Abstract

Aspergillus species cause a wide spectrum of clinical infections. Although Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus flavus remain the most commonly isolated species in aspergillosis, in the last decade, rare and cryptic Aspergillus species have emerged in diverse clinical settings. The present study analyzed the distribution and in vitro antifungal susceptibility profiles of rare Aspergillus species in clinical samples from patients with suspected aspergillosis in 8 medical centers in India. Further, a matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry in-house database was developed to identify these clinically relevant Aspergillus species. β-Tubulin and calmodulin gene sequencing identified 45 rare Aspergillus isolates to the species level, except for a solitary isolate. They included 23 less common Aspergillus species belonging to 12 sections, mainly in Circumdati, Nidulantes, Flavi, Terrei, Versicolores, Aspergillus, and Nigri. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) identified only 8 (38%) of the 23 rare Aspergillus isolates to the species level. Following the creation of an in-house database with the remaining 14 species not available in the Bruker database, the MALDI-TOF MS identification rate increased to 95%. Overall, high MICs of ≥2 μg/ml were noted for amphotericin B in 29% of the rare Aspergillus species, followed by voriconazole in 20% and isavuconazole in 7%, whereas MICs of >0.5 μg/ml for posaconazole were observed in 15% of the isolates. Regarding the clinical diagnoses in 45 patients with positive rare Aspergillus species cultures, 19 (42%) were regarded to represent colonization. In the remaining 26 patients, rare Aspergillus species were the etiologic agent of invasive, chronic, and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, allergic fungal rhinosinusitis, keratitis, and mycetoma.

INTRODUCTION

Aspergillus species cause a wide spectrum of clinical infections, ranging from allergic to chronic and life-threatening invasive diseases (1). The most common pathogenic species implicated in aspergillosis are A. fumigatus, A. flavus, A. terreus, and rarely, A. niger. However, in the last decade, several reports have pointed to a shift in the etiology of aspergillosis and highlighted the emergence of cryptic and rare Aspergillus species in various clinical settings in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent hosts (2–4). This shift is mainly linked to the application of multilocus DNA sequence analysis in various studies, leading to the description of previously unknown “cryptic” Aspergillus species (5–7). In two population-based prospective studies in the United States and Spain, the prevalences of cryptic Aspergillus species detected in clinical specimens were found to be 10% and 12%, respectively (8, 9). The molecular analysis of aspergilli collected from the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network (TRANSNET) from 24 transplant centers throughout the United States revealed that 10% of the isolates associated with invasive aspergillosis (IA) in transplant recipients were cryptic Aspergillus species (8). Similarly, the population-based FILPOP survey to investigate the epidemiology and antifungal resistance in Spanish clinical strains of filamentous fungi from deep-tissue samples, blood cultures, and respiratory samples reported that 12% of the isolates were cryptic Aspergillus species (9). The most notable findings in both studies were that the cryptic species had high in vitro MICs to multiple antifungal drugs, including azoles and amphotericin B (9, 10). Both azoles and amphotericin B antifungals are agents of choice to treat Aspergillus infections; thus, high MICs to these agents pose a serious therapeutic challenge. Therefore, correct and early identification and development of antifungal susceptibility profiles are two important goals for managing patients with aspergillosis. In the present study, we analyzed the occurrence of rare Aspergillus species obtained from a referral chest hospital in Delhi, India, by molecular methods and determined their clinical significance in various patient settings. As matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) identification has been reported to yield rapid identification of filamentous fungi with an accuracy similar to that of DNA sequence-based methods, herein, we also validated MALDI-TOF MS technology to differentiate rare Aspergillus species. Further antifungal susceptibility profiles of the isolates were determined for 8 antifungals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical specimens and fungal isolates.

A total of 8,239 clinical samples collected from 8 hospitals, including 6 in Delhi, North India, and two in South India, were processed for fungal culture during 2011 to 2014. The specimens were processed for direct microscopy by KOH/Blankophor staining and culture on Sabouraud glucose agar (SGA) containing chloramphenicol (50 mg/liter) and gentamicin (40 mg/liter) and incubated at 28°C. Overall, during a 3-year study period, 1,534 isolates of Aspergillus species were obtained from 2,225 (27%) culture-positive clinical specimens.

Morphological examination and thermotolerance testing.

Preliminary phenotypic identification of the Aspergillus isolates was done by examination of colony color and macromorphology on Czapek Dox (CZ) agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI, USA), followed by incubation at 28°C for 7 days. Slide cultures of the Aspergillus spp. on CZ agar were observed microscopically with lactophenol cotton blue mounts. To study the thermotolerance, isolates were grown on SGA plates and incubated at 37°C, 40°C, 45°C, and 50°C.

Molecular identification and phylogenetic analysis.

The isolates were grown in Sabouraud glucose broth (SGB) at 37°C for 36 to 48 h in a tube rotator (Labnet International, USA) for genomic DNA extraction (11). Briefly, DNA was extracted by crushing the pure hyphal growth of isolates in the presence of liquid nitrogen and extraction buffer (0.2 M Tris-HCl, 10 mM EDTA, 0.5 M NaCl, 1% SDS) in a mortar and pestle, followed by the phenol, chloroform, and isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) extraction and ethanol precipitation. The extracted DNA was subjected to amplification of the partial calmodulin (cmd) gene using primers cmd5 (5′-CCGAGTACAAGGAGGCCTTC3′) and cmd6 (5′-CCGATAGAGGTCATAACGTGG-3′) (12), and the fragments of the β-tubulin gene using the Bt1a (5′TTCCCCCGTCTCCACTTCTTCATG 3′), Bt1b (5′GACGAGATCGTTCATGTTGAACTC3′), Bt2a (5′-GGTAACCAAATCGGTGCTGCTTTC-3′), and Bt2b (5′-ACCCTCAGTGTAGTGACCCTTGGC-3′) primers (13). DNA sequencing was performed using the respective primers for PCR at 0.5 μM concentration. All sequencing reactions were carried out in a 10-μl reaction volume using the BigDye Terminator kit version 3.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's recommendations, and analyzed on an ABI 3130XL genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems). cmd and β-tubulin gene sequences were subjected to BLAST searches at GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/Blast.cgi). Sequence-based species identification was defined by ≥99% sequence similarity with ≥95% query coverage. Further, a neighbor-joining (NJ) tree based on aligned cmd gene sequences with 2,000 bootstrap replications was constructed using MEGA version 6 (14). The sequences of the type/reference strains of Aspergillus species were retrieved from GenBank and included for the phylogenetic analysis.

MALDI-TOF MS.

