Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Longitudinal research is needed to identify predictors of continued electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use among youth. We expected that certain reasons for first trying e-cigarettes would predict continued use over time (eg, good flavors, friends use), whereas other reasons would not predict continued use (eg, curiosity).

METHODS:

Longitudinal surveys from middle and high school students from fall 2013 (wave 1) and spring 2014 (wave 2) were used to examine reasons for trying e-cigarettes as predictors of continued e-cigarette use over time. Ever e-cigarette users (n = 340) at wave 1 were categorized into those using or not using e-cigarettes at wave 2. Among those who continued using e-cigarettes, reasons for trying e-cigarettes were examined as predictors of use frequency, measured as the number of days using e-cigarettes in the past 30 days at wave 2. Covariates included age, sex, race, and smoking of traditional cigarettes.

RESULTS:

Several reasons for first trying e-cigarettes predicted continued use, including low cost, the ability to use e-cigarettes anywhere, and to quit smoking regular cigarettes. Trying e-cigarettes because of low cost also predicted more days of e-cigarette use at wave 2. Being younger or a current smoker of traditional cigarettes also predicted continued use and more frequent use over time.

CONCLUSIONS:

Regulatory strategies such as increasing cost or prohibiting e-cigarette use in certain places may be important for preventing continued use in youth. In addition, interventions targeting current cigarette smokers and younger students may also be needed.

What’s Known on This Subject:

Electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use among youth is rapidly increasing. Although studies have identified reasons youth cite for initially trying e-cigarettes, it is unknown whether these reasons relate to e-cigarette use longitudinally.

What This Study Adds:

Younger students, traditional cigarette smokers, and those trying e-cigarettes for low cost or to use them anywhere were more likely to continue e-cigarettes or use on more days. Findings suggest regulatory and intervention strategies are needed to prevent continued e-cigarette use.

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) are battery-operated devices used to vaporize solutions that may contain nicotine and flavors. E-cigarette use among middle and high school students is rapidly increasing.1,2 Data from the National Youth Tobacco Survey indicate current e-cigarette use rates tripled from 2013 to 2014 among middle school (1.1% to 3.9%) and high school (4.5% to 13.4%) students, and e-cigarettes were the most commonly used tobacco product in 2014.2 Similar rates have been found in our surveys from Connecticut where 1.5% of middle school students and 12.0% of high school students reported current use of e-cigarettes.3

Although some argue that e-cigarettes may be helpful for harm reduction or smoking cessation,4 others are concerned about the potential for initiation and continued use of e-cigarettes by youth,5,6 especially among youth who are not current traditional cigarette smokers given that little is known about the health effects of e-cigarettes at this time. As a result, researchers have examined reasons for initiating e-cigarettes to better understand what attracts people to this product. For example, data from focus groups and surveys indicate youth often try e-cigarettes because of curiosity, friend and family influences, and good flavors.7,8 A recent cross-sectional study in adult e-cigarette users identified similar reasons for experimentation and noted that adults who continued use were more likely to report trying e-cigarettes for goal-directed reasons (eg, using e-cigarettes where smoking is not allowed).9 However, studies to date have been limited to cross-sectional surveys assessing reasons for e-cigarette continuation or discontinuation retrospectively. Longitudinal research is needed to better understand what factors predict continued e-cigarette use over time.

In the present study, our goal was to build on our previous research identifying reasons for e-cigarette initiation7 by examining whether these reasons for trying e-cigarettes predicted continued use among youth over time. We analyzed a sample of anonymous longitudinal survey data from middle and high school students who ever tried e-cigarettes to identify specific reasons for trying e-cigarettes at wave 1 (fall 2013) that predicted continued e-cigarette use at wave 2 (spring 2014).

Based on previous research,7,9 we hypothesized that adolescents who tried e-cigarettes because of general interest (ie, curiosity or a belief that they are “cool”) would be less likely to continue using e-cigarettes. We hypothesized that the following reasons for trying e-cigarettes would predict an increased likelihood of continuing e-cigarette use: (1) desirable attributes (ie, good flavors, does not smell bad, can hide it from adults, low cost) in accordance with research on appeal and enjoyment of smoking10–13; (2) social norms (ie, friends use it, parents/family use it, can use it anywhere) based on evidence of the importance of peer and parental influences on smoking7,14; and (3) goal-directed reasons (ie, to quit smoking regular cigarettes or because it is healthier than regular cigarettes) based on findings in adult e-cigarette users.9 In addition, we explored whether these reasons for initiating e-cigarette use predicted not only continued use but frequency of use (ie, greater number of days used in the past month) at wave 2. Given evidence that youth e-cigarette users are more likely to be smokers of traditional cigarettes,3,15–17 we examined whether cigarette smoking status at wave 1 was associated with continued e-cigarette use or more frequent use at wave 2. These findings may help identify factors that relate to continued e-cigarette use over time that can be used to inform prevention and regulation efforts for youth.

