Abstract

Background

Living donor kidney transplant (LDKT) can be impeded by multiple barriers. One possible barrier to LDKT is a large physical distance between the living donor's home residence and the procuring transplant center.

Methods

We performed a retrospective, single-center study of U.S. living kidney donors who were geographically distant (residing ≥150 miles) from our transplant center. Each distant donor was matched to four geographically nearby donors (<150 miles from our center) as controls.

Results

From 2007-2010, of 429 live kidney donors, 55 (12.8%) were geographically distant. Blacks comprised a higher proportion of geographically distant vs. nearby donors (34.6% vs. 15.5%), while Hispanics and Asians comprised a lower proportion (P=0.001). Distant vs. nearby donors had similar median times from donor referral to actual donation (165 vs. 161 days, P=0.81). The geographically distant donors lived a median of 703 miles (25%-75% range 244-1072) from our center and 21.2 miles (25%-75% range, 9.8-49.7) from the nearest kidney transplant center. The proportion of geographically distant donors who had their physician evaluation (21.6%), psychosocial evaluation (21.6%), or CT angiogram (29.4%) performed close to home, rather than at our center, was low.

Conclusions

Many geographically distant donors live close to transplant centers other than the procuring transplant center, but few of these donors perform parts of their donor evaluation at these closer centers. Blacks comprise a large proportion of geographically distant donors. The evaluation of geographically distant donors, especially among minorities, warrants further study.

Keywords: Kidney transplant, living donor, geography, evaluation

Introduction

Living donor kidney transplant (LDKT) is considered the optimal treatment for end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Since peaking in 2004, however, the annual number of LDKTs in the United States has decreased [1]. This decrease has been attributed to numerous factors, including the growing prevalence of comorbidities in the general population that preclude living donation, use of stricter and different eligibility criteria for certain groups of donor candidates (e.g. Blacks), and financial disincentives to living donation due to donation's out-of-pocket costs [2]. The Best Practices in Living Kidney Donation Consensus Conference in June 2014 recommended that to increase the number of LDKTs, the transplant community should aim to improve efficiencies in the donor evaluation process and reduce systemic barriers to LDKT [3].

One possible barrier to LDKT and living kidney donation is the physical distance between the living kidney donor's home residence and the transplant center where the donor nephrectomy will be performed. Prior studies of access to transplant have focused upon the distance of the ESRD patient, rather than the living donor, from the transplant center [4-6]. To our knowledge, prior studies have not examined the impact, if any, of distance between the living donor and the transplant center. Distance is a plausible barrier to LDKT, given that completion of the multi-step donor evaluation can require living donors to travel to a transplant center multiple times. Anecdotally, we have observed that living donors who reside a long distance from our center have had difficulty completing the donor evaluation. In addition, these geographically distant donors are seldom able to perform any of the needed evaluations at a transplant center closer to home.

In this retrospective study, we sought to determine (1) the proportion of living kidney donors at our center who are geographically distant from our center; (2) characteristics of geographically distant vs. geographically nearby living donors; and (3) the proportion of geographically distant donors who perform pre-donation testing and evaluations at a center closer to home.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

We performed a single-center, retrospective study of living kidney donors who donated at Saint Barnabas Medical Center (SBMC), a kidney and pancreas transplant center located in suburban Livingston, New Jersey, in the northeastern U.S. We included persons who donated from 2007-2010, during which SBMC performed 429 LDKTs. We excluded persons who donated after December 2010, because at that time we started a clinical trial of an educational intervention designed to increase knowledge of LDKT among potential transplant candidates [7].

The study protocol was approved by the human subjects Institutional Review Boards at SBMC and New York University School of Medicine. The clinical and research activities being reported are consistent with the Principles of the Declaration of Istanbul as outlined in the Declaration of Istanbul on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism.

Selection of geographically distant vs. nearby living donors

We classified living kidney donors as geographically distant if they lived within the U.S. (including its territories) but ≥150 miles from our transplant center. The 150-mile cutoff, which represents at least a 2.5 hour drive, was chosen a priori. This distance has been used in prior studies to categorize transplant candidates as living “too far” from a transplant center to be expected to return easily [8, 9].

