Abstract

Phosphatase and tensin homologue (Pten) suppresses neoplastic growth by negatively regulating PI(3)K signalling through its phosphatase activity1. To gain insight into the actions of non-catalytic Pten domains in normal physiological processes and tumorigenesis2,3, we engineered mice lacking the PDZ-binding domain (PDZ-BD). Here, we show that the PDZ-BD regulates centrosome movement and that its heterozygous or homozygous deletion promotes aneuploidy and tumour formation. We found that Pten is recruited to pre-mitotic centrosomes in a Plk1-dependent fashion to create a docking site for protein complexes containing the PDZ-domain-containing protein Dlg1 (also known as Sap97) and Eg5 (also known as Kif11), a kinesin essential for centrosome movement and bipolar spindle formation4. Docking of Dlg1–Eg5 complexes to Pten depended on Eg5 phosphorylation by the Nek9–Nek6 mitotic kinase cascade and Cdk1. PDZ-BD deletion or Dlg1 ablation impaired loading of Eg5 onto centrosomes and spindle pole motility, yielding asymmetrical spindles that are prone to chromosome missegregation. Collectively, these data demonstrate that Pten, through the Dlg1-binding ability of its PDZ-BD, accumulates phosphorylated Eg5 at duplicated centrosomes to establish symmetrical bipolar spindles that properly segregate chromosomes, and suggest that this function contributes to tumour suppression.

PTEN is lost, mutated or expressed at reduced levels in a large proportion of human cancers1. PTEN is a modularly structured protein that has at least five functional domains, including a phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns(4,5)P2)-binding domain, a phosphatase domain, a C2 domain, a carboxy-terminal tail region, and a PDZ-BD consisting of the last three amino acids (TKV)2. Cancer-associated mutations are located throughout the protein, implying that PTEN inhibits neoplastic growth through an intricate interplay of its catalytic and non-catalytic domains1. To further investigate this, we focused on the role of the PDZ-BD in normal biological processes and tumour suppression.

Our venture into studying the Pten PDZ-BD was initially prompted by efforts to understand the mechanistic basis for the aneuploidy phenotype of lymphocytes of Pten+/− mice5. Chromosome counts on mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) confirmed that Pten haplo-insufficiency promotes aneuploidization (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Monitoring of chromosome movements in living cells revealed that Pten+/− MEFs are prone to chromatid bridges, and misaligned and lagging chromosomes (Fig. 1a). The last two errors suggested a direct role for Pten in chromosome segregation as they result from microtubules–kinetochore malattachments rather than defects in non-mitotic processes that cause chromosome missegregation, such as unresolved stalled DNA replication forks6. Metaphase spreads of Pten+/− MEFs rarely showed double-strand DNA breaks, further supporting this notion (Supplementary Fig. 1a).

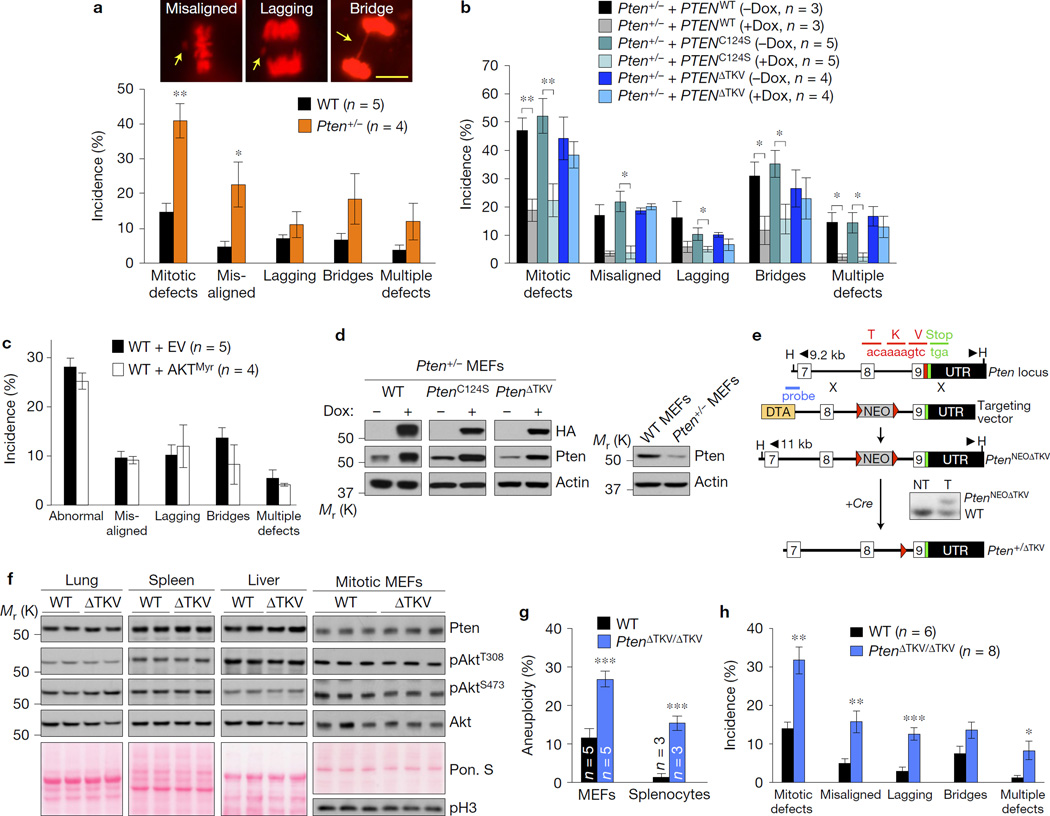

Figure 1.

The PDZ-BD of Pten is required for proper chromosome segregation. (a–c) H2B–mRFP-expressing MEF lines monitored for mitotic defects (misaligned chromosomes, lagging chromosomes and chromatin bridges) by live-cell imaging as they progress through mitosis. n, the number of independent MEF lines (18–64 cells per line). Images above the graph in a represent H2B–mRFP-expressing Pten+/− MEFs with the indicated mitotic defects (arrows). Scale bar, 10 µm. (d) Western blots of lysates from WT or Pten+/− MEFs carrying HA-tagged PTEN mutants introduced by the TRIPz (Dox-inducible) lentiviral expression system. (e) Schematic representation of the knock-in gene targeting strategy to generate Pten mutant mice lacking the PDZ-interaction motif TKV. Part of the Pten locus, the targeting vector with loxP (red triangles), HindIII (H) restriction sites, and the Southern probe are indicated. The resulting PtenNEOΔTKV allele in embryonic stem cells was identified by Southern blot analysis. Mice carrying the knock-in allele were crossed with HPRT–Cre transgenic females to generate Pten+/ΔTKV heterozygous offspring. (f) Western blots of lysates from the indicated tissues of WT and PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV (ΔTKV) mice. Ponceau S (Pon. S) staining of blotted proteins served as a loading control, and phospho-histone H3 (pH3) as a control for equal loading of mitotic cells. (g) Karyotype analysis of passage 5 MEFs and splenocytes from 5-month-old mice. n, the number of independent MEF lines or spleens (50 spreads per MEF line or spleen). (h) MEFs monitored for mitotic defects by live-cell imaging. n, the number of independent MEF lines (≥31 cells per line). Values in a–c,h represent mean ± s.e.m., and in g mean ± s.d. Statistical significance in a,g,h was determined by unpaired t-test, and statistical significance in cells transduced with virus in b,c was determined by paired t-test. *P <0.05; **P <0.01, ***P <0.001. Unprocessed original scans of blots can be found in Supplementary Fig. 6 and statistics source data in Supplementary Table 1.

