Abstract

BACKGROUND

Gastroschisis is a severe congenital anomaly the etiology of which is unknown. Research evidence supports attempted vaginal delivery for pregnancies complicated by gastroschisis in the absence of obstetric indications for cesarean delivery.

OBJECTIVE

The objectives of the study evaluating pregnancies complicated by gastroschisis were to: (i) determine the proportion of women undergoing planned cesarean versus attempted vaginal delivery; and (ii) provide up-to-date epidemiology on risk factors associated with this anomaly.

STUDY DESIGN

This population-based study of United States natality records from 2005–2013 evaluated pregnancies complicated by gastroschisis. Women were classified based on whether they attempted vaginal delivery or underwent a planned cesarean (n=24,836,777). Obstetrical, medical, and demographic characteristics were evaluated. Multivariable log-linear regression models were developed to determine factors associated with mode of delivery. Factors associated with the occurrence of the anomaly were also evaluated in log-linear models.

RESULTS

Of 5,985 pregnancies with gastroschisis, 63.5% (n=3,800) attempted vaginal delivery and 36.5% (n=2,185) underwent planned cesarean delivery. The rate of attempted vaginal delivery increased from 59.7% in 2005 to 68.8% in 2013. Earlier gestational age and Hispanic ethnicity were associated with lower rates of attempted vaginal delivery. Factors associated with the occurrence of gastroschisis included young age, smoking, high educational attainment, and being married. Protective factors included chronic hypertension, black race, and obesity. The incidence of gastroschisis was 3.1 per 10,000 pregnancies and did not increase during the study period.

CONCLUSION

Attempted vaginal delivery is becoming increasingly prevalent for women with a pregnancy complicated by gastroschisis. Recommendations from research literature findings may be diffusing into clinical practice. A significant proportion of women with this anomaly still deliver by planned cesarean suggesting further reduction of surgical delivery for this anomaly is possible.

INTRODUCTION

Gastroschisis is a severe congenital anomaly that involves a full-thickness defect of the abdominal wall through which intestines and other organs may herniate. The defect typically occurs on the right side of normal umbilical cord insertion,1 and in the majority of cases can be detected by midtrimester ultrasound.2 While risk factors for gastroschisis are well documented and include young maternal age, smoking, and infection, the etiology is unknown.3–6 Hypotheses for the cause of gastroschisis include failure of mesoderm formation in the body wall, rupture of amnion around the umbilical ring, and sequelae from involution of the right umbilical vein or disruption of the right vitelline artery.7 The defect requires major neonatal surgical intervention and is associated with significant health care costs, neonatal morbidity, and perinatal mortality.1,8

Routine obstetric management of gastroschisis includes increased fetal surveillance given higher risk for associated adverse obstetrical outcomes including fetal growth restriction and stillbirth.9 While optimal delivery timing is unclear,10 early term delivery may be indicated to reduce risk for bowel complications and perinatal death.11 An intervention that has not been shown to be beneficial is cesarean delivery. Data from earlier reports12–17 and a meta-analysis18 demonstrated no benefit for cesarean delivery; these findings are similar to those from later studies.19–21 Given the increased maternal morbidity with cesarean delivery, and lack of neonatal benefit, planned cesarean specifically for gastroschisis is not recommended.18

Given the evidence that cesarean delivery be reserved for obstetric indications, this analysis had two objectives: (i) to assess trends in planned vaginal delivery for pregnancies complicated by gastroschisis; and (ii) to provide up-to-date epidemiologic information on demographic, medical, and obstetric risk factors for this anomaly.

METHODS

The primary outcome of this population-based analysis was to determine whether women with pregnancies complicated by gastroschisis underwent planned cesarean delivery or attempted vaginal birth. The study utilized US vital statistics data based on the 2003 revision of the live birth certificates and the analysis was restricted to women who had live births from 2005–2013. Compared to the 1989 version, the 2003 birth certificate revision contains more detailed obstetric, medical, and demographic data.22 The updated format was incorporated gradually on a statewide basis. States using the revised format numbered 12 in 2005, 21 in 2006, 23 in 2007, 28 in 2009 (66% of all births), 33 in 2010 (76% of all births), 36 in 2011 (83% of all births), 38 in 2012 (86% of all births), and 41 in 2013 (90% of all births).23 The number of births available in this format increases annually given this uptake. Fetal demises were excluded because maternal data for these pregnancies is limited. The data set is provided by the National Vital Statistics System, a joint effort of the National Center for Health Statistics and states to provide access to statistical information from birth certificates. Birth certificates are required to be completed for all births and federal law mandates national collection and publication of births statistics. Prior analyses have addressed validity of these data.24–26 As US vital statistics data are both publically available and de-identified, this analysis was exempt from institutional review board approval.

