Abstract

Superoxide dismutases (SODs) are critical antioxidant enzymes that protect organisms from reactive oxygen species (ROS) caused by adverse conditions, and have been widely found in the cytoplasm, chloroplasts, and mitochondria of eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells. Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) is an important economic crop and is cultivated worldwide. However, abiotic and biotic stresses severely hinder growth and development of the plant, which affects the production and quality of the crop. To reveal the potential roles of SOD genes under various stresses, we performed a systematic analysis of the tomato SOD gene family and analyzed the expression patterns of SlSOD genes in response to abiotic stresses at the whole-genome level. The characteristics of the SlSOD gene family were determined by analyzing gene structure, conserved motifs, chromosomal distribution, phylogenetic relationships, and expression patterns. We determined that there are at least nine SOD genes in tomato, including four Cu/ZnSODs, three FeSODs, and one MnSOD, and they are unevenly distributed on 12 chromosomes. Phylogenetic analyses of SOD genes from tomato and other plant species were separated into two groups with a high bootstrap value, indicating that these SOD genes were present before the monocot-dicot split. Additionally, many cis-elements that respond to different stresses were found in the promoters of nine SlSOD genes. Gene expression analysis based on RNA-seq data showed that most genes were expressed in all tested tissues, with the exception of SlSOD6 and SlSOD8, which were only expressed in young fruits. Microarray data analysis showed that most members of the SlSOD gene family were altered under salt- and drought-stress conditions. This genome-wide analysis of SlSOD genes helps to clarify the function of SlSOD genes under different stress conditions and provides information to aid in further understanding the evolutionary relationships of SOD genes in plants.

Keywords: tomato, superoxide dismutase, SOD gene family, promoter, abiotic stress, gene expression

Introduction

It is well known that toxic free radicals caused by environmental stresses such as cold, drought, and water-logging are great challenges for crop production (Mittler and Blumwald, 2010). Among them are reactive oxygen species (ROS), toxic free radicals produced in plant cells in response to stress, which can damage membranes, oxidize proteins, and cause DNA lesions (Sun et al., 2007; Wang and Prabakaran, 2011; Feng et al., 2015). However, in the process of evolution, plants have developed defense mechanisms to alleviate the damage caused by adverse environmental conditions. For example, some well-known ROS-scavenging enzymes can defend plants against environmental stress by controlling the expression of enzyme responsive family genes, including superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase (GPX), and peroxiredoxin (PrxR) (Mittler et al., 2004; Filiz and Tombuloğlu, 2014).

Superoxide dismutases, a group of metalloenzymes, were first found in bovine erythrocytes in Mann and Keilin (1938). Subsequently, they were also described in bacteria, higher plants, and vertebrates (Rabinowitch and Sklan, 1980; Tepperman and Dunsmuir, 1990; Kim et al., 1996; Zelko et al., 2002). McCord and Fridovich (1969), researchers found that SODs can catalyze the dismutation of the superoxide to O2 and H2O2 (Tepperman and Dunsmuir, 1990). In plants, SODs have been detected in roots, leaves, fruits, and seeds (Giannopolitis and Ries, 1977; Tepperman and Dunsmuir, 1990), where they provide basic protection to cells against oxidative stress.

Based on their metal cofactors, protein folds, and subcellular distribution, SODs are mainly categorized as Cu/ZnSODs, FeSODs, and MnSODs (Alscher and Erturk, 2002; Molina-Rueda et al., 2013; Filiz and Tombuloğlu, 2014; Feng et al., 2015). Cu/ZnSODs can be found in prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms, were first isolated from Photobacterium leiognathi in Puget and Michelson (1974; Deshazer et al., 1994), and are present in the cytoplasm, chloroplasts, and/or the extracellular space in plant cells (Pilon et al., 2011). In mammalian cells, the molecular weight of Cu/ZnSODs is about 32 kDa, and they can be found in cytoplasm, nuclear compartments, and lysosomes (Chang et al., 1988; Keller et al., 1991; Crapo et al., 1992; Liou et al., 1993). FeSODs have been found in plant chloroplasts and cytoplasm (Moran et al., 2003; Miller, 2012). MnSODs, widely present in all major kingdoms, have been observed in eukaryotic mitochondria (Lynch and Kuramitsu, 2000) and can protect mitochondria by scavenging ROS (Moller, 2001). MnSODs also play an important role in promoting cellular differentiation (Wispé et al., 1992; Clair et al., 1994). In addition, a new type of SOD, NiSOD, has been reported in Streptomyces (Youn et al., 1996). However, no evidence for NiSOD has been found in plants (Felisa et al., 2005).

In recent years, some studies have reported that SODs can protect plants against abiotic and biotic stresses, such as heat, cold, drought, salinity, abscisic acid and ethylene (Wang et al., 2004; Pilon et al., 2011; Asensio et al., 2012; Feng et al., 2015). Under various environmental stress conditions, researchers have found that different types of SOD genes have different expression patterns. For example, under drought stress, expression patterns of banana genes MaMSD1A and MaCSD1B were completely opposite to one another (Feng et al., 2015). Moreover, SODs with the same metal cofactor did not always play the same role in different species. For example, while we found that expression of MnSODs was not altered under oxidative stress conditions in Arabidopsis, researchers found that MnSOD expressions were changed significantly under salt stress in pea and cold and drought stresses in wheat (Gómez et al., 1999; Wu et al., 1999; Baek and Skinner, 2003). These results show that different SOD genes have different expression patterns in plants in response to diverse environmental stresses. Additionally, researchers have also found that alternative splicing and miRNAs may participate in the regulation of SOD expression (Srivastava et al., 2009; Lu et al., 2011). To date, the SOD gene family has been described in many plant species, including Arabidopsis thaliana, Musa acuminata, Sorghum bicolor, and Populus trichocarpa (Kliebenstein and Last, 1998; Molina-Rueda et al., 2013; Filiz and Tombuloğlu, 2014; Feng et al., 2015).

Tomato is not only an important staple and economic crop, but also plays a vital role as an experimental model plant (Mueller et al., 2005). In previous studies, two SOD-coding cDNA sequences isolated from tomato leaves were identified as Cu/ZnSOD genes and were found to be distributed on different chromosomes (Perl-Treves et al., 1990, 1988). Subsequently, the expression levels of two Cu/ZnSOD genes in tomato organs during leaf growth and fruit ripening were reported (Perl-Treves and Galun, 1991). Further, Perl et al. (1993) found that over-expression of Cu/ZnSODs in potato showed that transgenic plants exhibited increased tolerance to oxidative stress. Recently, great efforts have been made to explore the roles of SOD genes in improving tomato tolerance to various environmental stresses, such as heat, salt, drought, cold, and bacteria (Mazorra et al., 2002; Li, 2009; Sasidharan et al., 2013; Soydam et al., 2013; Aydin et al., 2014). In addition, several recent studies have indicated that SOD played an important role of hormone and insecticide stresses. For example, Bernal et al. (2009) detected that the expression level of cytosolic Cu/Zn-SOD was increased after 1 day of auxin treatment for tomato. Chahid et al. (2015) studied the activity of SOD in tomato in response to xenobiotics stresses such as alpha-cypermethrin, chlorpyriphos, and pirimicarb. As described above, SOD gene families have been widely implicated in responses to abiotic and biotic stresses in tomato. However, these studies have mainly concentrated on the expression of a single form of SOD enzyme and on changes in the enzymatic antioxidant system under various environmental stresses, and little has been reported on the SOD gene family in tomato.

