Abstract

Rechargeable lithium ion batteries have ruled the consumer electronics market for the past 20 years and have great significance in the growing number of electric vehicles and stationary energy storage applications. However, in addition to concerns about electrochemical performance, the limited availability of lithium is gradually becoming an important issue for further continued use and development of lithium ion batteries. Therefore, a significant shift in attention has been taking place towards new types of rechargeable batteries such as sodium-based systems that have low cost. Another important aspect of sodium battery is its potential compatibility with the all-solid-state design where solid electrolyte is used to replace liquid one, leading to simple battery design, long life span, and excellent safety. The key to the success of all-solid-state battery design is the challenge of finding solid electrolytes possessing acceptable high ionic conductivities at room temperature. Herein, we report a novel sodium superionic conductor with NASICON structure, Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 that shows high room-temperature ionic conductivity of 3.5 × 10−3 S cm−1. We also report successful fabrication of a room-temperature solid-state Na-S cell using this conductor.

Since their introduction in 1991, rechargeable lithium-ion batteries have proliferated throughout consumer electronics. They continue doing so apace, alongside increasing use in stationary energy storage applications. In considering future rechargeable batteries, the increasing lithium consumption and the likely future costs must be taken into account. Sodium (Na) has redox potential of Eo = −2.71 V vs. standard hydrogen electrode, which is close to that of Li. Na-based batteries have recently began making a comeback as an alternative for large-scale energy storage1,2,3.

In the development of oxide-based batteries, a principal long-standing challenge is associated with the ionic conductivities of solid electrolytes, poor mixed ionic-electronic conductivities in the electrodes, and inferior interfacial contact between electrolytes and electrodes4. This explains the reason why, despite increasing interest in solid-state electrolytes, little progress in solid-state batteries has been reported, with only few publications on oxide-based solid-state sodium batteries5,6,7. In the present work, the fabrication of a room temperature solid-state Na-S battery using an oxide electrolyte is demonstrated that represents the first step towards the creation of a solid-state room-temperature Na-S battery.

The development of sodium batteries began with 1960s, when a sodium beta-Al2O3 (NaAl11O17) solid electrolyte was first reported8, which inspired intense interest in the solid-state electrochemistry of Na-conducting solid electrolytes. However, the high operation temperature (300 to 350 °C) required for this system has raised a series of concerns over battery design and manufacture, safety issues as well as maintenance costs. For example, the extremely corrosive polysulphide melts, and the degradation of sodium beta-Al2O3 at the high operation temperature, can potentially result in battery failure, leading to fire hazard, and in some cases causing explosion9,10. Decreasing the battery working temperature would enhance battery safety, improve durability, and reduce cost11. It is particularly desirable for a solid-state Na-based battery to operate at ambient temperature. Unfortunately, to date no superior solid-state electrolytes have been reported for room-temperature Na-based battery operation, in particular for the Na-S system. A promising sulphide glass-ceramic electrolyte with a conductivity of 10−4 S cm−1 at room temperature, has recently been reported by Tatsumisago’s group12. However, a practically useful value of 10−3 S cm−1 is required to enable realistic battery design13. Four decades ago, pioneering work by Hong and Goodenough on NASICON (sodium super ion conductor) structure, Na1+xZr2SixP3−xO12 (0 ≤ x ≤ 3), demonstrated that good room-temperature conductivities (~10−4 S cm−1) could be achieved, owing to the presence of a 3D cation transportation channel14,15. Surprisingly, this remarkable opening for further research in the field appears to have been ignored so far.

Previously, we studied Li-ion electrolytes with garnet structure16. The alkaline earth cations have long been viewed as confined to being located exclusively at the dodecahedral 8-coordination sites (La sites) in the garnet structure owing to their large ionic radii17,18. However, we found that alkaline earth metals can be made to occupy the octahedral 6-coordination sites (Zr sites) through a structural transformation by a facile mechanochemical method, leading to enhanced room-temperature conductivity19. We also note a report of conductivity enhancement in NASICON electrolytes to which metal oxides (for example, Y2O3, TiO2, SnO2, V2O5, Nb2O5, Ta2O5, MgO, ZnO) have been added, although the room-temperature conductivities were not studied in these systems20. Mindful of previous research reports, we describe here the development and characterization of NASICON electrolytes doped with alkaline earth ions at octahedral 6-coordination Zr sites through mechanochemical synthesis. Specifically, the prepared electrolyte with a composition of Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 presents a high room-temperature conductivity at the level of 10−3 S cm−1.

Results

Materials synthesis

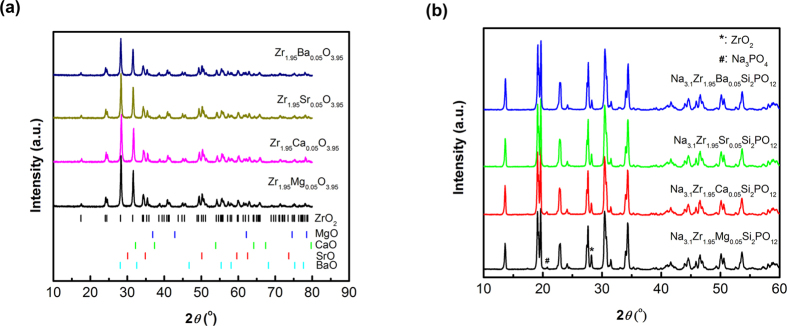

Na3.1Zr1.95M0.05Si2PO12 (M = Mg, Ca, Sr, Ba) were synthesized by doping with alkaline earth ions at octahedral 6-coordination Zr sites. The procedure employed in this work consists of two sequential steps. Firstly, solid solutions of alkaline earth metal oxides (MO) and ZrO2 were synthesized by high energy ball milling at 875 rpm for 2 h (SPEX SamplePrep 8000 M Mixer). Then NASICON Na3.1Zr1.95M0.05Si2PO12 structures were synthesized through solid-state reaction of Na2CO3, Zr1.95M0.05O3.95, SiO2, and NH4H2PO4 at 1260 °C. X-ray diffraction patterns (Fig. 1a) show that the matrix of Zr1.95M0.05O3.95 is ZrO2, rather than MO. This provides a clear piece of evidence that mechanochemical synthesis leads to the formation of a solid solution of MO in ZrO2. Sintered Na3.1Zr1.95M0.05Si2PO12 gives rise to XRD patterns (Fig. 1b) that exhibit monoclinic C2/c NASICON phase structure with very low impurity level of ZrO2, ~3–5wt.% from Rietveld refinement of powder XRD data (Tables S1–S4).

