Abstract

Circadian rhythm regulates multiple metabolic processes and in turn is readily entrained by feeding-fasting cycles. However, the molecular mechanisms by which the peripheral clock senses nutrition availability remain largely unknown. Bile acids are under circadian control and also increase postprandially, serving as regulators of the fed state in the liver. Here, we show that nuclear receptor Small Heterodimer Partner (SHP), a regulator of bile acid metabolism, impacts the endogenous peripheral clock by directly regulating Bmal1. Bmal1-dependent gene expression is altered in Shp knockout mice, and liver clock adaptation is delayed in Shp knockout mice upon restricted feeding. These results identify SHP as a potential mediator connecting nutrient signaling with the circadian clock.

Circadian clocks are autonomous internal daily timekeeping mechanisms that allow organisms to adapt to external daily environmental factors (1). The central pacemaker located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus synchronizes peripheral clocks present in many tissues, such as liver and pancreas, via direct and indirect signals (2). Light is the major cue for central clock. In contrast, the peripheral clocks can be reset by diverse cues in a suprachiasmatic nucleus-independent way (3), and fasting-feeding cycles are particularly potent Zeitgebers (4).

Increasing evidence indicates that metabolic pathways are both upstream modulators and downstream outputs of the circadian clock. Transcriptome and metabolome studies show that many metabolic enzyme genes and metabolites are under circadian control (5–10). Disruption of circadian rhythm leads to metabolic dysfunction. For example, ablation of Rev-erba in mice induces steatosis via derepression of lipogenic genes in the fasted state (11). In the opposite direction, it is well known that peripheral clocks can be rapidly entrained to altered cycles by changing nutrient availability, a process termed restricted feeding (RF) (12). Although many aspects of the impact of the circadian clock on liver metabolism have been elucidated, how nutrient availability entrains circadian clock in liver is largely unknown.

Bile acids are detergents and principal constituents of bile that promote absorption of lipid-soluble nutrients in the small intestine. They are actively reabsorbed in the terminal ileum and transported back to the liver via enterohepatic circulation through the portal vein (13). After a meal, elevated levels of bile acids activate hepatic Farnesoid X Receptor (FXR, NR1H4). A key transcriptional target of FXR is Small Heterodimer Partner (SHP, NR0B2), an unusual nuclear receptor that lacks a DNA-binding domain. In a well-known nuclear receptor cascade, activation of FXR induces SHP, which interacts directly with the nuclear receptor LRH-1 (NR5A2) to repress transcription of Cyp7a1 and Cyp8b1, which encode the 2 key enzymes for bile acid synthesis, leading to a decrease in the level of intrahepatic bile acids (7; see also reference 26 below). This autoregulatory feedback loop is a central mechanism that maintains bile acid homeostasis in the liver (14). In addition to controlling bile acid levels, modulation of SHP expression in response to nutrient related bile acid signals has multiple metabolic effects including lipid (15–17) and homocysteine (18) metabolism. SHP has also been identified as a direct target of CLOCK and as a mediator of multiple circadian metabolic effects (16, 17).

In addition to LRH-1, SHP has also been reported to interact with other nuclear receptors, including the clock component RAR-related Orphan Receptorγ (RORγ) (17). Thus, we hypothesized that SHP could provide a nutrient sensitive signal to the liver circadian clock that could contribute to food entrainment. Here, we show that liver SHP expression follows a circadian pattern and is altered upon inverted feeding. SHP directly represses expression of Bmal1 with complex outputs in the amplitudes and phases of oscillatory expression of clock genes both in mouse liver and mouse embryonic cells (mouse embryonic fibroblast [MEF]). The loss of SHP also delays adaptation to the inverted feeding entrainment of the liver clock. We conclude that SHP modulation of Bmal expression provides an input pathway for clock nutrient responsiveness.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Wild-type (WT) and Shp knockout (KO) mice (19) were maintained on a C57BL/6J background. Mice were housed with food and water available ad libitum unless otherwise indicated. Animals were maintained in Baylor College of Medicine's mouse facility with lights on at 7 am Zeitgeber Time 0 (ZT0). All experiments were done following approval of protocols by the animal care research committee of Baylor College of Medicine. The animals were maintained in a light-tight chamber at a constant temperature (23°C ± 1°C) and humidity (65% ± 10%). Livers were harvested at ZT12 (7 pm) in Figures 1, A–C, and 2A.