For comparison, we matched each geographically distant donor to four “control” donors who were geographically nearby, which was defined as residing <150 miles from our transplant center. These controls were the two geographically nearby donors whose donor nephrectomies occurred immediately before and the two nearby donors whose nephrectomies occurred immediately after each geographically distant donor. We chose controls in this way to account for the influence of any subtle changes during the study period in how we perform the donor evaluation. We did not match controls to the geographically distant donors using variables (e.g. age, race sex) other than date of donation. Matching on other variables would have prevented estimation of any associations between these other matching variables and the outcome (geographically distant donation) [10].

We excluded donors who resided outside the U.S. We also excluded non-directed living donors, defined as donors without an intended recipient on the waiting list at SBMC when they initially volunteered. At our center, the evaluation of non-directed donors differs from the evaluation of directed donors and includes additional psychosocial evaluations.

We calculated the Euclidean distance between the centroid of each donor's ZIP code and the geocoded addresses of (1) SBMC, and (2) each approved transplant center that performs LDKTs (to determine the closest transplant center). We used the centroid of the donor's ZIP code due to privacy concerns that precluded sharing the donors’ actual addresses with our collaborator (D.C.L.). ZIP code centroids were obtained from a shapefile available from the Environmental Systems Research Institute [11]. We used data from Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to identify Medicare-approved kidney transplant programs and their addresses [12] and data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients to identify transplant centers that performed LDKTs [13]. Distances between these centroids and the geocoded location of transplant centers were calculated in ArcGIS 10.2 (Environmental Systems Research Institute: Redlands, CA; 2013). The living donor's ZIP code was also linked to the median household income for the corresponding ZIP code tabulation area (ZCTA), according to 2007-2011 U.S. Census Bureau data.

Data collection and analysis

For each geographically distant and geographically nearby donor, we reviewed their electronic records and, if available, paper medical records. We have previously described our evaluation of living kidney donors [14, 15]. We determined the initial date of donor referral, defined as the date that our center received a completed donor referral form. For donors with complete records available, we also determined where (at SBMC vs. another center) the donors completed the nursing assessment and education; evaluation by a transplant physician; psychosocial evaluation; CT angiogram of the native kidneys; and evaluation by an independent living donor advocate.

Categorical variables were expressed as proportions, and their values between groups (geographically distant vs. nearby) were compared using chi-square testing or Fisher's exact test where appropriate. Continuous variables were expressed as means (if normally distributed) or as medians with 25%-75% interquartile ranges (if not normally distributed) and compared using t-tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests as appropriate. P-values are 2-sided, with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05. Analyses were performed using Stata SE 9 statistical software (Stata Corp: College Station, Texas).

Results

Of 429 living donors during the study period, 55 (12.8%) were geographically distant. We were able to locate the paper records for 51 (92.7%) of these geographically distant donors and for 214 of 220 of the matched controls (97.3%, P=0.11).