To comprehensively understand the putative roles of SOD genes in tomato, a systematic analysis of the SOD gene family was necessary at the whole-genome level. Recently, the whole-genome sequence of tomato was made available, which provided opportunities for analyzing the expression patterns and regulation mechanisms of the tomato SOD (SlSOD) gene family in response to environment stresses. Hence, the objectives of this study were (i) to identify the SOD gene family in tomato; (ii) to analyze gene structure, duplication and expression patterns in different tomato tissues; (iii) to illustrate chromosomal locations and phylogenetic relationships with SODs from other plants; and (iv) to reveal the regulating mechanisms of the SlSOD gene family under abiotic (salt and drought) stress by using real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR).

Materials and Methods

Identification of SOD Genes in Tomato and Other Plant Species

In this study, two methods were used to identify potential SOD genes in tomato. First, the whole tomato genome was downloaded from Sol Genomics Network (SGN1) and a local database was constructed using the software Bioedit 7.0 (Pan and Jiang, 2014). Four SOD amino acid sequences from Solanum lycopersicum (AF527880-CuSOD), S. tuberosum (EU545469-FeSOD), Arabidopsis thaliana (AAM62550.1-MnSOD) and Musa acuminata AAA Group (AEZ56248.2-FeSOD) were used as a query against the local tomato amino acid database. Second, Hidden Markov Model (HMM) profiles of Cu/ZnSOD (PF00080), Fe-MnSOD (PF00081, PF02777) were downloaded from Pfam2. A BlastP search was performed to retrieve candidate tomato SOD genes. For BlastP, e-value was set at 1e-5. All redundant putative SOD sequences were excluded. The remaining SOD sequences were examined for copper/zinc and iron/manganese SOD domains by the Pfam server2. Physicochemical characteristics of SOD amino acid sequences were predicted by the Protparam tool3, including molecular weight (MW), and theoretical isoelectric point (pI) (Gasteiger et al., 2005).

In addition, to reveal the evolutionary relationships between SOD genes in different plant species, potential SOD genes from eight plant species were selected for phylogenetic analysis. Among them, SOD genes from four plant species (Vitis vinifera, Solanum tuberosum, Zea mays, and Panicum miliaceum) were identified using the same method above. The SOD genes of the remaining plant species (Poplar, Arabidopsis thaliana, Oryza sativa, Sorghum bicolor) were derived from previously published studies (Kliebenstein and Last, 1998; Dehury et al., 2012; Molina-Rueda et al., 2013; Filiz and Tombuloğlu, 2014).

Subcellular Localization, Conserved Motifs, and Gene Structure Analysis of SlSOD Proteins

Subcellular localization of SOD proteins from different plant species was obtained from the ProtComp9.0 server4 (Feng et al., 2015). Conserved motif analysis of SlSOD genes was performed by the Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation (MEME Suite 4.11.1) server5 (Bailey et al., 2009). We used the method described by Feng et al. (2015), except that the number of motifs was set to 8. Intron/exon configurations of SlSOD genes were determined via the Gene Structure Display Server6, for both coding sequences and genomic sequences (Hu et al., 2015).

Chromosomal Location and Gene Duplication

Information about chromosomal location of SlSOD genes was obtained from the SGN database and gene duplications were identified by the Plant Genome Duplication Database (PGDD)7 (Singh and Jain, 2015). Tandemly duplicated SlSOD genes were identified according to methods reported by previous researchers (Yang and Tuskan, 2008; Tuskan et al., 2006). Chromosomal locations of the SlSOD genes were performed with the MapDraw V2.1 tool based on information from the SGN database (Huang et al., 2012). Sequence similarity of SODs was calculated using the program DNAMAN.

Phylogenetic Tree Construction of SODs

To investigate the phylogenetic relationships of SlSOD genes, a total of 108 SOD protein sequences were identified from nine plant species. Among them, 24 SOD protein sequences were excluded owing to the SOD domains being incomplete. Multiple sequence alignments of the remaining 84 SOD amino acid sequences were performed with ClustalW (Higgins et al., 1996) using default parameters. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the software MEGA5.04 via neighbor-joining method (Tamura et al., 2011). In the phylogenetic tree, the degree of support for a particular grouping pattern was evaluated using bootstrap (1000 replicates) value (Filiz et al., 2014). The tree was viewed with FigTree (v1.3.1).

Promoter Sequence Analysis

Regions 1,000 bp upstream from the start codons of each SlSOD gene were downloaded from SGN. Then, cis-elements in promoters of each SlSOD gene were predicted using the PlantCARE server (Postel et al., 2002).

Expression Patterns of SlSOD Genes Based on RNA-seq and Microarray Data

For RNA-seq analysis, transcription data of the genome-wide gene expression of the tomato cultivar Helnz were downloaded from the tomato functional genomics database (TFGD)8 (Fei et al., 2011). Ten different tissues were selected: root, leaf, bud, flower, 1-cm fruit, 2-cm fruit, 3-cm fruit, mature green fruit (MG), fruit at the fruit breaking stage (B), and fruit 10 days after the fruit breaking stage (B10). RPKM (Reads Per Kilo bases per Million mapped Reads) values of SlSOD genes were log2-transformed (Wei et al., 2012). Heat maps of SlSOD genes in different tissues were generated using MeV4.9 software (Singh and Jain, 2015).

In addition, microarray data for salt and drought stresses were downloaded from the TOM2 cDNA array and Affymetrix Tomato Genome Array platform from TFGD (Fei et al., 2011). Probe sets corresponding to SlSOD genes were identified using the Probe Match Tool in NetAffx Analysis Center9 (Altschul et al., 1997). A BlastN search was performed based on sequence alignment between probe sequences and SlSOD sequences. Expression patterns of SlSOD genes under salt and drought stresses were viewed using MeV4.9 software (Singh and Jain, 2015).

Plant Materials and Stress Treatment

Seeds of a tomato breeding strain, Zhe fen 202, were germinated on water-saturated filter paper. Before germinating, a 10% hypochlorous acid solution was used to sterilize seeds for 5 min. Then, seeds were washed three times with distilled water. Seedlings were grown on Hoagland nutrient solution, in a controlled chamber (25°C/20°C, day/night, 16 h/12 h light/dark cycle). Upon development of the fourth true leaf, seedlings were cultivated in Hoagland nutrient solution with 150 mM sodium chloride (NaCl) and 18% polyethylene glycol (PEG) for treatment (3 and 12 h), respectively. Leaves were collected and frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately and stored at -80°C. Three biological replications were carried out.

RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR Data Analysis

RNA extraction was performed using the RNAsimple Total RNA Kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China) according to manufacturer instructions. Before reverse transcription, the quality of RNA samples was checked by agarose gel electrophoresis. All RNAs were reverse transcribed into cDNA using the FastQuant RT Kit with gDNase (TIANGEN, Beijing, China) according to manufacturer instructions.

