Abstract

Skeletal muscle-specific liver kinase B1 (LKB1) knockout mice (skmLKB1-KO) exhibit elevated mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling after treadmill running. MAPK activation is also associated with inflammation-related signaling in skeletal muscle. Since exercise can induce muscle damage, and inflammation is a response triggered by damaged tissue, we therefore hypothesized that LKB1 plays an important role in dampening the inflammatory response to muscle contraction, and that this may be due in part to increased susceptibility to muscle damage with contractions in LKB1-deficient muscle. Here we studied the inflammatory response and muscle damage with in situ muscle contraction or downhill running. After in situ muscle contractions, the phosphorylation of both NF-κB and STAT3 was increased more in skmLKB1-KO vs. wild-type (WT) muscles. Analysis of gene expression via microarray and RT-PCR shows that expression of many inflammation-related genes increased after contraction only in skmLKB1-KO muscles. This was associated with mild skeletal muscle fiber membrane damage in skmLKB1-KO muscles. Gene markers of oxidative stress were also elevated in skmLKB1-KO muscles after contraction. Using the downhill running model, we observed significantly more muscle damage after running in skmLKB1-KO mice, and this was associated with greater phosphorylation of both Jnk and STAT3 and increased expression of SOCS3 and Fos. In conclusion, we have shown that the lack of LKB1 in skeletal muscle leads to an increased inflammatory state in skeletal muscle that is exacerbated by muscle contraction. Increased susceptibility of the muscle to damage may underlie part of this response.

Keywords: LKB1, inflammation, oxidative stress, downhill running, AMPK

liver kinase B1 (LKB1) is an important regulator of skeletal muscle metabolic function. It phosphorylates and activates members of the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) family. The best-defined of these targets are the α1 and α2 subunits of AMPK itself, but 11 other AMPK-related kinases are likewise phosphorylated by LKB1, although the role of these is poorly understood in skeletal muscle. AMPK is activated by LKB1 in working skeletal muscle and serves to promote catabolic processes that help maintain ATP availability, while decreasing ATP consumption. AMPK is also a well-established regulator of gene expression in skeletal muscle (33), and its activity increases the expression of many exercise-induced genes (18). While the roles played by the other AMPK family members in muscle have not been well studied, SNARK has been shown to affect glucose transport (23), MARK2 is involved in utrophin-dystroglycan and dystrophin interactions (54), ARK5 may suppress glucose uptake (15) and regulate muscle strength (53), and SIK1 appears to have prosurvival effects on muscle cells (3).

We recently showed that contraction-induced expression of several mitochondrial genes in skeletal muscle is dependent upon LKB1 (47). Despite the suppressed expression of these mitochondrial genes, we found that 2 h after muscle contractions, the phosphorylation of Erk was significantly elevated in muscles from skmLKB1-KO vs. those from littermate wild-type (WT) mice. The phosphorylation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) likewise tended to be elevated as well in the skmLKB1-KO muscles, although not significantly. Because the MAPK signaling cascades are also associated with oxidative stress and inflammation-related signaling responses (4, 13, 17, 24, 32, 42, 46), we subsequently questioned whether the lack of LKB1 would lead to an exaggerated stress response to contractions, which might partially explain the dysfunctional phenotype that is associated with skmLKB1-KO muscles (22, 40, 45, 47, 50).

Inflammation refers to a localized immune response to tissue injury or infection that leads to an accumulation and activation of immune cells (neutrophils, macrophages, etc.) that coordinate the clearance of damaged tissue and contribute to the healing process. Communication between the immune cells and the other cells that make up the inflamed tissue is accomplished through the secretion of many cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and IL-6. In skeletal muscle, the intracellular response to inflammation is stimulated by these cytokines (31) and is mediated by the activation of several downstream signaling proteins, including p38, Erk, jun kinase (JNK), and janus kinase (JAK). These pathways activate transcriptions factors including nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), activator protein-1 (AP-1; Jun/Fos), and signal transduction activator of transcription (STAT). Transcription is thus altered, leading to changes in the expression of many genes. Exercise or muscle contraction can lead to an acute skeletal muscle inflammatory response (9, 13, 24, 52), mediated at least in part by the generation of reactive oxygen species (14). In fact, NF-κB serves as a common signaling pathway in the response to both inflammation and oxidative stress, such that the inflammatory and oxidative damage responses are closely interrelated (17, 24). This response is necessary for proper adaptation to the exercise stimulus (2, 9, 24), including rapid resolution of the inflammation (34). However, if inflammatory signaling or oxidative stress is excessive or prolonged, it promotes muscle degeneration and dysfunction (6, 11, 24, 31). The role LKB1 may play in regulation of the intracellular signaling response to inflammation/oxidative stress is not currently understood.

Thus the purpose of this project was to assess the effect of LKB1 deficiency on inflammation/oxidative stress-related signaling pathways, downstream transcription factors, and inflammation-related gene expression in muscles after contractions. Our results suggest that LKB1 plays an important role in damping the inflammatory and oxidative responses to muscle contraction, and that this may be due in part to increased susceptibility to contraction-induced muscle damage in LKB1-deficient muscle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical approval.

All experimental procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Brigham Young University prior to experimentation.

Animal care and generation of knockout mice.

Male and female mice were bred and housed at 21-22°C with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle, on an ad libitum diet of standard chow. Skeletal muscle-specific LKB1 knockout mice were generated by crossing LKB1 conditional mice that express a “floxed” LKB1 gene flanked by LoxP sites (provided by R. DePinho and N. Bardeesy, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA) with myf6-Cre transgenic mice (12) heterozygously expressing Cre recombinase specifically in skeletal muscle under the Myf6 (MRF4) promoter (kindly provided by M. R. Capecchi, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT). The skeletal muscle-specific expression of Cre in mice with homozygously “floxed” LKB1 leads to recombination and deletion of the LKB1 gene specifically from skeletal muscle (skmLKB1-KO), as demonstrated previously (47). Herein, LKB1 conditional mice with transgenic “floxed” LKB1, but that lack Cre expression and thus retain LKB1 gene expression, are referred to as wild-type (WT) mice. Littermate WT mice served as controls. Genotyping was performed via polymerase chain reaction using primers for Cre and floxed LKB1 as described previously (51), and was verified by Western blotting for LKB1 as described below. Mice were 3–5 mo old at the time of experimentation.

Sciatic nerve stimulation.

Mice were anesthetized with 2–3% isoflurane in supplemental oxygen. The sciatic nerve was accessed through an incision in the lateral aspect of the left hindlimb and was stimulated at 0.5 pulses/s and 5-ms pulse duration for 15 min to produce contractions of the lower hindlimb musculature. Unstimulated muscles from the unoperated right hindlimb served as resting controls. The resting and stimulated gastrocnemius-plantaris-soleus complexes were removed 0, 2, or 3 h after the cessation of stimulation and clamp-frozen at the temperature of liquid nitrogen, or, in a subset of mice, the gastrocnemius muscle alone was frozen in isopentane chilled to the temperature of liquid nitrogen for histological examination. After stimulation, the incisions on the mice in the 2- and 3-h groups were closed with surgical staples, and the mice were maintained under isoflurane anesthesia until the designated time of tissue harvest. RNA and protein from some of these muscle samples were obtained and utilized for measures reported on previously (47) and have been utilized to assess novel measures as indicated below. A new and distinct cohort of mice was injected with 0.008 ml/g body wt 1% Evan's blue dye (EBD) in sterile PBS, pH 7.45, the evening prior to experimentation for assessment of sarcolemmal damage.

