China has the world's second largest tuberculosis (TB) burden after India [1]. Healthcare workers (HCWs) in China's National TB Control Programme have a significantly increased level of exposure to TB disease and patients. After the severe acute respiratory syndrome pandemic in 2003, the Chinese government made increased efforts to protect HCWs from nosocomial TB infections and other respiratory infectious diseases, especially for those HCWs working in chest hospitals and infectious disease hospitals. These efforts (although not universal throughout China) included the increased use of biosafety level 3 (BSL3) laboratories and respiratory isolation through negative pressure wards and rooms, and the practice of standardised biosafety protocols and procedures through continued training and education.

Short abstract

BSL3 and respiratory isolation wards protect healthcare workers from nosocomial TB infection in China http://ow.ly/PGvSl

To the Editor:

China has the world's second largest tuberculosis (TB) burden after India [1]. Healthcare workers (HCWs) in China's National TB Control Programme have a significantly increased level of exposure to TB disease and patients. After the severe acute respiratory syndrome pandemic in 2003, the Chinese government made increased efforts to protect HCWs from nosocomial TB infections and other respiratory infectious diseases, especially for those HCWs working in chest hospitals and infectious disease hospitals. These efforts (although not universal throughout China) included the increased use of biosafety level 3 (BSL3) laboratories and respiratory isolation through negative pressure wards and rooms, and the practice of standardised biosafety protocols and procedures through continued training and education.

Systematic TB screening in HCWs can improve their awareness of TB infection [2]. The tuberculin skin test (TST) has been widely used for the detection of TB infection for decades but due to cross-reactivity with the bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination and exposure to non-TB mycobacteria, the TST fails to provide sufficient specificity for the detection of TB infection [2]. In the past decade, interferon-γ (IFN-γ) release assays have been developed and commercialised to measure the in vitro release of IFN-γ from effector T-cells stimulated with the Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific antigens (the 6-kDa early secretory antigenic target and 10-kDa culture filtrate protein) as an aid to diagnosing TB infection. These new screening assays (QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube (Qiagen, Venlo, the Netherlands) and T-SPOT.TB (Oxford Immunotec, Abingdon, UK)) have demonstrated higher specificity and at least comparable sensitivity for the diagnosis of TB infection compared with the TST [3].

The goal of the present study was to investigate and describe latent TB infection (LTBI) among HCWs in China, and the effectiveness of infection control strategies in TB hospitals using the T-SPOT.TB assay and TST. This study was conducted in two major primary referral hospitals for TB patients and other respiratory infectious diseases in Shandong Province, China, in 2013: the Shandong Provincial Chest Hospital (SPCH), Jinan; and Linyi Municipal Chest Hospital (LMCH), Linyi. Approximately 3000 patients with active TB disease are treated in each hospital annually. Since 2004, both hospitals have been equipped with BSL3 laboratories that are used for mycobacterial specimen testing (acid-fast bacillus (AFB) smear test, culture and species identification) and respiratory isolation wards with negative pressure rooms for smear-positive TB patients. As recommended by China's National Tuberculosis Control Programme, the TST was carried out by the Mantoux method using a 5 tuberculin unit dose of BCG purified protein derivative (Chengdu Institute of Biological Products, Chengdu, China). An induration of ≥10 mm was defined as a positive TST. A blood sample for the T-SPOT.TB assay was drawn from each HCW before the TST was performed. T-SPOT.TB assays were carried out and interpreted according to the manufacturer's instructions. Spot counts were analysed using an ELISPOT reader (CTL-ImmunoSpot S5 Core Analyzer; Cellular Technology Ltd, Shaker Heights, OH, USA). Covariates (age, sex, working year and job category) associated with positive T-SPOT.TB results were analysed by univariate and multivariate analyses. Univariate p-values were determined for each covariate by logistic regression. Covariates with univariate p-values <0.20 were included in multivariate logistic regression models. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata/SE version 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of SPCH and LMCH.

