Abstract

Major Depressive Disorder is a common mental illness with rates increasing during adolescence. This has led researchers to examine developmental antecedents of depression. This study examined the association between depressive symptoms and the interaction between two empirically supported risk factors for depression: poor recovery of the biological stress system as measured through heart rate and cortisol, and cognitive vulnerabilities as indexed by rumination and a negative cognitive style. Adolescents (n = 127; 49 % female) completed questionnaires and a social stress task to elicit a stress response measured with neuroendocrine (cortisol) and autonomic nervous system (heart rate) endpoints. The findings indicated that higher depressive symptoms were associated with the combination of higher cognitive vulnerabilities and lower cortisol and heart rate recovery. These findings can enhance our understanding of stress responses, lead to personalized treatment, and provide a nuanced understanding of depression in adolescence.

Keywords: Adolescence, Depression, Cortisol, Heart rate, Recovery, Cognitive vulnerability

Introduction

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is one of the most common mental illnesses, with rates dramatically increasing as much as six-fold from early to late adolescence, and eventually reaching an estimated lifetime prevalence of 20–25 % (Kessler et al. 2001). Furthermore, early onset of depression during adolescence has been associated with many psychosocial problems in adulthood, including poor academic outcomes and increased risk for substance abuse and suicide (Naicker et al. 2013). Moreover, the occurrence of subsyndromal depressive symptoms during adolescence is associated with later MDD and negative functional outcomes (Wesselhoeft et al. 2013). These trends have led researchers to examine the developmental antecedents of depressive episodes and symptoms in adolescence in hopes of identifying vulnerabilities associated with the first onset of disorder.

The relationship between stress and the onset of depression has been well established. This is especially the case during adolescence as experiences of stressful life events dramatically change from childhood to adolescence (Romeo 2013). Adolescence is a developmental period with a number of important transitions including puberty, parental and peer support, dating, self-identity, and cognitive maturation (Steinberg and Morris 2001). In turn, developmental changes during this time appear to generally affect stress and emotional reactivity responses (Spear 2009), whereby the pre-adolescent and adult brain is differentially sensitive to the impact of stress (Romeo 2010). According to vulnerability-stress models, only some individuals are at risk for depression after exposure to negative events (Monroe and Simons 1991). Indeed, psychological stress is associated with depression for individuals who exhibit negative cognitive styles and, thus, interpret the stressor negatively (Alloy et al. 2012), for those who continually think about their depressed mood and have difficulty disengaging from these thoughts (Michl et al. 2013), and for those who biologically recover from the event in a maladaptive fashion (Burke et al. 2005). Based on models indicating that negative cognitive styles enhance the stressfulness of negative events (e.g., Abramson et al. 1989), models suggesting that ruminative thoughts keep stressful experiences in mind (Nolen-Hoeksema 1991), and models suggesting a connection between cognitions and biological reactions to stress (Brosschot et al. 2006), the current study examined whether negative cognitive styles and rumination amplify the relationship between poor biological recovery from stress and depressive symptoms during adolescence.

Prominent cognitive models of depression, including the hopelessness theory (Abramson et al. 1989), and response styles theory (Nolen-Hoeksema 1991), propose that individuals with certain dysfunctional cognitive styles react to stressful life events maladaptively, enhancing their stressfulness, and, thus, are more vulnerable to developing depression when faced with such events (i.e., cognitive vulnerability-stress models of depression). These theories posit that individuals who make internal, global, and stable attributions for the causes and consequences of negative events (Abramson et al. 1989), and who have the tendency to ruminate on their mood (Nolen-Hoeksema 1991) are likely to develop and maintain depression (Alloy et al. 2006). In parallel, two related theories posit that cognitive interpretations of events will amplify, maintain, or reactivate physiological responses to stress, which place individuals at higher risk of poor outcomes. Indeed, both the appraisal theory, suggesting that individuals who appraise events as challenging, threatening, or intense (Dickerson and Kemeny 2004), and the perseverative cognition hypothesis, suggesting that individuals who engage in repetitive, intrusive thoughts (Brosschot et al. 2006), postulate that these negative cognitive tendencies will lead to a maladaptive physiological responses to stress.

The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and the autonomic nervous system (ANS) are two biological systems that are involved in an individual’s stress response. The ANS and HPA axis produce similar net effects, but accomplish these effects differently, highlighting the importance of examining different systems of stress response (e.g., Bauer et al. 2002). The sympathetic nervous system of the ANS responds quickly (Gunnar and Quevedo 2007) and activates the “fight-or-flight” response by increasing organ activity such as respiration and heart rate (Berntson et al. 1991) and counteracts the parasympathetic nervous system, which promotes organ activity when the body is at rest. The HPA axis signals the release of cortisol that is released into the blood-stream (see Gunnar and Quevedo 2007 for detailed review). The HPA axis is more slow-acting compared to the ANS due to a cascade of responses needed to activate the HPA system (Rudolph et al. 2011).

Importantly, a major function of these stress responses is to return the body to homeostasis after a stressful experience. Research on the relationship between biological stress responses and MDD has focused on both neuroendocrine regulation by assaying cortisol, the final hormone released following HPA axis response (Gunnar et al. 2009), and measures of ANS response through heart rate. In adults, numerous studies show that cortisol levels in depressed individuals take longer to return to baseline following stressor exposure than in controls (de Rooij et al. 2010). In younger samples, in addition to the association between depression and a higher cortisol awakening response (Vrshek-Schallhorn et al. 2013) and higher cortisol responses (Morris et al. 2012), a meta-analysis indicated that depressed youth had greater cortisol production (or less suppression) after a dexamethasone test, higher baseline cortisol, and an overactive response to psychological stressors (Lopez-Duran et al. 2009). In addition, research suggests that discrete measures of heart rate in response to stress are established and useful measures of ANS dysregulation associated with depression in adults and that heart rate responses to a stressor are associated with concurrent (Carroll et al. 2007) and prospective depressive symptoms (Phillips et al. 2011). Prior research also indicates that depressed youth have higher resting heart rates, a measure of ANS activity, compared to healthy adolescents (Byrne et al. 2010), and adolescents at risk for depression based on maternal history of depression had poorer heart rate recovery from a stressful task (Waugh et al. 2012).

Importantly, a meta-analysis by (Burke et al. 2005) examined differences in biological stress responses between depressed and non-depressed individuals. The results showed no differences between baseline and reactivity stress levels, but did find that depressed individuals had significantly higher cortisol levels during the recovery period compared to their non-depressed counterparts (Burke et al. 2005). Thus, an impaired ability to effectively regulate following a stressor has been most strongly associated with depression (Burke et al. 2005). Few studies use both cortisol and heart rate measures to study depression vulnerability (de Rooij et al. 2010), but including measures of different systems involved in the stress response can inform a more complete understanding of the interplay between cognitions and biological stress responses.