Methods

Study Procedures

Study procedures were approved by the Yale Institutional Review Board and participating schools. Survey responses were confidential and anonymous, and students were informed that participation was voluntary. Information sheets were mailed to parents in advance of the study, and parents were instructed to contact the research staff if they did not want their child to participate. No parents from wave 1 and 12 parents from wave 2 declined participation for their child. Survey administration followed the same procedures outlined elsewhere.3,7

Data were obtained from school-wide surveys that were repeated in 2 middle schools and 3 high schools in fall 2013 and spring 2014. Surveys were matched across time points by using a self-generated identification code (SGIC)18,19 composed of 6 unique indicators: first letter of middle name, second letter of last name, day value from date of birth, school, homeroom, and sex. This method has been used in other longitudinal studies in which preserving anonymity is important, such as collecting data on youth substance use.19–21

In accordance with the recommended SGIC-matching procedures, SGICs with >1 missing variable were removed from the analysis. Data from both waves were then matched as long as they had ≥5 identical SGIC elements. These procedures have been shown to maximize valid matches in longitudinal anonymous data that do not collect participant names or identifiable information.20,22 The match rate of the study sample was 72.0%, representing 2100 students of 2915 who provided data at both wave 1 and wave 2 surveys. This match rate is comparable to other anonymous longitudinal surveys.19,22

Sample characteristics at wave 1 were compared between the matched and unmatched sample. Match rates were slightly higher among female students (77.7%) compared with male students (71.0%) (χ2 test [n = 2822], 16.71; P < .001). The matched sample was also slightly younger than the unmatched sample (mean ± SD age, 14.4 ± 1.9 vs 14.6 ± 2.0 years, respectively; t[1208.4] = 2.70; P = .007). Although these values are statistically different, the actual differences were small and not considered to be meaningful.

Participants

A subsample of ever e-cigarette users (n = 340) was used for the present analyses. The subsample was 47.4% female; 93.8% were high school students, and their mean age was 15.6 ± 1.2 years. The majority (86.2%) identified as white, 6.8% Hispanic, 2.4% Asian, 2.1% black, 1.5% biracial, and 1% “other.”

