Abstract

Background:

Although the interleukin-1 (IL-1) plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of periodontitis, associations between IL1 gene cluster polymorphisms and the disease remains unclear.

Aims:

To investigate the importance of IL1B-511C>T (rs16944), IL1B +3954C>T (rs1143634), and IL1RN intron 2 variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) (rs2234663) polymorphisms, individually or in combination, as the risk factors of periodontitis in a Southeastern Brazilian population with a high degree of miscegenation.

Subjects and Methods:

A total of 145 individuals, with aggressive (aggressive periodontitis [AgP], n = 43) and chronic (chronic periodontitis [CP], n = 52) periodontitis, and controls (n = 50) were genotyped by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (IL1RN intron 2 VNTR) or PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) (IL1B-511 C>T and IL1B + 3954C>T) techniques.

Statistical Analysis:

The independent t-test, Chi-square, and Fisher's exact tests were used. The SNPStats program was used for haplotype estimation and multiplicative interaction analyses.

Results:

The IL1B +3954T allele represented risk for CP (odds ratio [OR] = 2.84), particularly in smokers (OR = 4.43) and females (OR = 6.00). The minor alleles IL1RN*2 and *3 increased the risk of AgP (OR = 2.18), especially the IL1RN*2*2 genotype among white Brazilians (OR = 7.80). Individuals with the combinations of the IL1B + 3954T and IL1RN*2 or *3-containing genotypes were at increased risk of developing CP (OR = 4.50). Considering the three polymorphisms (rs16944, rs1143634, and rs2234663), the haplotypes TC2 and CT1 represented risk for AgP (OR = 3.41) and CP (OR = 6.39), respectively.

Conclusions:

Our data suggest that the IL1B +3954C>T and IL1RN intron 2 VNTR polymorphisms are potential candidates for genetic biomarkers of periodontitis, particularly in specific groups of individuals.

Key words: Biomarkers, genotype combinations, haplotypes, interleukin-1, periodontitis, polymorphisms

Introduction

Periodontal disease is a chronic inflammatory process of infectious origin that includes gingivitis, an early reversible form of the disease, and periodontitis, which is characterized by loss of connective tissue, supporting alveolar bone, and eventually tooth.[1] The chronic periodontitis (CP) has slow progression and is the most common form of the disease, while the aggressive periodontitis (AgP) is rare, progresses rapidly and affects younger individuals.[2] Although bacterial plaque accumulation is essential, the number and variety of microorganisms are not related to the disease severity.[3] Individuals react differently to bacterial aggression, which reinforces the concept that the host response, rather than bacterial etiology, is the main determinant of disease expression.[4] It is very well known that the host response may be altered by several factors, including smoking and diabetes.[5] In addition, a study in twins showed a possible genetic influence on the development of periodontal disease.[6] It has been suggested that allelic variants of IL1 interfere with the production and function of interleukin-1 (IL-1), indicating that they might play an important role in the susceptibility and/or severity of periodontitis.[7,8,9] This is an interesting hypothesis because this family of cytokines is important in the metabolism of collagen in bone destruction and other inflammatory processes.[8,10]

The genes controlling the production of IL-1 are located on human chromosome 2q13. Two of them, named IL1A and IL1B, encode the proteins IL-1α and IL-1ί, respectively, while a third member, known as IL1RN, encodes a protein receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra). Associations between genetic polymorphisms of IL1 family and the severity of CP were initially assessed by Kornman et al.[3] The authors observed that the simultaneous occurrence of IL1A-889C>T and IL1B +3953/4C>T polymorphisms was associated with severe periodontitis in nonsmokers. Since then, polymorphisms in the IL1 gene cluster have been evaluated in patients with CP and/or AgP, with conflicting data.[11,12,13] Potential associations between IL1 polymorphisms and periodontitis remain inconclusive, reinforcing the importance of further studies in populations of different ethnicities.[9]

Brazilian studies have been conducted, but in most of them, periodontitis was not classified into chronic and aggressive forms, or periodontitis was studied in relation to another pathological condition, such as chronic kidney disease[14] and human immunodeficiency virus infection.[15] In addition, several studies involved only the IL1B +3954C>T polymorphism or this polymorphism in combination with other polymorphic loci not considered in our work, and in some of them, the control group was not in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium.[16,17,18]

Taking all this into consideration, the aim of this study was to investigate possible associations of two single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the IL1B gene, -511C>T (rs16944) and +3954C>T (rs1143634), and the penta-allelic 86 bp variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) polymorphism in intron 2 (rs2234663) of the IL1RN gene, individually or combined, with AgP and severe CP in a Southeastern Brazilian population, which was stratified by smoking status, gender, and skin color/ethnicity.