To identify the Pten functional domain(s) critical for chromosome segregation in mitosis, we stably expressed HA-tagged mutant human PTEN cDNA constructs in Pten+/− MEFs and measured their ability to restore proper mitosis using live-cell imaging. As expected, full-length PTEN (PTENWT) corrected the chromosome segregation errors (Fig. 1b,d and Supplementary Fig. 1b). Near complete correction was also observed with PTENC124S, a mutant lacking phosphatase activity7. Expression of constitutively active AKT (AKTMyr)8 failed to induce chromosome missegregation in wild-type (WT) MEFs (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1c), further implying that the mitotic phenotype was not caused by uncontrolled PI(3)K/AKT signalling. In contrast, PTEN lacking the last three amino acids (PTENΔTKV) failed to revert the mitotic phenotype (Fig. 1b,d and Supplementary Fig. 1b), suggesting that Pten might cooperate with a PDZ-domain-containing protein to regulate accurate chromosome segregation.

To test this, we generated PtenΔTKV mutant mice in which the 9-nucleotide sequence that encodes for the Pten PDZ-BD was deleted from the endogenous gene locus (Fig. 1e). Mice homozygous for the PtenΔTKV allele were born from heterozygous intercrosses at Mendelian frequency and were overtly indistinguishable from WT littermates, demonstrating that loss of the PDZ-BD is inconsequential during embryogenesis. A study showing that the Pten PDZ domain mediates amyloid-β peptide neurotoxicity confirmed this9. Western blotting revealed that Pten protein levels were normal in tissues and MEFs from PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV mice (Fig. 1f). The same was true for levels of total Akt, Akt phosphorylated at Thr308 and Ser473, and key Akt targets such as S6K and 4E-BP1 (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 1d), suggesting that the PDZ-BD is dispensable for Pten protein stability and for negative regulation of PI(3)K/AKT signalling. PDZ-BD loss did not engage p53 (Supplementary Fig. 1e).

Chromosome counts on metaphase spreads of PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV MEFs and lymphocytes from 5-month-old PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV mice confirmed that PDZ-BD loss causes aneuploidy (Fig. 1g). Consistent with this, chromosome missegregation rates were significantly higher in PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV MEFs than in WT MEFs (Fig. 1h). Although PTEN has been implicated in repair of structural chromosome damage10,11, PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV MEFs were not prone to such damage (Supplementary Fig. 1f–k).

To uncover the critical PDZ-BD binding partner, we depleted PDZ-domain proteins that interact with Pten2,3 in WT MEFs and monitored the impact on chromosome segregation. Of the three proteins examined, Dlg1, but neither Par3 nor Nherf1, impacted the fidelity of chromosome segregation (Fig. 2a,b and Supplementary Fig. 2a). In complementary experiments, Dlg1−/− MEFs showed chromosome missegregation and aneuploidy phenotypes similar to PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV MEFs (Fig. 2b,c). Consistent with a prominent role for the PDZ-BD in establishing Pten–Dlg1 interaction, the amount of Dlg1 protein that immunoprecipitated with Pten from mitotic PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV MEF lysates was reduced compared with WT (Fig. 2d). These data suggested that Pten–Dlg1 complex formation occurs as part of an important step in the chromosome segregation process.

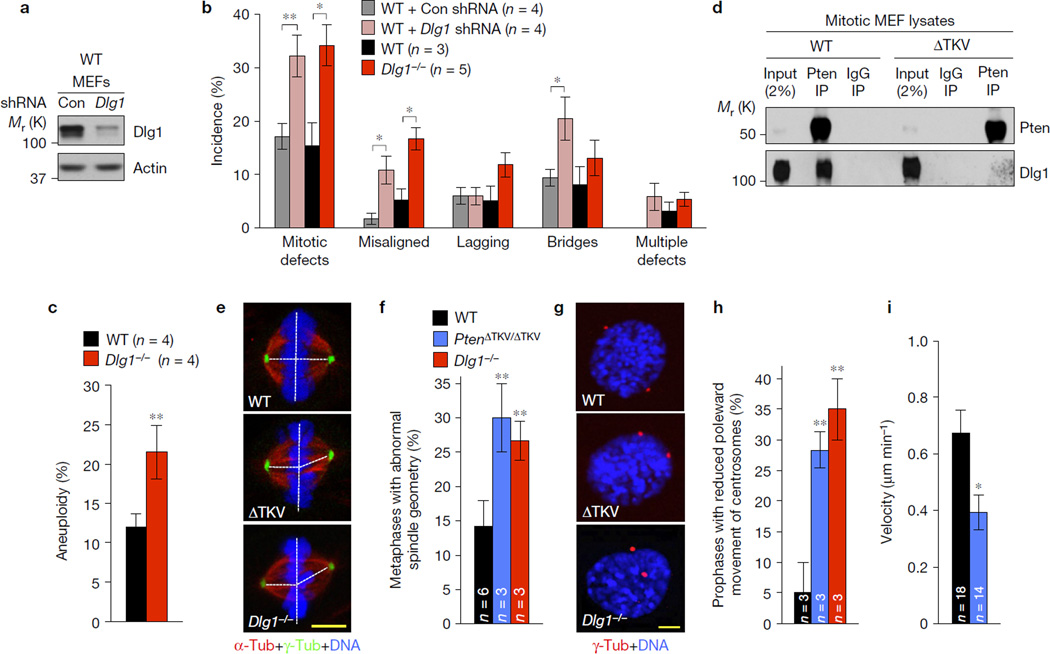

Figure 2.

Pten interacts with the PDZ-domain-containing protein Dlg1 to regulate centrosome movement during mitotic spindle assembly. (a) Western blots of lysates from WT MEFs transduced with Dlg1 shRNA or non-silencing shRNA negative control (Con) lentiviruses and analysed 72 h later. (b) MEFs monitored for mitotic defects by live-cell imaging as they progress through mitosis. n, the number of independent MEF lines (26–35 cells per line). (c) Karyotype analysis of passage 5 MEFs. n, the number of independent MEF lines (50 spreads per line). (d) Immunoblots of mitotic WT and PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV MEF extracts subjected to immunoprecipitation with Pten antibody or control IgG and analysed by immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies. Blots are representative for three independent experiments. (e) Maximum intensity projection images of MEFs in metaphase immunostained for α-tubulin (red) and γ-tubulin (green). (f) Incidence of MEFs with asymmetrical metaphase spindles. n, the number of independent MEF lines (20 cells per line). (g) Images of MEFs in prophase stained for γ-tubulin (red) and DNA (blue). (h) Prophases with reduced centrosome movement. n, the number of independent MEF lines (20 cells per line). (i) Centrosome movement rates during spindle formation (n, the number of cells analysed). Values in b,i represent mean ± s.e.m., and in c,f,h mean ± s.d. Statistical significance in cells infected with shRNA in b was determined by paired t-test; all other significance in b,c,f,h,i was determined by unpaired t-test. *P <0.05; **P <0.01. DNA in e,g was visualized with Hoechst. Scale bars, 5 µm. Unprocessed original scans of blots can be found in Supplementary Fig. 6 and statistics source data in Supplementary Table 1.

To identify this process, we screened for defects in the spindle assembly checkpoint and the error correction machinery but both seemed unperturbed in PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV MEFs (Supplementary Fig. 2b–f). Microtubule–kinetochore malattachments have been linked to spindle geometry defects originating from accelerated or delayed sister centrosome disjunction12,13. Indeed, spindle geometry defects occurred at much higher rates in PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV and Dlg1−/− metaphases than in WT metaphases, as determined by visualization of centrosomes, spindle microtubules and chromosomes (Fig. 2e,f). We screened for irregularities in sister centrosome disjunction by immunostaining PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV, Dlg1−/− and WT MEFs for γ-tubulin and p-histone H3 and measuring centrosome distance in G2 phase12, but the disjunction process seemed unaffected (Supplementary Fig. 2g).

In addition to centrosome disjunction, bipolar spindle formation involves poleward movement of separated centrosomes. We examined centrosome movement by staining centrosomes and DNA and measuring inter-centrosome distance and the nuclear diameter in prophase cells. As a measure for centrosome movement, we determined the ratio between centrosome distance and nuclear diameter. As shown in Fig. 2g,h, 5% of WT prophases had a ratio of ≤ 0.5 compared with 28% and 35% of PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV and Dlg1−/− prophases. Live-cell imaging of PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV and WT MEFs expressing γ-tubulin–cerulean and H2B–mRFP confirmed that the velocity of centrosome movement during spindle formation was significantly reduced when the PDZ-BD was lacking (Fig. 2i). Dlg1 has been implicated in planar spindle orientation through its function in recruiting the LGN complex to the cell cortex14, but this function was unperturbed in PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV MEFs (Supplementary Fig. 2h).

