Abstract

Preventing relapse poses a significant challenge to the successful management of methamphetamine (METH) dependence. Although no effective medication currently exists for its treatment, racemic gamma vinyl-GABA (R,S-GVG, vigabatrin) shows enormous potential as it blocks both the neurochemical and behavioral effects of a variety of drugs, including METH, heroin, morphine, ethanol, nicotine, and cocaine. Using the reinstatement of a conditioned place preference (CPP) as an animal model of relapse, the present study specifically investigated the ability of an acute dose of R,S-GVG to block METH-triggered reinstatement of a METH-induced CPP. Animals acquired a METH CPP following a 20 day period of conditioning, in which they received 10 pairings of alternating METH and saline injections. During conditioning, rats were assigned to one of four METH dosage groups: 1.0, 2.5, 5.0, or 10.0 mg/kg (i.p., n = 8/group). Animals in all dosage groups demonstrated a robust and consistent CPP. This CPP was subsequently extinguished in each dosage group with repeated saline administration. Upon extinction, all groups reinstated following an acute METH challenge. On the following day, an acute dose of R,S-GVG (300 mg/kg, i.p.) was administered 2.5 hours prior to an identical METH challenge. R,S-GVG blocked METH-triggered reinstatement in all four groups. Given that drug re-exposure may potentiate relapse to drug-seeking behavior, the ability of R,S-GVG to block METH-triggered reinstatement offers further support for its use in the successful management of METH dependence.

Keywords: Gamma Vinyl-GABA, Vigabatrin, Methamphetamine, Conditioned Place Preference, Reinstatement, Relapse

INTRODUCTION

Initially confined to the western portion of the United States, methamphetamine (METH) abuse is emerging as an urgent public health epidemic as it steadily spreads eastward, affecting all regions of the country (Rawson and Condon 2007). Along with its powerfully addictive properties, the increasing popularity of METH may also be attributed to the ease with which it is produced in clandestine laboratories (O’Dea et al. 1997; Woolverton et al. 1984). One of the challenges to the successful treatment of METH dependence is drug-induced relapse. Currently, there is no effective medication for the management of METH relapse.

A useful animal model for measuring relapse is the extinction/reinstatement strategy predicated on the conditioned placed preference (CPP) paradigm (Tzschentke 2007; O’Brien and Gardner 2005). In this paradigm, a drug and a control treatment are administered several times in contextually distinct environments. After several of these pairing sessions, animals are tested in a drug-free state for their preference. During the CPP test, animals are given free access to both drug-paired and saline-paired environments, where the amount of time spent in the drug-paired environment is associated with the rewarding and incentive motivational properties of the drug (Bardo and Bevins 2000). This place preference can be extinguished with repeated saline administration in both environments in the absence of the drug, and then reinstated upon drug re-exposure (Shaham et al. 2003). Given that drug re-exposure is a common trigger potentiating relapse (Robinson and Berridge 1993), this model may be analogous to relapse in humans. Several rodent studies have used this procedure to demonstrate drug-induced reinstatement of a CPP following extinction with morphine (Manzanedo et al. 2001; Wang et al. 2000; Parker and McDonald 2000; Popik et al. 2006), cocaine (Itzhak and Martin 2002; Mueller and Stewart 2000), and methamphetamine (Li et al. 2002).

While establishing place preference and determining its subsequent extinction and reinstatement is useful, the ability to identify pharmacological treatments capable of blocking reinstatement offers the possibility of potentially managing relapse. One drug that shows remarkable promise is racemic gamma vinyl-GABA (R,S-GVG, vigabatrin). The utility of R,S-GVG as a potential treatment for METH dependence, as well as dependence to many other abused drugs, has been well documented. R,S-GVG inhibits METH, heroin, phencyclidine, ethanol, nicotine, and cocaine-induced increases in extracellular and synaptic mesolimbic dopamine levels (Gerasimov et al. 1999; Morgan and Dewey 1998; Ashby et al. 1999; Gerasimov and Dewey 1999; Dewey et al. 1999; Dewey et al. 1998; Dewey et al. 1992; Schiffer et al. 2001). In addition, it not only blocks the self-administration of cocaine, heroin, nicotine, and a combination of cocaine/alcohol (Stromberg et al. 2001; Kushner et al. 1999; Xi and Stein 2000; Paterson and Markou 2002), but it also inhibits cocaine-triggered lowering of brain stimulation reward thresholds (Kushner et al. 1997), sensitization (Gardner et al. 2002), and reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior (Peng et al. 2007). Finally, R,S-GVG blocks the expression and acquisition of a CPP to heroin, nicotine, toluene, and cocaine, suggesting that it can effectively abolish the incentive motivational value of many drugs of abuse (Paul et al. 2001; Lee et al. 2004; Dewey et al. 1998; Dewey et al. 1999).

