Abstract

Background

We recently demonstrated multilineage somatic mosaicism in cutaneous-skeletal hypophosphatemia syndrome (CSHS), which features epidermal or melanocytic nevi, elevated fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF23) and hypophosphatemia, finding identical RAS mutations in affected skin and bone.

Objective

1) To provide an updated overview of CSHS; 2) To review its pathobiology; 3) To present a new CSHS patient; and 4) To discuss treatment modalities.

Methods

We searched PubMed for “nevus AND rickets,” and “nevus AND hypophosphatemia,” identifying cases of nevi with hypophosphatemic rickets or elevated serum FGF23. For our additional CSHS patient, we performed histopathologic and radiographic surveys of skin and skeletal lesions, respectively. Sequencing was performed for HRAS, KRAS, and NRAS to determine causative mutations.

Results

Our new case harbored somatic activating HRAS p.G13R mutation in affected tissue, consistent with previous findings. While the mechanism of FGF23 dysregulation is unknown in CSHS, interaction between FGF and MAPK pathways may provide insight into pathobiology. Anti-FGF23 antibody KRN23 may be useful in managing CSHS.

Limitations

Multilineage RAS mutation in CSHS was recently identified; further studies on mechanism are unavailable.

Conclusion

Patients with nevi in association with skeletal disease should be evaluated for serum phosphate and FGF23. Further studies investigating the role of RAS in FGF23 regulation are needed.

Keywords: Epidermal nevus, nevus syndrome, FGF23, CSHS, congenital melanocytic nevus, mosaicism, rickets

REVIEW

Genetic mosaicism

Mosaic organisms harbor two or more genetically distinct cell types. The generation of a mosaic requires a non-lethal somatic mutation in one cell of a developing embryo; this mutant cell divides and gives rise to mutant daughters which populate one or more parts of the organism [1]. Germline mosaicism occurs when a mutation affects germ cell progenitors, allowing the mutation to be inherited by subsequent generations, while pure somatic mosaicism spares germ cells and is thus non-inheritable. Genetic mosaicism of the skin can often be appreciated as lesions appearing along the lines of Blaschko, which follow the dorsal-ventral migration pattern of mutant ectodermal progenitors. Other patterns have been observed in somatic mosaicism of the skin, including phylloid patterns and large coat-like patches crossing the midline [1].

Nevus syndromes: a spectrum of genetic mosaicism

Congenital melanocytic nevi, and epidermal nevi which include both keratinocytic and sebaceous subtypes, are examples of somatic mosaicism arising via postzygotic activating RAS mutations [2–4]. Laser capture microdissection and whole exome sequencing found causative RAS mutations in epidermal keratinocytes and sebocytes of the lesions, whereas the underlying dermis, blood leukocytes, and adjacent, unaffected skin were wild type. In phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica, RAS mutations are found in both keratinocytes and melanocytes, giving rise to both organoid nevi and speckled lentiginous nevi [5].

While most cases of epidermal or melanocytic nevi are non-syndromic, some occur with abnormalities in other organs, including the eye, brain, muscle and vasculature [6–10]. Nevi with systemic findings (nevus syndromes) highlight the spectrum of potential end organ effects of RAS mosaicism, which depend on mutation timing during development. Schimmelpenning-Feuerstein-Mims syndrome, which features sebaceous nevi variably associated with neurologic abnormalities such as intellectual disability and epileptic seizures, as well as ocular and skeletal deformities, is likely due to an early mutation affecting a multipotent progenitor [2, 11]. Nearly all cases of syndromic nevi, especially those with abnormalities in non-ectoderm-derived tissues, demonstrate extensive skin surface involvement, consistent with early embryonic somatic mutation [12].

Cutaneous-skeletal hypophosphatemia syndrome (CSHS)

CSHS features epidermal or melanocytic nevi and hypophosphatemic rickets with elevated levels of a serum phosphatonin, fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF23) [13]. Patients often require phosphate and calcitriol supplementation to maintain mineral homeostasis.

