Abstract

Pulmonary hypertension remains a major cause of cardiac maternal death in the developed world. Over the last two decades, effective therapies for pulmonary hypertension have been developed, improving symptoms and survival. Consequently, increasing numbers of women with pulmonary hypertension and childbearing potential exist, with a number considering pregnancy. Patients with pulmonary hypertension may also present for the first time during pregnancy or shortly following delivery. The last decade has seen increasing reports of women with pulmonary hypertension surviving pregnancy using a variety of approaches but there is still a significant maternal mortality at between 12% and 33%. Current recommendations counsel that patients with known pulmonary hypertension should be strongly advised to avoid pregnancy with the provision of clear contraceptive advice and termination of pregnancy should be considered in its eventuality. In patients who are fully informed and who have been counselled regarding the risks of continuing with pregnancy, there is growing evidence that a multi-professional approach with expert care in pulmonary hypertension centres may improve outlook, although the mortality remains high.

Keywords: Pulmonary hypertension, pregnancy, chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, maternal mortality

What is pulmonary hypertension?

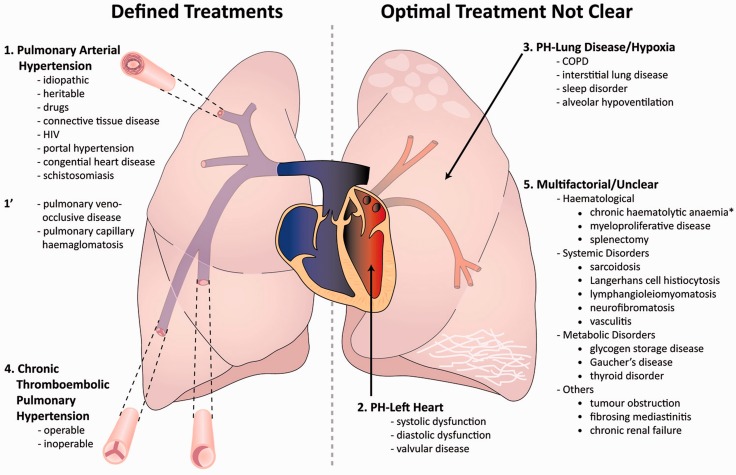

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is defined at cardiac catheterisation as a mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) of at least 25 mmHg. It has many causes and improved understanding of pathophysiology led to an internationally recognized system of classification that has identified five major disease groups: Group 1, pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH); Group 2, PH owing to left heart disease (PH-LHD); Group 3, PH owing to lung disease and or hypoxia; Group 4, chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) and Group 5, unclear or multifactorial aetiologies1 (Figure 1). The cause of PH is key to treatment and patients with suspected PH require detailed investigation to establish a clear cause and this should ideally be conducted in specialist PH centres.2 It should be remembered that severe pulmonary hypertension is extremely rare in women of childbearing age.

Figure 1.

Overview of the classification of pulmonary hypertension reproduced from the BMJ, Kiely et al.2 Patients for whom specific therapies aimed at the pulmonary vasculature are known to improve outcome and are shown on the left hand side; in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH)-specific pharmacological therapies aimed at the pulmonary vasculature improves outcome; in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH), major surgery with pulmonary endarterectomy can be curative and for selected patients pharmacological therapies may improve outcome. For patients on the right hand side of the diagram, there is no current evidence that drug therapies will improve outlook and indeed this may worsen symptoms.

In PAH, progressive narrowing of the pulmonary arterial bed results in increased right ventricular afterload and if untreated, it leads to right heart failure and death within a few years. PAH has several different causes resulting in similar pathological features. The three forms of PAH most commonly encountered include idiopathic PAH (IPAH), previously known as primary pulmonary hypertension for which no cause is identified, PAH in association with connective tissues diseases such as systemic sclerosis (PAH-CTD) or in association with congenital heart disease (PAH-CHD).3 IPAH is rare, with a prevalence estimated between 15 and 52/million3–7 and before the advent of specific PH therapies, the median survival was 2.8 years. This has improved, with women of childbearing age having an approximate 75% chance of being alive at 5 years.7 For PAH, specific drug therapies are available and include oral therapies such as phosphodiesterase inhibitors (sildenafil and tadalafil) and endothelin receptor antagonists (bosentan and ambrisentan). Prostanoid analogues require more complex delivery systems (epoprostenol (intravenous (iv)), iloprost (nebulised (neb), iv) and treprostinil (subcutaneous, neb, iv)) and have antiproliferative effects as well as causing pulmonary arterial vasodilation.2 Some of these drugs are potentially teratogenic and should be avoided in pregnancy.

CTEPH occurs following pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE) in up to 3.8%8 of cases. In addition to obstructing the pulmonary vascular bed with organized clot, changes may also be seen in the rest of the pulmonary circulation, similar to those seen in PAH. This form of PH can be cured by pulmonary endarterectomy, which requires open-heart surgery and a prolonged period on cardiopulmonary bypass. In pregnancy, this form of surgery would be poorly tolerated. The effects on the heart in CTEPH are very similar to PAH. Drug therapies such as those for PAH can be considered in these patients, although the evidence for their use is suboptimal.3,5 Given the lack of alternative options in CTEPH, during pregnancy, they have been used to bridge a patient to delivery and successful pulmonary endarterectomy.9

In contrast to patients with PAH and CTEPH, where treatments aimed at the pulmonary vasculature can improve outcome, in patients with underlying cardiac and respiratory disease, treatment is most appropriately aimed at the underlying cause. In Group 2 PH-LHD, for example, mitral stenosis causes an elevated left atrial pressure and a back pressure, resulting in elevation of pulmonary venous pressure that can elevate mPAP. Although in long-standing and severe mitral stenosis an element of PAH can be seen, the most appropriate intervention is to treat the mitral valve disease. Treatment with drugs that dilate the pulmonary arterioles and increase blood flow into the lungs can precipitate pulmonary oedema due to pulmonary venous hypertension in patients with PH-LHD. This emphasizes the importance of identifying the cause of PH, which is key to management.

Severe respiratory disease capable of causing PH is rarely seen in patients of childbearing age and given the degree of parenchymal disease necessary to cause PH, pregnancy would be poorly tolerated in this group. Cystic fibrosis can cause extensive lung destruction but pulmonary hypertension is rarely seen in this group of patients and confined to those with end-stage disease.

What are the clinical features of pulmonary hypertension and how do I make the diagnosis?