Wave 1 Measures: Fall 2013

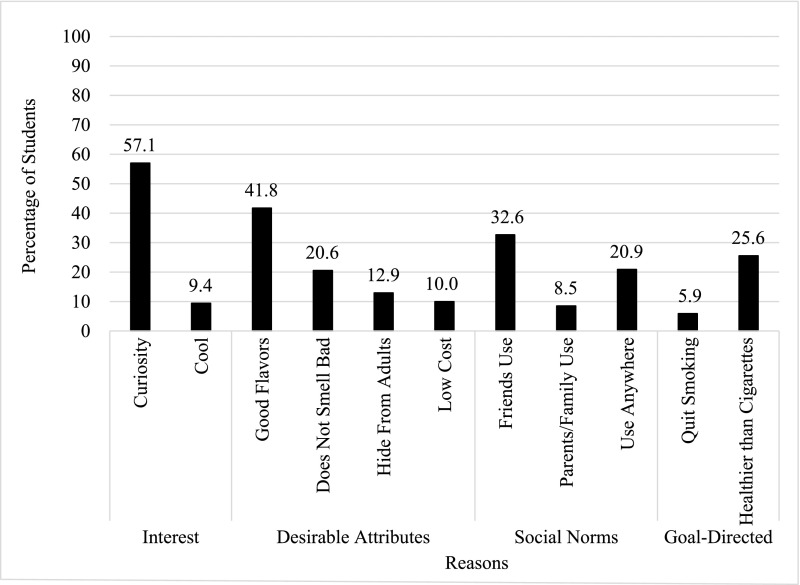

Students were selected as ever e-cigarette users if they responded “yes” to the question “have you ever tried an e-cigarette” (16.2% of the 2100 matched sample). Ever e-cigarette users reported reasons for first trying e-cigarettes and selected all that applied: curiosity, it is cool, good flavors, does not smell bad, can hide it from adult, low cost, my friends use it, my parents/family use it, can use it anywhere, to quit smoking regular cigarettes, it is healthier than regular cigarettes. Response options were coded as “yes/no” for each reason. Rates of endorsement are presented in Fig 1. Past month traditional cigarette smoking status was coded as “yes” (ie, ≥1 day of use, 25.3%) or “no.” Past month other tobacco use was coded as “yes” (ie, any use of smokeless tobacco, cigars, or hookah, 26.2%), or “no.” E-cigarette frequency at wave 1 was assessed with an open-response question: “How many days out of the last 30 did you use e-cigarettes”?

FIGURE 1.

Values represent the percentage of middle and high school students who endorsed each reason for first trying e-cigarettes among a subsample of youth who reported ever using e-cigarettes (n = 340).

Wave 2 Measures: Spring 2014

E-cigarette frequency at wave 2 was assessed with an open-response question: “How many days out of the last 30 did you use e-cigarettes”? Youth were coded as continuing (ie, ≥1 day of use in the past 30 days) or not continuing (ie, 0 days of use) e-cigarette use at wave 2.

Data Analysis

Analyses were conducted by using SPSS version 21 (IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). Logistic regression models examined reasons for trying e-cigarettes at wave 1 as predictors of continuing e-cigarette use at wave 2. Sensitivity analyses examined the pattern of results when continuation status was imputed (170 continuing vs 153 not continuing) based on other survey response options from wave 2 where possible (eg, a response of “I did not use e-cigarettes in the past 30 days”) and separately when these data were missing (140 continuing vs 102 not continuing). Odds ratios are presented as estimates of effect size rather than risk ratios given evidence that the assumption of homogeneity is more tenable for odds ratios.23

Among those who continued e-cigarette use, reasons for trying e-cigarettes at wave 1 were examined as predictors of e-cigarette frequency at wave 2 by using linear regression models given the normally distributed outcome. Youth who provided e-cigarette frequency data (n = 140) did not significantly differ from those without frequency data who were categorized as continuing e-cigarette use (n = 30) on key variables such as age, sex, race, or frequency of e-cigarette use reported at wave 1.

Given that multiple reasons could be selected, reasons were first entered into separate models and then into a simultaneous multivariable model to estimate both the independent and unique variance accounted for by each reason. Estimates are presented from unadjusted and adjusted models that included dichotomous covariates (sex, race, traditional cigarette smoking status, and other tobacco use). The primary outcomes did not differ significantly by school, but all models controlled for school status (middle school versus high school).

Results

Predictors of Continued E-Cigarette Use

Reasons for first trying e-cigarettes were examined as predictors of continued e-cigarette use (Table 1). In independent models, several reasons for first trying e-cigarettes predicted continued e-cigarette use, including good flavors, does not smell bad, can hide from adults, low cost, friends use, can use anywhere, to quit smoking regular cigarettes, and because they are healthier than cigarettes. Once including traditional cigarette smoking status in the model, good flavors, can hide from adults, and healthier than regular cigarettes no longer predicted continued e-cigarette use; these reasons were endorsed more often by current cigarette smokers. In a multivariable model including all reasons simultaneously, trying e-cigarettes to quit smoking was the most robust predictor of continued e-cigarette use. In addition, middle school students and traditional cigarette smokers were more likely to continue e-cigarette use over time. Similar results were obtained in sensitivity analyses that compared findings when continuation status was imputed based on other survey response options or left missing, except where noted in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Reasons for First Trying E-Cigarettes (Fall 2013) Predicting Continued Use of E-Cigarettes Over Time (Spring 2014)

| Reasons for Trying E-Cigarettes | Independent Models | Multivariable Models | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Interest | ||||

| Curiosity | 0.77 (0.50–1.20) | 0.86 (0.54–1.37) | 1.02 (0.60–1.70) | 0.97 (0.57–1.64) |

| It is cool | 2.14 (0.80–5.73) | 1.64 (0.72–3.74) | 1.62 (0.69–3.78) | 1.52 (0.64–3.61) |

