Abstract

The impetus for the Perioperative Nurse Liaison (PNL) program at our cancer center was to reduce anxiety for family members of patients undergoing surgery by improving communication between the family and the perioperative team. The purpose of our quality improvement project was to increase contact with family members during the patient’s surgery and to support families and surgeons during the postoperative family consult when findings were unexpected. After implementing process changes, the PNLs evaluated the program using a short survey given to families after the postoperative consult. Families reported a reduction in stress and anxiety when receiving intraoperative updates either in person or by telephone. In addition, when the PNL accompanied family members to the consult, the family felt supported when receiving unexpected findings. Further, family contact increased from 82% to 98% and consults with surgeons that included the PNL rose from an average of 254 to 500 per year.

Keywords: nurse liaison, perioperative nursing, liaison, professional-family relations communication, collaboration

INTRODUCTION

A diagnosis of cancer or its recurrence is life altering for patients and families. Personnel at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) developed a Perioperative Nurse Liaison (PNL) program to assist families with the anxiety they may feel while their loved one is undergoing surgery. During the surgical procedure, a family is able to share their anxiety and fears with the PNL while waiting for the surgeon to discuss the surgical outcome. The PNL program at MSKCC consists of three masters prepared nurses who maintain specialty certification, including two Clinical Nurse Specialists and one medical-surgical RN.

The construction and relocation of 21 new ORs at MSKCC created an opportunity for the PNLs to reevaluate their clinical practice of intraoperative and postoperative communication. Personnel in our facility’s nursing education department facilitated formation of a task force that included representatives from every perioperative department and was led by the OR nursing and surgical directors. In preparation for the new ORs and family waiting rooms, the nursing education department administered a survey to families in the surgical waiting area asking them to express and prioritize their needs on the day of the patient’s surgery. The findings of this assessment suggested that the most important service was the personal touch of the PNL. Families also identified having private areas to speak to surgeons postoperatively, and visiting their family member in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) as high priorities.1 The PNLs carefully examined the results of this survey and focused on the areas identified by families as the most important, including improving the gap in intraoperative communication when families are not present at the facility, and fostering support for those families receiving untoward news without the liaison present.

DESCRIPTION OF THE PROBLEM

In the past, the PNLs at our facility reached out only to family members who were present at the facility on the day of surgery. Telephone updates were provided only when specified caregivers were identified by the physician’s office or the Pre Surgical Center (PSC) nurse. No updates were provided for relatives who were not present at the facility. The PNLs kept yearly statistics on all families who received updates on surgery status, which captured an average of 70% to 80% of our total surgical patients’ families.

Postoperative communication was fragmented and presented another challenge for the PNLs. Some surgeons called the surgical waiting area to speak with families over the telephone, while others met with families in the waiting area, neither of which respected the need of the family for privacy. Some surgeons collaborated with the PNLs to arrange for a private area to speak to the family and arranged for the PNL to be present during the discussion when the expected outcome of the surgery had not been met, but this practice was inconsistent. If the PNL was not present, personnel at the information desk would call the PNLs if families were visibly upset after speaking with the surgeon either in person or over the telephone. After discussions with the surgeons, families often needed further clarification and emotional support.

Before the improvements in the PNL’s project were implemented, multiple practices occurred that could potentially cause stress and anxiety for patient’s family members. Families may have missed the postoperative report from the surgeon, either in person or via the telephone. When a telephone report was given to only one family member, other family members complained that they did not have an opportunity to discuss the surgical outcome. In addition, when the surgeon gave a family untoward news in the waiting area, the lack of privacy for families meant they grieved openly, which added to their distress and that of others in the waiting area.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Several published articles describe surgical nurse liaison programs. Studies completed by Leske2,3 in 1993 and 1996 remain the only studies on the effects of surgical waiting on family members that use a validated anxiety scale known as the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI).4 In her replicated study in 1996, Leske examined how the intervention of an in-person intraoperative progress report affected the STAI scores of families waiting during surgery. The results showed that families who were updated in-person during surgery reported significantly lower anxiety levels than those who received telephone updates or no updates at all.3

