Abstract

Purpose

Controversy exists regarding the necessity and timing of genitoplasty in girls with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH). Our knowledge of surgical preferences is limited to retrospective series from single institutions and physician surveys which have suggested a high rate of early reconstruction. Our objective was to evaluate current CAH surgical treatment in academic centers.

Methods

We queried the FPSC database to identify all girls under 18 years of age with a diagnosis of CAH between 2009 and 2012. Procedures were identified by CPT codes for vaginoplasty, clitoroplasty and other genital procedures. Type of reconstruction, age at surgery and surgeon-volume were analyzed.

Results

There were a total of 2,614 females with a diagnosis of CAH seen at 60 institutions identified in the database. Of infants who were less than 12 months of age between 2009 and 2011, as few as 18% proceeded to surgery within a one to four year follow up period. Of those referred to a pediatric urologist, 46% proceeded to surgery. Of girls who had surgery before 2 years of age, 73% underwent clitoroplasty and 89% vaginoplasty; 68% had a combined procedure. A medium- or high-volume surgeon was involved in 63% of cases.

Conclusions

Many girls with CAH did not proceed to early reconstructive surgery. Of those referred to surgeons, possibly the most virilized girls, about half proceeded to early surgery and almost all had vaginoplasty as a component of surgery. About two-thirds of procedures were performed by medium- or high- volume surgeons indicative of DSD surgical centralization.

Keywords: adrenal hyperplasia; congenital (CO, EP, SU); virilism (CN, CO, EP, SU); disorders of sexual development (CO, EP, SU)

INTRODUCTION

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) is the most common diagnosis in virilized infants with 46,XX DSD.1 Even so, it is a rare diagnosis occurring in approximately 1 of 5,000 to 20,000 individuals.2 Surgical aims for virilized girls with CAH are to create cosmetic and functional external genitalia from a sexual, reproductive and urinary standpoint.3

Concerns remain as to the potential need for additional procedures, long-term effects on psychosocial and sexual function as well as cosmetic and functional outcomes.4 The 2006 statement of the International Consensus Conference on Intersex was published in response to these concerns and recommended a multidisciplinary approach with centralized surgical care. Feminizing genitoplasty was only recommended in cases of severe virilization. For clitoral surgery, preservation of innervation and function was emphasized. Finally, the statement recommends that children with an inadequate vagina should be repaired in adolescence as those repaired in infancy should anticipate further pubertal reconstructive procedures.1

Following the release of this statement, knowledge of practice patterns remains limited to physician surveys and retrospective series from high-volume centers. At the Fourth World Congress of the International Society of Hypospadias and Disorders of Sex Development, the majority of respondents (87%) reported utilizing multidisciplinary care teams in the management of children with CAH. As for surgical centralization, 50% of surgeons surveyed performed 5 or more feminizing genitoplasties per year. Although without reference to virilization, 78% (48/61) of surgeons surveyed preferred to perform feminizing genitoplasty prior to the age of 2 years. Of these surgeons, however, 42% (20/48) would delay some components. The most common clitoroplasty approach was partial excision of the corporal bodies and for vaginoplasty a Fortunoff U-flap vaginoplasty.5

A study from the largest DSD referral center in the UK assessed changes in management of adolescents with ambiguous genitalia between 2001 and 2012 and found a minimal decrease in clitoroplasty or overall surgical reconstruction rates in infancy or early childhood (from 100 to 93%) but a greater decrease (from 100 to 80%) in rates of concomitant vaginoplasty. Current techniques additionally modeled the recommendations further: 86% of individuals from the more recent cohort underwent neurovascular sparing clitoroplasty and only 8% of children who had a vaginoplasty underwent a vaginal substitution surgery in infancy. This study was encouraging since it reported improved cosmetic outcomes and a decreased need for secondary procedures.6

Given the lack of large-scale data regarding current surgical practice, our primary objective was to evaluate current practice patterns in United States academic centers including prevalence of children proceeding to surgical procedures, age of children at time of surgery and type of reconstructive procedures performed for girls with a diagnosis of CAH. As secondary outcome measures, we evaluated the degree of centralization of care with analysis of surgeon and hospital volume and whether volume was associated with timing of reconstruction.

