Abstract

Objective

To determine prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis (CT), Neisseria gonorrheae (GC), and Trichomonas vaginalis (TV) and describe factors associated with sexually transmitted infection (STI) in a pediatric emergency department (ED).

Methods

Adolescents aged 14–19 years presenting to a Midwestern pediatric ED were asked to provide urine for STI testing and complete a survey about previous sexual activity (PSA), high-risk behaviors, demographics, and visit reason (reproductive = genital-urinary complaints, abdominal pain, or female with vomiting). Comparisons between subgroups were analyzed using Chi-square test.

Results

Among 200 subjects (64% of approached), mean age was 15.6 years; 63% were female. Eleven subjects (6%; 95% CI 2.3–8.7) tested positive for ≥1 STI: 10 for CT (one denied PSA), 3 for TV (all co-infected with CT), and 1 for GC. Half reported PSA; of these, 71% reported ≥1 high-risk behavior, most commonly first sex before age 15 years (51%) and no condom at last sex (42%). Among those with PSA and non-reproductive visit (N=73), 11.0% had ≥1 STI (95% CI 3.4–18.1). Two factors were associated with greater likelihood of positive STI test: reporting PSA vs. no PSA (10% vs. 1%, p=0.005) and last sex within ≤1 month vs. >1 month (20% vs. 0%, p=0.001). In this sample, none of the following characteristics were associated with STI: insurance, race, high-risk behaviors, age, or ED visit reason.

Conclusion

About 1 in 10 sexually active adolescent ED patients without reproductive complaints had ≥1 STI. This suggests the need for strategies to increase STI testing for this population.

Keywords: Sexually transmitted diseases, adolescent health services, prevalence

INTRODUCTION

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) pose a significant public health problem and adolescents are disproportionately affected by STIs including Chlamydia trachomatis (CT), Neisseria gonorrheae (GC), and Trichomonas vaginalis (TV). 1 STIs have potential to produce morbidity including ectopic pregnancy, infertility, cervical cancer and HIV infection/AIDS.1 Many STIs are initially asymptomatic, which increases their risk for delayed diagnosis, complications, and disease transmission.

Many adolescents cared for in emergency departments (EDs) report high-risk sexual behaviors.2–5 Many adolescent ED users receive only episodic care and may have sexual healthcare needs that are not addressed during the visit, even if the visit is for genitourinary concerns.6 Adolescents comprise 15% of all ED visits and frequently have genitourinary complaints. 7 Adolescents face many barriers to sexual healthcare such as lack of access to knowledgeable providers, transportation, and insurance, as well as privacy concerns.8–9 Given the frequent use of EDs by adolescents, the high prevalence of risk behaviors, and the barriers to care, EDs have an important potential role in reducing the morbidity from and transmission of STIs.

While GC and CT can be accurately diagnosed using urine specimens, standard testing for TV has traditionally involved invasive methods that were also insensitive (i.e., wet mount). 10–11 Recently, a Trichomonas vaginalis nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) using a urine specimen has been approved by the FDA for in-vitro diagnostic use in females.

Some older data exist on prevalence of CT and GC among adolescent ED users, but there is little recent information about asymptomatic and younger adolescents. Studies using urine specimens from 2000–04 reported rates of CT and/or GC infection of 10–20%, but often focused on older adolescents (up to age 21). 12–14 While there are less data about TV, Goyal et al., using a vaginal specimen for rapid antigen testing, recently reported a prevalence of 10% among females presenting to the ED with symptoms concerning for STI.15

The primary objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of GC, CT, and TV among adolescents presenting to a pediatric ED. Other objectives were to describe sexual health behaviors and healthcare utilization and to identify behavioral and socio-demographic factors associated with STI.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a single site, cross-sectional study. The study protocol and consent procedures (including wavier of parental consent) were approved by the hospital institutional review board.

Study Setting and Population

The study was conducted at a free-standing, Midwestern children’s hospital. This urban hospital is a regional tertiary care center and a level one trauma center. Of the 70,000 annual visits, 9% were for patients aged ≥15 years. Patients are primarily non-White (67%) with government-issued or no insurance (71%).