The evaluation of several PNL (also called Surgical Nurse Liaison) programs highlight that sharing information with family members who are waiting reduces anxiety and increases family satisfaction.5–10 Stephens-Woods5 discussed that the PNL may, if requested, accompany the physician when speaking with family members about the procedure, diagnosis, or surgical outcome. Cunningham et al6 showed that surgeons feel supported by PNLs during family consults. In 2014, Herd and Rieban7 reported that PNLs who are present during family and physician interactions can help provide further clarification or answer questions after the surgeon leaves the consult. Perioperative nurse liaisons at Boston Children’s Hospital inform the surgeon of any particular family concerns before the surgeon meets with the family for a consult.8 When surgeons do not allow the PNL to reveal important surgical information, such as diagnoses, changes in the procedure, or unexpected news to the families, the lack of sharing key information can be a major frustration to both the nurse and family.9

QUALITY IMPROVEMENT PROJECT

To improve the support structure for patients’ families at our facility, the PNLs began a quality improvement (QI) project, the goal of which was to individualize a plan of care to increase the percentage of families’ seen in person or contacted by telephone by the PNL from 70–80% to 95%. The PNLs conducted the project in a 473-bed, comprehensive cancer center in New York City, where surgery length can be as short as one hour or as long as 16 hours depending on the complexity of the procedure. From 2006–2012 the number of OR procedures covered by PNLs increased from 10,075 to 13,000.

Process Improvements

The objective of our QI project was to address the inconsistency in the delivery of information by both the PNLs and surgeons. The following new processes were implemented to improve communication with patients’ families:

patients are asked to identify a primary care partner (ie, family member, friend, caregiver) to whom the PNLs will provide updates either in person or by telephone;

the PSC staff provide all family members who are present at the facility with a fact card that includes important information (eg, location of waiting areas, postoperative visitation guidelines) and a telephone number to contact the PNLs;

the PNLs strive to contact 95% of patient-designated family members during the hours of 7:00 AM to 8:30 PM;

the PNLs follow newly created unit guidelines in an effort to standardize consults with surgeons when they need to speak with the family intraoperatively, such as when the surgical plan changes, an unexpected event occurs (eg, reaction to anesthesia, code), or the PNL feels the family may need additional support; and

the PNLs accompany the family for the first postoperative bedside visit with the surgeon when unexpected or untoward news has been given.

Goals

Our goals were to provide information to all family members by contacting them every two hours in the waiting area either in person or by telephone, thus creating a support system for patient’s family members. We also wanted to create a consistent and supportive environment for families receiving unexpected or untoward news. This involved creating specific criteria that described the circumstances in which the PNLs should be notified of consults.

Project Methods

To gauge satisfaction with the newly implemented process, the PNLs designed a five question survey for the family members of surgical patients (Figure 1). The PNLs at our facility developed the survey, and the nursing research director reviewed its content. The Institutional Review Board/Privacy Board granted this project exempt status. A per diem PNL, who was the unbiased data collector, distributed a survey packet to families that included a letter to introduce the purpose of the survey and explained that participation was voluntary. An anonymous self-report questionnaire was provided with a return envelope. The data collector approached each family to complete the survey after their in-person postoperative consult with the surgeon. Respondents sealed their surveys in the provided envelope to maintain anonymity, and returned their completed surveys to the data collector before the patient was transferred out of perioperative services. The data collector worked 12 hour shifts and remained at the concierge desk to approach the families. Our goal was to collect 100 completed surveys as a convenience sample size, which was achieved in five days.

Figure 1.

PNL Family Survey, given to families of surgical patients at MSKCC.

Implementation

Implementing these changes involved collaboration with several different disciplines. To ensure that all staff members affected by these changes understood their new role, personnel in each perioperative area reviewed the new process and completed orientation regarding the new responsibilities in their roles. The PNLs educated:

the concierge staff to copy the name of the contact person designated by the patient into the record, including any important individualized messages (eg, family needs to wait on the 6th floor, no cell phone, hard of hearing);

the PSC staff on providing the fact card to families upon arrival to the PSC;

perioperative staff members on the PNLs’ role changes; and

the surgeons on our program enhancements, the location and expected use of the new consult rooms, and the expectation that all families present require a face-to-face postoperative consult.

During the implementation phase of this project, the OR RNs also changed their workflow, and began visiting the patient and family in the PSC preoperatively, which provided an opportunity for the OR RNs to establish a relationship with the patient’s family. This practice change improved their communication with the PNLs, because the OR RNs now inform the PNLs who is present in the waiting area for the patient. The OR RNs may also ask the PNL to pass along a message to the patient’s family (eg, “he or she went to sleep okay”). If the PNL was present for the postoperative consult with the surgeon, the PNL may also report to the PACU RN and escort the family to visit the patient in PACU. The PNLs are in constant communication with the entire perioperative team on a daily basis and are available to collaborate regarding anxious families, special needs, delayed or cancelled surgeries, or to de-escalate a difficult situation.