METHODS

The Faculty Practice Solutions Center (FPSC) is a national billing database that was queried to identify all patient encounters for females less than 18 years of age with a diagnosis of an adrenogenital disorder (ICD-9 255.2). Data was obtained from more than 90 academic centers in the United States between Jan 1, 2009 to Dec 31, 2012. We further analyzed incidence of diagnosis by date of birth during this 4-year period.

To capture all relevant procedures, all urologic, gynecologic and gastrointestinal CPT codes (40000-50000) billed for these children were compiled. After analyzing these codes for relevance to a genitourinary reconstructive procedure, the following were then selected as index feminizing genitoplasty procedures: clitoroplasty (56805), repair of introitus (56800) and 2 additional codes for vaginal surgery (57291 and 57335). Other relevant codes included perineoplasty (56810), reconstruction of urethra (53430), lysis of labial adhesions (56441), dilation of vagina (57400) or unspecified genital procedure (58999) and were termed ‘other reconstructive procedures.’ We analyzed the occurrence of any of the above codes or combination of codes to determine both the first procedure during the 4-year period and subsequent reconstructive procedures with patient age at time of these procedures.

We further used E&M inpatient and outpatient consultation CPT billing codes (99221-99226, 99251-99255, 99201-99205, 99241-99245) to evaluate timing of initial evaluation by either a urologist or endocrinologist and the time that elapsed following the consultation until surgical intervention. A pediatric urologist designation occurred either by self-identification as a urologist who also performed at least one hypospadias or orchiopexy during the study period for a child under 12 years of age or was a surgeon who lacked self-identification but completed a minimum of six annual orchiopexies (54640) and six annual hypospadias repairs (54322-26) in children younger than 12 years old. Pediatric endocrinologists were defined as those who evaluated at least six children under 12 years of age with a diagnosis of short stature (783.43) and diabetes (250) annually and were self-identified in the database as having an endocrine specialty. A linear mixed effects model was used to compare the mean time from consult to surgery between surgeon-volume groups. The model included a random effect for surgeon to adjust for within-surgeon correlations and time was log transformed prior to analysis.

Cohort incidence analysis, consultation to surgery

To determine more accurately the timing of initial procedures performed in infants and young children, a subgroup analysis was performed for infants with an initial consultation before 12 months of age with either specialist between Jan 1, 2009 and Dec 31, 2011. Procedures performed in these children through Dec 31, 2012 were evaluated to allow a minimum of one year of follow-up. The proportion of children who proceeded to surgery following consultation with either specialist as well as time from consultation to surgery were evaluated in this cohort. The indication for this analysis was to further determine whether consultation timing, institution volume or surgeon volume was associated with timing of surgery. Additionally, to provide a minimum estimate of the percentage of children who proceeded to early surgery we evaluated procedures performed in all children who were 0 to 12 months of age between January 1, 2009 and Dec 31, 2011 followed until Dec 31, 2012 regardless of consultation status.

Cohort incidence analysis, virilization

Since we found a lower than anticipated proportion of girls proceeding to surgical reconstruction and since many individuals with CAH have non-classical forms without virilization, we attempted to identify the diagnosis of virilization and to analyze its association with age and timing of surgery. We included girls with both a CAH diagnosis and a second ICD-9 code 752.x indicative of “congenital anomaly of genital organs.”

Insurance, race and region

Patient demographics including region, race and insurance type for all children with a diagnosis of CAH were obtained. Multivariate analyses using a mixed effects model with random effect for surgeon and time log transformed was completed to evaluate for effects of these factors in association with time from consultation to surgery and age of children at time of surgical reconstruction.

Surgeon and hospital volume

Surgeon- and hospital-volume was divided into three cohorts for analysis: less than 4 cases, 4 to 10 cases and greater than 10 cases in 4 years were designated as low-, medium- and high-volume, respectively, consistent with the European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology recommendation for treatment to occur in high-volume surgical centers.7 If multiple surgeons were associated with a procedure, the highest volume surgeon was counted as the surgeon for analysis.

RESULTS

There were a total of 2,614 female patients identified who had a diagnosis of congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Of the total, 1,104 had an initial consult with either a urologist or endocrinologist recorded. When analyzing only children who were born during the 4-year study period, 573 children were identified who had a date of birth between Jan 1, 2009 and Dec 31, 2012 (mean 143 births/year).

