Abstract

Lung contusion (LC) is a significant risk factor for the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR-9) recognizes specific unmethylated CpG motifs, which are prevalent in microbial but not vertebrate genomic DNA, leading to innate and acquired immune responses. TLR-9 signaling has recently been implicated as a critical component of the inflammatory response following lung injury. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the contribution of TLR-9 signaling to the acute physiologic changes following LC. Non-lethal unilateral closed-chest LC was induced in TLR-9 (−/−) and wild type (WT) mice. The mice were sacrificed at 5, 24, 48, and 72 hour time points. The extent of injury was assessed by measuring bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), cells (cytospin), albumin (permeability injury), and cytokines (inflammation). Following LC, only the TLR-9 (−/−) mice showed significant reductions in the levels of albumin; release of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and KC; production of macrophage chemoattractant protein 5 (MCP-5); and recruitment of alveolar macrophages and neutrophil infiltration. Histological evaluation demonstrated significantly worse injury at all-time points for WT mice. Macrophages, isolated from TLR-9 (−/−) mice, exhibited increased phagocytic activity at 24 hours after LC compared to those isolated from WT mice. TLR-9, therefore, appears to be functionally important in the development of progressive lung injury and inflammation following LC. Our findings provide a new framework for understanding the pathogenesis of lung injury and suggest blockade of TLR-9 as a new therapeutic strategy for the treatment of LC-induced lung injury.

Keywords: Lung contusion, Toll-like receptor 9, Phagocytosis, Macrophages

Introduction

Blunt chest trauma is involved in nearly one-third of acute trauma admissions. Lung contusion (LC) is the primary cause of mortality following this type of injury and is an independent risk factor for the development of acute lung injury (ALI), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) (1, 2). The clinical pathophysiology of LC includes hypoxemia, hypercarbia, and increased effort for respiration, decreased lung volume and compliance, as well as ventilation-perfusion mismatch (1, 3, 4). These conditions are associated with substantial mortality and morbidity, generating a significant economic burden on the health care system due to the costs of intensive and critical care.

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a class of proteins that play a key role in the innate immune system by recognizing structurally conserved molecules derived from microbes. They are single membrane-spanning non-catalytic receptors and are typically expressed in sentinel cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells. TLR-9 detects non-methylated CpG motifs. The CpG sequences are typically methylated and genetically repressed in vertebrates but can be found un-methylated in viruses, bacteria, and molds (5). Prior research on the role of TLR-9 in sepsis and lung injury has focused on its interactions with artificial CpG DNAs (6). Jian-Zhang et al. reported that the Toll-like receptor 9/NF-κB pathway contributes to post-traumatic systemic inflammatory response syndrome and lung injury in rats (7). Recent studies suggest that TLR-9 plays a role in the development of renal diseases such as glomerulonephritis and lupus nephritis (8) and that TLR-9 triggers pro-tumorigenic signaling in mice (9). Jamie et al recently reported that bacterial challenge leads to a regenerative cycle of oxidative mtDNA damage and mtDNA DAMP formation culminating in TLR-9-dependent vascular injury in rats (10). Another very recent study shows that systemic stimulation of TLR-9 by CpG ODN leads to acute vascular injury and is associated with the production of proinflammatory cytokines in mice (11). However, the precise role of TLR-9 in lung contusion remains largely unknown.

In the present study, we examined the role of TLR-9 in the pathogenesis of acute inflammation and injury following LC. We hypothesized that TLR-9 activation through injured cells may be responsible for driving the acute inflammatory cascade associated with such lung insults. The data presented here indicate that inflammatory cells released after lung injury activate the acute inflammatory response through TLR-9, and therefore the inhibition of this TLR may be a new therapeutic strategy for the treatment of lung injury.

Materials and Methods

Human lung

Human lung contusion specimens were obtained from the Heart and Lung Institute, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada, and access to these tissue specimens was approved by the local research ethics committee. For the lung specimens, slides of lung tissue from autopsy samples were obtained from uninjured lung samples and 15 patients who died following lung contusion.

Histology (human and mouse samples)

The formalin-fixed uninjured control and lung-contused sections were paraffin-embedded, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Histological findings such as peribronchial, parenchymal, and perivascular cell infiltration were semi-quantitatively graded in a blinded manner (12).

