Abstract

DNA replication precisely duplicates the genome to ensure stable inheritance of genetic information. Impaired licensing of origins of replication during the G1 phase of the cell cycle has been implicated in Meier-Gorlin syndrome (MGS), a disorder defined by the triad of short stature, microtia, and a/hypoplastic patellae. Biallelic partial loss-of-function mutations in multiple components of the pre-replication complex (preRC; ORC1, ORC4, ORC6, CDT1, or CDC6) as well as de novo stabilizing mutations in the licensing inhibitor, GMNN, cause MGS. Here we report the identification of mutations in CDC45 in 15 affected individuals from 12 families with MGS and/or craniosynostosis. CDC45 encodes a component of both the pre-initiation (preIC) and CMG helicase complexes, required for initiation of DNA replication origin firing and ongoing DNA synthesis during S-phase itself, respectively, and hence is functionally distinct from previously identified MGS-associated genes. The phenotypes of affected individuals range from syndromic coronal craniosynostosis to severe growth restriction, fulfilling diagnostic criteria for Meier-Gorlin syndrome. All mutations identified were biallelic and included synonymous mutations altering splicing of physiological CDC45 transcripts, as well as amino acid substitutions expected to result in partial loss of function. Functionally, mutations reduce levels of full-length transcripts and protein in subject cells, consistent with partial loss of CDC45 function and a predicted limited rate of DNA replication and cell proliferation. Our findings therefore implicate the preIC as an additional protein complex involved in the etiology of MGS and connect the core cellular machinery of genome replication with growth, chondrogenesis, and cranial suture homeostasis.

Introduction

Replication of DNA during eukaryotic cell division is an essential process, which requires a complex apparatus of conserved proteins operating under tight temporal and regulatory control. Although the duplication process itself occurs during the S (synthesis) phase of the cell cycle, the initial components assemble on DNA much earlier, during the late mitotic stages and in G1 phase.

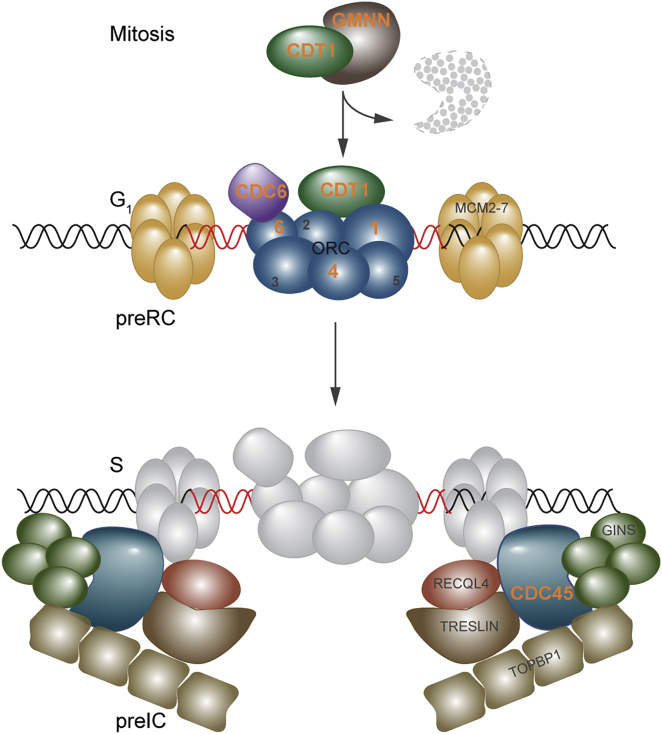

In the first stage, the pre-replication complex (preRC) is formed by the 6-subunit origin recognition complex (ORC) binding to replication origins distributed throughout the genome (Figure 1).1 ORC recruits CDT1 and CDC6, which leads to the binding of the inactive MCM2-7 helicase as a double hexamer at replication origins.2 At the G1/S transition, the pre-initiation complex (preIC) proteins assemble in a two-step DDK- and CDK-dependent manner3 and through interaction with the MCM helicase enable binding by the CDC45 and GINS1-4 proteins. This creates the activated CMG helicase, an 11-subunit complex that possesses essential DNA unwinding activity, allowing polymerases access to DNA and enabling replication to commence.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 CDC45 has single-stranded DNA binding activity, facilitating DNA strand displacement at the replication fork.9 Hence CDC45 plays a central role in both initiation of DNA replication origin firing (preIC) and ongoing DNA synthesis (CMG helicase), and genetic studies demonstrate that it is essential in both yeast and mice.10, 11, 12, 13, 14 Both in vitro and in vivo data indicate that CDC45 is loaded onto chromatin specifically in the S phase of the cell cycle, after the assembly of the preRC complexes.11, 14, 15, 16, 17

Figure 1.

Pre-replication and Pre-initiation Complexes in DNA Replication, Showing Components Mutant in MGS

Previously identified MGS-associated genes (labeled with orange lettering) encode members of the pre-replication complex (preRC, upper cartoon); these components are involved in the licensing of replication origins during the G1 phase of the cell cycle. GMNN acts during other cell cycle phases to inhibit CDT1 but is degraded in late M (mitosis) phase (indicated by GMNN with dashed outline), permitting free CDT1 to participate in origin licensing in G1. In contrast, CDC45 contributes at the next major step in DNA replication, in which the coordinated action of many replication initiation factors including RECQL4 forms the pre-initiation complex (preIC, lower cartoon) to support the interaction of CDC45 and GINS1-4 with the MCM helicase, converting the latent form to an active helicase and initiating the unwinding of DNA.

Several Mendelian syndromes have been associated with mutations in components of the DNA replication machinery. Meier-Gorlin syndrome (MGS [MIM: 224690]) is characterized by short stature, microtia (small ears), and aplasia or hypoplasia of the patellae.18 Biallelic mutations in multiple components of the preRC (ORC1 [MIM: 601902], ORC4 [MIM: 603056], ORC6 [MIM: 607213], CDT1 [MIM: 605525], and CDC6 [MIM: 602627]) were identified in individuals with MGS,19, 20, 21 and among them, mutations in these genes account for approximately 70% of cases.22 Recently, de novo mutations in three individuals were reported in the CDT1 inhibitor, GMNN (MIM: 602842), resulting in the omission of a degron domain that stabilizes GMNN levels and is consequently predicted to impair licensing in subject cells.23, 24

Here, we provide genetic and functional evidence that mutations in CDC45 (MIM: 603465) cause human disease. We describe 15 individuals with biallelic partial loss-of-function mutations in CDC45 and demonstrate a phenotype that extends from syndromic craniosynostosis to classical MGS.

Subjects and Methods

Clinical Studies

The clinical studies were approved by Oxfordshire Research Ethics Committee B (reference C02.143), London Riverside Research Ethics Committee (reference 09/H0706/20), Scottish Multicenter Research Ethics Committee (04:MRE00/19), and the Medisch Ethische Toetsingscommissie of the Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC) (P14-029). Subjects were enrolled into the craniosynostosis cohort based on referral from a craniofacial unit or clinical genetics department, with craniosynostosis proven on either plain radiographs or computed tomography (CT) of the skull. Individuals in the MGS cohort were clinically diagnosed by the referring clinician; in those from whom clinical data were available, all demonstrated hypoplastic or absent kneecaps, small or simple ears, and facies typical of MGS (small mouth and full lips). All participants gave informed consent, and separate permission was obtained for publication of clinical photographs.

Whole-Genome and Exome Sequencing

Subjects P1 (family 1, II-3 in Figure 2A) and P2 (family 2, II-1 in Figure 2A), from a craniosynostosis cohort, were subjected to whole-genome sequencing and exome sequencing, respectively. Exome sequencing of subject P4 (family 4, II-1 in Figure 2A) was undertaken by Oxford Gene Technology, as part of a study of subjects with primordial dwarfism (characterized by in utero growth retardation and postnatal head circumference and height more than 4 SDs below the age- and gender-matched population mean). Exome sequencing of family 12 was undertaken as part of a diagnostic approach to mutation identification. All details of sequencing library preparations and platforms, as well as software tools for mapping, alignment, and variant calling and prioritization, are presented in Table S1.