The majority of patients with PH who are pregnant will have an established diagnosis.9 However, this diagnosis should be considered in pregnant patients with increasing breathlessness in the first trimester, particularly if significant and associated with syncope. In the immediate post-partum period, rapid decompensation of patients can occur and occasionally is the first presentation of PH. The classic symptoms of PH include fatigue and progressive exertional breathlessness. As the disease progresses, patients may develop exertional pre-syncope and syncope, which are usually indicators of severe disease. Exertional chest tightness similar to angina may occur but ankle oedema is a late feature. Electrocardiogram (ECG) and chest X-ray (CXR) may be abnormal in up to 90% of cases with severe disease but cannot be used in clinical practice to exclude PH. The diagnosis is usually suggested by echocardiography.2 This allows an estimate of systolic pulmonary artery pressure (sPAP) by adding an estimate of right atrial pressure (usually estimated at 5 mmHg) to the tricuspid gradient, which is equal to 4V2 where “V” is the peak velocity of the jet of tricuspid regurgitation. A jet of tricuspid regurgitation can be seen in approximately 90% of patients and is normal. A sPAP >40 mmHg is considered abnormal but echocardiography can both overestimate and underestimate sPAP. It should also be recognized that PH is defined at right heart catheter as a mPAP of at least 25 mmHg. Other echocardiographic features may also suggest PH such as a dilated right ventricle with reduced function and may identify a cause of PH such as LHD. In patients with IPAH, the sPAP is often in excess of 70 mmHg. The diagnosis may also be suggested by other investigations such as CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) performed for other reasons such as suspected pulmonary embolism. Review of the CT may show evidence of pulmonary artery enlargement and dilated right-sided chambers, which are easily appreciated but often overlooked.2 It is absolutely essential that if a diagnosis of PH is suspected, patients are referred to specialists experienced in the assessment of PH to confirm or refute the diagnosis.

What is the risk of maternal death in a patient with pulmonary hypertension who becomes pregnant?

Current data come from a number of sources including several single centre experiences, systematic analyses of the published literature and recently a small prospective study. Each of these have limitations and have included predominantly PAH and a number of series have concentrated on PAH-CHD. One of the first to publish on this topic was Gleicher et al.10 who identified a maternal mortality of 30% in Eisenmenger syndrome in four decades to 1978. Weiss et al.11 undertook a systematic evaluation of the literature from 1978 to 1996 with the benefit of Medline. In this comprehensive review, a heterogeneous group of 128 patients were studied from various countries. Those who would be classified as IPAH had a mortality of 30%, those with PAH-CHD, 36% and those with various forms of PH associated with other conditions including PAH-CTD but also unusual conditions such as Takayasu’s arteritis, a mortality of 56%. More recently, Bedard et al.12 compared the outcome of PH in pregnancy between 1997 and 2007 with Weiss using similar methodology with a review of more recently published literature. This study confirmed that PH in pregnancy remained uncommon with only 73 parturients in the published literature and mortality in IPAH being 17%, PAH-CHD, 28%, and other forms of PH, 33%. Compared with the previous decades, there had been a modest overall improvement in mortality at 25% versus 38% for all patients.12 A number of single centre studies, including our own, have over the last 20 years suggested that outcomes may be improved when patients receive specialist care with an overall mortality in the region of 10%, although numbers in these studies tend to be small.9,13–15

More recently, a prospective study enrolled 26 pregnancies with PAH from a number of PH specialist centres but there were eight abortions (six induced) and overall mortality of 12%. This group of patients were highly selected, with half the patients being long-term responders to calcium antagonists (these patients represent just 5% of patients with IPAH).16

In conclusion, the risk of maternal death remains very high. In practice, we quote a maternal mortality of approximately 20%. For those with severe PAH and poorly controlled disease, the risk will be significantly higher. Whether a ‘low risk’ group can be identified will only be answered over time but currently we recommend that all patients with PAH avoid pregnancy.

Why is the risk of maternal death so high?

The pre-existence of PAH or CTEPH poses a severe risk of maternal death, due in significant part to an interplay between cardiovascular stresses with complex physiological changes occurring during pregnancy and the compromised right ventricular function and abnormal vasculature seen in these patients.17 Detailed studies in pregnancy are limited in part by the non-invasive assessment of cardiac indices and by the limited number of patients. Recognition of the reasons for a high mortality allows one to identify potential targets for intervention.

Cardiovascular demands

In order to meet the demands of the foetus and mother, there are a variety of cardiovascular changes that occur in pregnancy. Oxygen consumption increases by 30% and blood volume increases by 40–50% by 32–36 weeks’ of gestation.18 Cardiac output increases steadily throughout pregnancy from the first trimester, reaching at peak at around 28 weeks, around 50% higher than pre-pregnancy levels.19–21 This is a challenge for patients with PAH, who have compromised cardiac function due to an increase in right ventricular afterload and a reduced ability to increase cardiac output in response to stress, be it on exercise or during pregnancy. In severe PAH, the resting cardiac output may be low and less than 3.0 l/min. In some patients, the cardiovascular demands of pregnancy cannot be met. This will be reflected by increasing breathlessness or syncope as the patient struggles to meet cardiovascular demands. The development of these symptoms on minimal exercise or at rest early in pregnancy when further increases in cardiac output will be required is an ominous sign.

Direct effects on the pulmonary vasculature

A variety of hormonal changes occur during pregnancy and it is generally accepted that pregnancy is a ‘vasodilatory state’. However, changes and the release of various vasoactive peptides at different stages during pregnancy and in the post-partum period may have adverse effects on the vasculature, intensifying pulmonary vasoconstriction. In particular, during the post-partum period, rapidly changing levels of vasoactive constrictors and vasodilators may result in intense pulmonary vasoconstriction and contribute to the high mortality often seen at this time.

Acute changes in blood volume around delivery and effects on compromised right ventricular function

During labour, painful uterine contractions lead to a further increase in cardiac output. This demand can be reduced using analgesia. The third stage of labour with delivery of the placenta and uterine contraction can release up to 500 ml of blood into the circulation.22 Delivery also results in decompression of the aorta and venous system, with an increase in venous return. These may in part be offset by blood losses during delivery but these changes in blood volume, dependent on effects on the right ventricle, may have adverse effects on blood pressure. Major fluid shifts following delivery can increase right atrial pressure and have significant adverse effects on right ventricular function. A negative Starling response reflecting volume-mediated right ventricular dilation23 can cause a precipitous reduction in cardiac output, which can be life threatening.