Hypotheses

Longstanding theories posit the inter-relationship between cognitive and biological responses to events (e.g., Lazarus and Folkman 1984). Previous research suggests that cognitions may amplify and maintain responses to stressors and delay recovery (Brosschot et al. 2006). Similar research also highlights the relationship between poorer recovery from a psychological stressor and depression in adults (Burke et al. 2005). Thus, a direct examination of whether cognitive responses to stress amplify the association between poor biological recovery from stressors and depressive symptoms in adolescence is warranted. Few studies have examined both biological and cognitive influences on stress responses together in relation to depression. Goodyer et al. (2000) found that both dysfunctional attitudes and differences in endocrine functioning were individually associated with prospective onset of MDD in adolescents, but they did not examine the interaction between these cognitive and biological vulnerabilities. More recently, Stewart et al. (2013) found an association between rumination and delayed cortisol recovery in depressed adolescents.

The current study examined whether cognitive vulnerabilities (negative cognitive styles and rumination) moderated the relationship between lower biological recovery from a stressor and depressive symptoms in adolescents. Based on appraisal theory (Dickerson and Kemeny 2004) and the perseverative cognition hypothesis (Brosschot et al. 2006), we hypothesized that the tendency to continually think about one’s dysphoric mood (rumination) and appraising the causes of negative events as global and stable (negative cognitive styles) would increase the link between poorer biological recovery from a stressor and depressive symptoms in adolescence. Additionally, we hypothesized that this interaction would be consistent for both the neuroendocrine and autonomic responses to stress.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Participants in the current study were drawn from a larger sample (N = 506) initially recruited from the Philadelphia area when they were 12–13 years old. Inclusion criteria for the broader study were: (1) the adolescent was 12 or 13 years old; (2) self-identified as Caucasian/White, African American/ Black, or Biracial, and (3) the mother was willing to participate. Exclusion criteria were: (1) lack of mother/primary caregiver, (2) not proficient in English, and (3) developmental impairments (see Alloy et al. 2012 for further recruitment information and inclusion/exclusion criteria).

Every 6 months, adolescents and their mothers were asked to come to the lab for assessment at a time that was convenient for them; at one of these assessments (Mean visit number = 5.69, SD = 1.43), the additional stress task was given. Participants were approached about the inclusion of this new task if they were scheduled for an assessment after 3:00 PM, and those who participated signed additional written consent (and assent). Previous research suggests that the time of day affects cortisol levels (Gunnar and Vazquez 2001); therefore, adolescents were only approached about the stress task after 3:00 PM (Mean = 5:07 PM) in order to standardize assessment times. No other inclusion or exclusion criteria were used. After consenting, participants were brought into the interview room. First, they were asked about common factors that influence biological responses to stress (Table 1) and then completed questionnaires until the baseline period was over and the additional stress task was given.

Table 1.

Covariation of variables affecting stress response

| Percent | Mean (SD) | Pearson correlation |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline cortisol | Baseline heart rate | |||

| Time of day (when arrived) | 4:42 PM (1:11 M) | −.22* | −.03 | |

| Demographic variables | ||||

| Age | 15.28 (1.00) | .14 | −.24** | |

| Caucasian | 47 | .05 | −.03 | |

| Body mass index | 23.53 (5.81) | −.12 | .13 | |

| Pubertal development scale | 16.03 (2.99) | −.05 | −.06 | |

| Female | 48 | −.21* | .15 | |

| Cycle Y/N | 44 | −.19* | .13 | |

| Days since last period | 19.04 (17.35) | .11 | −.01 | |

| Cycle regular | 86 | .01 | .05 | |

| Take birth control | 5 | .01 | .08 | |

| Intake information | ||||

| Regularly intake caffeine | 60 | .15 | .18 | |

| Caffeine today | 40 | .08 | .02 | |

| Minutes since last ate | 148.36 (126.15) | .12 | −.13 | |

| Health information | ||||

| Take any medication | 13 | −0.11 | −0.06 | |

| Take an SSRI | 3 | −0.04 | 0.09 | |

| Presence of mouth infection | 1.60 | −.03 | .03 | |

| Dx with asthma or allergies | 44 | −.07 | −.02 | |

| Take asthma medication | 23 | .02 | .06 | |

| Take allergy medication | 20 | −.13 | .09 | |

| Daily activities | ||||

| Average hours of sleep | 7.67 (1.52) | .02 | .02 | |

| Days feeling rested | 3.83 (2.45) | −.03 | −.02 | |

| Hours of sleep last night | 7.80 (1.77) | −.09 | −.08 | |

p < .05,

p < .01

The current study included 127 adolescents from the larger study: 49 % female, 47 % Caucasian, 53 % African American/Biracial and on average 15.28 years old (SD = 1 year) at the time of the stress task. All participants completed the Pubertal Development Scale (Petersen et al. 1988) as pubertal development may influence biological responses to stress (Shirtcliff et al. 2009). A series of independent samples t tests and a Chi square test were conducted to assess potential differences between the overall sample and the current study sample on demographics (gender, race, and family income). Participants in the current study did not differ from the overall sample based on gender (t = 1.072, p [ .05), race (t = 0.016, p [ .05), or income (χ2 = 10.39, p [ .05). In addition, 16 individuals who were approached for this study chose not to participate in the additional component. The majority of these 16 did not elect to participate in the current study because they did not have enough time to stay for the extra component (N = 12) and many asked to be approached at a future session. Comparison of demographic characteristics between those who participated and those who declined participation indicated no gender (t = 0.52, p [ .05), racial (t = 0.66, p [ .05), or income (χ2 = 8.11, p [ .05) differences. Some data were missing due to incomplete questionnaires or unusable biological samples. These numbers were relatively small for each measure, and thus, listwise deletion was used.

Measures

Biological Stress Response

Trier Social Stress Test (TSST; Kirschbaum et al. 1993)

The TSST is a widely used method to elicit a stress response (Gunnar et al. 2009). This task was modified for adolescents and included a speech and mental arithmetic component in front of an interviewer and video camera (See Appendix).

Biological Measurement

Saliva samples were collected with salivettes (Sarstedt AG & Co., Germany). Participants were instructed to put the salivette into their mouths for two minutes. While the salivette was collecting saliva, the participant’s ANS was assessed to obtain a multi-modal measurement of response to stress. The participant’s discrete heart rate was measured using an Omron BP785 cuff (Carroll et al. 2007). In addition, as a check on the subjective stressfulness at each time point, participants indicated how distressed they felt on a 10-point visual analog scale.

