Abstract

Selenium-containing quinone-based 1,2,3-triazoles were synthesized using click chemistry, the copper catalyzed azide-alkyne 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition, and evaluated against six types of cancer cell lines: HL-60 (human promyelocytic leukemia cells), HCT-116 (human colon carcinoma cells), PC3 (human prostate cells), SF295 (human glioblastoma cells), MDA-MB-435 (melanoma cells) and OVCAR-8 (human ovarian carcinoma cells). Some compounds showed IC50 values < 0.3 μM. The cytotoxic potential of the quinones evaluated was also assayed using non-tumor cells, exemplified by peripheral blood mononuclear (PBMC), V79 and L929 cells. Mechanistic role for NAD(P)H:Quinone Oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) was also elucidated. These compounds could provide promising new lead derivatives for more potent anticancer drug development and delivery, and represent one of the most active classes of lapachones reported.

Keywords: β-Lapachone, Quinone, Click chemistry, Chalcogens, Selenium

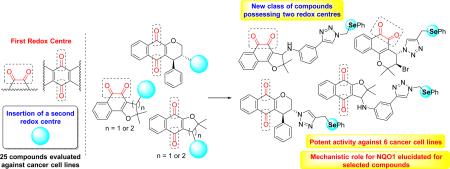

Graphical abstract

Selenium-containing quinones were designed and synthesized by click chemistry reaction and evaluated against several human cancer cell lines showing, in some cases, IC50 values below 0.3 μM.

1. Introduction

Development of diverse therapeutics is of paramount importance in the fight against different types of cancer [1,2]. Quinones are considered as privileged structures and are among the most important drugs used against cancer [3]. Although single-target drugs successfully inhibit or activate a specific target [4], drugs that are able to act simultaneously on diverse biological targets are more attractive in the design of new effective drugs [5]. In this context, quinoidal structures represent an essential multi-target class of compounds [6].

Naturally occurring naphthoquinones such as lapachol and β-lapachone (β-lap), isolated from the heartwood of Tabebuia, are among the most studied for their potential anti-tumor activity [7]. Docampo et al. [8] found significant activity for β-lap against Sarcoma 180 ascites tumor cells (S-180 cells) in vitro, and in mice bearing S-180 tumors. Although the antitumor activity of β-lap against Yoshida sarcoma and Walker 256 carcinoma cells in culture has been investigated [8,9], the exact mechanism of action was not known until recently [10].

β-Lapachone specifically destroys cancer cells with elevated endogenous levels of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) [11] regardless of p53, caspase, or cell cycle status [12]. While in clinical trials, β-lap (i.e., ARQ 501) has been inaccurately touted as a cell cycle checkpoint activator [13], the major determinant of cell death is through NQO1 expression [11,12a,14]. The drug is not a substrate for known multidrug resistance or drug pumps [15,16] and β-lap cell death is not affected by changes in cell cycle position, oncogenic drivers, or pro- or anti-apoptotic factors [11,12a]. Finally, the drug targets (i.e., is ‘bioactivated’ by) NQO1, a Phase II, carcinogen-inducible enzyme that is also induced by ionizing radiation (IR) in some cancer, but not normal, cells [17,18].

β-Lap's use as a chemotherapeutic agent is curtailed by its high hydrophobicity which causes methemoglobinemia in patients [19]. When mixed with the carrier hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin, the carrier itself can contribute to hemolysis [20]. Recently, Ohayon and coworkers [21] shed light on the hypothesis of β-lap being able to act nonreversibly for inhibition of deubiquitinases. These authors suggested that the therapeutic effect of β-lap could be also related to ubiquitin specific peptidase 2 (USP2) oxidation, which is likely a downstream effect of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation via NQO1 futile cycle metabolism of β-lap. NQO1 is the unique gene, that when deleted, leads to resistance to β-lap and other NQO1 bioactivatable drugs [22,23], strongly suggesting that most downstream effects cited by others are a result of upregulation of NQO1-derived ROS and Ca2+ intracellular increases, as well as rapid and dramatic losses in NAD+/ATP caused by PARP1 hyperactivation ending in NAD+-Keresis [24].

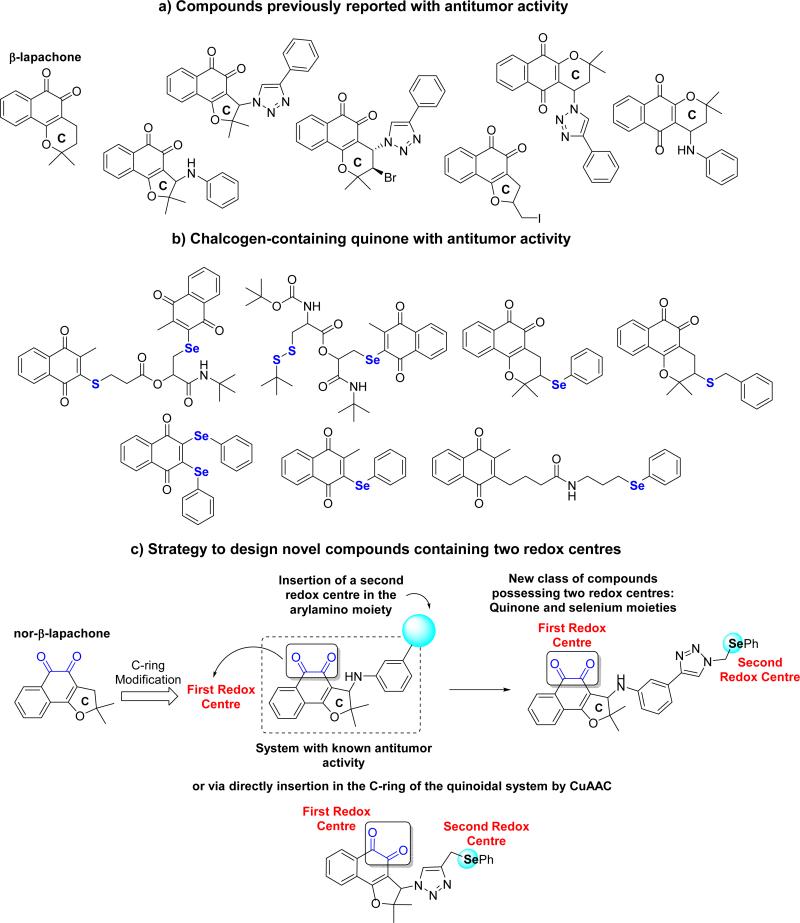

In the last few years, our group has been intensively dedicated to the synthesis and evaluation of lapachones against cancer cell lines [25,26]. We discovered a series of lapachones with modified C-rings (Scheme 1a) with potent activity against cancer lineages [27]. Lately, interest in preparing quinone-based triazoles has been stimulated by our discovery of bioactive compounds endowed with unique subunits in their chemical structures [28]. Recently, Perumal et al. [29] prepared amino-1,4-naphthoquinone-appended triazoles with antimycobacterial activity designed by the same molecular hybridization strategy [30]. β-Lapachone-based 1,2,3-triazoles possess significant activity with IC50 values below 2 μM for MDA-MB-435 cancer cells. These compounds promoted cell death by an apparent apoptotic cell death mechanism associated with significant ROS production [31]. The approach of inserting a triazole moiety in 1,4-naphthoquinones was also effective, since this unit is known as a potent pharmacophoric group [32]. Recently, 1,4-naphthoquinone-based 1,2,3-triazoles (Scheme 1a) were reported as having high activity in the range of 1.4 to 1.9 μM in HL-60 human promyelocytic leukemia cells [33].

Scheme 1.

Overview.

From another perspective, organoselenium compounds show antitumor, antimicrobial, anti-neurodegenerative and antiviral properties [34]. A series of selenoproteins are involved in important physiological processes [35]. Jacob and co-workers [36] demonstrated the potential antitumor activity of selenium-containing quinones (Scheme 1b) capable of mimicking the enzymatic activity of the human enzyme, glutathione peroxidase (GPx). GPx targets redox sensitive thiol proteins, while simultaneously generating reactive oxygen species at a critical threshold. Thus, these drugs act as ROS-users and ROS-enhancers to affect downsteam targets [37]. This action would complement the mechanism of action of β-lap, since death caused by this agent relies upon the hyperactivation of PARP1, which is stimulated by ROS (H2O2) [24].

In continuation of our program for obtaining novel potent antitumor naphthoquinones and based on recent findings reported by our group, we discovered potent chalcogen-containing β-lapachones (Scheme 1b) [38]. Here, we describe fifteen novel selenium-containing quinones and our strategy was based on inserting this pharmacophoric group, generating 1,2,3-triazole selenium-containing lapachones (Scheme 1c). Selected naphthoquinones with a structural framework with recognized activity against several types of cancer cell lines were used in the preparation of the new compounds. The structures were designed as multi-target ligands potentially giving rise to NQO1 cell death mechanisms of action.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1 Chemistry

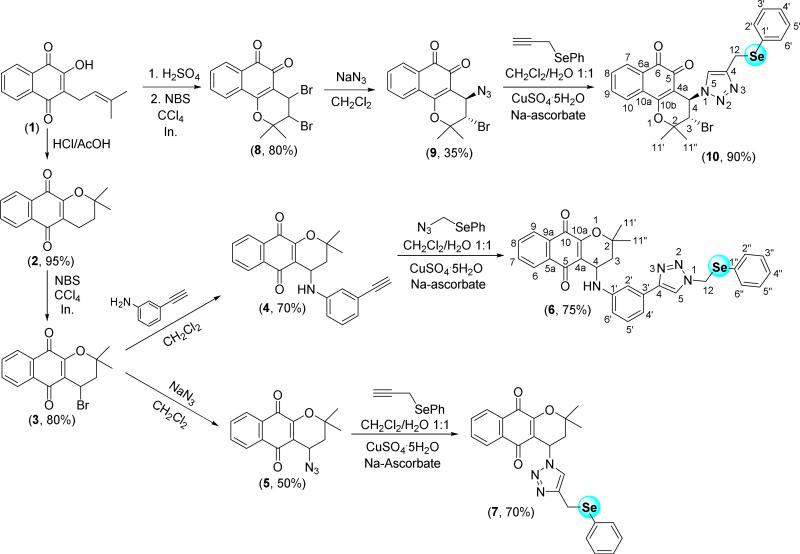

The first class of compounds prepared possessing two redox centres was selenium-containing dihydropyran naphthoquinones obtained from lapachol (1) (Scheme 2). α-Lapachone 2 was prepared by acid catalyzed cyclization from 1, and thentwo selenium-containing derivatives, 6 and 7, were synthesized from 2. Compound 6, was prepared in moderate yield (75%) by copper(I) catalyzed click reaction [39] between compound 4 and (azidomethyl)(phenyl)selane. The intermediate compound 4 was obtained by the reaction of 3-ethynylaniline and the bromo derivative 3. As previously reported [40], 4-azide-α-lapachone (5) was easily synthesized from the reaction of 3 with sodium azide in dichloromethane. The reaction of 5 and phenyl propargyl selenide affords selenium-containing α-lapachone 1,2,3-triazole 7. Finally, from the azide derivative 9, prepared as reported by us [41], β-lapachone-based 1,2,3-triazole 10 containing the chalcogen was obtained as a red solid. Compounds 3-10 are racemic. However, compounds 9 and 10 are single diastereomers, the relative stereochemistry is trans. The trans-stereochemistry was confirmed by comparison with previously reported data [41,47a].

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of selenium-containing β-lapachone and α-lapachone-based 1,2,3-triazoles.

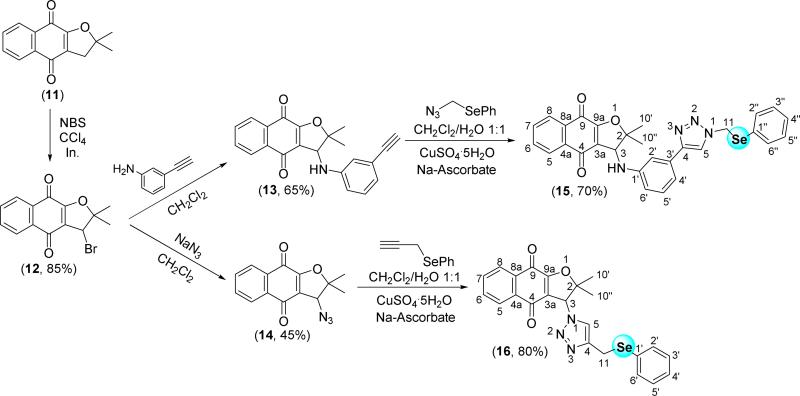

We began the synthesis of selenium-containing dihydrofuran naphthoquinones, the second class of compounds, initially by synthesizing nor-α-lapachone derivatives 15 and 16 (Scheme 3). Since the synthesis of arylamino substituted lapachones and azidoquinones are well established in our group [25,40,42], compounds 13 and 14 were prepared as shown in Scheme 3. Following click methodology, compounds 13 and 14 were reacted with selenium-containing azide and alkyne, respectively, to furnish the naphthoquinones 15 and 16 in 70% and 80% yield, respectively.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of selenium-containing nor-α-lapachone-based 1,2,3-triazoles.

