Abstract

Ozone is a common, potent oxidant pollutant in industrialized nations. Ozone exposure causes airway hyperreactivity, lung hyperpermeability, inflammation, and cell damage in humans and laboratory animals, and exposure to ozone has been associated with exacerbation of asthma, altered lung function, and mortality. The mechanisms of ozone-induced lung injury and differential susceptibility are not fully understood. Ozone-induced lung inflammation is mediated, in part, by the innate immune system. We hypothesized that mannose-binding lectin (MBL), an innate immunity serum protein, contributes to the proinflammatory events caused by ozone-mediated activation of the innate immune system. Wild-type (Mbl+/+) and MBL-deficient (Mbl−/−) mice were exposed to ozone (0.3 ppm) for up to 72 h, and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid was examined for inflammatory markers. Mean numbers of eosinophils and neutrophils and levels of the neutrophil attractants C-X-C motif chemokines 2 [Cxcl2 (major intrinsic protein 2)] and 5 [Cxcl5 (limb expression, LIX)] in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid were significantly lower in Mbl−/− than Mbl+/+ mice exposed to ozone. Using genome-wide mRNA microarray analyses, we identified significant differences in transcript response profiles and networks at baseline [e.g., nuclear factor erythroid-related factor 2 (NRF2)-mediated oxidative stress response] and after exposure (e.g., humoral immune response) between Mbl+/+ and Mbl−/− mice. The microarray data were further analyzed to discover several informative differential response patterns and subsequent gene sets, including the antimicrobial response and the inflammatory response. We also used the lists of gene transcripts to search the LINCS L1000CDS2 data sets to identify agents that are predicted to perturb ozone-induced changes in gene transcripts and inflammation. These novel findings demonstrate that targeted deletion of Mbl caused differential levels of inflammation-related gene sets at baseline and after exposure to ozone and significantly reduced pulmonary inflammation, thus indicating an important innate immunomodulatory role of the gene in this model.

Keywords: neutrophils, genome-wide transcriptomics, pattern recognition analysis, tumor necrosis factor-α, innate immunity

exposure to ozone causes a variety of adverse respiratory health effects and continues to be an important global public health concern. Epidemiological studies have associated increases in the ambient levels of ozone with cardiovascular and respiratory mortality (45), as well as hospital admissions for respiratory diseases, particularly for children and the elderly (1). The potent oxidative potential of ozone also elicits an inflammatory response in the lungs of animals and humans experimentally exposed to ozone (22). The inflammatory response to ozone is characterized primarily by an influx of polymorphonuclear leukocytes into the airways, but other inflammatory cells, including eosinophils, T lymphocytes, and mast cells, are also involved. In addition to pulmonary inflammation, ozone exposure causes increased lung permeability and airway hyperreactivity (22). While the effects of ozone have been well characterized by numerous experimental studies, the mechanisms whereby these effects are elicited remain unclear.

A number of components of the innate and acquired immune systems have been implicated in the pulmonary response to ozone exposure (26, 32, 52). Roles for innate immunity-related genes, such as Tlr4 (Toll-like receptor 4), Marco (macrophage receptor with collagenous structure), and Notch3/Notch4 receptors, have been shown to be important in the development of ozone-induced inflammation (12, 26, 52). Mannose-binding lectin (MBL) is an innate immunity serum protein that, during certain disease states, binds carbohydrates on the surfaces of pathogens and altered host cells, upon which it can activate the complement system or act directly as an opsonin. MBL belongs to the family of collectins that includes surfactant proteins, and studies have demonstrated a role for collectins in ozone-induced oxidative stress, inflammation, and epithelial damage (24). MBL has also been linked to other oxidant-related diseases. Polymorphisms in MBL have been associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome, and inhibition of MBL reduces postischemic reperfusion injury (21, 29). Furthermore, studies have shown that MBL can bind apoptotic and necrotic cells and that MBL-initiated complement activation can contribute to host cell damage (25, 35). However, a role for MBL in pollutant-induced lung injury and inflammation has not been identified. In the present investigation we tested the hypothesis that MBL contributes to the innate immune inflammatory response to ozone exposure in mice and the effect is modulated through interactions among inflammatory response gene networks.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and exposure.

Male (6-wk-old) wild-type C57BL/6J (Mbl+/+) mice and C57BL/6J.129S4/SvJaeJ mice with targeted deletion of Mbl1 and Mbl2 [B6.129S4-Mbl1tm1KataMbl2tm1Kata (Mbl−/−) strain 006122] were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). After acclimation, mice were placed in individual stainless steel wire cages within a chamber (Hazelton 1000, Lab Products, Maywood, NJ) equipped with a charcoal- and high-efficiency particulate air-filtered air supply. Mice had free access to water and pelleted open-formula rodent diet (NIH-07, Zeigler Brothers, Gardners, PA). Mice were exposed continuously to 0.3 ppm ozone for 24, 48, or 72 h. Ozone was generated from ultra-high-purity air (1 ppm total hydrocarbons; National Welders, Raleigh, NC) using a silent-arc discharge ozone generator (model L-11, Pacific Ozone Technology, Benicia, CA). Constant chamber air temperature (72 ± 3°F) and relative humidity (50 ± 15%) were maintained. Ozone concentration was continually monitored (model 1008-PC, Dasibi Environmental, Glendale, CA). Parallel exposure to filtered air was carried out in a separate chamber for the same duration. Immediately after each exposure, mice were killed by pentobarbital sodium overdose (104 mg/kg). All animal use was approved by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Animal Care and Use Committee.

Bronchoalveolar lavage.

The left lung was lavaged in situ with Hanks' balanced salt solution. The pooled bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid returns were analyzed for cell differentials, and the first return was analyzed for protein content. Lung cellular inflammation and total protein (a marker of lung permeability) were assessed as described previously (8).

Real-time RT-PCR.

mRNA levels in right lung homogenates after 24, 48, and 72 h of exposure were quantified using real-time RT-PCR. Gene-specific primers were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). Expression values were normalized to β-actin and expressed as fold change over wild-type air control. Data are expressed as group means ± SE.

Agilent oligonucleotide microarray analyses.

Using RNeasy Mini kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), we isolated total RNA from whole lung homogenates from Mbl+/+ and Mbl−/− mice after 24, 48, and 72 h of exposure to air or ozone (n = 4/group). Microarray processing was done by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Microarray Core Facility. Gene transcript analysis was conducted using Whole Mouse Genome 4 × 44 multiplex format oligonucleotide arrays (014868, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) following the Agilent one-color microarray-based gene transcript analysis protocol. Starting with 500 ng of total RNA, we produced Cy3-labeled cRNA according to the manufacturer's protocol. For each sample, 1.65 μg of Cy3-labeled cRNAs were fragmented and hybridized for 17 h in a rotating hybridization oven. Slides were washed and then scanned with an Agilent scanner. Data were obtained using Agilent Feature Extraction software (version 9.5) with the one-color defaults for all parameters. The Agilent Feature Extraction Software performed error modeling, adjusting for additive and multiplicative noise. All microarray data have been submitted to Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, GSE68522). We used GeneSpring Expression Analysis software version 12.6 (Agilent Technologies) for initial characterization of gene transcript data. Ozone-induced changes in transcript values for each probe were normalized by dividing each sample by the average of its respective air controls. Transcripts were further analyzed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's honest significant difference post hoc tests (P < 0.05) comparing transcripts by genotype (Mbl+/+ and Mbl−/−) and exposure (24, 48, and 72 h of exposure to air and ozone). Lists of differential transcript levels from the microarray were used as inputs for the curated pathway database Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA; Qiagen; www.qiagen.com/ingenuity). IPA's Core Analysis module used the differential gene transcript sets to enrich for canonical and functional pathways or regulatory connections. Significance values were calculated using a right-tailed Fisher's exact test to determine if a pathway was overrepresented by calculating whether genes in a specific pathway were enriched within the data set compared with all genes on the array in the same pathway at a P < 0.05 cutoff for significance based on IPA threshold recommendations. Only pathways with a P value exceeding threshold and with more than two representative genes in the data set were considered. IPA was also used to identify potentially significant functional connections and mechanistic pathways.