TLR-9 immunofluorescence staining (human)

The sections that represented histological changes consistent with progression of lung contusion in human subjects were further analyzed for immunohistochemical localization of TLR-9. Briefly, 5 μm sections were de-paraffinized and rehydrated. Following this, heat-induced epitope retrieval was performed in a decloaking chamber containing 1X citrate buffer-pH-6.0 (Dako). Sections were washed and blocked (7% Bovine Serum Albumin + 1% Fetal Calf Serum + 0.05% Azide) for 15 minutes, incubated overnight at 4°C with polyclonal TLR-9 antibody, and incubated with goat anti-rabbit alexa-594 for 60 minutes at RT with intermittent washing. Sections were mounted using ProLong Gold containing DAPI (Invitrogen). All primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in antibody diluent (Dako) containing 2% normal goat serum. Nuclei were stained with DAPI, the cells on coverslips were mounted in mounting media (Dako), and photomicrographs of the invasive sections were analyzed digitally using Photoshop software version 9.0.2.

Quantification of Immunoflorescent images

For the Immunoflorescent images, antibody staining was quantified by Image J software (v1.48, NIH). Box plots and statistical analysis (2-sided unpaired Student t tests) were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.

Animals

Male age-matched (6–8 weeks) wild type (C57/BL6) and TLR-9 (−/−) mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were utilized in this study. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at University of Michigan and complied with state, federal, and National Institutes of Health regulations. The number of animals used for each experiment varied from six to 14, and a detailed summary is provided for each experimental strategy.

Murine model for lung contusion

Male 20–25g C57BL/6 and TLR-9 (−/−) mice (6–8 wk, bred in-house) were anesthetized, and lung contusion was induced (13) and subsequently modified by our group. Briefly, after induction of anesthesia, mice were placed in a left lateral position, and using a cortical contusion impactor the right chest was struck along the posterior axillary line 1.3 cm above the costal margin with a velocity of 5.8 m/sec adjusted to a depth of 10 mm. Mice were then allowed to recover spontaneously.

Albumin concentrations in BAL

Albumin concentrations in BAL were measured by ELISA using a polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse albumin antibody and HRP-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (Bethyl Laboratories, Inc. Montgomery, TX).

Determination of cytokine levels in BAL

Soluble concentrations of IL-1β, MIP-2, CCL-2 (MCP-1), CCL12 (MCP-5), IL-6, KC, and TNF-α in BAL were determined using ELISA. Antibody pairs (one capture antibody and one biotinylated-reporter antibody) and recombinant cytokines for these assays were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Cytospin cell count

For cytospin preparations, BAL cells were centrifuged at 600 x g for 5 minutes using a Cytospin II (Shandon Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), stained with Diff-Quik (Dade Behring Inc., Newark, DE), and analyzed by examination under a light microscope at 20x magnification.

In vitro phagocytosis assay

After LC, alveolar macropahges isolated via BAL were plated at 2 × 105 cells/well and cultured overnight in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium. Wells were aspirated and replaced with 50 μl serum-free medium. Macrophages were then incubated with FITC-labeled, heat-killed P. aeruginosa. Phagocytosis of FITC-labeled bacteria was measured after quenching of non-ingested bacteria with trypan blue, as previously described (12).

TAQMAN Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA was prepared from alveolar macrophages using an RNeasy mini kit, according to the manufacturer’s directions (Qiagen, USA). A total of 1ug RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The cDNA was then amplified by real-time quantitative TaqMan PCR using an ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). GAPDH was analyzed as an internal control. TaqMan gene expression reagents or SYBR Green Master PCR mix were used to assay Fizz 1 (Applied Biosystems). Data are expressed as fold-change in transcript expression. The fold difference in mRNA expression between treatment groups was determined by software developed by Applied Biosystems.

Statistical Methods

Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was estimated using one-way analysis of variance (GraphPad Prism5.01). Individual inter-group comparisons were analyzed using the two-tailed, unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction. The analyses were run at a significance level of p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001 (12, 14–16).

