Abstract

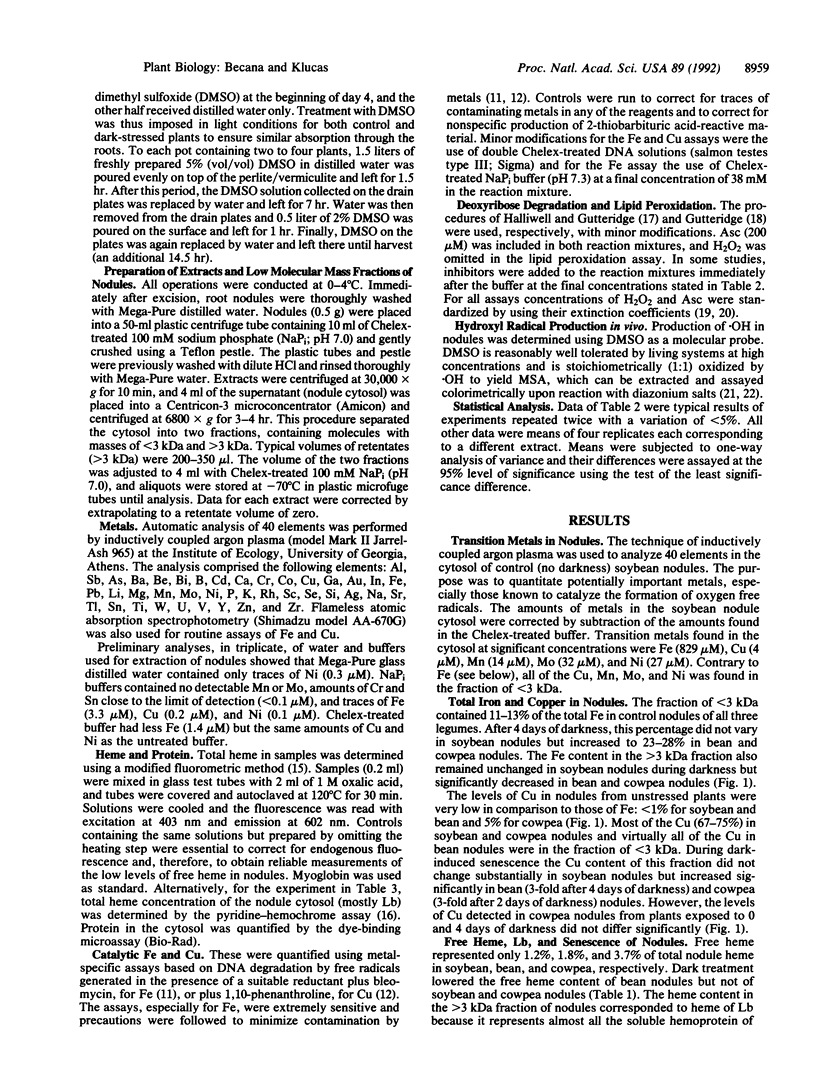

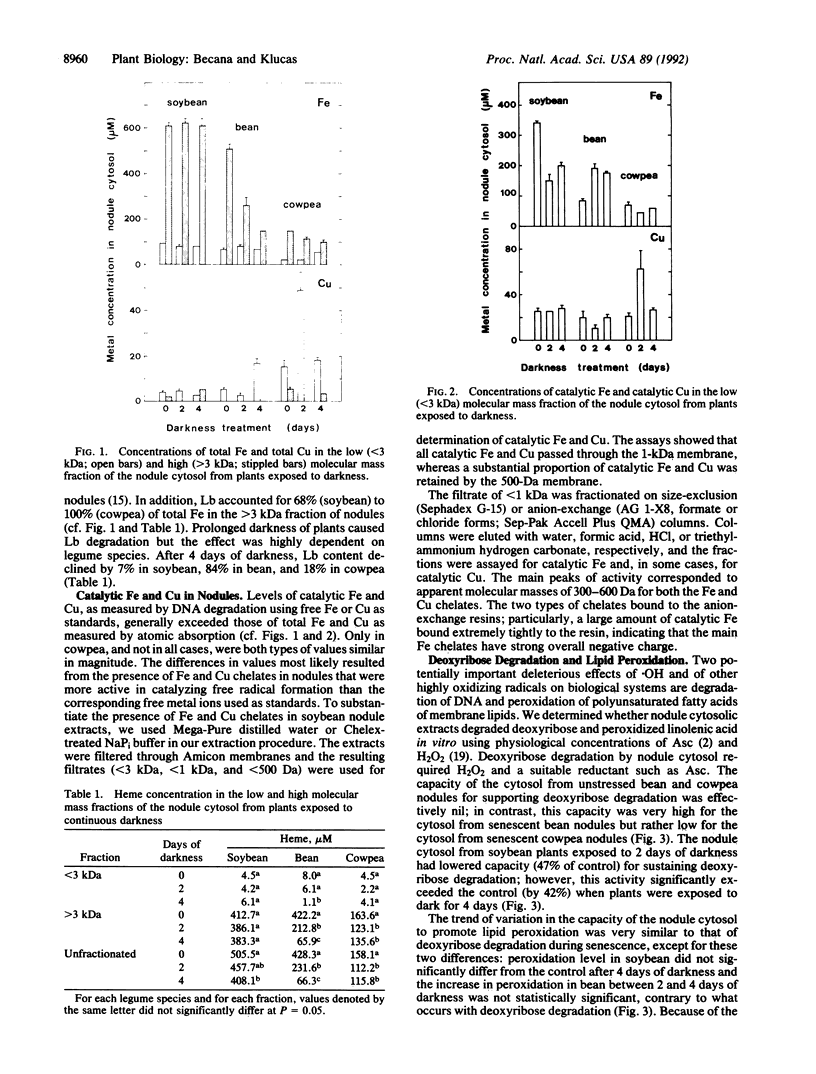

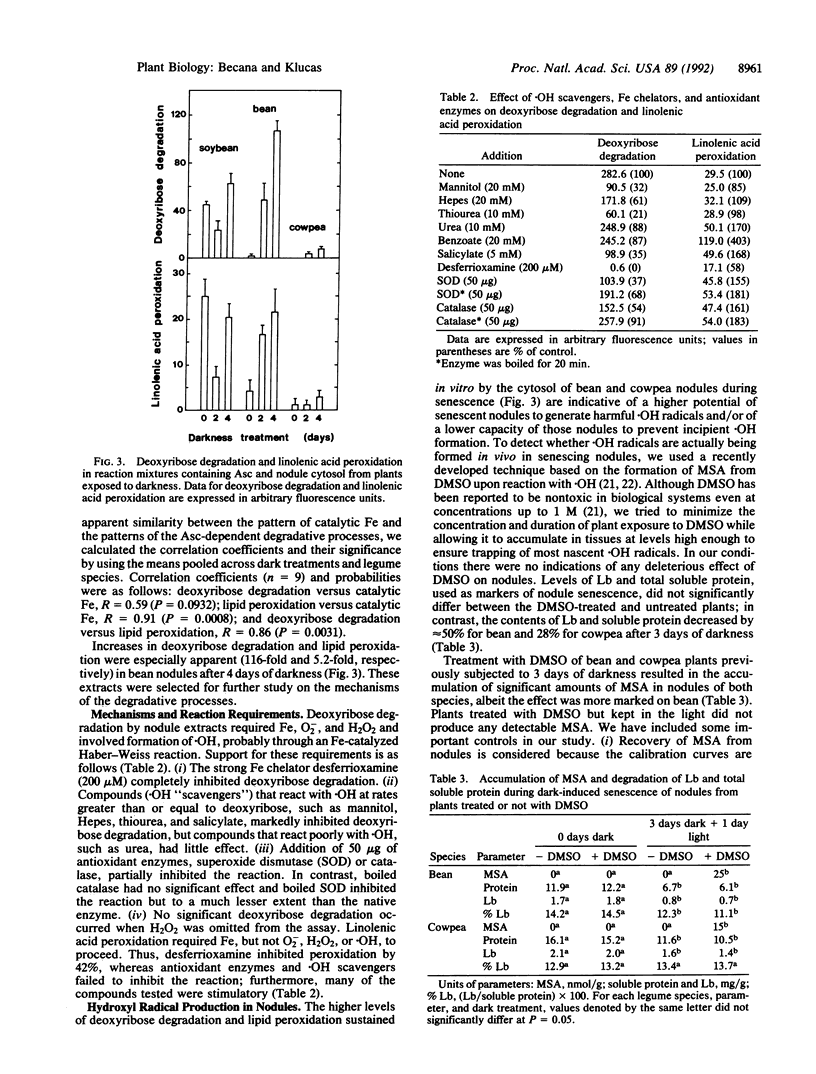

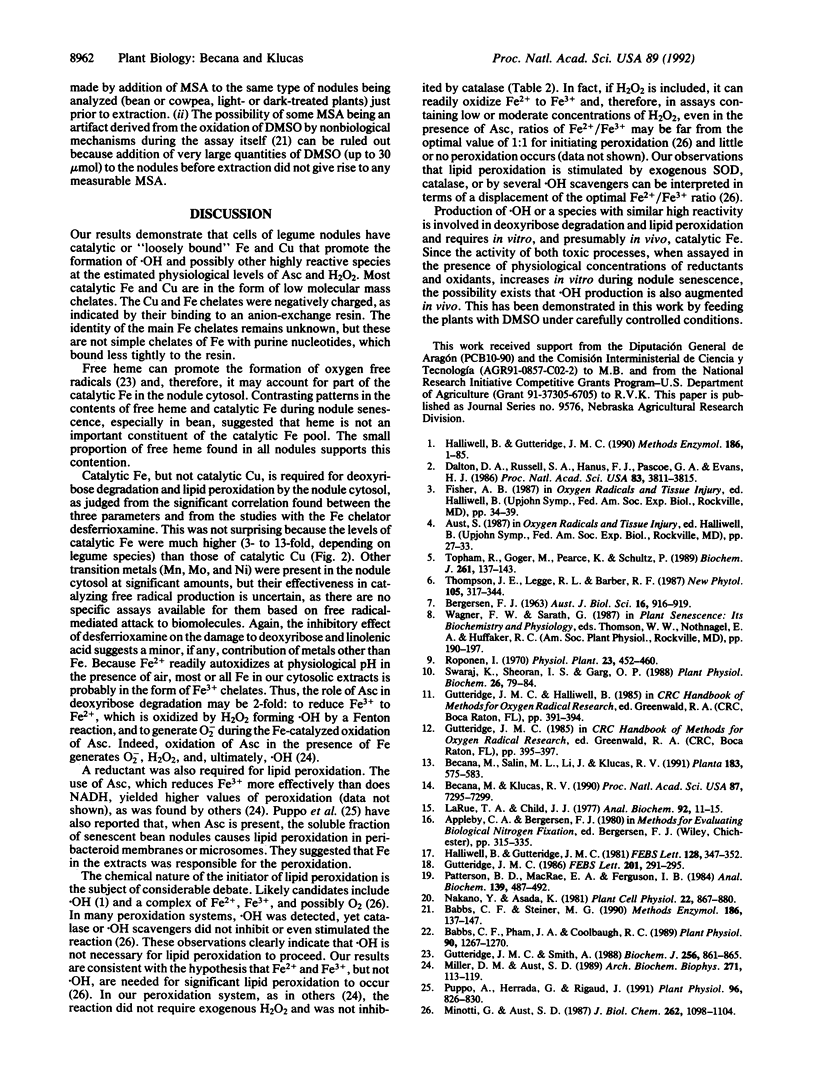

The cytosol from root nodules of soybean, bean, and cowpea contained Fe and Cu capable of catalyzing the formation of highly reactive free radicals. Specific and sensitive assays based on free radical-mediated DNA degradation revealed that most catalytic Fe and Cu were present as small chelates (300-600 Da). The involvement of catalytic Fe in free radical production during nodule senescence, which was induced by exposure of plants to continuous darkness for 2-4 days, was investigated. (i) Free heme remained at a constant and low concentration (1-4% of total nodule heme) during senescence, indicating that it is not an important constituent of the catalytic Fe pool of nodules. (ii) Catalytic Fe of nodule cytosol promoted deoxyribose degradation and linolenic acid peroxidation in reaction mixtures containing physiological concentrations of ascorbate and H2O2. Deoxyribose degradation but not lipid peroxidation required hydroxyl radicals to proceed. (iii) The cytosol from senescent nodules, particularly of bean and cowpea, sustained in vitro higher rates of deoxyribose degradation and lipid peroxidation than the cytosol from unstressed nodules. Both degradative processes were inhibited by the Fe