EPIG analysis.

We also used EPIG (extracting gene expression patterns and identifying coexpressed genes) to characterize gene transcript patterns (10). EPIG utilizes the underlying structure of gene transcript data to extract patterns and identify coexpressed genes that are responsive to experimental conditions. Through evaluation of the correlations among profiles, the magnitude of variation in gene transcript profiles, and profile signal-to-noise (S/N) ratios, EPIG extracts a set of patterns representing coexpressed genes without a predefined seeding of the patterns. For each treatment group, the gene transcript measurement for each probe was converted to a ratio value by subtracting the average of the log base 2 pixel intensity of the time-matched air control samples from the log base 2 pixel intensity of the respective treatment group sample. EPIG uses Pearson correlations (r) across all the sample groups, S/N ratio within groups of samples, and magnitude of fold change for a probe within a group to first detect all potential patterns in the data and then categorize each probe to the pattern that is most statistically significant in terms of the correlation between the probe profile and the pattern. The parameter default settings for the EPIG analysis were as follows: r = 0.8, S/N ratio = 2.5, and fold change = 0.5. We used a minimum pattern cluster size of 6 for finding all potential patterns and a S/N ratio P < 0.0001 for significance. An advantage to using EPIG is that the analysis considers three factors in its query of differential transcript levels (exposure, genotype, and time), whereas GeneSpring Expression Analysis uses two factors (genotype and exposure) in separate analyses for each time point. Therefore, EPIG provides an analysis that complements the traditional ANOVA by considering the three factors simultaneously.

LINCS analysis.

The Library of Integrated Cellular Signatures (LINCS) project covers genomic responses to selected chemical compounds (see Ref. 13 for exposure and details; http://www.lincscloud.org/). It should be noted that many of the experiments in the LINCS database were performed with cancer cell lines. In the present study we performed LINCS1000 analyses on the gene signatures obtained from our microarray gene transcript experiments using the L1000CDS2 search engine (http://amp.pharm.mssm.edu/L1000CDS2/#/index). For each exposure condition and time point, we took the top 200 increased and 200 decreased gene transcripts based on the P values as input, chose “reverse” mode for small-molecule signatures that reversed our input, and allowed the small-molecule combination. For the top 50 search results ranked by the “search score” obtained from the L1000CDS2 analysis, we performed additional statistical tests for significance: we downloaded the original LINCS1000 transcript experiment results for each chemical compound perturbation and the respective cell line and all ∼22,000 L1000 genes, and we implemented the hypergeometric test that produced a P value for each enrichment result. All gene signatures were annotated with Entrez symbols, and duplicate gene entries were filtered prior to the test.

Statistics.

Values are group means ± SE. In all experiments, two- or three-way ANOVA was used to evaluate the effects of exposure and genotype on the outcome. The Student-Newman-Keuls test was used for a posteriori comparisons of means (P ≤ 0.05). All the statistical analyses were performed using the SigmaStat 3.0 software program (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Inflammatory cell recruitment following exposure to ozone.

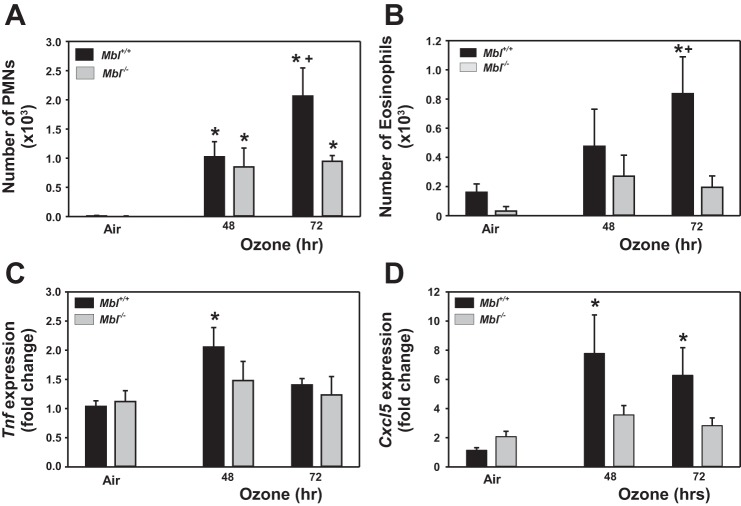

We found no significant differences in BAL cells or mediators between Mbl+/+ and Mbl−/− mice after air exposures (Fig. 1, Table 1). We next asked whether ozone-induced changes in BAL cells and protein differed between Mbl+/+ and Mbl−/− mice. Relative to respective air-exposed controls, mean BAL protein concentration and numbers of total cells and macrophages were significantly increased in Mbl+/+ and Mbl−/− mice after 48 and 72 h of ozone exposure, but no differences were found between strains (Table 1). Mean numbers of neutrophils and eosinophils in BAL fluid were also increased in Mbl+/+ and Mbl−/− mice after 48 and 72 h of ozone exposure; however, the numbers of these cell types were significantly reduced (>50% for neutrophils and >70% for eosinophils) in Mbl−/− mice compared with Mbl+/+ mice after 72 h of ozone exposure (Fig. 1, A and B; Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Effect of targeted deletion of mannose-binding lectin (Mbl) on mean numbers of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs, A) and eosinophils (B) recovered from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and mean expression of tumor necrosis factor-α (Tnf; C) and C-X-C motif chemokine 5 (Cxcl5; D) in lung homogenates after exposure to filtered air or 0.3 ppm ozone. Values are means ± SE of results from 3 separate, independent experiments with 6–12 mice/group. *P < 0.05 vs. strain-matched vehicle; +P < 0.05 vs. exposure-matched Mbl−/− mice (by 2-way ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls a posteriori pair-wise comparisons).

Table 1.

Numbers of cells and protein concentration recovered in BALF from Mbl+/+ and Mbl−/− mice after exposure to filtered air and 0.3 ppm ozone

| Phenotype |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mbl+/+ |

Mbl−/− |

|||||

| Air | 48 h ozone | 72 h ozone | Air | 48 h ozone | 72 h ozone | |

| Total cells, 103/ml BALF | 48.3 ± 10.7 | 95.4 ± 21.8* | 80.4 ± 6.2* | 54.6 ± 5.8 | 93.9 ± 24.6* | 80.2 ± 6.6* |

| Macrophages, 103/ml BALF | 38.9 ± 9.3 | 77.7 ± 18.7* | 65.2 ± 5.6* | 40.7 ± 4.9 | 75.8 ± 21.1* | 62.3 ± 5.3* |

| PMNs, 103/ml BALF | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.3* | 2.1 ± 0.5*† | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.9 ± 0.3* | 1.0 ± 0.1* |

| Eosinophils, 103/ml BALF | 0.4 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.3*† | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| Protein, μg/ml BALF | 95.6 ± 7.4 | 359.1 ± 45.9* | 314.1 ± 30.3* | 96.2 ± 10.9 | 340.8 ± 44.6* | 383.7 ± 39.4* |

Values are means ± SE of 6–12 per group.

BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; Mbl, mannose-binding lectin; PMNs, polymorphonuclear leukocytes.

P < 0.05 vs. genotype-matched air controls;

P < 0.05 vs. respective ozone-exposed Mbl−/− mice (by 3-way ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls a posteriori pairwise comparisons).

The inflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and the neutrophil chemoattractants C-X-C motif chemokines 2 and 5 (CXCL2 and CXCL5) are known to be elicited by ozone exposure (17, 30, 49, 54). Using RT-PCR, we found that ozone significantly increased the amount of Il6 in the lung homogenate in Mbl+/+ and Mbl−/− mice after 48 and 72 h, but no genotype effects were found (data not shown). Ozone also increased the amount of Tnf (48 h; Fig. 1C), Cxcl2 (48 and 72 h; data not shown), and Cxcl5 (48 and 72 h; Fig. 1D) the lung homogenate in Mbl+/+, but not Mbl−/−, mice.