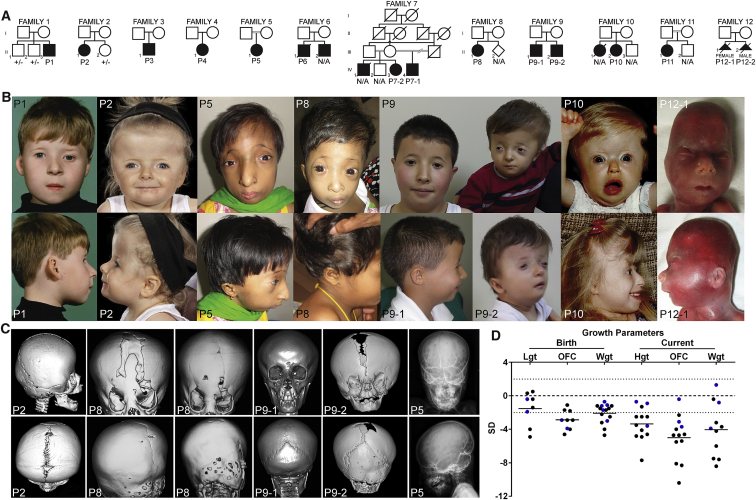

Figure 2.

Clinical Features of Individuals with Mutations in CDC45

(A) Pedigrees of families segregating mutations in CDC45. Note consanguinity in families 5, 7, and 11 and that all parents and unaffected siblings available for testing were heterozygous for only one variant, consistent with autosomal-recessive inheritance.

(B) Facial appearance of individuals with CDC45 mutations. Many individuals demonstrate the facial characteristics of MGS including microtia, small mouth, full lips, and micrognathia, but there is a marked spectrum of severity across the cohort. Note the consistent appearance of thin eyebrows.

(C) CT head scans and plain skull radiographs of individuals with CDC45 mutations demonstrating premature fusion of cranial sutures. Note the discordance in suture fusion between sibs P9-1 and P9-2. Imaging of P8 indicates progressive suture closure (P8 left panel, age 2 years 4 months; P8 right panel, age 3 years 8 months). Skull radiography of P5 demonstrates a beaten-copper appearance of the skull.

(D) Individuals with CDC45 mutations have below-average stature and many exhibited intrauterine growth retardation and microcephaly (both in utero and postnatally). Abbreviations are as follows: Lgt, length; OFC, occipitofrontal circumference; Wgt, weight; Hgt, height. Blue indicates individuals derived from craniosynostosis cohort; black indicates individuals derived from MGS cohort.

Genomic Analysis of CDC45

To investigate further the significance of the CDC45 variants, primers were designed for amplification of genomic DNA (GenBank: NT_011520.13) and cDNA (GenBank: NM_003504.4; see Supplemental Data, Note on accession numbers for CDC45). We used dideoxy sequencing to confirm the identity of CDC45 variants identified during whole-genome and exome sequencing and analyzed their segregation in parents and unaffected siblings. Primer sequences and experimental conditions used for PCR amplification and sequencing are provided in Table S2. To analyze a larger number of individuals for CDC45 mutations, we used Fluidigm/Ion Torrent resequencing or dideoxy sequencing, respectively, to screen CDC45 in DNA panels from subjects with craniosynostosis (467 samples) or MGS (34 samples), in whom mutations in known causative genes had not previously been identified (Table S2). Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) was used to confirm the intragenic deletion in family 12 (Table S2).

Analysis of CDC45 Splicing

Total RNA was extracted from lymphoblastoid cell lines using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and the RNeasy kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was removed by treatment with DNase I (QIAGEN). cDNA was generated using random oligomer primers and superscript II (Thermo Fisher) or the RevertAid First Strand Synthesis kit (Fermentas). Primers used for RT-PCR and qRT-PCR are listed in Table S3. cDNA levels were quantified by qRT-PCR using Brilliant II SYBR green qPCR master mix with passive ROX reference dye (Agilent Technologies) on the ABI Prism HT7900 Sequence Detection System. The relative expression of target genes to a control was calculated using the comparative CT method (2−ΔΔCT).

Cell Lines, Chemicals, Plasmids, and Transfections

Lymphoblastoid cell lines were cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. Amniocytes were cultured in Amnio-MAX C-100 Complete Medium (GIBCO). All reagents were purchased from Life Technologies unless otherwise stated.

Antibodies and Western Blotting

Whole-cell lysate was prepared using urea buffer (9 M urea, 50 mM Tris HCl [pH 7.3], 150 mM β-mercaptoethanol). Primary antibodies used were mouse anti-human CDC45 (sc55569, Santa Cruz Biotech) at 1:1,000 and mouse anti-human TUBULIN (B512, Sigma) at 1:10,000.

Protein Alignments and Structure Prediction

Clustal Omega25 was used to generate multi-sequence alignments of orthologous CDC45 proteins. GenBank accession numbers are as follows: Homo sapiens, NP_003495.1; Pan troglodytes, XP_009436063.1; Canis lupus, XP_543547.3; Mus musculus, NP_033992.2; Gallus gallus, XP_415070.2; Danio rerio, NP_998551.1; Drosophila melanogaster, NP_569880.1; Anopheles gambiae, XP_320573.1; Caenorhabditis elegans, NP_497756.2; Saccharomyces cerevisiae, NP_013204.1; and Schizosaccharomyces pombe, NP_594693.1. The structural model of human CDC45 was modeled on the 3.7 Å cryo-electron microscopy structure of S. cerevisiae Cdc45.26 It was created using Modeler27 and is presented using Pymol (Schrodinger).

Results

Exome and Genome Sequencing and Targeted Resequencing Identify Biallelic Variants in CDC45

As part of a large multi-disease study,28 clinical whole-genome sequencing of a trio comprising a male individual (P1, family 1; II-3 in Figure 2A) with syndromic unilateral coronal craniosynostosis and his unaffected parents initially identified several candidate variants for further scrutiny. These were a single de novo missense mutation (FLRT1 [MIM: 604806]; c.137C>T, p.Thr46Met [GenBank: NM_013280.4]), two very rare (absent in dbSNP135, ESP, or 1000 Genomes) hemizygous nonsynonymous variants (OPHN1 [MIM: 300127]; c.1559C>T, p.Thr520Ile [GenBank: NM_002547.2]; and GEMIN8 [MIM: 300962]; c.500G>A, p.Arg167His [GenBank: NM_017856.2]), and two very rare compound heterozygous genotypes: CDC45 c.[318C>T; 677A>G], p.[Val106= ; Asp226Gly] and MYO10 (MIM: 601481) c.[1491G>A; 5459A>C], p.[Glu497= ; His1820Pro] (GenBank: NM_012334.2). FLRT1 was initially prioritized for further analysis, but resequencing this gene in a panel of 230 individuals with craniosynostosis revealed no further mutations. During concurrent exome sequencing of female subject P2 (family 2; II-1 in Figure 2A) with syndromic bilateral coronal craniosynostosis, variant analysis under a recessive model of inheritance also identified two very rare predicted missense changes in CDC45 (c.226A>C [p.Asn76His] and c.469C>T [p.Arg157Cys]); dideoxy sequencing of parental samples showed that the CDC45 variants were present in a compound heterozygous (biallelic) state. Given the identification of two individuals with unilateral or bilateral coronal or craniosynostosis, each of whom had two rare biallelic variants in CDC45 (Table 1), resequencing of CDC45 was undertaken in a further 467 subjects with craniosynostosis. This revealed one further individual (P3, family 3; II-1 in Figure 2A) with two rare CDC45 variants (Table 1), which analysis of parental samples showed were also biallelic. Consistent with a causal role in the disease state, three unaffected siblings of P1 and P2 inherited different combinations of CDC45 alleles (Figure 2A).

Table 1.