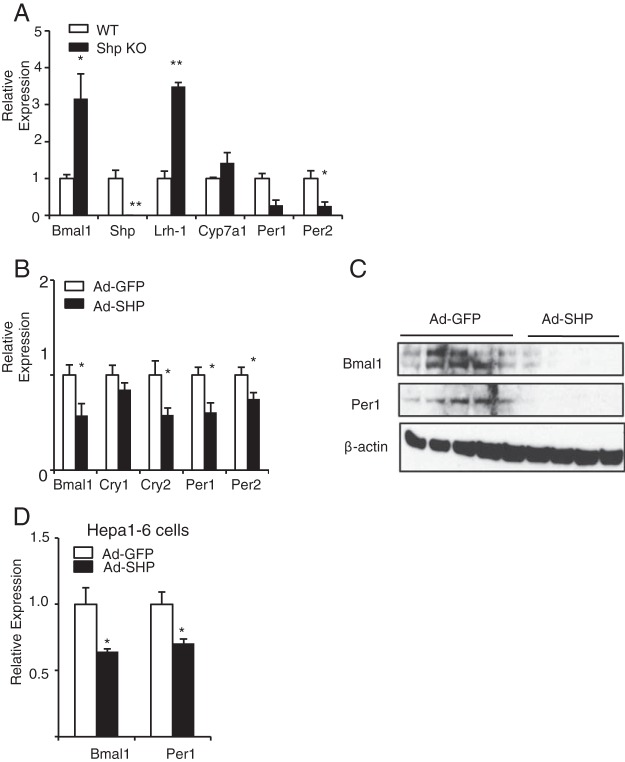

Figure 1.

SHP represses the expression of Bmal1 and other clock genes in mouse livers and Hepa1–6 cells. A, Bmal1 and clock gene expression in the livers of Shp KO mice. Mice were killed at ZT12 and livers were harvested for qPCR analysis. Mouse 36b4 was used as housekeeping gene (n = 4). B, Clock gene expression in mice injected with either Ad-SHP or Ad-GFP adenovirus via tail vein. Mice were killed at ZT12. Mouse 36b4 was used as housekeeping gene (n = 5). C, Protein levels of BMAL1, PER1, and β-Actin in mouse livers injected with Ad-GFP or Ad-SHP adenovirus via tail vein and killed at ZT12. D, Bmal1 and Per1 expression in Hepa1–6 cells infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-SHP adenovirus. Mouse 36b4 was used as housekeeping gene (n = 3). Data are presented as mean ± SEM; *, P < .05; **, P < .01.

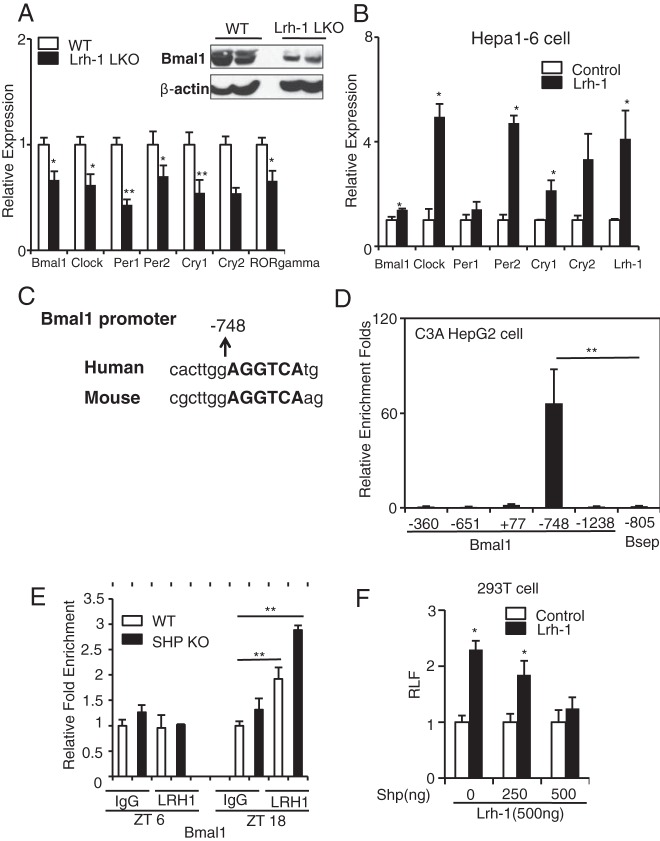

Figure 2.

LRH-1 directly activates Bmal1, while SHP represses, LRH-1 transactivation of the Bmal1 promoter. A, Circadian gene expression in the livers of WT and Lrh-1 liver-specific KO (Lrh-1 LKO) mice killed at ZT12, along with protein levels for BMAL1 and β-Actin. Mouse 36b4 was used as housekeeping gene (n = 3–4). B, Circadian gene expression in Hepa1–6 cells transfected with either a control vector or mLrh-1 expression vector by transient transfection (n = 3). C, Conservation of the putative LRH-1-responsive binding site in the Bmal1 promoter between mouse and human sequences. The binding site is 748 bp upstream from the transcriptional starting site. D, Endogenous LRH-1 enrichment at the putative LRH-1-binding site on the human Bmal1 promoter by ChIP in C3A HepG2 cells (n = 3). E, Endogenous LRH-1 enrichment at the putative LRH-1 binding site on the mouse Bmal1 promoter by ChIP assay in WT and SHP KO mouse livers at ZT6 and ZT18 (n = 3). F, 293T cells were transfected with either empty vector or Lrh-1, Shp, and Bmal1-luciferase. Luciferase activity was measured and fold activation or repression was calculated. Mean ± SEM of triplicate samples is shown; *, P < .05; **, P < .01, compared with empty vector by Student's t test.