Figure 1.

XRD patterns of (a) solid solutions of ZrO2 and MO (M = Mg, Ca, Sr, Ba) after high energy ball milling for 2 h. (b) Na3.1Zr1.95M0.05Si2PO12 (M = Mg, Ca, Sr, Ba) sintered at 1260 °C for 16 h.

Materials characterization

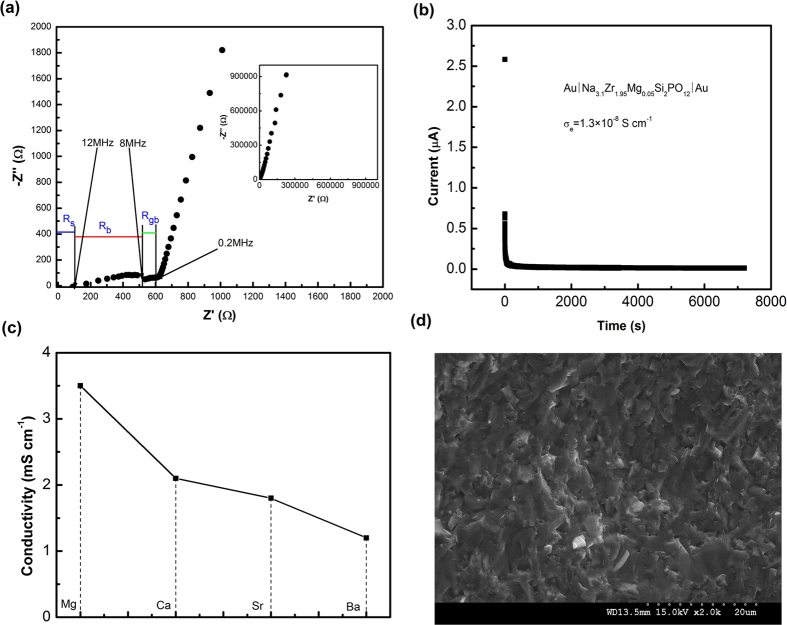

Conductivities of sintered pellets of Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 are evaluated by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). Typical EIS plots as shown in Fig. 2a obtained using ion-blocking Au electrodes exhibit two semicircles and one tail in the high- and low-frequency range, suggesting that the investigated material is inherently ionically conductive and is bulk-boundary resistance separated. The EIS results resolve well the grain and grain-boundary resistances at room temperature in the frequency range of 12 MHz and 0.2 MHz. In Fig. 2a, one depressed semicircle in the higher frequency range (12–8 MHz) represents the bulk contribution, Rb, which not start from “0” due to a contact resistance, Rs (~120 Ω), whereas, another semicircle in the lower frequency range (8–0.2 MHz) represents the grain-boundary contribution, Rgb21. The total conductivity of the Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 pellet (thickness of 2.7 mm and diameter of 4.5 mm) at room temperature is calculated to be ~3.5 × 10−3 S cm−1. An interesting observation is that the grain-boundary resistance is much lower than that of grain at room temperature. This demonstrates by far the best conductivity realized in a solid-state Na-ion electrolyte. Figure 2b shows the result of dc polarization measurement of sintered Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 pellet with Au as blocking electrodes. The electronic conductivity ~1.3 × 10−8 S cm−1 at room temperature is detected by dc polarization technique. The sodium-ion transference number is close to one (tNa+ = (σtotal − σe)/σtotal = 0.99999). The conductivities of Na3.1Zr1.95M0.05Si2PO12 (M = Ca, Sr, Ba) are lower than that of Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 (Fig. 2c). The Na+-ion mobility and conductivity depend mainly on the crystal structure. The addition of alkaline earth ions modifies the crystal structure of NASICON phase because of their large ionic radii. Besides, the addition of alkaline earth metals promotes sintering, and induces well-crystallized grains and dense microstructure (Fig. 2d) helpful for ion conduction.

Figure 2. Characterization of Na3.1Zr1.95M0.05Si2PO12 (M = Mg, Ca, Sr, Ba) electrolytes.

(a) Impedance plot of Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 measured in Ar at room temperature. The inset is described from 12 MHz to 1 Hz. (b) Time dependence of dc current for Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 pellet with applying a constant voltage of 1 V on the blocking electrodes. (c) Comparison of room-temperature conductivities of Na3.1Zr1.95M0.05Si2PO12. (d) SEM cross-section image of Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12.

