Abstract

Objective

To determine whether preschool-aged children with earlier bedtimes have a lower risk for adolescent obesity and whether this risk reduction is modified by maternal sensitivity.

Study design

Data from 977 of 1364 participants in the Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development were analyzed. Healthy singleton-births at 10 U.S. sites in 1991 were eligible for enrollment. In 1995-1996, mothers reported their preschool-aged (mean=4.7 years) child's typical weekday bedtime, and mother-child interaction was observed to assess maternal sensitivity. At a mean age of 15 years height and weight were measured and adolescent obesity defined as a sex-specific body-mass-index-for-age ≥95th percentile of the U.S. reference.

Results

One-quarter of preschool-aged children had early bedtimes (8PM or earlier), half had bedtimes after 8PM but by 9PM, and one-quarter had late bedtimes (after 9PM). Children's bedtimes were similar regardless of maternal sensitivity (P=0.2). The prevalence of adolescent obesity was 10%, 16%, and 23%, respectively, across early to late bedtime groups. The multivariable-adjusted relative risk (95% confidence interval) for adolescent obesity was 0.48 (0.29, 0.82) for preschoolers with early bedtimes compared with preschoolers with late bedtimes. This risk was not modified by maternal sensitivity (P=0.99).

Conclusions

Preschool-aged children with early weekday bedtimes were half as likely as children with late bedtimes to be obese as adolescents. Bedtimes are a modifiable routine that may help to prevent obesity.

Keywords: Sleep, parenting, longitudinal study, prospective, epidemiology, maternal sensitivity

The need to begin obesity prevention early, before children are overweight, is well-established,1 and healthcare providers play an important role.2 Poor sleep, especially short sleep duration, is one risk factor associated with increased risk for obesity.3-5 Numerous prospective studies have documented an association in children between short nighttime sleep duration and obesity.6-10 Bedtimes have a greater impact on children's sleep duration than do wake times,11,12 and are also the likely behavioral target of clinicians and parents. In a prospective study of adolescents, later bedtimes predicted increases in body mass index (BMI) in adulthood that were not explained by sleep duration.13 Later bedtimes for younger children (aged 3 to 8 years at baseline) were associated with higher BMI and risk for overweight 5 years later.11 Using data from a cohort with a longer follow-up period, we sought to extend the evidence for an association between young children's bedtimes and later obesity.

Although the routine of early bedtimes for young children may reduce the risk of later obesity, the emotional climate in which parents establish and maintain this routine may affect its impact.14 The combined effect of earlier bedtimes and maternal sensitivity has not been investigated. Our objectives are to determine: 1) whether preschool-aged children with earlier bedtimes have a lower risk of obesity in adolescence, and 2) whether this risk reduction is modified by the level of maternal sensitivity.

Methods

The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (SECCYD) was a prospective cohort study designed to examine the impact of non-maternal-care on children's developmental outcomes.15 Families were recruited from 24 hospitals in 9 U.S. states at their child's birth in 1991.15 Inclusion criteria were maternal age ≥18 years, English fluency, no plans for adoption, singleton and term (≥37 weeks' gestation) birth, and post-birth hospitalization ≤6 days.15 Each of 10 participating universities secured institutional review board approval for all SECCYD protocols. Mothers provided written consent. Our analyses include 977 children (72% of 1364 enrolled) who had height and weight information available during adolescence.

Height and weight were measured, without shoes and wearing only light clothing, in a laboratory setting using a standardized protocol; height was measured to the nearest 1/8 inch using a wall mounted stadiometer or measuring stick, and weight was measured to the nearest 4 ounces using a balance scale.16 We calculated BMI (kg/m2) and defined adolescent obesity as a sex-specific BMI-for-age ≥95th percentile of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) growth reference.17 Height and weight data were extracted from the 15-year assessment whenever possible, but for those missing anthropometric data at 15 years, we used height and weight measured at the oldest age between 12.0 and 15.9 years. Almost ⅔ of youth (62%) were measured at age 15.0–15.9 years, but 29% were 14.0–14.9 years, and 9% were 12.0–13.9 years.