| Desirable attributes | ||||

| Good flavors | 1.66 (1.06–2.61)a | 1.39 (0.86–2.22) | 1.12 (0.64–2.00) | 0.98 (0.54–1.78) |

| Does not smell bad | 2.46 (1.38–4.36)a | 2.23 (1.23–4.04)a,b | 1.36 (0.60–3.06) | 1.48 (0.64–3.39) |

| Hide from adults | 2.16 (1.10–4.28)a | 1.86 (0.92–3.78) | 0.80 (0.32–2.01) | 0.80 (0.31–2.04) |

| Low cost | 3.08 (1.34–7.08)a | 2.56 (1.08–6.06)a,b | 1.33 (0.48–3.64) | 1.48 (0.53–4.10) |

| Social norms | ||||

| Friends use | 1.69 (1.05–2.72)a | 1.67 (1.01–2.76)a,b | 1.41 (0.82–2.42) | 1.36 (0.78–2.38) |

| Parents/family use | 0.96 (0.43–2.11) | 1.16 (0.50–2.68) | 0.90 (0.36–2.22) | 0.94 (0.37–2.40) |

| Can use anywhere | 3.02 (1.66–5.49)a | 2.24 (1.18–4.26)a | 2.06 (0.95–4.48) | 1.56 (0.68–3.58) |

| Goal-directed | ||||

| To quit smoking cigarettes | 20.24 (2.67–153.30)a | 13.42 (1.72–104.38)a | 20.94 (2.64–166.46)a | 14.54 (1.80–117.80)a |

| Healthier than cigarettes | 1.80 (1.08–3.00)a | 1.60 (0.94–2.76) | 1.06 (0.57–1.99) | 1.14 (0.60–2.16) |

Reasons are coded yes = 1, no = 0. All models controlled for school status (middle school versus high school). aOR, adjusted odds ratio including covariates; OR, odds ratio.

Independent models reflect estimates when reasons are entered into separate logistic regression models. Multivariable models reflect estimates when reasons are entered simultaneously into the same logistic regression model. Results for covariates in final adjusted model: middle school (versus high school) OR, 2.86 (95% CI, 1.01–8.13); female (versus male) OR, 1.16 (95% CI, 0.70–1.92); white (versus nonwhite) OR, 0.52 (95% CI, 0.24–1.14); traditional cigarette use in the past month at wave 1 OR, 2.07 (95% CI, 1.12–3.82); other tobacco use in the past month at wave 1 OR, 1.38 (95% CI, 0.78–2.47).

Similar results are seen if including age instead of school status (middle school versus high school) in the model; age is negatively related to the odds of continuing e-cigarette use; OR, 0.72 (95% CI, 0.58–0.89).

Confidence intervals (CIs) that do not overlap 1.00, signifying statistical significance, P < .05.

Indicates results were no longer significant in sensitivity analyses that did not impute missing data.

Predictors of Number of Days of E-Cigarette Use

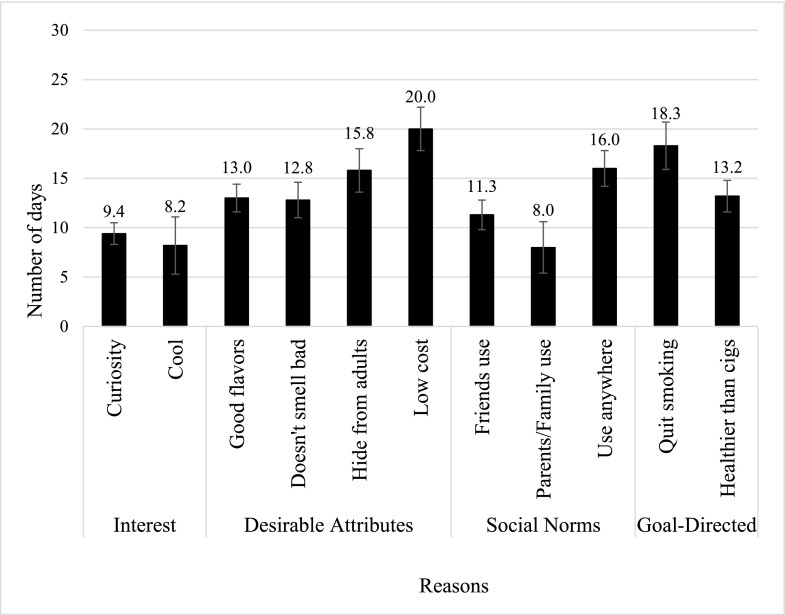

Among those who continued e-cigarette use, mean frequency of use (measured as the number of days used in the past 30 days) increased significantly from 7.4 ± 9.6 days at wave 1 to 10.4 ± 10.5 days at wave 2 (t[113] = –3.14; P = .002). Figure 2 displays the mean frequency of e-cigarette use at wave 2 based on specific reasons for trying e-cigarettes.