Subjects and Methods

Study population

One hundred and forty-five individuals living in Rio de Janeiro, aged between 20 and 60, were selected from two Faculties of Dentistry, Estαcio de Sα University, and Rio de Janeiro Catholic University. Information of all volunteers included records of medical history, periodontal history, and periapical radiography. All participants were in good general health and signed a consent form before being examined. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Pedro Ernesto University Hospital, State University of Rio de Janeiro (#1635 CEP/HUPE/UERJ).

A questionnaire containing the following information: gender, age, self-declared skin color/ethnicity (white and nonwhite Brazilians), smoking habit (nonsmoker and smoker/ex-smoker), medications used, systemic diseases, and socioeconomic status was applied to all participants. Periodontal examination included visible plaque index (VPI),[19] gingival bleeding (GBI),[19] probing pocket depth (PD), and clinical attachment loss (CAL). PD and CAL were measured at four sites per tooth (mesial, buccal, distal, palatal, or lingual) using a calibrated periodontal probe (HU-Friedy®, Chicago, IL, USA). Bone loss was measured on periapical radiographs with the aid of a millimeter rule. The distances between cementoenamel junction (CEJ) and the root apex, and the CEJ and the alveolar crest were calculated.[20]

Participants were classified according to clinical and radiographic data. The AgP group included 43 patients (mean age of 33.1 ± 4.8 years) with interproximal CAL and radiographic bone loss ≥50% of the length of the root structure on at least three teeth other than the first molars or incisors. The severe CP group was composed of 52 patients (mean age of 50.6 ± 5.8 years) showing at least five sites with CAL ≥6 mm. The control group included fifty periodontally healthy individuals (mean age of 40.1 ± 7.8 years) without evidence of CAL at interproximal sites and no radiographic signs of bone loss.

Collection of biological material and isolation of genomic DNA

A sample of oral mucosa cells was obtained by scraping the inner cheek with a sterile swab. After being transferred into a 1.5 mL plastic tube containing 1.0 mL of TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid - EDTA, pH 8.0) to release the cells, the collector swab was properly discarded. The samples were stored at −20°C until DNA extraction, which was performed as previously described.[21] An aliquot of the resulting DNA-containing solution was stored at 4°C until its use in the molecular assays aiming at IL1 genotyping, and a second aliquot was kept at −20°C for long-term storage.

Molecular analysis of IL1B and IL1RN polymorphisms

IL1B-511C>T and IL1B +3954C>T genotyping was performed by a polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) technique using primers described by Soga et al.[22] An aliquot of 5 μL of each amplicon was digested with 5 U of a specific restriction endonuclease for approximately 16 h, and the digestion products were resolved in ethidium bromide-stained polyacrylamide gels (8%).

Amplification of the VNTR of 86 bp in intron 2 of IL1RN gene was performed using a pair of primers described by Parkhill et al.[12] Electrophoretic analysis of the PCR products in 8% polyacrylamide gels stained with ethidium bromide allowed the identification of the genotypes formed by the combination of the five alleles.

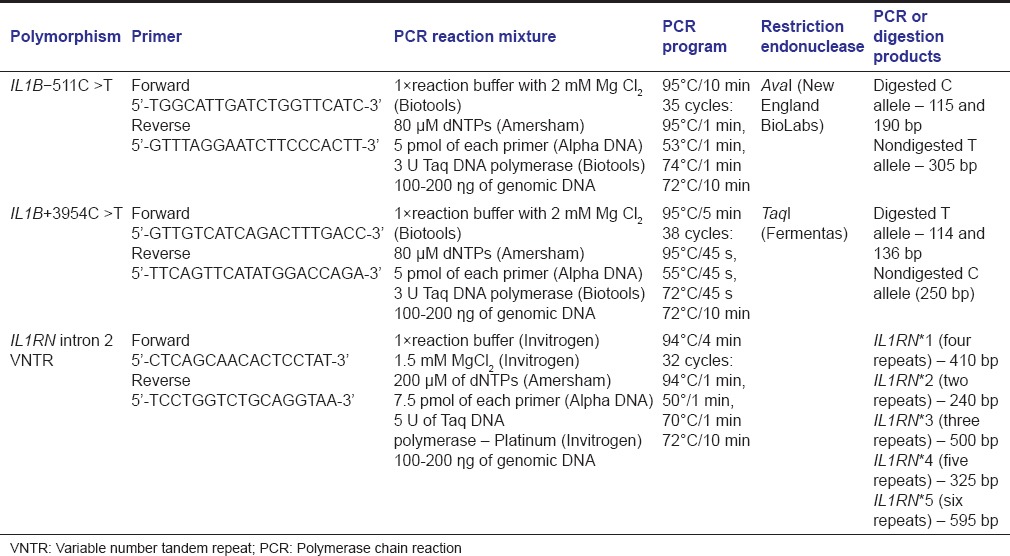

Primer sequences, amplification reaction mixtures (final volume of 25 μL), PCR programs, restriction endonucleases, and PCR or digestion products are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Genotyping conditions for the IL1B-511C>T, IL1B+3954C>T, IL1RN intron 2 variable number tandem repeat polymorphisms

Genotype identification was blindly performed by two scientists. Ten percent of the total samples were genotyped twice to validate the technique used.