Specific primers for qRT-PCR analysis were designed using the GenScript server10 (Supplementary Table S1) and were synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai). The GAPDH gene was used as an internal control (Expósito-Rodríguez et al., 2008). An ABI StepOne real time fluorescence quantitative PCR instrument (Applied Biosystems, American) was used for qRT-PCR analysis. The quality and specificity of primers was determined by the melt curve (Feng et al., 2015). Three independent technical replicates were performed for each of the SlSOD genes. The PCR program consisted of an initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 55°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 30 s. The relative expression levels were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method, and were presented by histogram (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Results

Genome-Wide Identification of SOD Genes Family in Tomato

A total of nine SOD genes, classified into two major groups (Cu/ZnSODs and Fe-MnSODs), were identified in tomato. The former group included four members with a copper-zinc domain (SlSOD1, 2, 3, and 4); the latter was composed of five members with an iron/manganese SOD alpha-hairpin domain and an iron/manganese SOD, C-terminal domain (SlSOD5, 6, 7, 8 and 9) (Table 1). The physicochemical analysis showed that the length of amino acid sequences, MW, and pI values varied among these SlSOD proteins. The length ranged from 152 to 311AA, MW ranged from 15.3 to 34.6 kDa, and pI ranged from 5.38 to 7.13 (Table 1). No significant difference in the acid-base properties of SlSOD proteins was observed, except for SlSOD9, which was slightly basic. Using the ProtComp9.0 program, subcellular localizations of SlSOD proteins were determined. Among them, two Cu/ZnSODs (SlSOD1 and 2) and one Fe-MnSOD (SlSOD8) were predicted to localize in the cytoplasm. One Fe-MnSOD (SlSOD9) was localized in mitochondrion. The remaining members were localized in the chloroplast.

Table 1.

The characteristics of SOD genes from Solanum lycopersicum.

| Gene name | Sequence ID | Chromosome | ORF Length (bp) | Intron number | Length (aa) | MW (KDA) | pI | Predicted Pfam domain | Subcellular prediction by PC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SlSOD1 | Solyc01g067740.2 | 01 | 459 | 6 | 152 | 15.3 | 5.47 | CZ | Cytoplasm |

| SlSOD2 | Solyc03g062890.2 | 03 | 471 | 6 | 156 | 15.9 | 6.53 | CZ | Cytoplasm |

| SlSOD3 | Solyc11g066390.1 | 11 | 654 | 7 | 217 | 22.3 | 6.01 | CZ | Chloroplast |

| SlSOD4 | Solyc08g079830.2 | 08 | 936 | 5 | 311 | 32.9 | 6.45 | HMA,CZ | Chloroplast |

| SlSOD5 | Solyc06g048410.2 | 06 | 750 | 8 | 249 | 27.9 | 6.6 | IMA,IMC | Chloroplast |

| SlSOD6 | Solyc03g095180.2 | 03 | 912 | 8 | 303 | 34.6 | 5.38 | IMA,IMC | Chloroplast |

| SlSOD7 | Solyc02g021140.2 | 02 | 759 | 7 | 252 | 29.1 | 6.65 | IMA,IMC | Chloroplast |

| SlSOD8 | Solyc06g048420.1 | 06 | 483 | 4 | 160 | 17.9 | 6.41 | IMA,IMC | Cytoplasm |

| SlSOD9 | Solyc06g049080.2 | 06 | 687 | 5 | 228 | 25.3 | 7.13 | IMA,IMC | Mitochondrion |

MW, Molecular weight; pI, isoelectric points; CZ, copper/zinc superoxide dismutase (SODC); HMA, heavy-metal-associated domain; IMA, Iron/manganese superoxide dismutases alpha-hairpin domain; IMC, Iron/manganese superoxide dismutases, C-terminal domain; PC, ProtComp9.0 server.

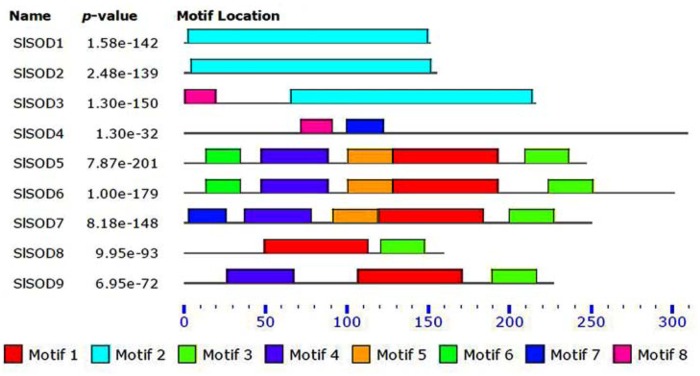

Conserved Motif Analysis of SlSOD Proteins

Four motifs in SlSOD proteins (motif 1 to motif 4) were identified by MEME. Among them, three motifs (motifs 1, 3, and 4) were related to iron/manganese SOD domains, while motif 2 was related to copper/zinc SOD domains (Table 2). As shown in Figure 1, motif 2 was located in Cu/ZnSODs (SlSOD1, 2 and 3), except SlSOD4; motif 1 and motif 3 were shared in Fe-MnSODs (SlSOD5, 6, 7, 8, and 9). Motif 4 was widely present in Fe-MnSODs, except for SlSOD8.

Table 2.

Eight different motifs commonly observed in tomato protein sequences by MEME server.

| Motif number | Width | Protein sequences | Pfam domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 65 | ESMKPGGGGEPSGELLQLINRDFGSYDTFVKEFKAAAATQFGSGWAWLAYKPEDKRLAIVKTPNA | IMC (shorten) |

| KAVAVLNGNDNVQGTIQFTQDDDGPTTVNGRITGLAPGLHGFHIHALGDTTNGCMSTGPH | CZ (SODC) | ||

| 2 | 149 | FNPNKKDHGAPMDEVRHAGDLGNIVAGPDGVAEITITDMQIPLTGPHSIIGRAVVVHADPDDLGKGGHE | |

| LSKTTGNAGGRIACGVIGLQ | |||

| 3 | 28 | WEHAYYLDFQNRRPDYISIFMEKLVSWE | IMC (shorten) |

| 4 | 42 | KFDLPPPPYPMDALEPHMSRRTFEFHWGKHHRAYVDNLNKQI | IMA (shorten) |

| 5 | 28 | IILVTYNNGNPLPPFNNAAQAWNHQFFW | |

| 6 | 22 | FLPPQGFNESCRSLQWRTQKKQ | |

| 7 | 23 | CCCQRCVSAVKSDLWRQFGIPNV | |

| 8 | 20 | METHSIFHQTSSDNGFVYPE |

Among them, Pfam domain of four mitifs (motif5, 6, 7 and 8) were not identify by Pfam server. CZ, copper/zinc superoxide dismutase (SODC); IMA, Iron/manganese superoxide dismutases alpha-hairpin domain; IMC, Iron/manganese superoxide dismutases, C-terminal domain.

FIGURE 1.

Conserved motif analysis of SlSOD proteins. Different color boxes represent different types of motifs.

Chromosomal Distribution and Intron/Exon Configurations of SlSOD Genes

The chromosomal distributions of nine SlSOD genes were determined. As shown in Figure 2, six out of the twelve chromosomes harbored SlSOD genes. Chromosome 6 and 3 possessed three and two SlSOD genes, respectively, while each of the remaining four chromosomes (chromosome 1, 2, 8, and 11) contained only one SlSOD gene. Notably, chromosome 6 had one gene cluster (SlSOD5 and 8), which was identified as tandem duplication event. Segmental duplication was identified between SlSOD5 (chromosome 6) and SlSOD6 (chromosome 3) by PGDD database. However, despite the sequence similarity between SlSOD5 and SlSOD6, no tandem-duplicated paralogous genes were found in the region surrounding SlSOD6.

