Abstract

The role of the complement system in immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) is not well defined. We examined plasma from 79 patients with ITP, 50 healthy volunteers, and 25 patients with non-immune mediated thrombocytopenia, to investigate their complement activation/fixation capacity (CAC) on immobilized heterologous platelets. Enhanced CAC was found in 46 plasma samples (59%) from patients with ITP, but no samples from patients with non-immune mediated thrombocytopenia. Plasma from healthy volunteers was used for comparison. In patients with ITP, an enhanced plasma CAC was associated with a decreased circulating absolute immature platelet fraction (A-IPF) (<15 × 109/L) (p = 0.027) and thrombocytopenia (platelet count less than 100K/μl) (p= 0.024). The positive predictive value of an enhanced CAC for a low A-IPF was 93%, with a specificity of 77%. The specificity and positive predictive values increased to 100% when plasma CAC was defined strictly by enhanced C1q and/or C4d deposition on test platelets. Although no statistically significant correlation emerged between CAC and response to different pharmacologic therapies, an enhanced response to splenectomy was noted (p <0.063). Thus, complement fixation may contribute to the thrombocytopenia of ITP by enhancing clearance of opsonized platelets from the circulation, and/or directly damaging platelets and megakaryocytes.

Introduction

Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) is an autoimmune disorder which manifests clinically as mucocutaneous bleeding in the setting of a low platelet count (Cines et al., 2009). The prevalence of ITP in the United States has been estimated to be as high as 13 per 100,000 persons (George et al., 1995). Individuals with ITP lasting longer than twelve months are described as having chronic disease (Rodeghiero et al., 2009). Chronic ITP in both children and adults is largely manageable with treatments including (i) immunomodulators such as corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulins, and rituximab, (ii) immune suppression, (iii) splenectomy, and, more recently, (iv) thrombopoietic agents. ITP treatments often acutely raise the platelet count, but patients frequently relapse and require retreatment. The response time is dependent on the specific treatment used and the patient’s response to it.

Platelet destruction in ITP occurs by a variety of different immune mediated mechanisms (Cines et al., 2009). Various humoral and cell mediated mechanisms have been described, but the role of the complement system has not been well defined (McMillan, 2000; He et al., 1994; Semple et al., 1996; Kuwana et al., 2001). Limited studies of plasma complement deficiencies in patients with ITP (Kurata et al., 1987; Lurhuma et al., 1977; Trend et al., 1980; Ohali et al., 2005) and elevated levels of platelet associated complement, particularly C3 (Foster et al., 1989; Kayser et al., 1983; Panzer et al., 1986), have been reported. The observed association between platelet associated IgG/IgM and C3 suggests the potential for classical complement pathway activation on the platelet surface (Kayser et al., 1983; Panzer et al., 1986).

Thus, the present study investigated the complement activating capacity (CAC) of plasma from patients with ITP, using a recently developed in vitro assay (Peerschke et al., 2006) that measures complement activation on immobilized, fixed heterologous platelets, as a surrogate for patient platelets. This approach provides several advantages over direct examination of complement deposition on circulating platelets, particularly in patients with ITP. Firstly, the assay is unaffected by the degree of thrombocytopenia, and preferential loss/clearance of platelets that may be opsonized or damaged/lysed by complement. Secondly, the assay can be performed on frozen/stored patient plasma samples. Thirdly, the ELISA format is simple to perform and reproducible.

Previous studies reported on the intrinsic capacity of platelets, stimulated by soluble agonists or by adhesion/immobilization, to activate both classical (Peerschke et al, 2006; Hamad et al., 2008) and alternative (Del Conde et al., 2005) pathways of complement. The CAC assay measures this activity and any additional contribution from plasma or serum that influences complement activation at or near the test platelet surface, including total complement levels and the presence of immunoglobulins capable of reacting with platelets. For example, compared to serum from healthy volunteers, enhanced complement component deposition was observed on test platelets in a retrospective study of serum from patients with antiphospholipid syndrome with and without a concomitant diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (Peerschke et al., 2009). The increased CAC correlated with the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies. Moreover, in patients with SLE, an increased CAC was associated with platelet activation and an increased incidence of arterial thrombosis.