Several clinical studies have recently established the utility of R,S-GVG as a potential treatment for cocaine or METH dependence. Initial preclinical studies demonstrated that in combination with cocaine, R,S-GVG did not result in cardiovascular or hepatic toxicity of sufficient significance to preclude further clinical trial testing (Molina et al. 1999). Therefore, two small open-label clinical trials using chronic R,S-GVG treatment were performed in cocaine and METH-dependent subjects. These studies suggested clinical efficacy (Brodie et al. 2005; Brodie et al. 2003) and established visual safety (Fechtner et al. 2006). Finally, and most recently, a U.S. registered (U.S. National Institutes of Health 2000; Identifier NCT00527683) randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in cocaine dependent subjects has been completed. Results from this study clearly demonstrated statistically significant therapeutic efficacy of R,S-GVG over placebo for the treatment of cocaine dependence. Despite this vast wealth of preclinical and clinical findings, the ability of R,S-GVG to block drug-triggered reinstatement of a CPP has yet to be determined. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to establish whether an acute dose of R,S-GVG could block METH-triggered reinstatement of a CPP following a prolonged period of extinction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 32, Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY, USA) served as subjects. Animals were housed in randomly assigned pairs, given access to food and water ad libitum, and maintained on a 12/12 light-dark cycle, with temperature and humidity kept constant. Prior to experimentation, rats were allowed to acclimate to their home cages for five days. During this time, each rat was handled daily for approximately 5 min to reduce handling stress during conditioning. At the start of conditioning, rats weighed 160–190 g and were an average age of 40 days. Procedures recommended by the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (1996) and the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Mammals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research (2003) were followed at all times. All experimentation was conducted in accordance with an IACUC-approved protocol and with strict adherence to NIH guidelines.

CPP apparatus

The commercial CPP apparatus (ENV-013, MED Associates Inc., St. Albans, VT, USA) consisted of three chambers: two pairing chambers (21.0 × 21.0 × 27.5 cm each) connected by a much smaller, middle chamber (11.4 × 25.4 cm). The two pairing chambers differed in visual and tactile cues. The black pairing chamber was entirely black with a steel, rod floor, while the white pairing chamber was white with black stripes (1.0 cm wide) and an orange, steel, mesh floor. The small middle chamber was neutral, with gray walls and a smooth gray platform floor. Guillotine doors controlled passage between chambers.

Conditioning Procedure

On the day preceding conditioning, all animals were given a drug-free pretest, in which they were permitted 20 min of unrestricted access to all three chambers of the CPP apparatus. Similar to criteria used in previous studies, animals demonstrating strong unconditioned preferences (>80% of pretest time) for one of the chambers were eliminated from the study (Gatley et al. 1996; Cruz et al. 2008). The CPP conditioning procedure took place over 20 consecutive days, with one pairing occurring per day during the light cycle, between the hours of 10:00 am and 2:00 pm. During these 20 days, each animal received 10 METH pairings alternating with 10 saline pairings. Assignment of METH- and saline-paired chambers was counterbalanced and random, so that half the animals were paired with METH in the black chamber while half were paired with METH in the white. Animals were randomly assigned to one of four METH dosage groups: 1.0, 2.5, 5.0, or 10.0 mg/kg (n = 8/group). In all instances, METH was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) during the pairing sessions. Following the administration of either saline or METH, animals were placed in their appropriate pairing chamber for 30 min. During this time, the guillotine doors remained closed to prevent access to the other chambers. It is important to note that the conduct of this study used an unbiased (any animal who demonstrated a pre-existing chamber bias was excluded) and counterbalanced design (an equal number of animals per dosage group received METH in the white and black chambers). All animals were randomly assigned to either chamber for METH pairing.

Expression of METH-induced CPP

On the day following the completion of conditioning (day 21), animals received a saline injection (0.1 mL, i.p.) and were placed in the middle, neutral chamber for 5 min of acclimation. After acclimation, the guillotine doors were opened to allow free access to both pairing chambers for 20 min. Using a digital video camera positioned above the CPP apparatus, the amount of time spent in each chamber was recorded and edited with a video studio program (Ulead VideoStudio version 8.0, Corel Corp., Eden Prairie, MN, USA), which was subsequently analyzed with animal behavior tracking software (TopScan version 1.0, Clever Sys., Inc., Reston, VA, USA).

Extinction of METH-induced CPP

Using a strategy similar to that previously reported by Cruz et al. (2008), beginning the day following their first CPP test (day 22), animals were tested once daily until extinction of the CPP was measured and established for each dosage group. Identical to the procedure used in the initial test session, animals received a saline injection (0.1 mL, i.p.) and were permitted 5 min to acclimate to the middle chamber. Animals were then given the 20 min of free access to all chambers, with the amount of time spent in each chamber digitally recorded and analyzed. Like the pairing sessions, this testing continued daily between the hours of 10:00 am and 2:00 pm until extinction of the CPP was established. Extinction was defined as having at least six consecutive days of no statistically significant CPP. This extinction timeframe is consistent with that reported using amphetamine to reinstate an established amphetamine-induced CPP (Cruz et al. 2008).

Blocking METH-triggered reinstatement with R,S-GVG

To reinstate METH-induced CPP, animals received a priming dose of METH (10% of the original pairing dose) before having free access to both pairing chambers for 20 min. If this small re-exposure was unable to produce a significant reinstatement, a larger dose of METH, equal to the pairing dose, was given on the next day. On the day immediately following successful reinstatement, all animals were pretreated with an acute dose of R,S-GVG (300 mg/kg, i.p.) 2.5 hours prior to receiving the effective reinstatement dose of METH. Animals were then given access to both pairing chambers for 20 min to determine R,S-GVG’s ability to inhibit METH-triggered reinstatement. The dose of R,S-GVG was kept constant across all animals, and was selected based on previous reports that 300 mg/kg (i.p.) is the lowest dose that maximally inhibits METH-induced increases in extracellular nucleus accumbens dopamine measured in freely moving Sprague-Dawley rats (Gerasimov et al. 1999).

