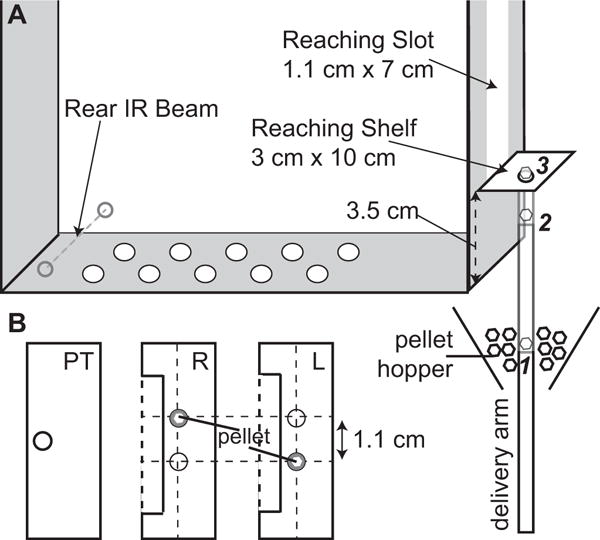

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the skilled reaching chamber. (A) The skilled reaching chamber and pellet delivery mechanism. Italicized numbers indicate pellet delivery arm positions referenced in Methods, Individual Trial Performance. (B) Reaching shelf configurations, viewed from above, for pre-training (left), and right and left paw training (middle and right, respectively).

A clear acrylic shelf is mounted in front of the reaching chamber, resting on acrylic L-brackets bolted to the front panel. Two guide holes allow secure attachment of the shelf to the brackets while allowing vertical movement in case the pellet delivery arm strikes the shelf from below.

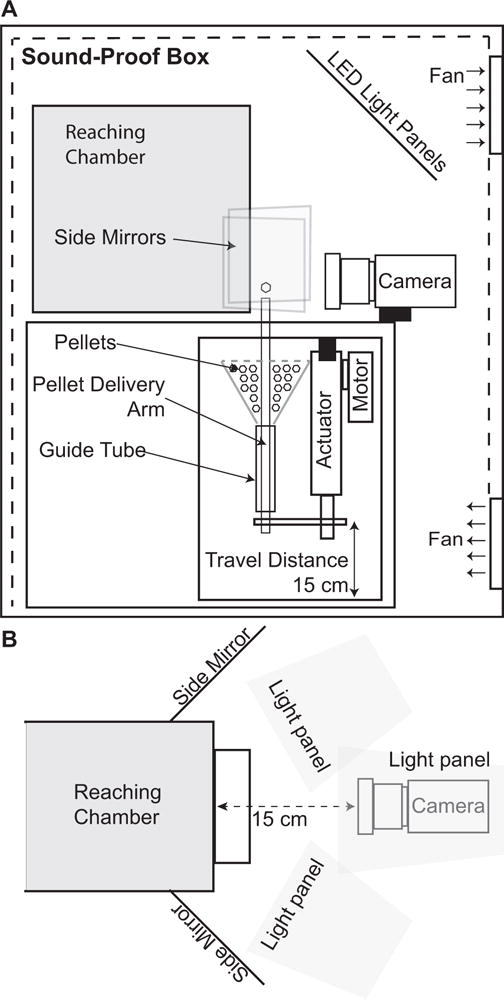

The reaching chamber rests on a custom fiberboard box (Figure 2). This box has holes in the top to allow litter from the rat to fall out of the reaching chamber and an actuator to bring the pellet to the shelf. A high-speed color video camera faces the front panel of the reaching chamber.

Fig. 2.

(A) Side view of the skilled reaching chamber, support box, actuator housing and soundproof cabinet. (B) Top view of camera position, side mirrors, and lighting panel arrangement.

A linear actuator with a 6″ range and three position digital control (Creative Werks Inc., Des Moines, IA) is mounted upside down in a custom frame below the support box (Figure 2). This orientation prevents pellet dust from accumulating inside the actuator’s position-sensing potentiometer, which caused early prototypes to fail. The end of the actuator has a steel rod connected to the pellet delivery arm. The pellet delivery rod is cast acrylic (ePlastics, San Diego, CA), slightly tapered at the bottom end and cupped at the top to accommodate a single pellet. The pellet delivery rod extends through an acrylic “guide” tube (ePlastics, San Diego, CA) to ensure a consistent vertical orientation, and is connected to a funnel mounted to the top of the frame. Before each session, the funnel is loaded with 45 mg peanut butter flavored sucrose pellets (TestDiet, St Louis, MO). The bottom of the funnel contains a foam O-ring to prevent dust from accumulating in the pellet guide assembly. The pellet delivery arm is lubricated with Teflon (DuPont, Wilmington, DE). The actuator is controlled digitally from LabVIEW (National Instruments, Austin, TX).

A wheeled, soundproof cabinet houses each reaching apparatus (Figure 2). The cabinets are lined with acoustic foam (SilentSource, Northampton, MA) and ventilated with 8 cm silent computer fans (Cooler Master, New Taipei City, Taiwan). Three custom light panels comprising LED light strips (Lighting Ever, Las Vega, NV) on 8″ by 10″ white Delrin support panels covered by 0.007″ light diffuser film (Inventables, Chicago, IL) are mounted inside the cabinet above and on either side of the reaching chamber.

2.2. Camera and Computer Hardware

Videos are recorded by a high-definition (maximum resolution: 2046 × 1086 pixels) color digital camera capable of acquisitions up to 340 frames-per-second (acA2000-340kc, Basler, Ahrensburg, Germany) with a wide angle, 8 mm fixed, 1.4 aperture C-mount lens (Computar, Tokyo, Japan). A camera-link field programmable gate array (FPGA) frame-grabber card (PCIe 1473R, National Instruments, Austin, TX) acquires the images, and an FPGA data acquisition (DAQ) task control card (NI PCIe 7841R) provides an interface with the behavior chamber and any additional equipment (e.g., electrophysiology or optogenetic systems). The experiment is controlled with, and data recorded by, a HP Z620 workstation (Hewlett Packard, Palo Alto, CA) with 32 GB of memory, running Window 7 64 bit operating system (Microsoft Corp., Seattle, WA). The large RAM specifications and 64-bit OS are required to buffer the high-resolution image data before writing to disk.