Ozone does not affect levels of MBL or complement components.

Given the phenotypic differences between Mbl+/+ and Mbl−/− mice after ozone exposure, we asked whether ozone had a direct effect on MBL levels. MBL concentrations in the serum and in lung homogenates from Mbl+/+ mice were unchanged after air and ozone exposure, and a slight, although not statistically significant, reduction was found in the liver (data not shown). A slight, although not statistically significant, reduction in Mbl mRNA expression was found in the liver of Mbl+/+ mice following ozone exposure (data not shown). We also compared the levels of complement components 2 and 3 in the liver, lung, and serum of Mbl+/+ and Mbl−/− mice, but we found no significant genotype effects (data not shown).

Genome-wide analysis of differential transcript levels in Mbl+/+ and Mbl−/− mice.

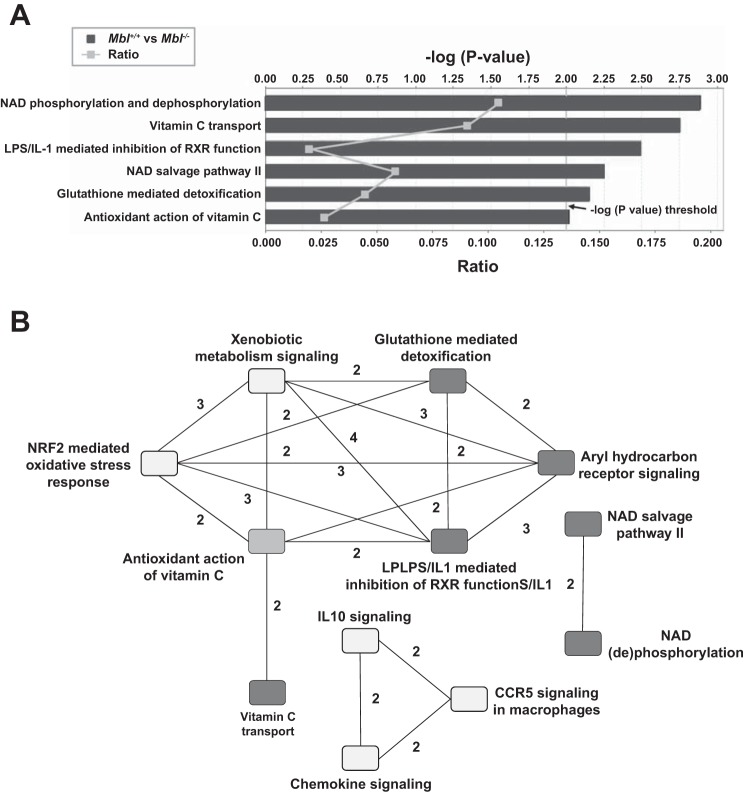

To further understand the role of Mbl in ozone-induced inflammation, we generated microarray gene transcript response profiles for Mbl+/+ and Mbl−/− mice exposed to filtered air or ozone for 24, 48, and 72 h (GeneSpring Expression Analysis). Principal components analyses revealed minimal variation in transcript arrays between Mbl+/+ and Mbl−/− mice exposed to air for 24, 48, and 72 h, and we found no statistically significant differences in transcripts between time points within each strain (data not shown). However, transcripts from ozone-exposed mice separated between time points within and between genotypes. Relative to Mbl+/+ mice exposed only to filtered air, 23 transcripts increased and 72 transcripts decreased in the lungs of air-exposed Mbl−/− mice, including Adamdec1 (ADAM-like, decysin 1) and Anxa8 (annexin A8), which have roles in inflammation and response to injury (11, 42) (see Supplemental Table S1 in Supplemental Material for this article available online at the Journal website). RT-PCR confirmed the differential expression of Adamdec1 and Anxa8 (data not shown). When we analyzed the transcripts in IPA, we found significant enrichment of canonical inflammatory and antioxidant pathways (e.g., NAD phosphorylation and dephosphorylation and glutathione-mediated detoxification) (Fig. 2A). IPA also identified a number of pathways between which there are significant interactions [e.g., nuclear factor erythroid-related factor 2 (NRF2)-mediated oxidative response and xenobiotic metabolism signaling] (Fig. 2B). The differential transcript and pathway analyses suggest that Mbl may contribute to the pulmonary response to ozone through basal modulation of gene networks involved in oxidative stress responses. It is important to note that these are associations and not proof that all the patterns contribute to differential responses to ozone, and further investigations are necessary to establish causal relationships.

Fig. 2.

Differential gene transcript levels in Mbl+/+ and Mbl−/− mice after exposure to filtered air. A: enrichment of transcripts in Mbl+/+ and Mbl−/− mice into canonical pathways using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA). Vertical line (at −log2) is the statistical threshold (P < 0.01) for enrichment. White squares show the ratio of input target genes compared with the total number of genes in the pathway. B: node-and-edge interconnection plot of canonical pathways of differential transcript levels in Mbl+/+ and Mbl−/− mice. Minimum edge weight is 2 common genes (numbers next to edges). Dark, medium, and light-gray nodes represent P < 0.01, P < 0.025, and P < 0.05 enrichment, respectively.

We then analyzed all array data from both genotypes to identify lists of significantly increased or reduced gene transcripts after ozone exposure compared with respective air controls. We found that 2,184 (24 h), 1,022 (48 h), and 1,138 (72 h) lung gene transcripts increased with ozone exposure in Mbl+/+ mice and 1,982 (24 h), 720 (48 h), and 967 (72 h) decreased with ozone exposure. We found fewer ozone-induced transcript levels in Mbl−/− than Mbl+/+ mice at all time points [1,551 (24 h), 562 (48 h), and 809 (72 h) increased transcripts and 1,485 (24 h), 494 (48 h), and 476 (72 h) decreased transcripts]. Among the altered numbers of transcripts after ozone exposure, 42.9% (24 h), 52% (48 h), and 48.9% (72 h) were unique to Mbl+/+ mice, 35.4% (24 h), 27.1% (48 h), and 34.8% (72 h) were unique to Mbl−/− mice, and 21.7% (24 h), 27.1% (48 h), and 34.8% (72 h) were common to both genotypes (see Supplemental Table S2).

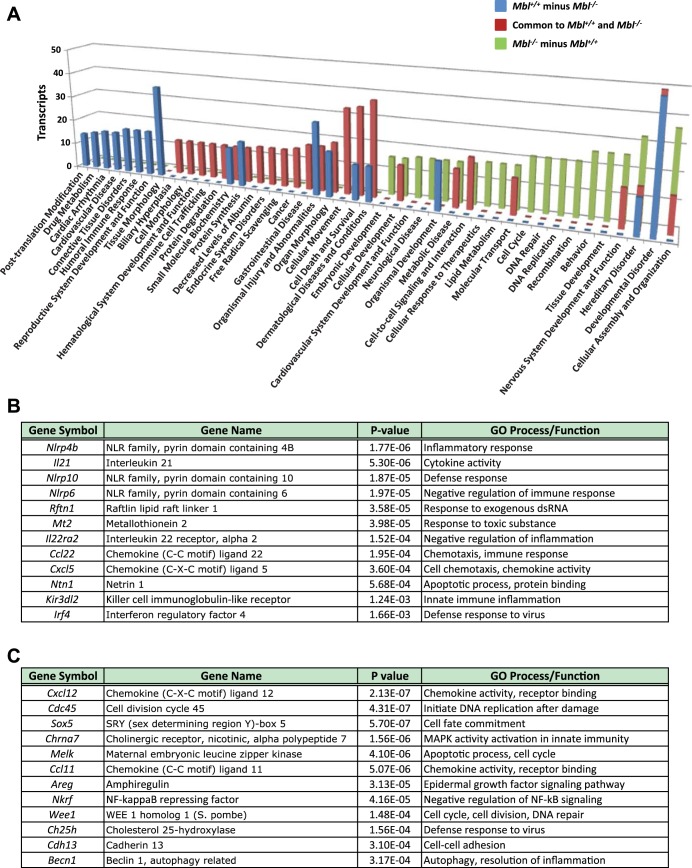

Gene ontology for differential transcript levels after ozone.