We, therefore, hypothesized that anti platelet antibodies in patients with ITP would enhance complement activation on test platelets. In vivo, this may contribute to the multi-factorial pathogenesis of thrombocytopenia in ITP. For example, in addition to Fc-receptor mediated clearance of platelets opsonized with immunoglobulin by the reticuloendothelial system, complement activation occurring on circulating platelets, depending on the immunoglobulin class and subclass of platelet associated antibodies, would contribute to platelet clearance via complement receptors on macrophages in the spleen. Furthermore, complement mediated cytolysis may contribute to peripheral platelet destruction (Venneker and Aghar, 1992; Ruiz-Delgado et al., 2009), and damage megakaryocytes, thereby decreasing platelet production. The importance of the complement system in the pathogenesis of ITP is of interest, particularly in light of recently developed therapies that inhibit activation of complement components C5 (eculizumab) (Parker, 2009) and C3 (compstatin) (Ricklin and Lambris, 2008).

Methods

Subjects

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects of the Weill Medical College of Cornell University and The Mount Sinai School of Medicine. Blood was drawn after obtaining oral informed consent from patients with ITP (n=79) seen at the Platelet Disorders Center of the Weill Medical College of Cornell University, and from apparently healthy volunteers (n=50). Study patients consisted of both adult and pediatric patients with ITP who were undergoing various treatment regimens. As defined by an International Working Group reporting on the standardization of terminology in ITP (Rodeghiero et al., 2009), all patients included in the analysis were considered to have chronic ITP, defined as ITP lasting for greater than 12 months.

Blood samples from control patients with nonimmune mediated thrombocytopenia (n=25) were retrieved from the Clinical Coagulation Laboratory at The Mount Sinai Hospital, after all diagnostic testing had been completed. Samples were selected based on platelet count and clinical diagnosis.

CBC Analysis

Blood was collected into K3 EDTA using standard vacutainer tubes (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). CBC analysis was performed using the Advia 120 (Siemens/Bayer, Tarrytown, NY). A new automated method to quantify reticulated platelets, expressed as the immature platelet fraction (IPF) was performed using the XE-2100 cell counter (Sysmex, Kobe Japan) (Briggs et al., 2004). The IPF is identified by flow cytometry techniques and the use of a nucleic acid specific dye in the reticulocyte/optical platelet channel.

Plasma Complement Activation Capacity (CAC)

A solid phase assay was used to measure plasma complement activating capacity (CAC) on immobilized heterologous platelets. Details of the assay have been reported previously (Peerschke et al., 2006; Peerschke et al., 2009). A brief description of key aspects of the test procedure follows.

Preparation of Platelet Coated Reaction Wells

Blood from apparently healthy volunteers was collected into 3.2% sodium citrate (9:1 blood: anticoagulant ratio). Platelet rich plasma was prepared by centrifugation at 280 g for 8 min. Platelets were washed by centrifugation (1000g, 15 min) in the presence of 10 mM ethylenediaminetetra acetic acid (EDTA) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The resulting platelet pellet was resuspended in 0.01 M HEPES (N-2 hydroxyethyl piperazine ethane sulfonic acid)-buffered modified Tyrode’s solution (HBMT) containing 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2 and 2 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (fatty acid free; Sigma-Aldrich). No specific measures were taken to inhibit platelet activation during washing and immobilization procedures. Washed platelets were immobilized on microtiter plate wells using poly-L lysine (Sigma-Aldrich). Adherent platelets were fixed with 0.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.01 M phosphate buffered 0.14 M NaCl (PBS), pH 7.5. Microtiter wells were blocked with glycine-1% BSA and washed with HBMT. Platelet-coated microtiter wells were frozen at −70°C until use. Immobilized platelets were exposed (60 min, 37°C) to plasma from patients with ITP (n=79), patients with nonimmune mediated thrombocytopenia (n=25), or plasma from healthy volunteers (n=50), as described below.

Plasma Preparation

Platelet-poor plasma was obtained from peripheral blood that was anticoagulated with 0.32% sodium citrate after centrifugation (1000 × g, 20 min). Plasma was frozen (−80 ° C) in 1-mL aliquots until use. A retrospective analysis was performed using banked specimens from patients and healthy volunteers. For complement fixation assays, all plasma samples were diluted (1/10) in HBMT containing 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2. Because thrombin generation may indirectly enhance complement activation (Huber-Lang et al., 2006), complement fixation was assayed in the presence of a direct thrombin inhibitor, 50 μM D-phenylalanyl-L-prolyl-L arginine chloromethyl ketone (PPACK) (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA).