During the phone follow-up to the 54-month home-visit, mothers were asked, “What time does your child go to bed on most weekday evenings?” The response was open-ended, but reported bedtimes were primarily on the whole, half, or quarter hour. We examined the distribution and created bedtime categories based on natural break-points and to facilitate application of our findings. The most frequently reported bedtimes were 8:00 p.m. (n=171), 8:30PM (n=194), and 9PM (n=235), but reported bedtimes ranged from 6:45 p.m. to 1:30 a.m.. Only 52 children had bedtimes before 8PM (≤7:00=13; 7:30=36; 7:45=3), but 220 had bedtimes after 9PM (9:15= 8; 9:30=109; between 9:31 and 10PM=62; >10PM=41). We defined a late bedtime as after 9PM and an early bedtime as at or before 8PM. We conducted sensitivity analyses to understand the impact of our bedtime categorization on our results; in these analyses we divided each bedtime category into an earlier and later segment (e.g., the early bedtime category was split into ‘before 8PM’ and ‘at 8PM’). These sensitivity analyses did not yield meaningful differences and are not presented.

Maternal sensitivity was coded from a standardized, videotaped, 15-20 minute, play-session conducted in a child development laboratory during the 54-month assessment. Without the child present, mothers were shown the contents of three boxes: 1) an Etch A Sketch® maze, 2) wooden blocks for building towers, and 3) six animal puppets. Mothers were asked to play with their child using the contents of each box in the following order: first have their child attempt the maze, then build as many towers as he/she could, and finally play with the puppets. Researchers explained that the maze and tower-building activities could be difficult for some children, but that mothers should let their child try each activity on his/her own as much as possible before helping as needed.18 Videotapes were coded at a central location by trained coders who were blind to other information about the family. Coders met regularly with an investigator who ensured that consistent rating-standards were maintained.18 Maternal sensitivity was computed as the sum of three 7-point ratings of observed maternal behavior toward the child: supportive presence, respect for autonomy, and hostility [reverse coded].18 Maternal sensitivity scores were skewed toward high values; we defined low maternal sensitivity as the lowest quartile (scores ≤15), consistent with previous reports.14

Mothers reported their own educational attainment, as well as their child's sex and racial-ethnic group at study enrollment. Children's birth weights were recorded from birth certificates. Mothers reported household size and income when the child was preschool-aged, and we calculated the household income-to-poverty ratio. When the children were 15-years-old, mothers self-reported their own current height and weight, which we used to assess maternal obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2).

Statistical analyses

We restricted our analyses to participants with information available on our outcome variable—adolescent obesity. In the resulting sample (n=977), there were missing data on four analytic variables: income-to-poverty ratio (n=65, 7%), bedtime (n=78, 8%), maternal sensitivity (n=82, 8%) and maternal obesity (n=89, 9%). These missing data were multiply imputed using fully conditional specification.19 Logistic regression and ordinal logistic regression were employed to impute, respectively, the binary and ordinal variables. Imputation models included all analytic variables as well additional variables chosen for their association with the outcome or predictors. Ten imputations were performed, and all analyses involving imputed variables were aggregated using multiple imputation combining rules to account for imputation uncertainty.20 We also performed a complete-case-analysis (n=810), and our conclusions were robust to this sensitivity test.

We used chi-square tests to assess how children in the analytic sample (n=977) differed from children who were excluded because they lacked information on adolescent BMI (n=387). Associations between adolescent obesity, late bedtime, and sociodemographic characteristics were assessed using logistic regression. We used log-binomial regression and Poisson regression with robust variance21 to estimate the relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence-intervals (CI) for adolescent obesity associated with bedtime at preschool-age. Bedtime was modeled as a categorical variable with the latest bedtime category as the reference group. We examined the interaction between maternal sensitivity (low or adequate) and bedtime category to assess whether maternal sensitivity modified the relationship between preschool bedtime and risk for adolescent obesity. Using this model with adjustment for adolescent age, sex, racial/ethnic group, birth weight, maternal education, and maternal obesity, we estimated the covariate-adjusted prevalence of adolescent obesity in each of the six bedtime by maternal sensitivity groups. There was no evidence of an interaction between bedtime and maternal sensitivity, and thus, for parsimony, we present the RR (95% CIs) for adolescent obesity omitting this interaction term. Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 (Cary, NC).