In 1977, Aschinberg et al. reported the first case of CSHS in a 5-year-old boy with linear verrucous nevi and severe rickets [14]. Serum phosphate and tubular resorption of phosphate were low, indicating renal phosphate wasting (2.0mg/dl, normal: 3.0 – 4.5mg/dl), while serum alkaline phosphatase was high. Serum parathormone and calcium levels were within normal limits. At that time, FGF23 had not been identified. Interestingly, surgical excision of fibroangiomas from the face and left lower limb resulted in reduction of musculoskeletal pain and normalization of phosphate levels within four weeks. The authors postulated a secretory mechanism originating from the skin for pathobiology. They tested this hypothesis by homogenizing excised lesions and injecting them into a dog, and within one hour post-procedure found increased renal wasting of phosphate secondary to decreased reabsorption, though without changes in serum phosphate [14]. The authors did not find similar amelioration of phosphate excretion after excision of an epidermal nevus in the same patient, though subsequent reports did. Ivker et al. reported a female infant with CSHS who, despite medical therapy, exhibited a low serum phosphate of 0.87 – 0.97mmol/L (normal <1 year of age: 1.56 – 2.29mmol/L), along with an extensive linear epidermal nevus involving various parts of the body [15]. At 21 months of age, areas of the nevus were excised, with histopathologic confirmation of verrucous epidermal nevus. Shortly after the operation, serum phosphate values transiently climbed to 1.51 mmol/L, but later dropped, prompting subsequent nevus excisions at 27 months and stabilization of serum phosphate at 1.29 – 1.61mmol/L [15] [16]). It was unclear whether oral medication was continued during this period. Lastly, in a 2003 report by Saraswat et al. of a 22-year-old male with phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica and hypophosphatemic rickets, normalization of serum phosphate and reduction in phosphaturia was observed following CO2 laser ablation of the skin lesions [17]. It is unknown whether this normalization was sustained as there was no follow-up reported, and medications or supplements were not withheld during the procedure. Collectively, these reports suggest a parallel between the pathobiology of CSHS and tumor-induced osteomalacia (TIO), in which a phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor secretes FGF23 ectopically. Indeed, some have referred to nevus syndromes as a subtype of TIO, in which resection of the phosphaturic tumor quickly normalizes mineral panels and alleviates symptoms of osteomalacia [18]. Since FGF23 assays were not performed for the aforementioned nevus syndrome patients, it remains unknown whether the rickets resulted from elevated FGF23 or an alternative rachitogenic substance.

We recently determined the genetic basis of CSHS, which falls within the nevus syndrome spectrum. Our investigation included 5 CSHS patients (CSHS101-105, Table 1), with keratinocytic, sebaceous, or giant congenital melanocytic nevi (GCMN) occurring in association with hypophosphatemic rickets [13]. All epidermal nevi appeared in a Blaschkoid pattern, while the GCMN had a coat-like pattern. Lesional histopathology was characteristic: epidermal nevi demonstrated acanthosis, papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis and sebaceous hyperplasia (within nevus sebaceus), while the GCMN showed infiltration of melanocytes throughout the full thickness of the dermis along with hyperkeratosis. Radiographic survey revealed co-existence of rachitic features with large regions of dysplastic bone. Besides the skin and skeleton, all patients exhibited additional pathologic lesions in other tissues (Table 1). We studied the effects of epidermal nevus ablation, and found that neither surgical excision nor laser ablation correlated with improvement in mineral status or patient-reported quality of life. Immunolocalization and qPCR studies did not detect FGF23 expression within nevi from all 5 patients, consistent with prior reports [19].

Table 1.