New Process for Collecting Preoperative Information

On arriving at the facility, the patient meets with the concierge and is asked to provide the cell phone number of the family member who the patient designates to receive updates from the PNL. This is copied directly to the electronic chart by the concierge staff. If the patient has a special request (eg, no information to be given without the patient being present, call my wife at home, call my son), it is documented by the concierge and honored by the PNL whenever possible.

When the patient or family consults with a nurse in the PSC preoperatively, the nurse provides a fact card to the family. The fact card includes information related to checking into the PSC, where the family should wait to receive direct information from the PNLs, and PACU visitation. In addition, it provides the PNL’s telephone number, allowing for mutual communication.

Intraoperative Family Contact

The PNLs make rounds in the OR every two hours, which allows them to collect information from the surgical team. The PNLs are then able to speak directly to the patient’s family in the waiting area and provide an update on the procedure. The clinical information provided is ultimately determined by the surgeon, and each family is aware of this. Depending on the length of the surgery or a family’s individual need, the PNLs may call them directly from the OR to give an update. Time spent with each family depends on the PNL’s assessment of the family’s coping style and their expressed anxiety. The PNL may refer a patient or family member to the chaplain, social worker, case manager, nutritionist, or psychiatrist based on each patient’s surgical outcome or assessed family needs. After the PNLs finish making rounds in the waiting area, they call each family member who was either not present in the waiting area during rounds or who requires an update over the telephone.

Standardized Consult

Four private consult rooms at MSKCC are located adjacent to the OR suites and are easily accessible to surgeons. To streamline the process of escorting a family to a consult room, we standardized the perioperative team members’ communications. When the surgeon is ready to speak with the family postoperatively, he or she can either ask the circulating nurse to call the concierge and request that the family return to the perioperative services department (where the consult rooms are located), or call the concierge directly. It is now an expectation that all families receive postoperative findings in a private setting.

When the news is untoward (eg, cancer has spread or the tumor could not be removed) we established a standard that the PNL would be present during the family’s consult with the surgeon. The PNLs met with each surgeon and discussed the situations in which it would be appropriate to include a PNL, such as the following:

intraoperative consent change;

critical event such as an allergic reaction, bleeding, or code;

psychosocial support; or

the procedure could not be performed as scheduled (eg, surgeon was not able to resect the tumor).

If a surgeon does not remember to ask a PNL to be present for an untoward consult, the PNL speaks directly with the surgeon to improve our collaboration, which has been well received.

Role of the PNL during Consult

The PNL is an objective listener during a postoperative consult, and can summarize and clarify information when the surgeon leaves the consult until the family fully understands what was discussed. When possible, the PNL may arrange for the surgeon to accompany the family and the PNL to deliver postoperative findings to the patient in PACU. If the surgeon cannot be present for this visit to the PACU, the PNL supports the family during the first visit. The purpose of the surgeon accompanying the family to the bedside to provide clinical findings to the patient is to relieve the family from the burden of providing news to the patient. This may decrease anxiety for everyone involved. Depending on the surgeon’s availability, however, this is not always possible. In our experience, the patient often asks questions immediately on waking in the PACU, and we support the patient and family during this delivery of surgical findings.