We used gene ontology (GO) annotations of the 200 most significantly changed transcripts to characterize the transcriptomic response in terms of biological processes and molecular pathways. Among genotype-specific transcript levels after air exposure, highly enriched GO categories included cancer, molecular transport, tissue development, cell morphology, and respiratory system development and function (see Supplemental Table S3). Categories of gene transcripts that were increased only in Mbl+/+ mice after 24 h of ozone exposure were posttranslational modification, connective tissue disorders, and humoral immune response (Fig. 3A; see Supplemental Table S3). These categories included chemokine activity genes (e.g., Cxcl5) (Fig. 3B). Changed transcripts found only in Mbl−/− mice included innate immune inflammation genes (e.g., Cxcl12 and Chrna7) (Fig. 3C). Differential transcript levels of these genes, as well as Cxcl2 and Tnf, were confirmed using RT-PCR (Fig. 1 and data not shown). After 48 and 72 h of exposure, the GO categories included infectious disease, free radical scavenging, hematological and inflammatory diseases, and immune cell trafficking (see Supplemental Table S3). GO categories of diminished gene transcripts only in Mbl+/+ mice after ozone included cellular compromise, cellular assembly and organization, immunological disease, cancer, and respiratory system development and function (see Supplemental Table S3). Together, these analyses indicate that, while many transcripts are common to both genotypes, genotype-specific transcripts are also differentially expressed and provide insight into potential mechanisms through which Mbl contributes to differential gene transcript levels and inflammatory responses to ozone exposure.

Fig. 3.

A: gene ontology (GO) categories for numbers of increased gene transcript levels after 24 h of ozone exposure and specific to Mbl+/+ mice, specific to Mbl−/− mice, or common to both genotypes. y-Axis, number of gene transcripts in each category. (Gene annotations for each category are listed in Supplemental Table S3.) B: selected gene transcripts that were increased only in Mbl+/+ mice after 24 h of ozone exposure. C: selected gene transcripts that were increased only in Mbl−/− mice after 24 h of ozone exposure.

EPIG analysis.

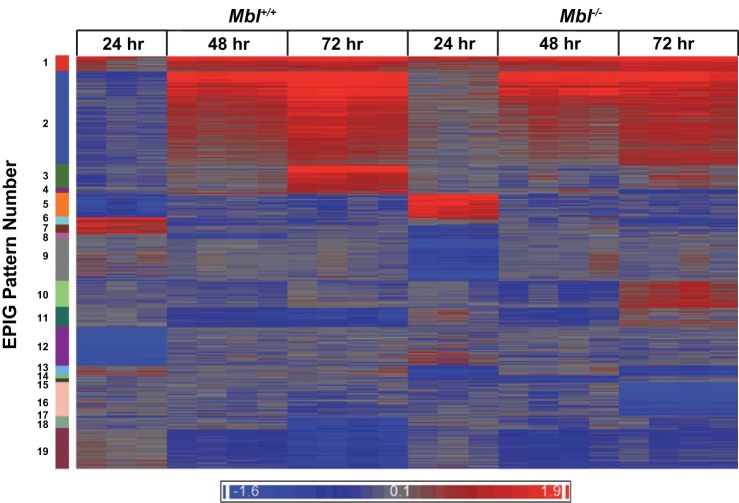

To further explore the role of Mbl in gene expression, we performed an unsupervised analysis of the microarray data using EPIG, a program designed to extract transcript patterns. EPIG analysis allowed us to identify genes that are similarly or differentially changed among treatment groups. Initially, we used EPIG to identify 19 patterns with 2,085 coexpressed gene transcripts in lungs of Mbl+/+ mice that differed between air and ozone exposures (see Supplemental Table S4). We prioritized closer examination of the patterns that had increased transcripts early during exposure and remained elevated [patterns 1 (328 transcripts) and 2 (53 transcripts)] and a pattern that contained lower transcript levels during the exposure [pattern 18 (455 transcripts)]. Transcripts in patterns 1 and 2 included some, such as Socs3 (suppressor of cytokine signaling 3) (52) and Cd44 (CD44) (19), that had previously been associated with ozone-induced inflammation. Others have been implicated in pathogenesis of lung cancer cell migration [Il24 (IL-24)] (39) and tuberculosis [Irf8 (interferon regulatory factor 8)] (33). Transcript network functions for patterns 1 and 2 included cell cycle (cellular assembly and organization, infectious disease, and cancer) and lipid metabolism (IPA enrichment scores = 62-35). Pattern 18 transcripts included Cd1d (CD1d) (41) and Cd226 (CD226) (5), which have been associated with lung disease, and Cd1d has been suggested to have a role in the innate immune response to ozone. Cell-mediated immune response, cell signaling, and cellular development network functions were enriched with pattern 18 transcripts (IPA enrichment scores = 45-32).

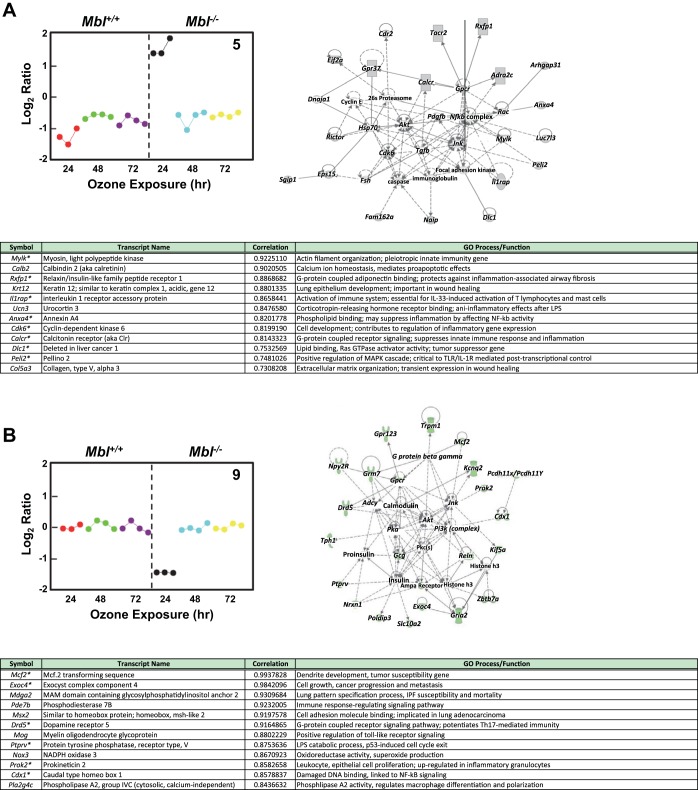

We also used EPIG analysis to identify ozone-induced transcript patterns that varied between the two genotypes after 24–72 h of exposure (Fig. 4; see Supplemental Table S5). We focused further attention on two patterns that were distinctly different between Mbl+/+ and Mbl−/− mice: pattern 5 (increased transcript levels in Mbl−/− mice after 24 h) and pattern 9 (decreased transcript levels in Mbl−/− mice after 24 h) (Fig. 5; see Supplemental Table S5). Pattern 5 includes a number of genes associated with innate immunity [e.g., Mylk (myosin, light polypeptide kinase)] (18), epithelium development and wound healing [e.g., Krt12 (keratin 12)] (7), and suppression of innate immune response and inflammation [e.g., Calcr (calcitonin receptor)] (34) (Fig. 5A). Pattern 9 includes genes that regulate immune response signaling [e.g., Pde7b (phosphodiesterase 7b)] (28), Toll-like receptor signaling [e.g., Mog (myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein)] (20), and Th17-mediated immunity [e.g., Drd5 (dopamine receptor 5)] (43) (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 4.