Cutaneous-Skeletal Hypophosphatemia Syndrome patients demonstrate elevated FGF23 and hypophosphatemia in the setting of multilineage somatic RAS mutation.

| Patient | Skin | Age/Sex | RAS Mutation | Serum FGF23 (RU/ml) | Phosphate (mg/dl) | Additional findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSHS101 [13] | KEN | 5/F |

NRAS Q61R |

276 | 2.0 | Brainstem lipoma; thyroid nodule; splenic hemangiomas |

| CSHS102 [13] | KEN/NS | 12/F |

HRAS G13R1 |

279 | 2.3 | Sub-aortic valve stenosis |

| CSHS103 [13] | KEN/NS | 15/F |

HRAS Q61R |

527 | 1.5 | Eccrine poroma |

| CSHS104 [13] | GCMN | 4/F |

NRAS Q61R1 |

795 | 1.5 | Intraventricular choroidal mass; mass in medial canthus of right eye |

| CSHS105 [13] | KEN | 16/M | HRAS G13R | 104.52 | 2.2 | Colpocephaly; periventricular white matter paucity |

| CSHS106 [13] | PK | 12/F |

HRAS G13R |

982 | 1.2 | None |

CSHS=Cutaneous-skeletal hypophosphatemia syndrome.

Each patient is given a CSHS identifier. Cutaneous findings (KEN = keratinocytic epidermal nevi; NS = nevus sebaceus; GCMN = giant congenital melanocytic nevi; PK = phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica), age at time of FGF23 measurement, somatic RAS mutation, and additional pathology are presented. Reference normal values: FGF23, average for <18 years: 25 – 140 RU/ml; phosphate: 3.0 – 4.5 mg/dl.

RAS mutation was identified in both of the skin and dysplastic bone.

Intact FGF-23 is measured in pg/ml, the normal range of which is 8 – 54 pg/ml. Intact + C-terminal FGF23 is measured in RU/ml.

We employed exome sequencing to discover activating RAS mutations within the epidermis of the skin lesions, and found identical RAS mutations within dysplastic bone (Table 1). There was no evidence of loss of heterozygosity or secondary mutation that might otherwise account for pathogenesis. The presence of an identical RAS mutation in tissues of both ectodermal (skin) and mesodermal (bone) derivation suggested that the mutation occurred prior to gastrulation leading to multilineage mosaicism.

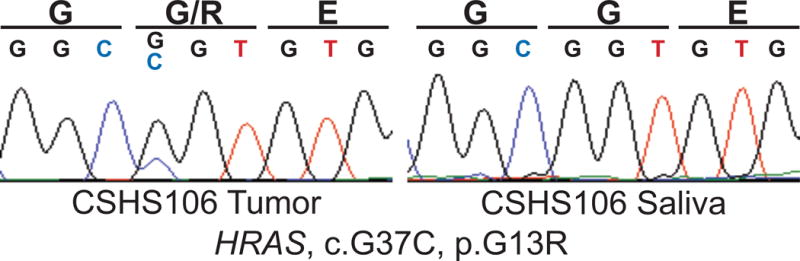

Since our initial report, we studied a 12-year-old female with phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica, severe rickets, and skeletal dysplasia (CSHS106, Table 1). Skin findings included compound-type congenital melanocytic nevi on the right upper back and left anterior thigh, linear epidermal nevus on the left abdomen and lateral forearms, and nevus sebaceus with an area of alopecia on the right scalp and right temporal region (Fig 1A, B). There was a linear verrucous nevus stretching from the right ear to the neck (Fig 1C). Histopathologic examination of a skin biopsy fromthe abdominal keratinocytic nevus demonstrated marked acanthosis and papillomatosis, (Fig 1D). Radiographic studies revealed diffuse skeletal hypomineralization, with lytic foci in the left hand and foot (Fig 2A – D). Vertebral bodies were shortened with evidence of dysplasia, some with hemibody asymmetry, all of which likely contributed to significant scoliosis. Skeletal maturation was delayed and she was wheelchair-dependent. No pathology was found in other organ systems. Characteristic changes in laboratory values included significantly low phosphate and elevated FGF23 levels (Table 1). Targeted Sanger sequencing of all exons of HRAS, NRAS, and KRAS identified somatic mutation in HRAS c.37G>C, G13R in the epidermis (Fig 3); based on our previous cohort, we presume that foci of dysplastic bone harbor this HRAS mutation. The mutation was further verified via RFLP digestion, as the mutation creates a de novo EagI site (data not shown).

