Abstract

Overseeing medication-taking is a critical aspect of dementia caregiving. This randomized controlled trial examined the efficacy of a tailored, problem-solving intervention designed to maximize medication management practices among caregivers of persons with memory loss. Eighty-three community-dwelling dyads (patient + informal caregiver) with a baseline average of 3 medication deficiencies participated. Home- and telephone-based sessions were delivered by nurse or social worker interventionists and addressed basic aspects of managing medications, plus tailored problem solving for specific challenges. The outcome of medication management practices was assessed using the Medication Management Instrument for Deficiencies in the Elderly (MedMaIDE) and an investigator-developed Medication Deficiency Checklist (MDC). Linear mixed modeling showed both the intervention and usual care groups had decreases in medication management problems as measured by the MedMaIDE (F=6.91, p<.01) and MDC (F=9.72, p<.01) at 2 months post-intervention. The phenomenon of reduced medication deficiencies in both groups suggests that when nurses or social workers merely raise awareness of the importance of medication adherence, there may be benefit.

Keywords: informal caregiver, medication adherence, memory loss, medication management

Introduction

Reducing medication errors and promoting medication adherence are well-recognized patient care priorities that are increasingly important for nurses in home care and other community-based geriatric care settings. Community-dwelling older adults with impaired cognition are at particular risk for medication errors and for experiencing more general problems with medication adherence.1–3 Barriers to medication adherence among such individuals have been documented to include patients’ cognitive symptoms (difficulty understanding new directions), behavioral problems (uncooperativeness), and functional deficits (e.g., scheduling medications into a routine). In addition to these illness-related barriers, recent studies suggest that prescriber factors, such as the total daily pill burden, and environmental factors, like living alone, can also contribute to medication nonadherence in cognitively impaired older adults.4–7

As compared to other populations, studies of interventions to improve medication adherence among cognitively impaired older adults are limited and reveal mixed results. For example, findings from one published pilot study indicate that patient reminder systems may have a smaller magnitude of effect for cognitively impaired persons relative to other older adults.8 A pilot study by Ownby and colleagues showed that providing either automated reminders or tailored information may be beneficial for improving medication adherence in patients with memory loss.9 Similarly, another small study of 36 cognitively impaired Veterans with heart failure found pictorial medication sheets to improve adherence.10 While the interventions in these studies targeted patients, in practice, direct assistance by family and other informal caregivers remains the first line approach to ensuring that those with impaired cognition take medications in accordance with their prescriptions.11,12 A related line of research showing that dementia caregivers are slow to assume responsibility for administering patients’ medications and often wait until safety issues are overt11,13 underscores the need for medication management interventions that target caregivers.14 While at least one study showed that the involvement of family caregiver is associated with better medication adherence, qualitative research on this topic indicates that assuming responsibility for medication management can be a major source of stress for dementia family caregivers.12,15 Caregivers in two qualitative studies described frustration with working to avoid conflict and to address uncooperativeness with care recipients during medication administration, with caregivers in the study by While and colleagues poignantly emphasizing that these challenges persist despite the caregiver having adequate knowledge of the medication regimen.12 This suggests that the problems faced by family caregivers of those with cognitive impairment are complex and unlikely to be addressed by standard nursing interventions like medication education or the use of reminder systems. The objective of this study, therefore, was to develop and examine the efficacy of a tailored, problem-solving intervention on informal caregivers’ management of medications for community-dwelling persons with memory loss.

Material and Methods

Study Design and Setting

This was an unblinded, randomized controlled trial of a tailored medication management intervention targeting informal caregivers of community-dwelling persons with memory loss. An unblinded design was necessary because it was not feasible to blind participating caregivers to their group assignment. For example, the consent form specified that the number of study visits would vary by group assignment. Thus, caregivers h ad knowledge of their group assignment by virtue of the study visitation schedule.