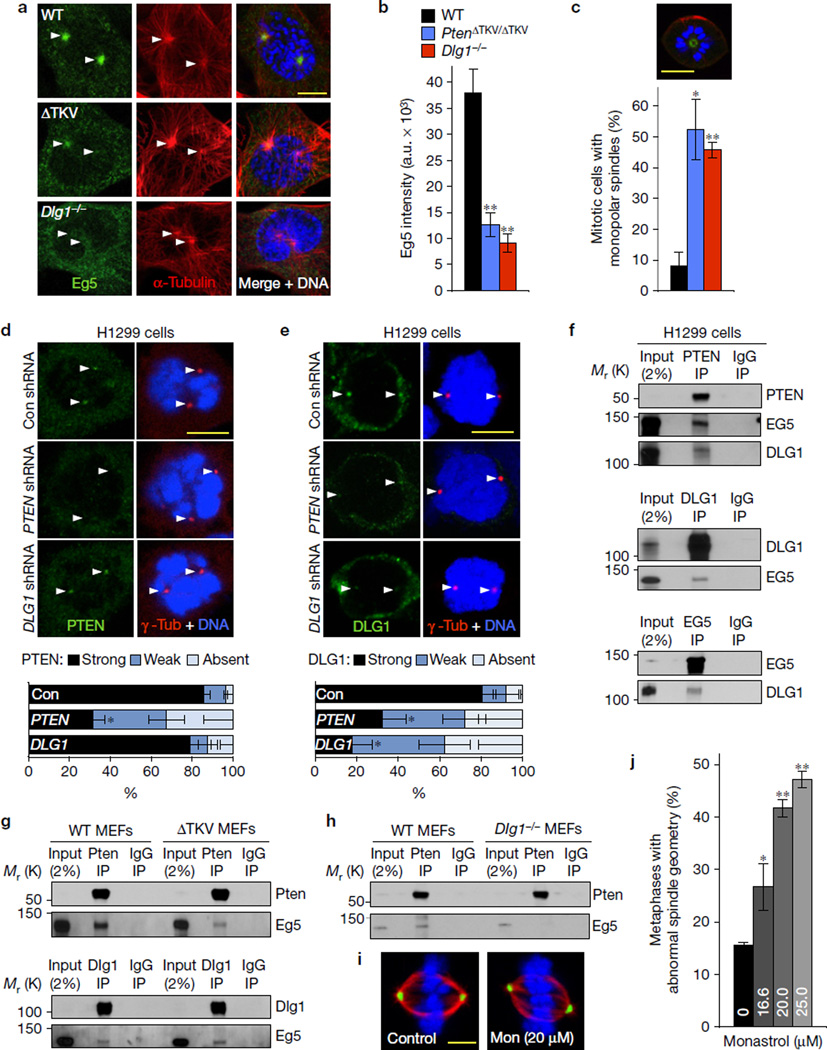

To explore how Pten and Dlg1 control centrosome movement, we focused on Eg5, a plus-end-directed kinesin that is loaded onto centrosomes in early prophase to move duplicated centrosomes to opposite sites of the cell by driving outwards microtubule sliding15. Whereas Eg5 localized to centrosomes in WT MEFs during prophase, centrosomal Eg5 signals were reduced in PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV and Dlg1−/− MEFs in prophase and beyond (Fig. 3a,b and Supplementary Fig. 3a). In contrast, Kif15, another centrosome-associated plus-end-directed mitotic kinesin, was unaffected (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Our findings predicted that PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV and Dlg1−/− MEFs would be hypersensitive to the Eg5 inhibitor monastrol16. Indeed, low amounts of monastrol (16.6 µM) that block centrosome movement in only 8% of WT cells had a profound impact in PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV and Dlg1−/− cells, with 52% and 46% of mitotic cells forming monopolar spindles, respectively (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3.

Pten at centrosomes creates a docking site for Eg5-bound Dlg1. (a) Images of MEFs in prophase immunostained for Eg5 and α-tubulin. (b) Quantification of Eg5 signal at astral microtubules and centrosomes in prophase. n=3 independent MEF lines per genotype (10–12 cells per line). (c) Incidence of mitotic MEFs with monopolar spindles in the presence of 16.6 µM monastrol. Quantifications were performed on n=3 independent MEF lines (45–47 cells per line). Top, image of a monopolar prometaphase immunostained for α-tubulin (red) and γ-tubulin (green). (d) Centrosomal PTEN levels in HT1299 cells transduced with PTEN, DLG1 or non-targeting (Con) shRNA TRC lentiviruses. Cells were immunostained for PTEN and γ-tubulin 72 h after transduction and centrosomal PTEN signals quantified. Quantifications were performed on n = 3 independent experiments (per experiment, 6–10 cells for each shRNA). (e) The same as in d but for centrosomal DLG1. Quantifications were performed on n=3 independent experiments (per experiment, 5–26 cells were analysed for each shRNA). (f) Analysis of complex formation between endogenous PTEN, DLG1 and EG5 in mitotic HT1299 cells by reciprocal co-immunoprecipitation assays. (g) The same as in f but for mitotic WT and PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV MEFs. (h) The same as in f but for WT and Dlg1−/− MEFs. Immunoblots in f–h are representative for three independent experiments. (i) Maximum intensity projection images of WT MEFs in metaphase cultured for 3 h in the absence or presence of 20 µM monastrol (Mon) and immunostained for α-tubulin (red) and γ-tubulin (green). (j) Incidence of spindle asymmetry in WT MEFs cultured in medium containing 16.6, 20 and 25 µM monastrol. Quantifications were performed on n=3 independent MEF lines (13–26 cells per line). Arrowheads in a,d,e mark centrosomes. Data in b–e represent mean ± s.e.m. and in j mean ± s.d. Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed unpaired t-test in b,c and a paired t-test in d,e,j. *P <0.05, **P <0.01. DNA in a,c–e,i was visualized with Hoechst. Scale bars, 10 µm (a,c–e) and 5 µm (i). Unprocessed original scans of blots can be found in Supplementary Fig. 6 and statistics source data in Supplementary Table 1.

A recent paper reported that PTEN localizes to centrosomes during early mitosis17, which we confirmed using HT1299 non-small cell lung carcinoma cells (Fig. 3d). PTEN depletion in these cells reduced centrosomal PTEN (Fig. 3d). DLG1 depletion had no impact on centrosomal PTEN recruitment. DLG1 also localized to mitotic centrosomes of HT1299 cells, but only when PTEN was present (Fig. 3e). PTEN, but not DLG1, localized to unseparated sister centrosomes before mitosis onset, further indicating that PTEN accumulates first and that DLG1 accumulation at centrosomes is PTEN dependent. Knockdown of PTEN or DLG1 reduced centrosomal EG5 staining during prophase (Supplementary Fig. 3c), raising the possibility that PTEN–DLG1 complex formation at centrosomes propels Eg5 loading.

Consistent with this notion, PTEN immunoprecipitates from mitotic HT1299 lysates contained both DLG1 and EG5 (Fig. 3f). Furthermore, EG5 precipitates contained DLG1, and in reciprocal experiments, DLG1 pulled down EG5 (Fig. 3f). Identical results were obtained with HeLa cells and WT MEFs (Fig. 3g and Supplementary Fig. 3d). Importantly, Pten immunoprecipitates from mitotic PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV MEF lysates contained not only reduced amounts of Dlg1 (Fig. 2d), but also Eg5 (Fig. 3g). However, removal of the PDZ-BD had no impact on the ability of Dlg1 to precipitate Eg5, indicating that Pten co-precipitation with Eg5 is Dlg1 dependent. Likewise, Pten pulled down little Eg5 from mitotic Dlg1−/− MEF lysates (Fig. 3h). Collectively, the results from our binding and localization studies indicate that complexes containing Dlg1–Eg5 load onto mitotic centrosomes through Dlg1-mediated interaction with centrosome-associated Pten. In agreement with this conclusion, WT MEFs in which we attenuated centrosome movement with low amounts of monastrol had mitotic defects reminiscent of those of PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV and Dlg1−/− MEFs (Fig. 3i,j and Supplementary Fig. 3e). Recent studies uncovered that Pten associates with APC/C through its C terminus to promote binding of the APC/C coactivator Cdh118–20, but this Pten function was PDZ-BD independent (Supplementary Fig. 3f–h).