Patients with potential indications for planned cesarean delivery other than gastroschisis were excluded from the primary analysis. Exclusion criteria included the following: (i) non-cephalic presentation, (ii) multiple gestation, (iii) prior cesarean delivery, and (iv) eclampsia. Only women that delivered between 28 and 41 weeks gestation were included in the primary analysis. Births from 2004 were excluded given that a relatively small proportion of national births are represented in the 2003-revised birth certificate for this year. Women were considered to have undergone an attempted vaginal delivery if they met one of the following criteria: (i) they underwent labor induction or augmentation; (ii) they had a successful spontaneous, forceps, or vaginal delivery; or (iii) they had a cesarean delivery in the setting of prolonged labor and/or fetal intolerance of labor. Patients were classified as undergoing planned cesarean delivery if they had a cesarean without induction or augmentation of labor or a diagnosis of fetal intolerance or prolonged labor.

Demographic, obstetrical, and medical factors possibly associated with attempted mode of delivery and available in the revised birth certificate format were chosen for inclusion in this analysis. Patient demographics included age (<20, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, and ≥35 years), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic other, and Hispanic), highest level of education (<9th grade through professional degree), marital status (married or unmarried), and year of delivery. Obstetrical factors included trimester of presentation to prenatal care and gestational age at delivery. The association between attempted mode of delivery and maternal clinical and demographic variables were compared using the χ2 test. To account for the effect of clinical, obstetric, and demographic factors on the probability of planned mode of delivery, we developed log linear regression models including factors that were clinically important and/or statistically significant on univariable analysis. Results are reported as a risk ratio with a 95% confidence interval (CI).

As a secondary analysis, we evaluated risk factors associated with the diagnosis of gastroschisis to provide an up-to-date analysis on the epidemiology of this anomaly. We compared pregnancies with and without gastroschisis and analyzed maternal obstetric, medical, and demographic factors. For this analysis the only inclusion criteria were live births between 2005 and 2013 and gestational age between 24 to <42 weeks (Table 3). Data on insurance status, body mass index kg/m2 (BMI), and sexually transmitted infections were included in this analysis, but are only available for the years 2011 through 2013. We used χ2 tests to compare the relationship between risk factors for gastroschisis and the outcome, and included statistically significant characteristics in an adjusted log linear regression model. A sensitivity analysis of the log linear model restricted to the years 2011–2013 to include the additional covariates only available during those years was performed. Additionally, the proportion of deliveries occurring from 34 to 42 weeks that are late preterm, early term, and full term are described by year.

Table 3.

Multivariable models of factors associated with gastroschisis

| 2005–2013 model | 2011–2013 model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Risk ratio | 95% CI | Risk ratio | 95% CI | |

| Parity | ||||

| Nulliparous | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Parous | 0.69 | (0.65–0.72) | 0.71 | (0.65–0.76) |

| Unknown | 1.08 | (0.83–1.41) | 1.23 | (0.80–1.87) |

| Age, years | ||||

| <20 | 3.46 | 3.19–3.75 | 2.86 | (2.52–3.24) |

| 20–24 | 2.23 | 2.08–2.39 | 2.07 | (1.87–2.29) |

| 25–29 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 30–34 | 0.51 | 0.46–0.57 | 0.53 | (0.46–0.62) |

| >34 | 0.38 | 0.33–0.44 | 0.41 | (0.33–0.51) |

| Highest level of education | ||||

| <9th grade | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 9th grade to 12 grade | 1.34 | (1.17–1.53) | 1.68 | (1.31–2.17) |

| High school graduate | 1.40 | (1.23–1.59) | 1.79 | (1.39–2.29) |

| Some college credit | 1.44 | (1.26–1.65) | 1.81 | (1.40–2.33) |

| Associate degree | 1.28 | (1.08–1.50) | 1.59 | (1.19–2.13) |

| BS degree | 0.92 | (0.78–1.08) | 1.10 | (0.82–1.47) |

| MS degree | 0.69 | (0.55–0.87) | 0.92 | (0.64–1.32) |

| Doctorate/professional | 0.51 | (0.32–0.82) | 0.46 | (0.22–0.97) |

| Year | ||||

| 2005 | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| 2006 | 0.93 | (0.82–1.06) | ||

| 2007 | 0.98 | (0.87–1.11) | ||

| 2008 | 1.02 | (0.90–1.15) | ||

| 2009 | 1.06 | (0.94–1.19) | ||

| 2010 | 1.03 | (0.92–1.16) | ||

| 2011 | 1.12 | (1.00–1.25) | 1.00 | Referent |

| 2012 | 1.14 | (1.02–1.28) | 1.02 | (0.94–1.11) |

| 2013 | 1.09 | (0.97–1.22) | 0.97 | (0.90–1.06) |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| Unmarried | 1.67 | (1.57–1.77) | ||

| Race | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.44 | (0.41–0.48) | 0.49 | (0.44–0.55) |

| Non-Hispanic other | 0.81 | (0.72–0.91) | 0.80 | (0.67–0.95) |

| Hispanic | 0.69 | (0.64–0.73) | 0.71 | (0.64–0.78) |

| Multiple gestation | ||||

| Singleton | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Multiple gestation | 1.01 | (0.86–1.17) | 0.95 | (0.75–1.21) |

| Pregestational diabetes | ||||

| Present | 0.73 | (0.50–1.07) | 1.17 | (0.72–1.89) |

| Absent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Unknown | 2.20 | (1.56–3.10) | 1.20 | (0.57–2.53) |