Statistical analysis

The independent t-test was used to assess differences between normally distributed values. The control group was tested for deviation from the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium by the Chi-square test. The Fisher's exact test was used to analyze the differences in allele and genotype frequencies between the study groups. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to estimate the magnitude of association of IL1 polymorphisms and the susceptibility to AgP or severe CP. The reference categories were defined as the most frequent allele for each polymorphism and the homozygote genotype for this allele. Statistical analyses were performed using the software GraphPad Prism version 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Haplotype estimation and multiplicative interaction analyses between the IL1 polymorphisms and the response or other variables were performed using the online SNPStats program (http://bioinfo.iconcologia.net/SNPStats).[23] Statistical significance was set at 0.05.

Results

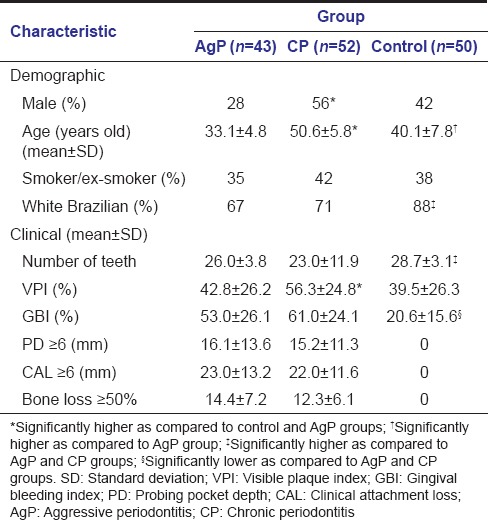

Demographic and clinical characteristics of AgP, CP, and control groups are presented in Table 2. The values of mean age and frequency of men were higher in the CP group in comparison with the control and AgP groups. Significantly more white Brazilians were observed among controls. Regarding clinical characteristics, the mean number of teeth was higher, whereas the mean % of sites with GBI was significantly lower in controls in comparison with the other two groups. The mean VPI was higher in the CP group than the corresponding values in control and AgP groups. Controls did not present sites with PD ≥6 mm, CAL ≥6 mm, and bone loss ≥50%, and no differences were found between AgP and CP groups with respect to these clinical characteristics.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of aggressive periodontitis and chronic periodontitis groups and controls