Fig 1. Cutaneous-Skeletal Hypophosphatemia Syndrome. Clinical and histopathologic features.

(A) Congenital melanocytic nevi and keratinocytic epidermal nevi in Blaschkoid pattern on the back. (B) The right temporal region shows alopecia and papules of verrucous nevi. (C) A verrucous and keratinocytic epidermal nevus limited to the right side extends from the ear to the midline of the neck. (D) A 10X histopathology from a 3mm punch biopsy of abdominal keratinocytic epidermal nevus shows acanthosis and papillomatosis.

Fig 2. Cutaneous-Skeletal Hypophosphatemia Syndrome. Skeletal survey.

(A) Radiograph of the femurs demonstrates stretches of dysplastic bone with mixed sclerotic and lytic changes (arrows). (B) Multiple transverse defects in the shaft of the humerus representing pseudofractures (Losser’s Zones or Milkman’s Lines), which is a sign of osteomalacic bone (solid arrows) in the setting of dysplastic bone. (C, D) Consistent with the mosaic nature of CSHS, some rays are dysplastic (C, fifth ray of the hand, solid arrows; D, third, fourth, and fifth rays of the foot, solid arrows), and others are unaffected (dotted arrows).

Fig 3. Somatic RAS mutation in CSHS106.

Sanger sequencing of DNA isolated from the patient’s epidermal nevus demonstrates HRAS p.G13R mutation which is absent in the saliva.

FGF23 in CSHS

FGF23 is a 30kDa phosphatonin normally secreted from osteocytes, which regulates both phosphate and vitamin D homeostasis by modulating the expression of renal phosphate transporters and calcitriol-metabolizing enzymes, respectively [20–24]. Transgenic mice that overexpress FGF23 demonstrate reduced levels of sodium-phosphate cotransporters NaPi-2a and Napi-2c in the proximal tubules, increasing urinary excretion of phosphate, whereas ablation of FGF23 leads to hyperphosphatemia [23, 24]. 1-alpha hydroxylase, necessary for the conversion of calcifediol (25-hydroxyvitamin D) to bioactive calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3), is also suppressed by FGF23, while 24-hydroxlase, a catabolic enzyme of calcitriol, is increased [20, 21]. In the setting of pathologic overexpression, the combination of reduced phosphate and bioavailable vitamin D—which also facilitates absorption of phosphate in the gut—promotes rachitic symptoms including frequent fractures and immobility. Likewise, familial tumoral calcinosis, which results from loss of function mutations in FGF23, is characterized by hyperphosphatemia due to increased reabsorption of phosphate in the kidney [25].