Characteristics of geographically distant vs. geographically nearby donors

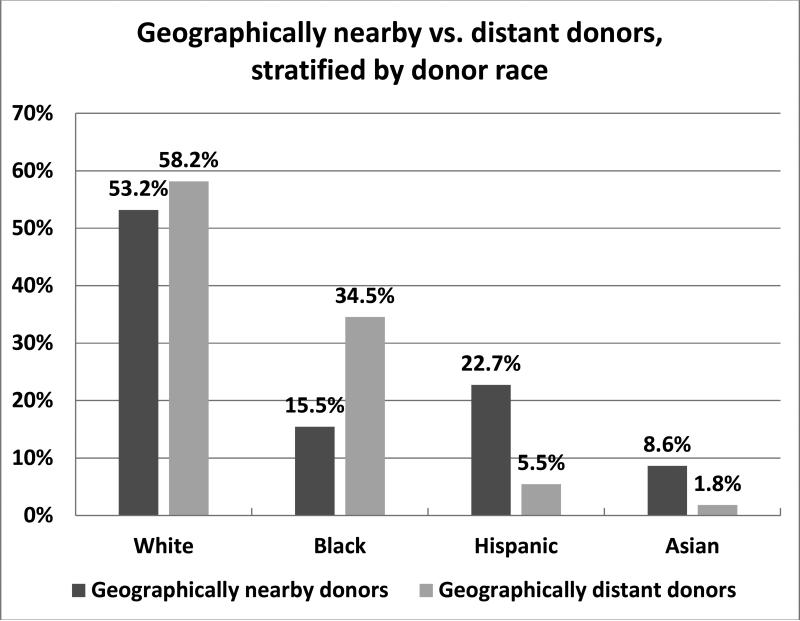

Table 1 describes the characteristics of the 55 geographically distant donors compared to the 220 control, geographically nearby donors. Donors who were geographically distant, versus geographically nearby, were significantly more likely to be the sibling or child of the recipient. Blacks comprised a significantly higher percentage of geographically distant living donors compared to nearby donors (34.6% vs. 15.5%, P=0.001). Hispanics (5.5% vs. 22.7%) and Asians (1.8% vs. 8.6%), however, comprised a lower percentage of geographically distant (vs. nearby) donors (Table 1 and Figure). To ensure that these results were not on artifact of our sampling of controls (the nearby donors), we examined the race of all 374 non-distant donors from whom we selected the 220 controls. The percentages of Blacks (14.7%), Hispanics (21.9%), and Asians (7.0%) among those 374 donors were nearly identical to their percentages among the 220 donors selected and verified as geographically nearby controls (15.5% for Blacks, 22.7% for Hispanics, and 8.6% for Asians).

Table 1.

Characteristics of geographically distant and geographically nearby living kidney donors

| Geographically distant living donors | Geographically nearby living donors | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 55 | 220 | |

| Male | 26 (47.3%) | 87 (36.8%) | 0.16 |

| Median age (25%-75%) | 45.9 (40.3-52.1) | 42.3 (32.0-51.4) | 0.04 |

| Relationship of donor to recipient | 0.001 | ||

| Sibling | 27 (49.0%) | 57 (25.9%) | |

| Spouse | 0 | 49 (22.3%) | |

| Child | 15 (27.3%) | 43 (19.6%) | |

| Parent | 1 (1.8%) | 23 (10.5%) | |

| Other biological relative | 4 (7.3%) | 10 (4.6%) | |

| Other non-related | 8 (14.6%) | 38 (17.3%) | |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | ||

| White | 32 (58.2%) | 117 (53.2%) | |

| Black | 19 (34.5%) | 34 (15.5%) | |

| Hispanic | 3 (5.5%) | 50 (22.7%) | |

| Asian | 1 (1.8%) | 19 (8.6%) | |

| Married, N (%) | 28 (50.9%) | 128 (58.2%) | 0.33 |

| Highest education level | 0.28 | ||

| High school graduate or less | 15 (27.3%) | 62 (28.2%) | |

| Some college | 20 (36.4%) | 66 (30.0%) | |

| College degree or above | 11 (20.0%) | 69 (31.4%) | |

| Unknown | 9 (16.4%) | 23 (10.5%) | |

| Median income of zip code | $56,479 | $75,472 | 0.0002 |

| Median body mass index (25%-75%) | 27.5 (24.8-29.8) | 26.6 (23.4-29.9) | 0.17 |

| Median days from referral to actual donation (25%-75%) | 165 (96-299) | 161 (101-286) | 0.81 |

| Participated in paired exchange (%) | 0 | 10 (4.6%) | 0.11 |

| Number of other potential living donors identified and recruited by recipients | 0.92 | ||

| 0 | 27 (49.1%) | 110 (50.0%) | |

| 1 | 15 (27.3%) | 56 (25.5%) | |

| 2 | 7 (12.7%) | 30 (13.6%) | |

| 3 | 2 (3.6%) | 11 (5.0%) | |

| 4 | 3 (5.5%) | 10 (4.6%) | |

| 5 | 0 | 2 (0.9%) | |

| 6 | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (0.5%) |

Figure.

Geographically nearby vs. distant donors, stratified by donor race.

Living kidney donors who were geographically distant, vs. nearby, resided in ZCTAs with lower median household incomes (P=0.0002) (Table 1). Black donors resided in ZCTAs with lower median household incomes than non-Black donors ($47,999 vs. $74,838, P<0.0001). Among the Black living donors, there were no differences in median household incomes by ZCTA among geographically distant vs. nearby donors ($50,115 and $47,262 respectively, P=0.78). Among geographically distant donors, there were no statistically significant differences in median household incomes by ZCTA for Blacks vs. non-Blacks ($50,115 vs. $58,747; P=0.13).