Mutations Identified in CDC45

| Subject | Country of Origin | Allele 1 | Allele 2 | Segregation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1a | UK | c.318C>T, p.Val106= (SE) | c.677A>G, p.Asp226Gly | Het, M, P, (2)b |

| P2 | UK | c.226A>C, p.Asn76His | c.469C>T, p.Arg157Cys | Het, M, P, (1) |

| P3 | USA | c.653+5G>A (SE) | c.1487C>T, p.Pro496Leu | Het, M, P |

| P4 | Bangladesh | c.1A>C, p.Met1? | c.1388C>T, p.Pro463Leu | nps |

| P5 | Bangladesh | c.1270C>T, p.Arg424∗ | c.1388C>T, p.Pro463Leu | Het, M, P |

| P6 | Belgium | c.791C>A, p.Ser264Tyr | c.791C>A, p.Ser264Tyr | Hom, M, P |

| P7-1 | Egypt | c.1660C>T, p.Arg554Trp | c.1660C>T, p.Arg554Trp | Hom, M (P deceased) |

| P7-2 | Egypt | c.1660C>T, p.Arg554Trp | c.1660C>T, p.Arg554Trp | Hom, M, P |

| P8 | Sri Lanka | c.1388C>T, p.Pro463Leu | c.1532delC, p.Pro511Glnfs∗36 | Het, M, P |

| P9-1 | Turkey | c.203A>G, p.Gln68Arg (SE) | c.333C>T, p.Asn111= (SE) | Het, M, P |

| P9-2 | Turkey | c.203A>G, p.Gln68Arg (SE) | c.333C>T, p.Asn111= (SE) | Het, M, P |

| P10c | New Zealand | c.[464A>G; 961C>A], p.[Glu155Gly; Pro321Thr] | c.1440+14C>T (SE) | Het, M, P |

| P11 | Egypt | c.1660C>T, p.Arg554Trp | c.1660C>T, p.Arg554Trp | Hom, M, P |

| P12-1 | the Netherlands | c.(485+1_486−1)_(630+1_631−1)del, p.Ile115_Glu162del | c.893C>T, p.Ala298Val | Het, M, P |

| P12-2 | the Netherlands | c.(485+1_486−1)_(630+1_631−1)del, p.Ile115_Glu162del | c.893C>T, p.Ala298Val | Het, M, P |

Refseq accession: NM_003504.4. Abbreviations are as follows: SE, splicing effect; Het, compound heterozygous in affected individual; nps, no parental samples available; M, mutation identified in mother; P, mutation identified in father; Hom, homozygous in affected individual.

Mutation previously reported28 (note mutation numbering differs in previous publication due to different reference transcript).

Numbers in parentheses indicate number of clinically unaffected siblings shown not to have inherited the compound heterozygous genotype.

Subject P10 segregates two rare missense variants on one allele, in combination with a splice region mutation on the second allele. Based on conservation of CDC45 residues across different species, the p.Pro321Thr variant is more likely to be deleterious as this residue is conserved through to S. cerevisiae (Figure 3).

In addition to craniosynostosis, clinical features variably present in individuals P1–P3 included mild short stature, microcephaly, and ear anomalies (Figure 2B, Table 2). In view of the previous association of replication-associated genes with growth restriction,19, 20, 21, 22 we interrogated exome-sequencing data from a cohort of individuals with primordial dwarfism (n = 52) for variants in CDC45. One individual (P4, family 4; II-1 in Figure 2A), diagnosed with MGS, was found to harbor two rare CDC45 variants (Table 1).

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics of Individuals with Mutations in CDC45

| Subj. | Consan | Gender |

Birth, SD |

Current Exam, SD |

MGS Features |

Thin Eyebrows | Develop. Delay | Craniosynostosis | Other Clinical Features | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gest. | Lgt (cm) | OFC (cm) | Wgt (kg) | Age | Hgt (cm) | OFC (cm) | Wgt (kg) | Microtia | A/Hypoplastic Patella | |||||||

| P1 | N | M | 40 | NA | NA | −0.7 (3.2) | 28 years | −0.7 (173) | −0.4a (55.5) | +1.3 (85.7) | + | − | + | none | right unicoronal | urethral stricture, mild 2/3/4 syndactyly of hands |

| P2 | N | F | 38 | NA | NA | −1.2 (2.5) | 4 years 4 months | −0.9 (100) | −3.1 (47.6) | −0.8 (15.3) | − | − | + | none | bicoronal | anterior anus, bilateral strabismus |

| P3 | N | M | 38 | NA | NA | −1.7 (2.4) | 16 years 3 months | −3.6 (147) | −3.7 (50.5) | −3.9 (35.3) | + | − | + | mild | bicoronal | R choanal atresia, high palate, imperforate anus, vesicoureteral reflux, hypospadias, 2-3 syndactyly of toes, scoliosis, C1-C3 and C4-C7 fusion, bilateral radial head dislocation |

| P4 | N | F | 36 | NA | −2.9 (28.5) | −3.2 (1.45) | 5 years 5 months | −7.7b (48) | −8.3b (33) | −6.1 (9.9) | + | + | + | severe | large anterior fontanelle (X-ray) | cleft palate, exorbitism, bilateral radial head dislocation, thoracic vertebral segmentation defects, digital clubbing, pulmonary hypoplasia, anterior anus, cliteromegaly |

| P5 | 3rd | F | 40 | NA | NA | −4.7 (1.5) | 6 years | −4.6 (93) | −8.1 (42.5) | −7.5 (9.2) | + | + | + | none | copper-beating on skull radiograph | cleft palate, bowed legs, anorectal malformation |

| P6 | N | M | 34 | 0.3 (46.5) | −1.1 (30) | −1.2 (1.88) | 22 years | −4.8 (145) | −5.4 (48) | −8.4 (32.5) | + | + | + | severe | bicoronal and bilambdoid | AV block grade II, SN hearing loss, joint laxity, chiari I malformation, myopia |

| P7-1 | 1st | M | term | −4 (43) | −4 (30) | −2.5 (2.4) | 3 years 6 months | −4.1 (83) | −5.5 (44) | −6 (8.5) | + | + | + | none | coronal, sagittal | anal stenosis, budlike mouth, ASD, VSD, undescended testes, hypospadius |

| P7-2 | 1st | F | term | −4.9 (41) | −2.9 (31) | −2.2 (2.45) | 5 years 2 months | −3.5 (94) | −4 (47) | −4.2 (11.5) | + | + | + | none | coronal, sagittal | AV canal |

| P8 | N | F | 37 | −0.4 (47) | −4.6 (27) | −1.7 (2.14) | 4 years | −4.9 (82) | −10.4 (38.6) | −7.6 (7.5) | + lowset | NA | + | NA | bicoronal and bilambdoid, broad patent sagittal with bifid metopic suture | vestibular, anterior anus, hearing mild conduction delay, proptosis, VSD, duodenal stenosis |

| P9-1 | N | M | 42 | −1.4 (50) | NA | −1.5 (3.2) | 7 years | −1.3 (115) | −2.3 (50) | −0.4 (22) | + | + | + | none | none | high arched palate, micropenis |

| P9-2 | N | M | term | 0.5 (52) | −1.7 (33) | −1.2 (3.0) | 16 months | −2.5 (73) | −4.7 (43) | −3.7 (7.5) | + | N/A | + | none | bicoronal with widely patent metopic and sagittal sutures | none |

| P10 | N | F | 36 | NA | −1.8 (30) | −1.5 (2.04) | 25 years | −2.5 (149) | −4.7 (49) | NA | + | + | + | none | bicoronal | high palate, hearing loss, breast agenesis, heart block |

| P11 | 1st | F | 40 | NA | NA | −4.0 (1.75) | 4 years 7 months | −2.5 (95) | −4.6 (−4.6) | −3.2 (12) | + | + | + | none | coronal and lambdoid | small ASD |

| P12-1 | N | F | 22+3c | −1.9 (25) | −3.9 (15.5) | −3.0 (0.33) | TOP | + | not reported | + | N/A | yes | anterior anus | |||

| P12-2 | N | M | 30+5c | −0.4 (39.1) | −2.9 (24) | −1.1 (1.15) | TOP | lowset | not reported | + | N/A | bicoronal, partial lambdoid, squamous and lateral parts of the occipital bone | pre-axial polydactyly of both hands, small VSD, meconium peritonitis, multiple nodules of ectopic thymic tissue, high palate | |||

Abbreviations are as follows: NA, not available; TOP, termination of pregnancy; SD, standard deviation. Calculated using LMSgrowth56 and adjusted for sex and gestation.