FIGURE 2.

Average e-cigarette frequency by reasons for first trying e-cigarettes. Values represent the mean (SE) number of days of e-cigarette use (of the past 30 days at wave 2, spring 2014), separated according to each reason for first trying e-cigarettes.

Reasons for first trying e-cigarettes were examined as predictors of e-cigarette frequency at wave 2 (Table 2). In independent models, several reasons for first trying e-cigarettes predicted more frequent use including good flavors, hide from adults, low cost, can use anywhere, and to quit smoking regular cigarettes, while curiosity predicted less frequent use. Once adjusting for other covariates including e-cigarette frequency at wave 1, trying e-cigarettes because of low cost was the most robust predictor of more frequent use at wave 2. In addition, middle school students and traditional cigarette smokers were using e-cigarettes more frequently at wave 2.

TABLE 2.

Reasons for First Trying E-Cigarettes (Fall 2013) Predicting the Number of Days of E-Cigarette Use in the Past Month (Spring 2014)

| Reasons For Trying E-Cigarettes | Independent Models | Multivariable Models | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||

| B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | |

| Interest | ||||||||

| Curiosity | –3.48 (1.79) | –0.16* | −1.98 (1.75) | −0.10 | −0.69 (1.80) | −0.03 | −1.67 (1.90) | −0.08 |

| It is cool | −3.55 (2.84) | −0.10 | −1.62 (2.56) | −0.05 | −1.06 (2.84) | −0.03 | −0.24 (2.84) | −0.01 |

| Desirable attributes | ||||||||

| Good flavors | 4.36 (1.81) | 0.20* | 2.04 (1.76) | 0.10 | 2.90 (2.00) | 0.14 | 0.69 (2.08) | 0.03 |

| Does not smell bad | 2.74 (2.04) | 0.12 | 3.05 (1.86) | 0.13 | −5.71 (2.92) | −0.24 | −1.15 (3.10) | −0.04 |

| Hide from adults | 6.23 (2.36) | 0.22** | 4.38 (2.27) | 0.15 | 0.72 (2.64) | 0.02 | 2.46 (2.60) | 0.08 |

| Low cost | 10.72 (2.36) | 0.36** | 7.52 (2.34) | 0.25* | 8.77 (3.01) | 0.30* | 7.02 (3.24) | 0.23* |

| Social norms | ||||||||

| Friends use | 0.78 (1.90) | 0.04 | 0.62 (1.73) | 0.03 | 1.51 (1.93) | 0.06 | 0.78 (1.93) | 0.04 |

| Parents/family use | −3.62 (3.22) | −0.10 | −0.22 (3.08) | −0.01 | −1.86 (3.22) | −0.05 | 0.24 (3.24) | 0.01 |

| Can use anywhere | 7.17 (1.90) | 0.30** | 2.95 (1.94) | 0.12 | 4.46 (2.52) | 0.19 | 0.10 (2.66) | 0.01 |

| Goal-directed | ||||||||

| To quit smoking cigarettes | 8.86 (2.55) | 0.28** | 4.86 (2.70) | 0.16 | 6.96 (2.62) | 0.22* | 3.58 (3.08) | 0.12 |

| Healthier than cigarettes | 3.44 (1.92) | 0.15 | 1.90 (1.78) | 0.08 | 0.36 (1.98) | 0.02 | 0.02 (2.07) | 0.001 |

Reasons are coded yes = 1, no = 0. All models controlled for school status (middle school versus high school). Independent models reflect estimates when reasons are entered into separate linear regression models. Multivariable models reflect estimates when reasons are entered simultaneously into the same linear regression model. Results for covariates in final adjusted model: middle school (versus high school), B = 10.19, SE = 3.30, β = 0.24, P = .003; female (vs male), B = –1.61, SE = 1.74, β = –0.08, P = .36; white (vs. non-white), B = –1.48, SE = 2.44, β = –0.04, P = .54; traditional cigarette use in the past month at wave 1, B = 4.86, SE = 1.94, β = 0.23, P = .01; other tobacco use in the past month at wave 1, B = –3.24, SE = 1.86, β = –0.16, P = .08; e-cigarette frequency in the past month at wave 1, B = 0.40, SE = 0.11, β = 0.36, P = .001.