Thrombosis

In situ thrombosis is noted in histological specimens from patients with IPAH and failure to clear thrombus is a hallmark of CTEPH. Risk of acute PTE is increased during pregnancy, particularly in the post-partum period in patients undergoing Caesarean section. The development of pulmonary thrombosis results in an increase in afterload, further compromising RV function.

Other factors

The stress of coping with a normal pregnancy is exacerbated in patients and their families by the presence of any medical condition where the risk of maternal death is high. A number of issues may affect compliance, often with complex therapies and management plans. The need for assessments by experienced physicians able to understand subtle changes and a lack of randomised controlled trial data on how to manage these pregnancies contribute to a cocktail that may have disastrous consequences.

Do different factors influence clinical deterioration at different times of pregnancy?

Understanding the timing of important physiological changes in pregnancy and how they may affect a patient with PH as well as an understanding of the unpredictable nature of this illness is key to understanding how to optimise management strategies during various stages of pregnancy and the post-partum period. There are two periods where the risk of maternal death is particularly high: the first two trimesters and delivery/immediate post-partum period.

Early deterioration – inability to cope with cardiovascular demands

Failure to cope with the metabolic demands of pregnancy is more common in patients with severe PH, who have less cardiovascular reserve, although the individual’s response to the increasing requirements of pregnancy can be very variable. With cardiac output increasing during the first two trimesters to reach a plateau, it is not surprising that patients who struggle with increased breathlessness in the first 24–28 weeks identify themselves as a group at high risk. Given the need to increase cardiac output progressively, the earlier the symptomatic deterioration, the more serious the cardiovascular inadequacy. In a single centre series from a large PH centre in France, three patients deteriorated between 12 and 23 weeks, with two of these patients dying and the patient who survived did so following termination of pregnancy.24 In our centre, a patient who deteriorated at 25 weeks required initiation of iv prostanoid therapy and was delivered 5 days later, following optimisation of her clinical state.25

Delivery and post-partum – fluid shifts, pulmonary vasoconstriction and thrombosis

Repeated studies have identified that the immediate post-partum period is the highest risk for patients who successfully complete the first two trimesters. In the systematic review by Weiss et al.,11 36% of patients with Eisenmenger syndrome died, three during pregnancy, 23 within 30 days of delivery, with 14 patients dying within 2 and 7 days post-delivery. In IPAH, eight out of nine deaths occurred within 35 days of delivery, with the majority between 2 and 7 days. For these patients, the majority died of ‘pulmonary hypertensive crisis’ or ‘therapy-resistant heart failure’ and in a small number (n = 3), ‘thrombosis’ was identified, although it is not clear whether this may have been long-standing. Bedard et al.12 in their systematic review of more recent practice identified that the first week post-partum remains the highest risk period. There are a number of factors at play during this period. Major fluid shifts occur and a case report by Easterling et al.23 documented with a central venous catheter the effects of a rising right atrial pressure on cardiac output and how this could be ameliorated by augmenting the physiological diuresis. The effect of withdrawing a hormonal ‘vasodilatory’ influence (which occurs following delivery) on the pulmonary vasculature is not known but one would anticipate that for some patients the pregnancy may have a ‘protective effect on the vasculature’, which is lost in the immediate post-partum period. The procoagulant effect of pregnancy in the third trimester and particularly in the post-partum period may cause obstruction of the vasculature by thrombosis and whether fibrin and platelet deposition in the pulmonary vasculature may result in increasing obliteration of a compromised vasculature is the subject of conjecture.

What advice should I give a patient with pulmonary hypertension regarding pregnancy?

With the high risk of maternal death in pregnancy and the difficulties in identifying low-risk pregnancies, our approach is to provide the patient with a comprehensive list of the evidence but advise strongly against pregnancy. We quote an absolute mortality risk of around 20% but higher in patients who have significant exercise limitation, WHO Class III and evidence of right heart dysfunction. We emphasise the challenge in predicting the natural history of disease, particularly in patients who are well in WHO functional Class (FC) II (mild exercise limitation). We find it helpful to discuss specifically the reason why patients deteriorate, e.g. an inability to pump more blood around the body to meet the requirements of the foetus, and that it is often later in pregnancy and post-delivery that patients run into problems. It is important also to point out that it is a major undertaking requiring a lot of hospital visits and delivery is more likely to entail surgical intervention with Caesarean section and a stay in an intensive care unit. It is important that patients are aware that they may become very unwell and despite all medical efforts they may die.

What forms of contraception can be used in patients with pulmonary hypertension?

It is essential that contraception is effective in this patient population and that the individual needs of each patient are discussed.26 Progesterone-only contraceptives such as cerazette (oral daily), nexplanon (implant) and depot-provera (every 3 months) are safe and effective if taken as prescribed and reduce the pro-thrombotic effects of the combined oral contraceptive pill. Nexplanon has the advantage that the individual does not need to remember daily medication or 3-monthly injections. These drugs can be taken in patients prescribed warfarin although care needs to be taken with intramuscular injections. Due to problems with reliability, the progesterone-only mini pill is not recommended. The Mirena intra-uterine system is highly effective and helpful in women with heavy periods. The risk of vaso-vagal events, which can be dangerous in PH, mandates that these devices be inserted in a hospital environment. Periodic abstinence and condoms are not recommended as a sole form of contraception, although the latter has an important role in preventing sexually transmitted diseases. Female sterilization is generally not recommended as it requires an anaesthetic and is less effective than other forms of contraception, although for appropriately counselled patients, it can be performed at the time of Caesarean section. Importantly the endothelin receptor blocker bosentan (but not ambrisentan) is an enzyme inducer so that for patients taking cerazette or nexplanon, we recommend an additional tablet of cerazette. Emergency hormonal contraception is safe for unprotected intercourse but a double dose is required in patients taking bosentan.

What should I do if a patient with pulmonary hypertension tells me she is planning to become pregnant?

It is important to recognize that despite counselling some patients may plan actively to become pregnant. It is essential that physicians experienced in the management of PH and ideally of PH and pregnancy are involved in these discussions. We often find it helpful that the woman and her partner meet with pulmonary hypertension physicians, obstetricians, anaesthetists and paediatricians to discuss the challenge ahead.9 It is important these patients are aware that warfarin (that is routinely used in IPAH and CTEPH) is associated with congenital abnormalities and should be stopped if pregnancy is confirmed. They should be informed that bosentan is teratogenic in animals and along with ambrisentan usual advice is to stop this drug prior to trying to conceive. There is little evidence regarding the safety of other medications for PH in pregnancy. Although only a small minority of patients will continue to plan pregnancy following the above, it is key that these patients are supported and are discouraged from simply taking matters into their own hands. We also emphasise for patients recently diagnosed that they ensure there has been a period of stability before embarking on this course. We do discuss also that if the woman survives pregnancy, we cannot confirm that this will not alter the natural history of their disease although currently there are no definitive data to suggest that pregnancy affects the long-term prognosis adversely.