In a separate cohort of WT and KO mice (n = 6 mice/group), the sciatic nerve was isolated and stimulated as described above, but prior to stimulation the gastrocnemius tendon was attached to a muscle lever system (Aurora Scientific, model 305C) for the measurement of force production and fatigue during the contraction bout. The knee was fixed and optimal voltage was determined for each mouse by assessing contraction force at varying stimulation voltages, prior to initiation of the contraction protocol indicated above.

Downhill running.

Mice were injected with EBD the evening prior to running. Mice were run on a motorized treadmill (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH) with a −17° grade at 12 m/min. Mice ran in bouts of 5 min separated by 2-min rest periods for a total of 61 min. The rest periods were necessary because the skmLKB1-KO mice fatigue very quickly (47). Immediately after the running bout, the mice were anesthetized with 2–3% isoflurane in supplemental oxygen and quadriceps muscles were harvested and either frozen in liquid nitrogen for protein analysis, or in isopentane chilled to the temperature of liquid nitrogen for histological analysis.

Tissue homogenization.

Muscles were homogenized in 19 vols of homogenization buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4; 250 mm mannitol, 50 mm NaF, 5 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 50 mm B-glycerophosphate, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, 1 mm DTT, 1 mm benzamidine, 0.1 mm phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, 5 μg ml soybean trypsin inhibitor), then frozen at −90°C and thawed 3 times to ensure disruption of intracellular membranes. They were vortexed vigorously, centrifuged at 10,000 g for 20 min. The supernatants were analyzed for protein content (DC Protein Assay, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), then stored at −90°C for later analysis.

Western blotting.

Homogenates were diluted in sample buffer (125 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 20% glycerol, 4% SDS, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.01% bromphenol blue), then loaded on Tris-glycine gels (Bio-Rad Criterion System, Bio-Rad Laboratories). Proteins were separated at 200 V for 55 min. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes which were then probed for specific proteins via immunodetection using antibodies against the following proteins: phospho-NF-κB (no. 3033), total NF-κB (no. 8242), phospho-STAT3 (no. 9145), total-STAT3 (no. 9139), phospho-p38 MAPK (no. 4511) from Cell Signaling Technology, phospho-Jnk (no. 12882) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and LKB1 (no. 07–694) from EMD Millipore.

RNA isolation.

Gastrocnemius-soleus-plantaris muscles were ground to powder under liquid nitrogen. RNA was isolated from the powdered muscle using Trizol (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), then cleaned up with RNeasy columns (Qiagen) or Direct-zol RNA purification columns (Zymo Research) following the manufacturer's directions. RNA concentration and purity (260:280 ratio > 1.9) was assessed by spectrophotometry.

Microarray analysis.

Microarray experiments (MouseRef-8 v2.0 BeadChip, Illumina) were performed by the Genome Technology Access Center at Washington University, St. Louis, MO. Microarray data were analyzed using both the limma (version 3.1) and lumi (version 3.0) R packages in R (version 3.1.2). The data were background subtracted, normalized using Robust Spline Normalization (RSN), and then log2 transformed according to lumi best practices. We compared LKB1 expression values across the four groups (resting and stimulated controls, and resting and stimulated knockouts) and eliminated samples from 2 animals from further analysis because the measured LKB1 (Stk11) expression was inconsistent with the genotyping results by PCR.

To explore differentially expressed genes between stimulated and rest, we performed a differential expression analysis between stimulated and rest within wild types, and then a separate comparison within knockouts. The top 30 gene probes, ranked by P value, were retained for further analysis with a maximum P value of 0.01. We then clustered the data by gene using all genes from both differential expression analyses. Samples were grouped by genotype and stimulation status. Hypergeometric testing for over- and underrepresentation of biological process gene ontology terms was also performed between resting and stimulated muscles within each genotype, as well as between stimulated muscles from both genotypes. The significantly affected pathways (P ≤ 0.01) were ranked by P value. Microarray data have been made available at GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo), accession no. GSE72352.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR.

Synthesis of cDNA was performed from 500 ng RNA using iScript Reverse Transciption Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Real-time PCR was performed using KiCqStart SYBR Green qPCR ReadyMix (Sigma) or SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad), according to the manufacturer's instructions using a CFX96 real-time detection system (Bio-Rad). Primer sequences were designed for interleukin 1β (IL-1β), interleukin 6 (IL-6), suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), immediate early response 3 (IER3), B-cell lymphoma 3 (Bcl3), FBJ murine osteosarcoma (Fos), zinc finger protein 36 (Zfp36) using NetPrimer (Premier Biosoft). Design of oxidative stress primers [heme oxygenase 1 (Hmox1), heme oxygenase 2 (Hmox2), NADPH dehydrogenase quinone 1 (NQO1), aldehyde dehydrogenase 3A1 (ALDH3a1), and microsomal glutathione S-transferase 3 (mGST3)] was performed using OligoPerfect Designer tool (ThermoFisher Scientific). Sequence specificity was verified via Primer Blast (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/). Sequences of primers are shown in Table 1. Amplification efficiency was verified prior to experimentation and was between 90 and 105% for all primer sets. Melt curves analysis was also performed to verify the generation of a single transcript. Gene expression relative to WT REST was performed using the 2−ΔΔCt method using beta-actin for normalization.

Table 1.

RT-PCR primer sequences

| Primer | Direction | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | forward | 5′-TTCCCATTAGACAACTGC-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-GGATTCTTTACTTTGAGGC-3′ | |

| IL-6 | forward | 5′-CCAATTTCCAATGCTCTCCT-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-ACCACAGTGAGGAATGTCCA-3′ | |

| SOCS3 | forward | 5′-ATGGTCACCCACAGCAAGTTT-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-TCCAGTAGAATCCGCTCTCCT-3′ | |

| TNF-α | forward | 5′-CCCACGTCGTAGCAAACCAC-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-AAGGTACAACCCATCGGCTG-3′ | |

| IER3 | forward | 5′-GCCGAAGGGTGCTCTAC-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-CATAAATGGGCTCAGGTGT-3′ | |

| BclIII | forward | 5′-CCGGAGGCCCTTTACTACCA-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-GGAGTAGGGGTGAGTAGGCAG-3′ | |

| Fos | forward | 5′-CGGGTTTCAACGCCGACTA-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-TTGGCACTAGAGACGGACAGA-3′ | |

| ZFP36 | forward | 5′-TCTCTGCCATCTACGAGAGCC-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-CCAGTCAGGCGAGAGGTGA-3′ | |

| Hmox1 | forward | 5′-CACGCATATACCCGCTACCT-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-CCAGAGTGTTATTCGAGCA-3′ | |

| Hmox2 | forward | 5′-TACTCAGCCCTTGAGGAGGA-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-TCTGGCTCATTTTGCCCTAC-3′ | |

| NQO1 | forward | 5′-TTCTCTGGCCGATTCAGAGT-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-GGCTGCTTGGAGCAAAATAG-3′ | |

| ALDH3a1 | forward | 5′-ATGGGAGGATCATCAACGAC-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-TCATCCAAGCTTCGAACACA-3′ | |

| mGST3 | forward | 5′-CCTGAGAACGGGCATATGTT-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-CTCCTCGATACCGCTTGCTA-3′ |

Hematoxylin and eosin staining.

Ten-micrometer sections were cut from the muscle midbelly onto glass slides. Sections were cleared with Histo-clear II, dehydrated in ethanol, and stained with hematoxylin followed by eosin, dehydrated with ethanol, and cleared again with Histo-clear II. Slides were sealed with Cytoseal 280 and a coverslip, then imaged via microscopy. Fibers with centralized nuclei were counted using ImageJ, and expressed as a percentage of all fibers counted.

Evans blue dye imaging.

Ten-micrometer sections were cut from the muscle midbelly onto glass slides. Coverslips were mounted over the sections using Fluormount G (Southern Biotech), then red autofluorescence was imaged using microscopy and the Cy3 filter. EBD positive fibers were counted and expressed as the total number of positive fibers per muscle.