Results

1. TLR-9 is functionally important in the development of progressive lung injury and inflammation following LC

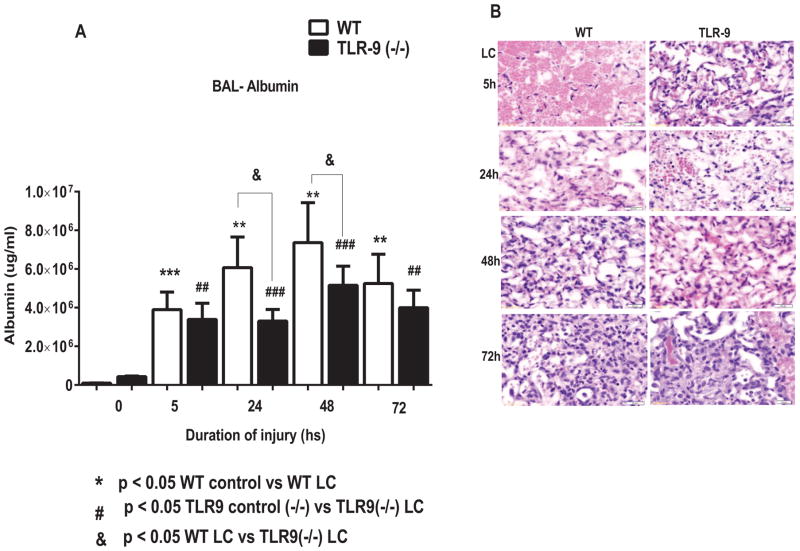

TLR-9 (−/−) mice showed decreased permeability injury following LC

To determine the functional role of TLR-9 in the extent of mechanical injury following LC, we performed experiments using TLR-9 knockout mice and corresponding WT mice (n=12). We have previously shown that the acute inflammatory response in LC is associated with severe permeability injury and is responsible for deficits in oxygenation and increases in quasi-static pulmonary compliance (12, 14, 17–19). Here, we first examined the BAL albumin level via ELISA at 5, 24, 48, and 72 hour time points following lung contusion. There was a significant reduction in BAL albumin level, a specific indicator of the extent of permeability injury, in the TLR-9 knockout mice compared to corresponding WT mice at 24 and 48 hours following LC (Figure 1A). Histological evaluation demonstrated significantly greater injury in WT mice compared to TLR-9 (−/−) mice at all-time points (Figure 1 B). Hemorrhage was the predominant lesion at 5 hours, with much more severe hemorrhage and alveolar wall necrosis in WT mice. At 24 hours, there were large areas of hemorrhage and necrosis in WT mice. The alveoli from this time point were partially collapsed, had thickened walls, and were filled with fibrin, RBCs, necrotic cells, and alveolar macrophages. In TLR-9 mice there was some mild to moderate hemorrhage in limited areas with some damage to alveolar walls and an increase in alveolar macrophages. In WT mice there was still a large area of hemorrhage and necrosis at 48 hours similar to the lesion at 24 hours. In TLR-9 mice there was a small focus of resolving sub-acute consolidation. At 72 hours, the WT mice had a large area of sub-acute consolidation and lesions similar to those at 24 and 48 hours. The TLR-9 mice had resolved most of the lesion, and an area of slightly thickened alveolar walls was the only evidence of previous injury (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Injury and inflammation was reduced in TLR9 (−/−) mice following lung contusion.

A: After LC, mice were sacrificed at different time points, and albumin concentration in the BAL were determined by ELISA (n=14 per group). Statistical analysis was performed with two-tailed unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction. *P< 0.05 WT vs. TLR9 (−/−) mice. B. Histological evaluation of WT and TLR9 (−/−) mice following LC: In WT mice showed significantly more injury at all the time points compared to TLR9 (−/−) mice. See result section for detail.

2. TLR-9 (−/−) mice exhibited signs of decreased lung inflammation following LC

To determine whether TLR-9 activation has a role in the production of pro/anti-inflammatory mediators following LC, we measured the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (interleukin [IL]-1β and IL-6), monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1 and MCP-5), chemokines, and Keratinocyte chemoattractant (KC). The levels of IL-1β were significantly lower in TLR-9 (−/−) mice at 5h compared to WT mice (Figure 2A). The IL-6 levels in the BAL were significantly higher at 5, 24, and 48 hour time points in WT mice (Figure 2B). The levels of KC (Figure 2E) and MCP-1 (CCL2) (Figure 2C) were both significantly elevated at 24 and 48 hours following LC compared to TLR-9 (−/−) mice. Levels of MCP-5 (CCL12) were significantly reduced at 48 hours following LC in TLR-9 (−/−) mice compared to WT mice (Figure 2D). TNF-α level was significantly lower after LC in the TLR-9 (−/−) mice at 24 and 48 hour time points (Figure 2F). Taken together, these data suggest that TLR-9 is involved in up-regulating the intensity of acute inflammation following LC.