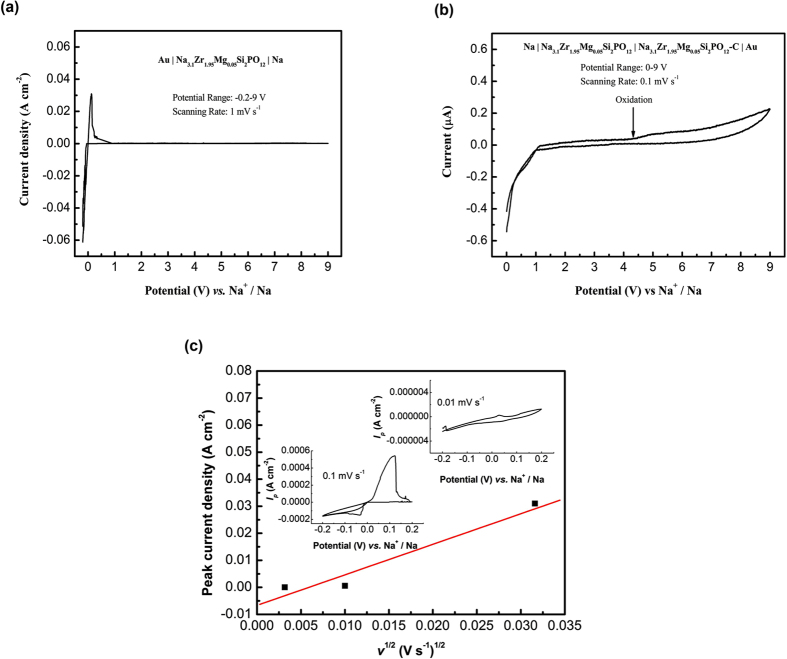

Besides the high ionic conductivity, an essential requirement for solid electrolytes is a large electrochemical stability window. The electrochemical stability of the present material against metallic sodium is examined by cyclic voltammetry using a Au/Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12/Na cell with a scan range of −0.2 to 9 V and a scan rate of 1 mV s−1 (Fig. 3a). It is noted that Han et al.22 indicated that the wide electrochemical stability of lithium solid electrolytes is overestimated by the large lithium deposition/dissolution peaks via conventional experimental method with Li/electrolyte/inert metal semi-blocking electrode, and new experimental method is developed to evaluate the electrochemical stability of lithium solid electrolytes which uses Li/electrolyte/electrolyte-carbon/inert metal cell. In the present work, therefore Na/Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12/Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12-carbon/Au cell is also assembled to further evaluate the electrochemical stability window of Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12, with a scan range of 0 to 9 V (to avoid Na deposition/dissolution peaks) and a scan rate of 0.1 mV s−1. As shown in Fig. 3b, the oxidation of Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 starts at about 4.5 V, but the current is very low with the maximum current of about 0.2 μA at scan voltage of 9 V, indicating that only a little bit of Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 is oxidized. Therefore, the Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 electrolyte possesses a practically useful electrochemical window of 0–4.5 V vs Na/Na+, which is sufficient to most of sodium cathodes.

Figure 3.

Cyclic voltammetry of Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12: (a) cyclic voltammetry of Au/Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 pellet/Na cell from −0.2 to 9 V at scan rate of 1 mV s−1, (b) cyclic voltammetry of Au/Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 pellet/Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12-carbon/Na cell from 0 to 9 V at scan rate of 0.1 mV s−1, and (c) Plot of peak current density vs. scan rate from the cyclic voltammetry. The inset is cyclic voltammetry curves at scan rate of 0.01 mV s−1 and 0.1 mV s−1.

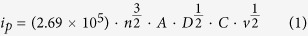

The diffusion coefficient at room temperature can be calculated by Eq. 1 using the relation between the scan rate and peak current obtained from the slop of ip/A vs. v1/2 plot23,24.

|

where D is the cation diffusion coefficient in cm2 s−1, ip represents peak current in Amperes, C corresponds to the initial Na concentration in mol cm−3, n is the number of electrons per reaction species, A represents the electrode area in cm2, v represents the sweep rate in V s−1. Figure 3c shows the ip/A vs. v1/2 plot and it gives rise to the value of diffusion coefficient D of 5.24 × 10−8 cm2 s−1.

The ionic conductivity is calculated via the Stokes-Einstein relationship25,

|

where C, q, R, and T are the Na concentration (0.019 mol cm−3), carrier charge, gas constant, and absolute temperature, respectively. The ionic conductivity is calculated to be 3.7 × 10−3 S cm−1, which is consistent with the conductivity value obtained from ac impedance method (3.5 × 10−3 S cm−1).

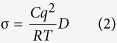

The Na/Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12/Na symmetric cells are galvanostatically cycled (Fig. 4). A minimal and stable polarization potential of 2.7 mV is obtained with current density of 44 μA cm−2. The direct-current conductivity of the present material is found to be 3.3 × 10−3 S cm−1 that is approximately consistent with the ac conductivity of 3.5 × 10−3 S cm−1 found by EIS, and the conductivity of 3.7 × 10−3 S cm−1 determined by cyclic voltammetry. Good agreement between different conductivity measurement methods (EIS, cyclic voltammetry, galvanostatic cycling), confirms the conclusion that the present material indeed possesses extremely high ionic conductivity in excess of 10−3 S cm−1 at room temperature.

Figure 4. Galvanostatic cycling of symmetrical cells with sodium electrodes and Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 electrolyte at the current density of 44 μA cm−2.