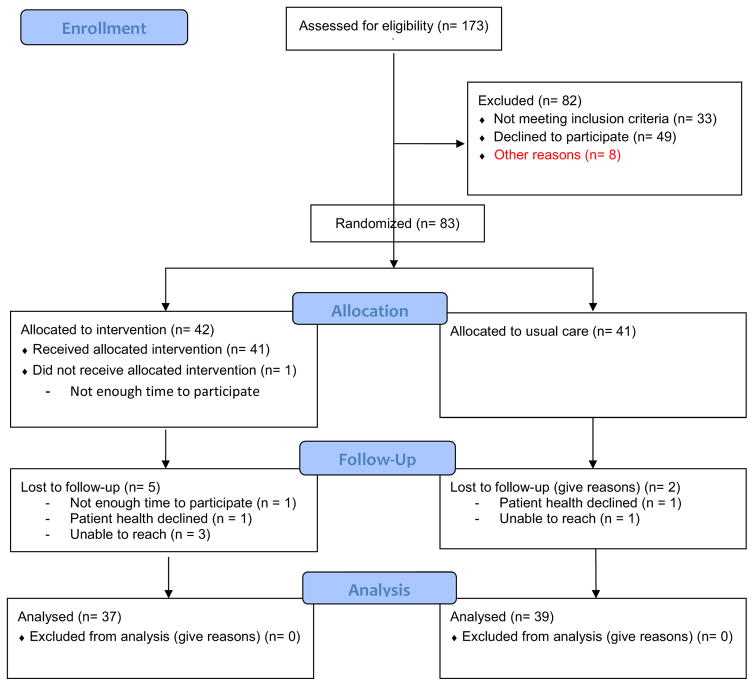

Caregivers were recruited from the community through mass mailings; mailings to family members of participants in the local Alzheimer Disease Research Center (NIA grant# blinded for peer review); brochures in pharmacies, clinics, adult day care centers; and support groups; and by advertising in other community venues (e.g., libraries, Meals on Wheels) (see Figure 1, CONSORT diagram). The setting for intervention delivery and study assessments was the participants’ homes. The University of [blinded for peer review] Institutional Review Board approved this research.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram

Study Population

Persons with memory loss and their informal caregivers were recruited in pairs, or dyads. Patient participants were included if they had self- or caregiver-reported memory loss necessitating help with medication taking, two or more co-morbid conditions requiring medication, and provided informed consent or assent (with proxy consent) to participate.

Informal caregivers were family members or kin-like friends of participants with memory loss and had to be at least 18 years or age, participate in the management of the patient’s medications, exhibit at least 1 deficiency on any of 3 measures of their ability to effectively manage the patient’s medications (see Measurements below), and live within 75 miles of the University of [blinded for peer review] (to ensure feasibility of home visits). Because the determination of whether a deficiency was present required administration of a research interview, this step of eligibility confirmation was established following informed consent.

Intervention

Intervention structure

The randomization ratio for this study was 1:1: intervention or usual care/control. Random group assignments were computer generated using permuted blocks within strata16 to ensure that the two groups had a balanced distributions on the following factors: assignment to either a nurse or social worker interventionist, the relationship of caregiver to the patient (spouse, son/daughter, other) and race/ethnicity (white, nonwhite). Intervention sessions were delivered by either a nurse or social worker and included 2 or 3 home visits, 2 weeks apart, followed by 2 to 3 telephone sessions, 7 to 10 days apart. The rationale for including interventionists from both nursing and social work was that, in practice, both home care nurses and case management social workers are equally likely to be positioned to support family caregivers who are assuming a role in administering medications to a person with memory loss. In this study, differences in the professional backgrounds of the two interventionists were accounted for by ensuring that both had the same total years of education (master’s degree) and amount of previous experience in dementia care, while both received the same training on delivery of the intervention and had the same unlimited access to a study pharmacist for the duration of the project. Assignment to either a nurse or social worker interventionist was kept consistent for the duration of the study.

Flexibility in the number of interventionist contacts (2 vs. 3) allowed for the intensity and length of the intervention to be tailored to match the level of challenges being experienced by each caregiver. The mean length of home visits was 40.05 minutes (SD 13.22) and telephone sessions was 13.42 minutes (SD 6.34). The total duration of the intervention was 8 weeks.