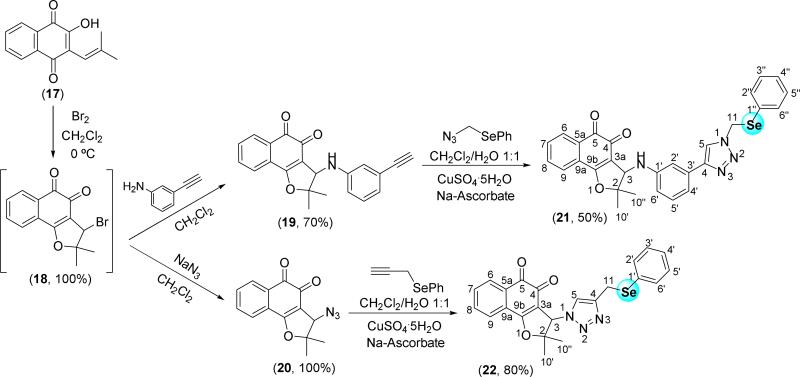

From nor-lapachol (17), the bromo intermediate 18 was synthesized following the methodology described by Pinto and co-workers (Scheme 4) [26,43]. Synthesis of various antitumor compounds from 18 was reported, as for instance, arylamino and alkoxy substituted nor-β-lapachone [26], lapachones in the presence of 1,2,3-triazole moiety [44] and hybrids with chalcones [45]. The unpublished arylamino substituted lapachone 19 bearing a terminal alkyne group was prepared based on the previously described compounds possessing activity against cancer cell lines [26]. The formation of the selenium-containing 1,2,3-triazole 21 from 19 herein described, allowed us to access the product designed with two redox centres. Using the same strategy discussed above, compound 22 was obtained from the azide derivative 20, previously reported by our group [46] (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of selenium-containing nor-β-lapachone-based 1,2,3-triazoles.

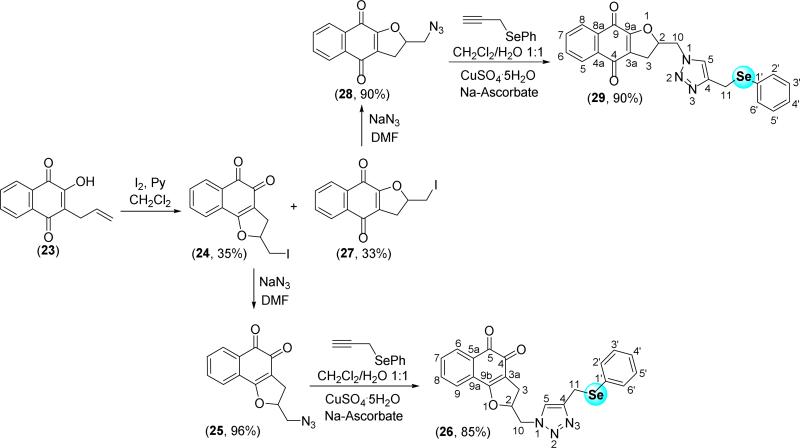

At this juncture, we described the synthesis of lapachones obtained from lapachol (1) and nor-lapachol (17), their inferior homologue. Recently, we reported the synthesis of a new class of naphthoquinone compounds, containing a pendant 1,2,3-triazole motif from C-allyl lawsone (23) [47]. The iodination of 23 affords compounds 24 and 27 in 68% yield and 1:1 ratio (Scheme 5), which were easily separated by column chromatography. With these compounds in hand, the respective azide derivatives, compunds 25 and 28, were synthesized by reaction of sodium azide in dimethylformamide. The respective selenium derivatives, compounds 26 and 29, were prepared by Cu-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of 26 and 29 from C-allyl-lawsone (23).

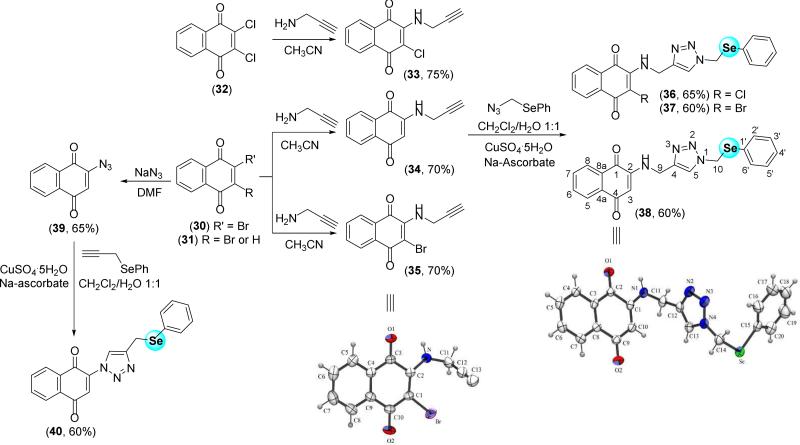

1,4-naphthoquinone coupled to selenium-containing 1,2,3-triazole was also a subject of our study. From compounds 33-35 and 39, the respective triazolic derivatives, compounds 36-38 and 40, were prepared using methodology discussed previously (Scheme 6). Suitable crystals of compounds 35 and 38 were obtained, and the structures were solved by crystallographic methods.

Scheme 6.

X-ray structures of compounds 35 and 38, and synthesis of selenium-containing para-quinone-based 1,2,3-triazoles.

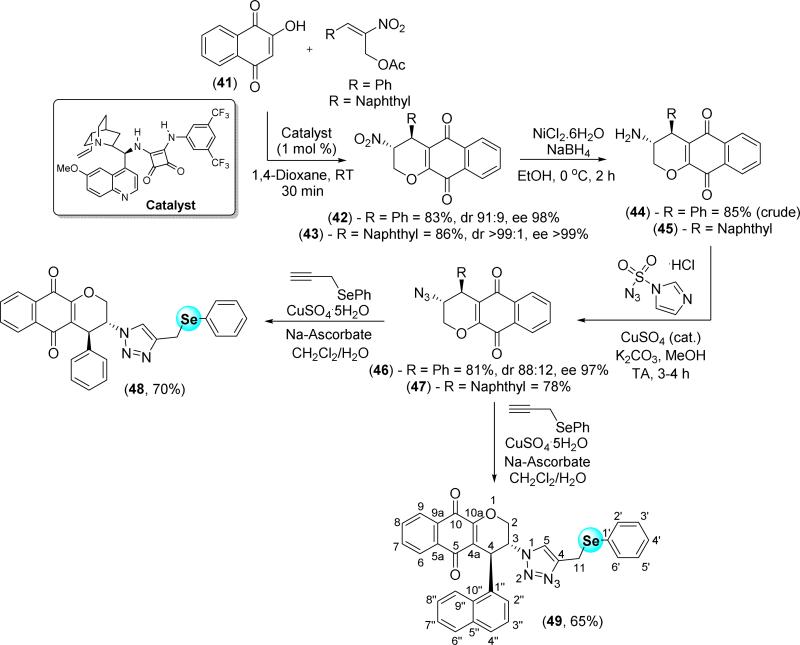

Recently, we reported a straightforward approach for the obtention of enantio-enriched α-lapachone derivatives [48]. In order to identify new enantio-enriched antitumor compounds, lawsone (41) was used to prepare the nitro-derivatives 42 and 43 via organocatalysis with a chiral squaramide (Scheme 7). The nitro group of the quinones was reduced to the amino group using NiCl2·6H2O/NaBH4 to afford aminoquinones 44 and 45. These compounds were used immediately after synthesis, due to their instability, for the preparation of azidoquinones 46 and 47, after a diazotransfer reaction. In the last step, we prepared the chalcogenium-containing 1,2,3-triazoles 48 and 49 for reaction with phenyl propargyl selenide by using a classical click procedure via catalysis with sodium ascorbate and copper(II) sulfate in a 1:1 mixture of dichloromethane and water.

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of enantio-enriched selenium-containing α-lapachone derivatives-based 1,2,3-triazoles.

Structures of the novel compounds 4, 6, 7, 10, 13, 15, 16, 19, 21, 22, 26, 29, 36, 37, 38, 40, 48 and 49 were determined by 1H and 13C NMR and 2D NMR spectra (COSY, HMBC and HSQC). Electrospray ionization mass spectra were also obtained to confirm compound identities.

2.2. Biological Studies

All of the selenium-containing quinone-based 1,2,3-triazoles described (Schemes 2-7) and their synthetic precursors were evaluated in vitro using the MTT assay against six cancer cell lines: HL-60 (human promyelocytic leukemia cells, NQO1−), HCT-116 (human colon carcinoma cells, NQO1), PC3 (human prostate cells, NQO1+), SF295 (human glioblastoma cells, NQO1+), MDA-MB-435 (melanoma cells, NQO1+) and OVCAR-8 (human ovarian carcinoma cells, NQO1+). β-Lapachone and doxorubicin were used as positive controls (Table 1). NQO1− normal cells, human peripheral blood mononucluear (PBMC), and murine fibroblast immortalized cell lines (V79 and L929) were used to evaluate the selectivity of the compounds. Mechanistic aspects of selected compounds were also studied for NQO1-dependency using the fairly specific NQO1 inhibitor, dicoumarol. As previously described [49], the compounds were classified according to their activity as highly active (IC50 < 2 μM), moderately active (2 μM < IC50 < 10 μM), or inactive (IC50 >10 μM).

Table 1.

Cytotoxic activity expressed by IC50 μM (95% CI) of compounds 4-7, 9-10, 13-16, 19-22, 25, 26, 28, 29, 36-38, 39, 40, 48 and 49 in cancer and normal cell lines after 72 h exposure, obtained by nonlinear regression for all cell lines from three independent experiments.

| Compd | HL-60 | HCT-116 | PC3 | SF295 | MDA-MB-435 | OVCAR-8 | PBMC | V79 | L929 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | >13.99 | >13.99 | >13.99 | >13.99 | >13.99 | >13.99 | >13.99 | >13.99 | >13.99 |