We included patients aged 14–19 years seeking care for any reason. Personal sexual history did not affect eligibility: patients reporting either abstinence or any previous sexual activity (PSA) were included. Subjects were excluded if they reported any antibiotics in the previous 30 days, did not speak English, had illness or impairment impeding participation, had complaints of sexual assault or psychiatric illness, or were wards of state. We recruited subjects during four-hour blocks between 8 a.m. to midnight, selected before enrollment. Using arrival data from the prior year, recruitment shifts were weighted based on the proportion of adolescents who presented during each period for weekdays (Monday–Thursday) and weekends (Friday–Sunday). Eligible patients were approached sequentially.

Survey Tool

A multidisciplinary team developed the survey, based in part on national surveys and review of the literature.16–17 The survey, which took about 10 minutes to complete, was pilot tested with ten adolescents who found it understandable and easy to complete. Subjects were asked “Have you ever had any type of sex with a male or female—that is vaginal sex or anal sex or oral sex?” and those who answered yes were considered to have PSA. The survey included questions about sexual behaviors and birth control use, health care utilization, genitourinary (GU) symptoms, and demographics. In addition, we utilized electronic health records to assess prior use of our ED and hospital-based adolescent clinic.

Following CDC and Healthy People 2020 guidelines, we defined the following as high-risk: first sex before age 15, no condom at last sex, substance use before last sex, >3 partners in past 3 months, and >4 lifetime partners.16,18 The responses to, “What is the main reason for the visit today?” were dichotomized as potentially reproductive (genital-urinary complaints, abdominal pain, pregnancy/STI concern, or female with vomiting) or non-reproductive complaints.

Study Protocol

Trained research assistants (RAs) identified potential subjects through the ED computerized tracking board, which logged information (including chief complaint, as documented by triage nurse) in real time. The RA determined whether the patient met inclusion criteria then asked the ED provider about recruitment suitability. The RA briefly introduced the study to potential subjects and parents and obtained verbal parental permission to talk privately with the adolescent (who would independently consider participation). The RA privately obtained written adolescent assent/consent, verbally administered the survey, and instructed the subject to provide a first-void urine specimen without genital cleaning.

Specimen testing and subject treatment

Two milliliters of urine were packaged into an APTIMA transfer tube, labeled, and stored in a laboratory refrigerator. The samples were tested in batches every two to three weeks and results were recorded into a study log. One investigator (MM) was responsible for reviewing the log, identifying and writing orders for subjects who needed treatment, and notifying the designated treatment nurse in adolescent clinic. The nurse followed clinic protocol for calling positive subjects and arranging treatment.

For all three pathogens, the nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) was performed with Aptima assays (Gen-Probe Inc., San Diego, CA). For females, the sensitivity for CT, GC, and TV is 95%, 92% and 95% respectively; specificity for each is 99%. 19 For males, the sensitivity for CT and GC is 98% and 99% respectively; specificity is 99% and 100% (no information provided for TV).19 For this study, the NAAT for male urine specimens was used off-label after laboratory validation. One study of 298 men reported sensitivity for TV was 74% and specificity was 98%.20

Sample size and data analysis

From previous work, we assumed 50% of our population would report PSA.4,5 Using an estimated combined STI rate of 10%, a sample size of 200 (100 with PSA) provided a 95% Confidence Interval (CI) around the prevalence point estimate of 4–16%, using an alpha = 0.05. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic variables. The primary outcome was prevalence of CT, GC, and/or TV. Comparisons of responses between subgroups were analyzed using Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test in cases of small sample. Factors examined for association with STI included age, race, insurance, reason for ED visit, symptomatology, sexual health behaviors, and health care utilization. Data entry and analysis was done with SPSS for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).21

RESULTS

Subjects were enrolled from February 20–July 20, 2012. Of the 314 patients approached, 204 agreed to participate (65%) and 200 produced a urine specimen (98%). For 22 patients, a parent refused participation on their behalf. Most (81%) of the patients who refused cited lack of desire to participate, fatigue, or acute illness. Participants and non-participants did not differ in regard to race or age. Subject characteristics are described in Table 1. The majority (74%) were aged 14–16 years. Most visits (75%) were for non-reproductive complaints and more females than males had a reproductive complaint (28% vs. 12%, p= 0.08). One quarter reported GU symptoms, which were more frequent among females than males (34% vs. 8%, p≤0.001).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Characteristic | All | With PSA | No PSA | With STI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=200) N (%) |