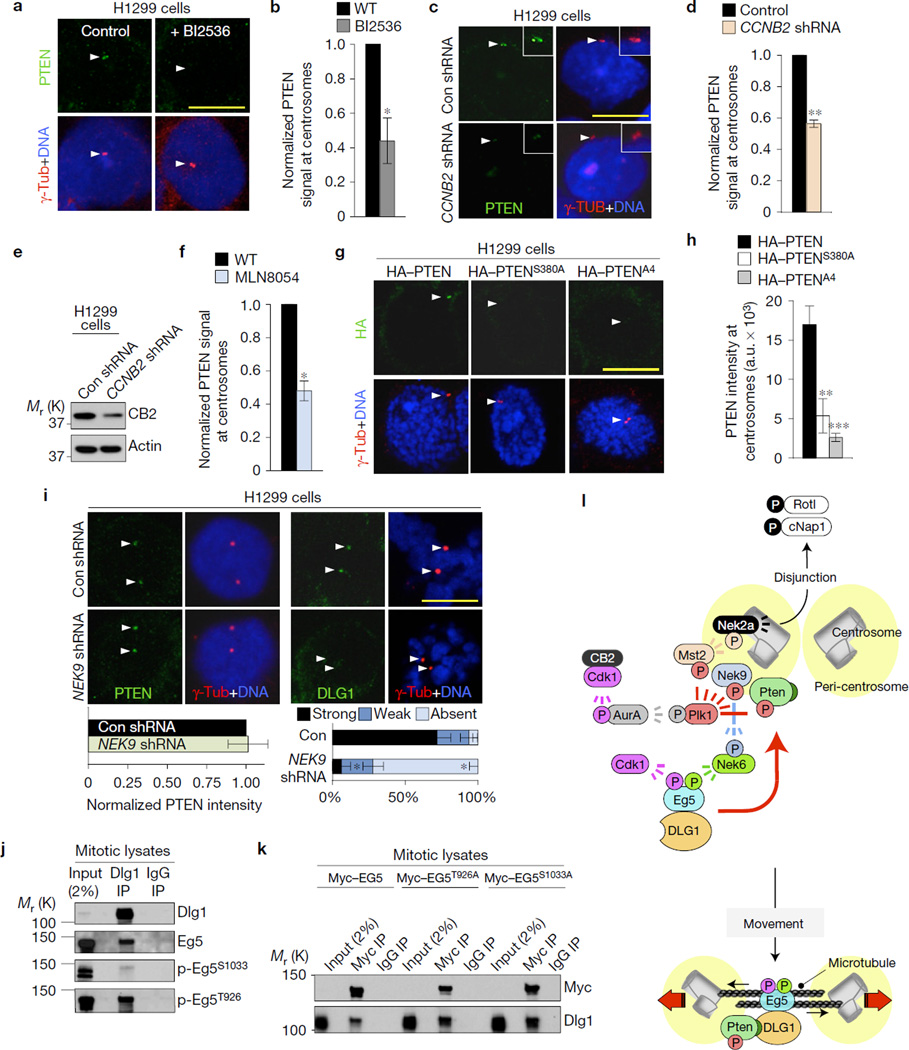

Next, we examined how PTEN gets recruited to centrosomes. We focused on the mitotic kinase PLK1 because it precipitates with PTEN (Supplementary Fig. 4a) and because it phosphorylates multiple residues in the PTEN C-tail domain near the PDZ-BD, including Ser380, Thr382 and Thr38318. Moreover, PLK1 is active at duplicated centrosomes as part of the cyclin B2/CDK1–Aurora A–PLK1–MST2–NEK2A kinase cascade that regulates disjunction of sister centrosomes through the release of rootletin and cNap112,21,22 (Fig. 4l). This led us to reason that PLK1 might act to recruit PTEN to centrosomes by phosphorylating its C-tail domain. Indeed, HT1299 cells exposed to the Plk1 inhibitor BI2536 failed to accumulate PTEN at centrosomes (Fig. 4a,b). Disruption of the kinase cascade that activates centrosome-associated PLK1 by depleting cyclin B2 or inhibiting Aurora A with MLN8054 also reduced centrosomal PTEN levels (Fig. 4c–f), further supporting our hypothesis. Furthermore, mutation of C-tail residues phosphorylated by PLK118,23 perturbed PTEN recruitment to duplicated centrosomes (Fig. 4g,h).

Figure 4.

PTEN accumulates at centrosomes following phosphorylation by PLK1 to load DLG1-bound EG5 modified by NEK9–NEK6 kinases. (a) Images of PTEN at centrosomes of HT1299 cells cultured in BI2536. (b) Quantification of centrosomal PTEN signals. n=3 experiments (10 cells per condition per experiment). (c) HT1299 cells transduced with CCNB2 or control (Con) lentiviruses and stained for PTEN after 72 h. (d) The same as in b, but for cyclin-B2-depleted cells. (e) Immunoblots of the cells used in c. (f) The same as in b but for HT1299 cells treated with MLN8054. (g) Centrosome localization of HA–PTEN, HA–PTENS380A or HA–PTENA4. (h) Quantification of HA-tagged PTEN at centrosomes, n = 15 cells per construct. (i) Prophase cells transduced with shRNAs and stained for PTEN and DLG1 72 h later. Quantifications were as described in b. (j) Immunoblots of mitotic HeLa extracts subjected to immunoprecipitation with DLG1 or control antibody and analysed with the indicated antibodies. Blots are representative for two experiments. (k) Immunoblots of mitotic HeLa cells expressing the indicated Myc constructs, immunoprecipitated with Myc antibody or control IgG and analysed for DLG1. Blots represent two independent experiments. Scale bars, 10 µm. Arrowheads in a,c,g,i mark centrosomes. Statistical significance in b,d,f,i (left panel) was determined by a one-sample t-test against a theoretical mean of unity, by unpaired t-test in h, and by paired t-test in i (right panel). All data represent mean ± s.e.m. *P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001. Unprocessed original scans of blots can be found in Supplementary Fig. 6, and source data in Supplementary Table 1. (l) Model for PTEN in centrosome movement. In late G2, a signalling cascade consisting of cyclin-B2–Cdk1, aurora A, Plk1 and Mst2 activates Nek2a, resulting in phosphorylation of Rotl and cNap1 and centrosome disjunction21,22. Besides Mst2, Plk1 phosphorylates NEK9-Thr210 and multiple residues in the carboxy-terminal tail of PTEN, resulting in accumulation of PTEN and NEK9 at centrosomes. p-NEK9T210 activates NEK6 kinase, which phosphorylates EG5 at Ser1033. EG5 is also phosphorylated by cyclin-B1–CDK1 at Thr926. Complexes of DLG1 and phosphorylated EG5 dock to the PDZ-BD of centrosome-associated PTEN, providing optimal motor protein activity for proper spindle pole movement.