Heat map of 4,237 gene transcripts that were selected by EPIG (extracting gene expression patterns and identifying coexpressed genes) for pattern analyses in Mbl+/+ and Mbl−/− mice after 24–72 h of ozone exposure. Transcripts are arranged from top to bottom according to the 19 patterns that were identified. For the 24-h exposure, there are 3 separate mice for each genotype; for the 48- and 72-h exposures, there are 4 separate mice for each genotype. Bottom bar: blue and red colors indicate decreased and increased transcripts, respectively, and darker colors indicate greater transcript changes. (See Supplemental Table S5 for correlations and P values for each transcript and pattern.)

Fig. 5.

Representative gene transcript patterns identified by EPIG analysis that are different in Mbl+/+ and Mbl−/− mice. A: pattern 5 indicates transcripts that increased only in Mbl−/− mice after 24 h of ozone exposure (107 transcripts; 11 with biological relevance to the model are shown in table); each filled circle is the mean relative transcript level for 1 mouse. One of 2 IPA gene interaction networks (embryonic development and organ development; IPA enrichment score = 41) from the pattern 5 transcripts is shown and includes 22 that were differentially expressed (gray filled symbols). *Genes that are also in the IPA network. B: pattern 9 indicates transcripts that decreased only in Mbl−/− mice after 24 h of ozone exposure (127 transcripts). One of 3 IPA gene interaction networks (cell-to-cell signaling; IPA enrichment score = 45) from the pattern 9 transcripts is shown and includes 23 that were differentially expressed (green filled symbols).

IPA identified a network from pattern 5 that includes 22 genes (IPA enrichment score = 41) that interact with NF-κB and JNK signaling (Fig. 5A) and have been demonstrated to have an important role in ozone-induced inflammation (8). Twenty-three pattern 9 transcripts (IPA enrichment score = 45) were found to interact in a network with calmodulin, phosphoinositide 3-kinase, and AKT signaling, which may have important implications for regulation of inflammation (23, 56) and may contribute to the differential response to ozone between Mbl+/+ and Mbl−/− mice.

LINCS1000 analyses.

We next used LINCS1000 to identify, via signature overlap assessment, transcript profiles from cell-based drug perturbation experiments that overlap with transcript profiles generated for ozone exposure responses (see Supplemental Table S6). Significantly high overlaps were found between our differential transcript lists at all three time points. The minimum overlap ratios (the input differential transcripts and the signature differential transcripts divided by the effective input) at 24 h ranged from 0.0349 to 0.0581 (see Supplemental Table S6). At 24 h, the top hit was an experiment with vorinostat at 10.0 μM for 24-h exposure to HCC515 cells with 11 gene transcript levels overlapped and P = 0.005, and the lowest hit was an experiment with trichostatin A at 10.0 μM for 6.0-h exposure to JHUEM2 cells with four differential transcript levels that overlapped and P = 0.02. At 48 and 72 h, overlapping differential transcript levels increased significantly with nominal P values for hypergeometric tests as high as <10−99 (see Supplemental Table S6). Many of the drugs with the highest overlaps have been classified as antineoplastic or antiproliferative (Table 2). For the Mbl-specific transcripts, we subtracted those that appeared in the wild-type strains and retained much smaller numbers of transcripts at each time point (see Supplemental Table S6). The LINCS1000 analysis identified minimum overlap ratios, but most hits were found to be not statistically significant (nominal P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Representative list of drugs identified using the LINCS L1000CDS2 search engine for which there are statistically significant overlap ratios of transcript profiles from cell-based perturbation experiments and ozone exposures

| Drug Name | Activity of Compound | Disease Treatment | Minimum Overlap Ratio | Corresponding P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quinacrine hydrochloride | Inhibitor of HNMT | Antiprotozoal/antirheumatic agent | 0.3616 | 1.73 × 10−99 |

| BMS-536924 | Inhibitor of IFG1R and INSR | Antineoplastic activity | 0.3438 | 8.75 × 10−82 |

| Palbociclib | Target cyclin-dependent kinases CDK4 and CDK6 | Treatment of metastatic breast cancer | 0.3438 | 2.13 × 10−95 |

| Torin-2 | Inhibitor of mTOR | Inhibition of tumor cell proliferation | 0.3393 | 1.39 × 10−85 |

| Mitoxantrone | Binds topoisomerase II | Antibiotic with antineoplastic activity | 0.3304 | 4.10 × 10−86 |

| Dovitinib | Binds to FGFR3 | Inhibition of tumor cell proliferation | 0.3259 | 1.03 × 10−92 |

| Nutlin-3 | Inhibitor of p53-MDM2 interaction | Activation of cell cycle arrest/apoptosis | 0.3214 | 2.16 × 10−76 |

| Etoposide | Inhibitor of TOP2A | Chemotherapy for cancers | 0.3214 | 4.16 × 10−87 |

| Cucurbitacin I | Inhibitor of STAT3 and JAK2 | Antiproliferative agent | 0.3170 | 9.91 × 10−75 |

| Trametinib | Inhibitor of MAP2K1 and MAP2K2 | Treatment for metastatic melanoma | 0.3170 | 9.53 × 10−80 |

Details for Library of Integrated Cellular Signatures (LINCS) L1000CDS2 analyses are described in materials and methods, and other drugs and overlap ratios are included in Supplemental Table S6. CDK, cyclin-dependent kinase; FGFR3, fibroblast growth factor receptor 3; HNMT, histamine N-methyltransferase; IGF1R, insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor; INSR, insulin receptor; JAK2, Janus kinase 2; MAP2K, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; MDM2, mouse double minute 2; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; TOP2A, topoisomerase II.

DISCUSSION

Exposure to ground-level ozone remains an important environmental health concern, particularly for sensitive individuals. The potent oxidative properties of the gas elicit a number of detrimental effects in the lungs that have been well characterized by numerous studies (22). Although the physiological effects of ozone exposure have been well characterized, the mechanisms that elicit these effects are not completely understood. In the present study we found that targeted deletion of Mbl blunted the ozone-induced neutrophil (>50%) and eosinophil (>70%) infiltration into the lung and supported a proinflammatory role for the innate immune protein MBL. These novel findings add to a growing body of evidence that suggests that the innate immune response is a critical component to the detrimental effects of ozone exposure.

One of the greatest effects of deletion of Mbl on inflammatory phenotypes was the ∼50% reduction of neutrophilic inflammation. In support of this Mbl-dependent effect on neutrophils, we also found reduced levels of the neutrophil chemoattractants Cxcl2 and Cxcl5 in Mbl−/− mice compared with Mbl+/+ mice. These results are consistent with other findings that have shown a role for MBL in oxidant-induced injury (21, 29). Previously, using Tnf and Tnfr1/Tnfr2 knockout mice, we showed that TNF-α mediates a large portion of the inflammatory response in this ozone exposure model (8, 9). In the current investigation, using mice with wild-type Tnf, we have demonstrated that Mbl contributes to the later phase (i.e., 72 h) of the inflammatory cell response and appears to contribute subsequent to the effects of TNF-α, which peaks earlier (6–24 h) in the exposure (8). Together, these findings add to our understanding of the role of innate immune genes in the development of ozone-induced inflammation in the lung.

However, the mechanism by which MBL elicits the observed effects remains unclear. Because exposure to ozone and other environmental oxidants has been shown to alter the expression or activation of various innate immune proteins and their pathways (16, 26, 52), we hypothesized that a plausible mechanism behind the differential responses was that ozone exposure enhanced levels of MBL, leading to increased activity and/or signaling. However, we did not find a direct effect of ozone exposure on MBL levels in the blood, lung, or liver (data not shown). Moreover, we did not find an increase in components of the complement cascade, which may have been activated by MBL (i.e., the lectin pathway of the complement system). It is possible that the levels of complement components were limited to specific cell types and did not change significantly enough during activation to detect differences in whole lung homogenates or that the changes occurred at times other than 48 and 72 h of exposure, when the complement was measured. Alternatively, MBL may be eliciting these effects without activating the complement cascade. MBL has been shown to act as an opsonin for damaged cells (37, 48). This function of MBL could thus be the cause of the neutrophil influx in response to ozone-induced lung damage.