Statistics.

Statistical comparisons were performed using NCSS statistical software (Kaysville, UT). Data are presented as means ± SE. Statistical comparisons for the electrical stimulation experiments were performed by repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the stimulated vs. nonstimulated muscle as the repeated measure, and for downhill running experiments using general linear model 2 × 2 factorial ANOVA, with the significance level set at 0.05.

RESULTS

In situ fatigue resulting from twitch contractions is not increased in KO muscles.

Maximal specific force was not different between WT and KO muscles (1.30 ± 0.15 vs. 1.26 ± 0.14 g/mg muscle, respectively; Fig. 1A). Fatigue was likewise not significantly affected by genotype as assessed by the ratio of the final/maximal contraction (WT = 0.80 ± 0.03, KO = 0.72 ± 0.07; Fig. 1B), or as percentage of initial force (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, the contraction bout itself did not produce significant fatigue in either genotype (Fig. 1, B and C), which was not unexpected as the contraction bout was very mild, using only twitch contractions.

Fig. 1.

Force and fatigue characteristics of in situ skeletal muscle contraction bout. The sciatic nerve was isolated in wild-type (WT) and littermate skeletal muscle-specific LKB1-knockout (KO) mice, and the gastrocnemius tendon was attached to a muscle lever system for force measurement. After the optimal voltage for maximal force production was determined, a contraction bout was elicited for 15 min at 0.5 pulses/s and 5 ms/pulse while recording force production. Maximal force production for each mouse was recorded (A). Fatigue was measured as the force production for the final contraction/maximal contraction (B) and for each contraction as the percentage of initial force (C). n = 6/group.

LKB1 knock-out increases contraction-induced inflammatory response in skeletal muscle.

STAT3 and NF-κB are both transcription factors that are activated by inflammatory stimuli, and are important in the inflammation response. STAT3 is activated by phosphorylation at Tyr705. Phosphorylation of the p65 subunit of NF-κB at Ser536 by IKK results in increased transcriptional activity without altering recruitment to response elements in the promoter region (41).

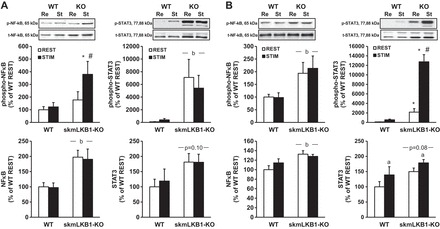

Immediately after 15 min of sciatic nerve stimulation, phospho-NF-κB increased 114% in skmLKB1-KO muscles but was not significantly different in WT muscles (Fig. 2A). This effect was short-lived, however, as 2 h after contraction, NF-κB phosphorylation had returned to resting levels in the skmLKB1-KO muscles (Fig. 2B). However, a main effect of genotype was observed at this time point with phospho-NF-κB levels being approximately twice those in skmLKB1-KO vs. WT muscles. This elevation in basal NF-κB phosphorylation in skmLKB1-KO muscles was likely due in part to elevated NF-κB protein levels, which were significantly elevated (main effect) in skmLKB1-KO muscles at both 0 and 2 h postcontraction (Fig. 2, A and B).

Fig. 2.

Phosphorylation of proinflammatory transcription factors is increased in LKB1-deficient muscles 0 and 2 h after in situ skeletal muscle contractions. Western blotting was performed using protein from WT and skeletal muscle-specific LKB1-knockout (skmLKB1-KO or KO) muscles immediately or 2 h after a 15-min in situ contraction bout. A: content of phosphorylated and total NF-κB and STAT-3 protein in gastrocnemius muscles immediately after a 15-min bout of electrically stimulated contractions. B: content of phosphorylated and total NF-κB and STAT-3 protein in gastrocnemius muscles 2 h after a 15-min bout of electrically stimulated contractions. Re, resting muscles; St, stimulated muscles. n = 8/group. *Significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) vs. corresponding REST group. #Significant difference vs. corresponding WT group. aMain effect of stimulation. bMain effect of genotype.

Phosphorylation of STAT3, in contrast to NF-κB, was not immediately affected by stimulation, but was elevated in skmLKB1-KO muscles, regardless of contraction status (Fig. 2A). However, 2 h after stimulation, phospho-STAT3 was again elevated in the resting skmLKB1-KO vs. WT muscles, but also increased substantially in the stimulated skmLKB1-KO but not WT muscles (Fig. 2B). Similar to NF-κB, total STAT3 protein concentration tended to be higher in skmLKB1-KO muscles at both time points, regardless of contraction status, although this difference was not significant (Fig. 2, A and B). At 2 h poststimulation, stimulation induced a significant increase in STAT3 levels in both WT and skmLKB1-KO muscles (Fig. 2B).

LKB1 knock-out increases inflammation and oxidative stress-related gene expression after muscle contraction.

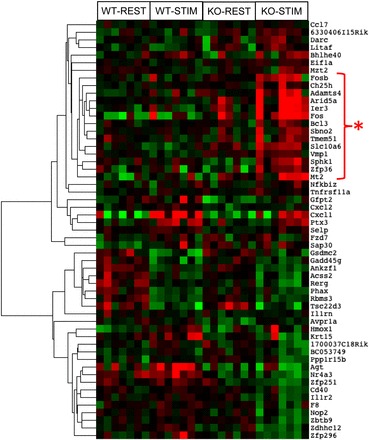

As both NF-κB and STAT3 promote inflammation-related gene expression, we performed a microarray analysis of RNA from resting and stimulated muscles from skmLKB1-KO and WT mice 3 h after the 15-min sciatic nerve stimulation bout. Since our primary objective in this study was to determine whether the lack of LKB1 would exacerbate inflammatory signaling in response to muscle stimulation, the difference between gene expression in STIM and REST muscles within each mouse was calculated and then cluster analysis was performed on the top 30 gene responders within each genotype. As illustrated in Fig. 3, a cluster of 14 genes was clearly induced by contraction in the skmLKB1-KO but not WT muscles. Of these 14 genes, 12 are known in the literature either to be induced by NF-κB or by other inflammatory stimuli. Comparison of GO processes in stimulated muscles of WT and KO mice indicated altered gene expression in 295 biological processes. As expected, 6 of the top 10 processes were related to metabolism, while 3 of the other top processes that were different between genotypes were related to stress, and specifically, oxidative stress (see Table 2).

Fig. 3.

A cluster of inflammation/NF-κB-regulated genes is upregulated in LKB1-deficient muscles after in situ skeletal muscle contractions. Microarray analysis was performed using RNA that was isolated from WT and skeletal muscle-specific LKB1-knockout (KO) muscles 3 h after a 15-min in situ contraction bout. Cluster analysis of the top genes differentially expressed with muscle contraction was performed. Increasing intensity of red and green colors indicates the degree of higher and lower gene expression, respectively. n = 6/group. *Cluster of genes whose expression is elevated in KO but not WT after muscle contractions.

Table 2.