Measurement at 15 years of age, after surgery.

Measurement at 5 months of age.

Z-scores were calculated using the Fenton 2013 Growth Calculator.57

Given the presentation of subject P4 with MGS, we then undertook dideoxy sequencing of 34 further subjects with MGS, in whom causative mutations had not previously been found in preRC components. This identified seven further families (families 5–11) (Table 1), in which nine individuals have biallelic mutations in CDC45. All variants had either a very low allele frequency in control populations with no homozygotes, appropriate for a rare recessively inherited Mendelian disorder, or were absent from the ExAC dataset. The autosomal-recessive inheritance was confirmed by appropriate segregation in all parents where available (Figure 2A, Table 1).

Concurrently, exome sequencing was undertaken in a nonconsanguineous Dutch family (family 12) in which two consecutive fetuses displayed craniosynostosis and additional anomalies in utero. The recurrence within the family suggested an autosomal-recessive inheritance, but no candidate disease genes were identified after bioinformatic analysis and filtering of the exome data. Given the previous findings, CDC45 and other autosomal-recessive craniosynostosis disorder-associated genes were manually re-examined; this identified a single paternally transmitted missense variant in CDC45: c.893C>T encoding p.Ala298Val. Visual analysis of the sequencing reads using Integrated Genomics Viewer29 suggested lower coverage of exon 5 in both the two affected samples and the maternal sample compared with the paternal sequencing (Figure S1A). Analysis using MLPA probes confirmed a deletion encompassing only exon 5 of CDC45 in these three samples (Figure S1B). This would be predicted to delete a highly conserved portion of the protein, but translation would remain in-frame and therefore transcripts from this allele would not be predicted to undergo nonsense-mediated decay. This was confirmed by analysis of cDNA derived from maternal blood (Figure S1C).

The Human CDC45 Mutational Spectrum Indicates Partial Loss of Protein Function

CDC45 is an essential component in the preIC that establishes active replication at licensed origins (Figure 1). The majority of variants identified in CDC45 lead to amino acid substitutions (Figure 3A), which bioinformatic analysis predict to be damaging; we examined conservation of these residues as a measure of deleteriousness and found all are conserved in vertebrates, with residues at several sites conserved through to yeasts (Figure 3B).

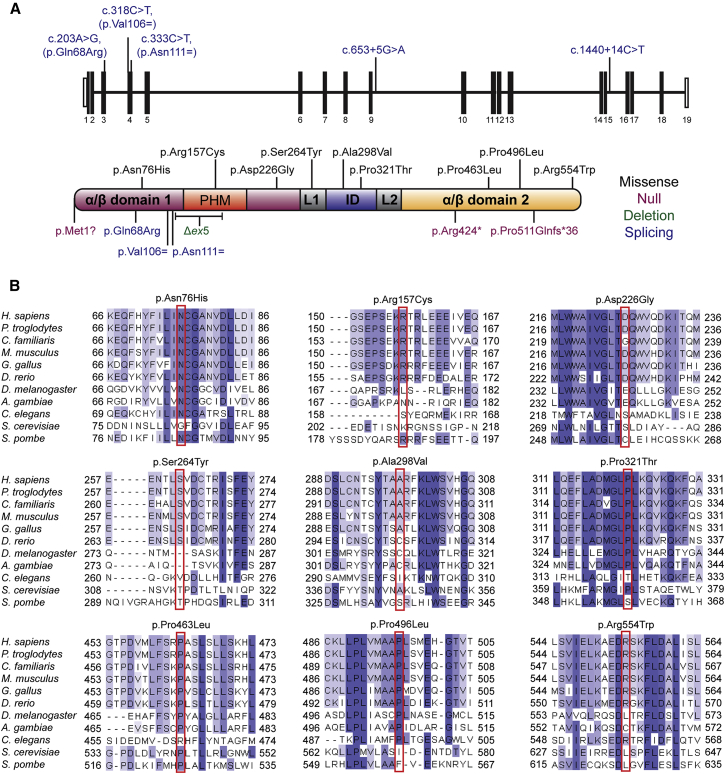

Figure 3.

Mutations in CDC45 and Conservation of Substituted Residues in Orthologous Proteins

(A) Mutations identified in CDC45 include variants predicted or shown to affect splicing (blue, position in gene shown in upper panel), predicted missense substitutions (black), or truncating mutations (purple). Δex5 refers to the intragenic deletion encompassing exon 5 of CDC45 in family P12 (green). Mutations do not cluster within any specific domain of CDC45. Domain architecture of human CDC45 indicated as described in Yuan et al.26 The two alpha-beta domains are shown in purple and orange, respectively. The protruding helical motif (PHM) inserted in the first alpha-beta domain is shown in red. The middle all-helix interdomain (ID) is shown in blue, and the two linkers (L1 and L2) are shown in gray.

(B) Clustal Omega alignments of eukaryotic CDC45 proteins indicate mutated residues are well conserved, with several residues (such as Asn76, Arg157, Pro321, and Pro463) conserved as distantly as fungi. Blue shading indicates proportion of conserved amino acids.

One conserved substitution, c.203A>G [p.Gln68Arg], occurred at the penultimate nucleotide in exon 3, suggesting that it might also impact splicing in addition to any protein-level consequence (see next section). The three subjects (P4, P5, P8) with a truncating/null mutation (nonsense, frameshift deletion, or initiation codon mutation) on one allele all segregate an identical missense variant, c.1388C>T [p.Pro463Leu], present on the trans allele; given the South Asian ancestry in all three subjects (ExAC South Asian allele frequency 0.000062), the presence of this variant is compatible with a founder effect.

All individuals had at least one allele compatible with some residual function; none were biallelic for null mutations, consistent with the early embryonic lethality reported in a Cdc45 knockout mouse (Cdc45 homozygotes die before E7.5, due to impaired proliferation of the inner cell mass13). Individuals who were compound heterozygotes for a loss-of-function and a substitution allele (those encoding p.Pro463Leu or p.Ala298Val) were particularly severely affected.

Structural Consequences of CDC45 Mutations

Missense mutations did not cluster within a specific domain of the protein (Figure 3A). However, a homology model derived from the recent high-resolution cryo-electron microscopy study of the yeast CMG helicase complex26 demonstrated that a number of substituted residues are located within the core of the CDC45 protein (Figures 4A and 4B). This core region corresponds to the known catalytic site of the bacterial RecJ orthologs of CDC45 and its DHH phosphoesterase homologs.31, 32 Such substitutions would therefore be likely to perturb protein stability. In particular, the recurrent p.Pro463Leu substitution replaces a conserved proline residue with a likely essential role in N-capping of an alpha helix (Figure 4C). Likewise, within the protein core, the p.Asn76His substitution is expected to introduce a positive charge within, and thus disrupt, the predicted divalent cation coordination sphere present in many members of the DHH phosphoesterase superfamily (Figure 4D).33, 34, 35 Predictions of functional consequences for point mutations at other sites in the homology model were not possible, aside from the p.Pro321Thr substitution that is expected to disrupt the interaction of CDC45 with MCM2 (Figure 4E).