Animals and administration of recombinant adenovirus

Eight to 10-week-old male C57BL/6 mice were given unrestricted access to water and maintained on a normal chow diet. Adenovirus particles were injected via tail vein at a dose of 3 × 10−9 plaque forming units per mouse. Mice were randomly divided into 2 groups and injected with adenoviruses expressing Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) or SHP (Ad-GFP, Ad-SHP). At time of necropsy, the livers were harvested for RNA analysis.

Mammalian cell culture and transfection

Mouse primary hepatocytes were prepared and maintained in William's E medium (Invitrogen), supplemented with 10-μg/mL insulin (Sigma-Aldrich). C3A HepG2, HEK-293T, and Hepa1–6 cells were maintained in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen). MEF cells were maintained in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells were grown at 37°C in 5% CO2. All transient transfection assays were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For luciferase assays, cells were grown in 12-well plates and transfected with 0.1 mg of Bmal1-luciferase reporter, 0.5 mg of mLrh-1 expression vector, 0–1.5 mg of Shp expression vector, and 0.1 mg of β-galactosidase expression vector. The total amount of expression plasmid transfected per well was kept constant by adding varying amounts of empty vector. At 48 hours after transfection, cells were lysed and their luciferase activity was assayed. Luciferase units were normalized to β-galactosidase expression. Fold repression was calculated as the activity of the same reporter in the presence of Shp or Lrh-1 expression vector, with the control group normalized to 1. Light units were normalized to the cotransfected β-galactosidase expression plasmid. Fold activation was calculated as the activity of a given reporter after transfection with control expression vector divided by the activity of the same reporter in the presence of Lrh-1 alone or both Lrh-1 and Shp expression vectors.

Plasmids and reagents

The Bmal1-luciferase reporter construct was a gift from Dr Yin Lei's lab, which includes 915 bp of the human Bmal1 promoter sequence. The expression vectors encoding human Shp and mouse Lrh-1 have been described previously (20).

Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in whole-cell lysis buffer (1× RadioImmunoPrecipitation Assay (RIPA) buffer; Thermo Scientific) with protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor. A total of 20–60 μg of lysates was separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Blots were probed with the following antibodies: anti-BMAL1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-PER1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-β-Actin (HorseRadish Peroxidase (HRP); Cell Signaling).

Mouse studies and measurement of hepatic cholesterol and triglycerides (TGs)

For circadian gene expression experiments, male C57BL/6 mice (8–10 wk of age) were maintained on a 12-hour light, 12-hour dark (L/D) cycle for at least 3 weeks. Mice (n = 3) were then killed at ZT2, ZT6, ZT10, ZT14, ZT18, and ZT22, and livers were harvested. Gene expression was determined by real-time qPCR. For the RF regimen, mice were placed in a normal L/D cycle with food taken out during lights out (ZT10–ZT2) and free access to food during lights on (ZT2–ZT10). Hepatic cholesterol and TGs were measured according to previous paper (21).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed by t test where appropriate. Statistical analysis was accepted as significant P < .05.

Results

SHP represses the expression of Bmal1 and other clock genes in mouse livers and Hepa1–6 cells

SHP controls bile acid homeostasis and energy balance in the liver (22–24). BMAL1 is essential for the regulation of mammalian clock genes and is the only gene whose deletion in mouse models results in arryhthmicity at both molecular and behavioral levels (25–27). A potential connection between these key regulatory nodes was suggested by the observation of increased Bmal mRNA expression in Shp KO livers (Figure 1A). This was associated with increased expression of the SHP regulatory target LRH-1, a modest increase in Cyp7a1, and also in decrease in Per2 expression. In the opposite direction, acute overexpression of Shp in mouse liver strongly decreased Bmal1 mRNA and particularly protein expression (Figure 1C and Supplemental Figure 1A). Acute SHP overexpression also decreased expression of additional circadian components (Figure 1, B and C), which is consistent with the loss of the positive impact of Bmal on their expression. The decreased expression of Per1/2 in the Shp KO liver is not expected in this context, but was not observed over a 24-hour cycle (see figure 4 below) and may be an adaptation to the long term absence of SHP. To test whether these effects are cell autonomous, we overexpressed Shp in Hepa1–6 cells and again observed diminished expression of Bmal1 and Per1 (Figure 1D and Supplemental Figure 1B).

SHP represses LRH-1 transactivation of the Bmal1 promoter

SHP is an unusual nuclear receptor that lacks a DNA-binding domain (28) but functionally interacts with LRH-1 to repress bile acid biosynthetic genes (20). This suggests that LRH-1 could also be the functional target for the effects of SHP on Bmal expression. Thus, we measured clock gene expression from livers of mice lacking hepatic Lrh-1 (Alb-Cre;Lrh-1fl/fl) and their control littermates (Lrh-1fl/fl). Bmal, Clock, Per1, Per2, Cry1, Cry2, and RORγ were all found to be decreased, with the BMAL1 decrease also observed at the protein level (Figure 2A). Overexpression of mouse Lrh-1 by transient transfection enhanced endogenous Bmal1, Clock, Per2, and Cry1 expression in Hepa1–6 cells, and also Bmal1 and Nr1d1 in NIH 3T3 cells (Figure 2B and Supplemental Figure 2). Together, these results suggest that LRH-1 regulates clock gene expression in a cell-autonomous manner and that loss of LRH-1 function disrupts the peripheral clock.