| Chronic hypertension | ||||

| Present | 0.61 | (0.44–0.84) | 0.99 | (0.66–1.48) |

| Absent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Smoking | ||||

| Present | 1.61 | (1.51–1.72) | 1.70 | (1.54–1.87) |

| Absent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Unknown | 1.05 | (0.98–1.13) | 0.97 | (0.83–1.13) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)¥ | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | N/A | N/A | 1.04 | (0.91–1.20) |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 0.70 | (0.65–0.77) | ||

| Obesity (30.0–34.9) | 0.49 | (0.43–0.56) | ||

| Obesity (35.0–39.9) | 0.38 | (0.31–0.47) | ||

| Obesity (≥40) | 0.26 | (0.19–0.36) | ||

| Unknown | 0.93 | (0.79–1.11) | ||

| Chlamydia during pregnancy¥ | ||||

| Present | N/A | N/A | 1.00 | Referent |

| Absent | 1.17 | (0.99–1.39) | ||

| Insurance status¥ | ||||

| Medicaid | N/A | N/A | 1.09 | (1.00–1.20) |

| Private | 1.00 | Referent | ||

| Self-pay | 0.73 | (0.58–0.93) | ||

| Other | 1.17 | (0.99–1.38) | ||

| Unknown | 1.13 | (0.85–1.52) | ||

Factors for which data is only available for years 2011–2013

A sensitivity analysis of births from 2009–2013 evaluating the rate of attempted labor including only those states that utilized the revised birth certificate as of 2009 was performed; given that there was a gradual uptake of states using the revised birth certificate on an annual basis, this sensitivity analysis controls for the potential bias of the shifting sampling frame. Additionally, to assess the validity of our classification of attempted vaginal delivery we repeated the sensitivity analysis using a separate variable indicating trial of labor, and excluding diagnoses of fetal intolerance of labor and long labor, given concerns related to the quality of these latter diagnoses.26 Finally, we assessed temporal trends in the diagnosis of gastroschisis in the restricted cohorts of states using the revised birth certificate as of 2009 to similarly account for the changing sampling frame. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4.

RESULTS

For the primary analysis evaluating factors associated with planned cesarean versus attempted vaginal delivery a total of 5,985 pregnancies between 2005 and 2013 had a diagnosis of gastroschisis, met inclusion criteria, and were included. Of this cohort, 63.5% (3,800 pregnancies) had an attempted vaginal delivery and 36.5% (2,185) underwent planned cesarean delivery. The rate of attempted vaginal delivery increased from 59.7% in 2005 to 68.8% in 2013 (P<0.001). Besides year of delivery, other factors significantly associated with type of delivery included race and parity; Hispanic women were less likely (58.8%) and parous women more likely (68.8%) to attempt vaginal delivery than non-Hispanic white (64.7%) and nulliparous women respectively (60.8). Earlier gestational age at delivery was associated with lower probability of attempted vaginal delivery with women ≥28 to <32 weeks attempting vaginal delivery in 52.9% of cases (Table 1). Other significant factors included gestational age at prenatal care entry. In the adjusted log linear model, the following factors retained significance: (i) the final years of the study (2011–2013) were associated with increased probability of vaginal delivery relative to 2005; (ii) multiparity was associated with increased probability of attempted vaginal delivery compared to nulliparity, (iii) Hispanic ethnicity and earlier gestational age at delivery were associated with decreased probability of attempted vaginal delivery compared to non-Hispanic white race and later gestational age, respectively.

Table 1.

Univariate and adjusted analysis of attempted vaginal versus planned cesarean delivery

| Univariate analysis | Multivariable log linear model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Attempted vaginal delivery, % (n) | P value | Adjusted Risk ratio | 95% confidence interval | |