Complement fixation on platelet-coated reaction wells

The deposition of complement components C1q, C4d, C3b, and C5b-9 was quantified using commercially available monoclonal antibodies recognizing C1q, C4d, iC3b, and neoC5b-9 (Quidel Corp., Santa Clara, CA; final concentration of 10 μg/ml). Primary antibody binding was detected with an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody F(ab’)2 fragment and para-nitrophenyl phosphate (p-NPP) substrate, both from Sigma-Aldrich. Substrate conversion was measured spectrophotometrically at 405 nm. Non-immune mouse IgG1κ (MOPC21, Sigma-Aldrich; 10 μg/ml) served as a negative control antibody. Assay reactivity noted in the presence of non-immune mouse IgG was subtracted from all experimental results. Immobilized platelets were screened for background reactivity by incubation with HBMT instead of plasma.

Result Interpretation

Assay results (ELISA optical density readings) were normalized to an internal assay standard and expressed as a ratio to facilitate inter-assay comparison. The assay standard represented a reference plasma pool that was prepared with plasma from 25 healthy donors, and was stored in aliquots at −70°C. The calculated ratio was designated plasma complement activating capacity (CAC). A ratio greater than 1.0 represented enhanced complement activating capacity in the test system.

As described previously, stimulated or adherent platelets express an intrinsic capacity to activate both classical (Peerschke et al., 2006; Hamad et al., 2008) and alternative (Del Conde et al., 2005) pathways of complement. Complement fixation in the test system, measured following incubation of immobilized platelets with the standard reference plasma pool, reflects this intrinsic platelet activity, and was considered baseline. Amplification of complement activation by C5b-9 generation in the test system and direct C5b-9 mediated platelet stimulation (Wiedmer et al., 1986) was prevented by using fixed platelets. EDTA, an inhibitor of classical and alternative pathways of complement, prevents the association of activated complement components with platelets, except C1q, demonstrating that the assay measures de novo complement activation at or near the immobilized platelet surface.

CAC reference ranges were established using plasma samples from 50 healthy volunteers. Volunteers ranged in age from 25–67 years. Equal numbers of male and female volunteers were represented. In patients with ITP, complement activation initiated by antiplatelet antibodies generating immune complexes on the test platelets are expected to raise the CAC above baseline.

CAC measured in the assay is a function not only of the extent of complement activation at or near the test platelet surface, but also the total complement level present in plasma. In vivo complement activation may lead to consumption of complement components and a commensurate reduction in plasma levels. This is expected to decreased CAC measured in the assay relative to normal plasma, and may contribute to false negative results.

Platelet Associated Immunoglobulin

Selected plasma from patients with ITP exhibiting normal (n=15) or enhanced CAC (n=15) was evaluated for deposition of IgG and/or IgM antibodies, after incubation with immobilized test platelets. Experimental conditions were identical to those used for plasma CAC evaluation. Reaction wells were incubated (60 min, 37°C) with anti human IgG, or IgM antibodies conjugated with horse radish peroxidase (Reaads Medical Products, Inc., Westminster,) CO. Bound horse radish peroxidase-conjugated antibody was detected using tetramethylbenzidine substrate (Reaads Medical Products, Inc.). The reaction was quantified spectrophotometrically (450 nm).

Statistical Analysis

Ordinal data sets were compared using the t-test. Nominal data (positive/negative) were analyzed using the two tailed Fisher exact test. P values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Patient Description

Patients with ITP ranged in age from 5 years to 75 years. The average patient age was 51.2 years. The gender distribution was 59.5% female and 40.5% male. Patients were undergoing treatment with a variety of therapeutic regimens including steroids, intravenous immune globulin (IVIG), Anti-D, Rituximab, splenectomy, Thrombopoietin, Danazol, Vincristine, Azothioprine, GMA161, Rigel, and anti CD40L.

Patients with nonimmune thrombocytopenia ranged in age from 18 years to 80 years, with a gender distribution of 50% male, and 50% female. Clinical diagnoses included a variety of hematologic neoplasms, and administration of chemotherapy for solid tumours. Platelet counts ranged from 9000 – 92,000/μl.