FIGURE 2.

Chromosomal locations of 9 SlSOD genes on 12 chromosomes of tomato. Red lines represent the position of SlSOD genes on chromosomes. The chromosome numbers are indicated at the top of chromosomes. The segment duplication event occurred between SlSOD5 (chromosome 6) and SlSOD6 (chromosome 3) and one cluster including tandemly duplicated genes (SlSOD5 and SlSOD8) on chromosome 6.

Intron/exon configurations of SlSOD genes were constructed using the Gene Structure Display Server (GSDS 2.011) by aligning the cDNA sequences with the corresponding genomic DNA sequences (Figure 3). We found that intron numbers among these SlSOD genes ranged from 4 to 8. Two SlSOD genes (SlSOD5 and 6) exhibited the highest intron number (8), whereas SlSOD8 only had four introns (Table 1). In addition, two groups of SlSOD genes (SlSOD1 and 2, SlSOD5 and 6) exhibited similar intron/exon organization patterns, respectively. The rest of the SlSOD genes exhibited diverse intron/exon organization patterns.

FIGURE 3.

Intron/exon configurations of SlSOD genes. Exons and introns are shown as yellow boxes and thin lines, respectively. UTRs are shown with blue boxes. 0 = intron phase 0; 1 = intron phase 1; 2 = intron phase 2.

Phylogenetic Analysis of SOD Genes in Plants

To investigate the phylogenetic relationships of SOD proteins between tomato and other plant species, a total of 108 SOD proteins were identified from S. lycopersicum, Populus trichocarpa, Arabidopsis thaliana, Vitis vinifera, S. tuberosum, O. sativa, Zea mays, Sorghum bicolor, and Panicum miliaceum. Among them, 24 SOD proteins were excluded due to incomplete SOD domains. An unrooted phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the remaining 84 SOD proteins using the program MEGA5.04 (Tamura et al., 2011). As shown in Figure 4, the SOD proteins from different plant species were divided into two major groups, Cu/ZnSODs and Fe-MnSODs. The former group was subdivided into three subgroups (a, b, and c), and the latter was separated into two subgroups (d and e), which was strongly supported by high bootstrap values.

FIGURE 4.

Phylogenetic tree of 84 SOD proteins from tomato and other plants including Populus trichocarpa, Arabidopsis thaliana, Vitis vinifera, S. tuberosum, O. sativa, Zea mays, Sorghum bicolor, and Panicum miliaceum. Two groups (Cu/ZnSODs and Fe-MnSOD) were identified and the tree was divided into five groups (a, b, c, d and e) based on high bootstrap values. SlSOD proteins are marked in red. Three colors (coral, light blue and light green) represent the subcellular locations of SOD proteins: coral represents proteins localized in the cytoplasm, light blue represents proteins localized in chloroplasts, and light green represents proteins localized in mitochondria.

In our study, phylogenetic analysis showed that SlSOD1 grouped with OsSOD1 (Loc-Os03g22810), OsSOD2 (Loc-Os07g46990) and other plants’ cytosolic Cu/ZnSODs clustered in subgroup a. SlSOD4 grouped with OsSOD3 and other plants’ chloroplastic Cu/ZnSODs clustered in subgroup c, while two SlSOD genes (SlSOD2 and SlSOD3) were clustered with other plants’ cytosolic Cu/ZnSODs and chloroplastic Cu/ZnSODs in subgroup b, respectively. These results indicated that diversity in the Cu/ZnSODs gene family occurred before the splitting of mono- and dicot plants. Interestingly, Cu/ZnSODs genes in subgroup a were separated into mono- and dicot-specific branches, which suggested that they evolved independently after the splitting of mono- and dicot plants. In addition, FeSODs and MnSODs from different plant species were separated by a high bootstrap value (95%). Four genes (SlSOD5, 6, 7, and 8) were clustered with other plants’ chloroplastic FeSODs in subgroup d and SlSOD9 was clustered with other plants’ mitochondrial MnSODs in subgroup e.

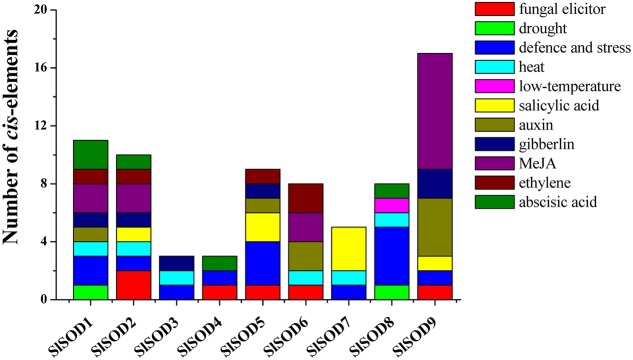

Analysis of Cis-Elements in Putative SlSOD Gene Promoters

To further understand gene function and regulation patterns, cis-elements in SlSOD gene promoter sequences were researched. Regions of 1,000 bp upstream from the start codons of each SlSOD gene were determined using PlantCARE. The results showed that the cis-elements could be divided into three major classes: stress-responsive, hormone-responsive, and light-responsive. Six stress-responsive cis-elements were identified, including HSE, MBS, LTR, TC-rich, ARE and Box-W1, which reflected plant responses to heat, drought, low-temperature, defense stresses, anaerobic induction and fungal elicitors, respectively. Ten kinds of hormone-responsive cis-elements were identified (e.g., salicylic acid-SA, methyl jasmonate-MeJA, gibberellins-GA, auxin-IAA, and ethylene) (Figure 5). A relatively large number of light-responsive cis-elements in SlSOD promoters was observed (Supplementary Table S2).

FIGURE 5.

Cis-elements in the promoters of putative SlSOD genes that are related to stress responses. Different cis-elements with the same or similar functions are present with the same color.

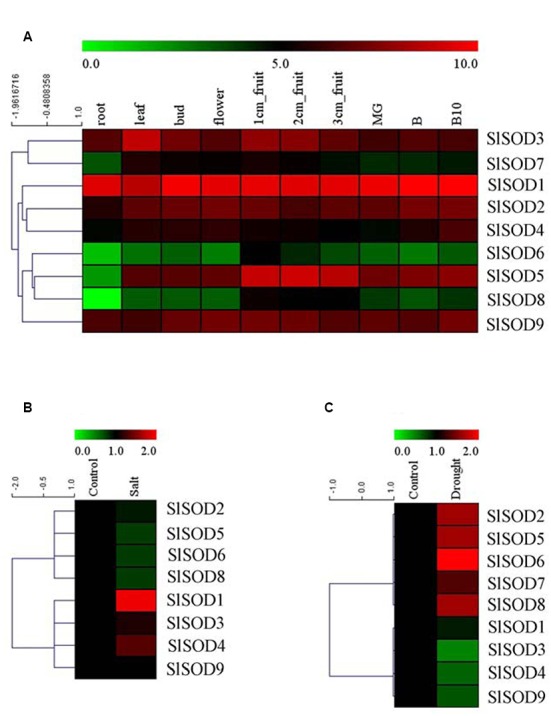

Expression Analysis of SlSOD Genes in Different Tissues

To explore the expression patterns of SOD genes during tomato growth and development, expression profiles were analyzed for 10 different tissues (root, leaf, bud, flower, 1-cm fruit, 2-cm fruit, 3-cm fruit, MG, B, and B10) of the tomato cultivar Helnz using the RNA-seq atlas. As shown in Figure 6A, five SlSOD genes (SlSOD1, 2, 3, 4 and 9) had similar expression patterns in all the tested tissues, while two genes (SlSOD6 and 8) displayed distinct tissue-specific expression patterns. Interestingly, SlSOD1 demonstrated a consistently high expression in all ten tissues, whereas SlSOD6 and 8 were mainly expressed in young fruit. In addition, SlSOD7 was expressed strongly in young fruit, weakly in root and moderately in the other tissues.