MALDI-TOF MS (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) Biotyper OC version 3.1 was used for identification and in-house database creation of Aspergillus species. The ethanol-formic acid extraction method using 16-h-old Aspergillus cultures incubated at 37°C in SGB in a tube rotator was used for analysis. Briefly, 1 ml of culture was centrifuged at 20,800 × g for 2 min, and the pellet was washed twice with 1 ml of deionized water. The pellet was suspended in 300 μl of deionized water and 900 μl of absolute ethanol and centrifuged. The pellet was air-dried and dissolved in 50 μl of formic acid (70% [vol/vol]) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and an equal volume of acetonitrile (Sigma-Aldrich) was added and centrifuged. One microliter of the supernatant was applied on the target plate and air-dried at room temperature. The air-dried spot was overlaid with 1 μl of saturated α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid dissolved in 50% acetonitrile and 2.5% trifluoroacetic acid matrix solution (HCCA; Bruker Daltonics). The spectra were recorded in the linear positive mode at a laser frequency of 20 Hz within a mass range from 2,000 to 20,000 Da. Two hundred forty laser shots in six-shot steps from different positions of the target spot were collected and analyzed for each spectrum generated. The reference Escherichia coli ATCC 8739 test standard (Bruker Daltonics) was used to calibrate the mass spectra in each analysis. The spectra were analyzed using the flexControl 3.1 (Bruker Daltonics) and MALDI Biotyper OC version 3.1 softwares.

In-house database creation.

The spectra of Aspergillus species identified in the present study, which were not available in the current Bruker database (updated in January 2016), were included for in-house database creation. Each isolate was grown at 37°C in SGB for 16 h and processed in triplicate on the same day. Eight spots per replicate were used for main spectrum (MSP) creation. The raw spectra of at least 20 spots of each isolate were generated, stored, and downloaded in the Biotyper 3.0 software. The spectra were processed in five steps, including mass adjustment with spectra compressing by a factor of 1 for m/z between 9,700 and 10,000, smoothing using a Savitzky-Golay algorithm with a 5-Da frame size, baseline subtraction, normalization using a maximum-norm algorithm, and peak picking using a local maximum algorithm. This procedure generated a list of the most significant peaks to create MSPs with the average peak mass, average peak intensity, and frequency information. Further, the MSP of each species was also validated by at least 2 to 4 strains of the same species available in the Vallabhbhai Patel Chest Institute (VPCI) culture collection, which yielded correct identification with a score of ≥2.

AFST.

Antifungal susceptibility testing (AFST) was done using broth microdilution CLSI M38-A2 guidelines (15). The drugs tested were itraconazole (ITC; Lee Pharma, Hyderabad, India), voriconazole (VRC; Pfizer Central Research, Sandwich, Kent, United Kingdom), isavuconazole (ISA; Basilea Pharmaceutica International AG, Basel, Switzerland), posaconazole (POS; Merck, Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA), amphotericin B (AMB; Sigma-Aldrich, Germany), caspofungin (CFG; Merck), micafungin (MFG; Astellas Toyama Co. Ltd., Japan), and anidulafungin (AFG; Pfizer). Drug-free and mold-free controls were included, and microtiter plates were incubated at 35°C. Minimum effective concentration (MEC) readings were taken visually after 24 h for echinocandins and MICs at 48 h for azoles and AMB. A set of quality control strains of Candida krusei ATCC 6258 and Candida parapsilosis ATCC 22019 and reference strains of A. fumigatus ATCC 204305 and A. flavus ATCC 204304 were included for every batch of isolates tested each day. MIC endpoints for all the drugs except echinocandins were defined as the lowest concentration that produced complete inhibition of growth. Minimum effective concentrations of echinocandins were defined as the lowest drug concentration that allowed the growth of small, rounded, and degenerated hyphae. CLSI has established epidemiologic cutoff values (ECVs) for six Aspergillus species, namely A. fumigatus, A. flavus, A. niger, A. terreus, A. nidulans, and A. versicolor for ITC, VRC, POS, and ISA (16, 17). However, breakpoints or ECVs for rare Aspergillus species identified in this study are not available. Therefore, MICs above the ECV of A. fumigatus for azoles, i.e., ITC at >1 μg/ml, VRC at >1 μg/ml, POS at >0.5 μg/ml, and ISA at >1 μg/ml, were used for comparing MIC data of the rare Aspergillus species analyzed in the present study. For AMB, an MIC above the CLSI ECV of ≥2 μg/ml was considered resistant (18).

Clinical details.

The records of 88 patients whose clinical specimens yielded 90 Aspergillus isolates in culture were reviewed for the clinical disease entity attributable to Aspergillus, which included sino-bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (invasive pulmonary aspergillosis [IPA], chronic pulmonary aspergillosis [CPA], allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis [ABPA], and allergic fungal rhinosinusitis [AFRS]), disseminated aspergillosis, cerebral aspergillosis, keratitis, subcutaneous infections, or colonization of the respiratory tract. IA was defined as probable or definite according to the criteria of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) (19). CPA was diagnosed as per European Respiratory Society guidelines (20). ABPA was diagnosed by a combination of clinical, mycoserologic, and radiological features, as proposed by Rosenberg et al. (21). AFRS was diagnosed using the deShazo and Swain criteria (22), which included type 1 hypersensitivity, nasal polyposis, characteristic computed tomography findings, eosinophilic mucin without invasion, and a positive fungal stain of sinus contents. Regarding subcutaneous infections, diagnosis was based on histopathology of biopsy specimens.

Accession number(s).

The nucleotide sequences obtained in the present study have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers KX455724 to KX455810, KX357795, KM386818, and KM386817 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Clinical details of rare Aspergillus species (n = 45)

| Section (no. of isolates) | Species identified (n)a | GenBank accession numbers |