chelator desferrioxamine and were correlated with the content of catalytic Fe in the nodule cytosol. (iv) Although other transition metals (Cu, Mn, Mo, and Ni) were present in significant amounts in the low molecular mass fraction (<3 kDa) of the nodule cytosol, Fe is most likely the only metal involved in free radical generation in vivo. (v) By using dimethyl sulfoxide as a molecular probe, formation of significant amounts of hydroxyl radical was observed in vivo during senescence of bean and cowpea nodules.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Babbs C. F., Pham J. A., Coolbaugh R. C. Lethal hydroxyl radical production in paraquat-treated plants. Plant Physiol. 1989 Aug;90(4):1267–1270. doi: 10.1104/pp.90.4.1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babbs C. F., Steiner M. G. Detection and quantitation of hydroxyl radical using dimethyl sulfoxide as molecular probe. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:137–147. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becana M., Klucas R. V. Enzymatic and nonenzymatic mechanisms for ferric leghemoglobin reduction in legume root nodules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Sep;87(18):7295–7299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.7295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton D. A., Russell S. A., Hanus F. J., Pascoe G. A., Evans H. J. Enzymatic reactions of ascorbate and glutathione that prevent peroxide damage in soybean root nodules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Jun;83(11):3811–3815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.3811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutteridge J. M. Iron promoters of the Fenton reaction and lipid peroxidation can be released from haemoglobin by peroxides. FEBS Lett. 1986 Jun 9;201(2):291–295. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)80626-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutteridge J. M., Smith A. Antioxidant protection by haemopexin of haem-stimulated lipid peroxidation. Biochem J. 1988 Dec 15;256(3):861–865. doi: 10.1042/bj2560861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B., Gutteridge J. M. Formation of thiobarbituric-acid-reactive substance from deoxyribose in the presence of iron salts: the role of superoxide and hydroxyl radicals. FEBS Lett. 1981 Jun 15;128(2):347–352. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(81)80114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B., Gutteridge J. M. Role of free radicals and catalytic metal ions in human disease: an overview. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:1–85. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86093-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRue T. A., Child J. J. Sensitive fluorometric assay for leghemoglobin. Anal Biochem. 1979 Jan 1;92(1):11–15. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90618-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller D. M., Aust S. D. Studies of ascorbate-dependent, iron-catalyzed lipid peroxidation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1989 May 15;271(1):113–119. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(89)90261-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minotti G., Aust S. D. The requirement for iron (III) in the initiation of lipid peroxidation by iron (II) and hydrogen peroxide. J Biol Chem. 1987 Jan 25;262(3):1098–1104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson B. D., MacRae E. A., Ferguson I. B. Estimation of hydrogen peroxide in plant extracts using titanium(IV). Anal Biochem. 1984 Jun;139(2):487–492. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puppo A., Herrada G., Rigaud J. Lipid peroxidation in peribacteroid membranes from French-bean nodules. Plant Physiol. 1991 Jul;96(3):826–830. doi: 10.1104/pp.96.3.826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topham R., Goger M., Pearce K., Schultz P. The mobilization of ferritin iron by liver cytosol. A comparison of xanthine and NADH as reducing substrates. Biochem J. 1989 Jul 1;261(1):137–143. doi: 10.1042/bj2610137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]