FIGURE 6.

Expression profiles of SlSOD genes in different tomato tissues and under various biotic and abiotic stresses. (A) The expression patterns of SlSOD genes in different tissues. The tested tissues are: root, leaf, bud, flower, 1 cm- fruit, 2 cm- fruit, 3 cm-fruit, mature green fruit (MG), fruit breaking (B), 10 days after fruit breaking (B10). (B) Expression profiles of SlSOD genes under salt stress. (C) Expression profiles of SlSOD genes under drought stress.

Expression Patterns of SlSOD Genes in Response to Abiotic Treatments

To gain further insight into the role of SlSOD genes under abiotic stress, we analyzed the expression profiles of SlSOD genes in response to salt and drought stresses using microarray data. A total of 17 independent tomato microarray probes were identified by means of a BlastN search. As shown in Figure 6B, expression of SlSOD genes was significantly altered under different abiotic stress treatments. For the salt treatment, eight probes corresponding to SlSOD genes were found, with the exception being SlSOD7. Expression of four SlSOD genes (SlSOD2, 5, 6, and 8) were down-regulated, and expression of three SlSOD genes (SlSOD3, 4, and 9) remained constant. Notably, SlSOD1 was significantly up-regulated. For the drought treatment, microarray probes for each SlSOD gene were identified. Four SlSOD genes (SlSOD2, 5, 6, and 8) were up-regulated and three (SlSOD3, 4, and 9) were down-regulated (Figure 6C). Notably, SlSOD6 expression increased twofold. SlSOD1 and SlSOD7 were unchanged. We found that the expression levels of most of the SlSOD genes changed significantly under salt and drought stresses.

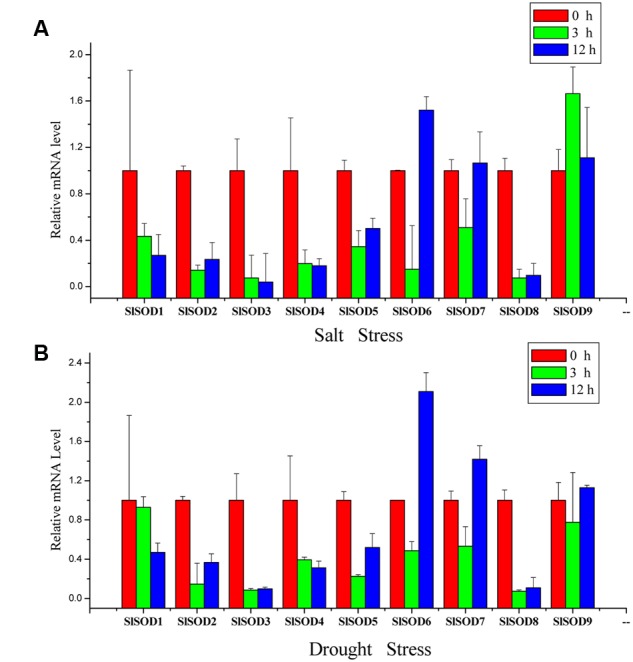

Verification of SlSOD Gene Expression Patterns with qRT-PCR

To further verify the expression profiles of SlSOD genes determined by microarray data analysis, qRT-PCR was used to analyze expression patterns of the nine SlSOD genes under salt and drought stresses. As shown in Figure 7, most of the SlSOD gene results were consistent with the microarray patterns. In response to salt treatment, expression levels of most SlSOD genes were down-regulated, in accordance with the microarray profiles. However, expression patterns of three SlSOD genes (SlSOD1, 6 and 9) determined by qRT-PCR analysis were different than those determined using the microarray profiles. We found that in response to salt treatment, there was enhanced expression of SlSOD6 and SlSOD9 and a decreased transcript level of SlSOD1. In response to drought treatment, expression levels of five SlSOD genes (SlSOD1, 3, 4, 6, and 7), were consistent with the microarray data. However, in contrast to our microarray results, qRT-PCR analysis showed down-regulation of three SlSOD genes (SlSOD2, 5, and 8) and up-regulation of SlSOD9.

FIGURE 7.

Gene expression profiles of SlSOD genes in response to salt and drought treatments using qRT-PCR. (A) Expression patterns of SlSOD genes under salt stress conditions. (B) Expression patterns of SlSOD genes under drought stress condition. Error bars represent standard deviations from three independent technical replicates.

Discussion

Environmental stresses pose considerable challenges for crop production. Gene expression and SOD enzyme activities are influenced by environmental stresses such as high salinity, drought and metal toxicity (Schützendübel and Polle, 2002; Atkinson et al., 2013). However, plants have evolved defense mechanisms to alleviate the damage caused by adverse environmental conditions. Tomato, an important staple and economic crop, is affected by various abiotic stresses (Mueller et al., 2005). SODs are key enzymes in many oxidation processes, and provide basic protection against ROS in plants (Alscher and Erturk, 2002). Therefore, a systematic analysis of the SlSOD gene family was performed and gene expression patterns were determined for plants under various abiotic stresses.

In this study, nine SlSOD genes (four Cu/ZnSODs, four FeSODs, and one MnSOD) were identified in the tomato genome, including all three major types of plant SOD genes. Chromosome location analysis revealed that SlSOD5 and SlSOD8 formed a gene cluster on chromosome 6 and identified as tandem duplicated event. Segmental duplication was identified between SlSOD5 (chromosome 6) and SlSOD6 (chromosome 3) by PGDD. Although SlSOD5 and SlSOD6 have similar sequence, no tandem duplicated events were occurred in the region surrounding SlSOD6. Considering the lower sequence similarity of SlSOD5 to SlSOD6 than that of SlSOD5 to SlSOD8, it appears that segmental duplication events predate the tandem duplication in the SlSOD5 and SlSOD8 gene cluster (Supplementary Table S3). Therefore, we concluded that segmental duplication and tandem duplication played key roles in the expansion of SOD genes in the tomato genome.

Gene structure analysis revealed that the intron number of SlSOD genes ranges from 4 to 8. Previous researchers reported that intron patterns of plant SOD genes were highly conserved, and that all cytosolic and chloroplastic SOD genes included seven introns except for one member (Fink and Scandalios, 2002; Filiz and Tombuloğlu, 2014). However, in this study, we observed that the intron numbers of six out of eight SlSOD genes (excepting SlSOD9) were varied, and only two SlSOD genes (SlSOD3, chloroplastic Cu/ZnSOD and SlSOD7, chloroplastic FeSOD) included seven introns. Thus, our data did not support the previous reports of plant SOD gene intron patterns. Variation in exon-intron structures was accomplished by three main mechanisms (exon/intron gain/loss, exonization/pseudoexonization and insertion/deletion), each of which contributed to structural divergence (Xu et al., 2012; Filiz and Tombuloğlu, 2014). Moreover, two groups of SlSOD genes (SlSOD1 and 2, SlSOD5 and 6) exhibited similar intron/exon organization patterns, respectively, which suggested high conservation in the evolutionary process.