Because LRH-1-binding sites are predominantly located in proximal promoter regions, we screened the promoter sequence of human Bmal1 and identified several putative LRH-1-binding sites (29) at −360, −651, −748, and −1238 bp relative to the transcription start site and at +77 in exon 1. Among these, the LRH-1-binding site at −748 is conserved between human and mouse (Figure 2C). We then performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) using an anti-LRH-1 antibody in the more hepatocyte like C3A derivative of HepG2 cells (30). Primers flanking the putative LRH-1-binding sites at +77 (exon 1), −360, −651, −748, and −1238 bp in the human Bmal1 promoter were used, with primers for a nonbinding region of the human Bsep gene as a negative control (31). We observed that LRH-1 was highly enriched at the −748 position in the Bmal1 promoter (Figure 2D). In addition, we also performed LRH1 ChIP in mouse livers from WT and Shp KO mice at ZT6 and ZT18. The binding of LRH1 to the mouse Bmal1 promoter was time point-dependent. At ZT18, LRH-1 binding of LRH1 at the −748 site increased by 1.9-fold in WT mice and 2.9-fold in Shp KO mice relative to ZT6 (Figure 2E). The increased LRH-1 occupancy in the KO is likely to the loss of the corepressor SHP and stabilization by coactivators. The increased LRH binding to the Bmal1 promoter correlates with the peak of Bmal1 expression at ZT18. On the other hand, LRH1 binding to the Cyp7a1 promoter, which serves as a positive control for LRH1 ChIP assays (Supplemental Figure 3), is not time-point dependent.

To investigate whether SHP binds to the same region as LRH-1, we also performed ChIP using an anti-Flag antibody HepG2/C3A cells transduced with Flag-mSHP adenovirus. As expected, Flag-SHP was enriched at the −748 position in the Bmal1 promoter (Supplemental Figure 4). To test the functional consequence of LRH-1 binding to the Bmal1 promoter, we transfected 293T cells with a luciferase reporter driven by the human Bmal1 promoter, which contains the −748 LRH-1-binding site (gift from Dr Yin Lei), as well as mouse LRH-1 and mouse SHP expression vectors. LRH-1 cotransfection transactivated Bmal1-luciferase reporter activity by 2.3-fold. Increasing amounts of SHP cotransfected with LRH-1 suppressed reporter activity in a dose dependent manner (Figure 2F). Together, these results demonstrate that Bmal1 is a direct target of LRH-1 and that LRH-1 transactivation is subject to repression by SHP, as expected.

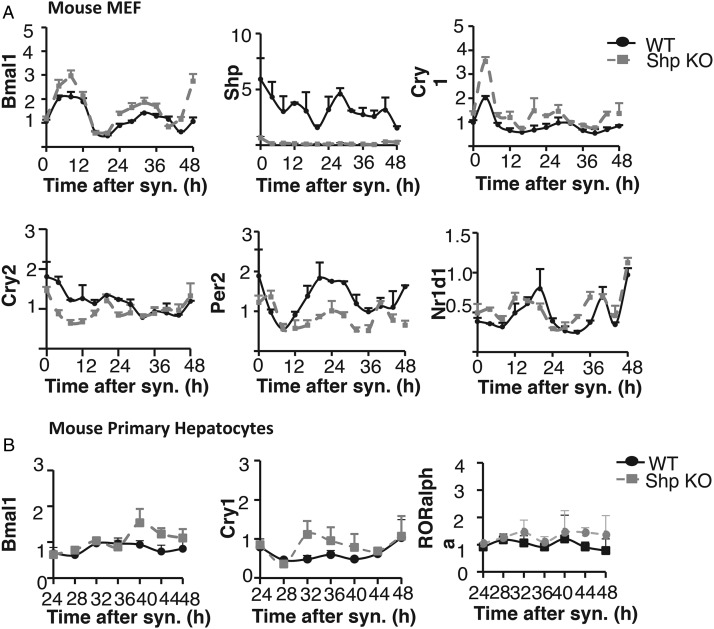

SHP regulates Bmal1 in a cell-autonomous manner in both MEF cells and mouse primary hepatocytes

Circadian regulation can be recapitulated in vitro using the well-established model of entrainment of MEFs using serum shock (5, 32, 33). To test whether the impact of SHP on Bmal1 is cell-autonomous and whether SHP contributes to circadian expression of Bmal1, we used immortalized MEFs derived from either WT or Shp KO mice (gift from Dr Wang Li). MEF cells were synchronized by serum-shock, then harvested every 4 hours during a 48-hour period. As expected, the expression of Bmal1 was enhanced at most time points studied in Shp KO MEFs compared with WT controls (Figure 3A). In addition, Shp expression fluctuates with a 24-hour cycle (Figure 4B) in WT MEF cells.