Statistical analysis

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with subsequent Bonferroni t-tests were used to analyze raw seconds spent in all three chambers. Further, the time spent in the black and white pairing chambers was transformed into a percentage of the time spent in just those two chambers. Paired Students t-tests were conducted to determine whether or not the percentage of time spent in the METH- and saline-paired chambers differed within each METH dosage group. A one-way ANOVA was also used to determine the effect of the METH pairing dose on the percentage of time spent in the METH-paired chamber on the first CPP test day. In addition, preference scores for each animal were obtained by subtracting the percentage of time spent in the saline-paired chamber from the percentage of time spent in the METH-paired chamber. These preference scores were calculated on two test days, METH-induced reinstatement and blocking of reinstatement with R,S-GVG. Two-way (treatment × METH pairing dose) repeated measures ANOVA was used to analyze these preference scores. All results were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Expression of METH-induced CPP

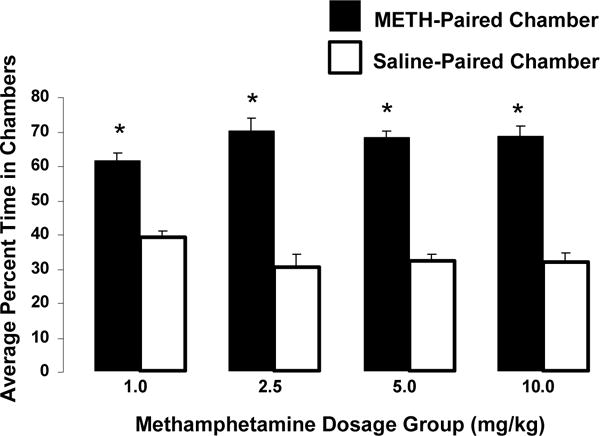

Following the conditioning period, animals in all METH dosage groups spent significantly more time in the METH-paired chamber compared to the saline-paired, and thus expressed a CPP (F2,31 = 71.48, p < 0.001; t = 11.92, p < 0.001). Figure 1 shows the results of this initial CPP test, by presenting the average percentage of time spent in the METH-paired and saline-paired chambers for all METH dosage groups. In addition, a one-way ANOVA indicated no significant difference between METH dosage groups in the percentage of time spent in the METH-paired chamber on the first CPP test day (F3,31 = 1.92, p = 0.15).

Fig. 1.

Expression of a METH-induced conditioned place preference (CPP). The average percentage of time spent in the METH-paired and saline-paired chambers for each METH dosage group during the first CPP test is shown. Paired Students t-tests revealed that animals in all dosage groups showed a significant CPP for the METH-paired chamber over the saline-paired chamber (p < 0.05 indicated by *). Specifically, the 1.0 mg/kg group spent an average of 61.2% of the time in the METH-paired chamber (p < 0.001). Similarly, the 2.5, 5.0, and 10.0 mg/kg groups spent an average of 69.9% (p < 0.001), 67.9% (p < 0.001), and 68.4% (p < 0.001) of the time in the METH-paired chamber, respectively. The average percentage of time spent in the METH-paired chamber was significantly greater across all dosage groups.

Extinction of METH-induced CPP

Extinction, defined as at least 6 consecutive days without a statictically significant CPP, occurred in all four METH dosage groups. However, the length of time required to reach extinction depended on the METH pairing dose. Animals receiving the highest dose of METH (10.0 mg/kg) were the first to achieve extinction after 9 days of saline. The 5.0 mg/kg dose group extinguished after 18 days. Finally, the 2.5 mg/kg dose group extinguished over the longest period of time, 25 days, while the 1.0 mg/kg required 16 days.