Plasma Complement Activating Capacity (CAC)

Plasma CAC reference intervals were determined for deposition of C1q (1.0 ± 0.30), C4d (1.1 ± 0.45), C3b (0.9 ± 0.35), and C5b-9 (1.0 ± 0.27) on immobilized test platelets incubated with plasma from healthy volunteers (n=50). Based on these ranges, patient plasma was designated CAC positive, if the calculated CAC for one or more of the measured complement components was equal to or greater than 1.9. This cut-off represents a level of complement deposition that falls approximately 3 standard deviations above the reference mean for the majority of complement components. Conversely, plasma samples were classified as CAC negative, if the calculated CAC was below 1.9.

None of the plasma samples from patients with nonimmune thrombocytopenia demonstrated a positive CAC. However, a CAC equal to or exceeding a ratio of 1.9 was exhibited by 58% (n=46/79) of plasma samples from patients with ITP. Evidence for enhanced classical complement pathway activation (C1q and/or C4d deposition) in the test system was noted in 22% of plasma samples (n=17/79). Of these, 8 samples exhibited positive CAC only for C1q, and 4 samples demonstrated positive CAC only for C4d. A positive CAC demonstrating enhanced assembly of the terminal complement complex (C5b-9) on test platelets was exhibited by 35 plasma samples (44%) from ITP patients, and 29 of these were positive only for C5b-9. Five patient plasma samples demonstrated a positive CAC for more than one complement component. Two samples exhibited a positive CAC for the combination of C3b and either C1q or C4d. No plasma samples demonstrated a positive CAC exclusively for C3b.

Curiously, increased deposition of all complement components, C1q through C5b-9, were not simultaneously detected on test platelets. The reason for this observation is not clear, but may represent a test artifact reflecting monoclonal antibody specificity for particular epitopes on complement components that may be obscured or modified during complement assembly and activation. Whereas naturally occurring platelet membrane associated complement regulatory proteins formation (Yin et al., 2008) likely mitigate complement activation and C5b-9 complex (Ruiz-Delgado et al., 2009), this is unlikely to have affected assay results since patient and normal plasmas were assayed on the same fixed immobilized platelets.

Table 1 compares the CAC generated on immobilized test platelets by normal and patient plasma. The CAC of plasma from patients with nonimmune thrombocytopenia was similar to that produced by plasma from healthy volunteers. However, plasma from patients with ITP could be segregated based on the generation of increased CAC in the test system. Among CAC positive plasma samples from patients with ITP, the highest CAC was noted for C1q and C4d.

Table I.

Comparison of the plasma complement activation capacity (CAC) on immobilized test platelets in patients with ITP, nonimmune-mediated thrombocytopenia and healthy volunteers.

| Complement Component | Healthy volunteer (n=50) |

Non immune thrombocytopenia (n=30) |

ITP CAC positive | ITP CAC negative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1q | 1·0 ± 0·3 | 0·8 ± 0·2 | 3·0 ± 1·0 (n = 12) | 1·0 ± 0·5 (n = 67) |

| C4d | 1·1 ± 0·5 | 0·7 ± 0·4 | 2·6 ± 0·6 (n = 7) | 1·3 ± 0·4 (n = 72) |

| C3b | 0·9 ± 0·4 | 0·8 ± 0·4 | 1·9, 1·9 (n = 2) | 1·2 ± 0·3 (n = 77) |

| C5b-9 | 1·0 ± 0·3 | 0·9 ± 0·3 | 2·0 ± 0·1 (n = 34) | 1·3 ± 0·4 (n = 45) |

CAC represents complement component deposition on immobilized test platelets expressed as a ratio relative to an internal assay reference plasma standard. Stratification of ITP patients as CAC positive and negative used a cut-off ratio of ≥1·9.