| 5 | 1.66 (1.09-2.22) |

2.96 (2.19-3.81) |

2.15 (1.94-2.36) |

2.05 (1.52-2.54) |

2.72 (2.33-3.28) |

1.48 (1.38-1.62) |

6.11 (5.65-6.88) |

3.67 (2.89-4.45) |

4.13 (3.28-4.87) |

| 6 | 2.00 (1.74-2.25) |

4.90 (4.62-5.76) |

2.60 (2.18-2.86) |

1.88 (1.47-2.26) |

1.49 (1.30-1.70) |

3.09 (1.98-4.85) |

4.16 (3.93-4.44) |

3.65 (3.21-3.81) |

3.30 (2.81-3.58) |

| 7 | 5.46 4.87-6.10) |

2.24 (1.71-2.53) |

3.89 (3.18-4.47) |

4.20 (3.93-4.89) |

3.85 (3.49-4.33) |

2.55 (2.05-2.95) |

4.45 (3.91-5.14) |

5.20 (4.62-5.43) |

5.46 (4.97-6.00) |

| 9 | 1.43 (1.32-1.54)a |

2.48 (2.32-2.68) |

1.68 (1.52-2.02) |

1.93 (1.76-2.12)a |

1.54 (1.46-1.62)a |

2.24 (1.99-2.70) |

3.58 (3.34-3.86)a |

2.40 (2.29-2.51) |

2.04 (1.74-2.43) |

| 10 | 1.22 (1.13-1.35) |

1.11 (0.84-1.26) |

1.90 (1.60-2.01) |

1.52 (1.44-1.67) |

1.31 (1.22-1.52) |

0.92 (0.88-1.22) |

1.87 (1.45-2.26) |

2.17 (2.03-2.31) |

1.74 (1.67-1.94) |

| 13 | 2.59 (2.30-2.94) |

4.60 (3.78-5.59) |

5.15 (4.63-5.80) |

>14.56 | 3.93 (3.44-4.40) |

7.13 (6.12-8.30) |

6.46 (5.50-7.10) |

6.06 (5.36-6.55) |

5.33 (5.15-5.53) |

| 14 | 2.23 (1.78-2.67) |

3.30 (2.90-3.68) |

4.09 (3.49-4.57) |

3.04 (2.64-3.82) |

2.52 (2.23-2.75) |

3.53 (3.34-3.75) |

3.16 (2.86-3.49) |

4.20 (3.82-4.90) |

3.68 (3.45-4.34) |

| 15 | 1.08 (0.86-1.49) |

1.28 (1.04-1.57) |

1.71 (1.44-2.03) |

1.08 (0.94-1.46) |

0.88 (0.76-1.06) |

0.68 (0.43-1.06) |

3.33 (2.94-3.56) |

3.78 (3.73-3.94) |

3.38 (3.06-3.65) |

| 16 | 1.59 (1.34-1.87) |

2.54 (1.55-2.88) |

2.95 (2.22-3.47) |

2.65 (2.39-3.34) |

2.15 (2.00-2.32) |

2.80 (2.45-3.34) |

3.23 (2.43-3.96) |

4.03 (3.29-4.63) |

3.77 (3.06-4.48) |

| 19 | 0.26 (0.20-0.35) |

1.48 (1.34-1.69) |

1.86 (1.69-2.39) |

2.59 (2.36-2.85) |

2.04 (1.78-2.18) |

2.53 (2.33-2.74) |

2.80 (2.30-3.35) |

2.16 (1.83-2.68) |

2.50 (2.33-2.77) |

| 20 | 3.08 1.48-6.46b |

0.89 (0.82-1.00) |

1.74 (1.22-2.15) |

3.23 2.38-4.38b |

1.19 1.08-1.34b |

1.34 (1.15-1.45) |

nd | 3.27 (2.97-3.53) |

2.67 (2.26-3.49) |

| 21 | 0.07 (0.02-0.16) |

0.14 (0.11-0.25) |

0.38 (0.29-0.67) |

0.34 (0.20-0.45) |

0.23 (0.16-0.38) |

0.20 (0.14-0.43) |

1.39 (1.12-1.53) |

1.13 (1.03-1.26) |

0.94 (0.86-1.15) |

| 22 | 1.29 (1.03-1.59) |

2.52 (2.00-2.88) |

2.43 (1.87-3.21) |

1.31 (1.10-1.59) |

1.06 (0.99-1.12) |

2.26 (1.66-3.06) |

1.76 (1.44-2.11) |

2.65 (1.76-3.16) |

2.30 (1.89-2.71) |

| 25 | 0.82 (0.55-1.45) |

0.63 (0.43-0.86) |

0.51 (0.24-0.59) |

0.39 (0.31-0.43) |

0.39 (0.27-0.59) |

0.35 (0.12-0.47) |

1.80 (1.57-2.15) |

0.82 (0.67-1.14) |

1.06 (0.94-1.18) |

| 26 | 0.13 (0.04-0.29) |

0.24 (0.18-0.31) |

0.24 (0.20-0.27) |

0.22 (0.20-0.24) |

0.29 (0.22-0.33) |

0.07 (0.02-0.13) |

1.31 (1.11-1.40) |

0.44 (0.22-0.60) |

0.62 (0.49-0.78) |

| 28 | 0.31 (0.20-0.43) |

0.24 (0.16-0.39) |

0.39 (0.16-0.63) |

0.35 (0.12-0.47) |

0.20 (0.04-0.27) |

0.35 (0.27-0.43) |

3.21 (2.58-4.27) |

2.47 (2.27-3.02) |

2.15 (1.88-2.70) |

| 29 | 0.82 (0.58-1.09) |

2.42 (1.80-3.26) |

1.40 (1.13-1.71) |

0.98 (0.69-1.44) |

0.62 (0.42-1.02) |

0.91 (0.75-1.11) |

2.80 (2.53-3.04) |

2.02 (1.64-2.44) |

2.15 (2.04-2.53) |

| 36 | 2.14 (1.99-2.49) |

3.25 (3.01-3.76) |

2.25 (1.92-2.40) |

2.93 (2.77-3.08) |

2.01 (1.64-2.47) |

2.58 (2.21-2.97) |

6.34 (5.70-6.66) |

2.51 (2.03-2.86) |

3.43 (3.01-3.78) |

| 37 | 1.11 (0.96-1.23) |

1.67 (1.43-2.05) |

2.29 (2.07-2.53) |

1.61 (1.43-1.89) |

1.43 (1.17-1.81) |

2.37 (1.87-2.49) |

3.86 (3.78-4.04) |

3.03 (2.87-3.40) |

3.30 (2.97-3.62) |

| 38 | 1.13 (0.78-1.20) |

1.72 (1.42-1.98) |

2.08 (1.84-2.41) |

0.97 (0.85-1.28) |

3.09 (2.72-3.76) |

1.89 (1.46-2.67) |

4.75 (4.44-5.06) |

3.99 (3.40-4.49) |

3.83 (3.76-3.97) |

| 39 | 2.21 (1.91-2.56) |

4.27 (4.22-4.52) |

2.16 (1.76-2.71) |

3.41 (3.11-3.62) |

2.36 (1.91-2.91) |

3.51 (3.16-4.27) |

8.64 (7.53-9.69) |

5.77 (4.62-6.73) |

5.17 (4.27-5.97) |

| 40 | >12.68 | >12.68 | >12.68 | >12.68 | >12.68 | >12.68 | >12.68 | >12.68 | >12.68 |

| 48 | 8.26 (8.00-9.17) |

7.22 (6.78-7.56) |

7.79 (7.46-8.07) |

5.58 (5.41-6.00) |

6.82 (6.23-7.16) |

7.90 (7.37-8.19) |

7.45 (7.24-7.71) |

6.74 (6.04-7.05) |

7.16 (6.91-7.50) |

| 49 | >8.67 | >8.67 | >8.67 | >8.67 | >8.67 | >8.67 | >8.67 | >8.67 | >8.67 |

| β-lap. | 1.57 1.11-1.69 |

0.87 0.74-0.95 |

1.65 1.40-1.94 |

0.95 0.70-1.03 |

0.25 0.16-0.33 |

1.16 0.97-1.25 |

>20.63 | - | - |

| DOXO | 0.06 0.02-0.09 |

0.15 0.09-0.21 |

0.02 0.02-0.04 |

0.51 0.43-0.58 |

0.96 0.87-1.10 |

0.41 0.36-0.49 |

0.55 0.41-0.58 |

0.28 0.21-0.36 |

0.23 0.15-0.30 |

The results showed most of compounds were highly active against all cancer cell lines evaluated, with IC50 values < 2 μM. In general terms, ortho-quinoidal compounds were more active than para-quinones. However, α-lapachone derivatives with potent antitumor activities were also identified.

Naphthopyranquinones 5-7, 9 and 10 presented high to moderate activities (IC50 in the range of 0.92 to 5.46 μM) and the non-active compound 4 was the exception of this class. For the selenium-containing quinones 6 and 10, the strategy of insertion of a second redox centre was a success and these derivatives were more active than their naphthoquinoidal precursors. Recently, we reported the synthesis and antitumor activities of several α-lapachone-based 1,2,3-triazoles [33]. It is important to highlight that the selenium-containing-based 1,2,3-triazole 7 displayed better activity than the compounds without the chalcogen.

Naphthofuranquinones were the second class of compounds evaluated. Para-naphthoquinones 15 and 16 were active against all cancer cell lines studied. In the last few years, we described nor-α-lapachone-based 1,2,3-triazoles obtained from lapachol (1) with IC50 values > 2 μM [33]. The strategy herein used to prepare compounds 15 and 16 with the presence of selenium improved the activities of nor-α-lapachone-based 1,2,3-triazoles, and these derivatives presented IC50 values ranging from 0.68-1.71 μM for 15, and 1.59-2.95 μM for 16.

Nor-β-lapachone and derivatives are among the most potent compounds from the lapachol group [25,26]. Recently, we demonstrated [50] the cytotoxicity and genetic toxicity of nor-β-lapachone in human lymphocytes, HL-60 leukaemia, and immortal normal murine V79 fibroblasts ranging from 2.5 and 5 μM. This compound failed to induce DNA damage in nontumor cells, but at the highest concentrations, it induced DNA single and double strand breaks and increased the frequency of chromosomal aberrations. The biological effects of nor-β-lapachone is related to its ability to deplete reduced glutathione (GSH), which leads to a GSSG-dominant pro-oxidant cellular status that contributes to its antiproliferative properties.

In this context, we described the potent antitumor activities of nor-β-lapachones [26,28]. Importantly, C-ring modified, nor-β-lapachone with arylamino groups were the most active lapachones described [26]. These compounds present significant antiproliferative effects in human myeloid leukaemia cell lines and induce oxidative DNA damage by ROS generation. They also somehow impair DNA repair activity, while triggering cell death, which may be apoptosis [51]. Compound 21 was designed based on prior experience with these bioactive lapachones. This compound contains the structural framework of the 3-arylamino-nor-β-lapachone derivatives reported before, but with a second redox chalcogen centre inserted by click chemistry reaction. This substance was highly active against all cancer cell lines evaluated, with IC50 values ranging from 0.07 to 0.38 μM. Moreover, compound 21 exhibited a high selectivity index (SI represented by the ratio of cytotoxicities between normal cells and different lines of cancer cells). For instance, PBMC vs HL-60 = 19.8. By comparison, doxorubicin, a standard clinically used drug against various types of cancers, contained a selectivity index value of 10.6. In the same way, compound 22 (IC50 in the range of 1.06 to 2.56 μM) was more active than nor-β-lapachone-based 1,2,3-triazole without the chalcogen atom. Herein, two important examples of successful preparation of potent antitumor quinones with two redox centres are reported. Compound 26, another norlapachone derivative obtained from C-allyl lawsone (23), also exhibited potent antitumor activity. This drug was considered highly active with IC50 values ranging from 0.07 to 0.29 μM, suggesting a highly active structure. Compounds 21 and 26 presented similar antitumor activities, showing the importance of the ortho-naphthofuranquinone moiety and the triazole selenium-containing group that potentially works together in the same two redox centre structures.

1,4-Naphthoquinones 36-40 were also evaluated and the compounds were considered moderately active with exception of compound 40, which was inactive against all cancer cells examined. The last compounds evaluated were asymmetric α-lapachone 48 and 49 and these substances were inactive. As recently described by us [45], the asymmetric α-lapachone derivatives are inactive against several cancer cell lines evaluated. Herein, we tried to improve their activities using the approach of insertion of the chalcogen in these quinones, but the strategy failed. Selectivity index for the most active compounds was summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Selectivity index for the most active compounds (only IC50 values < 2 μM for cancer cell lines were considered) [Selectivity index, represented by the ratio of cytotoxicities between normal cells and different lines of cancer cells].

| Compd | PBMC, V79 and L929 vs. HL-60 | PBMC, V79 and L929 vs. HCT-116 | PBMC, V79 and L929 vs. PC3 | PBMC, V79 and L929 vs. SF295 | PBMC, V79 and L929 vs. MDA-MB-435 | PBMC, V79 and L929 vs. OVCAR-8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 3.6, 2.2 and 2.4 | - | - | 2.9, 1.7 and 2.0 | - | 4.1, 2.4 and 2.7 |

| 6 | 2.0, 1.8 and 1.6 | - | - | 2.2, 1.9 and 1.7 | 2.8, 2.4 and 2.2 | - |

| 9 | 2.5, 1.6 and 1.4 | - | 2.1, 1.4 and 1.2 | 1.8, 1.2 and 1.0 | 2.3, 1.5 and 1.3 | - |

| 10 | 1.5, 1.7 and 1.4 | 1.6, 1.9 and 1.5 | 0.9, 1.1 and 0.9 | 1.2, 1.4 and 1.1 | 1.4, 1.6 and 1.3 | 2.0, 2.3 and 1.8 |

| 15 | 3.0, 3.5 and 3.1 | 2.6, 2.9 and 2.6 | 1.9, 2.2 and 1.9 | 3.0, 3.5 and 3.1 | 3.7, 4.2 and 3.8 | 4.8, 5.5 and 4.9 |

| 19 | 10.7, 8.3 and 9.6 | 1.89, 1.45 and 1.68 | 1.50, 1.1 and 1.3 | - | - | - |

| 21 | 19.8, 16.1 and 13.4 | 9.9, 8.0 and 6.7 | 3.6, 2.9 and 2.4 | 4.0, 3.3 and 2.7 | 6.0, 4.9 and 4.0 | 6.9, 5.6 and 4.7 |

| 22 | 1.3, 2.0 and 1.7 | - | - | 1.3, 2.0 and 1.75 | 1.6, 2.5 and 2.1 | - |

| 25 | 2.1, 1.0, and 1.2 | 2.8, 1.3 and 1.6 | 3.5, 1.6 and 2.0 | 4.6, 2.1 and 2.7 | 4.6, 2.1 and 2.7 | 5.1, 2.3 and 3.0 |

| 26 | 10.0, 3.3 and 4.7 | 5.4, 1.8 and 2.5 | 5.4, 1.8 and 2.5 | 5.9, 2 and 2.8 | 4.5, 1.5 and 2.1 | 18.7, 6.2 and 8.8 |

| 28 | 10.3, 7.9 and 6.9 | 13.3, 10.2 and 8.9 | 8.2, 6.3 and 5.5 | 9.1, 7.0 and 6.1 | 16.0, 12.3 and 10.7 | 9.1, 7.0 and 6.1 |

| 29 | 3.4, 2.4 and 2.6 | - | 2.0, 1.4 and 1.5 | 2.8, 2.0 and 2.1 | 4.5, 3.2 and 3.4 | 3.0, 2.2 and 2.3 |

| 37 | 3.4, 2.7 and 2.9 | 2.3, 1.8 and 1.9 | - | 2.3, 1.8 and 2.0 | 2.6, 2.1 and 2.3 | - |

| 38 | 4.2, 3.5 and 3.3 | 2.7, 2.3 and 2.2 | - | 4.8, 4.1 and 3.9 | - | - |

| Doxorubicin | 9.1, 4.6 and 3.8 | 3.6, 1.8 and 1.5 | 27.5, 14.0 and 11.5 | 1.0, 0.5 and 0.4 | 0.5, 0.2 and 0.2 | 1.3, 0.6 and 0.5 |

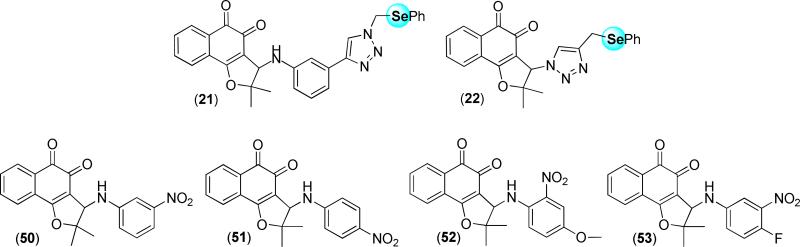

Previous studies from our laboratory revealed that compounds 50-53 (Figure 1) can be considered as prototypes possessing potent antitumor activities against diverse cancer cells [25,26]. To deepen our knowledge about the mechanism of action of compounds 50-53 and compare the previously reported structures with selenium-containing lapachone-based 1,2,3-triazoles, we examined their potential NQO1-dependent cytotoxicities using a set two-hour exposure, with or without the NQO1 inhibitor, dicoumarol. Such exposures take advantage of elevated NQO1 levels specifically in most solid cancers compared to associated normal tissue [11]. Within the class of selenium-containing quinones, we selected compounds 21 and 22 to evaluate their characteristics by an NQO1-dependent mechanism.