IL1B and Il1RN polymorphisms and the development of periodontitis

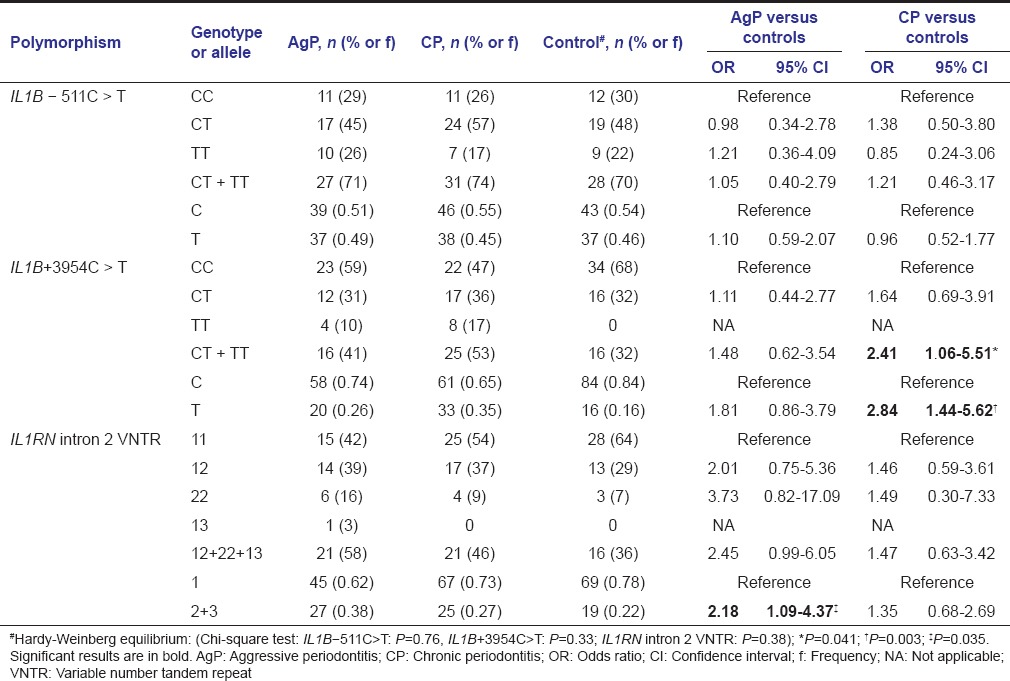

Genotype and allele distributions of the IL1B-511C>T, IL1B +3954C>T, and IL1RN intron 2 VNTR polymorphisms in the three study groups are shown in Table 3. The control group is in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium regarding the three polymorphisms. No differences in IL1B-511C>T genotype or allele frequencies were observed between patients with periodontitis, chronic or aggressive, and controls.

Table 3.

Genotype and allele distributions with respect to the three polymorphisms, IL1B-511C>T, IL1B+3954 C>T, and IL1RN intron 2 variable number tandem repeat, in aggressive periodontitis and chronic periodontitis groups and controls

For IL1B +3954C>T polymorphism, allele and genotype distributions were statistically different between CP and control groups, with higher frequencies of the allele T (OR = 2.84), in homozygosis or heterozygosis (CT + TT) (OR = 2.41), among patients with CP. The prevalence of the allele IL1B +3954T was even higher among smokers or ex-smokers (OR = 4.43; 95% CI = 1.29-15.24; P = 0.025), and females (OR = 6.00; 95% CI = 2.13-16.93; P = 0.027) of the CP group in comparison with controls.

Comparative analyses between AgP and control groups showed a significant difference for IL1RN intron 2 VNTR, with the variant alleles 2 (two repeats) and 3 (five repeats) being more prevalent in the AgP group (OR = 2.18). When only white Brazilian patients were considered, just a slightly higher frequency of the alleles IL-1RN*2 and *3 (OR = 3.08; 95% CI = 1.40-6.77; P = 0.006) was observed, but a markedly higher frequency of the ILRN*2 * 2 genotype (OR = 7.80; 95% CI = 1.34-45.28; P = 0.019) in the AgP group was found when the codominant genetic model (IL1RN*2*2 vs IL1RN*1*1) was used.

Genotype combination and haplotype regarding the three polymorphisms as risk factor for the development of periodontitis

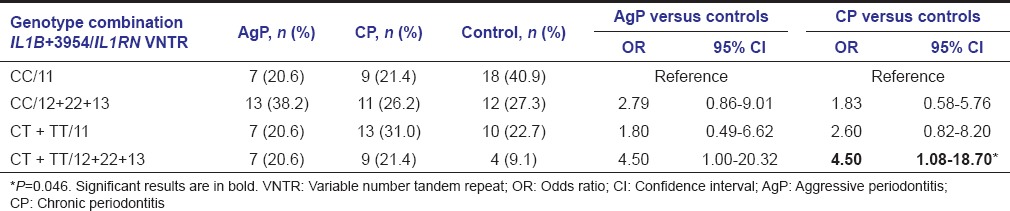

Genotype combinations of IL1B-511C>T with IL1B +3954C>T or IL1RN intron 2 VNTR polymorphisms did not reveal any difference between the study groups (data not shown). However, the combination of IL1B + 3954T allele-containing genotypes and IL1RN*2 or *3 alleles-carrying genotypes was significantly higher among patients with CP as compared with controls (OR = 4.50) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Genotype combinations concerning the IL1B+3954 C>T and IL1RN intron 2 variable number tandem repeat polymorphisms in aggressive periodontitis and chronic periodontitis groups and controls

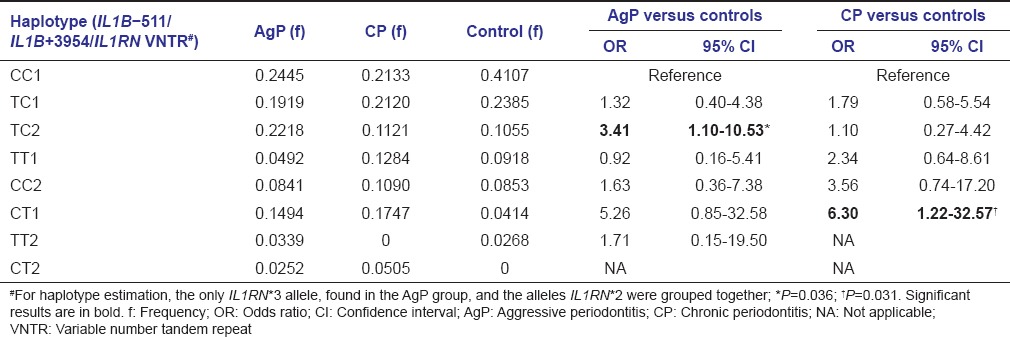

Regarding the three polymorphisms, IL1B-511C>T, IL1B +3954C>T, and IL1RN intron 2 VNTR, haplotype estimation showed higher frequencies of the haplotypes TC2 and CT1 in the AgP (OR = 3.41) and CP (OR = 6.30) groups, respectively, as compared to controls [Table 5].