Results

Children excluded from the analytic sample were more likely to be male and have less-educated mothers, but did not significantly differ in birth weight, race/ethnicity, or household income-to-poverty ratio (results not shown). Table I provides the characteristics of the analytic sample. Sixteen percent (n=161) of the sample was obese in adolescence [mean (SD) age=14.9 (0.6) years].

Table 1. Characteristics of SECCYD participants in analytic sample and their prevalence of late bedtime at preschool-age (∼4.5 years) and obesity in adolescence.

| Characteristic | n (%) | Late bedtime at preschool-age (after 9PM), % | P valuea | Adolescent obesity,b % | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 977 (100) | 25 | 16 | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 492 (50) | 24 | 0.6 | 14 | 0.02 |

| Male | 485 (50) | 26 | 19 | ||

| Racial-ethnic group | |||||

| White | 788 (81) | 22 | 0.001 | 15 | 0.005 |

| Non-white | 189 (19) | 35 | 23 | ||

| Birth weight, grams | |||||

| 2000 – 2999 | 159 (16) | 30 | 0.1 | 15 | 0.03 |

| 3000 – 3999 | 673 (69) | 25 | 15 | ||

| ≥4000 | 145 (15) | 19 | 24 | ||

| Maternal education at child's birth | |||||

| Graduate degree | 153 (16) | 16 | 0.002 | 10 | <0.001 |

| Bachelor's degree | 219 (22) | 21 | 10 | ||

| Some college or associate degree | 324 (33) | 24 | 19 | ||

| High school degree or equivalent | 201 (21) | 32 | 20 | ||

| Less than high school degree | 80 (8) | 36 | 29 | ||

| Household income-to-poverty ratio at preschool-age | |||||

| ≥5.00 | 191 (21) | 23 | <0.001 | 8 | <0.001 |

| 3.00 – 4.99 | 242 (26) | 18 | 12 | ||

| 1.86 – 2.99 | 234 (26) | 22 | 17 | ||

| 1.00 – 1.85 | 138 (16) | 39 | 26 | ||

| <1.00 | 107 (12) | 31 | 27 | ||

| Maternal obesityc | |||||

| BMI < 30 kg/m2 | 658 (74) | 24 | 0.6 | 10 | <0.001 |

| BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | 230 (26) | 26 | 34 | ||

Data (n=977) from the Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (SECCYD). Children were born in 1991. Percentages may not total to 100% due to rounding and are calculated from multiply imputed data.

Data were missing for household income-to-poverty ratio (n=65); bedtime at preschool-age (n=78); maternal sensitivity at preschool-aged (n=82); maternal obesity (n=89).

P values from logistic regression models (accounting for imputation variance).

Sex-specific BMI-for-age ≥95th percentile of the CDC growth reference from height and weight measured at a mean (SD) age of 14.9 (0.6) years.

Maternal BMI based on maternal self-report of height and weight when youth was 15 years of age.

When children were preschool-aged [mean (SD) age=4.7 (0.09) years], approximately 25% had a bedtime of 8PM or earlier, 50% had bedtimes after 8PM but by 9PM (ie, 8:01 – 9:00PM), and 25% had a bedtime after 9PM (Table II). Children's bedtimes were similar regardless of maternal sensitivity (P=0.2) (Table II). Late bedtimes were not significantly associated with children's sex, birth weight, or maternal obesity. However, children who were of non-white race/ethnicity, born to less educated mothers, or living in lower-income households were significantly more likely to have a late bedtime at preschool-age (Table I). Adolescent obesity was related to all of the participant characteristics examined (Table I).