Time from donor referral to actual donation was not different between geographically distant and nearby donors (median of 165 vs. 161 days, P=0.81). No geographically distant donors (0/55, 0%) participated in a paired exchange, compared to a small proportion of geographically nearby donors (10/220, 4.5%) (P=0.22).

Similar percentages of the geographically distant donors (49.1%) and nearby donors (50.0%) were the only potential living donors identified or recruited by their recipients (Table 1). The LDKT recipients recruited a median of one other potential living donor (25%-75% range 0-1). There was no difference in the number of other donors recruited by the recipients whose actual living donors were nearby vs. distant (P=0.95).

The 55 geographically distant donors lived a median of 703 miles (25%-75% range 244-1072) from SBMC. These geographically distant donors lived a median of 21.2 miles (25%-75% range, 9.8-49.7) from the nearest kidney transplant center.

Evaluation of geographically distant vs. geographically nearby donors

We further examined the subset of 51 geographically distant donors and 214 nearby donors whose full donor evaluation records were available, to compare the proportion of pre-donation workup that was completed at our center vs. another transplant center (Table 2). The percentages of distant living donors who had their physician evaluation, psychosocial evaluation, or CT angiogram performed close to home, were 21.6%, 21.6%, and 29.4%, respectively. These percentages were higher than the percentages of geographically nearby donors who had their evaluations performed at a center other than SBMC. Only 2 of 51 (3.9%) geographically distant donors received assistance from the National Living Donor Assistance Center.

Table 2.

Location of initial evaluation of geographically distant and geographically nearby living kidney donors*

| Geographically distant living donors | Geographically nearby living donors | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 51 | 214 | |

| Nursing education and assessment at other transplant center | 0 (0%) of 49 | 1 of 210 (0.5%) | 0.99 |

| Nephrologist evaluation at other transplant center | 11 (21.6%) | 3 (1.4%) | <0.001 |

| Psychosocial evaluation at other transplant center | 11 (21.6%) | 0 (0%) of 213 | <0.001 |

| ILDA evaluation at other transplant center | 4 (7.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0.001 |

| CT angiogram at other transplant center | 15 (29.4%) | 6 (2.8%) of 212 | <0.001 |

among 265 of 275 living donors in study whose charts were located

Discussion

In this single center, retrospective study, we found that geographically distant donors comprised 12.8% of our living kidney donors. Geographically distant (vs. nearby) donors were more likely to be Black (34.6% vs. 15.5%) and less likely to be Hispanic or Asian (P=0.001). Most geographically distant donors lived close to another transplant center, but less than one-third of geographically distant donors had their physician evaluation, psychosocial evaluation, or CT angiogram performed at a transplant center close to where they lived. Despite having to travel to our center, geographically distant donors did not require more time than nearby donors to complete the donor evaluation and donation process.

An unexpected finding in our study was that Blacks comprised a higher proportion of geographically distant (vs. nearby) donors. A possible explanation for the higher proportion of geographically distant donors who were Black is that Black transplant candidates may lack willing and medically suitable donor volunteers who live nearby. Prior studies have documented that potential living kidney donors who are Black are more likely to be medically unsuitable to donate and less likely to complete the evaluation process [14, 16]. Black transplant candidates, who may lack suitable and willing donors who live nearby, may need to rely upon geographically distant family and friends to donate. Given the persistently low rate of LDKT among Black transplant candidates [17], our findings should be confirmed in future studies. To reduce disparities in LDKT among Blacks, efforts to reduce the socioeconomic burden of live donation (e.g. use of the National Living Donor Assistance Center) may need to be supplemented by efforts to reduce the geographic barriers to live donation.

A minority of our living kidney donors performed portions of their pre-donation testing and evaluations at a geographically closer transplant center. This finding is consistent with our anecdotal experience. Transplant centers may be able to increase donor convenience by arranging for geographically distant living donors to perform their evaluations at a center closer to the donors’ home residences. Transplant centers would need to mutually agree to test and evaluate potential living donors who intend to donate at other, geographically distant centers. To help geographically distant donors, transplant centers can also try to minimize the amount of travel required by living donors during the evaluation process, while still maintaining the thoroughness of the donor evaluation.