|

| ||||

| All patients | 63.5 (3,800) | |||

| Live-born parity | <0.001 | |||

| Nulliparous | 60.8 (2419) | 1.00 | Referent | |

| Parous | 68.8 (1358) | 1.14 | (1.09–1.19) | |

| Unknown | 65.7 (23) | 1.05 | (0.82–1.34) | |

| Maternal age, years | 0.021 | |||

| <20 | 60.6 (1163) | 1.02 | (0.95–1.09) | |

| 20–24 | 65.0 (1736) | 1.04 | (0.98–1.10) | |

| 25–29 | 65.2 (632) | 1.00 | Referent | |

| 30–34 | 63.9 (200) | 0.97 | (0.88–1.07) | |

| >34 | 60.5 (69) | 0.91 | (0.78–1.06) | |

| Gestational age | <0.001 | |||

| ≥28 to <32 weeks | 52.9 (146) | 1.00 | Referent | |

| ≥32 to <36 weeks | 59.9 (1152) | 1.15 | (1.02–1.29) | |

| ≥36 to <39 weeks | 66.2 (1990) | 1.27 | (1.14–1.43) | |

| ≥39 to <42 weeks | 65.7 (512) | 1.26 | (1.11–1.42) | |

| Highest level of education | 0.941 | |||

| <9th grade | 62.2 (120) | 1.00 | Referent | |

| 9th grade to 12 grade | 62.4 (961) | 1.01 | (0.89–1.13) | |

| High school graduate | 63.4 (1340) | 0.99 | (0.89–1.12) | |

| Some college credit | 63.8 (894) | 1.00 | (0.88–1.12) | |

| Associate degree | 65.8 (179) | 1.03 | (0.89–1.18) | |

| BS degree | 64.9 (211) | 1.05 | (0.91–1.21) | |

| MS degree | 64.8 (46) | 1.07 | (0.87–1.32) | |

| Doctorate/professional | 71.4 (10) | 1.13 | (0.81–1.59) | |

| Unknown | 68.4 (39) | 0.96 | (0.77–1.20) | |

| Year | <0.001 | |||

| 2005 | 59.7 (188) | 1.00 | Referent | |

| 2006 | 57.0 (274) | 0.96 | (0.85–1.08) | |

| 2007 | 57.4 (322) | 0.98 | (0.87–1.10) | |

| 2008 | 63.4 (426) | 1.07 | (0.96–1.20) | |

| 2009 | 60.6 (425) | 1.03 | (0.92–1.14) | |

| 2010 | 63.4 (471) | 1.06 | (0.96–1.18) | |

| 2011 | 65.9 (563) | 1.11 | (1.00–1.23) | |

| 2012 | 67.5 (570) | 1.14 | (1.03–1.26) | |

| 2013 | 68.8 (561) | 1.16 | (1.04–1.28) | |

| Marital Status | 0.452 | |||

| Married | 64.2 (1099) | 1.00 | Referent | |

| Unmarried | 63.2 (2701) | 1.01 | (0.96–1.06) | |

| Race | <0.001 | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 64.7 (2361) | 1.00 | Referent | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 64.6 (369) | 0.97 | (0.91–1.04) | |

| Non-Hispanic other | 67.5 (158) | 1.03 | (0.93–1.13) | |

| Hispanic | 58.8 (875) | 0.91 | (0.87–0.96) | |

| Unknown | 82.2 (37) | 1.27 | (1.09–1.48) | |

| Prenatal care entry | 0.001 | |||

| 1st to 3rd month | 61.5 (2082) | 1.00 | Referent | |

| 4th to 6th month | 64.9 (1030) | 1.06 | (1.01–1.11) | |

| 7th to final month | 69.4 (263) | 1.12 | (1.05–1.21) | |

| No care | 71.7 (99) | 1.18 | (1.05–1.32) | |

| Unknown | 66.1 (326) | 1.10 | (1.03–1.18) | |

| Preexisting diabetes | 0.374 | |||

| Present | 50.0 (6) | 0.78 | (0.44–1.37) | |

| Absent | 63.5 (3794) | 1.00 | Referent | |

| Chronic hypertension | 0.154 | |||

| Present | 76.9 (20) | 1.27 | (1.03–1.57) | |

| Absent | 63.4 (3780) | 1.00 | Referent | |

| Gestational diabetes | 0.650 | |||

| Present | 54.0 (47) | 0.84 | (0.69–1.02) | |

| Absent | 63.6 (3753) | 1.00 | Referent | |

| Gestational hypertension | 0.959 | |||

| Present | 63.7 (79) | 1.04 | (0.92–1.19) | |

| Absent | 62.2 (3721) | 1.00 | Referent | |

For the epidemiologic analysis of factors associated with gastroschisis, 7,683 pregnancies with the anomaly and 24,829,094 pregnancies without the anomaly were included. The overall incidence was 3.1 cases per 10,000 pregnancies and ranged from 2.9 to 3.2 during the study period. The univariable comparison is demonstrated in Table 2. In this cohort gastroschisis occurred primarily amongst young women; 74.0% of cases were diagnosed in women younger than 25. The risk ratio (RR) in the adjusted model for age <20 was 3.46 (95% confidence interval 3.19–3.75) (Table 3) compared to women age 25–29. Other factors associated with gastroschisis in the adjusted model included smoking (RR 1.61, 95% CI 1.51–1.72), and being unmarried (RR 1.67, 95% CI 1.57–1.77). High school graduation as highest educational attainment was significantly associated with gastroschisis (RR 1.40, 95% CI 1.23–1.59) with <9th grade education as the referent; 9th to 12 grade education, some college and an associates degree were also associated with increased risk for gastroschisis while a master’s degree or doctorate/professional degree were associated with decreased risk. Other factors associated with lower risk for gastroschisis included non-Hispanic black race (RR 0.44, 95% CI 0.41–0.48) and Hispanic ethnicity (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.64–0.73) with white race as the referent, and the presence of chronic hypertension (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.44–0.84). Increasing BMI was associated with a decreased risk for gastroschisis in a “dose-dependent” fashion: Compared to normal weight women, the risk ratio for overweight women was 0.70 (95%CI 0.65–0.77), for obese women with BMI 30.0–34.9 it was 0.49 (0.43–0.56), for BMI 35.0–39.9 it was 0.38 (0.31–0.47), and for obese women with BMI >40 it was 0.26 (0.19–0.36).

Table 2.