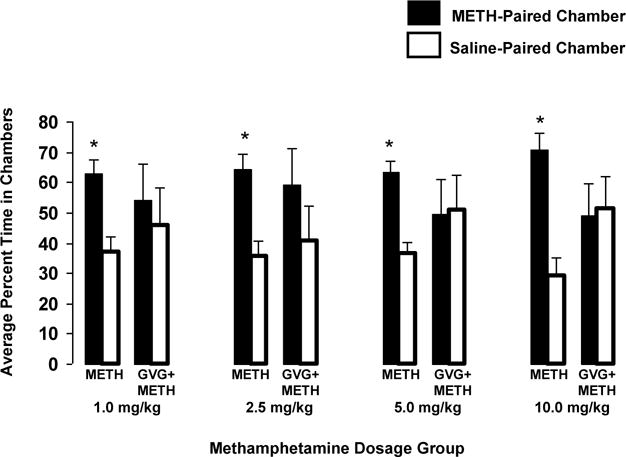

METH-triggered reinstatement of CPP and subsequent blocking with R,S-GVG

Following extinction of the CPP, re-exposure to METH triggered a consistent and robust reinstatement of the conditioned response in all dosage groups, as rats spent a significantly greater amount of time in the METH-paired chamber compared to the saline-paired chamber (F2,31 = 18.57, p < 0.001; t = 6.09, p < 0.001). Animals in both the 10.0 mg/kg and 5.0 mg/kg dose groups reinstated following a priming dose of METH (10% of the original pairing dose). However, animals in the lowest two dosing groups, 1.0 mg/kg and 2.5 mg/kg, required a dose equal to their original pairing dose. All animals successfully reinstated following a METH challenge. On the day following METH-triggered reinstatement, animals received R,S-GVG (300 mg/kg, i.p.) in their home cages 2.5 hours prior to receiving the same dose of METH used to trigger reinstatement. In all dosage groups, pretreatment with R,S-GVG completely abolished reinstatement. That is, following administration of R,S-GVG and METH, there was no longer a statistically significant difference between the time spent in the METH- and saline-paired chambers (F2,31 = 0.273, p < 0.761). This blocking effect was observed in the absence of any changes in gross locomotor activity or shuttling behavior (data not shown). Additionally, a two-way repeated measures ANOVA (treatment × METH pairing dose) conducted on preference scores showed a significant main effect of treatment (F1,31 = 4.93, p < 0.04), indicating that treatment with R,S-GVG significantly blocked reinstatement of the CPP. However, there was no significant interaction between the METH pairing dose and treatment (F3,1 = 0.50, p = 0.69), suggesting that R,S-GVG’s effectiveness at blocking reinstatement was not influenced by the METH pairing dose used during conditioning. Figure 2 presents the average percentage of time animals across all dosage groups spent in the METH- and saline-paired chambers during reinstatement and following an acute dose of R,S-GVG and another priming dose of METH.

Fig. 2.

METH-induced reinstatement of CPP (METH) and subsequent blocking of reinstatement with R,S-GVG (GVG + METH). The average percentage of time spent in the METH-paired and saline-paired chambers, across all dosage groups, is presented for two consecutive days. On the first day (designated as METH), rats in all dosage groups were re-exposed to a challenge dose of METH following a period of extinction. Upon re-exposure to METH, paired Student’s t-tests revealed that animals in all dosage groups spent a significantly greater average percentage of time in the METH-paired chamber over the saline-paired chamber, exhibiting a reinstatement of the CPP (p < 0.05 indicated by *). Specifically, the 1.0, 2.5, 5.0, and 10.0 mg/kg groups spent an average of 62.7% (p = 0.02), 64.4% (p = 0.0118), 63.5% (p = 0.0033), and 70.7% (p = 0.0043) of the time in the METH-paired chamber, respectively. On the second day (designated as GVG + METH), animals were pretreated with R,S-GVG (300 mg/kg, i.p.) 2.5 hours prior to the same METH challenge. Pretreatment with R,S-GVG blocked reinstatement in all dosage groups, as paired Students t-tests revealed that the average percentage of time animals in each dosage group spent in the METH-paired and saline-paired chambers was no longer significantly different. As can be seen, rats in the 1.0, 2.5, 5.0, and 10.0 mg/kg groups spent an average of 54.0% (p = 0.377), 59.3% (p = 0.337), 49.3% (p = 0.4796), and 48.8% (p = 0.4577) of the time in the METH-paired chamber.

DISCUSSION

The present study is the first to investigate the ability of R,S-GVG to block METH-induced reinstatement of an extinct CPP. Indeed, pretreatment with R,S-GVG (300 mg/kg, i.p.) 2.5 hours prior to a METH challenge blocked reinstatement at all four METH doses. These findings further advance the potential of R,S-GVG for effectively preventing METH-triggered relapse in METH dependent individuals.

METH produced a reliable and consistent CPP, regardless of the pairing dose. After a period of conditioning, animals spent significantly more time in the environment paired with the drug. Given this, it can be inferred that the previously neutral environmental stimuli have obtained a conditioned incentive value. These results are consistent with earlier studies in which many drugs of abuse, including METH, elicited a CPP (Mucha et al. 1982; Hiroi and White 1991; Funada et al. 2002; Sora et al. 1998; Slusher et al. 2001; Cunningham et al. 2003; Roma and Riley 2005; Daza-Losada et al. 2007; Tahsili-Fahadan et al. 2006). Subsequently, repeated daily saline administrations successfully extinguished this CPP in all groups. It is interesting to note that the number of days required to produce a reliable extinction (6 consecutive days without a significant CPP) appeared to be inversely related to the pairing dose. That is, the highest doses (10.0 and 5.0 mg/kg) required a mean of only 14 days while the lowest doses (2.5 and 1.0 mg/kg) required a mean of 22 days to extinguish. In a recent study using MDMA (3,4-methylen-dioxy-methamphetamine), or ecstasy as the conditioning drug, Daza-Losada and colleagues (2007) noted that regardless of the pairing dose (5.0, 10.0, or 20.0 mg/kg), animals extinguished their CPP all within a similar time period. Thus, while it may be intuitive to suspect that the rate of extinction is a process governed at least, in part, by the magnitude of the pairing dose or the number of pairings themselves, data from the present study in combination with others suggests a more complex relationship. Most importantly, however, these data demonstrate the need to measure and establish the complete extinction of a conditioned response prior to reinstating this behavior.

After extinction, re-exposure to METH produced a consistent and significant reinstatement of the CPP in all groups. Even after a period of time where animals showed no significant preference for the METH-paired chamber, a single dose of METH triggered a preference for the drug-conditioned chamber. These findings confirm and extend a large body of literature that utilized self-administration, rather than the establishment of a CPP, to show that re-exposure to METH could induce reinstatement of METH-seeking behavior following extinction (Xi and Kruzich 2007; Yan et al. 2006; Yan et al. 2007; Moffett and Goeders 2007; Davidson et al. 2007; Boctor et al. 2007; Anggadiredja et al. 2004; Hiranita et al. 2004). Thus, the reinstatement portion of our results further demonstrates that drug re-exposure is a strong trigger potentiating relapse when using CPP as an outcome measure.