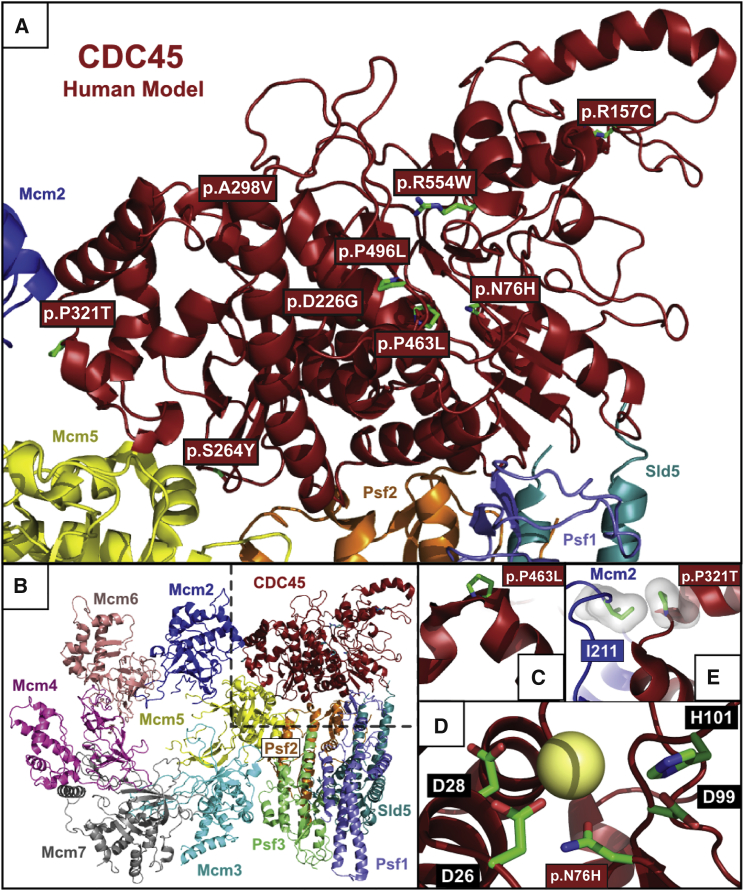

Figure 4.

Structural Consequences of CDC45 Substitutions

(A) Structural model of human CDC45 demonstrating the spatial distribution of substitutions in the protein. Red boxes indicate position of missense mutations, with side chains of these substituted residues displayed in green.

(B) CDC45 in context of the S. cerevisiae CMG complex from the 3.8 Å cryo-electron microscopy structure.26

(C–E) Modeling of substitutions that cluster in the central core of CDC45.

(C) Proline 463 is an evolutionarily conserved position, with an essential role in N-capping of the alpha-helix localized between Pro542 and Cys556 in yeast Cdc45 (Pro463 and Phe477 in human). Given the location of Pro463 in the CDC45 structural core, the substitution to leucine is predicted to have severe effects on the stability of this helix53 and therefore overall stability of the protein.

(D) Asn76 is predicted to be part of the divalent cation coordination sphere. Although the DHH domain of CDC45 is currently considered to be catalytically inert,30, 54 residues Asp26, Asp28, Asp99, and His101, corresponding to the catalytic core of prokaryotic RecJ exonucleases and the DHH superfamily of phosphoesterases, are conserved (highlighted by black boxes).26, 32, 55 This suggests the continued presence of a divalent cation at this position (predicted divalent cation indicated by yellow sphere). Asn76 is therefore thought to be part of a divalent cation coordination sphere which, in other homologs, is the phosphoesterase catalytic center. The substitution to histidine would introduce a positive charge into the putative divalent cation coordination sphere, thereby disrupting the network of interactions among water molecules, charged residues and divalent cation/s observed in different members of the superfamily of DHH phosphoesterases.33, 34, 35

(E) Proline 321 (corresponding to Pro369 in yeast) is a key part of the CDC45 interacting surface with Mcm2,26 given that in yeast it lies within 3.5 Å of Ile289 of Mcm2 (corresponding to Ile211 in human MCM2). Additionally, this proline has a key role in the N-capping of the alpha-helix localized between Leu370 and Gln374 in yeast Cdc45.53 Therefore, substitution of proline 321 to threonine is likely not only to have effects on CDC45-MCM2 interaction but also on CDC45 protein stability. The interacting pair Pro321 (in CDC45) and Ile211 (corresponding to Ile289 in Mcm2) are shown in sticks (green) inside their van der Waals surfaces.

Hypomorphic CDC45 Mutations Act by Disrupting Transcript Splicing and Reducing Protein Levels

Five of the alleles (in families 1, 3, 9, and 10) were hypothesized to affect splicing (Tables S4 and S5) and this was confirmed in the three samples available for extraction of RNA, in which we analyzed the effects of putative splicing mutations on cDNA.

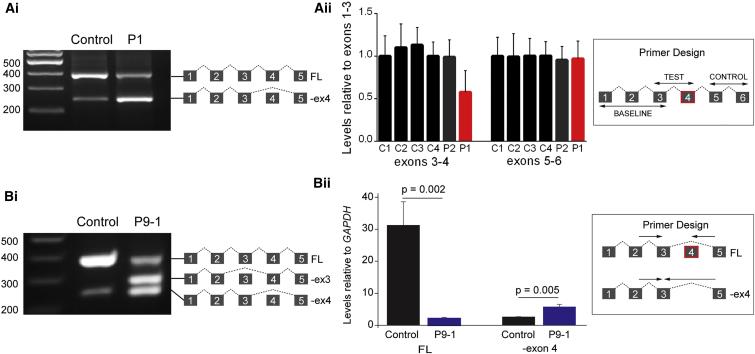

In two families (families 1 and 9), the only putative second disease variants present after filtering to remove common variants were synonymous, which generally are less likely to be pathogenic. These two variants (c.318C>T [p.Val106=] and c.333C>T [p.Asn111=]) lie close together in exon 4, which is skipped for transcripts in which alternative splicing from exon 3 directly to exon 5 generates a naturally occurring shorter isoform.36 This evolutionarily conserved instance of exon skipping is predicted to generate an in-frame protein product that lacks part of the highly conserved DHH phosphoesterase domain.32 RNA derived from these subjects (P1: c.318C>T, P9-1: c.333C>T) exhibited an increased ratio of exon 3/5 transcript to exon 3/4/5 cDNA product compared to control subjects (Figure 5). In silico tools (Human Splice Finder and Sroogle)37, 38 predict the c.333C>T variant to disrupt exon splice enhancer sites and the c.318C>T variant to enhance potential cryptic exonic splice silencer sites, both mechanisms by which these variants may promote the skipping of exon 4 (Table S5). The apparently nonsynonymous variant c.203A>G (mutation present in P9-1 and P9-2), which lies at the penultimate nucleotide of exon 3, was also shown to cause complete skipping of exon 3 in the cell line from P9-1 (Figure 5Bi).

Figure 5.

Synonymous CDC45 Variants Alter Levels of Alternative Splicing of Exon 4 in Lymphoblastoid Cell Lines

(A) The synonymous variant c.318C>T present in P1 increases the ratio of exon3/5 transcript compared to controls. (i) RT-PCR demonstrating an enrichment in the exon3/5 lower band. (ii) Results of qRT-PCR to assay the relative amounts of exon 4 in P1, P2, and four unaffected control subjects. Products were amplified with primers in exons 3 and 4 and compared with products generated from primers in exons 1 and 3. cDNA from P1 showed a 0.43-fold reduction in exons 3–4 relative to exons 1–3. Levels of exons 5–6 compared with exons 1–3 are also shown, no differences were observed. Error bars, standard deviation. n = 3 experimental replicates of qPCR.

(B) The synonymous variant c.333C>T together with the trans c.203A>G (p.Glu68Arg) splice site variant identified in P9-1 and P9-2 increases aberrant splicing across this region of the gene. (i) RT-PCR demonstrating an increase in exon3/5 transcript and the creation of a novel transcript where exon 3 has been skipped due to the c.203A>G mutation. (ii) Total RNA extracted from LCLs derived from P9-1 was analyzed by qRT-PCR. Full-length-only transcripts were amplified using a forward primer (F 2/3) spanning the exon 2-exon 3 boundary and a reverse primer (R 4/5) spanning the exon 4-exon 5 boundary. The transcript missing exon 4 was specifically amplified using the F 2/3 primer paired with a reverse primer (R 3/5) which spanned the exon 3-exon 5 boundary. Total amount of minus exon 4 (−Ex4) and full-length (FL) transcript was normalized to GAPDH for P9-1 and control. Error bars indicate standard deviation (n = 3 experiments). A two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test was performed and p values are indicated.