2.3. Trial Performance

Custom LabVIEW software (provided in Supplementary Material) controls the experiment. Each training session begins with the rat in the center of the reaching chamber. The pellet delivery arm is initially positioned at the “ready” position (Figure 1A, position 2), and rises to the shelf (position 3) when the rat breaks the IR beam at the back of the chamber. This ensures that the rat approaches the pellet from the back of the chamber so that its body orientation is similar on each trial (Klein and Dunnett, 2012). When the paw passes the front plane of the chamber (visible in the mirror views), video acquisition is triggered, time stamped, and labeled with the trial number. 2 seconds after the video is triggered, the pellet is lowered. This is to encourage the rat to grasp pellets in a single smooth movement, though a couple of quick reaches could still be attempted before the pellet was lowered.

2.4. Computer Vision and Video Capture

In our first prototype, we attempted reach detection with a photobeam in front of the reaching slot. However, the rat’s nose often entered the slot and falsely triggered video acquisition. Furthermore, the sensors partially obscured the side mirror views. We therefore used a real-time FPGA card to detect pixel intensity changes in front of the slot (Figure 5). Placing a grey background behind the mirrored views (on either side of the camera lens), allows for selective identification of the lighter paw. To further enhance contrast, the paw was painted with bright green nail polish (Kleancolor neon green, Santa Fe Springs, CA) that allowed robust paw detection. A rectangular region of interest for paw detection is set at the start of each session.

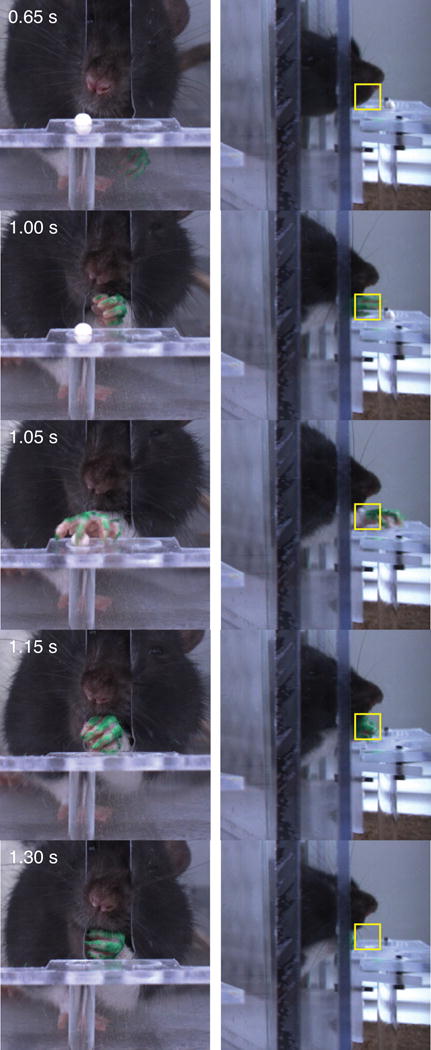

Fig. 5.

Video stills of a left handed rat performing the skilled reaching task. From top to bottom: approach, reaching (trigger frame), grasping, retrieval, and supination/pellet consumption. Left column: direct camera view; right column: view in right (rat’s left) mirror. Elapsed times are shown from the start of the video. The yellow box shows the region of interest for triggering video storage.

A user-specified number of frames is saved before and after the triggering event using a rolling buffer. We typically record at 300 frames-per-second, saving 300 frames pre-trigger and 900 frames post-trigger. This captures the full reaching motion and pellet consumption for the vast majority of trials. Individual videos are saved as binary files, as the delays caused by compression algorithms lead to frame skips. The binary videos are compressed and converted off-line to a standard format (Microsoft Video, .avi). Digital input and output lines are accessed via LabVIEW using the task control card to read the IR beam state, control the actuator, and communicate with external systems.

2.5. Training Protocol

2.5.1. Pre-training

“Pre-training” consists of familiarizing the rats with the reaching chamber and training them to activate the pellet delivery arm. One week before pre-training, rats are food restricted with the goal of maintaining body weight at 85% of normal. Food restriction continued throughout training and testing, with one day of free-feeding allowed each week. Rats were fed at least one hour after completing their daily test sessions. The amount of standard rat chow provided in the home cage was independent of the number of reward pellets obtained during task performance.

During the week prior to pre-training, rats are handled daily for 10–20 minutes and exposed to sucrose reward pellets in their home cage. On day 1 of pre-training, piles of five pellets each are placed in the front (including on the reaching shelf) and rear of the chamber. A pre-training shelf is used with a single midline hole close to the front of the chamber, allowing the rat to easily obtain a pellet with his tongue. The rat is gently placed in the center of the chamber and allowed to explore. The next day the procedure is repeated with a smaller pile of pellets at the front and the back of the chamber. At this point, the software is turned on so breaking the back IR beam causes the pellet delivery arm to bring a pellet to where the rat can obtain it with his tongue. Beginning on the third day, the number of pellets at the front and back are gradually reduced, dependent on the subject consistently eating pellets. By day 4 or 5 of pre-training, the pellet delivery arm delivers the only available reward pellet after the rat breaks the rear IR beam. By day 6, the rat should consistently move to the rear of the chamber, break the IR beam, turn around when the pellet delivery arm rises, and eat the pellet at the front of the chamber. Pre-training is complete once the rats move from the back to front of the chamber to eat a pellet ten times in under five minutes.