Diagnosis/es (organism, n)b | Specimen(s) (n)c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calmodulin | β-tubulin | ||||

| Circumdati (6) | A. pallidofulvus* (3), A. melleus* (2), A. ochraceus (1) | KX455768 to KX455773 | KX455724 to KX455729 | IPA (A. pallidofulvus, 1; A. ochraceus, 1), ABPA (A. melleus, 1), disseminated aspergillosis (A. pallidofulvus, 1), colonizer (2) | BAL fluid (3), FNAB (1), sputum (1), blood (1) |

| Nidulantes (6) | A. nidulans (E. nidulans) (3), A. nidulans var. dentatus* (Emericella dentata) (1), A. corrugatus* (E. corrugata) (1), A. unguis (E. unguis) (1) | KX455774 to KX455779 | KX455730 to KX455735 | Mycetoma (A. nidulans, 1), colonizer (5) | Subcutaneous tissue (1), sputum (5) |

| Flavi (6) | A. tamarii (4), A. oryzae (2) | KX455780 to KX455785 | KX455736 to KX455741 | IPA (A. tamarii, 1), mycetoma (A. tamarii, 1), keratitis (A. tamarii, 1; A. oryzae, 2), colonizer (1) | BAL fluid (1), sputum (1), subcutaneous tissue/pus/granule (1), corneal scraping (3) |

| Terrei (5) | A. niveus* (3), A. hortai* (2) | KX455786 to KX455788, KM386818, KM386817 | KX455742 to KX455746 | IPA (A. niveus, 2), CPA (A. hortai, 1), aspergilloma (A. hortai, 1), colonizer (1) | BAL fluid (2), FNAB (1), sputum (2) |

| Versicolores (5) | A. sydowii (4), A. versicolor (1) | KX455789 to KX455793 | KX455747 to KX455751 | IPA (A. sydowii, 1), AFRS (A. sydowii, 1), keratitis (A. sydowii, 2; A. versicolor, 1) | Sputum (2), corneal scraping (3), sinus aspirate/nasal wash (1) |

| Aspergillus (5) | A. montevidensis* (3), A. chevalieri* (E. chevalieri) (1), A. amstelodami (E. amstelodami) (1) | KX455794 to KX455798 | KX455752 to KX455756 | IPA (A. montevidensis, 1), cerebral aspergillosis (A. chevalieri, 1), colonizer (3) | CSF/drained brain abscess (1), sputum (2), BAL fluid (2) |

| Nigri (4) | A. brunneoviolaceus* (A. fijiensis) (2), A. aculeatus* (2) | KX455799 to KX455802 | KX455757 to KX455760 | IPA (A. brunneoviolaceus, 1), colonizer (3) | Sputum (2), BAL fluid (2) |

| Fumigati (3) | A. fischeri (N. fischeri) (2) | KX455803, KX455804 | KX455761, KX455762 | IPA (2) | Endotracheal aspirate (1), BAL fluid (1) |

| Candidi (2) | A. tritici* (2) | KX455805, KX455806 | KX455763, KX455764 | Colonizer (2) | Sputum (1), BAL fluid (1) |

| Clavati (1) | A. clavatus (1) | KX455807 | KX455765 | Colonizer (1) | Sputum (1) |

| Flavipedes (1) | A. flavipes* (1) | KX455808 | KX455766 | Cerebral aspergillosis (1) | CSF(1) |

| Usti (1) | A. egyptiacus* (1) | KX455809 | KX455767 | Colonizer (1) | Sputum (1) |

| Unidentified species (1) | Aspergillus sp.* (1) | KX455810 | KX357795 | Keratitis (1) | Corneal scraping (1) |

Synonyms are denoted in parentheses. Asterisks denote that an in-house MSP database was created for MALDI-TOF MS.

IPA, invasive pulmonary aspergillosis; ABPA, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis; CPA, chronic pulmonary aspergillosis; AFRS, allergic fungal rhinosinusitis.

BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; FNAB, fine needle aspirate biopsy of lung; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

RESULTS

Aspergillus isolates and clinical specimens.

Of the 1,534 isolates of Aspergillus, 44.2% (n = 679) were A. flavus species complex, 32% (n = 492) were A. fumigatus species complex, 7.2% (n = 111) were A. terreus species complex, and 16.6% (n = 252) were other Aspergillus species based on phenotypic and morphological examination. Among the other Aspergillus species, 90 random isolates were included in this study. They originated from clinical specimens from 88 patients that included bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid/bronchial aspirates (n = 34), sputa (n = 20), endotracheal aspirates (n = 9), corneal scrapings (n = 11), lung biopsy specimens (n = 6), nasal curettages/postoperative debrided tissues (n = 5), subcutaneous tissues (n = 2), cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (n = 2), and blood (n = 1).

β-Tubulin and calmodulin gene sequencing.

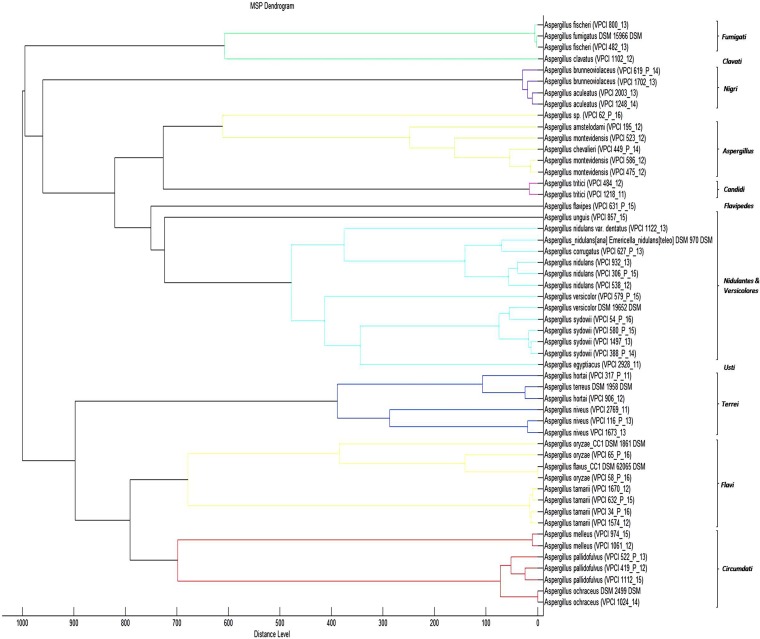

Table 1 lists species-level identification of all the isolates in the present study by cmd and β-tubulin gene sequencing, which yielded 99 to 100% identity by BLAST searches, except for a solitary isolate of an Aspergillus species, which yielded 91% and 95% identity with the cmd and β-tubulin genes, respectively. Of the 90 isolates, 50% were confirmed as A. flavus (n = 24), A. terreus (n = 12), and A. fumigatus (n = 9). It is pertinent to emphasize here that most of the sensu stricto isolates of A. flavus and A. fumigatus were atypical on macromorphological examination and showed white nonsporulating colonies, whereas those of A. terreus were atypical with respect to delayed growth on CZ agar and therefore misidentified phenotypically. The remaining 45 (50%) isolates were rare Aspergillus species, which were defined as species other than commonly isolated A. fumigatus, A. flavus, and A. terreus isolates. The rare 45 Aspergillus isolates represented 23 Aspergillus species, belonging to 12 sections. All of the rare Aspergillus species grew at 37°C. Further, A. nidulans (Emericella nidulans), A. nidulans var. dentatus (Emericella dentata), A. chevalieri (Eurotium chevalieri), and A. amstelodami (Eurotium amstelodami) grew at 45°C, whereas A. tamarii and A. oryzae grew at 40°C. Aspergillus corrugatus (Emericella corrugata) and Aspergillus fischeri (Neosartorya fischeri) grew at 50°C. Further, typical morphological characteristics of the respective Aspergillus species were noted. The cmd phylogenetic NJ tree (Fig. 1) of rare Aspergillus isolates (n = 45) yielded section-wise distinct clades representing 12 Aspergillus sections, along with the reference/type strains (n = 30) retrieved from GenBank.