Intervention content

Guided by an intervention manual, sessions with the nurse or social worker interventionist addressed 7 basic aspects of the caregiver’s role in managing medications (i.e., “Common Problems” “Preventing Errors” and “Contingency Planning”; see Table 1). The 7 areas of emphasis in the manual were derived from a) a review of the problems typically encountered by caregivers as described in the literature, and b) input from multidisciplinary team members with expertise in dementia care. Caregivers were provided with a self-study version of the intervention manual to reference in between interventionist contacts. Each contact by the interventionist included one on one discussions between the interventionist and caregiver, focusing on one or more aspects of the caregiver’s role in managing medications. During each discussion, general features of an aspect were discussed and then the caregiver was encouraged to relate the content to a specific aspect of his or her own caregiving experience. For example, after the importance of contingency planning was discussed, the caregiver was asked to describe his or her own plans for a substitute medication manager should he or she become unable to fulfill that aspect of the role, either temporarily or permanently. If plans were not in place, the interventionist used a problem-solving approach to encourage the caregiver to develop a contingency plan. As strengths were identified, positive reinforcement was provided. Examples of strengths included the performance of appropriate medication management activities or statements that reflected motivation to promote medication safety. As challenges were identified, interventionists expanded on the basic information covered by the manual to engage caregivers in individually tailored problem126 solving beginning with challenges that caregivers self-identified as areas of greatest concern.17,18

Table 1.

Basic Aspects of Caregiver Role in Medication Management, Intervention Content

| Content Area | Examples of content |

|---|---|

| Caregiver Responsibilities in Medication Management | Identify extent of involvement in medication management (pharmacy pick up, storage, pill box organizing, medication administration) |

| Common Problems in Medication Administration/Taking | Patient believes that the medication has already been taken Dysphagia |

| Preventing Medication Errors | Five rights (right person, time, dose, route, medication) Refill promptly |

| Talking with Healthcare Providers about Your Loved One’s Medications | Importance of reporting over-the-counter medications to provider Use a checklist to prepare for appointments |

| Community Resources | Alzheimer’s Association Support Groups Local pharmacist |

| Contingency Planning | Importance of creating “back up” plan for someone else to administer medications in case the primary caregiver becomes unavailable |

| Changes in Medication Taking | Discard discontinued medications Log and communicate changes and reasons for changing |

Intervention maintenance

After the initial 8-week intervention period, caregivers received a series of maintenance phone calls to reinforce the skills learned during the intervention. Four bi-weekly calls occurred over the 8-week maintenance period.

Usual care

At baseline, dyads randomized to the usual care group received a pamphlet on medication safety from the Alzheimer’s Association and a manual of resources for their county of residence and surrounding counties as an attention control measure. Upon study completion, a caregiver self-study version of the intervention manual was provided to participants in the usual care group. In terms of the attention received as part of usual care, caregivers in this group received home visits for data collection, which typically lasted for at least an hour. The consent, screening and baseline visit typically exceeded two hours in length and included the administration of multiple interview-based instruments as well as an observation of the caregiver enacting medication administration. It should also be noted that, as a matter of promoting safety, any errors noted during medication reconciliation were brought to the attention of both caregivers and prescribers regardless of group assignment. In addition, all participants received care as usual from their health care providers.

Intervention fidelity

An independent rater randomly selected 10% of the cases from each interventionist for an audit of protocol fidelity. The rater reviewed audiorecordings of all available intervention sessions for these cases using an intervention fidelity checklist to determine percentage of agreement [POA] with study protocol (meaning, a determination of whether or not key elements of the intervention protocol were implemented), followed by an assessment of the quality of the interaction (QOI) between the interventionist and caregiver participant.19 The range of possible scores for the QOI assessment was 0 to 5, with 5 reflecting the highest quality interaction. The overall POA was 91.6% (SD 7.5). The overall interventionist QOI was 4.5 and the participant QOI was 4.5.

Measures

Using a questionnaire developed for the University of [blinded for peer review] School of Nursing Center for Research in Chronic Disorders (CRCD) socio-demographic information was collected for both patients and caregivers. 20 The Co-morbidity Questionnaire also developed for the CRCD was used to characterize the number and type of co-morbid conditions reported by both the patient and the caregiver. A detailed description of the psychosocial and clinical characteristics of the sample has been previously published.21 The outcomes for the current analysis were measured as follows.

The Medication Management Instrument for Deficiencies in the Elderly (MedMaIDE)22 uses a combination of interview and observation to assess a caregiver’s knowledge of medications, how to take medications, and how to procure medications. Each medication that the person is taking is reviewed during administration of this tool and 13 of the items are scored and summed, resulting in a score with a possible range from 0 to 13 where high scores indicating more deficiencies across the medications.