Figure 2. WT mice showed a significant increase in cytokine response compared to TLR9 (−/−) following LC.

The levels of IL-1β, IL-6, MCP-1(CCL2), MCP-5 (CCL12), KC, and TNF-α in the BAL fluid were significantly higher in WT mice following LC compared to TLR9 (−/−) mice (n = 14) (2A-F). Statistical analysis was performed with two-tailed unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction. *P< 0.05 WT vs. TLR9 (−/−) mice.

3. TLR-9 (−/−) mice showed a decrease in BAL neutrophils following LC

We have previously reported that neutrophils are mechanistically important in driving the acute inflammatory response following LC (12–14, 20). We determined the levels of macrophages and neutrophils in BAL fluid collected from both TLR-9 (−/−) and WT groups at different time intervals using cytospin techniques. The levels of neutrophils were significantly higher in WT mice at 48 and 72 hours compared to TLR-9 (−/−) mice. There was no significant different in level of macrophages between WT and TLR-9 (−/−) mice at any time point (Figure 3 B). Alveolar macrophages play a crucial role in mediating innate immune responses in the lung (12, 14). Since increased susceptibility to bacterial infection during lung injuries correlates with defects in alveolar macrophage phagocytosis, we measured ex vivo phagocytosis in an in vitro assay using isolated alveolar macrophages from WT and TLR-9 knockout mice. The relative phagocytic activity was significantly higher after LC in TLR-9 knockout mice at 24h compared to WT mice. The alveolar macrophage characterization is an important determinant of whether lung injury progresses or resolves. The M1 phenotype (also termed classically activated) is characterized by increased production of oxidative burst and nitric oxide release, and conversely, the M2 phenotype (also termed alternatively activated) is associated with decreased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and upregulation of FIZZ-1 pathways. The TLR-9 (−/−) mice showed a protective M2 (alternatively activated) as evidenced by increased Fizz-1 expression, suggesting a functional alteration and change in polarity of alveolar macrophages (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Neutrophil levels in BAL were higher in WT mice following LC.

Cytospin analysis of BAL samples was performed after lung injury. The levels of neutrophils were significantly higher in WT mice compared to TLR9 (−/−) mice (3A). The levels of macrophages were not significantly different from both groups (n = 14 per group) (3B). Statistical analysis was performed with two-tailed unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction. *P< 0.05 WT vs. TLR9 (−/−) mice. Phagocytosis assay: BAL Macrophages from WT and TLR9 (−/−) following LC were incubated with FITC-labeled heat-killed Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n=5) (3C). Quantitative TaqMan PCR analysis: FIZZ1 transcript expression was measured in WT and TLR9 (−/−) mice following LC (3D). Real time PCR analysis demonstrated a significant increase in the levels of Fizz-1 in TLR9 (−/−) mice (n =5). **P< 0.01 and *P< 0.05 WT vs. TLR9 (−/−).

4. TLR-9 expression was elevated in human and mouse lung contusion samples

Histological evaluation of post-mortem samples from patients with LC reveals a substantial degree of severe diffuse alveolitis characterized by admission of macrophages and rare lymphocytes compared to the normal lungs (Figure 4A and B). Immunofluorescence data demonstrated that samples from patients with lung contusion have ample expression of TLR-9, especially in alveolar macrophages (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Increased TLR-9 expression in lung contusion.

Post-mortem lung samples in patients with LC compared to normal lung tissue. Histological analysis of post-mortem lung samples in control and patient with LC (4A). Representative immunofluorescent images from human lung stained with anti-TLR9 antibody (4B). Quantification of immunofluorescent images analysis (4C). These samples were obtained from the tissue bank at the University of British Columbia. No clinical data other than the diagnosis of the banked specimen was provided.

5. TLR-9 expression was higher in mouse lung contusion samples

Mice immunofluorescent data demonstrate intense TLR-9 signal in alveolar macrophage and epithelial cells following LC (Figure 5).