Most importantly, the present study demonstrated that R,S-GVG (300 mg/kg, i.p.) successfully blocked METH-triggered reinstatement of a CPP following extinction across a range of METH doses. It is important to note that the potential to induce reinstatement of a CPP persists for long periods of time following extinction. Specifically, Cruz and colleagues (2008) demonstrated that the ability to reinstate an amphetamine-induced CPP using a priming dose of amphetamine remained for up to 30 days following extinction. This is an important point given the design of the present study. Based on these data, it is expected that animals in this study would have normally reinstated on the day they received R,S-GVG and METH, since it was only 1 day following their initial METH-triggered reinstatement. In addition, R,S-GVG’s inhibition of reinstatement most likely represents a true blocking effect caused by its actions upon reward mechanisms, as several possible caveats to interpretation have already been eliminated by prior studies.

It has been previously shown that R,S-GVG alone does not produce a conditioned place aversion or preference (Dewey et al. 1998; Paul et al. 2001), does not impair memory (Mazurkiewicz et al. 1993), and does not alter locomotor activity or produce catalepsy (Dewey et al. 1998). Therefore, it seems improbable that R,S-GVG inhibited reinstatement by producing dysfunction or an adverse effect.

Although the current investigation demonstrates the ability of R,S-GVG to block METH-triggered reinstatement, it limits insight into the possible mechanisms underlying this effect. One hypothesis suggests that reinstatement is triggered by proponent processes which activate reward pathways in a manner similar to the drug itself and that relapse and drug reward utilize common neural systems (Self and Nestler 1998). A large body of evidence further suggests that the rewarding and pleasurable effects of many drugs of abuse, including METH, arise from increases in dopamine levels in the mesolimbic system (Di Chiara and Imperato 1988; Gerasimov et al. 1999; Dewey et al. 1998; Ashby et al. 1999; Morgan and Dewey 1998; Gerasimov and Dewey 1999). Thus, it appears that dopaminergic neurotransmission is a critical determinant in both drug reward and relapse. Furthermore, dopamine release caused by METH re-exposure following a period of abstinence could act to “prime” drug-seeking behavior, by increasing the attractiveness and incentive salience of the drug and renewing a strong “wanting” and motivation (Robinson and Berridge 1993; Stewart et al. 1984). Given R,S-GVG’s mechanism of action, its ability to block METH-triggered relapse could plausibly be a result of its effect on GABAergic inhibition of dopamine transmission. R,S-GVG irreversibly inhibits GABA-transaminase, the enzyme responsible for the catabolism of GABA (Jung et al. 1977). This method of pharmacologically enhancing GABAeric transmission effectively decreases drug-induced increases in nucleus accumbens dopamine (Gerasimov and Dewey 2003). Further, using in vivo microdialysis techniques in freely moving animals previously paired to cocaine, R,S-GVG blocked cue-triggered increases in nucleus accumbens dopamine (Gerasimov et al. 2001). Therefore, it seems likely that pretreatment with R,S-GVG could offer “protection” against subsequent increases in brain dopamine elicited by METH re-exposure.

However, it is conceivable that a non-dopaminergic mechanism may instead underlie the current findings. A recent study by Peng et al. (2007) demonstrated that R,S-GVG inhibited cocaine-triggered reinstatement of cocaine self-administration. Interestingly, Peng and colleagues presented in vivo microdialysis data demonstrating that R,S-GVG, when administered systemically or locally into the nucleus accumbens, dose-dependently elevated extracellular GABA, but had no effect on nucleus accumbens dopamine. Given that cocaine administration reduces extracellular GABA levels (Cameron and Williams 1994; Centonze et al. 2002), R,S-GVG-induced increases in GABA may counteract this reduction in GABAeric transmission and explain, at least in part, R,S-GVG’s ability to inhibit cocaine-triggered reinstatement. Therefore, this report by Peng and colleagues suggests that R,S-GVG-induced increases in GABA may play a more direct role in blocking drug-induced reinstatement.

Regardless of the mechanisms underlying these effects, the implications of this study offer promise for METH-dependent individuals. However, caution must be taken when generalizing these results to a human population. Extinction in the current experiment was imposed, whereas the cessation of drug-seeking behavior in human populations occurs as a result of choice (Epstein and Preston 2003). If the factor of choice during drug cessation plays a prominent role in subsequent relapse, then this could be a limitation of the present study. In this study, R,S-GVG was also administered acutely, which differs from the clinical trials that have been conducted in which human abusers received chronic doses over a period of 9 weeks. Additionally, in contrast to the specificity of the current experiment, relapse in humans is a multifaceted phenomenon, most likely precipitated by many factors. Given that relapse in humans is usually examined retrospectively, opening the possibility of post hoc explanations and recall bias, the precise triggers have not been conclusively determined (Katz and Higgins 2003; Epstein and Preston 2003). The multidimensional nature of relapse is supported by previous rodent studies using various drugs of abuse that demonstrated reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior following a period of extinction that could be induced by other primers, such as exposure to stress (Lê et al. 1998) or to cues previously associated with drug administration (McFarland and Ettenberg 1997; de Wit and Stewart 1981). Future studies are needed to determine whether R,S-GVG can block not only METH-induced, but also cue-induced and stress-induced reinstatement of a METH CPP.