For CSHS, given the lack of FGF23 expression in skin and the presence of activating somatic RAS mutations in the bone, we must consider a direct mechanism by which Ras signaling can influence FGF23 regulation. The RAS family of GTPases—HRAS, KRAS, and NRAS— is known for its role in carcinogenesis, as activating missense mutations in codons 12 (glycine), 13 (glycine) and 61 (glutamine) are found in a large number of cancers [26]. Normally, Ras is activated when bound to GTP, and inactivated upon hydrolysis of bound GTP to GDP. RAS mutations identified in neoplasms and nevi favor the binding of GTP and/or prevent GTP hydrolysis, rendering the Ras protein and its downstream signals constitutively active [27]. Although no direct association between RAS and FGF23 has been observed, there is clear evidence for a role of Ras in human skeletal development, as well as an established fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR)-RAS-MAPK signaling pathway which regulates expression of genes important for cell growth and survival [28–31]. FGFR1, for example, activates Ras in an FGF2-dependent manner to induce catabolism in articular chondrocytes, while FGFR3 was found to activate the Ras axis for cells to acquire resistance to vemurafenib in BRAF V600E mutant melanoma [32, 33]. Osteoglophonic dysplasia (OD) resulting from activating FGFR1 mutation features elevated FGF23 and hypophosphatemia, while antibody-mediated activation of FGFR1 in mice was found to increase serum FGF23 and induced hypophosphatemia [34]. NVP-BGJ398, a pan-specific FGFR inhibitor, further ameliorated hypophosphatemia and improved calcitriol biosynthesis in the Hyp mouse model [35]. Moreover, a recent study of 14 phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors (PMT) demonstrated a fibronectin-FGFR1 (FN-FGFR1) fusion in 9 of them (9/14, 60%), implicating tumor-induced osteomalacia to be a consequence of FGFR1 overexpression [36]. It is thus possible that constitutively active RAS mutations, which drive downstream signaling of FGFR1, could also induce overproduction of FGF23.

Alternatively, a RAS-mediated mechanism may be indirect, since regulation of FGF23 synthesis is complex with numerous endocrine, paracrine and autocrine inputs from the bone, gut, kidneys, and parathyroid glands [37–40]. Given that CSHS is likely to arise from a mesoderm-ectoderm progenitor, other cells derived from these germ layers that are important for FGF23 regulation may harbor RAS mutations. It is possible that a mosaic background provides an interface between mutant and wild-type cells and may be required for FGF23 secretion, as it is yet unknown whether FGF23 is secreted by mutant or adjacent wild-type cells. Evidence in favor of this hypothesis include germline RASopathies like Noonan or Costello syndrome, which feature constitutional activating RAS mutations without elevated FGF23 or hypophosphatemic rickets, though Costello patients occasionally demonstrate hypomineralized enamel [41, 42]. Furthermore, RAS mutant cell phenotypes are modified by intercellular communication with neighboring cells [26, 43].

Management of CSHS

Given our current understanding of the pathogenesis of CSHS, excision or ablation of nevi as treatment for hypophosphatemia is not advised. While some case reports suggest a therapeutic response, the results are confounded by concomitant oral medication or lack of follow-up. CSHS/nevus syndrome patients may undergo potentially painful removal procedures with no improvement [13, 19]. Not all patients in whom phosphate levels normalized were subject to nevi removal and there is evidence that phosphaturia improves over time [44]. We propose that early initiation of therapy consisting of oral phosphate and calcitriol can improve rachitic symptoms, and help heal dysplastic bone by enhancing mineralization. A multidisciplinary approach involving dermatology, endocrinology, pediatrics, orthopedic surgery, and physical rehabilitation is critical to mitigate complications and to maximize clinical outcomes. As CSHS is a RASopathy, agents targeting the MAPK pathway are theoretically possible for severe cases [45, 46]. Notably, KRN23, a human anti-FGF23 antibody that is administered subcutaneously once per month, has shown promising results in X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH), another disease of FGF23 excess. KRN23 may similarly prove useful in CSHS, especially for patients with poor compliance with or response to oral medication [47, 48].

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Lynn Boyden for critical review of the manuscript, Jing Zhou and Vincent Klump for technical assistance, and members of the Yale Center for Mendelian Genomics, including Richard P. Lifton, Shrikant M. Mane, and Kaya Bilguvar.

FUNDING SOURCES

This study was supported in part by a Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Clinical Scientist Development Award (KAC), the Yale Center for Mendelian Genomics (NIH U54 HG006504), and a Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Medical Student Research Fellowship (YHL).