Figure 1.

Selected compounds for NQO1- and GPx-specific studies.

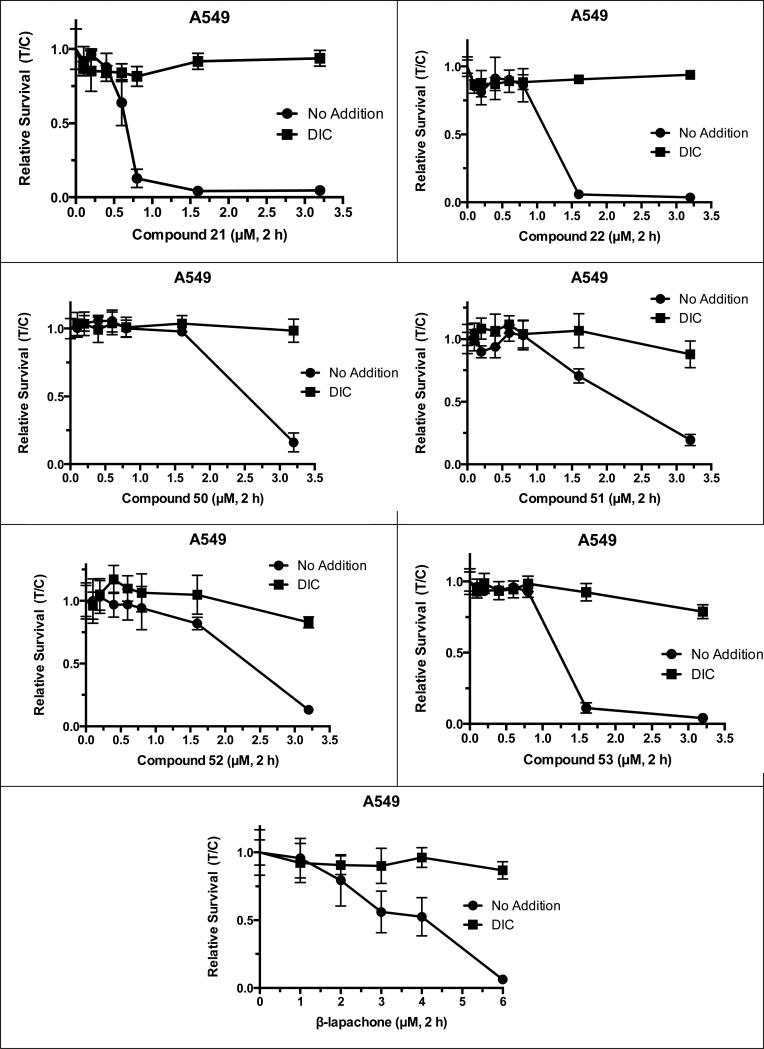

NQO1-dependency assessments

Within the drug concentration range tested, the compounds showed activity against human A549 non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma, an alveolar basal epithelial cell line. These cells express high levels of NQO1 (3000 + 300 enzymatic units). Cell death for many of the compounds tested were NQO1-specific, since addition of dicoumarol (DIC, an NQO1 inhibitor) spared their lethality. Based on the survival curves (Figure 2), previously reported arylamine substituted nor-β-lapachones have predicted IC50 as follows, compounds: 50 = 2.6 μM, 51 = 1.8 μM, 52 = 2.4 μM and 53 = 1.3 μM. Compound 53 showed the most dramatic lethality within a narrow therapeutic window, going from 93% viability at 0.8 μM to 11% viability at 1.6 μM. Overall, compounds 50-53 were NQO1-specific drugs exhibiting similar or lower IC50 values than β-lapachone. Compounds 21 and 22, selenium-containing quinones, with IC50 values = 0.64 and 1.2 μM, respectively, were the most active of this series and were NQO1-dependent (Table 3). They showed tremendous therapeutic windows using DIC treatment as a surrogate for responses to NQO1- cells, such as that found for nearly all human normal tissue [12a]. These responses are indicative of NQO1-dependent futile redox cycling of these drugs that create massive ROS, specifically H2O2, that ultimately cause PARP1 hyperactivation and programmed necrosis [23,24,52].

Figure 2.

Compounds 21, 22, 50-53 and β-lapachone evaluated for NQO1-dependence.

Table 3.

NQO1-dependent lethal responses of various compounds. IC50 values are reported for cells exposed for two hours in the absence or presence of dicoumarol (DIC).

| Compound | Activity | NQO1 Specific | IC50 (μM) | IC50 (μM) + DIC | DIC protection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | Yes | Yes | 0.64 | >3.2 | Yes |

| 22 | Yes | Yes | 1.2 | >3.2 | Yes |

| 50 | Yes | Yes | 2.6 | >3.2 | Yes |

| 51 | Yes | Yes | 1.8 | >3.2 | Yes |

| 52 | Yes | Yes | 2.4 | >3.2 | Yes |

| 53 | Yes | Yes | 1.3 | >3.2 | Yes |

| β-lapachone | Yes | Yes | 3.4 | >10 | Yes |

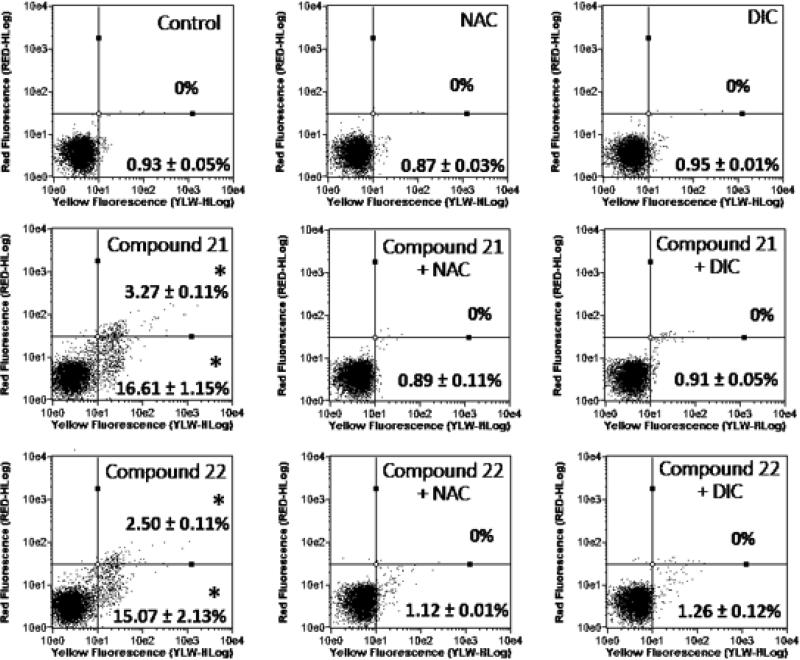

The externalization of phosphatidylserine is considered an important marker in the apoptotic process. After treatments, selected compounds 21 and 22 induced a significant increase on populations of PC3 cells with phosphatidylserine expressed on the cell surface (Figure 3). On the other hand, phosphatidylserine externalization was not observed in cultures pre-treated with NAC before 21 and 22 exposure or co-treated with dicoumarol (Figure 3). Our data show that cytotoxic mechanisms of tested compounds may involve drug bioreduction by quinone reductase NQO1 as well emphasizing the ROS contribution on the cytotoxicity suggesting that tested compounds-induced apoptosis is associated with ROS production. Finally, corroborating these studies, we observed that a short exposure (1 h) to compound 21 led to the generation of intracellular ROS. In other hand, in cultures pre-exposed with NAC, compound 21 was not able to generate ROS, which may be explained due the antioxidant protection exercised by NAC (See Figure S1 in the Supporting Information).

Figure 3.

Effect on phosphatidylserine externalization after 6 h-treated PC3 with 5 μM of tested compounds. The phosphatidylserine externalization was determined by flow cytometry using AnnV-FITC (YLW-HLog) and PI (RED-HLog). Viable cells are plotted at lower left quadrant, cells in early and late apoptosis with phosphatidylserine externalized are plotted at lower right and upper right quadrants, respectively, and necrotic cells are plotted at upper left quadrant. *p < 0.05 compared to control by ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls test. Data are presented as mean values ± S.E.M. from three independent experiments in triplicate.

3. Conclusions

By using the strategy of conjoining two redox centres, a quinoidal moiety and the atom of selenium, we prepared and evaluated the activities of novel and diverse selenium-containing quinone-based 1,2,3-triazole compounds against cancer versus normal cell lines. We assessed these drugs for lethality overall (Table 1) as well as for specific role of NQO1. In general, our approach was efficient and we identified compounds with IC50 values below 0.3 μM that were more potent than β-lapachone or doxorubicin, a standard clinically used agent against several types of cancers. We also studied the efficacy of two more active compounds 21 and 22 and found that these are specifically bioactivated by NQO1 with higher potency than nor-β-lapachone, previously published by us. Interestingly, we found that several of these drugs contained glutathione peroxidase (GPx)-like activities with selected selenium-containing nor-β-lapachone-based 1,2,3-triazoles being the most potent, and functionally acting on these two targets. Annexin V cytometry assay was also used to visualize the cell population in viable, early and late apoptosis stage for compounds 21 and 22. The cytotoxic mechanisms of 21 and 22 are intrinsically related with ROS contribution on the cytotoxicity suggesting that apoptosis is associated with ROS production. In order, we have described different classes of quinones, ortho- and para-quinoidal systems with potent antitumor activity. For example, compound 29 (para-quinone) has IC50 in the range of 0.62 to 2.42 μM in the cancer cell lines evaluated. Ortho-quinones, exemplified for compounds 10, 21, 22 and 26, presented IC50 among 0.07 to 2.52 μM. Finally, we have described potent antitumor naphthoquinone compounds that emerge as promising molecules for the therapeutic use of cancers overexpressing NQO1.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Chemistry

4.1.1. General procedures

Lawsone were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Lapachol (1) (2-hydroxy-3-(3’-methyl-2’-butenyl)-1,4-naphthoquinone) was extracted from the heartwood of Tabebuia sp. (Tecoma). C-allyl lawsone (23) was prepared from lawsone as previously reported [53]. A saturated aqueous sodium carbonate solution was added to the sawdust of ipe tree. Upon observing rapid formation of lapachol sodium salt, hydrochloric acid was added, allowing the precipitation of lapachol. Then, the solution was filtered and a yellow solid was obtained. This solid was purified by recrystallizations with hexane. All chemicals were obtained from commercial sources and used without further purification. Solvents were distilled and when required were dried by distillation according to standard procedure [54].

For the synthesis of (azidomethyl)(phenyl)selane (PhSeCH2N3): Initially (chloromethyl)(phenyl)selane was prepared by the reaction of a solution of diphenyl diselenide (3.0 mmol) in THF (6.0 mL) with NaBH4 (2 eq.) in EtOH (6.0 mL) and CH2Cl2 (30 mL). The mixture was kept under reflux in inert atmosphere and stirred for 12 h. After this period and subsequently extraction with H2O, the organic phase were combined, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated under vacuum. The residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel using hexane as the eluent [55]. To a solution of (chloromethyl)(phenyl)selane (PhSeCH2Cl) (3.0 mmol) in CH3CN (5.0 mL), sodium azide (4.5 mmol) and 18-crown-6 (0.60 mmol) were added at room temperature. Then the reaction mixture was stirred for 48 h under nitrogen atmosphere. After this time, 30 mL of H2O was added and the organic phase was extracted with CH2Cl2. The organic layers were combined, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated under vacuum. The residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel using hexane as the eluent. The product was obtained in 90% yield [56].