Figure 3.

SHP regulates Bmal1 in a cell-autonomous manner. A, Clock gene expression in MEFs derived from WT and Shp KO mice. Immortalized MEFs derived from Shp KO mice or their littermates were starved and then synchronized by serum shock for 2 hours. The cells were collected for gene expression analysis every 4 hours for a duration of 48 hours. Bmal1, Shp, Cry1, Cry2, Per2, and Nr1d1 gene expression was analyzed by qPCR. We used mouse 36b4 as housekeeping gene. Error bars represent ±range (n = 2). B, Bmal1, Cry1, and RORα gene expression in primary hepatocytes isolated from WT and Shp KO mice. Mouse primary hepatocytes were starved and then synchronized by serum shock for 2 hours. The cells were collected for gene expression analysis every 4 hours between ZT24 and ZT48. Error bars represent ±range (n = 2). We used mouse 36b4 as housekeeping gene.

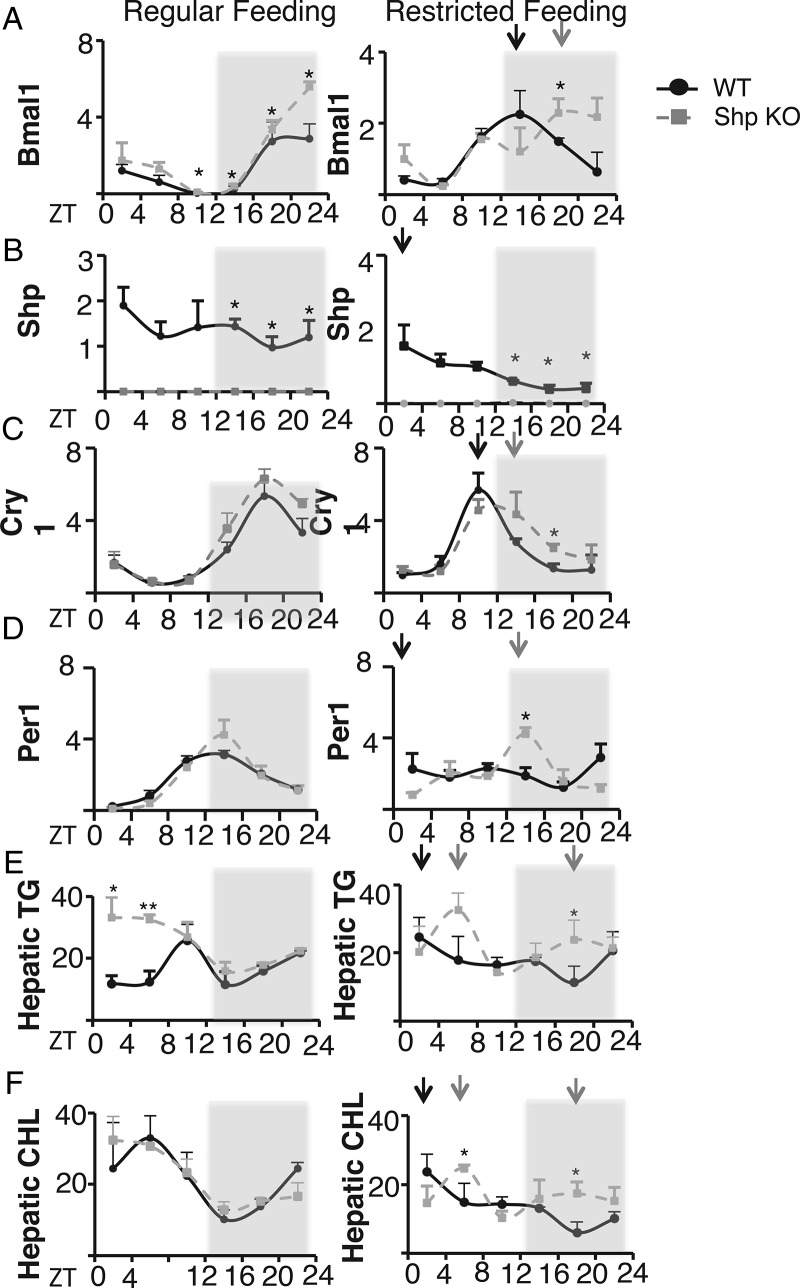

Figure 4.

SHP participates in the feeding entrainment of liver clocks. A–D, WT and Shp KO mice were first fed ad libitum. After 3 weeks, food was offered exclusively during the light phase (ZT12–ZT24). Starting 62 hours after changing the feeding regimen, animals were killed every 4 hours until 82 hours after changing the feeding time. Total RNA was prepared from liver and mRNA expression levels of Bmal1, Shp, Cry1, Nr1d1, and Per1 were determined by qPCR. E and F, Hepatic cholesterol and TGs were measured for WT and Shp KO mice under regular and RF regimens. Data points connected by a line represent the mean value obtained from 3 mice per time point. The average values are shown as black dots for WT mice and gray squares for Shp KO mice. Arrows indicate the time points of maximal expression of the respective genes in mice fed during inverted feeding. Time spans during which the lights were switched off are marked by gray shading (n = 3). Data are presented as mean ± SEM; *, P < .05; **, P < .01.