(N=99) N (%) |

(N=101) N (%) |

(N=11) N (%) |

|

| Age, mean (SD), year | 15.6 ± 1.2 | 16.2 ± 1.2 | 15.2 ± 1.1 | 16.3 ± 1.1 |

| Female | 127 (63) | 60 (60) | 67 (67) | 7 (64) |

| Currently in school | 184 (92) | 86 (86) | 98 (97) | 10 (91) |

| Hispanic Ethnicity | 28 (14) | 12 (12) | 16 (16) | 2 (18) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 79 (40) | 34 (34) | 45 (45) | 2 (18) |

| Black | 86 (43) | 51 (51) | 35 (35) | 7 (64) |

| Mixed Race/other | 35 (17) | 14 (14) | 21 (21) | 2 (18) |

| Insurance* | ||||

| Private | 56 (27) | 18 (18) | 38 (38) | 3 (27) |

| Government | 112 (56) | 66 (66) | 46 (46) | 6 (55) |

| Self pay | 24 (12) | 11 (11) | 13 (13) | 2 (18) |

| Combination/other | 8 (4) | 4 (4) | 4 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Previous Sexual Activity (PSA) | 99 (50) | 99 (100) | 0 (0) | 10 (90)# |

| Reproductive visit** | 45 (22) | 26 (26) | 19 (19) | 2 (18) |

| Reported genitourinary symptoms | 49 (25) | 30 (30) | 19 (19) | 1 (10) |

| No reliable birth control at last sex | 23 (11.5) | 23 (23) | N/A | 2 (18) |

| Emergency department visit in past year | 77 (39) | 44 (44) | 33 (33) | 7 (64) |

| Adolescent Clinic visit in past year | 53 (27) | 25 (25) | 28 (28) | 5 (46) |

Data missing for 1 subject;

Reproductive visits included those subjects with genital-urinary complaints, abdominal pain, pregnancy/STI concern, or female with vomiting;

Subjects reporting PSA compared to reporting no PSA had increased likelihood of an STI (10% vs. 1%, p=0.005)

Prevalence of Sexually Transmitted Infections

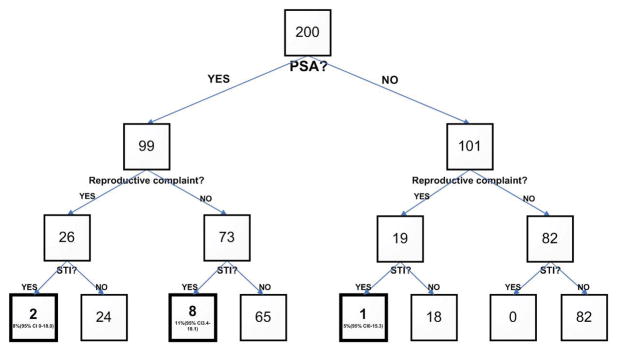

Eleven subjects (5.5%; 95% CI 2.3–8.7) tested positive for ≥1 STI: 10 (5%) for CT, 3 (2%) for TV, and 1 (<1%) for GC. All 3 subjects with TV (all females) were co-infected with CT. One subject who denied PSA was positive for CT. Among those seeking care for a non-reproductive complaint, the prevalence of ≥1 STI was 5.8% (95% CI 2.1–9.5). Among those reporting PSA, the prevalence of ≥1 STI was 10.1% (95% CI 4.2–16.0) and among those with PSA and non-reproductive complaint, the prevalence of ≥1 STI was 11.0% (95% CI 3.4–18.1). (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1.

Sexually transmitted infection prevalence among subjects by Previous Sexual Activity and Emergency Department visit type

Among the 11 subjects who had an STI, two were also tested for STIs as part of their ED care and, of these, one was treated empirically during the ED visit and one was lost to follow-up. The nine other positive subjects who were tested solely due to this study were contacted by phone, referred and treated at the hospital-affiliated adolescent clinic.