To capture additional deficiencies, the MedMaIDE was augmented by an investigator developed 15-item Medication Deficiency Checklist (MDC).21 The MDC uses caregiver interviews to assess for the presence of errors and problems such as “chewing pills or capsules”, “taking at the wrong time”, “repeating doses”, and “patient refuses/uncooperative.”21 Assessment of reliability for this investigator-developed checklist demonstrated a Cronbach's alpha of .38 and test-retest at 8 weeks r=.661, p=.000 (n= 49 control subjects). Concurrent validity was assessed using the 4-item Morisky self-reported adherence measure; findings showed a correlation of r=−.296, p=.007.

At baseline, an investigator developed Medication Reconciliation Form was administered to participating dyads and their prescribing providers. This form served to identify: medications that were prescribed and not being taken by the patient, medications that were being taken and not prescribed by the primary care provider, and whether the dosing was correct.21

Acceptability of the intervention was assessed by administration of a set of Likert scaled questions and eliciting open-ended comments during an exit interview at study completion.

Analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 22, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) was used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics were computed to describe the samples of caregivers and patients using mean/medians for central tendency and standard deviations/ranges for dispersion for continuous type variables and frequency counts and percentages for categorical variables. Two sample t-tests and contingency table analysis with chi-square tests of independence were used to compare the patient and caregiver samples by group assignment (intervention vs. usual care). Linear mixed modeling was used to examine the effect of group assignment over time. The level of significance was set at .05 for two-sided hypothesis testing.

Results

Sample characteristics

Our recruitment approach yielded 173 telephone inquiries about the study. Of those 173, 82 were excluded (see Figure 1) and 91 provided informed consent to the study. Of the 91 who consented, 83 were eligible and randomized into intervention (n=42) or usual care (n=41). There were no significant differences in caregiver and patient participant characteristics based on randomized group assignment (Table 2). Both participating caregivers and patients were predominantly female (70% and 60%, respectively) and Caucasian (88%). Caregivers exhibited a baseline average of 3 deficiencies in managing the care recipient’s medications (see Table 2). As previously reported, the most common types of medication deficiencies as identified using the Medication Deficiencies Checklist (MDC) at baseline were administering the medication at the wrong time, patient forgetting to take the medication, either member of the dyad losing pills, and caregivers forgetting to administer (completely omitting) medication doses.21

Table 2.

Sample Characteristics by Group and Dyad Member at Baseline

| Characteristic | Usual Care (n=41) | Intervention (n=42) | Test Statistics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Patients | Caregivers | Patients | Caregivers | Patients | Caregivers | |||

|

| ||||||||

| Value | p Value | p | ||||||

| Age, years | 80.15 ± 8.48 | 67.80 ± 11.2 | 79.67 ± 9.19 | 66.00 ± 12.8 | −0.247a | .806 | −0.683a | .497 |

| Formal education completed, years | 13.49 ± 3.02 | 15.41 ± 3.93 | 12.71 ± 3.85 | 14.40 ± 2.80 | −1.020a | .312 | −1.350a | .181 |

| Number of medications | 10.61 ± 5.89 | 10.79 ± 5.52 | 0.140a | .889 | ||||

| Number of co-morbidities | 9.024 ± 4.21 | 6.44 ± 3.59 | 8.691 ± 3.57 | 7.86 ± 3.69 | −0.390a | .698 | 1.775a | .080 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 22 (54) | 29 (71) | 28 (67) | 29 (69) | 1.470b | 0.226 | 0.028b | 0.867 |

| Male | 19 (46) | 12 (29 | 14 (33) | 13 (31) | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 37 (90) | 37 (90) | 34 (81) | 34 (81) | 1.450d | .229d | 1.450d | .229d |

| Black | 3 (7) | 3 (7) | 3 (7) | 4 (10) | ||||

| Other | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 5 (12) | 4 (9) | ||||

| Relationship to patient | ||||||||

| Spouse | 25 (61) | 22 (52) | 0.713b | 0.700 | ||||

| Child | 13 (32) | 17 (40) | ||||||

| Othere | 3 (7) | 3 (7) | ||||||

| Medication Management Deficiency Variable | Value | p | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Medication Reconciliation | ||||||||

| Total | 1.440 ± 1.90 | 1.840 ± 2.26 | 0.816a | 0.417 | ||||

| 1 or more | 23 (56) | 23 (55) | 0.021b | 0.884 | ||||

| MedMaIDE | 0.692 ± .768 | 0.833 ± .745 | 1.702a | .093 | ||||

| Medication Deficiencies Checklist | 3.290 ± 1.833 | 2.880 ± 1.70 | −1.060a | .292 | ||||