2.5.2. Paw-preference testing

Once the rats learn to activate the pellet delivery arm, they are evaluated for paw-preference. The delivery arm pellets are removed and two pellets are manually placed on the pre-training shelf 1.5 cm from the front plane of the reaching chamber. The pellets are aligned to the edges of the front slot too far away to be obtained by licking. From the rat’s perspective, the left pellet can only be reached with the right forelimb, and vice-versa. Paw preference is assigned to the paw used for the majority of the first ten reaches (Klein and Dunnett, 2012). Some rats use their paws to retrieve pellets within reach of their tongue during pre-training, and these reaches are counted towards paw-preference determination.

2.5.3. Full training

Full training sessions comprise one hundred reaches or sixty minutes, whichever occurs first. The appropriate shelf hole is aligned with the pellet delivery arm to restrict reaching to the right or left paw (Figure 1B). The rats are placed in the middle of the chamber, the automated system is activated, and no further intervention is required until the session ends. In pilot experiments with 3 rats (included in the 18 total reported here), the training schedule was 5 days on, 2 days off for 3 weeks. One of these rats failed to acquire the task (only 13 reaches on day 14 of training). Therefore, the remaining 15 rats were trained for 12 consecutive days in case the days off interfered with task acquisition (Fenrich et al., 2015). However, this schedule did not influence training success, and all 18 rats were therefore analyzed together. As described in more detail in the Results section, 12 rats did not acquire the task during their initial training period. 9 of these were retrained, with 5 more rats ultimately acquiring the task.

2.6. Data Analysis

Individual trials were scored by visual inspection as follows (Whishaw et al., 2008): 0 – no pellet presented or other mechanical failure; 1 - first trial success (obtained pellet on initial limb advance); 2 -success (obtained pellet, but not on first attempt); 3 - forelimb advanced, pellet was grasped then dropped in the box; 4 - forelimb advanced, but the pellet was knocked off the shelf; 5 – pellet was obtained using its tongue; 6 – the rat approached the slot but retreated without advancing its forelimb or the video triggered without a reach; 7 - the rat reached, but the pellet remained on the shelf; or 8 – the rat used its contralateral paw to reach. Initial reach success (score 1) and any success (scores 1 and 2) rates are calculated by dividing the relevant counts by the total number of reaches (sum of scores of 1, 2, 3, 4 and 7).

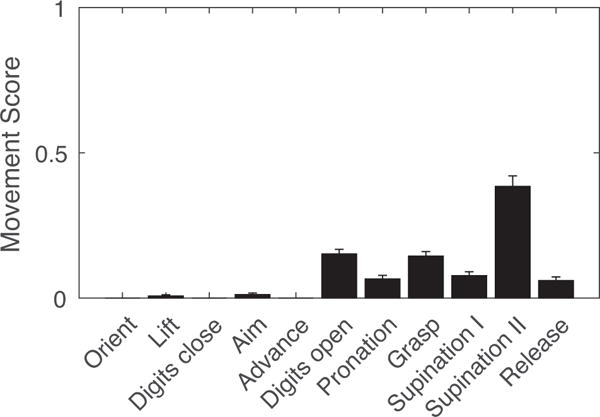

We used a semiquantitative movement component rating scale to compare limb kinematics in the automated task with manual versions. Briefly, the movement was divided into “Orient”, “Limb lift”, “Digits close”, “Aim”, “Advance”, “Digits extend and open”, “Pronate”, “Grasp”, “Supinate I”, “Supinate II”, and “Release” (described in detail in Alaverdashvili et al., 2008). A final phase (“Replace”) in which the paw is placed back on the chamber floor was omitted from our analysis because our videos were of insufficient duration. Each reaching phase was scored as normal (0), present but abnormal (0.5), or absent (1). In keeping with prior analyses, we analyzed the first three successful reaches from each session (Alaverdashvili et al., 2008;Klein and Dunnett, 2012).

2.7 Optogenetics

9 tyrosine hydroxylase-Cre (TH-Cre) rats (Witten et al., 2011) were injected with viral vectors containing double-floxed opsins or control virus (AAV-EF1α-DIO-eArch3.0-EYFP or AAV-EF1α-DIO-EYFP) into the midbrain. After paw-preferencing, these rats were implanted with optical fibers (Sparta et al., 2012) and allowed to recover for one week before full task training began. The implanted optical fibers were coupled to a patch cable, which was in turned coupled to an optical rotary joint (Doric Lenses, Quebec, Canada). As the paw traversed the slot, the PCIe-7841R board sent a TTL pulse to open a shutter (SH05, Thorlabs, Newton, New Jersey) and deliver 3 seconds of optical stimulation (532 nm light) to the ventral midbrain.

3. Results

To be practical, an automated skilled reaching system should train rats at least as effectively as, and more efficiently than, manual versions. Furthermore, the system must be reliable and easy to operate. We first present training outcomes, then describe measures of hardware and software reliability.

3.1. Training Outcomes

All 18 rats that started pre-training advanced to paw-preferencing, and ultimately to full training (7 left-handed and 11 right-handed). The average duration of pre-training and paw-preferencing combined was 11.0 +/− 2.5 days (s.d.). 6 rats acquired the task during their initial training period (performed at least 21 trials in a session). The remaining 12 rats performed no more than 8 reaches in a single training session during their initial training. Of these 12, 9 were re-trained after an average of 83.2 +/− 4.0 (s.d.) days, with 5 of these acquiring the task in their second round of training.

Because we observed significant training variability, we examined factors that might influence the rats’ propensity to acquire the task. There was no difference in weight (404.6 +/− 52.4 g vs 371.1 +/− 39.6 g, p = 0.17, t-test) or age (112.8 +/− 16.2 days vs. 115.1 +/− 12.9 days, p = 0.75, t-test) at the start of training between rats that ultimately performed or never acquired the task, respectively. However, of the 12 rats that did not acquire the task during their first training period, 10 trained in freshly assembled boxes being used for the first time. In contrast, all 6 rats that acquired the task during their first training period were trained in the older prototype. This difference in context-dependent training was highly significant (p < 10−3, chi-square test). Interestingly, 7 rats underwent their second round of training in the newer boxes, and 4 of these acquired the task this time. Thus, there seems to be a “breaking in” period for this system.