Prevalence of and risk factors associated with gastroschisis

| Gastroschisis incidence | Gastroschisis | No gastroschisis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Per 10,000 | % | n | % | n | |

|

| |||||

| All patients | 3.1 | 7,683 | 24,829,094 | ||

| Parity | |||||

| Nulliparous | 4.9 | 62.5 | 4,798 | 39.8 | 9,875,617 |

| Parous | 1.9 | 36.9 | 2,830 | 59.6 | 14,801517 |

| Unknown | 3.6 | 0.7 | 55 | 0.6 | 151,960 |

| Age, years | |||||

| <20 | 10.2 | 30.4 | 2,336 | 9.24 | 2,291,664 |

| 20–24 | 5.6 | 43.6 | 3,348 | 24.1 | 5,985,336 |

| 25–29 | 1.9 | 17.3 | 1,327 | 28.2 | 7,004,452 |

| 30–34 | 0.8 | 6.1 | 472 | 23.9 | 5,943,870 |

| >34 | 0.6 | 2.6 | 200 | 14.5 | 3,603,772 |

| Highest level of education | |||||

| <9th grade | 2.0 | 3.3 | 255 | 5.1 | 1,267,877 |

| 9th grade to 12 grade | 5.3 | 25.3 | 1,941 | 14.7 | 3,657,185 |

| High school graduate | 4.3 | 35.4 | 2,722 | 25.4 | 6,303,068 |

| Some college credit | 3.5 | 22.7 | 1,744 | 20.1 | 4,989,457 |

| Associate degree | 2.0 | 4.7 | 361 | 7.2 | 1,781,608 |

| BS degree | 1.0 | 5.7 | 442 | 17.2 | 4,276,058 |

| MS degree | 0.6 | 1.4 | 107 | 7.1 | 1,757,605 |

| Doctorate/professional | 0.4 | 0.3 | 20 | 2.0 | 493,825 |

| Unknown | 3.0 | 1.2 | 91 | 1.2 | 302,411 |

| Year | |||||

| 2005 | 3.2 | 5.3 | 404 | 5.1 | 1,274,557 |

| 2006 | 2.9 | 7.8 | 598 | 8.4 | 2,082,629 |

| 2007 | 3.1 | 9.5 | 729 | 9.6 | 2,381,081 |

| 2008 | 3.1 | 11.2 | 859 | 11.0 | 2,743,047 |

| 2009 | 3.2 | 11.8 | 900 | 11.3 | 2,800,219 |

| 2010 | 3.0 | 12.3 | 943 | 12.4 | 3,091,522 |

| 2011 | 3.2 | 14.1 | 1,084 | 13.6 | 3,388,437 |

| 2012 | 3.2 | 14.5 | 1,116 | 14.1 | 3,500,152 |

| 2013 | 2.9 | 13.7 | 1,050 | 14.4 | 3,567,450 |

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married | 1.6 | 29.9 | 2,300 | 59.7 | 14,822,523 |

| Unmarried | 5.4 | 70.1 | 5,383 | 40.3 | 10,006,571 |

| Race | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 3.5 | 59.9 | 4,604 | 52.6 | 13,060,137 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 2.4 | 10.4 | 799 | 13.6 | 3,374,368 |

| Non-Hispanic other | 1.8 | 3.9 | 296 | 6.5 | 1,620,916 |

| Hispanic | 2.9 | 25.0 | 1,924 | 26.5 | 6,578,384 |

| Unknown | 3.1 | 0.8 | 60 | 0.8 | 195,289 |

| Prenatal care presentation | |||||

| 1st to 3rd month | 2.5 | 55.3 | 4,251 | 67.8 | 16,845,517 |

| 4th to 6th month | 4.2 | 26.6 | 2,042 | 19.6 | 4,856,012 |

| 7th to final month | 4.4 | 6.4 | 492 | 14.5 | 1,121,167 |

| No care | 5.6 | 3.0 | 227 | 1.6 | 407,948 |

| Unknown | 4.2 | 8.7 | 671 | 6.4 | 1,598,450 |

| Multiple gestation | |||||

| Singleton | 3.1 | 97.8 | 7,512 | 96.6 | 23,979,384 |

| Twin | 2.0 | 2.1 | 166 | 3.3 | 813,852 |

| Triplet or higher | 1.4 | 0.1 | 5 | 0.1 | 35,858 |

| Pregestational diabetes | |||||

| Present | 1.5 | 0.4 | 27 | 0.7 | 175,310 |

| Absent | 3.1 | 99.2 | 7,623 | 99.1 | 24,610,950 |

| Unknown | 7.7 | 0.4 | 33 | 0.2 | 42,834 |

| Chronic hypertension | |||||

| Present | 1.2 | 0.5 | 39 | 1.3 | 317,207 |

| Absent | 3.1 | 99.1 | 7,611 | 98.6 | 24,469,053 |

| Unknown | 7.7 | 0.4 | 33 | 0.2 | 42,834 |

| Smoking | |||||

| Present | 7.4 | 19.7 | 1,516 | 8.3 | 2,052,424 |

| Absent | 2.7 | 67.4 | 5,179 | 78.1 | 19,399,146 |

| Unknown | 2.9 | 12.9 | 988 | 13.6 | 3,377,524 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)¥ | |||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 5.9 | 7.0 | 228 | 3.7 | 387,105 |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 3.9 | 57.0 | 1,854 | 44.9 | 4,695,030 |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 2.6 | 20.2 | 655 | 24.4 | 2,547,371 |