How should I investigate a patient with pulmonary hypertension who presents pregnant?

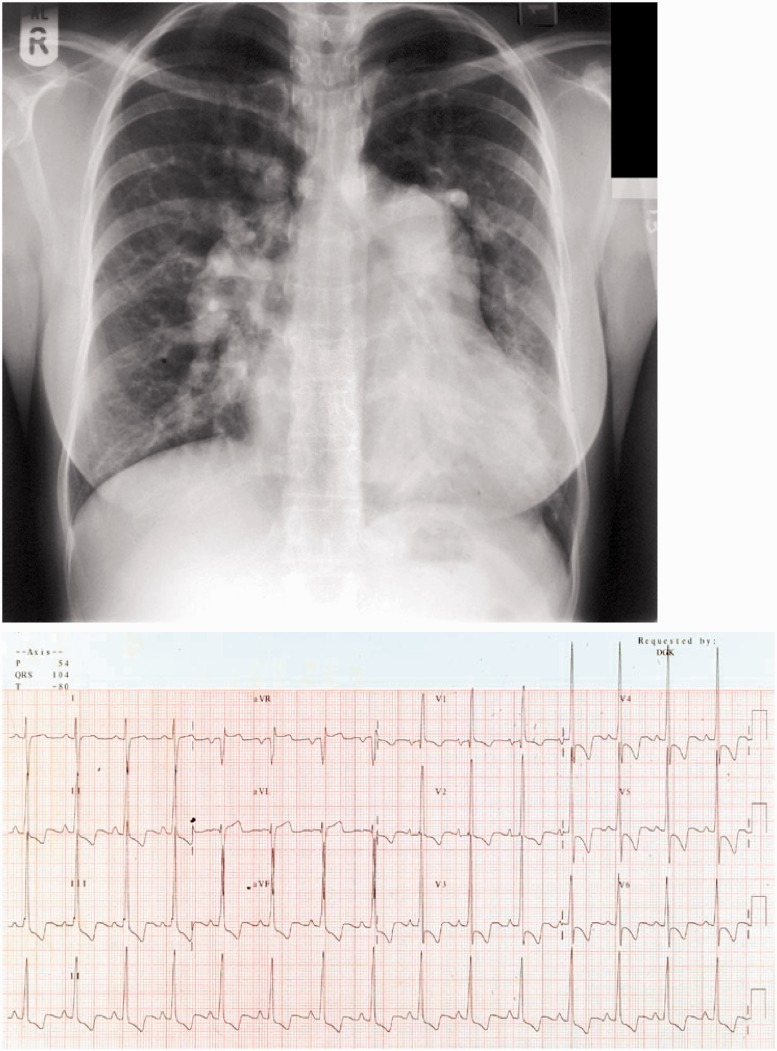

PH is a highly heterogeneous condition and a patient presenting for the first time out-with pregnancy with suspected PH will undergo a battery of non-invasive and invasive tests including extensive blood testing, ECG, CXR (Figure 2), lung function testing, exercise testing, echocardiography, perfusion lung scanning, HRCT and CTPA, MR imaging and right heart catheterisation with vasodilator testing.2 In a patient with known PH with a clear diagnosis, non-invasive assessment to assess disease severity including ECG, exercise testing and echocardiography is usually all that is required. In patients presenting for the first time in pregnancy often during the second and third trimester with clear evidence of severe disease on clinical assessment, echocardiography and cross-sectional imaging with CTPA (Figure 3), right heart catheterisation is usually deferred until after delivery. Invasive assessment of pulmonary haemodynamics during pregnancy is performed where indicated, particularly if there is doubt regarding the severity of disease in critically unstable patients to guide therapy or timing of delivery but these indications are few.9 Facilities for emergency Caesarean section must be available at the time of right heart catheter in the unlikely event of complications.

Figure 2.

Example of a chest X-ray (CXR) and electrocardiogram from a patient presenting with severe pulmonary arterial hypertension at our unit who was successfully delivered at 34 weeks. The CXR shows cardiomegaly with enlargement of the proximal pulmonary arteries. The electrocardiogram shows classic changes of severe pulmonary arterial hypertension with right axis deviation, dominance of the “R” wave in V1 and widespread ST depression/T wave inversion in the inferior and anterior leads.

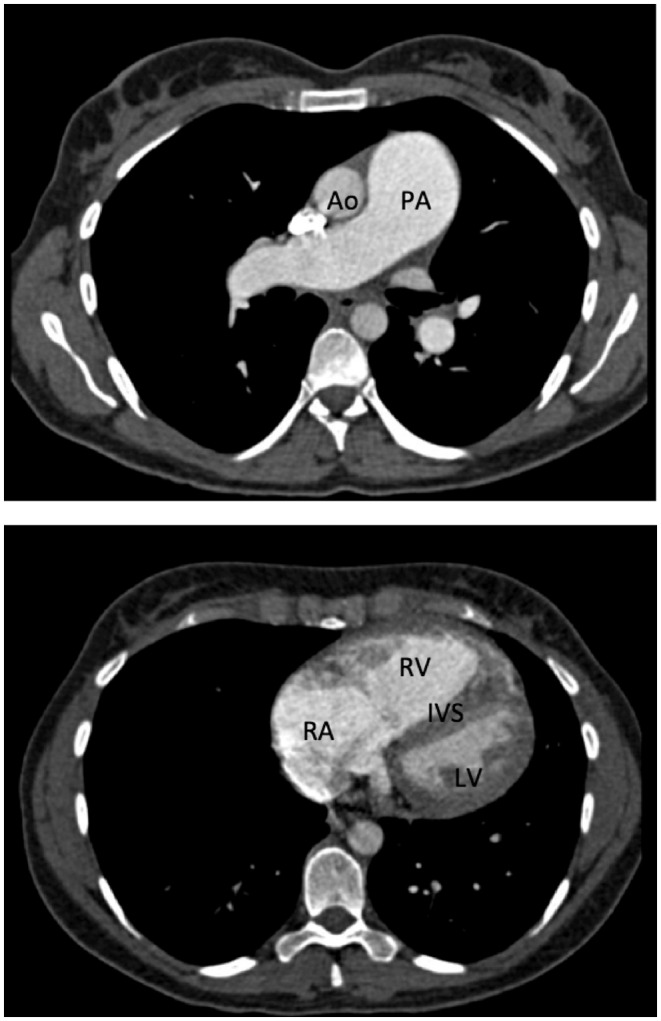

Figure 3.