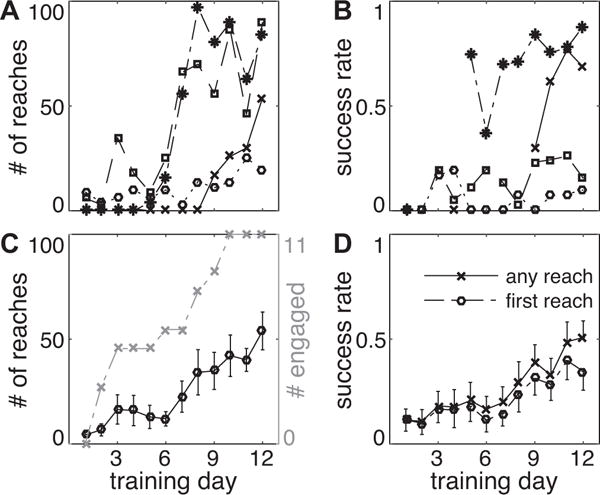

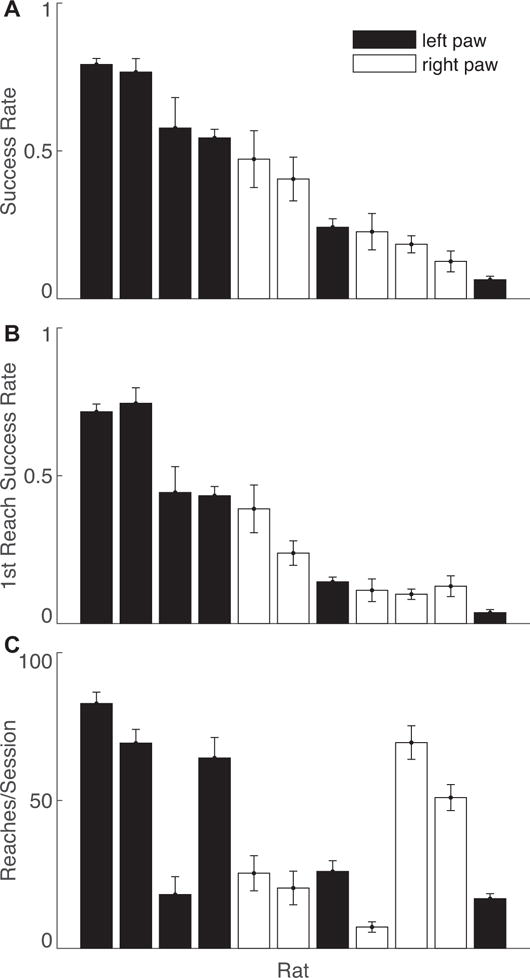

Figures 3A and C show the number of trials performed for rats that acquired the task. Note the variability in individual rat performance (Figure 3A), including the session during which they began to engage in the task. These 4 rats were selected to illustrate this variability in learning curves (Figure 3B), and that rats that performed a lot of trials did not necessarily develop a high degree of reaching proficiency (for example, the square markers). By the end of the 12-day training period, rats were averaging about 50 reaches per session (minimum 2, maximum 97 reaches on day 12). The gray lines indicate the number of rats that had engaged in the task by each day, defined as having performed at least 10 reaches in a previous session. Among rats that engaged in the task, almost half were participating by day 3, and all participated by day 10 (mean first engaged session: 5.2 +/− 3.3 sessions, mean +/− s.d.). 91.0% of “engaged” sessions were followed by another engaged session, and 7 of 11 rats were continuously engaged in the task after their first “engaged” session. Furthermore, the number of trials performed in one test session strongly predicted the number of trials performed in the next session (ρ = 0.81, p < 10−28, Pearson’s correlation coefficient). Average success rates were similar to those reported for manual (Whishaw et al., 2008) and automated (Fenrich et al., 2015) tasks (Figure 3D), achieving an average success rate of about 50% at the end of the training period.

Fig. 3.

(A) Number of trials and (B) success rate on any reach for selected rats. Plot markers indicate the same rats in A and B. (C) Average number of reaches per day (left axis, mean +/− SEM) and number of rats engaged in the task (right axis). “Engaged in the task” was defined as greater than 10 reach attempts in a previous session. (D) Average success rate on the first reach and any subsequent reach (mean +/− SEM, error bars shown in one direction for clarity).

Figure 4 further breaks down the variability in reaching skill suggested by Figures 3A and B. The range of individual success rates was slightly broader in our task, but overall similar to those reported in a manual reaching task (Gholamrezaei and Whishaw, 2009). In our task, however, success on the initial reach was highly predictive of overall reaching success. This is in contrast to the manual task, in which initial success was lower than ours, and inconsistently predictive of overall reaching success. Automated task success rates were not predicted by the number of trials performed (ρ = 0.48, p = 0.14, Pearson’s correlation coefficient). Furthermore, there was no relationship between the rats’ initial weights and the number of reaches (ρ = 0.38, p = 0.24, Pearson’s correlation coefficient) or success rate (ρ = 0.13, p = 0.70, Pearson’s correlation coefficient). These results suggest that the degree of motivation, assessed by reaching activity or degree of food restriction, does not predict reach accuracy.

Fig. 4.

Individual rat reaching performance averaged over sessions 8–12. (A) Success rates using any number of reaches per trial for each rat. (B) Success rate on the first reach per trial for each rat. (C) Number of trials per session performed by each rat. All values are mean +/− SEM.