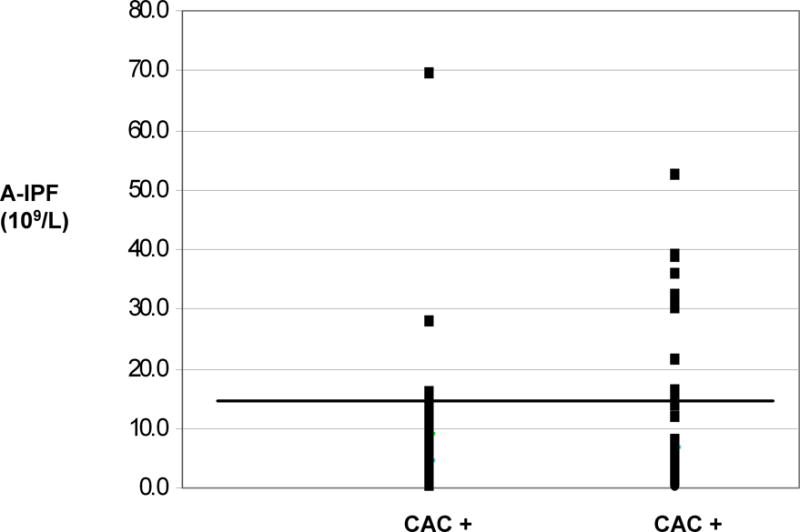

As shown in Figure 1 A, patients with ITP and a positive plasma CAC for any of the measured complement components exhibited a lower peripheral blood absolute immature platelet fraction (A-IPF) (7.6 ± 10.6 × 109/L; median 4.9 × 109/L) than patients with a negative CAC (A-IPF 12.8 ± 0.4; median 5.7 × 109/L) (p=0.06). The A-IPF is generally regarded as a measure of platelet production (Tamaki et al., 2007; Ault et al., 1992; Rinder et al., 1993; Richards and Baglin, 1995). Compared to published reference ranges for A-IPF in healthy individuals (4.5 ± 1.9 × 109/L, range 1.4 – 10.4 × 109/L) (Ault et al., 1992), the A-IPF for patients with ITP in the present study ranged widely from 0.3 to 69.5 × 109/L (9.8 ± 12.4 × 109/L, mean ± standard deviation), suggesting the inclusion of patients with decreased and increased platelet production.

Figure 1.

Relationship between peripheral blood A-IPF and plasma complement activation capacity (CAC) in patients with ITP. Panel A shows A-IPF values for individual patients with either positive(+) or negative (−)plasma CAC. Each data point represents a single patient. The horizontal line reflects an A-IPF cut-off of 15 × 109/L.

When an A-IPF cut off indicative of ineffective platelet production in the setting of thrombocytopenia, was set at <10 × 109/L, consistent with the upper limit of the reference range reported in healthy individuals (Ault et al., 1992), the association with overall plasma CAC positivity or with increased C1q/C4d deposition on immobilized platelets in the test system approached statistical significance (0.05<p<0.1). When the A-IPF cut-off was raised to < 15 × 109/L, the association between plasma CAC and a low A-IPF was statistically significant (Table 2). Moreover, a positive plasma CAC was highly predictive of a low A-IPF, particularly when C1q and/or C4d deposition were considered (Table 2).

Table II.

Relationship between enhanced plasma complement activation capacity (CAC) on immobilized test platelets and peripheral blood A-IPF < 15 × 109/L

| CAC | N | Correlation (Fisher exact test) | Sensitivity (%) |

Specificity (%) |

Positive predictive value (%) | Negative predictive value (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any C Positive | 46 | P = 0·006 | 65 | 77 | 93 | 30 |

| C1q and C4d Positive | 17 | P = 0·031 | 39 | 100 | 100 | 21 |

| C5b-9 Positive | 34 | P=0·098 | 47 | 77 | 91 | 22 |

A positive CAC represents complement activation with attendant C1q, C4d, C3b and/or C5b-9 deposition on immobilized test platelets equal to or exceeding a cut-off ratio of 1·9 relative to an internal assay reference plasma standard.

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between plasma CAC and the number of patients with selected degrees of thrombocytopenia in the ITP patient cohort. A larger number of patients with platelet counts below 50,000/μl (Figure 2A) or below 100,000/μl (Figure 2B) demonstrated a positive as compared to a negative plasma CAC test result. The results were statistically significant.

Figure 2.

Relationship between plasma complement activation capacity (CAC) and ITP patients with thrombocytopenia (n=79). A positive CAC was defined as a complement fixation ratio for C1q, C4d, C3b, and/or C5b-9 ≥ 1.9, relative to an internal assay reference plasma standard.

No statistically significant association emerged between a positive plasma CAC and response of patients with ITP to various therapeutic regimens (data not shown). However, an enhanced response rate to splenectomy was noted in patients with a positive plasma CAC test result: 44% of patients (n=4/9) with a positive plasma CAC result responded to splenectomy, as compared to only14% of patients (n=5/36) with a negative CAC. This difference in response rates approached statistical significance (p= 0.063).