FIG 1.

Phylogenetic tree based on partial cmd sequences using neighbor-joining analysis with 2,000 bootstrap replications using MEGA version 6 of rare Aspergillus species. Shown are Indian strains (n = 45 for VPCI numbers) along with type/reference strains (n = 30) sequences retrieved from GenBank for the analysis. Bootstrap values are shown above the branches.

MALDI-TOF MS.

The current updated Bruker Biotyper OC version 3.1 has MSPs of 21 species in the genus Aspergillus belonging to 12 sections. Of the rare Aspergillus spp. identified to the species level in the present study (22 of 23), only eight species were present in the database, thus identifying 38% of rare aspergilli studied. However, MALDI-TOF identified all of the 45 atypical A. fumigatus, A. flavus, and A. terreus isolates to the species level with scores of ≥2. Further, 5 Aspergillus species (not available in the database) were misidentified, which included A. hortai and A. niveus, both in section Terrei misidentified as A. terreus; A. tritici misidentified as A. candidus (section Candidi); and A. fischeri misidentified as A. fumigatus, with a score of ≥2. Also, Aspergillus oryzae, which is cautioned by the Bruker database as being misidentified as A. flavus, was also misidentified.

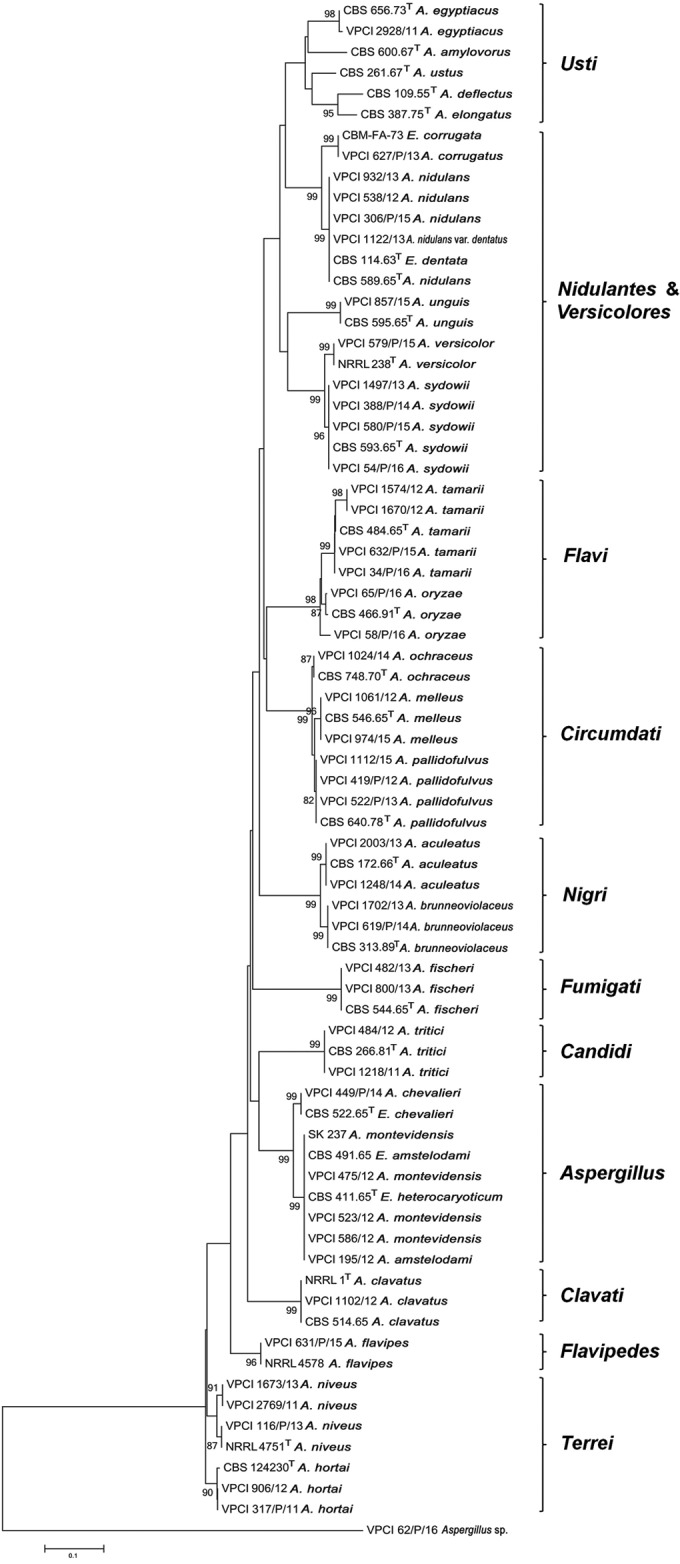

However, inclusion of the MSPs of 14 rare Aspergillus species identified in this study but not available in the database correctly identified all the species with a score of ≥2. The MSP dendrogram (Fig. 2) of all the species identified in this study also showed section-wise clustering of isolates, which was in concordance with the NJ phylogenetic tree based on cmd sequences (Fig. 1). However, in contrast to the NJ tree that clearly differentiated A. brunneoviolaceus (A. fijiensis) and A. aculeatus in the section Nigri, the MSP dendrogram clustered the two species together.

FIG 2.

Score-oriented dendrogram of the main spectra of an in-house database of Aspergillus species by using average linkages clustering.

Antifungal susceptibility testing.