| Obesity (30.0–34.9) | 1.8 | 7.4 | 241 | 12.7 | 1,331,599 |

| Obesity (35.0–39.9) | 1.4 | 2.7 | 88 | 6.0 | 624,758 |

| Obesity (≥ 40) | 0.9 | 1.2 | 40 | 4.1 | 426,308 |

| Unknown | 3.2 | 4.4 | 144 | 4.3 | 443,868 |

| Chlamydia during pregnancy¥ | |||||

| Present | 3.0 | 95.6 | 3109 | 97.9 | 10,252,322 |

| Absent | 6.8 | 4.4 | 141 | 2.9 | 206,833 |

| Insurance status¥ | |||||

| Medicaid | 4.5 | 62.1 | 2,017 | 43.1 | 4,502,049 |

| Private | 1.9 | 28.2 | 918 | 46.4 | 4,855,913 |

| Self-pay | 1.8 | 2.5 | 80 | 4.2 | 442,258 |

| Other | 3.6 | 5.7 | 185 | 4.9 | 513,040 |

| Unknown | 3.5 | 1.5 | 50 | 1.4 | 142,779 |

Incidence listed is number of cases per 10,000 births.

Only 2011–2013 data available. All comparisons were statistically significant with p<0.001.

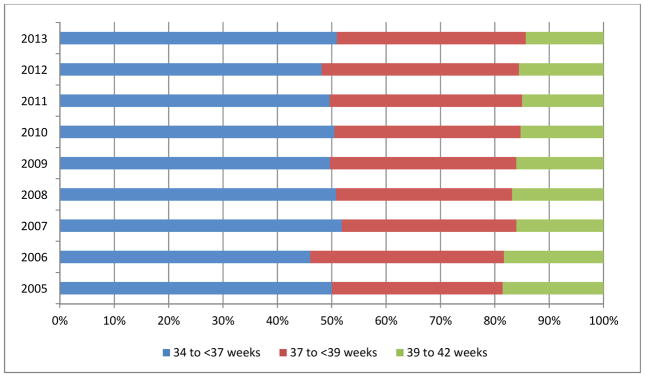

Gastroschisis was more common in the setting of other fetal anomalies with an incidence of 64.6 per 100,000 compared to 3.0 per 10,000 pregnancies when another anomaly wasn’t present; anomalies ascertained included anencephaly, cyanotic congenital heart disease, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, limb reduction defect, cleft lip, and/or cleft palate. Preterm delivery was more common for pregnancies complicated by gastroschisis. Delivery between from 32 to <36 weeks occurred in 31.6% of pregnancies complicated by gastroschisis versus 5.6% of pregnancies without the anomaly. Gestational age at delivery for patients 34 to 42 weeks with gastroschisis was analyzed by year and is demonstrated in Figure 1. The proportion of fetuses delivering in the late preterm, early term, and full term periods was similar across the study period.

Figure 1. Gestational age at delivery for pregnancies complicated by gastroschisis.

The figure demonstrates the proportion of pregnancies 34–42 weeks gestational age complicated by gastroschisis delivered in the late preterm, early term, and full term periods.

A sensitivity analysis restricted to states utilizing the revised birth certificate as of 2009 was performed. The proportion of women with gastroschisis attempting vaginal delivery rose annually from 60.7% in 2009 to 68.8% in 2013 and was similar on a year-by-year basis to the primary analysis. This sensitivity analysis was repeated excluding diagnoses of fetal intolerance of labor and long labor and including a diagnosis of trial of labor. The proportion of women attempting vaginal delivery rose annually from 59.4% in 2009 to 67.3% in 2013 and was similar on a year-by-year basis to the primary analysis. Finally, the rate of gastroschisis was analyzed in the restricted cohort of states using the revised birth certificate as of 2009. The rate ranged from a low 2.9 per 10,000 deliveries in 2013 to a high of 3.3 in 2009, rates similar to the initial analysis.

COMMENT

The findings of this analysis suggest that attempted vaginal delivery is becoming increasing prevalent for women with pregnancies affected by gastroschisis. This may be secondary to recommendations from research literature diffusing into clinical practice. Mode of delivery for gastroschisis has historically represented a major controversy in obstetric management; proponents of cesarean delivery have suggested that cesarean delivery may improve outcomes by decreasing risk for bowel contamination and injury and allow for optimal coordination of pediatric surgical care.18 Small early reports suggested potential benefit for cesarean;12,27 however, these findings were not confirmed in subsequent analyses.18–21 A meta-analysis of the small series that comprise the research evidence found no benefit for cesarean in terms of ischemic bowel, small bowel obstruction, necrotizing enterocolitis, sepsis, or mortality.18 While attempted vaginal delivery did increase during the study period, a significant proportion of women still underwent planned cesarean, suggesting that delivery by cesarean apart from obstetric indications may be further reduced.