DISCUSSION

Chronic ITP is an autoimmune disease characterized by low platelet count and variable degrees of mucocutaneous bleeding (Cines et al., 2009). The pathophysiology is characterized by immune mediated platelet destruction and decreased platelet production (George et al., 1995; Rodeghiero et al., 2009; McMillan, 2000; He et al., 1994; Semple et al., 1996). In the majority of cases, IgG or IgM anti platelet antibodies can be demonstrated. Since IgG containing immune complexes can activate complement, it is expected that complement activation on the platelet surface should accompany ITP.

However, not all antibodies activate complement with similar potency. Thus, complement activation may vary in patients with ITP and contribute to disease pathogenesis, severity, and response to therapy. In the present study, an in vitro assay was used to compare the complement activating activity (CAC) of plasma from healthy volunteers, patients with ITP, and patients with non-immune mediated thrombocytopenia. Complement was activated on fixed, immobilized, heterologous platelets, in the test system.

Previous studies characterized the intrinsic capacity of platelets to activate both classical (Peerschke et al., 2006) and alternative (Del Conde et al., 2005) pathways of complement. This intrinsic complement activation does not require the presence of anti platelet antibodies or immune complexes, and is mediated in part by the expression of gC1qR (Peerschke et al., 2006) and P-selectin (Del Conde et al, 2005) on activated platelets and secretion of chondroitin sulfate (Hamad et al., 2008). In the present study, this level of complement activation was considered baseline. In normal individuals, this baseline level of platelet directed complement activation is thought to participate in the clearance of spent/apoptotic platelets and microparticles (Yin et al., 2008) from the circulation, inflammatory reactions that contribute to vascular injury and thrombosis, and enhanced platelet activation with expression of prothrombotic activity as a direct result of C5b-9 deposition (Shattil et al., 1992; Wiedmer et al., 1986).

Increased complement activation on test platelets, significantly exceeding this baseline (CAC ≥ 1.9), was generated by plasma from 58% of patients with ITP, but none of the plasmas from patients with non-immune mediated thrombocytopenia. This suggests the presence of additional triggers of complement activation in patient plasma. The observation that plasma from patients with nonimmune mediated thrombocytopenia did not generate enhanced CAC on immobilized platelets in the assay, implicates anti platelet antibodies in the plasma of patients with ITP as a contributing factor. Anti platelet antibodies in patient plasma can bind to platelets in the test system and increase classical complement activation above baseline. Indeed, the observed enhanced deposition of C1q and C4d on immobilized test platelets following incubation with plasma from patients with ITP is consistent with classical complement pathway activation. Moreover, all observed increases in C3b deposition on immobilized platelets incubated with plasma from ITP patients were accompanied by enhanced C1q and/or C4d deposition, suggesting that patient plasma did not directly activate the alternative complement pathway on test platelets.

However, no elevation in IgG deposition was detected on test platelets incubated with plasma from ITP patients, compared to the reference plasma standard (IgG deposition ratio: 0.8 ± 0.25). This may be due to the plasma dilution (1/10) performed for consistency with the CAC assay, and is consistent with the observation that quantification of platelet associated IgG has been disappointing as a clinical laboratory diagnostic test to detect platelet autoantibodies (Beardsley and Ertem, 1998). Alternatively or in addition, failure to detect elevated levels of platelet associated IgG in the current test study may reflect the use of immobilized platelets that were stored frozen (−70°C), and thawed prior to use in the CAC assay. Freezing and thawing exposes intracellular alpha granule platelet IgG, making it difficult to detect small increases in IgG, resulting from test platelet exposure to plasma from ITP patients, over this large internal background.

The present study demonstrates that in patients with ITP, a positive plasma CAC is associated with a low immature platelet fraction, a measure of platelet production (Takami et al., 2007; Ault et al., 1992; Rinder et al., 1993; Richards and Baglin, 1995), and also with thrombocytopenia. These findings suggest that, in vivo, enhanced complement fixation is likely associated with decreased platelet survival due to enhanced clearance of opsonized platelets by the reticuloendothelial system. In addition, enhanced C5b-9 deposition on target cells is generally associated with cytolysis, and may thus contribute to thrombocytopenia by direct platelet damage, and damage to megakaryocytes affecting platelet production.