Example of a CT pulmonary angiogram from a patient with severe pulmonary arterial hypertension. Enlargement of the pulmonary artery (PA) compared to a normal size aorta (Ao) and dilation of the right atrium (RA) and right ventricle (RV) with posterior displacement of the inter-ventricular septum (IVS) and compression of the left ventricle (LV) can be seen.

How should I manage a patient with pulmonary hypertension who is pregnant?

In a patient with known PH, it is key that a diagnosis of pregnancy and the viability of the foetus is confirmed as soon as possible and the patient is seen in the pulmonary hypertension clinic. The patient and her partner need to be fully counselled regarding the risks of continuing with or terminating their pregnancy and this will require that they meet members of a multi-professional team including obstetricians, anaesthetists and their pulmonary vascular physicians. It is important to establish whether the patient wishes to continue with their pregnancy and whether they would consider termination. This is often a very difficult and emotional time for the patient and their family and it is key that they are supported during these difficult discussions. For patients who wish to continue with pregnancy, it is important that warfarin is stopped and replaced with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) and if the patient is taking potentially teratogenic drugs such as bosentan or ambrisentan that these are discontinued and other options considered.

How should I treat pulmonary hypertension during pregnancy?

There is currently no evidence from randomised controlled trials regarding the effectiveness of therapies directed at the pulmonary vasculature in pregnancy and there is no prospect of these trials being conducted. Indeed, many of the drugs used to treat PAH are either contra-indicated (ambrisentan and bosentan) or a caution (prostanoid or phosphodiesterase inhibitors). Prior to the advent of these specific therapies for PAH, the mode of death, particularly in the post-partum period, was ‘pulmonary hypertensive crisis’ or ‘heart failure’.11 Given the ability of these drugs to improve pulmonary haemodynamics and right heart function in patients out-with pregnancy and the awful prognosis of patients with severe PAH who became pregnant in the pre-treatment era even in expert hands, with mortality at over 30%, there is a good rationale to consider using these drugs in pregnancy. A number of reports in the literature in the late 1990s2,3 and subsequently using neb9,25,27 and iv prostanoids23,28 and more recently describing oral therapies15 report successful outcomes, although there are cases where maternal death occurred even with intensive therapy. The systematic review from Bedard et al.12 suggested that in 1997–2007, treatment with PH-specific therapies (including NO in the intensive therapy unit (ITU) environment) did not predict outcome although these were often used late when the patient was critically unwell and would not usually be considered as treatment with targeted therapies. Clearly there is a balance between the potential benefits of these therapies and the risks to the foetus and the timing of introduction of therapies will impact on the latter.

Our approach is to offer all patients with PAH and CTEPH targeted PH therapies where the diagnosis has been made and the patient has received counselling regarding the unlicensed nature of these products.9 We feel it advantageous to commence therapy while the patient is stable to allow the pharmacological effects of the drug to be evaluated and also in the hope that by optimising treatment of PAH, we may improve cardiac reserve and make the pulmonary vasculature less reactive to changes in circulating vasoactive peptides that are likely to occur around the time of delivery. Where the patient is currently receiving PH therapies, we continue with current therapy unless they are receiving an endothelin receptor antagonist. If they are on monotherapy with an endothelin receptor antagonist, we will switch to a phosphodiesterase inhibitor or if a combination of a phosphodiesterase inhibitor and endothelin receptor antagonist, we will switch to a phosphodiesterase inhibitor and neb iloprost. In the event of deterioration on oral monotherapy, we will add neb iloprost with a view to switching to iv prostanoid and planning early delivery if no significant improvement. Deterioration during the first two trimesters mandates early delivery once the patient is stabilised, unless there is an immediate and rapid response to escalation of pharmacological treatment. For patients with a new diagnosis and not on drug therapy, we would introduce PH therapies with neb iloprost with subsequent treatment with oral sildenafil if in WHO FC III. If in WHO FC II, we would observe closely and introduce therapy during the second trimester if the situation remains stable or add before if deteriorates to WHO III to minimize adverse effects on the foetus. A number of other groups have suggested a good outcome with iv prostanoid.28 For stable patients, our approach has been to avoid more complex therapies due to potential risks but to use this approach in patients where there is any deterioration not responding to phosphodiesterase inhibition and neb iloprost. For a small minority of patients with IPAH on high dose calcium antagonists who are clinically stable in WHO FC II, we would continue with these therapies as the outlook appears to be good from a recent multi-centre prospective observational study, although the number of patients on this therapy was small (n = 8).16

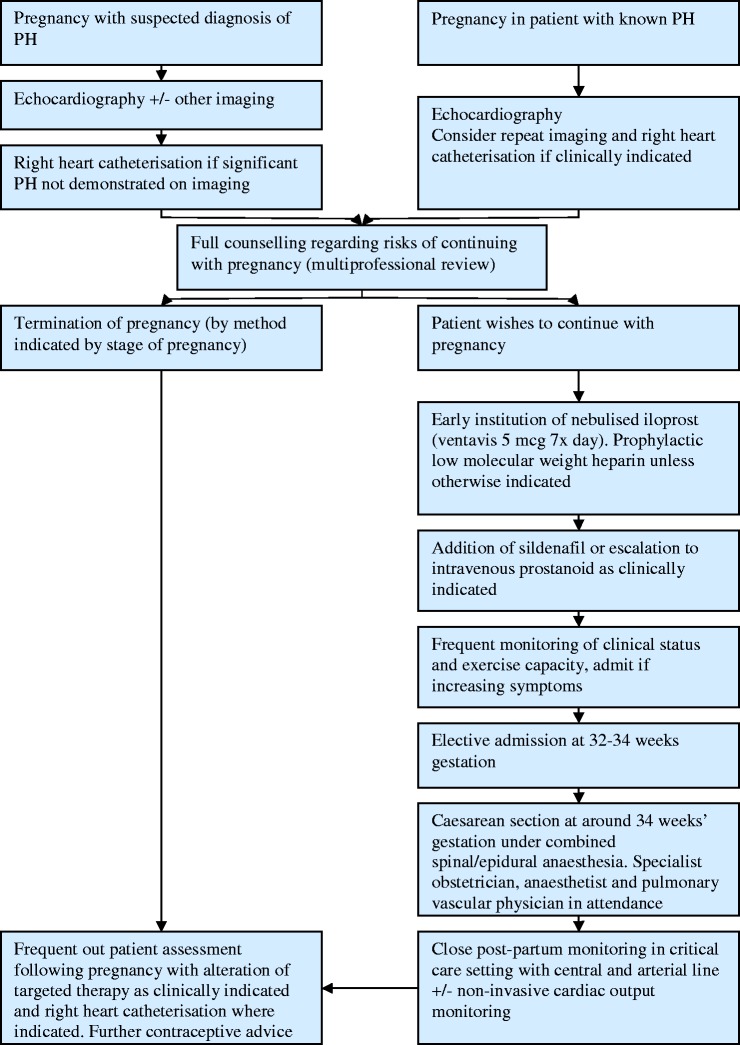

How should I assess and follow-up a pregnant patient with PH during pregnancy?