Table 2. Distribution of children's bedtimes by maternal sensitivity at preschool-age.

| Typical weekday bedtime at preschool-age | n (%)a | Maternal sensitivity at preschool-ageb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adequate | Low | ||

|

|

|

||

| n (%)a | n (%)a | ||

| At or before 8PM | 223 (25) | 168 (25) | 47 (23) |

| After 8PM but by 9PMc | 456 (50) | 352 (51) | 99 (48) |

| Later than 9PM | 220 (25) | 156 (23) | 59 (29) |

| Total | 977 (100) | 676 (100)a | 205 (100)a |

Data (n=977) from the Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (SECCYD). Children were born in 1991.

Information missing for 78 children for bedtime and 82 children for maternal sensitivity at preschool-age; a total of 96 children were missing bedtime and/or maternal sensitivity at preschool-age. Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding and are calculated from multiply imputed data.

Maternal sensitivity from observed and coded supportive presence, respect for autonomy, and hostility [reversed] during mother-child interaction in the laboratory when child was preschool-aged (mean=56 months). Lowest quartile (score≤15)=low sensitivity; upper three quartiles=adequate sensitivity.

This middle category includes children whose bedtime was at 9PM.

P value = 0.17 from 2 df F-test in logistic regression model (accounting for imputation variance) predicting maternal sensitivity from bedtime.

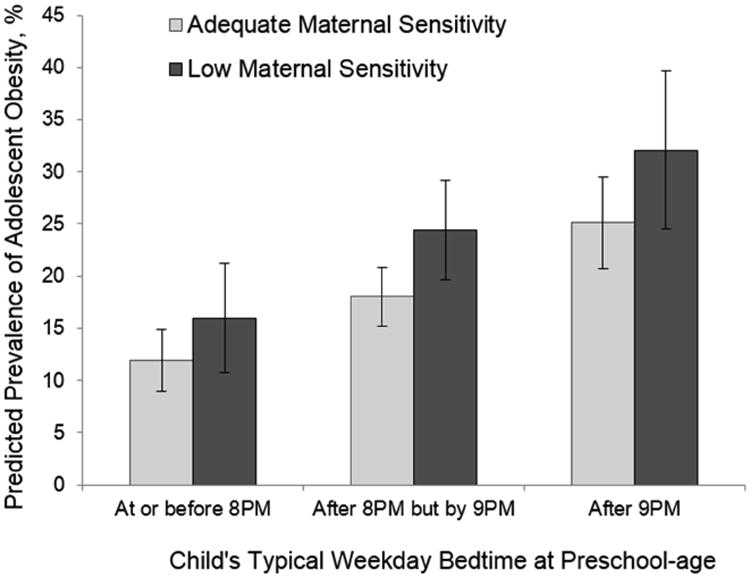

Earlier bedtimes at preschool-age were associated with lower risk for adolescent obesity. The unadjusted prevalence of adolescent obesity across early to late preschool bedtime categories was 10%, 16%, and 23%, respectively (Table III). With adjustment for adolescent age, sex, racial/ethnic group, birth weight, maternal education, maternal obesity, and maternal sensitivity, preschool-aged children with bedtimes at or before 8PM had an RRadj (95% CI) for adolescent obesity of 0.48 (0.29, 0.82) compared with preschool-aged children with bedtimes after 9PM. Bedtimes after 8PM but by 9PM were associated with an RRadj (95% CI) of 0.73 (0.51, 1.06) (Table III). A logistic model predicting adolescent obesity with all sociodemographic covariates did not yield a significant interaction between bedtime and maternal sensitivity at preschool-age (P=0.99). The predicted prevalence of adolescent obesity was lowest for early bedtimes and highest for later bedtimes, irrespective of maternal sensitivity (Figure).

Table 3. Relative risk for adolescent obesity in relation to child's typical weekday bedtime at preschool-age (∼4.5 years).

| Typical weekday bedtime at preschool-age | Prevalence of adolescent obesitya | Age-adjusted RR (95% CI)b | Fully-adjusted RR (95% CI)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| At or before 8PM | 10% | 0.44 (0.27, 0.70) | 0.48 (0.29, 0.82) |

| After 8PM but by 9PMd | 16% | 0.68 (0.49, 0.94) | 0.73 (0.51, 1.06) |

| Later than 9PM | 23% | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

Data (n=977) from the Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (SECCYD). Children were born in 1991. Multiple imputation used for missing data in 8% of cases.