T-test;

Chi-Square;

2x2 chi-sq performed with white/non-white;

other includes: Child-in-law, sibling, niece/nephew, niece/nephew-in-law, and tenant; MCI: Mild Cognitive Impairment; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; MedMaIDE: Medication Management Instrument for

Satisfaction with the intervention

Upon completion of the study exit interview, most (88%) caregivers in the intervention group reported the intervention topics to be useful and relevant. Almost all (92%) reported that the intervention was helpful for managing the patient’s treatment plan.

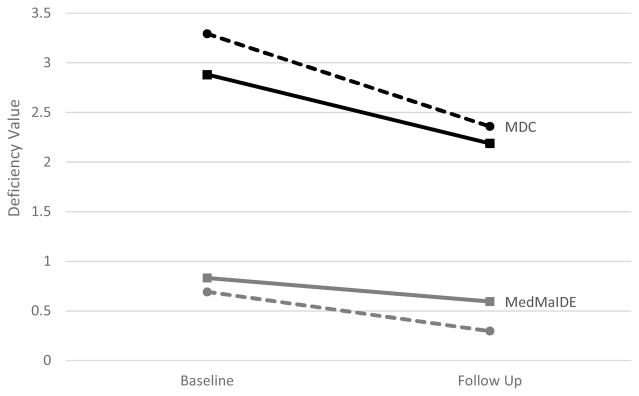

Adherence/Medication Management Outcomes

There were no significant time by randomization group interactions (MedMaIDE: F=.420, p=.52; MDC: F=0.22; p=.64). Rather, linear mixed modeling showed that both the intervention and usual care groups had significant decreases in the number of medication management problems as measured by the MedMaIDE (F=6.907, p<.01) and MDC (F=9.72, p<.01) at 2 months post-intervention. The average number of deficiencies at follow up was 2.19 (SD=1.52) for the intervention group and 2.36 (SD=1.51) for the usual care group. The most common type of deficiencies observed at follow up were dropping or losing pills (n = 31), caregivers forgetting to administer (completely omitting) medication doses (n = 27), administering the medication at the wrong time (n=25) and patient forgetting to take the medication (n=25). While each of these issues was reported in both the intervention and control groups, the 5th most common type of deficiency, wrong dose taken from pill keeper, was present only in the usual care group (n=10).

Discussion

At least one medication management deficiency was required for enrollment into this study; however, it was not uncommon for caregivers to exhibit multiple deficiencies at baseline, with an average of 3 and a maximum of 8 deficiencies detected across measures among dyads in this sample. This level of nonadherence is consistent with previous studies wherein rates of medication nonadherence for community-dwelling older adults with dementia are typically reported to exceed 30%.23,24 As such, this study adds to the growing body of evidence that nurses and other homecare providers are highly likely to encounter caregiving dyads (patients + family members) who are experiencing problems with medication adherence. In clinical practice, it has traditionally been assumed that transferring medication management responsibilities over to a family caregiver will resolve such problems, yet baseline data from this study suggest that problematic medication management practices seem to persist despite the involvement of a family caregiver in medication management.

Our study further adds to the literature by documenting that, in the context of home based care for persons with cognitive impairment, medication management deficiencies on the part of caregivers are modifiable and can decrease over time. This is an important finding given that previous studies of interventions to support self-management of medication taking among cognitively impaired older adults, have yielded inconsistent results and led to calls to address the complexity of such self-care with comprehensive interventions. In our sample, both the intervention and usual care groups improved within two months of study enrollment, dropping from an average of 3 to 2 medication deficiencies as measured using the MDC. While this improvement was expected in the intervention group, our finding of no significant time by randomization group interactions, suggests that the improvement could not be accounted for by only the intensive, tailored problem solving that intervention participants received.