EG5 loading onto centrosomes requires phosphorylation of residues Thr926 and Ser1033 by CDK1 and PLK1, respectively4,24,25. Whereas CDK phosphorylates EG5 directly4, PLK1 acts indirectly by phosphorylating NEK9, a kinase that activates NEK6, which in turn phosphorylates EG5 at Ser103325. Indeed, knockdown of NEK9 in HT1299 depleted the pool of centrosome-associated NEK9 and perturbed EG5 accumulation in early mitosis (Supplementary Fig. 4b–d). NEK9 depletion did not impact centrosomal PTEN levels (Fig. 4i) and, vice versa, PTEN depletion had no effect on centrosomal NEK9 levels (Supplementary Fig. 4e). Despite normal PTEN localization, NEK9-depleted cells failed to accumulate DLG1 at centrosomes in prophase (Fig. 4i and Supplementary Fig. 4f) indicating that phosphorylation of EG5 by the NEK9–NEK6 cascade is required for DLG1-mediated loading of EG5 onto centrosome-associated PTEN. Indeed, NEK6 depletion impaired EG5 and DLG1 accumulation at centrosomes in prophase despite normal NEK9 localization (Supplementary Fig. 4g–j). Furthermore, EG5 phosphorylated at Ser1033 precipitated with DLG1 from mitotic cell lysates (Fig. 4j). However, S1033A substitution, which interferes with centrosome association24 (Supplementary Fig. 4k), did not preclude EG5–DLG1 complex formation (Fig. 4k). Analogously, EG5 phosphorylated at Thr926 precipitated with DLG1 (Fig. 4j), as did EG5 containing a T926A substitution that interferes with centrosome accumulation (Fig. 4k and Supplementary Fig. 4k). DLG1 did not accumulate at mitotic centrosomes when cyclin B1 was depleted, suggesting that this cyclin is important for Thr926 phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. 4l). Collectively, our data best fit a model in which EG5 loading onto centrosomes requires both binding to DLG1 and phosphorylation by the NEK9–NEK6 and cyclin B1–CDK1, as well as the subsequent docking of these complexes to centrosome-associated PTEN (Fig. 4l).

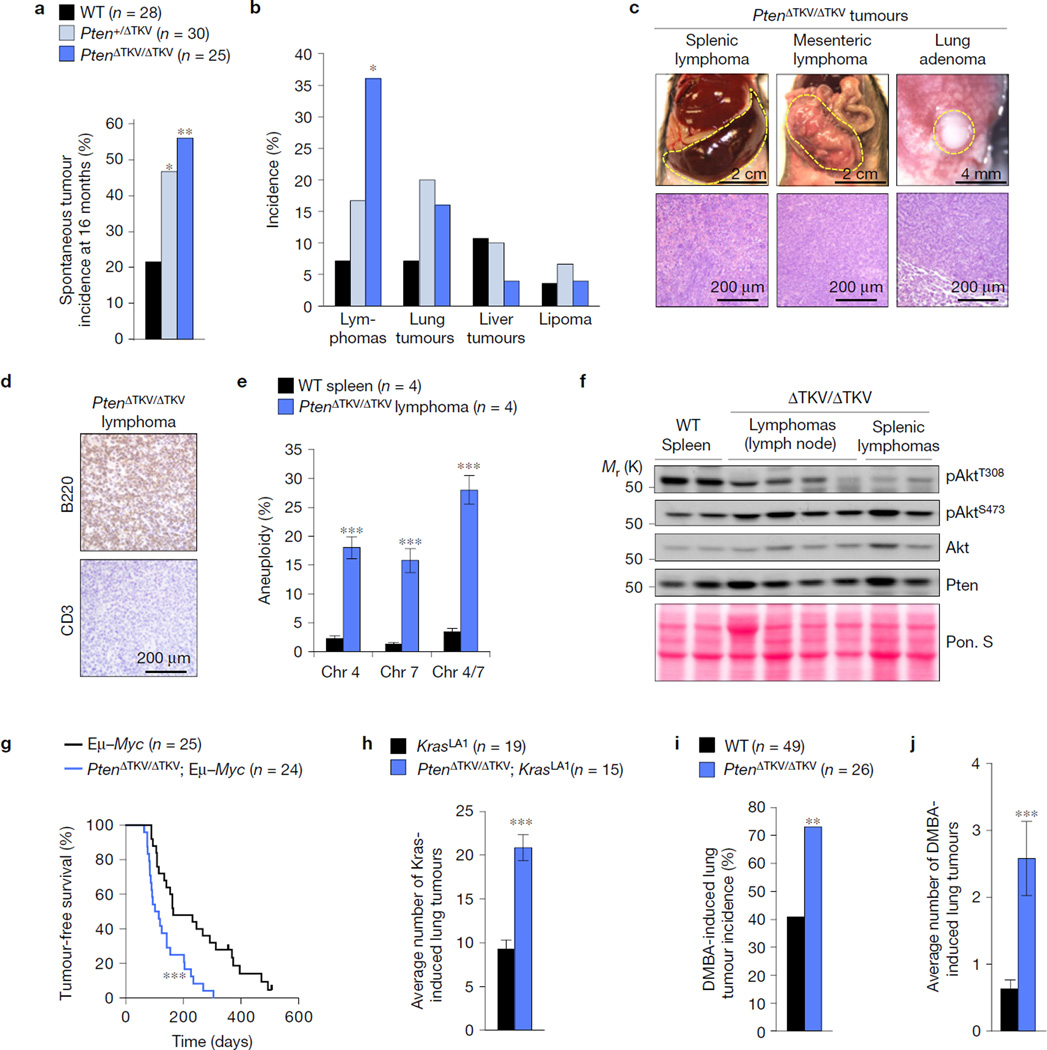

To determine whether the PDZ-BD exerts tumour suppressive activity, WT and PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV mice were euthanized at 16 months and screened for overt tumours. A cohort of Pten+/ΔTKV mice was included to examine whether tumour susceptibility increases following loss of the PDZ-BD in heterozygosity. Heterozygous and homozygous loss of the PDZ-BD both increased tumour susceptibility (Fig. 5a,b). Characterization of Pten+/ΔTKV MEFs revealed that loss of the PDZ-BD in heterozygosity reduced the amount of Pten–Dlg1 complexes (Supplementary Fig. 5a,b), yielding nearly identical mitotic phenotypes as observed in PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV MEFs (Supplementary Fig. 5c–i). This was also true for Pten+/− MEFs (Supplementary Fig. 5f–i). Thus, haplo-insufficient loss of the PDZ-BD seemingly depletes the cellular pool of Pten below a threshold level necessary to support loading of Dlg1-bound Eg5 onto centrosomes and prevent neoplastic transformation.

Figure 5.

The Pten PDZ-BD acts to suppress tumorigenesis. (a) Spontaneous tumour incidence in 16-month-old mice. (b) Spectrum of spontaneous tumour types. (c) Representative images and histological analysis of spontaneous tumours in mutant mice. (d) Paraffin section of a mesenteric lymphoma immunostained for B220 and CD3. (e) Interphase FISH for chromosomes 4 and 7 on single-cell suspensions of lymphomas from four independent PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV mice. Normal spleens from WT mice were used as controls. n, number of samples from independent mice. (f) Western blot analysis of tumour lysates probed with the indicated antibodies. Ponceau S staining of blotted proteins served as a loading control. (g) Survival curves for Eµ–Myc and PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV; Eµ–Myc mice dying of lymphomas. (h) Lung tumour burden of KrasLA1 and PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV; KrasLA1 mice. (i) Lung tumour incidence of DMBA-treated mice. (j) Average number of lung tumours in DMBA-treated mice. n in a,g–i represents the number of mice. Statistical significance was determined by Chi-square test in a,b,i, unpaired t-test in e, log-rank test in g, and non-parametric Mann Whitney test in h,j. All data presented in bar graphs represents mean ± s.e.m. *P <0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Unprocessed original scans of blots can be found in Supplementary Fig. 6 and statistics source data in Supplementary Table 1.

Splenic and mesenteric lymphomas were the most prevalent tumours in 16-month-old PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV mice (Fig. 5b,c). These lymphomas were of B cell origin and showed evidence of aneuploidy, but not uncontrolled PI(3)K/Akt signalling (Fig. 5d–f). PDZ-BD loss robustly accelerated lymphomagenesis in Eµ–Myc transgenic mice26 (Fig. 5g), underscoring its tumour suppressive role in lymphocytes. In addition, overall survival of PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV mice was reduced compared with WT controls (Supplementary Fig. 5j), which corresponded with accelerated tumour formation (Supplementary Fig. 5k). Consistent with the observed increase in lymphoma incidence at 16 months (Fig. 5b), PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV mice died from lymphoma with increased incidence and reduced latency (Supplementary Fig. 5l). PDZ-BD loss also increased lung tumour formation in KrasLA1 mice, which carry a KrasG12D allele that becomes active on intra-chromosomal homologous recombination27 (Fig. 5h). PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV mice were also highly prone to DMBA-induced lung tumours, with lung tumour incidence and multiplicity increasing approximately twofold and three-fold, respectively, compared with WT controls (Fig. 5i,j).