Phylogenetic analysis showed that FeSODs and MnSOD from different plant species were separated by a high bootstrap value (95%). This result was in agreement with previous report (Fink and Scandalios, 2002). In plants, MnSODs had 70% homology but were different from FeSODs, which suggested that they originated from different ancestral genes (Miller, 2012). These data were well support our results that FeSODs and MnSOD of tomato were diverged with 95% bootstrap value.

To better understand the role of SlSOD genes under various environmental stresses, cis-elements in the promoter sequences were predicted by PlantCARE server. The results showed that three major classes of cis-elements were identified, including stress-responsive, hormone-responsive, and light-responsive. Many identified cis-elements in the promotes of SlSOD genes were related to heat, drought, low-temperature, defense stresses, anaerobic induction, fungal elicitors, SA, MeJA, GA, IAA and ethylene. As previously stated, cis-elements play an important role in plant stress responses; cis-elements such as ABRE, DRE, CRT, SARE and SURE respond to abscisic acid (ABA), dehydration, cold, SA, and sulfur, respectively (Sakuma et al., 2002; Maruyama-Nakashita et al., 2005; Shi et al., 2010; Osakabe et al., 2014). Thus, these results will contribute to further understand the various function role of SlSOD genes under complex abiotic stress conditions.

To further clarify the potential functions of SlSOD genes, expression profiles of all the SlSOD genes in different tissues were analyzed. Based on RNA-seq, nine SlSOD genes exhibited two disparate expression patterns: constitutive and tissue-specific expression patterns of SlSOD genes. During tomato growth and development, two genes (SlSOD1 and 9) sustained high expression in all the tested tissues. Two genes (SlSOD6 and 8) demonstrated a tissue-specific expression pattern, being mainly expressed in young fruits. SlSOD7 was expressed strongly in young fruit tissue, weakly in root tissue, and moderately in the rest of the tissues tested.

Under various natural conditions, plant growth and development are frequently affected by high salinity, drought, cold, bacteria, and insecticides (Xia et al., 2012). Previous researchers reported that three types of SODs (Cu/ZnSODs, FeSODs and MnSODs) have been exploited to eliminate ROS caused by abiotic stress (Kliebenstein and Last, 1998; Wu et al., 1999). To further clarify the putative roles of SOD genes in tomato response to abiotic stresses, we examined the expression patterns of nine SlSOD genes under salt and drought treatment conditions using microarray and qRT-PCR.

The results showed that the expression patterns of most SlSOD genes obtained by qRT-PCR were in conformity with those obtained from the microarray analysis. Expression analysis revealed that most SlSOD gene expression levels were changed in response to two abiotic stresses (salt and drought). For salt treatment, SlSOD1 was the only gene that showed significant up-regulation among the nine SlSOD genes, demonstrating that the function of SlSOD1 relates to salt stress. Compared to the other SlSOD genes, a greater variety and quantity of cis-elements were found in the promoter for SlSOD1, including two TC-rich motifs, an HSEs motif, and an MBS motif, which had been demonstrated to responsible for abiotic stress in banana (Feng et al., 2015). This could explain why SlSOD1 expression changed significantly under salt treatment. Moreover, although many cis-elements related to abiotic stresses were also found in the SlSOD8 promoter, SlSOD8 expression was significantly down-regulated under salt treatment. This suggested that some unidentified cis-element could play a vital role in regulating the expression of the SOD gene family in tomato under abiotic stress. Similar results have also been found in other plant species (Singh and Jain, 2015).

Additionally, we observed different expression patterns of SlSOD genes under salt and drought stress conditions (Figure 6). For example, the expression of four SlSOD genes (SlSOD2, 5, 6, and 8) decreased during the salt treatment, while increased expression levels were observed for these four genes in response to drought treatment. This suggested that different SOD genes in tomato could play different roles in eliminating ROS caused by different environment stresses.

Taken together, the data we obtained provides more information about the SOD gene family in tomato including sequence information, gene duplications, conserved motifs, gene structures, and phylogenetic relationships. Promoter analysis and complex regulation patterns of the SlSOD genes under abiotic stress contribute to our understanding of the expression patterns of SOD genes in plants and provide clues for further studies of the roles of SOD genes under different stress conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: HW, QZ, and KF. Performed the experiments: KF, JY, YC, MR, RW, QY, GZ, ZY, and YY. Analyzed the data: KF, JY, and ZL. Wrote the paper: KF and HW. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Research is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (31301774, 31272156, and 3150110311), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Q15C150010), and Young Talent Cultivation Project of Zhejiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences (2015R23R08E07, 2015R23R08E09), Public Agricultural Technology Research in Zhejiang (2016C32101, 2015C32049), and Technological System of Ordinary Vegetable Industry (CARS-25-G-16).