The results of in vitro antifungal susceptibility profiles of rare Aspergillus (n = 45) isolates are summarized in Table 2. Among the azoles, POS was the most potent drug against all Aspergillus species (MIC range, 0.015 to 1 μg/ml) except two isolates of A. niveus and a single isolate each of A. pallidofulvus, A. sydowii, and A. fischeri, which had high MICs of >2 μg/ml. Overall, high MICs of ≥2 μg/ml were observed for AMB in 29% of the isolates (n = 13), followed by VRC in 20% of the isolates and ISA in 7% of the isolates. Also, 15% of the isolates had POS MICs of >0.5 μg/ml (range, 0.5 to 8 μg/ml) (Table 2). Low susceptibility to more than one antifungal drug was also observed in this collection of rare Aspergillus species. Notably, coexisting high AMB and VRC MICs were seen in 7 (15%) isolates, and 3 of these isolates also had coexisting high MICs against two or more azoles. The high AMB MICs were observed for species in the sections Circumdati and Terrei. Also, two species in the section Nidulantes, namely A. nidulans (n = 1) and A. unguis (Emericella unguis) (n = 1), exhibited high MICs for AMB (8 μg/ml and 16 μg/ml, respectively). Additionally, a single isolate of A. pallidofulvus in the section Circumdati showed high MICs (range, 4 to 16 μg/ml) to all azoles. Also, A. unguis exhibited high MICs for VRC (16 μg/ml) and ISA (4 μg/ml). In addition, strain-to-strain MIC variation was observed in species of A. pallidofulvus, A. melleus, and A. brunneoviolaceus against AMB and azoles. In contrast, all isolates had low MICs for CFG (MIC range, 0.015 to 0.5 μg/ml), MFG, and AFG (MIC range, 0.015 to 0.25 μg/ml) (Table 2). Among the sensu stricto species A. fumigatus, A. flavus, and A. terreus, all isolates were susceptible to antifungals, except a solitary A. fumigatus isolate, which had high MICs to ITC (16 μg/ml), VRC (8 μg/ml), and ISA (4 μg/ml). No mutations in the cyp51A gene were observed for this isolate.

TABLE 2.

In vitro antifungal susceptibility profile of rare Aspergillus species isolates (n = 45) against azoles, echinocandins, and amphotericin B

| Section (n) | Species (no. of isolates) | Druga | MIC/MEC (μg/ml)b |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | GM | 0.015 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | |||

| Circumdati (6) | A. pallidofulvus (3) | AMB | 1–16 | 5.03 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| VRC | 1–16 | 3.17 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| ISA | 0.5–8 | 1.25 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||

| POS | 0.25–4 | 0.63 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||

| ITC | 0.5–16 | 1.58 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||

| CAS | 0.25–0.5 | 0.40 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||

| MFG | 0.015 | 0.015 | 3 | ||||||||||||

| AFG | 0.015 | 0.015 | 3 | ||||||||||||

| A. melleus (2) | AMB | 1–16 | 4 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| VRC | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| ISA | 0.125–1 | 0.35 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| POS | 0.015–0.125 | 0.04 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| ITC | 0.5–1 | 0.71 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| CAS | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| MFG | 0.03–0.125 | 0.06 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| AFG | 0.03 | 0.03 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| A. ochraceus (1) | AMB | 16 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| VRC | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| ISA | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| POS | 0.25 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| ITC | 0.5 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| CAS | 0.5 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| MFG | 0.015 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| AFG | 0.015 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Nidulantes (6) | A. nidulans (E. nidulans) (3), A. nidulans var. dentatus (E. dentata) (1) | AMB | 0.03–8 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||

| VRC | 0.125–0.25 | 0.18 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||

| ISA | 0.06–0.25 | 0.08 | 3 | 1 | |||||||||||

| POS | 0.015–0.25 | 0.03 | 3 | 1 | |||||||||||

| ITC | 0.03–0.125 | 0.06 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||||

| CAS | 0.125–0.25 | 0.15 | 3 | 1 | |||||||||||

| MFG | 0.015–0.03 | 0.02 | 3 | 1 | |||||||||||

| AFG | 0.015–0.06 | 0.02 | 3 | 1 | |||||||||||

| A. corrugatus (E. corrugata) (1) | AMB | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| VRC | 0.5 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| ISA | 0.5 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| POS | 0.125 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| ITC | 0.25 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| CAS | 0.25 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| MFG | 0.015 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| AFG | 0.015 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| A. unguis (E. unguis) (1) | AMB | 16 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| VRC | 16 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| ISA | 4 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| POS | 0.25 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| ITC | 0.5 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| CAS | 0.06 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| MFG | 0.015 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| AFG | 0.015 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Flavi (6) | A. tamarii (4) | AMB | 0.03–1 | 0.1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||

| VRC | 0.5–1 | 0.6 | 3 | 1 | |||||||||||

| ISA | 0.06–0.25 | 0.17 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||||

| POS | 0.015–1 | 0.07 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| ITC | 0.03–0.125 | 0.06 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||||

| CAS | 0.06–0.25 | 0.15 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||

| MFG | 0.015–0.06 | 0.02 | 3 | 1 | |||||||||||

| AFG | 0.015 | 0.015 | 4 | ||||||||||||

| A. oryzae (2) | AMB | 0.25–1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| VRC | 0.5–1 | 0.7 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| ISA | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| POS | 0.03–0.06 | 0.04 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| ITC | 0.125 | 0.125 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| CAS | 0.06–0.125 | 0.09 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| MFG | 0.015 | 0.015 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| AFG | 0.015 | 0.015 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Terrei (5) | A. niveus (3) | AMB | 0.125–16 | 1.6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| VRC | 2–16 | 5.03 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| ISA | 1–8 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||

| POS | 0.06–8 | 1.24 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| ITC | 0.25–16 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||

| CAS | 0.06–0.125 | 0.08 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||

| MFG | 0.015 | 0.015 | 3 | ||||||||||||

| AFG | 0.015–0.06 | 0.02 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||

| A. hortai (2) | AMB | 4–16 | 8 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| VRC | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| ISA | 0.25–0.5 | 0.35 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| POS | 0.06–0.25 | 0.12 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| ITC | 0.25–0.5 | 0.35 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| CAS | 0.015–0.06 | 0.03 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| MFG | 0.015 | 0.015 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| AFG | 0.015 | 0.015 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Versicolores (5) | A. sydowii (4) | AMB | 1–16 | 2.82 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||

| VRC | 0.5–2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||

| ISA | 0.06–1 | 0.41 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||

| POS | 0.015–2 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| ITC | 0.03–1 | 0.35 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||

| CAS | 0.06–0.125 | 0.10 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||||

| MFG | 0.015–0.25 | 0.03 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| AFG | 0.015–0.25 | 0.03 | 3 | 1 | |||||||||||

| A. versicolor (1) | AMB | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| VRC | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| ISA | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| POS | 0.125 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| ITC | 0.25 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| CAS | 0.25 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| MFG | 0.015 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| AFG | 0.015 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Aspergillus (5) | A. montevidensis (3) | AMB | 0.06–0.25 | 0.15 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||

| VRC | 0.125–1 | 0.31 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| ISA | 0.015–0.25 | 0.1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||

| POS | 0.015–0.06 | 0.04 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||