Our studies provide evidence that the Pten PDZ-BD has tumour suppressive activity and that loss of this domain in heterozygosity is sufficient to increase tumour susceptibility. The PDZ-BD alone produces a less profound cancer phenotype than heterozygous Pten loss28,29, Pten point mutations in the catalytic domain30 or large C-terminal truncations31, which is consistent with the idea that Pten has multiple modular tumour suppressive activities that collectively determine tumour aggressiveness30,31. PDZ-BD-mediated neoplastic transformation does not seem to involve Pten functions in APC/C activation and maintenance of structural chromosome integrity, or impairments in phosphatase activity, although catalysis-related changes at particular subcellular locations are difficult to rule out. Evidence is mounting that cancer is a potential outcome of aneuploidization32, raising the possibility that the PDZ-BD contributes to tumour suppression by mediating Eg5 loading onto centrosomes (Fig. 4l). The fact that, similar to several other aneuploidy-prone mouse models32, PDZ-BD mutant mice show increased tumorigenesis in combination with DMBA exposure, oncogenic Ras, or high Myc levels, supports this notion. However, this does not exclude the possibility that Dlg1 or other PDZ-domain-containing binding partners of Pten provide tumour suppressive functions through mechanisms other than aneuploidization2,3.

METHODS

Mouse strains

All mice were housed in a pathogen-free barrier environment. Mouse protocols were reviewed and approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All animals were maintained on a mixed 129Sv/E × C57BL/6 genetic background. Standard gene targeting and embryonic stem cell technology was used to create mice in which a 9-nucleotide sequence encoding Pten protein residues 401–403 (TKV) was removed from the endogenous Pten locus. HPRT–Cre transgenic mice were employed to remove the neomycin selection cassette used for gene targeting33. WT, Pten+/ΔTKV and PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV cohorts of mice were established from offspring of Pten+/ΔTKV intercrosses. Mice in the spontaneous tumour susceptibility study were euthanized at 16 months of age and major organs screened for overt tumours as previously described34. Tumours were collected and processed for standard histopathology by standard procedures. Survival curves were prepared on mixed gender (27 males + 14 females for WT and 55 males + 58 females for PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV) as described previously35. DMBA tumour bioassays were performed as previously described35. Eµ–Myc mice26 (a gift from R. Bram, Mayo Clinic, USA) were bred with PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV mice to generate cohorts consisting of Eµ–Myc, and PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV; Eµ–Myc mice. These mice were monitored biweekly and screened for lymphomas when moribund. KrasLA1 mice27 (obtained from the NCI mouse repository) were bred with PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV mice to produce KrasLA1 and PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV; KrasLA1 mice. At 6 weeks of age, these mice were killed and lung tumours counted under a dissection microscope. Pten+/− mice36 were obtained from the NCI mouse repository and Dlg1+/− mice37 from Jackson laboratories. No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. The experiments were not randomized. The investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Cell culture, plasmids and knockdown experiments

Pten+/−, PtenΔTKV/ΔTKV, Pten+/ΔTKV and Dlg1−/− MEFs were generated and cultured as previously described34. Mitotic MEFs were prepared by shake off as previously described38. HT1299 cells were cultured in RPMI medium with 10% FCS. 800 pSG5L HA–PTEN WT, 811 pSG5L HA–PTENC124S, 977 pSG5L HA–PTENA4 and 996 pSG5L HA–PTENS380A were gifts from W. Sellers, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, USA (Addgene plasmids 10750, 10744, 10753 and 10755, respectively). These plasmids were used to subclone HA-tagged wild-type, C124S and 1TKV human PTEN cDNAs into lentiviral expression vector TRIPz3 for Dox-inducible expression in primary MEFs. HA-tagged AKTMyr and PTEN–EGFP were purchased from Addgene (plasmids 49186 and 13039, respectively) and were cloned into the TSIN lentiviral expression vector. MEFs transduced with TRIPz- and TSIN-derived viruses were selected in 2 µg ml−1 puromycin and 300 µg ml−1 hygromycin, respectively. Myc–EG5, Myc–EG5T926A and Myc–Eg5S1033A were a gift from J. Roig25, IRB Barcelona, Spain, and were transiently transfected into HeLa cells using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen). Dlg1 (V3LMM_468003 and V3LMM_468001), Par3 (V3LMM_442113, V3LMM_442114 and V3LMM_463325), Nherf1 (V3LMM_473792 and V3LMM_473794), and non-silencing control shRNAs (RHS4346) in GIPz were purchased from Open Biosystems and lentiviruses prepared according to the manufacturer’s manual. Murine Ccnb2 (NM_007630; TRCN0000317396) and Nek9 (NM_145138; TRCN0000027595) and human DLG1 (NM_004087; TRCN0000006102, TRCN0000006103 and TRCN0000006104), PTEN (NM_000314; TRCN0000002747, TRCN0000002745 and TRCN0000002749), CCNB1 (NM_031966; TRCN0000045290), NEK6 (NM_014397; TRCN0000001724, TRCN0000001727), and non-silencing control human shRNAs in TRC2 (SHC202) were purchased from Sigma and lentiviruses prepared according to the manufacturer’s manual. Owing to cross-reactivity, murine Ccnb2 and Nek9 shRNA were able to knockdown the respective endogenous levels in human cells. MEFs, HeLa or HT1299 cells were infected with shRNAs or non-targeting shRNA as a control for 48 h (every 24 h virus-containing medium was refreshed), selected in 2 µg ml−1 puromycin for 24–48 h and analysed over the next 48 h for knockdown experiments. As a negative control for the murine experiments, we used Open Biosystem non-silencing shRNA (RHS4346) and shRNA that failed to give a reduction in protein level (V2LMM_19663 for Dlg1; and V3LMM_463326 for Par3). For the human shRNA experiments, we used non-silencing shRNA TRC2 negative control vector (SHC202). No cell lines used in this study were found in the database of commonly misidentified cell lines that is maintained by ICLAC and NCBI Biosample. Cell lines used (other than MEFs) were authenticated by short tandem repeat profiling analysis by ATTAC and were tested for mycoplasma contamination.

Aneuploidy analyses

Chromosome counts were performed on metaphase spreads from colcemid-treated MEFs or on splenocytes of 5-month-old mice as previously described34. Interphase FISH analysis with probes for chromosomes 4 and 7 was carried out on single-cell suspensions of various tissues and tumours as previously described5.

Live-cell imaging

Chromosome segregation errors and mitotic checkpoint function were assessed in living cells according to previously published methods34. For analysis of chromosome segregation errors in the presence of low amounts of monastrol, 16.6 or 18 µM of the Eg5 inhibitor was added to the culture medium immediately before initiation of live-cell imaging. All live-cell-imaging experiments were performed on at least three independent MEF lines.

Centrosome separation and spindle geometry measurements

For centrosome distance measurements in G2 and prophase, cells were stained for pH3S10/γ-tubulin/Hoechst, and images were taken by laser-scanning microscopy of cells with centrosomes in the same focal plane. The distance between centrosomes (γ-tubulin signals) was measured using ZEN software (Zeiss). G2 cells with centrosome distances ≥3 µm were classified as accelerated. Prophases with centrosome distance/nuclear diameter ratio ≤0.5 were considered delayed. Centrosome movement was determined by live-cell imaging of immortalized (SV40-LT antigen) MEFs expressing cerulean–γ tubulin and histone 2B–mRFP. For velocity measurements, we calculated the ratio of the maximum distance travelled by sister centrosomes before NEBD and the time elapsed. We included only data for distances above 3 µm to ensure that centrosome movement had commenced. For spindle geometry analysis, serial optical sections were collected from γ-tubulin/α-tubulin-stained MEFs using a laser-scanning microscope. After maximum intensity projection, ZEN software (Zeiss) was used to measure the angle between the spindle and the metaphase plate. Cells that had an acute angle between the spindle pole axis and the metaphase plate of less than 85° were considered asymmetrical. For spindle positioning measurements, serial optical sections at 0.3 µm intervals were collected from γ-tubulin-stained MEFs by confocal microscopy. The spatial positioning of centrosomes was determined by measuring the angle between the centrosome axis and the growth surface (substratum) in metaphase cells using Zen software (Zeiss). Angles were measured in orthogonal (Y and Z) edge views of vertical planes from z-stack series of ten cells from three independent MEF cell lines.