Sex-specific BMI-for-age ≥95th percentile of the CDC growth reference. Prevalence is unadjusted for covariates.

Model adjusted for adolescent age. Model fit using log-binomial regression (SAS Proc Genmod, binary distribution, log link).

Model adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, birth weight, maternal education, maternal sensitivity at preschool-age, and maternal obesity. Model fit using Poisson regression with robust variance (SAS Proc Genmod, Poisson distribution, log link).

This middle category includes children whose bedtime was at 9PM. The age-adjusted RR (95% CI) for adolescent obesity of having an early bedtime (at or before 8PM) compared to a bedtime of after 8PM but by 9PM was 0.62 (0.42 0.97); the fully-adjusted RR (95% CI) was 0.64 (0.40, 1.04).

Figure.

Covariate-adjusted predicted prevalence of adolescent obesity by bedtime and maternal sensitivity at preschool-age (∼4.5 years) (SECCYD [n=977]). Children were born in 1991. Adolescent obesity (sex-specific BMI-for-age percentile≥95th) measured at mean=14.9 (SD=0.6) years. Error bars: ±1 SEM. Model adjusted for maternal education, maternal obesity, adolescent age, sex, race/ethnicity and birth weight (8% of cases include imputed data). Bedtime-by-maternal sensitivity interaction not statistically significant (P=0.99).

Discussion

Many well-designed prospective studies have established that short sleep duration in young children is associated with risk for obesity,3,7-10 but no studies have investigated the combined impact of maternal sensitivity and children's bedtimes on obesity.

The study that is most directly comparable with ours is an analysis of bedtime, wake time, and sleep duration for approximately 2000 children aged 3-12 years in the 1997 Child Development Supplement of the Panel Survey of Income Dynamics.11 In that study, more hours asleep, earlier bedtimes, and later wake times were associated with lower mean BMI and lower likelihood of overweight (BMI-for-age ≥85th percentile) assessed 5 years later.11 Bedtime was more strongly linked to subsequent BMI for younger (3-7.9 years) compared with older (8-12.9 years) children. This is consistent with our finding in SECCYD that preschool-aged children (∼4.5 years) with earlier bedtimes were less likely to be obese as adolescents. The follow-up period in our study is twice as long as that in prior studies focused on the relationship between children's bedtimes and risk for obesity.

A number of prospective studies have examined the impact of childhood sleep duration on adolescent or adult obesity outcomes.3,5,6 Of these, the Dunedin study of has the longest follow-up period.6 In the Dunedin study, each additional hour of sleep when children were 5-11 years-old, predicted a mean BMI approximately 1-unit lower at age 32 years and approximately a 30% reduction in the risk of obesity (BMI ≥30).6 In relation to risk for obesity, more is known about sleep duration than other aspects of sleep, such as bedtimes, but evidence from a prospective study of youth followed from adolescence to early adulthood suggests late bedtimes may be associated with weight gain independent of sleep duration.13

Earlier bedtimes, like other household routines,22,23 predict multiple better outcomes for children, aside from healthy weight. Regular and earlier bedtimes were associated with fewer parent- and teacher-reported behavioral difficulties in a large study of 3-7 year-old children in the UK.24 Similarly, a prospective cohort of infants born in Japan in 2001 found that irregular and late bedtimes at age 2 predicted difficulties at age 8 with behavior in the domains of attention and aggression.25 Inconsistent and late bedtimes may also contribute to sleep problems;26 an international survey of >10,000 mothers of young children (0-5 years) reported that regular bedtime routines were associated with reduced sleep latency, fewer nighttime awakenings, and greater sleep duration.27

It is common for preschool-aged children to have a regular bedtime and bedtime routine, but this may be less true for families of lower socioeconomic position.28-30 Consistent with this literature, we found that late bedtimes were more common for children living in poorer, less-educated, and minority racial-ethnic families. Bedtime is merely one of many interrelated facets of the family environment and parenting practices experienced by children. In the context of poverty, poor health, or adverse life events, families may struggle to maintain a consistent bedtime routine.31 Our results were robust to adjustment for maternal education and minority race/ethnicity, but variability in socioeconomic position was not as great in SECCYD as in the population of US children overall.