Two factors were associated with increased likelihood of having ≥1 STI: reporting PSA compared to reporting no PSA (10% vs. 1%, p=0.005) and, among those with PSA, reporting last sex within one month compared to greater than one month (20% vs. 0%, p=0.001) (see Tables 1 and 2). The association between having an STI and being older (16–19 years) rather than younger (14–15 years) neared significance (9% vs. 2%, p=0.06). The following factors were not associated with increased likelihood of ≥1 STI: race (non-white vs. white), insurance status (commercial vs. other), presence of GU symptoms, previous ED or adolescent clinic visit, or reason for ED visit (reproductive vs. other) or high-risk behavior (any vs. none).

Table 2.

Time from most recent vaginal or anal sex to emergency department visit, reported by adolescents with previous sexual activity (PSA)

| Time from sex to visit | All subjects with PSA (N=99) N (%) |

Subjects with PSA and STI* (N=10) N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| ≤ 7 days | 25 (25) | 6 (55) |

| 8 days – 1 month | 26 (26) | 4 (36) |

| > 1 month – 2 months | 17 (17) | 0 |

| > 2 months – 3 months | 8 (8) | 0 |

| > 3 months – 6 months | 12 (12) | 0 |

| > 6 months – 1 year | 7 (7) | 0 |

| > 1 year | 4 (4) | 0 |

Abbreviations: Previous Sexual Activity (PSA), Sexually Transmitted Infection (STI)

1 subject with an STI denied PSA

Sexual Health behaviors

Half of participants (50%) reported PSA. The proportion with PSA varied by age: 30% of those aged 14–15 years, 65% of those 16–17 years, and 81% of those aged 18–19 years. A few subjects reported homosexual (1 female) or bisexual (3 females) activity. While nearly all adolescents (94%) felt it was “very” important to avoid pregnancy right now, among adolescents with PSA 23% reported that no reliable method was used to prevent pregnancy at last sex (by answering “not sure,” “none,” or “withdrawal”) and 8% reported unprotected vaginal intercourse within the previous seven days.

Among participants with PSA, 71% reported ≥1 high-risk behavior, most commonly sexual debut before age 15 years and no condom at last sex (Table 3). Among participants with a high-risk behavior, 34% had one high-risk behavior, 18% had two, 16% had three, and 2% reported four. Recent sexual activity was common, especially among those with ≥1 STI (Table 2). The number of lifetime episodes of vaginal or anal sex varied widely: 43% had 1–9, 20% had 10–19, 19% had 20–49, and 15% had ≥ 50.

Table 3.

High-risk behaviors among adolescents with previous sexual activity (N=99)

| Risk Factor | (N=99) N (%) |

|---|---|

| Sexual debut <15 years | 51 (51) |

| > 4 lifetime partners | 23 (23) |

| > 3 partners in past 3 months | 1 (1) |

| Alcohol/drug use within 4 hours of last sex | 10 (10) |

| No condom during last sex | 42 (42) |

Health care utilization

Among all subjects, 39% had ≥1 previous ED visit and 27% had visited the adolescent clinic. Almost half (45%) reported they visited an ED the last time they needed care and 32% lacked a recent health check-up (“>1 year”/“can’t remember”). Compared to those with commercial insurance, adolescents without commercial insurance were more likely to have visited the ED (43% vs. 22%, p=0.03) and adolescent clinic (32% vs. 12%, p=0.005) in the previous year. Females were more likely than males to lack a recent heath check-up (41% vs. 16%, p≤0.001). Adolescents with PSA tended to be more likely to lack a recent health check-up compared to those without PSA, but this was not statistically significant (39% vs. 26%, p=0.06).