Figure 5. WT mice showed predominant TLR-9 expression following LC.

WT mice of C57BL/6 background were subjected to LC. The lung samples were harvested at 5, 24, 48, and 72 hour time points, and the samples were subjected to immunofluorescent staining with anti-TLR-9 antibody (red) and nuclear staining with DAPI (5A). Quantification of immunofluorescent images analysis (5B) (n=3 per group).

Discussion

Lung contusion remains a critical problem as the primary cause of mortality following blunt chest trauma and blast explosions. A significant gap in our understanding of the factors responsible for deterioration of some patients with LC into severe respiratory failure still endures. The mortality and economic burden of ALI/ARDS are considerable despite the sophistication of critical care medicine, which remains purely supportive. Our lab has focused on identifying factors that contribute to injury progression. TLR-9 is one such promising factor, and the data presented here clearly demonstrate that its presence following LC results in the activation and development of the severe acute inflammatory response such as in acute respiratory failure.

TLRs have a primary role in the response to acute lung injury and inflammation, and systemic innate immune responses are dependent on TLR activation by pulmonary contusion (13). TLR-9 dependent responses to pulmonary contusion include hypoxemia, edema, neutrophil infiltration, and increased production of inflammatory cytokines. It is well known that TLR-3 activation in viral diseases is specifically mediated by ligation with double stranded DNA particles. However, it remains unclear as to what activates TLR-9 in acute inflammation post-trauma such as in the setting of LC. Recent studies have revealed the presence of circulating mitochondrial DNA in sera of trauma subjects. Here, we demonstrate that signaling through TLR-9 is also involved in the initial systemic inflammatory response in a model of lung contusion. In the present study, TLR-9 mediated inflammation following LC was evidenced by the enhanced production of IL-1β, IL-6, MCP-1, and MCP-5 in BAL cells following blunt chest trauma. The ligand known to interact with TLR-9 is CpG DNA. However, we were unfortunately not able to detect any significant amount of circulating mtDNA in the sera of injured WT mice (21).

Previous studies have shown that TLR-9 may play an important role in renal disease and inflammatory conditions in other organ systems. Anders et al. reported that activation of TLR-9 induces progression of renal disease in MRL-Fas (lpr) mice (22). TLR-9 has been shown to be involved in antigen-induced immune complex glomerulonephritis and lupus nephritis through regulation of both humoral and cellular immune responses (23). Hasin et al. reported that IL-6 is a pleiotropic cytokine that plays a central role in modulating inflammatory responses and is also a reliable predictor of mortality in ESRD (24). In our study, we also found that IL-6 levels in the BAL of WT mice were significantly higher at 5, 24, and 48 hour time points following LC (Figure 2B).

Previously, we have shown that ALI following LC is neutrophil dependent (18). We have also demonstrated the recruitment and activation of neutrophils and lung tissue macrophages as well as the production of multiple cytokines and chemokines in LC (12). Neutrophils are activated, at least in part, by Toll-like receptors (TLRs) (13, 25). Zhang et al. recently showed that marked inflammatory responses in the lungs are mediated by TLR-9 activation of lung neutrophils in a trauma injury model. Here, we show that the number of neutrophils in the BAL was significantly higher in WT mice after LC. The precise nature of the effect of TLR-9 on neutrophil infiltration in LC remains unclear. However, it is clear that there is diminished recruitment and phagocytic potential of alveolar macrophages in TLR-9 deficiency. It is very likely, therefore, that the absence of TLR-9 increases the potential for macrophage-mediated phagocytosis (Figure 3 B).

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and enable innate immune responses. Although it has been thought that TLR-9 is expressed only in immune cells, there is now increasing evidence that TLR-9 is also expressed in non-immune cells. In the present study, we found that lung contusion was a potent trigger for the induction of TLR-9 expression in the lungs of both rodent and human samples. This finding is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that this pattern recognition receptor is abundantly expressed on lung epithelial cells (26, 27). Moreover, WT mice show a strong TLR-9 signal in alveolar macrophages, indicating that there is a functional alteration in the activation state of these cells following LC (Figure 4).