Our results should be interpreted in the context of the following limitations: First, observational studies like ours cannot establish causality, and it is possible that underlying biological mechanisms drive both a child's obesity risk and sleep requirements. However, randomized intervention studies have included recommendations about bedtime as part of multifaceted approaches to childhood obesity prevention.32 Results from such studies are promising and support a causal relationship between late bedtime and obesity, but follow-up has been short-term. Second, children in our study were born in 1991. We cannot be certain that associations would generalize to children born more recently. Third, measurement in our study was imperfect. Bedtime was recorded from mothers' phone-interview response to a single question about their child's typical weekday bedtime. It is unclear how mothers would respond for children with inconsistent bedtimes. Further, we do not know children's sleep duration, the quality of their sleep, or whether they have a different bedtime on weekends, and these aspects of sleep may also be important.33 Fourth, our results were robust to adjustment for multiple additional variables, but confounding due to unmeasured or poorly-measured variables cannot be excluded. Finally, we used multiple imputation to increase the size of our analytic sample. Compared with a complete-case analysis, multiple imputation may reduce bias but it also increases variance.

For young children, parents create the routines that allow children to obtain sufficient sleep to meet their physiologic needs. However, in establishing young children's bedtimes, like other household routines, parents must often make compromises as they face competing time demands. For example, some parents' work schedules do not allow them to arrive home early enough in the evening to spend time with their child and also maintain an early bedtime. This may push children's bedtimes later. At the same time, early bedtimes are required for adequate nighttime sleep if children must wake to accommodate their parents' work or siblings' school start times. Given the plausible mechanisms linking earlier bedtimes and healthy body weight, along with benefits to children's social and emotional functioning, pediatricians should encourage parents to establish a routine of early bedtimes for young children and support parents in their efforts to overcome the barriers they face in implementing this routine.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01DK088913 and R21DK104188). The Study of Early Child Care & Youth Development (SECCYD) Early Child Care Research Network was conducted by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development through a cooperative agreement that calls for scientific collaboration between grantees and the NICHD staff (<grant/agreement number>). The Ohio State University and Temple University have restricted data-use agreements to analyze the SECCYD data.

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CI

confidence interval

- ECLS-B

Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Birth Cohort

- NICHD SECCYD

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development Study of Early Child Care & Youth Development