All saliva samples were labeled and stored frozen. Samples were assayed for cortisol using a cortisol enzyme immunoassay kit (Arbor Assays, Ann Arbor, MI) with intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation ranging from 6.0 to 14.7 % and 7.2 to 10.9 %, respectively. To minimize variability, all samples from each participant were assayed within the same assay batch and all samples were tested in duplicate. Duplicate test values were averaged to create the cortisol score for that time point, with values in picagrams per milliliter (pg/mL). Cortisol values that were returned below the minimum or above the maximum standard curve of comparison were re-run. If these cortisol samples did not have a readable value after they were re-analyzed, they subsequently were not used in analyses (n = 6).

Timing

Biological response to the TSST was assessed at four time points. Discrete measures of salivary cortisol and heart rate were measured at the end of the baseline (T1: M = 23.82 min after the participant was in the room, SD = 4.41 min; Range 20–38 min), heart rate was assessed immediately after the stressor (T2: M = 16.43, SD = 3.22 min after the baseline collection), heart rate and cortisol were assessed at 30 min (T3: M = 30.59 min, SD = 1.28 min) after the stressor, and cortisol was measured 60 min (T4: M = 60.74 min, SD = 2.89 min) after the stressor. Initial cortisol (T1: M = 1016.46 pg/mL, SD = 1070.06 pg/mL; Min = 202.00 pg/mL; Max 6170.80 pg/mL) and heart rate (T1: 74.70, SD = 11.43) were assessed after the baseline period. The ANS is much quicker to respond and recover from a stressor than is the neuroendocrine system. The cortisol collection times were based on meta-analytic findings indicating that peak cortisol response occurs 21–40 min following the onset of a stressor and that complete recovery occurs within 41–60 min after stressor offset (Dickerson and Kemeny 2004). Therefore, T3 (M = 944.47 pg/mL, SD = 1060.58 pg/ mL; Min = 200.92 pg/mL; Max = 6352.80 pg/mL) was aimed at assessing the peak cortisol stress response and T4 (M = 648.53 pg/mL SD = 674.51 pg/mL; Min = 150.00 pg/ mL; 4336.40 pg/mL) was aimed at assessing the cortisol recovery period. Heart rate at T2 (M = 74.31, SD = 11.20) was included to measure an individual’s quicker autonomic post-stress test activity and later heart rate recovery at T3 (M = 73.22, SD = 10.66).

Self-Report Questionnaires

Negative Cognitive Style

The Adolescent Cognitive Style Questionnaire (ACSQ; Hankin and Abramson 2002) Modified version (ACSQ-M; Alloy et al. 2012) presents the adolescent with 12 negative hypothetical events in achievement, interpersonal, and appearance domains, and asks the youth to make inferences about the causes (internal-external, stable-unstable, and global-specific), consequences, and self-worth implications of the hypothetical event. For each item, adolescents use 7-point Likert scales to rate the internality, stability, and globality of the cause of the event, the consequences of each event, and possible negative self-implications of the event. The ACSQ has demonstrated excellent internal consistency, good test– retest reliability and stability, a factor structure consistent with the hopelessness theory (Hankin and Abramson 2002), and good validity (Alloy et al. 2012). Scores on the ACSQ-M are summed with higher scores indicating a more negative cognitive style (Range: 49–251; M = 120.95, SD = 43.39). Internal consistency of the ACSQ-M was α = .96.

Rumination

The rumination subscale of the Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire (CRSQ; Abela et al. 2002) was used to assess a youth’s style of responding to sad moods. Adolescents are asked to rate what they usually do, not what they think they should do, when they feel sad. They respond on a scale of “Almost Never”, “Sometimes,” “Often” and “Almost Always.” Scores on the CRSQ are summed with higher scores indicating more rumination (Range: 13–52; M = 25.40, SD = 9.27). The CRSQ has demonstrated good validity in prior studies (Alloy et al. 2012) and an internal consistency of α = .93 in the current study.

Depressive Symptoms

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs 1985) is a self-report questionnaire that contains 27 items to assess affective, behavioral, and cognitive symptoms of depression in youth ages 7–17. Each item is rated on a scale from 0 to 2; items are summed for a total score (ranging from 0 to 54), with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms. The CDI has good reliability and validity (Klein et al. 2005). Internal consistency in the current sample was α = .87, with higher scores indicating more symptoms (Range: 0–40; M = 6.79, SD = 6.76).

Pubertal Development

The Pubertal Development Scale (PDS; Petersen et al. 1988) assesses pubertal development and was used to account for potential differences due to pubertal status. The PDS was used as a self and parent rated instrument that assess five characteristics of development that are rated on a 4-point scale with higher scores indicating more mature pubertal status. The PDS has good psychometric properties and convergent validity with physician-rated Tanner stages (Petersen et al. 1988). The parent and child scales were significantly correlated (r > .74) and an average score was used to determine whether puberty was associated with stress response.

Data Analysis

Consistent with prior studies assessing salivary cortisol, an examination of the raw cortisol data revealed that the distribution of residuals were leptokurtic and positively skewed. Therefore, log10 transformations were used to establish a more normal distribution prior to analyses and to be consistent with prior literature (Gunnar and Talge 2007). Consistent with the hypotheses, and prior studies (e.g., Harkness et al. 2011), cortisol recovery was defined as T3 minus T4 concentration (M = .13, SD = .20), with positive numbers indicating higher recovery. In addition, for heart rate, recovery was T2 minus T3 heart rate (M = 1.31; SD = 7.44), with positive numbers indicating higher recovery.

Examination of mean difference scores indicated an overall small biological response to the stressor. Similar to prior work, there was much variability in youths’ responses to the stressor (Gunnar et al. 2009). Whereas some participants evinced the expected biological increase and subsequent decrease following the TSST, some participants showed relatively no change, and others showed a decrease in biological levels.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

We first conducted a manipulation check to determine whether participants indicated distress. Overall, participants reported significantly higher levels of distress at post- than pre- TSST (t(127) = 10.21, p = .00, d = .78). Covariate analyses were conducted to examine demographic and individual characteristics that may influence the measures of stress response (see Table 1). Consistent with normative changes in daily cortisol levels, correlation analysis revealed that earlier start times of the TSST were related to higher baseline cortisol (r(121) = −.22, p < .05). In addition, gender was correlated (r(121) = −.21, p < .05) with baseline cortisol, such that girls had higher cortisol values than boys. Age was significantly related to baseline heart rate (r(120) = −.24, p < .01), with older participants exhibiting higher baseline heart rates than younger participants. Additional correlation analyses revealed that there were no associations between baseline cortisol and heart rate and the participants’ visit number (r(121) = .11 and .15 respectively). Based on the conventional scoring of the Pubertal Development Scale, all participants in the current sample had undergone puberty (PDS [ 2.5) to varying degrees (M = 16, SD 3; Petersen et al. 1988); however, pubertal development was not significantly associated with differences in baseline cortisol or heart rate. Finally, independent t-tests indicated that menarche status of the female participants did not significantly influence any of the biological measurements. Given that the majority of female participants reported that they had begun to have their menstrual cycle ([90 %), we decided to use gender as a covariate to capture the overall gender differences. Thus, time of day, gender, and age were used as covariates in step one of all analyses.