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2016.01279

References

- Alscher R. G., Erturk N. (2002). Role of superoxide dismutases (SODs) in controlling oxidative stress in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 53 1331–1341. 10.1093/jexbot/53.372.1331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F., Madden T. L., Schäffer A. A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., et al. (1997). Gapped blast and psi-blast: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25 3389–3402. 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asensio A. C., Gil-Monreal M., Pires L., Gogorcena Y., Aparicio-Tejo P. M., Moran J. F. (2012). Two Fe-superoxide dismutase families respond differently to stress and senescence in legumes. J. Plant Physiol. 169 1253–1260. 10.1016/j.jplph.2012.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson N. J., Lilley C. J., Urwin P. E. (2013). Identification of genes involved in the response of Arabidopsis to simultaneous biotic and abiotic stresses. Plant Physiol. 162 2028–2041. 10.1104/pp.113.222372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydin S., Büyük İ., Aras E. S. (2014). Expression of SOD gene and evaluating its role in stress tolerance in NaCl and PEG stressed Lycopersicum esculentum. Turk. J. Bot. 38 89–98. 10.3906/bot-1305-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baek K. H., Skinner D. Z. (2003). Alteration of antioxidant enzyme gene expression during cold acclimation of near-isogenic wheat lines. Plant Sci. 165 1221–1227. 10.1016/S0168-9452(03)00329-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey T. L., Boden M., Buske F. A., Frith M., Grant C. E., Clementi L., et al. (2009). MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 37 W202–W208. 10.1093/nar/gkp335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal A., Torres J., Reyes A., Rosado A. (2009). Exogenous auxin regulates H2O2 metabolism in roots of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum mill.) seedlings affecting the expression and activity of CuZn-superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxidase. Acta Physiol. Plant. 31 249–260. 10.1007/s11738-008-0225-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chahid K., Laglaoui A., Zantar S., Ennabili A. (2015). Antioxidant-enzyme reaction to the oxidative stress due to alpha-cypermethrin, chlorpyriphos, and pirimicarb in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum, Mill.). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 22 18115–18126. 10.1007/s11356-015-5024-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L. Y., Slot J. W., Geuze H. J., James D. C. (1988). Molecular immunocytochemistry of the CuZn superoxide dismutase in rat hepatocytes. J. Cell Biol. 107 2169–2179. 10.1083/jcb.107.6.2169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clair D. K. S., Oberley T. D., Muse K. E., Clair W. H. S. (1994). Expression of manganese superoxide dismutase promotes cellular differentiation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 16 275–282. 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90153-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crapo J. D., Oury T., Rabouille C., Slot J. W., Chang L. Y. (1992). Copper, zinc superoxide dismutase is primarily a cytosolic protein in human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89 10405–10409. 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehury B., Sarma K., Sarmah R., Sahu J., Sahoo S., Sahu M., et al. (2012). In silico analyses of superoxide dismutases (SODs) of rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 22 150–156. 10.1007/s13562-012-0121-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deshazer D., Barnnan J. D., Moran M. J., Friedman R. L. (1994). Characterization of the gene encoding superoxide dismutase of Bordetella pertussis and construction of a SOD-deficient mutant. Gene 142 85–89. 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90359-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Expósito-Rodríguez M., Borges A. A., Borges-Pérez A., Pérez J. A. (2008). Selection of internal control genes for quantitative real-time RT-PCR studies during tomato development process. BMC Plant Biol. 8:131 10.1186/1471-2229-8-131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei Z., Joung J. G., Tang X., Zheng Y., Huang M., Lee J. M., et al. (2011). Tomato functional genomics database: a comprehensive resource and analysis package for tomato functional genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 39 1156–1163. 10.1093/nar/gkq991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felisa W., Daniel G., Oscar S., Falkowski P. G. (2005). The role and evolution of superoxide dismutases in algae. J. Phycol. 41 453–465. 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00086.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X., Lai Z., Lin Y., Lai G., Lian C. (2015). Genome-wide identification and characterization of the superoxide dismutase gene family in Musa acuminata cv. Tianbaojiao (AAA group). BMC Genomics 16:823 10.1186/s12864-015-2046-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filiz E., Koç İ., Tombuloğlu H. (2014). Genome-wide identification and analysis of growth regulating factor genes in Brachypodium distachyon: in silico approaches. Turk. J. Biol. 38 296–306. 10.3906/biy-1308-57 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Filiz E., Tombuloğlu H. (2014). Genome-wide distribution of superoxide dismutase (SOD) gene families in Sorghum bicolor. Turk. J. Biol. 39 49–59. 10.3906/biy-1403-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fink R. C., Scandalios J. G. (2002). Molecular evolution and structure–function relationships of the superoxide dismutase gene families in angiosperms and their relationship to other eukaryotic and prokaryotic superoxide dismutases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 399 19–36. 10.1006/abbi.2001.2739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasteiger E., Hoogland C., Gattiker A., Duvaud S., Wilkins M. R., Appel R. D., et al. (2005). “Protein identification and analysis tools on the expasy server,” in Proteomics Protocols Handbook, ed. Walker J. M. (Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; ), 571–607. [Google Scholar]