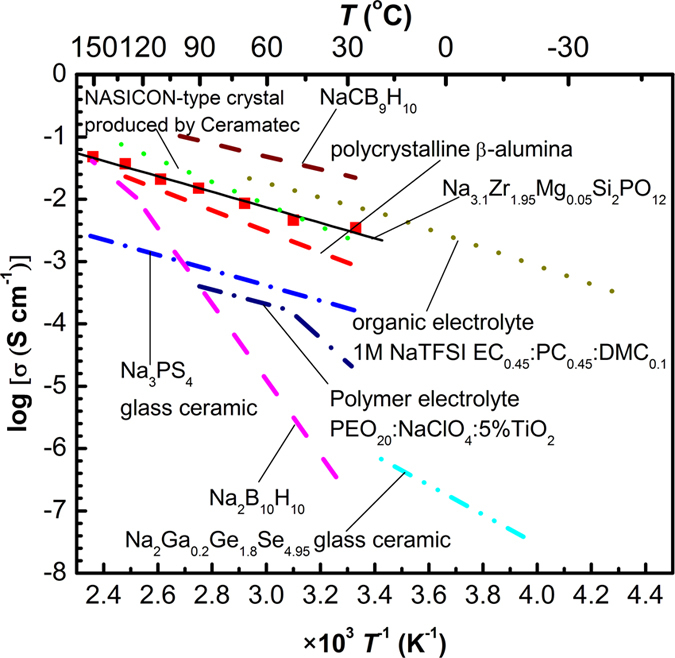

Figure 5 shows the temperature-dependent total ionic conductivity of Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 electrolyte together with those of other promising Na-ion electrolytes. The Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 electrolyte is characterized by the conductivity of ~3.5 × 10−3 S cm−1 at room temperature and activation energy of ~0.25 eV. For example, the organic liquid electrolyte propylene carbonate–ethylene carbonate-dimethyl carbonate (45:45:10 wt.%) containing 1M NaTFSI (ref. 26) has conductivity around 10−2 S cm−1. Polymer electrolyte, such as PEO-NaClO4-TiO2 (ether-oxygen-to-sodium ratio was 20:1, addition of 5% TiO2) (ref. 27) has room-temperature conductivity of 10−5 S cm−1. Doped sodium hydride electrolyte, such as Na2B10H10 has conductivity of 10−2 S cm−1 only above 110 °C, whilst its conductivity drops to only ~5 × 10−7 S cm−1 at room temperature28. Exceptionally, NaCB9H10 is reported to have the highest conductivity of ~0.03 S/cm at room temperature29. The chalcogenide glass-ceramic electrolyte, such as Na2Ga0.2Ge1.8Se4.95 has conductivity barely exceeding 10−5 S cm−1 at room temperature30. The crystalline Na3PS4 glass ceramic has conductivity of 2.62 × 10−4 S cm−1 at room temperature12, which is the best reported for a sodium sulphide conductor. The classical β-alumina electrolyte and NASICON-type crystal produced by Ceramatec possesses room-temperature conductivity of ~10−3 S cm−1, but extremely high sintering temperatures of 1800 °C are needed for fabrication31,32. The present Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 is characterized by practically useful conductivity of above 10−3 S cm−1.

Figure 5. Temperature-dependent ionic conductivity of Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 compared with other reported Na-ion conductors.

■: Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 values. The solid line represents linearly fitted data.

Application to all-solid-state sodium-sulphur batteries

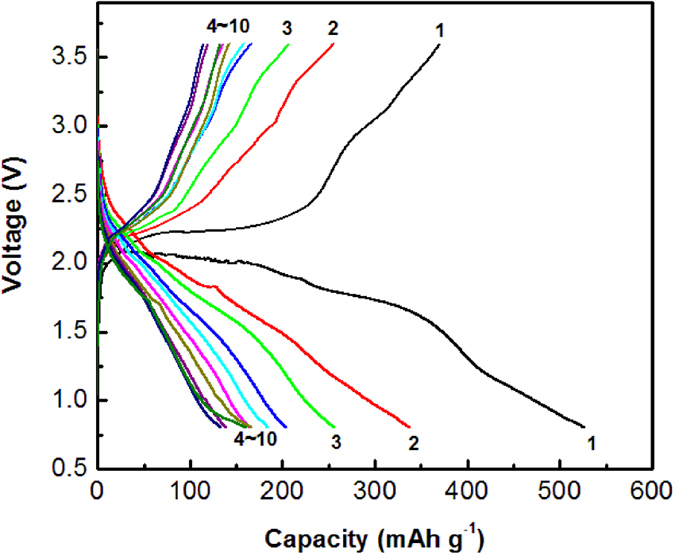

Discovery of the new solid electrolyte with high conductivity helps to overcome the poor mixed ionic and electronic conductivities. To reduce interfacial impedance and segregation of Na+ ions along the interface, inorganic-organic hybrid cathode can be considered. To achieve this, the immobilized ionic liquid-based Na-ion polymer electrolyte is firstly synthesized by a mechanochemical reaction. Then, the sulphur-carbon composite is synthesized through mechanochemical milling sulphur and carbon at the weight ratio of 1:1. The sulphur-carbon composite is mechanochemically milled with polymer electrolyte at the weight ratio of 1:1. Solid-state sodium batteries are assembled in a coin cell consisting of a sulphur-carbon-polymer hybrid cathode, a Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 electrolyte and a sodium anode. Figure 6 shows galvanostatic testing results of the Na-S battery (Na/Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12/S) operated with a cut-off voltage range of 0.8–3.6 V at the current of 8.92 μA (i.e., ~0.01C rate) at ambient temperature. The initial discharge capacity is about 527 mAh g−1. This capacity is higher than those of high-temperature Na-S cells using beta-alumina as electrolyte and ambient-temperature Na-S cells with traditional sulphur-carbon composite using organic liquid electrolyte9,11,33,34. The present cell experiences a sharp decrease in capacity during the initial 10 galvanostatic cycles, with the discharge capacity fading from 527 to 160 mAh g−1 during ten cycles. Severe capacity decrease is likely to be associated with the generation of reversible sodium polysulphides that resist oxidation during subsequent charging. This phenomenon is known to be a general problem in other sulphur-based batteries (i.e., high-temperature Na-S batteries and Li-S batteries)2. Specific directed effort is required to address this fading mechanism and to enhance the cell performance.

Figure 6. Charge-discharge profiles of a solid-state sodium battery (Na/Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12/S) at ambient temperature.

The batteries were examined at a constant current of 8.92 μA (i.e., ~0.01C rate) with a cut-off voltage of 0.8–3.6 V.