The present study demonstrates that an acute dose of R,S-GVG blocks METH-triggered reinstatement of a METH CPP. These findings further suggest that R,S-GVG may be efficacious in treating METH relapse, augmenting its effectiveness as a possible pharmacological treatment for drug dependence. Given that its safety and efficacy have been established in cocaine-dependent subjects (Brodie et al. 2005; Brodie et al. 2003; Fechtner et al. 2006) and that it offers the unique advantage of generating a long-lasting effect in the absence of producing tolerance, dependence, or withdrawal (Takada and Yanagita 1997), R,S-GVG holds potential for the successful management of METH dependence.

Acknowledgments

This research was carried out at Brookhaven National Laboratory under contract DE-AC02-98CH10886 with the U.S. Department of Energy and supported by its Office of Biological and Environmental Research. In addition, we acknowledge the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA, DA 15041 and DA 22346 to SLD) for their financial support. The authors thank Dr. Joanna Fowler and Mr. David L. Alexoff for critically reviewing this manuscript.

References

- Anggadiredja K, Sakimura K, Hiranita T, Yamamoto T. Naltrexone attenuates cue- but not drug-induced methamphetamine seeking; a possible mechanism for the dissociation of primary and secondary reward. Brain Res. 2004;1021:272–276. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby CR, Jr, Rohatgi R, Ngosuwan J, Borda T, Gerasimov MR, Morgan AE, Kushner S, Brodie JD, Dewey SL. Implication of the GABAB receptor in gamma vinyl-GABA’s inhibition of cocaine-induced increases in nucleus accumbens dopamine. Synapse. 1999;31:151–153. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199902)31:2<151::AID-SYN8>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardo MT, Bevins RA. Conditioned place preference: what does it add to our preclinical understanding of drug reward? Psychopharmacology. 2000;153:31–43. doi: 10.1007/s002130000569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boctor SY, Martinez JL, Jr, Koek W, France CP. The cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist AM251 does not modify methamphetamine reinstatement of responding. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;571:39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie JD, Figueroa E, Dewey SL. Treating cocaine addiction: from preclinical to clinical trial experience with γ-vinyl GABA. Synapse. 2003;50:261–265. doi: 10.1002/syn.10278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie JD, Figueroa E, Laska EM, Dewey SL. Safety and efficacy of γ-vinyl GABA (GVG) for the treatment of methamphetamine and/or cocaine addiction. Synapse. 2005;55:122–125. doi: 10.1002/syn.20097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron DL, Williams JT. Cocaine inhibits GABA release in the VTA through endogenous 5-HT. J Neurosci. 1994;14:6763–6767. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06763.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centonze D, Picconi B, Baunez C, Borrelli E, Pisani A, Bernardi G, Calabresi P. Cocaine and amphetamine depress striatal GABAergic synaptic transmission through D2 dopamine receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:164–175. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00299-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz FC, Marin MT, Planeta CS. The reinstatement of amphetamine-induced place preference is long-lasting and related to decreased expression of AMPA receptors in the nucleus accumbens. Neuroscience. 2008;151:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CL, Ferree NK, Howard MA. Apparatus bias and place conditioning with ethanol in mice. Psychopharmacology. 2003;170:409–422. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1559-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson C, Gopalan R, Ahn C, Chen Q, Mannelli P, Patkar AA, Weese GD, Lee TH, Ellinwood EH. Reduction in methamphetamine induced sensitization and reinstatement after combined pergolide plus ondansetron treatment during withdrawal. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;565:113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daza-Losada M, Ribeiro Do Couto B, Manzanedo C, Aguilar MA, Rodríguez-Arias M, Miñarro J. Rewarding effects and reinstatement of MDMA-induced CPP in adolescent mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1750–1759. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daza-Losada M, Rodríguez-Arias M, Aguilar MA, Miñarro J. Effect of adolescent exposure to MDMA and cocaine on acquisition and reinstatement of morphine-induced CPP. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.11.017. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey SL, Smith GS, Logan J, Brodie JD, Yu DW, Ferrieri RA, King PT, MacGregor RR, Martin TP, Wolf AP, et al. GABAergic inhibition of endogenous dopamine release measured in vivo with 11C-raclopride and positron emission tomography. J Neurosci. 1992;12:3773–3780. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-10-03773.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey SL, Morgan AE, Ashby CR, Jr, Horan B, Kushner SA, Logan J, Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Gardner EL, Brodie JD. A novel strategy for the treatment of cocaine addiction. Synapse. 1998;30:119–129. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199810)30:2<119::AID-SYN1>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey SL, Brodie JD, Gerasimov M, Horan B, Gardner EL, Ashby CR., Jr A pharmacologic strategy for the treatment of nicotine addiction. Synapse. 1999;31:76–86. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199901)31:1<76::AID-SYN10>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Stewart J. Reinstatement of cocaine-reinforced responding in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 1981;75:134–143. doi: 10.1007/BF00432175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G, Imperato A. Drugs abused by humans preferentially increase synaptic dopamine concentrations in the mesolimbic system of freely moving rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5274–5278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein DH, Preston KL. The reinstatement model and relapse prevention: a clinical perspective. Psychopharmacology. 2003;168:31–41. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1470-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fechtner RD, Khouri AS, Figueroa E, Ramirez M, Federico M, Dewey SL, Brodie JD. Short-term treatment of cocaine and/or methamphetamine abuse with vigabatrin: ocular safety pilot results. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:1257–1262. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.9.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funada M, Sato M, Makino Y, Wada K. Evaluation of rewarding effect of toluene by the conditioned place preference procedure in mice. Brain Res Protoc. 2002;10:47–54. doi: 10.1016/s1385-299x(02)00182-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner EL, Schiffer WK, Horan BA, Highfield D, Dewey SL, Brodie JD, Ashby CR., Jr Gamma-vinyl GABA, an irreversible inhibitor of GABA transaminase, alters the acquisition and expression of cocaine-induced sensitization in male rats. Synapse. 2002;46:240–250. doi: 10.1002/syn.10138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatley SJ, Meehan SM, Chen R, Pan D-F, Schechter MD, Dewey SL. Place preference and microdialysis studies with two derivatives of methylphenidate. Life Sci. 1996;58:345–352. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(96)00222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerasimov MR, Ashby CR, Jr, Gardner EL, Mills MJ, Brodie JD, Dewey SL. Gamma-vinyl GABA inhibits methamphetamine, heroin, or ethanol-induced increases in nucleus accumbens dopamine. Synapse. 1999;34:11–19. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199910)34:1<11::AID-SYN2>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerasimov MR, Dewey SL. Gamma-vinyl γ-aminobutyric acid attenuates the synergistic elevations of nucleus accumbens dopamine produced by a cocaine/heroin (speedball) challenge. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;380:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00526-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerasimov MR, Schiffer WK, Gardner EL, Marsteller DA, Lennon IC, Taylor SJC, Brodie JD, Ashby CR, Jr, Dewey SL. GABAergic blockade of cocaine-associated cue-induced increases in nucleus accumbens dopamine. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;414:205–209. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)00800-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerasimov MR, Dewey SL. Development of a GABAergic treatment for substance abuse using PET. Drug Dev Res. 2003;59:240–248. [Google Scholar]