- Giannopolitis C. N., Ries S. K. (1977). Superoxide dismutase: I. Occurrence in higher plants. Plant Physiol. 59 309–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez J. M., Hernández J. A., Jiménez A., del Río L. A., Sevilla F. (1999). Differential response of antioxidative enzymes of chloroplasts and mitochondria to long-term NaCl stress of pea plants. Free Radic. Res. 31(Suppl. 1), 11–18. 10.1080/10715769900301261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins D. G., Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J. (1996). Using CLUSTAL for multiple sequence alignments. Methods Enzymol. 266 383–402. 10.1016/S0076-6879(96)66024-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B., Jin J., Guo A. Y., Zhang H., Luo J., Gao G. (2015). GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics 31 1296–1297. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S., Gao Y., Liu J., Peng X., Niu X., Fei Z., et al. (2012). Genome-wide analysis of WRKY transcription factors in Solanum lycopersicum. Mol. Genet. Genomics 287 495–513. 10.1007/s00438-012-0696-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller G. A., Warner T. G., Steimer K. S., Hallewell R. A. (1991). Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase is a peroxisomal enzyme in human fibroblasts and hepatoma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88 7381–7385. 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E. J., Kim H. P., Hah Y. C., Roe J. H. (1996). Differential expression of superoxide dismutases containing Ni and Fe/Zn in Streptomyces coelicolor. Eur. J. Biochem. 241 178–185. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0178t.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliebenstein D. J., Last R. L. (1998). Superoxide dismutase in Arabidopsis: an eclectic enzyme family with disparate regulation and protein localization. Plant Physiol. 118 637–650. 10.1104/pp.118.2.637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. (2009). Physiological responses of tomato seedlings (lycopersicon esculentum) to salt stress. Mod. Appl. Sci. 3 171–176. 10.5539/mas.v3n3p171 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liou W., Chang L. Y., Geuze H. J., Strous G. J., Crapo J. D., Slot J. W. (1993). Distribution of CuZn superoxide dismutase in rat liver. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 14 201–207. 10.1016/0891-5849(93)90011-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 -ΔΔct method. Methods 25 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Feng Z., Bian L., Xie H., Liang J. (2011). miR398 regulation in rice of the responses to abiotic and biotic stresses depends on CSD1 and CSD2 expression. Funct. Plant Biol. 38 44–53. 10.1071/FP10178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M., Kuramitsu H. (2000). Expression and role of superoxide dismutases (SOD) in pathogenic bacteria 1. Microbes Infect. 2 1245–1255. 10.1016/S1286-4579(00)01278-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann T., Keilin D. (1938). Haemocuprein and hepatocuprein, copper-protein compounds of blood and liver in mammals. Proc. R. Soc. B 126 303–315. 10.1098/rspb.1938.0058 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama-Nakashita A., Nakamura Y., Watanabe-Takahashi A., Inoue E., Yamaya T., Takahashi H. (2005). Identification of a novel cis -acting element conferring sulfur deficiency response in Arabidopsis roots. Plant J. 42 305–314. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02363.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazorra L. M., Núñez M., Hechavarria M., Coll F., Sánchez-Blanco M. J. (2002). Influence of brassinosteroids on antioxidant enzymes activity in tomato under different temperatures. Biol. Plant 45 593–596. 10.1023/A:1022390917656 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCord J. M., Fridovich I. (1969). Superoxide dismutase. An enzymic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein). J. Biol. Chem. 244 6049–6055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. F. (2012). Superoxide dismutases: ancient enzymes and new insights. FEBS Lett. 586 585–595. 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.10.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R., Blumwald E. (2010). Genetic engineering for modern agriculture: challenges and perspectives. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 61 443–462. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R., Vanderauwera S., Gollery M., Breusegem F. V. (2004). Reactive oxygen gene network of plants. Trends Plant Sci. 9 490–498. 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Rueda J. J., Tsai C. J., Kirby E. G. (2013). The Populus superoxide dismutase gene family and its responses to drought stress in transgenic poplar overexpressing a pine cytosolic glutamine synthetase (GS1a). PLoS ONE 8:e56421 10.1371/journal.pone.0056421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller I. M. (2001). Plant mitochondria and oxidative stress: electron transport, NADPH turnover, and metabolism of reactive oxygen species. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Biol. 52 561–591. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.52.1.561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran J. F., James E. K., Rubio M. C., Sarath G., Klucas R. V., Becana M. (2003). Functional characterization and expression of a cytosolic iron-superoxide dismutase from cowpea root nodules. Plant Physiol. 133 773–782. 10.1104/pp.103.023010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller L. A., Solow T. H., Taylor N., Skwarecki B., Buels R., Binns J., et al. (2005). The SOL genomics network: a comparative resource for Solanaceae biology and beyond. Plant Physiol. 138 1310–1317. 10.1104/pp.105.060707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osakabe Y., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Shinozaki K., Tran L. S. P. (2014). ABA control of plant macroelement membrane transport systems in response to water deficit and high salinity. New Phytol. 202 35–49. 10.1111/nph.12613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan L. J., Jiang L. (2014). Identification and expression of the WRKY transcription factors of Carica papaya in response to abiotic and biotic stresses. Mol. Biol. Rep. 41 1215–1225. 10.1007/s11033-013-2966-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perl A., Perl-Treves R., Galili S., Aviv D., Shalgi E., Malkin S., et al. (1993). Enhanced oxidative-stress defense in transgenic potato expressing tomato Cu, Zn superoxide dismutases. Theor. Appl. Genet. 85 568–576. 10.1007/BF00220915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perl-Treves R., Abu-Abied M., Magal N., Galun E., Zamir D. (1990). Genetic mapping of tomato cDNA clones encoding the chloroplastic and the cytosolic isozymes of superoxide dismutase. Biochem. Genet. 28 543–552. 10.1007/BF00554381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perl-Treves R., Galun E. (1991). The tomato Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase genes are developmentally regulated and respond to light and stress. Plant Mol. Biol. 17 745–760. 10.1007/BF00037058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perl-Treves R., Nacmias B., Aviv D., Zeelon E. P., Galun E. (1988). Isolation of two cDNA clones from tomato containing two different superoxide dismutase sequences. Plant Mol. Biol. 11 609–623. 10.1007/BF00017461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilon M., Ravet K., Tapken W. (2011). The biogenesis and physiological function of chloroplast superoxide dismutases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1807 989–998. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postel D., Vanlemmens P., Gode P., Ronco G., Villa P. (2002). Plantcare, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 30 325–327. 10.1093/nar/30.1.325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puget K., Michelson A. M. (1974). Isolation of a new copper-containing superoxide dismutase bacteriocuprein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 58 830–838. 10.1016/S0006-291X(74)80492-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitch H. D., Sklan D. (1980). Superoxide dismutase: a possible protective agent against sunscald in tomatoes (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.). Planta 148 162–167. 10.1007/BF00386417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma Y., Qiang L., Dubouzet J. G., Abe H., Shinozaki K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. (2002). DNA-Binding specificity of the ERF/AP2 domain of Arabidopsis, DREBs, transcription factors involved in dehydration- and cold-inducible gene expression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 290 998–1009. 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasidharan S., Kulangara N. R., Sailas B. (2013). Biotic stress induced biochemical and isozyme variations in ginger and tomato by Ralstonia solanacearum. Am. J. Plant Sci. 4 1601–1610. 10.4236/ajps.2013.48194 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schützendübel A., Polle A. (2002). Plant responses to abiotic stresses: heavy metal-induced oxidative stress and protection by mycorrhization. J. Exp. Bot. 53 1351–1365. 10.1093/jexbot/53.372.1351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Z., Maximova S. N., Liu Y., Verica J., Guiltinan M. J. (2010). Functional analysis of the Theobroma cacao NPR1 gene in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 10:248 10.1186/1471-2229-10-248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh V. K., Jain M. (2015). Genome-wide survey and comprehensive expression profiling of Aux/IAA gene family in chickpea and soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 6:918 10.3389/fpls.2015.00918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soydam A. S., Büyük I., Aras S. (2013). Relationships among lipid peroxidation, SOD enzyme activity, and SOD gene expression profile in Lycopersicum esculentum L. exposed to cold stress. Genet. Mol. Res. 12 3220–3229. 10.4238/2013.August.29.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava V., Srivastava M. K., Chibani K., Nilsson R., Rouhier N., Melzer M., et al. (2009). Alternative splicing studies of the reactive oxygen species gene network in Populus reveal two isoforms of high-isoelectric-point superoxide dismutase. Plant Physiol. 149 1848–1859. 10.1104/pp.108.133371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L. H., Shen L. T., Ye S. (2007). Simultaneous overexpression of both Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase and ascorbate peroxidase in transgenic tall fescue plants confers increased tolerance to a wide range of abiotic stresses. J. Plant Physiol. 164 1626–1638. 10.1016/j.jplph.2007.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Peterson D., Peterson N., Stecher G., Nei M., Kumar S. (2011). MEGA5 : molecular, evolutionary, genetics, analysis, using maximum, likelihood, evolutionary, distance, and maximum, parsimony, methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28 2731–2739. 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepperman J. M., Dunsmuir P. (1990). Transformed plants with elevated levels of chloroplastic SOD are not more resistant to superoxide toxicity. Plant Mol. Biol. 14 501–511. 10.1007/BF00027496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuskan G. A., Difazio S., Jansson S., Bohlmann J., Grigoriev I., Hellsten U., et al. (2006). The genome of black cottonwood, populus trichocarpa (Torr.&Gray). Science 313 1596–1604. 10.1126/science.1128691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Lüttge U., Ratajczak R. (2004). Specific regulation of SOD isoforms by NaCl and osmotic stress in leaves of the C3, halophyte Suaeda salsa L. J. Plant Physiol. 161 285–293. 10.1078/0176-1617-01123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. W., Prabakaran N. (2011). 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid-induced leaf senescence in mung bean (Vigna radiata L. Wilczek) and senescence inhibition by co-treatment with silver nanoparticles. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 49 168–177. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei K. F., Chen J., Chen Y. F., Wu L. J., Xie D. X. (2012). Molecular phylogenetic and expression analysis of the complete WRKY transcription factor family in maize. DNA Res. 19 153–164. 10.1093/dnares/dsr048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wispé J. R., Warner B. B., Clark J. C., Dey C. R., Neuman J., Glasser S. W., et al. (1992). Human Mn-superoxide dismutase in pulmonary epithelial cells of transgenic mice confers protection from oxygen injury. J. Biol. Chem. 267 23937–23941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Wilen R. W., Robertson A. J., Gusta L. V. (1999). Isolation, chromosomal localization, and differential expression of mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase and chloroplastic copper/zinc superoxide dismutase genes in wheat. Plant Physiol. 120 513–520. 10.1104/pp.120.2.513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Z., Liu Q., Wu J., Ding J. (2012). ZmRFP1, the putative ortholog of SDIR1, encodes a RING-H2 E3 ubiquitin ligase and responds to drought stress in an ABA-dependent manner in maize. Gene 495 146–153. 10.1016/j.gene.2011.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G., Guo C., Shan H., Kong H. (2012). Divergence of duplicate genes in exon-intron structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 1187–1192. 10.1073/pnas.1109047109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Tuskan G. A. (2008). The F-box gene family is expanded in herbaceous annual plants relative to woody perennial plants. Plant Physiol. 148 1189–1200. 10.1104/pp.108.121921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youn H. D., Kim E. J., Roe J. H., Hah Y. C., Kang S. O. (1996). A novel nickel-containing superoxide dismutase from streptomyces spp. Biochem. J. 318 889–896. 10.1042/bj3180889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelko I. N., Mariani T. J., Folz R. J. (2002). Superoxide dismutase multigene family: a comparison of the CuZn-SOD (SOD1), Mn-SOD (SOD2), and EC-SOD (SOD3) gene structures, evolution, and expression. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 33 337–349. 10.1016/S0891-5849(02)00905-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.