Similar results are seen if including age instead of school status (middle school versus high school) in the model; age is negatively related to the frequency of e-cigarette use, B = –1.97, SE = 0.73, β = –0.26, P = .008.

P ≤ .05.

P ≤ .01.

Discussion

The present study used matched longitudinal data to examine whether reasons youth cite for initially trying e-cigarettes in fall 2013 (wave 1) predicted continued e-cigarette use and the frequency of e-cigarette use (measured by number of days used in the past 30 days) in spring 2014 (wave 2). These results extend previous research that identified reasons for initiating e-cigarettes among youth7 by examining how these reasons predict e-cigarette use longitudinally. Longitudinal studies of e-cigarette use patterns are a critical step in informing prevention efforts to reduce appeal and interest in using e-cigarettes among youth.

The most frequently endorsed reasons for trying e-cigarettes included curiosity, good flavors, and friends use, which are consistent with earlier research7 and suggest monitoring peer use and youth curiosity may be important for identifying risk for e-cigarette use. We found initial support for our hypotheses that reasons related to general interest (ie, curiosity, it is cool) would relate to experimentation but not continued use over time. Youth who reported trying e-cigarettes because of curiosity were using on fewer days of the past 30 days at wave 2 compared with those who did not endorse this reason, but this relationship was not robust or significant once including other covariates.

Conversely, we expected desirable attributes of e-cigarettes, social norms, and goal-directed reasons for trying e-cigarettes would predict continued and more frequent e-cigarette use, and initial support was found for these hypotheses. In particular, several desirable attributes (good flavors, does not smell bad, can hide from adults, and low cost), social norms (friends use and can use it anywhere), and goal-directed reasons for trying e-cigarettes (to quit smoking regular cigarettes and healthier than regular cigarettes) predicted continued use at wave 2 in independent univariate models. The most robust predictors of continued use included trying e-cigarettes because they can be used anywhere and to quit smoking traditional cigarettes. Other reasons may not have remained significant in the adjusted models in part due to their overlap with being a traditional cigarette smoker (eg, good flavors, hide from adults, healthier than cigarettes) or with other reasons that were endorsed. Furthermore, linear regression results indicated that trying e-cigarettes because of low cost was a robust predictor of more frequent e-cigarette use (more days used in the past 30 days) at wave 2, even after controlling for frequency of use at wave 1 and other covariates.

These results provide preliminary information that suggests part of the appeal of e-cigarette use for youth may be the ability to use e-cigarettes anywhere (eg, places where traditional cigarettes are presently banned, including indoor locations) or because of low cost. These findings suggest it may be important to consider creating and appropriately enforcing regulatory bans of e-cigarettes similar to current clean air laws for traditional cigarettes to help prevent continued e-cigarette use in youth.24 In addition, our findings are consistent with recent focus group research indicating that low cost is considered to be a positive characteristic of e-cigarettes,25 and they are the first to suggest low cost relates to continued use longitudinally. Evidence from national studies have shown that tobacco control policies that increased traditional cigarette prices were particularly effective in reducing youth smoking rates,26,27 suggesting it may be helpful to consider similar regulation strategies for e-cigarettes.

Trying e-cigarettes to quit smoking was also a robust predictor of continued e-cigarette use, which remained significant in a multivariable model even when controlling for other covariates and other reasons for trying e-cigarettes. However, this reason was endorsed by few youth (5.9%) and did not correlate highly with the endorsement of other reasons. Nonetheless, these results suggest that a subsample of youth e-cigarette users try e-cigarettes to quit smoking traditional cigarettes, which is in line with other research.28 Although the sample was small, 80% of youth who endorsed trying e-cigarettes to quit smoking were still smoking traditional cigarettes at wave 2. Furthermore, being a traditional cigarette smoker not only doubled the odds of continuing e-cigarette use but also predicted more days of e-cigarette use at follow-up. In light of these findings and concerns others have raised that dual use of traditional cigarettes and e-cigarettes potentially increases the risk of nicotine addiction in youth,15,16,29 developing effective cessation programs targeted for reducing both traditional cigarette and e-cigarette use among youth will be critical. In particular, health care providers can play an important role in screening youth tobacco use, advising abstinence from all tobacco products, and suggesting alternative cessation strategies for youth who are traditional cigarette smokers.