Qualitative limb kinematics were also similar to those described in other versions of the task (Whishaw et al., 2008;Fenrich et al., 2015). Frame-by-frame analysis shows a typical reach sequence beginning with the rat orienting to the pellet (Figure 5, top panels). Next, the rats briefly advance the nose and sniff, followed by lifting the preferred paw and reaching through the front slot towards the pellet. Grasping commences once the paw is directly above and often angled obliquely away from midline. The paw grasps the pellet, elevates, supinates as it retracts through the slot, and delivers the pellet to the mouth. These components were quantified with a standard rating scale (see Section 2.5, Data Analysis), revealing similar patterns to manual skilled reaching (Figure 6, compare to Controls in Figure 7 of (Alaverdashvili et al., 2008)). A notable difference is that both Supination components are relatively impaired in the automated task. Upon careful review, we found that the fifth (“pinky”) digit sometimes caught in the unused shelf hole, restricting paw supination and withdrawal. In these cases, the rat moved its snout to the pellet, which was held against the shelf by the pronated paw. In the majority of reaches, however, the paw supinated and retracted unimpeded from the slot.

Fig. 6.

Movement subscores for 3 successful reaches from each test session (mean +/− SEM).

3.2. Automated Pellet Delivery System

No mechanical failures occurred during the test period or with subsequent use of this system. To further quantify the system’s reliability, we examined the rate of pellet delivery failures – that is, the number of times a pellet was not accurately delivered when the rat triggered the photobeam. This could happen if the pellet delivery arm did not travel through the hopper to the appropriate height, or if it failed to “grab” a pellet as it passed through the hopper. The former was an issue in earlier iterations of the task, but did not occur once the actuator was inverted and cleaned daily. Overall, a pellet was not delivered on 12.8% of trials during the 12-day training period. These failures were concentrated in a relatively small number of sessions – 50% of all pellet delivery failures occurred in just 11% of test sessions. As the pellet hopper became depleted, the pellets sometimes rolled off the delivery arm as it passed through the hopper. This became a problem as the number of trials increased several days into training. As long as the pellet hoppers were refilled between test sessions, however, the mechanical failure rate was always under 5%.

Another potential failure mode is inaccurate reach detection. It is critical to accurately detect specific moments during the reach to trigger both high-speed video acquisition and experimental interventions. Occasionally the video trigger would fire prematurely, resulting in a video capture when the rat was not reaching. We defined these events as video trigger errors (scored as 6 in our trial outcome data). Overall, video trigger errors occurred at a rate of 3.6%. These errors were not evenly distributed across sessions or rats; one rat accounted for 47.7% of all such errors. This rat had unusually light snout fur, and it was difficult for the computer vision to distinguish between the subject’s nose and paw. Two rats recorded zero video triggering errors, and 5 rats recorded less than 10 errors over 12 days of training.

Having optimized our system for paw detection, we began a pilot study to explore precisely timed optogenetics during skilled reaching. The rats tolerated the fiber optic implants and patch cable well. Among 1214 reaches recorded in 9 rats, only 25 (2%) false triggers occurred. Furthermore, all true triggers occurred as the paw passed through the slot (approximately the second panel from the top in Figure 5). These experiments were in an updated system with enhanced background contrast (darker gray background) and independent triggers for video acquisition and optical stimulation. While we cannot draw definitive conclusions about dopaminergic contributions to fine motor control based on these pilot data, they demonstrate the utility of this system to test precisely timed manipulations of the motor system.

4. Discussion

Rodent skilled reaching is an important tool for studying motor learning and control, but current incarnations are time-consuming and labor-intensive. We developed an automated system that enables high throughput, standardized data acquisition that can be synchronized with external devices. We show that rats can be trained with minimal investigator involvement, and that the apparatus is robust and reliable.

Many experimental systems utilizing a range of animal models are used to study fine motor control, each with distinct advantages and disadvantages. As a model system, rodents have the relative disadvantage of being phylogenetically removed from humans compared to non-human primates. For example, they lack direct cortico-motoneuronal connections, which are believed to be important for fine motor skills (Valverde, 1966;Rouiller et al., 1991;Rathelot and Strick, 2009). Nonetheless, rodents exhibit several desirable features for these experiments. The rodent motor system and forepaws are highly homologous to those of primates (Iwaniuk and Whishaw, 2000) with similar reach kinematics in health and disease (Whishaw et al., 2002). Second, a variety of experimental techniques are highly developed for rodents, some of which are unavailable in other model systems. These include high-density electrophysiology (Leventhal et al., 2012), advanced non-invasive imaging (Mishra et al., 2011), optical recording (Canales et al., 2015), and optical stimulation and inhibition of neural structures (Voigts et al., 2013;Ferenczi et al., 2016). These can all be integrated with advanced genetic techniques, especially in mice, but increasingly in rats (Witten et al., 2011;Asrican et al., 2013). Finally, rodents are relatively inexpensive and easy to house, potentially allowing a large number of animals to be tested.

Our goal was to develop an easily operated, reliable automated training system to more fully exploit these advantages. This system is relatively easy to build and operate. Once the prototype was optimized, subsequent systems took less than a week to build and get running. It is not clear why rats would not perform the task in “fresh” boxes (see Training Outcomes in Results), but later performed well in the same boxes. We carefully checked the boxes and software, and could find no differences other than when they were built. One possibility is that different scents in new and used boxes influence task performance. The problem may be circumvented by cleaning them carefully before use, or using previously trained rats to “break in” new reaching chambers before performing experiments.

As we developed our prototype, we encountered several unanticipated problems that led to frequent mechanical failures. The design presented here, however, continued to work without requiring any repair. In addition to purely mechanical issues, attention is required to ensure that the delivery arm consistently “grabs” sugar pellets as it passes through the hopper. As long as the pellet reservoir is refilled before each session, this was a rare occurrence. Occasional failures to deliver a pellet may actually be a useful feature, as it forces the rats to fully orient and detect the pellet before reaching (Klein and Dunnett, 2012).