The bivariate correlations between all study variables are shown in Table 2. As expected, depressive symptoms were significantly correlated with the cognitive vulnerabilities, although the correlations were in the low-moderate range, suggesting these are distinct features. Negative cognitive style was significantly associated with rumination. The cognitive measures were not correlated with the biological measures of response. Interestingly, only heart rate recovery was correlated with depressive symptoms and the heart rate and cortisol measures of biological recovery were not associated with each other.

Table 2.

Correlation of main study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Depression symptoms | – | .38*** | .45*** | −.18* | −.04 |

| 2. Negative cognitive style | – | .36*** | −.08 | .04 | |

| 3. Rumination | – | −.09 | −.18 | ||

| 4. Heart rate recovery | – | −.03 | |||

| 5. Cortisol recovery | – | ||||

| Mean | 6.79 | 120.95 | 25.40 | −1.31 | 0.13 |

| SD | 6.76 | 43.49 | 9.27 | 7.47 | 0.19 |

Log Cortisol values are presented

p < .05,

** p < .01,

p < .001

Main Effects and Interaction of Cognitive Vulnerabilities and Biological Stress Recovery

A series of stepwise hierarchical linear regressions were conducted to examine the direct and interactive effects of the cognitive vulnerabilities and biological stress recovery and their association with depressive symptoms. In step 1, the covariates of time of day, gender, and age were entered. In step 2, either negative cognitive style or rumination and either heart rate or cortisol recovery were entered. Finally in step 3, the interaction between negative cognitive style or rumination with cortisol or heart rate recovery were added. The main predictor variables of cognitive vulnerability and biological stress recovery were mean centered (Aiken and West 1991).

As seen in Table 3, four regression models were conducted. The main effects revealed that neither heart rate recovery nor cortisol recovery were directly associated with depressive symptoms in step 2. However, a more negative cognitive style and higher levels of rumination were associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms. In addition, several regression analyses supported the hypothesis that the relationship between biological stress recovery and depressive symptoms was moderated by cognitive vulnerabilities, in that higher levels of cognitive vulnerability when combined with lower stress recovery, were associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms.

Table 3.

Interaction of cognitive vulnerabilities and stress recovery in association with depressive symptoms

| Dependent variable | Depressive symptoms |

Depressive symptoms |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV predictor | Negative cognitive style |

Rumination |

||||||

| b | S.E. | t | ΔR 2 | b | S.E. | t | ΔR 2 | |

| Heart rate recovery | .246 | .309 | ||||||

| Step 1 | .038 | .044 | ||||||

| Gender | 1.47 | 1.24 | 1.18 | 1.61 | 1.27 | 1.26 | ||

| Age | 0.95 | 0.53 | 1.80 | 1.02 | 0.54 | 1.88 | ||

| Time | −0.43 | 0.63 | 0.69 | −0.54 | 0.64 | 0.84 | ||

| Step 2 | .171 | .214 | ||||||

| Cognitive vulnerability (CV) | 0.58 | 0.13 | 4.46*** | 0.32 | 0.06 | 5.12*** | ||

| Heart rate recovery (HR) | 0.14 | 0.08 | 1.79 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 1.78 | ||

| Step 3 | .037 | .051 | ||||||

| CV × HR | −0.05 | 0.02 | 2.33* | −0.02 | 0.01 | 2.82** | ||

| Cortisol recovery | .223 | .225 | ||||||

| Step 1 | .030 | .007 | ||||||

| Gender | 1.82 | 1.28 | 1.42 | 1.97 | 1.32 | 1.48 | ||

| Age | 0.68 | 0.55 | 1.24 | 0.75 | 0.57 | 1.33 | ||

| Time | −0.11 | 0.66 | 0.17 | −0.23 | 0.68 | 0.34 | ||

| Step 2 | .158 | .187 | ||||||

| Cognitive vulnerability (CV) | 0.62 | 0.14 | 4.52*** | 0.34 | 0.07 | 4.95*** | ||

| Cortisol recovery (CR) | −0.23 | 0.32 | 0.72 | 0.12 | 0.32 | 0.36 | ||

| Step 3 | .036 | |||||||

| CV × CR | −0.18 | 0.08 | 2.20* | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.71 | .004 | |

All regression analyses included time of day, gender, and age as covariates in step 1. For ease of presentation covariates were excluded from the table. In addition, R2 of the baseline model and interaction model were included. D indicates a change in R2 due to the inclusion of the interaction term

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

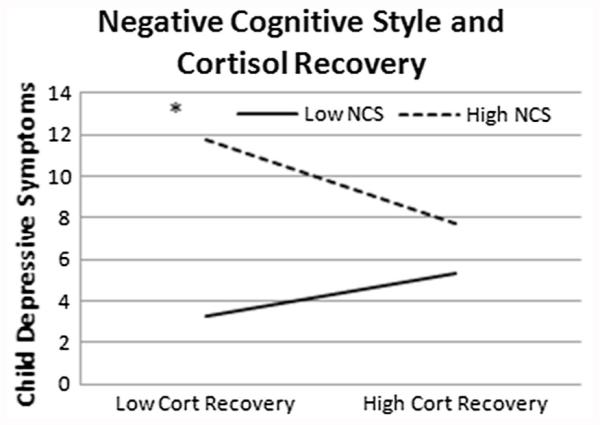

As seen in Fig. 1, a negative cognitive style moderated the relationship between cortisol recovery and depressive symptoms (b = −.18, SE = .08, t(6,106) = 2.20, p = .03, ΔR2 = .04), such that lower cortisol recovery was related to higher levels of depressive symptoms when adolescents exhibited a more negative cognitive style. To examine the form of the interaction, follow-up analyses examined the simple slopes of the interaction at one standard deviation above and below the centered mean (Aiken and West 1991). The slope was significant for high negative cognitive style (b = −11.04, SE = 5.05, t(6,106) = 2.19, p = .03, CI: −21.06; −1.03), but not low negative cognitive style (b = 4.76, SE = 4.44, t(6,106) = 1.07, p = .29, CI: −4.06; 13.57).

Fig. 1.