Subjects with PSA more commonly reported prior health visits for STI evaluation (35% vs. 8%, p≤0.001) and for birth control/condoms (50% vs. 24%, p≤0.001) compared to those without PSA. Sexually active subjects with ≥1 high-risk behavior were no more likely to report prior visits for STI evaluation (40% vs. 25%, p=0.2) nor for birth control/condoms (52% vs. 46%, p=0.7) when compared to those without high-risk behaviors. When compared to subjects that did not have an STI, subjects with an STI more commonly reported prior visits for STI evaluation (46% vs. 20%, p≤0.05), but not for birth control/condoms (55% vs. 35%, p=0.2).

Many subjects reported barriers to accessing sexual health care. The majority were “very” or “somewhat” worried about transportation (57%), privacy (60%), and cost (67%). There was no difference in reporting prior visits for STI evaluation or birth control/condoms for subjects worried about transportation, privacy, or cost compared to those not worried. Further, there were no associations between worry about transportation, privacy, or cost with gender, race (white vs. other), PSA, insurance (private vs. other), testing positive for ≥1 study STI, or age (14–15 vs. 16–19).

DISCUSSION

We found a considerable burden of infection with CT, GC, and TV among adolescents presenting to a Midwestern pediatric ED in 2012. Overall, 6% of subjects tested positive for ≥1 STI, and prevalence increased to 10% among those reporting PSA. Many adolescents reported recent sexual intercourse, which was associated with an increased likelihood of testing positive for ≥ 1 STI. While this sample was small, we found no associations between STI and insurance, race, high-risk behaviors, age, or ED visit reason.

Among adolescents and young adults, black race has been associated with greater likelihood of STI in several large, national studies.22–24 Interestingly, we did not find this association between race and STI, though our sample was small. Other ED studies conducted with adolescents and young adults have found mixed results regarding associations between STI and race, age or insurance status.12, 14, 15, 25 Variations in study setting, population characteristics, and sample size may contribute to these different findings.

While we did not find associations between individual risk behaviors and STI, several studies have made this link for behaviors such as younger age for sexual debut and higher number of lifetime partners. 22, 26–28 Further, the literature suggests that racial differences in STI prevalence cannot be fully explained by individual risk behaviors, and instead there may be social, environmental, and/or population-level determinants that contribute to sexual health disparities. 22–23

Goyal et al. recently found no association between TV and concurrent CT among symptomatic adolescent females in the ED.15 However, many studies do demonstrate an association between these pathogens, which is consistent with our findings.10,29 It is important for providers to consider co-infection, as it can result in increased morbidity including increased susceptibility to HIV acquisition. 30

To improve STI control efforts, proactive screening and outreach for adolescents who might not otherwise seek reproductive care are needed. Our finding that 1 in 10 sexually active adolescents presenting to this ED without reproductive complaints had at least one STI provides support for focusing STI control efforts in this setting. Further, we were successful in contacting and treating all but one subject who had an STI, providing evidence of feasibility for screening in this setting.

We did not use absence of PSA as an exclusion criterion, as previous studies have shown sexual histories to be unreliable. Di Clemente et al. found that among those with an STI, 6% reported lifetime abstinence and 10% reported no sex in the previous 12 months.31 In our small study we found a single STI-positive subject who denied PSA and all of the other STI-positive subjects reported very recent sex (within one month). Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for STI when treating adolescents regardless of chief complaint and/or self-reported abstinence.

Increased awareness of non-invasive collection techniques may improve both the likelihood of providers to test and of test acceptance by adolescents. A particular strength of this study was the use of urine NAAT to test for TV, which has rarely been utilized to study prevalence. Standard testing for TV (culture and wet mount) has involved invasive methods that resulted in suboptimal sensitivity. 10–11, 32 Among females, vaginal specimens for NAAT have been proven most sensitive; however, even urine specimens are more sensitive than wet mount or culture.20 Several studies suggest that NAAT (using any specimen) is the most sensitive test to detect TV in asymptomatic females.10,20 For males, although urine specimens for NAAT are more sensitive than culture, the use of urine over urethral specimens has not yet been recommended.20 While the diagnostic accuracy for NAAT may be highest with invasive testing methods, urine specimens for NAAT still produce improved accuracy over standard methods and may be warranted given the preference for this method among sexually active adolescents.33

Our findings indicate adolescent ED users may benefit from targeted sexual health education efforts. While the majority of sexually active adolescents engaged in high-risk behaviors, only half had obtained care for birth control/condoms and fewer for STI evaluation. Although almost all of the adolescents reported wanting to prevent pregnancy, among sexually active heterosexuals, 23% reported no method used to prevent pregnancy at last sex.