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- CSHS

Cutaneous skeletal hypophosphatemia syndrome

- GCMN

Giant congenital melanocytic nevus

- TIO

Tumor induced osteomalacia

- FGF23

Fibroblast growth factor 23

- FGFR

Fibroblast growth factor receptor

- KEN

Keratinocytic epidermal nevus

- NS

Nevus sebaceus

- PK

Phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

IRB APPROVAL

The Yale School of Medicine Internal Review Board has reviewed and approved of this study. The work described has been carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki principles, and informed consent was obtained from all patients.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURE

None declared.

References

- 1.Biesecker LG, Spinner NB. A genomic view of mosaicism and human disease. Nature reviews Genetics. 2013;14(5):307–20. doi: 10.1038/nrg3424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Groesser L, Herschberger E, Ruetten A, Ruivenkamp C, Lopriore E, Zutt M, et al. Postzygotic HRAS and KRAS mutations cause nevus sebaceous and Schimmelpenning syndrome. Nature genetics. 2012;44(7):783–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levinsohn JL, Tian LC, Boyden LM, McNiff JM, Narayan D, Loring ES, et al. Whole-exome sequencing reveals somatic mutations in HRAS and KRAS, which cause nevus sebaceus. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2013;133(3):827–30. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charbel C, Fontaine RH, Malouf GG, Picard A, Kadlub N, El-Murr N, et al. NRAS mutation is the sole recurrent somatic mutation in large congenital melanocytic nevi. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2014;134(4):1067–74. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Groesser L, Herschberger E, Sagrera A, Shwayder T, Flux K, Ehmann L, et al. Phacomatosis pigmentokeratotica is caused by a postzygotic HRAS mutation in a multipotent progenitor cell. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2013;133(8):1998–2003. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calzavara Pinton P, Carlino A, Manganoni AM, Donzelli C, Facchetti F. Epidermal nevus syndrome with multiple vascular hamartomas and malformations. Giornale italiano di dermatologia e venereologia: organo ufficiale, Societa italiana di dermatologia e sifilografia. 1990;125(6):251–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okumura A, Lee T, Ikeno M, Shimojima K, Kajino K, Inoue Y, et al. A severe form of epidermal nevus syndrome associated with brainstem and cerebellar malformations and neonatal medulloblastoma. Brain & development. 2012;34(10):881–5. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seifert F, Jager T, Ring J, Chen W. Concurrence of linear epidermal nevus and nevus flammeus in a man with optic pathway glioma: coincidence or phacomatosis? International journal of dermatology. 2012;51(5):592–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawachi R, Kanekura T, Higashi Y, Usuki K, Kanzaki T. Epidermal nevus syndrome with hemangioma simplex. The Journal of dermatology. 1997;24(1):66–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1997.tb02744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoon Jung J, Chan Kim Y, Joon Park H, Woo Cinn Y. Becker’s nevus with ipsilateral breast hypoplasia: improvement with spironolactone. The Journal of dermatology. 2003;30(2):154–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2003.tb00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schimmelpenning GW. Clinical contribution to symptomatology of phacomatosis. Fortschritte auf dem Gebiete der Rontgenstrahlen und der Nuklearmedizin. 1957;87(6):716–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Losee JE, Serletti JM, Pennino RP. Epidermal nevus syndrome: a review and case report. Annals of plastic surgery. 1999;43(2):211–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim YH, Ovejero D, Sugarman JS, Deklotz CM, Maruri A, Eichenfield LF, et al. Multilineage somatic activating mutations in HRAS and NRAS cause mosaic cutaneous and skeletal lesions, elevated FGF23 and hypophosphatemia. Human molecular genetics. 2014;23(2):397–407. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aschinberg LC, Solomon LM, Zeis PM, Justice P, Rosenthal IM. Vitamin D-resistant rickets associated with epidermal nevus syndrome: demonstration of a phosphaturic substance in the dermal lesions. The Journal of pediatrics. 1977;91(1):56–60. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(77)80444-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ivker R, Resnick SD, Skidmore RA. Hypophosphatemic vitamin D-resistant rickets, precocious puberty, and the epidermal nevus syndrome. Archives of dermatology. 