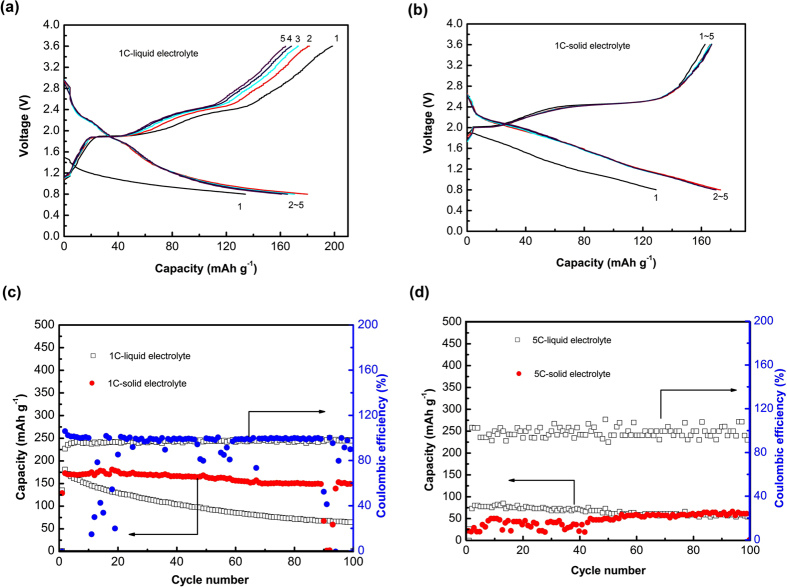

To evaluate the advantage of solid-state configuration to the liquid one, one cell is assembled with metallic sodium as anode, S-C composite as cathode, 1 M NaClO4/EC+PC (1:1 in weight) as liquid electrolyte, and glass microfiber as separator, whereas another cell using the present Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 pellet (~1.0 mm) as electrolyte and separator is assembled. Figure 7 shows the electrochemical performance of the two types of Na-S batteries with a cut-off voltage range of 0.8–3.6 V at 1C and 5C rate. As shown in Fig. 7a,b, for the cells using liquid electrolyte and solid electrolyte respectively at 1C rate, there are no obvious discharge plateaus, but two charge plateaus at about 2.0 V and 2.4 V, which indicates a stepped oxidation reaction during charging process. The voltage profiles of solid-state cell coincide from 2nd to 5th cycle, indicating stable electrochemistry. Figure 7c reveals the highest initial capacity is ~180 mAh g−1, and the discharge capacity decays to ~64 mAh g−1 at 1C rate after 100 cycles with a capacity retention of only 36% of the cell using liquid electrolyte. For the solid-state one, the highest initial capacity is slight lower than that of liquid one, ~170 mAh g−1, but it delivers capacity of 150 mAh g−1 over 100 cycling with a capacity retention of 88%, indicating better cycling stability compared with the conventional Na-S batteries using liquid electrolyte. The Coulombic efficiency is maintained at ~100% except the first cycle for both cells. As shown in Fig. 7d, at 5C rate, the cell using liquid electrolyte delivers better initial capacity of ~84 mAh g−1, and fades mildly to ~54 mAh g−1 after 100 cycles. For the solid-state cell, the initial capacity is ~21 mAh g−1, and increase mildly to ~56 mAh g−1 after 60 cycles and ~60 mAh g−1 after 100 cycles, that is similar with the liquid one. Therefore, it is demonstrated that the Na-S cells using solid-state electrolyte can achieve better cycling stability than the liquid counterpart, because the solid-state electrolyte can efficiently depress the dissolution and shuttle of sodium polysufides in electrolyte.

Figure 7.

Electrochemical performance of two types of Na-S batteries using liquid electrolyte and solid-state electrolyte: (a) voltage profiles of cells using liquid electrolyte at 1C rate, (b) voltage profiles of cells using solid electrolyte at 1C rate, and (c) cycling performance of the two types of cells at (c) 1C rate and (d) 5C rate.