All figures represent data from 1 standard deviation above and below the mean

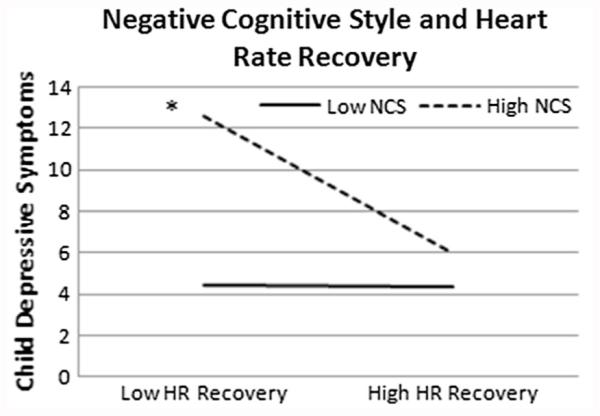

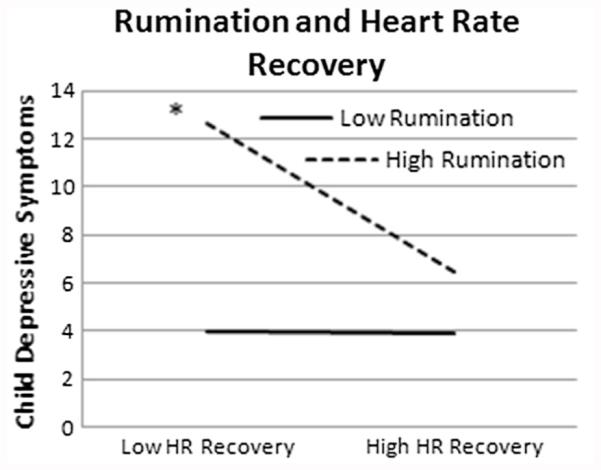

In addition, as seen in Figs. 2 and 3, cognitive vulnerabilities moderated the relationship between heart rate recovery and depressive symptoms, such that lower heart rate recovery was related to higher levels of depressive symptoms when there were higher cognitive vulnerabilities. As seen in Fig. 2, negative cognitive style moderated the relationship between heart rate recovery and depressive symptoms (b = −.005, SE = .002, t(6,111) = 2.33, p = .02, ΔR2 = .04). Follow-up analyses revealed that the slope was significant for high negative cognitive style (b = −.41, SE = .14, t(6,111) = 2.94, p = .00, CI: −.68; −.13), but not low negative cognitive style (b = .01, SE = .09, t(6,111) = .08, p = .94, CI: −.18; .19). As seen in Fig. 3, rumination moderated the relationship between heart rate recovery and depressive symptoms (b = −.02, SE = .01, t(6,107) = 2.82, p = .00, ΔR2 = .05). Followup analyses revealed that the slope was significant for high levels of rumination (b = −.41, SE = .12, t(6,111) = 3.36, p = .00, CI: −.66; −.17), but not low levels of rumination (b = .02, SE = .09, t(6,111) = .22, p = .82, CI:-.16; .20).1

Fig. 2.

All figures represent data from 1 standard deviation above and below the mean

Fig. 3.

All figures represent data from 1 standard deviation above and below the mean

Taken together, the findings suggested that individuals with higher levels of negative cognitive style and rumination and a lower ability to recover post stressor had higher levels of depressive symptoms. As seen in Table 3, the effect sizes of the overall models fell in the low medium range, with the largest effect size for the models with interactions between heart rate recovery and rumination (R2 = .31), and the lowest effect size for the cortisol recovery and negative cognitive style interaction model (R2 = .22). Additionally, the changes in effect sizes when the interaction term was included were small but significant, with the interaction of negative cognitive style and cortisol recovery (ΔR2 = .04) at the low end and the interaction of heart rate recovery and rumination (ΔR2 = .05) at the high end.

Discussion

The primary aim of the current study was to examine whether cognitive vulnerabilities increase the association between poor biological stress recovery and depressive symptoms in adolescence. Poor biological recovery has been linked consistently to adult depression (Burke et al. 2005); however, less research has examined this in adolescence and examined factors that may increase this association. Linking cognitive and biological aspects of reactivity to stress is integral to more fully understanding factors associated with the onset and maintenance of depression. Importantly, this study examined these factors in the pivotal developmental period of adolescence, when changes in responses to stressful life events (Romeo 2013) and the onset of depression (Hankin et al. 1998) occur. As expected, in this community sample of adolescents, results showed that adolescents with higher levels of cognitive vulnerability and lower biological stress recovery had higher concurrent depressive symptoms. Moreover, both rumination and negative cognitive style in interaction with either autonomic or endocrine system recovery showed associations with depressive symptoms, such that adolescents’ maladaptive cognitive styles amplified the association between lower stress recovery and higher depressive symptoms. The overall effect sizes generally fell in the low medium range, suggesting these factors explain a moderate portion of variance in depressive symptoms.

These findings are consistent with recent reviews evaluating the importance of understanding physiological responses to stress, and highlight the impact of an individual’s interpretation or appraisal of events in modulating the biological reaction to stressors (Denson et al. 2009a, b). In line with this appraisal theory, the perseverative cognition hypothesis (Brosschot et al. 2006) suggests that repetitive, intrusive thoughts may amplify, maintain, or reactivate physiological responses to stress. Recent research examining this relationship has focused on rumination and stress reactivity (Zoccola and Dickerson 2012) and has found that higher levels of rumination predicted greater increases in the cortisol awakening response (Zoccola et al. 2011) and cortisol reactivity to a psychosocial laboratory stressor (Denson et al. 2009a, b). The findings from the current study extend this research by showing that other cognitive vulnerabilities interact with biological response, as well as showing that a lower recovery may maintain or exacerbate the negative effects of stress. These findings were robust to the specific type of biological recovery system and suggest possible coherence between the effects of a maladaptive autonomic and endocrine recovery to stressful events. Cognitive and biological aspects of stress response demonstrate a synergistic association with depression and may be an important target for future research and intervention.

These findings are also consistent with biological models of depression (Holsboer 2000). As discussed, research has found consistent associations between HPA dysregulation and MDD. The dexamethasone test is an established measure to detect functional alterations in the HPA system and has been used to determine how the HPA system is related to depression (Ising et al. 2005). After administration, individuals with a normal functioning HPA axis will suppress the excretion of cortisol (reduced levels) because this drug binds to the receptor sites that inhibit its production. Researchers have found that some people with MDD do not effectively suppress cortisol after administration (Holsboer 1983). This research highlights that the HPA dysregulation occurs at the glucocorticoid receptors (GR), which inhibit the further secretion of cortisol. That is, MDD is associated with reduction in the efficiency of GR and the negative feedback and recovery of the stress system (Ising et al. 2005). Indeed, researchers have suggested that treatment for depression, using antidepressants, primarily stabilizes mood through acting on the HPA system directly (Barden et al. 1995) and may be a good indicator for treatment response (Ising et al. 2005). The current findings show that cognitive vulnerabilities amplify the association between a lower recovery of the stress system and depressive symptoms. That is, if an individual continually re-experiences a negative event (i.e., via rumination) or finds it to lead to hopeless thoughts (via negative attributions and inferences), and is not able to physically regulate their response to the event, then he or she is at a heightened risk for maladaptive outcomes. The current findings suggest that the interactive combination of cognitive and biological vulnerabilities for depression may be particularly pernicious.