The role of MBL in lung injury may vary depending on the cause of the disease. For example, Chang et al. (6) found that MBL protects against acute lung injury (ALI) induced by influenza A virus (IAV) infection. Administration of recombinant human MBL reversed the IAV infection phenotype, and mice with targeted deletion of MBL were more susceptible to IAV disease. The enhanced disease induced by IAV was attributed to the antiviral function of MBL, which includes viral aggregation, inhibition of viral hemagglutination, and virus opsonization (6). On the contrary, Sun et al. (47) found deposition of MBL-C and complement C3 and C5b-9 in the lung in a mouse model of H5N1 virus infection. Inhibition of the complement components significantly reduced ALI phenotypes, suggesting a proinflammatory contribution of these proteins. It is clear that additional research is necessary to understand the mechanisms through which MBL and related pathways mediate the pulmonary response to environmental agents that lead to ALI.

To further explore potential mechanisms to explain the differential ozone-induced inflammation between Mbl+/+ and Mbl−/− mice, we used mRNA arrays and generated gene transcript response profiles for both strains of mice and compared profiles after filtered air and ozone exposure. The inherent value of GO and in silico mapping of transcripts that differ between genotypes and exposures is that the investigation is not constrained by previous assumptions but, rather, seeks to discover novel genes and pathways that associate with disease phenotypes and may provide potential mechanisms to explain differences between genotypes or other factors in the design. ANOVA identified 96 gene transcripts that differed between Mbl+/+ and Mbl−/− mice after exposure to filtered air (ozone controls), and IPA generated gene lists and pathways with potentially important functional relevance to differential susceptibility to ozone in the two genotypes. Decreased gene transcripts in Mbl−/− mice include Adamdec1 (11) and Anxa8 (42), which have been associated with inflammation and responses to injury (see Supplemental Table S1). Others have been indicated in Nrf2-mediated oxidative stress responses and glutathione-mediated detoxification pathways (Fig. 3). It is feasible that absence of Mbl enhanced basal defenses against oxidant stress and inflammation, which contributed to less inflammation than in Mbl+/+ mice, although further investigation is necessary to confirm these hypotheses.

ANOVA also identified Mbl-dependent transcripts that were differentially expressed at all time points of ozone exposure. Interestingly, the most extensive lists were generated from the 24-h time-point analyses, suggesting that, although the majority of our phenotypic observations were at 48 and 72 h of ozone exposure, many of the differential transcript responses begin to occur much earlier. It is possible that some of the phenotypic responses would be observed if mice were examined 24–48 h after a 24-h ozone exposure, instead of immediately following the exposure. Alternatively, the changes in gene transcripts observed at 24 h might not have led to significant phenotypic events without the additional stress caused by continued exposure to ozone. It is also of interest that some of the Mbl-dependent GO categories (Fig. 3) included genes involved in tissue repair and resolution of inflammation, similar to those found differentially expressed basally. For example, expression of Cxcl2 (38) and Cxcl5 (4) increased only in Mbl+/+ mice and have been implicated in ozone-induced inflammation; others, including Nlrp10 (14) and Ill22ra2 (27), have been associated previously with tissue injury and repair processes, but not with ozone. In Mbl−/− mice, Cxcl12 (55) and Chrna7 (53) were differentially expressed and have important roles in resolution of inflammation in other models of injury and, thus, provide insight into the contribution of Mbl to differential pulmonary responses to ozone.

The unsupervised analyses using EPIG identified patterns within the microarray data sets over the three exposure time points that associate with the observed phenotypic response are both similar and different between strains and may not have been identified using ANOVA. Similar to the ANOVA, EPIG analysis found the largest number of differential transcript levels between the two strains after 24 h of ozone exposure. Transcripts found in patterns 5 and 9 were differentially expressed at this time and associated with pathways related to organ development and cell-to-cell signaling. These transcripts, as well as those found by ANOVA, provide potential novel targets for further investigation. Gene lists and IPA patterns for later time points (e.g., patterns 3, 10, and 16) may provide insight into the reparative pathways initiated in response to ozone exposure and the role of Mbl in these processes.

Genome-wide mRNA arrays were used to determine potential mechanisms of MBL-mediated protection in a mouse model of hyperglycemic vasculopathy and cardiomyopathy (57). Not surprisingly, few of the primary GO categories and gene sets associated with this model were similar to those identified in the lung following ozone exposure, likely due to differences in affected organs and the more chronic kinetics of the disease. However, the role of insulin signaling, including phosphoinositide 3-kinase, AKT, and MAPK, in the hyperglycemia model and also after 24 h of exposure to ozone (EPIG analysis) (Fig. 5) suggests a potential common mechanism through which MBL may be modulating disease progression. A recent study that linked ozone exposure and insulin resistance via JNK activation in rats (51) further supports this notion.

We also used our differential transcript sets to query the LINCS L1000CDS2 data sets for chemicals and drugs that have reverse (antagonistic) molecular signatures that indicate reversal of the ozone-induced transcript levels. The LINCS L1000CDS2 search engine has been used to investigate kinase inhibitor signaling and receptor signaling networks to understand drug therapeutics and side effects (36, 44). Among the perturbation chemicals and drugs with the highest overlap score with ozone-induced gene transcript levels were quinacrine, dovitinib, and mitoxantrone. Quinacrine, also commonly known as mepacrine, is a compound with multiple actions that has been commonly used as an antiprotozoal (50) and antirheumatic (46) agent and, more recently, as a therapy for systemic lupus erythematosus (3). Interestingly, many of the chemical and drug perturbations have antineoplastic activities. For example, dovitinib is a drug with potential antineoplastic activity through binding to fibroblast growth factor receptor, inhibiting its phosphorylation and, subsequently, inhibiting tumor cell proliferation (31). Mitoxantrone, another antineoplastic agent that has also been used to treat multiple sclerosis (2, 15), is a type II topoisomerase inhibitor that can disrupt DNA synthesis and DNA repair (40). This novel bioinformatic approach has therefore identified highly plausible intervention compounds with known molecular targets that may attenuate the inflammatory response to ozone exposure.

This investigation has a number of strengths. First, our finding of significantly reduced pulmonary inflammatory cell infiltration in mice with targeted deletion of Mbl compared with wild-type mice provides strong in vivo support for the hypothesis that this gene contributes to the innate immune response to ozone inhalation. Another strength of the study is the use of genome-wide transcriptomics with ANOVA models and unsupervised analysis tools to identify gene transcripts and transcript patterns to identify potential mechanisms through which Mbl modulates inflammation. This approach identified Mbl-dependent gene transcript levels, at baseline (filtered air) and after ozone exposure, that were associated with differential inflammatory responses by the two genotypes. Some of these transcripts had previously been associated with pulmonary responses to ozone, but others are novel and, therefore, are future targets for investigation that will provide additional insight into the innate immune inflammatory response. Another important application for the transcript sets led to identification of potential intervention compounds that may attenuate ozone-induced inflammation. A limitation of this study is that, while the differences in gene transcripts between exposures and genotypes suggest mechanisms for Mbl effects, they require in vitro or in vivo validation of the involvement in ozone-induced inflammation.

It is important to emphasize that deletion of Mbl did not ablate the inflammatory response to ozone but did account for ∼50% of the neutrophil infiltration after 72 h of exposure. Therefore, other genetic mechanisms also must contribute to the ozone-induced inflammatory response. It has been shown by others and us (8, 30, 49) that chemokines and cytokines are important proinflammatory mediators of the complex immune response to ozone exposure and that additional factors, such as scavenger receptors and notch receptors, also contribute in a time-dependent manner. Continued investigation of pro- and anti-inflammatory components of the inflammatory response, independently and as cofactors, should provide further understanding of the mechanisms of response to ozone exposure.

The phenotypic responses and differential gene transcript analyses in the present study thus provide additional insight into the involvement of the innate immune system, and specifically MBL, in the ozone-induced inflammatory response in the lung. Further examination and validation of MBL-dependent changes in gene transcripts will be useful to explore potential mechanisms behind pulmonary inflammation and damage in response to ozone exposure. Characterization of the mechanisms and identification of genes involved in ozone-induced lung damage are important steps toward identification of susceptible individuals and disease intervention.