GO terms overrepresented in KO vs. WT muscles following contraction, ranked by P value

| Rank | ID | Term | Pl | n Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GO:0008152 | Metabolic process | 1.23E-07 | 132 |

| 2 | GO:0044710 | Single-organism metabolic process | 6.25E-07 | 69 |

| 3 | GO:0006950 | Response to stress | 8.80E-07 | 47 |

| 4 | GO:0044237 | Cellular metabolic process | 9.25E-07 | 115 |

| 5 | GO:0006979 | Response to oxidative stress | 1.11E-06 | 12 |

| 6 | GO:0009987 | Cellular process | 4.74E-06 | 167 |

| 7 | GO:0035556 | Intracellular signal transduction | 7.28E-06 | 37 |

| 8 | GO:0071704 | Organic substance metabolic process | 1.37E-05 | 116 |

| 9 | GO:0006793 | Phosphorus metabolic process | 1.39E-05 | 49 |

| 10 | GO:0055114 | Oxidation-reduction process | 1.93E-05 | 25 |

| 11 | GO:0016265 | Death | 2.16E-05 | 33 |

| 12 | GO:0010941 | Regulation of cell death | 2.34E-05 | 29 |

| 13 | GO:0051179 | Localization | 2.36E-05 | 71 |

| 14 | GO:0055013 | Cardiac muscle cell development | 2.41E-05 | 5 |

| 15 | GO:0016477 | Cell migration | 2.42E-05 | 21 |

| 16 | GO:0010940 | Positive regulation of necrotic cell death | 2.45E-05 | 2 |

| 17 | GO:0044699 | Single-organism process | 2.56E-05 | 154 |

| 18 | GO:0040011 | Locomotion | 3.03E-05 | 26 |

| 19 | GO:0055002 | Striated muscle cell development | 3.45E-05 | 8 |

| 20 | GO:0061061 | Muscle structure development | 3.51E-05 | 15 |

KO, skeletal muscle-specific liver kinase B1 (LKB1) knockout mice; WT, wild-type littermates.

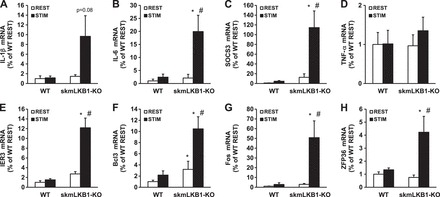

Contraction-induced expression of inflammation-related genes is elevated in LKB1-KO muscle.

To verify the results of the microarray analysis, we performed RT-PCR to assess gene expression for 4 of the inflammation-related genes identified by microarray analysis, IER3 (Fig. 4E), Bcl3 (Fig. 4F), Fos (Fig. 4G), and ZFP36 (Fig. 4H). In addition, we also used RT-PCR to analyze four classic inflammatory genes that are induced through NF-κB signaling: IL-1β (Fig. 4A), IL-6 (Fig. 4B), SOCS3 (Fig. 4C), and TNF-α (Fig. 4D). IER3 is a predictive marker for inflammation diseases (1). Fos is another well-known transcription factor that mediates many aspects of the negative-feedback response to inflammation and oxidative stress and can suppress NF-κB activity (39). Bcl3 can regulate proinflammatory gene expression (7). ZFP36 also has anti-inflammatory effects (56). IL-6 can act as both a proinflammatory cytokine and an anti-inflammatory myokine (44). NF-κB, as a transcription factor, regulates IL-6 transcription (32), and IL-6 can influence STAT3 activity (37). IL-1β is a proinflammatory cytokine that activates NF-κB (32). Gene expression of SOCS3 can be induced by IL-6, and SOCS3 can then inhibit, in part, IL-6 function (37). TNF-α is another cytokine that plays a key proinflammatory role via NF-κB activation (29).

Fig. 4.

RT-PCR measurement of inflammation-related gene expression after in situ muscle contractions. A–I: RT-PCR was performed using primers for the indicated genes and RNA that was isolated from rested (REST) or stimulated (STIM) gastrocnemius muscles from WT and skeletal muscle specific LKB1-knockout (KO) mice 3 h after contractions induced by unilateral electrical stimulation of the sciatic nerve. n = 6/group. *Significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) vs. corresponding WT group. #Significant difference vs. corresponding REST group.

Three hours after stimulation, IL-6, SOCS3, IER3, Fos, and ZFP36 mRNA content was increased between 20- and 120-fold in stimulated skmLKB1-KO but not WT muscle. Bcl3 also increased in skmLKB1-KO muscles with stimulation, but was also elevated basally in skmLKB1-KO muscles. IL-1β also tended (P = 0.08) to increase in skmLKB1-KO muscles with stimulation, but this was not significant. TNF-α expression was not affected by genotype or treatment. Thus the lack of LKB1 results in hyperexpression of inflammation-induced genes.

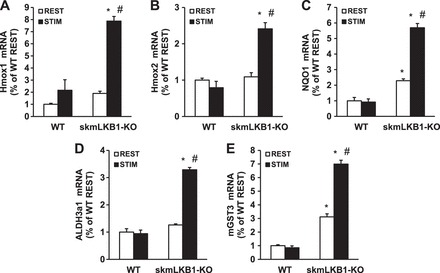

Contraction-induced expression of oxidative stress response genes is elevated in LKB1-knockout muscle.

GO-term analysis indicated that oxidative-stress related processes were elevated in skmLKB1-KO vs. WT muscles after contraction. To confirm this, RT-PCR analysis of five oxidative stress-related genes (3 from the GO-term analysis and 2 other well-characterized oxidative stress markers) was performed. Expression of Hmox1 (Fig. 5A), Hmox2 (Fig. 5B), NQO1 (Fig. 5C), ALDH3a1 (Fig. 5D), and mGST3 (Fig. 5E) were all elevated in skmLKB1-KO vs. WT muscles after contraction. NQO1 and mGST3 were also elevated in resting skmLKB1-KO vs. WT muscles.

Fig. 5.

A–E: RT-PCR measurement of oxidative stress-induced genes after in situ muscle contractions. RT-PCR was performed for the indicated genes using RNA that was isolated from rested (REST) or stimulated (STIM) gastrocnemius muscles from WT and skeletal muscle-specific LKB1-knockout (KO) mice 3 h after contractions induced by unilateral electrical stimulation of the sciatic nerve. n = 3–4/group. *Significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) vs. corresponding WT group. #Significant difference vs. corresponding REST group.

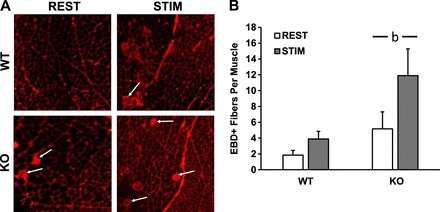

Muscle damage is mildly elevated in skmLKB1-KO muscles regardless of contraction status (REST vs STIM).

To determine whether the observed hyperresponse of inflammation-related signaling and gene expression in skmLKB1-KO muscles could be due to increased muscle damage with contraction, mice were injected with Evans blue dye prior to the sciatic nerve stimulation to assess membrane integrity. A main effect of genotype was observed, with the skmLKB1-KO muscles having significantly more EBD+ fibers than WT muscles (5.2 ± 2.2 vs. 1.9 ± 0.6 at rest, and 11.9 ± 3.4 vs. 3.9 ± 1.0 after contractions, Fig. 6B). Also, contraction tended to increase the number of EBD fibers as well, but this was not significant (P = 0.09). Therefore, skmLKB1-KO results in mildly elevated muscle membrane damage, regardless of electrically stimulated muscle contractions.

Fig. 6.

Muscle damage is mildly elevated in LKB1-deficient muscles after in situ contractions. Mice were injected with Evans blue dye (EBD) after which a 15-min bout of in situ muscle contractions was performed. Gastrocnemius muscles were removed immediately after the contraction bout. Detection of EBD-positive (EBD+) cells was performed via fluorescence microscopy. A: representative images of muscle sections from WT and skeletal muscle-specific LKB1 knockout (KO) muscles. Arrows indicate EBD+ fibers. B: average number of EBD+ fibers in whole gastrocnemius (GASTROC) muscle from WT and skmLKB1-KO muscles. n size = 6/group. bMain effect of genotype.