Prior research highlights different mechanisms through which the autonomic nervous system reacts to acute stress (Brindle et al. 2014). The current study focused on discrete measures of heart rate in post stress activity and later recovery to a social stressor, which has been found to be a useful indicator of dysregulation affecting the ANS in association with depression (e.g., Carroll et al. 2007). However, continuous measures of heart rate would be useful in assessing metrics such as vagal withdrawal using heart rate variability and respiratory sinus arrhythmia in future studies. Indeed, although many researchers focus on the sympathetic branch of the ANS, others suggest the parasympathetic response is equally important (Grossman et al. 1996). A recent meta-analysis found that sympathetic activation and vagal withdrawal contribute relatively equally to cardiovascular reactivity to stress (Brindle et al. 2014). Heart rate was the only measure of ANS activity in the current study; including additional measures would be helpful in differentiating between the parasympathetic and sympathetic stress response as there may be a reciprocal relationship between these two systems (Berntson et al. 1991). Further, there is some research that suggests that heart rate increase is primarily activated through the vagal system when threat is detected, whereas sympathetic activation only occurs at more intense levels of stress (e.g., Yamamoto et al. 1991). This suggests that the type of stressor may differentially impact biological systems. Indeed, social evaluative threat paradigms such as the TSST are consistently associated with a stress response in youth and adults (Gunnar et al. 2009). This study used a modified TSST to target social evaluation, uncontrollability, and unpredictability; however, there was variability in biological response. Including a paradigm that is longer in duration and involves more judges may have led to increased biological response in more youth (Gunnar et al. 2009).

The findings from the current study should be interpreted through the lens of several strengths and limitations. The current study included adolescents from a community sample of diverse racial and economic backgrounds. A non-clinical sample enhances the generalizability of the findings and extends prior studies that have focused on comparisons of selected individuals based on psychopathology or specific maladaptive vulnerabilities. Importantly, the majority of prior studies have examined stress response using only measures of cortisol; thus, the current study provides an important advance by allowing for the comparison of responses in the autonomic and endocrine systems.

The present findings, however, also must be interpreted within the context of the study’s limitations. Although this study included a rigorous measurement of biological stress response, similar to other studies, it relied upon self-report questionnaires for examining cognitive vulnerabilities and depressive symptoms, which are subject to reporter bias. The use of clinician rated symptoms of depression and implicit measures of cognitive bias in future studies may be helpful to disentangle subjective reporter bias (Monroe and Reid 2009). Additionally, the measurement timing chosen has limitations as individuals may vary in their time to peak physiological response and subsequent recovery. The mean response scores for both cortisol and heart rate were relatively stable, which indicates that there was much individual variability in initial response to the stressor and this may have impacted results targeted at the response component. As heart rate was not measured continuously throughout the stressor, the timing of the second assessment of heart rate may not capture peak response, as the ANS recovers quickly to stressful events. Gunnar et al. (2009) reviewed factors that may influence differences in response including the duration of the baseline, the intensity and type of the stressor, and other individual differences, which may have influenced the results and should be taken into account. For example, early childhood maltreatment may influence the initial response to stress (Harkness et al. 2011) and should be taken into account in further research. Additional time points of measuring stress response and recovery can help reduce the potential impact of these differences. The data presented are also crosssectional in nature and cannot speak to causal implications. Prospective data may be more suggestive that the interaction between biological and cogntive factors predict increases in depressive symptoms or the onset of depressive episodes. Finally, although depressive symptoms during adolescence have been shown to be associated with episodes in adulthood (Wesselhoeft et al. 2013), it will be beneficial to examine depressive episodes in future studies.

Despite some limitations, the current study provides an important methodological and theoretical advancement in the literature examining factors associated with depression and stress response in adolescence. From the evidence presented, it appears that cognitive and biological aspects of stress response may operate synergistically in the development of depression and that maladaptive cognitive styles may amplify the negative effects of a lack of physiological recovery to a stressor. General theories of the relationship between these systems have begun to integrate these factors (Denson et al. 2009a, b). Importantly, the relationships between maladaptive responses to stress are complex, and research and theoretical models are still needed to help elucidate the processes that may lead to the development of depression.

Although the current study examined non-treatment seeking adolescents and reports moderate effect sizes, research examining these processes may have implications for clinical treatment. Personalized treatment is underway to compare the effects of medicine and psychotherapy (Cuijpers et al. 2012), yet this same model also can compare the effects of treating different aspects of stress reactivity. Evidence from this study suggests that clinicians may choose to assess both cognitive styles and physiological regulation. Medication trials have begun to examine the efficacy of antidepressants on the HPA system directly and have shown that some are effective in reducing HPA response to stressors in adults (Sarubin et al. 2014). These medications may be particularly effective in individuals with combined cognitive vulnerability and low cortisol recovery compared to medications that do not alter HPA response. Future research should examine whether alterations in the biological stress response is the mechanism through which antidepressants impact depression. If so, this may allow for treatment decision-making in the use of antidepressants with individuals with lower stress recovery. In addition, clinicians may bolster a youth’s coping strategies for responding to stress by the utilization of skills such as cognitive reappraisals and mindfulness techniques to regulate physiological responses (Compas 1987). Previous research highlights cognitive reappraisal as an important skill to cognitively regulate one’s emotions (Lam et al. 2009). Approaches that incorporate mindfulness and relaxation strategies may be particularly relevant to the regulation of physiological reactivity to stress. Additionally, recent research suggests the importance of implementing interventions that consider the unique and potentially beneficial role of exposure to stress, such as Stress Inoculation Training, which may help individuals cope with stressful events as well as “inoculate” individuals to future stressors (Meichenbaum and Deffenbacher 1996). Taken together, although the current study is unable to draw strong conclusions about the need for changes in intervention strategies, it highlights the relationship between two known vulnerabilities for depression that have been targeted individually in treatment studies in the past. Further research is needed to determine whether targeting both in a combined manner leads to enhanced benefit.