A total of 260 feminizing genitoplasty procedures were performed in 219 patients. These were performed in 60 hospitals by 66 urologists and 20 other surgeons (pediatric general surgery and gynecology), although multiple surgeons were involved during several procedures. There were 219 first, 32 secondary and 9 tertiary procedures during the study period (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

First procedures performed

| Patient Age (y) | Vaginoplasty alone (n=56) | Clitoroplasty alone (n=21) | Combined Vaginoplasty / Clitoroplasty (n=110) | Genitoplasty other (n=32) | Total (n=219) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 | 19 | 2 | 57 | 3 | 81 |

| 1 to 2 | 6 | 4 | 24 | 4 | 38 |

| 2 to 5 | 4 | 4 | 15 | 7 | 30 |

| 5 to 10 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 20 |

| > 10 | 21 | 7 | 8 | 14 | 50 |

Table 2.

Second and third procedures performed

| Patient Age (y) | Vaginoplasty alone (n=5) | Clitoroplasty alone (n=1) | Combined Vaginoplasty / Clitoroplasty (n=1) | Genitoplasty other (n = 34) | Total (n=41) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| 1 to 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 11 |

| 2 to 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 11 |

| 5 to 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| > 10 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 10 |

Primary procedures, all ages

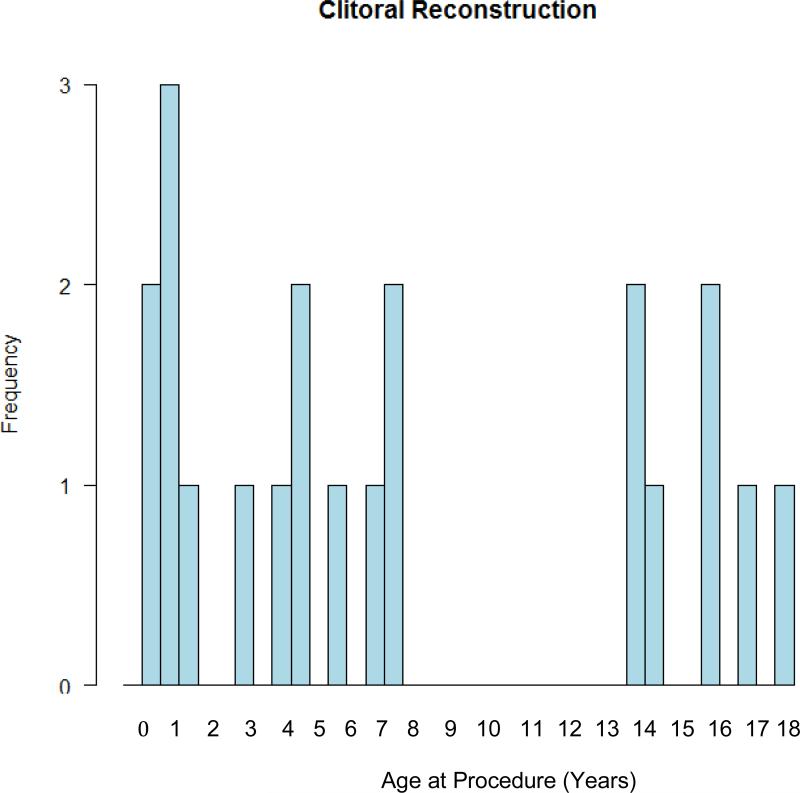

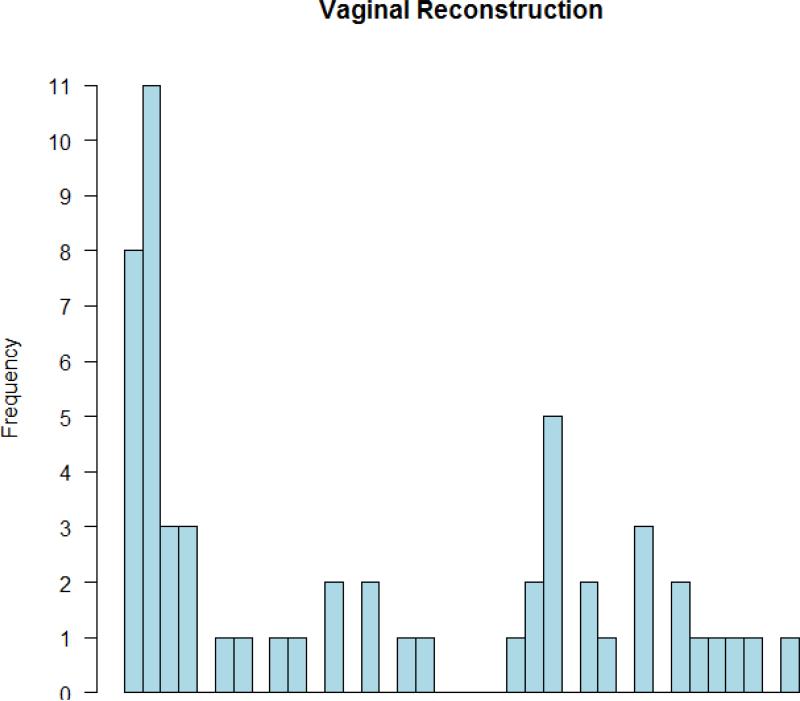

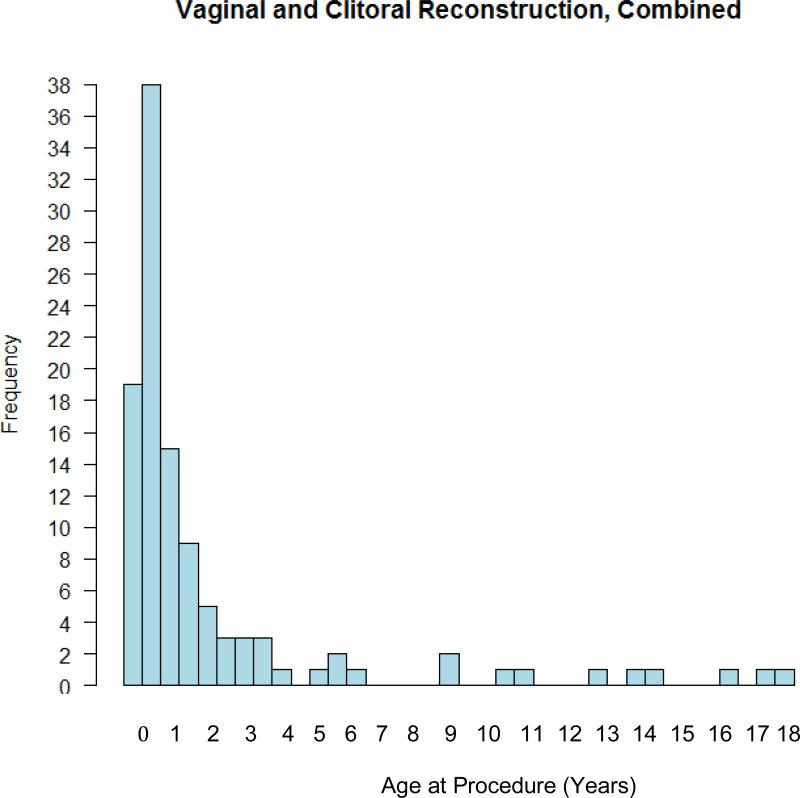

Of the total first recorded procedures per child, 110 combined clitoroplasty and vaginoplasty, 56 vaginoplasty alone, 21 clitoroplasty alone and 32 other reconstructive procedures were performed (Table 1). The median age of first procedures in the combined genitoplasty cohort was the youngest (11.3 months) with 74% of total combined procedures performed at less than 2 years of age. Vaginoplasty alone and clitoroplasty alone were performed at older median ages (53 and 70 months respectively). The histogram plots of all surgeries performed and timing of each procedure illustrate bimodal peaks for infants and adolescents for clitoroplasty alone or vaginoplasty alone (Figures 1 and 2) and skewing toward infancy for combined procedures (Figure 3). In evaluation of all first procedures recorded in children less than 2 years of age, 89% of surgeries included vaginoplasty and 73% included clitoroplasty. Of those having surgery, 68% had a combined procedure, 5% clitoroplasty alone and 21% vaginoplasty alone.