Discussion

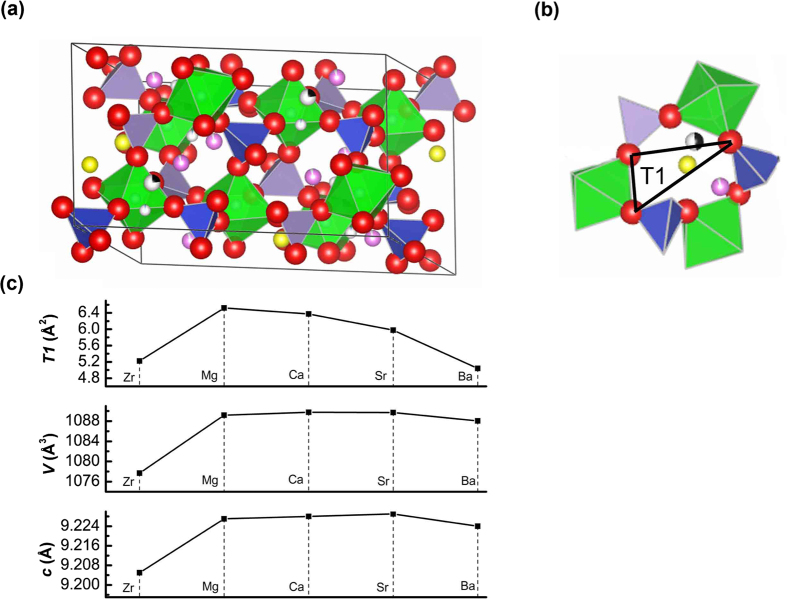

Structural features play a key role in delivering fast ionic conduction. The crystal structure of the present material is examined via Rietveld refinement of powder XRD data (Fig. S1 and Tables S1–S4). The structure includes ZrO6 octahedra corner-sharing with P/SiO4 tetrahedra, with the alkaline earth ions located at Zr sites. One ZrO6 octahedron is combined with six P/SiO4 tetrahedra, forming a monoclinic framework with a three-dimensional Na+ ions channels (Fig. 8a). The Na+ ions occupy three types of sites, which are coordinated by O2− ions as 6-fold Na(1) site, 8-fold Na(2) site and 5-fold Na(3) site, respectively35. Each Na(2) site connects two Na(1) sites, while each Na(1) site connects two Na(3) sites. There are no pathways among Na(2), Na(3) or Na(2) and Na(3) sites, owing to the long distances and/or polyhedra obstacles. We consider the possible efficient conduction pathway along the three-dimensional channels by selecting the shortest Na-Na hopping distances, that correspond to the lowest transport barrier36. For the Mg-doped system, the closest Na(1)-Na(2), Na(1)-Na(3), and Na(2)-Na(3) distances are 3.487 Å, 2.305 Å and 3.915 Å, respectively, which are more than twice the Na+ ionic radius (~1.02 Å). The Na(1)-Na(3) distance is the even shorter ~2.08 Å for Ca/Sr/Ba-doped systems, corresponding to approximately twice the Na+ ionic radius. This approch implies that the adjacent Na(1) and Na(3) sites may not be occupied simultaneously. The Na+ ions move toward the Na(1) vacancy, whilst, simultaneously the Na+ ions at the Na(3) sites migrate away, and vice versa. This suggests that the possible conduction pathway in monoclinic framework is the Na(2)-Na(1)-Na(3) pathway.

Figure 8. Refined crystal structure of Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12.

(a) Polyhedral drawing of the unit cell of Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12. Na(1) ions: black spheres, Na(2) ions: yellow spheres, Na(3) ions: purple spheres. (b) A bottleneck of Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 consisting of alternating three ZrO6 octahedra and three P/SiO4 tetrahedra. The triangle T1 is outlined. The Na(1), Na(2) and Na(3) ions are located below and above the bottleneck. (c) Lattice parameter, volume of unit cell and area of T1 of the Na3Zr2Si2PO1214,36 and Na3.1Zr1.95M0.05Si2PO12 (M = Mg, Ca, Sr, Ba).

It can be surmised that the observed increase in the ionic conductivity associated with the ionic radii of octahedrally coordinated cations, the large ionic radii increase the lattice parameters and cell volume, thus facilitating the Na+ ion mobility37. In the present materials, the unit cell parameters and cell volume increase with the substitution of alkaline earth ions for Zr, but little variation is observed for different alkaline earth ions (Fig. 8c). In fact, the lattice parameters and ionic radii do not follow a monotonic relationship, reaching a maximum near Na content of 3–3.2 per formula unit14. To jump from one site to next one, Na+ ions must pass through a bottleneck as defined by Hong14. In the monoclinic NASICON framework, the bottleneck is a pseudo-hexagonal ring consisting of alternating three ZrO6 octahedra and three P/SiO4 tetrahedra (Fig. 8b). The bottleneck size is the principal factor controlling the activation energy and ionic conductivity. West et al.38 suggested a triangle T1 defined by the three O2− ions to characterize the bottleneck size. We analyze the bottleneck in the pathway between the Na(2) and Na(1) sites using the area of triangle T1 (Fig. 8b). It can be seen that the area of triangle T1 increases with the substitution of alkaline earth ions for Zr, and decreases with the ionic radii of alkaline earth ions (Fig. 8c), indicating that the much larger alkaline earth ions narrow the bottleneck, thus decreasing the ionic conductivity. The Zr-Mg system has the largest area of triangle T1 (~6.522 Å2) that is significantly larger than that of the pure Zr system (~5.223 Å2), explaining the maximum ionic conductivity observed for the Zr-Mg system.

In summary, here we demonstrate that the Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 with NASICON phase has superior room-temperature ionic conductivity of 3.5 × 10−3 S cm−1. We report ground-breaking progress in manufacturing a solid-state room temperature Na-S battery using Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 solid electrolyte. Initial adequate cell performance is demonstrated, and further improvement can be sought by developing hybrid positive electrodes and by achieving good electrode-electrolyte contact. Moreover, we demonstrate that the present solid-state electrolyte can efficiently depress the dissolution and shuttle of sodium polysufides which leads to better cycling stability than the liquid counterpart. The present work will help to identify new strategies for developing organic-inorganic hybrid positive electrodes and chemically stable oxide-based electrolytes for the next generation of safe and inexpensive high-performance solid state sodium batteries.

Methods

Preparation of Na3.1Zr1.95M0.05Si2PO12 (M = Mg, Ca, Sr, Ba) electrolytes

The Na3.1Zr1.95M0.05Si2PO12 (M = Mg, Ca, Sr, Ba) were synthesized through solid-state reaction combined with mechanochemical synthesis. Firstly, The Zr1.95M0.05O3.95 solid solutions were prepared through mechanochemical reaction in a high energy ball mill for 2 h (SPEX SamplePrep 8000 M Mixer). The mixture of ZrO2 (Inframat Advanced Materials, ≥99.9%) and MO was milled by alternating 30 min of milling with 30 min in standby mode to avoid excessive heating. The solid electrolytes with the formula Na3.1Zr1.95M0.05Si2PO12 (M = Mg, Ca, Sr, Ba) were synthesized through solid-state reaction by mixing stoichiometric amounts of Na2CO3 (Sigma-Aldrich, ≥99.5%), SiO2 (Sigma-Aldrich, ≥99%), NH4H2PO4 (Sigma-Aldrich, ≥98%), and Zr1.95M0.05O3.95, and ball-milling with zirconium oxide balls for 2 h. The precursors were decomposed at 900 °C for 12 h in alumina crucibles, with repeated ball-milling for 2 h. The calcined powders were then cold pressed and sintered at 1260 °C for 16 h covered with the raw powders to avoid sodium loss.