The epidemiological analysis of factors associated with gastroschisis suggests that a number of medical and obstetric demographic characteristics are associated with significantly increased or decreased risk for the anomaly. Younger women were at increased risk as were smokers, those with lower educational attainment, and nulliparous women. Factors protective for gastroschisis include being married, chronic hypertension, high educational attainment, non-Hispanic black race, and obesity. These findings support associations found in previous analyses including reduced risk with obesity.1,3–6,28 The magnitude of reduced risk with obesity suggests a potential metabolic etiology for gastroschisis. Given the morbidity associated with gastroschisis and that the etiology is unknown, further research into the protective role of obesity is warranted. While several reports have suggested increasing prevalence of gastroschisis,29–32 our results did not demonstrate this temporal trend.

In interpreting the study’s findings there are important limitations that should be considered. First, capture of accurate diagnoses and validity are concerns with birth certificate data;24–26 in particular obstetric and maternal risk factors in analyses may be sub-optimally documented.33 In our primary analysis, we attempted to restrict our cohort to patients at high likelihood for being able to undergo attempted vaginal delivery, absent the gastroschisis diagnosis; however, given that we are not able to perform individual chart reviews for the included cases, it is not possible to verify the algorithm used. A second potential limitation is that given the limited data on outpatient care, including ultrasonographic evaluation of the anomaly, we are unable to comment to what degree factors from prenatal care may have contributed to a decision to undergo attempted vaginal or planned cesarean delivery. While review of medical records form a large hospital system could provide insight into the specifics of clinical decision-making, this analysis is limited in that regard. Third, gastroschisis is readily diagnosable on ultrasound and associated with increased risk for fetal death; this analysis cannot assess stillbirths given the restricted maternal data for these pregnancies, nor are pregnancy terminations included. If stillbirths and pregnancy terminations differ significantly compared to live births based on maternal characteristics, our results could be biased depending on the composition of the unmeasured population. Fourth, while it is highly likely that a major birth defect is present if documented on the birth certificate, birth defects on the whole are underreported 23 and sensitivity for major birth defects, including gastroschisis, may be modest.34 That management, risk factors, and/or outcomes could differ for unreported versus reported cases is a limitation of the analysis. Fifth, another significant limitation is that while our study evaluated main effects, interaction effects were not evaluated. Sixth, for some characteristics such as hypertension, the number of patients was small and interpretability of effect is thus limited. Finally, given that (i) there may be a small increased risk of gastroschisis recurrence35 and (ii) this dataset cannot link sibling pregnancies, there may be a small clustering effect that cannot be accounted for. Strengths of the study include: (i) a large dataset of cases of gastroschisis which approaches the full national sample of births towards the end of the study period, (ii) the ability to restrict women with other potential indications for cesarean, and (iii) sensitivity analyses restricted to states using the revised birth certificate as of 2009, allowing us to control for the changing sampling frame. Given the large numbers of patients included in the analysis, some statistically significant differences may not be representative of meaningful clinical differences. The cause of planned cesarean still occurring at relatively high rates even at the end of the study period is unclear; patient factors, fetal factors, physician preference, and limited evidence in the form of relatively small prior studies may all play a role in continuation of this practice.

In summary, our findings suggest attempted vaginal delivery is becoming increasingly prevalent for women with a pregnancy complicated by gastroschisis. Recommendations from research literature findings may be diffusing into clinical practice. A significant proportion of women with this anomaly still deliver by planned cesarean suggesting further reduction of surgical delivery for this anomaly is possible. Given the magnitude of reduced risk for gastroschisis in the setting of obesity, further research into the role of this risk factor is warranted.

Acknowledgments

The study authors would like to acknowledge Amy Branum, Michelle Osterman, and Joyce Martin at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for their assistance with analyzing the US Natality data set.

Funding Dr. Friedman is supported by a career development award (1K08HD082287-01A1) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors report no conflict of interest