Table 5.

Haplotype estimation with respect to the three polymorphisms, IL1B-511C>T, IL1B+3954 C>T, and IL1RN intron 2 variable number tandem repeat, in aggressive periodontitis and chronic periodontitis groups and controls

Discussion

Periodontitis development is related to the disruption of periodontal host-microbe homeostasis, and imbalances in pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines production upon microbial challenge play an important role in this process.[24] Allelic variations of the IL1 family genes may affect periodontitis susceptibility,[8] and several studies have been conducted although the association of IL1 polymorphisms with severe periodontitis, aggressive or chronic remains unclear. In this study, we investigated potential associations of two SNPs in the IL1B gene, IL1B-511C>T, and IL1B +3954C>T, and the VNTR polymorphism in intron 2 of the IL1RN gene with periodontal conditions in a Southeastern Brazilian population, which is characterized by a complex background with a high degree of miscegenation.[25]

High levels of IL-1ß in the gingival crevicular fluid are correlated to an increased susceptibility to periodontitis and seem to play a critical role in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease.[26] As the IL1B-511C>T polymorphism is located in the promoter region of the gene, it could interfere with the IL-1ß expression.[27] The T allele frequency showed to be high in Japanese,[7] Chinese,[28] Caucasian,[9] and South Indian populations.[27] The frequency of the allele T in our control group was 0.46, and no significant differences were observed between allele and genotype distributions in AgP or CP groups in comparison with controls [Table 2]. Similarly, different studies have failed to establish an association of the IL1B-511C>T polymorphism with the development of AgP and/or CP.[3,27,29] However, in a meta-analysis, a weak association between this polymorphism and CP was observed, with the T allele representing a risk for the disease, especially among Asians.[30]

Although the IL1 +3954C>T polymorphism has been extensively studied, its correlation with high IL-1β levels is still controversial.[11,14,31] Low prevalence of the IL1B +3954T allele has been reported in Chinese,[28,32] Thai,[33] and Japanese populations.[7] In contrast, the prevalence of individuals carrying the variant allele is high in Caucasians (31-50%).[9] In our control group, composed of 88% of white Brazilians [Table 1], the prevalence of the IL1B + 3954T allele was 0.16 [Table 2], which was similar to the values found in studies conducted in different regions of Brazil.[17,34,35]

No significant differences for IL1B +3954C>T genotype or allele distributions were observed between the AgP and control groups. Similar results were obtained by other researchers.[31,36] However, several reported results are not consistent with ours. Quappe et al.[37] observed an association between this polymorphism and AgP in a Chilean population, with the C allele showing a protective effect. Contradictory results were reported by Parkhill et al.,[12] who observed the higher frequency of the C allele in patients with AgP as compared to controls. Nevertheless, we observed risk effects for the T allele and the T allele-containing genotypes (CT + TT) on the development of CP. Our results are consistent with those obtained in other studies performed in Australia,[38] Chile,[39] Germany,[40] and Brazil,[34] and the results of the different meta-analysis, in which an association between the IL1B +3954C>T polymorphism and CP was found.[30,41,42]

Although Il-1RA may play a defense role in periodontitis, its increase is not sufficient to limit the release of IL-1β.[43] The allele IL1RN*2 has been associated with reduced levels of gene transcripts in patients with periodontitis.[14] In the present work, the minor alleles IL1RN*2 (two repeats) and *3 (five repeats) were overrepresented in the AgP group, in comparison with controls [Table 3], which suggests their effects on the risk of AgP in our population. The minor alleles IL1RN*2, *3, *4, *5 also proved to be associated with AgP in Japanese,[7] Turkish,[44] and Iranian individuals,[45] but their presence was found not to be important for the development of AgP in Caucasians[12,36,46] and Chinese populations.[28] On the other hand, the IL1RN intron 2 VNTR polymorphism showed no effect on the risk of CP in our population as had already been observed in other studies.[3,45,46] In fact, published data on the association of this polymorphism with periodontal diseases are inconsistent and conflicting, which may be explained by variation in the allele frequencies across different ethnic groups.[46,47] In a recent meta-analysis, for example, the authors suggested that IL1RN intron 2 VNTR polymorphisms might contribute to an increased risk of CP in Asians and a decreased risk of AgP in Caucasians.[48]

It is very well known that association between genetic and environmental factors may affect the disease susceptibility, and smoking habit has been considered an important risk factor for the progression and prognosis of periodontal diseases.[4,49] No difference was found between the number of current or former smokers in the AgP, CP, and control groups [Table 1]. However, our data indicated that smoking increased even more (1.56 times) the risk of IL1B +3954T allele carriers to develop CP (OR = 4.43). Other authors did not observe this association,[3,11] reinforcing the need of further investigations.