- Hiranita T, Anggadiredja K, Fujisaki C, Watanabe S, Yamamoto T. Nicotine attenuates relapse to methamphetamine-seeking behavior (craving) in rats. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1025:504–507. doi: 10.1196/annals.1316.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiroi N, White NM. The amphetamine conditioned place preference: differential involvement of dopamine receptor subtypes and two dopaminergic terminal areas. Brain Res. 1991;552:141–152. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90672-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhak Y, Martin JL. Cocaine-induced conditioned place preference in mice: induction, extinction and reinstatement by related psychostimulants. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:130–134. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00303-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung MJ, Lippert B, Metcalf BW, Böhlen P, Schechter PJ. γ-Vinyl GABA (4-amino-hex-5-enoic acid), a new selective irreversible inhibitor of GABA-T: effects on brain GABA metabolism in mice. J Neurochem. 1977;29:797–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1977.tb10721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz JL, Higgins ST. The validity of the reinstatement model of craving and relapse to drug use. Psychopharmacology. 2003;168:21–30. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1441-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner SA, Dewey SL, Kornetsky C. Gamma-vinyl GABA attenuates cocaine-induced lowering of brain stimulation reward thresholds. Psychopharmacology. 1997;133:383–388. doi: 10.1007/s002130050418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner SA, Dewey SL, Kornetsky C. The irreversible gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) transaminase inhibitor gamma-vinyl-GABA blocks cocaine self-administration in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;290:797–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lê AD, Quan B, Juzytch W, Fletcher PJ, Joharchi N, Shaham Y. Reinstatement of alcohol-seeking by priming injections of alcohol and exposure to stress in rats. Psychopharmacology. 1998;135:169–174. doi: 10.1007/s002130050498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DE, Schiffer WK, Dewey SL. Gamma-vinyl GABA (Vigabatrin) blocks the expression of toluene-induced conditioned place preference (CPP) Synapse. 2004;54:183–185. doi: 10.1002/syn.20072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SM, Ren YH, Zheng JW. Effect of 7-nitroindazole on drug-priming reinstatement of D-methamphetamine-induced conditioned place preference. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;443:205–206. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01580-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzanedo C, Aguilar MA, Rodriguez-Arias M, Miñarro J. Conditioned place preference paradigm can be a mouse model of relapse to opiates. Neurosci Res Com. 2001;28:23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Mazurkiewicz M, Sirviö J, Riekkinen P., Sr Effects of single and repeated administration of vigabatrin on the performance of non-epileptic rats in a delayed non-matching to position task. Epilepsy Res. 1993;15:221–227. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(93)90059-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland K, Ettenberg A. Reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior produced by heroin-predictive environmental stimuli. Psychopharmacology. 1997;131:86–92. doi: 10.1007/s002130050269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffett MC, Goeders NE. CP-154,526, a CRF type-1 receptor antagonist, attenuates the cue-and methamphetamine-induced reinstatement of extinguished methamphetamine-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2007;190:171–180. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0625-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina PE, Ahmed N, Ajmal M, Dewey S, Volkow N, Fowler J, Abumrad N. Co-administration of gamma-vinyl GABA and cocaine: preclinical assessment of safety. Life Sci. 1999;65:1175–1182. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00351-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan AE, Dewey SL. Effects of pharmacologic increases in brain GABA levels on cocaine-induced changes in extracellular dopamine. Synapse. 1998;28:60–65. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199801)28:1<60::AID-SYN7>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucha RF, Van Der Kooy D, O’Shaughnessy M, Bucenieks P. Drug reinforcement studied by the use of place conditioning in rat. Brain Res. 1982;243:91–105. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)91123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller D, Stewart J. Cocaine-induced conditioned place preference: reinstatement by priming injections of cocaine after extinction. Behav Brain Res. 2000;115:39–47. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00239-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien CP, Gardner EL. Critical assessment of how to study addiction and its treatment: human and non-human animal models. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;108:18–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Dea PJ, Murphy B, Balzer C. Traffic and illegal production of drugs in rural America. NIDA Res Monogr. 1997;168:79–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker LA, McDonald RV. Reinstatement of both a conditioned place preference and a conditioned place aversion with drug primes. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;66:559–561. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00222-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson NE, Markou A. Increased GABA neurotransmission via administration of gamma-vinyl GABA decreased nicotine self-administration in the rat. Synapse. 