This depends on the patient, the severity of their disease, their progress, geographical location and experience of their local physicians. In general, after establishing the diagnosis and initial management plan from the PH perspective, we would usually see patients every 4 weeks until 28 weeks, then every 2 weeks until delivery, usually between 34 and 36 weeks. At these visits, we would perform detailed history and examination, ECG, exercise testing with incremental shuttle walking test or 6-minute walk test and echocardiography at selected visits. Our emphasis is particularly on subjective reporting of symptoms with admission for further assessment/monitoring if there is a suggestion of decline. We would advise local obstetric follow-up with obstetric review at our PH center9 at selected visits during the course of the pregnancy to ensure foetal maturation and to exclude obstetric issues such as placenta praevia. If the patient is stable, we would usually admit 24–48 h before delivery. An overview of our approach to the management of a patient with PH who is pregnant is shown in Figure 4.9

Figure 4.

Overview of the management plan for patients with pulmonary hypertension presenting with suspected pulmonary hypertension at the authors’ institution published in BJOG.9

It is important not to neglect the patients general obstetric care and there can sometimes be uncertainty between centres regarding who provides all the standard care during pregnancy. At our PH centre, we now recognize that it is important for pregnant patients and their partners to have the opportunity to meet with the midwifery team. We have found that a visit to the obstetric unit to discuss what the mother should expect and what the infant will require after delivery, a visit to the special care baby unit and a visit to the ITU/high dependency unit (HDU) where the patient will stay for a week or so following delivery is helpful and re-assuring for our patients and partners. The optimal time to do this is not clear but usually within 2 or so weeks of planned delivery strikes a balance between information overload and ensuring that patients get this opportunity before going pre-maturely into labour. Using this approach, we are usually able to manage patients out with the hospital environment, which patients find advantageous.

When should I deliver a patient with pulmonary hypertension who is pregnant?

This is primarily dependent on the health of the mother and also the health of the foetus. As discussed previously, deterioration in the first two trimesters is associated with a poor outcome and these patients require termination/delivery to save the life of the mother24 once the patient has been stabilized and excepting a dramatic improvement on pharmacological treatment. If the patient remains stable during pregnancy, a judgment needs to be made regarding the optimal time for delivery, balancing the needs of the mother and the foetus. The mortality of a mild pre-term delivery is low although there is evidence that there may be a delay in cognitive and behavioural development in infants delivered at 32–35 weeks gestation compared with term.29,30 In addition, early delivery is associated with more neonatal problems necessitating a period for the infant in a special care unit. Balanced against these risks is the chance of a patient going into premature labour at a site distant from the specialist centre, where the personnel and monitoring facilities may not be optimal. Our approach is to deliver at around 34 weeks if the patient is stable although there may be justification for delivering later during the pregnancy. This will be influenced by the mother’s previous obstetric history, progress in the current pregnancy, foetal growth, geographical issues and the wishes of the patient and their families.

What mode of delivery and what form of anaesthesia should I use?

Vaginal delivery versus Caesarean section

An elective procedure allows all members of an extended multi-professional team to be present at a time when circumstances are optimal and there is access to intensive care beds for mother and neonate. In our centre, a pulmonary vascular physician, two obstetric anaesthetists, two experienced obstetricians, a paediatrician, an intensivist, a midwife in addition to other members of the theatre team are all present. Various approaches to delivery (vaginal31 versus Caesarean9) and anaesthesia (general15 versus regional9) have been advocated. Given the compromised right ventricular function and inability to increase cardiac output on exercise, an approach to minimize the impact of delivery on the cardiovascular system would seem appropriate. Vaginal delivery is advocated by some but this is accompanied by a 34% increase in cardiac output when the cervix is fully dilated.22 This can be ameliorated but not abolished by the use of regional anaesthesia. Pushing in the second stage of pregnancy can significantly reduce cardiac output by reducing venous return to the right ventricle, which could have deleterious consequences. Given the trend towards pre-term delivery, induction of pregnancy could result in a long labour and the prospect of an emergency Caesarean section in this setting would be a significant undertaking. For this reason, many centres, including ours, advocate elective delivery using Caesarean section. This allows experienced surgeons to perform the procedure, minimizing blood loss and allowing manoeuvres to avoid use of vasoactive drugs by use of bimanual compression and suture compression of the uterus as appropriate.31 In women with previous successful vaginal delivery/ies, the chance of successful induction of labour increases and the balance of risks (considering the increased risks of bleeding, infection and thrombosis with Caesarean delivery) may allow consideration of spontaneous delivery (geography allowing) or inducing labour. Our usual practice, however, is to plan for elective Caesarean section.

Regional versus general anaesthesia

A number of centres including our own have reported on the use of regional anaesthesia in these patients.9,24 Single shot spinal should be avoided, given the high risk of developing significant hypotension, which could be potentially catastrophic in the setting of a failing right ventricle. Epidural anaesthesia and combined spinal-epidural anaesthesia are usually advocated, with the latter providing the advantages of a low spinal block with a denser sensory block than an epidural, but avoiding the risk of hypotension with a spinal. Regional anaesthesia also has the advantage of providing post-operative analgesia and importantly for patients with, for example bleeding complications, capacity for top up anaesthesia and ease of return to theatre. This is important as surgical complications should be remedied immediately and failure to return to theatre due to concerns regarding need for further general anaesthesia in borderline cases may be an issue. General anaesthesia has also been used successfully by a number of centres;15,24,32 however, rises in pulmonary artery pressure are known to occur at tracheal intubation33,34 and positive pressure ventilation can have negative effects on venous return. Our approach is to use regional anaesthesia but recognize that plans need to be made to proceed to general anaesthesia in selected cases.