To determine whether the change in Bmal1 expression after Shp loss is sufficient to affect the circadian clock, we investigated the expression of Cry1, which is a direct target of the BMAL1-CLOCK complex. Indeed, the expression of Cry1 was generally increased in Shp KO MEFs. The amplitude of Cry1 expression was also elevated in Shp KO MEFs (Figure 3A), and other BMAL1-CLOCK complex targets exhibited altered expression. For example, Cry2 cycled with lower amplitude in Shp KO MEF (Figure 3A). Per2 expression exhibited higher amplitudes and a longer period, and Nr1d1 was phase advanced in Shp KO MEFs (Figure 3A).

We also investigated clock gene expression in mouse primary hepatocytes isolated from either WT or Shp KO mice and synchronized by serum shock. To avoid the variability of the circadian clock in the first 24 hours after synchronization, cells were harvested every 4 hours from 24 to 48 hours after synchronization. Although the amplitude of Bmal cycling was low by comparison with the MEFs, Bmal expression was enhanced at ZT40, ZT44, and ZT48 points in hepatocytes from Shp KO mice compared with WT controls (Figure 3B). Similarly, Cry1, a target gene of the BMAL1-CLOCK complex, is more highly expressed at ZT32, ZT36, and ZT40 (Figure 3B). In addition, another target gene, RORα, is more highly expressed from ZT28 to ZT48 (Figure 3B). Taken together, these results indicate that the transcriptional activity of the BMAL1-CLOCK complex is increased upon Shp loss.

SHP participates in the feeding-entrained liver clocks

We then investigated the effects of Shp ablation on circadian expression of Bmal1 and other targets in vivo. Total RNA was isolated from WT and Shp KO mice at ZT2, ZT6, ZT10, ZT14, ZT18, and ZT22. We observed that Bmal1 expression was significantly elevated in the liver of Shp KO mice at ZT10, ZT14, ZT18, and ZT22 (Figure 4A, left panel). Shp was expressed in a circadian pattern in WT mice, with expression lost in Shp KO mice as expected (Figure 4B). Previous reports suggest that Shp peaks at ZT8 in mouse liver, which is consistent with our finding (9).

The major circadian downstream transcriptional targets of Bmal1 expression and the BMAL1-CLOCK complex are Cry1 and Per1. Increased Bmal1 expression would be expected to increase such targets, and Cry1 and Per1 were both induced in Shp KO livers. More importantly, the amplitudes of Cry1, Per1, and Clock were also enhanced (Figure 4C and Supplemental Figure 5). Beyond the magnitude of gene expression, we also observed that loss of Shp altered the phase of several clock genes. For example, the phases of RORα and Nr1d1 expression were delayed in Shp KO livers compared with WT mice (Supplemental Figure 5, B and D). Thus, in addition to increasing Bmal1 expression, loss of Shp expression alters normal clock cycling at several levels.

Shp expression is tightly regulated by feeding-dependent changes in bile acids (34, 35). We therefore investigated whether SHP might participate in the food entrainment of the liver peripheral clock. To test the prediction that the kinetics of feeding-dependent circadian reentrainment would be altered in Shp KO mice, WT and Shp KO mice were maintained either fed ad libitum (during which mice eat mostly at night) and stably entrained in L/D cycles for 3 weeks, or else subjected to RF by allowing access to food only in the resting phase (light phase). Control untreated mice and mice treated with RF were then killed every 4 hours starting from ZT14 on the third RF day to ZT10 on the fourth RF day (Supplemental Figure 6) (36).

At this time point, it is expected that the new RF entrained cycling is at least partially established. Thus, the peak of Bmal1 and Cry1 expression in WT mice was shifted to approximately 8 hours earlier in the RF mice, with Per1 and the clock output gene Dbp showing a full 12-hour shift (Figure 4, A and C). In the normally fed Shp KOs, Bmal and was significantly higher, and Cry1 expression trended higher, as expected from the cell-based results. In the RF Shp KOs, the phase shift in the peak of both Bmal and Cry1 expression was delayed, with only an approximately 4-hour shift (Figure 4, A and C). The RF WT mice did not show a strong new peak of Per1 expression, indicating a lack of full entrainment, but the RF Shp KOs still appeared delayed, with no apparent shift in the peak relative to the normally fed Shp KOs (Figure 4D). For the clock output gene Dbp, RF induced a full 12-hour shift in the WT mice, but only an approximately 4-hour shift in the Shp KOs (Supplemental Figure 5A). There was also an approximately 4 hour delay in the peak expression of Nr1d1 the RF Shp KOs relative to the WT mice, but cycling of RORα and Clock was similar in the RF WT and Shp KO mice. The amplitude of Shp expression appeared to be increased and phase shifted after RF in the WT mice (Figure 4B), which is consistent with response of Shp expression to feeding signals. Overall, these results show a very clear pattern of delay in RF induced phase shift in the Shp KO livers. Thus, Shp is essential for normal adaptation of circadian gene expression to food entrainment.