Figure 1.

Histogram of age at time of clitoroplasty alone reconstructive procedures

Figure 2.

Histogram of age at time of vaginoplasty alone reconstructive procedures

Figure 3.

Histogram of age at time of vaginoplasty and clitoroplasty combined reconstructive procedures

Secondary procedures, all ages

Within the four-year window, secondary procedures occurred primarily in the ‘other reconstructive procedure’ category with only one recorded combined vaginoplasty and clitoroplasty (Table 2). Tertiary procedures followed the same pattern: 1 vaginoplasty and 8 ‘other reconstructive procedures’ were performed.

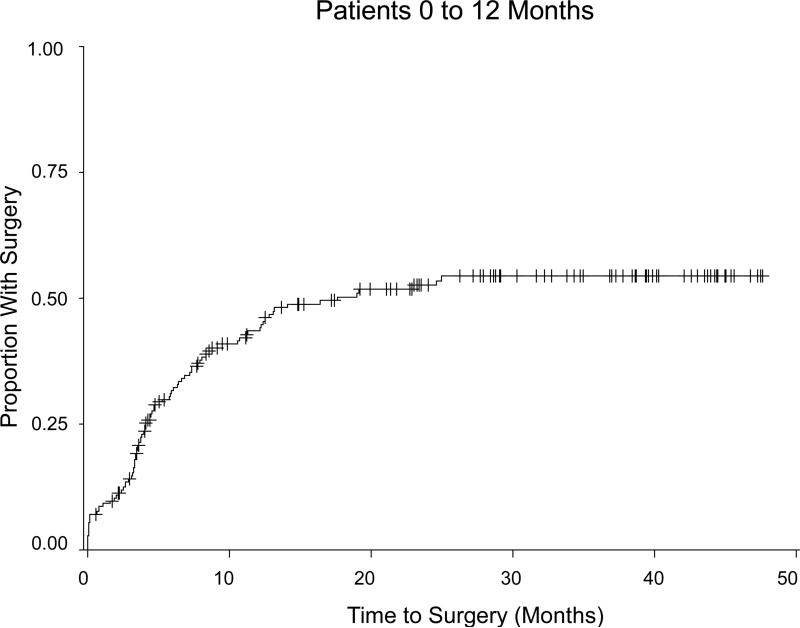

Cohort incidence analysis, consultation to surgery

Of the 577 infants who were less than 12 months of age during the first 3 years of the study period 106 (18%) underwent a reconstructive procedure within the one to four year follow up. Of these children, 347 were evaluated by an endocrinologist of whom 82 (24%) proceeded to surgery. There were 186 children evaluated by a urologist of whom 91 (49%) proceeded to surgery (Figure 4). Of the 106 total procedures performed in this cohort, 70% underwent a combined reconstructive procedure. Only 4% of the total procedures were coded as clitoroplasty alone; 22% of the total represented vaginoplasty alone.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier plot of time from initial evaluation by a urologist to surgery for children who were 0 to 12 months old at the time of this evaluation

Cohort incidence analysis, virilization

Among the 412 children born during the first 3 years of the study and followed for a minimum of one year, 181 had both diagnostic codes 255.2 (CAH) and 752.X (congenital anomaly of genital organs) recorded. Of these, 44.2% (80) underwent a procedure during the study period. Of these children with surgery, 71.2% (57) underwent a combined vaginoplasty and clitoroplasty.

Insurance, race and region

In a multivariate analysis of children who were 0-12 months of age at time of consultation, Medicaid insurance (p=0.02, estimated age difference 2.9 months; 95% CI 0.4, 5.4) or self-pay status (p=0.04, age difference 6.3; 95% CI 0.4, 12.1) was significantly associated with an increased age at reconstructive surgery as compared to private insurance. No associations were found between race or region and age at time of surgery. There was, however, a significantly longer time from consultation to surgery for children with self-pay (p=0.001, mean ratio 3.6; 95% CI 1.8, 7.3) versus commercial insurance. No effect was associated with Medicaid or other insurers, race or region.