2002;44:252–253. doi: 10.1002/syn.10073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul M, Dewey SL, Gardner EL, Brodie JD, Ashby CR., Jr Gamma-vinyl GABA (GVG) blocks expression of the conditioned place preference response to heroin in rats. Synapse. 2001;41:219–220. doi: 10.1002/syn.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng XQ, Li X, Gilbert JG, Pak AC, Ashby CR, Jr, Brodie JD, Dewey SL, Gardner EL, Xi ZX. Gamma-vinyl GABA inhibits cocaine-triggered reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior in rats by a non-dopaminergic mechanism. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popik P, Wrobel M, Bisaga A. Reinstatement of morphine-conditioned reward is blocked by memantine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:160–170. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawson RA, Condon TP. Why do we need an Addiction supplement focused on methamphetamine? Addiction. 2007;102:1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The neural basis of drug craving: an incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Res Rev. 1993;18:247–291. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roma PG, Riley AL. Apparatus bias and the use of light and texture in place conditioning. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;82:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer WK, Gerasimov M, Hofmann L, Marsteller D, Ashby CR, Brodie JD, Alexoff DL, Dewey SL. Gamma vinyl-GABA differentially modulates NMDA antagonist-induced increases in mesocortical versus mesolimbic DA transmission. Neuropsychopharm. 2001;25:704–712. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self DW, Nestler EJ. Relapse to drug-seeking: neural and molecular mechanisms. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;51:49–60. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Shalev U, Lu L, de Wit H, Stewart J. The reinstatement model of drug relapse: history, methodology and major findings. Psychopharmacology. 2003;168:3–20. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slusher BS, Thomas A, Paul M, Schad CA, Ashby CR., Jr Expression and acquisition of the conditioned place preference response to cocaine in rats is blocked by selective inhibitors of the enzyme N-acetylated-α-linked-acidic dipeptidase (NAALADase) Synapse. 2001;41:22–28. doi: 10.1002/syn.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sora I, Wichems C, Takahashi N, Li XF, Zeng Z, Revay R, Lesch KP, Murphy DL, Uhl GR. Cocaine reward models: conditioned place preference can be established in dopamine- and in serotonin-transporter knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:7699–7704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J, de Wit H, Eikelboom R. Role of unconditioned and conditioned drug effects in the self-administration of opiates and stimulants. Psychol Rev. 1984;91:251–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromberg MF, Mackler SA, Volpicelli JR, O’Brien CP, Dewey SL. The effect of gamma-vinyl-GABA on the consumption of concurrently available oral cocaine and ethanol in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;68:291–299. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00456-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahsili-Fahadan P, Yahyavi-Firouz-Abadi N, Khoshnoodi MA, Motiei-Langroudi R, Tahaei SA, Ghahremani MH, Dehpour AR. Agmatine potentiates morphine-induced conditioned place preference in mice: modulation by alpha2-adrenoceptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1722–1732. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada K, Yanagita T. Drug dependence study on vigabatrin in rhesus monkeys and rats. Arzneimittelforschung. 1997;47:1087–1092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzschentke TM. Measuring reward with the conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigm: update of the last decade. Addiction Biology. 2007;12:227–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. National Institutes of Health. ClinicalTrials.gov: a service of the U.S. National Institutes of Health. 2000 http://www.clinicaltrials.gov., Identifier NCT00527683.

- Wang B, Luo F, Zhang WT, Han JS. Stress or drug priming induces reinstatement of extinguished conditioned place preference. Neuroreport. 2000;11:2781–2784. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200008210-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolverton WL, Cervo L, Johanson CE. Effects of repeated methamphetamine administration on methamphetamine self-administration in rhesus monkeys. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1984;21:737–741. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(84)80012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi J, Kruzich PJ. Black agouti (ACI) rats show greater drug- and cue-induced reinstatement of methamphetamine-seeking behavior than Fischer 344 and Lewis rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;87:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi ZX, Stein EA. Increased mesolimbic GABA concentration blocks heroin self-administration in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:613–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y, Nitta A, Mizoguchi H, Yamada K, Nabeshima T. Relapse of methamphetamine-seeking behavior in C57BL/6J mice demonstrated by a reinstatement procedure involving intravenous self-administration. Behav Brain Res. 2006;168:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y, Yamada K, Nitta A, Nabeshima T. Transient drug-primed but persistent cue-induced reinstatement of extinguished methamphetamine-seeking behavior in mice. Behav Brain Res. 2007;177:261–268. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]