In addition to affecting circadian gene rhythmicity, we wondered whether loss of Shp was physiologically deleterious upon the stimulation of RF. We therefore measured hepatic TGs and cholesterol levels in a 24-hour cycle under either ad libitum or RF conditions. TGs were increased over 2-fold in Shp KO mice in the ad libitum condition; in the RF condition, hepatic TG increased amplitude and no longer exhibited a clear circadian rhythm in Shp KO mice (Figure 4E). Although cholesterol levels in Shp KO livers were normal under ad libitum conditions, cholesterol circadian rhythmicity was also lost in Shp KO mice under RF (Figure 4F). This indicates that SHP not only participates in the feeding entrainment of liver clocks but also contributes to the normal control of lipid metabolism.

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate that, in addition to regulating bile acid metabolism, SHP and LRH-1 directly regulate Bmal1 gene expression and control its rhythmic expression in liver. In cell-based studies, we observed that overexpression of Shp can reduce Bmal1 expression by approximately 50%, whereas depletion of Shp can increase Bmal1 expression approximately 3-fold. As expected from these results, circadian Bmal1 expression significantly increased in Shp KO livers (Figure 4A). This direct regulation of the circadian clock is consistent with a recent report that SHP inhibits the Npas2 gene promoter by interaction with Rorγ to repress Rorγ transactivation, and by interacting with Rev-erbα to enhance transrepression (17).

The individual components of the clock have complex direct and indirect effects on the other components. Thus, it is not surprising that the direct effect of Shp on Bmal, Npas2, and potentially other primary targets is accompanied by indirect effects on other clock components. These are not evident in the normally entrained Shp KO livers, but are revealed when the clock is perturbed. Thus, Cry expression is higher, but Per1 expression is lower in the Shp KO MEFs, relative to the WT MEFs. These disparate responses, which seem inconsistent with the simplest expectations for the functions of the positive and negative arms of the clock machinery, are likely a reflection of the complex interregulatory circuits of the overall clock machinery. In the context of RF, the loss of Shp results in a very consistent delay in the reentrainment of the hepatic peripheral clock, with a 4 hour or greater delay in the phase shift of Bmal, Cry1, Per1, and the clock output gene Dbp (Figure 4 and Supplemental Figure 6). Thus, Shp is essential for normal reprogramming of the hepatic clock in response to the RF regimen.

Shp is well known as both a nutrient responsive regulatory target of bile acids returning to the liver via the enterohepatic circulation, and as an upstream regulator of metabolic processes including lipid metabolism. Thus, Shp is a key regulatory node in the daily fasting and feeding cycle. Both our current results and earlier studies establish Shp as a downstream target of the circadian cycle and a mediator of circadian metabolic effects (16, 17). The LRH-1-mediated effects of SHP on Bmal expression establish it as an upstream modulator of clock function. Thus, we conclude that Shp is a nutrient sensitive regulatory node acting both upstream and downstream of the circadian clock (Supplemental Figure 7).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Lei Yin (University of Michigan) for Bmal1-luciferase vector and Dr Li Wang (University of Connecticut) for immortalized MEF lines from WT and Shp KO mice.

This work was supported by the R. P. Doherty Jr.-Welch Chair in Science Grant Q-0022 (to D.D.M.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- FXR

- Farnesoid X Receptor

- KO

- knockout

- L/D

- 12-hour light, 12-hour dark

- LRH-1

- Liver Receptor Homolog-1

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast

- RF

- restricted feeding

- SHP

- Small Heterodimer Partner

- TG

- triglyceride

- WT

- wild type.