Characterization of solid electrolytes

The crystal structure was analyzed by Rietveld refinement of powder XRD data (Shimadzu XRD-6000 Cu-Kα), using GSAS software. The microstructure was examined on polished surfaces of the sintered pellet using SEM (S-4300 Shimadzu). The ionic conductivities were fixed by impedance spectroscopy measurements that were performed with a Solartron 1260+1287 System, applying AC potential of 10 mV from 32 MHz to 1 Hz in Ar atmosphere. Ion-blocking electrodes were formed by Au sputtering on both surfaces of the pellet. Measurement of DC conductivity was performed using sodium-electrolyte symmetric cell with constant current density of 44 μA cm−2 at room temperature inside an Ar-filled glove box. Sodium plates (~0.22 mm thickness) were attached to both faces of the pellet (2.0 mm thickness, 9.0 mm diameter), to serve as non-blocking electrodes. DC polarization was performed to evaluate the electronic conductivity and sodium-ion transference number. A Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 pellet (3.5 mm thickness, 9.1 mm diameter) was sputtered by Au on both surfaces and a constant voltage of 1 V was applied. Cyclic voltammetry measurements were performed using two methods. The first method was using Au/Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 pellet/Na semi-blocking cell to perform a linear sweep from −0.2 V to 9 V vs Na+/Na with varied scan rate of 1 mV s−1. The second method was using Na/Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12/Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12-carbon/Au cell to perform a linear sweep from 0 to 9 V vs Na+/Na with scan rate of 0.1 mV s−1 according to ref. 22. To make the Na/Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12/Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12-carbon/Au cell, the Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12-carbon electrode was prepared by mixing Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 powder, carbon black, polyvinylidene fluoride with a weight ratio of 36:54:10, and n-methylpyrrolidinone to an electrode slurry. The slurry was then casted onto the polished Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 pellet (~1.0 mm thickness and ~9 mm diameter) and dried at 120 °C overnight, then sputtered Au, after which, metallic sodium was attached on the other side of the pellet. The Na/Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12/Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12-carbon/Au cell was assembled using CR2025 coin cell and was performed cyclic voltammetry measurements on Solartron electrochemistry workstation.

Characterization of solid-state Na-S batteries

A solid-state sodium battery was prepared with sulphur-carbon-polymer electrolyte hybrid material as cathode, Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 ceramic pellet as electrolyte, sodium metal as anode. Firstly, the sulphur-carbon composite was prepared by mechanochemical milling with the sulphur to carbon weight ratio of 1:1 at 875 rpm for 5 h. The polymer electrolyte consisted of poly(ethylene oxide) (Sigma-Aldrich, 100 0000 g mol−1), NaClO4 (Sigma-Aldrich, ≥98%), SiO2 (Sigma-Aldrich, 5–15 nm particle size), 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(fluorosulfonyl)imide (Solvionic, H2O ≤ 20 ppm) was prepared by mechanochemical milling at 875 rpm for 1 h in a weight ratio of 0.53:0.074:0.06:1.33 in acetone. Following, the sulphur-carbon composite was added to the polymer electrolyte in a weight ratio of 1:1 and with mechanochemical milling at 875 rpm for 30 min. The slurry was then coated uniformly onto Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 ceramic pellet (~1.2 mm thickness) and dried under vacuum at 50 °C overnight. Sodium foil was attached on the other surface of the Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 ceramic pellet in Ar-filled glove box. Cell assembly was carried out in CR2025 coin cells. The charge-discharge measurements were conducted at a constant current of 8.92 μA (i.e., ~0.01C rate) with a cut-off voltage of 0.8–3.6 V on a MACCOR battery cycler at room temperature.

To evaluate the capability of present solid-state electrolyte compared with conventional liquid electrolyte, two different configuration of Na-S cells were constructed. The first type of Na-S cells used 1 M NaClO4 in ethylene carbonate (EC)/propylene carbonate (PC) (1:1 in weight) as electrolyte and Whatman GF/A fiber as separator, and the second type of Na-S cells used the present Na3.1Zr1.95Mg0.05Si2PO12 ceramic pellet (~1.0 mm thickness) as electrolyte and separator. The sulphur-carbon composite (1:1 in weight) was mixed with Super P conductive carbon (TIMCAL Ltd.) and polyvinylidene fuoride (PVDF, Sigma) at a weight ratio of 8:1:1 in N-methylpyrrolildone (NMP, Sigma) solvent to form uniform slurries and then was coated on Al foils to prepare the cathode. The cells were assmbled in Ar-filled glove box with metallic sodium as anode. To assemble cells using solid-state electrolyte, sodium was attached on a side of polished pellet and a very little drop of liquid electrolyte was used as a buffer between solid-state electrolyte and cathode. The charge-discharge measurements were conducted at a constant current of 1C and 5C rate with a cut-off voltage of 0.8–3.6 V.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Song, S. et al. A Na+ Superionic Conductor for Room-Temperature Sodium Batteries. Sci. Rep. 6, 32330; doi: 10.1038/srep32330 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by National University of Singapore, and the National Research Foundation, Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore under its Competitive Research Programme (CRP Award No. NRF-CRP 8-2011-04). This research is supported by Chongqing University, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 0241005202014, No. 0903005203403).

Footnotes

Author Contributions S.S., H.M.D., A.M.K., N.H. and L.L. conceived the ideas. S.S. performed the synthesis and characterization of materials and batteries. S.S. and L.L. analysed the data and wrote the paper. All authors discussed and commented on the paper.