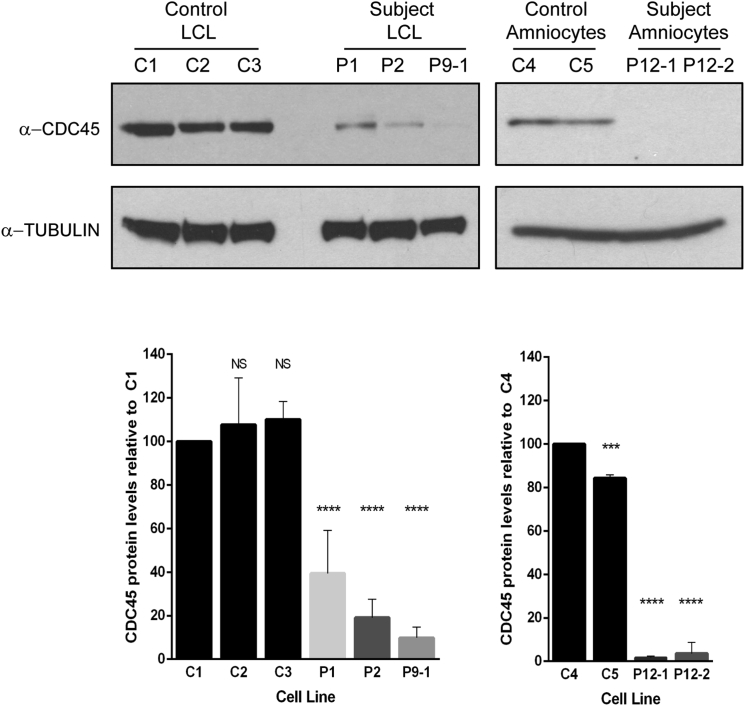

We next sought to investigate the consequence of these mutations on the CDC45 protein by assessing protein levels in cells from five subjects by immunoblotting for endogenous CDC45 (Figure 6). In the three cell lines available from affected individuals (lymphoblastoid cell lines derived from P1, P2, and P9-1) and in primary amniocytes derived from P12-1 and P12-2, CDC45 levels were significantly lower than in multiple control cells or cell lines (p < 0.0001). Moreover, CDC45 levels were reduced below 50% in all cases, indicating a contribution from both alleles to reduced protein levels. This suggests that the missense variants present in these cells or cell lines (P1, p.Asp226Gly; P2, p.Asn76His and p.Arg157Cys; P12, p.Ala298Val) each result in destabilization of CDC45 protein.

Figure 6.

CDC45 Protein Levels Are Significantly Reduced in Lymphoblastoid Cell Lines and Primary Amniocytes

Cell lines from affected individuals (P1, P2, P9-1) and amniocytes derived from affected fetuses (P12-1 and P12-2) demonstrate a significant reduction in endogenous CDC45 levels compared to three independent controls (LCL samples: one-way ANOVA comparing all LCL samples against C1; error bars indicate standard deviation; NS, p > 0.01, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, n = 5 biological replicates; amniocyte samples: one-way ANOVA comparing all amniocyte samples against C4. ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, n = 3 biological replicates).

Taken together with the nature of the mutations identified, the key demonstration of decreased cellular levels in several affected individuals confirm that variants identified were pathogenic and the mutations would most likely result in destabilization of CDC45 protein.

Spectrum of Phenotypes Associated with CDC45 Mutations and Correlation with Genotype

In total we identified 15 subjects from 12 families with variants in CDC45 (Table 1, Figure 2A). Individuals with biallelic CDC45 mutations exhibit substantial variation in severity, in part explained by ascertainment from two distinct cohorts of affected subjects (craniosynostosis for P1–P3 and P12 and MGS for P4–P11). Nevertheless they manifest a recognizable phenotypic spectrum with overlapping clinical features (Table 2, Figures 2B–2D). For example, although subjects P4–P11 all presented with the classical triad of MGS features (short stature from −1.3 to −7.7 SD, microtia, and absent or hypoplastic patellae), craniosynostosis was also frequent, in contrast to MGS associated with mutations in preRC components. The severity of craniosynostosis varied widely from unilateral or bilateral coronal synostosis to multiple suture involvement (Figure 2C). The discordance for craniosynostosis in two siblings with identical mutations (P9-1 and P9-2) indicates that this is not a fully penetrant phenotype. Conversely, individuals with a primary presentation of craniosynostosis also exhibited mild MGS features, such as hypoplastic ears (P1, P3, P12-1), mild short stature, and a similar facial gestalt including a small mouth (Figure 2B). The MGS feature of patellar hypoplasia was, however, not observed in any of the three individuals with craniosynostosis who presented postnatally (P1–P3). Thin eyebrows were present in subjects presenting with either craniosynostosis or MGS, a feature that has not been previously highlighted in these or related developmental disorders. Additionally, anal abnormalities (imperforate anus or anterior placement) were present in seven subjects drawn from both cohorts. Growth failure and microcephaly were evident from birth in almost all subjects (Figure 2D), and both the microcephaly and height reduction were progressive throughout childhood. Carrier parents and heterozygous siblings were phenotypically normal, a point of particular note since CDC45 is located on 22q11.21, within the interval deleted in the 22q11.2 deletion syndromes.39

Discussion

Here we identify multiple mutations in CDC45, implicating its involvement in the pathogenesis of both MGS and craniosynostosis. Previous work had established MGS as a disorder of replication licensing, with biallelic mutations in ORC1, ORC4, and ORC6 and accessory proteins encoded by CDC6 and CDT1. Furthermore, a recent report has identified stabilizing mutations in GMNN, which probably act to inhibit CDT1 and consequently reduce licensing in G1.23 No mutations in any of the MCM subunits have been discovered in individuals with MGS, previously suggesting that MGS was limited to the upstream preRC components; indeed, a founder MCM4 mutation has been described causing a distinct entity—a genome instability syndrome of short stature, adrenal insufficiency, and primary immunodeficiency.40, 41, 42 The identification of CDC45 is therefore surprising, given the well-established function of CDC45 in replication activation and fork progression (Figure 1). Associating CDC45 mutations with MGS therefore expands understanding of the pathogenic basis of MGS, and given the number of individuals reported here, establishes CDC45 as a common cause of MGS syndrome, alongside ORC1 and CDT1. These mutations in individuals with MGS also raise the possibility that mutations in genes coding for other proteins involved in DNA replication may be implicated in MGS and/or craniosynostosis.17, 43, 44, 45

After the initial identification of MGS mutations, several studies have proposed disease mechanisms distinct from the canonical role of the preRC in replication, such as dysregulated cilia formation or centrosome duplication.46, 47 Our identification of MGS mutations in distinct replication machinery, with similar growth and clinical characteristics seen in the preRC MGS-affected individuals (including those with GMNN mutations), strongly favors a replication-based etiology for MGS. Notably, biallelic mutations in the helicase RECQL4 (MIM: 603780, also required for preIC formation and replication initiation44, 45) can cause a phenotype that overlaps with MGS; RAPADILINO syndrome (MIM: 266280) is characterized by growth retardation and patellar agenesis, although diarrhea, palatal anomalies, and radial ray defects are also evident.45 Since CDC45 has been shown to bind several additional proteins in the preIC, for example TOPBP148 and MCM10,49 mutations of these other components may in future be implicated in MGS or disorders exhibiting overlapping features.