Previous studies by Hoth et al have suggested an important role for TLR-2, TLR-4, and MyD-88(13). The lung is in constant interaction with the surrounding environment and is commonly confronted by multiple infectious and non-infectious agents. It is likely that following injuries such as lung contusion there is leakage of DAMPs into the surrounding tissue. In addition, the surrounding tissue products and blood released in this environment release a number of agents that come in touch with multiple extracellular, such as TLR-2 and -4, and intracellular, such as TLR-3 and -9, Toll-like receptors. The likely ligands for the activation of TLR-2 and -4 are HMGB-1, Hyaluron, and surfactant protein-A, which are all byproducts of tissue injury. Additionally, intracellular products of tissue and cell injury such as dsRNA and mitochondrial DNA act as specific ligands for TLR-3 and -9, respectively. An excellent review on this subject is provided for additional details (28).

In summary, we have demonstrated that LC triggers expression of TLR-9 in injured cells, leading to amplification of the acute inflammatory response. Inhibition of TLR-9, therefore, may be a valid therapeutic approach to limit the excited local and systemic inflammatory activation associated with acute respiratory failure.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of National Institutes of Health Grants -R01 HL102013 and R01 GM111305-01 (KR)

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 GM111305-01 and HL102013 (K. Raghavendran).

Footnotes

Author contributions: Conception and design, M.V.S and K.R. Performed research, M.V.S., B.T., M.A.S., A.C., R.G., J,M and V.A.D. Analysis and interpretation, M.V.S., B.T., M.A.D, and K.R. Drafting the manuscript for important intellectual content, M.V.S and K.R.