- RR

relative risk

- SD

standard deviation

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dietz WH, Economos CD. Progress in the control of childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2015;135:e559–e561. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daniels SR, Hassink SG. The role of the pediatrician in primary prevention of obesity. Pediatrics. 2015;136:e275–292. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fatima Y, Doi SA, Mamun AA. Longitudinal impact of sleep on overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: a systematic review and bias-adjusted meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16:137–149. doi: 10.1111/obr.12245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel SR, Hu FB. Short sleep duration and weight gain: a systematic review. Obesity. 2008;16:643–653. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magee CA, Caputi P, Iverson DC. The longitudinal relationship between sleep duration and body mass index in children: a growth mixture modeling approach. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2013;34:165–173. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318289aa51.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Landhuis CE, Poulton R, Welch D, Hancox RJ. Childhood sleep time and long-term risk for obesity: a 32-year prospective birth cohort study. Pediatrics. 2008;122:955–960. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halal CS, Matijasevich A, Howe LD, Santos IS, Barros FC, Nunes ML. Short sleep duration in the first years of life and obesity/overweight at age 4 years: a birth cohort study. J Pediatr. 2016;168:99–103.e103. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.09.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taveras EM, Gillman MW, Pena MM, Redline S, Rifas-Shiman SL. Chronic sleep curtailment and adiposity. Pediatrics. 2014;133:1013–1022. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taveras EM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Oken E, Gunderson EP, Gillman MW. Short sleep duration in infancy and risk of childhood overweight. Arch Pediat Adol Med. 162:305–311. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.4.305. 08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bell JF, Zimmerman FJ. Shortened nighttime sleep duration in early life and subsequent childhood obesity. Arch Pediat Adol Med. 2010;164:840–845. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snell EK, Adam EK, Duncan GJ. Sleep and the body mass index and overweight status of children and adolescents. Child Dev. 2007;78:309–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDonald L, Wardle J, Llewellyn CH, van Jaarsveld CH, Fisher A. Predictors of shorter sleep in early childhood. Sleep medicine. 2014;15(5):536–540. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asarnow LD, McGlinchey E, Harvey AG. Evidence for a possible link between bedtime and change in body mass index. Sleep. 2014;38:1523–1527. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson SE, Gooze RA, Lemeshow S, Whitaker RC. Quality of early maternal-child relationship and risk of adolescent obesity. Pediatrics. 2012;129:132–140. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Child care and child development: the NICHD Study of Early Child Care. In: Friedman SL, Haywood HC, editors. Developmental Follow-up: Concepts, Domains, and Methods. Academic Press; New York: 1994. pp. 377–396. [Google Scholar]

- 16.NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development. Overview of Health and Physical Development Assessment (HPDA) Visit, Operations Manual - Phase IV. 2006;Chapter 85.1 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Mei Z, et al. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat. 2002;11:1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Early child care and mother-child interaction from 36 months through first grade. Infant Behav Dev. 2003;26:345–370. [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Buuren S. Flexible Imputation of Missing Data. CRC Press; Boca Raton, Fl: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. 2nd. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:199–200. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson SE, Whitaker RC. Household routines and obesity in US preschool-aged children. Pediatrics. 2010;125:420–428. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiese BH, Tomcho TJ, Douglas M, Josephs K, Poltrock S, Baker T. A review of 50 years of research on naturally occurring family routines and rituals: cause for celebration? J Fam Psychol. 2002;16:381–390. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.4.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelly Y, Kelly J, Sacker A. Changes in bedtime schedules and behavioral difficulties in 7 year old children. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e1184–e1193. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobayashi K, Yorifuji T, Yamakawa M, Oka M, Inoue S, Yoshinaga H, et al. Poor toddler-age sleep schedules predict school-age behavioral disorders in a longitudinal survey. Brain Dev. 2015;37:572–578. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buxton OM, Chang AM, Spilsbury JC, Bos T, Emsellem H, Knutson KL. Sleep in the modern family: protective family routines for child and adolescent sleep. Sleep health. 2015;1:15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mindell JA, Li AM, Sadeh A, Kwon R, Goh DY. Bedtime routines for young children: a dose-dependent association with sleep outcomes. Sleep. 2015;38:717–722. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adam EK, Snell EK, Pendry P. Sleep timing and quantity in ecological and family context: a nationally representative time-diary study. J Fam Psychol. 2007;21:4–19. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hale L, Berger LM, LeBourgeois MK, Brooks-Gunn J. Social and demographic predictors of preschoolers' bedtime routines. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2009;30:394–402. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181ba0e64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crabtree VM, Korhonen JB, Montgomery-Downs HE, Jones VF, O'Brien LM, Gozal D. Cultural influences on the bedtime behaviors of young children. Sleep Med. 2005;6:319–324. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El-Sheikh M, Buckhalt JA, Mize J, Acebo C. Marital conflict and disruption of children's sleep. Child Dev. 2006;77:31–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haines J, McDonald J, O'Brien A, Sherry B, Bottino CJ, Schmidt ME, et al. Healthy Habits, Happy Homes: randomized trial to improve household routines for obesity prevention among preschool aged children. JAMA Pediatrics. 2013;167:1072–1079. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller AL, Lumeng JC, LeBourgeois MK. Sleep patterns and obesity in childhood. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2015;22:41–47. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]