Addressing geographical barriers to living donation could plausibly lead to increased LDKT. Given the decade-long national decline in the number of LDKTs, most would agree that kidney transplant centers should strive to minimize any impact of geography upon the likelihood of donation. Cooperation between transplant centers in the evaluation of geographically distant donors could plausibly expand the pool of living donors. Given the lower proportion of geographically distant donors who were Hispanic or Asian, such cooperation may especially facilitate donation among Hispanics and Asians as well as Blacks. In our study, however, the time to donation was similar between geographically nearby and geographically distant donors.

Our study should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, our study only examined persons who actually donated a kidney. Therefore, we could not determine if geographically distant potential donors are less likely to donate. Only a minority of potential living kidney donors actually donate, and the reasons for non-donation are numerous [14]. The proportion of potential living kidney donors who “drop out” of the donation process for non-medical reasons varies widely between centers [16, 18-21]. It is plausible that for donors who are geographically distant, versus nearby, the inconvenience and cost of travelling a long distance to perform the pre-donation evaluations and testing may lead to lower rates of actual donation and higher rates of donor “drop out”. Future studies should examine potential living donors, rather than actual living donors, to determine whether proximity to the transplant center impacts the likelihood of actual donation.

Second, this is a single-center study at a large transplant center in the northeastern U.S. Residents of our state (New Jersey) are served by a large number of nearby transplant centers [6]. Therefore, our results may not necessarily be applicable to other transplant centers, especially those located in areas that are either less densely populated or served by fewer transplant centers. It is possible that geographically distant donors who donate at other transplant centers may have different characteristics than the geographically distant donors in our study. Future studies can determine whether differences (and similarities) in geographically distant vs. nearby donors are also present at other centers.

Third, we defined a geographically distant donor as being located at least 150 miles away. There may be a better cutoff distance by which to define geographically distant donors, or distance may be qualitatively different for different types of donors. Individuals who live closer than 150 miles may still face significant geographic burdens in becoming a donor and also benefit from completing their workup at a closer facility.

Fourth, geographical distance may be a poor proxy for the burden of travel. Some geographically nearby donors have great difficulty in traveling to their nearby transplant center. Conversely, some geographically distant donors have little difficulty in traveling more than 150 miles to a transplant center. Our study, however, was not designed to quantify perceptions of travel burdens or actual travel costs, and we lacked data on actual travel times. In addition, geographically nearby donors who face difficulty in traveling to a nearby center may lack another center. Geographically distant donors with travel difficulties, however, usually have option, at least in theory, of completing part of their donor evaluation at a transplant center closer to home.

Fifth, to determine distances between each living donor and transplant centers, we used the centroid of ZIP codes and Euclidean distances. Small differences in distance may have led to misclassification of geographically distant donors for those observations in which distance between a donor's ZIP code and SBMC was close to our cutoff of 150 miles. However, for calculation of large distances, the imprecision of ZIP code centroids is usually marginal. Furthermore, over long distances the difference between Euclidean distance and actual travel distance is usually not as substantial, especially because geographically distant donors may be more likely to travel by air rather than car.

In conclusion, geographically distant donors were more likely than nearby donors to be Black. Geographically distant donors, however, were less likely to be Hispanic or Asian. Only a small minority of geographically distant donors were able to perform their donor evaluations locally, close to home. Given the persistent racial disparities in LDKT, this surprising finding warrants further investigation, both at other centers and using national registry databases.

Research highlights.

Many living kidney donors are geographically distant from the transplant center

Blacks comprised a higher proportion of geographically distant vs. nearby donors

Days from referral to actual donation were similar for distant vs. nearby donors

Few distant donors had their physician evaluation performed close to home

The evaluation of geographically distant donors warrants further study

Acknowledgements

Preliminary results from this manuscript were presented in May 2015 at the American Transplant Congress in Philadelphia, PA. F.L.W. and L.A.D are supported in part by grants R01DK098744 and R01MD007664 from the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- LDKT

living donor kidney transplant

- SBMC

Saint Barnabas Medical Center

- ZCTA

ZIP code tabulation area

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

David C. Lee, Email: David.Lee@nyumc.org.

Navdeep Dhillon, Email: ndhillon@barnabashealth.org.

Kim N. Tibaldi, Email: ktibaldi@barnabashealth.org.

LaShara A. Davis, Email: ldavis@barnabashealth.org.