Author Disclosure: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Cohn SM. Pulmonary contusion: review of the clinical entity. J Trauma. 1997;42(5):973–9. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199705000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller PR, Croce MA, Bee TK, Qaisi WG, Smith CP, Collins GL, Fabian TC. ARDS after pulmonary contusion: accurate measurement of contusion volume identifies high-risk patients. J Trauma. 2001;51(2):223–8. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200108000-00003. discussion 229–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oppenheimer L, Craven KD, Forkert L, Wood LD. Pathophysiology of pulmonary contusion in dogs. J Appl Physiol. 1979;47(4):718–28. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1979.47.4.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Eeden SF, Klopper JF, Alheit B, Bardin PG. Ventilation-perfusion imaging in evaluating regional lung function in nonpenetrating injury to the chest. Chest. 1989;95(3):632–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.95.3.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hemmi H, Kaisho T, Takeda K, Akira S. The roles of Toll-like receptor 9, MyD88, and DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit in the effects of two distinct CpG DNAs on dendritic cell subsets. J Immunol. 2003;170(6):3059–64. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Itagaki K, Adibnia Y, Sun S, Zhao C, Sursal T, Chen Y, Junger W, Hauser CJ. Bacterial DNA induces pulmonary damage via TLR-9 through cross-talk with neutrophils. Shock. 2011;36(6):548–52. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182369fb2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang YP, Cai J, Shields LB, Liu N, Xu XM, Shields CB. Traumatic brain injury using mouse models. Transl Stroke Res. 2014;5(4):454–71. doi: 10.1007/s12975-014-0327-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Summers SA, Steinmetz OM, Ooi JD, Gan PY, O’Sullivan KM, Visvanathan K, Akira S, Kitching AR, Holdsworth SR. Toll-like receptor 9 enhances nephritogenic immunity and glomerular leukocyte recruitment, exacerbating experimental crescentic glomerulonephritis. Am J Pathol. 2010;177(5):2234–44. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Y, Yan W, Tohme S, Chen M, Fu Y, Tian D, Lotze M, Tang D, Tsung A. Hypoxia induced HMGB1 and mitochondrial DNA interactions mediate tumor growth in hepatocellular carcinoma through Toll-like receptor 9. J Hepatol. 2015;63(1):114–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krogmann AO, Lusebrink E, Steinmetz M, Asdonk T, Lahrmann C, Lutjohann D, Nickenig G, Zimmer S. Proinflammatory Stimulation of Toll-Like Receptor 9 with High Dose CpG ODN 1826 Impairs Endothelial Regeneration and Promotes Atherosclerosis in Mice. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0146326. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuck JL, Obiako BO, Gorodnya OM, Pastukh VM, Kua J, Simmons JD, Gillespie MN. Mitochondrial DNA damage-associated molecular patterns mediate a feed-forward cycle of bacteria-induced vascular injury in perfused rat lungs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;308(10):L1078–85. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00015.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suresh MV, Yu B, Machado-Aranda D, Bender MD, Ochoa-Frongia L, Helinski JD, Davidson BA, Knight PR, Hogaboam CM, Moore BB, Raghavendran K. Role of macrophage chemoattractant protein-1 in acute inflammation after lung contusion. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;46(6):797–806. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0358OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoth JJ, Hudson WP, Brownlee NA, Yoza BK, Hiltbold EM, Meredith JW, McCall CE. Toll-like receptor 2 participates in the response to lung injury in a murine model of pulmonary contusion. Shock. 2007;28(4):447–52. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e318048801a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raghavendran K, Davidson BA, Helinski JD, Marshcke CJ, Manderscheid PA, Woytash JA, Notter RH, Knight PR. A rat model for isolated bilateral lung contusion from blunt chest trauma. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2005;101:1482–1489. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000180201.25746.1F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raghavendran K, Davidson BA, Mullan BA, Manderscheid PA, Russo T, Hutson AD, Holm BA, Notter RH, Knight PR. Acid and particulate induced aspiration injury in mice: Role of MCP-1. Am J Physiol: Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L134–L143. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00390.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raghavendran K, Davidson BA, Woytash JA, Helinski JD, Marschke CJ, Manderscheid PA, Notter RH, Knight PR. The evolution of isolated, bilateral lung contusion from blunt chest trauma in rats: Cellular and cytokine responses. Shock. 2005;24:132–138. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000169725.80068.4a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raghavendran K, DBA, Huebschmann JC, Helinski JD, Hutson AD, Dayton MT, Notter RH, Knight PR. Superimposed gastric aspiration increases the severity of inflammation and permeability injury in a rat model of lung contusion. J Surg Research. 2008:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raghavendran K, Notter RH, Davidson BA, Helinski JD, Kunkel SL, Knight PR. Lung Contusion: Inflammatory Mechanisms and Interaction with Other Injuries. Shock. 2009 doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31819c385c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dolgachev VA, Yu B, Reinke JM, Raghavendran K, Hemmila MR. Host susceptibility to gram-negative pneumonia after lung contusion. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72(3):614–22. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318243d9b1. discussion 622–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis CG, Chang K, Osborne D, Walton AH, Ghosh S, Dunne WM, Hotchkiss RS, Muenzer JT. TLR3 agonist improves survival to secondary pneumonia in a double injury model. J Surg Res. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Q, Raoof M, Chen Y, Sumi Y, Sursal T, Junger W, Brohi K, Itagaki K, Hauser CJ. Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature. 2010;464(7285):104–7. doi: 10.1038/nature08780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anders HJ, Banas B, Schlondorff D. Signaling danger: toll-like receptors and their potential roles in kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(4):854–67. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000121781.89599.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anders HJ, Vielhauer V, Eis V, Linde Y, Kretzler M, Perez de Lema G, Strutz F, Bauer S, Rutz M, Wagner H, Grone HJ, Schlondorff D. Activation of toll-like receptor-9 induces progression of renal disease in MRL-Fas(lpr) mice. FASEB J. 2004;18(3):534–6. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0646fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang HY, Bian YF, Zhang HP, Gao F, Xiao CS, Liang B, Li J, Zhang NN, Yang ZM. LOX1 is implicated in oxidized lowdensity lipoproteininduced oxidative stress of macrophages in atherosclerosis. Mol Med Rep. 2015 doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.4066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoth JJ, Wells JD, Brownlee NA, Hiltbold EM, Meredith JW, McCall CE, Yoza BK. Toll-Like receptor 4 dependent responses to lung injury in a murine model of pulmonary contusion. Shock. 2008 doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181862279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uehara A, Fujimoto Y, Fukase K, Takada H. Various human epithelial cells express functional Toll-like receptors, NOD1 and NOD2 to produce anti-microbial peptides, but not proinflammatory cytokines. Mol Immunol. 2007;44(12):3100–11. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uehara A, Takada H. Functional TLRs and NODs in human gingival fibroblasts. J Dent Res. 2007;86(3):249–54. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kovach MA, Standiford TJ. Toll like receptors in diseases of the lung. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11(10):1399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]