Conclusion

The current study provides a more nuanced understanding of the interaction between cognitive and biological stress responses in association with depressive symptoms in adolescence. Adolescence is a developmental period with a number of important transitions (Steinberg and Morris 2001) and dramatic increases in rates of psychopathology (Kessler et al. 2001). In parallel, changes in responses to stress occur during adolescence (Romeo 2010), making this an essential period to study in order to develop effective intervention or prevention strategies. Prior research has found support for the interrelationship between cognitive styles and biological recovery from stress (Denson et al. 2009a, b), yet has not previously examined the combined role of these stress response systems in association with depression symptoms. The current study found that both ruminative thoughts and negative cognitive styles amplified the association between poor biological recovery from a social stressor, as assessed by cortisol and heart rate, and depressive symptoms, thus, establishing a connection between these two known risk factors for the onset of depression. It will be important for future work to examine the developmental trajectories of these stress reactivity components over time to predict episodes of depression during this developmentally salient period.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grants MH79369 and MH101168 to Lauren B. Alloy and MH099764 to Benjamin G. Shapero.

Biographies

Benjamin G. Shapero, Ph.D. completed his doctoral work in the Department of Psychology at Temple University and is currently a Clinical Fellow in the Department of Psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital. His research interests include cognitive, biological, and environmental factors involved in mood disorders, particularly vulnerability-stress models of depression and bipolar disorders and various stress processes that contribute to the development and course of mental illness.

George McClung, B.S is currently a student in the Veterinary School at the University of Pennsylvania. He was previously the research technician of Dr. Bangasser’s Neuroendocrinology and Behavior Laboratory in the Brain and Cognitive Sciences Program at Temple University.

Debra A. Bangasser, Ph.D is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology and Brain and Cognitive Sciences Program at Temple University. Her research program investigates neurobiological factors that contribute to sex differences in stress responses and predispose females to stress-related psychiatric disorders.

Lyn Y. Abramson, Ph.D. is the Sigmund Freud Professor of Psychology in the Psychology Department at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her research interests include the cognitive, psychosocial, biological, and developmental processes in the onset, course, and intervention of unipolar depression and bipolar disorder.

Lauren B. Alloy, Ph.D. is Laura H. Carnell Professor and Joselph Wolpe Distinguished Faculty in the Department of Psychology at Temple University and is currently the Director of Clinical Training for the Temple Clinical Psychology Ph.D. program. Her major research interests are in understanding the cognitive, developmental, psychosocial, and biological mechanisms involved in the onset, course, and treatment of unipolar depression and bipolar disorder.

Appendix: Additional Information Regarding the TSST

The TSST was chosen as a stress procedure because it has been shown to be particularly effective in eliciting a stress response in adolescents and is less invasive (e.g., physical examination, inoculation, venipuncture) and more feasible (e.g., peer rejection paradigm, parent–child conflict discussion) than other paradigms. After a 30 min baseline period, in which participants completed the consent forms and other measures in this study, participants were given instructions for the task. In addition, adolescents were told that an expert panel of judges would rate their performance and that those who performed the best would get a prize. They received 5 min to prepare their speech while alone in the room. Following the 5 min preparation time, the interviewer came back into the room and read a condensed portion of the instructions for the job interview speech. Participants were asked to stand, face the camera, and were prompted to speak for 2 min. In addition, the interviewer sat in the room with a clipboard during the TSST and was instructed to maintain a neutral expression. Standardized prompts were given to the participants if there were long pauses (e.g., 20 s), such as “You still have time remaining, please continue.” After the two min speech, the participants were prompted to stop but remain standing. An unexpected additional task was then introduced as participants were asked to solve a calculation task aloud. They were asked to count backwards from 2083 to zero in 13-step sequences. They were instructed to calculate as quickly and correctly as possible and if they made a mistake, the interviewer would say “error, 2083” and were asked to start over. They were not instructed on the duration of this task but after they began, participants completed this task for 1 min. All portions of the TSST were videotaped. Following this task, participants were told that the new task was completed and continued to complete other study measures in the remaining time of the regular assessment. At the end of the day’s session, participants and their mothers were debriefed on the study protocol.

Footnotes

Thirteen participants met DSM-IV criteria for past major depressive episode. Bivariate correlations were run to examine whether this determination was associated with any study variables. History of MDD was associated with baseline cortisol (r = −.21, p = .024). Sensitivity analyses were run to determine whether including history of MDD as a covariate changed the results. Sensitivity analysis confirmed the prior findings and suggested that the presence of a history of MDD did not alter the results of the current study. However, it is important to note that a history of MDD was associated with lower baseline cortisol.

Authors’ Contributions BGS conceived of the study, obtained funding, collected the data, performed statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript; GM analyzed the biological data and drafted a section of the manuscript; DB participated in the design of the study, oversaw the biological analysis and helped draft and review the manuscript; LYA obtained funding for the original study and helped review the manuscript; LBA participated in the design and coordination of the study, obtained the funding for the original study, and reviewed multiple drafts of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest The authors Benjamin G. Shapero, George McClung, Debra A. Bangasser, Lyn Y. Abramson, and Lauren B. Alloy declare that they have no conflict of interest or other financial disclosures. This manuscript presents findings that have not been previously published or submitted elsewhere.