Immunostaining and confocal microscopy

Indirect immunofluorescence was carried out as described previously34. For Eg5, Kif15, γ- and α-tubulin staining, cells were fixed in PBS/1% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 5 min at room temperature, followed by ice-cold methanol for 10 min and permeabilization with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature. For p-Nek9T210 staining, cells were fixed in ice-cold methanol for 10 min and permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature. For PTEN and DLG1 staining, HT1299 cells were first permeabilized in PHEM buffer (25 mM HEPES, 10 mM EGTA, 60 mM PIPES, and 2 mM MgCl2, pH 6.9) containing 0.2% Triton X-100 for 5 min at room temperature and then fixed in ice-cold methanol for 10 min at room temperature. For p-Aurora, p-Knl1 and p-CenpA staining, cells were fixed in PBS/1% PFA for 5 min at room temperature and permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature. For visualization of PTEN–EGFP and γH2AX, and for 53 BP1 and γ-H2AX cells were fixed in PBS/3% PFA for 15 min and 12 min at room temperature, respectively, followed by 15 minutes of permeabilization in 0.2% Triton X-100. A laser-scanning microscope (LSM 510 or LSM 780; Carl Zeiss) with an inverted microscope (Axiovert 100 M; Zeiss) was used to analyse immunostained cells and capture images. Quantifications of centrosomal PTEN, DLG1, Eg5 and Kif15 signals, and centromeric p-Aurora, p-CenpA and p-Knl1 signals were carried out using ImageJ software (NIH). Confocal microscopy images were converted to eight-bit greyscale, centromere areas or centrosome edges were traced and the mean pixel intensity density (a.u.) within the marked area was calculated. All confocal images are representative of at least three independent experiments. The following inhibitors were used for 2–5 h before HT1299 fixation: 100 nM Plk1 inhibitor BI2536 and 1 µM Aurora A inhibitor MLN8054 (Selleck Chemicals). Primary antibodies for immunostaining were as follows: rabbit anti-Eg5 (1:100, TA301478, Origene); rabbit anti-Kif15 (1:200, bs-7804R, Bioss); mouse anti-Pten (1:25, ABM-2052, Cascade BioScience); mouse anti-Dlg1/SAP97 (1:25, ab69737, Abcam); rabbit anti-p-Aurora (1:100, 2914, Cell Signaling Technology); mouse or rabbit anti-γ-tubulin (1:300, T6557/clone GTU-88 or T5192, Sigma-Aldrich); mouse anti-α-tubulin (1:1,000, T9026/clone DM1A, Sigma-Aldrich); human anti-centromeric antibody (1:100, 15-234-0001, Antibodies); mouse anti-p-histone H2AX (1:500, 05–636, Millipore); rabbit anti-53BP1 (1:500, NB100-305, Novus Biologicals); rabbit anti-p-CenpA (1:250, 04–792, Millipore); p-histone H3Ser10 (1:1,000, 06–570, Millipore); rabbit anti-HA (1:100, 3724, Cell Signaling Technology); rabbit p-Nek9T210 (1:1,000, a gift from J. Roig, IRB Barcelona, Spain); mouse Myc-Tag (1:1,000, 2276S, Cell Signaling Technology); and rabbit anti-p-Knl1 (1:2,000, a gift from I. Cheeseman, Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, USA)39.

Western blot analysis, immunoprecipitations and immunohistochemistry

Western blot analysis and immunoprecipitations were carried out as previously described35. Antibodies used were as follows: HA (12013819001, Roche); Pten (9559L, Cell Signaling Technology); Dlg1 (Ab69737, Abcam); Eg5 (TA301478, Origene); p-Eg5T927 (620502, BioLegend); p-Eg5S1033 (a gift from J. Roig, IRB Barcelona, Spain); IgG (0107-01 and 0111-01, Southern Biotech); p-AKTT308 (2965, Cell Signaling Technology); p-AKTT473 (9271, Cell Signaling Technology); Akt (9272 Cell Signaling Technology); p-PtenS380 (9551, Cell Signaling Technology); Cdh1 (Ab3242, Abcam); Cdc27 (610455, BD Biosciences); p53 (SC-6243, Santa Cruz Biotechnology); Plk1 (SC-8358, Santa Cruz Biotechnology); Aurora B (611083, BD Biosciences); p-AuroraT232 (2914, Cell Signaling Technology); cyclin A240; cyclin B1 (4138, Cell Signaling Technology); cyclin B2 (C-22776, Santa Cruz Biotechnology); p4E-BP1 (9451, Cell Signaling Technology); pS6K (9234, Cell Signaling Technology); Myc-Tag (2276S, Cell Signaling Technology); NEK6 (133494, Abcam); and NEK9 (SC-100401, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Equal loading was confirmed by using antibodies against β-actin (A5441, Sigma) or p-histone H3Ser10 (06–570, Millipore), or by Ponceau S staining. Immunohistochemistry for B220 (550286, BD Biosciences) and CD3 (Ab5690, Abcam) was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded lymphoma sections using low-pH antigen retrieval buffer and labelled avidin as per the manufacturer’s instructions (Vector Laboratories).

DNA fibre assays

For DNA fibre assays, 2.5 × 105 cells were plated in each well of a 6-well plate. Two days later, cells were pulse-labelled with 50 µM CIdU (C6891, Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min, washed with pre-warmed PBS, and pulsed with 250 µM IdU (I7125, Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min. Cells were collected by trypsinization, resuspended in 500 µl ice-cold PBS, spotted on a glass slide, and incubated with 15 µl of fibre lysis solution (200 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 50 mM EDTA, and 0.5% SDS) for 8 min at room temperature. Slides were set to dry under a 45° angle to spread the fibres. Slides were then incubated in methanol–acetic acid (3:1) fixative for 10 min, washed three times with PBS, and incubated in 2 M HCl for 80 min for DNA denaturation. After washing with PBS, the slides were blocked in PBS/5% BSA for 30 min and incubated overnight with the following antibodies: rat anti-BrdU monoclonal antibody (for visualization with CldU; 1:1,000, clone BU1/75, AbD Serotec), and mouse anti-BrdU monoclonal antibody B44 (for visualization of IdU; 1:25, Becton Dickinson). Slides were then washed three times with PBS, incubated with AlexaFluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rat and AlexaFluor 594-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Molecular Probes) secondary antibodies for 1 h, and further processed for fluorescent microscopy as previously described34. Experiments were conducted on three independent MEF lines per genotype.

Statistics and reproducibility

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 or Microsoft Excel software. All results are presented in graphs are the mean ± s.e.m. of at least three independent experiments, unless otherwise noted in the figure legends. Each exact n value is indicated in the corresponding figure legend. No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. No samples or animals were excluded from the analyses, and the animals were not randomized. The investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment. A two-tailed unpaired t-test was used for comparisons in the following: Figs 1a,g,h, 2b,c,f,h,i, 3b,c, 4h and 5e and Supplementary Figs 1a,f–k, 2a–h, 3a,b, 4c,g and 5c,d,f–h. A paired t-test was used in Figs 1b,c, 2b, 3d,e,j and 4i and Supplementary Figs 3e and 4f,i,j and l. A Chi-square test was used in Fig. 5a,b,i. A non-parametric Mann–Whitney test was used in Fig. 5h,j. A log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test was used in Fig. 5g and Supplementary Fig. 5j–l. A one-sample t-test against a theoretical mean of unity was used for comparisons in Fig. 4b,d,f,i, and Supplementary Figs 3c, 4d,e,h and 5b and i. Western blot, immunoprecipitation and immunofluorescence data presented are representative of at least three independent experiments that yielded similar results, unless otherwise noted in the figure legends.