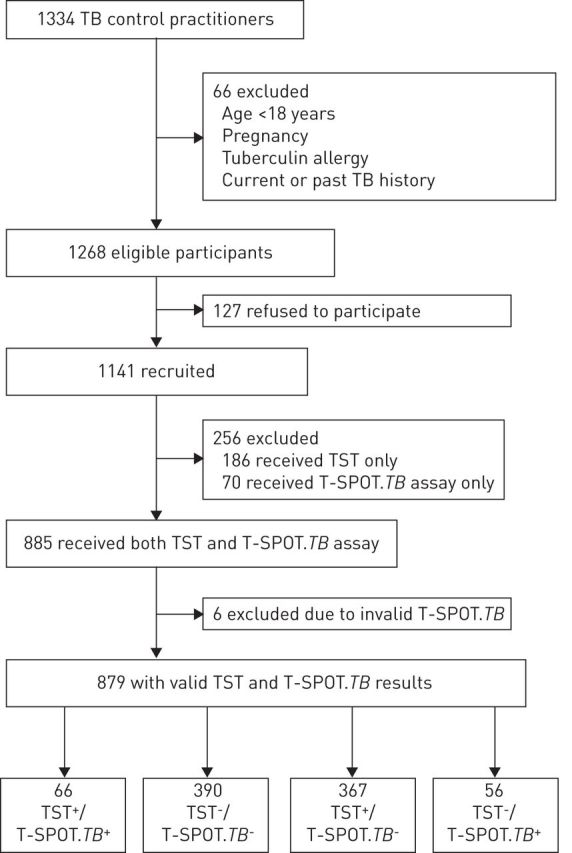

1141 HCWs (median age 35 years, range 19–70 years; physicians 18.1%, nurses 42.3%, laboratory staff 4.3%, medical technicians 10.9%, hospital logistic staff 12.7%, administrative staff 11.7%) out of 1334 total employees of both hospitals were enrolled and screened for TB infection in this study, after 66 were excluded due to age <18 years, pregnancy, tuberculin allergy or past TB disease history, and 127 refused to participate (figure 1). 935 (82.9%) out of 1141 HCWs had BCG vaccination scars and 1071 (94.0%) reported having been exposured to active TB. Of 1141 HCW participants, 70 (6.1%) were only given the T-SPOT.TB assay, 186 (16.3%) received the TST alone and six had an indeterminate or failed T-SPOT.TB assay (figure 1). A total of 879 HCWs (median age 34 years, mean age 35.8 years; range 19–70 years) had both TST and T-SPOT.TB results available for analysis. The overall positivity rate of T-SPOT.TB testing was 13.9% (122 out of 879; 95% CI 11.7–16.3%), while the TST positivity rate was 49.3% (433 out of 879; 95% CI 45.9–52.5%). The agreement between TST and T-SPOT.TB test results was 51.9% (95% CI 48.6–55.2%; κ=0.027).

FIGURE 1.

Study flow diagram. TST+ cut-off point ≥10 mm. TB: tuberculosis; TST: tuberculin skin test.

Results for univariate analysis showed that T-SPOT.TB positivity was only associated with older age and longer duration of healthcare service. In multivariate models that included both subject age and longer duration of healthcare service, only duration of healthcare service remained significantly associated with positive test results. Specifically, subjects with >10 years of service had the highest odds of a positive test result (univariate OR 2.25, 95% CI 1.53–3.31; >10 years versus ≤10 years of service).

Our data suggests that the highly specific T-SPOT.TB assay had a significantly lower rate of positivity among HCWs at the SPCH and LMCH than the TST and when compared with other hospital-based studies in Beijing, China (13.9% versus 33.6% at Beijing Chest Hospital (BCH) and 28.6% in a tertiary general hospital in Beijing) [4, 5]. Compared to the data from BCH, both study HCW populations (SPCH/LMCH versus BCH) share similarities in distribution of age and sex and occupational levels of exposure to M. tuberculosis. In addition, data from the 2011 Chinese National TB Surveillance Summary suggest the reported prevalence of TB disease in Shandong Province (SPCH/LMCH) and Beijing (BCH) are also similar at 15–44 cases per 100 000 population [6]. Thus, the only major discernible difference between SPCH/LMCH and BCH is the lack of an ISO15189-certified TB reference laboratory and respiratory isolation wards with negative pressure rooms for AFB smear-positive TB patients at the BCH. In conclusion, a proactive and comprehensive strategy for nosocomial infection control practices plays a pivotal role in protecting HCWs from TB infection, which should be implemented in all chest hospital and infectious disease settings in China.

The importance of effective measures against nosocomial TB infection has been clearly emphasised by the World Health Organization Stop TB strategy and recent Policy on Infection Control [7]. Towards the goal of TB elimination, prevention and treatment of LTBI are essential elements of global TB control efforts [8–10]. HCWs working in clinical facilities managing TB patients are definitely at the top of high-risk populations of LTBI and TB, and need effective occupational health protection.

Footnotes

Support statement: The authors thank the Katharine Hsu Foundation for overall support of epidemiological studies in Shandong. Xin Ma is supported by US National Institutes of Health grant RO1 AI075465 and a Shandong Taishan Scholarship (tshw20110537). Funding information for this article has been deposited with FundRef.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2013. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/91355/1/9789241564656_eng.pdf

- 2.Dorman SE, Belknap R, Graviss EA, et al. Interferon-γ release assays and tuberculin skin testing for diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection in healthcare workers in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 189: 77–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pai M, Denkinger CM, Kik SV, et al. Gamma interferon release assays for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 2014; 27: 3–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang X, Jia H, Liu F, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for latent tuberculosis infection among health care workers in China: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2013; 8: e66412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang LF, Liu XQ, Zhang Y, et al. A prospective longitudinal study evaluating a T-cell-based assay for latent tuberculosis infection in health-care workers in a general hospital in Beijing. Chin Med J (Engl) 2013; 126: 2039–2044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu W. 5th China National Tuberculosis Surveillance Report. Beijing, Military Medical Science Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sotgiu G, D'Ambrosio L, Centis R, et al. TB and M/XDR-TB infection control in European TB reference centres: the Achilles’ heel? Eur Respir J 2011; 38: 1221–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diel R, Loddenkemper R, Zellweger JP, et al. Old ideas to innovate tuberculosis control: preventive treatment to achieve elimination. Eur Respir J 2013; 42: 785–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D'Ambrosio L, Dara M, Tadolini M, et al. TB elimination: theory and practice in Europe. Eur Respir J 2014; 43: 1410–1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lönnroth K, Migliori GB, Abubakar I, et al. Towards tuberculosis elimination: an action framework for low-incidence countries. Eur Respir J 2015; 45: 928–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]