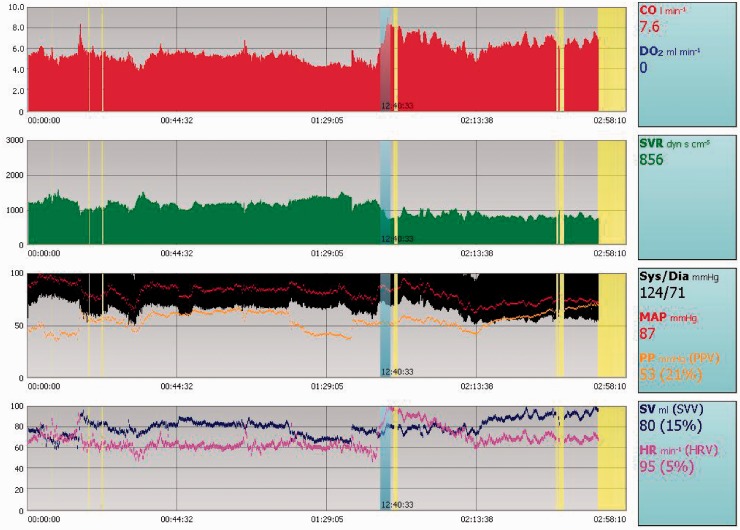

How should I monitor patients around the time of delivery?

Our approach is to admit patients between 24 and 48 h prior to delivery.9,29 This allows for a detailed assessment of the patients clinical status pre-operatively and bloods are taken for full blood count, biochemistry and cross-matching. ECG and echocardiography are performed and we ensure that steroids have been given for foetal lung maturation. The morning of delivery, patients are taken to the intensive care unit early for insertion of a four-port central venous catheter to allow measurement of central venous pressure, drug delivery, sampling for routine bloods and measurement of venous oxygen saturations. An arterial line is inserted to allow continuous blood pressure monitoring. Central venous access is established and in selected patients, a sheath is inserted to allow insertion of a ‘Swan Ganz’ catheter, should the patient deteriorate in the post-partum period, although in practice, we rarely use a pulmonary artery floatation catheter. Non-invasive measures of cardiac output with for example lithium dilution cardiac output35 (Figure 5), which requires central venous and arterial access, allow a continuous measure of cardiac output in addition to other core variables such as mean arterial pressure, right atrial pressure, heart rate and systemic vascular resistance and are useful for assessing trends, particularly in the immediate post-operative period. Our routine for patients on non-parenteral prostanoid (the majority of our patients are now on oral sildenafil and neb iloprost) is to start a low-dose infusion of systemic prostanoid, e.g. 2 mcg/h of iv iloprost for 2 h prior to Caesarean section and to continue this for 48–72 hours post delivery. Women are managed appropriately from a fluid balance perspective aiming for systemic blood pressure and central venous pressures around pre-delivery levels for the first 24 h. We aim to keep Hb >9, ideally 10 g/dl. A rising central venous pressure should raise the possibility of fluid overload, which can be managed by diuretics. Failure to respond to this suggests that the right ventricle may be struggling and in this setting, we would usually increase the dose of iv prostanoid and consider the addition of low-dose dobutamine, e.g. 2 mcg/kg/min and titrating as appropriate. If patients deteriorate despite increasing doses of pulmonary vasodilators and inotropes with the development of systemic hypotension, then we would consider addition of iv noradrenaline while considering causes for deterioration such as sepsis, haemorrhage, thrombosis and worsening PH. During the post-operative period, it is important to maintain adequate oxygenation usually aiming SaO2 94–98% although this may not be appropriate in certain cases.

Figure 5.

Example of a continuous tracing available from LiDCO from a patient with severe pulmonary arterial hypertension taken at the time of delivery. This can be used to monitor patients around delivery and in post-partum period. This allows measurement of cardiac output, which is a key parameter in the peri-partum period.

LiDCO: lithium dilution cardiac output.

Are there any drugs I should use cautiously in patients with pulmonary hypertension?

Anticoagulation is routinely prescribed out with pregnancy in patients with IPAH and CTEPH but not usually in Eisenmenger syndrome due to concerns regarding significant haemoptysis from enlarged bronchial arteries. In pregnancy, the risks and benefits are discussed with individual patients. Our approach is to give prophylactic doses of LMWH in IPAH, full dose twice daily LMWH in CTEPH with prophylactic doses of LMWH given the night before surgery and the night after. Decisions in PAH-CHD are made on an individual basis.

Oxytocic drugs can cause hypotension and tachycardia11,36 but reduce the risk of post-partum haemorrhage. We give them routinely but as a low-dose infusion of syntocinon at 5 units over 1 h, repeated as necessary. If the patient develops hypotension, the infusion is interrupted. Anecdotally, those patients who develop hypotension with this drug often have more compromised right ventricular function.

As in standard anaesthetic practice in patients with cardiac disease, it is always best to give small doses of drugs and observe the effect.

Is breast feeding recommended?

There are no data on drugs used to treat PH and whether they cross into the breast milk. Due to uncertainty regarding this and the effects on a neonate, we advise against this.

How should I follow-up a patient following delivery?

Patients are usually monitored in an ITU/HDU setting for 5–7 days and if stable, discharged shortly thereafter. Following discharge, stable patients are reviewed usually at 1 week, then fortnightly, then monthly, then 3 monthly. Blood volume returns rapidly to normal but it usually takes several weeks for major haemodynamic changes to return to normal and up to 6 months for subtle haemodynamic changes. For patients with a new diagnosis, we would usually perform right heart catheterisation at around 4 months following delivery and rationalize treatment as appropriate at this stage.

Why are detailed management plans important?

Individual management plans are crucial for this patient group. Not all patients will comply with what the multi-professional team feels is the most appropriate approach. These patients can deteriorate rapidly and strategies must be in place to cover all eventualities including medical and obstetric emergencies. This should include patient-specific plans for premature onset of labour, elective Caesarean section, emergency Caesarean section for maternal or foetal indications and what to do at times of cardiac arrest. Protocols outlining the drugs to be used for regional or general anaesthesia and contact details of pulmonary vascular physicians, anaesthetists, intensivists, obstetricians and haematologists are essential. Copies of these plans are also given to the patient in case of acute onset of problems outside the unit.