One interpretation of our finding of improvement in the usual care group is that medication deficiencies may resolve over time without a prolonged intervention. It is also possible that the usual care group benefited from the level of attention that they received by being in the study. As noted above, caregivers in the usual care group participated in a face-to246 face baseline assessment by a study nurse or social worker which included questions about their knowledge of medications and approaches to managing them, underwent medication reconciliation, and received an initial set of resources with the understanding that additional resources would be forthcoming upon study completion. While it was assumed that this level of attention was akin to usual care, it is possible that the very act of having a nurse or social worker raise awareness of the importance of medication adherence may have prompted caregivers to self-identify, or consult with others in their social network to identity, approaches to addressing the problems they were experiencing.

Focused, brief approaches to improving medication adherence have shown promise in other populations.25–27 Our intervention was designed based on the assumption that caregivers of persons with cognitive impairment faced different challenges than caregivers of persons with physical health problems and therefore required additional nursing or social work support. The intervention was guided by a theoretical framework (social cognitive theory and self-efficacy theory) focused on tailored problem-solving. However, we standardized the intervention sessions to ensure that all participants received basic content 7 key aspects of the caregiver’s role in medication management. An adaptation of the intervention going forward may be to forgo the presentation of all elements of the caregiving role, and begin with a focused needs assessment to determine the individual caregiver’s primary challenge. Future research may also explore the feasibility and potential impact of having caregivers self-administer content from the intervention manual, either as a workbook or online module. Studies with larger samples may allow for direct comparisons of the intervention’s effect for different types of caregivers, such as spousal vs. nonspousal or male vs. female.

Limitations

There were several limitations in this study. First, the sample may have been biased toward caregivers who were highly motivated to get assistance with medication management as most participating caregivers self-referred to the study upon viewing advertisements. Second, it should be noted that medical records were not examined in this study so the etiology of patient participants’ cognitive impairment was not known. Third, the sample had limited racial and ethnic diversity, which constrains the ability to generalize findings to care dyads from underrepresented minority groups.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we developed and implemented a tailored, problem-solving intervention for informal caregivers who manage medications for those with memory loss. The intervention consisted of both core and tailored content and was well received by study participants. Two280 month outcomes show similar rates of decline in medication errors for both intervention and usual care participants. Potential explanations for the phenomenon of both groups improving include the possibility that merely raising awareness of the importance of medication adherence has a beneficial impact on caregivers of persons with cognitive impairment.

Figure 2.

Medication Deficiency by group and time. Note that a higher deficiency value indicates greater deficiency in a caregiver's management of the recipient's medication. MDC: Medication Deficiency Checklist; MedMaIDE: Medication Management Instrument for Deficiencies in the Elderly

Intervention

Intervention

Usual Care

Usual Care

Acknowledgments

Support: This study was supported by NIH/NINR, P01 NR010949, Adherence & HRQOL: Translation of Interventions, J. Dunbar-Jacob, Principal Investigator and by NIH/NIA, P50 AG05133, Alzheimer Disease Research Center, O. Lopez, Principal Investigator.

Footnotes

Portions of this research were presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference in Copenhagen, DK, July 2014.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jennifer H. Lingler, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing.

Janet Arida, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing.

Martin Houze, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing.

Robert Kaufman, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing.

Melissa Knox, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing.

Susan M. Sereika, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing.

Lisa Tamres, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing.

Judith Erlen, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing.

Carolyn Amspaugh, University of Pittsburgh School of Health and Rehabilitative Sciences.

Fengyan Tang, University of Pittsburgh School of Social Work.

Mary Beth Happ, The Ohio State University College of Nursing.