Gender has also been considered as a risk factor for periodontal disease, and it seems that differences in lifestyle rather than in genetic factors are responsible for the higher prevalence of severe periodontitis observed in men as compared to women.[49] Men were overrepresented in the CP groups in comparison with AgP and control groups [Table 1]. Nevertheless, the interaction analysis revealed that being of female sex markedly increased (2.11 times) the risk of IL1B +3954T allele-carriers to develop CP (OR = 6.00).

As previously mentioned, studies concerning possible associations of IL1 polymorphisms and periodontal diseases have been conducted in different ethnic groups, with inconsistent and sometimes contradictory results. In the present work, the skin color/ethnicity modified the risk of developing AgP in association with the IL1RN intron 2 VNTR polymorphisms as a higher prevalence of the IL1RN*2 or *3 alleles was observed in white Brazilian AgP patients in comparison with white Brazilian controls (OR = 3.08). This association was confirmed by using the codominant genetic model, and a markedly higher frequency of the ILRN*2*2 genotype was found in white Brazilian AgP patients (OR = 7.80).

Analysis of genotype combinations revealed a synergistic effect of both IL1B +3954C>T and IL1RN VNTR polymorphisms on the risk of developing CP, with individuals carrying composite genotypes that combine minor alleles at each locus (IL1B + 3954CT or TT and IL1RN VNTR *1*2, *1*3, or *2*2) presenting even higher risk of developing the disease (OR = 4.50) [Table 4]. In one of the few studies considering genotype combinations, the authors also suggested that the presence of those alleles could increase the risk of severe CP in nonsmoking patients.[50]

Finally, the haplotype estimation using the data corresponding to the three polymorphisms, IL1B-511C>T, IL1B +3954C>T, and IL1RN VNTR, allowed the identification of two risk haplotypes, TC2 e CT1, for aggressive [OR = 3.41] and chronic [OR = 6.30] periodontitis, respectively [Table 5]. Few studies regarding the association of IL1 gene cluster haplotypes with periodontitis have been reported, but the comparison with our results was not possible since these studies included either different genes or different polymorphic loci.[14,51]

Conclusions

In summary, interaction analyses revealed that the association of IL1B +3954C>T polymorphism with CP can be modified by smoking habit and gender, while the skin color/ethnicity modified the IL1RN VNTR polymorphism-associated risk for AgP. In addition, to our knowledge, this is the first report in a Brazilian population, and one of the few reports in the world, showing that IL1 haplotypes are associated with the risk of AgP and CP. However, further studies in larger populations, preferably of different ethnicities, might be conducted to validate our findings to use this information not only for developing prevention and diagnosis strategies but also for clarifying the molecular mechanisms of periodontitis.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was funded by FAPERJ - Research Support Foundation of the State of Rio de Janeiro (Grant # 102-043/2009).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank Amanda C. Pinto, Lais S. Araujo, and Elaine C. Santos of the Molecular Biology Laboratory (Biology Institute/UERJ) for their help in conducting this research.