For the synthesis of phenyl propargyl selenide: To a solution of diphenyl diselenide (1.0 mmol) in THF (8.0 mL) with NaBH4 (2 eq.) in EtOH (4 mL). The mixture was kept under agitation at temperatue of 0 °C under inert atmosphere and, then, propargyl bromide (2.0 mmol) in THF (4 mL) was added. After 10 minutes, 30 mL of H2O was added and the organic phase was extracted with ethyl acetate. The organic phases were combined, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated under vacuum. The residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel using hexane as the eluent. The product was obtained in 85% yield [57].

Melting points were obtained on a Thomas Hoover and are uncorrected. Column chromatography was performed on silica gel (SiliaFlash G60 UltraPure 60-200 μm, 60 Å). Infrared spectra were recorded on an FTIR Spectrometer IR Prestige-21-Shimadzu. 1H and 13C NMR were recorded at room temperature using a Bruker AVANCE DRX200 and DRX400 MHz, in the solvents indicated, with tetramethylsilane (TMS) as internal reference. Chemical shifts (δ) are given in parts per million (ppm) and coupling constants (J) in Hertz (Hz). The mass spectrometer was operated in the positive ion mode. A standard atmospheric pressure photoionization (APPI) source was used to generate the ions. The sample was injected using a constant flow (3 μL/min). The solvent was an acetonitrile/methanol mixture. The APPI-Q-TOF MS instrument was calibrated in the mass range of 50-3000 m/z using an internal calibration standard (low concentration tuning mix solution) supplied by Agilent Technologies. Data were processed employing Bruker Data Analysis software version 4.0. Compounds were named following IUPAC rules as applied by ChemBioDraw Ultra (version 12.0).

4.1.2. Procedures to prepare arylamino lapachones 4, 13 and 19

To prepare 4 and 13

Compounds 3 and 12 (1.0 mmol) were dissolved in 25 mL of CH2Cl2 and an excess of 3-ethynylaniline (117 mg, 1.2 mmol) was added. The mixture was left under stirring overnight, followed by the addition of 50 mL of water. The organic phase was extracted with CH2Cl2, washed with 10% HCl (3 × 50 mL), dried over sodium sulfate, and filtered. The solvent from the crude was evaporated under reduced pressure and it was purified by column chromatography on silica-gel, using eluents with an increasing polarity gradient mixture of hexane and ethyl acetate (9/1 to 7/3).

To prepare 19

To a solution of nor-lapachol (17) (228 mg, 1.0 mmol) in 25 mL of chloroform, 2 mL of bromine was added. The bromo intermediate 18 precipitated immediately as an orange solid. After removal of bromine, by adding dichloromethane and then removing the organic solvent with dissolved bromine by rotary evaporator, an excess of 3-ethynylaniline (117 mg, 1.2 mmol) was added in CH2Cl2 and the mixture was stirred overnight. The crude reaction mixture was poured into 50 mL of water. The organic phase was separated and washed with 10% HCl (3 × 50 mL), dried over sodium sulfate, filtered, and evaporated under reduced pressure. The product 19 was obtained after purification by column chromatography in silica-gel, eluted with an increasing polarity gradient mixture of hexane and ethyl acetate (9/1 to 7/3).

4.1.3. General procedures to prepare the azide derivatives

The previously published azido derivatives 5, 9, 14, 20, 25, 39, 46 were prepared as described in the literature [40-42,46-48]. Compound 28 (1.0 mmol) was prepared from 27 in the presence of sodium azide (120 mg, 1.85 mmol) in 2 mL of dimethylformamide (DMF). The mixture was stirred at room temperature until product formation was complete as determined by thin layer chromatography. After extraction with CH2Cl2, the residue was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. Compound 28 was obtained after purification by column chromatography on silica gel eluting with a gradient mixture of hexane:ethyl acetate with increasing polarity. The unpublished azide derivative 47 was prepared following the same procedure previously described [48].

4.1.4. General procedures for the preparation of 1,2,3-triazole derivatives

The azidoquinones (1.0 mmol) or quinone with terminal alkynes (1.0 mmol) were reacted with CuSO4·5H2O (0.04 mmol) and sodium ascorbate (0.11 mmol) and the phenyl propargyl selenide (195 mg, 1.0 mmol) or (azidomethyl)(phenyl)selane (212 mg, 1.0 mmol) in a mixture of CH2Cl2:H2O (12 mL, 1:1, v/v). The mixture was stirred at room temperature until product formation was complete as determined by thin layer chromatography. The aqueous phase was extracted with CH2Cl2, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel eluting with a gradient mixture of hexane:ethyl acetate with increasing polarity.

4.1.5. 4-((3-ethynylphenyl)amino)-2,2-dimethyl-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[g]chromene-5,10-dione (4)

Yield: 70%; mp 196-197 °C; Brown solid. 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.11-8.03 (m, 2H), 7.75-7.68 (m, 2H), 7.16 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.95-6.85 (m, 2H), 6.71 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 4.68 (t, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 3.03 (s, 1H), 2.27 (dd, J = 3.5 and 14.4 Hz, 1H), 2.02 (dd, J = 5.5 and 14.4 Hz, 1H), 1.54 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 50 MHz) δ 183.7, 180.0, 155.5, 146.3, 134.6, 133.3, 132.1, 131.0, 129.4, 126.5, 126.3, 123.0, 122.8, 118.4, 117.1, 115.2, 84.1, 79.2, 43.7, 37.4, 28.7, 26.3; HRMS (ES+) calculated for C23H20NO3 [M+H]+: 358.1443; found: 358.1488.

4.1.6. 2,2-dimethyl-4-((3-(1-((phenylselanyl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)phenyl)amino)-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[g]chromene-5,10-dione (6)

Yield: 75%; mp 101-102 °C; Red solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.11 (dd, J = 7.1 and 1.7 Hz, H9), 8.07 (dd, J = 7.1 and 1.6 Hz, H6), 7.72 (td, J = 7.1, 7.1 and 1.6 Hz, H8), 7.68 (td, J = 7.1, 7.1 and 1.7 Hz, H7), 7.62 (s, H5-triazole), 7.50 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, H2’’/6’’), 7.33-7.39 (m, H4’’), 7.26-7.28 (m, H2’), 7.28-7.33 (m, H3’’/5’’), 7.20-7.26 (m, H5’), 7.05 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, H4’), 6.69 (dd, J = 8.0 and 1.8 Hz, H6’), 5.71 (s, H12), 4.78 (dd, J = 5.6 and 3.4 Hz, H4), 2.32 (dd, J = 14.3 and 3.4 Hz, H3a or H3b), 2.06 (dd, J = 14.3 and 5.6 Hz, H3a or H3b), 1.55 (s, H11’ or H11’’), 1.54 (s, H11’ or H11’’); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 183.5 (C5), 180.0 (C10), 155.3 (C10a), 148.5 (C4-triazole), 147.4 (C1’), 134.8 (C2’’/6’’), 134.3 (C8), 133.1 (C7), 132.1 (C9a), 131.3 (C3’), 130.9 (C5a), 129.8 (C5’), 129.6 (C3’’/5’’), 129.0 (C4’’), 127.4 (C1’’), 126.4 (C9), 126.2 (C6), 119.4 (C5-triazole), 118.9 (C4a), 115.7 (C4’), 113.6 (C6’), 110.7 (C2’), 79.1 (C2), 44.8 (C12), 43.2 (C4), 37.6 (C3), 29.0 (C11’ or C11’’), 26.1 (C11’ or C11’’); HRMS (ES+) calculated for C30H27N4O3Se [M+H]+: 571.1248; found: 571.1234.

4.1.7. 2,2-dimethyl-4-(4-((phenylselanyl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[g]chromene-5,10-dione (7)

Yield: 70%; mp 168-169 °C; Yellow solid. 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.18-8.09 (m, 1H), 8.04-7.96 (m, 1H), 7.80-7.68 (m, 2H), 7.50-7.39 (m, 2H), 7.24-7.10 (m, 4H), 5.71 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 1H), 4.13 (s, 2H), 2.73 (dd, J = 5.5 and 14.4 Hz, 1H), 2.29 (dd, J = 6.3 and 14.4 Hz, 1H), 1.50 (s, 3H), 1.21 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 50 MHz) δ 182.7, 179.5, 156.3, 145.3, 134.7, 133.7, 131.8, 131.1, 129.7, 129.1, 127.5, 126.8, 126.6, 122.0, 115.0, 79.4, 49.6, 39.0, 27.0, 26.5, 20.8; HRMS (ES+) calculated for C24H21N3O3SeNa [M+Na]+: 502.0646; found: 502.0643.

4.1.8. 3-bromo-2,2-dimethyl-4-(4-((phenylselanyl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[h]chromene-5,6-dione (10)

Yield: 90%; mp 105-106 °C; Orange solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.11 (dd, J = 7.6 and 1.4 Hz, H7), 7.90 (dd, J = 7.6 and 1.2 Hz, H10), 7.73 (td, J = 7.6, 7.6 and 1.2 Hz, H8), 7.63 (td, J = 7.6, 7.6 and 1.4 Hz, H9), 7.48-7.52 (m, H2’/6’), 7.48 (s, H5-triazole), 7.22-7.25 (m, H3’/5’), 7.22-7.25 (m, H4’), 5.55 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, H4), 4.93 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, H3), 4.17 (d, J = 13.3 Hz, H12a), 4.13 (d, J = 13.3 Hz, H12b), 1.71 (s, H11’ or H11’’), 1.64 (s, H11’ or H11’’); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 177.8 (C6), 176.4 (C5), 162.7 (C10b), 144.5 (C4-triazole), 135.2 (C8), 134.1 (C2’/6’), 132.3 (C9), 130.6 (C10a), 130.5 (C6a), 129.4 (C1’), 129.2 (C7), 129.1 (C3’/5’), 127.6 (C4’), 125.3 (C10), 125.0 (C5-triazole), 110.3 (C4a), 83.4 (C2), 54.4 (C3), 58.9 (C4), 20.7 (C11’ or C11’’), 27.4 (C11’ or C11’’), 20.7 (C12); HRMS (ES+) calculated for C24H21BrN3O3Se [M+H]+: 557.9931; found: 557.9923.

4.1.9. 3-((3-ethynylphenyl)amino)-2,2-dimethyl-2,3-dihydronaphtho[2,3-b]furan-4,9-dione (13)

Yield: 65%; mp 165-167 °C; Brown solid. 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.14-8.04 (m, 2H), 7.78-7.66 (m, 2H), 7.15 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.74 (s, 1H), 6.62 (dd, J = 2.1 and 8.0 Hz, 1H), 4.87 (s, 1H), 3.03 (s, 1H), 2.27 (s, 1H), 1.65 (s, 3H), 1.54 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 50 MHz) δ 181.7, 178.7, 159.9, 146.8, 134.6, 133.2, 133.1, 131.5, 129.4, 126.5, 126.3, 123.0, 122.4, 122.1, 116.3, 114.0, 94.9, 83.9, 62.2, 29.5, 27.1, 21.5; HRMS (ES+) calculated for C22H17NO3Na [M+Na]+: 366.1106; found: 366.1257.

4.1.10. 2,2-dimethyl-3-((3-(1-((phenylselanyl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)phenyl)amino)-2,3-dihydronaphtho[2,3-b]furan-4,9-dione (15)

Yield: 70%; mp 120-122 °C; Red solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.10 (dd, J = 7.4 and 1.4 Hz, H8), 8.07 (dd, J = 7.4 and 1.6 Hz, H5), 7.73 (td, J = 7.4, 7.4 and 1.6 Hz, H7), 7.68 (td, J = 7.4, 7.4 and 1.4 Hz, H6), 7.60 (s, H5-triazole), 7.50 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, H2’’/6’’), 7.27-7.39 (m, H3’’/5’’), 7.27-7.39 (m, H4’’), 7.22 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, H5’), 7.20 (s, H2’), 7.04 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, H4’), 6.61 (dd, J = 7.8 and 1.8 Hz, H6’), 5.71 (s, H11), 4.96 (s, H3), 4.05 (sl, NH), 1.67 (s, H10’ or H10’’), 1.57 (s, H10’ or H10’’); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 181.8 (C4), 178.6 (C9), 159.8 (C9a), 148.3 (C4-triazole), 147.5 (C1’), 134.8 (C2’’/6’’), 134.5 (C7), 133.2 (C8a), 133.1 (C6), 131.9 (C3’), 131.6 (C4a), 129.9 (C5’), 129.6 (C3’’/5’’), 129.0 (C4’’), 127.4 (C1’’), 126.5 (C8), 126.2 (C5), 122.3 (C3a), 119.4 (C5-triazole), 115.9 (C4’), 113.1 (C6’), 110.5 (C2’), 95.5 (C2), 62.3 (C3), 44.7 (C11), 27.2 (C10’ or C10’’), 21.6 (C10’ or C10’’); HRMS (ES+) calculated for C29H25N4O3Se [M+H]+: 557.1092; found: 557.1101.