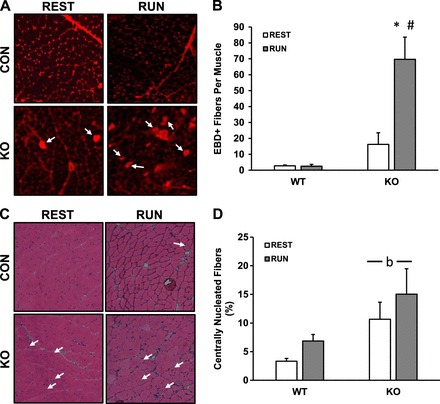

LKB1 knockout results in muscle membrane damage after downhill running.

To further assess the muscle damage response in a more physiologically relevant exercise model, we subjected the mice to a downhill treadmill running protocol, again using EBD to assess muscle membrane integrity as well as centralized nuclei to assess muscle regeneration/repair. EBD-positive fibers tended to be elevated in resting skmLKB1-KO muscles, but this was not significant. However, downhill running strongly increased EBD-positive fibers immediately after exercise in skmLKB1-KO, but not WT quadriceps muscles (Fig. 7, A and B). Five days after downhill running, centralized nuclei were elevated in skmLKB1-KO muscles regardless of running status (Fig. 7, C and D).

Fig. 7.

Downhill running leads to muscle damage in LKB1-deficient skeletal muscle. WT and skeletal muscle-specific LKB1 knockout (KO) mice were injected with EBD and then allowed normal cage activity (REST) or run downhill intermittently for 1 h (RUN). Immediately (A and B; n = 8–9/group) or at 5 days (C and D; n = 5–9/group) quadriceps muscles were collected and analyzed for EBD positive (EBD+) cells (A and B), or for centrally nucleated muscle fibers via hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (C and D). A: representative images of EBD+ fibers in muscles from WT and KO mice after REST or RUN. Arrows indicate EBD+ fibers. B: average EBD+ fibers per quadriceps muscle. C: representative H&E stains of muscles from WT and KO mice after REST or RUN. Arrows indicated fibers with centrally localized nuclei. D: average percentage of centrally nucleated muscle fibers. *Significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) vs. corresponding REST group. #Significant difference vs. corresponding WT group. bMain effect of genotype.

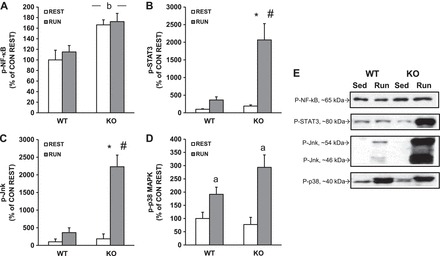

Inflammatory signaling is increased in skmLKB1-KO muscles after downhill running.

To determine whether downhill running increased inflammatory signaling, we measured phosphorylation of NF-κB, STAT3, Jnk, and p38/MAPK, all of which can contribute to the inflammatory response. NF-κB phosphorylation (Ser 536) was increased in skmLKB1-KO muscles regardless of running status, but was unaffected by running in either genotype (Fig. 8, A and E). STAT3 (Tyr705) and Jnk (Thr183/Tyr185) phosphorylation, on the other hand, was strongly induced by downhill running in skmLKB1-KO, but not WT muscles (Fig. 8, B, C, and E). Phosphorylation of p38 (Thr180/Tyr182) was induced by running in both genotypes, with no genotype-dependent differences (Fig. 8, D and E).

Fig. 8.

STAT-3 and Jnk are hyperphosphorylated after downhill running in LKB1-deficient muscles. WT and skeletal muscle-specific LKB1 knockout (KO) mice were allowed normal cage activity (REST) or run downhill intermittently for 1 h (RUN). Quadriceps muscles were removed immediately after running, and proteins were analyzed for phosphorylated NF-κB (A, E), STAT-3 (B, E), Jnk (C, E), and p38 (D, E) via Western blotting. n = 5–6/group. *Significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) vs. corresponding REST group. #Significant difference vs. corresponding WT group. aMain effect of running. bMain effect of genotype.

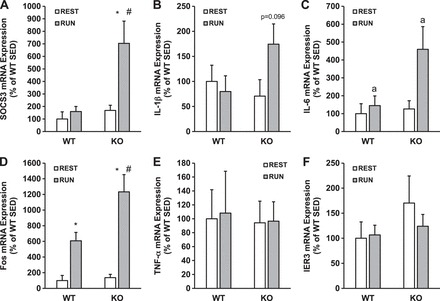

Inflammation-related gene expression changes in LKB1-KO muscle after downhill running.

To determine how the expression of inflammation-related genes changes after downhill running, we performed RT-PCR for IL-6, TNF-α, SOCS3, IL-1β, Fos, and IER3 immediately after the hour-long running bout. After running, SOCS3 expression was induced by running in skmLKB1-KO, but not WT muscles (Fig. 9A). A similar, nonsignificant trend was observed for IL-1β (P = 0.096; Fig. 9B). IL-6 expression was induced by running in both genotypes, although this main effect seemed to be driven primarily by the increase in the skmLKB1-KO muscles (Fig. 9C). Fos expression was induced by running in both genotypes, but the response was about twice as great in the skmLKB1-KO muscles compared with WT (Fig. 9D). TNF-α and IER3 expression were unaffected by genotype or running (Fig. 9, E and F).

Fig. 9.

Expression of inflammation-related genes is elevated in LKB1-deficient muscle after downhill running. WT and skeletal muscle-specific LKB1 knockout (KO) mice were left resting in their cages (REST) or run downhill intermittently for 1 h (RUN). Quadricep muscles were removed immediately after running, and gene expression was analyzed for IL-6 (A), TNF-α (B), SOCS3 (C), IL-1β (D), Fos (E), and IER3 (F) via RT-PCR. n = 5–6/group. *Significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) vs. corresponding REST group. #Significant difference vs. corresponding WT group. aMain effect of running.

DISCUSSION

We recently published data showing that contraction-induced phosphorylation of extracellular-signal regulated kinase (Erk) and possibly p38 MAPK (p38) is prolonged in skmLKB1-KO mice vs. WT controls (47). Erk and p38 MAPK are both known activators of NF-κB in skeletal muscle (13), which suggests that LKB1 may play an important role in controlling NF-κB-mediated inflammation and oxidative stress-related signaling in skeletal muscle after exercise. To test this hypothesis, we examined the activation of NF-κB as well as STAT3, another inflammation-induced transcription factor, along with expression of inflammation and oxidative stress-induced genes after an in situ contraction bout and after downhill running in skmLKB1-KO mice. Here we have shown that LKB1 ablation in skeletal muscle results in hyperactivation of these signaling factors and gene expression after muscle contractions and downhill running, and this is likely due in part to an increased susceptibility to contraction-induced muscle damage in the skmLKB1-KO mice.

The adaptive response of skeletal muscle to exercise and/or damage relies heavily upon appropriate activation of inflammation and associated intramuscular signaling pathways. Too little or too much oxidative stress and inflammatory signaling can result in impairments in muscle adaptation or repair (21, 35, 38) and must therefore be closely regulated. We found that a brief electrically stimulated in situ contraction bout led to an excessive inflammatory response and expression of markers associated with the response to oxidative stress in skmLKB1-KO muscles compared with WT muscles.

Phosphorylation of NF-κB and STAT3 (both major regulators of inflammation-induced gene expression) increased more after stimulation in skmLKB1-KO than in WT mice. NF-kB and STAT3 cooperate synergistically in the transcriptional control of many targets influenced by inflammation, including antiapoptotic, cell-cycle control, and cytokine genes. The promoters of many of these genes have response elements for both factors, and furthermore, unphosphorylated STAT3 physically interacts with NF-κB, facilitating its nuclear translocation and enhancing gene transcription (55). STAT3 also mediates the acetylation and nuclear retention of NF-κB (27). Accordingly, microarray analysis showed upregulation of gene expression for a set of inflammation-linked genes with contraction in skmLKB1-KO but not WT mice, and this was verified by RT-PCR analysis. We also measured gene expression of the well-characterized inflammatory target genes IL-1β, IL-6, SOCS3, and TNF-α, all of which increased with the exception of TNF-α. Thus contraction led to an excessive inflammatory signaling response in skmLKB1-KO vs. WT muscle. This increase in inflammatory gene expression cannot be linked to increased relative contraction intensity during this mild contraction bout in the KO mice, as the force curves for both genotypes were similar (Fig. 1C). This is in contrast to our previous work where KO muscles fatigued more rapidly than WT muscles using a much more intense tetanic contraction protocol (47).