References

- 1.Kirkpatrick AC, Vincent AS, Guthrey L, et al. Cognitive impairment is associated with medication nonaderhence in asymptomatic carotid stenosis. Am J Med. 2014;127:1243–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hain DJ, Tappen R, Diaz S, et al. Cognitive impairment and medication self-management errors in older adults discharged home from a community hospital. Home Healthc Nurse. 2012;30:246–54. doi: 10.1097/NHH.0b013e31824c28bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thiruchselvam T, Naglie G, Moineddin R, et al. Risk factors for medication nonadherence in older adults with cognitive impairment who live alone. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27:1275–82. doi: 10.1002/gps.3778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borah B, Sacco P, Zarotsky V. Predictors of adherence among Alzheimer’s disease patients receiving oral therapy. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;8:1957065. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2010.493788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arlt S, Lindner R, Rosler A, et al. Adherence to medication in patients with dementia: Predictors and strategies for improvement. Drugs Aging. 2008;25:1033–47. doi: 10.2165/0002512-200825120-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell NL, Boustani MA, Skopelja EN, et al. Medication adherence in older adults with cognitive impairment: a systematic evidence-based review. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2012;10:165–77. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gellad WF, Grenard JL, Marcum ZA. A systematic review of barriers to medication adherence in the elderly: Looking beyond cost and regimen complexity. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2011;9:11–23. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Insel KC, Cole L. Individualizing memory strategies to improve medication adherence. Appl Nurs Res. 2005;18:199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ownby RL, Hertzog C, Czaja SJ. Tailored information and automated reminding to improve medication adherence in Spanish- and English-speaking elders treated for memory impairment. Clin Gerontol. 2012;35 doi: 10.1080/07317115.2012.657294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hawkins LA, Firek CJ. Testing a novel pictorial medication sheet to improve adherence in veterans with heart failure and cognitive impairment. Heart Lung. 2014;43:486–93. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaasalainen S, Dolovich L, Papaioannou A, et al. The process of medication management for older adults with dementa. J Nurs Health Care Chronic Illness. 2011;3:407–418. [Google Scholar]

- 12.While C, Duane F, Beanland C, et al. Medication management: the perspectives of people with dementia and their family carers. Dementia. 2013;12:734–50. doi: 10.1177/1471301212444056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erlen JA, Happ MB. Patients with Alzheimer’s disease who live at home: The challenge of medication taking. Paper presented at the 18th scientific sessions of the Eastern Nursing Research Socity; Cherry Hill, NJ. 2006. Apr. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brady r, Weinman J. Adherence to cholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease: A review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2013;35:351–63. doi: 10.1159/000347140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillespie RJ, Harrison L, Mullan J. Medication management concerns of ethnic minority family caregivers of people living with dementia. Dementia. 2015;14:47–62. doi: 10.1177/1471301213488900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pocock SJ. Clinical Trials: A Practical Approach. John Wiley; New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beck C, McSweeney JC, Richards KC, et al. Challenges in tailored intervention research. Nurs Outlook. 2010;58:104–10. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hugtenburg JG, Timmers L, Elders PJM, et al. Definitions, variants, and causes of nonadherence with medication: a challenge for tailored interventions. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:675–682. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S29549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wickersham K, Colbert A, Caruthers D, et al. Assessing fidelity to an intervention in a randomized controlled trial to improve medication adherence. Nurs Res. 2011;60:264–69. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e318221b6e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reference withheld for blind review

- 21.Reference withheld for blind review

- 22.Orwig D, Brandt N, Gruber-Baldini Medication management assessment for older adults in the community. Gerontologist. 2006;46:661–8. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.5.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haider B, Schmidt R, Schweiger C, et al. Medication adherence in patients with dementia: an Austrian cohort study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2014;28:128–33. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luzny J, Ivanova K, Jurickova L. Non-aderhence in seniors with dementia – a serious problem of routine clinical practice. Acta Medica. 2014;57:73–7. doi: 10.14712/18059694.2014.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siemianowski LA, Sen S, George JM. Impact of a pharmacy technician-centered medication reconciliation on optimization of antiretroviral therapy and opportunistic infection prophylaxis in hospitalized patients with HIV/AIDS. J Pharm Pract. 2013;26:428–33. doi: 10.1177/0897190012468451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brownlie K, Schneider C, Culliford R, et al. Medication reconcilitation by a pharmacy technician in a mental health assessment unit. Int J Clin Pharm. 2014;36:20–5. doi: 10.1007/s11096-013-9875-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conklin JR, Togami JC, Burnett A, et al. Care transitions service: a pharmacy-driven program for medication reconciliation through the continuum of care. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71:802–10. doi: 10.2146/ajhp130589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]