| ITC | 0.06–1 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| CAS | 0.06–0.125 | 0.08 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||

| MFG | 0.015 | 0.015 | 3 | ||||||||||||

| AFG | 0.015 | 0.015 | 3 | ||||||||||||

| A. chevalieri (E. chevalieri) (1) | AMB | 0.03 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| VRC | 0.25 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| ISA | 0.125 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| POS | 0.015 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| ITC | 0.03 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| CAS | 0.125 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| MFG | 0.03 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| AFG | 0.015 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| A. amstelodami (E. amstelodami) (1) | AMB | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| VRC | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| ISA | 0.5 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| POS | 0.015 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| ITC | 0.25 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| CAS | 0.25 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| MFG | 0.015 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| AFG | 0.015 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Nigri (4) | A. aculeatus (2) | AMB | 0.03–0.5 | 0.12 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| VRC | 0.125–0.5 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| ISA | 0.06–0.5 | 0.17 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| POS | 0.06–0.125 | 0.09 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| ITC | 0.125–0.25 | 0.18 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| CAS | 0.125–0.25 | 0.18 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| MFG | 0.015 | 0.015 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| AFG | 0.015 | 0.015 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| A. brunneoviolaceus (A. fijiensis) (2) | AMB | 0.06–0.125 | 0.09 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| VRC | 0.25–0.5 | 0.35 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| ISA | 0.015–0.06 | 0.03 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| POS | 0.015–0.5 | 0.09 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| ITC | 0.03 | 0.03 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| CAS | 0.06 | 0.06 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| MFG | 0.015 | 0.015 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| AFG | 0.015 | 0.015 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Fumigati (2) | A. fischeri (N. fischeri) (2) | AMB | 0.125–0.25 | 0.18 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| VRC | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| ISA | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| POS | 1–2 | 1.41 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| ITC | 0.5–1 | 0.07 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| CAS | 0.03–0.125 | 0.06 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| MFG | 0.015 | 0.015 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| AFG | 0.015 | 0.015 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Candidi (2) | A. tritici (2) | AMB | 0.125–0.5 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| VRC | 0.03 | 0.03 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| ISA | 0.015 | 0.015 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| POS | 0.015 | 0.015 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| ITC | 0.03 | 0.03 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| CAS | 0.06 | 0.06 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| MFG | 0.015 | 0.015 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| AFG | 0.015 | 0.015 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Clavati (1) | A. clavatus (1) | AMB | 0.125 | 1 | |||||||||||

| VRC | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| ISA | 0.25 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| POS | 0.125 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| ITC | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| CAS | 0.5 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| MFG | 0.125 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| AFG | 0.5 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Flavipedes (1) | A. flavipes (1) | AMB | 0.125 | 1 | |||||||||||

| VRC | 0.125 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| ISA | 0.125 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| POS | 0.25 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| ITC | 0.125 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| CAS | 0.125 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| MFG | 0.06 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| AFG | 0.015 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Usti (1) | A. egyptiacus (1) | AMB | 0.25 | 1 | |||||||||||

| VRC | 0.125 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| ISA | 0.5 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| POS | 0.015 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| ITC | 0.03 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| CAS | 0.25 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| MFG | 0.125 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| AFG | 0.06 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Other species (1) | Aspergillus sp. (1) | AMB | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| VRC | 0.125 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| ISA | 0.125 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| POS | 0.06 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| ITC | 0.06 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| CAS | 0.125 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| MFG | 0.015 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| AFG | 0.015 | 1 | |||||||||||||

AMB, amphotericin B; VRC, voriconazole; ISA, isavuconazole; POS, posaconazole; ITC, itraconazole; CAS, caspofungin; MFG, micafungin; AFG, anidulafungin.

MIC taken for azoles and AMB; MEC, minimum effective concentration taken for echinocandins; GM, geometric mean.

Clinical summary.

Overall, Aspergillus species were implicated in the etiology of the disease in 48 patients, whereas they were colonizing the respiratory tract in 42 (46.6%) cases with chronic respiratory disorders. Regarding the clinical entities diagnosed in 45 patients with positive rare Aspergillus species cultures, 19 (42%) patients were colonized (Table 1). In the remaining 26 patients, rare Aspergillus species were the etiologic agent of a wide spectrum of clinical diseases. Among these, the two largest groups of patients were those with IA (n = 13) and keratitis (n = 7). The other clinical entities were CPA/aspergilloma, ABPA, AFRS, and mycetoma of hand and foot. Among IA patients, 10 were diagnosed cases of IPA, two with cerebral aspergillosis and one case of disseminated aspergillosis. The most common underlying condition in IPA patients was chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in six cases and uncontrolled diabetes mellitus type II with ketoacidosis in two patients, and the remaining two patients had congenital lung cyst and acute myeloid leukemia each. Notably, the majority of IA, allergic, and chronic aspergillosis patients had no history of antifungal usage prior to the diagnosis. However, three cases that included CPA and ABPA patients were on VRC 400-mg therapy for 4 to 6 months.

DISCUSSION

The present study reports a broad species range and clinical spectrum of rare Aspergillus species in invasive and chronic aspergillosis, keratitis, and subcutaneous infections in 8 hospitals in India. This is the first comprehensive study from India characterizing a large number of various Aspergillus species by sequencing and MALDI-TOF MS. An updated species list of the genus Aspergillus by Samson et al. (23) recognizes 339 Aspergillus species and proposes the cmd gene as a secondary marker for their identification. In the beginning of this decade, the use of DNA sequencing for Aspergillus identification highlighted the frequent misidentification of sibling or cryptic Aspergillus species in earlier reports. The clinically relevant species identified in a few reports include A. lentulus, A. thermomutatus, A. udagawae, A. viridinutans, A. fumigatiaffinis, and A. novofumigatus in the Fumigati section; A. alliaceus in the Flavi section; A. carneus and A. alabamensis in the Terrei section; A. tubingensis and A. luchuensis (A. awamori and A. acidus) in the Nigri section; A. sydowii in the Versicolores section; A. westerdijkiae and A. persii in the Circumdati section; and A. calidoustus, A. insuetus, and A. keveii in the Usti section (8, 9, 24–27). However, the clinical context has been described in few of these species, and data on antifungal treatment outcome are even more infrequent. The present study is noteworthy to report the clinical entities attributed to rare Aspergillus species. Additionally, two cryptic species are reported for the first time from clinical samples, namely, A. pallidofulvus and A. egyptiacus. A. pallidofulvus was found to be an etiologic agent of invasive aspergillosis in a pediatric patient with aplastic anemia, whereas A. egyptiacus was probably a colonizer of the respiratory tract in a patient with chronic respiratory disease. Aspergillus pallidofulvus has been recently introduced in the section Circumdati and has been isolated from green coffee beans in India (28). Notably, A. chevalieri is reported for the first time as a cause of fatal cerebral aspergillosis acquired by traumatic inoculation, probably from the environment.