In terms of other covariates, younger students were more likely to continue e-cigarette use and use on more days in the past 30 days at follow-up. These findings are concerning given evidence that the adolescent brain is still developing and is highly sensitive to nicotine.30,31 More research is needed to understand the long-term effects of e-cigarette use among youth. In particular, future research related to the timing of e-cigarette initiation is needed to inform optimal delivery of intervention and prevention strategies. Evidence from other studies indicates that awareness and use of e-cigarettes are increasing among younger adolescents.2,32,33 These findings suggest interventions aimed at preventing e-cigarette initiation may be most effective for younger grades.

The current findings should be considered with the following limitations in mind. First, our results are limited by the self-report nature of the surveys and therefore may be subject to reporting bias. Second, it is possible that youth who had previously tried e-cigarettes but were not using in the past 30 days at wave 2 had simply experimented and were not ever regular users; however, we believe this population is still a useful reference group to compare with those youth who had previously tried and were still using e-cigarettes at wave 2. Third, we did not explicitly examine reasons why youth continue using e-cigarettes; our findings, however, may help inform this future research. After initially trying e-cigarettes, youth may continue to use for many reasons, including because they like certain aspects of the product or they become addicted to nicotine. Fourth, we surveyed a relatively diverse area, including multiple schools; however, our results may not generalize to other demographic samples, including those not currently in school or other geographic locations. Fifth, our estimates have wide confidence intervals given the low prevalence of endorsement of several reasons, and additional larger studies are needed to provide more precise effect estimates. Lastly, we are limited by the assessment time frames used here examining whether ever e-cigarette users continued use over the course of an academic year. However, even within this short amount of time, we were able to identify predictors of continued use that could be used to inform intervention efforts.

Conclusions

The current study builds on past research by identifying specific reasons for trying e-cigarettes that predict continued use longitudinally among youth. Younger students, users of traditional cigarettes, and those trying e-cigarettes for low cost or to use them anywhere were more likely to continue e-cigarettes or use on more days. These findings suggest regulatory strategies such as increasing cost or prohibiting e-cigarette use in certain places may be important for preventing continued use in youth. In addition, given the limited available information on e-cigarette safety for youth, it will be important to communicate potential health risks of tobacco use among youth.