Ethical Approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Abela JRZ, Brozina K, Haigh EP. An examination of the response styles theory of depression in third- and seventh-grade children: A short-term longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:515–527. doi: 10.1023/a:1019873015594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramson LY, Metalsky GI, Alloy LB. Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review. 1989;96:358–372. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. SAGE Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Whitehouse WG, Hogan ME, Panzarella C, Rose DT. Prospective incidence of first onsets and recurrences of depression in individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. Journal Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:145–156. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Black SK, Young ME, et al. Cognitive vulnerabilities and depression versus other psychopathology symptoms and diagnoses in early adolescence. Journal Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2012;41:539–560. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.703123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barden N, Reul JMHM, Holsboer F. Do antidepressants stabilize mood through actions on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical system? Trends in Neuroscience. 1995;18:6–11. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93942-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer AM, Quas JA, Boyce WT. Associations between physiological reactivity and children’s behavior: Advantages of a multisystem approach. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2002;23:102–113. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200204000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntson GG, Cacioppo JT, Quigley KS. Autonomic determinism: The modes of autonomic control, the doctrine of autonomic space, and the laws of autonomic constraint. Psychological Review. 1991;98:459–487. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.98.4.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brindle RC, Ginty AT, Phillips AC, Carroll D. A tale of two mechanisms: a meta-analytic approach toward understanding the autonomic basis of cardiovascular reactivity to acute psychological stress. Psychophysiology. 2014;51:964–976. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosschot JF, Gerin W, Thayer JF. The perseverative cognition hypothesis: A review of worry, prolonged stress-related physiological activation, and health. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2006;60:113–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.06.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke HM, Davis MC, Otte C, Mohr DC. Depression and cortisol responses to psychological stress: A meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:846–856. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne ML, Sheeber L, Simmons JG, et al. Autonomic cardiac control in depressed adolescents. Depression and Anxiety. 2010;27:1050–1056. doi: 10.1002/da.20717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll D, Phillips AC, Hunt K, Der G. Symptoms of depression and cardiovascular reactions to acute psychological stress: evidence from a population study. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;75:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:393–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, Reynolds CF, Donker T, Li J, Andersson G, Beekman A. Personalized treatment of adult depression: Medication, psychotherapy, or both? A systematic review. Depression and Anxiety. 2012;29:855–864. doi: 10.1002/da.21985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rooij SR, Schene AH, Phillips DI, Roseboom TJ. Depression and anxiety: Associations with biological and perceived stress reactivity to a psychological stress protocol in a middle-aged population. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35:866–877. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denson TF, Fabiansson EC, Creswell JD, Pedersen WC. Experimental effects of rumination styles on salivary cortisol responses. Motivation and Emotion. 2009a;33:42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Denson TF, Spanovic M, Miller N. Cognitive appraisals and emotions predict cortisol and immune responses: a meta-analysis of acute laboratory social stressors and emotion inductions. Psychological Bulletin. 2009b;135:823–853. doi: 10.1037/a0016909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson SS, Kemeny ME. Acute stressors and cortisol responses: a theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:355–391. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodyer IM, Herbert J, Tamplin A, Altham PM. First-episode major depression in adolescents: Affective, cognitive and endocrine characteristics of risk status and predictors of onset. British Journal Psychiatry. 2000;176:142–149. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman P, Watkins LL, Wilhelm FH, Manolakis D, Lown B. Cardiac vagal control and dynamic responses to psychological stress among patients with coronary artery disease. American Journal of Cardiology. 1996;78:1424–1427. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)89295-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Quevedo K. The neurobiology of stress and development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:145–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Talge NM. Neuroendocrine measures in developmental research. In: Schmidt LA, Segalowitz SJ, editors. Developmental psychophysiology: theory, systems, and methods. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2007. pp. 343–366. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Talge NM, Herrera A. Stressor paradigms in developmental studies: What does and does not work to produce mean increases in salivary cortisol. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:953–967. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Vazquez DM. Low cortisol and a flattening of expected daytime rhythm: potential indices of risk in human development. Developmental Psychopathology. 2001;13:515–538. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401003066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Measuring cognitive vulnerability to depression in adolescence: Reliability, validity, and gender differences. Journal Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:491–504. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3104_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:128–140. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness KL, Stewart JG, Wynne-Edwards KE. Cortisol reactivity to social stress in adolescents: role of depression severity and child maltreatment. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36:173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holsboer F. Prediction of clinical course by dexamethasone suppression test (DST) response in depressed patients-physiological and clinical construct validity of the DST. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1983;16:186–191. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1019496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holsboer F. The corticosteroid receptor hypothesis of depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23:477–501. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ising M, Künzel HE, Binder EB, Nickel T, Modell S, Holsboer F. The combined dexamethasone/CRH test as a potential surrogate marker in depression. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2005;29:1085–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Merikangas K. Mood disorders in children and adolescents: An epidemiologic perspective. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49:1002–1014. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Pirke KM, Hellhammer DH. The trier social stress test—a tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology. 1993;28:76–81. doi: 10.1159/000119004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Dougherty LR, Olino TM. Toward guidelines for evidence-based assessment of depression in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:412–432. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3403_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The Children’s depression, inventory (CDI) Psychopharmacological Bulletin. 1985;21:995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam S, Dickerson SS, Zoccola PM, Zaldivar F. Emotion regulation and cortisol reactivity to a social-evaluative speech task. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:1355–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Duran NL, Kovacs M, George CJ. Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis dysregulation in depressed children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:1272–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meichenbaum D, Deffenbacher JL. Stress inoculation training for coping with stressors. Clinical Psychology. 1996;49:4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Michl LC, McLaughlin KA, Shepherd K, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination as a mechanism linking stressful life events to symptoms of depression and anxiety: Longitudinal evidence in early adolescents and adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:339–352. doi: 10.1037/a0031994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM, Reid MW. Life stress and major depression. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009;18:68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM, Simons AD. Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: Implications for the depressive disorders. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:406–425. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.3.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris MC, Rao U, Garber J. Cortisol responses to psychosocial stress predict depression trajectories: Social-evaluative threat and prior depressive episodes as moderators. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;143:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.05.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naicker K, Galambos NL, Zeng Y, Senthilselvan A, Colmon I. Social, demographic, and health outcomes in the 10 years following adolescent depression. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;42:533–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:569–582. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen A, Crockett L, Richards M, Boxer A. A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1988;17:117–133. doi: 10.1007/BF01537962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips AC, Hunt K, Der G, Carroll D. Blunted cardiac reactions to acute psychological stress predict symptoms of depression five years later: Evidence from a large community study. Psychophysiology. 2011;48:142–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2010.01045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo RD. Adolescence: A central event in shaping stress reactivity. Developmental Psychobiology. 2010;52:244–253. doi: 10.1002/dev.20437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo RD. The teenage brain: The stress response and the adolescent brain. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2013;22:140–145. doi: 10.1177/0963721413475445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Troop-Gordon W, Granger D. Individual differences in biological stress responses moderate the contribution of early peer victimization to subsequent depressive symptoms. Psychopharmacology. 2011;214:209–219. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1879-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarubin N, Nothdurfter C, Schmotz C, et al. Impact on cortisol and antidepressant efficacy of quetiapine and escitalopram in depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;39:141–151. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirtcliff EA, Dahl RE, Pollack SD. Pubertal development: Correspondence between hormonal and physical development. Child Developmental. 2009;80:327–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. Heightened stress responsivity and emotional reactivity during pubertal maturation: Implications for psychopathology. Developmental Psychopathology. 2009;21:87–97. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Morris AS. Adolescent development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:83–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JG, Mazurka R, Bond L, Wynee-Edwards KE, Harkness KL. Rumination and impaired cortisol recovery following a social stressor in adolescent depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013;41:1015–1026. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9740-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrshek-Schallhorn S, Doane LD, Sinbarg RW, Craske MG, Adam EK. The cortisol awakening response predicts major depression: Predictive stability over a 4-year follow-up and effect of depression history. Psychological Medicine. 2013;43:483–493. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waugh CE, Muhtadie L, Thompson RJ, Joorman J, Gotlib IH. Affective and physiological responses to stress in girls at risk for depression. Developmental Pychopathology. 2012;24:661–675. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesselhoeft R, Sorensen MJ, Heiervang ER, Bilenberg N. Subthreshold depression in children and adolescents—a systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;151:7–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Hughson RL, Peterson JC. Autonomic control of heart rate during exercise studied by heart rate variability spectral analysis. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1991;71:1136–1142. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.3.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoccola PM, Dickerson SS. Assessing the relationship between rumination and cortisol: A review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2012;73:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoccola PM, Dickerson SS, Yim IS. Trait and state perseverative cognition and the cortisol awakening response. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36:592–595. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]