Limitations

This study was conducted at a single, urban pediatric ED, which limits generalizability. Our ability to identify factors associated with STI was limited due to the small number of subjects with ≥1 STI, thus some of the comparisons may have been prone to a type II error and more complex analyses (i.e., logistic regression) were not suitable. About 35% of eligible adolescents declined participation and we do not know the STI prevalence among non-participants or those presenting during non-recruitment times. Responses about sexual history were provided by self-report, which could be influenced by social desirability effects or concerns about confidentiality.

CONCLUSION

About 1 in 10 sexually active adolescents presenting without reproductive complaints to this urban ED had at least one STI. Due to high prevalence of risk behaviors, ED practitioners caring for adolescents should obtain a thorough sexual history. These data suggest the need for strategies to increase STI testing for this population, and further evaluation (including cost and feasibility) of STI testing for this population may be warranted.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Frontiers: The Heartland Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (University of Kansas Medical Center’s CTSA; KL2TR000119-02). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, NCRR, or NCATS.

The authors acknowledge Stephen Simon PhD for his statistical assistance with this project and thank Drs. Patricia Kelly, Kathy Goggin, and Timothy Apodaca for their contributions to the larger project which also incorporates this study.

Abbreviations

- CT

Chlamydia trachomatis

- CI

Confidence Interval

- ED

emergency department

- GU

genitourinary

- GC

Neisseria gonorrheae

- NAAT

nucleic acid amplification test

- PSA

previous sexual activity

- RA

research assistant

- STI

sexually transmitted infection

- TV

Trichomonas vaginalis

Footnotes

The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed on April 1, 2013];Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2011 at http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats11/adol.htm.

- 2.Walton MA, Resko S, Whiteside L, Chermack ST, Zimmerman M, Cunningham RM. Sexual Risk Behaviors Among Teens at an Urban Emergency Department: Relationship With Violent Behaviors and Substance Use. J Adol Health. 2011;48:303–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fine LC, Mollen CJ. A Pilot Study to Assess Candidacy for Emergency Contraception and Interest in Sexual Health Education. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26(6):413–416. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181e0578f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mollen CJ, Miller MK, Hayes KL, Barg FK. Knowledge and Beliefs about Emergency Contraception among Adolescents in the Emergency Department. Ped Emerg Care. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31828a3249. (In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller MK, Pickett ML, Leisner KL, Humiston SG. Sexual Health Behaviors and Use of Health Services among Adolescents in an Emergency Department. Ped Emerg Care. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31829ec244. (In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goyal M, McCutcheon M, Hayes K, Mollen CJ. Sexual History Documentation in Adolescent Emergency Department Patients. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):86–91. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ziv A, Boulet JR, Slap GB. Emergency department utilization by US adolescents. Pediatrics. 1998;101:987–94. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.6.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller MK, Dowd MD, Plantz DM, et al. Pediatric Emergency Medicine Health Care Providers’ Knowledge, Attitudes and Experiences Regarding Emergency Contraception. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(6):605–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hock-Long L, Herceg-Baron R, Cassidy AM. Access to Adolescent Reproductive Health Services: Financial and Structural Barriers to Care. Perspec Sexual Reproduc Health. 2003;35(3):144–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huppert JS, Mortensen JE, Reed JL, et al. Rapid antigen testing compares favorably with transcription-mediated amplification assay for the detection of Trichomonas vaginalis in young women. Clin Infect Di. 2007;45:194–198. doi: 10.1086/518851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radonjic IV, Dzamic AM, Mitrovic SM, et al. Diagnosis of Trichomonas vaginalis infection: the sensitivities and specificities of microscopy, culture and PCR assay. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;126:116–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silva A, Glick NR, Lyss SB, et al. Implementing an HIV and Sexually Transmitted Disease Screening Program in an Emergency Department. Ann of Emerg Med. 2007;49(5):564–572. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monroe KW, Weiss HL, Jones M, et al. Acceptability of Urine Screening for Neisseria gonorrheae and Chlamydia trachomatis in Adolescents at an Urban Emergency Department. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2003;30(11):850–853. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000086600.71690.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehta SD, Hall J, Lyss SB, Skolnik PR, Pealer LN, Kharasch S. Adult and Pediatric Emergency Department Sexually Transmitted Disease and HIV Screening: Programmatic Overview and Outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(3):250–258. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.10.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goyal M, Hayes K, McGowan K, et al. Prevalence of Trichomonas Vaginalis in symptomatic adolescent females presenting to an urban pediatric emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:763–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed on December 20, 2011];Youth Risk Behavior Survey. 2009 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/yrbs.