4.1.11. 2,2-dimethyl-3-(4-((phenylselanyl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-2,3-dihydronaphtho[2,3-b]furan-4,9-dione (16)

Yield: 80%; mp 172-174 °C; Yellow solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.18 (dd, J = 7.4 and 1.6 Hz, H8), 8.08 (dd, J = 7.4 and 1.6 Hz, H5), 7.80 (td, J = 7.4, 7.4 and 1.6 Hz, H7), 7.76 (td, J = 7.4, 7.4 and 1.6 Hz, H6), 7.40 (dd, J = 7.9 and 1.4 Hz, H2’/6’), 7.08-7.19 (m, H3’/5’), 7.08-7.19 (m, H4’), 6.98 (s, H5-triazole), 5.92 (s, H3), 4.14 (d, J = 13.5 Hz, H11), 4.09 (d, J = 13.5 Hz, H11), 1.67 (s, H10’ or H10’’), 1.02 (s, H10’ or H10’’); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 180.5 (C4), 177.8 (C9), 151.1 (C9a), 145.8 (C4-triazole), 134.9 (C7), 133.9 (C2’/6’), 133.6 (C6), 132.7 (C8a), 131.6 (C4a), 129.13 (C1’), 129.06 (C3’/5’), 127.5 (C4’), 126.8 (C8), 126.5 (C5), 121.2 (C5-triazole), 118.3 (C3a), 94.5 (C2), 67.3 (C3), 27.4 (C10’ or C10’’), 20.7 (C10’ or C10’’), 20.5 (C11); HRMS (ES+) calculated for C23H19N3O3SeNa [M+Na]+: 488.0489; found: 488.0486.

4.1.12. 3-((3-ethynylphenyl)amino)-2,2-dimethyl-2,3-dihydronaphtho[1,2-b]furan-4,5-dione (19)

Yield: 70%; mp 205-206 °C; Red solid. 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.10 (dd, J = 2.0 and 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.76-7.58 (m, 3H), 7.12 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.88 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.69 (s, 1H), 6.58 (dd, J = 2.0 and 8.0 Hz, 1H), 4.79 (s, 1H), 3.02 (s, 1H), 1.68 (s, 3H), 1.57 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 50 MHz) δ 175.4, 169.7, 147.1, 134.7, 132.7, 131.2, 129.6, 129.4, 128.6, 125.2, 122.9, 122.2, 116.1, 115.0, 114.1, 96.8, 84.1, 61.5, 27.4, 21.8; HRMS (ES+) calculated for C22H17NO3Na [M+Na]+: 366.1106; found: 366.1108.

4.1.13. 2,2-dimethyl-3-((3-(1-((phenylselanyl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)phenyl)amino)-2,3-dihydronaphtho[1,2-b]furan-4,5-dione (21)

Yield: 50%; mp 135-137 °C; Red solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.12 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, H6), 7.70 (td, J = 7.4, 7.4 and 1.1 Hz, H7), 7.74 (dd, J = 7.4 and 1.1 Hz, H9), 7.64 (td, J = 7.4, 7.4 and 1.6 Hz, H8), 7.59 (s, H5-triazole), 7.50 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, H2’’/6’’), 7.28-7.40 (m, H3’’/5’’), 7.28-7.40 (m, H4’’), 7.14 (s, H2’), 7.20 (dd, J = 8.1 and 7.7 Hz, H5’), 7.02 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, H4’), 6.56 (dd, J = 8.1 and 2.2 Hz, H6’), 5.51 (s, H11), 4.89 (s, H3), 3.70-4.37 (sl, NH), 1.60 (s, H10’ or H10’’), 1.17 (s, H10’ or H10’’); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 181.0 (C5), 175.4 (C4), 169.6 (C9b), 148.3 (C4-triazole), 147.8 (C1’), 134.8 (C2’’/6’’), 134.6 (C7), 132.5 (C8), 131.3 (C3’), 131.2 (C9a), 129.8 (C5’), 129.6 (C3’’/5’’), 129.5 (C6), 128.9 (C4’’), 127.5 (C5a), 127.4 (C1’’), 125.1 (C9), 119.5 (C5-triazole), 115.5 (C4’), 115.1 (C3a), 113.0 (C6’), 110.2 (C2’), 96.9 (C2), 61.6 (C3), 44.8 (C11), 27.5 (C10’ or C10’’), 21.8 (C10’ or C10’’); HRMS (ES+) calculated for C29H24N4O3SeNa [M+Na]+: 579.0911; found: 579.0890.

4.1.14. 2,2-dimethyl-3-(4-((phenylselanyl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-2,3-dihydronaphtho[1,2-b]furan-4,5-dione (22)

Yield: 80%; mp 186-188 °C; Yellow solid. 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.19 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, H6), 7.68-7.82 (m, H7), 7.68-7.82 (m, H8), 7.68-7.82 (m, H9), 7.41 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, H2’/6’), 7.08-7.21 (m, H3’/5’), 7.08-7.21 (m, H4’), 7.00 (s, H5-triazole), 5.86 (s, H3), 4.05-4.16 (m, H11), 1.70 (s, H10’ or H10’’), 1.05 (s, H10’ or H10’’); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 50 MHz) δ 180.0 (C5), 174.5 (C4), 171.1 (C9b), 145.5 (C4-triazole), 134.9 (C7), 134.0 (C2’/6’), 133.4 (C8), 131.4 (C9a), 129.9 (C6), 129.2 (C1’), 129.1 (C3’/5’), 127.5 (C4’), 126.6 (C5a), 125.6 (C9), 121.2 (C5-triazole), 111.2 (C3a), 95.9 (C2), 66.7 (C3), 27.6 (C10’ or C10’’), 20.9 (C10’ or C10’’), 20.6 (C11); HRMS (ES+) calculated for C23H19N3O3SeNa [M+Na]+: 488.0489; found: 488.0482.

4.1.15. 2-((4-((phenylselanyl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl)-2,3-dihydronaphtho[1,2-b]furan-4,5-dione (26)

Yield: 85%; mp 163-164 °C; Orange solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.00 (dd, J = 7.4 and 1.5 Hz, H6), 7.59 (td, J = 7.4, 7.4 and 1.4 Hz, H7), 7.53 (td, J = 7.4, 7.4 and 1.5 Hz, H8), 7.44 (dd, J = 7.4 and 1.1 Hz, H9), 7.33-7.41 (m, H2’/6’), 7.31 (s, H5-triazole), 7.13-7.18 (m, H3’/5’), 7.13-7.18 (m, H4’), 5.33-5.42 (m, H2), 4.55 (dd, J = 14.6 and 7.3 Hz, H10a), 4.64 (dd, J = 14.6 and 3.9 Hz, H10b), 4.11 (s, H11), 3.23 (dd, J = 15.8 and 10.2 Hz, H3a), 2.83 (dd, J = 15.8 and 7.0 Hz, H3b); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 180.4 (C5), 175.2 (C4), 186.6 (C9b), 146.4 (C4-triazole), 134.7 (C7), 132.9 (C2’/6’), 132.3 (C8), 130.6 (C9a), 129.8 (C6), 129.8 (C1’), 129.2 (C3’/5’), 127.5 (C4’), 126.9 (C5a), 124.4 (C9), 122.7 (C5-triazole), 114.7 (C3a), 84.3 (C2), 53.3 (C10), 29.6 (C3), 20.2 (C11); HRMS (ES+) calculated for C22H18N3O3Se [M+H]+: 452.0513; found: 452.0896.

4.1.16. 2-(azidomethyl)-2,3-dihydronaphtho[2,3-b]furan-4,9-dione (28)

Yield: 90%; mp 116-117 °C; Yellow solid. 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.06-7.94 (m, 2H), 7.71-7.57 (m, 2H), 5.23-5.09 (m, 1H), 3.75 (dd, J = 3.7 and 13.3 Hz, 1H), 3.56 (dd, J = 5.0 and 13.3 Hz, 1H), 3.26 (dd, J = 10.8 and 17.4 Hz, 1H), 3.02 (dd, J = 7.5 and 17.4 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 50 MHz) δ 181.8, 177.1, 159.4, 134.1, 133.0, 132.6, 131.2, 126.1, 125.8, 124.0, 83.6, 53.5, 30.0; HRMS (ES+) calculated for C13H10N3O3 [M+H]+: 256.0722; found: 256.0716.

4.1.17. 2-((4-((phenylselanyl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl)-2,3-dihydronaphtho[2,3-b]furan-4,9-dione (29)

Yield: 90%; mp 169-171 °C; Yellow solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.00 (dd, J = 7.4 and 1.5 Hz, H8), 7.93 (dd, J = 7.4 and 1.6 Hz, H5), 7.66 (td, J = 7.4, 7.4 and 1.6 Hz, H7), 7.62 (td, J = 7.4, 7.4 and 1.5 Hz, H6), 7.32-7.37 (m, H5-triazole), 7.32-7.37 (m, H2’/6’), 7.11-7.17 (m, H3’/5’), 7.11-7.17 (m, H4’), 5.23-5.32 (m, H2), 4.64 (dd, J = 14.7 and 3.9 Hz, H10b), 4.57 (dd, J = 14.7 and 5.6 Hz, H10a), 4.05 (s, H11), 3.26 (dd, J = 17.4 and 10.6 Hz, H3b), 2.95 (dd, J = 17.4 and 8.1 Hz, H3b); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 50 MHz) δ 181.6 (C4), 177.2 (C9), 159.0 (C9a), 146.4 (C4-triazole), 134.4 (C7), 133.1 (C2’/6’), 132.7 (C8a), 133.2 (C6), 131.3 (C4a), 129.7 (C1’), 129.1 (C3’/5’), 127.4 (C4’), 126.4 (C8), 126.2 (C5), 124.1 (C3a), 123.1 (C5-triazole), 83.0 (C2), 52.9 (C10), 30.1 (C3), 20.3 (C11); HRMS (ES+) calculated for C22H18N3O3Se [M+H]+: 452.0513; found: 452.0512.

4.1.18. 2-chloro-3-(((1-((phenylselanyl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)amino)-1,4-naphthoquinone (36)

Yield: 65%; mp 127-128 °C; Orange solid. 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.14 (dd, J = 1.2 and 7.5 Hz, 1H), 8.03 (dd, J = 1.2 and 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.97-7.57 (m, 2H), 7.51-7.40 (m, 3H), 7.33-7.23 (m, 3H), 6.49 (sl, 1H), 5.68 (s, 2H), 5.10 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 50 MHz) δ 180.0, 176.7, 144.8, 143.6, 134.8, 134.7, 132.5, 132.3, 129.7, 129.5, 129.0, 126.9, 126.8, 126.7, 121.8, 111.6, 43.6, 40.0; HRMS (ES+) calculated for C20H16ClN4O2Se [M+H]+: 459.0127; found: 459.0128.

4.1.19. 2-bromo-3-(((1-((phenylselanyl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)amino)-1,4-naphthoquinone (37)

Yield: 60%; mp 124-126 °C; Orange solid. 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.13 (dd, J = 1.2 and 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.01 (dd, J = 1.2 and 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.77-7.57 (m, 2H), 7.48 (s, 1H), 7.46-7.41 (m, 2H), 7.36-7.20 (m, 3H), 6.50 (sl, 1H), 5.68 (s, 2H), 5.11 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 50 MHz) δ 180.1, 176.7, 146.2, 145.0, 135.0, 132.8, 132.3, 130.0, 129.8, 129.3, 127.2, 127.1, 122.1, 44.6, 40.7; HRMS (ES+) calculated for C20H16BrN4O2Se [M+H]+: 502.9622; found: 502.9612.

4.1.20. 2-(((1-((phenylselanyl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)amino)-1,4-naphthoquinone (38)

Yield: 60%; mp 162-164 °C; Red solid. 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.10 (dd, J = 7.6 and 1.3 Hz, H8), 8.06 (dd, J = 7.6 and 1.3 Hz, H5), 7.74 (td, J = 7.6, 7.6 and 1.3 Hz, H6), 7.64 (td, J = 7.6, 7.6 and 1.3 Hz, H7), 7.46 (dd, J = 7.8 and 1.5 Hz, H2’/6’), 7.39 (s, H5-triazole), 7.27-7.35 (m, H3’/5’), 7.27-7.35 (m, H4’), 6.22-6.35 (m, NH), 5.77 (s, H3), 5.68 (s, H10), 4.45 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, H9); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 50 MHz) δ 183.0 (C1), 181.6 (C4), 147.4 (C4-triazole), 143.2 (C2), 134.82 (C2’/6’), 134.78 (C6), 133.4 (C4a), 132.2 (C7), 130.4 (C8a), 129.7 (C3’/5’), 129.1 (C4’), 127.0 (C1’), 126.3 (C5), 126.2 (C8), 121.7 (C5-triazole), 101.7 (C3), 44.7 (C10), 38.1 (C9); HRMS (ES+) calculated for C20H17N4O2Se [M+H]+: 425.0517; found: 425.0512.