RESULTS

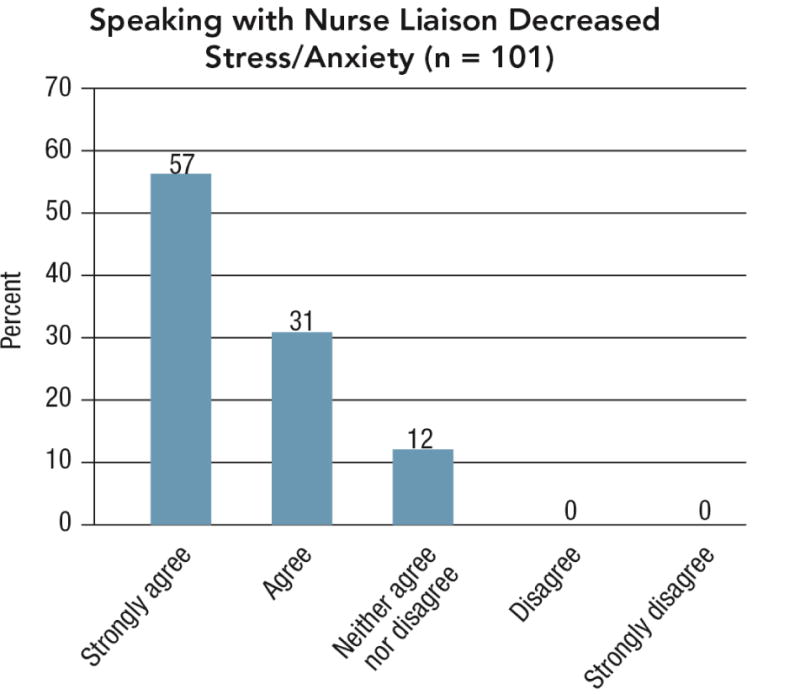

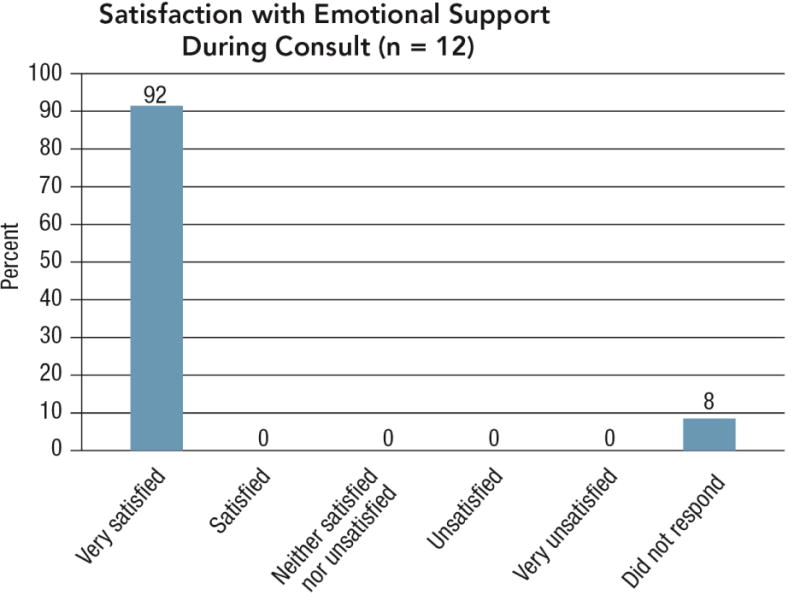

After implementing our new process, collaborative consultations with surgeons increased from 254 per year to an average of 500 per year. Identifying a contact person increased the overall PNL contact with families from 82% to 98%, exceeding our expectation of 95%. Of the 104 families approached for participation in our survey, 102 surveys (98%) were returned. The survey results showed that families were pleased with the PNL’s communication; 96% of respondents found the intraoperative updates either “helpful” or “very helpful” (Figure 2), and 88% agreed or strongly agreed that the PNLs helped decrease stress and anxiety (Figure 3). One respondent found the information given by the PNLs neither “helpful” nor “unhelpful” because of confusion about the length of surgery. Another respondent suggested that the information provided was “old” and could be more timely with the use of a tablet. Most respondents (81%) communicated with the PNLs in person as opposed to on the telephone, and 95% of respondents indicated that the PNLs explained how the individual surgeons would provide updates during the procedure. Twelve respondents reported that they had a postoperative consult with the surgeon and a PNL in attendance, and 11 out of the 12 respondents stated they were very satisfied with the emotional support offered (Figure 4). One participant did not respond to the emotional support question.

Figure 2.

Results from PNL Family Survey measuring helpfulness of information from the PNL.

Figure 3.

Results from PNL Family Survey measuring stress and anxiety level after speaking with PNL.

Figure 4.

Results from PNL Family Survey measuring satisfaction with emotional support given by the PNL.

LIMITATIONS

Although the results of the family surveys were largely positive, there were some limitations to this project. The initial plan was for the PNLs to collaborate with the PACU nurse, who would distribute the survey after the PACU visit. Because of staffing issues, this was not possible. This plan would have facilitated data collection for an extended period of time. Although the sample size of 102 surveys exceeded our initial goal of 100, there were fewer consults including a surgeon and a PNL than expected. Collecting data for a longer time period would have increased the sample size. Another limitation was that families who were not present at the facility received telephone updates only and therefore did not participate in the survey.