Non-mechanical failures also occurred because of false-positive video triggers. Early prototypes used a photobeam to detect reach onset and trigger video storage, similar to the motion detector used in a recently described robotic pellet delivery system (Fenrich et al., 2015). This approach reliably captured reaches, but was also triggered by the rat’s nose on some trials without reaches. Capturing non-reaching videos creates extra work during video review, and presents memory and storage problems when recording in high resolution at high frame rates. Furthermore, false-positive triggers count as reaches, prematurely terminating test sessions. Most importantly, a major potential advantage of this system is triggering rapid interventions (e.g., optogenetics) during specific reach phases. We therefore implemented real-time FPGA image processing, focusing on a region of interest in the mirror view ipsilateral to the preferred paw. This dramatically reduced false triggers, and with some tuning reliably triggered video at a similar reach phase across trials. False positives were still an occasional problem in rats with light colored snouts. However, this can be overcome by changing the background and paw colors to enhance the contrast between image regions. Though memory and computational limitations on the FPGA card limit the complexity of real-time image detection algorithms, this technique may be further adapted to detect the paw at arbitrary stages of the reaching movement.

Compared to manual skilled reaching tasks, our version is more efficient with similar training outcomes. In most incarnations of this task, reward pellets are individually placed by a researcher, who also must activate a high-speed video camera that records for a limited duration. This limits the number of animals that can be tested, partially negating a major advantage of testing rodents instead of primates. Furthermore, direct human involvement in the experiment inherently introduces variability in test conditions. Finally, many experimental techniques that make rodents an attractive model system depend on precisely timed measurements or interventions. Since skilled reaching movements last on the order of 100 milliseconds, it is not realistic for a human experimenter to manually trigger an intervention like electrical or optical brain stimulation. We have demonstrated that it is feasible to trigger optogenetic interventions at specific moments during the reach.

One difference between our version and manual tasks is that we observed slightly more variability in reaching success across animals. This may in part be due to the fifth digit “catching” on the shelf hole that is not filled with the pellet delivery arm, which sometimes prevented limb supination and restricted paw retraction. This problem is straightforward to address by making shelves with only one hole for the pellet delivery arm. These “right-pawed” or “left-pawed” shelves would be replaced at the beginning of each test session depending on the rat’s handedness.

Of note, the success rate after multiple grasp attempts in a single trial was only slightly higher than the success rate on first reaches (Figures 3D, 4A, 4B). This was not the case in a similar analysis of a manual task (compare Figure 4 to Figure 2 in Gholamrezaei and Whishaw, 2009). Indeed, our first reach success rates were, in general, higher than in the manual task. This is likely because the pellet is lowered two seconds after the reach is initiated, preventing multiple “pawing” attempts per trial. This increase in first reach success and variability should facilitate identification of biological factors associated with successful execution of skilled limb movements.

An important issue is why individual rats engaged in the task after different numbers of test sessions. It is difficult to compare this task engagement latency to manual versions - most skilled reaching experiments require asymptotic task performance prior to testing and do not report the duration of the training phase (Klein and Dunnett, 2012). It may be that there is a fixed probability of task engagement, in which case one would predict the timing of initial task engagement to follow a Poisson distribution for large numbers of animals. Alternatively, there may be some biologic feature that predicts the probability of task engagement (e.g., “sign trackers” vs “goal trackers” (Flagel et al., 2011)), which is an important question for future study.

A similar automated system for single pellet grasping allows ad libitum training in an apparatus connected to the rat’s home cage (Fenrich et al., 2015). There are several potential advantages to providing continuous access to the reaching system. A significant problem in studying any behavior is that more trials will be performed during active periods, generally during the dark portion of the rat circadian cycle. Additionally, investigation of circadian cycle and sleep effects on performance and learning may require testing during both periods. On the other hand, a home cage system would be difficult to integrate with high-definition, high-speed video (video in the home cage task was recorded at 30 fps). Furthermore, full three-dimensional reach trajectory reconstruction is possible using our mirror system with a high-definition camera. Finally, having a separate reaching chamber allows additional apparatus to be connected to the rat (e.g., high-density electrophysiology headstages or optogenetic probes) during task performance. Thus, the home cage and our task represent complementary tools to efficiently address distinct questions.

Other automated forelimb tasks have been developed, but impose constraints on forelimb movement. For example, rodents may be trained to manipulate a lever by automatically rewarding them for correct movements (Slutzky et al., 2010;Panigrahi et al., 2015). The outcomes of such tasks are not necessarily discrete (as in, for example, a lever press task), as the amplitude and direction of the movement can be monitored. However, joystick tasks do not allow full freedom of movement. Such constrained tasks are advantageous in some situations (Kawai et al., 2015), but do not directly address the question of how fine motor skills are acquired or executed. Our task combines the ability to detect specific moments during reaches with the freedom for the animal to explore multiple kinematic solutions to the problem of acquiring the reward pellet.

Fully trained rats perform a complete reaching motion in less than a second, and evaluation of subtle changes in trajectory or paw positioning requires high-speed video evaluation. Our system enables high-speed recordings of each reach, offering the potential for automated kinematic analyses. This may be especially important to the study of motor learning. Furthermore, recovery is often observed after neurologic injury, as measured by improvement in task success rates. This recovery is often achieved by adopting compensatory strategies, rather than complete restoration of premorbid abilities (Alaverdashvili and Whishaw, 2010). Subtle changes in limb and paw movements may only be detectable by averaging quantitative kinematic parameters over large numbers of trials.