Conclusion

Patients with pulmonary hypertension should be advised of the high risks of pregnancy with clear and comprehensive contraceptive advice and if needed be offered termination of pregnancy. Despite being fully counselled regarding the high risk, patients may actively plan to become pregnant or may present for the first time in pregnancy with a new diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. The advent of new therapies for specific forms of pulmonary hypertension, improvements in obstetric care and a multi-professional approach to the management has improved survival and outcome. Despite these advances, patients may have difficulties adhering to management plans and despite optimal strategies, pregnancy may ultimately result in the death of both the mother and unborn child. The potential impact that this has on family members and staff should not be underestimated.

References

- 1. Simonneau G, Robbins IM, Beghetti M, et al. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 54: S43–S54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kiely DG, Elliot CA, Sabroe I, et al. Pulmonary hypertension: diagnosis and management. BMJ 2013; 16, 346:f2028 DOI: 10.1136/bmj.f2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hurdman J, Condliffe R, Elliot CA, et al. ASPIRE registry: Assessing the Spectrum of Pulmonary hypertension Identified at a REferral centre. Eur Respir J 2012; 39: 945–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peacock AJ, Murphy NF, McMurray JJ, et al. An epidemiological study of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2007; 30: 104–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Condliffe R, Kiely DG, Gibbs JS, et al. Improved outcomes in medically and surgically treated chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008; 177: 1122–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Humbert M, Sitbon O, Chaouat A, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in France: results from a national registry. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 173: 1023–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ling Y, Johnson MK, Kiely DG, et al. Changing demographics, epidemiology, and survival of incident pulmonary arterial hypertension: results from the pulmonary hypertension registry of the United Kingdom and Ireland. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012; 186: 790–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pengo V, Lensing AW, Prins MH, et al. Incidence of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 2257–2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kiely DG, Condliffe R, Webster V, et al. Improved survival in pregnancy and pulmonary hypertension using a multiprofessional approach. BJOG 2010; 117: 565–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gleicher N, Midwall J, Hochberger D, et al. Eisenmenger's syndrome and pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1979; 34(10): 721–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weiss BM, Zemp L, Seifert B, et al. Outcome of pulmonary vascular disease in pregnancy: a systematic overview from 1978 through 1996. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998; 31(7): 1650–1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bédard E, Dimopoulos K, Gatzoulis MA. Has there been any progress made on pregnancy outcomes among women with pulmonary arterial hypertension? Eur Heart J 2009; 30: 256–65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13. Presbitero P, Somerville J, Stone S, et al. Pregnancy in cyanotic congenital heart disease. Outcome of mother and fetus. Circulation 1994; 89(6): 2673–2676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Presbitero P, Rabajoli F, Somerville J. Pregnancy in patients with congenital heart disease. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1995; 125(7): 311–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Curry RA, Fletcher C, Gelson E, et al. Pulmonary hypertension and pregnancy–a review of 12 pregnancies in nine women. BJOG 2012; 119(6): 752–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jaïs X, Olsson KM, Barbera JA, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in pulmonary arterial hypertension in the modern management era. Eur Respir J 2012; 40(4): 881–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kiely DG, Elliot CA, Webster VJ, et al. Pregnancy and pulmonary hypertension: new approaches to the management of a life threatening condition. In: Steer PJ, Gatzoulis MA, Baker P. (eds). Heart disease and pregnancy, London: RCOG Press, 2006, pp. 211–229. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weiss BM, Hess OM. Pulmonary vascular disease and pregnancy: current controversies, management strategies, and perspectives. Eur Heart J 2000; 21(2): 104–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bonica JJ. Maternal anatomic and physiologic alterations during pregnancy and parturition. In: Bonica JJ, McDonald JS. (eds). Practice of obstetric analgesia and anesthesia, 2nd ed Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1995, pp. 45–82. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Poppas A, Shroff SG, Korcarz CE, et al. Serial assessment of the cardiovascular system in normal pregnancy. Role of arterial compliance and pulsatile arterial load. Circulation 1997; 95(10): 2407–2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van Oppen AC, Stigter RH, Bruinse HW. Cardiac output in normal pregnancy: a critical review. Obstet Gynecol 1996; 87(2): 310–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hunter S, Robson SC. Adaptation of the maternal heart in pregnancy. Br Heart J 1992; 68(6): 540–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Easterling TR, Ralph DD, Schmucker BC. Pulmonary hypertension in pregnancy: treatment with pulmonary vasodilators. Obstet Gynecol 1999; 93(4): 494–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bonnin M, Mercier FJ, Sitbon O, et al. Severe pulmonary hypertension during pregnancy: mode of delivery and anesthetic management of 15 consecutive cases. Anesthesiology 2005; 102(6): 1133–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Elliot CA, Stewart P, Webster VJ, et al. The use of iloprost in early pregnancy in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2005; 26(1): 168–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thorne S, Nelson-Piercy C, MacGregor A, et al. Pregnancy and contraception in heart disease and pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2006; 32: 75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Weiss BM, Maggiorini M, Jenni R, et al. Pregnant patient with primary pulmonary hypertension: inhaled pulmonary vasodilators and epidural anesthesia for cesarean delivery. Anesthesiology 2000; 92(4): 1191–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bendayan D, Hod M, Oron G, et al. Pregnancy outcome in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertensionreceiving prostacyclin therapy. Obstet Gynecol 2005; 106: 1206–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kramer MS, Demissie K, Yang H, et al. The contribution of mild and moderate preterm birth to infant mortality. J Am Med Assoc 2000; 284: 843–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Huddy CL, Johnson A, Hope PL. Educational and behavioural problems in babies of 32–35 weeks gestation. Arch Dis Child 2001; 85: 23–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Smedstad KG, Cramb R, Morison DH. Pulmonary hypertension and pregnancy: a series of eight cases. Can J Anaesth 1994; 41(6): 502–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. O'Hare R, McLoughlin C, Milligan K, et al. Anaesthesia for caesarean section in the presence of severe primary pulmonary hypertension. Br J Anaesth 1998; 81(5): 790–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jonas MM, Tanser SJ. Lithium dilution measurement of cardiac output and arterial pulse waveform analysis: an indicator dilution calibrated beat-by-beat system for continuous estimation of cardiac output. Curr Opin Crit Care 2002; 8(3): 257–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Blaise G, Langleben D, Hubert B. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: pathophysiology and anesthetic approach. Anesthesiology 2003; 99(6): 1415–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Weeks SK, Smith JB. Obstetric anaesthesia in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Can J Anaesth 1991; 38(7): 814–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pinder AJ, Dresner M, Calow C, et al. Haemodynamic changes caused by oxytocin during caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia. Int J Obstet Anesth 2002; 11(3): 156–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]