Glossary

- SGIC

self-generated identification code

Footnotes

Dr Bold contributed to the conceptualization of the study, developed and tested the hypotheses reported in the article, ran all statistical analyses, and wrote the primary manuscript draft; Drs Kong, Cavallo, and Camenga contributed to the conceptualization of the study and the development of the self-report survey and critically reviewed drafts of the manuscript; Dr Krishnan-Sarin secured study funding, headed the conceptualization of the study and the development of the self-report survey, and critically reviewed drafts of the manuscript; and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse supplemental grants P50DA009241 and TCORS P50DA036151 to Dr Krishnan-Sarin; Dr Bold’s efforts were supported by T32DA019426. Dr Kong’s and Dr Camenga’s efforts were also partially supported by K12DA033012, Clinical and Translational Science Award grants UL1 TR000142 and K12 TR000140 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science, components of the National Institutes of Health, and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. These sponsors had no role in the study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; writing the manuscript; or the decision to submit the article for publication. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Camenga DR, Delmerico J, Kong G, et al. Trends in use of electronic nicotine delivery systems by adolescents. Addict Behav. 2014;39(1):338–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arrazola RA, Singh T, Corey CG, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Tobacco use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(14):381–385 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krishnan-Sarin S, Morean ME, Camenga DR, Cavallo DA, Kong G. E-cigarette use among high school and middle school adolescents in Connecticut. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(7):810–818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rahman MA, Hann N, Wilson A, Worrall-Carter L. Electronic cigarettes: patterns of use, health effects, use in smoking cessation and regulatory issues. Tob Induc Dis. 2014;12(1):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cahn Z, Siegel M. Electronic cigarettes as a harm reduction strategy for tobacco control: a step forward or a repeat of past mistakes? J Public Health Policy. 2011;32(1):16–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gornall J. Why e-cigarettes are dividing the public health community. BMJ. 2015;350:h3317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kong G, Morean ME, Cavallo DA, Camenga DR, Krishnan-Sarin S. Reasons for electronic cigarette experimentation and discontinuation among adolescents and young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(7):847–854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ambrose BK, Rostron BL, Johnson SE, et al. Perceptions of the relative harm of cigarettes and e-cigarettes among US youth. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(2 suppl 1):S53–S60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pepper JK, Ribisl KM, Emery SL, Brewer NT. Reasons for starting and stopping electronic cigarette use. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(10):10345–10361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchmann AF, Blomeyer D, Jennen-Steinmetz C, et al. Early smoking onset may promise initial pleasurable sensations and later addiction. Addict Biol. 2013;18(6):947–954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carpenter CM, Wayne GF, Pauly JL, Koh HK, Connolly GN. New cigarette brands with flavors that appeal to youth: tobacco marketing strategies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(6):1601–1610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Wit H, Phillips TJ. Do initial responses to drugs predict future use or abuse? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36(6):1565–1576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hersey JC, Nonnemaker JM, Homsi G. Menthol cigarettes contribute to the appeal and addiction potential of smoking for youth. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(suppl 2):S136–S146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi K, Forster J. Characteristics associated with awareness, perceptions, and use of electronic nicotine delivery systems among young US Midwestern adults. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(3):556–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dutra LM, Glantz SA. Electronic cigarettes and conventional cigarette use among U.S. adolescents: a cross-sectional study. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(7):610–617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grana RA. Electronic cigarettes: a new nicotine gateway? J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(2):135–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riker CA, Lee K, Darville A, Hahn EJ. E-cigarettes: promise or peril? Nurs Clin North Am. 2012;47(1):159–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGloin J, Holcomb S, Main DS. Matching anonymous pre-posttests using subject-generated information. Eval Rev. 1996;20(6):724–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yurek LA, Vasey J, Sullivan Havens D. The use of self-generated identification codes in longitudinal research. Eval Rev. 2008;32(5):435–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galanti MR, Siliquini R, Cuomo L, Melero JC, Panella M, Faggiano F; EU-DAP study group . Testing anonymous link procedures for follow-up of adolescents in a school-based trial: the EU-DAP pilot study. Prev Med. 2007;44(2):174–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grube JW, Morgan M. Attitude-social support interactions: contingent consistency effects in the prediction of adolescent smoking, drinking, and drug use. Soc Psychol Q. 1990;53(4):329–339 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kearney KA, Hopkins RH, Mauss AL, Weisheit RA. Self-generated identification codes for anonymous collection of longitudinal questionnaire data. Public Opin Q. 1984;48(1B):370–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook TD. Advanced statistics: up with odds ratios! A case for odds ratios when outcomes are common. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9(12):1430–1434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization Protection from Exposure to Second-Hand Tobacco Smoke: Policy Recommendations. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wagoner KG, Cornacchione J, Wiseman KD, Teal R, Moracco KE, Sutfin E E-cigarettes, hookah pens and vapes: adolescent and young adult perceptions of electronic nicotine delivery systems. Nic Tob Res. 2016;pii:ntw095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Hasselt M, Kruger J, Han B, et al. The relation between tobacco taxes and youth and young adult smoking: what happened following the 2009 US federal tax increase on cigarettes? Addict Behav. 2015;45:104–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson LM, Avila Tang E, Chander G Impact of tobacco control interventions on smoking initiation, cessation, and prevalence: a systematic review. J Environ Public Health 2012;2012:1-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Camenga DR, Cavallo DA, Kong G, et al. Adolescents’ and young adults’ perceptions of electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation: a focus group study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(10):1235–1241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wills TA, Knight R, Williams RJ, Pagano I, Sargent JD. Risk factors for exclusive e-cigarette use and dual e-cigarette use and tobacco use in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/135/1/e43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Counotte DS, Smit AB, Pattij T, Spijker S. Development of the motivational system during adolescence, and its sensitivity to disruption by nicotine. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2011;1(4):430–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dwyer JB, McQuown SC, Leslie FM. The dynamic effects of nicotine on the developing brain. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;122(2):125–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grana R, Benowitz N, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes: a scientific review. Circulation. 2014;129(19):1972–1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carroll Chapman SL, Wu LT. E-cigarette prevalence and correlates of use among adolescents versus adults: a review and comparison. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;54(0):43–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]