Finally, this system offers the potential to enhance the information obtained from physiologic recordings and finely timed interventions. Extracellular single unit recordings have been made during skilled reaching (Kargo and Nitz, 2004;Bosch-Bouju et al., 2014). In these analyses, single unit activity was either assessed as aggregate activity during the reaching task, or by peri-event time histograms (PETHs) aligned to a single detected event (e.g., photobeam break). Each video frame in our system is triggered by a TTL pulse, which can be synchronized with an external recording device. This should allow a detailed analysis of neuronal activity with respect to multiple, automatically detected submovements. Furthermore, large numbers of trials across many animals are often necessary to draw conclusions from single unit recordings. Patterned optogenetic stimulation has also been applied throughout the reaching task, including between reaches (Seeger-Armbruster et al., 2015). The ability to flexibly detect distinct reaching phases offers the potential to more fully exploit the power of specifically timed optogenetic interventions.

Such interventions could be especially powerful in mice, in which more genetic and molecular tools, including a variety of Cre driver lines, are available. In fact, optogenetic manipulations have been performed in mice during skilled reaching, though not with the temporal precision that we demonstrated with our FPGA-based system (Azim et al., 2014). Mouse skilled reaching chambers are essentially scaled-down versions of rat chambers, in which smaller reward pellets are used. We expect that a smaller pellet delivery arm would deliver 20 mg pellets with the same reliability that our rat-sized apparatus delivers 45 mg pellets.

Conclusions

In summary, this reliable, inexpensive, and easily fabricated automated skilled reaching system has broad applicability to the study of motor control and neurologic disease. It offers the advantages of high-throughput, real-time detection of reach submovements, and synchronization with a range of external devices. We expect that it will be an important complement to current systems, providing new insight into motor system physiology.

Supplementary Material

LabVIEW software. This zip archive contains heavily commented versions of the custom software in LabVIEW 2014 for running the apparatus.

Parts list. This Excel spreadsheet provides a list of components and approximate prices.

Movie 1. Sample successful (score 1) reaching video. Video has been downsampled to 30 fps and 956 × 480 resolution.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Roger Albin for helpful comments on the manuscript and Mariam Alaverdashvili for technical advice on the single pellet reaching task.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke [grant number K08-NS072183]; the Brain Research Foundation; the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation [grant number PDF-FBS-1454]; and the National Institute of Health [grant number T32 NS007222].