1997;133(12):1557–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Kieviet W, Slaats EH, Abeling NG. Pediatric reference values for calcium, magnesium and inorganic phosphorus in serum obtained from Bhattacharya plots for data from unselected patients. J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1986;24(4):233–42. doi: 10.1515/cclm.1986.24.4.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saraswat A, Dogra S, Bansali A, Kumar B. Phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica associated with hypophosphataemic vitamin D-resistant rickets: improvement in phosphate homeostasis after partial laser ablation. The British journal of dermatology. 2003;148(5):1074–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carey DE, Drezner MK, Hamdan JA, Mange M, Ahmad MS, Mubarak S, et al. Hypophosphatemic rickets/osteomalacia in linear sebaceous nevus syndrome: a variant of tumor-induced osteomalacia. The Journal of pediatrics. 1986;109(6):994–1000. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80283-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Narazaki R, Ihara K, Namba N, Matsuzaki H, Ozono K, Hara T. Linear nevus sebaceous syndrome with hypophosphatemic rickets with elevated FGF-23. Pediatric nephrology. 2012;27(5):861–3. doi: 10.1007/s00467-011-2086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo YC, Yuan Q. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and bone mineralisation. International journal of oral science. 2015 doi: 10.1038/ijos.2015.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Razzaque MS. The FGF23-Klotho axis: endocrine regulation of phosphate homeostasis. Nature reviews Endocrinology. 2009;5(11):611–9. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riminucci M, Collins MT, Fedarko NS, Cherman N, Corsi A, White KE, et al. FGF-23 in fibrous dysplasia of bone and its relationship to renal phosphate wasting. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2003;112(5):683–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI18399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shimada T, Kakitani M, Yamazaki Y, Hasegawa H, Takeuchi Y, Fujita T, et al. Targeted ablation of Fgf23 demonstrates an essential physiological role of FGF23 in phosphate and vitamin D metabolism. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2004;113(4):561–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI19081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bai X, Miao D, Li J, Goltzman D, Karaplis AC. Transgenic mice overexpressing human fibroblast growth factor 23 (R176Q) delineate a putative role for parathyroid hormone in renal phosphate wasting disorders. Endocrinology. 2004;145(11):5269–79. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farrow EG, Imel EA, White KE. Miscellaneous non-inflammatory musculoskeletal conditions. Hyperphosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis (FGF23, GALNT3 and alphaKlotho) Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25(5):735–47. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2011.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rauen KA. The RASopathies. Annual review of genomics and human genetics. 2013;14:355–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-091212-153523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schubbert S, Shannon K, Bollag G. Hyperactive Ras in developmental disorders and cancer. Nature reviews Cancer. 2007;7(4):295–308. doi: 10.1038/nrc2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsang M, Dawid IB. Promotion and attenuation of FGF signaling through the Ras-MAPK pathway. Science’s STKE: signal transduction knowledge environment. 2004;2004(228):pe17. doi: 10.1126/stke.2282004pe17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bentires-Alj M, Kontaridis MI, Neel BG. Stops along the RAS pathway in human genetic disease. Nature medicine. 2006;12(3):283–5. doi: 10.1038/nm0306-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsushita T, Chan YY, Kawanami A, Balmes G, Landreth GE, Murakami S. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 (ERK1) and ERK2 play essential roles in osteoblast differentiation and in supporting osteoclastogenesis. Molecular and cellular biology. 2009;29(21):5843–57. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01549-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Su N, Jin M, Chen L. Role of FGF/FGFR signaling in skeletal development and homeostasis: learning from mouse models. Bone Research. 2014;2 doi: 10.1038/boneres.2014.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yadav V, Zhang X, Liu J, Estrem S, Li S, Gong XQ, et al. Reactivation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway by FGF receptor 3 (FGFR3)/Ras mediates resistance to vemurafenib in human B-RAF V600E mutant melanoma. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287(33):28087–98. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.377218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan D, Chen D, Im HJ. Fibroblast growth factor-2 promotes catabolism via FGFR1-Ras-Raf-MEK1/2-ERK1/2 axis that coordinates with the PKCdelta pathway in human articular chondrocytes. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2012;113(9):2856–65. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 34.Wu AL, Feng B, Chen MZ, Kolumam G, Zavala-Solorio J, Wyatt SK, et al. Antibody-mediated activation of FGFR1 induces FGF23 production and hypophosphatemia. PloS one. 2013;8(2):e57322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wohrle S, Henninger C, Bonny O, Thuery A, Beluch N, Hynes NE, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptor signaling ameliorates FGF23-mediated hypophosphatemic rickets. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(4):899–911. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee JC, Jeng YM, Su SY, Wu CT, Tsai KS, Lee CH, et al. Identification of a novel FN1-FGFR1 genetic fusion as a frequent event in phosphaturic mesenchymal tumour. J Pathol. 2015;235(4):539–45. doi: 10.1002/path.4465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bergwitz C, Juppner H. Regulation of phosphate homeostasis by PTH, vitamin D, and FGF23. Annual review of medicine. 2010;61:91–104. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.051308.111339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quarles LD. Skeletal secretion of FGF-23 regulates phosphate and vitamin D metabolism. Nature reviews Endocrinology. 2012;8(5):276–86. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang WJ, Wang LF, Xu XY, Zhou Y, Jin WF, Wang HF, et al. Autocrine/paracrine action of vitamin D on FGF23 expression in cultured rat osteoblasts. Calcified tissue international. 2010;86(5):404–10. doi: 10.1007/s00223-010-9355-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Masuyama R, Stockmans I, Torrekens S, Van Looveren R, Maes C, Carmeliet P, et al. Vitamin D receptor in chondrocytes promotes osteoclastogenesis and regulates FGF23 production in osteoblasts. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2006;116(12):3150–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI29463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goodwin AF, Tidyman WE, Jheon AH, Sharir A, Zheng X, Charles C, et al. Abnormal Ras signaling in Costello syndrome (CS) negatively regulates enamel formation. Human molecular genetics. 2014;23(3):682–92. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tidyman WE, Rauen KA. Noonan, Costello and cardio-facio-cutaneous syndromes: dysregulation of the Ras-MAPK pathway. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2008;10:e37. doi: 10.1017/S1462399408000902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu M, Pastor-Pareja JC, Xu T. Interaction between Ras(V12) and scribbled clones induces tumour growth and invasion. Nature. 2010;463(7280):545–8. doi: 10.1038/nature08702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zutt M, Strutz F, Happle R, Habenicht EM, Emmert S, Haenssle HA, et al. Schimmelpenning-Feuerstein-Mims syndrome with hypophosphatemic rickets. Dermatology. 2003;207(1):72–6. doi: 10.1159/000070948. Epub 2003/07/02. doi: 70948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chappell WH, Steelman LS, Long JM, Kempf RC, Abrams SL, Franklin RA, et al. Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR inhibitors: rationale and importance to inhibiting these pathways in human health. Oncotarget. 2011;2(3):135–64. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rowinsky EK, Windle JJ, Von Hoff DD. Ras protein farnesyltransferase: A strategic target for anticancer therapeutic development. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1999;17(11):3631–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.11.3631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carpenter TO, Imel EA, Ruppe MD, Weber TJ, Klausner MA, Wooddell MM, et al. Randomized trial of the anti-FGF23 antibody KRN23 in X-linked hypophosphatemia. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014;124(4):1587–97. doi: 10.1172/JCI72829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Imel EA, Zhang X, Ruppe MD, Weber TJ, Klausner MA, Ito T, et al. Prolonged correction of serum phosphorus in adults with X-linked hypophosphatemia using monthly doses of KRN23. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015:jc20151551. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]