Anup M. Patel, Email: apatel2@barnabashealth.org.

Ryan J. Goldberg, Email: rygoldberg@barnabashealth.org.

Marie Morgievich, Email: mmorgievich@barnabashealth.org.

Shamkant Mulgaonkar, Email: smulgaonkar@barnabashealth.org.

References

- 1.OPTN/SRTR 2012 Annual Data Report. Rockville; Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) and Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). p. MD2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodrigue JR, Schold JD, Mandelbrot DA. The decline in living kidney donation in the United States: random variation or cause for concern? Transplantation. 2013;96:767–73. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318298fa61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.LaPointe Rudow D, Hays R, Baliga P, Cohen DJ, Cooper M, Danovitch GM, et al. Consensus conference on best practices in live kidney donation: recommendations to optimize education, access, and care. American Journal of Transplantation. 2015;15:914–22. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Axelrod DA, Guidinger MK, Finlayson S, Schaubel DE, Goodman DC, Chobanian M, et al. Rates of solid-organ wait-listing, transplantation, and survival among residents of rural and urban areas. JAMA. 2008;299:202–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tonelli M, Klarenbach S, Rose C, Wiebe N, Gill J. Access to kidney transplantation among remote- and rural-dwelling patients with kidney failure in the United States. JAMA. 2009;301:1681–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasiske BL, Snyder JJ, Skeans MA, Tuomari AV, Maclean JR, Israni AK. The geography of kidney transplantation in the United States. American Journal of Transplantation. 2008;8:647–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.02130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weng FL, Brown DR, Peipert JD, Holland B, Waterman AD. Protocol of a cluster randomized trial of an educational intervention to increase knowledge of living donor kidney transplant among potential transplant candidates. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:256. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodrigue JR, Pavlakis M, Egbuna O, Paek M, Waterman AD, Mandelbrot DA. The “house calls” trial: a randomized controlled trial to reduce racial disparities in live donor kidney transplantation: rationale and design. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:811–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.St. Barnabas Medical Center . Increasing Kidney Transplant Among Blacks on the Transplant Waiting List. Vol. 2014. National Library of Medicine; Bethesda, MD: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woodward M. Epidemiology: study design and data analysis. Chapman & Hall/CRC; Boca Raton: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Environmental Systems Research Institute . USA Zip Code Points. Vol. 2015. Redlands; Mar 12, 2015. p. CA2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Medicare-Approved Transplant Programs. Vol. 2015. Baltimore, MD.: [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients . National Kidney Transplant Center-Level Summary Data. Minneapolis, MN.: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weng FL, Dhillon N, Lin Y, Mulgaonkar S, Patel AM. Racial differences in outcomes of the evaluation of potential live kidney donors: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35:409–15. doi: 10.1159/000337949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weng FL, Reese PP, Mulgaonkar S, Patel AM. Barriers to living donor kidney transplantation among black or older transplant candidates. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2010;5:2338–47. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03040410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lunsford SL, Simpson KS, Chavin KD, Menching KJ, Miles LG, Shilling LM, et al. Racial disparities in living kidney donation: is there a lack of willing donors or an excess of medically unsuitable candidates? Transplantation. 2006;82:876–81. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000232693.69773.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gore JL, Danovitch GM, Litwin MS, Pham PT, Singer JS. Disparities in the utilization of live donor renal transplantation. American Journal of Transplantation. 2009;9:1124–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lapasia JB, Kong SY, Busque S, Scandling JD, Chertow GM, Tan JC. Living donor evaluation and exclusion: the Stanford experience. Clinical Transplantation. 2011;25:697–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2010.01336.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norman SP, Song PX, Hu Y, Ojo AO. Transition from donor candidates to live kidney donors: the impact of race and undiagnosed medical disease states. Clinical Transplantation. 2011;25:136–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2009.01188.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reeves-Daniel A, Adams PL, Daniel K, Assimos D, Westcott C, Alcorn SG, et al. Impact of race and gender on live kidney donation. Clinical Transplantation. 2009;23:39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2008.00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore DR, Feurer ID, Zaydfudim V, Hoy H, Zavala EY, Shaffer D, et al. Evaluation of living kidney donors: variables that affect donation. Progress in Transplantation. 2012;22:385–92. doi: 10.7182/pit2012570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]