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Alaverdashvili M, Moon SK, Beckman CD, Virag A, Whishaw IQ. Acute but not chronic differences in skilled reaching for food following motor cortex devascularization vs. photothrombotic stroke in the rat. Neuroscience. 2008;157:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alaverdashvili M, Whishaw IQ. Compensation aids skilled reaching in aging and in recovery from forelimb motor cortex stroke in the rat. Neuroscience. 2010;167:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allred RP, Cappellini CH, Jones TA. The “good” limb makes the “bad” limb worse: experience-dependent interhemispheric disruption of functional outcome after cortical infarcts in rats. Behav Neurosci. 2010;124:124–132. doi: 10.1037/a0018457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asrican B, Augustine GJ, Berglund K, Chen S, Chow N, Deisseroth K, Feng G, Gloss B, Hira R, Hoffmann C, Kasai H, Katarya M, Kim J, Kudolo J, Lee LM, Lo SQ, Mancuso J, Matsuzaki M, Nakajima R, Qiu L, Tan G, Tang Y, Ting JT, Tsuda S, Wen L, Zhang X, Zhao S. Next-generation transgenic mice for optogenetic analysis of neural circuits. Front Neural Circuits. 2013;7:160. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2013.00160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azim E, Jiang J, Alstermark B, Jessell TM. Skilled reaching relies on a V2a propriospinal internal copy circuit. Nature. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nature13021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch-Bouju C, Smither RA, Hyland BI, Parr-Brownlie LC. Reduced reach-related modulation of motor thalamus neural activity in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci. 2014;34:15836–15850. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0893-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canales A, Jia X, Froriep UP, Koppes RA, Tringides CM, Selvidge J, Lu C, Hou C, Wei L, Fink Y, Anikeeva P. Multifunctional fibers for simultaneous optical, electrical and chemical interrogation of neural circuits in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:277–284. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenrich KK, May Z, Hurd C, Boychuk CE, Kowalczewski J, Bennett DJ, Whishaw IQ, Fouad K. Improved single pellet grasping using automated ad libitum full-time training robot. Behav Brain Res. 2015;281:137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferenczi EA, Zalocusky KA, Liston C, Grosenick L, Warden MR, Amatya D, Katovich K, Mehta H, Patenaude B, Ramakrishnan C, Kalanithi P, Etkin A, Knutson B, Glover GH, Deisseroth K. Prefrontal cortical regulation of brainwide circuit dynamics and reward-related behavior. Science. 2016;351:aac9698. doi: 10.1126/science.aac9698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagel SB, Clark JJ, Robinson TE, Mayo L, Czuj A, Willuhn I, Akers CA, Clinton SM, Phillips PE, Akil H. A selective role for dopamine in stimulus-reward learning. Nature. 2011;469:53–57. doi: 10.1038/nature09588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouad K, Hurd C, Magnuson DS. Functional testing in animal models of spinal cord injury: not as straight forward as one would think. Front Integr Neurosci. 2013;7:85. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2013.00085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Alías G, Barkhuysen S, Buckle M, Fawcett JW. Chondroitinase ABC treatment opens a window of opportunity for task-specific rehabilitation. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1145–1151. doi: 10.1038/nn.2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharbawie OA, Whishaw IQ. Parallel stages of learning and recovery of skilled reaching after motor cortex stroke: “oppositions” organize normal and compensatory movements. Behav Brain Res. 2006;175:249–262. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gholamrezaei G, Whishaw IQ. Individual differences in skilled reaching for food related to increased number of gestures: evidence for goal and habit learning of skilled reaching. Behav Neurosci. 2009;123:863–874. doi: 10.1037/a0016369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girgis J, Merrett D, Kirkland S, Metz GA, Verge V, Fouad K. Reaching training in rats with spinal cord injury promotes plasticity and task specific recovery. Brain. 2007;130:2993–3003. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland B. Neural activity related to reaching and grasping in rostral and caudal regions of rat motor cortex. Behav Brain Res. 1998;94:255–269. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)00157-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwaniuk AN, Whishaw IQ. On the origin of skilled forelimb movements. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:372–376. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01618-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kargo WJ, Nitz DA. Early skill learning is expressed through selection and tuning of cortically represented muscle synergies. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11255–11269. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-35-11255.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kargo WJ, Nitz DA. Improvements in the signal-to-noise ratio of motor cortex cells distinguish early versus late phases of motor skill learning. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5560–5569. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0562-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai R, Markman T, Poddar R, Ko R, Fantana AL, Dhawale AK, Kampff AR, Ölveczky BP. Motor cortex is required for learning but not for executing a motor skill. Neuron. 2015;86:800–812. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein Dunnett. Analysis of Skilled Forelimb Movement in Rats: The Single Pellet Reaching Test and Staircase Test. Current Protocols in Neuroscience. 2012 doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0828s58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein A, Sacrey LA, Whishaw IQ, Dunnett SB. The use of rodent skilled reaching as a translational model for investigating brain damage and disease. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:1030–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal DK, Gage GJ, Schmidt R, Pettibone JR, Case AC, Berke JD. Basal Ganglia Beta oscillations accompany cue utilization. Neuron. 2012;73:523–536. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra AM, Ellens DJ, Schridde U, Motelow JE, Purcaro MJ, DeSalvo MN, Enev M, Sanganahalli BG, Hyder F, Blumenfeld H. Where fMRI and electrophysiology agree to disagree: corticothalamic and striatal activity patterns in the WAG/Rij rat. J Neurosci. 2011;31:15053–15064. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0101-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panigrahi B, Martin KA, Li Y, Graves AR, Vollmer A, Olson L, Mensh BD, Karpova AY, Dudman JT. Dopamine Is Required for the Neural Representation and Control of Movement Vigor. Cell. 2015;162:1418–1430. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathelot JA, Strick PL. Subdivisions of primary motor cortex based on cortico-motoneuronal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:918–923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808362106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouiller EM, Liang FY, Moret V, Wiesendanger M. Trajectory of redirected corticospinal axons after unilateral lesion of the sensorimotor cortex in neonatal rat; a phaseolus vulgaris-leucoagglutinin (PHA-L) tracing study. Exp Neurol. 1991;114:53–65. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(91)90084-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeger-Armbruster S, Bosch-Bouju C, Little ST, Smither RA, Hughes SM, Hyland BI, Parr-Brownlie LC. Patterned, but not tonic, optogenetic stimulation in motor thalamus improves reaching in acute drug-induced parkinsonian rats. J Neurosci. 2015;35:1211–1216. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3277-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutzky MW, Jordan LR, Bauman MJ, Miller LE. A new rodent behavioral paradigm for studying forelimb movement. J Neurosci Methods. 2010;192:228–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparta DR, Stamatakis AM, Phillips JL, Hovelsø N, van Zessen R, Stuber GD. Construction of implantable optical fibers for long-term optogenetic manipulation of neural circuits. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:12–23. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valverde F. The pyramidal tract in rodents. A study of its relations with the posterior column nuclei, dorsolateral reticular formation of the medulla oblongata, and cervical spinal cord. (Golgi and electron microscopic observations) Z Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat. 1966;71:298–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergara-Aragon P, Gonzalez CL, Whishaw IQ. A novel skilled-reaching impairment in paw supination on the “good” side of the hemi-Parkinson rat improved with rehabilitation. J Neurosci. 2003;23:579–586. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-02-00579.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voigts J, Siegle JH, Pritchett DL, Moore CI. The flexDrive: an ultra-light implant for optical control and highly parallel chronic recording of neuronal ensembles in freely moving mice. Front Syst Neurosci. 2013;7:8. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2013.00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whishaw IQ, O’Connor WT, Dunnett SB. The contributions of motor cortex, nigrostriatal dopamine and caudate-putamen to skilled forelimb use in the rat. Brain. 1986;109(Pt 5):805–843. doi: 10.1093/brain/109.5.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whishaw IQ, Pellis SM, Gorny BP, Pellis VC. The impairments in reaching and the movements of compensation in rats with motor cortex lesions: an endpoint, videorecording, and movement notation analysis. Behav Brain Res. 1991;42:77–91. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(05)80042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whishaw IQ, Suchowersky O, Davis L, Sarna J, Metz GA, Pellis SM. Impairment of pronation, supination, and body co-ordination in reach-to-grasp tasks in human Parkinson’s disease (PD) reveals homology to deficits in animal models. Behav Brain Res. 2002;133:165–176. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00479-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whishaw IQ, Whishaw P, Gorny B. The structure of skilled forelimb reaching in the rat: a movement rating scale. J Vis Exp. 2008 doi: 10.3791/816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whishaw IQ, Zeeb F, Erickson C, McDonald RJ. Neurotoxic lesions of the caudate-putamen on a reaching for food task in the rat: acute sensorimotor neglect and chronic qualitative motor impairment follow lateral lesions and improved success follows medial lesions. Neuroscience. 2007;146:86–97. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witten IB, Steinberg EE, Lee SY, Davidson TJ, Zalocusky KA, Brodsky M, Yizhar O, Cho SL, Gong S, Ramakrishnan C, Stuber GD, Tye KM, Janak PH, Deisseroth K. Recombinase-driver rat lines: tools, techniques, and optogenetic application to dopamine-mediated reinforcement. Neuron. 2011;72:721–733. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

LabVIEW software. This zip archive contains heavily commented versions of the custom software in LabVIEW 2014 for running the apparatus.

Parts list. This Excel spreadsheet provides a list of components and approximate prices.

Movie 1. Sample successful (score 1) reaching video. Video has been downsampled to 30 fps and 956 × 480 resolution.