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed on September 18, 2012];National Survey of Family Growth. 2010 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg.htm.

- 18.Healthy People 2020. US Department of HHS; [Accessed September 18, 2012]. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/ [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aptima Combo 2 Assay [package insert] San Diego, CA: Gen-Probe; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nye MB, Schwebke JR, Body BA. Comparison of APTIMA Trichomonas vaginalis transcription-mediated amplification to wet mount microscopy, culture, and polymerase chain reaction for diagnosis of trichomoniasis in men and women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:188.e1–188.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.SPSS Statistics for Windows. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc; 2008. Version 18.0. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forhan SE, Gottlieb SL, Sternberg MR, et al. Prevalence of Sexually Transmitted Infections Among Female Adolescents Aged 14 to 19 in the United States. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):1505–1512. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hallfors DD, Iritani BJ, Miller WC, Bauer DJ. Sexual and Drug Behavior Patterns and HIV and STD Racial Disparities: The Need for New Directions. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):126–132. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.075747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller WC, Ford CJ, Morris M, et al. Prevalence of Chlamydial and Gonococcal Infections Among Young Adults in the United States. JAMA. 2004;291(18):2229–2236. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.18.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goyal M, Hayes K, Mollen CJ. Sexually Transmitted Infection Prevalence in Symptomatic Adolescent Emergency Department Patients. Ped Emerg Care. 2012;28(12):1277–1280. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182767d7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaestle CE, Halpern CT, Miller WC, Ford CA. Young age at first sexual intercourse and sexually transmitted infections in adolescents and young adults. Am J Epidemiology. 2005;161(8):774–780. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coker AL, Richter DL, Valois RF, McKeown RE, Garrison CZ, Vincent ML. Correlates and consequences of early initiation of sexual intercourse. J School Health. 1994;64(9):372–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1994.tb06208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jenkins WD, Kovach R, Wold BJ, Zahnd WE. Using Patient-Provided Information to Refine Sexually Transmitted Infection Screening Criteria Among Women Presenting in the Emergency Department. Sex Trans Diseases. 2012;39(12):965–67. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31826e882f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McClelland SR, Sangare L, Hassan WM, Lavreys L, Mandaliya K, Kiarie J, Ndinya-Achola J, Jaoko W, Baeten JM. Infection with Trichomonas vaginalis Increases the Risk of HIV-1 Acquisition. J Infect Diseases. 2007;195:698–702. doi: 10.1086/511278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trichomoniasis: clinical manifestations, diagnosis and management. Swygard H, Sena AC, Hobbs MM, Cohen MS. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80:91–95. doi: 10.1136/sti.2003.005124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DiClemente RJ, Sales JM, Danner F, et al. Association Between Sexually Transmitted Diseases and Young Adults’ Self-reported Abstinence. Pediatrics. 2011;127(2):208–13. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wendel KA, Erbelding EJ, Gaydos CA, Rompalo AM. Trichomonas vaginalis polymerase chain reaction compared with standard diagnostic and therapeutic protocols for detection and treatment of vaginal trichomoniasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35(5):576–580. doi: 10.1086/342060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Serlin M, Shafer M, Tebb K, Gyamfi A, Moncada J, Schachter J, Wibblesman C. What Sexually Transmitted Disease Screening Method Does the Adolescent Prefer? Arch Pediatr Adol Med. 2002;156:588–591. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.6.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]