A distinctive feature of MGS caused by CDC45 mutations is the frequent association with craniosynostosis. Only one previous MGS-affected subject, harboring mutations in ORC1, has been reported with craniosynostosis (P1 in Bicknell et al.20); therefore, it is likely that the presence of craniosynostosis in MGS-affected subjects is a strong predictor for CDC45 mutations. Craniosynostosis is also a feature of Baller-Gerold syndrome (MIM: 218600), another RECQL4 disorder,45 further implicating replication initiation in the etiology of premature cranial suture closure.

Disruption of the canonical function of CDC45 in replication initiation is consistent with the previously proposed models to explain the growth phenotype, which suggested that impaired replication in affected individuals disrupts cell division during periods of rapid proliferation in development, ultimately impairing organism growth and leading to a “hypocellular” dwarfism.20, 50 Partial loss-of-function mutations in CDC45, like those in preRC components, further indicate that strict regulation of replication is particularly required for the development of specific cartilaginous structures (ear, patella, trachea, or bronchial tree),51 but the exact mechanism remains elusive and future studies with model organisms will be required. Similarly, the frequent occurrence of craniosynostosis in this cohort, along with the established premature suture fusion seen in subjects with RECQL4 mutations, highlights the importance of normal replication initiation and progression to maintain correct proliferation-differentiation balance in the cranial sutures.52

In summary, we present genetic and functional evidence that mutations in CDC45 cause Meier-Gorlin syndrome with craniosynostosis. The identification of these mutations in a DNA replication protein functioning downstream to the previously identified MGS genes reinforces the premise that the growth and cartilaginous phenotypes of MGS, as well as the premature cranial suture fusion seen here, are due to replication dysfunction. This identification also suggests new candidate genes in which mutations might underlie this disorder or component phenotypes.

Acknowledgments

We thank the families and clinicians for their participation, the IGMM core sequencing service, staff at the High-Throughput Genomics facility at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics (Oxford) for Illumina sequencing, Tim Forshew and Francesco Marass for primer design, and Sue Butler, John Frankland, and Tim Rostron for help with cell culture and DNA sequencing. This work was supported by funding from the Medical Research Council (MRC) (A.P.J., L.S.-P., C.P.P., W.N.) and through the WIMM Strategic Alliance (G0902418 and MC_UU_12025), the European Research Council (ERC, 281847) (A.P.J.), the Lister Institute for Preventative Medicine (A.P.J.), Medical Research Scotland (L.S.B.), Royal Society of New Zealand Rutherford Discovery Fellowship (L.S.B.), the Department of Health, UK, Quality, Improvement, Development and Initiative Scheme (QIDIS) (A.O.M.W.), Newlife Foundation for Disabled Children (SG/14-15/10 to A.O.M.W.), National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre Programme (A.O.M.W.), and the Wellcome Trust (Project Grant 093329 to A.O.M.W. and S.R.F.T.; Investigator Award 102731 to A.O.M.W.).

Published: June 30, 2016

Footnotes

Supplemental Data include Supplementary Notes, Tables S1–S5, and Figure S1 and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.05.019.

Contributor Information

Wojciech Niedzwiedz, Email: wojciech.niedzwiedz@imm.ox.ac.uk.

Louise S. Bicknell, Email: louise.bicknell@otago.ac.nz.

Web Resources

1000 Genomes, http://www.1000genomes.org

ExAC Browser, http://exac.broadinstitute.org/

GoNL (Genomes of the Netherlands), http://www.nlgenome.nl/search/

NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP) Exome Variant Server, http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/