References

- 1. Foster RG, Roenneberg T. Human responses to the geophysical daily, annual and lunar cycles. Curr Biol. 2008;18:R784–R794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Albrecht U. Timing to perfection: the biology of central and peripheral circadian clocks. Neuron. 2012;74:246–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sabath E, Salgado-Delgado R, Guerrero-Vargas NN, et al. Food entrains clock genes but not metabolic genes in the liver of suprachiasmatic nucleus lesioned rats. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:3104–3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peek CB, Ramsey KM, Marcheva B, Bass J. Nutrient sensing and the circadian clock. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2012;23:312–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Alenghat T, Meyers K, Mullican SE, et al. Nuclear receptor corepressor and histone deacetylase 3 govern circadian metabolic physiology. Nature. 2008;456:997–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McCarthy JJ, Andrews JL, McDearmon EL, et al. Identification of the circadian transcriptome in adult mouse skeletal muscle. Physiol Genomics. 2007;31:86–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Panda S, Antoch MP, Miller BH, et al. Coordinated transcription of key pathways in the mouse by the circadian clock. Cell. 2002;109:307–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Okuda K, Nakanuma Y, Miyazaki M. Cholangiocarcinoma: recent progress. Part 1: epidemiology and etiology. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:1049–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yang X, Downes M, Yu RT, et al. Nuclear receptor expression links the circadian clock to metabolism. Cell. 2006;126:801–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eckel-Mahan KL, Patel VR, Mohney RP, Vignola KS, Baldi P, Sassone-Corsi P. Coordination of the transcriptome and metabolome by the circadian clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:5541–5546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Feng D, Liu T, Sun Z, et al. A circadian rhythm orchestrated by histone deacetylase 3 controls hepatic lipid metabolism. Science. 2011;331:1315–1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Damiola F, Le Minh N, Preitner N, Kornmann B, Fleury-Olela F, Schibler U. Restricted feeding uncouples circadian oscillators in peripheral tissues from the central pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2950–2961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Halilbasic E, Claudel T, Trauner M. Bile acid transporters and regulatory nuclear receptors in the liver and beyond. J Hepatol. 2013;58:155–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Davis RA, Miyake JH, Hui TY, Spann NJ. Regulation of cholesterol-7α-hydroxylase: BAREly missing a SHP. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:533–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huang J, Iqbal J, Saha PK, et al. Molecular characterization of the role of orphan receptor small heterodimer partner in development of fatty liver. Hepatology. 2007;46:147–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pan X, Zhang Y, Wang L, Hussain MM. Diurnal regulation of MTP and plasma triglyceride by CLOCK is mediated by SHP. Cell Metab. 2010;12:174–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee SM, Zhang Y, Tsuchiya H, Smalling R, Jetten AM, Wang L. Small heterodimer partner/neuronal PAS domain protein 2 axis regulates the oscillation of liver lipid metabolism. Hepatology. 2015;61:497–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tsuchiya H, da Costa KA, Lee S, et al. Interactions between nuclear receptor SHP and FOXA1 maintain oscillatory homocysteine homeostasis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1012–1023.e1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang L, Lee YK, Bundman D, et al. Redundant pathways for negative feedback regulation of bile acid production. Dev Cell. 2002;2:721–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee YK, Moore DD. Dual mechanisms for repression of the monomeric orphan receptor liver receptor homologous protein-1 by the orphan small heterodimer partner. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2463–2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee JM, Lee YK, Mamrosh JL, et al. A nuclear-receptor-dependent phosphatidylcholine pathway with antidiabetic effects. Nature. 2011;474:506–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chanda D, Li T, Song KH, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor family negatively regulates hepatic gluconeogenesis via induction of orphan nuclear receptor small heterodimer partner in primary hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:28510–28521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim YD, Li T, Ahn SW, et al. Orphan nuclear receptor small heterodimer partner negatively regulates growth hormone-mediated induction of hepatic gluconeogenesis through inhibition of signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5) transactivation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:37098–37108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Noh JR, Hwang JH, Kim YH, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor small heterodimer partner negatively regulates pancreatic β cell survival and hyperglycemia in multiple low-dose streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetic mice. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45:1538–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kume K, Zylka MJ, Sriram S, et al. mCRY1 and mCRY2 are essential components of the negative limb of the circadian clock feedback loop. Cell. 1999;98:193–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bunger MK, Wilsbacher LD, Moran SM, et al. Mop3 is an essential component of the master circadian pacemaker in mammals. Cell. 2000;103:1009–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Preitner N, Damiola F, Lopez-Molina L, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor REV-ERBα controls circadian transcription within the positive limb of the mammalian circadian oscillator. Cell. 2002;110:251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Seol W, Choi HS, Moore DD. An orphan nuclear hormone receptor that lacks a DNA binding domain and heterodimerizes with other receptors. Science. 1996;272:1336–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chong HK, Biesinger J, Seo YK, Xie X, Osborne TF. Genome-wide analysis of hepatic LRH-1 reveals a promoter binding preference and suggests a role in regulating genes of lipid metabolism in concert with FXR. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Aden DP, Fogel A, Plotkin S, Damjanov I, Knowles BB. Controlled synthesis of HBsAg in a differentiated human liver carcinoma-derived cell line. Nature. 1979;282:615–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Song X, Kaimal R, Yan B, Deng R. Liver receptor homolog 1 transcriptionally regulates human bile salt export pump expression. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:973–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Balsalobre A, Marcacci L, Schibler U. Multiple signaling pathways elicit circadian gene expression in cultured Rat-1 fibroblasts. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1291–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tamanini F. Manipulation of mammalian cell lines for circadian studies. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;362:443–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ellis E, Axelson M, Abrahamsson A, et al. Feedback regulation of bile acid synthesis in primary human hepatocytes: evidence that CDCA is the strongest inhibitor. Hepatology. 2003;38:930–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nishimaki-Mogami T, Une M, Fujino T, et al. Identification of intermediates in the bile acid synthetic pathway as ligands for the farnesoid X receptor. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:1538–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Asher G, Reinke H, Altmeyer M, Gutierrez-Arcelus M, Hottiger MO, Schibler U. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 participates in the phase entrainment of circadian clocks to feeding. Cell. 2010;142:943–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee JM, Wagner M, Xiao R, et al. Nutrient-sensing nuclear receptors coordinate autophagy. Nature. 2014;516:112–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]