Overall, two-thirds of the rare Aspergillus species in this study were equally distributed in sections Circumdati, Nidulantes, Flavi, Terrei, Versicolores, and Aspergillus. This is in contrast to reports from Europe and the United States, where the most frequently identified rare Aspergillus species belonged to the section Flavi, followed by Nigri, Usti, and Fumigati (8, 9). However, in Brazil, Aspergillus species belonging to the section Flavi were most commonly reported, followed by Nidulantes (29). Considering that in the present study, only a limited number of isolates from the collection of Aspergillus species were molecularly identified, this may not represent the true scenario of the species and sections distribution. Therefore, future studies including large numbers of isolates are warranted to reflect the actual distribution of rare Aspergillus species in clinical specimens. Further, the distribution of these species can also vary depending on the geographical data and underlying disease. Recently, in two population-based studies on the epidemiology of invasive fungal diseases in hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) and solid organ transplant (SOT) recipients, A. fumigatus was the most common species causing infections in 44% and 60% patients in HSCT and SOT recipients, respectively (4, 30). Importantly, 26% of the HSCT and 7% of the SOT infections were caused by species that were classified as unspecified Aspergillus and were not further characterized (4, 30). Improved identification methods, such as MALDI-TOF MS proteome fingerprint analysis, had enabled the routine laboratory to identify these rare Aspergillus species. However, only a few reports on database creation of Aspergillus species are on record. Alanio et al., who developed a reference spectrum database, including 28 clinically relevant species from seven Aspergillus sections with five common and 23 new species, identified 98.6% of isolates correctly (31). In this study, 23 rare Aspergillus isolates, barring a solitary isolate that could not be identified to the species level by sequencing, were analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS. Using the Bruker database, low discrimination at the species level among A. terreus, A. hortai, and A. niveus and between A. tritici and A. candidus was observed. A similar report of low discrimination at the species level by the MALDI Biotyper has been on record between A. glaucus and A. amstelodami (32). It is speculated that the inclusion of phylogenetically closely related species in the database would enhance the ability of MALDI-TOF MS to correctly differentiate related species and will decrease the rate of nonidentifiable isolates. Interestingly, 14 of the 23 Aspergillus species previously not available in the database were identified with the amended database, which increased the identification rate from 38% to 95% of all the Aspergillus species. Further, taking into account the local epidemiology, the number of strains for each species in MALDI-TOF MS databases should be expanded to cover intraspecies variability in order to improve the usefulness of MALDI-TOF MS.

This study reports the susceptibility profiles of large numbers of isolates of rare Aspergillus species belonging to various sections. Although limited numbers of isolates from each species were available for AFST, the data generated have clinical utility. Overall, posaconazole and echinocandins were found to be the most potent drugs. However, 38% of the rare Aspergillus isolates had at least one antifungal drug resistance in the present study. Similar rates of high antifungal resistance were reported in the Spanish FILPOP study that showed 40% of cryptic Aspergillus species being resistant to one antifungal agent in vitro (9). Antifungal susceptibility data in the present study and from previous reports showed species-independent results, with strains of the same species exhibiting various susceptibility patterns (8, 9, 33). Finally, life-threatening invasive aspergillosis due to rare and cryptic Aspergillus species is complicated by limited therapeutic options. Consequently, surveillance of all Aspergillus species in different patient populations is warranted to evaluate the incidence of rare species for establishing population-based therapeutic guidelines.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