Previous research has shown the potential for direct suppression of the inflammatory response by LKB1 and its downstream targets. LKB1's best-characterized target, AMPK, can suppress saturated fatty acid-induced NF-κB activity in skeletal muscle (42), and also decreases NF-κB activity in myocytes from obese individuals to levels observed in myocytes from lean individuals (10). In macrophages, AMPK α1 knockout prevents the normal transition from proinflammatory M1 to anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages after muscle injury (36), and AMPK β1 subunit knockout decreased inflammatory markers in macrophages, as did inhibition of fatty acid oxidation (8), suggesting that AMPK may control inflammation in macrophages by promoting fat oxidation. Since we showed that LKB1 knockout likewise leads to decreased fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscle (16, 49), this may likewise play a role in the increased inflammatory markers that we observed here. Salt-inducible kinase 3 (SIK3) and sucrose non-fermenting-related kinase (SNRK), both additional AMPK family members that lie downstream of LKB1, likewise appear to have anti-inflammatory effects on macrophages and adipocytes, respectively (28, 43). Interestingly, LKB1 itself can bind to and suppress inhibitor of NF-κB (IκB) kinase (IKK), leading to increased IκB stability, and therefore decreased NF-κB nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity (30). Thus the exaggerated inflammatory signaling and gene expression that we observed in skmLKB1-KO muscle after contractions is likely due, at least in part, to direct effects of LKB1 and its downstream kinases.

Comparison of overrepresented gene ontology (GO) biological processes in stimulated KO vs. WT muscles showed that many of the most affected processes were related to metabolism. This was to be expected based on previous studies (16, 22, 40, 47, 49–51) where mitochondrial and metabolic defects were observed in LKB1-KO muscles. Although “inflammatory response” processes were not among those most affected by the KO, processes involved in oxidative stress response were highly overrepresented based on the GO term analysis. That metabolic and oxidative stress-related processes are both heavily affected in the LKB1-KO muscles is consistent with the role of mitochondrial deficiency on reactive oxygen species generation (19). This is also consistent with the elevated expression of inflammatory genes observed in the cluster analysis. Indeed, oxidative stress activates NF-κB, and therefore the response to oxidative stress is similar in many respects to the inflammatory response (24).

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is activated during periods of oxidative stress through a complex redox shift-sensing mechanism and can upregulate many genes that help to manage oxidative stress and return the basal oxidative tone of the cell back to homeostatic conditions. All five of the oxidative stress response genes measured here are regulated by the transcription factor Nrf2, and Hmox1 and NQO1 in particular are hallmark genes regulated by Nrf2 activation (25). Previous work shows that loss of LKB1 results in increased activation of Nrf2 and would lead to an increase in Nrf2-related gene expression (20), including Hmox1 and NQO1. The data we have here support these previous findings but also suggest that during exercise, LKB1 is important in the regulation of antioxidative pathways in skeletal muscle to abrogate exercise-induced oxidative damage.

It is also possible that part of the hyperinflammatory response in skmLKB1-KO muscles was secondary to tissue/cell damage. Shan et al. (45) previously reported substantial muscle damage and regeneration in untreated muscles from skeletal muscle specific LKB1 knockout mice. The degree of damage and regeneration reported in that study was much more extensive than observed in our mice. This may be due to an earlier onset of LKB1 disruption during muscle development as they used the MyoD promoter to drive LKB1 excision, rather than the Myf6 promoter that was used in our mice (45). AMPK likely plays a role in muscle integrity since similar evidence for muscle damage and regeneration has been reported in muscle-specific AMPK knockout mice (5, 48), and potentially linked to defects in autophagy and/or vascularity of the muscle. Here, we observed a main effect for increased EBD positive fibers in resting and stimulated skmLKB1-KO muscles, with a trend for an increased number of damaged fibers after stimulation. However, the increase in damaged fiber number in our skmLKB1-KO mice after contraction only represented a very small fraction of the total number of muscle fibers in the gastrocnemius (∼10 damaged fibers of ∼5,000 fibers in the whole gastrocnemius). It is therefore not likely that the fiber damage alone accounts for the increase in inflammatory signaling in the KO muscle and suggests that the lack of LKB1 is likely exacerbating inflammatory signaling independent of the muscle damage itself.

Nonetheless, we determined whether skmLKB1-KO muscle is more prone to contraction-induced damage using a more physiologically relevant form of contractions by running the mice downhill. We used a very mild bout of downhill running because the skmLKB1-KO mice fatigue very quickly with treadmill running (47). In preliminary experiments we found that the skmLKB1-KO mice were unable to sustain running downhill for more than ∼10 min even at only 12 m/min and a −17° grade. Therefore we ran the mice for 5-min bouts with 2-min rest periods between bouts. The skmLKB1-KO mice were able to sustain this running protocol for a full hour, although they almost universally required substantial prodding with a brush to do so. While this downhill running protocol produced no significant damage in the WT mice, we observed a clear increase in EBD-positive fibers in the quadriceps muscles immediately after running in the skmLKB1-KO mice. Centrally localized nuclei were also elevated in the skmLKB1-KO quadriceps, although running had no significant effect on this 5 days postexercise. STAT3 and Jnk phosphorylation were both increased more in the KO vs. WT muscle immediately after the running bout, as was gene expression for SOCS3, IL-6, and Fos. It is possible that expression of the other inflammation-related genes might be affected at a later time point. The susceptibility to damage in the skmLKB1-KO muscles is likely mediated at least in part by AMPK since skeletal muscle from AMPK α1/α2 double knockout mice have an elevated number of fibers with centrally located nuclei as well as increased gene expression of IL-6, suggesting that the muscle is prone to damage and subsequent regeneration (26). The role of other LKB1 targets in cell integrity is unknown, but MARK2, an AMPK-related kinase also phosphorylated and activated by LKB1, has been shown to regulate interaction between dystrophin and utrophin (54). Impaired MARK2 activity could be an important defect contributing to the apparent susceptibility of skmLKB1-KO muscle cells to damage. It should be kept in mind that the increased damage observed in the KO muscles could be due in part to the increased relative intensity of the treadmill running bout (the running was near maximal capacity for the KO but not the WT mice). However, since the foremost reason for the downhill running experiment was to assess inflammatory response in relation to susceptibility to muscle membrane damage, we kept the overall physical strain on the whole muscle consistent between genotypes. Since the genotypes were of similar weight, and the distance run was identical, the strain on the muscles was likely similar, although uncharacterized biomechanical factors could contribute as well to the strain. Our results suggest that while the KO mice in our study may or may not have been limited metabolically in their running, it is likely that the KO mice were actually limited in their running partly by muscle damage and subsequent inflammation.