References

- 1.Shapira L, Wilensky A, Kinane DF. Effect of genetic variability on the inflammatory response to periodontal infection. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32(Suppl 6):72–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:1–6. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kornman KS, Crane A, Wang HY, di Giovine FS, Newman MG, Pirk FW, et al. The interleukin-1 genotype as a severity factor in adult periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:72–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb01187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heitz-Mayfield LJ. Disease progression: Identification of high-risk groups and individuals for periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32(Suppl 6):196–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borrell LN, Papapanou PN. Analytical epidemiology of periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32(Suppl 6):132–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michalowicz BS, Diehl SR, Gunsolley JC, Sparks BS, Brooks CN, Koertge TE, et al. Evidence of a substantial genetic basis for risk of adult periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1699–707. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.11.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tai H, Endo M, Shimada Y, Gou E, Orima K, Kobayashi T, et al. Association of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist gene polymorphisms with early onset periodontitis in Japanese. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:882–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.291002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graves DT, Cochran D. The contribution of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor to periodontal tissue destruction. J Periodontol. 2003;74:391–401. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.3.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loos BG, John RP, Laine ML. Identification of genetic risk factors for periodontitis and possible mechanisms of action. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32(Suppl 6):159–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor JJ, Preshaw PM, Donaldson PT. Cytokine gene polymorphism and immunoregulation in periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 2004;35:158–82. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-6713.2004.003561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gore EA, Sanders JJ, Pandey JP, Palesch Y, Galbraith GM. Interleukin-1beta 3953 allele 2: Association with disease status in adult periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:781–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parkhill JM, Hennig BJ, Chapple IL, Heasman PA, Taylor JJ. Association of interleukin-1 gene polymorphisms with early-onset periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:682–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027009682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakellari D, Koukoudetsos S, Arsenakis M, Konstantinidis A. Prevalence of IL-1A and IL-1B polymorphisms in a Greek population. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:35–41. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.300106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braosi AP, de Souza CM, Luczyszyn SM, Dirschnabel AJ, Claudino M, Olandoski M, et al. Analysis of IL1 gene polymorphisms and transcript levels in periodontal and chronic kidney disease. Cytokine. 2012;60:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonçalves LS, Ferreira SM, Souza CO, Colombo AP. Influence of IL-1 gene polymorphism on the periodontal microbiota of HIV-infected Brazilian individuals. Braz Oral Res. 2009;23:452–9. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242009000400016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferreira SB, Jr, Trombone AP, Repeke CE, Cardoso CR, Martins W, Jr, Santos CF, et al. An interleukin-beta (IL-beta) single-nucleotide polymorphism at position and red complex periodontopathogens independently and additively modulate the levels of IL-beta in diseased periodontal tissues. Infect Immun. 2008;76:3725–34. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00546-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garlet GP, Trombone AP, Menezes R, Letra A, Repeke CE, Vieira AE, et al. The use of chronic gingivitis as reference status increases the power and odds of periodontitis genetic studies: A proposal based in the exposure concept and clearer resistance and susceptibility phenotypes definition. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39:323–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2012.01859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mendonça SA, Teixeira FG, Oliveira KM, Santos DB, Marques LM, Amorim MM, et al. Study of the association between the interleukin-1 ß c.3954C>T polymorphism and periodontitis in a population sample from Bahia, Brazil. Contemp Clin Dent. 2015;6:176–82. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.156040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ainamo J, Bay I. Problems and proposals for recording gingivitis and plaque. Int Dent J. 1975;25:229–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lavstedt S, Bolin A, Henrikson CO, Carstensen J. Proximal alveolar bone loss in a longitudinal radiographic investigation. I. Methods of measurement and partial recording. Acta Odontol Scand. 1986;44:149–57. doi: 10.3109/00016358609026567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klumb EM, Pinto AC, Jesus GR, Araujo M, Jr, Jascone L, Gayer CR, et al. Are women with lupus at higher risk of HPV infection? Lupus. 2010;19:1485–91. doi: 10.1177/0961203310372952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soga Y, Nishimura F, Ohyama H, Maeda H, Takashiba S, Murayama Y. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene (TNF-alpha) -1031/-863, -857 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are associated with severe adult periodontitis in Japanese. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:524–31. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solé X, Guinó E, Valls J, Iniesta R, Moreno V. SNPStats: A web tool for the analysis of association studies. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1928–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hajishengallis G. Immunomicrobial pathogenesis of periodontitis: Keystones, pathobionts, and host response. Trends Immunol. 2014;35:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manta FS, Pereira R, Caiafa A, Silva DA, Gusmão L, Carvalho EF. Analysis of genetic ancestry in the admixed Brazilian population from Rio de Janeiro using 46 autosomal ancestry-informative indel markers. Ann Hum Biol. 2013;40:94–8. doi: 10.3109/03014460.2012.742138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Figueredo CM, Ribeiro MS, Fischer RG, Gustafsson A. Increased interleukin-1beta concentration in gingival crevicular fluid as a characteristic of periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1999;70:1457–63. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.12.