A number of studies over the last decade provide evidence that under conditions of thrombocytopenia, platelet RNA content correlates directly with platelet production (Takami et al., 2007; Ault et al., 1992; Rinder et al., 1993). This offers the ability to determine whether thrombocytopenia is due to marrow failure or to increased peripheral platelet destruction. In the present study we used the A-IPF, as a measure of reticulated platelets. The positive predictive value of a positive CAC for a low circulating A-IPF, when defined by a cut off of < 15 × 109/L, exceeded 90%. These data suggest that an enhanced CAC, measured on test platelets using plasma from patients with ITP, is likely associated with decreased platelet production in vivo, and/or a decreased circulatory half-life of young/reticulated platelets. The lower sensitivity and negative predictive value of the CAC may reflect the heterogeneity of platelet autoantibodies, particularly with respect to their complement fixing capacity, and any potential consumption or deficiency of complement components in vivo affecting overall plasma complement levels.

Since the pathophysiology of ITP is multifactorial, it is not surprising that response to treatment is also variable. It is interesting in this regard that enhanced plasma CAC on immobilized platelets in the present test system appeared to be associated with an increase response rate to splenectomy. This observation may suggest a dual mechanism for platelet destruction involving Fc receptor mediated clearance of platelets opsonized by immunoglobulins in the reticuloendothelial system and complement dependent phagocytosis of platelets by splenic macrophages. Additional studies with larger patient cohorts are required to evaluate complement deposition on patient platelets in vivo in order to further elucidate the role of complement in platelet destruction and response to therapy in patients with ITP.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants HL67211 (EIBP) from the National Institutes of Health, and an American Heart Association Heritage Affiliate postdoctoral award #0625900T to Wei Yin, the Children’s Cancer and Blood Foundation, Dana Hammond-Stuben, and an unrestricted grant from Alexion.