Data availability

All source data for preparation of graphs and for statistical analysis can be found in Supplementary Table 1. All other relevant data that support the conclusions of the study are available from the authors on request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank W. Zhou and M. Li of Mayo Clinic’s Gene Knockout Mouse Core Facility for embyronic stem cell microinjection and chimaera breeding, and A. Alimonti, P. Galardy, D. Baker, R. Naylor and members of the van Deursen laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript and for providing helpful comments and discussion. We are grateful to J. Roig for providing various critical reagents. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (CA168709 to J.M.v.D.).

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary Information is available in the online version of the paper

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.M.v.D. and J.H.v.R. conceived the project. J.H.v.R., H.-J.N. and K.B.J. performed the experimental work. A.K. performed DNA replication and damage analyses. All authors analysed the data and prepared figures. J.M.v.D., J.H.v.R. and H.-J.N. wrote the manuscript and all authors edited the manuscript. J.M.v.D. supervised all aspects of the project.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Chalhoub N, Baker SJ. PTEN and the PI3-kinase pathway in cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2008;4:127–150. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Song MS, Salmena L, Pandolfi PP. The functions and regulation of the PTEN tumour suppressor. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:283–296. doi: 10.1038/nrm3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonifant CL, Kim JS, Waldman T. NHERFs, NEP, MAGUKs, and more: interactions that regulate PTEN. J. Cell Biochem. 2007;102:878–885. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blangy A, et al. Phosphorylation by p34cdc2 regulates spindle association of human Eg5, a kinesin-related motor essential for bipolar spindle formation in vivo. Cell. 1995;83:1159–1169. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90142-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker DJ, Jin F, Jeganathan KB, van Deursen JM. Whole chromosome instability caused by Bub1 insufficiency drives tumorigenesis through tumor suppressor gene loss of heterozygosity. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:475–486. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawabata T, et al. Stalled fork rescue via dormant replication origins in unchallenged S phase promotes proper chromosome segregation and tumor suppression. Mol. Cell. 2011;41:543–553. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramaswamy S, et al. Regulation of G1 progression by the PTEN tumor suppressor protein is linked to inhibition of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:2110–2115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kohn AD, Takeuchi F, Roth RA. Akt, a pleckstrin homology domain containing kinase, is activated primarily by phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:21920–21926. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.21920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knafo S, et al. PTEN recruitment controls synaptic and cognitive function in Alzheimer’s models. Nat. Neurosci. 2016;19:443–453. doi: 10.1038/nn.4225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bassi C, et al. Nuclear PTEN controls DNA repair and sensitivity to genotoxic stress. Science. 2013;341:395–399. doi: 10.1126/science.1236188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen WH, et al. Essential role for nuclear PTEN in maintaining chromosomal integrity. Cell. 2007;128:157–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nam HJ, van Deursen JM. Cyclin B2 and p53 control proper timing of centrosome separation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014;16:538–549. doi: 10.1038/ncb2952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silkworth WT, Nardi IK, Paul R, Mogilner A, Cimini D. Timing of centrosome separation is important for accurate chromosome segregation. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2012;23:401–411. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-02-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saadaoui M, et al. Dlg1 controls planar spindle orientation in the neuroepithelium through direct interaction with LGN. J. Cell Biol. 2014;206:707–717. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201405060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cross RA, McAinsh A. Prime movers: the mechanochemistry of mitotic kinesins. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014;15:257–271. doi: 10.1038/nrm3768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayer TU, et al. Small molecule inhibitor of mitotic spindle bipolarity identified in a phenotype-based screen. Science. 1999;286:971–974. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5441.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leonard MK, Hill NT, Bubulya PA, Kadakia MP. The PTEN-Akt pathway impacts the integrity and composition of mitotic centrosomes. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:1406–1415. doi: 10.4161/cc.24516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi BH, Pagano M, Dai W. Plk1 protein phosphorylates phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) and regulates its mitotic activity during the cell cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:14066–14074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.558155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi BH, Pagano M, Huang C, Dai W. Cdh1, a substrate-recruiting component of anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) ubiquitin E3 ligase, specifically interacts with phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) and promotes its removal from chromatin. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:17951–17959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.559005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song MS, et al. Nuclear PTEN regulates the APC-CDH1 tumor-suppressive complex in a phosphatase-independent manner. Cell. 2011;144:187–199. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mardin BR, Schiebel E. Breaking the ties that bind: new advances in centrosome biology. J. Cell Biol. 2012;197:11–18. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201108006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruinsma W, Raaijmakers JA, Medema RH. Switching Polo-like kinase-1 on and off in time and space. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2012;37:534–542. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vazquez F, Ramaswamy S, Nakamura N, Sellers WR. Phosphorylation of the PTEN tail regulates protein stability and function. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;20:5010–5018. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.14.5010-5018.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith E, et al. Differential control of Eg5-dependent centrosome separation by Plk1 and Cdk1. EMBO J. 2011;30:2233–2245. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bertran MT, et al. Nek9 is a Plk1-activated kinase that controls early centrosome separation through Nek6/7 and Eg5. EMBO J. 2011;30:2634–2647. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harris AW, et al. The E mu-myc transgenic mouse. A model for high-incidence spontaneous lymphoma and leukemia of early B cells. J. Exp. Med. 1988;167:353–371. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.2.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson L, et al. Somatic activation of the K-ras oncogene causes early onset lung cancer in mice. Nature. 2001;410:1111–1116. doi: 10.1038/35074129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Cristofano A, Pesce B, Cordon-Cardo C, Pandolfi PP. Pten is essential for embryonic development and tumour suppression. Nat. Genet. 1998;19:348–355. doi: 10.1038/1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whang YE, et al. Inactivation of the tumor suppressor PTEN/MMAC1 in advanced human prostate cancer through loss of expression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:5246–5250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Papa A, et al. Cancer-associated PTEN mutants act in a dominant-negative manner to suppress PTEN protein function. Cell. 2014;157:595–610. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun Z, et al. PTEN C-terminal deletion causes genomic instability and tumor development. Cell Rep. 2014;6:844–854. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holland AJ, Cleveland DW. Losing balance: the origin and impact of aneuploidy in cancer. EMBO Rep. 2012;13:501–514. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- 33.Tang SH, Silva FJ, Tsark WM, Mann JR. A Cre/loxP-deleter transgenic line in mouse strain 129S1/SvImJ. Genesis. 2002;32:199–202. doi: 10.1002/gene.10030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeganathan K, Malureanu L, Baker DJ, Abraham SC, van Deursen JM. Bub1 mediates cell death in response to chromosome missegregation and acts to suppress spontaneous tumorigenesis. J. Cell Biol. 2007;179:255–267. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200706015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baker DJ, et al. Increased expression of BubR1 protects against aneuploidy and cancer and extends healthy lifespan. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013;15:96–102. doi: 10.1038/ncb2643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Podsypanina K, et al. Mutation of Pten/Mmac1 in mice causes neoplasia in multiple organ systems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:1563–1568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou W, et al. GluR1 controls dendrite growth through its binding partner, SAP97. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:10220–10233. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3434-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ricke RM, Jeganathan KB, Malureanu L, Harrison AM, van Deursen JM. Bub1 kinase activity drives error correction and mitotic checkpoint control but not tumor suppression. J. Cell Biol. 2012;199:931–949. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201205115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Welburn JP, et al. Aurora B phosphorylates spatially distinct targets to differentially regulate the kinetochore-microtubule interface. Mol. Cell. 2010;38:383–392. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eblen ST, Fautsch MP, Anders RA, Leof EB. Conditional binding to and cell cycle-regulated inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase complexes by p27Kip1. Cell Growth Differ. 1995;6:915–925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All source data for preparation of graphs and for statistical analysis can be found in Supplementary Table 1. All other relevant data that support the conclusions of the study are available from the authors on request.