GRANTS

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and Department of Health and Human Services.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.M.C. and S.R.K. developed the concept and designed the research; J.M.C. performed the experiments; J.M.C., K.C.V., K.E.G., Z.R.M., J.L., P.R.B., and S.R.K. analyzed the data; J.M.C., K.C.V., K.E.G., Z.R.M., J.L., P.R.B., and S.R.K. interpreted the results of the experiments; J.M.C., J.L., and S.R.K. prepared the figures; J.M.C. and S.R.K. drafted the manuscript; J.M.C., K.C.V., K.E.G., Z.R.M., J.L., P.R.B., and S.R.K. edited and revised the manuscript; J.M.C., K.C.V., K.E.G., Z.R.M., P.R.B., and S.R.K. approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Microarray Core (Rick Fannin and Laura Wharey) and Alion Science and Technology for performing ozone exposures. We also thank Drs. Stavros Garantziotis and Michael Fessler for very helpful critical review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernstein JA, Alexis N, Barnes C, Bernstein IL, Nel A, Peden D, Diaz-Sanchez D, Tarlo SM, Williams PB. Health effects of air pollution. J Allergy Clin Immunol 114: 1116–1123, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bezu L, Gomes-de-Silva LC, Dewitte H, Breckpot K, Fucikova J, Spisek R, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Kroemer G. Combinatorial strategies for the induction of immunogenic cell death. Front Immunol 6: 187, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buyon JP, Cohen P, Merrill JT, Gilkeson G, Kaplan M, James J, McCune WJ, Bernatsky S, Elkon K. A highlight from the LUPUS 2014 meeting: eight great ideas. Lupus Sci Med 2: e000087, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cabello N, Mishra V, Sinha U, DiAngelo SL, Chroneos ZC, Ekpa NA, Cooper TK, Caruso CR, Silveyra P. Sex differences in the expression of lung inflammatory mediators in response to ozone. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 309: L1150–L1163, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan CJ, Martinet L, Gilfillan S, Souza-Fonseca-Guimaraes F, Chow MT, Town L, Ritchie DS, Colonna M, Andrews DM, Smyth MJ. The receptors CD96 and CD226 oppose each other in the regulation of natural killer cell functions. Nat Immunol 15: 431–438, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang WC, White MR, Moyo P, McClear S, Thiel S, Hartshorn KL, Takahashi K. Lack of the pattern recognition molecule mannose-binding lectin increases susceptibility to influenza A virus infection. BMC Immunol 11: 64, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L, Meng Q, Kao W, Xia Y. IκB kinase-β regulates epithelium migration during corneal wound healing. PLos One 6: e16132, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho HY, Morgan DL, Bauer AK, Kleeberger SR. Signal transduction pathways of tumor necrosis factor-mediated lung injury induced by ozone in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175: 829–839, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho HY, Zhang LY, Kleeberger SR. Ozone-induced lung inflammation and hyperreactivity are mediated via tumor necrosis factor-α receptors. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 280: L537–L546, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou JW, Zhou T, Kaufmann WK, Paules RS, Bushel PR. Extracting gene expression patterns and identifying co-expressed genes from microarray data reveals biologically responsive processes. BMC Bioinformatics 8: 427, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crouser ED, Culver DA, Knox KS, Julian MW, Shao G, Abraham S, Liyanarachchi S, Macre JE, Wewers MD, Gavrilin MA, Ross P, Abbas A, Eng C. Gene expression profiling identifies MMP-12 and ADAMDEC1 as potential pathogenic mediators of pulmonary sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 179: 929–938, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahl M, Bauer AK, Arredouani M, Soininen R, Tryggvason K, Kleeberger SR, Kobzik L. Protection against inhaled oxidants through scavenging of oxidized lipids by macrophage receptors MARCO and SR-AI/II. J Clin Invest 117: 757–764, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duan Q, Flynn C, Niepel M, Hafner M, Muhlich JL, Fernandez NF, Rouillard AD, Tan CM, Chen EY, Golub TR, Sorger PK, Subramanian A, Ma'ayan A. LINCS Canvas Browser: interactive web app to query, browse and interrogate LINCS L1000 gene expression signatures. Nucleic Acids Res 42: W449–W460, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisenbarth SC, Williams A, Colegio OR, Meng H, Strowig T, Rongvaux A, Henao-Mejia J, Thaiss CA, Joly S, Gonzalez DG, Xu L, Zenewicz LA, Haberman AM, Elinav E, Kleinstein SH, Sutterwala FS, Flavell RA. NLRP10 is a NOD-like receptor essential to initiate adaptive immunity by dendritic cells. Nature 484: 510–513, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellis R, Brown S, Boggild M. Therapy-related acute leukaemia with mitoxantrone: four years on, what is the risk and can it be limited? Multiple Sclerosis 21: 642–645, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fry RC, Rager JE, Zhou H, Zou B, Brickey JW, Ting J, Lay JC, Peden DB, Alexis NE. Individuals with increased inflammatory response to ozone demonstrate muted signaling of immune cell trafficking pathways. Respir Res 13: 89, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gabehart K, Correll KA, Yang J, Collins ML, Loader JE, Leach S, White CW, Dakhama A. Transcriptome profiling of the newborn mouse lung response to acute ozone exposure. Toxicol Sci 138: 175–190, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao L, Tsai YJ, Grigoryev DN, Barnes KC. Host defense genes in asthma and sepsis and the role of the environment. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 7: 459–467, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garantziotis S, Li Z, Potts EN, Kimata K, Zhuo L, Morgan DL, Savani RC, Noble PW, Foster WM, Schwartz DA, Hollingsworth JW. Hyaluronan mediates ozone-induced airway hyperresponsiveness in mice. J Biol Chem 284: 11309–11317, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 20.Garcia-Vallejo JJ, Ilarregui JM, Kalay H, Chamorro S, Koning N, Unger WW, Ambrosini M, Montserrat V, Fernandes RJ, Bruijns SC, van Weering JR, Paauw NJ, O'Toole T, van Horssen J, van der Valk P, Nazmi K, Bolscher JG, Bajramovic J, Dijkstra CD, 't Hart BA, van Kooyk Y. CNS myelin induces regulatory functions of DC-SIGN-expressing, antigen-presenting cells via cognate interaction with MOG. J Exp Med 211: 1465–1483, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gong MN, Zhou W, Williams PL, Thompson BT, Pothier L, Christiani DC. Polymorphisms in the mannose binding lectin-2 gene and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 35: 48–56, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guarnieri M, Balmes JR. Outdoor air pollution and asthma. Lancet 383: 1581–1592, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo L, Stripay JL, Zhang X, Collage RD, Hulver M, Carchman EH, Howell GM, Zuckerbraun BS, Lee JS, Rosengart MR. CaMKIα regulates AMP kinase-dependent, TORC-1-independent autophagy during lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung neutrophilic inflammation. J Immunol 190: 3620–3628, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haque R, Umstead TM, Freeman WM, Floros J, Phelps DS. The impact of surfactant protein-A on ozone-induced changes in the mouse bronchoalveolar lavage proteome. Proteome Sci 7: 12, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hart ML, Ceonzo KA, Shaffer LA, Takahashi K, Rother RP, Reenstra WR, Buras JA, Stahl GL. Gastrointestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury is lectin complement pathway dependent without involving C1q. J Immunol 174: 6373–6380, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hollingsworth JW, Maruoka S, Li Z, Potts EN, Brass DM, Garantziotis S, Fong A, Foster WM, Schwartz DA. Ambient ozone primes pulmonary innate immunity in mice. J Immunol 179: 4367–4375, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huber S, Gagliani N, Zenewicz LA, Huber FJ, Bosurgi L, Hu B, Hedl M, Zhang W, O'Connor W Jr, Murphy AJ, Valenzuela DM, Yancopoulos GD, Booth CJ, Cho JH, Ouyang W, Abraham C, Flavell RA. IL-22BP is regulated by the inflammasome and modulates tumorigenesis in the intestine. Nature 491: 259–263, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones NA, Leport M, Holand T, Vos T, Morgan M, Fink M, Pruniaux MP, Berthelier C, O'Connor BJ, Bertrand C, Page CP. Phosphodiesterase (PDE) 7 in inflammatory cells from patients with asthma and COPD. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 20: 60–68, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jordan JE, Montalto MC, Stahl GL. Inhibition of mannose-binding lectin reduces postischemic myocardial reperfusion injury. Circulation 104: 1413–1418, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kasahara DI, Kim HY, Mathews JA, Verbout NG, Williams AS, Wurmbrand AP, Ninin FM, Neto FL, Benedito LA, Hug C, Umetsu DT, Shore SA. Pivotal role of IL-6 in the hyperinflammatory responses to subacute ozone in adiponectin-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 306: L508–L520, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kunstlinger H, Fassunke J, Schildhaus HU, Brors B, Heydt C, Ihle MA, Mechtersheimer G, Wardelmann E, Buttner R, Merkelbach-Bruse S. FGFR2 is overexpressed in myxoid liposarcoma and inhibition of FGFR signaling impairs tumor growth in vitro. Oncotarget 6: 20215–20230, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lay JC, Alexis NE, Kleeberger SR, Roubey RA, Harris BD, Bromberg PA, Hazucha MJ, Devlin RB, Peden DB. Ozone enhances markers of innate immunity and antigen presentation on airway monocytes in healthy individuals. J Allergy Clin Immunol 120: 719–722, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marquis JF, Kapoustina O, Langlais D, Ruddy R, Dufour CR, Kim BH, MacMicking JD, Giguere V, Gros P. Interferon regulatory factor 8 regulates pathways for antigen presentation in myeloid cells and during tuberculosis. PLos Genet 7: e1002097, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsushita K, Takeuchi O, Standley DM, Kumagai Y, Kawagoe T, Miyake T, Satoh T, Kato H, Tsujimura T, Nakamura H, Akira S. Zc3h12a is an RNase essential for controlling immune responses by regulating mRNA decay. Nature 458: 1185–1190, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nauta AJ, Raaschou-Jensen N, Roos A, Daha MR, Madsen HO, Borrias-Essers MC, Ryder LP, Koch C, Garred P. Mannose-binding lectin engagement with late apoptotic and necrotic cells. Eur J Immunol 33: 2853–2863, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Niepel M, Hafner M, Pace EA, Chung M, Chai DH, Zhou L, Schoeberl B, Sorger PK. Profiles of basal and stimulated receptor signaling networks predict drug response in breast cancer lines. Sci Signal 6: ra84, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogden CA, deCathelineau A, Hoffmann PR, Bratton D, Ghebrehiwet B, Fadok VA, Henson PM. C1q and mannose binding lectin engagement of cell surface calreticulin and CD91 initiates macropinocytosis and uptake of apoptotic cells. J Exp Med 194: 781–795, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ong CB, Kumagai K, Brooks PT, Brandenberger C, Lewandowski RP, Jackson-Humbles DN, Nault R, Zacharewski TR, Wagner JG, Harkema JR. Ozone-induced type 2 immunity in nasal airways. Development and lymphoid cell dependence in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 54: 331–340, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Panneerselvam J, Jin J, Shanker M, Lauderdale J, Bates J, Wang Q, Zhao YD, Archibald SJ, Hubin TJ, Ramesh R. IL-24 inhibits lung cancer cell migration and invasion by disrupting the SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling axis. PLos One 10: e0122439, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pendleton M, Lindsey RH Jr, Felix CA, Grimwade D, Osheroff N. Topoisomerase II and leukemia. Ann NY Acad Sci 1310: 98–110, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pichavant M, Goya S, Meyer EH, Johnston RA, Kim HY, Matangkasombut P, Zhu M, Iwakura Y, Savage PB, DeKruyff RH, Shore SA, Umetsu DT. Ozone exposure in a mouse model induces airway hyperreactivity that requires the presence of natural killer T cells and IL-17. J Exp Med 205: 385–393, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poeter M, Brandherm I, Rossaint J, Rosso G, Shahin V, Skryabin BV, Zarbock A, Gerke V, Rescher U. Annexin A8 controls leukocyte recruitment to activated endothelial cells via cell surface delivery of CD63. Nat Commun 5: 3738, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prado C, Contreras F, Gonzalez H, Diaz P, Elgueta D, Barrientos M, Herrada AA, Lladser A, Bernales S, Pacheco R. Stimulation of dopamine receptor D5 expressed on dendritic cells potentiates Th17-mediated immunity. J Immunol 188: 3062–3070, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shao H, Peng T, Ji Z, Su J, Zhou X. Systematically studying kinase inhibitor induced signaling network signatures by integrating both therapeutic and side effects. PLos One 8: e80832, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stafoggia M, Forastiere F, Faustini A, Biggeri A, Bisanti L, Cadum E, Cernigliaro A, Mallone S, Pandolfi P, Serinelli M, Tessari R, Vigotti MA, Perucci CA. Susceptibility factors to ozone-related mortality: a population-based case-crossover analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 182: 376–384, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stuhlmeier KM, Pollaschek C. Quinacrine but not chloroquine inhibits PMA induced upregulation of matrix metalloproteinases in leukocytes: quinacrine acts at the transcriptional level through a PLA2-independent mechanism. J Rheumatol 33: 472–480, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun S, Zhao G, Liu C, Wu X, Guo Y, Yu H, Song H, Du L, Jiang S, Guo R, Tomlinson S, Zhou Y. Inhibition of complement activation alleviates acute lung injury induced by highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 49: 221–230, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Super M, Thiel S, Lu J, Levinsky RJ, Turner MW. Association of low levels of mannan-binding protein with a common defect of opsonisation. Lancet 2: 1236–1239, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tighe RM, Li Z, Potts EN, Frush S, Liu N, Gunn MD, Foster WM, Noble PW, Hollingsworth JW. Ozone inhalation promotes CX3CR1-dependent maturation of resident lung macrophages that limit oxidative stress and inflammation. J Immunol 187: 4800–4808, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 50.Upcroft P, Upcroft JA. Drug targets and mechanisms of resistance in the anaerobic protozoa. Clin Microbiol Rev 14: 150–164, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vella RE, Pillon NJ, Zarrouki B, Croze ML, Koppe L, Guichardant M, Pesenti S, Chauvin MA, Rieusset J, Geloen A, Soulage CO. Ozone exposure triggers insulin resistance through muscle c-jun N-terminal kinase activation. Diabetes 64: 1011–1024, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Verhein KC, McCaw Z, Gladwell W, Trivedi S, Bushel PR, Kleeberger SR. Novel roles for Notch3 and Notch4 receptors in gene expression and susceptibility to ozone-induced lung inflammation in mice. Environ Health Perspect 123: 799–805, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vukelic M, Qing X, Redecha P, Koo G, Salmon JE. Cholinergic receptors modulate immune complex-induced inflammation in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol 191: 1800–1807, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang G, Zhao J, Jiang R, Song W. Rat lung response to ozone and fine particulate matter (PM2.5) exposures. Environ Toxicol 30: 343–356, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yaxin W, Shanglong Y, Huaqing S, Hong L, Shiying Y, Xiangdong C, Ruidong L, Xiaoying W, Lina G, Yan W. Resolvin D1 attenuates lipopolysaccharide induced acute lung injury through CXCL-12/CXCR4 pathway. J Surg Res 188: 213–221, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang PX, Cheng J, Zou S, D'Souza AD, Koff JL, Lu J, Lee PJ, Krause DS, Egan ME, Bruscia EM. Pharmacological modulation of the AKT/microRNA-199a-5p/CAV1 pathway ameliorates cystic fibrosis lung hyper-inflammation. Nat Commun 6: 6221, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zou C, La Bonte LR, Pavlov VI, Stahl GL. Murine hyperglycemic vasculopathy and cardiomyopathy: whole-genome gene expression analysis predicts cellular targets and regulatory networks influenced by mannose binding lectin. Front Immunol 3 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.