CONCLUSION

Research supports that in-person updates given to family members of a loved one undergoing surgery result in a greater reduction in anxiety versus telephone updates. The results of our survey suggest that updates provided during the procedure reduce anxiety, even without an in-person visit from the PNL. Individualizing the plan of care with the patient and family allows the family to choose where they prefer to wait or allows them to return home, to their hotel, or to work. Communication between the contact person and the PNL is mutual and it is important to allow the family to call the PNL as often as needed.

Currently, the standard practice at our facility is for the PNL to support families when untoward news is delivered. This practice has positive outcomes for the family, surgeon, and the PNL. The positive results of our survey indicate that the improved PNL process reduces anxiety for families and improves satisfaction for the waiting families when their loved one was in the OR. Further research is needed to link the role of the PNL in the postoperative consult to both the families’ and surgeons satisfaction. When adopting a liaison program, the PNL must look at innovative ways to communicate real time updates and personalize the surgical experience for the patient and family.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Patricia Agre, RN, EdD, education director; Bridgette Thom, MS, senior research specialist; MaryAnn Regan, MA, RN, per-diem PNL; Marisol Hernandez, MLS, MA, senior reference librarian; Meryl Greenblatt, editor; and Carole Cass, MSN, RN, CNOR, administrative nurse leader of perioperative services, for their assistance in editing this article.

Biographies

Cathy Ann Hanson-Heath, MSN, RN, CNS, OCN, PMHCNS-BC is a perioperative nurse liaison at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY. As funding for this project was provided to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center by a Cancer Center Support Grant/Core Grant (P30 CA008748), Ms Hanson-Heath has declared affiliation that could be perceived as posing a potential conflict of interest in the publication of this article.

Linda M. Muller, MA, RN, AOCNS is a perioperative nurse liaison at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY. As funding for this project was provided to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center by a Cancer Center Support Grant/Core Grant (P30 CA008748), Ms Muller has declared affiliation that could be perceived as posing a potential conflict of interest in the publication of this article.

Maureen F. Cunningham, MSN, RN, OCN was a perioperative nurse liaison at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY. As funding for this project was provided to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center by a Cancer Center Support Grant/Core Grant (P30 CA008748), Ms Cunningham has declared affiliation that could be perceived as posing a potential conflict of interest in the publication of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Cathy Ann Hanson-Heath, Perioperative Nurse Liaison, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, 1275 York Avenue, New York, NY 10065.

Linda M. Muller, Email: mullerl@mskcc.org, Perioperative Nurse Liaison, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, 1275 York Avenue, New York, NY 10065, Contact telephone: 646-208-2571.

Maureen F. Cunningham, Email: cunningm@mskcc.org, Perioperative Nurse Liaison, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, 1275 York Avenue, New York, NY 10065, Contact telephone: 212-639-5935, Perioperative Nurse Liaison Program.

References

- 1.Carmichael JM, Agre P. Preferences in surgical waiting area amenities. AORN J. 2002;75(6):1077–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2092(06)61609-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leske JS. Anxiety of elective surgical patients’ family members: relationship between anxiety levels, family characteristics. AORN J. 1993;57(5):1091–1103. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2092(07)67315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leske JS. Intraoperative progress reports decrease family members’ anxiety. AORN J. 1996;64(3):424–436. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2092(06)63055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The state-trait anxiety inventory (STAI) American Psychological Association. http://www.apa.org/pi/about/publications/caregivers/practice-settings/assessment/tools/trait-state.aspx. Accessed December 15, 2015.

- 5.Stephens-Woods K. The impact of the surgical liaison nurse on patient satisfaction in the perioperative setting. Can Oper Room Nurs J. 2008;26(4):6–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham MF, Hanson-Heath C, Agre P. A perioperative nurse liaison program: CNS interventions for cancer patients and their families. J Nurs Care Qual. 2003;18(1):16–21. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200301000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herd HA, Rieben MA. Establishing the surgical nurse liaison role to improve patient and family communication. AORN J. 2014;99(5):594–599. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2013.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Micheli AJ, Curran-Campbell S, Connor L. The evolution of a surgical liaison program in a children’s hospital. AORN J. 2010;92(2):158–168. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lerman Y, Kara I, Porat N. Nurse liaison: the bridge between the perioperative department and patient accompaniers. AORN J. 2011;94(4):385–392. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stefan KA. The nurse liaison in perioperative services: a family-centered approach. AORN J. 2010;92(2):150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2009.11.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]