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shete AR, Joseph R, Vijayan NN, Srinivas L, Banerjee M. Association of single nucleotide gene polymorphism at interleukin-1beta 3954, -511, and -31 in chronic periodontitis and aggressive periodontitis in Dravidian ethnicity. J Periodontol. 2010;81:62–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li QY, Zhao HS, Meng HX, Zhang L, Xu L, Chen ZB, et al. Association analysis between interleukin-1 family polymorphisms and generalized aggressive periodontitis in a Chinese population. J Periodontol. 2004;75:1627–35. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.12.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeng XT, Liu DY, Kwong JS, Leng WD, Xia LY, Mao M. Meta-Analysis of Association Between Interleukin-1ß C-511T Polymorphism and Chronic Periodontitis Susceptibility. J Periodontol. 2015;86:812–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.140698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nikolopoulos GK, Dimou NL, Hamodrakas SJ, Bagos PG. Cytokine gene polymorphisms in periodontal disease: A meta-analysis of 53 studies including 4178 cases and 4590 controls. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:754–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yücel OO, Berker E, Mescil L, Eratalay K, Tepe E, Tezcan I. Association of interleukin-1 beta(+3954) gene polymorphism and gingival crevicular fluid levels in patients with aggressive and chronic periodontitis. Genet Couns. 2013;24:21–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Armitage GC, Wu Y, Wang HY, Sorrell J, di Giovine FS, Duff GW. Low prevalence of a periodontitis-associated interleukin-1 composite genotype in individuals of Chinese heritage. J Periodontol. 2000;71:164–71. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anusaksathien O, Sukboon A, Sitthiphong P, Teanpaisan R. Distribution of interleukin-1beta (3954) and IL-1alpha(-889) genetic variations in a Thai population group. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1796–802. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.12.1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moreira PR, de Sá AR, Xavier GM, Costa JE, Gomez RS, Gollob KJ, et al. A functional interleukin-1 beta gene polymorphism is associated with chronic periodontitis in a sample of Brazilian individuals. J Periodontal Res. 2005;40:306–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2005.00801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trevilatto PC, de Souza Pardo AP, Scarel-Caminaga RM, de Brito RB, Jr, Alvim-Pereira F, Alvim-Pereira CC, et al. Association of IL1 gene polymorphisms with chronic periodontitis in Brazilians. Arch Oral Biol. 2011;56:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fiebig A, Jepsen S, Loos BG, Scholz C, Schäfer C, Rühling A, et al. Polymorphisms in the interleukin-1 (IL1) gene cluster are not associated with aggressive periodontitis in a large Caucasian population. Genomics. 2008;92:309–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quappe L, Jara L, López NJ. Association of interleukin-1 polymorphisms with aggressive periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2004;75:1509–15. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.11.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rogers MA, Figliomeni L, Baluchova K, Tan AE, Davies G, Henry PJ, et al. Do interleukin-1 polymorphisms predict the development of periodontitis or the success of dental implants? J Periodontal Res. 2002;37:37–41. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2002.00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.López NJ, Jara L, Valenzuela CY. Association of interleukin-1 polymorphisms with periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 2005;76:234–43. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wagner J, Kaminski WE, Aslanidis C, Moder D, Hiller KA, Christgau M, et al. Prevalence of OPG and IL-1 gene polymorphisms in chronic periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:823–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karimbux NY, Saraiya VM, Elangovan S, Allareddy V, Kinnunen T, Kornman KS, et al. Interleukin-1 gene polymorphisms and chronic periodontitis in adult whites: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Periodontol. 2012;83:1407–19. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.110655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deng JS, Qin P, Li XX, Du YH. Association between interleukin-1ß C (3953/4) T polymorphism and chronic periodontitis: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Hum Immunol. 2013;74:371–8. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2012.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilowski L, Wiench R, Plocica I, Krzeminski TF. Amount of interleukin-1ß and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in periodontitis and healthy patients. Arch Oral Biol. 2014;59:729–34. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berdeli A, Emingil G, Gürkan A, Atilla G, Köse T. Association of the IL-1RN2 allele with periodontal diseases. Clin Biochem. 2006;39:357–62. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baradaran-Rahimi H, Radvar M, Arab HR, Tavakol-Afshari J, Ebadian AR. Association of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist gene polymorphisms with generalized aggressive periodontitis in an Iranian population. J Periodontol. 2010;81:1342–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.100073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scapoli C, Borzani I, Guarnelli ME, Mamolini E, Annunziata M, Guida L, et al. IL-1 gene cluster is not linked to aggressive periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2010;89:457–61. doi: 10.1177/0022034510363232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meisel P, Siegemund A, Dombrowa S, Sawaf H, Fanghaenel J, Kocher T. Smoking and polymorphisms of the interleukin-1 gene cluster (IL-1alpha, IL-1beta, and IL-1RN) in patients with periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 2002;73:27–32. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ding C, Zhao L, Sun Y, Li L, Xu Y. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist polymorphism (rs2234663) and periodontitis susceptibility: A meta-analysis. Arch Oral Biol. 2012;57:585–93. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Genco RJ, Borgnakke WS. Risk factors for periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 2013;62:59–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2012.00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laine ML, Farré MA, González G, van Dijk LJ, Ham AJ, Winkel EG, et al. Polymorphisms of the interleukin-1 gene family, oral microbial pathogens, and smoking in adult periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2001;80:1695–9. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800080301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu X, Offenbacher S, López NJ, Chen D, Wang HY, Rogus J, et al. Association of interleukin-1 gene variations with moderate to severe chronic periodontitis in multiple ethnicities. J Periodontal Res. 2015;50:52–61. doi: 10.1111/jre.12181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]