4.1.21. 2-(4-((phenylselanyl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-1,4-naphthoquinone (40)

Yield: 60%; mp 117-120 °C; Brown solid. 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.36 (s, 1H), 8.24-8.12 (m, 2H), 7.88-7.79 (m, 2H), 7.72 (s, 1H), 7.59-7.48 (m, 2H), 7.29-7.26 (m, 2H), 4.25 (s, 2H), 1.6 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 50 MHz) δ 183.6, 179.1, 146.8, 139.1, 134.9, 134.2, 133.4, 131.3, 130.9, 129.3, 129.1, 127.6, 127.1, 126.4, 126.2, 123.8, 20.2; HRMS (ES+) calculated for C19H14N3O2Se [M+H]+: 396.0251; found: 396.0242.

4.1.22. (3R,4S)-3-azido-4-(naphthalen-1-yl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[g]chromene-5,10-dione (47)

Yield: 78%; mp 115-117 °C; Light yellow solid. 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.27 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 8.23-8.20 (m, 1H), 8.03-8.00 (m, 1H), 7.93 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.80 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.76-7.68 (m, 3H), 7.59 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.35 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 5.14 (dd, J = 2.3 and 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (dt, J = 12.5 and 2.3 Hz, 1H), 4.19 (d, J = 12.5 Hz, 1H), 4.13 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 183.2, 179.1, 155.7, 136.0, 134.6, 133.6, 132.3, 131.3, 130.6, 129.7, 129.0, 127.6, 126.8, 126.7, 126.5, 126.2, 125.4, 122.2, 119.7, 64.6, 56.9, 36.4; HRMS (ES+) calculated for C23H15N3O3Na [M+Na]+: 404.1006; found: 404.1007.

4.1.23. (3R,4S)-4-phenyl-3-(4-((phenylselanyl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[g]chromene-5,10-dione (48)

Yield: 70%; mp 187-188 °C; Yellow solid. 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.22-8.16 (m, 1H), 8.02-7.98 (m, 1H), 7.78-7.73 (m, 2H), 7.40-7.26 (m, 7H), 7.15 (s, 1H), 7.13-7.02 (m, 3H), 4.98-4.96 (m, 1H), 4.70-4.65 (m, 2H), 4.50-4.44 (m, 1H), 4.10 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 50 MHz) δ 182.3, 178.4, 154.6, 145.8, 140.0, 134.5, 133.5, 133.4, 131.7, 130.7, 129.2, 128.9, 128.0, 127.7, 127.4, 126.5, 120.3, 119.7, 64.6, 58.3, 40.7, 20.2; HRMS (ES+) calculated for C28H21N3O3SeH [M+H]+: 528.0826; found: 528.0821.

4.1.24. (3R,4S)-4-(naphthalen-1-yl)-3-(4-((phenylselanyl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[g]chromene-5,10-dione (49)

Yield: 65%; mp 185-188 °C; Yellow solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.41 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, H9’’), 8.12 (dd, J = 6.9 and 1.9 Hz, H9), 7.89 (dd, J = 6.8 and 2.0 Hz, H6), 7.84 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, H6’’), 7.72 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, H4’’), 7.64-7.70 (m, H7), 7.64-7.70 (m, H8), 7.62 (dd, J = 8.6 and 7.5 Hz, H8’’), 7.50 (dd, J = 8.1 and 7.5 Hz, H7’’), 7.31 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, H2’/6’), 7.25 (dd, J = 8.2 and 7.1 Hz, H3’’), 7.20 (s, H5-triazole), 7.06 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, H2’’), 7.00 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, H3’/5’), 6.92 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, H4’), 5.42 (s, H4), 5.00 (s, H3), 4.54 (d, J = 12.8 Hz, H2a), 4.36 (dl, J = 12.8 Hz, H2b), 4.04 (s, H11); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 182.2 (C5), 178.4 (C10), 155.0 (C10a), 145.9 (C4-triazole), 135.9 (C1’), 134.5 (C8), 134.3 (C5’’), 133.5 (C2’/6’), 133.6 (C7), 131.9 (C9a), 130.9 (C5a), 130.4 (C10’’), 129.3 (C1’), 129.2 (C6’’), 129.1 (C4’’), 128.9 (C3’/5’), 127.8 (C8’’), 127.5 (C4’), 126.7 (C6), 126.6 (C9), 126.5 (C7’’), 125.7 (C2’’), 124.9 (C3’’), 122.7 (C9’’), 120.3 (C5-triazole), 120.0 (C4a), 64.4 (C2), 56.4 (C3), 37.2 (C4), 20.3 (C11); HRMS (ES+) calculated for C32H24N3O3Se [M+H]+: 578.0983; found: 578.0982.

4.2. Crystallographic data

The structures of the compounds 35 and 38 were determined from X-ray diffraction on an Enraf-Nonius Kappa-CCD diffractometer (95 mm CCD camera on κ-goniostat) using graphite monochromated MoKα radiation (0.71073 Å), at room temperature. Data collections were carried out using the COLLECT software [58] up to 50° in 2θ. Final unit cell parameters were based on 6482 reflections for compound 35 and 10161 reflections for compound 38. Integration and scaling of the reflections, correction for Lorentz and polarization effects were performed with the HKL DENZO-SCALEPACK system of programs [59]. The structures were solved by direct methods with SHELXS-97 [60]. The models were refined by full-matrix least squares on F2 using SHELXL-97 [61]. The program ORTEP-3 [62]. was used for graphic representation and the program WINGX [63] to prepare materials for publication. All H atoms were located by geometric considerations placed (C–H = 0.93-0.97 Å; N-H = 0.86 Å) and refined as riding with Uiso(H) = 1.5Ueq(C-methyl) or 1.2Ueq(other). An Ortep-3 diagram of compounds 35 and 38 are shown in Scheme 6 and the main crystallographic data are listed as following:

For compound 35

Empirical formula: C13H7BrNO2; Formula weight: 289.11; Temperature: 293(2) K; Wavelength: 0.71073 Å; Crystal system: triclinic; Space group: P-1; Unit cell dimensions: a = 7.2940(3) Å; b = 7.9110(3) Å; c = 9.7940(4) Å; α= 77.133(2)°; β= 89.477(2)°; γ = 84.157(2)°; Volume: 548.03(4) Å3; Z: 2; Density (calculated): 1.75 Mg/m3; Absorption coefficient: 2.140 mm−1; F(000): 286; Crystal size: 0.32 × 0.22 × 0.10 mm3; Theta range for data collection: 3.5 to 27.5°; Index ranges: −9≤h≤9, −9≤k≤10, −12≤l≤12; Reflections collected: 8533; Independent reflections: 2498 [R(int) = 0.092]; Refinement method: Full-matrix least-squares on F2; Data / restraints / parameters: 2190 / 0 / 154; Goodness-of-fit on F2: 1.06; Final R indices [I>2sigma(I)]: R1 = 0.042, wR2 = 0.109; R indices (all data): R1 = 0.048, wR2 = 0.114.

For compound 38

Empirical formula: C20H16N4O2Se; Formula weight: 419.3; Temperature: 293(2) K; Wavelength: 0.71073 Å; Crystal system: monoclinic; Space group: C2/c Unit cell dimensions: a = 34.0429(8) Å; b = 4.7831(2) Å; c = 23.3921(7) Å; α = 90°; β = 111.3°; γ = 90° ; Volume: 3548.6(2) Å3; Z: 8; Density (calculated):1.57 Mg/m3; Absorption coefficient: 2.140 mm−1; F(000): 1680; Crystal size: 0.28 × 0.11 × 0.10 mm3; Theta range for data collection: 2.6 to 27.54°; Index ranges: −43≤h≤44, −5≤k≤6, −30≤l≤30; Reflections collected: 16701; Independent reflections: 4026 [R(int) = 0.063]; Refinement method: Full-matrix least-squares on F2; Data / restraints / parameters: 2822 / 0 / 244; Goodness-of-fit on F2: 1.12; Final R índices [I>2sigma(I)]: R1 = 0.047, wR2 = 0.128; R indices (all data): R1 = 0.073, wR2 = 0.144.

Crystallographic data for the structures were deposited in the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, with numbers CCDC 1063533 and 1063534.

4.3. Antitumor activity

Compounds were tested for antitumor activity in cell culture in vitro using several human cancer cell lines obtained from the National Cancer Institute, NCI (Bethesda, MD). The L929 cells (mouse fibroblast L cells NCTC clone 929) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA), MDCK cells were purchased from the Rio de Janeiro Cell Bank (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil), and the Chinese hamster lung fibroblasts (V79 cells) were kindly provided by Dr. JAP Henriques (UFRGS, Brazil). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from heparinized blood from healthy, non-smoker donors who had not taken any medication at least 15 days prior to sampling by a standard method of density-gradient centrifugation on Histopaque-1077 (Sigma Aldrich Co. - St. Louis, MO, USA). All cancer cell lines and PBMC were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium. The L929, MDCK and V79 cells were cultivated under standard conditions in DMEM with Earle's salts. All culture media were supplemented with 20% (PBMC) or 10% (cancer, L929, MDCK and V79 cells) fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C with 5% CO2. PBMC cultures were also supplemented with 2% phytohaemagglutinin. In cytotoxicity experiments, cells were plated in 96-well plates (0.1 × 106 cells/well for leukaemia cells, 0.7 × 105 cells/well for solid tumor as well V79, L929 and MDCK cells, and 1 × 106 cells/well for PBMC). All tested compounds were dissolved with DMSO. The final concentration of DMSO in the culture medium was kept constant (0.1%, v/v). Doxorubicin (0.001-1.10 μM) was used as the positive control, and negative control groups received the same amount of vehicle (DMSO). The cell viability was determined by reduction of the yellow dye 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazol)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) to a blue formazan product as described by Mosmann [64]. At the end of the incubation time (72 h), the plates were centrifuged and the medium was replaced by fresh medium (200 μL) containing 0.5 mg/mL MTT. Three hours later, the MTT formazan product was dissolved in DMSO (150 μL) and the absorbance was measured using a multiplate reader (Spectra Count, Packard, Ontario, Canada). Drug effect was quantified as the percentage of control absorbance of the reduced dye at 550 nm. All cell treatments were performed with three replicates. All cells were mycoplasma-free.

4.4. DNA Survival Assays

A549 cells were plated into a 48-well plate with 10,000 cells/well in 500 μL of DMEM containing 10% FBS. The cells were allowed to attach and grow overnight. A stock of 5 mM of compounds or 10 mM β-lapachone, and 5 mM dicoumarol were made for the experiment. The 8 drug concentrations (0-3.2 μM) were prepared separately in 15 mL conical tubes with 7 mL of media each. The untreated control is DMSO. The media was removed from each well and 500 μL of each drug concentration was added to 6 wells (to produce sextuplet replicates for each concentration). After aliquoting the drug-containing media, 40 μL of dicoumarol was added to each remaining 15 mL conical tube (there remains 4 mL left of each drug concentration) to give a final concentration of 50 μM dicoumarol. The media was removed from a 2nd 48-well plate and 500 μL of the remaining drug + DIC media was aliquoted/well. The plates were gently shaken to mix and placed in the incubator for 2 h. After 2 h, all media was aspirated from the wells and 1 mL of fresh media was aliquoted into each well. The plates were then left in the incubator for 7 days, or until there was 100% confluency for the untreated control. Once the control was confluent, the media was discarded and 500 μL/well of 1X PBS was added to wash the wells. The PBS was discarded and 250 μL of dH2O/well was added. The plates were then put in the −80 °C freezer overnight. The next day, the plates were thawed completely and 500 μL of Hoechst staining buffer (50 μL of Hoechst 33258 in 50 mL of 1X TNE buffer) was added to each well. The plates were incubated in the dark at RT for 2 h. After two hours, the plates were read on a PerkinElmer Victor X3 plate reader and the readings were plotted as the treated/control (T/C) ± SEM.

4.5. Annexin V/PI detection

The Annexin V cytometry assay was used to detect cell population in viable, early and late apoptosis stage as described by Cavalcanti and coworkers [65]. After short exposure time (6 h) with compounds 21 and 22 at 5 μM, PC3 cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) conjugated Annexin V (Guava Nexin kit, Guava Technologies, Inc., Hayward, CA, USA) and PI (necrotic-cell indicator), and then they were subjected to flow cytometry (Guava EasyCyte Mini). Cells undergoing early and late apoptosis were detected by the emission of the fluorescence from only FITC and, both FITC and PI, respectively. To determine whether ROS are involved with tested compounds-induced cytotoxicity, cultures were pre-exposed (24 h) to 5 mM N-acetylcysteine (NAC), a widely used thiol-containing antioxidant that is a precursor of GSH which protects against oxidative stress-induced cell death. Also, cultures were co-treated with dicoumarol (50 μM) in order to evaluate the role of NQO1 on compounds bioactivation. A total of 10,000 events was evaluated per experiment (n = 3) and cellular debris was omitted from analysis.

Supplementary Material

Research highlights.

Selenium-containing quinones were obtained with potent antitumor activity.

Click chemistry was used for the synthesis of selenium -containing quinones.