Surgeon volume

Among all surgeons who performed reconstructive procedures, there were 70 low-, 14 medium- (4-10 cases/4-year) and 2 high-volume (11 or more cases/4-year) surgeons. Analysis of surgeon case-volume by highest-volume surgeon listed in a case showed that 32% of reconstructive procedures included a medium-volume surgeon and 31% of cases included a high-volume surgeon. Only two surgeons, who performed 27 and 34 procedures respectively, were high-volume surgeons. The median time to surgery was 13 months overall. Time to surgery was shorter for patients seen by a high-volume surgeon who performed the case a median of 1.1 months from consultation (range 0-19 months, IQR 4.1) as compared to a medium-volume surgeon at 6.6 months (0-44.1, 7.9) or a low-volume surgeon at 6.9 months (0.7-19.1, 5.9) after consultation. This did not translate to a difference in age at time of reconstruction (p=0.96). There was no significant difference in time to surgery between medium- and low-volume surgeons (p=0.97).

Hospital volume

There were 3 high-volume institutions performing 14, 27 and 34 cases during the 4-year period. The remaining hospitals performed 10 or fewer such procedures during the 4-year study period. Children who were seen at a high-volume institution (>10 cases/4-year period) were nearly three times more likely to have a consultation by both an endocrinologist and a urologist at the same institution (23 versus 8% of total children with a CAH diagnosis). Children seen at high-volume institutions by both an endocrinologist and a urologist were nearly twice as likely to undergo reconstruction (73.9%) than if evaluated at an institution that performed 1-10 reconstructive procedures in the 4-year period (40.2%).

DISCUSSION

Controversies exist regarding optimal timing, indications and techniques for feminizing genitoplasty procedures. Opponents of early surgery cite concerns regarding the frequent need for further reconstructive procedures, a lack of multi-institution long-term data regarding function and cosmesis in adulthood and an inability to obtain informed consent of the child in infancy. Advocates of early surgery argue that there may be psychosocial benefits for child and parent provided by consistency of anatomy with gender of rearing, potential better quality of genital tissue with exposure to maternal estrogens in infancy and the relatively minor procedures anticipated later in life as compared to the initial reconstruction.1, 5

These unanswered questions regarding optimal management of CAH highlight the relevance of a study such as this to inform the debate through a detailed assessment of current practice. To our knowledge, this study is unique in its era and scope. It captures the breadth of surgical practices including variations in timing and type of reconstructive procedures performed and provides insight into centralization and surgeon experience with these procedures.

Despite limitations imposed by a 4-year window, this study allows the observation that feminizing genitoplasty in infants with CAH continues to be performed and approximately 90% of the time includes a vaginoplasty as a portion of the procedure. A comparable unpublished study from an earlier 4-year period presented in 2010 indicated similar findings. DaJusta et al used the PHIS database to evaluate CAH genitoplasties between 2004 and 2008 in 42 hospitals. There were 187 procedures performed. When evaluating the timing of procedures in each of 3 categories (combined, vaginoplasty alone or clitoroplasty alone), the category performed at the youngest median age was combined vaginoplasty and clitoroplasty with 76% performed at less than 2 years of age (compared to 68% in our current evaluation). In this unpublished study, 78% of all procedures performed in children less than 2 years of age included a vaginoplasty (compared to 89% in our current evaluation).8

However, a unique finding of the current study is that many infants with CAH (up to 82%) did not proceed to an early surgery (1 to 4 year follow up). This may be due to absent to mild virilization associated with nonclassical forms of CAH, postponement of surgery or surgery being performed at a different institution. A CAH diagnosis refers to the enzymatic defect in steroid synthesis pathways but varied phenotypic outcomes may be observed.9 A potential limitation in describing surgical practice patterns is the inability in this database to determine the degree of virilization. One manner in which this was addressed was by including the presence of a second ICD-9 code 752.x which is used for “congenital anomaly of genital organs” in an attempt to find virilized patients. When a child had both diagnoses during the first three years of the study and was followed for a minimum of one year, 44% of these girls underwent a surgical procedure compared to 18% without the diagnosis. Additionally, although the code 255.2 is overall specific to CAH, it may include a few rare instances of other adrenogenital disorders such as Achard-Thiers syndrome or virilization of a fetus due to maternal exposure through endogenous (eg adrenal tumor) or exogenous androgen sources.