OMIM, http://www.omim.org/

PyMOL, http://www.pymol.org

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Bell S.P., Stillman B. ATP-dependent recognition of eukaryotic origins of DNA replication by a multiprotein complex. Nature. 1992;357:128–134. doi: 10.1038/357128a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanaka S., Diffley J.F. Interdependent nuclear accumulation of budding yeast Cdt1 and Mcm2-7 during G1 phase. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:198–207. doi: 10.1038/ncb757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanaka S., Araki H. Helicase activation and establishment of replication forks at chromosomal origins of replication. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013;5:a010371. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a010371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costa A., Renault L., Swuec P., Petojevic T., Pesavento J.J., Ilves I., MacLellan-Gibson K., Fleck R.A., Botchan M.R., Berger J.M. DNA binding polarity, dimerization, and ATPase ring remodeling in the CMG helicase of the eukaryotic replisome. eLife. 2014;3:e03273. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ilves I., Petojevic T., Pesavento J.J., Botchan M.R. Activation of the MCM2-7 helicase by association with Cdc45 and GINS proteins. Mol. Cell. 2010;37:247–258. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li N., Zhai Y., Zhang Y., Li W., Yang M., Lei J., Tye B.K., Gao N. Structure of the eukaryotic MCM complex at 3.8 Å. Nature. 2015;524:186–191. doi: 10.1038/nature14685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moyer S.E., Lewis P.W., Botchan M.R. Isolation of the Cdc45/Mcm2-7/GINS (CMG) complex, a candidate for the eukaryotic DNA replication fork helicase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:10236–10241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602400103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pacek M., Tutter A.V., Kubota Y., Takisawa H., Walter J.C. Localization of MCM2-7, Cdc45, and GINS to the site of DNA unwinding during eukaryotic DNA replication. Mol. Cell. 2006;21:581–587. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szambowska A., Tessmer I., Kursula P., Usskilat C., Prus P., Pospiech H., Grosse F. DNA binding properties of human Cdc45 suggest a function as molecular wedge for DNA unwinding. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:2308–2319. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hopwood B., Dalton S. Cdc45p assembles into a complex with Cdc46p/Mcm5p, is required for minichromosome maintenance, and is essential for chromosomal DNA replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:12309–12314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mimura S., Takisawa H. Xenopus Cdc45-dependent loading of DNA polymerase alpha onto chromatin under the control of S-phase Cdk. EMBO J. 1998;17:5699–5707. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyake S., Yamashita S. Identification of sna41 gene, which is the suppressor of nda4 mutation and is involved in DNA replication in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genes Cells. 1998;3:157–166. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1998.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshida K., Kuo F., George E.L., Sharpe A.H., Dutta A. Requirement of CDC45 for postimplantation mouse development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:4598–4603. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.14.4598-4603.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zou L., Mitchell J., Stillman B. CDC45, a novel yeast gene that functions with the origin recognition complex and Mcm proteins in initiation of DNA replication. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:553–563. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.2.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heller R.C., Kang S., Lam W.M., Chen S., Chan C.S., Bell S.P. Eukaryotic origin-dependent DNA replication in vitro reveals sequential action of DDK and S-CDK kinases. Cell. 2011;146:80–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.On K.F., Beuron F., Frith D., Snijders A.P., Morris E.P., Diffley J.F. Prereplicative complexes assembled in vitro support origin-dependent and independent DNA replication. EMBO J. 2014;33:605–620. doi: 10.1002/embj.201387369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yeeles J.T., Deegan T.D., Janska A., Early A., Diffley J.F. Regulated eukaryotic DNA replication origin firing with purified proteins. Nature. 2015;519:431–435. doi: 10.1038/nature14285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bongers E.M., Opitz J.M., Fryer A., Sarda P., Hennekam R.C., Hall B.D., Superneau D.W., Harbison M., Poss A., van Bokhoven H. Meier-Gorlin syndrome: report of eight additional cases and review. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2001;102:115–124. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bicknell L.S., Bongers E.M., Leitch A., Brown S., Schoots J., Harley M.E., Aftimos S., Al-Aama J.Y., Bober M., Brown P.A. Mutations in the pre-replication complex cause Meier-Gorlin syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:356–359. doi: 10.1038/ng.775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bicknell L.S., Walker S., Klingseisen A., Stiff T., Leitch A., Kerzendorfer C., Martin C.A., Yeyati P., Al Sanna N., Bober M. Mutations in ORC1, encoding the largest subunit of the origin recognition complex, cause microcephalic primordial dwarfism resembling Meier-Gorlin syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:350–355. doi: 10.1038/ng.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guernsey D.L., Matsuoka M., Jiang H., Evans S., Macgillivray C., Nightingale M., Perry S., Ferguson M., LeBlanc M., Paquette J. Mutations in origin recognition complex gene ORC4 cause Meier-Gorlin syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:360–364. doi: 10.1038/ng.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Munnik S.A., Hoefsloot E.H., Roukema J., Schoots J., Knoers N.V., Brunner H.G., Jackson A.P., Bongers E.M. Meier-Gorlin syndrome. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2015;10:114. doi: 10.1186/s13023-015-0322-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burrage L.C., Charng W.L., Eldomery M.K., Willer J.R., Davis E.E., Lugtenberg D., Zhu W., Leduc M.S., Akdemir Z.C., Azamian M. De novo GMNN mutations cause autosomal-dominant primordial dwarfism associated with Meier-Gorlin syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2015;97:904–913. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshida K., Oyaizu N., Dutta A., Inoue I. The destruction box of human Geminin is critical for proliferation and tumor growth in human colon cancer cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:58–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sievers F., Wilm A., Dineen D., Gibson T.J., Karplus K., Li W., Lopez R., McWilliam H., Remmert M., Söding J. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2011;7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan Z., Bai L., Sun J., Georgescu R., Liu J., O’Donnell M.E., Li H. Structure of the eukaryotic replicative CMG helicase suggests a pumpjack motion for translocation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016;23:217–224. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sali A., Blundell T.L. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;234:779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor J.C., Martin H.C., Lise S., Broxholme J., Cazier J.B., Rimmer A., Kanapin A., Lunter G., Fiddy S., Allan C. Factors influencing success of clinical genome sequencing across a broad spectrum of disorders. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:717–726. doi: 10.1038/ng.3304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robinson J.T., Thorvaldsdóttir H., Winckler W., Guttman M., Lander E.S., Getz G., Mesirov J.P. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abid Ali F., Renault L., Gannon J., Gahlon H.L., Kotecha A., Zhou J.C., Rueda D., Costa A. Cryo-EM structures of the eukaryotic replicative helicase bound to a translocation substrate. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10708. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krastanova I., Sannino V., Amenitsch H., Gileadi O., Pisani F.M., Onesti S. Structural and functional insights into the DNA replication factor Cdc45 reveal an evolutionary relationship to the DHH family of phosphoesterases. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:4121–4128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.285395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanchez-Pulido L., Ponting C.P. Cdc45: the missing RecJ ortholog in eukaryotes? Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1885–1888. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He Q., Wang F., Liu S., Zhu D., Cong H., Gao F., Li B., Wang H., Lin Z., Liao J., Gu L. Structural and biochemical insight into the mechanism of Rv2837c from Mycobacterium tuberculosis as a c-di-NMP phosphodiesterase. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:3668–3681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.699801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wakamatsu T., Kim K., Uemura Y., Nakagawa N., Kuramitsu S., Masui R. Role of RecJ-like protein with 5′-3′ exonuclease activity in oligo(deoxy)nucleotide degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:2807–2816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.161596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamagata A., Kakuta Y., Masui R., Fukuyama K. The crystal structure of exonuclease RecJ bound to Mn2+ ion suggests how its characteristic motifs are involved in exonuclease activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:5908–5912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092547099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kukimoto I., Igaki H., Kanda T. Human CDC45 protein binds to minichromosome maintenance 7 protein and the p70 subunit of DNA polymerase alpha. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999;265:936–943. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Desmet F.O., Hamroun D., Lalande M., Collod-Béroud G., Claustres M., Béroud C. Human Splicing Finder: an online bioinformatics tool to predict splicing signals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e67. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwartz S., Hall E., Ast G. SROOGLE: webserver for integrative, user-friendly visualization of splicing signals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W189–W192. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Delio M., Guo T., McDonald-McGinn D.M., Zackai E., Herman S., Kaminetzky M., Higgins A.M., Coleman K., Chow C., Jalbrzikowski M. Enhanced maternal origin of the 22q11.2 deletion in velocardiofacial and DiGeorge syndromes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;92:439–447. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Casey J.P., Nobbs M., McGettigan P., Lynch S., Ennis S. Recessive mutations in MCM4/PRKDC cause a novel syndrome involving a primary immunodeficiency and a disorder of DNA repair. J. Med. Genet. 2012;49:242–245. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-100803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gineau L., Cognet C., Kara N., Lach F.P., Dunne J., Veturi U., Picard C., Trouillet C., Eidenschenk C., Aoufouchi S. Partial MCM4 deficiency in patients with growth retardation, adrenal insufficiency, and natural killer cell deficiency. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:821–832. doi: 10.1172/JCI61014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hughes C.R., Guasti L., Meimaridou E., Chuang C.H., Schimenti J.C., King P.J., Costigan C., Clark A.J., Metherell L.A. MCM4 mutation causes adrenal failure, short stature, and natural killer cell deficiency in humans. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:814–820. doi: 10.1172/JCI60224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Im J.S., Ki S.H., Farina A., Jung D.S., Hurwitz J., Lee J.K. Assembly of the Cdc45-Mcm2-7-GINS complex in human cells requires the Ctf4/And-1, RecQL4, and Mcm10 proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:15628–15632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908039106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sangrithi M.N., Bernal J.A., Madine M., Philpott A., Lee J., Dunphy W.G., Venkitaraman A.R. Initiation of DNA replication requires the RECQL4 protein mutated in Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Cell. 2005;121:887–898. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Siitonen H.A., Sotkasiira J., Biervliet M., Benmansour A., Capri Y., Cormier-Daire V., Crandall B., Hannula-Jouppi K., Hennekam R., Herzog D. The mutation spectrum in RECQL4 diseases. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;17:151–158. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hossain M., Stillman B. Meier-Gorlin syndrome mutations disrupt an Orc1 CDK inhibitory domain and cause centrosome reduplication. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1797–1810. doi: 10.1101/gad.197178.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stiff T., Alagoz M., Alcantara D., Outwin E., Brunner H.G., Bongers E.M., O’Driscoll M., Jeggo P.A. Deficiency in origin licensing proteins impairs cilia formation: implications for the aetiology of Meier-Gorlin syndrome. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003360. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schmidt U., Wollmann Y., Franke C., Grosse F., Saluz H.P., Hänel F. Characterization of the interaction between the human DNA topoisomerase IIbeta-binding protein 1 (TopBP1) and the cell division cycle 45 (Cdc45) protein. Biochem. J. 2008;409:169–177. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Di Perna R., Aria V., De Falco M., Sannino V., Okorokov A.L., Pisani F.M., De Felice M. The physical interaction of Mcm10 with Cdc45 modulates their DNA-binding properties. Biochem. J. 2013;454:333–343. doi: 10.1042/BJ20130059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Klingseisen A., Jackson A.P. Mechanisms and pathways of growth failure in primordial dwarfism. Genes Dev. 2011;25:2011–2024. doi: 10.1101/gad.169037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Munnik S.A., Bicknell L.S., Aftimos S., Al-Aama J.Y., van Bever Y., Bober M.B., Clayton-Smith J., Edrees A.Y., Feingold M., Fryer A. Meier-Gorlin syndrome genotype-phenotype studies: 35 individuals with pre-replication complex gene mutations and 10 without molecular diagnosis. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;20:598–606. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Twigg S.R.F., Wilkie A.O.M. A genetic-pathophysiological framework for craniosynostosis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2015;97:359–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Newell N.E. Mapping side chain interactions at protein helix termini. BMC Bioinformatics. 2015;16:231. doi: 10.1186/s12859-015-0671-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berti M., Vindigni A. Replication stress: getting back on track. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016;23:103–109. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aravind L., Koonin E.V. The HD domain defines a new superfamily of metal-dependent phosphohydrolases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1998;23:469–472. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01293-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cole T.J., Freeman J.V., Preece M.A. British 1990 growth reference centiles for weight, height, body mass index and head circumference fitted by maximum penalized likelihood. Stat. Med. 1998;17:407–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fenton T.R., Kim J.H. A systematic review and meta-analysis to revise the Fenton growth chart for preterm infants. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.