Mechanistic insights involving NQO1-target were studied.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by grants from the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), numbers: 480719/2012-8, PVE 401193/2014-4, 449348/2014-8, 474797/2013-9 and 454171/2014-5. We would also like to thank FAPEMIG (APQ-02478-14), FUNCAP, FAPESP, FAPESC, CAPES, INCT-catálise and also the Physics Institute of USP (São Carlos) for kindly allowing the use of the KappaCCD diffractometer. Finally, these studies were also supported by NIH/NCI grant# CA102792 to DAB.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supporting Information

1H and 13C NMR spectra for all the unpublished compounds and 2D NMR spectra (COSY, HMBC and HSQC) for compounds 6, 10, 15, 16, 21, 22, 26, 29, 38 and 49. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Ljungman M. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:2929. doi: 10.1021/cr900047g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cragg GM, Grothaus PG, Newman DJ. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:3012. doi: 10.1021/cr900019j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a Hillard EA, de Abreu FC, Ferreira DCM, Jaouen G, Goulart MOF, Amatore C. Chem. Commun. 2008;23:2612. doi: 10.1039/b718116g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wellington KW. RSC Adv. 2015;5:20309. [Google Scholar]; c Bannwitz S, Krane D, Vortherms S, Kalin T, Lindenschmidt C, Golpayegani NZ, Tentrop J, Prinz H, Müller K. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:6226. doi: 10.1021/jm500754d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu JJ, Pan W, Hu YJ, Wang YT. PLoS One. 2012;29:40262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dias KST, Viegas Júnior C. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2014;12:239. doi: 10.2174/1570159X1203140511153200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a Prati F, Bergamini C, Molina MT, Falchi F, Cavalli A, Kaiser M, Brun R, Fato R, Bolognesi ML. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:6422. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Prati F, Bartolini M, Simoni E, de Simone A, Pinto AV, Andrisano V, Bolognesi ML. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;23:6254. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.09.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Prati F, Uliassi E, Bolognesi ML. Med. Chem. Commun. 2014;5:853. [Google Scholar]

- 7.a Arnaudon M. Comptes Rendus Hebdomadares Des Sianes ‘L‘Acord. Des Science. 1858;46:1152. [Google Scholar]; b Thomson RH. Naturally Occurring Quinones. Academic Press; London, New York: 1971. [Google Scholar]; c Fiorito S, Epifano F, Bruyère C, Mathieu V, Kiss R, Genovese S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014;24:454. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Park EJ, Min KJ, Lee TJ, Yoo YH, Kim YS, Kwon TK. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1230. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Docampo R, Cruz FS, Boveris A, Muniz RP, Esquivel DM. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1979;28:723. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(79)90348-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schaffner-Sabba K, Schmidt-Ruppin KH, Wehrli W, Schuerch AR, Wasley JW. J. Med. Chem. 1984;27:990. doi: 10.1021/jm00374a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a Pink JJ, Planchon SM, Magliarino C, Varnes ME, Siegel D, Boothman D. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:5416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Pink JJ, Wuerzberger-Davis S, Tagliarino C, Planchon SM, Yang X, Froelich CJ, Boothman DA. Exp. Cell Res. 2000;255:144. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Planchon SM, Pink JJ, Tagliarino C, Bornmann WG, Varnes ME, Boothman DA. Exp. Cell Res. 2001;267:95. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bey EA, Bentle MS, Reinicke KE, Dong Y, Yang CR, Girard L, Minna J, Bornmann WG, Gao J, Boothman DA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:11832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702176104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a Bey EA, Wuerzberger-Davis SM, Pink JJ, Yang CR, Araki S, Reinicke KE, Bentle MS, Dong Y, Cataldo E, Criswell TL, Wagner MW, Li L, Gao J, Boothman DA. J. Cell Physiol. 2006;209:604. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Tagliarino C, Pink JJ, Dubyak GR, Nieminen AL, Boothman DA. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:19150. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100730200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Tagliarino C, Pink JJ, Reinicke KE, Simmers SM, Wuerzberger-Davis SM, Boothman DA. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2003;2:141. doi: 10.4161/cbt.2.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li CJ. J. Cell Physiol. 2006;209:695. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bentle MS, Reinicke KE, Dong Y, Bey EA, Boothman DA. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6936. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rekha GK, Sladek NE. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1997;40:215. doi: 10.1007/s002800050649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cunha-Filho MS, Landin M, Martinez-Pacheco R, Dacunha-Marinho B. Acta Crystallogr. C. 2006;62:473. doi: 10.1107/S0108270106021706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boothman DA, Meyers M, Fukunaga N, Lee SW. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:7200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi EK, Terai K, Ji IM, Kook YH, Park KH, Oh ET, Griffin RJ, Lim BU, Kim JS, Lee DS, Boothman DA, Loren M, Song CW, Park HJ. Neoplasia. 2007;9:634. doi: 10.1593/neo.07397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartner LP, Rosen L, Hensley M, Mendelson D, Staddon AP, Chow W, Kovalyov O, Ruka W, Skladowski K, Jagiello-Gruszfeld A, Byakhov M. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25:20521. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blanco E, Bey EA, Khemtong C, Yang S, Setti-Guthi J, Chen H, Kessinger CW, Carnevale KA, Bornmann WG, Boothman DA, Gao J. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3896. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohayon S, Refua M, Hendler A, Aharoni A, Brik A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:599. doi: 10.1002/anie.201408411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao L, Li LS, Spruell C, Xiao L, Chakrabarti G, Bey EA, Reinicke KE, Srougi MC, Moore Z, Dong Y, Vo P, Kabbani W, Yang C, Wang X, Fattah F, Morales JC, Motea EA, Bornmann WG, Yordy JS, Boothman DA. Antioxid Redox Sign. 2014;21:237. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang X, Dong Y, Bey EA, Kilgore JA, Bair JS, Li LS, Patel M, Parkinson EI, Wang Y, Williams NS, Gao J, Hergenrother PJ, Boothman DA. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3038. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore Z, Chakrabarti G, Luo X, Ali A, Hu Z, Fattah FJ, Vemireddy R, DeBerardinis RJ, Brekken RA, Boothman DA. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:1599. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.a da Silva Júnior EN, de Souza MCBV, Pinto AV, Pinto MCFR, Goulart MOF, Barros FWA, Pessoa C, Costa-Lotufo LV, Montenegro RC, de Moraes MO, Ferreira VF. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007;15:7035. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b da Silva Júnior EN, de Moura MABF, Pinto AV, Pinto MCFR, de Souza MCBV, Araújo AJ, Pessoa C, Costa-Lotufo LV, Montenegro RC, de Moraes MO, Ferreira VF, Goulart MOF. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2009;20:635. [Google Scholar]

- 26.da Silva Júnior EN, de Deus CF, Cavalcanti BC, Pessoa C, Costa-Lotufo LV, Montenegro RC, de Moraes MO, Pinto MCFR, de Simone CA, Ferreira VF, Goulart MOF, Andrade CKZ, Pinto AV. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:504. doi: 10.1021/jm900865m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Castro SL, Emery FS, da Silva Júnior EN. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013;69:678. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.da Cruz EHG, Carvalho PHPR, Corrêa JR, Silva DAC, Diogo EBT, de Souza Filho JD, Cavalcanti BC, Pessoa C, de Oliveira HCB, Guido BC, da Silva Filho DA, Neto BAD, da Silva Júnior EN. New J. Chem. 2014;38:2569. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bala BD, Muthusaravanan S, Choon TS, Ali MA, Perumal S. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014;85:737. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Viegas Júnior C, Danuello AC, Bolzani VS, Barreiro EJ, Fraga CAM. Curr. Med. Chem. 2007;14:1829. doi: 10.2174/092986707781058805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.da Silva Júnior EN, Cavalcanti BC, Guimarães TT, Pinto MCFR, Cabral IO, Pessoa C, Costa-Lotufo LV, de Moraes MO, de Andrade CKZ, dos Santos MR, de Simone CA, Goulart MOF, Pinto AV. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011;46:399. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.a Agalave SG, Maujan SR, Pore VS. Chem. Asian J. 2011;6:2696. doi: 10.1002/asia.201100432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Massarotti A, Aprile S, Mercalli V, Grosso ED, Grosa G, Sorba G, Tron G. ChemMedChem. 2014;9:2497. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201402233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.da Cruz EHG, Hussene CMB, Dias GG, Diogo EBT, de Melo IMM, Rodrigues BL, da Silva MG, Valença WO, Camara CA, de Oliveira RN, de Paiva YG, Goulart MOF, Cavalcanti BC, Pessoa C, da Silva Júnior EN. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014;22:1608. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nogueira CW, Zeni G, Rocha JBT. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:6255. doi: 10.1021/cr0406559.Braga AL, Rafique J. In: The chemistry of organic selenium and tellurium compounds. Rappoport Z, editor. Wiley & Sons, Ltd; Chichester: 2014. Shaaban S, Negm A, Sobh MA, Wessjohann LA. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015;97:190. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.05.002.Shaaban S, Gaffer HE, Alshahd M, Elmorsy SS. Int. J. Res. Dev. Pharm. L. Sci. 2015;4:1654.Shaaban S, Sasse F, Burkholz T, Jacob C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014;22:3610. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.05.019. Important chapters related to the use of Se-Modified antioxidants: Synthesis of biologically relevant small molecules containing selenium. Part A. Antioxidant compounds pg 989-1054; Synthesis of biologically relevant small molecules containing selenium. Part B. Anti-infective and anticancer compounds pg 1053-1118; Synthesis of biologically relevant small molecules containing selenium. Part C. Miscellaneous biological activities 1119-1174.

- 35.a Alberto EE, Nascimento V, Braga AL. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2010;21:2032. [Google Scholar]; b Santi CT, Scalera C, Piroddi M, Galli F. Curr. Chem. Bio. 2013;7:25. [Google Scholar]; c Iwaoka M, Arai K. Curr. Chem. Bio. 2013;7:2. [Google Scholar]; d Alberto EE, Tondo DW, Dambrowski D, Detty MR, Nome F, Braga AL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:138. doi: 10.1021/ja209570y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.a Shabaan S, Ba LA, Abbas M, Burkholz T, Denkert A, Gohr A, Wessjohann LA, Sasse F, Weber W, Jacob C. Chem. Commun. 2009;31:4702. doi: 10.1039/b823149d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Doering M, Ba LA, Lilienthal N, Nicco C, Scherer C, Abbas M, Zada AAP, Coriat R, Burkholz T, Wessjohann L, Diederich M, Batteux F, Herling M, Jacob C. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:6954. doi: 10.1021/jm100576z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Mecklenburg S, Shaaban S, Ba LA, Burkholz T, Schneider T, Diesel B, Kiemer AK, Röseler A, Becker K, Reichrath J, Stark A, Tilgen W, Abbas M, Wessjohann LA, Sasse F, Jacob C. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009;7:4753. doi: 10.1039/b907831b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shaaban S, Diestel R, Hinkelmann B, Muthukumar Y, Verma RP, Sasse F, Jacob C. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012;58:192. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vieira AA, Brandão IR, Valença WO, de Simone CA, Cavalcanti BC, Pessoa C, Carneiro TR, Braga AL, da Silva Júnior EN. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015;101:254. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.a Rostovtsev VV, Green GL, Fokin VV, Sharpless KB. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002;41:2596. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::AID-ANIE2596>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kolb HC, Finn MG, Sharpless KB. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001;40:2004. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::AID-ANIE2004>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guimarães TT, Pinto MCFR, Lanza JS, Melo MN, Monte-Neto RL, de Melo IMM, Diogo EBT, Ferreira VF, Camara CA, Valença WO, de Oliveira RN, Frézard F, da Silva Júnior EN. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013;63:523. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.da Silva Júnior EN, Guimarães TT, Menna-Barreto RFS, Pinto MCFR, de Simone CA, Pessoa C, Cavalcanti BC, Sabino JR, Andrade CKZ, Goulart MOF, de Castro SL, Pinto AV. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010;18:3224. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.da Silva Júnior EN, de Souza MCBV, Fernandes MC, Menna-Barreto RFS, Pinto MCFR, Lopes FA, de Simone CA, Andrade CKZ, Pinto AV, Ferreira VF, de Castro SL. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:5030. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pinto AV, Pinto MCFR, de Oliveira CGT. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 1982;54:107. [Google Scholar]

- 44.da Silva Júnior EN, Cavalcanti BC, Guimarães TT, Pinto MCFR, Cabral IO, Pessoa C, Costa-Lotufo LV, de Moraes MO, de Andrade CKZ, dos Santos MR, de Simone CA, Goulart MOF, Pinto AV. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011;46:399. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jardim GAM, Guimarães TT, Pinto MCFR, Cavalcanti BC, de Farias KM, Pessoa C, Gatto CC, Nair DK, Namboothiri INN, da Silva Júnior EN. Med. Chem. Commun. 2015;6:120. [Google Scholar]

- 46.da Silva Júnior EN, Menna-Barreto RFS, Pinto MCFR, Silva RSF, Teixeira DV, de Souza MCBV, de Simone CA, de Castro SL, Ferreira VF, Pinto AV. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2008;43:1774. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]