Additional possible limitations of a database study were addressed. Although we attempted to avoid missing relevant procedural codes through a top-down approach of code identification, miscoding of procedures is a possible means to underrepresent cases completed. In addition, although it does not eliminate the possibility of transfer of care, specifically evaluating children who were seen by either an endocrinologist or a urologist may provide a more accurate portrayal of children who were managed within a single institution.

Our results suggest that combined vaginoplasty and clitoroplasty is the most common procedure performed in infancy and early childhood and appears to be primarily restricted to this age range (Figure 3). Of those having surgery before 2 years of age, 89% of cases included a vaginoplasty. This is despite controversy regarding the optimal timing of vaginoplasty as noted in the 2006 Consensus Statement recommendation that surgeons should outline to parents the anticipated course which includes future reconstructive revision procedures later in life for the majority of children after a vaginoplasty is performed in infancy.1 The bimodal peaks seen in the ages at which children undergo reconstruction support that further longitudinal studies of redo procedure rates are needed.10

Although genitoplasty procedures are rare, our study finds that centralization of care has occurred to a certain extent with approximately two-thirds of procedures being performed by medium- and high-volume surgeons. An additional recommendation of the 2006 Consensus Statement was that only those surgeons experienced in the surgery of DSD should perform these procedures.1 This is supported by two long-term series that evaluated outcomes following reconstructive procedures performed by surgeons with a specific focus in treatment of DSD versus community surgeons.11 Lean et al found a significant difference, even with equivalent described technique, in cosmetic and functional outcomes.12 In light of these results, it is reassuring that most of the cases in the present study were performed by a medium- or high-volume surgeon.

CONCLUSIONS

Many girls with CAH did not proceed to early reconstructive surgery. Of those referred to surgeons, potentially the most virilized girls, about half proceeded to early surgery and almost all had vaginoplasty as a component of surgery. About two-thirds of procedures were performed by medium- or high- volume surgeons indicative of DSD surgical centralization.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hughes IA, Houk C, Ahmed SF, et al. Consensus statement on the management of intersex disorders. J Ped Urol. 2006;2:148. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marumudi E, Khadgawat R, Surana V, et al. Diagnosis and management of classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Steroids. 2013;78:741. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thyen U, Lanz K, Holterhus PM, et al. Epidemiology and Initial Management of Ambiguous Genitalia at Birth in Germany. Horm Res. 2006;66:195. doi: 10.1159/000094782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Creighton SM, Minto CL, Steele SJ. Objective Cosmetic and Anatomical Outcomes at Adolescence of Feminizing Surgery for Ambiguous Genitalia done in Childhood. Lancet. 2001;358:124. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05343-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yankovic F, Cherian A, Steven L, et al. Current practice in feminizing surgery for congenital adrenal hyperplasia; A specialist survey. J Ped Urol. 2013;9:1103. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michala L, Liao LM, Wood D, et al. Practice changes in childhood surgery for ambiguous genitalia? J Ped Urol. 2014:1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2014.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Group, J.L.E.C.W. Consensus Statement on 21-Hydroxylase Deficiency from The Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society and The European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology. JCEM. 2002;87:4048. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DaJusta D, Xu L, Baker L. Frequency of Feminizing Genitoplasty for Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia with the Geographical Distribution of Surgeries in the United States. AUA conference abstract. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jameson J, Kretser DD, Marshall JC, editors. Endocrinology Adult and Pediatric: Reproductive Endocrinology. 6 ed. Elsevier; Philadelphia, PA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krege S, Walz KH, Hauffa BP, et al. Long-term Follow-up of Female Patients with Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia from 21-hydroxylase Deficiency with Special Emphasis on Reuslts of Vaginoplasty. BJU Intl. 2000;86:253. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alizai NK, Thomas DF, Lilford RJ. Feminizing Genitoplasty for Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia: What Happens at Puberty? J Urol. 1999;161:1588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lean WL, Deshpande A, Hutson J, et al. Cosmetic and Anatomic Outcomes after Feminizing Surgery for Ambiguous Genitalia. J Ped Surg. 2005;40:1856. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]