Level of evidence Level II

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.David AL, Tan A, Curry J. Gastroschisis: sonographic diagnosis, associations, management and outcome. Prenatal diagnosis. 2008;28:633–44. doi: 10.1002/pd.1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barisic I, Clementi M, Hausler M, et al. Evaluation of prenatal ultrasound diagnosis of fetal abdominal wall defects by 19 European registries. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001;18:309–16. doi: 10.1046/j.0960-7692.2001.00534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baer RJ, Chambers CD, Jones KL, et al. Maternal factors associated with the occurrence of gastroschisis. American journal of medical genetics Part A. 2015 doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stothard KJ, Tennant PW, Bell R, Rankin J. Maternal overweight and obesity and the risk of congenital anomalies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama. 2009;301:636–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Getz KD, Anderka MT, Werler MM, Case AP. Short interpregnancy interval and gastroschisis risk in the National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Birth defects research Part A, Clinical and molecular teratology. 2012;94:714–20. doi: 10.1002/bdra.23061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mac Bird T, Robbins JM, Druschel C, et al. Demographic and environmental risk factors for gastroschisis and omphalocele in the National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2009;44:1546–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.10.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feldkamp ML, Carey JC, Sadler TW. Development of gastroschisis: review of hypotheses, a novel hypothesis, and implications for research. American journal of medical genetics Part A. 2007;143A:639–52. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keys C, Drewett M, Burge DM. Gastroschisis: the cost of an epidemic. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2008;43:654–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.South AP, Stutey KM, Meinzen-Derr J. Metaanalysis of the prevalence of intrauterine fetal death in gastroschisis. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2013;209:114, e1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grant NH, Dorling J, Thornton JG. Elective preterm birth for fetal gastroschisis. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2013;6:CD009394. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009394.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baud D, Lausman A, Alfaraj MA, et al. Expectant management compared with elective delivery at 37 weeks for gastroschisis. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2013;121:990–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31828ec299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakala EP, Erhard LN, White JJ. Elective cesarean section improves outcomes of neonates with gastroschisis. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1993;169:1050–3. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90052-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sipes SL, Weiner CP, Sipes DR, 2nd, Grant SS, Williamson RA. Gastroschisis and omphalocele: does either antenatal diagnosis or route of delivery make a difference in perinatal outcome? Obstetrics and gynecology. 1990;76:195–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis DF, Towers CV, Garite TJ, Jackson DN, Nageotte MP, Major CA. Fetal gastroschisis and omphalocele: is cesarean section the best mode of delivery? American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1990;163:773–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)91066-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moretti M, Khoury A, Rodriquez J, Lobe T, Shaver D, Sibai B. The effect of mode of delivery on the perinatal outcome in fetuses with abdominal wall defects. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1990;163:833–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)91079-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirk EP, Wah RM. Obstetric management of the fetus with omphalocele or gastroschisis: a review and report of one hundred twelve cases. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1983;146:512–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(83)90791-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quirk JG, Jr, Fortney J, Collins HB, 2nd, West J, Hassad SJ, Wagner C. Outcomes of newborns with gastroschisis: the effects of mode of delivery, site of delivery, and interval from birth to surgery. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1996;174:1134–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70655-5. discussion 8–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Segel SY, Marder SJ, Parry S, Macones GA. Fetal abdominal wall defects and mode of delivery: a systematic review. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2001;98:867–73. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01571-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salihu HM, Emusu D, Aliyu ZY, Pierre-Louis BJ, Druschel CM, Kirby RS. Mode of delivery and neonatal survival of infants with isolated gastroschisis. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2004;104:678–83. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000139513.93115.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.How HY, Harris BJ, Pietrantoni M, et al. Is vaginal delivery preferable to elective cesarean delivery in fetuses with a known ventral wall defect? American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2000;182:1527–34. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Puligandla PS, Janvier A, Flageole H, Bouchard S, Laberge JM. Routine cesarean delivery does not improve the outcome of infants with gastroschisis. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2004;39:742–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osterman MJ, Martin JA, Mathews TJ, Hamilton BE. Expanded data from the new birth certificate, 2008. National vital statistics reports : from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. 2011;59:1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boulet SL, Shin M, Kirby RS, Goodman D, Correa A. Sensitivity of birth certificate reports of birth defects in Atlanta, 1995–2005: effects of maternal, infant, and hospital characteristics. Public health reports. 2011;126:186–94. doi: 10.1177/003335491112600209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reichman NE, Hade EM. Validation of birth certificate data. A study of women in New Jersey’s HealthStart program. Annals of epidemiology. 2001;11:186–93. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00209-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roohan PJ, Josberger RE, Acar J, Dabir P, Feder HM, Gagliano PJ. Validation of birth certificate data in New York State. Journal of community health. 2003;28:335–46. doi: 10.1023/a:1025492512915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin JA, Wilson EC, Osterman MJ, Saadi EW, Sutton SR, Hamilton BE. Assessing the quality of medical and health data from the 2003 birth certificate revision: results from two states. National vital statistics reports : from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. 2013;62:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lenke RR, Hatch EI., Jr Fetal gastroschisis: a preliminary report advocating the use of cesarean section. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1986;67:395–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waller DK, Shaw GM, Rasmussen SA, et al. Prepregnancy obesity as a risk factor for structural birth defects. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2007;161:745–50. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.8.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirby RS, Marshall J, Tanner JP, et al. Prevalence and correlates of gastroschisis in 15 states, 1995 to 2005. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2013;122:275–81. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31829cbbb4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vu LT, Nobuhara KK, Laurent C, Shaw GM. Increasing prevalence of gastroschisis: population-based study in California. The Journal of pediatrics. 2008;152:807–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kilby MD. The incidence of gastroschisis. Bmj. 2006;332:250–1. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7536.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Collins SR, Griffin MR, Arbogast PG, et al. The rising prevalence of gastroschisis and omphalocele in Tennessee. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2007;42:1221–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kahn EB, Berg CJ, Callaghan WM. Cesarean delivery among women with low-risk pregnancies: a comparison of birth certificates and hospital discharge data. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2009;113:33–40. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318190bb33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watkins ML, Edmonds L, McClearn A, Mullins L, Mulinare J, Khoury M. The surveillance of birth defects: the usefulness of the revised US standard birth certificate. American journal of public health. 1996;86:731–4. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.5.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kohl M, Wiesel A, Schier F. Familial recurrence of gastroschisis: literature review and data from the population-based birth registry “Mainz Model”. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:1907–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]