References

- Hartmann P. et al. A rechargeable room-temperature sodium superoxide (NaO2) battery. Nat. Mater. 12, 228–232 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu D., Talaie E., Duffort V. & Nazar L. F. The emerging chemistry of sodium ion batteries for electrochemical energy storage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 3431–3448 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabuuchi N., Kubota K., Dahbi M. & Komaba S. Research development on sodium-Ion batteries. Chem. Rev. 114, 11636–11682 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek S. W., Lee J. M., Kim T. Y., Song M. S. & Park Y. Garnet related lithium ion conductor processed by spark plasma sintering for all solid state batteries. J. Power Sources 249, 197–206 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Wei T., Gong Y. H., Zhao X. & Huang K. An all-ceramic solid-state rechargeable Na+-battery operated at intermediate temperatures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 5380–5384 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Lalère F. et al. An all-solid state NASICON sodium battery operating at 200 °C. J. Power Sources 247, 975–980 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Noguchia Y., Kobayashi E., Plashnitsa L. S., Okadab S. & Yamaki J. Fabrication and performances of all solid-state symmetric sodium battery based on NASICON-related compounds. Electrochim. Acta 101, 59–65 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Dunn B., Kamath H. & Tarascon J.-M. Electrical energy storage for the grid: a battery of choices. Science 334, 928–935 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Z. Y., Hu Y. Y., Wu X. W., Han J. D. & Gu Z. H. Main challenges for high performance NAS battery: materials and interfaces. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 1005–1018 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Sakabe S. NAS battery fire incident and response, 28/10/2011. http://www.ngk.co.jp/english/announce/index.html (2011).

- Lu X. C. et al. Liquid-metal electrode to enable ultra-low temperature sodium-beta alumina batteries for renewable energy storage. Nat. Commun. 5, 4578–4585 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi A., Noi K., Sakuda A. & Tatsumisago M. Superionic glass-ceramic electrolytes for room-temperature rechargeable sodium batteries. Nat. Commun. 3, 856–860 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodenough J. B. Evolution of strategies for modern rechargeable batteries. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 1053–1061 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong H. Y.-P. Crystal structures and crystal chemistry in the system Nal+xZr2SixP3−xO12. Mat. Res. Bull. 11, 173–182 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- Goodenough J. B., Hong H. Y.-P. & Kafalas J. A. Fast Na+-ion transport in skeleton structures. Mat. Res. Bull. 11, 203–220 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- Song S. F., Yan B. G., Zheng F., Duong H. M. & Lu L. Crystal structure, migration mechanism and electrochemical performance of Cr-stabilized garnet. Solid State Ionics 268, 135–139 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Wells A. F. Structural Inorganic Chemistry (Oxford University Press, London, 1975). [Google Scholar]

- Thangadurai V., Narayanan S. & Pinzaru D. Garnet-type solid-state fast Li ion conductors for Li batteries: critical review. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 4714–4727 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S. F., Sheptyakov D., Korsunsky A. M., Duong H. M. & Lu L. High Li ion conductivity in a garnet-type solid electrolyte via unusual site occupation of the doping Ca ions. Materials & Design 93, 232–237 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T., Kuwabara K. & Shibata M. Solid-state ionics-conductivities of Na+ ion conductors based on NASICON. Solid State Ionics 1, 163–175 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- Thokchom J. S., Gupta N. & Kumar B. Superionic conductivity in a lithium aluminum germanium phosphate glass-ceramic. J. Electrochem. Soc. 155, A915–A920 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Han F., Zhu Y., He X., Mo Y. & Wang C. Electrochemical stability of Li10GeP2S12 and Li7La3Zr2O12 solid electrolytes. Adv. Energy Mater. 6, 1501590 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Bard A. J. & Faulkner L. R. Electrochemical methods fundamentals and applications. 2 (John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Press, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- Shin J. H. & Passerini S. PEO-LiN(SO2CF2CF3)2 polymer electrolytes V. effect of fillers on ionic transport properties. J. Electrochem. Soc. 151, A238–A245 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Bohnke O., Bohnke C. & Fourquet J. L. Mechanism of ionic conduction and electrochemical intercalation of lithium into the perovskite lanthanum lithium titanate. Solid State Ionics 91, 21–31 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Ponrouch A. et al. Towards high energy density sodium ion batteries through electrolyte optimization. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 2361–2369 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Ni’mah Y. L., Cheng M. Y., Cheng J. H., Rick J. & Hwang B. J. Solid-state polymer nanocomposite electrolyte of TiO2/PEO/NaClO4 for sodium ion batteries. J. Power Sources 278, 375–381 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Udovic T. J. et al. Exceptional superionic conductivity in disordered sodium decahydro-closo-decaborate. Adv. Mater. 26, 7622–7626 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W. et al. Liquid-like ionic conduction in solid lithium and sodium monocarba-closo-decaborates near or at room temperature. Adv. Energy Mater. 6, 1502237 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. K., Mao A., Sen S. & Kim S. Fast Na-ion conduction in a chalcogenide glass-ceramic in the ternary system Na2Se-Ga2Se3-GeSe2. Chem. Mater. 26, 5695–5699 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Hooper A. A. study of the electrical properties of single-crystal and polycrystalline β-alumina using complex plane analysis. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 10, 1487–1496 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- Coors W. G., Gordon J. H. & Menzer S. G. Electrochemical cell comprising ionically conductive membrane and porous multiphase electrode. US patent US2010/0297537A1 (2010).

- Yu X. W. & Manthiram A. Room-temperature sodium-sulfur batteries with liquid-phase sodium polysulfide catholytes and binder-free multiwall carbon nanotube fabric electrodes. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 22952–22959 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Bauer I., Kohl M., Althues H. & Kaskel S. Shuttle suppression in room temperature sodium-sulfur batteries using ion selective polymer membranes. Chem. Commun. 50, 3208–3210 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boilot J. P., Collin G. & Colomban Ph. Crystal structure of the true NASICON: Na3Zr2Si2PO12. Mat. Res. Bull. 22, 669–676 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Guin M. & Tietz F. Survey of the transport properties of sodium superionic conductor materials for use in sodium batteries. J. Power Sources 273, 1056–1064 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Du Y. A. & Holzwarth N. A. W. Li ion diffusion mechanisms in the crystalline electrolyte-Li3PO4. J. Electrochem. Soc. 154, A999–A1004 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Losilla E. R. et al. Understanding Na mobility in NASICON materials: a Rietveld, 23Na and 31P MAS NMR, and impedance study. Chem. Mater. 10, 665–673 (1998). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.