In conclusion, we have shown that the lack of LKB1 in skeletal muscle leads to an increased inflammatory and oxidative stress response after muscle contraction. Increased susceptibility of the muscle to damage may underlie at least part of this response, and suggests that targeting LKB1 and/or its downstream targets may lead to improved treatment for chronic inflammatory and degenerative skeletal muscle conditions.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Grant R01-AR-051928 (D. M. Thomson) and Mentoring Environment Grants from Brigham Young University (D. M. Thomson).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: T.C., T.M.M., M.T.E., C.R.H., J.S.K., and D.M.T. conception and design of research; T.C., T.M.M., N.L.M., S.R.M., D.M.H., A.M.H., R.E.C., R.P.M., C.R.H., J.M.H., and D.M.T. performed experiments; T.C., T.M.M., M.T.E., N.L.M., S.R.M., D.M.H., A.M.H., R.E.C., R.P.M., C.R.H., J.M.H., J.S.K., and D.M.T. analyzed data; T.C., T.M.M., M.T.E., N.L.M., S.R.M., R.E.C., R.P.M., C.R.H., J.M.H., J.S.K., and D.M.T. interpreted results of experiments; T.C. and D.M.T. drafted manuscript; T.C., T.M.M., M.T.E., C.R.H., J.M.H., and D.M.T. edited and revised manuscript; T.C., T.M.M., M.T.E., N.L.M., S.R.M., D.M.H., A.M.H., R.E.C., R.P.M., C.R.H., J.M.H., J.S.K., and D.M.T. approved final version of manuscript; M.T.E., N.L.M., R.P.M., J.M.H., and D.M.T. prepared figures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arlt A, Schafer H. Role of the immediate early response 3 (IER3) gene in cellular stress response, inflammation and tumorigenesis. Eur J Cell Biol 90: 545–552, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Begue G, Douillard A, Galbes O, Rossano B, Vernus B, Candau R, Py G. Early activation of rat skeletal muscle IL-6/STAT1/STAT3 dependent gene expression in resistance exercise linked to hypertrophy. PLos One 8: e57141, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berdeaux R, Goebel N, Banaszynski L, Takemori H, Wandless T, Shelton GD, Montminy M. SIK1 is a class II HDAC kinase that promotes survival of skeletal myocytes. Nat Med 13: 597–603, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown AE, Palsgaard J, Borup R, Avery P, Gunn DA, De Meyts P, Yeaman SJ, Walker M. p38 MAPK activation upregulates proinflammatory pathways in skeletal muscle cells from insulin-resistant type 2 diabetic patients. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 308: E63–E70, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bujak AL, Crane JD, Lally JS, Ford RJ, Kang SJ, Rebalka IA, Green AE, Kemp BE, Hawke TJ, Schertzer JD, Steinberg GR. AMPK activation of muscle autophagy prevents fasting-induced hypoglycemia and myopathy during aging. Cell Metab 21: 883–890, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai D, Frantz JD, Tawa NE Jr, Melendez PA, Oh BC, Lidov HG, Hasselgren PO, Frontera WR, Lee J, Glass DJ, and Shoelson SE. IKKbeta/NF-kappaB activation causes severe muscle wasting in mice. Cell 119: 285–298, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang TP, Vancurova I. Bcl3 regulates pro-survival and pro-inflammatory gene expression in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Biochim Biophys Acta 1843: 2620–2630, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galic S, Fullerton MD, Schertzer JD, Sikkema S, Marcinko K, Walkley CR, Izon D, Honeyman J, Chen ZP, van Denderen BJ, Kemp BE, Steinberg GR. Hematopoietic AMPK beta1 reduces mouse adipose tissue macrophage inflammation and insulin resistance in obesity. J Clin Invest 121: 4903–4915, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gomez-Cabrera MC, Borras C, Pallardo FV, Sastre J, Ji LL, Vina J. Decreasing xanthine oxidase-mediated oxidative stress prevents useful cellular adaptations to exercise in rats. J Physiol 567: 113–120, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green CJ, Pedersen M, Pedersen BK, Scheele C. Elevated NF-kappaB activation is conserved in human myocytes cultured from obese type 2 diabetic patients and attenuated by AMP-activated protein kinase. Diabetes 60: 2810–2819, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haddad F, Zaldivar F, Cooper DM, Adams GR. IL-6-induced skeletal muscle atrophy. J Appl Physiol 98: 911–917, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haldar M, Hancock JD, Coffin CM, Lessnick SL, Capecchi MR. A conditional mouse model of synovial sarcoma: insights into a myogenic origin. Cancer Cell 11: 375–388, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho RC, Hirshman MF, Li Y, Cai D, Farmer JR, Aschenbach WG, Witczak CA, Shoelson SE, Goodyear LJ. Regulation of IkappaB kinase and NF-kappaB in contracting adult rat skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 289: C794–C801, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hollander J, Fiebig R, Gore M, Ookawara T, Ohno H, Ji LL. Superoxide dismutase gene expression is activated by a single bout of exercise in rat skeletal muscle. Pflügers Arch 442: 426–434, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inazuka F, Sugiyama N, Tomita M, Abe T, Shioi G, Esumi H. Muscle-specific knock-out of NUAK family SNF1-like kinase 1 (NUAK1) prevents high fat diet-induced glucose intolerance. J Biol Chem 287: 16379–16389, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeppesen J, Maarbjerg SJ, Jordy AB, Fritzen AM, Pehmoller C, Sylow L, Serup AK, Jessen N, Thorsen K, Prats C, Qvortrup K, Dyck JR, Hunter RW, Sakamoto K, Thomson DM, Schjerling P, Wojtaszewski JF, Richter EA, Kiens B. LKB1 regulates lipid oxidation during exercise independently of AMPK. Diabetes 62: 1490–1499, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ji LL, Gomez-Cabrera MC, Steinhafel N, Vina J. Acute exercise activates nuclear factor (NF)-kappaB signaling pathway in rat skeletal muscle. FASEB J 18: 1499–1506, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jorgensen SB, Jensen TE, Richter EA. Role of AMPK in skeletal muscle gene adaptation in relation to exercise. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 32: 904–911, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joseph AM, Adhihetty PJ, Leeuwenburgh C. Beneficial effects of exercise on age-related mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in skeletal muscle. J Physiol 2015 Oct 27. doi: 10.1113/JP270659 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaufman JM, Amann JM, Park K, Arasada RR, Li H, Shyr Y, Carbone DP. LKB1 Loss induces characteristic patterns of gene expression in human tumors associated with NRF2 activation and attenuation of PI3K-AKT. J Thorac Oncol 9: 794–804, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kharraz Y, Guerra J, Mann CJ, Serrano AL, Munoz-Canoves P. Macrophage plasticity and the role of inflammation in skeletal muscle repair. Mediators Inflamm 2013: 491497, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koh HJ, Arnolds DE, Fujii N, Tran TT, Rogers MJ, Jessen N, Li Y, Liew CW, Ho RC, Hirshman MF, Kulkarni RN, Kahn CR, Goodyear LJ. Skeletal muscle-selective knockout of LKB1 increases insulin sensitivity, improves glucose homeostasis, and decreases TRB3. Mol Cell Biol 26: 8217–8227, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koh HJ, Toyoda T, Fujii N, Jung MM, Rathod A, Middelbeek RJ, Lessard SJ, Treebak JT, Tsuchihara K, Esumi H, Richter EA, Wojtaszewski JF, Hirshman MF, Goodyear LJ. Sucrose nonfermenting AMPK-related kinase (SNARK) mediates contraction-stimulated glucose transport in mouse skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 15541–15546, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kramer HF, Goodyear LJ. Exercise, MAPK, and NF-kappaB signaling in skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 103: 388–395, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwak MK, Itoh K, Yamamoto M, Sutter TR, Kensler TW. Role of transcription factor Nrf2 in the induction of hepatic phase 2 and antioxidative enzymes in vivo by the cancer chemoprotective agent, 3H-1,2-dimethiole-3-thione. Mol Med 7: 135–145, 2001. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lantier L, Fentz J, Mounier R, Leclerc J, Treebak JT, Pehmoller C, Sanz N, Sakakibara I, Saint-Amand E, Rimbaud S, Maire P, Marette A, Ventura-Clapier R, Ferry A, Wojtaszewski JF, Foretz M, Viollet B. AMPK controls exercise endurance, mitochondrial oxidative capacity, and skeletal muscle integrity. FASEB J 28: 3211–3224, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee H, Herrmann A, Deng JH, Kujawski M, Niu G, Li Z, Forman S, Jove R, Pardoll DM, Yu H. Persistently activated Stat3 maintains constitutive NF-kappaB activity in tumors. Cancer Cell 15: 283–293, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Y, Nie Y, Helou Y, Ding G, Feng B, Xu G, Salomon A, Xu H. Identification of sucrose non-fermenting-related kinase (SNRK) as a suppressor of adipocyte inflammation. Diabetes 62: 2396–2409, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li YP, Reid MB. NF-kappaB mediates the protein loss induced by TNF-alpha in differentiated skeletal muscle myotubes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 279: R1165–R1170, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Z, Zhang W, Zhang M, Zhu H, Moriasi C, Zou MH. Liver kinase B1 suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced nuclear factor kappaB (NF-kappaB) activation in macrophages. J Biol Chem 290: 2312–2320, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Londhe P, Guttridge DC. Inflammation induced loss of skeletal muscle. Bone 80: 131–142, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo G, Hershko DD, Robb BW, Wray CJ, Hasselgren PO. IL-1beta stimulates IL-6 production in cultured skeletal muscle cells through activation of MAP kinase signaling pathway and NF-kappa B. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 284: R1249–R1254, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGee SL, Hargreaves M. AMPK-mediated regulation of transcription in skeletal muscle. Clin Sci 118: 507–518, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Minari AL, Oyama LM, Dos Santos RV. Downhill exercise-induced changes in gene expression related with macrophage polarization and myogenic cells in the triceps long head of rats. Inflammation 38: 209–217, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mishra DK, Friden J, Schmitz MC, Lieber RL. Anti-inflammatory medication after muscle injury. A treatment resulting in short-term improvement but subsequent loss of muscle function. J Bone Joint Surg Am 77: 1510–1519, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mounier R, Theret M, Arnold L, Cuvellier S, Bultot L, Goransson O, Sanz N, Ferry A, Sakamoto K, Foretz M, Viollet B, Chazaud B. AMPKalpha1 regulates macrophage skewing at the time of resolution of inflammation during skeletal muscle regeneration. Cell Metab 18: 251–264, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Niemand C, Nimmesgern A, Haan S, Fischer P, Schaper F, Rossaint R, Heinrich PC, Muller-Newen G. Activation of STAT3 by IL-6 and IL-10 in primary human macrophages is differentially modulated by suppressor of cytokine signaling 3. J Immunol 170: 3263–3272, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Philippou A, Maridaki M, Theos A, Koutsilieris M. Cytokines in muscle damage. Adv Clin Chem 58: 49–87, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ray N, Kuwahara M, Takada Y, Maruyama K, Kawaguchi T, Tsubone H, Ishikawa H, Matsuo K. c-Fos suppresses systemic inflammatory response to endotoxin. Int Immunol 18: 671–677, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakamoto K, McCarthy A, Smith D, Green KA, Grahame Hardie D, Ashworth A, Alessi DR. Deficiency of LKB1 in skeletal muscle prevents AMPK activation and glucose uptake during contraction. EMBO J 24: 1810–1820, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sakurai H, Chiba H, Miyoshi H, Sugita T, Toriumi W. IkappaB kinases phosphorylate NF-kappaB p65 subunit on serine 536 in the transactivation domain. J Biol Chem 274: 30353–30356, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salvado L, Coll T, Gomez-Foix AM, Salmeron E, Barroso E, Palomer X, Vazquez-Carrera M. Oleate prevents saturated-fatty-acid-induced ER stress, inflammation and insulin resistance in skeletal muscle cells through an AMPK-dependent mechanism. Diabetologia 56: 1372–1382, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanosaka M, Fujimoto M, Ohkawara T, Nagatake T, Itoh Y, Kagawa M, Kumagai A, Fuchino H, Kunisawa J, Naka T, Takemori H. SIK3 deficiency exacerbates LPS-induced endotoxin shock accompanied by increased levels of proinflammatory molecules in mice. Immunology 145: 268–278, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scheller J, Chalaris A, Schmidt-Arras D, Rose-John S. The pro- and anti-inflammatory properties of the cytokine interleukin-6. Biochim Biophys Acta 1813: 878–888, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shan T, Zhang P, Liang X, Bi P, Yue F, Kuang S. Lkb1 is indispensable for skeletal muscle development, regeneration, and satellite cell homeostasis. Stem Cells 32: 2893–2907, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Szelenyi ER, Urso ML. Time-course analysis of injured skeletal muscle suggests a critical involvement of ERK1/2 signaling in the acute inflammatory response. Muscle Nerve 45: 552–561, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tanner CB, Madsen SR, Hallowell DM, Goring DM, Moore TM, Hardman SE, Heninger MR, Atwood DR, Thomson DM. Mitochondrial and performance adaptations to exercise training in mice lacking skeletal muscle LKB1. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 305: E1018–E1029, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomas MM, Wang DC, D'Souza DM, Krause MP, Layne AS, Criswell DS, O'Neill HM, Connor MK, Anderson JE, Kemp BE, Steinberg GR, Hawke TJ. Muscle-specific AMPK beta1beta2-null mice display a myopathy due to loss of capillary density in nonpostural muscles. FASEB J 28: 2098–2107, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomson DM, Brown JD, Fillmore N, Condon BM, Kim HJ, Barrow JR, Winder WW. LKB1 and the regulation of malonyl-CoA and fatty acid oxidation in muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293: E1572–E1579, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thomson DM, Hancock CR, Evanson BG, Kenney SG, Malan BB, Mongillo AD, Brown JD, Hepworth S, Fillmore N, Parcell AC, Kooyman DL, Winder WW. Skeletal muscle dysfunction in muscle-specific LKB1 knockout mice. J Appl Physiol 108: 1775–1785, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thomson DM, Porter BB, Tall JH, Kim HJ, Barrow JR, Winder WW. Skeletal muscle and heart LKB1 deficiency causes decreased voluntary running and reduced muscle mitochondrial marker enzyme expression in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292: E196–E202, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trenerry MK, Carey KA, Ward AC, Cameron-Smith D. STAT3 signaling is activated in human skeletal muscle following acute resistance exercise. J Appl Physiol 102: 1483–1489, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Windelinckx A, De Mars G, Huygens W, Peeters MW, Vincent B, Wijmenga C, Lambrechts D, Aerssens J, Vlietinck R, Beunen G, Thomis MA. Identification and prioritization of NUAK1 and PPP1CC as positional candidate loci for skeletal muscle strength phenotypes. Physiol Genomics 43: 981–992, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamashita K, Suzuki A, Satoh Y, Ide M, Amano Y, Masuda-Hirata M, Hayashi YK, Hamada K, Ogata K, Ohno S. The 8th and 9th tandem spectrin-like repeats of utrophin cooperatively form a functional unit to interact with polarity-regulating kinase PAR-1b. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 391: 812–817, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang J, Liao X, Agarwal MK, Barnes L, Auron PE, Stark GR. Unphosphorylated STAT3 accumulates in response to IL-6 and activates transcription by binding to NFkappaB. Genes Dev 21: 1396–1408, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang H, Taylor WR, Joseph G, Caracciolo V, Gonzales DM, Sidell N, Seli E, Blackshear PJ, Kallen CB. mRNA-binding protein ZFP36 is expressed in atherosclerotic lesions and reduces inflammation in aortic endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 33: 1212–1220, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]