J.F.M received grants from Astellas, Basilea, and Merck. He has been a consultant to Astellas, Basilea, and Merck and received speaker's fees from Merck and Gilead. All other authors declare no potential conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Funding Statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kosmidis C, Denning DW. 2015. The clinical spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis. Thorax 70:270–277. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malani AN, Kauffman CA. 2007. Changing epidemiology of rare mould infections: implications for therapy. Drugs 67:1803–1812. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200767130-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lass-Flörl C. 2009. The changing face of epidemiology of invasive fungal disease in Europe. Mycoses 52:197–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2009.01691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kontoyiannis DP, Marr KA, Park BJ, Alexander BD, Anaissie EJ, Walsh TJ, Ito J, Andes DR, Baddley JW, Brown JM, Brumble LM, Freifeld AG, Hadley S, Herwaldt LA, Kauffman CA, Knapp K, Lyon GM, Morrison VA, Papanicolaou G, Patterson TF, Perl TM, Schuster MG, Walker R, Wannemuehler KA, Wingard JR, Chiller TM, Pappas PG. 2010. Prospective surveillance for invasive fungal infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, 2001–2006: overview of the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network (TRANSNET) database. Clin Infect Dis 50:1091–1100. doi: 10.1086/651263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dettman JR, Jacobson DJ, Taylor JW. 2006. Multilocus sequence data reveal extensive phylogenetic species diversity within the Neurospora discreta complex. Mycologia 98:436–446. doi: 10.3852/mycologia.98.3.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peterson SW. 2008. Phylogenetic analysis of Aspergillus species using DNA sequences from four loci. Mycologia 100:205–226. doi: 10.3852/mycologia.100.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balajee SA, Baddley JW, Peterson SW, Nickle D, Varga J, Boey A, Lass-Flörl C, Frisvad JC, Samson RA, ISHAM Working Group on A. terreus. 2009. Aspergillus alabamensis, a new clinically relevant species in the section Terrei. Eukaryot Cell 8:713–722. doi: 10.1128/EC.00272-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balajee SA, Kano R, Baddley JW, Moser SA, Marr KA, Alexander BD, Andes D, Kontoyiannis DP, Perrone G, Peterson S, Brandt ME, Pappas PG, Chiller T. 2009. Molecular identification of Aspergillus species collected for the transplant-associated infection surveillance network. J Clin Microbiol 47:3138–3141. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01070-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Mellado E, Peláez T, Pemán J, Zapico S, Alvarez M, Rodríguez-Tudela JL, Cuenca-Estrella M, FILPOP Study Group. 2013. Population-based survey of filamentous fungi and antifungal resistance in Spain (FILPOP study). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:3380–3387. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00383-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baddley JW, Marr KA, Andes DR, Walsh TJ, Kauffman CA, Kontoyiannis DP, Ito JI, Balajee SA, Pappas PG, Moser SA. 2009. Patterns of susceptibility of Aspergillus isolates recovered from patients enrolled in the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network. J Clin Microbiol 47:3271–3275. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00854-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chowdhary A, Kathuria S, Singh PK, Sharma B, Doltabadi S, Hagen F, Meis JF. 2014. Molecular characterization and in vitro antifungal susceptibility of 80 clinical isolates of mucormycetes in Delhi, India. Mycoses 57(Suppl 3):97–107. doi: 10.1111/myc.12234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong SB, Go SJ, Shin HD, Frisvad JC, Samson RA. 2005. Polyphasic taxonomy of Aspergillus fumigatus and related species. Mycologia 97:1316–1329. doi: 10.3852/mycologia.97.6.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glass NL, Donaldson GC. 1995. Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Appl Environ Microbiol 61:1323–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. 2013. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol 30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi; approved standard, 2nd ed CLSI document M38-A2. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Espinel-Ingroff A, Diekema DJ, Fothergill A, Johnson E, Pelaez T, Pfaller MA, Rinaldi MG, Canton E, Turnidge J. 2010. Wild-type MIC distributions and epidemiological cutoff values for the triazoles and six Aspergillus spp. for the CLSI broth microdilution method (M38-A2 document). J Clin Microbiol 48:3251–3257. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00536-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Espinel-Ingroff A, Chowdhary A, Gonzalez GM, Lass-Flörl C, Martin-Mazuelos E, Meis JF, Peláez T, Pfaller MA, Turnidge J. 2013. Multicenter study of isavuconazole MIC distributions and epidemiological cutoff values for Aspergillus spp. for the CLSI M38-A2 broth microdilution method. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:3823–3828. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00636-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Espinel-Ingroff A, Cuenca-Estrella M, Fothergill A, Fuller J, Ghannoum M, Johnson E, Pelaez T, Pfaller MA, Turnidge J. 2011. Wild-type MIC distributions and epidemiological cutoff values for amphotericin B and Aspergillus spp. for the CLSI broth microdilution method (M38-A2 document). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:5150–5154. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00686-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, Stevens DA, Edwards JE, Calandra T, Pappas PG, Maertens J, Lortholary O, Kauffman CA, Denning DW, Patterson TF, Maschmeyer G, Bille J, Dismukes WE, Herbrecht R, Hope WW, Kibbler CC, Kullberg BJ, Marr KA, Muñoz P, Odds FC, Perfect JR, Restrepo A, Ruhnke M, Segal BH, Sobel JD, Sorrell TC, Viscoli C, Wingard JR, Zaoutis T, Bennett JE, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. 2008. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis 46:1813–1821. doi: 10.1086/588660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Denning DW, Cadranel J, Beigelman-Aubry C, Ader F, Chakrabarti A, Blot S, Ullmann AJ, Dimopoulos G, Lange C, European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Disease, European Respiratory Society. 2016. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: rationale and clinical guidelines for diagnosis and management. Eur Respir J 47:45–68. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00583-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenberg M, Patterson R, Roberts M, Wang J. 1978. The assessment of immunologic and clinical changes occurring during corticosteroid therapy for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Am J Med 64:599–606. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(78)90579-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.deShazo RD, Swain RE. 1995. Diagnostic criteria for allergic fungal sinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 96:24–35. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(95)70029-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samson RA, Visagie CM, Houbraken J, Hong SB, Hubka V, Klaassen CH, Perrone G, Seifert KA, Susca A, Tanney JB, Varga J, Kocsubé S, Szigeti G, Yaguchi T, Frisvad JC. 2014. Phylogeny, identification and nomenclature of the genus Aspergillus. Stud Mycol 78:141–173. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Alcazar-Fuoli L, Cuenca-Estrella M. 2014. Antifungal susceptibility profile of cryptic species of Aspergillus. Mycopathologia 178:427–433. doi: 10.1007/s11046-014-9775-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alcazar-Fuoli L, Mellado E, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Cuenca-Estrella M, Rodriguez-Tudela JL. 2008. Aspergillus section Fumigati: antifungal susceptibility patterns and sequence-based identification. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:1244–1251. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00942-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alcazar-Fuoli L, Mellado E, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Cuenca-Estrella M, Rodriguez-Tudela JL. 2009. Species identification and antifungal susceptibility patterns of species belonging to Aspergillus section Nigri. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:4514–4517. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00585-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hong SB, Lee M, Kim DH, Varga J, Frisvad JC, Perrone G, Gomi K, Yamada O, Machida M, Houbraken J, Samson RA. 2013. Aspergillus luchuensis, an industrially important black Aspergillus in East Asia. PLoS One 8:e63769. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Visagie CM, Varga J, Houbraken J, Meijer M, Kocsubé S, Yilmaz N, Fotedar R, Seifert KA, Frisvad JC, Samson RA. 2014. Ochratoxin production and taxonomy of the yellow aspergilli (Aspergillus section Circumdati). Stud Mycol 78:1–61. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Negri CE, Gonçalves SS, Xafranski H, Bergamasco MD, Aquino VR, Castro PT, Colombo AL. 2014. Cryptic and rare Aspergillus species in Brazil: prevalence in clinical samples and in vitro susceptibility to triazoles. J Clin Microbiol 52:3633–3640. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01582-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pappas PG, Alexander BD, Andes DR, Hadley S, Kauffman CA, Freifeld A, Anaissie EJ, Brumble LM, Herwaldt L, Ito J, Kontoyiannis DP, Lyon GM, Marr KA, Morrison VA, Park BJ, Patterson TF, Perl TM, Oster RA, Schuster MG, Walker R, Walsh TJ, Wannemuehler KA, Chiller TM. 2010. Invasive fungal infections among organ transplant recipients: results of the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network (TRANSNET). Clin Infect Dis 50:1101–1111. doi: 10.1086/651262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alanio A, Beretti JL, Dauphin B, Mellado E, Quesne G, Lacroix C, Amara A, Berche P, Nassif X, Bougnoux ME. 2011. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry for fast and accurate identification of clinically relevant Aspergillus species. Clin Microbiol Infect 17:750–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schulthess B, Ledermann R, Mouttet F, Zbinden A, Bloemberg GV, Böttger EC, Hombach M. 2014. Use of the Bruker MALDI Biotyper for identification of molds in the clinical mycology laboratory. J Clin Microbiol 52:2797–2803. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00049-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lockhart SR, Zimbeck AJ, Baddley JW, Marr KA, Andes DR, Walsh TJ, Kauffman CA, Kontoyiannis DP, Ito JI, Pappas PG, Chiller T. 2011. In vitro echinocandin susceptibility of Aspergillus isolates from patients enrolled in the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:3944–3946. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00428-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]