References

- 1.Ault KA, Rinder HM, Mitchell J, Carmody MB, Vary CP, Hillman RS. The significance of platelets with increased RNA content (reticulated platelets). A measure of the rate of thrombopoiesis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1992;98:637–646. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/98.6.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beardsley DS, Ertem M. Platelet autoantibodies in immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Transfus Sci. 1998;19:237–44. doi: 10.1016/s0955-3886(98)00037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Briggs C, Kunka S, Hart D, Oguni S, Machin SJ. Assessment of an immature platelet fraction (IPF) in peripheral thrombocytopenia. Brit J Haematol. 2004;126:93–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cines DB, Bussel JB, Liebman HA, Luning Prak ET. The ITP syndrome: pathogenic and clinical diversity. Blood. 2009;113:6511. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-129155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Del Conde I, Cruz MA, Zhang H, Lopez JA, Afshar-Kharghan V. Platelet activation leads to activation and propagation of the complement system. J Exp Med. 2005;201:871–879. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forster J, Katzikadamos Z, Zinn P. Platelet-associated IgG, IgM, and C3 in paediatric infectious disease. Helv Paediatr Acta. 1989;43:415–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.George JN, El-Harake MA, Aster RH. Thrombocytopenia due to enhanced platelet destruction by immunologic mechanisms. In: Beutler E, Lichtman MA, Coller BS, Kipps TJ, editors. Williams Hematology. 5th. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1995. pp. 1315–55. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamad OA, Ekdahl KN, Nilsson PH, Andersson J, Magotti P, Lambris JD, Nilsson B. Complement activation triggered by chondroitin sulfate released by thrombin receptor-activated platelets. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:1413–1421. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03034.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He R, Reid DM, Jones CE, Shulman NR. Spectrum of Ig classes, specificities, and titers of serum antiglycoproteins in chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 1994;83:1024–1032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huber-Lang M, Sarma JV, Zetoune FS, Rittirsch D, Neff TA, McGuire ST, Lambris JD, Warner RL, Flierl MA, Hoesel LM, Bebhard F, Younger JG, Drouin SM, Wetsel RA, Ward PA. Generation of C5a in the absence of C3: A new complement activation pathway. Nat Med. 2006;12:682–668. doi: 10.1038/nm1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kayser W, Mueller-Eckhardt C, Bhakdi S, Ebert K. Platelet associated complement C3 in thrombocytopenic states. Br J Haematol. 1983;54:353–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1983.tb02110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurata Y, Hayashi S, Aochi H, Nagamine K, Oshida M, Mizutani H, Tomiyama Y, Tsubakio T, Yonezawa T, Tarui S. Analysis of antigen involved in circulating immune complexes in patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Clin Exp Immunol. 1987;67:293–299. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuwana M, Kaburaki J, Kitasato H, Kato M, Kawai S, Kawakami Y, Ikeda Y. Immunodominant epitopes on glycoprotein IIb-IIIa recognized by autoreactive T cells in patients with immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2001;98:130–139. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lurhuma AZ, Riccomi H, Masson PL. The occurrence of circulating immune complexes and viral antigens in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Clin Exp Immunol. 1977;28:49–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McMillan R. Autoantibodies and autoantigens in chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Semin Hematol. 2000;37:239–248. doi: 10.1016/s0037-1963(00)90102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohali M, Maizlish Y, Abramov H, Schlesinger M, Bransky D, Lugassy G. Complement profile in childhood immune thrombocytopenic purpura: a prospective pilot study. Ann Hematol. 2005;84:812–815. doi: 10.1007/s00277-005-1085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panzer S, Szamait S, Boedeker RH, Haas OA, Haubenstock A, Mueller-Eckhardt C. Platelet associated immunoglobulin IgG, IgM, IgA and complement C3 in immune thrombocytopenic disorders. Am J Hematol. 1986;23:89–99. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830230203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parker C. Eculizumab for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Lancet. 2009;373:759–767. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peerschke EIB, Yin W, Grigg SE, Ghebrehiwet B. Blood platelets activate the classical pathway of human complement. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:2035–2042. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peerschke EIB, Yin W, Alpert DR, Roubey RAS, Salmon JE, Ghebrehiwet B. Serum complement activation on heterologous platelets is associated with arterial thrombosis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid antibodies. Lupus. 2009;18:530–538. doi: 10.1177/0961203308099974. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richards EM, Baglin TP. Quantitation of reticulated platelets: methodology and clinical application. Br J Heamatol. 1995;91:445–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1995.tb05320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ricklin D, Lambris JD. Compstatin: a complement inhibitor on its way to clinical application. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;632:273–292. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-78952-1_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rinder HM, Munz UJ, Ault KA, Bonan JL, Smith BR. Reticulated platelets in the evaluation of thrombopoietic disorders. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1993;117:606–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodeghiero F, Stasi R, Gernsheimer T, Michel M, Provan D, Arnold DM, Bussel JB, Cines DB, Chong BH, Cooper N, Godeau B, Lechner K, Mazzucconi MG, McMillan R, Sanz MA, Imbach P, Blanchette V, Kuehne T, Ruggeri M, George JN. Standardization of terminology, definitions and outcome criteria in immune thrombocytopenic purpura of adults and children: report from an international working group. Blood. 2009;113:2386–2393. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-162503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruiz-Delgado GJ, Vasquez-Garza E, Mendez-Ramirez N, Gomez-Almaguer D. Abnormalities in the expression of CD55 and CD59 surface molecules on peripheral blood cells are not specific to paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Hematology. 2009;14:33–37. doi: 10.1179/102453309X385089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Semple JW, Milev Y, Cosgrave D, Mody M, Hornstein A, Blanchette V, Freedman J. Differences in serum cytokine levels in acute and chronic autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura: relationship to platelet phenotype and antiplatelet T-cell reactivity. Blood. 1996;87:4245–4254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shattil SJ, Cunningham M, Wiedmer T, Zhao J, Sims PJ, Brass LF. Regulation of glycoprotein IIb-IIIa receptor function studied with platelets permeabilized by the pore-forming complement proteins C5b-9. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:18424–18431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takami A, Shibayama M, Orito M, Omote M, Okumura H, Yamashita T, Shimadoi S, Yoshida T, Nakao S, Asakura H. Immature platelet fraction for prediction of platelet engraftment after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2007;39:501–507. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trent RJ, Clancy RL, Danis V, Basten A. Immune complexes in thrombocytopenic patients: cause or effect? Br J Haematol. 1980;44:645–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1980.tb08719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Venneker GT, Asghar SS. CD59: a molecule involved in antigen presentation as well as down regulation of membrane attack complex. Exp Clin Immunogenet. 1992;9:33–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wiedmer T, Esmon CT, Sims PJ. Complement proteins C5b-9 stimulate procoagulant activity through prothrombinase. Blood. 1986;68:875–880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yin W, Ghebrehiwet B, Peerschke EIB. Expression of complement components and inhibitors on platelet microparticles. Platelets. 2008;19:225–233. doi: 10.1080/09537100701777311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]